Abstract

Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) is an emerging pathogen, first recognized in 2012, with a high case fatality risk, no vaccine, and no treatment beyond supportive care. We estimated the relative risks of death and severe disease among MERS-CoV patients in the Middle East between 2012 and 2015 for several risk factors, using Poisson regression with robust variance and a bootstrap-based expectation maximization algorithm to handle extensive missing data. Increased age and underlying comorbidity were risk factors for both death and severe disease, while cases arising in Saudi Arabia were more likely to be severe. Cases occurring later in the emergence of MERS-CoV and among health-care workers were less serious. This study represents an attempt to estimate risk factors for an emerging infectious disease using open data and to address some of the uncertainty surrounding MERS-CoV epidemiology.

Keywords: coronaviruses, emerging infections, MERS-CoV, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, respiratory infections, zoonotic infections

Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) is a stage 3 zoonosis that has been reported in 26 countries, including the United States (1, 2). The virus was first recognized in Saudi Arabia in 2012, though it may have been circulating in the region much longer (3, 4). As of August 18, 2015, there have been 1,413 confirmed cases and 502 deaths (5). The virus causes severe respiratory illness in humans and has a mortality rate of 30%–40% (6). Treatment for MERS-CoV cases is limited to supportive care.

Certain groups may be at higher risk of contracting the virus or of having their cases ascertained due to illness severity, including males and those with comorbid medical conditions, such as diabetes and heart disease. Common symptoms include fever, cough, shortness of breath, chest pain, and diarrhea (7, 8). The virus is probably transmitted from camels to humans, and stuttering chains (groups of cases linked by a continuous chain of transmission events that arise periodically) of human-to-human transmission are also possible (4, 7–10). Human-to-human transmission occurs between 2 people in close contact, a circumstance common in households and health-care settings. Early identification and isolation of cases is critical for limiting spread of the virus.

Information on the epidemiology of MERS-CoV has been limited to date. Prior work on the 2013 influenza (A)H7N9 outbreak found that line listings of cases aggregated from publicly available sources like media and public health reports compare favorably to official line listings (11). These public line listings can be used to gain insight into an ongoing outbreak in a timely manner, as official data tend to be released only after outbreaks are over. Real-time analyses are vital to planning and implementing effective public health control measures to prevent the spread of the disease. We used publicly available data to evaluate the risks of death and severe disease among patients with MERS-CoV.

METHODS

Data sources

A publicly accessible line listing of MERS-CoV cases, maintained by Dr. Andrew Rambaut and available online (12), was accessed on August 4, 2015. This line listing contained 1,291 cases of MERS-CoV infection pulled from a number of sources, including the World Health Organization and the government of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. This data set has often been more up-to-date than official World Health Organization case reports, especially early in the epidemic. The outcomes available are as reported and do not necessarily reflect the final status of the patient after prolonged follow-up, so some misclassification of outcomes is possible. The majority of MERS-CoV cases occurred in Saudi Arabia, South Korea, and the United Arab Emirates (Appendix Table 1). The outbreak in South Korea was excluded from the analysis because of its unique nature, resulting in 1,105 cases after exclusion.

Exposure definition and covariate selection

Outcomes of interest were death and severe disease. The status of the patient as either alive or deceased was determined by whether or not the patient had died at the time of initial reporting. Patients with severe disease were considered those who had either died from their infection or required critical care at the time of initial reporting, as opposed to those who experienced few or less serious complications.

Risk factors considered were the patient's age, the date of onset of the infection, the presence or absence of any underlying comorbidity such as cardiac or renal disease, reported contact with camels or other animals, whether or not the patient was employed as a health-care worker, whether or not the case was a primary or secondary case (based on reported contact with an existing case), whether or not the case arose in Saudi Arabia (the nation in which the majority of cases originated), the patient's sex, the number of days since January 1, 2012, and the time between onset of infection and subsequent hospitalization.

Missing data

Because of the emerging nature of the disease, the widely varying sources from which the case reports were drawn, difficulty in case ascertainment, and sparse reporting, the data set used (12) had extensively missing data. There were 920 cases with missing information on 1 or more variables (including outcome variables), making conventional complete-case analysis essentially impossible. Because there was no evidence that these cases were missing data completely at random, estimates could be biased.

We used a bootstrap-based expectation maximization method to multiply impute the missing information (13). One hundred imputations were used, based on the assumption that all data for the variables included in the analysis, missing or observed, came from a multivariate normal distribution. A ridge prior of 1% of the empirical data was used to assist with the numerical stability of the algorithm. The ridge prior in essence adds an additional number of observations equal to 1% of the data set with the same mean and variance as the observed data, but with no covariance. This shrinks the covariance between the variables in the imputation model and assists the algorithm in converging on a stable solution, which is sometimes necessary with high degrees of missingness, as in this case. Priors using 0.5% of the data or 2% of the data did not result in meaningful differences in the results (not shown).

Regression models

Poisson regression models using a robust variance estimator (14) were used to estimate the univariate relative risk of either outcome according to each potential risk factor. These models are comparable to those obtained using binomial regression, though often more computationally tractable. Those variables that were moderately associated (P < 0.20) with the outcome were included in a multivariate risk model. All analysis was performed with the R statistical programming language (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) using the Amelia2 package for multiple imputation (15).

Human subjects approval

Because this work used entirely publicly available information with no personal identifiers, it was determined to not require approval by an institutional review board.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics

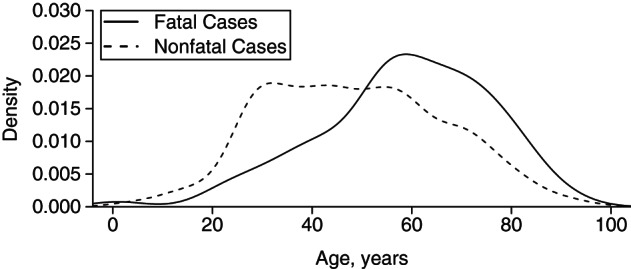

The distribution of patient ages for both fatal and nonfatal cases is shown in Figure 1. The distributions of other variables, including the numbers of missing values, are reported in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Gaussian kernel-smoothed age distributions of fatal and nonfatal cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus from 2012 to 2015.

Table 1.

Demographic and Risk Factor Characteristics of Patients With Reported Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Infection, 2012–2015

| Variable | All Patients |

Severe Cases |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | Mean (SD) | No. | % | Mean (SD) | |

| Age, years | 50 (18) | 57 (17) | ||||

| Missing data | 11 | 1.0 | 11 | 2.1 | ||

| Time of onset (days since January 1, 2012) | 911 (255) | 881 (277) | ||||

| Missing data | 461 | 41.7 | 163 | 31.8 | ||

| Underlying comorbidity | ||||||

| Yes | 565 | 51.1 | 361 | 70.4 | ||

| No | 526 | 47.6 | 143 | 27.9 | ||

| Missing data | 14 | 1.3 | 9 | 1.8 | ||

| Reported animal contact | ||||||

| Yes | 105 | 9.5 | 53 | 10.3 | ||

| No | 278 | 25.2 | 146 | 28.5 | ||

| Missing data | 722 | 65.3 | 314 | 61.2 | ||

| Reported camel contact | ||||||

| Yes | 84 | 7.6 | 41 | 8.0 | ||

| No | 233 | 21.1 | 117 | 22.8 | ||

| Missing data | 788 | 71.3 | 355 | 69.2 | ||

| Health-care worker | ||||||

| Yes | 168 | 15.2 | 38 | 7.4 | ||

| No | 351 | 31.8 | 189 | 36.8 | ||

| Missing data | 586 | 53.0 | 286 | 55.8 | ||

| Case type | ||||||

| Primary | 216 | 19.5 | 130 | 25.3 | ||

| Secondary | 484 | 43.8 | 151 | 29.4 | ||

| Missing data | 405 | 36.7 | 232 | 45.2 | ||

| Case origin | ||||||

| Saudi Arabia | 959 | 86.8 | 457 | 89.1 | ||

| Other country | 146 | 13.2 | 56 | 10.9 | ||

| Missing data | ||||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 736 | 66.6 | 370 | 72.1 | ||

| Female | 346 | 31.3 | 132 | 25.7 | ||

| Missing data | 23 | 2.1 | 11 | 2.1 | ||

| Delay in hospitalization, days | 4.91 (4.41) | 3.80 (4.39) | ||||

| Missing data | 577 | 52.2 | 216 | 42.1 | ||

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Risk factors for reported mortality

The estimated relative risk of death and corresponding 95% confidence intervals for the covariates described in the Methods section are shown in Table 2. As with any emerging infection, both the presence and the absence of associations with putative risk factors warrant reporting. Univariate analysis showed that reported contact with camels or other animals, cases occurring in Saudi Arabia, and case type (a case's being primary vs. secondary) were not associated with reported mortality. Employment as a health-care worker and an increased amount of time between disease onset and hospitalization had minor protective associations with reported mortality. Older age and underlying comorbidity were associated with increased risks of mortality, while female patients and cases with a later time of infection onset (in days since January 1, 2012) had lower risks of mortality. Upon multivariate adjustment, most of the estimated associations were attenuated, and neither female sex nor time between disease onset and hospitalization remained an independent risk factor.

Table 2.

Estimated Relative Risks of Death and Severe Disease at the Time of Reporting for Patients With Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus, 2012–2015

| Variable | Death |

Severe Disease |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 95% CI | aRRa | 95% CI | RR | 95% CI | aRRb | 95% CI | |

| Age | 1.02 | 1.02, 1.03 | 1.01 | 1.00, 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.02, 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.01, 1.01 |

| Time of onsetc | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 |

| Underlying comorbidity | 2.51 | 1.87, 3.37 | 1.99 | 1.39, 2.86 | 2.23 | 1.93, 2.46 | 1.65 | 1.39, 1.97 |

| Animal contact | 1.16 | 0.74, 1.80 | 1.10 | 0.89, 1.35 | ||||

| Camel contact | 1.19 | 0.73, 1.93 | 1.10 | 0.89, 1.37 | ||||

| Health-care worker | 0.52 | 0.33, 0.81 | 0.46 | 0.28, 0.75 | 0.49 | 040, 0.60 | 0.61 | 0.48, 0.79 |

| Secondary case | 0.84 | 0.60, 1.18 | 0.60 | 0.52, 0.70 | 0.82 | 0.69, 0.97 | ||

| Saudi Arabia | 0.85 | 0.60, 1.21 | 1.18 | 0.95, 1.45 | 1.24 | 1.02, 1.52 | ||

| Female sex | 0.75 | 0.56, 1.00 | 0.93 | 0.70, 1.25 | 0.77 | 0.66, 0.89 | 0.92 | 0.81, 1.06 |

| Hospitalization delayd | 0.85 | 0.81, 0.89 | 0.99 | 0.95.1.03 | 0.99 | 0.97, 1.01 | ||

Abbreviations: aRR, adjusted relative risk; CI, confidence interval; RR, relative risk.

a Multivariate model that adjusted for age, presence of comorbidity, reported contact with animals, health-care worker status, case type (primary vs. secondary), and patient sex.

b Multivariate model that adjusted for age, time of onset, presence of comorbidity, health-care worker status, case type (primary vs. secondary), and patient sex.

c Days since January 1, 2012.

d Reported number of days between onset and subsequent hospitalization.

Risk factors for reported severe disease

The estimated relative risks of severe disease and corresponding 95% confidence intervals are shown in Table 2. Reported contact with camels or other animals, regardless of whether or not the case arose in Saudi Arabia, and longer delays between disease onset and hospitalization were not associated with an increased risk of severe disease. Increased age and the presence of underlying comorbidity were associated with an increased risk of severe disease. Female sex, having a secondary case, having a case arising later in time, and employment as a health-care worker were protective against severe disease.

As with the risk of reported death, the multivariate associations were largely attenuated from the univariate associations, and notably, female sex was no longer protective once other variables had been controlled for. As compared with the risk of death, the estimated associations for severe disease were frequently closer to the null.

DISCUSSION

The emergence of a novel infectious disease presents a particular challenge to timely epidemiologic research, as the existence of sparse and irregularly collected data competes with the need to identify risk factors associated with the disease and its outcomes. A dearth of openly shared data impedes research efforts, such as the construction of mathematical models or broader-scale risk assessments. We have attempted to address this for MERS-CoV, using a regularly updated, publicly available data set. The use of multivariate models with allowance for extensively missing data has allowed the identification of some previously suggested risk factors that do not appear to be so upon adjustment for other covariates. For example, female patients were not necessarily at lower risk for disease after adjustment, nor were primary cases at higher risk for fatal infections. Issues of data quality and “missingness” during outbreaks necessitate the use of robust techniques for handling missing data.

We found that older age and underlying comorbidity were associated with increased risks of both death and severe disease. While not a surprising finding, this does suggest that older and sicker patients merit heightened vigilance. Additionally, cases arising progressively later during the epidemic have been associated with lower risks of both death and severe disease at the time of initial reporting, suggesting that treatment methods for MERS-CoV may be increasing in efficacy. Alternately, the proportion of mild and asymptomatic cases has been rising over time, suggesting that less severe cases are becoming more likely to be ascertained as a result of epidemiologic investigation. This is supported by temporal trends in the missingness of the data, which grows less severe later in the epidemic.

This study was not without limitations, especially those stemming from the data used. Patient outcomes were identified at the time of reporting, rather than based on follow-up, so it is possible that some patients counted as living or without severe disease may have experienced serious or fatal complications after reporting, which would not have been recorded in the data. There is also the possibility of unmeasured confounding biasing these estimates or the multiple imputation model not fully addressing the missingness within the data set. These issues are unlikely to be resolved without more resource-intensive population-based studies.

Despite these shortcomings, the study represents an attempt to quantify the known risk factors for MERS-CoV using the best available and open data. While the estimates are imperfect, they are superior to univariate associations that do not control for confounding, or allowing paralysis in the face of difficult and imperfect data to deprive public health planners of potentially useful information. These estimates can and should be revised as more becomes known about the disease, but for the moment, they represent the current state of our knowledge about MERS-CoV and its impact on human health outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Author affiliations: Network Dynamics and Simulation Science Laboratory, Biocomplexity Institute of Virginia Tech, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, Virginia (Eric T. Lofgren, Caitlin M. Rivers); and Engineering Systems Division, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts (Maimuna S. Majumder).

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Models of Infectious Disease Agent Study (MIDAS) grant 5U01GM070694-11) and the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (grant HDTRA1-11-1-0016 and Comprehensive National Incident Management System (CNIMS) contract HDTRA1-11-D-0016-0001).

We acknowledge Twitter Inc. (San Francisco, California) and the producers of other online collaboration tools for facilitating this research.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Appendix Table 1.

Locations of known cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus as of August 4, 2015a

| Country | No. of Cases |

|---|---|

| France | 1 |

| Iran | 8 |

| Italy | 2 |

| Jordan | 20 |

| Saudi Arabia | 959 |

| Kuwait | 3 |

| Lebanon | 1 |

| Omar | 9 |

| Qatar | 15 |

| South Korea | 186b |

| Tunisia | 2 |

| United Arab Emirates | 77 |

| United Kingdom | 2 |

| Yemen | 1 |

| Missing | 5 |

| Total | 1,291 |

a Data were obtained from a publicly accessible line listing of cases maintained by Dr. Andrew Rambaut (12).

b Cases from South Korea were excluded from the current analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lloyd-Smith JO, George D, Pepin KM et al. . Epidemic dynamics at the human-animal interface. Science. 2009;3265958:1362–1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS). http://www.cdc.gov/CORONAVIRUS/MERS/ Updated December 2, 2015. Accessed August 7, 2015.

- 3.Zaki AM. Novel coronavirus—Saudi Arabia: human isolate. ProMED-mail 2012;15 Sept:20120920.1302733 www.promedmail.org/post/1302733 Published September 20, 2012. Accessed August 7, 2015.

- 4.Alagaili AN, Briese T, Mishra N et al. . Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection in dromedary camels in Saudi Arabia. MBio. 2014;52:e00884–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)—Saudi Arabia. http://www.who.int/csr/don/18-august-2015-mers-saudi-arabia/en/ Published August 18, 2015. Accessed August 18, 2015.

- 6.European Centers for Disease Control. Severe Respiratory Disease Associated With Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV). http://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/RRA-Middle-East-respiratory-syndrome-coronavirus-update10.pdf Published May 31, 2014. Accessed August 7, 2015.

- 7.Al-Abdallat MM, Payne DC, Alqasrawi S et al. . Hospital-associated outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: a serologic, epidemiologic, and clinical description. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;599:1225–1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Assiri A, McGeer A, Perl TM et al. . Hospital outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. N Engl J Med. 2013;3695:407–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferguson NM, Van Kerkhove MD. Identification of MERS-CoV in dromedary camels. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;142:93–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reusken CBEM, Haagmans BL, Müller MA et al. . Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus neutralising serum antibodies in dromedary camels: a comparative serological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;1310:859–866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lau EHY, Zheng J, Tsang TK et al. . Accuracy of epidemiological inferences based on publicly available information: retrospective comparative analysis of line lists of human cases infected with influenza A(H7N9) in China. BMC Med. 2014;12:88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rambaut A. MERS-Cases. https://github.com/rambaut/MERS-Cases Published June 18, 2013. Updated July 22, 2015. Commit eddf6dcca14fc73d861a4b712e8a2afda8f5c97e. Accessed August 4, 2015.

- 13.Honaker J, King G. What to do about missing values in time-series cross-section data. Am J Pol Sci. 2010;542:561–581. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zou G. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;1597:702–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Honaker J, King G, Blackwell M. Amelia II: a program for missing data. J Stat Softw. 2011;457:1–47. [Google Scholar]