Abstract

Objective. To investigate the correlation of mean admission multiple mini-interview (MMI) scores with cumulative and overall GPA across didactic years 1-3 in the doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) curriculum.

Methods. The mean admission MMI score and cumulative and overall GPA for first year (P1), second year (P2), and third year (P3) students in the PharmD curriculum was used to conduct a multiple regression analysis and to calculate a Pearson correlation coefficient. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS, v20.

Results. A negative correlation between mean admission MMI and overall GPA was observed for P1 students and P2 students. A significant positive correlation was observed between mean admission MMI and overall GPA for P3 students.

Conclusion. A weak association between mean admission MMI score and GPA was observed, and the direction of the association between MMI and GPA was mixed across cohorts of students in the PharmD curriculum. Further research is needed that includes measurement of noncognitive outcomes and continued validation of the MMI for use in pharmacy school admissions.

Keywords: multiple mini-interview, pharmacy admissions, grade point average

INTRODUCTION

The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) requires doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) programs to conduct standardized interviews of applicants to evaluate verbal and written communication skills, understanding of the pharmacy profession, and commitment to patient care.1 As the role of the pharmacist continues to advance beyond dispensing medications, the admissions process for pharmacy colleges and schools must attempt to assess not only cognitive measures such as undergraduate grade point average (GPA) and Pharmacy College Admissions Test (PCAT) scores as predictors of success as a pharmacist, but also noncognitive measures.

The University of South Florida College of Pharmacy (USFCOP) was established in 2009 and matriculated the first cohort of PharmD students in fall 2011. Students in the program complete three years of didactic study and one year of advanced experiential education. The college implemented a holistic approach to the admissions process using the multiple mini-interview (MMI) to aid in the assessment of noncognitive skills outside the realm of GPA and PCAT scores. The MMI was made popular through use in medical school admissions and has been validated to assess emotional intelligence, and ethical and moral decision making in medical school applicants.2

The MMI resembles an objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) with multiple stations that focus solely on assessing noncognitive characteristics. The interviewer is blinded to the applicant’s admission application, thereby reducing the possibility of bias. In 2001, the School of Medicine at McMaster University began developing the MMI with the intention of increasing the validity of the admissions interview process for noncognitive skills.

The usefulness of the MMI comes from its ability to overcome poor test-retest reliability and context specificity when measurements of a particular attribute in one context may not transfer to another.3 The MMI format reduces interviewer bias and buffers against marked shifts in scores when many scores are collected on the same candidate.3 Moreover, the MMI is a reliable assessment to measure a candidate’s abilities. When the number of stations in a MMI circuit is maximized, overall reliability is improved compared to increasing the number of interviewers at MMI stations.3,4 This may suggest that higher reliability is obtained through multiple encounters compared with standard interview formats, which typically include one or two interviewers and one interviewee in a single encounter.

According to the literature, a number of pharmacy schools in North America are replacing the traditional interview process with the MMI because of its validity and ability to assess emotional intelligence of applicants.5 In a doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) program, the psychometric properties of the MMI as an assessment tool have been demonstrated.6 However, to date only student/faculty perceptions, feasibility, and pilot testing of the MMI in the pharmacy school admissions process is described in the literature.7 It is well-documented that prepharmacy GPA, PCAT score, and the completion of a degree is correlated to success in pharmacy school.8 However, the investigations of the impact of MMI scores on GPA in PharmD programs is lacking. Thus, the aim of this study was to examine the association between MMI scores and GPA among PharmD students.

METHODS

The study used archival data from the Office of Assessment at the USFCOP and a convenience sample of all students in the first three cohorts at the college. Data were originally collected as part of admissions and academic progress monitoring. The raw data are stored in a longitudinal database with access restricted to college administration only. The study was approved by the USF Institutional Review Board, and all data were de-identified to protect student confidentiality. The MMI was first used for the PharmD program at the college for the entering class in fall 2011, and is still used in the admissions process. All PharmD students participated in the MMI as a requirement for admission and were graded by college of pharmacy faculty members serving as trained standardized interviewers.

Inclusion criteria were accepted pharmacy students with an MMI score and calculated GPA for each semester enrolled in the college. Students were excluded if an MMI score or GPA was not calculated for any semester. Students were also excluded if they were dismissed, withdrew, or were placed in a different graduating year. There was no predetermined MMI score that resulted in an admissions rejection or waitlist for an applicant.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria resulted in a convenience sample of 220 students [first-year (P1) n=105; second-year (P2) n=65; third-year (P3) n=50]. The data in the study contained two semesters of coursework for P1 students, four semesters of coursework for P2 students and six semesters of coursework for P3 students.

The independent variable for this study was MMI score, and the dependent variable was GPA. A multiple regression analysis was conducted to investigate the ability of the MMI to predict academic success as measured by GPA. The Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated to test for the strength of association between MMI scores and GPA, with a p value of <0.05. A correlation between MMI score and GPA for each cumulative academic year, in addition to an overall cumulative GPA for each cohort of students enrolled in the college, was investigated. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS, v20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Coefficients of 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5 or larger were corresponded to weak or small, moderate, and strong or large correlations, respectively.9

The MMI at USFCOP initially consisted of a 7-station circuit. Six of the seven stations assessed a specific characteristic. The seventh station allowed the interviewer to ask clarifying questions on behalf of the admissions committee, and interviewees were given an opportunity to ask questions and share additional information not found in their application. After year one of implementation, the number of stations was reduced to five to streamline the process. Specifically, evaluation of interpersonal skills was eliminated from the MMI circuit because this skill was also assessed during a group activity during the interview day at the college. The seventh station, which did not assess a specific characteristic, was also eliminated. Instead, if the committee had clarifying questions, they asked applicants prior to the interview. First-year and P2 students’ MMI scores were scored on a 24-point scale, in comparison to a 27-point scale for P3 students.

Characteristics assessed during the MMI included motivation for success, cultural awareness, self-directed learning, ethics/academic integrity, commitment to patient care, and knowledge of the profession. Each station was assigned a specific question and standardized rubric, with emotional maturity and communication skills assessed at all stations. All stations were assigned a raw score from the rubric with an additional average score calculated for each of emotional maturity and communication skills. Candidates earned a total MMI score that was the sum of station raw scores, average communication score, and average maturity score.

RESULTS

Six students were excluded from this analysis (three withdrew from the program and three joined a different graduating class because of a lapse in progression). Among these six students, the mean age at matriculation was 25 years old, overall mean incoming GPA was 3.39, and mean MMI score was 20.2. Three of these students were indicated as having interview concerns, four had a history of academic difficulty requiring meeting with the USFCOP academic and professionalism review committee, and three had a history of disciplinary issues requiring meeting with the committee.

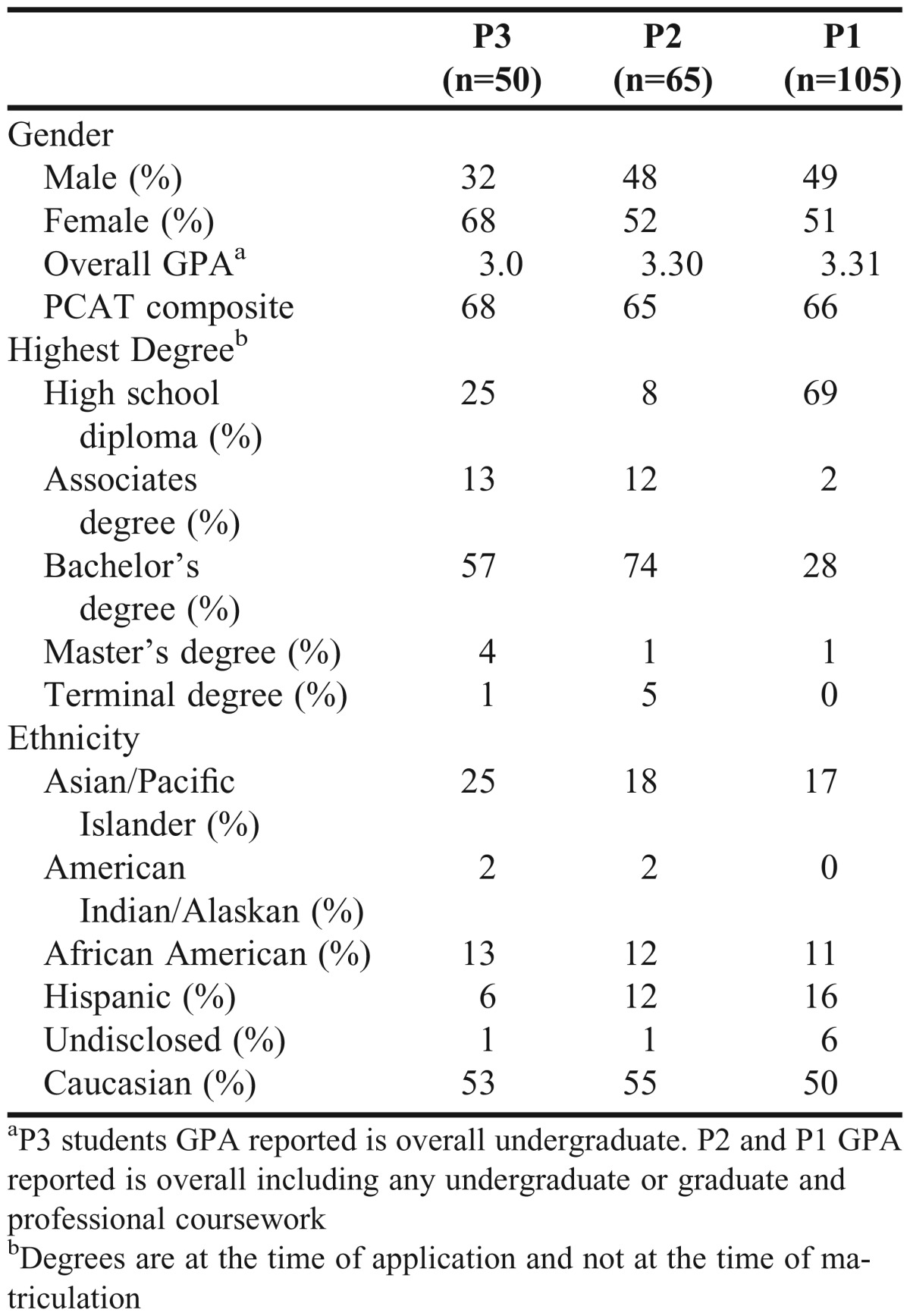

After exclusion criteria were applied, a sample size of 220 students remained. Preliminary analyses were performed to ensure no violation of the assumptions of normality, linearity, and homoscedasticity. Baseline data for each cohort of students is provided in Table 1 (n=220). When adjusting for the different MMI scoring system used for P3 students, mean MMI score was found to be similar at baseline. In each of the three student cohorts, females represented a larger proportion than males. Cognitive measures such as overall mean GPA and composite PCAT score at baseline differed only slightly among each cohort. However, only 29% of P1 students held a bachelor, master, or terminal degree compared with 80% of P2 students and 62% of P3 students.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of First-year (P1), Second-year (P2), and Third-year (P3) students (n=220)

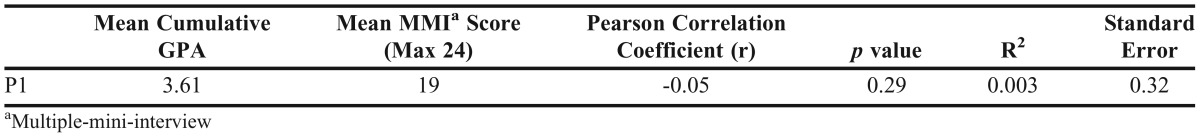

As illustrated in Table 2 for P1 students, a significant correlation was not observed between mean MMI score and GPA (r=-0.05; p=0.29). For P1 students, the mean MMI score in the regression model accounted for 0.3% of the total variation in a given student’s cumulative GPA (R2=0.003). The P1 students were the largest cohort in the study (n=105) and had the highest mean cumulative P1 GPA (3.61). Table 3 for P2 students illustrates no observed significant correlation between mean MMI score and mean cumulative GPA (r=0.04; p=0.35). For P2 students, the mean MMI score in the regression model accounted for 0.2% of the total variation in a given student’s first-year and second-year cumulative GPA (R2=0.002) and accounted for no variation in overall GPA (R2=0).

Table 2.

Regression Analysis for First-year (P1) Pharmacy Students (n=105)

Table 3.

Regression Analysis for Second-year (P2) Pharmacy Students (n=65)

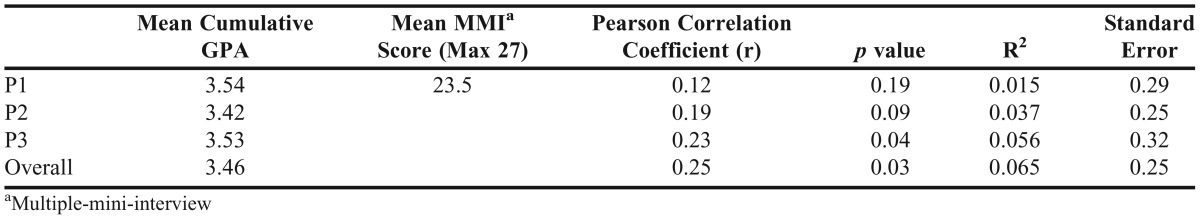

As depicted in Table 4 for P3 students, a significant positive correlation between mean MMI score, P3 GPA and overall cumulative GPA was observed (p=0.04, p=0.03, respectively). For P3 students, the mean MMI score in the regression model accounted for 1.5% of the total variation in a given student’s first-year cumulative GPA (R2=0.015), accounted for 3.7% of the total variation in a given student’s second-year cumulative GPA (R2=0.037), accounted for 5.6 % of the total variation in a given student’s third-year cumulative GPA (R2=0.037), and accounted for 6.5% of the total variation in a given overall cumulative GPA (R2=0.065).

Table 4.

Regression Analysis for Third-year (P3) Pharmacy Students (n=50)

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine the predictive validity of admission MMI score on academic success as measured by GPA, and the strength of association between MMI score and GPA for PharmD students. Although the MMI was developed to differentiate applicants based on noncognitive skills, it is understood that cognitive skills such as GPA and noncognitive skills, such as empathy, are not mutually exclusive. Therefore, mean MMI score and cumulative GPA to predict success across the didactic years in the PharmD program at USFCOP was analyzed using multiple regression analysis.

The results of this study were mixed across different cohorts of students. However, two cohorts of students demonstrated that cumulative GPA and mean MMI scores were negatively correlated (P1: n=105, r=-0.05, p=0.29; P2: n=65, r=-0.006, p=0.48). These results are consistent with what Eva et al demonstrated among a cohort of 117 applicants to medical school (r=-0.03, p<0.01).2 A meta-analysis conducted by Pau et al demonstrated that MMI performance was not associated with academic qualifications and was capable of testing noncognitive attributes in applicants.10 These correlations are important because they may indicate that the MMI is measuring something other than cognitive ability. Because the MMI is designed to differentiate candidates based on noncognitive abilities, it should be able to distinguish between attributes it was designed to assess.6

The results among P3 students demonstrated positive correlations between MMI and overall GPA (n=50, r=0.25, p=0.03). This suggests that students with stronger MMI scores are more likely to achieve a higher GPA. Previous research has described positive correlations between MMI and both cognitive and noncognitive measures. Eva et al demonstrated that MMI was positively correlated with OSCE-based licensing examinations among graduate medical students (r=0.43, p=0.05).2 Interestingly, Eva et al also reported that the strength of association increased with medical students’ seniority.2 Similarly, the results of the current study also demonstrated that stronger correlations were observed among P3 students compared with P2 and P1 students. The effect of MMI scores on pharmacy licensing examinations or OSCE scores has yet to be examined in PharmD students.

Interestingly, the students excluded from the analysis who either withdrew from the program or experienced a lapse in progression scored higher as a group on the MMI (20.2) than P1 (19) and P2 (19.3) students, but not P3 (23.5) students. It is possible that because the college uses a holistic admissions process, these individuals had strong noncognitive skills as evidenced by the MMI, but their cognitive measures were weaker. It’s also possible that these applicants didn’t have the persistence, motivation, or resilience to overcome inherent cognitive weaknesses. This would require us to maintain the importance of minimum competency as measured by cognitive skills in the admissions process with use of the MMI and other noncognitive measures to help the admissions process identify holistic applicants. It is unknown if using an intent-to-treat analysis that included students who experienced academic difficulty would yield different results as we only excluded six students in the analysis. A larger cohort would likely yield different results. This analysis, however, goes beyond this study as we only addressed MMI as a predictor of student success.

Measuring a student’s success through a single measure such as GPA is limited because multiple factors determine a student’s GPA. Courses comprising the cumulative GPA vary in amount of time devoted to basic science, clinical sciences, and courses that would assess qualities such as communication and interpersonal skills. At USFCOP, communication is emphasized heavily in the first year (P1) and clinical sciences courses such as pharmacokinetics and pharmacotherapeutics are heavily emphasized in the P2 and P3 years. The relationship between grades in certain courses and MMI score is unknown, although students scoring high on the MMI may likewise excel in courses that emphasize empathy, compassion, and integrity. It is unknown how many students actually possess both strong cognitive and noncognitive skills.

There are three main limitations to this study. The absence of noncognitive predictive measures, lack of comparison of MMI scores for denied and accepted applicants, and the small sample size. The first limitation includes the absence of noncognitive predictive measures from the dependent variables. Attempting to capture noncognitive abilities as opposed to cognitive abilities is challenging among health science students.4 An inherent limitation to the design of this study is the use of a student’s cumulative GPA as a measure of success. At its foundation, the MMI is a measurement of noncognitive skills, and GPA is a cognitive measure. To better capture predictive validity of the MMI, using noncognitive measures of student success, such as OSCE scores, grades that capture a student’s noncognitive skills such as final year experiential clerkship grades, conduct history, leadership skills, and/or involvement in student organizations, may allow for a better measurement of a pharmacy student’s noncognitive skills and give a more accurate prediction of success when using the MMI. As a follow-up to the current study, the researchers have begun investigating the effects of noncognitive data on MMI scores.

The lack of comparison of MMI scores for students denied admission is a second limitation. It is possible that accepted students performed better on the MMI compared with students not accepted to the program. If so, major correlations between MMI and academic success in the current study may not have been identified because the MMI may be associated with the academic success of all accepted students. The third limitation of this study is the small sample size, which impacts the significance of results. Further, the convenience sample represents one public, research-focused institution, which prevents generalizability to all PharmD students. Future directions for research should investigate the predictive validity of the MMI on noncognitive assessments such as end-of-year examination scores, OSCE scores, disciplinary difficulty, and leadership involvement among PharmD students.

CONCLUSION

A weak association between mean MMI score and GPA was observed, and the direction of the association between MMI and GPA was mixed across different cohorts of students in the PharmD curriculum. Significant correlations were identified between mean admission MMI score and cumulative P3 GPA and overall GPA for P3 students. Using cognitive measures, such as GPA, as the dependent variable for this study as opposed to noncognitive measures limited the ability to measure what the MMI was intended to capture. The results of this study can be applied to schools of pharmacy looking to incorporate the MMI into the pharmacy admissions process. This study supports the need for continuous assessment of the pharmacy admissions process and the importance of the impact of admissions criteria on students’ success in the PharmD curriculum.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We would like to thank LaShonda Coulbertson, MPH, for de-identifying and providing the data used for this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and key elements for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. Standards 2016. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/Standards2016FINAL.pdf. Accessed May 11, 2015.

- 2.Eva KW, Reiter HI, Trinh K, Wasi P, Rosenfeld J, Norman GR. Predictive validity of the multiple mini-interview for selecting medical trainees. Med Educ. 2009;43(8):767–775. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eva KW, Reiter HI, Rosenfield J, Norman GR. The relationship between interviewers’ characteristics and ratings assigned during a multiple mini-interview. Acad Med. 2004;79(6):602–609. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200406000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reiter HI, Eva KW, Rosenfeld J, Norman GR. Multiple mini-interviews predict clerkship performance and licensure examination performance. Med Educ. 2007;41(4):378–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2007.02709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy Annual Meeting. Interview techniques workshop. http://www.aacp.org/meetingsandevents/pastmeetings/2013/Pages/Programming.aspx. Accessed May 11, 2015.

- 6.Cox WC, McLaughlin JE, Singer D, Lewis M, Dinkins MM. Development and assessment of the multiple mini-interview in a school of pharmacy admissions model. Am J Pharm Educ. 2015;79(4):Article 53. doi: 10.5688/ajpe79453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cameron AJ, MacKeigan LD. Development and pilot testing of a multiple-mini-interview for admission to a pharmacy degree program. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(1):Article 10. doi: 10.5688/ajpe76110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCall KL, Allen DD, Fike DS. Predictors of academic success in a doctor of pharmacy program. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(5):Article 106. doi: 10.5688/aj7005106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen J. Set correlation and contingency tables. Appl Psychol Measure. 1988;12(4):425–434. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pau A, Jeevaratnam K, Chen YS, Fall AA, Khoo C, Nadarajah VD. The multiple mini-interview (MMI) for student selection in health professions training – a systematic review. Med Teach. 2013;35(12):1027–1041. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.829912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]