Abstract

To examine national changes in rates of cost-related prescription nonadherence (CRN) by age group, we used data from the 1999–2015 Sample Adult and Sample Child National Health Interview Surveys (n = 768 781). In a logistic regression analysis of 2015 data, we identified subgroups at risk for cost-related nonadherence.

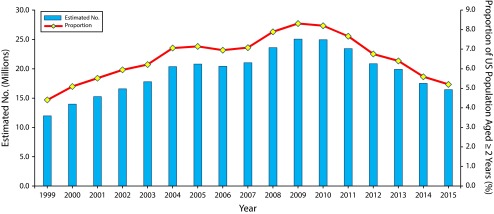

The proportion of all Americans who did not fill a prescription in the previous 12 months because they could not afford it grew from 1999 to 2009, peaking at 8.3% at the height of the Great Recession and dropping to 5.2% by 2015. CRN among seniors, however, peaked in 2004 at 5.4% and dropped to 3.6% after implementation of Medicare Part D in 2006.

CRN is responsive to improved access related to implementation of Medicare Part D and the Affordable Care Act.

The failure to take medications as prescribed is consistently linked to the exacerbation of chronic conditions, increased health care use, and greater health system costs.1 One of the most common causes of nonadherence is also the most obvious—medications are often expensive, and many people cannot afford to fill their prescriptions.2 Much of the published research on cost-related nonadherence (CRN) has focused on Medicare,3–6 but comparative studies indicate that CRN is most common among the uninsured7,8 and is associated with a variety of individual factors other than insurance status.9

Our research shows that, at the peak of the Great Recession in 2009, approximately 25.1 million Americans reported that, during the previous 12 months, they did not fill a prescription because they could not afford it. The prevalence of CRN declined after 2010, coinciding with an improving US economy and implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA; Pub L No. 111–148), but changes varied by age group. We tracked changes in CRN prevalence from 1999 to 2015 and identified individual-level factors associated with CRN before (2013) and after (2015) ACA implementation.

METHODS

We analyzed data from the National Health Interview Survey, a continuing probability survey of households conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics.10 Trend data came from the 1999–2015 sample adult and sample child surveys (n = 768 781), and we drew more detailed CRN information from 2013 and 2015 sample adult surveys (n = 93 494). All reported prevalence estimates use National Center for Health Statistics population weights based on the 1990, 2000, or 2010 decennial census.

For our trend analyses, we defined CRN as a “yes” response to the question, “During the past 12 months, was there any time when you needed a prescription medication but didn’t get it because you couldn’t afford it?” To assess the impact of ACA implementation, we also compared responses in 2013 and 2015 to a new National Health Interview Adult Survey question: “Regarding prescription medications, during the past 12 months did you do any of the following to save money?” Possible responses were (1) skip doses, (2) take less medicine, and (3) delay filling a prescription. We considered those 2015 respondents who answered “yes” to any of these 3 responses or who responded “yes” to the question about failing to fill a prescription owing to cost (yes: n = 3260; no: n = 30 412), and we used this aggregate measure as the dependent variable in a logistic regression model.

RESULTS

Figure 1 shows changes in the estimated number and proportion of Americans (aged 2 years or older) who did not fill a prescription in the previous 12 months because they could not afford it. These rates peaked in 2009, at 8.3% of the population, and dropped to 5.2% by 2015.

FIGURE 1—

Population Estimates and Prevalence Rates of Cost-Related Nonadherence: United States, 1999–2015

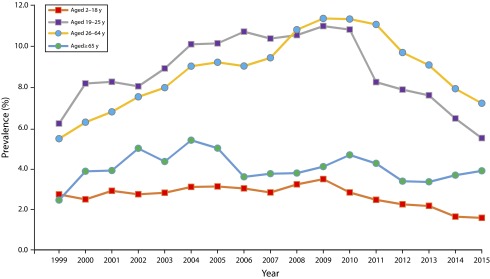

Figure 2 breaks out CRN trends by age group. Rates rose across age groups from 1999 to 2009, with 1 notable exception: CRN peaked among seniors (aged 65 years or older) at 5.4% in 2004, immediately following passage of the Medicare Modernization Act, and dropped to 3.6% in 2006 after full implementation of Medicare Part D. CRN rates among seniors rose again between 2007 and 2010 but dropped thereafter as the ACA provided a phased reduction of cost sharing and closure of the Part D coverage gap, with additional discounts, rebates, and subsidies for seniors.

FIGURE 2—

Prevalence Rates of Cost-Related Nonadherence by Age Group: United States, 1999–2015

Throughout the observation period, paying for prescriptions was a much bigger problem for working-aged adults (19–64 years) than for seniors. By 2009, an estimated 21 million working-aged adults (11.3%) reported being unable to fill a prescription because of the cost. As economic conditions slowly improved after 2010, CRN rates among working-aged adults began to decline. However, the slope of this decline was initially much steeper for 1 segment of this population: younger adults (19–25 years).

This drop coincides with an important policy change. In 2010, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services enacted 1 of the first components of the ACA: new regulations allowed young adults to stay on their parents’ health insurance plans until aged 26 years. In the following year, CRN rates among adults aged 19 to 25 years dropped from 10.8% to 8.2%. By contrast, rates for adults aged 26 to 64 years in the same period dropped only from 11.3% to 11.1%.

In 2014, the ACA established health insurance marketplaces in each state, expanded Medicaid coverage in 27 states, and classified prescription drugs as an essential health benefit.11 These policy changes coincided with a steep overall drop in CRN in the working-age population, particularly among adults aged 26 to 64 years (from 9.1% in 2013 to 7.2% by 2015).

Table 1 offers further evidence of a significant decline in rates of CRN across multiple measures after ACA implementation. In 2013, about 26.5 million adults (11.2%) reported not filling a prescription, postponing a prescription fill, taking less medication than prescribed, or skipping doses of a medication to save money, but this dropped to 22.0 million (9.1%) by 2015.

TABLE 1—

Change in Proportions of Cost-Related Nonadherence (CRN): United States Adults, 2013–2015

| Cost-Related Nonadherence Measures | 2013, Estimated No.a (%) | 2015, Estimated No.a (%) | Change Between 2013 and 2015, % |

| In the past 12 mo, did you | |||

| Not fill a prescription because you couldn’t afford it? | 18.4 (7.8) | 15.2 (6.4) | −18.8*** |

| Delay filling a prescription to save money? | 15.3 (6.5) | 12.0 (4.9) | −23.5*** |

| Take less medicine than prescribed to save money? | 12.0 (5.0) | 9.8 (4.1) | −18.7*** |

| Skip medication doses to save money? | 11.3 (4.7) | 9.2 (3.8) | −19.9*** |

| Any CRN: yes to 1 or more of the above questions | 26.5 (11.2) | 22.0 (9.1) | −18.8*** |

Source. 2013 and 2015 Sample Adult and Core National Health Interview Surveys (2015).

Numbers in millions.

P < .001; P values determined by Wald χ2.

The multivariate logistic model in Table 2 uses this combined 2015 CRN measure as the dependent variable and confirms that factors previously associated with CRN remain predictive in the post-ACA era. Consistent with previous research, CRN is significantly more common among working-aged adults, women, African Americans, residents of the Southern and Midwestern regions (including most of the states that opted out of the Medicaid expansion), the uninsured, Medicaid and Medicare enrollees, those who describe their health as fair or poor, and persons with disabilities.9

TABLE 2—

Odds Ratios of Cost-Related Nonadherence (CRN): United States Adults, 2015

| Population Attributes | Estimated Total No.a | Estimated CRN No.a | CRN Rate, % | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

| Total population aged ≥ 18 y | 239.7 | 23.4 | 9.8 | |

| Age, y | ||||

| 18–25 | 34.4 | 2.2 | 6.4 | 2.1 (1.6, 2.8) |

| 26–64 | 161.6 | 16.8 | 10.4 | 2.9 (2.3, 3.6) |

| ≥ 65 (Ref) | 46.5 | 2.9 | 6.2 | 1.0 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 125.6 | 14.0 | 11.1 | 1.8 (1.6, 2.1) |

| Male (Ref) | 116.9 | 8.0 | 6.8 | 1.0 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 37.8 | 3.9 | 10.2 | 1.0 (0.9, 1.2) |

| Non-Hispanic (Ref) | 204.7 | 18.1 | 8.8 | 1.0 |

| Race | ||||

| Black or African American | 29.8 | 3.9 | 13.1 | 1.3 (1.1, 1.5) |

| Non-Black (Ref) | 212.7 | 18.1 | 8.5 | 1.0 |

| US Region | ||||

| Midwest | 54.4 | 5.1 | 9.3 | 1.4 (1.2, 1.7) |

| South | 90.0 | 9.7 | 10.7 | 1.4 (1.0, 1.7) |

| West | 55.8 | 4.3 | 7.8 | 1.2 (1.0, 1.4) |

| Northeast (Ref) | 42.3 | 2.9 | 6.9 | 1.0 |

| Health insurance | ||||

| None | 25.1 | 5.1 | 20.3 | 3.9 (3.3, 4.5) |

| Medicare | 51.1 | 4.7 | 9.2 | 1.6 (1.2, 2.0) |

| Medicaid only | 22.5 | 3.0 | 13.3 | 1.4 (1.2, 1.7) |

| Other government or public coverage | 8.1 | 0.6 | 7.4 | 0.9 (0.7, 1.3) |

| Private insurance only (Ref) | 129.2 | 7.9 | 6.1 | 1.0 |

| Health status | ||||

| Fair or poor | 31.3 | 7.3 | 23.3 | 2.7 (2.4, 3.1) |

| Good, very good, or excellent (Ref) | 211.2 | 14.6 | 6.9 | 1.0 |

| Activity limitation owing to disability | ||||

| Yes | 38.7 | 7.5 | 19.4 | 2.3 (1.9, 2.7) |

| No (Ref) | 203.8 | 14.5 | 7.1 | 1.0 |

Note. CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

Source. 2015 Sample Adult and Core National Health Interview Survey (2016).

Numbers in millions.

DISCUSSION

Our results do not provide definitive proof that the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 or the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 led to improved access for costly prescription medications, but they do strongly suggest that important health behaviors like prescription nonadherence are responsive to changes in the policy environment. The 2015 logistic regression model confirms that lack of insurance coverage remains a powerful predictor of CRN. Continued efforts to improve access to public and private health insurance (e.g., by encouraging more states to participate in the Medicaid expansion) would further reduce CRN prevalence, as would proposals to contain prescription drug prices. Our analyses also show that CRN is a complex issue driven by factors beyond income and insurance, including race, ethnicity, gender, residence, health status, and disability.

There was no preliminary question in the National Health Interview Survey about whether a medication had been prescribed in the previous year. Consequently, we could not distinguish between adherent and nonadherent groups but only between those who reported CRN and those who did not. Because children are a relatively healthy age group, they are less likely to be prescribed medications and therefore less likely to have difficulty paying for medications.

More broadly, the behavior of prescription nonadherence requires interaction with a prescriber. One could imagine a previously uninsured respondent who enrolls in a plan with generous primary care coverage but limited prescription drug benefits who reports her first experience with CRN because of the change in insurance status that allowed her to meet with a doctor and receive a prescription. This suggests that CRN is an important but limited measure of health care access.

PUBLIC HEALTH IMPLICATIONS

Despite recent reforms, too many Americans remain unable to afford to fill and take their medications as prescribed. This is confirmed by polling data: a recent Kaiser Family Foundation survey found that 72% of Americans feel that prescription drug costs are unreasonable, although they are split on policy remedies to contain these costs.12 Researchers should continue to track CRN prevalence as a measure of health system performance, and policymakers should continue to explore strategies to improve access to prescription medicines.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This article was developed with support from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR), Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS; grant 90DP0075-01-00).

Poster presented at AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting; Boston, Massachusetts; June 27, 2016.

Note. The contents of this article do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, HHS, or the US Government.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

No institutional review board approval was required because this was a secondary analysis of public use survey data.

Footnotes

See also Galea and Vaughan, p. 1730.

REFERENCES

- 1.Thinking Outside the Pillbox: A System-Wide Approach to Improving Patient Medication Adherence for Chronic Disease. Cambridge, MA: New England Healthcare Institute; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kennedy J, Coyne J, Sclar D. Drug affordability and prescription noncompliance in the United States: 1997–2002. Clin Ther. 2004;26(4):607–614. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(04)90063-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kennedy JJ, Maciejewski M, Liu D, Blodgett E. Cost-related nonadherence in the Medicare program: the impact of Part D. Med Care. 2011;49(5):522–526. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318210443d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soumerai SB, Pierre-Jacques M, Zhang F et al. Cost-related medication nonadherence among elderly and disabled Medicare beneficiaries: a national survey 1 year before the Medicare drug benefit. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1829–1835. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Y, Donohue JM, Lave JR, O’Donnell G, Newhouse JP. The effect of Medicare Part D on drug and medical spending. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(1):52–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0807998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zivin K, Madden JM, Graves AJ, Zhang F, Soumerai SB. Cost-related medication nonadherence among beneficiaries with depression following Medicare Part D. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17(12):1068–1076. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181b972d1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kennedy J, Erb C. Prescription noncompliance due to cost among adults with disabilities in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(7):1120–1124. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.7.1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kennedy J, Morgan S. Cost-related prescription nonadherence in the United States and Canada: a system-level comparison using the 2007 International Health Policy Survey in seven countries. Clin Ther. 2009;31(1):213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Briesacher BA, Gurwitz JH, Soumerai SB. Patients at-risk for cost-related medication nonadherence: a review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(6):864–871. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0180-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davidoff AJ. Identifying children with special health care needs in the National Health Interview Survey: a new resource for policy analysis. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(1):53–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00215.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaiser Family Foundation. Summary of New Health Reform Law. Washington, DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaiser Family Foundation. Kaiser Health Tracking Poll: August 2015. Washington, DC: 2015. [Google Scholar]