Summary

The presence of congenital appendages (wattles) on the throat of goats is supposed to be under genetic control with a dominant mode of inheritance. Wattles contain a cartilaginous core covered with normal skin resembling early stages of extremities. To map the dominant caprine wattles (W) locus, we collected samples of 174 goats with wattles and 167 goats without wattles from nine different Swiss goat breeds. The samples were genotyped with the 53k goat SNP chip for a subsequent genome‐wide association study. We obtained a single strong association signal on chromosome 10 in a region containing functional candidate genes for limb development and outgrowth. We sequenced the whole genomes of an informative family trio containing an offspring without wattles and its heterozygous parents with wattles. In the associated goat chromosome 10 region, a total of 1055 SNPs and short indels perfectly co‐segregate with the W allele. None of the variants were perfectly associated with the phenotype after analyzing the genome sequences of eight additional goats. We speculate that the causative mutation is located in one of the numerous gaps in the current version of the goat reference sequence and/or represents a larger structural variant which influences the expression of the FMN1 and/or GREM1 genes. Also, we cannot rule out possible genetic or allelic heterogeneity. Our genetic findings support earlier assumptions that wattles are rudimentary developed extremities.

Keywords: genome sequencing, genome‐wide association study, limb development, livestock, skin appendages

Wattles represent congenital thumb‐shaped appendages on the ventral throat and are common in domestic goats (Capra hircus). They consist of normal epidermis, dermis, subcutis, muscles, nerves, blood vessels and a central cartilage. The function of these wattles is still under debate (Heer 1922; Imagawa et al. 1994). The localization and anatomical description suggest that this tissue might have a branchiogenic origin (Blanc 1897; Siemens 1921). Similar structures were also occasionally reported in other species such as sheep, pigs and humans (Darwin 1868; Mouquet 1895; Fröhner 1907; Lush 1926; Schumann 1957; Weissengruber 2000; Coras et al. 2005; Nasser et al. 2011). Wattles were alternatively designated as appendices colli, cervical chondrocutaneous remnants or congenital cartilaginous rest of neck (Weissengruber 2000; Coras et al. 2005; Nasser et al. 2011). Wattles in domestic goats already fascinated people in the ancient world, and their appearance is supposed to be selectively neutral (Disselhorst 1906; Fröhner 1907). Ancient Greek and Italian art has often given a goat‐like appearance with wattles to all deities (Disselhorst 1906; Fröhner 1907). Goats can have zero, one or two wattles. In some cases, they are located ectopically at other regions of the head (Lush 1926). Wattles are known worldwide in various goat breeds, and usually this trait is not actively selected for or against appearance by breeders (Lush 1926; Ricordeau 1967; Lauvergne et al. 1987). Therefore, wattles segregate in most goat breeds. Caprine wattles are supposed to be caused by an autosomal dominant W allele, and earlier studies indicate that there is no linkage between the W locus and the loci for horns or sex (Kronacher & Ogrizek 1924; Lush 1926; Asdell & Buchanan Smith 1928; Ricordeau 1967; OMIA 001061‐9925).

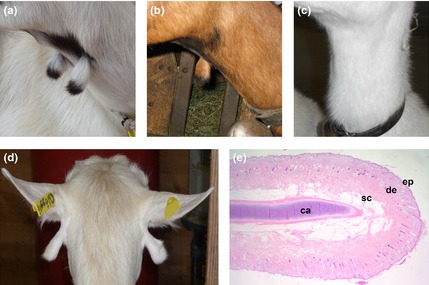

We collected samples of 341 breeding goats from nine different Swiss breeds and scored the presence or absence of wattles (Table S1). Most goats with wattles showed two more or less equally sized wattles on the ventral throat (Fig. 1a). About 7.5% of the collected goats with wattles had only a single wattle on one side (left or right; Fig. 1b). In a single case, we found a goat with two differently sized wattles at an abnormal localization below the ears (Fig. 1d). A histological section of a wattle from a slaughtered goat confirmed the previously described substructure with a cartilaginous core covered with normal skin (Fig. 1e; Imagawa et al. 1994). Therefore, we speculate that caprine wattles, due to their anatomical features, may represent regressed limbs, as was discussed previously (Mouquet 1895). This hypothesis is also supported by our observation that wattles in Swiss goat breeds usually show the same coat color patterning as the limbs in multicolored goat breeds (Fig. S1). The presence of wattles is not correlated with sex or with the presence of horns or beard (data not shown). For some goats, we had the phenotype information for related animals, which confirmed the previously reported monogenic autosomal dominant inheritance (Fig. S2). Taken together, our results are consistent with the limited information about wattles reported in the literature (Mouquet 1895; Siemens 1921; Kronacher & Ogrizek 1924; Lush 1926; Ricordeau 1967; Lauvergne et al. 1987).

Figure 1.

Variation of wattles in Swiss goats. (a) Bilateral presence of two wattles in a Peacock goat. (b) A single wattle on the right side in a Chamois colored goat. (c) A Saanen goat without wattles. (d) Ectopic wattles located directly under the ears in an Appenzell goat. (e) Histological section of a wattle showing normal skin [epidermis (ep), dermis (de), subcutis (sc)] covering a centrally located core of mature and normal differentiated cartilage (ca) (hematoxylin and eosin staining; 16 ×).

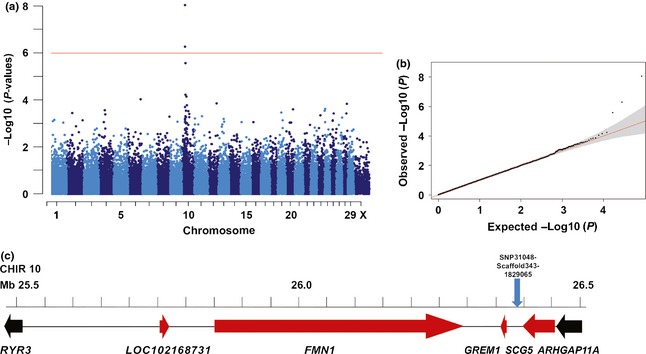

A cohort of 174 goats with wattles and 167 goats without wattles was genotyped using Illumina's goat SNP50 BeadChip containing 53 346 SNP markers (Tosser‐Klopp et al. 2014). To map the W locus in Swiss goats, we performed a genome‐wide association study (GWAS) for the wattles phenotype and detected a genome‐wide significant association on goat chromosome (CHIR) 10 (Fig. 2). The strongest association with a P‐value of 8.9 × 10−9 was found for SNP31048‐SCAFFOLD343‐1829065 (Table S2). Two SNPs exceeded the Bonferroni significance threshold (P = 1.02 × 10−6). They are located on CHIR 10 at 26 397 973 bp and 26 526 103 bp (goat genome assembly CHIR_1.0; Dong et al. 2013). No other region in the genome showed genome‐wide associated SNPs. The most significantly associated SNPs from our GWAS were located in a genomic region with putatively functional candidate genes for the development of extremities (Fig. 2c). The two genes encoding formin 1 (FMN1) and gremlin 1 (GREM1) are known to play a role during limb outgrowth and limb development of mammals and thus represent good functional candidate genes for a developmental phenotype like wattles. The gene annotation of that goat genome region and the order of these genes corresponds well to the syntenic human and mouse chromosome segments. FMN1 is relevant for cell polarization and limb patterning (Mass et al. 1990; Woychik et al. 1990; Evangelista et al. 2003). GREM1, a bone morphogenic protein (BMP) antagonist, controls mammalian limb outgrowth and chondrogenesis (Merino et al. 1999; Zuniga et al. 1999). BMP signaling during limb patterning must be moderated by GREM1 to maintain the signaling loop between the zone of polarizing activity and the apical ectodermal ridge. Mutations in the murine Fmn1 and Grem1 genes were reported in mouse limb deformity phenotypes (Mass et al. 1990; Woychik et al. 1990; Zuniga et al. 2004, 2012; Pavel et al. 2007). Genomic rearrangements of the GREM1–FMN1 locus were also reported to cause oligosyndactyly in humans (Dimitrov et al. 2010). A 40‐kb duplication upstream of GREM1 including the secretogranin V (7B2 protein) gene (SCG5) causes a colorectal polyp syndrome in humans (Jaeger et al. 2012). This mutation is associated with increased allele‐specific GREM1 expression. Increased GREM1 expression is predicted to cause reduced BMP pathway activity (Jaeger et al. 2012). Interestingly, the best associated SNP in the GWAS for wattles in the goat was located upstream of GREM1 (Fig. 2c). Therefore, we speculate that a regulatory mutation influencing the expression of the GREM1–FMN1 locus might be responsible for the development of the polyp‐like skin appendages in goats.

Figure 2.

Genome‐wide association study for wattles in goats. (a) The red line in the Manhattan plot indicates the Bonferroni significance threshold for association (−log10 P = 5.99) showing two genome‐wide significantly associated SNPs on CHIR 10. (b) The quantile–quantile (QQ) plot shows the observed vs. expected log P‐values. The straight red line in the QQ plot indicates the distribution of SNP markers under the null hypothesis, and the skew at the right edge indicates that these markers are more strongly associated with the trait than would be expected by chance. (c) Gene content of the associated region. The most significantly associated SNP is shown as the blue arrow. For the mutation analysis, the region containing the genes shown in red between RYR3 and ARHGAP11A was considered.

For mutation analysis, we selected an informative trio of Saanen goats for whole genome sequencing (WGS). Under the assumption of a monogenic dominant inheritance, the parents are obligate heterozygotes carrying a single copy of the W allele and the daughter is homozygous for the alternative w allele (Fig. S2b). We identified sequence variants (SNPs and short indels) from the WGS data in a 947‐kb segment containing the GREM1–FMN1 locus (Fig. 2c). Besides the coding regions, we included the up‐ and downstream regions of both candidate genes, which are supposed to contain regulatory important sequence elements. This region also contained the SCG5 gene and an uncharacterized locus (LOC102168731). In this 947‐kb interval, we detected a total of 1267 variants, of which 1055 perfectly co‐segregated with the alleles at the W locus, meaning that the offspring was homozygous and both parents were heterozygous (Table S3). As we were not aware of the exact wattles phenotype of the Chinese goat, which was sequenced for the establishment of the reference genome, we included all variants at which the offspring was homozygous for either the reference or the alternative allele. Initially, we focussed on coding variants in the annotated genes of the associated region, but genotyping data of a variable number of animals with and without wattles belonging to different goat breeds revealed that none of the three detected exonic variants of FMN1 were perfectly associated with the wattles phenotype (Table S4). In addition, we have genotyped the single missense mutation in all available relatives to evaluate whether this variant might be a candidate causal mutation in the selected goat family used for whole genome sequencing. This showed that the inheritance of the alleles at this SNP located in exon 3 of FMN1 is not perfectly linked with the assumed segregation of the W mutation (Fig. S2b) and can be ruled out as being causative. Finally, the variant lists of whole genome sequencing data from five goats without wattles and three goats with wattles of various breeds produced in our laboratory in the course of other ongoing studies allowed us to exclude all other detected intronic and intergenic variants as being causative for wattles (Table S3). In addition, we performed visual inspection of the mapped sequence data but did not find evidence of structural variants such as larger sized indels or segmental duplications. The sensitivity of our variant detection might have been compromised by the limited sequence coverage in combination with the presence of many gaps in the reference sequence of the critical interval and the employed short‐read sequencing technology.

In conclusion, nearly 90 years after the first breeding experiments revealed that wattles follow a Mendelian inheritance, we have mapped the responsible mutation on goat chromosome 10. This study provides one of the first examples of successful application of the recently developed SNP chip for goats (Kijas et al. 2014; Tosser‐Klopp et al. 2014). As caprine wattles resemble early stages of developing limbs, the obtained association to the FMN1 and GREM1 genes, which are known to play an important role during mammalian limb patterning, supports earlier speculations on the anatomical origin of wattles. By sequencing the whole genomes of several goats, we unsuccessfully tried to identify the causative W mutation. We speculate that this is probably due to the draft status of the goat reference genome and the employed sequencing method, which impairs the ability to detect all kinds of variants but in particular large structural variants. In addition, we cannot exclude that genetic and/or allelic heterogeneity may influence the phenotype.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Identical coat color pattering of the wattles and limbs in different goat breeds.

Figure S2. Pedigree of two goat families showing the autosomal dominant inheritance of the wattles (W).

Table S1. Number of animals from nine Swiss goat breeds with and without wattles used in this study.

Table S2. Two best associated SNPs of the genome‐wide association study (GWAS).

Table S3. Sequence variants of 11 sequenced animals in the critical region on goat chromosome 10.

Table S4. Coding FMN1 variants in the associated CHIR 10 region.

Appendix S1 Supplementary methods.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to all goat breeders and the Swiss goat breeding association, namely Michèle Ackerman, Brigitta Colomb, Mylène Docquier, Isabelle Durussel‐Gerber, Muriel Fragnière, Leonardo Murgiano and Natalie Wiedemar, for their assistance. We also thank the Centre National de Génotypage and NCCR Genomics Platform of the University of Geneva for SNP genotyping and the Next Generation Sequencing Platform of the University of Bern for performing the WGS experiment.

References

- Asdell S.A. & Buchanan Smith A.D. (1928) Inheritance of color, beard, tassels and horns in the goat. Journal of Heredity 19, 425–30. [Google Scholar]

- Blanc M.L. (1897) Les pendeloques et le canal du soyon. Journal de L'anatomie et de la Physiologie Normale et Pathologiques de l'Homme et des Animaux 33, 283–302. [Google Scholar]

- Coras B., Hafner C., Roesch A., Vogt T., Landthaler M. & Hohenleutner U. (2005) Congenital cartilaginous rests of the neck (wattles). Dermatologic Surgery 31, 1349–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwin C. (1868) The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication. John Murray, London: 1st edn, 75. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrov B.I., Voet T., De Smet L., Vermeesch J.R., Devriendt K., Fryns J.P. & Debeer P. (2010) Genomic rearrangements of the GREM1–FMN1 locus cause oligosyndactyly, radio‐ulnar synostosis, hearing loss, renal defects syndrome and Cenani–Lenz‐like non‐syndromic oligosyndactyly. Journal of Medical Genetics 47, 569–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disselhorst R. (1906) Zur morphologie und anatomie der halsanhänge beim menschen und den ungulaten. anatomischer anzeiger. Centralblatt für die Gesamte Wissenschaftliche Anatomie, Herausgegeben von Dr. Karl von Bardeleben 28, 321–7. [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y., Xie M., Jiang Y. et al (2013) Sequencing and automated whole‐genome optical mapping of the genome of a domestic goat (Capra hircus). Nature Biotechnology 2, 135–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evangelista M., Zigmond S. & Boone C. (2003) Formins: signaling effectors for assembly and polarization of actin filaments. Journal of Cell Science 116, 2603–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fröhner R. (1907) Morphologie und Anatomie der Halsanhänge beim Menschen und den Ungulaten. Bibliotheca Medica, Abteilung A.

- Heer A. (1922). Zur Entwicklung und Morphologie der Appendices colli (Glöckchen, Berlocken) der Ziege. 10. Beitrag zum Bau und zur Entwicklung von Hautorganen bei Säugetieren. Inaugural‐ Dissertation.

- Imagawa T., Kon Y., Kitagawa H., Hashimoto Y., Uehara M. & Sugimura M. (1994) Anatomical and histological re‐examination of appendices colli in the goat. Annals of Anatomy 176, 175–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger E., Leedham S., Lewis A. et al (2012) Hereditary mixed polyposis syndrome is caused by a 40‐kb upstream duplication that leads to increased and ectopic expression of the BMP antagonist GREM1. Nature Genetics 44, 699–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kijas J.W., Ortiz J.S., McCulloch R., James A., Brice B., Swain B., Tosser‐Klopp G. & Goat Genome Consortium (2014) Genetic diversity and investigation of polledness in divergent goat populations using 52 088 SNPs. Animal Genetics 44, 325–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronacher C. & Ogrizek A. (1924) Vererbungsversuche und beobachtungen an schweinen. Zeitschrift für Induktive Abstammungs‐ und Vererbungslehre 34, 29–33/109–110. [Google Scholar]

- Lauvergne J.J., Renieri C. & Audiot A. (1987) Estimating erosion of phenotypic variation in a French goat population. Journal of Heredity 78, 307–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lush J.L. (1926) Inheritance of horns, wattles, and color: in grade Toggenburg Goats. Journal of Heredity 17, 73–91. [Google Scholar]

- Mass R.L., Zeller R., Woychik R.P., Vogt T.F. & Leder P. (1990) Disruption of formin‐encoding transcripts in two mutant limb deformity alleles. Nature 346, 853–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merino R., Rodriguez‐Leon J., Macias D., Gañan Y., Economides A.N. & Hurle J.M. (1999) The BMP antagonist Gremlin regulates outgrowth, chondrogenesis and programmed cell death in the developing limb. Development 126, 5515–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouquet M. (1895) Sur les pendeloques. Bulletin et Mémoires de la Société Centrale de Médicine 49, 241–4. [Google Scholar]

- Nasser H.A., Iskandarani F., Berjaoui T. & Fleifel S. (2011) A case report of bilateral cervical chondrocutaneous remnants with review of the literature. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 46, 998–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavel E., Zhao W., Powell K.A., Weinstein M. & Kirschner L.S. (2007) Analysis of a new allele of limb deformity (ld) reveals tissue‐ and age‐specific transcriptional effects of the Ld Global Control Region. International Journal of Developmental Biology 51, 273–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricordeau G. (1967) Hérédité des pendeloques en race Saanen. Différences de Fécondité Entre les Génotypes Avec et Sans Pendeloques. Annales de Zootechnie 16, 263–70. [Google Scholar]

- Schumann H. (1957) Die glöckchen bei schwein, schaf und ziege. Zeitschrift für Tierzüchtung und Züchtungsbiologie 69, 24–9. [Google Scholar]

- Siemens H.W. (1921) Zur kenntnis der sogenannten ohr‐ und halsanhänge (branchiogene Knorpelnaevi) . Archiv für Dermatologie und Syphilis 132, 186–205. [Google Scholar]

- Tosser‐Klopp G., Bardou P., Bouchez O. et al (2014) Design and characterization of a 52K SNP chip for goats. PLoS ONE 9, e86227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissengruber G.E. (2000) Appendices colli beim hausschwein (Sus scrofa f. domestica). Tierärztliche Praxis 28, 276–80. [Google Scholar]

- Woychik R.P., Maas R.L., Zeller R., Vogt T.F. & Leder P. (1990) ‘Formins’: proteins deduced from the alternative transcripts of the limb deformity gene. Nature 346, 850–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuniga A., Haramis A.P., McMahon A.P. & Zeller R. (1999) Signal relay by BMP antagonism controls the SHH/FGF4 feedback loop in vertebrate limb buds. Nature 401, 598–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuniga A., Michos O., Spitz F. et al (2004) Mouse limb deformity mutations disrupt a global control region within the large regulatory landscape required for Gremlin expression. Genes & Development 18, 1553–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuniga A., Laurent F., Lopez‐Rios J., Klasen C., Matt N. & Zeller R. (2012) Conserved cis‐regulatory regions in a large genomic landscape control SHH and BMP‐regulated Gremlin1 expression in mouse limb buds. BMC Developmental Biology 12, 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Identical coat color pattering of the wattles and limbs in different goat breeds.

Figure S2. Pedigree of two goat families showing the autosomal dominant inheritance of the wattles (W).

Table S1. Number of animals from nine Swiss goat breeds with and without wattles used in this study.

Table S2. Two best associated SNPs of the genome‐wide association study (GWAS).

Table S3. Sequence variants of 11 sequenced animals in the critical region on goat chromosome 10.

Table S4. Coding FMN1 variants in the associated CHIR 10 region.

Appendix S1 Supplementary methods.