Abstract

Objective

Suicidal behaviors are the leading causes of injury and death worldwide, and are leading causes of maternal deaths in some countries. One of the strongest risk factors, suicidal ideation, is considered a harbinger and distal predictor of later suicide attempt and completion, and also presents an opportunity for interventions prior to physical self-harm. The purpose of this systematic epidemiologic review is to synthesize available research on antepartum suicidal ideation.

Data sources

Original publications were identified through searches of the electronic databases using the search terms pregnancy, pregnant women, suicidal ideation, and pregnan* and suicid* as root searches. We also reviewed references of published articles.

Study Selection

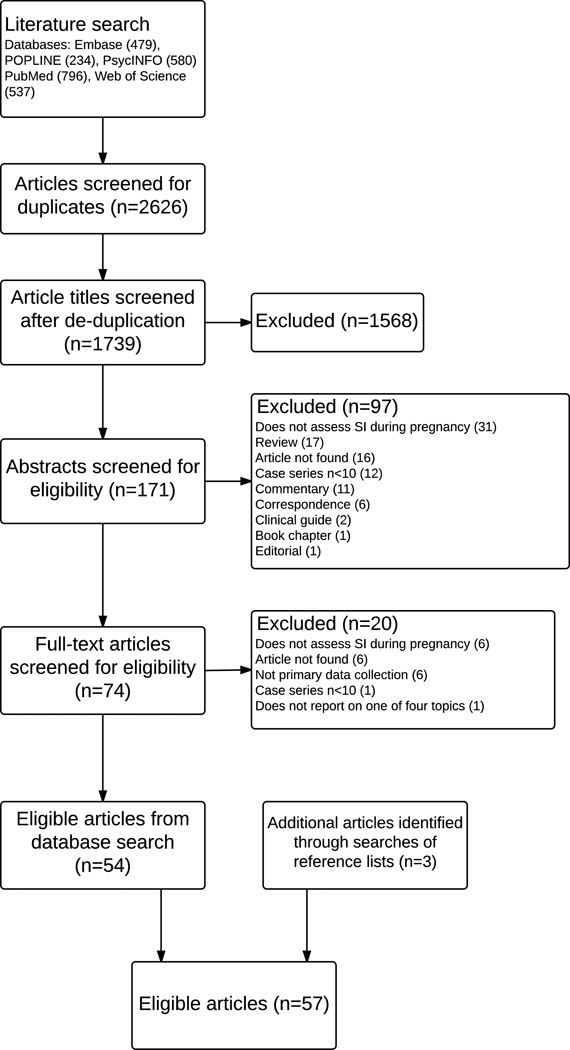

We identified a total of 2,626 articles through the electronic database search. After irrelevant and redundant articles were excluded 57 articles were selected. The selected articles were original articles that focused on pregnancy and suicidal ideation.

Results

Of the 57 included articles, 20 reported prevalence, 26 reported risk factors, 21 reported consequences of antepartum suicidal ideation, and 5 reported on screening measures. Available evidence indicates that pregnant women are more likely than the general population to endorse suicidal ideation. Additionally, a number of risk factors for antepartum suicidal ideation were identified including intimate partner violence, <12 years education, and major depressive disorder.

Conclusion

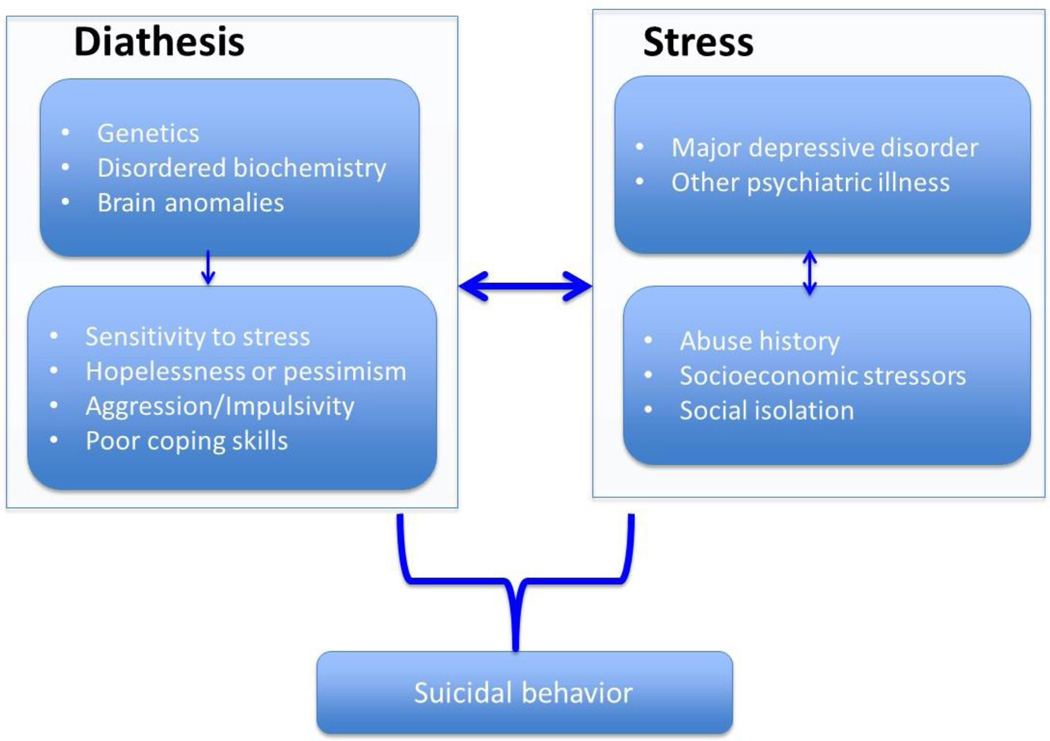

There is a need for enhanced screening for antepartum suicidal ideation. The few screening instruments that exist are limited as they were primarily developed to measure antepartum and postpartum depression. Given a substantial proportion of women with suicidal ideation do not meet clinical thresholds of depression and given the stress–diathesis model that shows susceptibility to suicidal behavior independent of depressive disorders, innovative approaches to improve screening and detection of antepartum suicidal ideation are urgently needed.

Keywords: suicide, pregnancy

INTRODUCTION

Suicidal behaviors (e.g., suicidal ideation, suicide plans, and suicide attempts) are the leading causes of injury and death worldwide, and are important determinants of maternal death in some countries (Oates, 2003). According to a recent report by the World Health Organization (WHO) over 800,000 individuals die by suicide each year, resulting in an annual global age-standardized suicide rate of 11.4 per 100,000 persons (Organization, 2014). Furthermore, for each suicide that occurs there exist many more suicide attempts that may result in severe injury (Nock et al., 2008). To develop a comprehensive prevention strategy, the WHO objectives for suicide prevention emphasize identification of high-risk groups and precipitating factors that lead to attempted or completed suicide. One of the strongest risk factors, suicidal ideation, is considered a harbinger and distal predictor of later suicide attempt and completion (Joiner et al., 2000, Lindahl et al., 2005), and thus identification of individuals who endorse suicidal ideation presents an important opportunity for directing suicide prevention efforts to those at highest risk of self-harm.

For instance, using cross-national data from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) Survey, Nock et al. (Nock et al., 2008) found that the lifetime prevalence estimates of suicidal ideation, plans, and attempts were 9.2%, 3.1%, and 2.7%, respectively. Notably, the majority of individuals with suicidal ideation who subsequently make a plan and attempt suicide do so within the first year of onset of ideation (Nock et al., 2008). Kessler et al. (Kessler et al., 2005), using data from National Comorbidity Survey and its replication, reported similar observations about the rapid transition from onset of ideation to onset of planning and attempting suicide.

Contrary to the misconception that pregnancy might have a protective effect against suicide (Appleby, 1991), a growing body of evidence now suggests that the prevalence of suicidal ideation may be even higher among pregnant women (Newport et al., 2007). Indeed, recent research suggests that suicidal ideation is a relatively common complication of pregnancy worldwide. In a previous review of the literature concerning suicide during pregnancy, Gentile (Gentile, 2011) reported that the prevalence of suicidal ideation among pregnant women is as high as 33%. Despite the high prevalence of suicidal ideation among pregnant women, there has not yet been a comprehensive, and epidemiologically informed systematic review of what is known about antepartum suicidal ideation. Previous reviews have focused on postpartum women and have generally limited their scope of inquiry to suicide attempts, not the full spectrum of suicidal behaviors (Gentile, 2011, Lindahl et al., 2005). However, postpartum suicidal behaviors (including suicidal ideation, attempts, and completed suicide) are often preceded by antepartum suicidal behavior (Lindahl et al., 2005, Nock et al., 2008). Of note this pattern of antepartum conditions predicting postpartum risks and persisting well beyond the prenatal period is seen for maternal mood, anxiety, and stress disorders (Gavin et al., 2011, Brand and Brennan, 2009). Hence, we maintain that the antepartum period represents a critical period and important opportunity for suicide risk reduction and prevention.

Additionally antepartum suicidal behavior has enduring adverse health effects on maternal and fetal outcomes (Brand and Brennan, 2009) (Van den Bergh et al., 2005). Consistent with the fetal programming hypothesis, which states that the in utero environment can alter the development of the fetal nervous system during particular sensitive periods, it is important to understand the impact of antepartum suicidal behavior on child neurocognitive development (Brand and Brennan, 2009, Van den Bergh et al., 2005). Thus, the purpose of this systematic epidemiologic review is to synthesize all research on antepartum suicidal ideation. This systematic review is intended to set the stage for creating new generalizable knowledge to fill gaps that remain in understanding the causes of intergenerational consequences of suicidal ideation among pregnant and postpartum women. We expect that evidence-based targeted interventions and suicide prevention efforts will be developed and tested with the goal of reducing the burden and mitigating the risks of suicidal behaviors among mothers, children, and families.

METHODS

The literature search for this systematic review included original studies of human subjects with no limitation on the year of publication or language. The search was open to observational studies including case series with ≥10 subjects, chart reviews, and cross-sectional, prospective cohort, retrospective cohort, and case-control studies. An article was included if it reported on one of the following topics: 1) prevalence estimates of suicidal ideation during pregnancy, 2) risk factors for suicidal ideation during pregnancy, 3) consequences of suicidal ideation during pregnancy, and 4) screening for suicidal ideation during pregnancy.

Studies were identified through searches of the electronic databases Embase, PsycINFO, POPLINE, PubMed, and Web of Science. The last search was conducted on 3 June 2015. Our search terms were pregnancy, pregnant women, suicidal ideation, and pregnan* and suicid* as root searches. One author (S.K.) conducted a title screen of all articles after removing duplicates. Full texts of the selected studies were then retrieved and read in full in an unblinded and independent manner by two authors (S.K. and B.G.). An article was excluded if it was not an example of primary data collection or analysis (reviews, editorials, commentaries, etc.); if it was a case series with fewer than 10 subjects; if the full text could not be found; or if it did not report on any of the four topics listed above. Additionally, the bibliographies of relevant articles were reviewed to identify articles not otherwise indexed or discoverable.

RESULTS

We identified a total of 2,626 articles through the electronic database search (479 from Embase, 234 from POPLINE, 580 from PsycINFO, 796 from PubMed, and 537 from Web of Science). Of which 887 were duplicates. We then screened the titles of the remaining 1,739 articles based on relevance and excluded 1,568 articles. The abstracts of the remaining unique 171 articles were read. Of these, we excluded an additional 97 articles leaving 74 articles to undergo a full-text screening. Overall, 20 articles were excluded during the full-text screen based on the aforementioned exclusion criteria. Thus, we identified 54 eligible articles from the database search. We identified 3 additional articles by searching the bibliographies of the eligible articles. Hence, a total of 57 articles met the inclusion criteria. Figure 1 illustrates the search and screening process.

Figure 1.

Flow Chart

Of the 57 included articles, 20 reported the prevalence of antepartum suicidal ideation, 26 reported risk factors for antepartum suicidal ideation, 21 reported perinatal and neonatal consequences of antepartum suicidal ideation, and 5 reported on screening for antepartum suicidal ideation. The characteristics of the studies in each of these categories are displayed in Table 1 and Supplemental Tables 1–3. Among the total 57 articles, 7 (12.3%) were published between 1990–1999, 21 (36.8%) were published between 2000–2009, and 29 (50.9%) were published between 2010–2015. Nineteen (33.3%) were conducted in the U.S., 22 (38.6%) in Europe, 11 (19.3%) in South America, and 5 (8.8%) in Asia. Regarding study design, 1 (1.8%) was a case-control study, 19 (33.3%) were cross-sectional studies, 9 (15.8%) were analyses of data from prospective studies, and 28 (49.1%) were analyses of data from retrospective studies.

Table 1.

Studies reporting the prevalence of antepartum suicide behavior

| Author | Year | Setting | Sample | Study design | Measures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alhusen | 2015 | Mid-Atlantic region, USA |

166 pregnant women |

Cross-sectional | SI: Question 10 of EPDS; Depressive symptoms: EPDS >12; IPV: AAS |

22.8% of participants reported SI during index pregnancy. |

| Asad | 2010 | Urban Pakistan | 1369 pregnant women |

Cross-sectional | AKUADS | 11% of participants had considered suicide. |

| Benute | 2011 | Sao Paulo, Brazil | 268 high-risk pregnant women |

Cross-sectional | Suicidal behavior: PRIME-MD (Portuguese) |

5% of participants reported SI. |

| Farias | 2013 | Rio de Janeiro, Brazil |

239 pregnant women |

Cross-sectional | Axis I psychiatric disorders: MINI; CSR: six-question suicidality module in MINI |

18.4% of participants had CSR. |

| Fildes | 1992 | Cook County, USA |

Women aged 12–45 yrs |

Retrospective analysis of Medical Examiner files |

Medical Examiner records | 9% of maternal deaths during this time period were attributable to suicide. |

| Freitas | 2002 | Sao Paulo, Brazil | 120 pregnant adolescents |

Cross-sectional | Anxiety and depression: HAD; SI: BSI; Non-psychotic psychiatric disorders: CIS-R |

16.7% adolescents reported SI |

| Gausia | 2009 | Rural Bangladesh | 361 pregnant women |

Prospective cohort study |

Psychiatric assessment: EPDS-B (Bangla version) |

14% participants reported thoughts of self- harm during pregnancy. |

| Gavin | 2011 | Washington State, USA |

2159 pregnant women |

Cross-sectional study at a University Hospital |

SI: PHQ short form | 2.7% of participants reported SI during pregnancy. |

| Gissler | 2005 | Finland | 5299 women aged 15–49yrs |

Retrospective analysis of population data |

Medical Birth Register, Register on Induced Abortions, Hospital Discharge Register |

The age-adjusted suicide rate among pregnant women was 9.9/100,000 pregnancies compared to 11.8/100,000 person-years among non-pregnant women. The suicide risk ratio for pregnant vs. non- pregnant women was 0.84 (95% CI:0.69– 1.01). |

| Huang | 2012 | Sao Paulo, Brazil | 831 pregnant women |

Cross-sectional | Common mental disorder: SRQ-20 |

The prevalence of antepartum SI was 6.3%. |

| Kim | 2015 | USA | 22118 pregnant women |

Retrospective cohort study |

SI: EPDS | The prevalence of antepartum SI was 3.8% |

| Mauri | 2012 | Pisa, Italy | 1066 pregnant women |

Prospective cohort study |

Suicidality: MOODS-SR and item 10 of EPDS; Depression: SCID-I |

The period prevalence of SI was 6.9% (95% CI: 6.0–7.8) during pregnancy and 4.3% (95% CI: 3.4–5.2) during the postpartum period when assessed using MOODS-SR. When assessed using item 10 of EPDS, the period prevalence during pregnancy was 12.0% (95% CI: 10.8–13.2) and 8.6% (95% CI: 7.4– 9.8) during the postpartum period. |

| Melville | 2010 | USA | 1888 pregnant women |

Prospective cohort study |

SI: PHQ short form | Current SI was reported by 2.6% of participants. |

| Newport | 2007 | Atlanta, USA | 383 pregnant women |

Prospective cohort study |

SI: item 9 of BDI and/or item 3 of HRSD |

SI was reported among 96 (27.8%) on the BDI and 51 (16.7%) on the HRSD. |

| Palladino | 2011 | USA | Women aged 15–54 yrs |

Retrospective analysis of population data |

National Violent Death Reporting System data |

The pregnancy-associated suicide rate was 2.0 deaths/100,000 live births. |

| Samandari | 2011 | North Carolina, USA |

Women aged 14–44 yrs |

Retrospective analysis of population data |

North Carolina surveillance and vital statistics data |

The suicide rate for pregnant women was 27% of the rate for non-pregnant/non- postpartum women (IRR=0.27, 95% CI:0.11– 0.66). |

| Vaz | 2014 | Rio de Janeiro, Brazil |

234 pregnant women |

Cross-sectional | Psychiatric assessment: MINI | The prevalence of suicide risk was 19.6%. |

| Zhong | 2014 | Lima, Peru | 1517 pregnant women |

Cross-sectional | SI: PHQ-9 and EPDS | Based on the PHQ-9 and EPDS, 15.8% and 8.8% of participants reported SI. |

AAS = Abuse Assessment Screen, AKUADS = Aga Khan University Anxiety and Depression Scale, BSI = Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation, CI = confidence interval, CIS-R = Structured Clinical Interview-Revised Edition, CSR = current suicide risk, EPDS = Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, HAD = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, HRSD = Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, IPV = intimate partner violence, IRR = incidence rate ratio, MINI = Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview, MOODS-SR = Mood Spectrum Self-Report, PHQ = Patient Health Questionnaire, PRIME-MD = Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders, SCID-I = Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, SI = suicidal ideation, SRQ = Self-Report Questionnaire, USA = United States of America

Prevalence estimates

Suicidal ideation

The reported prevalence of antepartum suicidal ideation varied widely across the studies ranging from 3–33%. Overall, the highest prevalence estimates of antepartum suicidal ideation (23–33%) have been reported from studies conducted in the U.S. (Alhusen et al., 2015, Newport et al., 2007). Furthermore, considerable variability in prevalence of antepartum suicidal ideation appears to exist across the U.S. with high reported prevalence estimates for pregnant women residing in urban communities (23–33%) compared to those residing in rural and suburban communities (3–4%) (Gavin et al., 2011, Melville et al., 2010, Kim et al., 2015).

Prevalence estimates of suicidal ideation from studies conducted in other countries (i.e., Bangladesh, Brazil, Italy, Pakistan, and Peru) ranged from 5–20%. Compared to the cross-national estimate in the general population of 9.2% (Nock et al., 2008), these prevalence estimates suggest that suicidal ideation may be more common among pregnant women than the general population.

The prevalence of antepartum suicidal ideation also varies quite considerably by maternal race/ethnicity and age. For example, in a retrospective cohort study of 22,118 pregnant women in Illinois, U.S., Kim et al. (Kim et al., 2015) found that suicidal ideation was more prevalent among non-white women (5.7%) compared with white women (2.8%, p<0.001). A similar pattern of higher prevalence of antepartum suicidal ideation among non-white women was observed in a study conducted in the Pacific Northwest. In their study of women receiving prenatal care at a University hospital, Gavin et al. (Gavin et al., 2011) noted that non-Hispanic white women had a 49% reduced odds of antepartum suicidal ideation as compared with women of other races/ethnicities (OR=0.51, 95% CI: 0.26–0.99). Using a linked vital statistics-patient discharge database for California, Gandhi et al (Gandhi et al., 2006) found that women who attempted suicide during pregnancy were less likely to be non-Hispanic white (OR=0.82, 95% CI: 0.71–0.94, p=0.005) compared to pregnant women who did not attempt suicide.

The prevalence of antepartum suicidal ideation also appears to vary by maternal age. Kim et al. noted that younger maternal age (mean age 30.9 vs. 31.9 years, p=0.001) was statistically significantly associated with antepartum suicidal ideation. Similarly, Gandhi et al., in their analysis of California data, found increased odds of suicide attempts among those women ≤20 years of age (OR=2.88, 95% CI: 2.48–3.36, p<0.001) as compared with older women.

Suicide

Although rates of maternal deaths attributable to obstetrically related events, such as cardiac disease, infection, and hemorrhage, have declined over the past two decades, rates of maternal deaths attributable to suicide have remained unchanged (Shadigian and Bauer, 2005, Palladino et al., 2011). The first study that attempted to evaluate maternal deaths attributable to suicide was conducted by Appleby (Appleby, 1991). Using retrospective vital records from England and Wales during the years from 1973 to 1984 the author (Appleby, 1991) found that mortality attributable to suicide was 20-fold lower among pregnant and postpartum women compared with matched non-pregnant population (mortality ratio (MR)=0.05, 95% CI: 0.029–0.084). Marzuk et al. (Marzuk et al., 1997) found similar results in New York City, reporting an age- and race-adjusted suicide risk of 0.33 (95% CI: 0.12–0.72) among pregnant women compared to non-pregnant women. More recently in 2011, Samandari et al. (Samandari et al., 2011) reported a mortality ratio calculated from North Carolina population data of 0.27 (95% CI: 0.11–0.66). An analysis of population data in Finland showed that the suicide attributable MR was only 16% lower for pregnant women as compared with non-pregnant women (MR=0.84, 95% CI: 0.69–1.01) (Gissler et al., 2005). When considered in total, the evidence suggests that pregnant women are more likely than the general population to experience suicidal ideation, but less likely than their non-pregnant counterparts to commit suicide.

Risk factors associated with antepartum suicidal ideation

In this section, we provide a brief summary of studies that have assessed risk factors associated with antepartum suicidal ideation.

History of abuse

The literature provides evidence that a history of abuse, including adverse childhood experiences and intimate partner violence, are associated with antepartum suicidal ideation. In 1996, Farber et al. (Farber et al., 1996) found statistically significant differences in the prevalence of suicidal ideation among pregnant women with a history of childhood abuse versus those with no history of childhood abuse (physical abuse: 33% vs. 17%, p<0.05; sexual abuse: 32% vs. 16%, p<0.03; physical and sexual abuse: 32% vs. 17%, p<0.04). More recently, Copersino et al. (Copersino et al., 2008) conducted a cross-sectional study among drug-dependent pregnant women and found lifetime abuse to be statistically significantly associated with antepartum suicidal ideation. For instance, the authors noted that histories of emotional abuse (OR=3.21, 95% CI: 1.18–8.73), physical abuse (OR=6.98, 95% CI: 2.53–19.24), and sexual abuse (OR=6.06, 95% CI: 1.92–19.11) were all associated with increased odds of antepartum suicidal ideation in this high risk obstetric population (Copersino et al., 2008). Finally, in a population-based study of pregnant teens in Brazil, Coelho et al. (Coelho et al., 2014) found increased odds for suicidality among teens who reported physical abuse within the last 12 months (OR=2.36, 95% CI: 1.24–4.47) as compared with their non-abused counterparts.

A growing body of evidence shows the relationship between exposure to intimate partner violence during pregnancy and risk of suicidal ideation. Asad et al. (Asad et al., 2010), in their study among Pakistani pregnant women, found that physical/sexual abuse occurring six months prior to or during the pregnancy was associated with 2.35-fold increased odds of maternal suicidal ideation (OR=2.35, 95% CI: 1.55–3.57). Furthermore, the authors reported that maternal exposure to verbal abuse was associated with 4.20-fold increased odds (OR=4.20, 95% CI: 2.47–7.15) of suicidal ideation. Alhusen et al. (Alhusen et al., 2015) also found a strong association between intimate partner violence and suicidal ideation among pregnant women in the U.S. Using multivariate logistic regression, the authors found that intimate partner violence during pregnancy was associated with 9.37-fold increased odds of suicidal ideation (OR=9.37, 95% CI: 3.41–25.75) (Alhusen et al., 2015). Ely et al. (Ely et al., 2011) and Fisher et al. (Fisher et al., 2013) reported similar associations between intimate partner violence and suicidal ideation in their samples of pregnant women in the U.S. and Vietnam, respectively. The evidence is quite consistent in documenting maternal history of abuse as an important risk factor for suicidality in pregnancy.

Cultural/social influences

Socio-cultural factors including gender norms, family dynamics, and cultural differences are important determinants of suicidal behaviors in populations and are also of particular significance when considering the health of pregnant women. For example, the literature suggests that having an unplanned pregnancy may be a risk factor for suicidal ideation (Sein Anand et al., 2005, Ishida et al., 2010, Newport et al., 2007). In a prospective cohort study of pregnant women in Atlanta, US, Newport et al. (Newport et al., 2007) found that unplanned pregnancy was associated with nearly 3-fold increased odds of suicidal ideation (OR=2.97, 95% CI: 1.35–6.55). These results were corroborated by some (Sein Anand et al., 2005, Ishida et al., 2010) though not all (Benute et al., 2011, Coelho et al., 2014) investigators. An additional related risk factor for suicidal ideation is abortion intention. In their study of pregnant teens, Coelho et al. (Coelho et al., 2014) reported that abortion intention in the current pregnancy was associated with a 2.84-fold increased risk of suicidality (OR=2.84, 95% CI: 1.67–4.83). These results were consistent with those reported from a study of adult pregnant women (da Silva et al., 2012). Furthermore, Misic-Pavkov et al. (Misic-Pavkov, 1990) found that among pregnant women seeking an abortion, the inaccessibility of legal pregnancy termination was associated with an increased risk of suicide capability as measured by the Potential Suicide Personality Inventory (PSPI) scale. Finally, low social support has been shown to be associated with suicidal ideation. Briefly, Coelho et al. reported that low social support is associated with a 2.30-fold increased risk of antepartum suicidal ideation among pregnant teens (OR=2.30, 95% CI: 1.39–3.82) (Coelho et al., 2014).

Socioeconomic status

The literature suggests that markers of socioeconomic status may also be associated with the risk of antepartum suicidal ideation. Several studies reported data showing that lower educational attainment is associated with an increased risk of suicidal ideation among pregnant women (Asad et al., 2010, da Silva et al., 2012, Coelho et al., 2014, Alhusen et al., 2015, Newport et al., 2007, Mauri et al., 2012, Gandhi et al., 2006). For example, in a prospective cohort study of pregnant women in Italy, Mauri et al. (Mauri et al., 2012) found that low educational attainment (<12 years education) was associated with 2.90-fold increased odds of suicidality during pregnancy (OR=2.90, 95% CI: 1.59–5.30). Similarly, da Silva et al. (da Silva et al., 2012) conducted a multivariate logistic regression analysis and found that those women who had not finished elementary school had an increased risk of suicidal ideation compared to those who did (OR=2.84, 95% CI: 1.51–5.34). These findings have been corroborated by a number of other investigators (Asad et al., 2010, Coelho et al., 2014, Alhusen et al., 2015, Newport et al., 2007, Gandhi et al., 2006).

In addition to education, authors identified other indicators of socioeconomic status that may be associated with suicidal ideation during pregnancy. These indicators include household income, type of health insurance, and homelessness. Alhusen et al. (Alhusen et al., 2015) found that women reporting antepartum suicidal ideation were more likely to have household incomes <$10,000 compared to women without antepartum suicidal ideation (63.2% vs. 36.8%, p<0.001). Regarding insurance, Gandhi et al. (Gandhi et al., 2006) reported that, compared to women with public health insurance, those with private health insurance had reduced odds of attempted suicide (OR=0.68, 95% CI: 0.57–0.80). Finally, in their retrospective cohort study of drug-dependent pregnant women, Copersino et al. (Copersino et al., 2008) found that homelessness was associated with substantially increased odds of suicidal ideation (OR=6.75, 95% CI: 1.35–33.79). On balance, available evidence suggests that various measures of maternal socioeconomic status are associated with the risk of antepartum suicidal ideation and other measures of suicidality.

Demographic factors

There are additional demographic factors that appear to be associated with antepartum suicidal ideation, one of which is marital/relationship status. Ishida et al. (Ishida et al., 2010) found that pregnant women who had never been in a marital union were 14.82-fold more likely to report suicidal ideation than women in a union (OR=14.82, 95% CI: 2.45–89.72). Among drug-dependent pregnant women, being married was a protective factor for suicidal ideation, decreasing its risk by 4-fold, when compared to their non-married counterparts (OR=0.24, 95% CI: 0.07–0.83) (Copersino et al., 2008). These results were replicated in multiple studies (da Silva et al., 2012, Huang et al., 2012, Alhusen et al., 2015, Newport et al., 2007, Kim et al., 2015, Gandhi et al., 2006). This association might in part be due to unplanned pregnancies. In the U.S. over half of pregnancies are unplanned, potentially increasing the likelihood of an emergence of suicidal ideation and other psychiatric disorders (Brand and Brennan, 2009).

Other demographics factors that have been found to be associated with an increased risk of antepartum suicidal ideation are non-English primary language, multiparity, and lack of religious belief. Kim et al. (Kim et al., 2015) found that the proportion of English speakers was statistically significantly higher among women without suicidal ideation than among women reporting suicidal ideation (92.3% vs. 87.6%, p=0.007). In their cross-sectional analysis of data from a cohort of pregnant women in Brazil, Farias et al. (Farias et al., 2013) reported a higher prevalence of suicide risk among multiparous women (OR=2.46, 95% CI: 1.22–4.93) compared with primiparas. Similarly, Gandhi et al. (Gandhi et al., 2006) found that women with 2 children and those with 3+ children had increased risk of attempted suicide (OR=1.22, 95% CI: 1.06–1.41; OR=1.29, 95% CI: 1.09–1.52; respectively) compared with nulliparas. Finally, in a cross-sectional analysis of pregnant women in Brazil, Benute et al. (Benute et al., 2011) reported elevated risk of suicide among women indicating no religious belief as compared to self-reported religious women (94.1% vs. 71.4%, p=0.012).

Comorbid psychiatric conditions

The majority of studies that identified risk factors for antepartum suicidal ideation reported at least one comorbid psychiatric disorder as a risk factor. These psychiatric disorders include depression (Alhusen et al., 2015, Asad et al., 2010, Coelho et al., 2014, Copersino et al., 2008, da Silva et al., 2012, Farias et al., 2013, Gavin et al., 2011, Gelaye et al., 2015, Mauri et al., 2012, Newport et al., 2007), anxiety (Asad et al., 2010, da Silva et al., 2012, Farias et al., 2013, Coelho et al., 2014, Newport et al., 2007), substance use disorders (Eggleston et al., 2009, Newport et al., 2007, Gandhi et al., 2006, Copersino et al., 2008, Huang et al., 2012, Czeizel, 2011), post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Eggleston et al., 2009, Copersino et al., 2008), panic disorder (Coelho et al., 2014), and lifetime suicidality (Mauri et al., 2012). Alhusen et al. (Alhusen et al., 2015) found that clinically significant antepartum depressive symptoms (Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale score >12) was associated with a 17-fold increase in odds of suicidal ideation even after adjusting for demographic factors and intimate partner violence during pregnancy (OR=17.04, 95% CI: 2.10–38.27). Additionally, Coelho et al. (Coelho et al., 2014) reported that the following psychiatric disorders were statistically significantly associated with suicidal ideation among their population of pregnant teenagers: major depressive disorder (OR=2.41, 95% CI: 1.35–4.30), generalized anxiety disorder (OR=2.63, 95% CI: 1.30–5.32), panic disorder (OR=6.44, 95% CI: 1.72–24.16), and social anxiety disorder (OR=3.44, 95% CI: 1.46–8.15). In general, several investigators noted that pregnant women who endorsed suicidal ideation were more likely to have comorbid current and lifetime mental health disorders than those who did not endorse suicidal ideation (Alhusen et al., 2015, Asad et al., 2010, Coelho et al., 2014, Copersino et al., 2008, da Silva et al., 2012, Farias et al., 2013, Gavin et al., 2011, Gelaye et al., 2015, Mauri et al., 2012, Newport et al., 2007)

Consequences of antepartum suicidal ideation

Antepartum suicidal ideation is associated with a myriad of adverse maternal and infant outcomes (Copersino et al., 2008, Gavin et al., 2011, Lindahl et al., 2005). The majority of studies that have assessed the impact of suicidal ideation during pregnancy on fetal development have done so in the context of self-poisoning. A series of 15 articles were published from the Budapest Monitoring System of Self-Poisoning Pregnant Women that evaluated the potential effects of large doses of drugs on fetal development among pregnant women who attempted suicide (Czeizel et al., 1997, Czeizel et al., 1999, Timmermann et al., 2009, Gidai et al., 2008c, Gidai et al., 2008a, Gidai et al., 2008d, Gidai et al., 2008b, Gidai et al., 2010, Petik et al., 2008a, Petik et al., 2008b, Petik et al., 2012, Timmermann et al., 2008b, Timmermann et al., 2008a, Timmermann et al., 2008c). With regards to congenital anomalies, the primary outcomes of these studies, no statistically significant associations were reported with self-poisoning (Czeizel et al., 1997, Czeizel et al., 1999, Timmermann et al., 2009, Gidai et al., 2008c, Gidai et al., 2008a, Gidai et al., 2008d, Gidai et al., 2008b, Gidai et al., 2010, Petik et al., 2008a, Petik et al., 2008b, Petik et al., 2012, Timmermann et al., 2008b, Timmermann et al., 2008a, Timmermann et al., 2008c). The majority of drugs used for self-poisoning in these studies were also not associated with mental retardation, low birth weight, or preterm birth. However, investigators found that large doses of Tardyl (combination of amobarbital, glutethimide, and promethazine) were associated with an increased prevalence of mental retardation among exposed infants compared to their unexposed siblings (29.6% vs. 0%, p<0.0001) (Petik et al., 2012) and that self-poisoning during pregnancy was associated with increased odds of very early fetal loss (OR=6.09, 95% CI: 3.82–9.71) and decreased odds of live birth (OR=0.08, 95% CI: 0.23–0.72) (Czeizel et al., 1999).

Additionally some (Gandhi et al., 2006), but not all (Gandhi et al., 2006), investigators have reported elevated risk of adverse birth outcomes among women with a history of antepartum suicidal ideation. For instance, Gandhi et al. (Gandhi et al., 2006) found that infants born to women who attempted suicide during pregnancy were more likely to be low birth weight (<2500 g) (OR=1.25, 95% CI: 1.08–1.44) and have respiratory distress syndrome (OR=1.41, 95% CI: 1.07–1.86). McClure et al. (McClure et al., 2011) reported that risks for preterm birth (OR=1.34, 95% CI: 1.01–1.77), low birth weight (OR=1.49, 95% CI: 1.04–2.12), and circulatory system congenital anomalies (OR=2.17, 95% CI: 1.02–4.59) were elevated among gravidas who attempted self-poisoning during pregnancy as compared with those who did not. Regarding suicidal ideation more broadly, Hodgkinson et al. (Hodgkinson et al., 2010) found that infants of mothers reporting depressive symptoms with suicidal ideation weighed 239.5 g (95% CI: 3.9–475.1) less on average than infants born to mothers reporting depressive symptoms without suicidal ideation. Thus, there is substantial evidence suggesting that suicidal ideation and attempts are associated with severe consequences for fetal development and perinatal outcomes.

There has been substantially less research evaluating the influences of antepartum suicidal ideation on maternal obstetric heath outcomes, though research among the general population is likely applicable. Simon et al. (Simon et al., 2013) in their study among outpatients of Seattle-based health maintenance organization found that suicidal ideation (assessed using response to item 9 of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9) was associated increased risk of suicide attempt or death. Of note, the authors reported that the cumulative risk of suicide death over one year increased by 92% among patients reporting suicidal ideation and this excess risk (Hazard Ratio=1.92, 95% CI: 1.53–2.41) emerged over several days and continued to increase for several months. Other investigators have noted that suicidal ideation is an important predictor of suicide planning, attempt, and completion of suicide. In their cross-national assessment of suicidal ideation, plans, and attempts, Nock et al. (Nock et al., 2008) reported that, among those who endorse suicide ideation, the probability of ever making a suicide plan was 33.6% and of ever making a suicide attempt was 29.0%. Additionally, the investigators stated that over 60% of the transitions from suicidal ideation to attempt occurred within the first year of onset of ideation (Nock et al., 2008).

Screening for suicidal ideation during pregnancy

One of the proposed strategies to reduce suicide during pregnancy has been to identify and target subgroups of individuals at greatest risk. However, there are few screening instruments for antepartum suicidal ideation. As suicidal ideation is one of the diagnostic symptoms for antepartum depression, suicidal ideation is often assessed along with depression screening rather than separately. The two most widely used screeners to assess suicidal ideation are item 9 of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scale (PHQ-9) and item 10 of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). Specifically, item 9 of the PHQ-9 assesses suicidal ideation over the past 14 days and item 10 of the EPDS assesses suicidal ideation over the past 7 days (Zhong et al., 2014). Zhong et al. (Zhong et al., 2014) evaluated the concordance of these two items among pregnant women in Peru and found high concordance (84.2%), but moderate agreement (the Cohen’s kappa=0.42) for the two items when assessed in the same population. Antepartum suicidal ideation was reported among 15.8% participants on PHQ-9 and 8.8% on EPDS (Zhong et al., 2014). Another group of investigators compared item 10 of the EPDS to the Mood Spectrum Self-Report (MOODS-SR) (Mauri et al., 2012) in a sample of pregnant women in Italy. The investigators found that, among women who endorsed suicidality with the EPDS, 28% also endorsed suicidality with the MOODS-SR and among those who endorsed suicidality with the MOODS-SR, 46.9% endorsed suicidality with the EPDS (Mauri et al., 2012). Finally, Newport et al. (Newport et al., 2007) compared two additional screening tools: the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD). The investigators found that among 383 pregnant women, 29.2% endorsed suicidal ideation on the BDI and 16.9% on the HRSD, with 33.0% endorsing suicidal ideation on at least one scale and 13.1% on both scales (Newport et al., 2007). Relative to the HRSD, the sensitivity of the BDI for identifying suicidal ideation was 77.8%, while the sensitivity of the HRSD relative to the BDI was 44.9% (Newport et al., 2007). In sum, there is considerable variability in antepartum suicidal ideation prevalence across studies depending on screening instrument used. The few screening instruments that exist are limited as they were primarily developed to measure antepartum and postpartum depression, not antepartum suicidal ideation. Given that a substantial proportion of women with suicidal ideation do not meet clinical thresholds of depression (Zhong et al., 2014), and given the current burden of suicidal ideation, efforts to design and enhance the psychometric properties and validity of antepartum suicidal ideation screening questionnaires are warranted.

In addition to the use of questionnaires, the use of diagnostic biomarkers may provide novel insights into the etiopathphysiology of suicidal ideation with and without concomitant mood and anxiety disorders. In two recent studies, investigators evaluated associations between suicidal ideation during pregnancy and various biomarkers, finding interesting results (Farias et al., 2013, Vaz et al., 2014). In 2013, Farias et al. (Farias et al., 2013) found that pregnant women with current suicide risk (assessed using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview) had higher mean total cholesterol (169.2 vs. 159.2 mg/dL, p=0.017), high-density lipoprotein (HDL) (50.4 vs. 47.7 mg/dL , p=0.031), and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) (102.8 vs. 95.6 mg/dL, p=0.022) compared to those without current suicide risk. Furthermore, in 2014, Vaz et al. (Vaz et al., 2014) reported a higher likelihood of suicide risk among pregnant women with higher serum omega-6 fatty acids: arachidonic acid (OR=1.45, 95% CI: 1.02–2.07) and adrenic acid (OR=1.43, 95% CI: 1.01–2.04). Recently Fung et al., (Fung et al., 2015) assessed the relation between antepartum depression and maternal early pregnancy serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDF) concentration—a neurotrophin that is involved in neuronal cell growth, survival, and synaptic plasticity. After adjusting for confounding, women whose serum BDNF levels were in the lowest three quartiles (<17.32 ng/ml) had 1.61-fold increased odds (OR = 1.61, 95% CI: 1.13, 2.30) of antepartum depression as compared with women whose BDNF levels were in the highest quartile (>25.31 ng/ml). A decreased expression of BDNF in antepartum depression may lead to reduced neuronal plasticity in the brain of individuals with antepartum suicidal ideation. Use of these putative biomarkers coupled with screening questionnaires may potentially improve screening and diagnosis of antepartum suicidal ideation.

Discussion

Overall, available evidence indicates that pregnant women are more likely than the general population to endorse suicidal ideation. Additionally, a number of risk factors for antepartum suicidal ideation were identified including intimate partner violence, <12 years education, and major depressive disorder. Antepartum suicidal ideation is a complex phenomenon, which results from the interaction of several psychosocial and neurobiological factors. As shown in Figure 2, antepartum suicidal behavior can be described using the stress-diathesis model. The stress-diathesis model of antepartum suicidal behavior integrates the neurobiological, psychosocial, and psychopathological risk factors of suicidal behavior (Lee and Kim, 2011). In sum, it is critical to use a rigorous and multidimensional analytic approach to detect suicidal ideation risk during pregnancy. On the basis of this comprehensive systemic review of the available literature, we note that there may be substantial clinical benefit for implementing antepartum suicidal ideation screening programs to identify women at high risk of suicidal behaviors.

Figure 2.

The stress–diathesis model of antepartum suicidal ideation and behavior

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this review include an extensive systematic search of available literature on five online databases and an epidemiologically informed summary of the findings. Despite these strengths, the studies included in this systematic review have some limitations that merit consideration. Of the 57 included studies, 28 were from retrospective studies, 19 were from cross-section and 1 study from case-control study. Hence, the majority of the studies are subject to possible recall bias. In addition, instruments used to assess suicidal ideation varied across studies and could have accounted for heterogeneity in research findings. There is a clear need for innovative approaches to improve screening and detection of antepartum suicidal ideation.

Implications

Antepartum suicidal ideation is an important and common complication of pregnancy that requires increased attention given its association with many adverse maternal, fetal, and infant outcomes. Findings from this systematic review suggest that improving screening instruments for identifying at risk women are urgently needed. Additionally clinical protocols for risk reduction and suicide prevention beyond major psychiatric illnesses are needed for some high-risk pregnant women. Finally, future studies should continue to examine the etiopathophysiology and consequences of antepartum suicidal ideation with and without concomitant psychiatric disorders so that improved pharmacological and nonpharmacological therapeutic approaches can be developed and implemented in the care of at-risk pregnant women.

The National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention Research (Action Alliance) Prioritization Task Force has recently published a series of articles with an urgent call for action and aspirational goals designed to mitigate the risk of suicide. These are commendable and important efforts dedicated towards suicide prevention. However, as this epidemiologic review has demonstrated up to 33.0% of women endorse suicidal ideation during pregnancy; and thus they represent an important, though often neglected, population when it comes to suicide prevention efforts. Prevention strategies such as those advocated by Action Alliance should consider pregnant women as a target population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by awards from the National Institutes of Health, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver Institute of Child Health and Human Development (1R01-HD-059835), and National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities (T37-MD-001449). The National Institutes of Health had no further role in the study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None Declared

REFERENCES

- Alhusen JL, Frohman N, Purcell G. Intimate partner violence and suicidal ideation in pregnant women. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s00737-015-0515-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appleby L. Suicide during pregnancy and in the first postnatal year. British Medical Journal. 1991;302:137–140. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6769.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asad N, Karmaliani R, Sullaiman N, et al. Prevalence of suicidal thoughts and attempts among pregnant Pakistani women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89:1545–1551. doi: 10.3109/00016349.2010.526185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benute GR, Nomura RM, Jorge VM, et al. Risk of suicide in high risk pregnancy: an exploratory study. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2011;57:583–587. doi: 10.1590/s0104-42302011000500019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand SR, Brennan PA. Impact of antenatal and postpartum maternal mental illness: how are the children? Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2009;52:441–455. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181b52930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coelho FM, Pinheiro RT, Silva RA, et al. Parental bonding and suicidality in pregnant teenagers: a population-based study in southern Brazil. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49:1241–1248. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0832-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copersino ML, Jones H, Tuten M, Svikis D. Suicidal Ideation Among Drug-Dependent Treatment-Seeking Inner-City Pregnant Women. J Maint Addict. 2008;3:53–64. doi: 10.1300/J126v03n02_07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czeizel AE. Attempted suicide and pregnancy. J Inj Violence Res. 2011;3:45–54. doi: 10.5249/jivr.v3i1.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czeizel AE, Timar L, Susanszky E. Timing of suicide attempts by self-poisoning during pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1999;65:39–45. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(99)00007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czeizel AE, Tomcsik M, Czeizel AE, Timar L. Teratologic evaluation of 178 infants born to mothers who attempted suicide by drugs during pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1997;90:195–201. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00216-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva RA, Da Costa Ores L, Jansen K, et al. Suicidality and associated factors in pregnant women in Brazil. Community Ment Health J. 2012;48:392–395. doi: 10.1007/s10597-012-9495-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggleston AM, Calhoun PS, Svikis DS, Tuten M, Chisolm MS, Jones HE. Suicidality, aggression, and other treatment considerations among pregnant, substance-dependent women with posttraumatic stress disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2009;50:415–423. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ely GE, Nugent WR, Cerel J, Vimbba M. The relationship between suicidal thinking and dating violence in a sample of adolescent abortion patients. Crisis. 2011;32:246–253. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farber EW, Herbert SE, Reviere SL. Childhood abuse and suicidality in obstetrics patients in a hospital-based urban prenatal clinic. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1996;18:56–60. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(95)00098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farias DR, De Jesus Pereira Pinto T, Teofilo MMA, et al. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in the first trimester of pregnancy and factors associated with current suicide risk. Psychiatry Research. 2013;210:962–968. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J, Tran TD, Biggs B, Dang TH, Nguyen TT, Tran T. Intimate partner violence and perinatal common mental disorders among women in rural Vietnam. Int Health. 2013;5:29–37. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihs012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung J, Gelaye B, Zhong QY, et al. Association of decreased serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) concentrations in early pregnancy with antepartum depression. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:43. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0428-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi SG, Gilbert WM, Mcelvy SS, et al. Maternal and neonatal outcomes after attempted suicide. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:984–990. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000216000.50202.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin AR, Tabb KM, Melville JL, Guo Y, Katon W. Prevalence and correlates of suicidal ideation during pregnancy. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2011;14:239–246. doi: 10.1007/s00737-011-0207-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelaye B, Barrios YV, Zhong Q-Y, et al. Association of poor subjective sleep quality with suicidal ideation among pregnant peruvian women. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile S. Suicidal mothers. J Inj Violence Res. 2011;3:90–97. doi: 10.5249/jivr.v3i2.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidai J, Acs N, Banhidy F, Czeizel AE. An evaluation of data for 10 children born to mothers who attempted suicide by taking large doses of alprazolam during pregnancy. Toxicol Ind Health. 2008a;24:53–60. doi: 10.1177/0748233708089017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidai J, Acs N, Banhidy F, Czeizel AE. No association found between use of very large doses of diazepam by 112 pregnant women for a suicide attempt and congenital abnormalities in their offspring. Toxicol Ind Health. 2008b;24:29–39. doi: 10.1177/0748233708089019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidai J, Acs N, Banhidy F, Czeizel AE. A study of the effects of large doses of medazepam used for self-poisoning in 10 pregnant women on fetal development. Toxicol Ind Health. 2008c;24:61–68. doi: 10.1177/0748233708089016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidai J, Acs N, Banhidy F, Czeizel AE. A study of the teratogenic and fetotoxic effects of large doses of chlordiazepoxide used for self-poisoning by 35 pregnant women. Toxicol Ind Health. 2008d;24:41–51. doi: 10.1177/0748233708089018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidai J, Acs N, Banhidy F, Czeizel AE. Congenital abnormalities in children of 43 pregnant women who attempted suicide with large doses of nitrazepam. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19:175–182. doi: 10.1002/pds.1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gissler M, Berg C, Bouvier-Colle MH, Buekens P. Injury deaths, suicides and homicides associated with pregnancy, Finland 1987–2000. Eur J Public Health. 2005;15:459–463. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkinson SC, Colantuoni E, Roberts D, Berg-Cross L, Belcher HME. Depressive Symptoms and Birth Outcomes among Pregnant Teenagers. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 2010;23:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Faisal-Cury A, Chan Y-F, Tabb K, Katon W, Menezes PR. Suicidal ideation during pregnancy: Prevalence and associated factors among low-income women in São Paulo, Brazil. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2012;15:135–138. doi: 10.1007/s00737-012-0263-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida K, Stupp P, Serbanescu F, Tullo E. Perinatal risk for common mental disorders and suicidal ideation among women in Paraguay. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2010;110:235–240. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Jr, Rudd MD, Rouleau MR, Wagner KD. Parameters of suicidal crises vary as a function of previous suicide attempts in youth inpatients. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:876–880. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200007000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Borges G, Nock M, Wang PS. Trends in suicide ideation, plans, gestures, and attempts in the United States, 1990–1992 to 2001–2003. JAMA. 2005;293:2487–2495. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.20.2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JJ, La Porte LM, Saleh MP, et al. Suicide risk among perinatal women who report thoughts of self-harm on depression screens. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:885–893. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BH, Kim YK. Potential peripheral biological predictors of suicidal behavior in major depressive disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35:842–847. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl V, Pearson JL, Colpe L. Prevalence of suicidality during pregnancy and the postpartum. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2005;8:77–87. doi: 10.1007/s00737-005-0080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzuk PM, Tardiff K, Leon AC, et al. Lower risk of suicide during pregnancy. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:122–123. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauri M, Oppo A, Borri C, Banti S. SUICIDALITY in the perinatal period: comparison of two self-report instruments. Results from PND-ReScU. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2012;15:39–47. doi: 10.1007/s00737-011-0246-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcclure CK, Patrick TE, Katz KD, Kelsey SF, Weiss HB. Birth outcomes following self-inflicted poisoning during pregnancy, California, 2000 to 2004. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2011;40:292–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2011.01250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melville JL, Gavin A, Guo Y, Fan MY, Katon WJ. Depressive disorders during pregnancy: Prevalence and risk factors in a large urban sample. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2010;116:1064–1070. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f60b0a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misic-Pavkov G. [Evaluation of the level of suicidal tendencies in women with unwanted pregnancies] Med Pregl. 1990;43:257–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newport DJ, Levey LC, Pennell PB, Ragan K, Stowe ZN. Suicidal ideation in pregnancy: Assessment and clinical implications. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2007;10:181–187. doi: 10.1007/s00737-007-0192-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, et al. Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192:98–105. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oates M. Perinatal psychiatric disorders: a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality. Br Med Bull. 2003;67:219–229. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldg011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organization WH. Preventing suicide: A global imperative. In, Luxembourg. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Palladino CL, Singh V, Campbell J, Flynn H, Gold KJ. Homicide and suicide during the perinatal period: findings from the National Violent Death Reporting System. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:1056–1063. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31823294da. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petik D, Acs N, Banhidy F, Czeizel AE. A study of the potential teratogenic effect of large doses of promethazine used for a suicide attempt by 32 pregnant women. Toxicol Ind Health. 2008a;24:87–96. doi: 10.1177/0748233708089003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petik D, Czeizel B, Banhidy F, Czeizel AE. A study of the risk of mental retardation among children of pregnant women who have attempted suicide by means of a drug overdose. J Inj Violence Res. 2012;4:10–19. doi: 10.5249/jivr.v4i1.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petik D, Timmermann G, Czeizel AE, Acs N, Banhidy F. A study of the teratogenic and fetotoxic effects of large doses of amobarbital used for a suicide attempt by 14 pregnant women. Toxicol Ind Health. 2008b;24:79–85. doi: 10.1177/0748233708093314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samandari G, Martin SL, Kupper LL, Schiro S, Norwood T, Avery M. Are pregnant and postpartum women: at increased risk for violent death? Suicide and homicide findings from North Carolina. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15:660–669. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0623-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sein Anand J, Chodorowski Z, Ciechanowicz R, Klimaszyk D, Lukasik-Glebocka M. Acute suicidal self-poisonings during pregnancy. Przegl Lek. 2005;62:434–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadigian E, Bauer ST. Pregnancy-associated death: a qualitative systematic review of homicide and suicide. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2005;60:183–190. doi: 10.1097/01.ogx.0000155967.72418.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon GE, Rutter CM, Peterson D, et al. Does response on the PHQ-9 Depression Questionnaire predict subsequent suicide attempt or suicide death? Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64:1195–1202. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmermann G, Acs N, Banhidy F, Czeizel AE. A study of teratogenic and fetotoxic effects of large doses of meprobamate used for a suicide attempt by 42 pregnant women. Toxicol Ind Health. 2008a;24:97–107. doi: 10.1177/0748233708089015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmermann G, Acs N, Banhidy F, Czeizel AE. A study of the potential teratogenic effects of large doses of drugs rarely used for a suicide attempt during pregnancy. Toxicol Ind Health. 2008b;24:121–131. doi: 10.1177/0748233708089002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmermann G, Acs N, Banhidy F, Czeizel AE. Congenital abnormalities of 88 children born to mothers who attempted suicide with phenobarbital during pregnany: the use of a disaster epidemiological model for the evaluation of drug teratogenicity. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18:815–825. doi: 10.1002/pds.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmermann G, Czeizel AE, Banhidy F, Acs N. A study of the teratogenic and fetotoxic effects of large doses of barbital, hexobarbital and butobarbital used for suicide attempts by pregnant women. Toxicol Ind Health. 2008c;24:109–119. doi: 10.1177/0748233708089004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Bergh BR, Mulder EJ, Mennes M, Glover V. Antenatal maternal anxiety and stress and the neurobehavioural development of the fetus and child: links and possible mechanisms. A review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29:237–258. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaz JS, Kac G, Nardi AE, Hibbeln JR. Omega-6 fatty acids and greater likelihood of suicide risk and major depression in early pregnancy. J Affect Disord. 2014;152–154:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.04.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong QY, Gelaye B, Rondon MB, et al. Using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) to assess suicidal ideation among pregnant women in Lima, Peru. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00737-014-0481-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.