Abstract

Determining the structures of nanoparticles at atomic resolution is vital to understand their structure–property correlations. Large metal nanoparticles with core diameter beyond 2 nm have, to date, eluded characterization by single-crystal X-ray analysis. Here we report the chemical syntheses and structures of two giant thiolated Ag nanoparticles containing 136 and 374 Ag atoms (that is, up to 3 nm core diameter). As the largest thiolated metal nanoparticles crystallographically determined so far, these Ag nanoparticles enter the truly metallic regime with the emergence of surface plasmon resonance. As miniatures of fivefold twinned nanostructures, these structures demonstrate a subtle distortion within fivefold twinned nanostructures of face-centred cubic metals. The Ag nanoparticles reported in this work serve as excellent models to understand the detailed structure distortion within twinned metal nanostructures and also how silver nanoparticles can span from the molecular to the metallic regime.

The structure of nanoparticles strongly influences their properties. Here, the authors use single crystal X-ray diffraction to resolve the crystal structures of Ag136 and Ag374 nanoparticles, enabling the observation of local structure distortion and the lower size limit of surface plasmon resonance.

The structure of nanoparticles strongly influences their properties. Here, the authors use single crystal X-ray diffraction to resolve the crystal structures of Ag136 and Ag374 nanoparticles, enabling the observation of local structure distortion and the lower size limit of surface plasmon resonance.

Owing to quantum-size and surface effects, nanoparticles frequently exhibit novel physical and chemical properties, which differ from their bulk counterparts in dramatic ways, and they have been gaining increasing attention in the fundamental and applied sciences1,2,3,4,5,6,7. Properties of nanoparticles are governed by chemical composition, size, shape and the overall molecular structure1,2. Despite significant progress in the chemical fabrication of uniform functional nanoparticles with well-defined shapes, sizes and compositions over the past two decades8,9,10,11, it is still notoriously difficult to manipulate their structures and thus functions with molecular control. Currently, there is the lack of effective tools to characterize the detailed structures (for instance, defects, twinning and surface features) of functional nanoparticles at atomic resolution. Without a detailed molecular structure as a guide, precision synthesis of nanoparticles with targeted functionality is difficult.

During the last several years, two major strategies have been applied in pursuit of detailed structure analysis of metal nanoparticles. One is application of state-of-the-art electron microscopy techniques to probe the atomic-resolution structures of the nanoparticle core12,13,14,15,16,17. Azubel et al.16 have reported the structure determination of a ligand-stabilized Au68 nanoparticle at atomic resolution by a combination of a low-dose approach and aberration-corrected transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The other avenue is to prepare and crystallize monodisperse metal nanoparticles into single crystals and determine their structures using X-ray diffraction18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31. Such an approach is particularly important to resolve the metal-ligand interfacial features at the metal nanoparticle surface. By this approach, the structures of a few ligand-stabilized (for instance, carbon monoxide and thiolate) metal nanoparticles containing over 100 metal atoms (for instance, Au102, Au133 and Au130) have been determined at or near atomic resolution18,19,20,21,32. Despite significant progress following both strategies, resolution of the molecular structure of metal nanoparticles containing several hundred metal atoms and having metallic properties remains daunting20,33.

We report here the syntheses and structure determinations of two giant, thiolated Ag nanoparticles containing 136 and 374 Ag atoms. As the largest thiolated metal nanoparticles crystallographically determined so far, these Ag nanoparticles exhibit unprecedented metallic properties with the emergence of surface plasmon resonance (SPR). The nanoparticles are miniatures of two closely related fivefold twinned nanostructures, pentagonal-bipyramidal (that is, decahedral) nanoparticles and twinned nanorods/nanowires derived from decahedral particles by elongation along the fivefold axis. Small distortions from the structure archetype within the fivefold twinned nanostructures are observed. Density functional theory (DFT) studies reveal that the smaller nanoparticle has molecular character with a small but distinct energy gap (band gap) between occupied and unoccupied orbitals (highest occupied molecular orbital–lowest unoccupied molecular orbital gap), whereas the larger one is fully metallic without a band gap. This leads to emergence of the surface plasmon incorporating contributions from the organic ligand layer. These two structurally determined systems represent important exemplars of the cross-over of Ag nanoparticles from the molecular to the metallic regime.

Results

Syntheses and TEM characterizations

The syntheses of thiolated Ag nanoparticles were achieved by chemical reduction of a polymeric silver 4-tert-butylbenzenethiolate precursor by NaBH4 in the presence of PPh4Br and triethylamine (see Methods for full details). The resulting Ag nanoparticles were first characterized by TEM as shown in Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1. The TEM images revealed that these thiolated Ag nanoparticles had a tight particle-size distribution at ∼2 nm. Thiolated Ag nanoparticles of larger, likewise uniform size, at ∼3 nm (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 2) were prepared in a similar manner, by increasing the Ag:SR (thiolate) molar ratio to 1.4:1.

Figure 1. Electron micrographs of thiolated Ag nanoparticles.

Scanning TEM and high-resolution TEM (inset) images of the as-prepared small (a) and large (b) 4-tert-butylbenzenethiolate-stabilized Ag nanoparticles. Scale bars, 2 nm.

Two important features are associated with these thiolated Ag nanoparticles. First, their sizes lie in the region where metallic Ag nanoparticles are said to develop SPR34 and thus provide scope to assess the occurrence of SPR from the viewpoint of associated quantum mechanical calculations. Second, the small and large Ag nanoparticles are verified as fivefold twinned nanocrystals as initially revealed by high-resolution TEM analysis (insets in Fig. 1 and Supplementary Figs 3 and 4). Fivefold twinning is a common phenomenon for nanoparticles of face-centred cubic (fcc) metals9. Competing models for the internal structure of fivefold twinned nanoparticles have been debated in the literature35,36. Resolving these atomic scale structures now demonstrates at the molecular level how the lattice mismatches are readily resolved within real fivefold twinned nanoparticles.

Molecular structures from single-crystal X-ray diffraction

Encouraged by the uniform size of both the small and large thiolated Ag nanoparticles, crystallization of these compounds was undertaken. High-quality black prism crystals of small nanoparticles and block crystals of large nanoparticles that were suitable for X-ray analysis were obtained by diffusion of hexane into their dichloromethane solutions (Supplementary Fig. 5). The fivefold twinned feature of both small and large silver nanoparticles was indeed revealed by detailed single crystal X-ray diffraction studies (for 1.2 Å resolution data in each case; Supplementary Data 1 and 2). Initial structure solutions were acquired by means of SHELXL37 and model refinements combined techniques of macromolecular crystallography with those more typical of chemical crystallography (Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2).38,39,40,41,42 As shown in Fig. 2, the small nanoparticle has a composition modelled as [Ag136(SR)64Cl3Ag0.45]− (denoted as Ag136) with the apparent mono-anionic charge balanced by a well-resolved PPh4+ and one entire nanoparticle plus cation pair forming the asymmetric unit. The larger nanoparticle has a composition modelled as [Ag374(SR)113Br2Cl2] (denoted as Ag374) with one half molecule lying on a crystallographic twofold axis comprising the asymmetric unit (Supplementary Figs 6 and 7). SR in both cases is 4-tert-butylthiophenolate. The presence of Cl in Ag136, and both Cl and Br in Ag374 were confirmed by temperature-programmed decomposition/mass-spectrometric and electrospray ionization mass-spectrometric data (Supplementary Fig. 8). Ag136 and Ag374 represent the largest thiolated metal nanoparticles with molecular structures determined by single-crystal X-ray analysis. They bear no structural relationship to a previously reported series of thiolated AgxSy particles containing up to 490 Ag atoms, derived from bulk Ag2S semiconducting materials43,44.

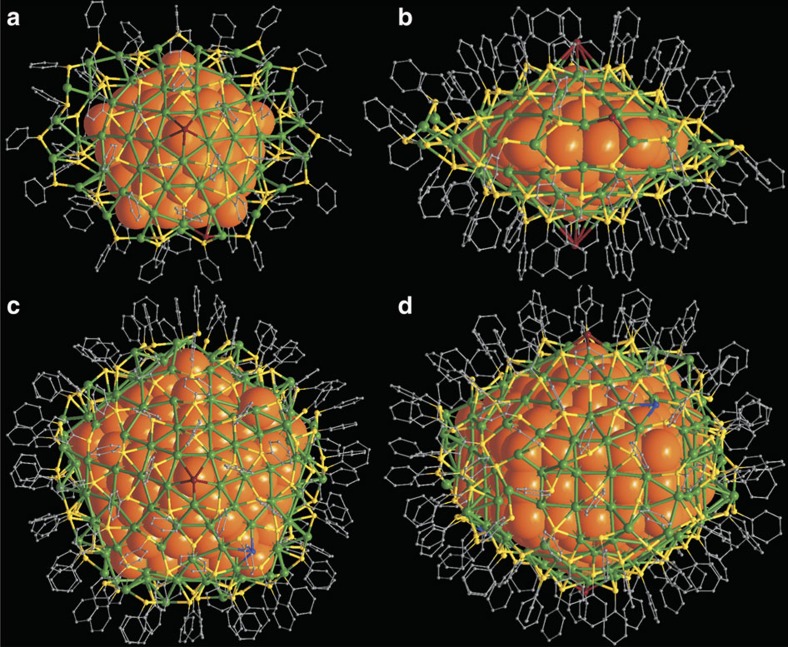

Figure 2. The overall structures of Ag136 and Ag374 nanoparticles.

(a,b) Top and side views of [Ag136(SR)64Cl3Ag0.45]−. (c,d) Top and side views of [Ag374(SR)113Br2Cl2]. Colour legend: orange, core Ag; green, surface Ag; yellow, S; brown, halogen; blue, Cl; grey, C. All hydrogen atoms and tert-butyl groups are omitted for clarity.

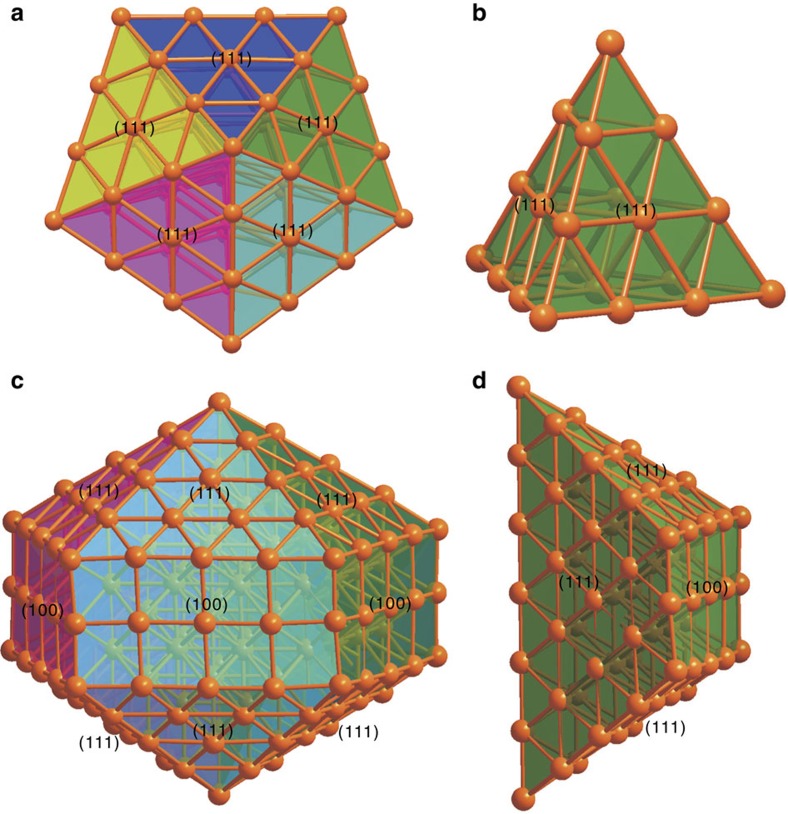

Both Ag136 and Ag374 can be structurally described as a fivefold twinned core enclosed within related structurally distinctive Ag–SR complex shells (Fig. 2). While the fivefold twinned core in Ag136 is present as a pentagonal bipyramid of 54 Ag atoms, the core in Ag374 is an elongated pentagonal bipyramid (Ino's decahedron) consisting of 207 Ag atoms. The Ag54 core in Ag136 can be structurally described as five conjoined tetrahedral domains of fcc Ag (Fig. 3a), each of which consists of 20 Ag atoms (Fig. 3b) and having 4 external Ag {111} facets. Each tetrahedral subunit is joined to the adjacent tetrahedral subunits by sharing of common triangular faces. In comparison, the Ag207 core of Ag374 can be considered as a miniature fivefold twinned nanorod constructed from five conjoined single-crystalline wedge-shaped grains, which are related to the pentagonal-bipyramid by elongation of each constituent tetrahedron to a wedge along the molecular fivefold aspect (Fig. 3c). In each wedge-shaped grain, there are two (111) triangular faces at the apices, two (111) trapezoids with their long edge on the fivefold axis and one (100) rectangle forming each side (Fig. 3d). Overall, each nanorod has five (100) side surfaces parallel to the elongated direction and ten (111) surfaces at the apices of the rod. The 207 Ag atoms in the core are distributed about a central Ag atom successively surrounded by three elongated pentagonal bipyramids consisting of 12, 42 and 92 atoms, encircled by a ‘pentagonal cylinder' of 60 Ag atoms likewise centred about the fivefold axis of the nanorod (Supplementary Fig. 9). The metal distributions in the cores of both Ag136 and Ag374 are entirely distinct from that in Au133 whose structure was reported (after submission of this report) to have a 20-fold twinned icosahedral core20,21. It should be noted that fivefold twinned metal cores have also been previously observed in Au102 and Au130 clusters resolved by single-crystal X-ray analysis19,32 and Au309 characterized by aberration-corrected scanning TEM13.

Figure 3. The structure dissection of the fivefold twinned cores of Ag136 and Ag374 nanoparticles.

(a) Core of Ag136, consisting of five tetrahedral units (b). (c) Core of Ag374, consisting of five wedge-shaped units (d). Different colours are used to highlight the five different twinning domains of the cores.

Structural distortions inside fivefold twinned cores

In regular fcc metals, the idealized angle between two (111) faces is 70.53°. When joined together by sharing (111) faces along the fivefold axis, without distortion, five ideal single-crystalline grains in a fivefold twinned nanostructure can only subtend an angle of 352.65°, 7.35° short of closure (Supplementary Fig. 10)17,45. In a real fivefold twinned nanostructure, this solid-angle deficiency needs to be compensated by sufficiently adjusting the interatomic spacings, introduction of various defects such as dislocations and stacking faults, or by increased internal vibrations. Structural models with homogeneous or inhomogeneous strain (deviations from idealized values) have been proposed for small metal nanoparticles35,36. In the fivefold twinned cores of Ag136 and Ag374, the average Ag–Ag bond lengths are 2.870 and 2.882 Å, respectively, both slightly shorter than the Ag–Ag bond distance (2.889 Å) of bulk silver with Ag374 only marginally so.

Detailed review of the Ag–Ag bond lengths (Supplementary Fig. 11) demonstrates the presence of a distinctive distortion within the observed pentagonal bipyramidal Ag54 core, where an obvious anisotropy of these adjustments is clear. Although Ag–Ag distances (18 out of 23) parallel to the fivefold axis are shorter than the average Ag–Ag distance (2.870 Å), most Ag–Ag bonds (47 out of 50) perpendicular to the fivefold axis are longer than 2.870 Å. Such a distribution clearly suggests that the geometric non-ideality in the decahedral core is resolved via a modest compression along the fivefold axis and concomitant relaxation about the directions perpendicular to the fivefold axis. In other words, each tetrahedral grain in the fivefold twinned decahedral nanoparticle is slightly compressed along the molecular fivefold axis. In Ag136, the five relevant angles are 71.5, 71.7, 72.1, 72.3 and 72.5°, slightly expanded from the idealized 70.53° by 1°–2°. These small deviations eliminate the 7.35° deficiency. Geometrically, this slight anisotropy evidently minimizes the total potential energy of the silver core (Supplementary Figs 12–14). In contrast to the anisotropy observed in the Ag54 core, no obvious trends are seen in the Ag207 core. Small deviations from planarity (a slight bulging) at the twinning boundaries appears to be the only readily discernible compensation for the solid-angle deficiency of the fivefold twinned Ag207 core. Careful analysis reveals that the fivefold twinning boundary (111) faces in the Ag207 core are not strictly planar (Supplementary Fig. 15). Within each shared (111) face, some Ag atoms deviate from the plane of their coplanar Ag set by up to 0.20 Å.

Surface structures

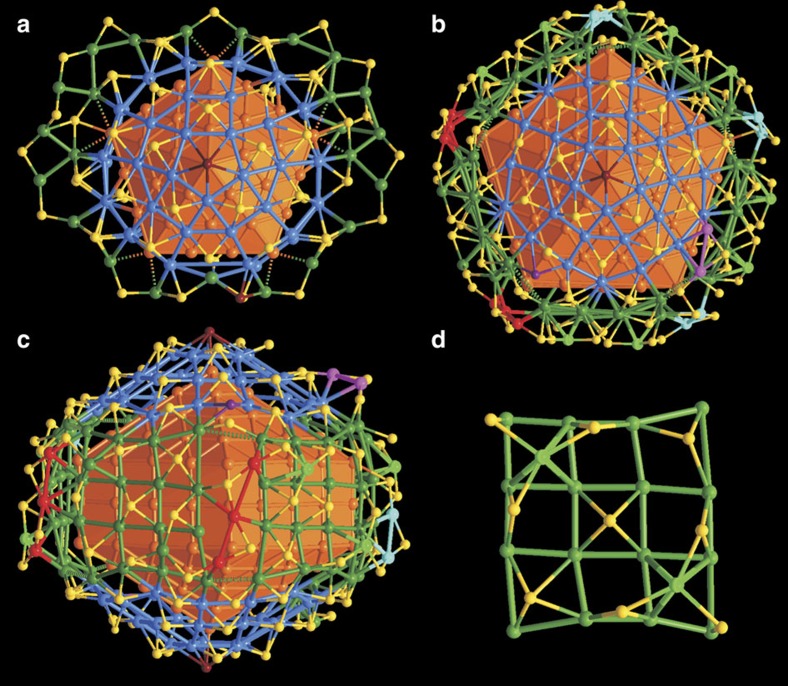

Based on TEM measurements, many studies have concluded that a decahedral nanoparticle should be bound by ten (111) facets and a fivefold twinned nanorod/nanowire of metals should have five (100) faces at its side and ten (111) faces, five at either end9. The X-ray studies of Ag136 and Ag374 validate this hypothesis for their Ag54 and Ag207 cores. However, the crystallographic studies reveal that the thiolate capped outermost Ag atoms deviate from the close-packed archetypes in a significant manner but with a marked congruence of the deviations from close packing observed in the two structures. In Ag136, the Ag54 core comprises two pentagonal pyramids, each of which is surmounted by a bowl-like [Ag30(SR)15Cl] unit (Fig. 4a). The silver atoms in [Ag30(SR)15Cl] describe one half of a parabigyrate rhombicosidodecahedron (Johnson solid J73—a circumscribable 60 vertex figure). These 30 silver atoms lie with their fivefold aspect disposed about the same fivefold axis as the Ag54 core and the opposing Ag30 unit lies in an eclipsed configuration about the fivefold core aspect. With each apical pentagon surmounted by a Cl− anion, each of the other distorted pentagonal Ag5 and tetragonal Ag4 faces is capped by a thiolate ligand. The equatorial pentagon of the Ag54 core is encircled by a Ag–SR complex ring. Four of the equatorial corners are spanned by one of four Ag2(SR)5 units and the remaining corner is spanned by one Ag2(SR)4Cl unit (against which the PPh4+ counterion rests). Detailed geometric analysis reveals that two significantly larger Ag–SR–Ag bond angles (135.8(4)° and 134.2(8)°) occur within these units than in the remainder (107.1(7)°, 108.5(3)° and 105.8(5)° for Ag2(SR)4Cl; Supplementary Fig. 16). Each of those with the larger Ag–SR–Ag bond angles is further spanned by Ag6(SR)5 units. These units connect via Ag and S to the units they span and bridge via their Ag termini between the two smaller angle Ag2(SR)5 and Ag2(SR)4Cl completing the outer AgS layer.

Figure 4. The surface structures of Ag136 and Ag374 nanoparticles.

(a) Top view of the complex shell of Ag136 with the bowl-like half J73 related [Ag30(SR)15Cl] caps highlighted in blue. (b,c) Top and side views of the complex shell of Ag374 with key structure elements highlighted in different colours. (d) Representative 4 × 4 arrangement of surface Ag atoms on (100) side surface of the Ag207 core. Colour legend: yellow sphere, S; brown sphere, halogen; the rest, Ag.

In a strikingly similar manner, the fivefold twinned Ag207 core of Ag374 is also fully encapsulated by a complex Ag-thiolate layer. As shown in Fig. 4b, each pentagonal pyramid is analogously capped by a bowl-like [Ag30(SR)15Br] of similar half J73 configuration with the apical pentagonal sites occupied by bromide. The five side (100) faces of the Ag207 core are each covered by five near planar Ag16 units. In each Ag16 unit, the silver atoms are arranged in somewhat irregular 4 × 4 patterns (Fig. 4c,d). The atoms in each Ag16 unit are face-capped by three SR and two Ag(SR)3 motifs (Supplementary Fig. 17). At the five pentagonal prismatic edges of the Ag207 core, the Ag16 units are joined together by three Ag3(SR)2, two Ag2(SR)2 motifs and four bridging SR, forming a drum-like layer surrounding the elongated pentagonal prismatic equatorial aspect of the core. This drum-like layer connects the two bowl-like [Ag30(SR)15Br] units via shared thiolates of the drum and a further two groups of Ag2(SR)2 motifs, and ten bridging SR and one Cl, which completes the closed complex shell having an overall composition of [Ag167(SR)113Cl2Br2] (Supplementary Fig. 18) surrounding the Ag207 core. For both Ag136 and Ag374, the Ag30 half-J73 domes lie with their apical pentagons eclipsed rather than staggered (as occurs in a complete 60 vertex J73 figure).

Electronic structures and optical properties

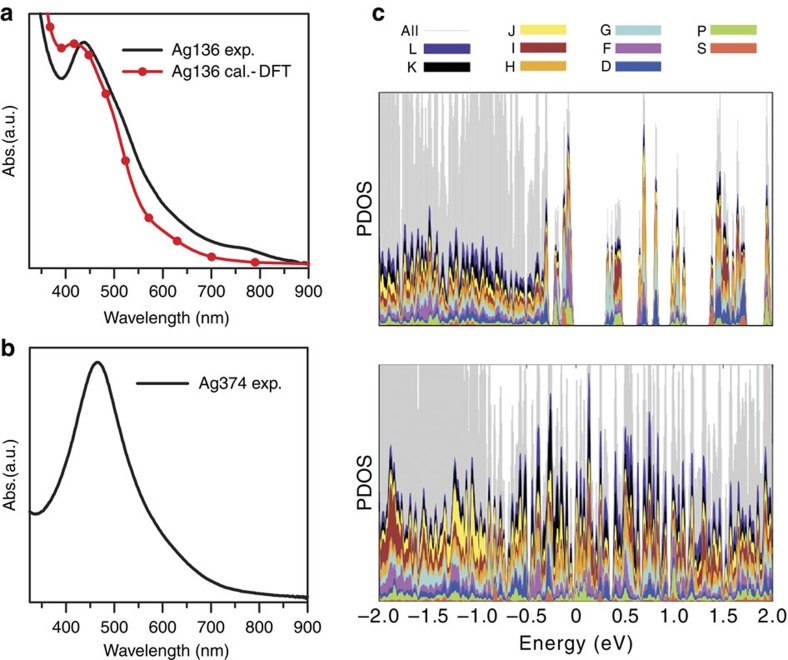

Both thiolated Ag136 and Ag374 nanoparticles are readily dissolved in solvents such as chloroform and dichloromethane, to give brown solutions. As shown in Fig. 5a,b, the smaller Ag136 nanoparticles display a broad major peak centred around 450 nm (2.75 eV) and a weak shoulder peak at 772 nm, whereas the larger Ag374 nanoparticles show only one strong peak at 465 nm (2.67 eV). The Ag374 absorption behaviour is distinct from the molecule-like multiband absorption features of previously reported thiolated Ag nanoclusters (for instance, Ag14, Ag16, Ag25, Ag32 and Ag44)22,23,46,47,48,49,50 and that of Ag136.

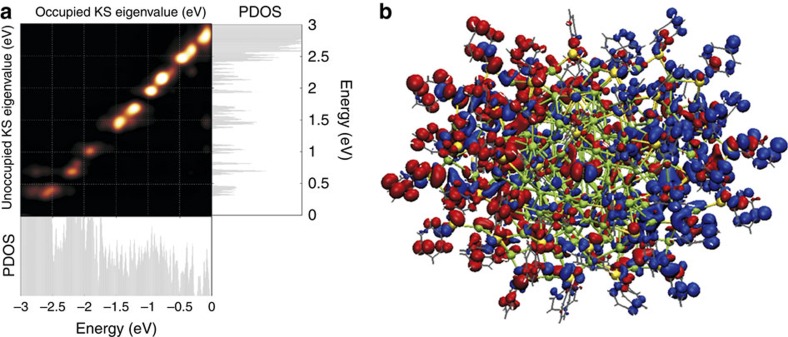

Figure 5. Optical properties and electronic structures of Ag136 and Ag374 nanoparticles.

(a,b) Ultraviolet–visible absorption spectra of (c) Ag136 (experimental and computed) and (b) Ag374 (experimental) nanoparticles. In the calculated spectra, the individual transitions are smoothed by using a Gaussian width of 0.1 eV. (c) Projection of the Kohn–Sham electron states (projected densities of electron states (PDOS)) of Ag136 (top) and Ag374 (bottom) to spherical harmonics centred at the metal core. The different spherical harmonics components (S, P, D,...) are indicated with colours as shown in the legend. The Fermi energy is at zero.

The electronic structures of Ag136 and Ag374 were probed via DFT computations, by using the simplified SPh ligand in place of SPh-tBu for Ag136 with a further simplification to SH for Ag374. The projected densities of electron states of the clusters are shown in Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 19. The calculated highest occupied molecular orbital–lowest unoccupied molecular orbital band gap for Ag136 is 0.37 eV, whereas the band gap is closed for Ag374. The calculated band gap and angular momentum characteristics of the frontier orbitals (Supplementary Fig. 20) place Ag136 as a molecular system, whereas the Ag374 can be characterized as metallic.

The optical absorption of the Ag136 cluster was studied by using linear-response (LR) time-dependent DFT calculations. The optical spectrum of the atomistic model for Ag136 agrees very well with the experimental data, having an overall similar shape in the ultraviolet–visible region and featuring a broad peak at 425 nm (2.9 eV; Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 21). Analysis of this peak (Fig. 6) shows that it is composed of several contributions including Ag(5s) to ligand, ligand to Ag(5s), ligand to ligand and Ag(4d) to Ag(5s) transitions. The total transition induced density shows a collective dipole oscillation localized across the interface of the metal core with the ligand layer. We interpret this as a plasmonic feature where the pi-electron density of the electron-rich ligand layer contributes to the collective oscillation. Based on this information, we interpret the experimental peak of Ag374 at 465 nm as of similar origin, where the slight red shift compared with the experimental peak of Ag136 is attributed to the much larger size of the system.

Figure 6. Analysis of the peak at 425 nm (2.9 eV) in the time-dependent DFT (TDDFT) optical spectrum of Ag136.

(a) The transition contribution map shown on the top left reveals that this peak consists of a large number of single-electron particle-hole transitions. Holes are created for states from the Fermi level down to about −2.5 eV (horizontal projected densities of electron states (PDOS) plot) and particles are created for states from the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) state up to ∼2.9 eV (vertical PDOS plot). In that energy range, both silver core states and ligand (sulfur and the pi-system of the phenyl) states are active and the total transition is a mixture of Ag(5 s) to ligand, ligand to Ag(5 s), ligand to ligand and Ag(4d) to Ag(5 s) contributions. (b) The induced transition density shows the collective dipole oscillation. Blue and red colours indicate mean deficit and surplus of electron density, respectively.

Discussion

This report demonstrates that it is feasible to deliberately and reproducibly synthesize metal nanoparticles with specific molecular products that readily enter the truly metallic regime with the emergence of SPR. As miniatures of fivefold twinned nanostructures of fcc metals, the success in resolving the total structures of Ag136 and Ag374 nanoparticles using single-crystal X-ray diffraction provides important models to visualize at the atomic scale the modest distortion from ideality inside fivefold twinned nanostructures of fcc metals and to describe their detailed surface structures. The Ag nanoparticles reported in this work have the lowest size for silver to display surface plasmonic properties reported to date. These structures serve as real models to understand how silver nanoparticles can span from the molecular to the metallic regime.

The observed plasmonic peaks of Ag136 and Ag374 are below the threshold energy of the well-known Mie plasmon of 3.5 eV for silver (dipolar bulk limit)51. In several gas phase, matrix isolation and surface studies in the past, atomic silver clusters from hundreds of atoms down to a few atoms exhibit resonance absorption at energies that are well over the Mie energy34,52. The fact that the thiol-stabilized Ag136 and Ag374 support an even lower bulk limit for the SPR, compared with the classical Mie energy for silver, is a manifestation of the important role played by the interfacial interactions between the thiolate layer and the nanoparticulate metal core. This clearly demonstrates that modifying the interface chemistry by introducing an organic passivating layer that has electronic properties distinct from thiolates could modify the plasmonic behaviour of ligand-stabilized silver nanoparticles. Changes in the interfacial chemistry may provide scope to vary the adjustments in the core and the interfacial structure as well, opening a range of chemical possibilities through which nanoparticle structures and electronic properties can potentially be modified.

Methods

Synthesis of the Ag-SPhtBu complex precursor

The complex precursor was prepared by following the reported procedure53. In a typical synthesis, 4-tBuPhSH (0.38 ml, 2.3 mmol) and NEt3 (0.32 ml, 2.3 mmol) were mixed together in 8 ml C2H5OH. The mixture was then added dropwise to a solution of AgNO3 (274 mg, 1.6 mmol) in 5 ml CH3CN under stirring. The mixture became a clear yellow solution on stirring overnight at room temperature under a nitrogen atmosphere. The yellow solution was dried under vacuum, to remove solvent yielding a yellow powder of the polymeric Ag-SPhtBu precursor, {(HNEt3)2[Ag10(SPhtBu)12]}n. This was stored in the dark under ambient conditions and used as the precursor for the syntheses of Ag136 and Ag374 nanoparticles.

Synthesis and crystallization of Ag136 nanoparticles

Thirty mlligrams of the Ag-SPhtBu precursor (containing 92 μmol Ag and 110 μmol SPhtBu− based on the formula of {(HNEt3)2[Ag10(SPhtBu)12]}n) were added to a mixed solvent of dichloromethane and methanol in a volume ratio of 4:1. The solution was cooled to 0 °C in an ice bath and 12 mg PPh4Br (29 μmol) was added to the solution. After 5 min stirring, 1 ml NaBH4 aqueous solution (45 mg ml−1, 1.2 mmol) and 50 μl triethylamine (360 μmol) were added quickly under vigorous stirring. The reaction was aged for 12 h at 0 °C. The aqueous phase was removed and the organic phase was washed several times with water. The solvent was then evaporated to give a dark solid. Black prism-like crystals were crystallized from CH2Cl2/hexane after 20 days at 4 °C. The synthesis of Ag136 with the substitution of Ph4PBr by an equivalent of Ph4PCl also results in Ag136.

Synthesis and crystallization of Ag374 nanoparticles

Thirty milligrams of the Ag-SPhtBu precursor were added to a mixed solvent of dichloromethane and methanol. Twelve milligrams of AgBF4 (62 μmol) and 12 mg PPh4Br (29 μmol) were added sequentially. After 5 min stirring, 1 ml NaBH4 aqueous solution (45 mg ml−1, 1.2 mmol) and 50 μl triethylamine (360 μmol) were added quickly under vigorous stirring. The reaction was aged for 4 h at room temperature. The aqueous phase was discarded and the mixture in organic phase was washed several times with water and evaporated to give a dark solid. Black block-like crystals were crystallized from CH2Cl2/hexane after 2 months at 4 °C.

X-ray single-crystal analysis

Diffraction data of the single crystals grown from the solutions of Ag136 and Ag374 nanoparticles were collected on an Agilent Technologies SuperNova system X-ray single-crystal diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ=1.54184 Å) at 100 K to a resolution of 1.2 Å. The data were reduced using CrysAlisPro. The structures were solved in ShelXL and refined using a combination of ShelXT, Olex2, Shelxle and CRYSTALS37,38,39,40,41,42. A customized refinement procedure employing techniques from both chemical crystallographic practice and macromolecular modelling methods (including contoured electron density mapping of all tBuPh groups) was evolved to address the challenges of each structure. In Ag136, a silver site of less than half occupancy has been modelled, which may be occupied in some molecules. The associated electron density refines well on this basis and the assignment makes chemical sense, noting that a sulfur atom with a high displacement parameter lies closer to this site than is reasonable. It is proposed that when this additional silver is present, the close sulfur atom lies in a site at the end of the sulfur ellipsoid furthest from the silver site. Significant ‘solvent voids' are noted and it is proposed that these regions are more properly termed ‘frozen solution' than solvent of crystallization in view of the very limited localized electron density features lying in the voids (note CH2Cl2 is the main solvent). The modest observed residual electron densities lie within the silver nanoparticles. No modifications to the data or refinement were made to account for these void volumes (see Supplementary Discussion and Supplementary Methods for further crystallographic details).

Computational method

The electronic structures of Ag136 and Ag374 were studied by DFT code GPAW, which implements projector-augmented wave method in a real-space grid54. The real space had a grid spacing of 0.2 A°. Ag(4d105s1), S(3s23p4), Br(4s24p5) and H(1s1) electrons were regarded as the valence, and the projector-augmented wave setups for Ag included scalar-relativistic corrections. Structures and total energies were evaluated at the gradient-corrected functional of Perdew, Burke and Ernzerhof (PBE) level55. It should be pointed out that the configurations for Ag136 and Ag374 used in the calculations were taken from our preliminary crystallographic model. This Ag136 model had a formula of [Ag136(SPhtBu)65Br2]− which had 70 metallic free electrons (from the superatom counting rules). The electron number was same as that for the dominant final refined structure [Ag136(SPh)64Cl3]−. The correction to the structural formula for Ag136 does not affect our conclusions concerning the electronic structure and optical properties. The preliminary crystallographic model for Ag374 had a formula of [Ag374(SR)115Br2] containing two more SR− groups than that of the final refined structure again. These two sites were ultimately modelled with Cl at the former S site, yielding the same electron count. The organic groups were replaced by SPh for Ag136, after which the organic layer was relaxed to an energy minimum, while keeping the Ag, S and Br atoms fixed to experimental positions. For Ag374, a simplified ligand SR=SH was used and the S–H bonds were relaxed, while keeping Ag, S and Br atoms fixed to their experimental positions. Angular momentum analysis of the Kohn–Sham orbitals was done as metal-core projected density of states as described earlier56.

The optical absorption spectrum of Ag136 was calculated with the PBE level using time-dependent DFT formalism in GPAW.57 The grid spacing was 0.8 Å. The electron density and wave functions were calculated by the local density approximation and the PBE functional was used for calculating LR optical absorption spectra. The transitions contributing to selected optical peaks were analysed using a recently developed method based on time-dependent density functional perturbation theory58.

Data availability

The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, under deposition number CCDC-1496141 (Ag374) and 1496142 (Ag136). These data can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. All other data are available from the authors on reasonable request.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Yang, H. et al. Plasmonic twinned silver nanoparticles with molecular precision. Nat. Commun. 7:12809 doi: 10.1038/ncomms12809 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1 - 21, Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, Supplementary Discussion, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References

Crystallographic information file for Ag374.

Crystallographic information file for Ag374.

Acknowledgments

N.F.Z acknowledges the financial support from the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2015CB932303), and the National Nature Science Foundation of China (21420102001, 21131005, 21390390, 21227001 and 21333008). H.H. acknowledges funding from the Academy of Finland (266492) and B.D. acknowledges funding from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft within DI 921/6-1. D.D.W. acknowledges the financial support from the National Nature Science Foundation of China (11222221 and 11472233) and the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province of China (2014J06001). The computational resources were provided by CSC–the Finnish IT Center for Science. We thank Professor L.S. Zheng for helpful discussions and Drs Z.E. Yan and F. White for assistance with crystal structure solution. Brian McMahon and Mike Hoyland of the IUCr Chester Office are thanked for their assistance in processing the CIFs accompanying this article.

Footnotes

Author contributions N.F.Z. designed the study, supervised the project and analysed data. Y.H.Y and Y.W. conceived and carried out experiments and analysed the data. H.Q.H. and J.Z.Y. assisted in the synthesis of Ag374. TEM studies were done by X.J.Z. and L.G. G.L., C.F.X. and Z.C.T. carried out temperature-programmed decomposition/mass-spectrometric measurements. The geometric distortion analysis was done by J.C.W. and D.D.W. Y.H.Y. conducted the experimental X-ray work structure solution and initial modelling, while A.J.E. and B.D. undertook the detailed crystallographic analysis. All computations and theoretical analyses were done by X.C., L.L. and H.H. All authors contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. H.Y.Y. and Y.W. equally contributed to this work.

References

- Alivisatos A. P. Semiconductor clusters, nanocrystals, and quantum dots. Science 271, 933–937 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Daniel M.-C. & Astruc D. Gold nanoparticles: assembly, supramolecular chemistry, quantum-size-related properties, and applications toward biology, catalysis, and nanotechnology. Chem. Rev. 104, 293–346 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volokitin Y. et al. Quantum-size effects in the thermodynamic properties of metallic nanoparticles. Nature 384, 621–623 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Collier C. P., Saykally R. J., Shiang J. J., Henrichs S. E. & Heath J. R. Reversible tuning of silver quantum dot monolayers through the metal-insulator transition. Science 277, 1978–1981 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Anker J. N. et al. Biosensing with plasmonic nanosensors. Nat. Mater. 7, 442–453 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai X. et al. Solution-processed, high-performance light-emitting diodes based on quantum dots. Nature 515, 96–99 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalet X. et al. Quantum dots for live cells, in vivo imaging, and diagnostics. Science 307, 538–544 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris D. J., Efros A. L. & Erwin S. C. Doped nanocrystals. Science 319, 1776–1779 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y., Xiong Y., Lim B. & Skrabalak S. E. Shape-controlled synthesis of metal nanocrystals: simple chemistry meets complex physics? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 60–103 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu L. & Peng X. Control of photoluminescence properties of CdSe nanocrystals in growth. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 2049–2055 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puntes V. F., Krishnan K. M. & Alivisatos A. P. Colloidal nanocrystal shape and size control: the case of cobalt. Science 291, 2115–2117 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott M. C. et al. Electron tomography at 2.4-angstrom resolution. Nature 483, 444–447 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z. Y. et al. Three-dimensional atomic-scale structure of size-selected gold nanoclusters. Nature 451, 46–48 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Aert S., Batenburg K. J., Rossell M. D., Erni R. & Van Tendeloo G. Three-dimensional atomic imaging of crystalline nanoparticles. Nature 470, 374–377 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. -C. et al. Three-dimensional imaging of dislocations in a nanoparticle at atomic resolution. Nature 496, 74–77 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azubel M. et al. Electron microscopy of gold nanoparticles at atomic resolution. Science 345, 909–912 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson C. L. et al. Effects of elastic anisotropy on strain distributions in decahedral gold nanoparticles. Nat. Mater. 7, 120–124 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran N. T., Powell D. R. & Dahl L. F. Nanosized Pd145(CO)x(PEt3)30 containing a capped three-shell 145-atom metal-core geometry of pseudo icosahedral symmetry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 39, 4121–4125 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadzinsky P. D., Calero G., Ackerson C. J., Bushnell D. A. & Kornberg R. D. Structure of a thiol monolayer-protected gold nanoparticle at 1.1Å resolution. Science 318, 430–433 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng C. et al. Structural patterns at all scales in a nonmetallic chiral Au133(SR)52 nanoparticle. Sci. Adv. 1, e1500045 (() (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dass A. et al. Au133(SPh-tBu)52 nanomolecules: x-ray crystallography, optical, electrochemical, and theoretical analysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 4610–4613 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H. Y. et al. All-thiol-stabilized Ag44 and Au12Ag32 nanoparticles with single-crystal structures. Nat. Commun. 4, 2422 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desireddy A. et al. Ultrastable silver nanoparticles. Nature 501, 399–402 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng C. et al. Total structure and electronic properties of the gold nanocrystal Au36(SR)24. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 13114–13118 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crasto D. et al. Au24(SAdm)16 nanomolecules: x-ray crystal structure, theoretical analysis, adaptability of adamantane ligands to form Au23(SAdm)16 and Au25(SAdm)16, and its relation to Au25(SR)18. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 14933–14940 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crasto D., Malola S., Brosofsky G., Dass A. & Häkkinen H. Single crystal XRD structure and theoretical analysis of the chiral Au30S(S-t-Bu)18 cluster. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 5000–5005 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das A. et al. Total structure and optical properties of a phosphine/thiolate-protected Au-24 nanocluster. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 20286–20289 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaven M. W., Dass A., White P. S., Holt K. M. & Murray R. W. Crystal structure of the gold nanoparticle [N(C8H17)4][Au25(SCH2CH2Ph)18]. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 3754–3755 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian H. F., Eckenhoff W. T., Zhu Y., Pintauer T. & Jin R. C. Total structure determination of thiolate-protected Au38 nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 8280–8281 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng C. J., Li T., Das A., Rosi N. L. & Jin R. C. Chiral structure of thiolate-protected 28-gold-atom nanocluster determined by X-ray crystallography. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 10011–10013 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu M. Z., Aikens C. M., Hollander F. J., Schatz G. C. & Jin R. Correlating the crystal structure of a thiol-protected Au25 cluster and optical properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 5883–5885 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. et al. Crystal structure of barrel-shaped chiral Au130(p-MBT)50 nanocluster. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 10076–10079 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian H., Zhu Y. & Jin R. Atomically precise gold nanocrystal molecules with surface plasmon resonance. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 696–700 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholl J. A., Koh A. L. & Dionne J. A. Quantum plasmon resonances of individual metallic nanoparticles. Nature 483, 421–427 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gryaznov V. G. et al. Pentagonal symmetry and disclinations in small particles. Cryst. Res. Technol. 34, 1091–1119 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Hofmeister H. Forty years study of fivefold twinned structures in small particles and thin films. Cryst. Res. Technol. 33, 3–25 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. A short history of SHELX. Acta Cryst. A 64, 112–122 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. SHELXT- Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Cryst. A 71, 3–8 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betteridge P. W., Carruthers J. R., Cooper R. I., Prout K. & Watkin D. J. CRYSTALS version 12: software for guided crystal structure analysis. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 36, 1487 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Cooper R. I., Gould R. O., Parsons S. & Watkin D. J. The derivation of non-merohedral twin laws during refinement by analysis of poorly fitting intensity data and the refinement of non-merohedrally twinned crystal structures in the program CRYSTALS. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 35, 168–174 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Dolomanov O. V., Bourhis L. J., Gildea R. J., Howard J. A. K. & Puschmann H. OLEX2: a complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 42, 339–341 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Huebschle C. B., Sheldrick G. M. & Dittrich B. ShelXle: a Qt graphical user interface for SHELXL. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 44, 1281–1284 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenske D. et al. Syntheses and crystal structures of [Ag123S35(StBu)50] and [Ag344S124(StBu)96]. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 5242–5246 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anson C. E. et al. Synthesis and crystal structures of the ligand-stabilized silver chalcogenide clusters [Ag154Se77(dppxy)18], [Ag320(StBu)60S130(dppp)12], [Ag352S128(StC5H11)96], and [Ag490S188(StC5H11)114]. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 1326–1331 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sau T. K. & Rogach A. L. Nonspherical noble metal nanoparticles: colloid-chemical synthesis and morphology control. Adv. Mater. 22, 1781–1804 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakr O. M. et al. Silver nanoparticles with broad multiband linear optical absorption. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 5921–5926 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H. Y. et al. Crystal structure of a luminescent thiolated Ag nanocluster with an octahedral Ag64+ core. Chem. Commun. 49, 300–302 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H. Y., Wang Y. & Zheng N. F. Stabilizing subnanometer Ag(0) nanoclusters by thiolate and diphosphine ligands and their crystal structures. Nanoscale 5, 2674–2677 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J. Z. et al. Total structure and electronic structure analysis of doped thiolated silver [MAg24(SR)18]2– (M=Pd, Pt) clusters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 11880–11883 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi C. P., Bootharaju M. S., Alhilaly M. J. & Bakr O. M. [Ag25(SR)18]−: the “golden” silver nanoparticle. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 11578–11581 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreibig U. & Vollmer M. Optical Properties of Metal Clusters Springer (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Haberland H. Looking from both sides. Nature 494, E1–E2 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang K., Xie X., Zhao L., Zhang Y. & Jin X. Synthesis and crystal structure of {[HNEt3]2n[Ag8Ag4/2(SC6H4tBu-4)12]n·nC2H5OH} and its reaction product with CS2. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2004, 78–85 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Enkovaara J. et al. Electronic structure calculations with GPAW: a real-space implementation of the projector augmented-wave method. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 22, 253202 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdew J. P., Burke K. & Ernzerhof M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter M. et al. A unified view of ligand-protected gold clusters as superatom complexes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 9157–9162 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter M. et al. Time-dependent density-functional theory in the projector augmented-wave method. J. Chem. Phys. 128, 244101 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malola S., Lehtovaara L., Enkovaara J. & Häkkinen H. Birth of the localized surface plasmon resonance in monolayer-protected gold nanoclusters. ACS Nano 7, 10263–10270 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1 - 21, Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, Supplementary Discussion, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References

Crystallographic information file for Ag374.

Crystallographic information file for Ag374.

Data Availability Statement

The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, under deposition number CCDC-1496141 (Ag374) and 1496142 (Ag136). These data can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. All other data are available from the authors on reasonable request.