Abstract

The functional properties of a protein primarily depend on its three-dimensional (3D) structure. These properties have classically been assigned, visualized and analysed on the basis of protein secondary structures. The β-turn is the third most important secondary structure after helices and β-strands. β-turns have been classified according to the values of the dihedral angles φ and ψ of the central residue. Conventionally, eight different types of β-turns have been defined, whereas those that cannot be defined are classified as type IV β-turns. This classification remains the most widely used. Nonetheless, the miscellaneous type IV β-turns represent 1/3rd of β-turn residues. An unsupervised specific clustering approach was designed to search for recurrent new turns in the type IV category. The classical rules of β-turn type assignment were central to the approach. The four most frequently occurring clusters defined the new β-turn types. Unexpectedly, these types, designated IV1, IV2, IV3 and IV4, represent half of the type IV β-turns and occur more frequently than many of the previously established types. These types show convincing particularities, in terms of both structures and sequences that allow for the classical β-turn classification to be extended for the first time in 25 years.

The functional properties of a protein primarily depend on its three-dimensional (3D) structure. These properties have classically been assigned, visualized and analysed on the basis of protein secondary structures, which are composed of repetitive parts (α-helices1 represent 1/3rd of residues, and β-strands2 represent 1/5th of residues) connected by coils3. This simplification of 3D structure into a unidimensional representation of secondary structure is often regarded as a resolved question. In fact, this simplification conceals the difficulty of precisely defining and assigning repetitive structures4, thus explaining the large number of alternative assignment approaches5,6,7,8,9,10,11. For instance, comparison of different approaches emphasizes their major discrepancies12,13. Another limitation of this type of simplification is that the coil state is neglected, although it represents almost 50% of all residues and a large set of distinct local protein structures. Loop analyses cannot provide a complete representation of the coil state because their classification is usually limited to 8 residues4,14,15,16,17. More precise descriptions are needed to comprehensively describe their diversity.

Helical and extended regions are the most frequently occurring repetitive structures. However, two other local protein conformations have also been characterized: the polyproline II helix and turns. The former is a left-handed helical structure with an overall shape resembling a triangular prism. It represents 5% of all protein residues18, contributes to coiled coil super secondary structure formation and is present in fibrous proteins19,20. Because polyproline II helices do not have strong hydrogen bond patterns, they have not been studied in as much detail as the other local conformations21,22,23,24,25,26.

Turns comprise n consecutive residues (denoted i to i+n), in which the distance between Cα(s) of residues i and i+n must be smaller than 7 Å (or 7.5 Å, according to some authors27,28). The turns are composed of γ-turns (n = 3)29,30, β-turns (n = 4), α-turns (n = 5)31,32 and π-turns (n = 6)33,34. The restrictive distance between Cαs applies a particular geometry to the backbone, thereby causing it to turn back on itself.

β-turns have been the most analysed among the turn conformations. Apart from the distance between Cαs, a second rule applies to the characterization of their secondary structure; because helices can easily be confused with a succession of turns, the central residues of β-turns, i.e., i+1 and i+2, should not be helical. Similarly, β-turn residues must not consist solely of β-strand residues. β-turns have been classified according to the values of their central residue dihedral angles, φ and ψ. A deviation of ± 30° from these canonical values is allowed on 3 of these angles, whereas the fourth can deviate by ± 45°35.

The β-turns, as defined by C.M. Venkatachalam, are characterized by a hydrogen bond between the N-H and C = O of residues i and i+336. Venkatachalam has also defined types I, II, and III, and their corresponding mirror image types, I’, II’ and III’36. Crawford and collaborators have proposed a more strict definition in terms of distance37. Lewis and co-workers have added types V and V’. β-turn type VI is characterized by the presence of a proline; type VII is associated with a kink; and type IV corresponds to all other non-classified β-turns38. Different turns have been excluded for various reasons: β-turns III and III’ are too close to the 310-helix and types I and I’, whereas turns V, V’ and VII are rare, and their definitions are inaccurate35. Type VI is divided into 2 sub-types, VIa and VIb. Hutchinson and Thornton39 have divided type VIa into the 2 sub-types VIa1 and VIa2. Wilmot and Thornton have precisely defined type VIII40, which is based on Richardson’s type Ib and was proposed after the removal of type VII35. The definitions used by Thornton’s group39,41 are currently considered to be the standard (see Supplementary Information 1)42. The β-turn assignment program PROMOTIF assigns β-turns on the basis of these standards43. Studies have shown that repetitive structure assignment approaches have a direct effect on decreasing or increasing the number of residues associated with β-turns27,28.

The difficulty with using such an approach is the ‘strict’ rule(s) used to define the β-turn types. Efimov has used a Ramachandran plot simplified to 6 and 8 regions: β (βE and βP), γ, δ, α, ε and αL (αL and γL). This rough clustering allows various classes to be defined, with some being associated with amino acid specific behaviours. The turns are also divided into full turns (with a polypeptide chain reversal of 180°) and half turns (with a polypeptide chain angle of 90°). The first category represents 7 major clusters, and the second one represents 8 major clusters44,45. This system has widely been used to define super-secondary elements46,47 and structural trees of protein superfamilies48,49,50. In a similar way, Wilmot and Thornton have also used a simplification of the Ramachandran plot for the following 6 major regions: βE, βP, αR, ε, αL and γL51. They observed 12 combinations in their dataset. The most frequent turns were easily detected, whereas the two most interesting non-classical turns were βE → γL (8%) and γL → αR (4%). The 6 other clusters represented only 1% each51.

More recently, Koch and Klebe have proposed a combination of turns of different lengths ranging from 3 to 6 residues; the turns sometimes overlap, thus leading to complex categorizations52. Koch and Klebe trained a very large modified Self-Organizing Map53,54 and extracted new types from the map. The assignment is provided as part of Secbase, an extension module of Relibase55. Koch and Klebe have used the identified new types in a second step to perform a prediction from the sequence56. This approach is innovative, but it has not been implemented as a web tool and is therefore less used. George Rose’s group has conducted research with a focus on the rationalization of two-, three-, and four-residue turn conformations found in their coil library57. Rose’s group has defined 12 categories and has used them in Monte-Carlo simulations. These categories cover at least 90% of coil library fragments ranging from 5- to 20-residues, thus indicating that longer fragments are composites of shorter ones58. Rose’s group has extended this approach to redraw the Ramachandran plot59.

However, none of these approaches has succeeded in superseding the classical definition of β-turns35,36,41,43. A major shortcoming of past β-turn classification concerns the classification of type IV β-turns, i.e., the miscellaneous category, because it represents 1/3rd of β-turn residues and is the second most common type of β-turn. To locate potentially new recurrent conformations in this miscellaneous type, an automatic clustering approach based on the rules of β-turn assignment was designed. It is related to Self-Organizing Maps53,54 and takes into account the specificity of β-turn assignment rules. All type IV β-turns were clustered. The four most occurring clusters were chosen as new types and analysed. Unexpectedly, these sub-types, denoted IV1, IV2, IV3 and IV4, represent half of the type IV β-turns and occur more frequently than many of the classical types.

Methods

Data sets

To remove representative bias regarding protein resolution or sequence identity, non-redundant datasets were used. These datasets were generated using the PISCES database60. As previously performed in12,61, 10 sets of proteins were defined. Each contained no more than x% pairwise sequence identity (with x ranging from 20 to 90%). The selected chains had X-ray crystallographic resolutions less than 1.6 Å or 2.5 Å and R-factors less than 0.25 or 1.0. They comprised between 2,542 and 23,943 protein chains. Each chain was automatically examined with geometric criteria to avoid bias from zones with missing density. The main purpose of such diversity was to examine (i) the poorly populated turns and (ii) the stability of the clustering approach (see below).

Secondary structure assignment

Secondary structure assignment was performed with DSSP5 (CMBI version 2000) using the default parameters. DSSP yields more than three states, so we reduced them to the following: the α-helix, containing α, 310 and π-helices; the β-strand, containing only the β-sheet; and the coil, comprising everything else (β-bridge, hydrogen bond turn, bend, and coil). Turn assignment was performed as described previously27,28,36 using the following classical rules: the distance between residues i and i+3 should be less than 7 Å; the central residues of the turns must be non-helical; and in the case of strands, at least one residue must be associated with a coil. The types of turns (I, I’, II, II’, VIa1, VIa2, VIb and VIII) were assigned according to the classical definition by using the φ and ψ dihedral angles of the central residues (see Supplementary Information 1). The turns were required to be less than 30° from the canonical values (at most one angle was allowed to deviate by +/− 45°)43. Types VIa1, VIa2 and VIb were characterized by a cis-proline at position i+2. Turns that did not fit any of the above criteria were classified as type IV39,43. The turns were also classified into two classes according to their function as described by Efimov44,45: full turns resulting in a chain reversal of 180° and half turns that change the polypeptide chain direction by approximately 90°. This methodology was used to enable comparisons with previous studies.

Protein Blocks

Protein Blocks (PBs62,63) corresponded to a set of 16 local prototypes, labelled from a to p, of 5 residue length that were described on the basis of dihedral angles (φ, ψ). The PBs were obtained with an unsupervised classifier similar to Kohonen Maps54 and hidden Markov models64. The PBs m and d are prototypes for the central regions of α-helix and β-strands respectively. PBs a through c primarily represent the N-cap of a β-strand, whereas e and f correspond to the C-caps; PBs g through j are specific to coils, PBs k and l correspond to the N cap of an α-helix, and PBs n through p correspond to C-caps. PBs were assigned by using in-house Python software, although similar assignment can be performed through the PBE web server65 or PBxplore (https://github.com/pierrepo/PBxplore66).

Specific clustering approach

A specific clustering approach was designed to cluster type IV β-turns by using the classical rule, allowing +/− 30° for all angles, with the exception of one at +/− 45° for the defined values. The clustering derived from Self-Organizing Maps (SOM, without diffusion between the clusters53,54). The training was carried out in 2 successive parts; the first one limited the potential bias of initialization, and the second refined the clustering by using the specific rules for β-turn types. The type IV β-turns were selected from a dataset D. Thus, each dataset was associated with T type IV β-turns.

Step one:

1. k clusters were created and were vectors v of length 2M = 4, representing the dihedral angles (φi+1, ψi+1, φi+2, and ψi+2). k type IV β-turns were taken randomly to initialize the clusters.

2. One of the T type IV β-turns was randomly selected from the dataset D (denoted V2) and compared with each of the k clusters.

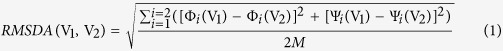

The dissimilarity measure between two vectors V1 (representing the clusters) and V2 of dihedral angles was defined as the Euclidean distance among the M links, the RMSDA (root mean square deviations on angular values67):

|

where {Φi(V1), Ψi(V1)}(resp. Ψi(V2), Ψi(V2)) denotes the series of the (2M) dihedral angles for V1 (resp. V2). The angle differences were computed modulo 360°. Thus, in the training, this distance was used for assessing the dissimilarity of any fragment in the database with the different clusters.

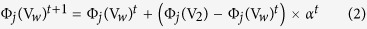

3. The minimal RMSDA value was used to define the winning cluster W, i.e., the closest to the observation. W values were modified according to the learning coefficient α:

|

|

where {Φj(Vw)} and Ψj(Vw) are the values of the winner at time t, with j ranging from 1 to 2, similar to the values of the real data (i.e., dihedral angles i+1 and i+2, modulo 360°).

|

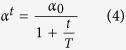

The decrease of α was performed similarly to that for SOM53,54, T represents the total amount of data to learn (here the number of type IV β-turns). t represents the number of β-turns already used. The process goes back to step 2. One cycle of training corresponds to the learning of the whole dataset α0, which is then equal to α0/2; after 5 cycles, it is equal to α0/5, etc. Initially, α0 = 0.35, as in68,69.

The process was iterated for 20 cycles, i.e., 20 times T; these steps were important to diminish the potential effect of the initialization.

Step two:

The final values of the k clusters were used as initial values. α0 was still equal to 0.35.

One of the T type IV β-turns was randomly selected from the dataset D (denoted V2) and compared with each of the k clusters. Instead of using only RMSDA, the β-turn rule was used: 3 angles can be at +/− 30° and 1 angle at +/− 45°.The winner positively applied this rule; otherwise no training was performed.

Modification of the winner weights was performed as in step one −3.

The process was iterated for 20 cycles.

An important point is the choice of k. k was first set at 50 and then reduced. The obtained clusters were compared in the order of largest to smallest k values.

Z-score

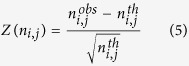

The amino acid occurrences for each local structure conformation were normalized into a Z-score:

|

where is the observed number of occurrences of amino acid i in position j for a given secondary structure, and

is the observed number of occurrences of amino acid i in position j for a given secondary structure, and  is the expected number. The product of the occurrences in position j with the frequency of amino acid i in the entire databank equals

is the expected number. The product of the occurrences in position j with the frequency of amino acid i in the entire databank equals  . Positive Z-scores (respectively negative) corresponded to overrepresented amino acids (respectively underrepresented); threshold values of 4.42 and 1.96 were chosen (probability less than 10−5 and 5.10−2, respectively). The same computation was also performed for the protein blocks.

. Positive Z-scores (respectively negative) corresponded to overrepresented amino acids (respectively underrepresented); threshold values of 4.42 and 1.96 were chosen (probability less than 10−5 and 5.10−2, respectively). The same computation was also performed for the protein blocks.

Analysis

Most of the quantitative analysis was performed using in-house Python scripts, and statistics and visualization were performed with R software (version 3.2.2)70.

Results and Discussion

Protein structure dataset

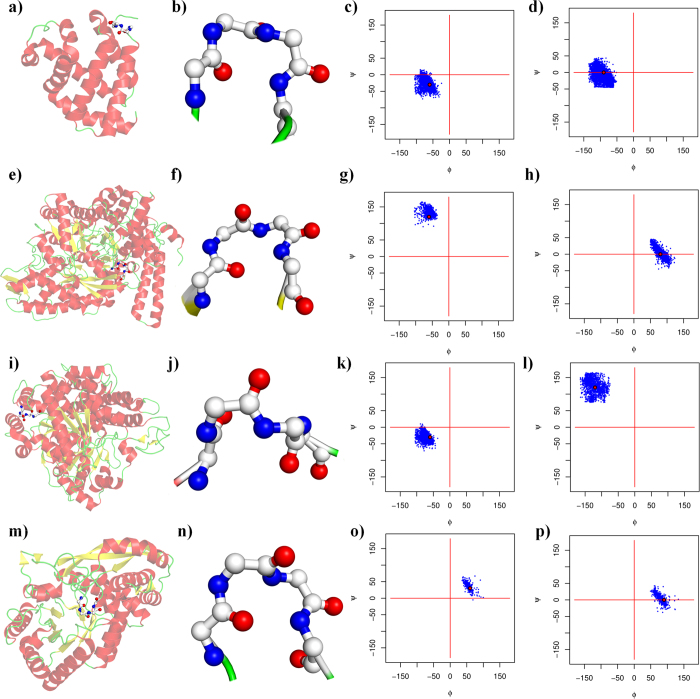

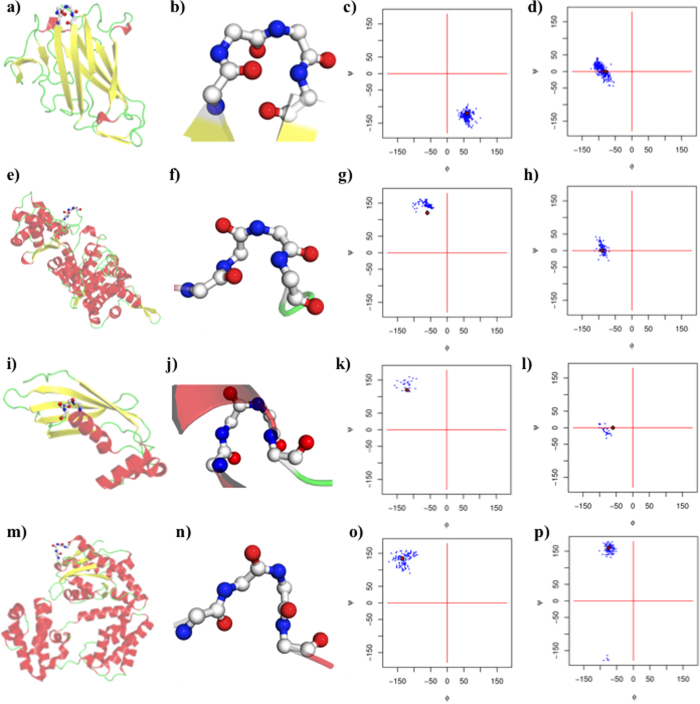

The different amino acid datasets showed the expected amino acid and protein block occurrences, with no peculiarities in the rate of redundancy and the resolution quality (see Supplementary Information 2). As noted previously27,28, the occurrence of β-turns is highly dependent on the way in which the assignment is performed. Following the work of Fuchs and Alix27, we assigned secondary structures to the different protein datasets by using DSSP5. The DSSP provided 8 classes that were reduced to 3 classes (helix, strand and coil) or 4 classes (helix, strand, turn and coil, see Supplementary Information 3) for practicality. Helical structures represented more than 37.3% of the residues and the β-sheets represented 22.5%, whereas the remaining coil class covered 42.7% of the residues and included 20.4% of the β-turns (11.9% were turns and 8.5% were bends). Our β-turn assignment in the coil regions provided a slightly different number, with 21.9% being β-turns (difference: 1.5%). In total, 71.8% were similar to the DSSP assignment (45.6% were turns, and 23.0% were bends), whereas 28.1% and 1.9% were associated with coils and bridges, respectively. These proportions were comparable to the results of previous studies27,28. The β-turn types were then assigned by using classical definitions (described in the methods section, see Supplementary Information 1). Type I β-turns were the most frequent (38.2%), followed by the miscellaneous type IV (31.7%), and types II (11.8%), VIII (9.8%), I’ (4.1%), II’ (2.5%) and the different sub-types of the type VI β-turns (ranging from 0.9 to 0.2%, see Table 1). Henceforth, the type IV β-turns will be denoted type IVori to differentiate them from the new types in the current analyses. Figures 1 and 2 show the different types of β-turns in 3D and the distribution of their dihedral angles in the Ramachandran plot36,71,72.

Table 1. β-turn frequencies.

| β-turn | (%) |

|---|---|

| I | 38.21 |

| II | 11.81 |

| VIII | 9.84 |

| I' | 4.10 |

| II' | 2.51 |

| VIb | 0.88 |

| VIa1 | 0.73 |

| VIa2 | 0.20 |

| IVori | 31.72 |

| Sum | 100.00 |

Classical types and their frequencies. Type VIa1, VIa2 and VIb β-turns are characterized by a cis-proline at position i+2. Type IV is denoted IVori to distinguish it from the new classification.

Figure 1. β-turn representation (beginning).

(a–d) Type I, (e–h) type II, (i–l) type VIII, and (m–p) type I’ A turn close to the ideal values of its type (a,e,i,m) within a protein and (b,f,j,n) a close-up of the turn. Type I is represented by PDB id 2BK985, type II by PDB id 1H1686, type VIII by PDB id 1SU887 and type I’ by PDB id 1KKO88. (c,g,k,o) Ramachandran plot (φ, ψ) of residue i+1 and (d,h,l,p) of residue i+2; red dots are the ideal values. The number of observations of both residues is strictly identical.

Figure 2. β-turn representation (end).

(a–d) Type II’, (e–h) type VIa1, (i–l) type VIa2, and (m–p) type VIb (see Fig. 1 for legend). Type II’ is represented by PDB id 1UXA89, type VIa1 by PDB id 1HBN90, type VIa2 by PDB id 1IQ691, and type VIb by PDB id 1YT392.

Analyses of discarded types

As a first step, before searching for new types, the previously discarded types were analysed.

Notably, type III and III’ β-turns had been included by Venkatachalam36, but have been discarded because they are considered to be too close to the 310 helices and to type I (and I’) β-turns. The type V β-turn has been considered to be a rather unusual departure from the type II β-turn (see Figures 35 and 36 of ref. 35). If the type III β-turn were still recognized, it would represent 9.6% of the residues; i.e., it would be the third most frequently occurring type. The obsolete type III’ β-turn represented approximately 1.5% of the turns, whereas the type V and V’ β-turns represented only 0.03 and 0.02%, respectively (see Supplementary Information 4), and were associated with type IV β-turns (see Supplementary Information 5), but they were negligible.

For the type III and III’ β-turns, the overlap with type I and I’ β-turns remained as expected, with 88.7% of the type III β-turns assigned as type I β-turns, 87.6% of the type III’ β-turns assigned as type I’ β-turns (see Supplementary Information 4 and 6), and the remaining 11–12% associated with type IV β-turns. Interestingly, 60% of type I β-turns were also assignable to type III, and 83.9% of type I’ were assignable to type III’ (see Supplementary Information 7). Therefore, the decision to remove this particular definition was clearly reasonable.

Searching for new types

From the above section, it is apparent that nearly 1/3rd of residues are not associated with a defined type. Moreover, as presented in the methods section, learning was performed on the type IV β-turns, the clustering was conducted on the basis of dihedral angles with an unsupervised approach similar to the approaches used for protein blocks62,67. The first step of learning was entirely unsupervised and was performed to properly define the initial values of the clusters, whereas the second step dictated the specific rules of the β-turns (e.g., +/−30° and one dihedral angle at +/− 45°).

A major difficulty in every classification approach is the choice of the clusters. Here, it was slightly different; the idea was not to have an optimal number of clusters but to assess the most frequently occurring and recurrent clusters to define the new pertinent types. In related research, Micheletti and collaborators have decided to take the largest cluster each time and iteratively repeat the clustering, each time removing the largest cluster73. This clustering is slightly unstable because each repetition removes a large amount of data. Thus, it did not seem pertinent to use it here. Moreover, with a large initial number of clusters, determining the clusterability of the data was manageable.

The training was performed with different datasets beginning with a large number of clusters (50 at first), which was progressively reduced (to 10). A notable feature of the learning was that four clusters appeared at the beginning and remained the most frequently occurring cluster for each of the different datasets. The deviation in the dihedral angle values between the different simulations (and different datasets) was never higher than 0.3°, thus indicating that the clustering was reasonably stable (a more detailed description is provided in Supplementary Information 8).

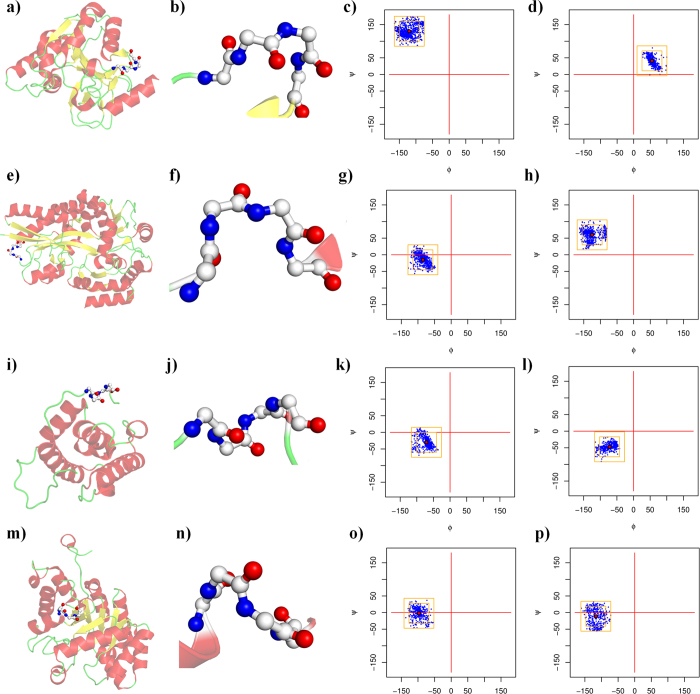

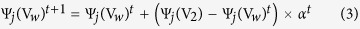

The four new type IV β-turn sub-types were named IV1, IV2, IV3 and IV4. They represent half of the of type IV β-turns (see Table 2), composing 16.1, 12.4, 11.2 and 8.5% of the IVori type, respectively. In regards to all of the defined types, they were the 4th, 6th, 7th and 8th most frequent turns (5.10%, 3.9%, 3.5% and 2.7%, respectively). These numbers are reasonable because they were highly consistent across all of the datasets. Figure 3 shows these four new categories. The remaining clusters were not selected because (i) their occurrences were very low (largely less than those of type VI β-turns) and (ii) they were often dependent on the number of clusters (see Supplementary Information 9). They were not useful for either protein structure or sequence–structure relationship analyses. The rest of the type IV β-turns were classified as IVmisc.

Table 2. β-turn frequencies.

| new β-turn | (%) | (%) of β-turn IVori |

|---|---|---|

| IV1 | 5.10 | 16.08 |

| IV2 | 3.95 | 12.44 |

| IV3 | 3.53 | 11.15 |

| IV4 | 2.70 | 8.50 |

| IVmisc | 16.44 | 51.83 |

| Sum | 31.72 | 100.00 |

The four new β-turns are denoted IV1 to IV4, and the remaining residues are assigned to type IVmisc. Their frequencies in regards to the turns and to the original type IVori are provided.

Figure 3. New β-turn representation.

(a–d) Type IV1, (e–h) type IV2, (i–l) type IV3, and (m–p) type IV4 (see Fig. 1 for legend). Type IV1 is represented by PDB id 1JYK93, type IV2 by PDB id 1URS94, type IV3 by PDB id 1PA795, and type IV4 by PDB id 1QWG96.

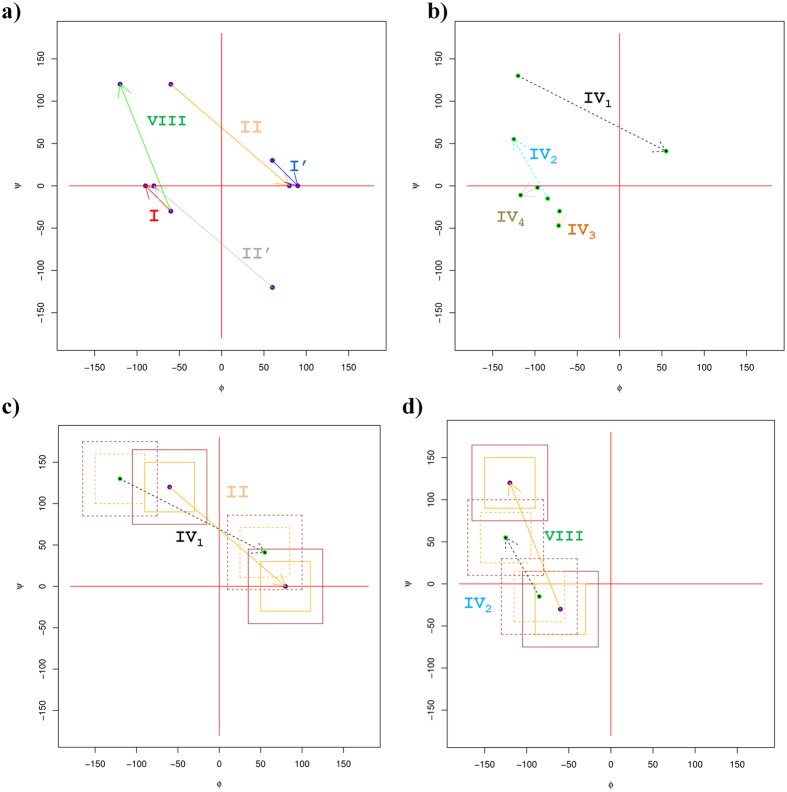

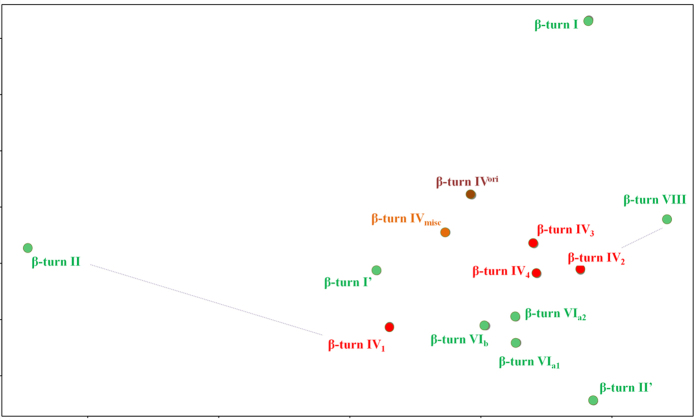

Table 3 provides the observed angles. Because the clustering approach was based on the specific clustering of type IV, no overlap could be found with the existing types. Figures 4a,b show the relative position of each turn. A relationship was observed between type IV1 and type II β-turns (see Fig. 4c) and between type IV2 and VIII β-turns (see Fig. 4d, see Supplementary Information 10). In terms of dihedral angle values, the type IV1 β-turn resembled a slightly displaced conformation of the type II β-turn, whereas the type IV2 β-turn appeared to be a less extended type VIII β-turn. Type IV3 and IV4 were much more specific, with very particular dihedral angles in the helical regions (see Supplementary Information 11).

Table 3. New β-turns.

| β-turn | φi+1 | ψi+1 | φi+2 | ψi+2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type IV1 | −120.0 | 130.0 | 55.0 | 41.0 |

| Type IV2 | −85.0 | −15.0 | −125.0 | 55.0 |

| Type IV3 | −71.0 | −30.0 | −72.0 | −47.0 |

| Type IV4 | −97.0 | −2.0 | −117.0 | −11.0 |

Dihedral angle values of the four new turns.

Figure 4. Ramachandran plot of the different β-turn types.

An arrow connects the dihedral angle values of residue i+1 to residue i+2. (a) Classical β-turns, (b) new β -turns, (c) a close-up of type II and IV1 β -turns, and (d) on type VIII and IV2 β -turns, the first square corresponds to the +/− 30° rule, and the second one to the +/− 45° rule.

New turns in regards to DSSP

To describe the type IV β-turns more precisely, we examined their former DSSP assignments (hydrogen bond estimation) as turns or bends. Interestingly, more than 2/3 of the residues of IVori were identified by DSSP as turns, with 35% being bends and 37% being hydrogen bond turns, and the rest were mainly associated with coils and β-sheets. The type IVmisc was more associated with non-hydrogen bond, stabilized local structures, with a 41% enrichment in bends and 31% fewer hydrogen bond turns. This evolution is mainly associated with the newer and less frequent type IV β-turns (e.g., type IV3 and IV4), which comprise 70% and 49% hydrogen bond turns. The evolution was strikingly lower for the type IV1 β-turn, with less than 30% of residues associated with hydrogen bond turns. Although all the new type IV β-turns were linked to neither α-helices nor β-sheets, type IV1 β-turns were often observed at the ends of β-sheets (in nearly 2/3 of the cases).

Comparison with previous analyses

As mentioned in the introduction, two major efforts were made in the 1980 s and 1990 s to define β-turns. Both were based on a Ramachandran plot divided into 6 to 8 large regions. The size and shape of these regions were largely different from the strict rule of +/−30° (and 45°). Notably, these previous classifications were performed with all turns, whereas in the current analyses the classification was performed on only a subset of type IV β-turns.

Table 4 shows the new turns classified using a Ramachandran plot division scheme similar to that described above. Efimov has proposed a very precise definition of turns and half-turns with 7 and 8 types of turn44,45. Interestingly, type IV1 might seem as if it could be characterized as βEαL because it looks like the proposed βαL-half-turn; however, the type IV1 β-turn is not a half-turn but a complete turn. The type IV3 β-turn is the only local conformation that can be described as a half-turn, but instead of being a αγ-half-turn, it is mainly α/γ- > α. Type IV4 β-turns can be described as γγ; a similar type has been described in45, but here it is mainly a turn, whereas the previously described types were half-turns. In fact, the type IV2 β-turns were the only ones that seemed to be directly related to Efimov’s analyses, because they could be characterized by a γδ connection between α-helices, as described in45. The percentage of turns and half-turns observed correctly correlated with the distance threshold proposed by Crawford and co-workers37.

Table 4. Torsion angle regions taken from Wilmot and Thornton, and Efimov, with turns and half-turn proportions as defined by Efimov and distance in regards to Crawford.

| Thornton (1990) |

Efimov (1986) |

Efimov (1986) |

Crawford (1973) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| i+1 | i+2 | i+1 | i+2 | turns | half-turns | d < 5.7 Å | |

| β-turn IV1 | βE | αL | βE | αL | 99.4 | 0.6 | 23 |

| β-turn IV2 | αR | βE | ϒ | δ | 72 | 28 | 37 |

| β-turn IV3 | αR | αR | ϒ/α | α | 71 | 29 | 54 |

| β-turn IV4 | αR | αR | ϒ | ϒ | 65 | 35 | 28 |

| β-turn IVmisc | 64 | 36 | 19 | ||||

Wilmot and Thornton have also used a simplification of the Ramachandran plot in 6 major regions, with 12 combinations51. Because the size of the different regions is higher than Efimov’s, the number of types is relatively limited. The region αR represents the γ, δ and α regions; very diverse conformations were found in type IV3 and IV4 β-turns as well as type I β-turns (i.e., αR → αR). Type IV2 β-turns had the same description as type VIII (i.e., αR → βE). Interestingly, only two non-classical turns, βE → γL (8%) and γL → αR (4%)51, were defined by Wilmot and Thornton. One could expect that one of these two types might be associated with the most frequent new turn. However, this was not the case, because the type IV1 β-turn is not βE → γL, but βE → αL.

Hence, these comparisons illustrate that the specific clustering performed in the current analyses highlighted one new main cluster that was not observed previously: the type IV1 β-turn. Additionally, it showed the specificity of the type IV3 and IV4 β-turns in regards to their fine description. The type IV2 β-turn was the only one to have been clearly characterized previously by both studies45,51.

Koch and Klebe (KK) used a sophisticated approach to unify the assignment of turns of different lengths52. This approach is not easily comparable to others because: (i) it is not based on the classical assignment rules and (ii) all the turns have been re-assigned. Hence, for β-turns, other features were used in the training in addition to the values of the dihedral angles (φ, ψ) of the central residue. Classical and new β-turns were compared to the final definition of the 24 open KK β -turns (7 were considered to be non-turn-like structures) and 18 reverse KK β–turns presented in Supplemental Data S14 and S16 of ref. 52. Owing to the particular learning method, type I’, II and II’ β-turns had no direct equivalent in the KK β-turns, whereas type I, IV3 and IV4 β-turns were associated with the KK type I β-turn (18% of the true turns). Type VIII β-turns were associated with the KK type VIII3 β-turn (6.5% of the true turns). Interestingly, type IV2 β-turns were not associated with any KK β-turn types.

Hence, this comparison between studies indicated some similarities because the major turn (type I β-turn) could not distinguish between the two new less frequent turns (types IV3 and IV4 β-turn), whereas type VIII β-turns were easily found by using this approach. Similarly to previous results, the type IV2 β-turn remained specific to our clustering. However, differences between the studies should be taken into account, such as the different learning method used by Koch and Klebe, considered more angles than ours and their training was conducted on the complete set of turns and not just the type IV β-turns.

Comparison with protein blocks

Table 5 shows the over- and under-representation of protein blocks for all the β-turn types. Type IVori β-turns were characterized by a PB motif of [efghijko] [bhijklno] [abghijlnop] [acgiop]. As expected, this signature was more ambiguous in regards to the well-defined types, which showed a range of only one to four PBs at each position. The IVmisc represented only half of the previous β-turn IVori types. The only exception was the newly over-represented PBs n and p at positions i and i+1 as well as the reduced over-representation of PBs n and p at positions i+1 and i+3, whereas 28/32 over-representations remained the same.

Table 5. Protein blocks’ Z-scores of β-turn types.

| i | i+1 | i+2 | i+3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-turn I | (+) | FJKL | KLN | BGLOP | CGOP |

| (−) | aBCDEGHIMNOP | ABCDEFGHIJMOP | ACDEFHIJKM | ABDEFHIjKL | |

| β-turn II | (+) | EG | HO | IK | AL |

| (−) | aBCDFHjKLMnOP | ABCDEFgIjKLMNP | ABCDEFghjLMnO | BCDEFghiKMNoP | |

| β-turn VIII | (+) | AFKP | ABL | CDGL | bCFK |

| (−) | BCDEgHMNO | CDEFgHIjKMNop | aBefhIjKMnoP | ADIjLMnoP | |

| β-turn I' | (+) | EGHjNO | HO | IP | A |

| (−) | bcDfklMp | abcDefklM | bcDefhkMo | bcDefhklMp | |

| β-turn II' | (+) | abHO | J | ABLO | CGLP |

| (−) | DfM | abcDfkMo | cDfkmp | adkm | |

| β-turn VIa1 | (+) | Cdp | EF | BHK | BIL |

| (−) | fkM | dkM | cdflM | ckM | |

| β-turn VIa2 | (+) | Bi | aeFg | BK | gjlo |

| (−) | m | m | m | m | |

| β-turn VIb | (+) | bCdj | aCD | Df | bDf |

| (−) | fkM | fklM | klM | clM | |

| β-turn IVori | (+) | EFGHiJKO | BHIJKLNO | ABGhIjLNOP | ACGiOP |

| (−) | BCDM | CDFM | CDeFkM | DEfklM | |

| β-turn IV1 | (+) | AEGp | aEGHo | HIKP | AIL |

| (−) | cDfhklMo | bcDfklMnp | abcDflMo | cDkMnp | |

| β-turn IV2 | (+) | FJKL | BKLno | bGLP | Cg |

| (−) | bcDehmop | CDFghiMp | acDeFhiKm | aDeiL | |

| β-turn IV3 | (+) | FjK | KL | BLmNo | cGMnOp |

| (−) | bCDehinop | abCDeFhiop | aCDeFhik | abDeFhikl | |

| β-turn IV4 | (+) | FJK | KLN | BGLOP | CGoP |

| (−) | bDehmno | acDfhiMp | acDefhikM | abDefhiklm | |

| β-turn IVmisc | (+) | EFGHIjkNO | BHIJLNOP | ABGIJLnOP | AbCgjP |

| (−) | bCDM | CDeFM | cDfkM | DeM |

The newly defined type IV β-turns had stronger PB motifs. They could be analysed not only in regards to β-turn IVori but also in regards to II and VIII for types IV1 and IV2.

For type IV1, the PB motif is [aegp] [aegho] [hikp] [ail] and has no direct contradiction with the classical behaviours of β-turn IVori. However, this motif had some interesting specificities in regards to type IV2. However, the PB motifs of type II β-turns were less ambiguous, with only two main PBs at each position [eg] [ho] [ik] [al]. Type IV1 β-turns were clearly different, with 8 over-represented PBs that were under-represented in type II β-turns (PBs a and p at position i, PBs a, e and g at position i+1, PBs h and p at position i+2 and PBs i at position i+3). Similarly, in type IV2 β-turns, the PB motif was [fjkl] [bklno] [bglp] [cg] and was comparable to the type IVori β-turns but also had some differences compared with the type VIII β-turns. Hence, only half of the over-represented PBs in type VIII β-turn were found in type IV2 β-turns and 5 under-represented PBs were over-represented (PBs k, n and p at position i+1, and PBs b and p at position i+2).

PB motifs of type IV3 and IV4 β-turns were mainly associated with the most frequent β-turn, the type I β-turn, because their dihedral angles were in the same restricted area.

Amino Acid Specificities of the new types

β-turns have been widely analysed in terms of sequence – structure relationships, which have been incorporated in various prediction approaches27,74,75. Table 6 shows the under- and over-represented amino acids in each type of turn. Some associations were expected because all of the different type VI β-turns were characterized by the proline at position i+2.

Table 6. Amino acid’s Z-score of β-turn types.

| i | i+1 | i+2 | i+3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-turn I | (+) | cPghStND | PSEK | whSTNDe | wcGn |

| (−) | IVLmAfywQERK | IVLmFywcqGhtn | IVLmAPG | ivlmqPErk | |

| β-turn II | (+) | qP | Pek | GN | mcqSt |

| (−) | sD | ivLywcGst | IVLmAFywqPSTdERK | ilPgn | |

| β-turn VIII | (+) | acPGs | PDek | IVFyhNd | ivP |

| (−) | Ivlmqerk | ilfycGh | lAPG | lafGe | |

| β-turn I' | (+) | Fst | GNd | Gn | yqr |

| (−) | Q | ivpt | ivlapsterk | p | |

| β-turn II' | (+) | St | G | stN | mg |

| (−) | Vlafqpter | P | ivlp | ||

| β-turn VIa1 | (+) | Vp | afYp | P | fyg |

| (−) | ilt | ip | |||

| β-turn VIa2 | (+) | N | ne | P | h |

| (−) | |||||

| β-turn VIb | (+) | P | Y | P | pr |

| (−) | G | ivlagstderk | |||

| β-turn IVori | (+) | CPGStnD | PGsndk | gHtND | PGTn |

| (−) | IVlaqerk | IVLmAc | IVLaqP | ivLAdek | |

| β-turn IV1 | (+) | cG | hnek | GhND | cpG |

| (−) | Ve | g | ivlaptk | d | |

| β-turn IV2 | (+) | PgS | pstDk | hND | P |

| (−) | Ivlmrk | ivafg | ivlPG | vladek | |

| β-turn IV3 | (+) | CsnD | aP | vmt | fystn |

| (−) | Ivak | cq | pg | iqe | |

| β-turn IV4 | (+) | Cpgsnd | fptnD | whtNd | fGh |

| (−) | Vle | ivag | lpg | pek | |

| β-turn IVmisc | (+) | cPgnd | PGn | GhtNd | pgTn |

| (−) | Ivlar | iVLmAfc | ivLay | vla |

Colors underline the difference of new turns and the original type IVori (underline new over- or under representation, in bold italics inversion of over- or under representation, see Methods section).

Concerning the new turns defined in the current analyses, the four important points are as follows:

Type IVori and IVmisc β-turns remained strongly linked, because erasing half of the occurrences did not change the general trend of the unassigned turns.

IV3 and IV4 were clearly distinct in terms of dihedral angle distributions but had very similar amino acid compositions. Indeed, they shared the same over- or underrepresented amino acid trends in 80% of the cases; only one inversion of amino acid preference was observed for the type IV3 β-turns at position i+2 (alanine),

The type VIII and IV2 β-turns were structurally close, with high sequence similarity. We found only one inversion between these types at position i+2 for the valine residue.

Interestingly, the type IV1 and II β-turns were close structurally but had strongly divergent sequences. At position i, no common amino acid over- or under-representation was observed. In the Ramachandran plot’s αL region, glycine represented 88% of the residues, whereas in γL, it was only 38% (with N 17%, D 9%, K 5%, E and R 4%, respectively). Interestingly, the type IV1 encompassed mainly the non-glycine residues at i+2 (see Table 4). Moreover, proline and glycine residues were under-represented at position i+3 of type II, although they were over-represented in type VIII β-turns. Additionally, the i+2 positions of both types had more divergent residues. Figure 5 shows a Sammon map projection76 of all the β-turns. It emphasizes these relationships and highlights the strong differences between types IV1 and II, with the distance being quite substantial. The type IV1 β-turn amino acid composition was similar to that of the two other new β-turn types, IV3 and IV4 (see Supplementary Information 12 and 13).

Figure 5. Sammon map of amino acid behaviours of the different β-turns.

Classical turns are in green while new turns are in red.

Conclusions

β-turns are the most important secondary structures preceded by the α-helix and β-sheet. β-turns correspond to approximately 25 to 30% of all protein residues77. The current classification of the different β-turns has remained unchanged for the past 30 years. In the 1980 s and 1990 s, different studies proposed extending the definition of turns, mainly on the basis of the division of a Ramachandran plot into 6 to 8 regions46,51,78. These analyses of β-turns showed strong similarities with classical analyses and provided new definitions for the least frequently occurring turns. Two recent studies have expressed interest in redefining the definitions: (i) Koch and Klebe52 have used a very large modified Self-Organizing Map53,54 and (ii) George Rose’s group has defined 12 categories comprising different lengths57,58. Nonetheless, these approaches were performed in a manner comparable to the secondary structure assignment that is still dominated by DSSP5. Although different turn classifications have subsequently been proposed9, none of them have been successfully used. The main idea in this study was not to redraw a novel classification but to extend the classical classification.

From an unsupervised classification, based exclusively on dihedral angles, four new types were defined. The two most frequently occurring, type IV1 and IV2 β-turns, were similar to existing type II and VIII β-turns but had very distinct features. On the one hand, type IV2 and VIII β-turns shared striking amino acid compositional features, with minor differences. However, type IV2 β-turns were associated with stabilizing hydrogen bonds, unlike type VIII β-turns. On the other hand, type IV1 and II β-turns were very close in terms of dihedral angles but were distinct in terms of their amino acid content. Figure 5 clearly shows that type II β-turns were highly specific, whereas type IV1 β-turns had more classical characteristics, being closer to type I’ β-turns than type II β-turns.

The two remaining β-turn types, IV3 and IV4, were within bin 6 of the Ramachandran plot, close to type I β-turns79. Although their amino acid profiles were highly similar, their local protein structure conformations were distinct.

A classical question raised by any clustering methodology is the relevance of the results. Here, our results can be considered reliable, owing to their reproducibility and stability. The use of 10 different datasets ranging in quality and sequence identity highlighted the high stability of the four main clusters (i.e., the new turns). For each simulation, the clusters were always found at similar frequencies and with similar dihedral values. However, the other clusters were substantially more variable. A simple analysis was also performed to evaluate the possibility of the presence of sub-clusters inside the different clusters by diminishing the authorized dihedral angle deviation allowed during the training. Similarly, the centre of the four main clusters always appeared, thus supporting their stability.

Comparisons with the previous alternative classification proposed by Efimov45,78 and Thornton’s group51 emphasized the uniqueness of the approach. Notably, the most frequent new turn (type IV1 β-turn) was not highlighted, although it is the 5th most occurring turn (including type IVmisc β-turns). Only the type IV2 β-turns were previously included.

This extended classification is relevant because it does not modify the currently accepted β-turn types, is highly stable (in regards to amino acid redundancy and the quality of protein resolution), and proposes new ways to analyse the architecture and dynamics of the protein or peptide structure of β-turns. Hence, we envision two potential applications of this classification system. The first one addresses molecular dynamics simulations in which researchers follow the dynamic evolution of type VIII β-turns80. The change from type VIII to a type IV (i.e., IVori) during the simulations is very different when the turn is in fact a type IV2 or IVmisc. The former case (type IV2 β-turn) is a simple extension of this conformation, whereas the latter (type IVmisc β-turn) is really a different independent conformation80. The second example involves an analysis of conformational characteristics of asparaginyl residues in proteins81. Interestingly, many are associated with turn conformations. With this new classification, only 16.5% (see Supplementary Information 14) were associated with miscellaneous turns (e.g., IVmisc); thus, this classification provides a better description of local protein conformations and resolves the spectrum of IVmisc turns to a greater extent.

An interesting point is that turns are often observed as tandem repeats, sometimes leading to long series of γβ, βγ, ββ or γγ turns82. It is also notable that γ and β turns are associated with the same residues83,84. In future work, we plan to investigate the succession of turns, particularly the ones mentioned in this study.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: de Brevern, A.G. Extension of the classical classification of β-turns. Sci. Rep. 6, 33191; doi: 10.1038/srep33191 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

I thank the editor and anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments, which helped me improve the manuscript. This work came from various trips and discussions I had during recent years in Bangalore, India, and I would like to dedicate this research to Indian protein pioneers G.N. Ramachandran, C. Ramakrishnan, C.M. Venkatachalam, P. Balaram, N. Srinivasan and R. Sowdhamini and also to my colleagues C. Etchebest, P.F.J. Fuchs, J.-C. Gelly, and especially T.J. Narwani. This work was supported by grants from the French Ministry of Research, University of Paris Diderot – Paris 7, French National Institute for Blood Transfusion (INTS), French Institute for Health and Medical Research (INSERM). AdB also acknowledges the Indo-French Centre for the Promotion of Advanced Research/CEFIPRA for collaborative grants (numbers 3903-E and 5302-2). This study was supported by grants from the Laboratory of Excellence GR-Ex, reference ANR-11-LABX-0051. The labex GR-Ex is funded by the programme “Investissements d’avenir” of the French National Research Agency, reference ANR-11-IDEX-0005-02. Calculations were performed on an SGI cluster granted by Conseil Régional Ile de France and INTS (SESAME Grant).

Footnotes

Author Contributions A.G.d.B. designed and performed experiments, analysed data and wrote the paper.

References

- Pauling L., Corey R. B. & Branson H. R. The structure of proteins; two hydrogen-bonded helical configurations of the polypeptide chain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 37, 205–211 (1951). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauling L. & Corey R. B. The pleated sheet, a new layer configuration of polypeptide chains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 37, 251–256 (1951). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg D. The discovery of the alpha-helix and beta-sheet, the principal structural features of proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100, 11207–11210 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fourrier L., Benros C. & de Brevern A. G. Use of a structural alphabet for analysis of short loops connecting repetitive structures. BMC Bioinformatics 5, 58 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch W. & Sander C. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers 22, 2577–2637 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fodje M. N. & Al-Karadaghi S. Occurrence, conformational features and amino acid propensities for the pi-helix. Protein Eng 15, 353–358 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin J. et al. Protein secondary structure assignment revisited: a detailed analysis of different assignment methods. BMC structural biology 5, 17 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinig M. & Frishman D. STRIDE: a web server for secondary structure assignment from known atomic coordinates of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 32, W500–502, 10.1093/nar/gkh429 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offmann B., Tyagi M. & de Brevern A. G. Local Protein Structures. Current Bioinformatics 3, 165–202 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Klose D. P., Wallace B. A. & Janes R. W. 2Struc: the secondary structure server. Bioinformatics 26, 2624–2625, 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq480 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calligari P. A. & Kneller G. R. ScrewFit: combining localization and description of protein secondary structure. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 68, 1690–1693, 10.1107/S0907444912039029 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyagi M., Bornot A., Offmann B. & de Brevern A. G. Analysis of loop boundaries using different local structure assignment methods. Protein Sci 18, 1869–1881, 10.1002/pro.198 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruus E., Thumfort P., Tang C. & Wingreen N. S. Gibbs sampling and helix-cap motifs. Nucleic Acids Res 33, 5343–5353, 33/16/534366 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wintjens R., Wodak S. J. & Rooman M. Typical interaction patterns in alphabeta and betaalpha turn motifs. Protein Eng 11, 505–522 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojcik J., Mornon J. P. & Chomilier J. New efficient statistical sequence-dependent structure prediction of short to medium-sized protein loops based on an exhaustive loop classification. J Mol Biol 289, 1469–1490 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutonnet N. S., Kajava A. V. & Rooman M. J. Structural classification of alphabetabeta and betabetaalpha supersecondary structure units in proteins. Proteins 30, 193–212 (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonet J. et al. ArchDB 2014: structural classification of loops in proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 42, D315–319, gkt1189 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansiaux Y., Joseph A. P., Gelly J. C. & de Brevern A. G. Assignment of PolyProline II conformation and analysis of sequence--structure relationship. PLoS One 6, e18401, 10.1371/journal.pone.0018401 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauling L. & Corey R. B. The structure of fibrous proteins of the collagen-gelatin group. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 37, 272–281 (1951). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan P. M., McGavin S. & North A. C. The polypeptide chain configuration of collagen. Nature 176, 1062–1064 (1955). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adzhubei A. A. & Sternberg M. J. Left-handed polyproline II helices commonly occur in globular proteins. J Mol Biol 229, 472–493 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creamer T. P. Left-handed polyproline II helix formation is (very) locally driven. Proteins 33, 218–226 (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapley B. J. & Creamer T. P. A survey of left-handed polyproline II helices. Protein Sci 8, 587–595 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creamer T. P. & Campbell M. N. Determinants of the polyproline II helix from modeling studies. Adv Protein Chem 62, 263–282 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chellgren B. W. & Creamer T. P. Short sequences of non-proline residues can adopt the polyproline II helical conformation. Biochemistry 43, 5864–5869 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adzhubei A. A., Sternberg M. J. & Makarov A. A. Polyproline-II helix in proteins: structure and function. J Mol Biol 425, 2100–2132, S0022-2836(13)00166-6 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs P. F. & Alix A. J. High accuracy prediction of beta-turns and their types using propensities and multiple alignments. Proteins 59, 828–839 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornot A. & de Brevern A. G. Protein beta-turn assignments. Bioinformation 1, 153–155. (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews B. W. the gamma-turn. Evidence for a new folded conformation in Proteins.. Macromolecules 5, 818–819 (1972). [Google Scholar]

- Milner-White E. J. Situations of gamma-turns in proteins. Their relation to alpha-helices, beta-sheets and ligand binding sites. J Mol Biol 216, 386–397 (1990). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nataraj D., Srinivasan N., Sowdhamini R. & Ramakrishnan C. Alpha-turns in pro tein structures. Curr. Sci. 69, 434–447 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Pavone V. et al. Discovering protein secondary structures: classification and description of isolated alpha-turns. Biopolymers 38, 705–721 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta B. & Chakrabarti P. pi-Turns: types, systematics and the context of their occurrence in protein structures. BMC Struct Biol 8, 39, 1472-6807-8-39 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajashankar K. R. & Ramakumar S. Pi-turns in proteins and peptides: Classification, conformation, occurrence, hydration and sequence. Protein Sci 5, 932–946 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson J. S. The anatomy and taxonomy of protein structure. Adv Protein Chem 34, 167–339 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatachalam C. M. Stereochemical criteria for polypeptides and proteins. V. Conformation of a system of three linked peptide units. Biopolymers 6, 1425–1436 (1968). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford J. L., Lipscomb W. N. & Schellman C. G. The reverse turn as a polypeptide conformation in globular proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 70, 538–542 (1973). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis P. N., Momany F. A. & Scheraga H. A. Chain reversals in proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta 303, 211–229 (1973). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson E. G. & Thornton J. M. A revised set of potentials for beta-turn formation in proteins. Protein Sci 3, 2207–2216 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilmot C. M. & Thornton J. M. Analysis and prediction of the different types of beta-turn in proteins. J Mol Biol 203, 221–232 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan A. W., Hutchinson E. G., Harris D. & Thornton J. M. Identification, classification, and analysis of beta-bulges in proteins. Protein Sci 2, 1574–1590 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nataraj D. V., Srinivasan N. & Sowdhamini R. & Ramakrishnan, C. β - turns in protein structures. Curr. Sci. 69, 434–447 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson E. G. & Thornton J. M. PROMOTIF–a program to identify and analyze structural motifs in proteins. Protein Sci 5, 212–220 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efimov A. V. [Standard conformations of a polypeptide chain in irregular protein regions]. Mol Biol (Mosk) 20, 250–260 (1986). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efimov A. V. Standard structures in proteins. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 60, 201–239 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efimov A. V. Super-secondary structures involving triple-strand beta-sheets. FEBS Lett 334, 253–256 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efimov A. V. Super-secondary structures and modeling of protein folds. Methods Mol Biol 932, 177–189, 10.1007/978-1-62703-065-6_11 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efimov A. V. Structural trees for protein superfamilies. Proteins 28, 241–260 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efimov A. V. A structural tree for proteins containing 3beta-corners. FEBS Lett 407, 37–41 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordeev A. B., Kargatov A. M. & Efimov A. V. PCBOST: Protein classification based on structural trees. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 397, 470–471, 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.05.136 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilmot C. M. & Thornton J. M. Beta-turns and their distortions: a proposed new nomenclature. Protein Eng 3, 479–493 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch O. & Klebe G. Turns revisited: a uniform and comprehensive classification of normal, open, and reverse turn families minimizing unassigned random chain portions. Proteins 74, 353–367, 10.1002/prot.22185 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohonen T. Self-organized formation of topologically correct feature maps. Biol. Cybern 43, 59–69 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- Kohonen T. Self-Organizing Maps (3rd edition). (Springer, 2001). [Google Scholar]

- Koch O., Cole J., Block P. & Klebe G. Secbase: database module to retrieve secondary structure elements with ligand binding motifs. J Chem Inf Model 49, 2388–2402, 10.1021/ci900202d (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner M., Koch O., Klebe G. & Schneider G. Prediction of turn types in protein structure by machine-learning classifiers. Proteins 74, 344–352, 10.1002/prot.22164 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzkee N. C., Fleming P. J. & Rose G. D. The Protein Coil Library: a structural database of nonhelix, nonstrand fragments derived from the PDB. Proteins 58, 852–854 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perskie L. L. & Rose G. D. Physical-chemical determinants of coil conformations in globular proteins. Protein Sci 19, 1127–1136, 10.1002/pro.399 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter L. L. & Rose G. D. Redrawing the Ramachandran plot after inclusion of hydrogen-bonding constraints. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108, 109–113, 1014674107 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G. & Dunbrack R. L. Jr. PISCES: a protein sequence culling server. Bioinformatics 19, 1589–1591 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyagi M., Bornot A., Offmann B. & de Brevern A. G. Protein short loop prediction in terms of a structural alphabet. Comput Biol Chem 33, 329–333, S1476-9271(09)00051-6 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Brevern A. G., Etchebest C. & Hazout S. Bayesian probabilistic approach for predicting backbone structures in terms of protein blocks. Proteins 41, 271–287 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph A. P. et al. A short survey on protein blocks. Biophys Rev 2, 137–145 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabiner L. R. A tutorial on hidden Markov models and selected application in speech recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE 77, 257–286 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- Tyagi M. et al. Protein Block Expert (PBE): a web-based protein structure analysis server using a structural alphabet. Nucleic Acids Res 34, W119–123 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulain P. PBxplore: A program to explore protein structures with Protein Blocks. Technical report. (2016) Available at: https://github.com/pierrepo/PBxplore. (Accessed: 21st June 2016).

- Schuchhardt J., Schneider G., Reichelt J., Schomburg D. & Wrede P. Local structural motifs of protein backbones are classified by self-organizing neural networks. Protein Eng 9, 833–842 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Brevern A. G. & Hazout S. ‘Hybrid protein model’ for optimally defining 3D protein structure fragments. Bioinformatics 19, 345–353 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esque J., Urbain A., Etchebest C. & de Brevern A. G. Sequence-structure relationship study in all-alpha transmembrane proteins using an unsupervised learning approach. Amino Acids 47, 2303–2322, 10.1007/s00726-015-2010-510.1007/s00726-015-2010-5 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihaka R. & Gentleman, R. R: A Language for Data Analysis and Graphics. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics 5, 299–314 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran G. N., Ramakrishnan C. & Sasisekharan V. Stereochemistry of polypeptide chain configurations. J Mol Biol 7, 95–99 (1963). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan C. & Ramachandran G. N. Stereochemical criteria for polypeptide and protein chain conformations. II. Allowed conformations for a pair of peptide units. Biophys J 5, 909–933, S0006-3495(65)86759-5 (1965). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micheletti C., Seno F. & Maritan A. Recurrent oligomers in proteins: an optimal scheme reconciling accurate and concise backbone representations in automated folding and design studies. Proteins 40, 662–674 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou P. Y. & Fasman G. D. Prediction of beta-turns. Biophys J 26, 367–383, S0006-3495(79)85259-5 (1979). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh H., Singh S. & Raghava G. P. In silico platform for predicting and initiating beta-turns in a protein at desired locations. Proteins 83, 910–921, 10.1002/prot.24783 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sammon J. A nonlinear mapping for data structure analysis. IEEE Transactions on Computers 18, 401–409. (1969). [Google Scholar]

- Guruprasad K. & Rajkumar S. Beta-and gamma-turns in proteins revisited: a new set of amino acid turn-type dependent positional preferences and potentials. J Biosci 25, 143–156 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efimov A. V. [Standard structures in protein molecules. II. Beta-alpha hairpins]. Mol Biol (Mosk) 20, 340–345 (1986). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmankar N. V., Ramakrishnan C. & Balaram P. Sparsely populated residue conformations in protein structures: revisiting “experimental” Ramachandran maps. Proteins 82, 1101–1112, 10.1002/prot.24384 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs P. F. et al. Kinetics and thermodynamics of type VIII beta-turn formation: a CD, NMR, and microsecond explicit molecular dynamics study of the GDNP tetrapeptide. Biophys J 90, 2745–2759, S0006-3495(06)72457-2 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan N., Anuradha V. S., Ramakrishnan C., Sowdhamini R. & Balaram P. Conformational characteristics of asparaginyl residues in proteins. Int J Pept Protein Res 44, 112–122 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guruprasad K., Prasad M. S. & Kumar G. R. Analysis of gammabeta, betagamma, gammagamma, betabeta continuous turns in proteins. J Pept Res 57, 292–300 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guruprasad K., Prasad M. S. & Kumar G. R. Analysis of gammabeta, betagamma, gammagamma, betabeta multiple turns in proteins. J Pept Res 56, 250–263 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guruprasad K., Rao M. J., Adindla S. & Guruprasad L. Combinations of turns in proteins. J Pept Res 62, 167–174 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Sanctis D. et al. Bishistidyl heme hexacoordination, a key structural property in Drosophila melanogaster hemoglobin. J Biol Chem 280, 27222–27229, 10.1074/jbc.M503814200 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker A. & Kabsch W. X-ray structure of pyruvate formate-lyase in complex with pyruvate and CoA. How the enzyme uses the Cys-418 thiyl radical for pyruvate cleavage. J Biol Chem 277, 40036–40042, 10.1074/jbc.M205821200 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbek H., Svetlitchnyi V., Liss J. & Meyer O. Carbon monoxide induced decomposition of the active site [Ni-4Fe-5S] cluster of CO dehydrogenase. J Am Chem Soc 126, 5382–5387, 10.1021/ja037776v (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy C. W. et al. Insights into enzyme evolution revealed by the structure of methylaspartate ammonia lyase. Structure 10, 105–113 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burmeister W. P., Guilligay D., Cusack S., Wadell G. & Arnberg N. Crystal structure of species D adenovirus fiber knobs and their sialic acid binding sites. J Virol 78, 7727–7736, 10.1128/JVI.78.14.7727-7736.2004 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabarse W. et al. On the mechanism of biological methane formation: structural evidence for conformational changes in methyl-coenzyme M reductase upon substrate binding. J Mol Biol 309, 315–330, 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4647 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hisano T. et al. Crystal structure of the (R)-specific enoyl-CoA hydratase from Aeromonas caviae involved in polyhydroxyalkanoate biosynthesis. J Biol Chem 278, 617–624, 10.1074/jbc.M205484200 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo Y., Wang Y. & Malhotra A. Crystal structure of Escherichia coli RNase D, an exoribonuclease involved in structured RNA processing. Structure 13, 973–984, 10.1016/j.str.2005.04.015 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak B. Y. et al. Structure and mechanism of CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase (LicC) from Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Biol Chem 277, 4343–4350, 10.1074/jbc.M109163200 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer K. et al. X-ray structures of the maltose-maltodextrin-binding protein of the thermoacidophilic bacterium Alicyclobacillus acidocaldarius provide insight into acid stability of proteins. J Mol Biol 335, 261–274 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi I. & Ikura M. Crystal structure of the amino-terminal microtubule-binding domain of end-binding protein 1 (EB1). J Biol Chem 278, 36430–36434, 10.1074/jbc.M305773200 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise E. L., Graham D. E., White R. H. & Rayment I. The structural determination of phosphosulfolactate synthase from Methanococcus jannaschii at 1.7-A resolution: an enolase that is not an enolase. J Biol Chem 278, 45858–45863, 10.1074/jbc.M307486200 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.