Abstract

The measurement of autoantibodies in the clinical care of autoimmune patients allows for diagnosis, monitoring, and even disease prediction. Despite their clinical utility, the functional significance of autoantibody target proteins in many autoimmune diseases remains unclear. Here we present a comprehensive review of 52 autoantigens commonly employed for the serological diagnosis of 24 autoimmune diseases. We discuss their function, whether they have extracellular-exposed epitopes, and whether antibodies to these proteins are known to be pathogenic. Transcriptomics (RNA-Seq) datasets were mined to display messenger RNA (mRNA) expression of the autoantigens across 32 tissues and organs. This analysis revealed that autoantigens cluster into one of three groups: expression in the tissue most strongly affected in the disease (Group I), ubiquitous expression with enrichment in immune tissues (Group II), or expression in other tissues not typically associated with the clinical presentation (Group III). Clustering demonstrated that the autoantigens within Group I were often proteins containing extracellular epitopes, many of which are targets of pathogenic autoantibodies. Group II autoantigens were targets for several rheumatological diseases, including Sjögren syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, myositis, and systemic sclerosis, and were ubiquitously expressed with enrichment in immune-rich tissues. This raises the possibility that immune cells in Group II disorders may be the source of autoimmunization and/or targets of immune cell responses. Since tissues showing enriched autoantigen gene expression may contribute to the development of autoantibodies and subsequent autoimmunity, the emergent patterns arising from the autoantigen transcriptomic profiles may provide a new heuristic framework to deconvolute these complex disorders.

1 Introduction

Autoimmune diseases arise from abnormal immune responses mounted against self-proteins and other molecules present within the body. These diseases encompass a wide range of associated pathology, affecting many different tissue and organ sites. At present, 80–100 autoimmune diseases have been described, although detailed epidemiology is not available for all of them [1, 2]. The etiology of autoimmune diseases is not completely understood but is thought to involve gene-environmental interactions [3]. Genome-wide association studies have identified many polymorphisms in immune-related molecules, including cytokines, cytokine receptors, and immune-related transcription factors, which confer risk of autoimmunity, presumably by modulating immune function [4]. However, genetic tests have little predictive value by themselves because these diseases involve the interaction of many weakly associated allelic variations with the environment [5].

One key feature of most autoimmune diseases is the presence of autoantibodies generated by B cells against self-proteins [6]. In many autoimmune diseases, autoantibody measurements against disease-associated autoantigens are important diagnostic biomarkers, which often show individual prevalences ranging from 10 to 70 %. Besides diagnostics, autoantibodies targeting extracellular proteins such as receptors, cytokines, and matrix proteins can directly mediate autoimmune pathogenesis by sequestering or destroying these proteins [7]. The value of autoantibody testing cannot be overstated to confirm the diagnosis of a suspected autoimmune disease, follow the progression of the disease, and inform predictions of disease severity and future onset [8]. Along these lines, studies have shown that autoantibodies are present years before clinical symptoms and can be used to predict who might develop autoimmune conditions, including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), type I diabetes mellitus (T1D), and Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) [9–11]. Lastly, due to recent advances in high-throughput immunoassay detection of autoantibodies [12], it is possible to further categorize autoimmune diseases into subclasses based on the presence and levels of autoantibodies directed against different autoantigens demonstrating the utility of these measurements [13–16].

Despite the importance of autoantibodies, basic questions about the mechanisms by which particular self-proteins become immune targets remain poorly understood but may involve altered protein modification, alternative splicing, and gene mutations. There is also no way to predict which proteins are autoantigens in a given autoimmune disease and almost all autoantibody targets have been discovered by empirical screening studies. Moreover, several autoimmune diseases have few or no reliable autoantibody biomarkers and many autoantigens likely remain unknown. Another major question relates to the source of the autoantigen involved in generating the humoral response. In some cases, the autoimmune response is directed against a specific tissue or group of cells, resulting in the targeting of only a select group of autoantigens derived from this source (e.g. insulin derived from the β cells of the pancreas in T1D), but in other diseases the source of the autoantigens remains unknown.

The goal of this review was to describe the characteristics of many of the commonly employed autoantigens useful for the diagnosis of each of 24 different autoimmune diseases. We discuss the normal function of these proteins and indicate if they are targets of pathogenic autoantibodies. Additionally, the messenger RNA (mRNA) expression of these autoantigens is analyzed in a wide range of human tissues and organs, providing additional insight for understanding these autoimmune diseases.

2 Diverse Human Autoantigen Proteins for Diagnosis of Different Autoimmune Diseases

For this review, we focused on many common autoimmune diseases, including organ-specific, rheumatological, and other conditions where the autoantigens are well-defined. We excluded multiple sclerosis due to current controversies surrounding many of the proposed autoantigens. The list of 24 different diseases included neuromyelitis optica (NMO) [17], stiff-person syndrome (SPS) [18], T1D [19, 20], Hashimoto’s thyroiditis [21], Graves’ disease [4], myasthenia gravis [22, 23], Goodpasture disease [24, 25], membranous nephropathy [26, 27], Addison disease [28], autoimmune gastritis [29], pernicious anemia [29], autoimmune hepatitis [30], pemphigus vulgaris [31], dermatitis herpiformis [32], pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (PAP) [33], systemic vasculitis [34], adult-onset immunodeficiency with interferon (IFN)-γ autoantibodies [35], rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [36], SS [37], SLE [38], myositis [39], scleroderma/systemic sclerosis [40], primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) [41], and celiac disease [42]. Based on published reviews, a list of 52 established autoantigenic proteins was assembled for these different diseases that are often employed for their clinical autoantibody diagnosis. Although the list of 52 autoantigens is not exhaustive, it provides an overview of the humoral target proteins associated with these autoimmune diseases. In Table 1, the common name for each autoantigen, corresponding autoimmune disease(s), gene name, size of the protein, presence of extracellular epitopes and whether pathogenic autoantibodies are associated with the target proteins are enumerated.

Table 1.

Characteristics of common human autoantigens used for autoimmune disease diagnosis

| Autoantigen common name | Autoimmune disease | Gene name | Gene accession | Size (aa) | Extracellular epitopesa | Path Abb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aquaporin 4 (AQP-4) | Neuromyelitis optica | AQP4 | NM_001317384.1 | 352 | Y | Y |

| GAD65 | Stiff-person syndrome, T1D | GAD2 | NM_000818.2 | 585 | N | N |

| Insulin | Type I diabetes (T1D) | INS | NM_000207.2 | 110 | Y | N |

| IA2 | Type I diabetes | PTPRN | NM_001199763.1 | 950 | Y | Y |

| IA-2β | Type I diabetes | PTPRN2 | NM_001308267.1 | 977 | Y | N |

| ZnT8 | Type I diabetes | SLC30A8 | NM_173851.2 | 369 | N | N |

| TSHR | Graves’ disease (GD) | TSHR | NM_000369.2 | 764 | Y | Y |

| Thyroid peroxidase (TPO) | Hashimito’s thyroiditis, GD | TPO | NM_000547.5 | 933 | N | N |

| Thyroglobulin (TG) | Hashimito’s thyroiditis, GD | TG | NM_003235.4 | 2768 | Y | N |

| Cholinergic nicotinic α1 | Myasthenia gravis | CHRNA1 | NM_000079.3 | 457 | Y | Y |

| Muscle-specific kinase | Myasthenia gravis | MUSK | NM_001166280.1 | 783 | Y | Y |

| LRP4 | Myasthenia gravis | LRP4 | NM_002334.3 | 1905 | Y | Y |

| Collagen type IV-α3 chain | Goodpasture disease | COL4A3 | NM_000091.4 | 1670 | Y | Y |

| PLA2R | Membranous nephropathy | PLA2R1 | NM_001007267.2 | 1324 | Y | Y |

| THSD7A | Membranous nephropathy | THSD7A | NM_015204.2 | 1657 | Y | Y |

| Steroid 21-hydoxylase | Addison’s disease | Cyp21A2 | NM_000500.7 | 495 | N | N |

| Gastric ATPase α subunit | Autoimmune gastritis | ATP4A | NM_000704.2 | 1035 | Y | Y |

| Gastric ATPase β subunit | Autoimmune gastritis | ATP4B | NM_000705.3 | 291 | Y | Y |

| Gastric intrinsic factor | Autoimmune gastritis | GIF | NM_005142.2 | 417 | Y | Y |

| SLA | Autoimmune hepatitis | SEPSECS | NM_016955.3 | 501 | N | N |

| CYP2D6 | Autoimmune hepatitis | CyP2D6 | NM_000106.5 | 497 | N | N |

| FTCD | Autoimmune hepatitis | FTCD | NM_001320412.1 | 572 | N | N |

| Desmoglein 1 | Pemphigus | DSG1 | NM_001942.3 | 1049 | Y | Y |

| Desmoglein 3 | Pemphigus | DSG3 | NM_001944.2 | 999 | Y | Y |

| TGM3 | Dermatitis herpetiformis | TGM3 | NM_003245.3 | 693 | N | N |

| GMCSF | Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis | CSF2 | NM_000758.3 | 144 | Y | Y |

| PR3 | ANCA-associated vasculitis | PRNT3 | NM_002777.3 | 256 | Y | N |

| Myeloperoxidase (MPO) | ANCA-associated vasculitis | MPO | NM_000250.1 | 745 | Y | Y |

| Interferon-γ (IFNγ) | Disseminated non-tuberculosis | IFNG | NM_000619.2 | 166 | Y | Y |

| PAD-4 | Rheumatoid arthritis | PADI4 | NM_012387.2 | 663 | N | N |

| Ro52 (part of SSA) | Sjögren’s syndrome, SLE | TRIM21 | NM_003141.3 | 475 | N | N |

| Ro60 (part of SSA) | Sjögren’s syndrome, SLE | TROVE2 | NM_001042369.2 | 525 | N | N |

| La (also called SSB) | Sjögren’s syndrome, SLE | SSB | NM_001294145.1 | 408 | N | N |

| U1 snRNPA | Systemic lupus erythematosis (SLE) | SNRPA | NM_004596.4 | 228 | N | N |

| U1–70K | Systemic lupus erythematosis | SNRNP70 | NM_001301069.1 | 428 | N | N |

| Sm D3 | Systemic lupus erythematosis | SNRPD3 | NM_001278656.1 | 126 | N | N |

| Jo1 | Myositis | HARS | NM_001258040.2 | 469 | N | N |

| PL7 | Myositis | TARS | NM_001258437.1 | 723 | N | N |

| PM/Scl75 | Myositis | EXOSC9 | NM_001034194.1 | 456 | N | N |

| PM/Scl100 | Myositis | EXOSC10 | NM_001001998.2 | 885 | N | N |

| Mi-2b | Myositis | CHD4 | NM_001273.3 | 1912 | N | N |

| Mi-2a | Myositis | CHD3 | NM_001005271.2 | 2059 | N | N |

| MDA-5 | Myositis | IFIH1 | NM_022168.3 | 1025 | N | N |

| NXP2 | Myositis | MORC3 | NM_001320445.1 | 868 | N | N |

| Signal recognition particle | Myositis | SRP54 | NM_001146282.1 | 455 | N | N |

| TIF1-γ | Myositis | TRIM33 | NM_015906.3 | 1127 | N | N |

| HMGCR | Myositis | HMGCR | NM_000859.2 | 888 | N | N |

| Fibrillarin | Scleroderma | FBL | NM_001436.3 | 321 | N | N |

| TOP1 | Scleroderma | TOP1 | NM_003286.2 | 765 | N | N |

| RPC1 | Scleroderma | POLR3A | NM_007055.3 | 1390 | N | N |

| PDC-E2 | Primary biliary cirrhosis | DLAT | NM_001931.4 | 647 | N | N |

| TGM2 (also called TG2) | Celiac disease | TGM2 | NM_004613.2 | 687 | N | N |

Denotes whether protein has extracellular epitopes accessible to serum autoantibody binding

Denotes whether autoantibodies against the protein are involved in autoimmune pathogenesis

3 Transcriptional Profiling of Human Autoantigens

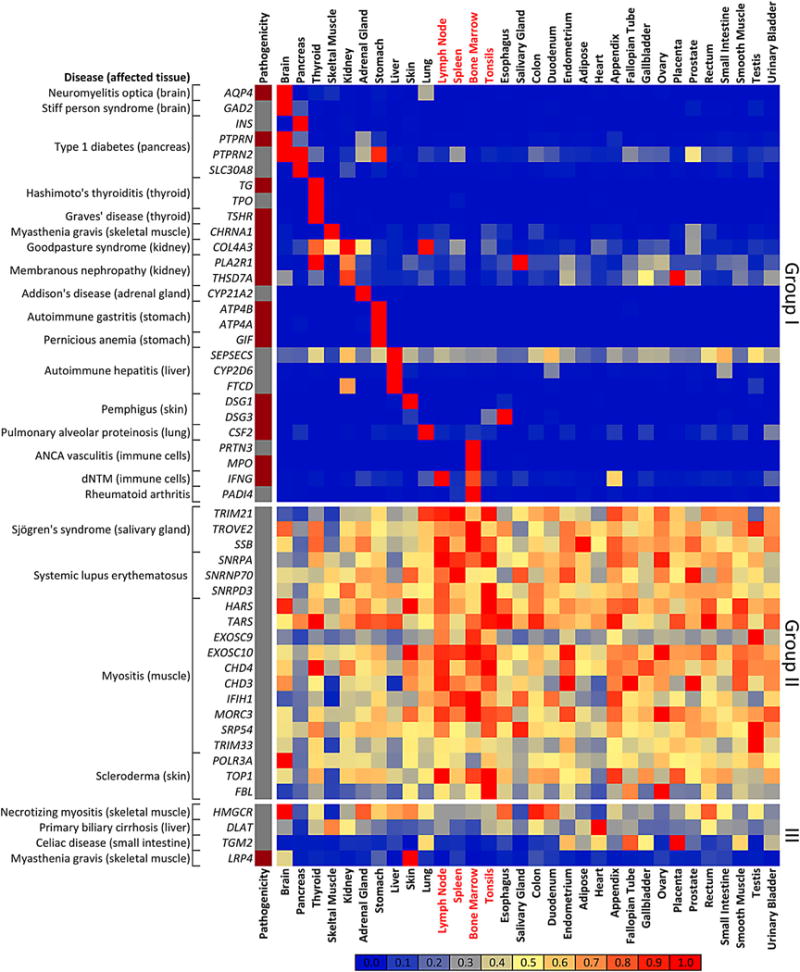

A systematic quantitative examination of the mRNA expression patterns for a large number of autoantigens across a wide range of tissues and organs has not been performed. Massively parallel next-generation sequencing of mRNAs (RNA-Seq) is among the highest resolution techniques to address the expression of transcripts [43]. Here we mined mRNA expression data from an existing RNA-Seq database quantifying 20,000 human genes in 32 tissues derived from 95 healthy individuals [44, 45]. We used these data to profile the mRNA expression pattern for each of the 52 autoantigens (see also http://www.proteinatlas.org). Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped read (FPKM) values in the 32 human tissues were extracted directly from this database, the maximum FPKM value across the 32 human tissues was identified for each gene, and all other FPKM values were expressed as a ratio of the maximum. These data were then plotted in a heatmap, where red represents 1.0 (the maximum value), yellow represents 0.5, and blue represents 0.0 (Fig. 1). Unless otherwise stated, the mRNA expression pattern was independently confirmed in the GTEx transcriptomic database (http://www.gtexportal.org) [46]. Based on the mRNA expression pattern, the autoantigens associated into one of three groups: enriched in the tissue primarily affected by the autoimmune disease (Group I), ubiquitously expressed (Group II), or expressed in other tissues not related to the autoimmune phenotype (Group III). As shown in Fig. 1, Group I autoantigens comprised two-thirds of the diseases examined and included NMO, T1D, autoimmune gastritis, membranous nephropathy, Graves’ disease, and PAP. Group II autoantigens were characterized by broad mRNA expression in different organs and tissues, and included autoimmune diseases such as SS, SLE, myositis, and systemic sclerosis (Fig. 1). For many Group II autoantigens, there was often mRNA enrichment in immune tissues such as bone marrow, spleen, lymph node, and/or tonsil. Comparing the FPKM values between these four immune tissues with the other 28 tissues revealed statistically higher values for 11 of the 19 Group II autoantigens (Mann–Whitney U test; p < 0.05). These enriched autoantigens included TRIM21, SSB, SNRPA, EXOSC9, EXOSC10, CHD4, CHD3, IFIH1, MORC3, TOP1 and FBL. Group III diseases showed mRNA expression that followed neither Group I nor Group II patterns and included PBC and celiac disease (Fig. 1). Further analysis of the autoantigen groups revealed several functional correlates. First, analysis of the 29 Group I autoantigens revealed a remarkable segregation of proteins harboring extracellular epitopes, many of which were targets of pathogenic autoantibodies. Second, all of the Group II autoantigens were intracellular proteins. The information and observations presented in Table 1 and Fig. 1, provide a new classification scheme and provide insights into disease pathogenesis. These aspects are examined for each of the autoimmune diseases in the following sections.

Fig. 1.

Segregation of human autoantigens by transcriptomic expression analysis. Massively parallel sequencing data mined from 32 human tissues were analyzed for 50 genes encoding autoantigens corresponding to 24 autoimmune diseases. RNA-Seq data were normalized and transformed such that each of the 1600 squares represents the percentage of the maximum expression value in any tissue for that transcript, in which red represents 100 % (the maximum value), yellow represents 50 %, and blue represents 0 %. The relative expression is based on the heatmap scale depicted at the bottom of the panel. Based on their expression, autoantigens, along with the corresponding autoimmune diseases, associated into one of three groups: enriched in the tissue primarily affected by the autoimmune disease (Group I), ubiquitously expressed (Group II), or expressed in other tissues not related to the autoimmune phenotype (Group III). The labels for four tissues (lymph node, spleen, bone marrow, and tonsil) showing mRNA enrichment for Group II autoantigens are colored in red. Autoantigens containing extracellular epitopes that are pathogenic are denoted in the column on the left (dark red) or uninvolved (grey). Of note, all the pathogenic autoantibodies segregate into Group I. mRNA messenger RNA, ANCA antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies, dNTM disseminated non-tuberculosis mycobacteria

4 Autoimmune Disease Overview along with the Corresponding Diagnostic Autoantigens

Twenty-four autoimmune diseases are described below, as well as the corresponding autoantigens useful for autoantibody-based diagnostics in each case. Additional characteristics of the autoantigens are also provided, along with a description of their mRNA expression profile in multiple human tissues and organs. The amino acid sizes for the different autoantigens is provided to illustrate the size heterogeneity of these proteins and also to highlight the inherent difficulties in producing full-length recombinant proteins for some of the large autoantigens (>700 amino acids).

4.1 Neuromyelitis Optica

NMO (or Devic syndrome) involves immune attack of the optic nerve and spinal cord, leading to loss of vision, limb paralysis, and other symptoms due to spinal cord dysfunction [47]. Clinical studies have shown that a majority of patients with NMO have pathogenic autoantibodies against aquaporin-4 (AQP4), a channel protein associated with astrocytes at the blood–brain barrier [17]. AQP4 is a transmembrane protein consisting of 352 amino acids with portions exposed to the extracellular milieu (Table 1). Consistent with the literature, RNA-Seq analysis of the 32 tissues and organs revealed that AQP4 mRNA was almost exclusively expressed in the CNS, one of the major target tissues of this autoimmune condition, with some additional expression in the lung (Fig. 1, Group I). While published studies have shown that high levels of AQP4 expression in the epithelial cells of the kidney is not evenly distributed and is not in the cortex [48, 49], it is possible the low expression detected by RNA-Seq analysis was due to the lack of the dissected kidney tissue comprising internal regions containing these epithelial cells.

4.2 Stiff-Person Syndrome

SPS is a rare autoimmune CNS disease characterized by a debilitating stiff trunk and/or limbs, epilepsy, and increased startle response [18]. The key serological diagnostic test for the diagnosis of SPS is the detection of autoantibodies against glutamic acid decarboxylase-65 (GAD65), an intracellular protein encoded by 585 amino acids and the major enzyme for the major inhibitory neurotransmitter, γ-aminobutyric acid (Table 1). Besides SPS, autoantibodies against GAD65 are also found in several other CNS neurological diseases, including epilepsy and encephalitis [50]. As shown in the heatmap, the highest mRNA expression of GAD2, encoding GAD65, was found in the brain, followed by the pancreas (Fig. 1, Group I). In the pancreas, GAD65 is found in the insulin-producing β-cells and is an autoantigen in T1D (see below).

4.3 Type I Diabetes

T1D involves immune destruction of the insulin-producing β cells in the pancreas [19]. Autoantibodies are directed against five major autoantigens, including insulin (INS), GAD65 (GAD2), IA2 (PTPRN), IA2-β (PTPRN2), and ZnT8 (SLC30A8). Besides their utility for diagnosis, autoantibodies against these targets can be found prior to the onset of T1D and are useful for prediction studies [20]. The first T1D autoantigen discovered is insulin, a small hormone, synthesized as 110 amino acid precursor protein (Table 1). For insulin, the mature processed form containing disulfide bonded B and A chains is used for autoantibody testing [51]. Two other targets, IA2 and IA2β are cell surface proteins containing both extracellular and intracellular regions, which are encoded by 950 and 977 amino acids, respectively. Interestingly, recent evidence suggests that IA2 is a target of B- and T-cell responses [52, 53] and may be involved in T1D pathogenesis. ZnT8 is a transmembrane protein of 369 amino acids found on intracellular vesicles. RNA transcriptomic analysis revealed that the five T1D autoantigens showed high levels of mRNA expression in the pancreas (Fig. 1, Group I). In the case of insulin (INS) and ZnT-8 (SLC30A8), their mRNA expression was over 200-fold higher in the pancreas compared with the next highest tissue. The mRNAs for GAD65 (GAD2) and IA2 (PTPRN) were most highly expressed in the brain, followed by the pancreas (Fig. 1, Group I). IA2-β (PTPRN2) mRNA expression demonstrated essentially similar levels in the pancreas and brain with some additional mRNA expression in the stomach. Despite their expression in brain, IA2 and IA2-β are only targets of autoantibodies in T1D and not in other autoimmune diseases. Importantly, the measurement of whole pancreas mRNA dilutes the signal derived from β cells, which comprise a relatively small subpopulation of this organ, expressing these genes at very high levels.

4.4 Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis

Hashimoto thyroiditis involves autoimmune attack on the thyroid gland, leading to a loss of its function [21]. Autoantibodies against two autoantigens, thyroid peroxidase (TPO) and thyroglobulin (TG) are used for diagnosis of Hashimoto thyroiditis (Table 1). Both TPO, encoded by 933 amino acids, and TG, encoded by 2768 amino acids, are involved in biosynthesis of thyroid hormones. From RNA analysis, only the thyroid gland was found to harbor mRNA expression for TPO and TG (Fig. 1, Group I).

4.5 Graves’ Disease

Graves’ disease is an autoimmune thyroid disease characterized by the overproduction of thyroid hormones [21]. The target autoantigen, thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor (TSHR), is a cell surface protein of 764 amino acids involved in binding thyroid-stimulating hormone (Table 1). Pathogenic autoantibodies bind and activate THSR and thereby stimulate downstream signaling to cause the increased release of T3 and T4 thyroid hormones, leading to the clinical features seen in Graves’ disease. As depicted in the heatmap, high levels of mRNA expression for TSHR were only found in the thyroid gland (Fig. 1, Group I). As in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, autoantibodies can also be found against TPO and TG in Graves’ disease.

4.6 Myasthenia Gravis

In myasthenia gravis, pathogenic autoantibodies target the neuromuscular junction and cause muscle weakness [22, 23]. The most common autoantibodies (85 %) in myasthenia gravis are directed against the α1 subunit of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) α1 (CHRM1). This receptor subunit is expressed by muscles and contains 457 amino acids (Table 1). Various nicotinic receptor subunits assemble into pore-containing pentameric complexes, allowing muscles to receive signals from cholinergic motoneurons. The highest mRNA expression for nAChR α1 protein was in the skeletal muscle, with little expression in other tissues (Fig. 1, Group I). Autoantibodies against another protein, muscle-specific tyrosine kinase (MuSK), are found in approximately 5 % of myasthenia gravis patients. MuSK, a protein of 783 amino acids, is located at the neuromuscular junction and has extracellular epitopes with an intracellular kinase domain (Table 1). Transcriptomics data are incomplete for the mRNA encoding MuSK in the Protein Atlas, and has been excluded from the present analysis. However, the GTEx database shows that MuSK is highly specific for skeletal muscle (Group I), consistent with published literature [54]. Interestingly, another minor autoantigen target in myasthenia gravis, LDL receptor-related protein 4 (LRP4), exhibited varying mRNA expression in many different tissues with low levels of mRNA in the affected skeletal muscle (Fig. 1, Group III). LRP4 is a very large protein of 1905 amino acids and appears to function in assembly of proteins at the neuromuscular junction required for acetylcholine receptor clustering [22].

4.7 Goodpasture Disease

Goodpasture disease, also known as anti-glomerular basement membrane disease, involves autoantibody deposition on glomerular and pulmonary basement membranes [24]. Autoantibodies directed against the collagen IV α3 chain (Col4A3), a large basement membrane collagen encoded by 1670 amino acids, are the cause of this autoimmune condition, resulting in kidney and lung dysfunction (Table 1) [25]. Pathogenic autoantibodies target epitopes within the C-terminus of the collagen IV α3 chain. Consistent with the clinical features of the disease, analysis of the RNA-Seq data revealed that the highest mRNA expression of COL4A3 was in the kidney, followed by the lung (Fig. 1, Group I). Most other tissues showed very little mRNA expression.

4.8 Membranous Nephropathy

Membranous nephropathy is characterized by focal antibody deposits in the kidney on the subepithelial aspect of the glomerular basement membrane adjacent to podocyte foot processes [26]. Pathogenic autoantibodies targeting the M-type phospholipase A2 receptor (encoded by PLA2R) occur in approximately 70 % of membranous nephropathy patients (Table 1). PLA2R is encoded by 1324 amino acids, and functions potentially in binding phospholipids. A second autoantigen target, thrombospondin type-1 domain-containing 7A (encoded by THSD7A), has been identified in 10 % of PLA2R seronegative patients [27]. THSD7A is also a large cell surface protein encoded by 1657 amino acid residues (Table 1). Consistent with their role as pathogenic autoantibodies causing membranous nephropathy, mRNAs for PLA2R and THSD7A showed the highest expression level in the kidney (Fig. 1, Group I).

4.9 Addison Disease

Addison disease is an autoimmune disease of the adrenal gland causing adrenal insufficiency [28]. The major autoantigen is a 495 amino acid intracellular enzyme, 21-hydroxylase/cytochrome P450 (CYP)21A2, which functions in the metabolism of steroid hormones, including cortisol and aldosterone (Table 1). Very high levels of mRNA for CYP21A2 were found in the adrenal gland, which were approximately 100-fold higher than the next tissue (Fig. 1, Group I).

4.10 Autoimmune Gastritis

In autoimmune gastritis, the parietal cells lining the stomach are attacked by the immune system [29]. The major autoantigens associated with autoimmune gastritis are directed against the α and β subunits of the gastric H+/K+ ATPase encoded by genes for ATPA4 and ATPB4, yielding two membrane-associated proteins of 1035 and 291 amino acids, respectively (Table 1). Typically, the entire proteins of these cell surface proteins are used as autoantigenic targets. As shown in the heatmap, the mRNAs for both subunits were almost exclusively expressed in the stomach and not expressed in other tissues (Fig. 1, Group I).

4.11 Pernicious Anemia

Autoimmune pernicious anemia involves vitamin B12 deficiency, and can also have overlapping clinical features with autoimmune gastritis. The most specific diagnostic test for autoimmune pernicious anemia is the detection of autoantibodies against gastric intrinsic factor (GIF). GIF is synthesized as a 417 amino acid protein, which is a secreted protein and functions in the binding and uptake of vitamin B12 (Table 1). Autoantibodies against GIF are pathogenic and block uptake of this important vitamin. Like the mRNAs for the gastric ATPase subunits, the mRNA for GIF is predominantly found in the stomach, with little expression noted in other tissues (Fig. 1, Group I).

4.12 Autoimmune Hepatitis

Autoimmune hepatitis involves destruction of the liver and has been classified as type I or type II [30]. In type I autoimmune hepatitis, the relevant autoantigen is the soluble liver antigen (SLA) protein. This protein derived from the SEPSECS gene consisting of 501 amino acids and is involved in the synthesis of selenocysteinyl-transfer RNA (tRNA) (Table 1). As shown in Fig. 1, mRNA for SLA exhibited the highest level in the liver, with weak expression in several other tissues (Fig. 1, Group I). In type II hepatitis, one autoantigen, LKM-1 (gene name CYP2D6) is a P450 enzyme involved in drug, steroid, and lipid metabolism. The other autoantigen target is formimidoyltransferase cyclodeaminase (FTCD), which functions in folate-mediated one-carbon metabolism (Table 1). The mRNAs for both LKM-1 and FTCD showed the highest mRNA expression level in the liver (Fig. 1, Group I); however, in the case of FTCD, there was also some mRNA expression in the kidney.

4.13 Pemphigus Vulgaris

Pemphigus vulgaris is an autoimmune disease of the skin causing blistering [31]. In pemphigus, pathogenic autoantibodies against either of two proteins, desmoglein 1 (DSG1) and desmoglein 3 (DSG3), disrupt the skin epithelial adhesion function of these two extracellular receptors. DSG1 and DSG3 encode large proteins of 1049 and 999 amino acids, respectively (Table 1). From analysis of the RNA-Seq data, high levels of expression of DSG1 were found in the skin, with markedly lower expression in other tissues (Fig. 1, Group I). DSG3 had the highest mRNA expression in the esophagus, but the skin showed the third highest tissue expression (Fig. 1, Group I). With the exception of the tonsils, all other tissues showed very little expression consistent with its categorization in Group I.

4.14 Dermatitis Herpetiformis

Dermatitis herpetiformis (DH) is an intensely pruritic papulovesicular skin disease that represents cutaneous manifestations of gluten sensitivity [32]. In DH, the target autoantigen is a TGM2 paralog, transglutaminase-3 (TGM3), containing 693 amino acids (Table 1). It is also notable that while the esophagus showed extraordinarily high levels of TGM3, significant levels were found in the skin, as revealed from the GTEx database (Group I, data not shown). Although not a target tissue, the esophagus is relevant because immunohistochemical staining of primate esophageal tissue using patient sera is an established method for detecting autoantibodies in DH [55]. In DH, clinically active but silent celiac disease results in the accumulation of anti-TGM3 immunoglobulin (Ig) A complexes in the skin, resulting in cutaneous symptoms [56].

4.15 Pulmonary Alveolar Proteinosis

PAP is an anti-cytokine, lung autoimmune disease involving the production of pathogenic autoantibodies that neutralize the activity of granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GMCSF) [33]. GMCSF is a secreted cytokine processed from a 144 amino acids precursor that acts on a variety of immune cells, including macrophages and neutrophils regulating differentiation and immune function (Table 1). The highest mRNA expression of CSF2, the gene encoding GMCSF, is in the lung, reflecting the high levels of expression of this gene in lung macrophages (Fig. 1, Group I). Very little detectable mRNA was found in other tissues. These findings are consistent with the major clinical presentation of lung disease in PAP, whereby patients inefficiently clear lung surfactant protein due to defective macrophages and other immune cells.

4.16 Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Autoantibodies-Associated Vasculitis

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies (ANCA)-associated vasculitis is characterized by inflammation and necrosis of small-sized blood vessels [57]. Two of the diagnostic antibodies are directed against proteinase-3 (PRTN3) and myeloperoxidase (MPO) (Table 1). These two enzymes are highly expressed in neutrophils. PRTN3 is a trypsin-like protease of 256 amino acids, and MPO contains 745 amino acid residues and is an enzyme involved in the production of reactive oxygen. Autoantibodies against MPO appear to be pathogenic [57]. The PRTN3 and MPO mRNAs were selectively expressed in the bone marrow (a tissue rich in neutrophils), whereas little expression was observed in other tissues (Fig. 1, Group I).

4.17 Disseminated Non-Tuberculosis Mycobacteria with Interferon-γ Autoantibodies

Patients with high levels of pathogenic autoantibodies against IFN-γ show an acquired immunodeficiency often characterized by disseminated non-tuberculosis mycobacteria (dNTM) infection [35]. IFN-γ is a key cytokine encoded by 166 amino acids and is involved in multiple immune-mediated pathways (Table 1). Although the serum autoantibodies target IFN-γ in the circulation, the source of the cytokine is derived from immune cells. The highest mRNA expression for IFNG was detected in the lymph node and spleen, which are an abundant source of lymphocytes and other immune cells (Fig. 1, Group I).

4.18 Rheumatoid Arthritis

RA is the most common autoimmune disease and is associated with chronic immune attack and inflammation of the joints [36]. The measurement of autoantibodies against citrullinated proteins, a post-translational modification of arginine residues, is a highly specific diagnostic tool for RA. Citrillination is mediated by peptidylarginine deiminases. One of the major enzymes responsible for the citrullination of these target proteins in RA is peptidylarginine deiminase-4 (PAD-4) [58], and antibodies can even be found against PAD-4 in RA. In addition, other proteins can be citrullinated by peptidylarginine deiminase and be targets of autoantibodies, including vimentin, fibrinogen, and filaggrin. Although the joint and synovial tissues were not represented in the RNA-Seq database used for analysis, the mRNA encoding PAD-4 (PADI4) showed the highest mRNA levels in the bone marrow, followed by the spleen, with little expression in other tissues (Fig. 1, Group I). These findings are consistent with other studies implicating inflammatory immune cells as a major source of PAD-4 activity in RA [59, 60].

4.19 Sjögren’s Syndrome

SS is an autoimmune disease involving oral and ocular dryness [37]. One of the criteria for the diagnosis of SS is the detection of autoantibodies against SSA and SSB. Two proteins comprising SSA are Ro52 (TRIM21) and Ro60 (Trove2), and one protein, La (SSB), is for SSB. Although the detection of autoantibodies against these autoantigens is highly sensitive for SS diagnosis, they are not specific for SS and can be found in other rheumatological diseases, including SLE and myositis (Table 1). Ro52 is an ubiquitin ligase composed of 475 amino acids, and studies have shown that it regulates ubiquitinylation of immune transcription factors and may act as a cytosolic antibody receptor [61]. Ro60 and La are RNA-binding proteins of 525 and 408 amino acid residues, respectively (Table 1). Recently, Ro60 was shown to bind Alu retrolement RNA molecules and regulate inflammatory gene expression [62]. Although the mRNA expression for TRIM21, TROVE2, and SSB was fairly ubiquitous, their expression showed low levels in the salivary gland (Fig. 1, Group II). The highest mRNA expression of all three autoantigens was seen in the lymph nodes, bone marrow, spleen, and tonsils containing known reservoirs of immune cells (Fig. 1, Group II).

4.20 Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

SLE involves autoimmune attack on many different tissues and cells [38]. Besides anti-DNA autoantibodies, diagnostic autoantibodies are directed against a variety of different autoantigens, including Ro52, Ro60, La, RNP-A, Sm-D3, and RNP-70K. RNA-A and RNP-70K are splicing proteins composed of 228 and 428 amino acids, respectively (Table 1). Sm-D3 is an RNA-binding protein composed of 126 amino acids that function in pre-mRNA splicing (Table 1). Similar to the SS autoantigens, the mRNA expression of SNRPA (RNP-A), SNRPD3 (Sm-D3) and SNRNP70 (RNP-70K) showed a relatively ubiquitous mRNA expression; however, the highest mRNA expression was detected in the lymph nodes, bone marrow, spleen, and tonsils (Fig. 1, Group II).

4.21 Myositis

A variety of autoimmune inflammatory muscle diseases are characterized under the umbrella of myositis [39]. In myositis, the main target tissue is the skeletal muscle. Serological responses against a number of different autoantigens can be used to identify patients with myositis, including Ro52, Ro60, La, Jo-1, PL7, PM/SCL75, PM/Scl100, Mi-2, Mi-2β and HMGCR. The Jo1 autoantigen is an enzyme of 469 amino acids responsible for histidyl-tRNA synthesis, and PL7 is a theonyl tRNA synthetase of 723 amino acids (Table 1). PM/SCL75 (456 amino acid residues) and PM/Scl100 (885 amino acid residues) are part of the RNA exosome complex, which plays a role in RNA processing and degradation. Mi-2b (CHD4) and Mi-2a (CHD3) are part of a histone deacetylase complex encoded by 1912 and 2059 amino acids. NXP2 (MORC3) is another myositis autoantigen associated with the nuclear matrix, and SRP54, containing 455 amino acids, functions as part of the signal recognition particle. HMG-CoA reductase (HMGCR) is an enzyme of 888 amino acids involved in the biosynthesis of cholesterol (Table 1). Autoantibodies against HMGCR are used for diagnosis of necrotizing myositis. As displayed in the heatmap, the mRNA for the myositis-associated autoantigens, HARS (Jo-1), ExoSc9 (PM/SCL75), ExoSc10 (PM/Scl100), CHD3, and CHD4, MORC3, SRP54 and TRIM33 did not show enrichment in the skeletal muscle (Fig. 1, Group II). Other potential tissue targets, including the smooth muscle and lung, also showed low mRNA levels. For many of the myositis autoantigens, the highest mRNA expression was observed in the spleen, thymus, bone marrow, and tonsils (Fig. 1, Group II). Interestingly, some dermomyositis patients with interstitial lung disease harbor autoantibodies against an RNA sensor, MDA-5 (IFIH1) [63], yet transcriptomic analysis also failed to find enrichment of this mRNA in the skin and lung but was highest in immune-rich tissue (Fig. 1, Group II). HMGRC was not expressed in the muscle and was only seen in selected tissues (Fig. 1, Group III).

4.22 Scleroderma

Scleroderma, also known as systemic sclerosis, is a disease characterized by extensive fibrosis of skin and internal organs, microvascular defects, and autoimmune abnormalities [40]. The disease can either target mainly the skin, or can diffusely affect many organs. In scleroderma, autoantibodies can target a variety of proteins, including fibrillarin (FBL), topoisomerase I (TOP1), and DNA polymerase (RPC1). Fibrillarin is involved in processing preribosomal RNA, while TOP1 and RPC1 function in DNA replication and repair and are encoded by 765 and 1390 amino acids, respectively. Recently, mutations within RPC, encoded by the POLR3A gene, were associated with autoantibodies in scleroderma [64]. Noticeably, the mRNAs for TOP1 and fibrillarin did not exhibit high expression in the skin or other organs such as lung, kidney, or liver, but showed enrichment in the bone marrow and/or tonsils (Fig. 1, Group II). POLR3A mRNA also showed ubiquitous expression but showed a high level of expression in the brain (Fig. 1, Group II).

4.23 Primary Biliary Cirrhosis

PBC is an autoimmune attack on the intrahepatic bile ducts of the liver, which can lead to liver failure [41]. The major diagnostic autoantigen for PBC is the E2 component of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC-E2) of 647 amino acids, which is encoded by the gene for dihydrolipoamide S-acetyltransferase (DLAT). The mRNA for DLAT was not enriched in the bile ducts but showed the highest mRNA levels in the heart muscle, followed by the skeletal muscle (Fig. 1, Group III). Mechanistically, environmental chemicals in the liver may modify the PDC-E2 enzyme, causing a loss in self-tolerance to this protein in susceptible individuals with PBC [65].

4.24 Celiac Disease

Celiac disease is an autoimmune disorder in which gluten cannot be tolerated, leading to damage to the small intestine [42]. One serologic test used to diagnose celiac disease is the presence of anti-IgA autoantibodies against transglutaminase-2 (TGM2; also called TG2). TGM2, a protein of 687 amino acids, is a tranglutaminase that catalyzes the cross-linking of proteins and the conjugation of polyamines to proteins. The mRNA expression of TGM2 was low in most tissues and no mRNA enrichment was detectable in the colon (Fig. 1, Group III). Despite broad expression, TGM2 acts to cross-link gluten within the small intestine, where it can become cross-linked to gluten, stimulating the production of TGM2-specific antibodies. The role of autoantibodies against TGM2 in the pathogenesis of celiac remains controversial.

5 Discussion

In this review, information is provided regarding the characteristics of 50 autoantigens employed for the serological diagnosis of 24 different autoimmune diseases. Analysis of the size, structure, or function of the different autoantigens revealed a complex heterogeneity at the protein level. However, an underlying order was discerned by applying a transcriptomic-based analysis of mRNA expression profile of the autoantigens across a large number of tissues, allowing for them to be segregated into one of three groups. Group I autoantigens accounted for 29 of the 52 proteins and was characterized by strong mRNA enrichment in the affected tissue relative to other tissues. Several autoantigens from Group I were diagnostic targets for autoimmune diseases considered organ-specific, including T1D, autoimmune gastritis, and autoimmune thyroid diseases. The next largest cluster, Group II autoantigens, consisted of 19 autoantigens, which showed a broad pattern of mRNA expression often with enrichment in immune-rich tissues such as lymph, spleen, bone marrow, and/or tonsils. Unlike Group I autoantigens, all of the Group II autoantigens were intracellular proteins having a general role in cellular function. The third pattern, Group III autoantigens (n = 4), exhibited varying mRNA expression in many different tissues but showed low levels of mRNA in the affected tissue. Although the classification approach was based on the transcriptomics of these autoantigens in healthy individuals, it is possible that the mRNA expression for some of these autoantigens may be modulated by the autoimmune process. However, the validity of examining healthy individuals for generating the grouping scheme is supported by the finding that multiple autoantigens for a given autoimmune disorder showed a similar tissue expression pattern. In addition, the gene expression profiles for the different autoantigens could also be used as a reference for guiding additional gene expression studies of disease and normal tissue. However, in any new RNA-Seq experiment, concurrent controls would need to be evaluated to ensure similar tissue dissection, sampling, and quality.

A common feature of Group I autoantigens was that many of the proteins contained extracellular epitopes, several of which were targets of pathogenic autoantibodies. For a number of conditions, including pernicious anemia, Goodpasture disease, and PAP, the target is a secreted protein; however, in other conditions, including Graves’ disease, membranous nephropathy, and myasthenia gravis, the autoantigen is a cell surface-associated protein. Although T1D is classified as a Group I disease, until recently it was not recognized to have pathogenic autoantibodies. However, newer information suggests that IA2, a cell surface molecule, is a target of B- and T-cell responses [52, 53] and may be involved in pathogenesis. It is also possible that transcriptomic analysis could be used to identify novel candidate autoantigens in Group I disorders. For this strategy, one might expect that highly abundant tissue-specific proteins might be targets of autoantibodies. Consistent with this idea, the zinc transporter-8 autoantigen in T1D was discovered, in part, from transcriptome analysis showing a high level of the corresponding SCL30A8 mRNA in the pancreas [66]. Thus, highly expressed tissue-specific genes derived from comprehensive RNA-Seq datasets may be candidate autoantigens for tissue-specific autoimmune diseases.

The genes for Group II autoantigens showed a ubiquitous pattern of mRNA expression and encoded only intracellular proteins. Group II autoantigens were markers for several rheumatological diseases, including Sjögren syndrome, SLE, myositis, and systemic sclerosis. An outstanding question is why autoantibodies to ubiquitously expressed intracellular proteins are biomarkers of SS and myositis, diseases showing relatively tissue-specific symptoms associated with autoimmune attack on the salivary gland and muscle, respectively. However, transcriptomic profiling points to the possibility that the primary defect in Group II diseases may involve a dysfunctional immune system, in which many of the mRNAs encoding these autoantigens demonstrated enrichment in immune-associated tissues. Consistent with these findings are studies demonstrating that SS, SLE, myositis, and systemic sclerosis have an IFN-α immune-based, gene activation signature [67–70] and have genetic association with multiple immune-related genes [71–74]. Studies exploring transcriptomic profiles in immune-associated organs and tissues are warranted for guiding the potential discovery of other autoantigens for Group II diseases.

Group III autoantigens represented the smallest category of autoimmune disorders and corresponded to four disorders. In two of the diseases, a role of the environment as a contributing factor is quite compelling. For example, there is increasing evidence for a potential role of environmental chemicals modifying the PDC-E2 enzyme in PBC as a mechanism for breaking self-tolerance to this protein in susceptible individuals [65]. In celiac disease, gluten from the diet enters the colon and interacts with the TGM2 enzyme, causing post-translational modification of gluten peptides that subsequently trigger an immune response, including autoantibodies against TGM2 [42, 75]. Thus, environmental triggers appear to mechanistically drive the immunogenicity of some of the target autoantigens in Group III.

One limitation to our study is the finding that it is known that mRNA expression does not always correspond to protein expression. However, several studies comparing gene expression with proteome analysis have found a high concordance, in which the abundance of the mRNA is often a good proxy for the presence of a protein [76]. Nevertheless, additional studies examining the protein levels for some of the novel transcriptomic findings are needed to further validate these observations.

In summary, this review provides the characteristics of many human autoantigens and applies a transcriptomic method of subdividing autoimmune diseases. As described, analysis and categorization of comprehensive mRNA datasets for these autoantigens revealed previously under-appreciated relationships within this heterogeneous group of disorders. This new categorization approach may provide multiple avenues for exploring these diseases and may aid in identifying additional autoantigen targets, diagnostics, preventive interventions and, ultimately, therapies.

Key Points.

Autoantibodies against many different protein autoantigens, varying in structure, function and expression, are important diagnostic biomarkers for diverse autoimmune diseases.

Exploring the pattern of expression of multiple target autoantigens based on large-scale RNA-Seq in different tissues reveals new types of subcategorization and insight into autoimmune processes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, and the Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health. The views expressed in this review are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institutes of Health or the United States Government.

Funding This work was supported by the intramural research programs of the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research and the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest Peter D. Burbelo, Michael J. Iadarola, Ilias Alevizos, and Matthew R. Sapio declare no conflicts of interest. No editorial support was used in the preparation of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Eaton WW, Pedersen MG, Atladottir HO, Gregory PE, Rose NR, Mortensen PB. The prevalence of 30 ICD-10 autoimmune diseases in Denmark. Immunol Res. 2010;47(1–3):228–31. doi: 10.1007/s12026-009-8153-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang L, Wang FS, Gershwin ME. Human autoimmune diseases: a comprehensive update. J Intern Med. 2015;278(4):369–95. doi: 10.1111/joim.12395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhernakova A, Withoff S, Wijmenga C. Clinical implications of shared genetics and pathogenesis in autoimmune diseases. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2013;9(11):646–59. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2013.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Invernizzi P, Gershwin ME. The genetics of human autoimmune disease. J Autoimmun. 2009;33(3–4):290–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Visscher PM, Brown MA, McCarthy MI, Yang J. Five years of GWAS discovery. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90(1):7–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elkon K, Casali P. Nature and functions of autoantibodies. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2008;4(9):491–8. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burbelo PD, Keller J, Kopp JB. New horizons for human pathogenic autoantibodies. Discov Med. 2015;20(108):17–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castro C, Gourley M. Diagnostic testing and interpretation of tests for autoimmunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(2 Suppl 2):S238–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.09.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arbuckle MR, McClain MT, Rubertone MV, Scofield RH, Dennis GJ, James JA, et al. Development of autoantibodies before the clinical onset of systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(16):1526–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jonsson R, Theander E, Sjostrom B, Brokstad K, Henriksson G. Autoantibodies present before symptom onset in primary Sjogren syndrome. JAMA. 2013;310(17):1854–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sosenko JM, Skyler JS, Palmer JP, Krischer JP, Yu L, Mahon J, et al. The prediction of type 1 diabetes by multiple autoantibody levels and their incorporation into an autoantibody risk score in relatives of type 1 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(9):2615–20. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burbelo PD, O’Hanlon TP. New autoantibody detection technologies yield novel insights into autoimmune disease. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2014;26(6):717–23. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ching KH, Burbelo PD, Tipton C, Wei C, Petri M, Sanz I, et al. Two major autoantibody clusters in systemic lupus erythematosus. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e32001. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brorsson CA, Onengut S, Chen WM, Wenzlau J, Yu L, Baker P, et al. Novel association between immune-mediated susceptibility loci and persistent autoantibody positivity in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2015;64(8):3017–27. doi: 10.2337/db14-1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Price JV, Haddon DJ, Kemmer D, Delepine G, Mandelbaum G, Jarrell JA, et al. Protein microarray analysis reveals BAFF-binding autoantibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(12):5135–45. doi: 10.1172/JCI70231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hueber W, Kidd BA, Tomooka BH, Lee BJ, Bruce B, Fries JF, et al. Antigen microarray profiling of autoantibodies in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(9):2645–55. doi: 10.1002/art.21269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lennon VA, Kryzer TJ, Pittock SJ, Verkman AS, Hinson SR. IgG marker of optic-spinal multiple sclerosis binds to the aquaporin-4 water channel. J Exp Med. 2005;202(4):473–7. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alexopoulos H, Dalakas MC. Immunology of stiff person syndrome and other GAD-associated neurological disorders. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2013;9(11):1043–53. doi: 10.1586/1744666X.2013.845527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Atkinson MA, Eisenbarth GS, Michels AW. Type 1 diabetes. Lancet. 2014;383(9911):69–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60591-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wenzlau JM, Hutton JC. Novel diabetes autoantibodies and prediction of type 1 diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2013;13(5):608–15. doi: 10.1007/s11892-013-0405-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Antonelli A, Ferrari SM, Corrado A, Di Domenicantonio A, Fallahi P. Autoimmune thyroid disorders. Autoimmun Rev. 2015;14(2):174–80. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ha JC, Richman DP. Myasthenia gravis and related disorders: pathology and molecular pathogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1852(4):651–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zisimopoulou P, Brenner T, Trakas N, Tzartos SJ. Serological diagnostics in myasthenia gravis based on novel assays and recently identified antigens. Autoimmun Rev. 2013;12(9):924–30. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greco A, Rizzo MI, De Virgilio A, Gallo A, Fusconi M, Pagliuca G, et al. Goodpasture’s syndrome: a clinical update. Autoimmun Rev. 2015;14(3):246–53. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pedchenko V, Bondar O, Fogo AB, Vanacore R, Voziyan P, Kitching AR, et al. Molecular architecture of the Goodpasture autoantigen in anti-GBM nephritis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(4):343–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0910500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beck LH, Jr, Salant DJ. Membranous nephropathy: from models to man. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(6):2307–14. doi: 10.1172/JCI72270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tomas NM, Beck LH, Jr, Meyer-Schwesinger C, Seitz-Polski B, Ma H, Zahner G, et al. Thrombospondin type-1 domain-containing 7A in idiopathic membranous nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(24):2277–87. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1409354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brandao Neto RA, de Carvalho JF. Diagnosis and classification of Addison’s disease (autoimmune adrenalitis) Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13(4–5):408–11. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toh BH. Diagnosis and classification of autoimmune gastritis. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13(4–5):459–62. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liberal R, Grant CR, Longhi MS, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D. Diagnostic criteria of autoimmune hepatitis. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13(4–5):435–40. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baum S, Sakka N, Artsi O, Trau H, Barzilai A. Diagnosis and classification of autoimmune blistering diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13(4–5):482–9. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jakes AD, Bradley S, Donlevy L. Dermatitis herpetiformis. BMJ. 2014;348:g2557. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g2557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ben-Dov I, Segel MJ. Autoimmune pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: clinical course and diagnostic criteria. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13(4–5):513–7. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silva de Souza AW. Autoantibodies in systemic vasculitis. Front Immunol. 2015;6:184. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Browne SK, Burbelo PD, Chetchotisakd P, Suputtamongkol Y, Kiertiburanakul S, Shaw PA, et al. Adult-onset immunodeficiency in Thailand and Taiwan. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(8):725–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1111160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McInnes IB, Schett G. The pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(23):2205–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1004965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fox RI. Sjogren’s syndrome. Lancet. 2005;366(9482):321–31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66990-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Agmon-Levin N, Mosca M, Petri M, Shoenfeld Y. Systemic lupus erythematosus one disease or many? Autoimmun Rev. 2012;11(8):593–5. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2011.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dalakas MC. Inflammatory muscle diseases. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(18):1734–47. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1402225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gabrielli A, Avvedimento EV, Krieg T. Scleroderma. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(19):1989–2003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0806188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hirschfield GM, Gershwin ME. The immunobiology and pathophysiology of primary biliary cirrhosis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2013;8:303–30. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-020712-164014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kelly CP, Bai JC, Liu E, Leffler DA. Advances in diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(6):1175–86. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.01.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McGettigan PA. Transcriptomics in the RNA-seq era. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2013;17(1):4–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Uhlen M, Fagerberg L, Hallstrom BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, et al. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science. 2015;347(6220):1260419. doi: 10.1126/science.1260419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fagerberg L, Hallstrom BM, Oksvold P, Kampf C, Djureinovic D, Odeberg J, et al. Analysis of the human tissue-specific expression by genome-wide integration of transcriptomics and antibody-based proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014;13(2):397–406. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.035600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pierson E, Consortium GT, Koller D, Battle A, Mostafavi S, Ardlie KG, et al. Sharing and specificity of co-expression networks across 35 human tissues. PLoS Comput Biol. 2015;11(5):e1004220. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Drori T, Chapman J. Diagnosis and classification of neuromyelitis optica (Devic’s syndrome) Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13(4–5):531–3. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Terris J, Ecelbarger CA, Marples D, Knepper MA, Nielsen S. Distribution of aquaporin-4 water channel expression within rat kidney. Am J Physiol. 1995;269(6 Pt 2):F775–85. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1995.269.6.F775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Verkman AS, Phuan PW, Asavapanumas N, Tradtrantip L. Biology of AQP4 and anti-AQP4 antibody: therapeutic implications for NMO. Brain Pathol. 2013;23(6):684–95. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ali F, Rowley M, Jayakrishnan B, Teuber S, Gershwin ME, Mackay IR. Stiff-person syndrome (SPS) and anti-GAD-related CNS degenerations: protean additions to the autoimmune central neuropathies. J Autoimmun. 2011;37(2):79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bingley PJ. Clinical applications of diabetes antibody testing. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(1):25–33. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morran MP, Casu A, Arena VC, Pietropaolo S, Zhang YJ, Satin LS, et al. Humoral autoimmunity against the extracellular domain of the neuroendocrine autoantigen IA-2 heightens the risk of type 1 diabetes. Endocrinology. 2010;151(6):2528–37. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van Lummel M, van Veelen PA, de Ru AH, Janssen GM, Pool J, Laban S, et al. Dendritic cells guide islet autoimmunity through a restricted and uniquely processed peptidome presented by high-risk HLA-DR. J Immunol. 2016;196(8):3253–63. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Valenzuela DM, Stitt TN, DiStefano PS, Rojas E, Mattsson K, Compton DL, et al. Receptor tyrosine kinase specific for the skeletal muscle lineage: expression in embryonic muscle, at the neuromuscular junction, and after injury. Neuron. 1995;15(3):573–84. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sardy M, Karpati S, Merkl B, Paulsson M, Smyth N. Epidermal transglutaminase (TGase 3) is the autoantigen of dermatitis herpetiformis. J Exp Med. 2002;195(6):747–57. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reunala T, Salmi TT, Hervonen K. Dermatitis herpetiformis: pathognomonic transglutaminase IgA deposits in the skin and excellent prognosis on a gluten-free diet. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95(8):917–22. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kallenberg CG. Pathogenesis of ANCA-associated vasculitides. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(Suppl 1):i59–63. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.138024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Harris ML, Darrah E, Lam GK, Bartlett SJ, Giles JT, Grant AV, et al. Association of autoimmunity to peptidyl arginine deiminase type 4 with genotype and disease severity in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(7):1958–67. doi: 10.1002/art.23596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Foulquier C, Sebbag M, Clavel C, Chapuy-Regaud S, Al Badine R, Mechin MC, et al. Peptidyl arginine deiminase type 2 (PAD-2) and PAD-4 but not PAD-1, PAD-3, and PAD-6 are expressed in rheumatoid arthritis synovium in close association with tissue inflammation. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(11):3541–53. doi: 10.1002/art.22983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vossenaar ER, Radstake TR, van der Heijden A, van Mansum MA, Dieteren C, de Rooij DJ, et al. Expression and activity of citrullinating peptidylarginine deiminase enzymes in monocytes and macrophages. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63(4):373–81. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.012211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Oke V, Wahren-Herlenius M. The immunobiology of Ro52 (TRIM21) in autoimmunity: a critical review. J Autoimmun. 2012;39(1–2):77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hung T, Pratt GA, Sundararaman B, Townsend MJ, Chaivorapol C, Bhangale T, et al. The Ro60 autoantigen binds endogenous retroelements and regulates inflammatory gene expression. Science. 2015;350(6259):455–9. doi: 10.1126/science.aac7442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chaisson NF, Paik J, Orbai AM, Casciola-Rosen L, Fiorentino D, Danoff S, et al. A novel dermato-pulmonary syndrome associated with MDA-5 antibodies: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2012;91(4):220–8. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3182606f0b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Joseph CG, Darrah E, Shah AA, Skora AD, Casciola-Rosen LA, Wigley FM, et al. Association of the autoimmune disease scleroderma with an immunologic response to cancer. Science. 2014;343(6167):152–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1246886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Leung PS, Wang J, Naiyanetr P, Kenny TP, Lam KS, Kurth MJ, et al. Environment and primary biliary cirrhosis: electrophilic drugs and the induction of AMA. J Autoimmun. 2013;41:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wenzlau JM, Juhl K, Yu L, Moua O, Sarkar SA, Gottlieb P, et al. The cation efflux transporter ZnT8 (Slc30A8) is a major autoantigen in human type 1 diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104(43):17040–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705894104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Crow MK, Kirou KA, Wohlgemuth J. Microarray analysis of interferon-regulated genes in SLE. Autoimmunity. 2003;36(8):481–90. doi: 10.1080/08916930310001625952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vakaloglou KM, Mavragani CP. Activation of the type I interferon pathway in primary Sjogren’s syndrome: an update. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2011;23(5):459–64. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e328349fd30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Baechler EC, Bilgic H, Reed AM. Type I interferon pathway in adult and juvenile dermatomyositis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13(6):249. doi: 10.1186/ar3531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wu M, Assassi S. The role of type 1 interferon in systemic sclerosis. Front Immunol. 2013;4:266. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Costa-Reis P, Sullivan KE. Genetics and epigenetics of systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2013;15(9):369. doi: 10.1007/s11926-013-0369-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rothwell S, Cooper RG, Lamb JA, Chinoy H. Entering a new phase of immunogenetics in the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2013;25(6):735–41. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000434676.70268.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mayes MD. The genetics of scleroderma: looking into the postgenomic era. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2012;24(6):677–84. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e328358575b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Burbelo PD, Ambatipudi K, Alevizos I. Genome-wide association studies in Sjogren’s syndrome: what do the genes tell us about disease pathogenesis? Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13(7):756–61. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lerner A, Matthias T. Rheumatoid arthritis-celiac disease relationship: joints get that gut feeling. Autoimmun Rev. 2015;14(11):1038–47. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vogel C, Marcotte EM. Insights into the regulation of protein abundance from proteomic and transcriptomic analyses. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13(4):227–32. doi: 10.1038/nrg3185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]