Abstract

Aims

The clinical characteristics, initial presentation, management, and outcomes of patients hospitalized with new‐onset (first diagnosis) heart failure (HF) or decompensation of chronic HF are poorly understood worldwide. REPORT‐HF (International REgistry to assess medical Practice with lOngitudinal obseRvation for Treatment of Heart Failure) is a global, prospective, and observational study designed to characterize patient trajectories longitudinally during and following an index hospitalization for HF.

Methods

Data collection for the registry will be conducted at ∼300 sites located in ∼40 countries. Comprehensive data including demographics, clinical presentation, co‐morbidities, treatment patterns, quality of life, in‐hospital and post‐discharge outcomes, and health utilization and costs will be collected. Enrolment of ∼20 000 adult patients hospitalized with new‐onset (first diagnosis) HF or decompensation of chronic HF over a 3‐year period is planned with subsequent 3 years follow‐up.

Perspective

The REPORT‐HF registry will explore the clinical characteristics, management, and outcomes of HF worldwide. This global research programme may have implications for the formulation of public health policy and the design and conduct of international clinical trials.

Keywords: Heart failure, Hospitalized, Global, Morbidity, Mortality, Quality of life

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a global public health problem affecting millions worldwide.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 In the USA, the prevalence is 5.7 million and there are 670 000 new cases per year, while there are another 15 million people living with HF in Europe.13, 14, 15 In addition, there are >1 million admissions for HF annually in both the USA and Europe, accounting for the vast majority spent each year on HF‐related care.13, 14, 16 However, the socio‐economic burden of HF is especially worrisome in the low‐ and middle‐income regions of Africa, South America, the Middle East, and Asia Pacific, where the prevalence of HF is rising rapidly and the clinical characteristics, treatment patterns, and outcomes vary substantially.12, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23

Several observational registries have been conducted in patients with HF (Table 1).1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 These registries have either focused on in‐patient characterization and short‐term outcomes or maintained separate samples of acute HF hospitalizations and chronic HF follow‐up, limiting understanding of the transition from chronic maintenance to an acute state requiring hospitalization.24, 25 No prior detailed, longitudinal evaluations of long‐term disease progression, healthcare utilization, and health economics on a global scale have been reported. Furthermore, while registries have been conducted to compare within‐region differences in disease characteristics and outcomes, no truly international prospective registry exists with uniform data collection and systematic follow‐up using a common protocol. In addition, most registries have been based on non‐consecutive enrolment, which may result in a sample that is not representative of the real‐world patient inflow. Clearly, there remains an unmet clinical need in HF to design and conduct a geographically representative registry to shape public policy at all levels and guide research endeavours.

Table 1.

Overview of other heart failure registries

| Registries |

ADHERE1 ADHERE1

|

OPTIMIZE‐HF2 OPTIMIZE‐HF2

|

GWTG‐HF3 GWTG‐HF3

|

EHFS I4 EHFS I4

|

EHFS II5 EHFS II5

|

ESC‐HF Pilot6 ESC‐HF Pilot6

|

ESC‐HF7 ESC‐HF7

|

ATTEND8 ATTEND8

|

ADHERE‐AP9 ADHERE‐AP9

|

ASIAN‐HF10 ASIAN‐HF10

|

ALARM‐HF11 ALARM‐HF11

|

THESUS‐HF12 THESUS‐HF12

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regions/ countries | USA | USA | USA | Europea | Europeb | Europec | Europed | Japan | Asia‐Pacifice | Asia‐Pacificf | Multinationalg | Africah |

| n | 105 388 | 48 612 | 110 621 | 11 327 | 3580 | 1892 | 12 440 | 4842 | 10 171 | 5000 | 4953 | 1006 |

| Time frame | 2001–2004 | 2003–2004 | 2005–present | 2000–2001 | 2004–2005 | 2009–2010 | 2011–2013 | 2007–2011 | 2006–2008 | 2013–present | 2006–2007 | 2007–2010 |

| Data collection | Prospective | Prospective | Prospective | Retrospective | Prospective | Prospective | Prospective | Prospective | Retrospective | Prospective | Retrospective | Prospective |

| PROs | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | KCCQ | – | – |

| Follow‐up | – | 60–90 days | – | – | 3 months | 1 year | – | – | – | 3 years | – | 6 months |

ADHERE, Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry; ADHERE‐AP, Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry International–Asia Pacific; ALARM‐HF, Acute Heart Failure Global Registry of Standard Treatment; ASIAN‐HF, Asian Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure; ATTEND, Acute Decompensated Heart Failure Syndromes; EHFS I, European Heart Failure Survey I; EHFS II, European Heart Failure Survey II; ESC‐HF, European Society of Cardiology‐Heart Failure; GWTG‐HF, Get With The Guidelines‐Heart Failure; KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; OPTIMIZE‐HF, Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients With Heart Failure; PROs, patient reported outcomes; THESUS‐HF, The Sub‐Saharan Africa Survey of Heart Failure.

Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal, Russia, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, The Netherlands, UK.

Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Denmark, Egypt, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Lithuania, The Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Russia, Serbia and Montenegro, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, Ukraine, UK.

Austria, France, Denmark, Germany, Greece, Italy, Poland, The Netherlands, Norway, Romania, Spain, Sweden.

Austria, Bosnia Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Egypt, France, Greece, Hungary, Israel, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Turkey.

Australia, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand.

China, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand.

Australia, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Mexico, Spain, Turkey, UK.

Cameroon, Ethiopia, Kenya, Mozambique, Nigeria, Senegal, South Africa, Sudan, Uganda.

Thus, REPORT‐HF (International REgistry to assess medical Practice with lOngitudinal obseRvation for Treatment of Heart Failure), a global, prospective, and observational study initiated during index hospitalization for new‐onset (first diagnosis) HF or decompensation of chronic HF designed to capture comprehensive data on clinical characteristics, management, and outcomes with longitudinal follow‐up over 3 years, is proposed in order to enhance the understanding of the epidemiology of HF worldwide.

Study design

Patients hospitalized with a primary diagnosis of new‐onset (first diagnosis) HF or decompensation of chronic HF as assessed by the clinician–investigator are eligible for enrolment. Exclusion criteria include current or recent participation in a clinical trial of any investigational treatments. Each centre will implement an admission log that will also document reasons for patients not being enrolled in REPORT‐HF. Each patient will be followed for 3 years or until death, withdrawal of consent, or study termination.

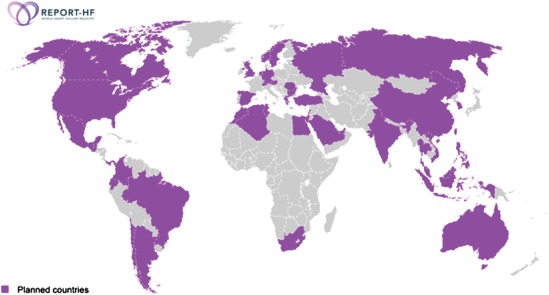

Prospective enrolment will take place at ∼300 hospitals in ∼40 representative countries across Europe, North and Latin America, Africa, Asia and the Pacific, and the Middle East (Figure 1). The number of participating centres for each country takes into consideration the size of its population. Investigators are asked to recruit consecutive patients within assigned enrolment intervals corresponding to an average of ∼70 patients over a period of ∼3 years. For smaller hospitals, this may translate into an open enrolment to include all patients meeting inclusion criteria, while in larger medical centres patients may be enrolled over a pre‐defined period in order to ensure that the workload is manageable and that recruitment is evenly distributed across days of the week and seasons of the year. The first patient was enrolled in July 2014 and, by end of 2014, ∼60 sites from 12 countries had been initiated.

Figure 1.

Planned countries participating in REPORT‐HF.

Background HF therapy will be left to the discretion of the treating physician, but all sites are encouraged to manage patients according to standard local practice as informed by current guideline‐based recommendations. This study will be conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the protocol submitted and approved by the Institutional Review Board and/or ethics committee at each participating centre, and written informed consent obtained from all patients or a designated surrogate medical decision‐maker prior to enrolment.

Data collection and follow‐up

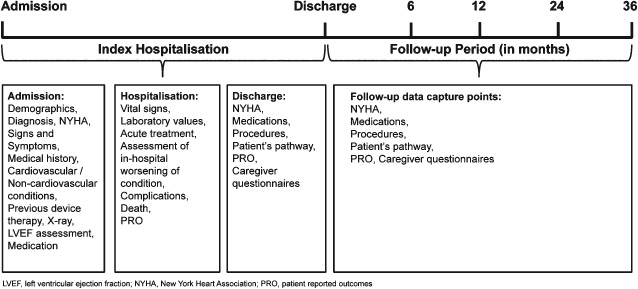

The proposed time frame for data collection during hospitalization and post‐discharge is shown in Figure 2. Clinician–investigators will enrol patients during the index admission and, with the assistance of the study coordinator, will collect data on patient demographics, past medical history (i.e. cardiac and non‐cardiac co‐morbidities), admission and discharge medications, vital signs and physical exam, laboratory values, acute management (i.e. HF‐ and cardiovascular‐related therapies and procedures), and hospital course (i.e. in‐hospital worsening HF and other adverse events). Pre‐specified data collection points will occur at 6 months, 1 year, and annually thereafter until study completion. At each data collection point, study staff will obtain an updated medical and medication history, NYHA functional class, review of symptoms, vital status, and interval events including invasive procedures, hospitalizations, and scheduled and unscheduled office and emergency room visits. Follow‐up information from study participants will be collected via telephone interviews unless a regular follow‐up visit is planned at the index site according to local practice. Every effort will be made by the study personnel to obtain confirmation of the information. In addition, vital status will be supplemented using national reporting databases where available.

Figure 2.

Data collection time points.

Patient and caregiver questionnaires

Validated questionnaires will optionally be completed at specific time points to evaluate the quality of life (QOL) of the patient and to assess the burden placed on the caregiver (Table 2). A generic health status questionnaire [EuroQoL‐5 Dimensions questionnaire (EQ‐5D)]26 and a HF‐specific questionnaire [Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ)]27 will be serially administered to the patient. The EQ‐5D is a widely used, self‐administered questionnaire designed to assess health status in adults. The tool assesses five dimensions indicative of QOL (mobility, self‐care, usual activity, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression) and provides a self‐rated global health status using a visual analogue scale ranging from 0 (i.e. ‘worst possible health state’) to 100 (i.e. ‘best possible health state’). On the day after admission (day 2), a special (recall) version of the EQ‐5D questionnaire will be administered asking the patient to describe retrospectively how he or she felt on the day of admission, while the standard EQ‐5D questionnaire will be administered on day 2 (in addition to the recall version) and for the remainder of the study. The KCCQ tool is another self‐administered questionnaire covering physical activity, clinical symptoms, social function, self‐efficacy and knowledge, and QOL each measured using a unique Likert scale. The KCCQ questionnaire is more extensive than the EQ‐5D questionnaire and will only be administered in select countries (i.e. Germany, Spain, Russia, the UK, and the USA).

Table 2.

Administration time points of patient and caregiver questionnaires

| Questionnaires | Administration time points | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index hospitalization | Follow‐up data capture points | |||||||

| Day 2 | Day 5 | Discharge | 6 months | 1 year | 2 year | 3 year | ||

| Patient | EQ‐5D | Xa | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| KCCQb | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Caregiver | CBQ‐HFc | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| WPAIc | X | X | X | X | X | |||

EQ‐5D, [EuroQoL‐5 Dimensions questionnaire; KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; CBQ‐HF, Caregiver Burden Questionnaire–Heart Failure; WPAI, Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire.

EQ‐5D administration on Day 2 with additional recall for admission day.

Administered only in selected countries.

Administered only in English‐speaking countries.

Similarly, the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire (WPAI)28 and the Caregiver Burden Questionnaire for Heart Failure (CBQ‐HF)29 will be utilized to assess the burden placed on the caregiver. The WPAI includes six items that measure absenteeism, presenteeism, lost work productivity, and activity impairment. In contrast, the CBQ‐HF consists of four domains measuring the impact of caring for HF patients on aspects of the caregiver's daily life including physical well‐being, emotional health, social life and relationships, and lifestyle.

Statistical analysis plan

A sample size of 20 000 participants has been proposed to estimate comparisons of interest and taking into account potential losses to follow‐up. In order to perform meaningful analyses comparing proportions across clinically relevant subgroups (i.e. defined by combinations of geographic area, type of admission unit, clinical characteristics, etc.), a sample size of 300 in each of the strata will enable pairwise comparisons to detect a margin of difference of up to 10%. The target sample size will be re‐evaluated when ∼50% of patients have been recruited. A full description of data status will be provided to the steering committee in periodic reports. Missing or incomplete data will be addressed using imputation algorithms along with sensitivity analyses.

The primary analysis will describe the geographic variation in clinical characteristics, management, hospital course during index admission, and long‐term health resource utilization (HRU; i.e. scheduled and unscheduled office appointments, emergency room visits, and hospitalizations) and survival. Secondary analyses will be performed to evaluate patient QOL and caregiver burden. In addition, the associations between patient management strategies and HRU will be assessed. Finally, a disease model will be created combining clinical outcomes and disease status data to improve our understanding of disease pathophysiology and progression as well as relevant drivers of HRU.

Discussion

Heart failure is a global public health problem and socio‐economic burden, which may be at least partially attributable to a poor understanding of this heterogeneous syndrome.24, 25 Although disease‐based registries remain the primary source of real‐world data on chronic medical conditions and fundamental to shaping public health policy at all levels and guiding research from bench to bedside, limitations of the available registry data include, but are not limited to, poor geographic representation, non‐consecutive patient enrolment, incomplete data capture, and absent or short duration of follow‐up. REPORT‐HF is a global, prospective, and observational registry initiated during the index HF hospitalization with longitudinal patient follow‐up of up to 3 years aiming to advance the comprehension of the epidemiology of HF worldwide.

There are several salient features of this observational study which merit further mention. REPORT‐HF is the first truly global observational experience in HF, with ∼300 centres in ∼40 representative countries across Europe, North and Latin America, Africa, Asia and the Pacific, and the Middle East. In contrast, prior large‐scale HF registries have primarily enrolled patients in North America and Western Europe, collectively representing only slightly more than 15% of the world's population. In addition, previous observational experiences in HF have primarily relied on non‐consecutive enrolment of patients admitted with an unequivocal primary diagnosis of HF, which may have led to a non‐random sampling of lower acuity patients. Thus, this study will employ consecutive or intermittently consecutive enrolment in order to obtain a representative cohort while minimizing the workload required of study personnel.

Although data collection in registries is often limited by resource availability and variation in routine clinical practice, REPORT‐HF will utilize a standard protocol and case report form across all centres including follow‐up in order to provide a detailed description of clinical characteristics and management of HF patients of all levels of acuity, across the spectrum of clinical settings, and over time. In addition, REPORT‐HF will provide insights into the initiation and titration of guideline‐directed medical therapies over time including the initial real‐world experience with promising and emerging treatment options. Most importantly, REPORT‐HF will for the first time serially track outcomes including HRU (i.e. scheduled and unscheduled office appointments, emergency room visits, and hospitalizations), patient QOL and caregiver burden, and survival over a time frame of years in a geographically diverse and representative population.

In an era of globalization in cardiovascular research, the most significant contribution of REPORT‐HF may be to the future design and conduct of international clinical trials, which have traditionally suffered from poor enrolment. Interestingly, post‐hoc analyses of phase III clinical trial databases have found substantial geographic variation in the aetiology of HF, co‐morbid disease states, background therapy, and event rates (i.e. hospitalizations and mortality) despite employing specific inclusion and exclusion criteria to select for a relatively homogeneous and enriched study population.30, 31 Furthermore, there is a growing appreciation among the scientific community that failure to consider these regional differences in patient characteristics, management, and outcomes at the planning stage may impact both the response to therapy and the success or failure of pivotal trials.32, 33 Thus, REPORT‐HF provides the opportunity to preview patient characteristics and document heterogeneity in patient management as well as its clinical consequences at participating centres. In addition, the findings from this study may provide insights into the operational aspects of global clinical trials including, but not limited to, assessing potential sites for enrolment capacity, refining inclusion and exclusion criteria, and selecting endpoints.34

There are several limitations of the data inherent to the conduct of a large‐scale international registry. First, patients will be enrolled at the point‐of‐care by clinician–investigators based on their judgement without central validation. Although this raises the potential for misclassification, diagnostic criteria for HF will be discussed at investigator meetings. HF remains a challenging clinical diagnosis and there is no clear definition for an ‘acute’ episode of care or criteria for hospital admission. Secondly, although the protocol is designed to facilitate data collection and minimize workload, there will inevitably be missing data and patients lost to follow‐up. However, every effort will be made to contact patients, their caregivers, and/or treating physicians, and, where applicable, medical records will be obtained. In addition, statistical approaches for imputation accounting for observational uncertainty and borrowing from observed data will be used to mitigate the issue of missing data. Finally, since this study is observational in nature, information on all outcomes might not be available from recall, and for those recorded outcomes there will be no independent adjudication. However, this study will include an unprecedented follow‐up duration of 3 years linking the initial acute hospitalization with subsequent clinical events, and vital status will be supplemented using national reporting databases where applicable.

There is currently an unmet clinical need in HF to design and conduct a global registry to facilitate a clearer understanding of this heterogeneous patient population, inform public policy decisions, and guide clinical research efforts. REPORT‐HF is an international registry of patients hospitalized with new‐onset (first diagnosis) HF or decompensation of chronic HF that is diverse and geographically representative, employs consecutive or intermittently consecutive enrolment, and captures comprehensive and longitudinal data on clinical characteristics, management, and outcomes. This study aims to enhance the current understanding of HF worldwide and may have implications for the future design and conduct of quality improvement initiatives and clinical trials.

Funding

The REPORT‐HF registry is sponsored by Novartis Pharma AG.

Conflict of interest: G.F. is a member of the Steering Committee of trials sponsored by Novartis, Cardiorentis, Bayer, and Vifor. J.G.F.C. reports grants and personal fees from Novartis and Amgen, and personal fees from Trevena. S .P.C. has received research support from Cardiorentis, Cardioxyl, Intersection Medical, and Novartis, and has consulted for Cardiorentis, Cardioxyl, Intersection Medical, Novartis, Insys, and Abbott Point‐of‐Care. C.L.S.P. has received research support from Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and Vifor Pharma, and has consulted for Novartis, Bayer, Astra Zeneca, and Vifor Pharma. C.E.A. receives speaker honoraria, consultancy fees, and research grants from Novartis, ResMed, Bayer, Servier, and Boehringer Ingelheim. G.E. reports personal fees from Novartis. U.D. receives consulting fees from Novartis and Vifor Pharma, and research grant from AstraZeneca. S.V.P. receives honoraria from Laboratorios Bagó S.A., Laboratorios Raffo S.A., Biotoscana Argentina, and Novartis. M.G., G.B., A.N., A.S., and T.M. are employees and shareholders of Novartis Pharma AG. M.G. is a consultant for Abbott Laboratories, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer Schering Pharma, Bayer HealthCare, Cardiorentis, CorThera, Cytokinetics, CytoPherx, DebioPharm, Errekappa Terapeutici, GlaxoSmithKline, Ikaria, Intersection Medical, Inc., Johnson and Johnson, Medtronic, Merck, Novartis Pharma, Ono Pharma USA, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Palatin Technologies, Pericor Therapeutics, Protein Design Laboratories, Sanofi‐Aventis, Sigma Tau, Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Sticares InterACT, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, and Trevena Therapeutics. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ciara Kelly (Novartis) for assisting in the preparation of the tables and figures.

Mihai Gheorghiade (chair), Gerasimos Filippatos (co‐chair), John G.F. Cleland, Sean P. Collins, Carolyn Lam Su Ping, Christiane E. Angermann, Georg Ertl, Ulf Dahlström, Dayi Hu, Kenneth Dickstein, Sergio V. Perrone, and Mathieu Ghadanfar are members of the steering committee for the REPORT‐HF registry.

The copyright line for this article was changed on 14 March 2015 after original online publication.

References

- 1. Adams KF Jr, Fonarow GC, Emerman CL, LeJemtel TH, Costanzo MR, Abraham WT, Berkowitz RL, Galvao M, Horton DP. Characteristics and outcomes of patients hospitalized for heart failure in the United States: rationale, design, and preliminary observations from the first 100,000 cases in the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE). Am Heart J 2005;149:209–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gheorghiade M, Abraham WT, Albert NM, Greenberg BH, O'Connor CM, She L, Stough WG, Yancy CW, Young JB, Fonarow GC. Systolic blood pressure at admission, clinical characteristics, and outcomes in patients hospitalized with acute heart failure. JAMA 2006;296:2217–2226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Steinberg BA, Zhao X, Heidenreich PA, Peterson ED, Bhatt DL, Cannon CP, Hernandez AF, Fonarow GC. Trends in patients hospitalized with heart failure and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction: prevalence, therapies, and outcomes. Circulation 2012;126:65–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cleland JG, Swedberg K, Follath F, Komajda M, Cohen‐Solal A, Aguilar JC, Dietz R, Gavazzi A, Hobbs R, Korewicki J, Madeira HC, Moiseyev VS, Preda I, van Gilst WH, Widimsky J, Freemantle N, Eastaugh J, Mason J. The EuroHeart Failure survey programme—a survey on the quality of care among patients with heart failure in Europe. Part 1: patient characteristics and diagnosis. Eur Heart J 2003;24:442–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nieminen MS, Brutsaert D, Dickstein K, Drexler H, Follath F, Harjola VP, Hochadel M, Komajda M, Lassus J, Lopez‐Sendon JL, Ponikowski P, Tavazzi L. EuroHeart Failure Survey II (EHFS II): a survey on hospitalized acute heart failure patients: description of population. Eur Heart J 2006;27:2725–2736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Maggioni AP, Dahlstrom U, Filippatos G, Chioncel O, Leiro MC, Drozdz J, Fruhwald F, Gullestad L, Logeart D, Metra M, Parissis J, Persson H, Ponikowski P, Rauchhaus M, Voors A, Nielsen OW, Zannad F, Tavazzi L. EURObservational Research Programme: the Heart Failure Pilot Survey (ESC‐HF Pilot). Eur J Heart Fail 2010;12:1076–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Maggioni AP, Anker SD, Dahlstrom U, Filippatos G, Ponikowski P, Zannad F, Amir O, Chioncel O, Leiro MC, Drozdz J, Erglis A, Fazlibegovic E, Fonseca C, Fruhwald F, Gatzov P, Goncalvesova E, Hassanein M, Hradec J, Kavoliuniene A, Lainscak M, Logeart D, Merkely B, Metra M, Persson H, Seferovic P, Temizhan A, Tousoulis D, Tavazzi L. Are hospitalized or ambulatory patients with heart failure treated in accordance with European Society of Cardiology guidelines? Evidence from 12,440 patients of the ESC Heart Failure Long‐Term Registry. Eur J Heart Fail 2013;15:1173–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sato N, Kajimoto K, Asai K, Mizuno M, Minami Y, Nagashima M, Murai K, Muanakata R, Yumino D, Meguro T, Kawana M, Nejima J, Satoh T, Mizuno K, Tanaka K, Kasanuki H, Takano T. Acute decompensated heart failure syndromes (ATTEND) registry. A prospective observational multicenter cohort study: rationale, design, and preliminary data. Am Heart J 2010;159:949–955 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Atherton JJ, Hayward CS, Wan Ahmad WA, Kwok B, Jorge J, Hernandez AF, Liang L, Kociol RD, Krum H. Patient characteristics from a regional multicenter database of acute decompensated heart failure in Asia Pacific (ADHERE International‐Asia Pacific). J Card Fail 2012;18:82–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lam CS, Anand I, Zhang S, Shimizu W, Narasimhan C, Park SW, Yu CM, Ngarmukos T, Omar R, Reyes EB, Siswanto B, Ling LH, Richards AM. Asian Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure (ASIAN‐HF) registry. Eur J Heart Fail 2013;15:928–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Follath F, Yilmaz MB, Delgado JF, Parissis JT, Porcher R, Gayat E, Burrows N, McLean A, Vilas‐Boas F, Mebazaa A. Clinical presentation, management and outcomes in the Acute Heart Failure Global Survey of Standard Treatment (ALARM‐HF). Intensive Care Med 2011;37:619–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Damasceno A, Mayosi BM, Sani M, Ogah OS, Mondo C, Ojji D, Dzudie A, Kouam CK, Suliman A, Schrueder N, Yonga G, Ba SA, Maru F, Alemayehu B, Edwards C, Davison BA, Cotter G, Sliwa K. The causes, treatment, and outcome of acute heart failure in 1006 Africans from 9 countries. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:1386–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Blaha MJ, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Franco S, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER 3rd, Moy CS, Mussolino ME, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Pandey DK, Paynter NP, Reeves MJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2014;129:e28–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Heidenreich PA, Albert NM, Allen LA, Bluemke DA, Butler J, Fonarow GC, Ikonomidis JS, Khavjou O, Konstam MA, Maddox TM, Nichol G, Pham M, Pina IL, Trogdon JG, American Heart Association Advocacy Coordinating Committee, Council on Arteriosclerosis Thrombosis and Vascular Biology, Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, Stroke Council. Forecasting the impact of heart failure in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Heart Fail 2013;6:606–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McMurray JJ, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, Auricchio A, Bohm M, Dickstein K, Falk V, Filippatos G, Fonseca C, Gomez‐Sanchez MA, Jaarsma T, Kober L, Lip GY, Maggioni AP, Parkhomenko A, Pieske BM, Popescu BA, Ronnevik PK, Rutten FH, Schwitter J, Seferovic P, Stepinska J, Trindade PT, Voors AA, Zannad F, Zeiher A, Bax JJ, Baumgartner H, Ceconi C, Dean V, Deaton C, Fagard R, Funck‐Brentano C, Hasdai D, Hoes A, Kirchhof P, Knuuti J, Kolh P, McDonagh T, Moulin C, Reiner Z, Sechtem U, Sirnes PA, Tendera M, Torbicki A, Vahanian A, Windecker S, Bonet LA, Avraamides P, Ben Lamin HA, Brignole M, Coca A, Cowburn P, Dargie H, Elliott P, Flachskampf FA, Guida GF, Hardman S, Iung B, Merkely B, Mueller C, Nanas JN, Nielsen OW, Orn S, Parissis JT, Ponikowski P. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail 2012;14:803–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Roger VL, O'Donnell CJ. Population health, outcomes research, and prevention: example of the American Heart Association 2020 goals. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2012;5:6–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hu SS, Kong LZ, Gao RL, Zhu ML, Wang W, Wang YJ, Wu ZS, Chen WW, Liu MB. Outline of the report on cardiovascular disease in China, 2010. Biomed Environ Sci 2012;25:251–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sakata Y, Shimokawa H. Epidemiology of heart failure in Asia. Circ J 2013;77:2209–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Huffman MD, Prabhakaran D. Heart failure: epidemiology and prevention in India. Natl Med J India 2010;23:283–288. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Okura Y, Ramadan MM, Ohno Y, Mitsuma W, Tanaka K, Ito M, Suzuki K, Tanabe N, Kodama M, Aizawa Y. Impending epidemic: future projection of heart failure in Japan to the year 2055. Circ J 2008;72:489–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Callender T, Woodward M, Roth G, Farzadfar F, Lemarie JC, Gicquel S, Atherton J, Rahimzadeh S, Ghaziani M, Shaikh M, Bennett D, Patel A, Lam CS, Sliwa K, Barretto A, Siswanto BB, Diaz A, Herpin D, Krum H, Eliasz T, Forbes A, Kiszely A, Khosla R, Petrinic T, Praveen D, Shrivastava R, Xin D, MacMahon S, McMurray J, Rahimi K. Heart failure care in low‐ and middle‐income countries: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. PLoS Med 2014;11:e1001699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. AlHabib KF, Elasfar AA, AlBackr H, AlFaleh H, Hersi A, AlShaer F, Kashour T, AlNemer K, Hussein GA, Mimish L. Design and preliminary results of the heart function assessment registry trial in Saudi Arabia (HEARTS) in patients with acute and chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2011;13:1178–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Agarwal AK, Venugopalan P, de Bono D. Prevalence and aetiology of heart failure in an Arab population. Eur J Heart Fail 2001;3:301–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ambrosy AP, Fonarow GC, Butler J, Chioncel O, Greene SJ, Vaduganathan M, Nodari S, Lam CS, Sato N, Shah AN, Gheorghiade M. The global health and economic burden of hospitalizations for heart failure: lessons learned from hospitalized heart failure registries. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:1123–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Filippatos G, Farmakis D, Bistola V, Karavidas A, Mebazaa A, Maggioni AP, Parissis JT. Temporal trends in epidemiology, clinical presentation and management of acute heart failure: results from the Greek cohorts of the Acute Heart Failure Global Registry of Standard Treatment and the European Society of Cardiology‐Heart Failure pilot survey. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2014; in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.EuroQol—a new facility for the measurement of health‐related quality of life. Health Policy 1990;16:199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Green CP, Porter CB, Bresnahan DR, Spertus JA. Development and evaluation of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire: a new health status measure for heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;35:1245–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Reilly MC, Bracco A, Ricci JF, Santoro J, Stevens T. The validity and accuracy of the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment questionnaire—irritable bowel syndrome version (WPAI:IBS). Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004;20:459–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Humphrey L, Kulich K, Deschaseaux C, Blackburn S, Maguire L, Stromberg A. The Caregiver Burden Questionnaire for Heart Failure (CBQ‐HF): face and content validity. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2013;11:84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Blair JE, Zannad F, Konstam MA, Cook T, Traver B, Burnett JC, Jr. , Grinfeld L, Krasa H, Maggioni AP, Orlandi C, Swedberg K, Udelson JE, Zimmer C, Gheorghiade M. Continental differences in clinical characteristics, management, and outcomes in patients hospitalized with worsening heart failure results from the EVEREST (Efficacy of Vasopressin Antagonism in Heart Failure: Outcome Study with Tolvaptan) program. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:1640–1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mentz RJ, Cotter G, Cleland JG, Stevens SR, Chiswell K, Davison BA, Teerlink JR, Metra M, Voors AA, Grinfeld L, Ruda M, Mareev V, Lotan C, Bloomfield DM, Fiuzat M, Givertz MM, Ponikowski P, Massie BM, O'Connor CM. International differences in clinical characteristics, management, and outcomes in acute heart failure patients: better short‐term outcomes in patients enrolled in Eastern Europe and Russia in the PROTECT trial. Eur J Heart Fail 2014;16:614–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pitt B, Pfeffer MA, Assmann SF, Boineau R, Anand IS, Claggett B, Clausell N, Desai AS, Diaz R, Fleg JL, Gordeev I, Harty B, Heitner JF, Kenwood CT, Lewis EF, O'Meara E, Probstfield JL, Shaburishvili T, Shah SJ, Solomon SD, Sweitzer NK, Yang S, McKinlay SM. Spironolactone for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1383–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McMurray JJ, O'Connor C. Lessons from the TOPCAT trial. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1453–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Greene SJ, Shah AN, Butler J, Ambrosy AP, Anker SD, Chioncel O, Collins SP, Dinh W, Dunnmon PM, Fonarow GC, Lam CS, Mentz RJ, Pieske B, Roessig L, Rosano GM, Sato N, Vaduganathan M, Gheorghiade M. Designing effective drug and device development programs for hospitalized heart failure: a proposal for pretrial registries. Am Heart J 2014;168:142–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]