It has been 50 years since the Black Panther Party was founded by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale in Oakland, California. Today the organization is remembered for its black-clad, black-bereted members in disciplined formation, bearing arms. These are compelling images, but they in no way capture the organization’s historical significance or its lasting contribution to public health. These iconic images provide opportunities to tell unfinished stories.

Fifty years is a long time to wait to restore the Black Panther Party’s image to reflect its full and lasting legacy. This legacy should acknowledge that, in just a few years, the Party rapidly extended its initial commitment to armed self-defense against police violence to mobilization against a more ambitiously framed concept of violence. In this broader view, lack of adequate housing, education, and jobs were also forms of violence. And the Party proclaimed its obligation to act against these injuries as well. Protection came in the form of programs, not guns. In expanding its perspective beyond the problem of police violence to the far-reaching consequences of racism in everyday life, the Party aligned itself with progressive forces such as the civil rights and women’s movements in the United States, and liberation movements in Africa and Asia.

The Party took up the right to health. It would be a mischaracterization to see the Party’s range of activities as a cobbled-together, mismatched chimera—part paramilitary and part social work. Rather, its vision hewed closely to the fundamentally radical idea that achieving health for all demands a more just and equitable world. To model ways in which such a world might work, the Black Panthers opened free health clinics across the country. Eventually 13 were established.

The Black Panther Party clinics were part of a movement to deliver community-based health care that had roots in the civil rights movement, which gave rise to the Medical Committee for Human Rights. In 1965, two physician-activists—H. Jack Geiger and Count D. Gibson Jr—opened the first US community health centers in Boston, Massachusetts, and Mount Bayou, Mississippi. Geiger and Gibson believed that health could not be fully achieved without addressing poverty.1 The Black Panther Party took the argument one step further, articulating that the failure to address poverty (and oppression and unemployment and lack of adequate education and housing) were causes of poor health.2

The Black Panthers emerged as champions of health as a human right: first for Blacks and later more broadly for the poor. Its first guiding document—the “Ten Point Program” issued in 1966—did not mention health. But by 1970, following a call from leadership to establish free clinics,3 the Ten Point Program was modified. In 1972, health was formally added as the sixth point:

WE WANT COMPLETELY FREE HEALTH CARE FOR ALL BLACK AND OPPRESSED PEOPLE

We believe that the government must provide, free of charge, for the people, health facilities which will not only treat our illnesses, most of which have come about as a result of our oppression, but which will also develop preventive medical programs to guarantee our future survival.4

Additionally, the revised Ten Point Program now referred to “Black and oppressed people,” not just Blacks. Looking back, the Ten Point Program shares both language and sentiment with the US Declaration of Independence, from which it quoted, and with the African National Congress Freedom Charter, articulated in 1955 to guide the next nearly 40 years of its 80-year fight against South African apartheid. The Freedom Charter proclaimed that government would be responsible for free health care, both preventive and curative.5

The Black Panther Party was the second step on my path to public health. The first was a summer job after high school. I worked as a census taker in West Harlem, New York, in 1970, collecting data the old-fashioned way: going door-to-door. As a college student, I volunteered at the Party’s Boston Franklin Lynch Peoples’ Free Health Center in Roxbury, Massachusetts—sited to block construction of a proposed highway. It took its name from a young man who died at the hands of police, reportedly shot dead while hospitalized.6 I was not a Party member, but as a volunteer I was given assignments. The first was to schedule doctors, all of whom were also volunteers, to staff clinic hours. Later, I would learn that they were all well-regarded academics from prominent Boston-area medical schools. I am sure they were busy, but I cajoled, bullied, and begged.

Then I got a better assignment: to run the sickle cell screening program. The Black Panther Party learned that sickle cell anemia was a neglected genetic disease—neglected because most of those affected were of African descent. Although it had been described in 1910,7 it attracted little public attention and even less funding. Treatment was extremely limited, as it is to this day. There was a rapid screening test based on a simple finger stick, but the test was not widely employed. The Black Panther Party rectified this government failure to act by setting up a national screening program.

The Black Panther Party’s Franklin Lynch Peoples’ Free Health Center, circa 1970, Boston, MA.

Source. It’s About Time Archives (http://itsabouttimebpp.com).

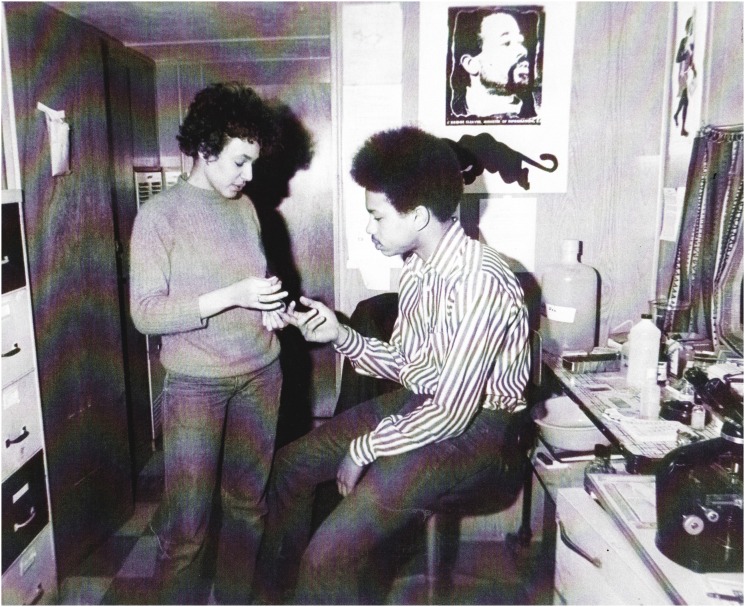

Mary T. Bassett (left) demonstrating a finger stick for sickle cell screening at the Black Panther Party’s Franklin Lynch Peoples’ Free Health Center, circa 1970, Boston, MA.

Source. It’s About Time Archives (http://itsabouttimebpp.com).

I recruited Boston-area premed students to perform the screening test. Panther members leafleted public housing buildings the night before, and each Saturday a group of a dozen doctors-to-be fanned out, wearing white jackets, to offer testing in people’s homes. Area hospitals provided follow-up for those who screened positive. The sickle cell screening program was a lesson in community health that has never left me. It was more than just a service—it was an organizing tool.

That more than a dozen Panther Party members remain imprisoned five decades later has more to do with this legacy of addressing systemic inequity than with the berets and guns that so effectively propelled these beautiful, young Black people into public view. In Stanley Nelson’s 2015 documentary “Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution,” a former leading Panther member Ericka Huggins noted smilingly, “We had swag.” They also unleashed a staggering government response, including the reprehensible intervention of J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI in the form of the now infamous COINTELPRO that saw the leadership arrested, jailed, and killed.

While the Black Panther Party eventually disbanded in 1982, it popularized a set of beliefs that identified health as a social justice issue for Blacks and influenced public health to this day. Its militancy, blending science with community engagement, resonates today under the banner of #BlackLivesMatter. That health is a right, not a privilege, remains true. It is a proud legacy, one built by many, still unachieved, and still worth fighting for today.

REFERENCES

- 1.Massachusetts League of Community Health Centers. History of Community Health Centers. Available at: http://www.massleague.org/CHC/History.php. Accessed June 10, 2016.

- 2.Fullilove R. The Black Panther Party Stands for Health. Columbia University, Mailman School of Public Health; Public Health Now. February 23, 2016. Available at: https://www.mailman.columbia.edu/public-health-now/news/black-panther-party-stands-health. Accessed June 13, 2016.

- 3.Nelson A. Body and Soul: The Black Panther Party and the Fight against Medical Discrimination. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4. The Black Panther Party Research Project. Black Panther Party Platform and Program. Available at: http://web.stanford.edu/group/blackpanthers/history.shtml. Accessed June 10, 2016.

- 5. African National Congress: The Freedom Charter (as adopted June 26, 1955). Available at: http://www.anc.org.za/show.php?id=72. Accessed June 10, 2016.

- 6. Program for Survival, The Black Panther, Saturday March 24, 1973. Available at: http://www.itsabouttimebpp.com/Survival_Programs/pdf/Survival_Programs.pdf. Accessed June 10, 2016.

- 7.Serjeant GR. One hundred years of sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol. 2010;151(5):425–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]