Abstract

Mitochondria are enriched in subcellular regions of high energy consumption, such as axons and pre-synaptic nerve endings. Accumulating evidence suggests that mitochondrial maintenance in these distal structural/functional domains of the neuron depends on the “in-situ” translation of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial mRNAs. In support of this notion, we recently provided evidence for the axonal targeting of several nuclear-encoded mRNAs, such as cytochrome c oxidase, subunit 4 (COXIV), ATP synthase, H+ transporting and mitochondrial Fo complex, subunit C1 (ATP5G1). Furthermore, we showed that axonal trafficking and local translation of these mRNAs plays a critical role in the generation of axonal ATP. Using a global gene expression analysis, this study identified a highly diverse population of nuclear-encoded mRNAs that were enriched in the axon and presynaptic nerve terminals. Among this population of mRNAs, fifty seven were found to be at least two fold more abundant in distal axons, as compared with the parental cell bodies. Gene ontology analysis of the nuclear-encoded mitochondrial mRNAs suggested functions for these gene products in molecular and biological processes, including but not limited to oxidoreductase and electron carrier activity and proton transport. Based on these results, we postulate that local translation of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial mRNAs present in the axons may play an essential role in local energy production and maintenance of mitochondrial function.

Keywords: Microarray analyses, mRNAs, subcellular localization, superior cervical, ganglion, Campenot cell culture chambers

1. INTRODUCTION

It is now well-established that the synaptic nerve terminals contain large numbers of highly active mitochondria, and that these organelles play a fundamental role in synaptic function (Sheng and Cai, 2012). For example, synaptic transmission requires mitochondrial ATP generation and control of local [Ca2+] levels for neurotransmitter exocytosis, and potentiation of neurotransmitter release (Picard, 2015). Moreover, it is becoming well-recognized that mitochondrial dysfunction plays an important role in the pathophysiology of several major psychiatric disorders, while mitochondrial fragmentation has been shown to be one of the hallmarks of neurodegeneration (Lin and Beal, 2006). Historically, it has been accepted that nuclear-encoded proteins destined for mitochondria are translated in the cytoplasm of the neuronal cell soma and subsequently transported into the organelles located in the distal parts of cells by complex translocation machinery (Lin and Sheng, 2015). However, recent data suggest that nuclear-encoded mRNAs encoding mitochondrial proteins, such as COXIV and ATP5GI are targeted to the distal axon, and that the local synthesis of these proteins plays a key role in the maintenance of mitochondrial activity (Aschrafi et al., 2010; Natera-Naranjo et al., 2012). Hence, the local synthesis of mitochondrial proteins establishes an intimate link between translation and translocation to ensure the viability of the organelle located in these distal structural / functional neuronal domains (Gioio et al., 2001; Margeot et al., 2002). These observations also add to previous findings that axonal growth is dependent on the local synthesis of a multitude of proteins including metabolic as well as structural and cytoskeletal proteins (Holt and Schuman, 2013; Shane SS et al., 2015). In this regard, extracellular cues direct growth cones by inducing rapid changes in local protein expression, and developing axons contain the necessary translational machinery and specific mRNAs to support axonal growth and differentiation. Indeed, some of the first identified functions of axonal protein synthesis were intricately linked to its ability to mediate local translation of mRNAs that encode the cytoskeletal proteins in growing axons (Scott et al., 2015). Given the significance of the local translation of mitochondrial mRNAs in axonal outgrowth and maintenance, the present study was designed to identify the composition of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial mRNAs in the distal axons. Following a microarray approach and bioinformatic analysis, we identified 57 mRNAs that are highly enriched in these neuronal compartments. Quantitative PCR and in situ hybridization facilitated the validation and visualization of a subset of these mRNAs to the axons of SCG neurons.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1 Neuronal Cell Culture

Cells were prepared from superior cervical ganglia (SCG) and were cultured as previously described (Hillefors et al., 2007). Briefly, SCG were dissected from three-day-old Sprague Dawley rat pups and dissociated using the Miltenyi Biotec gentleMACS Dissociator and Neuronal Tissue Dissociation Kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Dissociated primary neurons were plated into the center compartment of a Campenot culture chamber. Neurons were cultured for 14 days in serum-free Neurobasal medium (Invitrogen) containing nerve growth factor (NGF; 50 ng/ml), 20 mM KCl, and 20 U/ml penicillin and 20 mg/ml streptomycin (Hyclone). Growth medium was changed every 3–4 days. After two DIV, 5-fluoro-2’-deoxyuridine (FUDR, 50 µM) was added to the growth medium to inhibit the proliferation of non-neuronal cells and remained in the medium for the duration of the experiments. Phase-contrast microscopy was used to determine whether the side compartments, which contained distal axons, were devoid of neural soma and non-neuronal cells. After 14 DIV, distal axons were harvested from side compartments and parental soma were harvested from center compartments. For in situ hybridization histochemistry (ISH) studies, dissociated SCG neurons were plated on collagen coated Nunc® Lab-Tek® II-CC2™ glass chamber slides (Sigma-Aldrich) and cultured for 6 days before being processed for staining.

2.2 Microarray processing and analysis

RNA samples were prepared from three independent SCG axons and parental soma. Samples were prepared according to Affymetrix protocols (Affymetrix). RNA quality and quantity was monitored using the Bioanalyzer (Agilent) and NanoDrop (ThermoFisher Scientific) respectively. Per RNA labeling, 200 nanograms of total RNA was used in conjunction with the Affymetrix recommended protocol for the GeneChip 2.0 ST chips. The hybridization cocktail containing the fragmented and labeled cDNAs was hybridized to the Affymetrix Rat Genome 2.0 ST GeneChip. The chips were washed and stained by the Affymetrix Fluidics Station using the standard format and protocols as described by Affymetrix. The probe arrays were stained with streptavidin phycoerythrin solution (Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA) and enhanced by using an antibody solution containing 0.5 mg/mL of biotinylated anti-streptavidin (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). An Affymetrix Gene Chip Scanner 3000 was used to scan the probe arrays. Gene expression intensities were calculated using Affymetrix AGCC software. Partek Genomic Suite was used to normalize for Robust Multi-array Average (Robust Multichip Analysis), summarize the probes, log2 transform the data and conduct ANOVA analysis.

2.3 RNA isolation and quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from SCG axons and parental soma using Direct-Zol™ RNA MiniPrep (Zymo Research) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was DNase treated using DNase I (New England Biolabs) according to the manufacturer’s instuctions. The purity of the total RNA preparations from both axons and cell bodies was monitored using the A260/280 ratio of uv-absorbance. The ratios for the RNA preparations were 1.9-2, indicating that the samples were highly pure. Total RNA was reversed transcribed into cDNA using a High Capacity RNA-to-cDNA Kit (Applied Biosystems). qRT-PCR was performed with gene specific primers designed using Primer-BLAST (Ye et al., 2012) and purchased from Invitrogen with the following sequences: Scn3b sense (FW): 5’-TGTGGTGTGACTTGAGGTGAT-3’; Scn3b antisense (RV): 5’-TGTTGGCTCTTCGGTTCAGG-3’; Glrb FW: 5’-CTTTGCAGGTTGGTGAGACC-3’; GlrB RV: 5’-CGGAGGCTTCTTGTTCTTTGC-3’; Cryab FW: 5-ACTTCCCTGAGCCCCTTCTA-3’; Cryab RV:5’-TGCTTCACGTCCAGGTT-CAC–3’; Atp5i FW: 5’-GTCACGGACAAAATGGTGCC-3’; Atp5i RV: 5’-AGTACCGGCCGAACTTGATG-3’; Ndufa1 FW 5’-CGGGGGCAGGAAAAGA-GAG-3’; Ndufa1 RV: 5’-AGATGCGTCTA-TCGCGTTCC-3’; Lyrm2 FW: 5’-AGGCAACAAGTT-CTCCTCCTC-3’; Lyrm2 RV: 5’-GATTGTATCCTCCTCGGTGGC-3’. qRT-PCR analysis of Prss35 was performed with a gene specific QuantiTect® primer (Qiagen). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using VeriQuest SYBR Green quantitative PCR Master Mix (Affymetrix) and a StepOne Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). For each experimental RNA sample, the PCR reactions were run in triplicate. Target mRNA levels were normalized to the geometric mean of β-actin mRNA and 18S mRNA levels as suggested in (Ruijter et al., 2013).

2.4 In situ hybridization histochemistry (ISH)

ISH was performed on fixed SCG neuronal cultures, using the RNAscope® 2.0 High Definition (HD) - RED Assay (Advanced Cell Diagnostics) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Cultured neurons were fixed in 10% formalin for 30 min, dehydrated in increasing concentrations of ethanol (50%, 70%, 100%) and rehydrated (70% ethanol, 50% ethanol, PBS) before applying Pretreat 1 and Pretreat 3 reagents. Target specific riboprobes (rat Cox4i1, RefSeq:NM_017202.1; rat AADAT, RefSeq:NM_017193.1) or a control riboprobe (DapB of Bacillus subtilis strain, GenBank: EF191515.1) (Advanced Cell Diagnostics) were hybridized for 2 h at 40°C, followed by incubation with signal amplification reagents. The hybridized probes were visualized under either bright field or fluorescence microscopy using a Texas Red filter.

2.5 Gene Ontology

Gene categories in the axonally-enriched mitochondrial genes were detected using STRING analysis (Jensen et al., 2009). The STRING database extracts experimental data from BIND, DIP, GRID, HPRD, IntAct, MINT, and PID databases and extracts curated data from Biocarta, BioCyc, GO, KEGG, and Reactome databases. All included GO categories had p-values of less than 0.05 after the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

2.6 Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in Excel. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. p-values were calculated by Student's two-tailed t test, except where Pearson’s correlation is noted.

3. RESULTS

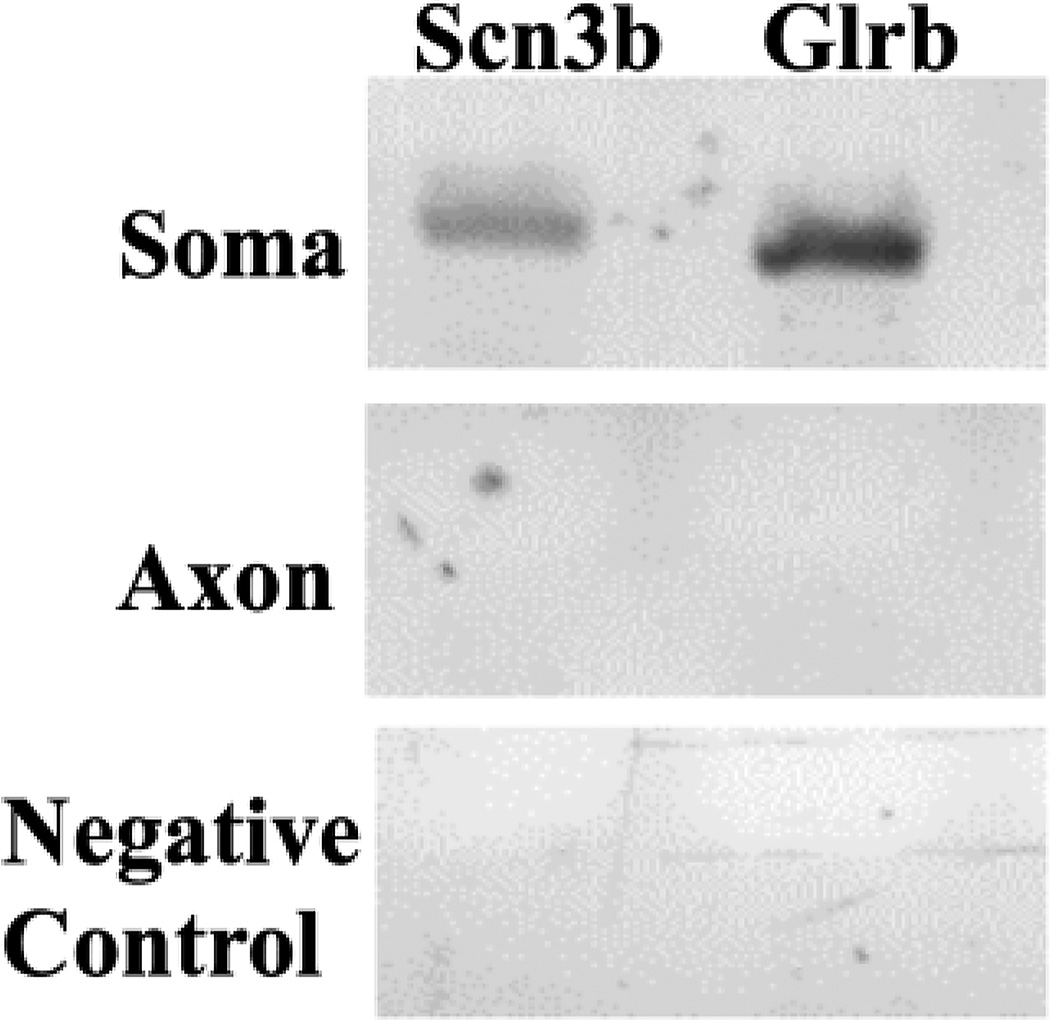

Previously, we have used cultured rat primary SCG neurons as a model system to study aspects of axonal nuclear-encoded mitochondrial mRNA functions and localization (Hillefors et al., 2007; Kaplan et al., 2009). Using a Campenot multi-compartment cell culture chamber, we purified mRNA from distal axons and their parental cell bodies 13 days in culture, and identified the composition of the nuclear-encoded mitochondrial mRNA population using a microarray analysis. Although we routinely monitor the side compartments of the Campenot cell culture chambers, where the distal axons of SCG neurons are localized, for the presence of neuronal cell soma and non-neuronal cells using light microscopy, trace cellular contamination of the axonal RNA preparation might still be detectable at the level of resolution afforded by microarray analysis or real-time PCR methodology. To address this issue, the purity of the RNA samples prepared from the distal axons was assessed by RT-PCR using gene-specific primer sets for mRNAs present in neuronal cell soma. As shown in Fig. 1, amplicons for Sodium Channel, Voltage Gated, Type III Beta Subunit (SCN3B) and Glycine Receptor, Beta (GLRB), were readily detected in RNA prepared from the neurons present in the central compartment, but were not observed in RNA obtained from distal axons. These two genes were chosen as controls as they exhibited low axonal abundance levels in the microarray analysis, being more than thirty times more enriched in the cell body. This finding was consistent with previous results, which established the purity of the axonal mRNA preparations (Natera-Naranjo et al., 2010).

Fig. 1.

RNA prepared from the distal axons of SCG neurons is free of neuronal cell body contamination. RT-PCR analysis was conducted on RNA obtained from the lateral and central compartments of the Campenot cell culture chambers using gene-specific primer sets for Scn3b and Glrb. PCR products were fractionated on 2.5% agarose gels and amplicons visualized by ethidium bromide staining. PCR reactions lacking cDNA served as negative (H2O) controls.

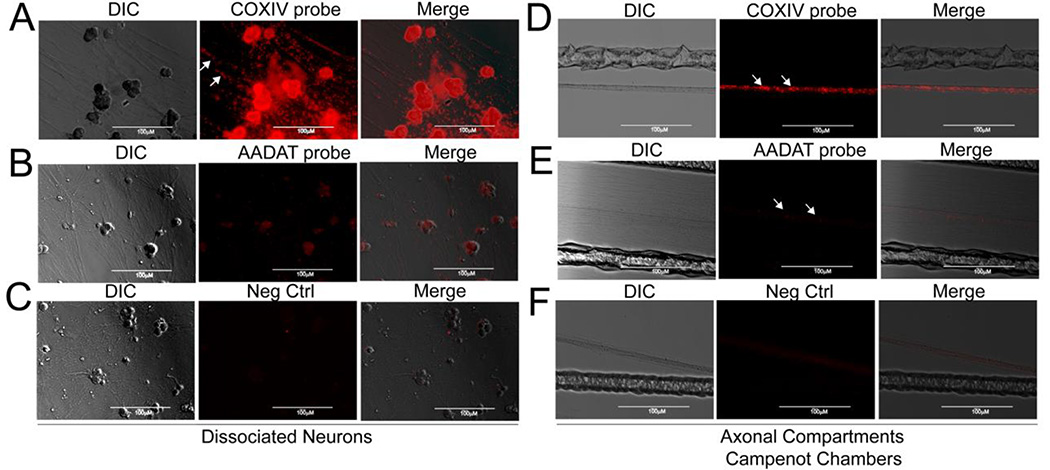

Two hundred nanograms of each RNA, isolated from the axons and cell bodies from three independent samples were fluorescently labeled and hybridized on a set of three Affymetrix rat microarray chips. All microarray chips showed successful and reproducible hybridization; therefore the data were processed for further analyses. Following microarray data annotation and normalization, a threshold value of 1.25-fold (p-value ≤ 0.05) was chosen to identify transcripts that were significantly enriched in the axon. This analysis yielded 2844 unique axon enriched mRNAs. To confirm that a threshold value of 1.25-fold enrichment represented a reasonable estimate of enrichment, we visualized the presence of COXIV mRNA (fold change (fc): 3.74) and (AADAT), an aminotransferase with a 1.26 fc, a value, which was just above the cutoff threshold. COXIV mRNA was also chosen, since previous studies indicated that disruption of the axonal trafficking and local translation of this mRNA had profound importance for the regulation of mitochondrial activity, as well as axonal growth and function (Aschrafi et al., 2008; Kar et al., 2014). DapB, an mRNA present in Bacillus subtilis, was used as a negative control as this mRNA is not present or trafficked into axons (Fig. 2). Using ISH with target specific riboprobes strong fluorescent COXIV signals in the cell bodies, proximal and distal axons were detected (Fig. 2). These fluorescent signals appeared as puncta along the entire length of the axon. In contrast, very few fluorescent puncta were detectable when target riboprobes were hybridized to AADAT mRNA, suggesting a fc threshold value of 1.25 to be a valid cutoff value. No fluorescent DapB-specific fluorescent signal was observed in axons confirming that the axonal localization of these mRNAs was neither nonspecific nor the result of passive diffusion.

Fig. 2.

The presence of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial mRNAs can be visualized in the somata and axons of primary SCG neurons. Visualization of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial mRNAs was achieved using RNAscope in situ hybridization. No signal was detected in axons hybridized with the DAPb control riboprobe. In axons hybridized with a COXIV riboprobe, mRNA appears as puncta of varying dimensions (arrows). In contrast, barely detectable fluorescent signals were observed using AADAT riboprobes.

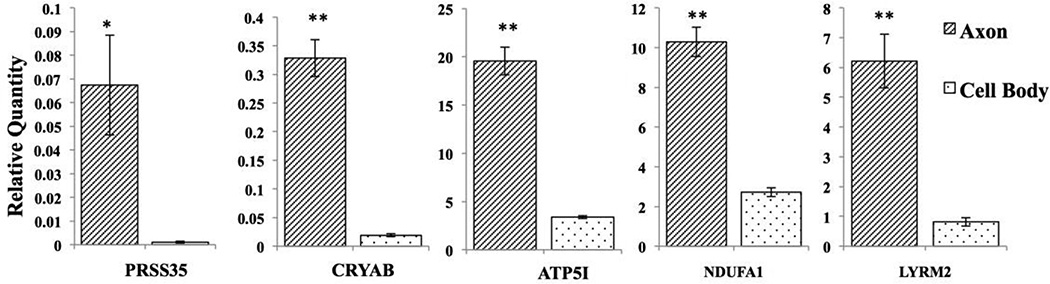

The list of 2844 enriched axonal mRNAs was annotated using MitoMiner, a database of the mitochondrial proteome (Smith and Robinson, 2016). The database identified 108 of these mRNAs as nuclear-encoded mitochondrial mRNAs (3.8% of the 1.25 fold enriched total axonal mRNAs). Additional information on the differentially expressed genes is summarized in Supplementary Table I. Since some messages were highly abundant in SCG neurons, we examined whether the mRNAs extracted from distal axons would be biased toward abundant messages. Toward this end, a Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient was computed to assess the relationship between the intensity of mRNAs in cell bodies and the intensity of these same mRNAs in axons (Fig. 3A). This inquiry revealed that the distribution of the mRNA levels in the axons and cell bodies is highly correlated (r=0.967, n=108, p < 0.001), suggesting that the hybridization of equal amounts of RNA probes from axonal and cell body samples should identify axon-enriched RNAs based on relative signal strength. Indeed, when fold-change was plotted against axonal mRNA intensity, the mRNAs most enriched in axons were not the most highly expressed messages in the neuronal cell soma (Fig. 3B). To validate the microarray analysis, the expression of the five mRNAs most enriched in the axon was assessed by qRT-PCR. This analysis confirmed an axon enrichment of Prss35, Cryab, Atp5i, Ndufa1, Lyrm2 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Subcellular distributions of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial mRNAs in the axons and cell body of SCG neurons as assessed by microarray analysis. (A) A scatter plot depicting the relative abundance of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial mRNA in the axons and cell bodies of SCG neurons. The distribution of the mRNAs levels in the axons and cell bodies is highly correlated (Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.967). (B) Comparison of axonal and cell body abundance ratios (fold-change) as a function of relative expression (intensity) for nuclear-encoded mitochondrial mRNAs suggests that Prss35, Cryab and AT5i are highly enriched in SG axons.

Fig. 4.

qRT-PCR based quantification of Prss35, Cryab, ATP5i, Ndufa1 and Lyrm2 expression levels in the cell body and axons of SCG neurons. Data are shown as mean +/– SEM; p-values are determined by Student's t-test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001.

To examine the biological processes in which axonal enriched nuclear-encoded mitochondrial mRNAs are involved, we chose a gene ontology approach. Toward this end, STRING pathway analysis was employed to investigate protein-protein interactions. This analysis yielded a number of biologically relevant molecular and biological processes (Table 1), namely oxidation-reduction, as well as cation, hydrogen ion transmembrane transport and proton transport. These processes are vital for energy production, and mRNAs associated with these processes may be enriched due to the high energy demands of axons. Interestingly, KEGG pathway mapping suggests a significant number of axonally-enriched nuclear-encoded mitochondrial mRNAs may be involved in the pathophysiology of neurodegenerative diseases, such as Huntington’s, Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson’s disease. This analysis raises the possibility that the localization, translation, and regulation of the mRNAs play important roles in both axonal health and neurological disease.

Table 1.

Gene ontology analysis of axonally abundant nuclear-encoded mitochondrial mRNAs reveals association of these genes with multiple molecular and biological processes.

| Category | GO_id | Term | # of molecules |

P values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Processes |

GO:0015078 | hydrogen ion transmembrane transporter activity | 9 | 2.21E-09 |

| GO:0004129 | cytochrome-c oxidase activity | 5 | 1.31E-05 | |

| GO:0016675 | oxidoreductase activity, acting on a heme group of donors | 5 | 1.61E-05 | |

| GO:0009055 | electron carrier activity | 6 | 3.47E-05 | |

| GO:0016491 | oxidoreductase activity | 12 | 4.12E-05 | |

| GO:0015077 | monovalent inorganic cation transmembrane transporter activity | 9 | 1.30E-04 | |

| GO:0022890 | inorganic cation transmembrane transporter activity | 9 | 1.63E-03 | |

| GO:0008137 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) activity | 4 | 2.55E-03 | |

| GO:0050136 | NADH dehydrogenase (quinone) activity | 4 | 2.55E-03 | |

| GO:0003954 | NADH dehydrogenase activity | 4 | 2.94E-03 | |

| GO:0008324 | cation transmembrane transporter activity | 9 | 5.63E-03 | |

| GO:0016655 | oxidoreductase activity, acting on NAD(P)H, quinone or similar compound as acceptor | 4 | 6.26E-03 | |

| GO:0015075 | ion transmembrane transporter activity | 9 | 4.00E-02 | |

| GO:0044710 | single-organism metabolic process | 16 | 3.87E-01 | |

| GO:0055114 | oxidation-reduction process | 13 | 3.91E-05 | |

| Biological Processes | GO:1902600 | hydrogen ion transmembrane transport | 8 | 2.68E-07 |

| GO:0015992 | proton transport | 8 | 8.92E-07 | |

| GO:0006818 | hydrogen transport | 8 | 9.71E-07 | |

| GO:0098662 | inorganic cation transmembrane transport | 8 | 1.45E-02 | |

| GO:0015672 | monovalent inorganic cation transport | 8 | 2.16E-02 | |

| GO:0006812 | cation transport | 10 | 2.56E-02 | |

| GO:0098655 | cation transmembrane transport | 8 | 2.89E-02 | |

| GO:0098660 | inorganic ion transmembrane transport | 8 | 3.47E-02 | |

| Kegg Pathway | 190 | Oxidative phosphorylation | 22 | 1.74E-32 |

| 5016 | Huntington's disease | 21 | 9.04E-28 | |

| 5010 | Alzheimer's disease | 20 | 1.79E-26 | |

| 5012 | Parkinson's disease | 19 | 6.29E-26 | |

| 4932 | Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) | 17 | 1.29E-21 | |

| 1100 | Metabolic pathways | 27 | 7.11E-18 | |

| 4260 | Cardiac muscle contraction | 6 | 9.46E-06 | |

| 3010 | Ribosome | 5 | 5.20E-03 |

4. DISCUSSION

In this communication, we identify greater than 100 nuclear-encoded mitochondrial mRNAs that are present in the distal axons of sympathetic neurons. In more than half of these cases, the relative abundance of the mRNA in question is at least 2-fold greater than the levels of corresponding mRNAs in the parental cell bodies. The extant literature has established that the asymmetric subcellular distribution and local translation of mRNA is critical for proper neuronal development and function (for review see (Holt and Schuman, 2013; Shane SS et al., 2015)). The molecular mechanisms underlying the sorting of mRNA to the axon involves the recognition of cis-acting elements present in the mRNA by RNA binding proteins that may function in both the regulation of mRNA transport and translation (for review see (Doxakis, 2014)). At present, little is known regarding the cis-acting regulatory elements that target nuclear-encoded mitochondrial mRNAs to the axon. Recently, we identified a 38-nt sequence in the 3’ UTR of COXIV mRNA that is essential for the axonal trafficking of this messenger (Aschrafi et al., 2010). Our preliminary data also suggest that this putative stem-loop structure present in the 3’ UTR of the mRNA contains sequence information that targets the mRNA to the organelles itself. In addition, we have previously demonstrated that the inhibition of the trafficking and local translation of this mRNA has marked inhibitory effects on mitochondrial activity, as well as on axonal growth and function (Aschrafi et al., 2010; Natera-Naranjo et al., 2012). This finding is consistent with the results of Corral-Debrinski and associates who reported that greater than 100 mRNAs encoding mitochondrial proteins are localized to the vicinity of mitochondria in both yeast and human HeLa cells (Marc et al., 2002; Sylvestre et al., 2003). Taken together, these findings support the idea that subcellular mRNA distribution and translational control are key mechanisms for post-transcriptional regulation of the expression of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial proteins. Previous large-scale experimental approaches to analyze the composition of mRNA in dendrites or axons relied on subcellular fractionation techniques and subsequent analysis with microarrays or PCR methodology. Unfortunately, fractionation methods are highly susceptible to contamination by fragments of glial or neuronal soma that may confound the experimental findings. The utility of compartmentalized culture systems provides a versatile approach for the isolation and quantitation of functionally relevant transcripts in distal axons that are devoid of cell body and/or non-neuronal cell contaminants. Therefore, the constituents of the mRNAs we identified in this investigation are highly likely to represent endogenous axonal mRNAs. In addition, the limited resolution inherent with microarray analysis and the stringent cut-off criteria employed in this study of the diversity of the axonal nuclear-encoded mitochondrial mRNAs provides for a conservative estimate of the diversity of the axonal nuclear-encoded mitochondrial mRNA population. Taylor et al. (2009) identified a subset of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial mRNAs enriched in CNS axons, suggesting that the axonal enrichment identified in SCG neurons may hold true for CNS axons (Taylor et al., 2009). Interestingly, many mitochondrial mRNAs are downregulated in regenerating axons following axotomy, suggesting a modification of mitochondrial function in axons following injury. Gumy et al. (2011) employed microarray analysis of transcriptome present in embryonic and adult sensory axons. This study revealed that many nuclear-encoded and mitochondrial mRNAs were enriched in both the embryonic and adult axons. These mRNAs were also found to be enriched in the axons of SCG neurons in this study. Lastly, extracellular ligands can regulate protein generation within subcellular regions by specifically altering the localized levels of particular mRNAs, few of which have been annotated as axonally localized mitochondrial mRNAs (Willis et al., 2007).

A recent genome-wide association study found the strongest genetic association with bipolar disorder residing within the Prss35/Snap91 gene complex (Goes et al., 2012). Interestingly, Prss35 is one of the most highly enriched axonal mRNAs identified in our microarray analysis. The second highest axonally enriched nuclear-encoded mitochondrial mRNA in our mitochondrial mRNA population, Cryab, is a small heat shock protein shown to be upregulated in the substantia nigra of patient’s with Parkinson’s disease (Liu et al., 2015). Additionally, Alzheimer’s disease has been associated with reduced expression of numerous nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes (Liang et al., 2008). Consistent with these observations, the most significant Kegg pathways identified by gene ontology analysis of our microarray data include that for Huntington’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease. Taken together, these findings raise the possibility that dysregulation of the axonal trafficking and/or local translation of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial mRNAs may play an important role in the pathophysiology of a variety of neurodegenerative diseases.

5. CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, our studies delineated the composition of population of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial mRNAs present in the axons of sympathetic neurons, and provide an important resource for future studies on the role played by these genes in the regulation of mitochondrial function in this important neuronal compartment.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

The axonal mitochondrial mRNA population was annotated by microarray analysis

These data were validated by qPCR methodology and in situ hybridization

Axons contain > 100 different nuclear-encoded mitochondrial mRNAs

Mitochondrial mRNAs are highly enriched in the axons of sympathetic neurons

Proteins encoded by these mRNAs function in several diverse biological processes

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Ms. Cai Chen and Weiwei Wu for invaluable technical assistance. This work was supported by the Division of Intramural Research Programs of the National Institute of Mental Health (Z01MH002768) and by the Division of Intramural Research Programs of the National Human Genome Research Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Aschrafi A, Natera-Naranjo O, Gioio AE, Kaplan BB. Regulation of axonal trafficking of cytochrome c oxidase IV mRNA. Molecular and cellular neurosciences. 2010;43:422–430. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschrafi A, Schwechter AD, Mameza MG, Natera-Naranjo O, Gioio AE, Kaplan BB. MicroRNA-338 regulates local cytochrome c oxidase IV mRNA levels and oxidative phosphorylation in the axons of sympathetic neurons. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2008;28:12581–12590. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3338-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doxakis E. RNA binding proteins: a common denominator of neuronal function and dysfunction. Neurosci Bull. 2014;30:610–626. doi: 10.1007/s12264-014-1443-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gioio AE, Eyman M, Zhang H, Lavina ZS, Giuditta A, Kaplan BB. Local synthesis of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial proteins in the presynaptic nerve terminal. J. Neurosci. Res. 2001;64:447–453. doi: 10.1002/jnr.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goes FS, Hamshere ML, Seifuddin F, Pirooznia M, Belmonte-Mahon P, Breuer R, Schulze T, Nothen M, Cichon S, Rietschel M, Holmans P, Zandi PP, Bipolar Genome S, Craddock N, Potash JB. Genome-wide association of mood-incongruent psychotic bipolar disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2012;2:e180. doi: 10.1038/tp.2012.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumy LF, Yeo GS, Tung YCL, Zivraj KH, Willis D, Coppola G, Lam BY, Twiss JL, Holt CE, Fawcett JW. Transcriptome analysis of embryonic and adult sensory axons reveals changes in mRNA repertoire localization. RNA. 2011;17(1):85–98. doi: 10.1261/rna.2386111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillefors M, Gioio AE, Mameza MG, Kaplan BB. Axon viability and mitochondrial function are dependent on local protein synthesis in sympathetic neurons 3. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 2007;27:701–716. doi: 10.1007/s10571-007-9148-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt CE, Schuman EM. The central dogma decentralized: new perspectives on RNA function and local translation in neurons. Neuron. 2013;80:648–657. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan BB, Gioio AE, Hillefors M, Aschrafi A. Axonal protein synthesis and the regulation of local mitochondrial function. Results and problems in cell differentiation. 2009;48:225–242. doi: 10.1007/400_2009_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kar AN, Sun CY, Reichard K, Gervasi NM, Pickel J, Nakazawa K, Gioio AE, Kaplan BB. Dysregulation of the axonal trafficking of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial mRNA alters neuronal mitochondrial activity and mouse behavior. Developmental neurobiology. 2014;74:333–350. doi: 10.1002/dneu.22141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang WS, Reiman EM, Valla J, Dunckley T, Beach TG, Grover A, Niedzielko TL, Schneider LE, Mastroeni D, Caselli R, Kukull W, Morris JC, Hulette CM, Schmechel D, Rogers J, Stephan DA. Alzheimer's disease is associated with reduced expression of energy metabolism genes in posterior cingulate neurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:4441–4446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709259105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin MT, Beal MF. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases 4. Nature. 2006;443:787–795. doi: 10.1038/nature05292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin MY, Sheng ZH. Regulation of mitochondrial transport in neurons. Experimental cell research. 2015;334:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Zhou Q, Tang M, Fu N, Shao W, Zhang S, Yin Y, Zeng R, Wang X, Hu G, Zhou J. Upregulation of alphaB-crystallin expression in the substantia nigra of patients with Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36:1686–1691. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marc P, Margeot A, Devaux F, Blugeon C, Corral-Debrinski M, Jacq C. Genome-wide analysis of mRNAs targeted to yeast mitochondria. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:159–164. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margeot A, Blugeon C, Sylvestre J, Vialette S, Jacq C, Corral-Debrinski M. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, ATP2 mRNA sorting to the vicinity of mitochondria is essential for respiratory function 13. EMBO J. 2002;21:6893–6904. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natera-Naranjo O, Aschrafi A, Gioio AE, Kaplan BB. Identification and quantitative analyses of microRNAs located in the distal axons of sympathetic neurons. Rna. 2010;16:1516–1529. doi: 10.1261/rna.1833310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natera-Naranjo O, Kar AN, Aschrafi A, Gervasi NM, Macgibeny MA, Gioio AE, Kaplan BB. Local translation of ATP synthase subunit 9 mRNA alters ATP levels and the production of ROS in the axon. Molecular and cellular neurosciences. 2012;49:263–270. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard M. Mitochondrial synapses: intracellular communication and signal integration. Trends Neurosci. 2015;38:468–474. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruijter JM, Pfaffl MW, Zhao S, Spiess AN, Boggy G, Blom J, Rutledge RG, Sisti D, Lievens A, De Preter K, Derveaux S, Hellemans J, Vandesompele J. Evaluation of qPCR curve analysis methods for reliable biomarker discovery: Bias, resolution, precision, and implications. Methods. 2013;59:32–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott SS, Gervasi NM, Kaplan BB. Subcellular Compartmentalization of Neuronal RNAs: An Overview. Trends in Cell & Molecular Biology. 2015;10:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng ZH, Cai Q. Mitochondrial transport in neurons: impact on synaptic homeostasis and neurodegeneration. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:77–93. doi: 10.1038/nrn3156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AC, Robinson AJ. MitoMiner v3.1, an update on the mitochondrial proteomics database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D1258–D1261. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylvestre J, Margeot A, Jacq C, Dujardin G, Corral-Debrinski M. The role of the 3' untranslated region in mRNA sorting to the vicinity of mitochondria is conserved from yeast to human cells. Molecular biology of the cell. 2003;14:3848–3856. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-02-0074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AM, Berchtold NC, Perreau VM, Tu CH, Li Jeon N, Cotman CW. Axonal mRNA in uninjured and regenerating cortical mammalian axons. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29:4697–4707. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6130-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis DE, van Niekerk EA, Sasaki Y, Mesngon M, Merianda TT, Williams GG, Kendall M, Smith DS, Bassell GJ, Twiss JL. Extracellular stimuli specifically regulate localized levels of individual neuronal mRNAs. The Journal of cell biology. 2007;178(6):965–980. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200703209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.