Abstract

Previous studies showed that the upregulation of the P2X7 receptor in cervical sympathetic ganglia was involved in myocardial ischemic (MI) injury. The dysregulated expression of long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) participates in the onset and progression of many pathological conditions. The aim of this study was to investigate the effects of a small interfering RNA (siRNA) against the NONRATT021972 lncRNA on the abnormal changes of cardiac function mediated by the up-regulation of the P2X7 receptor in the superior cervical ganglia (SCG) after myocardial ischemia. When the MI rats were treated with NONRATT021972 siRNA, their increased systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), heart rate (HR), low-frequency (LF) power, and LF/HF ratio were reduced to normal levels. However, the decreased high-frequency (HF) power was increased. GAP43 and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) are markers of nerve sprouting and sympathetic nerve fibers, respectively. We found that the TH/GAP43 value was significantly increased in the MI group. However, it was reduced after the MI rats were treated with NONRATT021972 siRNA. The serum norepinephrine (NE) and epinephrine (EPI) concentrations were decreased in the MI rats that were treated with NONRATT021972 siRNA. Meanwhile, the increased P2X7 mRNA and protein levels and the increased p-ERK1/2 expression in the SCG were also reduced. NONRATT021972 siRNA treatment inhibited the P2X7 agonist BzATP-activated currents in HEK293 cells transfected with pEGFP-P2X7. Our findings suggest that NONRATT021972 siRNA could decrease the upregulation of the P2X7 receptor and improve the abnormal changes in cardiac function after myocardial ischemia.

Keywords: P2X7 receptor, Long noncoding RNA, Superior cervical ganglia, Myocardial ischemia

Introduction

The eukaryotic transcriptome is composed of both a large set of protein-coding RNAs and large numbers of noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) [1]. Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are classified as transcripts >200 nucleotides in length [2]. LncRNAs are transcribed from either strand and are classified as sense, antisense, bidirectional, intergenic, or intronic with respect to the nearby protein-coding genes [3, 4]. LncRNAs can directly interact with both DNA and RNA through base pairing or bind to protein partners through specific structural motifs [5, 6]. As transcriptional regulators, some lncRNAs can act locally to regulate the expression of nearby genes (near their sites of synthesis) or distally to regulate gene expression across multiple chromosomes [4, 6]. Genetic knockout of some lncRNAs in mice resulted in perinatal or postnatal lethality or developmental defects [7, 8]. LncRNAs are also implicated in nervous system diseases [9]. Inhibiting lncRNA function in vivo may represent an effective strategy to modulate lncRNAs for therapeutic treatments [7, 8].

Adenine triphosphate (ATP) can be released from the sympathetic ganglia and takes part in signal transduction by acting on P2X receptors [10–12]. P2X receptors participate in cardiovascular regulation [11, 13–15] and are involved in diseases of the nervous system [10, 11, 16, 17]. Previous studies in our laboratory showed that the upregulation of the P2X3, P2X2/3, and P2X7 receptors in the stellate ganglia (SG) and superior cervical ganglia (SCG) after MI injury resulted in increased blood pressure and HR by strengthening the activity of the sympathetic postganglionic neurons [15, 18–28]. Our works also showed that P2X3, P2X2/3, or P2X7 antagonists decreased the elevated SBP and HR and alleviated the arrhythmia induced by myocardial ischemia [15, 18–29]. NONRATT021972 is a lncRNA [30] [http://www.noncode.org]. Our previous work showed that the NONRATT021972 was involved in the MI injury [31]. In this study, we further explore the effects of a small interfering RNA (siRNA) against the NONRATT021972 lncRNA on the upregulation of the P2X7 receptor in the SCG and the abnormal cardiac function in presence the abnormal distribution of sympathetic nerve fibers in the SCG after the MI.

Materials and methods

Animals and myocardial ischemia models

Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats (180–220 g) were used. The animals’ use was reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Medical College of Nanchang University. The experiments were performed in accordance with the Guidelines set forth by the US NIH regarding the care and use of animals for experimental procedures. The rats were randomly divided into seven groups (with eight rats in each group): control group (con); sham group; myocardial ischemic group (MI); myocardial ischemic rats treated with the P2X7 receptor antagonist brilliant blue G (BBG) group (MI + BBG); myocardial ischemic rats treated with the NONRATT021972 siRNA group (MI + NONRATT021972 si); myocardial ischemic rats treated with the P2X7 siRNA group (MI + P2X7 si) and myocardial ischemic rats treated with the scrambled siRNA group (MI + SC si). The myocardial ischemia model was established by occlusion of the left coronary artery (LCA) [32]. Briefly, the rats were anesthetized with 10 % chloral hydrate (0.3 ml/100 g body weight) via intraperitoneal injection. After mechanical ventilation and thoracotomy, a 5-0 suture on a small, curved needle passed through the myocardium beneath the LCA. The suture was then pulled tightly against the vinyl tube to ligate the blood vessel. However, in the sham operation, the LCA was not ligated and only the cardiac pericardium was opened.

After surgery, the changes in the animals’ electrocardiograms (ECGs) were continuously monitored. The relative voltage of the negative peak of the S wave against the QQ line was defined as the ST segment. Myocardial ischemia was confirmed by the presence of an abnormal Q wave and ST segment displacement in a lead II ECG. Beginning at 24 h after surgery, the rats in the MI + BBG group were intraperitoneally administered BBG dissolved in saline at a dose of 30 mg/kg body weight daily for 30 days [33]. Meanwhile, the rats in the MI + NONRATT021972 si, MI + P2X7 si, and MI + SC si groups were administered the NONRATT021972, P2X7, and scrambled siRNAs, respectively, by sublingual injection.

The small interfering RNA target sequences were as follows: P2X7 siRNA: GTGCAGTGAATGAGTACTA; NONRATT021972: GAATGTTGGTCATATCAAA.

DBP, SBP, HR, and heart rate variability (HRV) measurements

Blood pressure and HR measurements

The DBP, SBP, and HR were measured by indirect tail-cuff plethysmography with a noninvasive blood pressure monitor as previously described [22]. Systolic pulsation was detected by an electrosphygmograph coupler (ZH-HX-Z, MD 3000, Anhui), transduced by a pneumatic transducer and recorded on a physiograph. The rats were habituated to the entire test procedure during the 2 weeks before the experiments started, and all measurements were made by the same person in a quiet room. The SBP was averaged from four to eight measurements for each rat.

HRV measurements

The rats were anesthetized with 10 % chloral hydrate (0.3 ml/100 g). Then, the rats were fixed on the operating table in the supine position. The ECG electrodes were subcutaneously fixed to both the upper and right lower limbs using the Medlab biological ECG signal acquisition and processing system to record a standard II lead electrocardiogram. The obtained ECG signals were analyzed by the HRV analysis software using a short duration 5 min frequency domain analysis method and a 5 min electrocardiogram for the HRV analysis [34, 35]. The HRV frequency analysis consisted of the LF (ms, 0.04–0.15 Hz) and HF (ms, 0.15–0.40 Hz) components [36]. The ratio of the LF to HF power represents the balance between the tension in the sympathetic nerve and vagus nerve [36].

In situ hybridization (ISH)

mRNA expression was assessed by ISH [19]. The rats were anesthetized and decapitated. The SCG were immediately dissected and fixed in 4 % paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 2 h at room temperature and then transferred to 15 % sucrose in 4 % PFA overnight. The tissues were sectioned at 15 μm. The samples were stored in 4 % PFA in a cryostat at 4 °C. Diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC) water was used for all solutions and equipment used for ISH. An in situ hybridization kit for NONRATT021972 was used. The sections were treated with 0.05 % H2O2, followed by digestion with pepsin at 37 °C for 1–2 min, and then terminated and washed with 0.5 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 15 min. Next, the sections were incubated in prehybridization buffer for 2 h at 37 °C and in hybridization buffer overnight at 37 °C. The sections were washed thoroughly with a gradient of SSC (2× SSC: 17.6 g sodium chloride and 8.8 g sodium citrate in 1000 mL distilled water), 2× SSC for 10 min, 0.5× SSC for 15 min, and 0.2× SSC for 15 min, to remove the background signals. Next, the sections were treated with a biotinylated digoxin antibody at 37 °C for 2 h. After the sections were thoroughly washed with PBS, the samples were incubated with streptavidin-biotin complex for 30 min and biotinylated peroxidase for 30 min at 37 °C. The color reaction was developed using the DAB substrate, and the sections were dehydrated and then mounted with neutral gum.

Immunohistochemistry

The rats were killed 30 days after surgery. Their hearts, SG, and SCG tissues were immediately dissected, washed in PBS and then fixed with 4 % PFA for 24 h. The ganglia were dehydrated with 30 % sucrose overnight at 4 °C. The ganglia were cut into 12-μm-thick sections on a cryostat. After washing three times with PBS, the preparations were incubated in 3 % H2O2 for 7 min to block the endogenous peroxidase activity and then washed three times with PBS. The sections were then incubated with 5 % BSA for 2 h at 37 °C. After three rinses in PBS, the sections were incubated with a rabbit anti-P2X7 antibody (1:100, Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel), rabbit anti-GAP43 antibody (1:200, Millipore International Inc., USA), or mouse anti-TH antibody (1:150, Abcam International Inc.) diluted in PBS overnight at 4 °C. After three rinses in PBS, the sections were then incubated with a biotinylated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Beijing Zhongshan Biotechnology Co.) for 1 h at 37 °C. The preparations were washed in PBS and streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (Beijing Zhongshan Biotechnology Co.) was added for 30 min at room temperature. After the diaminobenzidine chromogen was developed for 2 min, the slides were washed with distilled water and cover-slipped. The sections were mounted and examined under a microscope (Olympus TH4-200, Japan). The changes in the integrated optical density (IOD) of the ganglionic neurons were analyzed with Image Pro-Plus software.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) measurements

Before decapitation, the blood samples were collected via orbit vein. After incubation at room temperature for 30 min, the samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min, and then, the sera were collected and stored at −20 °C. The concentrations of NE and EPI were quantified with an ELISA kit [19] according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Senxiong Co., Shanghai, China). The reactions were read with a microplate reader (Rayto, RT-6000, USA) at 450 nm.

Quantitative real-time PCR

The total RNA was isolated from the SCG using the TRIzol Total RNA Reagent (Beijing Tiangen Biotech, Co.). The reverse transcription reaction was completed using a RevertAid™ First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Fermentas, Glen Bernie, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The primers were designed with Primer Express 3.0 software (Applied Biosystems), and the sequences were as follows: P2X7, sense 5′-CTTCGGCGTGCGTTTTG-3′, anti-sense 5′-AGGACAGGGTGGATCCAATG-3′; NONRATT021972, sense 5′-TCAGATCGGTGCATCAAAGC-3′, anti-sense 5′-GGACTGGGCAGCAGGAATGA-3′; and β-actin, sense 5′-GCTCTTTTCCAGCCTTCCTT-3′, anti-sense 5′-CTTCTGCATCCTGTCAG CAA-3′. Quantitative PCR was performed using the SYBR® Green MasterMix in an ABI PRISM® 7500 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, CA). The thermal cycling parameters were 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of amplifications at 95 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 30 s [37]. The amplification specificity was determined using a melting curve, and the results were processed by the software provided with the ABI7500 PCR instrument. The quantification of gene expression was performed using the ΔΔCT calculation with CT as the threshold cycle. The relative levels of target genes, normalized to the sample with the lowest CT, were given as 2−ΔΔCT.

Western blotting

The protein expression levels were determined by Western blotting [19, 25, 26]. The rats were killed 30 days after surgery. The ganglia were dissected and flushed with ice-cold PBS. The isolated tissues were homogenized by mechanical disruption in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1 % dodecyl sodium sulfate, 1 % Nonidet P-40, 0.5 % sodium deoxycholate, 100 μg/mL phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 1 μg/mL aprotinin). The homogenate was incubated on ice for 40 min, followed by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was collected, and the protein concentrations were quantified by the Lowry method. After diluting with loading buffer (100 mM Tris-Cl, 200 mM dithiothreitol, 4 % sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.2 % bromophenol blue, and 20 % glycerol) and heating at 95 °C for 5 min, equal amounts of the total protein (20 μg) were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis using a Bio-Rad electrophoresis and blotting system. The separated proteins were transferred onto PVDF membranes using the same system. The membranes were blocked with 5 % nonfat dry milk in a solution of 25 mM Tris-buffered saline, pH 7.2, plus 0.1 % Tween 20 (TBST) for 2 h at room temperature, followed by incubation with rabbit anti-P2X7 (1:1000, Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel), mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin (1:800, Advanced Immunochemicals, Long Beach, CA), rabbit anti-p-ERK1/2 (1:1000) and rabbit anti-ERK1/2 antibodies (1:1000) overnight at 4 °C. After washing in TBST, the membranes were incubated with an HRP-conjugated IgG (1:500, Beijing Zhongshan Biotechnology Co) for 1 h at room temperature. After washing in TBST, the membranes were incubated with an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) kit (Shanghai Pufei Biotechnology Co.) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The chemiluminescent signals were collected on autoradiography films. The band intensity was quantified using Image Pro-Plus software. The relative band intensity of the target proteins was normalized to the intensity of the respective β-actin internal control.

HEK 293 cell culture and transfection

HEK 293 cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum and 1 % penicillin and streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5 % CO2. The cells were transiently transfected with the human pcDNA3.0-EGFP-P2X7 plasmid and NONRATT021972 siRNA using the Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. When the HEK293 cells were 70–80 % confluent, the cell culture media was replaced with OptiMEM 2 h prior to transfection. The transfection media were prepared as follows: (a) 4 μg of DNA or siRNA diluted into a 250 μl final volume of OptiMEM; (b) 10 μl of Lipofectamine2000 diluted into a 250 μl final volume of OptiMEM; and (c) the Lipofectamine-containing solution was mixed with the plasmid-containing solution and incubated at RT for 20 min. Subsequently, 500 μl of the cDNA/Lipofectamine complex solution was added to each well. The cells were incubated for 6 h at 37 °C in 5 % CO2. After incubation, the cells were washed in MEM containing 10 % FBS and incubated for 24–48 h. The GFP fluorescence was assessed as a reporter for the transfection efficiency. Whole-cell patch clamp recordings were performed 1–2 days after transfection.

Electrophysiological recordings

Electrophysiological recording was performed using a patch/whole cell clamp amplifier (Axopatch 200B) [18]. The micropipette was filled with an internal solution (in mM) containing KCl (140), MgCl2 (2), HEPES (10), EGTA (11), and ATP (5); the solution’s osmolarity was adjusted to 340 mOsmol/kg with sucrose and its pH was adjusted to 7.4 with KOH. The external solution (in mM) contained NaCl (150), KCl (5), CaCl2 (2.5), MgCl2 (1), HEPES (10), and D-glucose (10); the solution’s osmolarity was adjusted to 340 mOsm with sucrose and its pH was adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. The resistance of the recording electrodes was in the range of 1 to 4 MΩ, with 3 MΩ being optimal. A small patch of membrane underneath the tip of the pipette was aspirated to form a seal (1–10 GΩ), and then, more negative pressure was applied to rupture it to establish a whole-cell mode. The holding potential (HP) was set at −60 mV. The drugs were dissolved in the external solution and delivered by gravity flow from an array of tubules (500 μm O.D., 200 μm I.D.) connected to a series of independent reservoirs. The distance from the tubule mouth to the examined cell was approximately 100 μm. Rapid solution exchange was achieved by shifting the tubules horizontally with a micromanipulator.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS 11.5 software. The numerical values were reported as the means ± SE. Statistical significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Fisher’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons. P < 0.05 was considered as a significant result.

Results

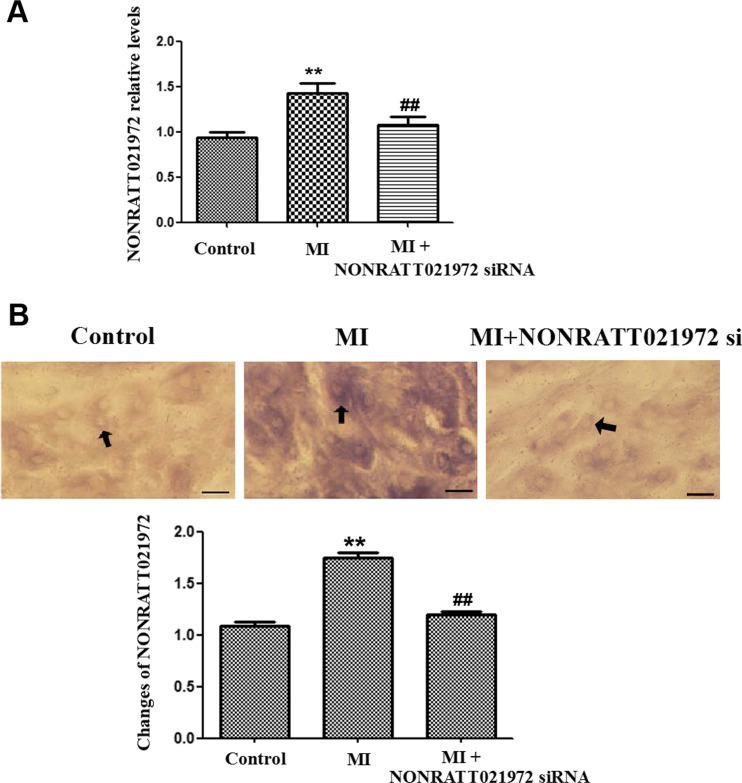

NONRATT021972 level is increased in the SCG of rats subject to MI

The expression of NONRATT021972 in the SCG was studied by real-time PCR and ISH. The results from both experiments showed that the expression of NONRATT021972 was significantly higher in the MI group than the control group (P < 0.01) (Fig. 1a–c). Treatment of the MI rats with NONRATT021972 siRNA reduced the expression of NONRATT021972 compared to MI group (P < 0.01).

Fig. 1.

The expression levels of NONRATT021972 in the SCG. a The expression levels of NONRATT021972 in the SCG were measured by quantitative real-time PCR, and the histogram shows the relative mRNA levels. The levels of NONRATT021972 expression in the SCG were significantly higher in the MI group than the con group. Treatment of the MI rats with NONRATT021972 siRNA decreased the expression of NONRATT021972 compared to MI group (P < 0.01). , n = 3. **P < 0.01 compared to the con group. b The expression of NONRATT021972 in the SCG was significantly higher in the MI group than in the control group, as assessed by ISH (P < 0.01). Treatment of the MI rats with NONRATT021972 siRNA downregulated the expression of NONRATT021972 compared to MI group (P < 0.01). , n = 5. **p < 0.01 compared with con group; ## p < 0.01 compared with MI. Scale bar = 50 μm; arrow shows the signal of NONRATT021972

Effects of NONRATT021972 siRNA on blood pressure, HR, ECG, and HRV

Blood pressure and HR detection

After 30 days, the SBP, DBP, and HR in the MI group were increased compared to the con (P < 0.01). The SBP, DBP, and HR in the MI group were also increased compared to the sham, MI + BBG, MI + NONRATT021972 si, and MI + P2X7 si groups (P < 0.01, F(HR)(5,24) = 8.32, F(SBP)(5,24) = 7.97, F(DBP)(5,24) = 7.09). The SBP, DBP, and HR in the MI rats treated with NONRATT021972 siRNA group were significantly decreased compared with rats in the MI group (P < 0.01). There were no differences among the con, sham, MI + BBG, MI + NONRATT021972, and MI + P2X7 si groups (P > 0.05, F(HR)(4,20) = 1.24, F(SBP)(4,20) = 2.10, F(DBP)(4,20) = 1.43), or between the MI and MI + SC si groups (P > 0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1.

The value of systolic blood pressure(SBP), diastolic blood pressure(DBP), heart rate (HR) in each group of rats

| Groups | SBP (mmHg) | DBP (mmHg) | HR (time/min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 101.350 ± 3.659 | 73.590 ± 7.133 | 307.800 ± 12.169 |

| Sham | 101.300 ± 8.341** | 72.890 ± 8.094** | 305.620 ± 21.853** |

| MI | 120.960 ± 1.646* | 89.760 ± 2.169* | 348.680 ± 24.135* |

| MI + BBG | 102.400 ± 5.682** | 71.480 ± 4.977** | 286.620 ± 17.872** |

| MI + SC si | 131.810 ± 20.831* | 84.960 ± 7.980* | 350.200 ± 25.577* |

| MI+ NONRATT021972 si | 101.840 ± 9.113** | 71.860 ± 4.494** | 301.760 ± 13.737** |

| MI + P2X7 si | 103.560 ± 5.279** | 72.84 ± 6.350** | 289.480 ± 22.684** |

The value of SBP, DBP, and HR in MI group was increased significantly, while the data in MI + BBG group, MI + NONRATT021972 si group, and MI + P2X7 si group had been reduced. The SBP, DBP, and HR in the MI rats treated with NONRATT021972 siRNA group were significantly decreased compared with rats in the MI group (P < 0.01). , n = 5. *p < 0.01 compared with con group; **p < 0.01 compared with MI

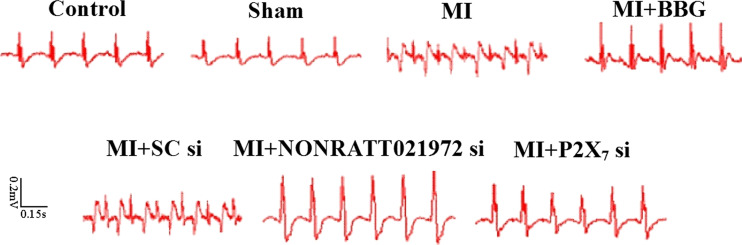

Changes in the ECGs of each group of rats

At 30 days after the MI injury, there was an obvious abnormal Q wave in the MI and MI + SC si groups. The abnormal changes in the ECGs in the MI rats treated with NONRATT021972 siRNA group were significantly improved compared with rats in the MI group. The abnormal changes in the ECGs resulting from the myocardial ischemia injury were greatly improved after the animals were treated with BBG, or P2X7 siRNA (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The changes in the ECGs in each group of rats. The ST segment in the ECGs of the myocardial ischemia rats was high upward. At 30 days after the MI injury, there was an obvious abnormal Q wave in the MI and MI + SC si groups. The abnormal changes in the ECGs in response to the MI injury were greatly improved after the animals were treated with BBG, NONRATT021972 siRNA, or P2X7 siRNA

Alterations in the HRV in the rats from each group

The LF and HF values in the MI group were significantly decreased compared to those in the control group (P < 0.01). The LF and HF values in the MI group were also significantly decreased compared to those in the sham, MI + BBG, MI + P2X7 si, and MI + NONRATT021972 si groups (P < 0.01, F(LF)(5,54) = 43.27, F(HF)(5,54) = 21.41, F(RMSSD)(5,54) = 28.24, F(SDANN)(5,54) = 19.56). The LF/HF value in the MI group was higher than those in the control group (P < 0.01). The LF/HF value in the MI group was also higher than those in the sham, MI + BBG, and MI + P2X7 si groups (P < 0.01, F(LF/HF)(6,63) = 6.22). LF/HF ratio in the MI rats was treated with NONRATT021972 siRNA was decreased compared to that in the MI rats (P < 0.01). There were no differences among the con, sham, MI + BBG, MI + P2X7 si group, and MI + NONRATT021972 si groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

The changes of the HRV in the rats of each group

| Groups | LF (ms2) | HF (ms2) | LF/HF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.27 ± 0.11 | 0.45 ± 0.08 | 0.54 ± 0.15 |

| Sham | 0.30 ± 0.15** | 0.52 ± 0.22** | 0.60 ± 0.13** |

| MI | 0.11 ± 0.08* | 0.14 ± 0.03* | 0.89 ± 0.07* |

| MI + BBG | 0.28 ± 0.09** | 0.55 ± 0.12** | 0.51 ± 0.10** |

| MI + SC si | 0.15 ± 0.04* | 0.18 ± 0.05* | 0.93 ± 0.08* |

| MI + NONRATT021972 si | 0.27 ± 0.07** | 0.47 ± 0.06** | 0.54 ± 0.11** |

| MI + P2X7 si | 0.30 ± 0.08** | 0.56 ± 0.01** | 0.50 ± 0.05** |

The LF/HF value in the MI group was higher than those in the control group (P < 0.01). LF/HF ratio in the MI rats were treated with NONRATT021972 siRNA was decreased compared to that in the MI rats (P < 0.01). , n = 5. *p < 0.01 compared with con group; **p < 0.01 compared with MI

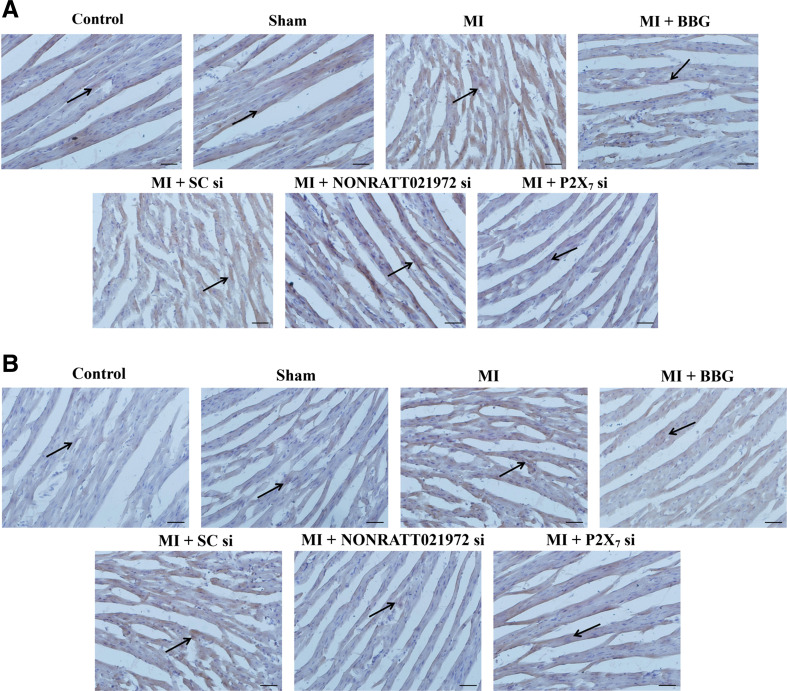

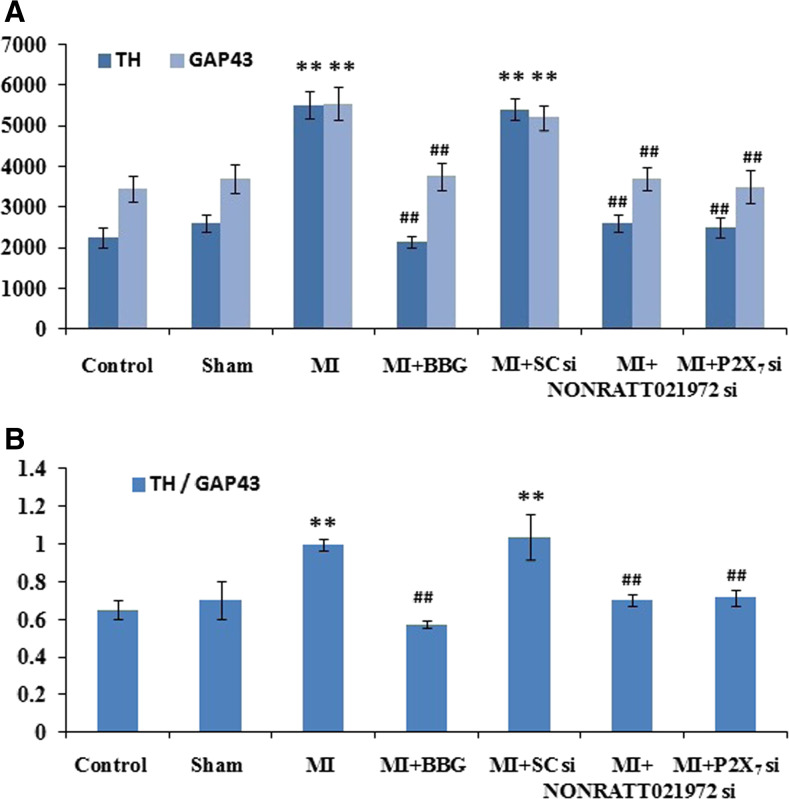

Effects of NONRATT021972 siRNA on the distribution and density of sympathetic nerve fibers around the ischemic myocardium

The distribution and density of sympathetic nerve fibers around the rats’ ischemic myocardia were measured by immunohistochemistry. Each stained slide contains six sections with most of the neural structures, and the average value represents the nerve density. The nerve density was the nerve area divided by the total area examined (μm2/mm2) [38]. The densities (IOD) of the GAP43- and TH-positive fibers around the ischemic myocardium of the MI group were significantly increased compared with the control group (P < 0.01). The IOD values of the GAP43- and TH-positive fibers around the ischemic myocardium of the MI group were also significantly higher than those in the sham, MI + BBG, MI + NONRATT021972 si, and MI + P2X7 si groups (P < 0.01), and the TH/GAP43 value in the MI rats was significantly increased compared to those in the con, sham, MI + BBG, and MI + P2X7 si groups (P < 0.01, F(TH/GAP43)(5,30) = 5.42). The TH/GAP43 value in the MI rats treated with NONRATT021972 siRNA group was significantly decreased compared with rats in the MI group (P < 0.01). This indicates that the regenerative nerve fibers were primarily sympathetic nerves (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The density of cardiac sympathetic nerve fibers in each group of rats. The densities of GAP43-positive (a, c) and TH-positive (b, c) fibers around the ischemic myocardium in the MI group were significantly higher than those in the con, sham, MI + BBG, MI + NONRATT021972 si, and MI + P2X7 si groups (P < 0.01), and the TH/GAP43 value (d) in the MI rats was significantly increased compared to those in the con, sham, MI + BBG, MI + NONRATT021972 si, and MI + P2X7 si groups (P < 0.01). The densities (integrated optical density (IOD)) of the GAP43- and TH-positive fibers around the ischemic myocardium of the MI group were significantly increased compared with the control group (P < 0.01). The TH/GAP43 value in the MI rats treated with NONRATT021972 siRNA group was significantly decreased compared with rats in the MI group (P < 0.01). This indicates that the regenerative nerve fibers were primarily sympathetic nerves. , n = 6. **P < 0.01, compared to the con group; ## P < 0. 01 vs the MI group. Scale bars 50 μm

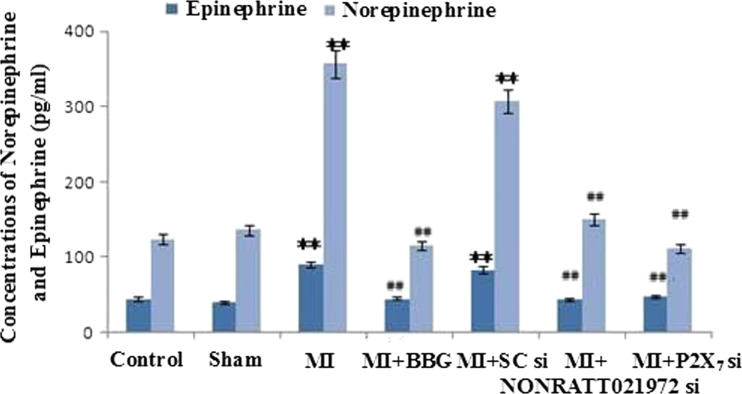

Impacts of NONRATT021972 siRNA on the serum levels of NE and EPI

The concentrations of NE and EPI in the rats’ sera were measured by ELISA. The serum concentrations of NE and EPI in the MI group were significantly increased compared with the control group (P < 0.01). The serum concentrations of NE and EPI in the MI group were also significantly higher than those in the sham, MI + BBG, and MI + P2X7 si groups (P < 0.01, F(NA)(5,30) = 4.58., F(EPI)(5,30) = 4.96). The serum concentrations of NE and EPI in the MI rats treated with NONRATT021972 siRNA group were significantly decreased compared with rats in the MI group (P < 0.01). There were no differences among the con, sham, MI + BBG, MI + NONRATT021972 si, and MI + P2X7 si groups (P > 0.05, F(NA)(4,25) = 1.15, F(EPI)(4,25) = 1.36), or between the MI and MI + SC si groups (P > 0.05) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The concentrations of NE and EPI in the rats’ sera were measured by ELISA. The serum concentrations of NE and EPI in the MI group were significantly higher than those in the con, sham, MI + BBG, MI + NONRATT021972 si, and MI + P2X7 si groups (P < 0.01). The serum concentrations of NE and EPI in the MI group were significantly increased compared with the control group (P < 0.01). The serum concentrations of NE and EPI in the MI rats treated with NONRATT021972 siRNA group were significantly decreased compared with rats in the MI group (P < 0.01). There were no differences between the con, sham, MI + BBG, MI + NONRATT021972 si, and MI + P2X7 si groups (P > 0.05), or between the MI and MI + SC si groups (P > 0.05). , n = 6. **P < 0.01, compared to the con group; ## P < 0. 01 vs the MI group

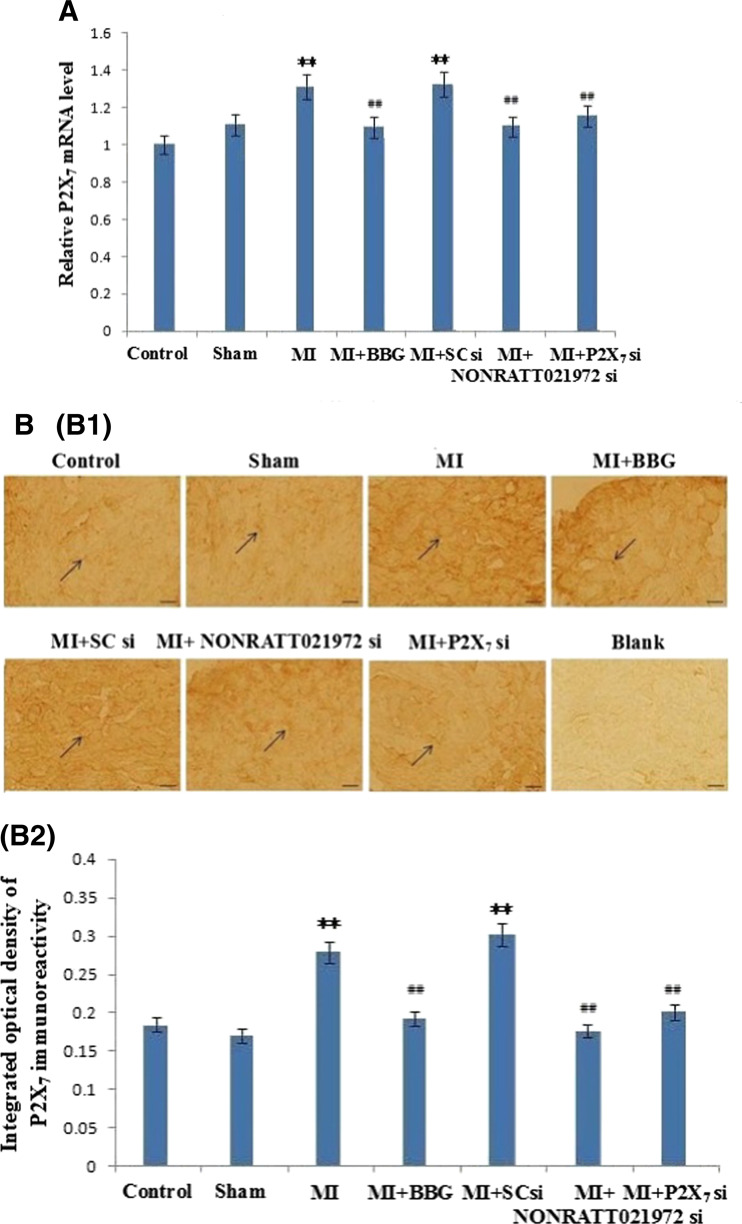

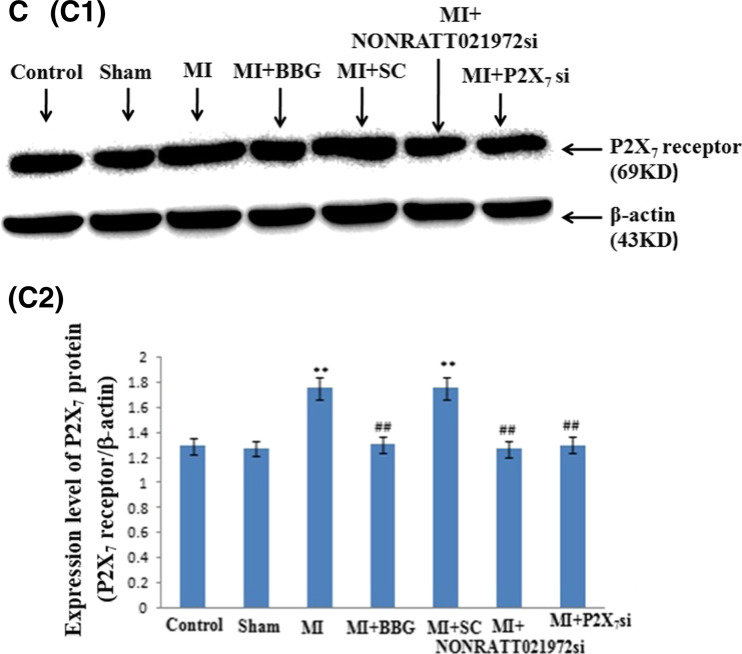

Effects of NONRATT021972 siRNA on the expression of P2X7 mRNA transcripts and protein in the SCG of the myocardial ischemic rats

The expression levels of the P2X7 mRNA transcripts in the SCG were measured by quantitative real-time PCR. The intensity of the P2X7 mRNA transcripts in the MI group was significantly increased compared with the control group (P < 0.01). The levels of the P2X7 mRNA transcripts in the MI and MI + SC si groups were also significantly higher than those in the sham groups (P < 0.01). The levels of the P2X7 mRNA transcripts in the MI rats treated with NONRATT021972 siRNA group were significantly decreased compared with rats in the MI group (P < 0.01). Meanwhile, the levels of the P2X7 mRNA transcripts in the MI + BBG, and MI + P2X7 si groups were also significantly lowered compared to the MI group (P < 0.01, F(5,12) = 10.79). There were no differences found among the con, sham, MI + BBG, MI + NONRATT021972 si, and MI + P2X7 si groups (P > 0.05, F (4,10) = 2.68), or between the MI and MI + SC si groups (P > 0.05) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

The levels of the P2X7 receptor mRNA, immunoreactivity, and protein in the SCG. a The histogram showed the relative mRNA levels were measured by quantitative real-time PCR. The levels of the P2X7 receptor mRNA in the MI and MI + SC si groups were significantly higher than those in the con, sham, MI + BBG, MI + NONRATT021972 si, and MI + P2X7 si groups (P < 0.01). The intensity of the P2X7 mRNA transcripts in the MI group was significantly increased compared with the control group (P < 0.01). The levels of the P2X7 mRNA transcripts in the MI rats treated with NONRATT021972 siRNA group were significantly decreased compared with rats in the MI group (P < 0.01). There were no differences between the con, sham, MI + BBG, MI + NONRATT021972 si, and MI + P2X7 si group (P > 0.05), or between the MI and MI + SC si groups (P > 0.05). BBG, NONRATT021972 siRNA, and P2X7 siRNA reduced the levels of the P2X7 receptor mRNA in the myocardial ischemia rats. , n = 3. **P < 0.01 compared to the Con group; ## P < 0. 01 vs the MI group. b P2X7 immunoreactivity in the SCG of each of group rats was tested by immunohistochemistry: representative photos of P2X7 immunoreactivity in the SCG (B1); the histogram showed the results of the integrated optical density (IOD) for each group (B2). The intensity of P2X7 immunoreactivity in the MI group was obviously increased compared to the con, sham, MI + BBG, MI + NONRATT021972 si, and MI + P2X7 si groups (P < 0.01). The intensity of the P2X7 immunoreactivity in the MI group was significantly increased compared with the control group (P < 0.01). The intensity of the P2X7 immunoreactivity in the MI rats treated with NONRATT021972 siRNA group were significantly decreased compared with rats in the MI group (P < 0.01). There were no differences between the con, sham, MI + BBG, MI + NONRATT021972 si, and MI + P2X7 si groups (P > 0.05), or between the MI and MI + SC si groups (P > 0.05). The arrows indicate the immunostained neurons. , n = 10. **P < 0.01 compared to the con group; ## P < 0. 01 vs the MI group. Scale bars 20 μm. c The expression of the P2X7 protein in the SCG of each group of rats was tested by Western blotting: representative blots of the P2X7 protein in the SCG (C1); the histogram showed the IOD of the results (C2). The IOD of P2X7 receptor expression in the MI group was obviously increased compared to the con, sham, MI + BBG, MI + NONRATT021972 si, and MI + P2X7 si groups (P < 0.01). The IOD of the P2X7 protein expression in the MI group was significantly increased compared with the control group (P < 0.01). The IOD of the P2X7 protein in the MI rats treated with NONRATT021972 siRNA group were significantly decreased compared with rats in the MI group (P < 0.01). There were no differences between the con, sham, MI + BBG, MI + NONRATT021972 si, and MI + P2X7 si groups (P > 0.05), or between the MI and MI + SC si groups (P > 0.05). , n = 6. **P < 0.01, compared to the con group; ## P < 0.01 vs the MI group

P2X7 immunoreactivity in the SCG was detected by immunohistochemistry. The intensity of the P2X7 immunoreactivity in the MI group was significantly increased compared with the control group (P < 0.01). The intensity of the P2X7 immunoreactivity in the MI group was obviously increased compared with the sham, MI + BBG, and MI + P2X7 si groups (P < 0.01, F(5,54) = 34.76). The intensity of the P2X7 immunoreactivity in the MI rats treated with NONRATT021972 siRNA group were significantly decreased compared with rats in the MI group (P < 0.01). There was no difference found among the con, sham, MI + BBG, MI + NONRATT021972 si, and MI + P2X7 si groups (P > 0.05, F(4,45) = 1.68), or between the MI and MI + SC si groups (P > 0.05).

The levels (IOD) of the P2X7 protein (normalized to each β-actin internal control) were analyzed by Western blot. The IOD of the P2X7 protein expression in the MI group was significantly increased compared with the control group (P < 0.01). The IOD in the MI group was also obviously increased compared with the sham, MI + BBG, and MI + P2X7 si groups (P < 0.01, F(5,30) = 60.58, F(SG)(5,30) = 47.66). The IOD of the P2X7 protein in the MI rats treated with NONRATT021972 siRNA group were significantly decreased compared with rats in the MI group (P < 0.01). There were no differences found among the con, sham, MI + BBG, MI + NONRATT021972 si, and MI + P2X7 si groups (P > 0.05, F(4,25) = 2.34, F(SG)(4,25) = 1.91), or between the MI and MI + SC si groups (P > 0.05) (Fig. 5 (C1, C2)). NONRATT021972 siRNA and P2X7 siRNA inhibited the up-regulated expression of the P2X7 receptor in the SCG after MI injury (Fig. 5 (B1, B2)).

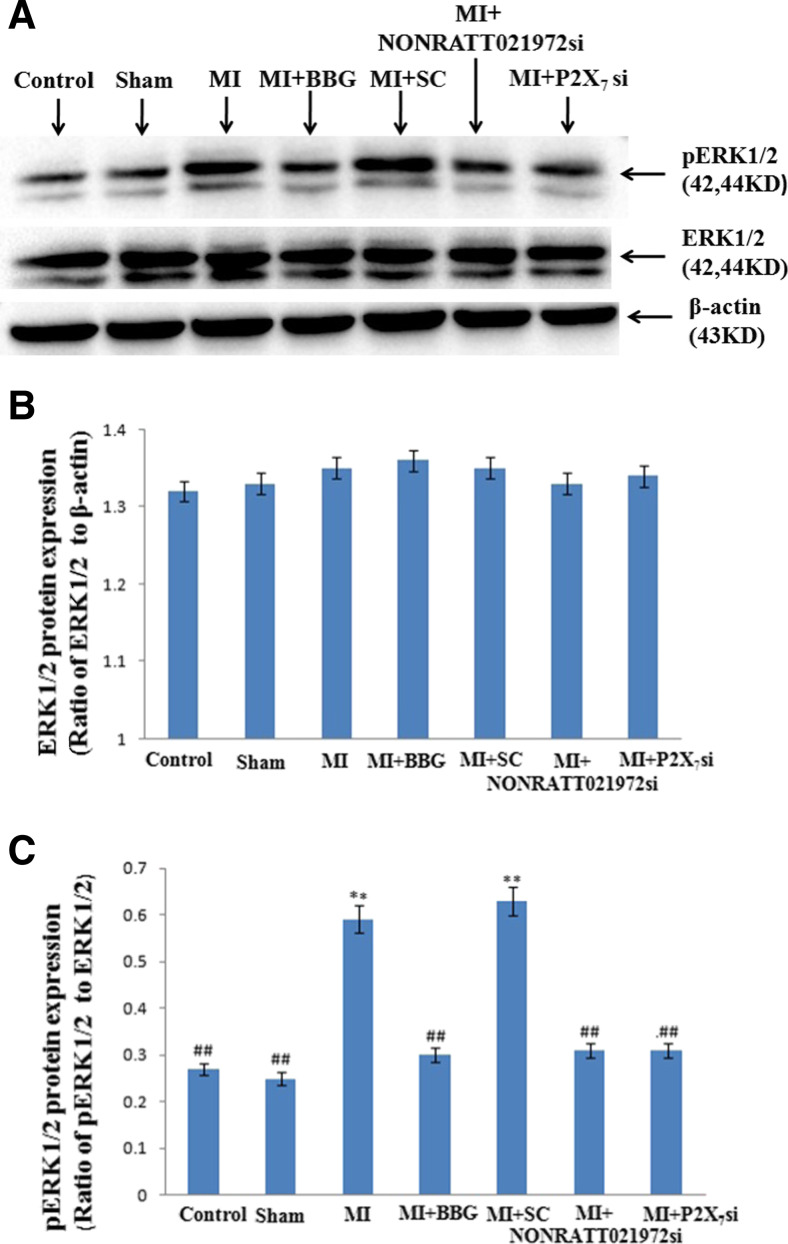

Effects of NONRATT021972 siRNA on the expression of the p-ERK1/2 proteins in the SCG of MI rats

The levels (IOD) of the ERK1/2 and p-ERK1/2 proteins (normalized to each β-actin internal control) were determined by Western blot. The IOD of p-ERK1/2 expression in the MI group was significantly increased compared with the control group (P < 0.01). The IOD of p-ERK1/2 expression in the MI group was also obviously increased compared with the sham, MI + BBG, and MI + P2X7 si groups (P < 0.01, F(5,30) = 63.67) (Fig. 6a, c). The IOD of p-ERK1/2 expression in the MI rats treated with NONRATT021972 siRNA group was significantly decreased compared with rats in the MI group (P < 0.01). There were no differences found among the con, sham, MI + BBG, MI + NONRATT021972 si, and MI + P2X7 si groups (P > 0.05, F(4,25) = 2.51) (Fig. 6a–c), or between the MI and MI + SC si groups (P > 0.05) (Fig. 6a–c).

Fig. 6.

The expression of ERK1/2 and p-ERK 1/2 receptor in the SCG of each group was tested by Western blotting. a Representative photos of the levels of the ERK1/2 and p-ERK1/2 proteins in the SCG. b The histogram showed the ratio of ERK1/2 to β-actin. c The histogram showed the ratio of p ERK1/2 to ERK1/2. The integrated optical density (IOD) of p-ERK1/2 expression in the MI group was obviously increased compared to the con, sham, MI + BBG, MI + NONRATT021972 si, and MI + P2X7 si groups (P < 0.01). The IOD of p-ERK1/2 expression in the MI group was significantly increased compared with the control group (P < 0.01). The IOD of p-ERK1/2 expression in the MI rats treated with NONRATT021972 siRNA group was significantly decreased compared with rats in the MI group (P < 0.01). There were no differences between the con, sham, MI + BBG, MI + NONRATT021972 si, and MI + P2X7 si groups (P > 0.05), or between the MI and MI + SC si groups (P > 0.05). , n = 6. ** P < 0.01, compared to the con group; ## P < 0.01 vs the MI group

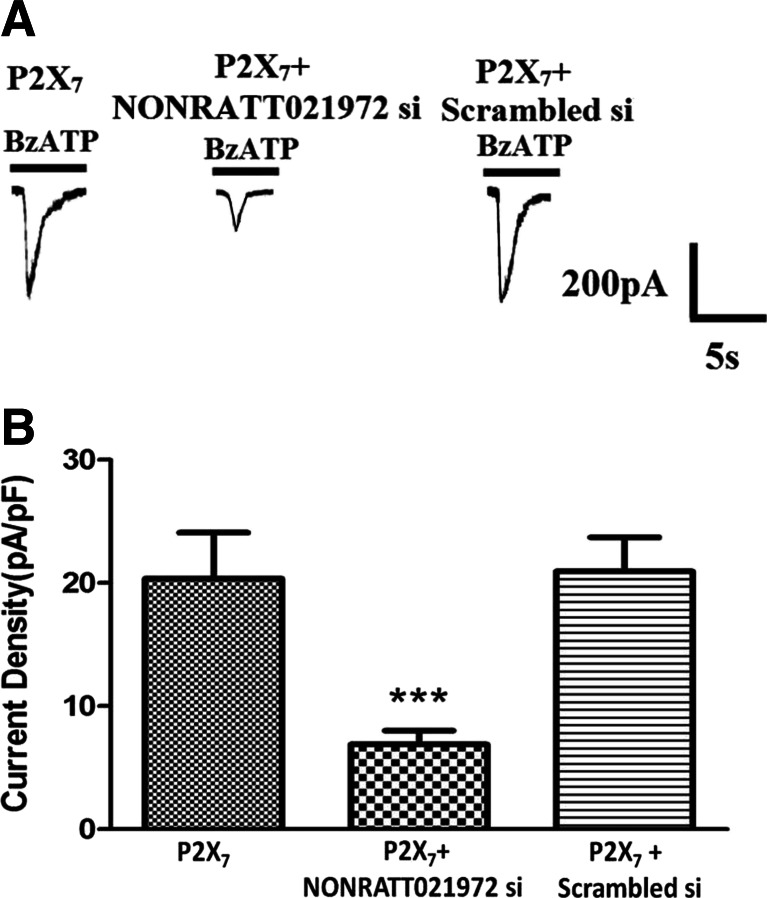

Effects of the NONRATT021972 siRNA on the P2X7 receptor agonist-activated currents in HEK293 cells

We compared the difference in the P2X7 receptor agonist BzATP-activated currents between HEK293 cells transfected with pEGFP-hP2X7 plasmid alone or cotransfected with the pEGFP-hP2X7 plasmid and NONRATT021972 siRNA. The results showed that the BzATP (100 μM)-activated currents in the cells transfected with the pEGFP-hP2X7 plasmid alone were larger than those in the cells cotransfected with the pEGFP-hP2X7 plasmid and NONRATT021972 siRNA (P < 0.05) (Fig. 7). There was no difference found in BzATP-activated currents between HEK293 cells transfected with pEGFP-hP2X7 plasmid alone or cotransfected with the pEGFP-hP2X7 plasmid and SC siRNA.

Fig. 7.

Effects of the NONRATT021972 siRNA on the P2X7 receptor agonist-activated current in HEK293 cells. Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were performed on HEK293 cells expressing hP2X7. Inward currents were evoked by 100 μM BzATP at a holding potential of −60 mV. a BzATP-activated currents were recorded in HEK293 cells transfected with hP2X7 alone or cotransfected with the NONRATT021972 siRNA. b The histogram shows the normalized, mean peak current (mean ± S, n = 12, **P < 0.01, compared to the con group; ## P < 0.01 vs the MI group). NONRATT021972 siRNA decreased the BzATP-induced currents in HEK293 cells expressing the hP2X7 receptor

Discussion

Cervical sympathetic ganglia innervate the myocardium and participate in sympathoexcitatory transmission [39–41]. The sympathetic nerves from the SCG release ATP through exocytosis [12, 19, 26]. After myocardial ischemia, the increased ATP levels excites the cardiac afferent nerve endings and elicits the sympathoexcitatory reflex, which is characterized by an increase in blood pressure and sympathetic nerve activity [14, 19, 24, 29]. Previous data from our laboratory showed that the serum ATP concentration was increased after the MI injury [32]. Moreover, we also observed that the SBP, DBP, and HR in the MI group were increased compared to the control and sham groups. Meanwhile, there was an abnormal Q wave in the MI rats. Therefore, MI injury is involved in the abnormal sympathoexcitatory reflex. Our results have shown that NONRATT021972 is highly expressed in the SCG of MI rats. The upregulation of NONRATT021972 in SCG may be involved in the pathophysiologic process of MI injury. In addition, the decreased SBP, DBP, and HR in the MI rats can recover to normal levels after the NONRATT021972 siRNA treatment. Moreover, the abnormal ECGs in the MI rats improved. The results suggest that the NONRATT021972 siRNA treatment could influence the pathophysiologic process of the MI injury.

Clinical data have shown that functional disorders of the autonomic nervous system (increased sympathetic activity or decreased vagus activity) are associated with arrhythmia [42–44]. HRV is a quantitative, noninvasive indicator of autonomic nervous function in the cardiovascular system [34, 45, 46]. LF represents the sympathetic activity and HF indicates the parasympathetic activity [45, 46]. The LF/HF values represent the balance condition between sympathetic and vagal tones [45, 46]. The significantly enhanced LF and decreased HF in the MI rats suggest that myocardial ischemia has intensified the sympathetic activity. In addition, the increased LF/HF ratio demonstrated that the balance of cardiac autonomic nerve regulation was disrupted in the MI rats. After the MI rats were treated with NONRATT021972 siRNA, the LF was decreased, the HF was increased, and LF/HF ratio was reduced compared to those in the MI rats, suggesting that NONRATT021972 siRNA treatment can improve the cardiac autonomic balance by reducing the abnormal cardiac sympathetic excitation.

Sympathetic nerve remodeling occurs in the ischemic area after MI injury [47, 48]. MI increases cardiac GAP43 expression in the infarcted area [48, 49]. GAP43 is a marker of nerve sprouting, and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) is a marker of sympathetic nerve fibers [50]. In the present study, the densities of the TH- and GAP43-positive fibers in the MI group were significantly increased when compared with the control and sham groups. The TH/GAP43 value was also significantly increased in the MI group compared to the control and sham groups, which suggest that the remodeled nerve fibers were primarily sympathetic nerves. The increased sympathetic distribution and density in the MI area might enhance sympathetic nerve activity. The TH/GAP43 value in the MI rats treated with NONRATT021972 siRNA was significantly decreased compared to the MI group. The modulation of cardiac sympathetic signaling is a major therapeutic strategy to prevent and treat the symptoms of angina pectoris in 50–60 % patients with coronary heart disease [48–52]. The NONRATT021972 siRNA treatment might decrease the abnormal innervations of the cardiac sympathetic nerves.

The excitation of the cardiovascular sympathetic nerves causes vasoconstriction and increases the heart rate and cardiac contractions. In contrast, the parasympathetic action of the vagal nerves in the cardiovascular tissues is inhibitory and decreases the heart rate and cardiac contractions [40–42]. The sympathetic and parasympathetic branches of the cardiac autonomic nervous system (ANS) work in a reciprocal fashion to modulate cardiac function primarily through actions on the cardiac pacemaker tissue [40, 41]. The ANS balance is driven by both sympathetic and parasympathetic activity and results from reciprocal sympathetic control, reciprocal parasympathetic control, coinhibition, and coactivation [40, 41, 43]. Compared to a normal subject, the sympathetic nerve activity is increased following MI injury [40, 41, 43]. NE is the principal neurotransmitter of the sympathetic neurons [40, 41]. After MI injury, the serum concentrations of NE and EPI in the MI group were significantly higher than those in the control and sham groups, suggesting that the sympathetic activity was increased after myocardial ischemia. The serum concentrations of NE and EPI were normalized after the MI rats were treated with NONRATT021972 siRNA. Therefore, the NONRATT021972 siRNA treatment could reduce the serum concentrations of NE and EPI by suppressing the abnormal sympathetic activity in the MI rats.

The cervical sympathetic ganglia have integrative properties [39, 52]. Clinical studies found that the removal of the SCG and other cervical sympathetic ganglia ameliorate 50–60 % of angina symptoms in patients with coronary heart disease [53, 54]. P2X receptors are involved in cardiovascular function and disease [11, 13–15, 55]. Previous studies from our laboratory showed that the upregulation of the P2X7 receptors in the cervical sympathetic ganglia (SG or SCG) after MI injury resulted in a increase in blood pressure and HR [18, 21, 22, 24, 29]. Our results also showed that the expression levels of the P2X7 mRNA and protein in the SCG were increased in the MI group compared to the control and sham groups. However, these levels were decreased after the MI rats were treated with the P2X7 antagonist BBG or the P2X7 siRNA. After the MI rats were treated with NONRATT021972 siRNA, the upregulated levels of the P2X7 mRNA and protein in the SCG were also normalized compared to those in the MI group. The downregulation of the P2X7 receptor was associated with reduced SBP and HR, which restores the cardiac autonomic balance. Thus, the NONRATT021972 siRNA treatment might regulate the P2X7 receptor-mediated cardiac autonomic function in the SCG.

The mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) ERK1 and ERK2 are linked to the activation of membrane receptors [56–58]. Our data showed that levels of p-ERK1/2 in the SCG of the MI rats were significantly higher than those in the control and sham rats. ERK phosphorylation participates in P2X receptor-mediated pathological changes [56–58]. The MI rats treated with NONRATT021972 siRNA had reversed the upregulation of p-ERK1/2 in the SCG. These results suggested that the activation of the P2X7 receptor after myocardial ischemia caused ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Therefore, the inhibitory effects of NONRATT021972 siRNA on the upregulated expression of the P2X7 receptor in the SCG after MI might be involved in the mechanism of intracellular ERK signaling.

The BzATP-activated current in HEK293 cells cotransfected with the pEGFP-hP2X7 plasmid and NONRATT021972 siRNA was decreased in comparison with the current in the cells transfected with the pEGFP-hP2X7 plasmid alone, suggesting that NONRATT021972 siRNA knockdown decreased the BzATP-induced currents in HEK293 cells expressing the hP2X7 receptor. LncRNAs are implicated in the pathophysiology of nervous system [9]. Inhibiting lncRNA function in vivo may provide therapeutic benefits [7, 8]. Thus, the NONRATT021972 siRNA treatment might block P2X7 activation to inhibit the abnormal changes in cardiac function induced by MI injury.

In summary, ATP activated the P2X7 receptor, which increased the cervical superior sympathetic activity after MI injury. Treatment with NONRATT021972 siRNA, P2X7 antagonist BBG, or P2X7 siRNA could inhibit the abnormal cervical sympathetic excitation mediated by P2X7 activation. Our findings suggest that the NONRATT021972 siRNA treatment could normalize the abnormal sympathetic activity mediated by upregulation of the P2X7 receptor in the SCG after MI.

Acknowledgments

These studies were supported by grants (nos. 81570735, 31560276, 81560219, 81560529, 81460200, 81171184, 31060139, and 81200853) from the National Natural Science Foundation of China, a grant (no. 20151122040105) from the Technology Pedestal and Society Development Project of Jiangxi Province, a grant (no. 20142BAB205028) from the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province, and grants (nos. GJJ13155 and GJJ14319) from the Educational Department of Jiangxi Province.

Abbreviations

- ATP

Adenosine triphosphate

- CK

Creatine kinase

- CK-MB

Creatine kinase isoform MB

- cTn-I

Cardiac troponin I

- DBP

Diastolic blood pressure

- ECG

Electrocardiogram

- ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- EPI

Epinephrine

- HE staining

Hematoxylin and eosin staining

- ERK1/2

Extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases

- HF

High frequency

- HR

Heart rate

- HRV

Heart rate variability

- IOD

Integrated optical density

- IL-6

Interleukin-6

- ISH

In situ hybridization

- LCA

Left coronary artery

- LDH

Lactate dehydrogenase

- LF

Low frequency

- MI

Myocardial ischemia

- NE

Norepinephrine

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- p-ERK1/2

Phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases

- SBP

Systolic blood pressure

- TH

Tyrosine hydroxylase

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor-α

- SCG

Superior cervical ganglia

- siRNA

Small interfering RNA

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Guihua Tu, Lifang Zou, and Shuangmei Liu are Joint first authors.

Change history

10/3/2020

Due to the authors��� carelessness, we used mistakenly images in Fig. 5B(B1) for P2X7 immunoreactivity in MI group(the second on the upper left) and MI+BBG group (The first one on the upper left).

Contributor Information

Guilin Li, Phone: +86 791 86360552, FAX: +86 791 86360552, Email: li.guilin@163.com.

Shangdong Liang, Phone: +86 791 86360552, FAX: +86 791 86360552, Email: liangsd@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Ponting CP, Belgard TG. Transcribed dark matter: meaning or myth? Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19(R2):R162–R168. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kapranov P, Cheng J, Dike S, Nix DA, Duttagupta R, Willingham AT, Stadler PF, Hertel J, Hackermuller J, Hofacker IL, Bell I, Cheung E, Drenkow J, Dumais E, Patel S, Helt G, Ganesh M, Ghosh S, Piccolboni A, Sementchenko V, Tammana H, Gingeras TR. RNA maps reveal new RNA classes and a possible function for pervasive transcription. Science. 2007;316(5830):1484–1488. doi: 10.1126/science.1138341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang Y, Liu N, Wang JP, Wang YQ, Yu XL, Wang ZB, Cheng XC, Zou Q. Regulatory long non-coding RNA and its functions. J Physiol Biochem. 2012;68(4):611–618. doi: 10.1007/s13105-012-0166-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vance KW, Ponting CP. Transcriptional regulatory functions of nuclear long noncoding RNAs. Trends Genet. 2014;30(8):348–355. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rinn JL, Chang HY. Genome regulation by long noncoding RNAs. Annu Rev Biochem. 2012;81:145–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-051410-092902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang KC, Chang HY. Molecular mechanisms of long noncoding RNAs. Mol Cell. 2011;43(6):904–914. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li L, Chang HY. Physiological roles of long noncoding RNAs: insight from knockout mice. Trends Cell Biol. 2014;24(10):594–602. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sauvageau M, Goff LA, Lodato S, Bonev B, Groff AF, Gerhardinger C, Sanchez-Gomez DB, Hacisuleyman E, Li E, Spence M, Liapis SC, Mallard W, Morse M, Swerdel MR, D'Ecclessis MF, Moore JC, Lai V, Gong G, Yancopoulos GD, Frendewey D, Kellis M, Hart RP, Valenzuela DM, Arlotta P, Rinn JL. Multiple knockout mouse models reveal lincRNAs are required for life and brain development. Elife. 2013;2:e1749. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qureshi IA, Mattick JS, Mehler MF. Long non-coding RNAs in nervous system function and disease. Brain Res. 2010;1338:20–35. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.03.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burnstock G. Physiology and pathophysiology of purinergic neurotransmission. Physiol Rev. 2007;87(2):659–797. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00043.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burnstock G, Krügel U, Abbracchio MP, Illes P. Purinergic signalling: from normal behaviour to pathological brain function. Prog Neurobiol. 2011;95(2):229–274. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vizi ES, Liang SD, Sperlagh B, Kittel A, Juranyi Z. Studies on the release and extracellular metabolism of endogenous ATP in rat superior cervical ganglion: support for neurotransmitter role of ATP. Neuroscience. 1997;79(3):893–903. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(96)00658-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erlinge D, Burnstock G. P2 receptors in cardiovascular regulation and disease. Purinergic Signal. 2008;4(1):1–20. doi: 10.1007/s11302-007-9078-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fu LW, Longhurst JC. A new function for ATP: activating cardiac sympathetic afferents during myocardial ischemia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;299(6):1762–1771. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00822.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liang S, Xu C, Li G, Gao Y. P2X receptors and modulation of pain transmission: focus on effects of drugs and compounds used in traditional Chinese medicine. Neurochem Int. 2010;57(7):705–712. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ando RD, Sperlagh B. The role of glutamate release mediated by extrasynaptic P2X7 receptors in animal models of neuropathic pain. Brain Res Bull. 2013;93:80–85. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sperlágh B, Vizi ES, Wirkner K, Illes P. P2X7 receptors in the nervous system. Prog Neurobiol. 2006;78(6):327–346. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kong F, Liu S, Xu C, Liu J, Li G, Li G, Gao Y, Lin H, Tu G, Peng H, Qiu S, Fan B, Zhu Q, Yu S, Zheng C, Liang S. Electrophysiological studies of upregulated P2X7 receptors in rat superior cervical ganglia after myocardial ischemic injury. Neurochem Int. 2013;63(3):230–237. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li G, Liu S, Yang Y, Xie J, Liu J, Kong F, Tu G, Wu R, Li G, Liang S. Effects of oxymatrine on sympathoexcitatory reflex induced by myocardial ischemic signaling mediated by P2X3 receptors in rat SCG and DRG. Brain Res Bull. 2011;84(6):419–424. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li G, Liu S, Zhang J, Yu K, Xu C, Lin J, Li X, Liang S. Increased sympathoexcitatory reflex induced by myocardial ischemic nociceptive signaling via P2X2/3 receptor in rat superior cervical ganglia. Neurochem Int. 2010;56(8):984–990. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu S, Yu S, Xu C, Peng L, Xu H, Zhang C, Li G, Gao Y, Fan B, Zhu Q, Zheng C, Wu B, Song M, Wu Q, Liang S. Puerarin alleviates aggravated sympathoexcitatory response induced by myocardial ischemia via regulating P2X3 receptor in rat superior cervical ganglia. Neurochem Int. 2014;70:39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu S, Zhang C, Shi Q, Li G, Song M, Gao Y, Xu C, Xu H, Fan B, Yu S, Zheng C, Zhu Q, Wu B, Peng L, Xiong H, Wu Q, Liang S. Puerarin blocks the signaling transmission mediated by P2X3 in SG and DRG to relieve myocardial ischemic damage. Brain Res Bull. 2014;101:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shao L, Liang S, Li G, Xu C, Zhang C. Exploration of P2X3 in the rat stellate ganglia after myocardial ischemia. Acta Histochem. 2007;109(4):330–337. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tu G, Li G, Peng H, Hu J, Liu J, Kong F, Liu S, Gao Y, Xu C, Xu X, Qiu S, Fan B, Zhu Q, Yu S, Zheng C, Wu B, Peng L, Song M, Wu Q, Liang S. P2X(7) inhibition in stellate ganglia prevents the increased sympathoexcitatory reflex via sensory-sympathetic coupling induced by myocardial ischemic injury. Brain Res Bull. 2013;96:71–85. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Y, Li G, Yu K, Liang S, Wan F, Xu C, Gao Y, Liu S, Lin J. Expressions of P2X2 and P2X3 receptors in rat nodose neurons after myocardial ischemia injury. Auton Neurosci. 2009;145(1–2):71–75. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Y, Li G, Liang S, Zhang A, Xu C, Gao Y, Zhang C, Wan F. Role of P2X3 receptor in myocardial ischemia injury and nociceptive sensory transmission. Auton Neurosci. 2008;139(1–2):30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang CP, Xu CS, Liang SD, Li GL, Gao Y, Wang YX, Zhang AX, Wan F. The involvement of P2X3 receptors of rat sympathetic ganglia in cardiac nociceptive transmission. J Physiol Biochem. 2007;63(3):249–257. doi: 10.1007/BF03165788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang C, Li G, Liang S, Xu C, Zhu G, Wang Y, Zhang A, Wan F. Myocardial ischemic nociceptive signaling mediated by P2X3 receptor in rat stellate ganglion neurons. Brain Res Bull. 2008;75(1):77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2007.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu J, Li G, Peng H, Tu G, Kong F, Liu S, Gao Y, Xu H, Qiu S, Fan B, Zhu Q, Yu S, Zheng C, Wu B, Peng L, Song M, Wu Q, Li G, Liang S. Sensory-sympathetic coupling in superior cervical ganglia after myocardial ischemic injury facilitates sympathoexcitatory action via P2X7 receptor. Purinergic Signal. 2013;9(3):463–479. doi: 10.1007/s11302-013-9367-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu Y, Fuscoe JC, Zhao C, Guo C, Jia M, Qing T, Bannon DI, Lancashire L, Bao W, Du T, Luo H, Su Z, Jones WD, Moland CL, Branham WS, Qian F, Ning B, Li Y, Hong H, Guo L, Mei N, Shi T, Wang KY, Wolfinger RD, Nikolsky Y, Walker SJ, Duerksen-Hughes P, Mason CE, Tong W, Thierry-Mieg J, Thierry-Mieg D, Shi L, Wang C. A rat RNA-Seq transcriptomic BodyMap across 11 organs and 4 developmental stages. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3230. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zou L, Tu G, Xie W, Wen S, Xie Q, Liu S, Li G, Gao Y, Xu H, Wang S, Xue Y, Wu B, Lv Q, Ying M, Zhang X, Liang S. LncRNA NONRATT021972 involved the pathophysiologic processes mediated by P2X7 receptors in stellate ganglia after myocardial ischemic injury. Purinergic Signal. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s11302-015-9486-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang J, Liu S, Xu B, Li G, Li G, Huang A, Wu B, Peng L, Song M, Xie Q, Lin W, Xie W, Wen S, Zhang Z, Xu X, Liang S. Study of baicalin on sympathoexcitation induced by myocardial ischemia via P2X3 receptor in superior cervical ganglia. Auton Neurosci. 2015;189:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arbeloa J, Perez-Samartin A, Gottlieb M, Matute C. P2X7 receptor blockade prevents ATP excitotoxicity in neurons and reduces brain damage after ischemia. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;45(3):954–961. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harris P, Sommargren C, Stein P, Fung G, Drew B. Heart rate variability measurement and clinical depression in acute coronary syndrome patients: narrative review of recent literature. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014;10:1335. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S57523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pipatpiboon N, Sripetchwandee J, Chattipakorn SC, Chattipakorn N. Effects of PPARγ agonist on heart rate variability and cardiac mitochondrial function in obese-insulin resistant rats. Int J Cardiol. 2015;201:121–122. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.07.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takase B, Hikita H, Satomura K, Mastui T, Ohsuzu F, Kurita A. Effect of nipradilol on silent myocardial ischemia and heart rate variability in chronic stable angina. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2002;16(1):43–51. doi: 10.1023/A:1015319632065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu H, Wu B, Jiang F, Xiong S, Zhang B, Li G, Liu S, Gao Y, Xu C, Tu G, Peng H, Liang S, Xiong H. High fatty acids modulate P2X7 expression and IL-6 release via the p38 MAPK pathway in PC12 cells. Brain Res Bull. 2013;94:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu YB. Sympathetic Nerve Sprouting, Electrical Remodeling, and Increased Vulnerability to Ventricular Fibrillation in Hypercholesterolemic Rabbits. Circ Res. 2003;92(10):1145–1152. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000072999.51484.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Armour JA. Potential clinical relevance of the ‘little brain’on the mammalian heart. Exp Physiol. 2008;93(2):165–176. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.041178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gibbins I. Functional organization of autonomic neural pathways. Organogenesis. 2014;9(3):169–175. doi: 10.4161/org.25126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hasan W. Autonomic cardiac innervation: development and adult plasticity. Organogenesis. 2014;9(3):176–193. doi: 10.4161/org.24892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abboud FM. In search of autonomic balance: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;298(6):R1449–R1467. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00130.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berntson GG, Norman GJ, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Cardiac autonomic balance versus cardiac regulatory capacity. Psychophysiology. 2008;45(4):643–652. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2008.00652.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kobayashi M, Massiello A, Karimov JH, Van Wagoner DR, Fukamachi K. Cardiac autonomic nerve stimulation in the treatment of heart failure. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96(1):339–345. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.12.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haensel A, Mills PJ, Nelesen RA, Ziegler MG, Dimsdale JE. The relationship between heart rate variability and inflammatory markers in cardiovascular diseases. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33(10):1305–1312. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kleiger RE, Stein PK, Bigger JT. Heart rate variability: measurement and clinical utility. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2005;10(1):88–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-474X.2005.10101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ajijola OA, Yagishita D, Patel KJ, Vaseghi M, Zhou W, Yamakawa K, So E, Lux RL, Mahajan A, Shivkumar K. Focal myocardial infarction induces global remodeling of cardiac sympathetic innervation: neural remodeling in a spatial context. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;305(7):H1031–H1040. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00434.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou S. Mechanisms of cardiac nerve sprouting after myocardial infarction in dogs. Circ Res. 2004;95(1):76–83. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000133678.22968.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ajijola OA, Shivkumar K. Neural remodeling and myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(10):962–964. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ghilardi JR, Freeman KT, Jimenez Andrade JM, Coughlin KA, Kaczmarska MJ, Castaneda Corral G, Bloom AP, Kuskowski MA, Mantyh PW. Neuroplasticity of sensory and sympathetic nerve fibers in a mouse model of a painful arthritic joint. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2012;64(7):2223–2232. doi: 10.1002/art.34385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bourke T, Vaseghi M, Michowitz Y, Sankhla V, Shah M, Swapna N, Boyle NG, Mahajan A, Narasimhan C, Lokhandwala Y, Shivkumar K. Neuraxial modulation for refractory ventricular arrhythmias: value of thoracic epidural anesthesia and surgical left cardiac sympathetic denervation. Circulation. 2010;121(21):2255–2262. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.929703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boehm S, Kubista H. Fine tuning of sympathetic transmitter release via ionotropic and metabotropic presynaptic receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2002;54(1):43–99. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pan HL, Chen SR. Myocardial ischemia recruits mechanically insensitive cardiac sympathetic afferents in cats. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87(2):660–668. doi: 10.1152/jn.00506.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pather N, Partab P, Singh B, Satyapal KS. The sympathetic contributions to the cardiac plexus. Surg Radiol Anat. 2003;25(3–4):210–215. doi: 10.1007/s00276-003-0113-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Burnstock G, Pelleg A. Cardiac purinergic signalling in health and disease. Purinergic Signalling. 2015;11(1):1–46. doi: 10.1007/s11302-014-9436-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dai Y, Fukuoka T, Wang H, Yamanaka H, Obata K, Tokunaga A, Noguchi K. Contribution of sensitized P2X receptors in inflamed tissue to the mechanical hypersensitivity revealed by phosphorylated ERK in DRG neurons. Pain. 2004;108(3):258–266. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ponnusamy M, Liu N, Gong R, Yan H, Zhuang S. ERK pathway mediates P2X7 expression and cell death in renal interstitial fibroblasts exposed to necrotic renal epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011;301(3):F650–F659. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00215.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Seino D, Tokunaga A, Tachibana T, Yoshiya S, Dai Y, Obata K, Yamanaka H, Kobayashi K, Noguchi K. The role of ERK signaling and the P2X receptor on mechanical pain evoked by movement of inflamed knee joint. Pain. 2006;123(1):193–203. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]