Abstract

Purpose

We sought to conduct a systematic literature review on follow-up of children with ocular surgical management (primarily childhood cataract) in developing countries. Second, we sought to determine the current practices regarding follow-up for clinical, optical, low vision, rehabilitation, and educational placement among children receiving surgical services at Child Eye Health Tertiary Facilities (CEHTF) in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and South Asia.

Methods

A systematic literature review was conducted. Separately, we conducted a cross-sectional study among CEHTF in SSA and South Asia (India, Nepal, and Bangladesh) to assess current capacities and practices related to follow-up and educational placement.

Results

The articles that met the systematic review eligibility criteria could be grouped into two areas: factors and strategies to improve post-operative follow-up and educational placement of children after surgery. Among the 106 CEHTF in SSA and South Asia, responses were provided by 75 CEHTF. Only 59% of CEHTF reported having a Childhood Blindness and Low Vision Coordinator; having a coordinator was associated with having appropriate follow-up mechanisms in place. Educational referral practices were associated with having a low-vision technician, having low-vision devices, and having donor support for these services.

Conclusions

The systematic literature review revealed evidence of poor follow-up after surgical interventions for cataract and other conditions, but also showed that follow-up could be improved significantly if specific strategies were adopted. Approaches to follow-up are generally inadequate at most facilities and there is little external support for follow-up. Findings suggest that funding and supporting a coordinator would assist in ensuring that good practices for follow-up (cell phone reminders, patient tracking, and reimbursement of transport) were followed.

Introduction

Increasing the global knowledge base for planning for childhood eye care services is a top priority in order for children with visual impairment to realize their full visual potential. The body of knowledge on programmatic approaches to paediatric eye care in developing countries has significantly increased in the past 10 years, and evidence suggests that, with the reduction in vitamin A deficiency and measles-related blindness, childhood cataract requires increased global attention.1

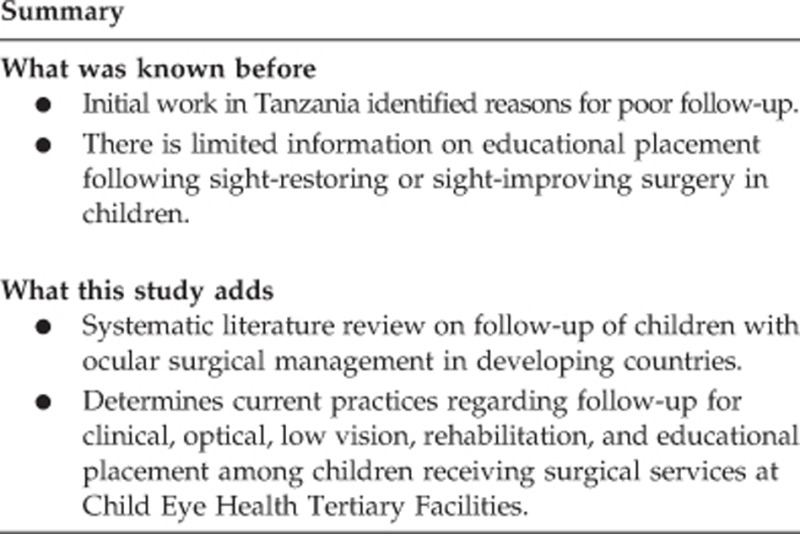

For many years, there has been considerable concern about the low levels of follow-up for distance corrections, optical low-vision devices, and educational placement for children receiving cataract and other ocular surgeries in many developing countries.2, 3 Initial work in Tanzania identified reasons for poor follow-up4 and demonstrated strategies to address these.5 There is limited information on educational placement following sight-restoring or sight-improving surgery in children6 and existing information suggests that there are considerable challenges in ensuring that children are placed in the most appropriate educational setting.7, 8 We sought to conduct a systematic literature review on follow-up of children with ocular surgical management (primarily childhood cataract) in developing countries. Second, we sought to determine the current practices regarding follow-up for clinical, optical, low vision, rehabilitation, and educational placement among children receiving surgical services at Child Eye Health Tertiary Facilities (CEHTF) in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and South Asia.

Materials and methods

A systematic literature review was conducted including a search in MEDLINE using the terms “Follow up strategies”, “childhood cataract surgery”, “phone follow up”, “text message”, “visual impairment”, and “school placement” for articles published in English language from 1 January 2001 to 30 June 2015. We also systematically searched the reference lists of included publications.

Separately, we conducted a cross-sectional study among CEHTF in SSA and South Asia (India, Nepal, and Bangladesh) to assess current capacities and practices related to follow-up. A list of CEHTF in SSA and South Asia was generated by our group with assistance for South Asia from ORBIS International and key personnel in the region. A questionnaire was designed and pretested with one facility; after this it was sent to the heads of CEHTF. The questionnaire included information on staffing, infrastructure, strategies used to improve follow-up, post-operative services provided, and educational placement practices (Supplementary Material). There were two open-ended questions on the survey, the first asking which children were least likely to return for follow-up and the second asking what the barriers to follow-up were. The questions, although related, reflect different perspectives on the same issue of poor follow-up after surgery. Responses to the questions were tallied by topic area. Respondents could provide multiple answers.

The study was approved by the University of Cape Town ethics committee and participants consented to use responses; all data were compiled and reported anonymously.

All CEHTF were contacted at least three times to obtain responses. Colleagues in Nigeria, Bangladesh, Nepal, India, and South Africa did follow-up contact with CEHTF who did not respond to the first two requests. Analysis was undertaken using Stata version 11.0 (College Station, TX, USA). Findings were reported as odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) and mean values.

Results

Literature review

The literature review identified 431 articles; 340 articles were not included after the first review as they did not include any information on follow-up. Among the remaining 91 articles, 25 met the eligibility criteria; all were reviewed and 17 provided information on one or more topics related to post-operative follow-up of children with cataract or other eye surgical conditions. The articles could be grouped into two areas: factors and strategies to improve post-operative follow-up and educational placement of children after surgery.

The first article that addressed the issue of post-operative follow-up was conducted in Tanzania4 and included an assessment of the pre-surgical factors that predicted whether children returned for their 2-week and 10-week follow-ups. On the basis of this work, a second paper5 demonstrated the effect of specific strategies to improve follow-up. Similar studies have been conducted in India,9 Mexico,10 China,11 and Nepal.12 The findings from these studies suggest a significant range in follow-up from 21% in India9 to 98% in Mexico,10 most however, being low. Factors associated with poor follow-up included long distance to the surgical facility,4, 9, 10 being a girl,4 long delay in presentation,4 and cost and poor understanding of the need for follow-up.9 Specific follow-up strategies (use of cell phone as reminders, reimbursing travel, maintaining a tracking sheet, and dedicated counselling) undertaken in Tanzania increased the proportion of children returning for their 10-week follow-up from 43 to 83% and gender inequity in follow-up disappeared.5 Undertaking a similar approach, a team in Nepal increased the proportion of children returning for post-operative services from 60 to 81%.12 Using a randomized trial approach, a team in China showed that SMS reminders were an effective approach to improve follow-up.11

There were only three papers, all from eastern Africa, that addressed educational placement after cataract surgery.6, 7, 8 There have been a number of surveys in schools for the blind that have noted the possibility of inappropriate educational placement,13, 14 but only one in which educational placement was the focus of the study.7 The findings from these studies suggested that, although children had significantly improved vision post-operatively, they were not often placed in the most appropriate educational environment.

Among the 106 CEHTF in SSA (n=46) and South Asia (n=60), responses were provided by 75 (71% of total questionnaires sent) CEHTF (39 in SSA and 36 in South Asia). The majority of the missing data were from India (23 of 42 CEHTF reported).

Staffing and facilities

The CEHTF have been providing services for a median 10 years, ranging from <1 to 48 years. All except four facilities reported having an optometrist and all except 11 facilities reported having a low-vision specialist. Only 44 facilities (58.7%) reported having a Childhood Blindness and Low Vision Coordinator.

Dedicated children's outpatient rooms were found at 54 (72%) facilities and dedicated paediatric operating theatres were found at 39 (52%) of facilities. Most CEHTF (67; 89.3%) had an optical shop and 52 facilities (69.3%) made spectacles in the optical shop. Low-vision rooms were found in 52 (69.3%) of CEHTF.

Follow-up activities undertaken

All facilities report counselling to improve follow-up. Counselling is done by a wide range of people: childhood blindness coordinators (25; 33.3%), eye nurses (26; 34.7%), optometrists (6; 8%), and other people (16; 21.3%). Only 29 facilities (38.7%) had a system for tracking children and 34 CEHTF (45.3%) used cell phones for follow-up; 22 facilities (29.3%) provided reimbursement for transport if needed. Only 20 facilities (26.7%) reported having donor support for follow-up.

Refractive services (including spectacles) for children were available at 68 (90.7%) CEHTF. In just over half of the cases (n=39; 52%), some of the costs for distance correction were covered by donors. In only three cases were some costs covered by government, and in 32 cases (42.7%), there was no mechanism to cover the costs. Availability of magnifying devices varied. High+spectacles were available at 64 facilities (85.3%); hand magnifiers at 62 facilities (82.7%); stand magnifiers at 52 facilities (69.3%); and telescopes at 48 facilities (64%). In half of the facilities, there were no mechanisms to support provision of low-vision devices (n=37; 49.3%), whereas 30 facilities (40%) had support from donors and 5 facilities (6.7%) reported support from the government.

Respondents reported that children living far away were the least likely to return for follow-up; this factor accounted for 53 (43.4%) of a total 122 responses (multiple responses allowed). Children from poor families (including poorly educated families) accounted for 17.2% of responses and older children accounted for 9.0% of responses. The most common barrier to follow-up reported included indirect costs (eg, transport to hospital, meals, and accommodation for parents) of follow-up; 62 (41.3%) of 150 reports (multiple responses allowed). This was followed by distance (25.3%) and lack of knowledge, or negligence by parents (26.0%). The ranking of responses to both questions was the same for CEHTF in Africa and South Asia.

Educational placement activities

For school-age children, educational placement is reported to be discussed with parents in 60 facilities (80%) and with teachers in 12 facilities (16%). Children have different educational needs and CEHTF would be expected to have similar referral patterns if all services were available, and CEHTF staff utilized the options appropriately. This was not the case as the CEHTF refer children to schools for the blind (n=57; 76%) and into mainstream schools (n=47; 62.7%) more frequently compared with annexes or resource centres (n=27; 36%). Some respondents (n=27; 36%) did not know if children at schools for the blind or annexes were examined prior to the enrolment. Only 23 CEHTF (30.7%) reported that children were assessed clinically prior to the enrolment; 25 CEHTF (33.3%) said that children were not examined prior to the enrolment. Most CEHTF (n=48; 64%) reported that there was an educational facility for children with other disabilities and 46 reported (61.3%) that there was a rehabilitation facility for children with other disabilities. There were significant differences between CEHTF in SSA and South Asia with South Asian CEHTF, generally more likely to have the staffing complement, facilities, strategies to improve follow-up, and follow-up services for children compared with the SSA CEHTF (Table 1).

Table 1. Comparison of findings from CEHTF in sub-Sahara Africa and South Asia.

| Sub-Saharan Africa | South Asia | Odds ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N=39 n (%) | N=36 n (%) | P-value | |

| Personnel | |||

| Optometrist | |||

| Present | 35 (92.1) | 36 (100) | Cannot calculate |

| Absent | 3 (7.9) | 0 | |

| Low-vision technician | |||

| Present | 31 (79.5) | 33 (94.3) | 0.23 (0.05–1.19) |

| Absent | 8 (20.5) | 2 (5.7) | P=0.06 |

| Childhood Blindness and Low Vision Coordinator | |||

| Present | 16 (41.0) | 28 (77.8) | 0.19 (0.07–0.54) |

| Absent | 23 (59.0) | 8 (22.2) | P=0.002 |

| Facilities | |||

| Years in operation | 8.9 (8.7) | 15.0 (9.9) | P=0.006 |

| Child outpatient room | |||

| Present | 18 (46.2) | 36 (100) | Cannot calculate |

| Absent | 21 (53.8) | 0 | |

| Paediatric operating theatre | |||

| Present | 13 (33.3) | 26 (72.2) | 0.19 (0.07–0.51) |

| Absent | 26 (66.7) | 10 (27.8) | P=0.001 |

| Optical shop | |||

| Making spectacles | 23 (59.0) | 29 (80.6) | 0.35 (0.12–0.98) |

| Not making specs | 8 (20.5) | 7 (19.4) | P=0.04 |

| No optical shop | 8 (20.5) | 0 | |

| Low-vision room | |||

| Present | 19 (51.4) | 33 (91.7) | 0.09 (0.02–0.37) |

| Absent | 18 (48.6) | 3 (8.3) | P=0.001 |

| Strategies to improve follow-up | |||

| Tracking | 7 (17.9) | 22 (61.1) | 0.14 (0.05–0.41) |

| No tracking | 32 (82.1) | 14 (38.9) | P=0.001 |

| Cell phone calls | 13 (33.3) | 21 (58.3) | 0.35 (0.14–0.91) |

| No cell phone calls | 26 (66.7) | 15 (41.7) | P=0.03 |

| Reimburse travel | 11 (28.2) | 11 (44.0) | 0.89 (0.33–2.41) |

| No reimbursement | 28 (71.8) | 25 (56.0) | P=0.83 |

| Donor support for follow-up | |||

| Present | 10 (25.6) | 10 (27.8) | 0.89 (0.32–2.49) |

| Absent | 29 (74.4) | 26 (72.2) | P=0.83 |

| Counselling done by: | |||

| Childhood coordinator | 11 (29.7) | 14 (38.9) | |

| Eye nurse | 17 (45.9) | 9 (25.0) | |

| Optometrist | 3 (8.1) | 3 (8.3) | |

| Other person | 6 (16.2) | 10 (27.8) | |

| Services provided at the CEHTF | |||

| Spectacles can be obtained | |||

| Yes | 32 (82.1) | 36 (100) | Cannot calculate |

| No | 7 (17.9) | 0 | |

| Costs for spectacles covered by: | |||

| Donor support | 12 (31.6) | 27 (75.0) | 0.17 (0.06–0.46) |

| Government | 2 (5.3) | 1 (2.8) | P=0.001 |

| No mechanism | 24 (63.1) | 8 (22.2) | |

| Low-vision devices can be obtained | |||

| High mag glasses | 31 (83.8) | 33 (97.1) | 0.16 (0.02–1.38) |

| No high mag glasses | 6 (16.2) | 1 (2.8) | P=0.06 |

| Hand magnifiers | 28 (73.7) | 34 (100) | Cannot calculate |

| No hand magnifiers | 10 (26.3) | 0 | |

| Stand magnifiers | 19 (61.3) | 33 (97.1) | 0.05 (0.00–0.40) |

| No stand magnifiers | 12 (38.7) | 1 (2.9) | P=0.001 |

| Telescopes | 18 (56.3) | 30 (91.7) | 0.13 (0.03–0.51) |

| No telescopes | 14 (43.7) | 3 (8.3) | P=0.001 |

| Cost of low-vision devices covered by: | |||

| Donor support | 14 (36.8) | 16 (47.1) | 0.46 (0.18–1.18) |

| Government support | 1 (2.7) | 4 (11.8) | P=0.10 |

| No mechanism | 23 (60.5) | 14 (41.1) | |

| Educational placement of children | |||

| Meet teacher | 4 (10.3) | 8 (22.2) | 0.40 (0.11–1.46) |

| Do not meet teacher | 35 (89.7) | 28 (77.8) | P=0.15 |

| Meet parent | 31 (79.5) | 29 (80.6) | 0.93 (0.30–2.90) |

| Do not meet parent | 8 (20.5) | 7 (19.4) | P=0.90 |

| Referral of school-age children to: | |||

| School for the blind | 33 (86.8) | 24 (66.7) | 3.3 (1.03–10.6) |

| Not school for blind | 5 (13.2) | 12 (33.3) | P=0.04 |

| Annex | 12 (31.6) | 15 (41.7) | 0.64 (0.25–1.67) |

| Not annex | 26 (68.4) | 21 (58.6) | P=0.37 |

| Mainstream school | 20 (52.6) | 27 (75.0) | 0.37 (0.14–0.99) |

| Not mainstream | 18 (47.4) | 9 (25.0) | P=0.04 |

| Are children assessed prior to enrolment? | |||

| Yes | 12 (30.8) | 11 (30.6) | 1.01 (0.38–2.70) |

| No | 15 (38.5) | 10 (27.8) | “no”+“don't know” |

| Don't know | 12 (30.8) | 15 (41.7) | Combined |

| Education facility for children with other disabilities | |||

| Present | 28 (73.7) | 20 (57.1) | 2.1 (0.78–5.62) |

| Absent | 10 (26.3) | 15 (42.9) | P=0.14 |

| Rehabilitation facility for children with other disabilities | |||

| Present | 26 (66.7) | 20 (55.6) | 1.60 (0.63–4.08) |

| Absent | 13 (33.3) | 16 (44.4) | P=0.33 |

Factors associated with good follow-up and referral for educational placement

In the earlier study of CEHTF in Africa,15 it was noted that predictors of productivity (number of children receiving surgery per year) were related to manpower, in particular, having a dedicated optometrist, low-vision technician, Childhood Blindness and Low Vision Coordinator (henceforth referred to as the “Coordinator”), and a dedicated anaesthetist. Having a Coordinator is still uncommon, particularly in SSA, yet CEHTF with a Coordinator are more likely to have strategies to improve follow-up, donor support, and plans for educational placement (Table 2). Having a low-vision technician was not associated with having any specific strategies to improve follow-up. Among the 75 institutions, 25 (33.3%) have support from donors (external or government) for both spectacles and low-vision devices, whereas 26 (34.7%) have no mechanism of support for either spectacles or low-vision devices. The remaining CEHTF have a mix of support or no support.

Table 2. Association between having a Childhood Blindness and Low Vision Coordinator, and likelihood of adopting different strategies to improve follow-up.

| Has CBLVC | No CBLVC | Odds ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| P-value | |||

| Tracking | |||

| Present | 24 (54.5) | 5 (16.1) | 6.24 (2.02–19.24) |

| Absent | 20 (45.5) | 26 (83.9) | P=0.001 |

| Cell phone | |||

| Present | 26 (59.1) | 8 (25.8) | 4.15 (1.52–11.33) |

| Absent | 18 (40.9) | 23 (74.2) | P=0.004 |

| Reimbursement for travel | |||

| Present | 20 (45.5) | 2 (6.5) | 12.08 (2.56–56.98) |

| Absent | 24 (54.5) | 29 (93.5) | P=0.001 |

| Donor support for follow-up | |||

| Present | 17 (38.6) | 3 (9.7) | 5.88 (1.54–22.36) |

| Absent | 27 (61.4) | 28 (90.3) | P=0.005 |

| Educational placement of children | |||

| Meet teachers | |||

| Yes | 11 (25.0) | 1 (3.2) | 10.0 (1.22–82.15) |

| No | 33 (75.0) | 30 (96.8) | P=0.01 |

| Meet parents | |||

| Yes | 37 (84.1) | 23 (74.2) | 1.83 (0.59–5.75) |

| No | 7 (15.9) | 8 (25.8) | P=0.29 |

| Refer to schools to the blind | |||

| Yes | 31 (70.5) | 26 (83.9) | 0.37 (0.11–1.26) |

| No | 13 (29.5) | 4 (16.1) | P=0.10 |

| Refer to annexes | |||

| Yes | 19 (43.2) | 8 (26.7) | 2.09 (0.76–5.71) |

| No | 25 (56.8) | 22 (73.3) | P=0.15 |

| Refer to mainstream schools | |||

| Yes | 31 (70.5) | 16 (53.3) | 2.09 (0.79–5.49) |

| No | 13 (29.5) | 14 (46.7) | P=0.14 |

| Children at schools for the blind assessed before enrolment | |||

| Yes | 15 (34.1) | 8 (25.8) | 1.49 (0.54–4.11) |

| No | 18 (40.9) | 7 (22.6) | “no”+“don't know” |

| Don't know | 11 (25.0) | 16 (51.6) | Combined |

| Educational referral possible for other disabilities | |||

| Yes | 26 (59.1) | 22 (71.0) | 0.66 (0.25–1.79) |

| No | 16 (40.9) | 9 (29.0) | P=0.41 |

| Rehabilitation referral possible for other disabilities | |||

| Yes | 27 (61.4) | 19 (61.3) | 1.0 (0.39–2.58) |

| No | 17 (38.6) | 12 (38.7) | P=0.90 |

Analysis of the factors associated with referral to mainstream schools and schools for the blind, and/or annexes was undertaken. Although referral patterns would be expected to match the needs of children, of the 47 CEHTF that referred to mainstream schools, 40 (85.1%) also referred to schools for the blind or annexes, whereas among the 27 CEHTF that did not refer to mainstream schools, 20 (74.1%) referred only to schools for the blind or annexes; seven CEHTF did not refer at all. If a CEHTF had a low-vision technician, it was 1.86 times (95% CI 0.48–7.14) more likely to refer children to the mainstream schools. More importantly, if a CEHTF provided low-vision devices (high+spectacles, hand magnifiers, stand magnifiers, and telescopes), it was more likely to refer to the mainstream schools (Table 3). Having donor or government support (as opposed to no support) for low-vision services was also associated with likelihood of referral to the mainstream schools, more so in South Asia than SSA (Table 3).

Table 3. Association between providing low-vision devices and referring to mainstream schools.

|

Refer children to mainstream schools |

Odds ratio (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | P-value | |

| Provide high+(magnifying) spectacles | |||

| Yes | 43 (95.6) | 20 (80.0) | 5.37 (0.96–30.12) |

| No | 2 (4.4) | 5 (20.0) | P=0.04 |

| Provide hand magnifiers | |||

| Yes | 43 (95.6) | 18 (69.2) | 9.56 (1.85–49.47) |

| No | 2 (4.4) | 8 (30.8) | P=0.002 |

| Provide stand magnifiers | |||

| Yes | 35 (89.7) | 16 (64.0) | 4.92 (1.32–18.39) |

| No | 4 (10.3) | 9 (36.0) | P=0.013 |

| Provide telescopes | |||

| Yes | 35 (85.4) | 12 (52.2) | 5.35 (1.62–17.60) |

| No | 6 (16.4) | 11 (47.8) | P=0.004 |

| Donor/government support available for low-vision services (all CEHTF) | |||

| Yes | 28 (62.2) | 6 (23.1) | 5.49 (1.84–16.39) |

| No | 17 (37.8) | 20 (79.9) | P=0.001 |

| Donor/government support available for low-vision services (South Asia CEHTF) | |||

| Yes | 18 (81.8) | 2 (22.2) | 15.75 (2.35–106.23) |

| No | 4 (18.2) | 7 (77.8) | P=0.002 |

| Donor/government support available for low-vision services (African CEHTF) | |||

| Yes | 10 (50.0) | 4 (23.5) | 3.25 (0.78–13.48) |

| No | 10 (50.0) | 13 (76.5) | P=0.10 |

Discussion

The systematic literature review revealed evidence of poor follow-up after surgical interventions for cataract and other conditions, but also showed that follow-up could be improved significantly if specific strategies (cell phone contact, reimbursing transport, maintaining tracking sheets, and dedicated counselling) were adopted. These strategies require both funding and manpower, generally in the form of a Coordinator.

The coverage of the CEHTF survey was fairly good (87% of African facilities, 58% of South Asian facilities); however, we cannot provide information on how different or similar the responding facilities were from the non-responding facilities.

Compared with the previous survey of CEHTF in SSA,15 the current assessment demonstrates that the staffing complement and infrastructure has improved greatly in the past 6 years. That said, the staffing and infrastructure findings from the SSA CEHTF were not as supportive of good-quality child eye health services as compared with the South Asian CEHTF. We cannot explain the differences except to note that South Asian CEHTF have, by and large, been established longer and have greater donor support for services provided at follow-up.

Similar to the previous work by Agarawal and colleagues,15 having a Coordinator is associated with having effective follow-up mechanisms such as having a tracking register, using cell phone contact for follow-up, and providing reimbursement for travel. There are costs associated with hiring and training a Coordinator, and as noted in our study, CEHTF with a Coordinator are 5.9 times more likely to have donor support.

Approaches to follow-up are generally inadequate at most facilities and there is little external support for follow-up. The most common follow-up approach was cell phone contact, (still less than half of facilities), followed by tracking (about one-third) and reimbursement. Approaches to follow-up were weakest in Africa even though there is little difference in donor support between SSA and South Asia. Distances and the indirect costs associated with returning for follow-up remain the main challenges reported by the personnel within CEHTF; this suggests that more proactive efforts at providing support for transport are needed.

Most facilities offered spectacles for children and most also had low-vision devices, although in only about half of the facilities were there mechanisms to support provision of spectacles or low-vision devices for children, particularly in SSA.

Most facilities reported discussing educational placement with parents, but few also discussed it with teachers; referral to mainstream schools without involving the classroom teachers is less likely to lead to successful educational placement.

Referring children with low vision to mainstream school environments, although preferable, may not be possible in all settings, particularly where there are no supportive mechanisms for these children. Nevertheless, the fact that 52% of CEHTF and 75% of CEHTF in SSA and South Asia, respectively, refer children to the mainstream schools, indicates that educational attainment opportunities for these children are growing. Most CEHTF reported minimal contact with schools for the blind, as less than one-third of CEHTF knew if children were screened prior to admission to these schools. In the end, providing both the low-vision services and the educational environment will be critical to ensure that children attain the best possible visual and educational outcomes.

Our findings, although limited by the responses received by the CEHTF, particularly those in India, provide valuable insights into how follow-up management is being currently provided in SSA and South Asia. There is considerable scope for improvement of service delivery; this will require investment by government and donors. Given the significant cost16 associated with surgical interventions, the effort to obtain good-quality follow-up is minimal.17, 18, 19

Acknowledgments

This manuscript has been made possible by the support of the American people. We are grateful for the assistance of colleagues in SSA and South Asia, who helped to get the questionnaires completed.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Material accompanies this paper on Eye website (http://www.nature.com/eye)

Supplementary Material

References

- Gogate P, Kalua K, Courtright P. Blindness in childhood in developing countries: time for a reassessment? PLoS Med 2009; 6(12): e1000177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhart PD, Courtright P, Wilson ME, Lewallen S, Taylor D, Ventura MC et al. Global challenges in the management of congenital cataract: Proceedings of the International Congenital Cataract Symposium held on March 7, 2014 New York City, New York. J AAPOS 2015; 19(2): e1–e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert C, Foster A. Childhood blindness in the context of VISION 2020-the right to sight. Bull World Health Organ 2001; 79: 227–232. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen JR, Bronsard A, Mosha M, Carmichael D, Hall AB, Courtright P. Predictors of poor follow up in children that had cataract surgery. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2006; 13: 237–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishiki E, Shirima S, Lewallen S, Courtright P. Improving post-operative follow up of children receiving surgery for congenital or developmental cataract in Africa. J AAPOS 2009; 13: 280–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosha M, Courtright P. Change in educational opportunities for children who have had cataract surgery in Tanzania. Vis Impair Res 2008; 10: 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Tumwesigye C, Msukwa G, Njuguna M, Shilio B, Courtright P, Lewallen S. Inappropriate enrollment of children in schools for the visually impaired in east Africa. Ann Trop Paediatr 2009; 29(2):135–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Msukwa G, Njuguna M, Tumwesigye C, Shilio B, Courtright P, Lewallen S. Cataract in children attending schools for the blind and resource centers in eastern Africa. Ophthalmology 2009; 116: 1009–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogate P, Patil S, Kulkarni A, Mahadik A, Tamboli R, Mane R et al. Barriers to follow-up for pediatric cataract surgery in Maharashtra, India: how regular follow-up is important for good outcome. The Miraj Pediatric Cataract Study II. Indian J Ophthalmol 2014; 62(3): 327–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Congdon NG, Ruiz S, Suzuki M, Herrera V. Determinants of pediatric cataract program outcomes and follow-up in a large series in Mexico. J Cataract Refract Surg 2007; 1775–1780. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lin H, Chen W, Luo L, Congdon N, Zhang X, Zhong X et al. Effectiveness of a short message reminder in increasing compliance with pediatric cataract treatment: a randomized trial. Ophthalmology 2012; 119: 2463–2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai SKC, Thapa H, Kandel RP, Ishaq M, Bassett K. Clinical and cost impact of a pediatric cataract follow-up program in western Nepal and adjacent northern Indian states. J AAPOS 2014; 18(1): 67–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaphley D, Marasini S, Kalua K, Naidoo KS. Visual profile of students in integrated schools in Malawi. Clin Exp Optom 2015; 98(4): 370–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnyawali S, Shrestha JB, Bhattarai D, Upadhyay M. Optical needs of students with low vision in integrated schools of Nepal. Optom Vis Sci 2012; 89(12): 1752–1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal PK, Bowman R, Courtright P. Child eye health tertiary facilities in Africa. J AAPOS 2010; 14: 263–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans CT, Lenhart PD, Lin D, Yang Z, Daya T, Kim YM et al. A cost analysis of paediatric cataract surgery at two child eye health tertiary facilities in Africa. J AAPOS 2014; 18: 559–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Congdon G, Yan X, Lansingh V, Sisay A, Müller A, Chan V et al. Assessment of cataract surgical outcomes in settings where follow-up is poor: PRECOG, a multicentre observational study. Lancet Glob Health 2013; 1: e37–e45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H, Wu X. Intervention strategies for improving patient adherence to follow-up in the era of mobile information technology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2014; 8: 104–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pop-Eleches C, Thirumurthy H, Habyarimana JP, Zivin JG, Goldstein MP, de Walque D et al. Mobile phone technologies improve adherence to antiretroviral treatment in a resource-limited setting: a randomized controlled trial of text message reminders. AIDS 2011; 25(6): 825–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.