Abstract

Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) was established in 2007 for public sector and nonprofit enterprise employees to pursue educational loan forgiveness. Under PSLF, graduates are offered complete loan forgiveness after 120 qualifying monthly payments while employed at public or nonprofit institutions, including payments made during residency for physicians. In response to concerns that PSLF will heavily subsidize lawyers, doctors, and other professionals, the President’s 2017 budget proposes limiting maximum forgiveness. Using data from the Association of American Medical Colleges Graduation Questionnaire (n = 55,905; response rate of 80 %), we found that intended participation in PSLF among medical school graduates grew 20 % per year since 2010. Future primary care physicians intend to use PSLF more than programs that were historically designed to promote primary care, such as the National Health Service Corp (NHSC). The federal government’s projected cost of PSLF will reach over $316 million for 2014 graduates (net present value), approximately seven times the annual contributions from the NHSC. The proposed cap will reduce the total anticipated forgiveness by nearly two-thirds and substantially reduce subsidies for physicians. More targeted measures of loan forgiveness could be considered, such as making forgiveness contingent on pursuing specialties that society needs or practicing in shortage areas.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3767-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: medical students, medical education, medical education debt, student loan repayment, loan forgiveness, primary care workforce, physician manpower, physician shortage, health finance, health economics

Becoming a doctor in the US is increasingly expensive. Medical students finance their education with debt to a greater extent each year, with the average graduate carrying educational loans in excess of $175,000—a figure that continues to rise annually. In the class of 2013, 52 % of medical school graduates reported nominal debt levels greater than $150,000, compared to only 11 % in 2000 (see online Supplementary Figure 1).1 Physicians will incur the same cost for their medical education whether they enter primary care or specialist fields, but once they emerge from their training they will have more difficulty managing their debt in primary care fields due to lower income.2 For example, when measuring debt as a ratio to income, primary care physicians have approximately double the debt burden as those entering surgical fields.3

In a 2014 survey by Merritt Hawkins, 38 % of final year medicine residents reported that education loan repayment/forgiveness was a “major concern,” up from 12 % in 2006.4 Increased financial concern has been associated with poor health,5 and studies have found higher rates of burnout among resident physicians with greater educational debt.6 Federally sponsored loan repayment and loan forgiveness programs may provide relief to physicians as well as other professionals. The most touted repayment programs are income driven plans including Pay As You Earn, which allows graduates to pay a minimum of 10 % of their monthly discretionary income to loan repayment (see online Supplementary Table 1).7 All professional school graduates using Pay As You Earn can achieve loan forgiveness after 240 payments (or 20 years of payments); however, those employed at a public or non-profit entity can attain early forgiveness using the Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) program.8

The PSLF program was a recent policy response to growing education debt, and while not targeted specifically at medical education, has become increasingly popular among medical graduates. PSLF was established in the College Cost Reduction and Access Act of 2007 as a means for public sector and nonprofit enterprise employees to pursue educational loan forgiveness.9 Under PSLF, graduates are offered complete loan forgiveness after 120 qualifying monthly payments while employed at public or nonprofit institutions, including payments made during residency for most physicians. This program is widely available to physicians since approximately 75 % of U.S. hospitals are non-profit or public entities,10 and approximately 95 % of medical school loans from 2010 to 2013 are eligible for forgiveness under PSLF (see online Supplementary Figure 2). The first anticipated year of forgiveness from PSLF is in 2017, and a greater percentage of graduates with eligible loans are anticipated to reach 10 years of public service each year through 2020.

Under PSLF, a young physician with $175,000 in educational debt who completed a three-year residency (e.g. internal medicine, pediatrics) and maintains employment at a nonprofit medical center with a $125,000 starting salary will be debt-free ten years after graduating medical school, and repay $100,000 loans with $234,000 in forgiveness.11 By comparison, if the same physician decided to forego PSLF, they would need to repay $2,000 per month (including payments made during residency), with payments at the end of ten years totaling $250,000. Therefore, in direct comparison to the standard repayment option, the PSLF program represents the potential for $150,000 in savings for the average primary care physician.

In response to concerns that PSLF will heavily subsidize lawyers, doctors, and other professionals, the President’s 2017 budget proposes limiting maximum loan forgiveness to $57,500.12 Congress and the administration typically make changes to federal student aid programs applicable only to new borrowers, and therefore, current and former borrowers are unlikely to be impacted.12 The proposed cap to PSLF is driven by fears that tuition increases will be paid by taxpayers rather than borrowers, leaving academic institutions with little incentive to rein in the costs of graduate education.13 Although the PSLF cap seeks to solve a substantial problem, the nation’s future physician workforce may be adversely affected.14

To better understand trends in loan forgiveness participation by physician specialty, we analyzed data from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Graduation Questionnaire. The questionnaire is an annual cross-sectional census of over 70,000 graduating medical students from 2010 to 2014, with overall survey response rates ranging from 79 % to 83 % per year. Planned loan forgiveness was stratified by primary care eligible specialties, other medical specialties, or surgical specialties (see detailed methodology in the online Supplementary Appendix).

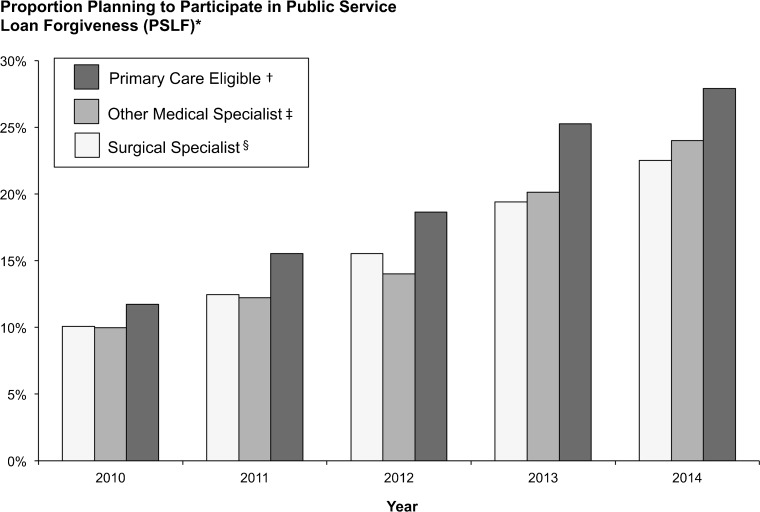

We found nearly 40 % of U.S medical school graduates intended to pursue loan forgiveness in 2014. Among those pursuing loan forgiveness, 44 % targeted PSLF in 2010 and 62 % in 2014 (approximately one-quarter of all medical graduates), making PSLF the most preferred loan forgiveness program for US medical graduates based on the survey. For graduates choosing primary care eligible specialties, 11.7 % intended to use PSLF in 2010 compared to 25.3 % in 2014. Graduates pursuing medical (22.5 %, p < 0.01) and surgical specialties (24.0 %; p < 0.01) plan to use PSLF to a slightly lesser extent in 2014 compared to primary care eligible specialties, although increases parallel those of primary care (see Fig. 1 and online Supplementary Table 2). The similar intent to utilize PSLF across primary care eligible, medical and surgical specialties is likely reflective of the ability to discharge a larger proportion of the public service obligation during residency and fellowship for specialties with longer training programs (e.g., neurosurgeons), which may make PSLF more appealing to these specialties.

Figure 1.

Planned Public Service Loan Forgiveness Participation by Specialty, 2010–2014. * Data are from the Association of American Medical Colleges Graduation Questionnaire, 2010–2014. Response Rates: 2010 = 83 %, 2011 = 78 %, 2012 = 79 %, 2013 = 82 %, and 2014 = 82 %. † Primary care eligible specialties include family medicine, pediatrics, internal medicine, medicine/pediatrics, and preventive medicine. The intended use among primary care eligible specialties is greater when compared to other medical specialties (p < 0.01) and surgical specialties (p < 0.01) within each year of the data set. ‡ Other medical specialties include allergy/immunology, dermatology, emergency medicine, medical genetics, neurology, pathology, physical medicine and rehabilitation, psychiatry, radiology, radiation oncology, hospice and palliative medicine, and a 75 % random sample of internal medicine and internal medicine/pediatrics. § Surgical specialties include anesthesiology, colon and rectal surgery, general surgery, neurological surgery, obstetrics and gynecology, ophthalmology, orthopedics, otolaryngology, plastic surgery, thoracic surgery, and urology.

Based on these figures and the estimated forgiveness for each specialty, the federal government’s projected cost of PSLF could reach an estimated $316 million for 2014 medical graduates (net present value calculation; see detailed methodology in the online Supplementary Appendix), approximately seven times the annual contributions from the National Health Service Corp for physician loan forgiveness.

PSLF represents a significant relief to the population of medical graduates pursuing primary care, as well as those pursuing other specialties. While PSLF was not originally aimed at physicians, intended participation among medical school graduates has grown 21.2 % per year since 2010. Future primary care physicians intend to use PSLF more than programs that were historically designed to promote primary care, such as state repayment programs and the National Health Service Corp.15,16

The proposed cap in the 2016 federal budget would serve to amplify the debt repayment obligation for physicians that would otherwise use the program. For those considering primary care, the loss of prospective debt relief imposed by the cap as a percentage of their lifetime income will be substantial. The equal participation across studied specialties also implies that the program requires too little in exchange for its financial transfer, as the opportunity cost of making a commitment to under-served populations is higher for non-primary care specialties.

More targeted measures of loan forgiveness could be considered, such as making forgiveness contingent on pursuing specialties that meet under-served societal needs (e.g., primary care, geriatrics) or practicing in a health professional shortage area. Alternative programs may bolster primary care payments similar to the recently departed Medicaid “fee bump”, which pays primary care physicians more to see Medicaid patients, thereby increasing access for the underserved.17

Another program targeted at expanding the primary care workforce, the National Health Service Corps (NHSC), offers up to $170,000 of loan repayment in exchange for five years of service in defined areas of need.18 NHSC is intended to induce greater primary care supply in areas of need, but has only spent approximately $44 million annually on physician loan forgiveness since 2010.19 The cap to PSLF yields the possibility for an expansion or funding new programs that could offer loan forgiveness. Rather than PSLF's far broader eligibility criteria of working for a non-profit, new programs may consider loan forgiveness in exchange for service in high outcome and/or underserved medical practices, including Patient Centered Medical Homes, public hospitals and Veterans Affairs facilities, Federally Qualified Health Centers, Indian Health Service, Medicare’s Health Professional Shortage Areas Physician Bonus Program, or other organizations tasked with providing access to the underserved or high quality care in low cost environments. Nonprofit hospitals encompass the vast majority of US hospitals, which already receive federal tax benefits in excess of $20 billion annually.20 Nonprofit hospital inclusion within PSLF furthers the public’s support of these institutions. New mechanisms may provide a more equitable distribution of physician loan forgiveness funds, and should be accompanied by an independent body empowered to evaluate program success and course correct as evidence becomes available.

PSLF may also result in geographical inequities in the distribution of physician services. The variation in the proportion of hospital which are nonprofit entities is high, ranging from 90 % of hospitals in states like Maryland, Wisconsin, and Connecticut, to 40 % in states such as Texas, Florida and Louisiana.21 Rather than offering federal loan forgiveness to physicians based on the ownership status of their employer, new policies could tie loan forgiveness amounts to the proportion of care provided to underserved populations or service within federally designated Health Professional Shortage Areas.

Our study has several limitations. We focus on the physician workforce since these are the healthcare professionals with the greatest cost of education, which is sustained by physician payments that represent approximately 20 % of US healthcare costs.2 However, other professionals (e.g., veterinarians, lawyers, dentists), who share similar debt to income burdens as those in primary care fields may also be adversely affected by the proposed cap to PSLF. Additionally, we report intended use of PSLF from a survey of medical graduates, and intended use is likely to differ from actual use. Nonetheless, these data from a nationwide survey represent the only available estimates to date for PSLF participation by medical graduates, and information regarding future use of the program is needed given that policy changes are proposed. Alternative measures of program participation will not be available for several years to address this pressing policy concern. Consistent with our results, rates of actual application to the NHSC were similar to reported intended use within the AAMC survey (see online Supplementary Appendix). We use average loan forgiveness amounts to calculate our estimates on cost of PSLF to the federal government, and actual forgiveness may vary depending on individual circumstances. To avoid overestimating costs, we use the number of graduates reporting intended use within our sample (which represents a smaller fraction of all medical graduates), and therefore actual costs of PSLF for doctors may be greater. Despite this limitation, our figures are on par with those cited elsewhere, with predictions of total PSLF program forgiveness reaching the billions of dollars by 2020.22 Finally, only 25 % of internal medicine residents enter primary care,23 and the survey cannot discern which. We used a sensitivity analysis designating internal medicine as primary care versus other medical specialty, which demonstrated similar conclusions (see online Supplementary Figure 3).

The PSLF program is designed to encourage work for the public sector and nonprofit enterprises, while consuming public funds to alleviate the large debt burdens of its participants. Despite its recent origin, young physicians from all specialties intend to use PSLF. Doctors in the program may discharge a significant portion of their public service obligation through time spent in residency, which when combined with income driven plans may yield large forgiveness amounts after 10 years of service. After significant growth in PSLF over the past 5 years, nearly one-third of medical graduates with loan obligations are now reporting their intent to receive PSLF forgiveness funds, and enrollment in the program continues to grow. Our study estimates that PSLF could become the greatest source of loan forgiveness funds for those pursuing primary care; however, a high percentage of forgiveness for physicians will also be directed toward medical specialists and surgeons. If enacted, the proposed cap on individual forgiveness under PSLF may impact many new doctors and potentially limit loan forgiveness support for physicians where it is most needed. If implemented, the funds liberated by the cap could be used to fund loan forgiveness programs that incentivize graduates to pursue specialties that society needs or encourage practice within health professional shortage areas.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(PDF 309 kb)

Acknowledgements

Author Contributions

Dr. George had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. Friedman and Grischkan contributed equally.

Study Concept and Design

Friedman, Grischkan, George.

Acquisition of Data

Grischkan, George.

Analysis and Interpretation of Data

Friedman, Grischkan, Dorsey, George.

Critical Revision of the Manuscript for Important Intellectual Content

Friedman, Grischkan, Dorsey, George.

Statistical and Economic Analysis

Friedman, George.

Study Supervision

George.

Additional Contributions

The authors wish to thank Dr. David Asch (University of Pennsylvania) for his comments and thoughtful review of the article. The authors wish to thank Dr. Sarah Ackroyd (University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry) for guidance and assistance in developing a focus for this article. The authors wish to thank Dr. David Matthews (Association for American Medical Colleges) for assistance with access to data.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Study Funding

This study was not funded.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

Dr. Dorsey reports consultancy for Amgen, Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, Clintrex, Lundbeck, Medtronic, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and Transparency Life Sciences; a filed patent related to telemedicine and neurology; and stock/stock options in Grand Rounds (a second opinion service). No other disclosures were reported.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3767-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

REFERENCES

- 1.AAMC Data Book: Medical Schools and Teaching Hospitals by the Numbers. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges, 1994-2014.

- 2.Asch DA, Nicholson S, Vujicic M. Are we in a medical education bubble market? N Engl J Med. 2013;369(21):1973–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1310778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moses H, III, Matheson DHM, Dorsey ER, George BP, Sadoff D, Yoshimura S. The anatomy of Health Care in the United States. JAMA. 2013;310(18):1947–1964. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Merritt Hawkins 2015 Survey Final-Year Medical Residents 2015. Available at: http://www.merritthawkins.com/uploadedFiles/MerrittHawkings/Surveys/2014_MerrittHawkins_FYMR_Survey.pdf. Accessed May 25, 2016.

- 5.Turunen E, Hiilamo H. Health effects of indebtedness: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:489. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.West CP, Shanafelt TD, Kolars JC. Quality of life, burnout, educational debt, and medical knowledge among internal medicine residents. JAMA. 2011;306(9):952–960. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.United States Department of Education, Office of Federal Student Aid. Income-Driven Plans 2015. Available at: https://studentaid.ed.gov/sa/repay-loans/understand/plans/income-driven. Accessed May 25, 2016.

- 8.Mitchell J. Grad-School Loan Binge Fans Debt Worries. The Wall Street Journal. August 18, 2015. Available at: http://www.wsj.com/articles/loan-binge-by-graduate-students-fans-debt-worries-1439951900. Accessed May 25, 2016.

- 9.Government Publishing Office. College Cost Reduction and Access Act of 2007. Public Law 110-84. Available at: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-110publ84/pdf/PLAW-110publ84.pdf. Accessed May 25, 2016.

- 10.American Hospital Association Fast Facts on US Hospitals 2015. Available at: http://www.aha.org/research/rc/stat-studies/fast-facts.shtml. Accessed May 25, 2016.

- 11.Association of American Medical Colleges. Medical Student Education: Debt, Costs, and Loan Repayment Fact Card. 2013. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/download/409092/data/13debtfactcard.pdf. Accessed May 25, 2016.

- 12.President Obama’s FY 2017 Budget: Impact on Medical School Financial Aid. Fast Facts from AAMC Government Relations. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/download/373230/data/ffstudentaid.pdf. Accessed May 25, 2016.

- 13.New America Foundation. Zero Marginal Cost: Measuring Subsidies for Graduate Education in the Public Service Loan Forgiveness Program. September 2014. Available at: https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/policy-papers/zero-marginal-cost/. Accessed May 25, 2016.

- 14.President’s Proposed Budget Includes Dangerous Cuts to Patient Care Payments. Association of American Medical Colleges. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/newsroom/newsreleases/454316/20160209_presidentsbudgetrelease.html. Accessed May 25, 2016.

- 15.Pathman DE, Goldberg L, Konrad TR, Morgan JC. State repayment programs for health care education loans. JAMA. 2013;310(18):1982–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saxton JF, Johns MM. Grow the US National Health Service Corps. JAMA. 2009;301(18):1925–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Polsky D, Richards M, Basseyn S, Wissoker D, Kenney GM, Zuckerman S, et al. Appointment availability after increases in medicaid payments for primary care. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(6):537–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1413299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Health Service Corps. At-A-Glance. Available at: http://nhsc.hrsa.gov/downloads/nhscglance.pdf. Accessed May 25, 2016.

- 19.Rowe S, Wisniewski S. AAMC Data Book: Medical Schools and Teaching Hospitals by the numbers, 2013. Washington, D.C.: American Association of Medical Colleges; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenbaum S, Kindig DA, Bao J, Byrnes MK, O’Laughlin C. The value of the nonprofit hospital tax exemption was $24.6 billion in 2011. Health Aff. 2015;34(7):1225–1233. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation Hospitals by Ownership Type Available at: http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/hospitals-by-ownership/. Accessed May 25, 2016.

- 22.Mitchell J. U.S. Student-Loan Forgiveness Program Proves Costly. The Wall Street Journal. Nov 20, 2015. Available at: http://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-student-loan-program-proves-costly-1448042862. Accessed May 25, 2016.

- 23.American College of Physicians. Internal Medicine residency match results virtually unchanged from last year. Available at: http://www.acponline.org/newsroom/im_residency_match_results14.htm. Accessed May 25, 2015.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 309 kb)