Abstract

Drugs that target G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) represent the primary treatment strategy for patients with acute and chronic pain; however, there is substantial individual variability in both the efficacy and adverse side effects associated with these drugs. Variability in drug responses is, in part, due to individuals’ diversity in alternative splicing of pain-relevant GPCRs. GPCR alternative splice variants often exhibit distinct tissue distribution patterns, drug binding properties, and signaling characteristics that may impact disease pathology as well as the size and direction of analgesic effects. Here, we review the importance of GPCRs and their known splice variants to the management of pain.

Pain is a multidimensional sensory and emotional experience that can generally be categorized into one of four types1. Nociceptive pain is an acute response to environmental stimuli that warns of potential or actual tissue damage. In the event of actual damage, inflammatory and/or neuropathic pain may occur. Inflammatory pain occurs in response to damage of tissues and infiltration of immune cells, while neuropathic pain occurs in response to damage of nerves. Inflammatory and neuropathic pain typically serve to promote wound healing and repair; however, in many cases, the pain outlasts the stimulus and becomes chronic. Unlike inflammatory and neuropathic pain, functional or idiopathic pain is characterized by perpetual abnormalities in sensory processing that occur in the absence of direct inflammation or nerve damage.

Acute and chronic pain are primarily treated with pharmacological agents that promote analgesia. The principle target of a variety of analgesic drugs including opioids, cannabinergics, and anti-depressants is g-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs). Upon activation, GPCRs initiate molecular changes resulting in excitation or inhibition of nerve, immune, and glial cells important for the onset and maintenance of pain. While the critical role of GPCRs in pain biology and management is well established, reliably effective therapeutics with minimal side effects are lacking. Inter-individual variability in response to a given analgesic is largely due to variation at the genetic level. Of particular interest are genetic variants in alternative splice regions that alter protein coding of the mRNA, giving rise to proteins which differ in form and function (i.e., alternative splice variants). This review highlights the importance of alternative splicing in the regulation of GPCRs involved in the transmission and modulation of pain.

GPCRs are Relevant for the Treatment of Pain

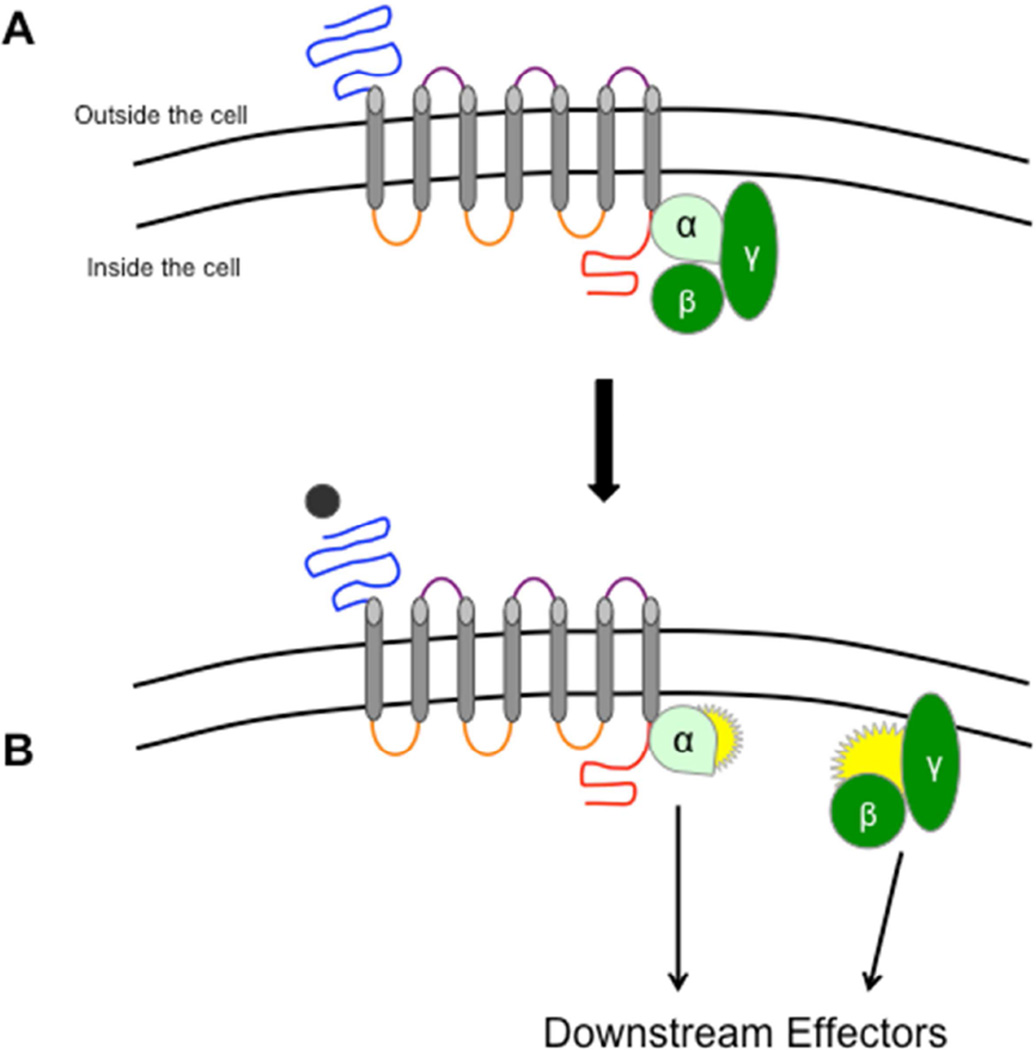

The human genome encodes approximately 800 distinct GPCRs, 70% of which contribute to pain or pain-related phenotypes2 .GPCRs interact with a tremendous variety of signaling mediators, ranging from small molecules to large peptides and proteins. Although each receptor has the ability to induce a range of functional intracellular changes, all GPCRs possess a distinct and evolutionarily conserved architecture. Each canonical or classic receptor is comprised of seven transmembrane (7TM) proteins that span the cellular membrane. These transmembrane proteins are interconnected by intracellular and extracellular loops (Figure 1). In addition, there are amino acid chains known as N-terminus and C-terminus tails, which are attached to the first and last transmembrane, respectively. As alluded by its name, every GPCR is coupled to a g-protein, which acts as a molecular switch to regulate cellular activity. (Table 1).

Figure 1.

GPCR structure and function. A) A g-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) is composed of seven transmembranes (grey) interconnected by three intracellular (orange) and three extracellular (purple) loops. On the end of the first and last transmembrane are the N-terminus (blue) and C-terminus (red), respectively. As its name suggests, a GPCR is bound to a tri-meric g-protein composed of alpha (α) and beta/gamma (β/γ) subunits. B) When a ligand (black) binds to a GPCR, the associated g-protein separates into the α and β/γ subunits. These subunits then stimulate a variety of downstream effectors that produce changes in cellular activity (see Table 1). Abbreviations: GPCR = G-Protein Coupled Receptor

Table 1.

Common G-proteins and Their Intracellular Effects.

| G protein | Effectors | Overall Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Gαs | activates adenylyl cyclase → ↑ cAMPa | cellular excitation (pro-nociceptive) |

| Gαq | activates PLCβ → ↑ intracellular Ca++ levels | cellular excitation (pro-nociceptive) |

| Gαi/o | inhibits adenylyl cyclase → ↓ cAMP | cellular inhibition (anti-nociceptive) |

Abbreviations: cAMP = cyclic adenosine monophosphate; Ca = calcium; PLCβ = phospholipase C β.

The resulting structure created by the transmembrane segments and loops provides interactive sites where ligands can bind. Ligands that bind to their receptor and initiate cell signaling are referred to as agonists. Upon binding, agonists produce a conformational change of the GPCR and subsequent uncoupling of the associated g-protein. Once uncoupled, the g-protein separates into two subunits (the alpha (α) and beta/gamma (β/γ) subunits), each of which initiates a chain of molecular reactions that affect cellular activity3. Depending on the type of g-protein, the initiated downstream effects can promote cellular excitation or inhibition (Table 1). In general, agonists that activate pain-relevant GPCRs coupled to Gs typically produce pain, while those coupled to Gi typically inhibit pain2. Other ligands, known as antagonists, compete with agonists for the GPCR binding site and impede g-protein uncoupling and downstream signaling events. Because of their ability to modulate cellular activity at each step of the pain pathway, GPCRs represent a popular pharmacologic target for the management of clinical pain. In fact, over 60% of commonly prescribed analgesics work by binding to GPCRs3. Table 2 provides a summary of these GPCRs (opioid, cannabinoid, adrenergic, and serotoninergic receptors) along with their associated g-protein, endogenous ligands, and analgesic compounds.

Table 2.

GPCRs Commonly Targeted for Clinical Pain Management.

| GPCR | G- protein |

Endogenous Ligands |

Prescribed Analgesics | Known Splice Variant |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reuptake Inhibitors |

Agonist | Antagonist | ||||

| Mu-Opioid Receptor | ||||||

| MOR-1a | Gαi4 | α-endorphin β-endorphin Y-endorphin |

Alfentanil Buprenorphine Codeine Fentanyl Hydrocodone Hydromorphon e Levorphanol Meperidine Methadone Morphine Oxycodone Oxymorphone Remifentanil Sufentanil Tapentadol Tramadol |

Naloxone Naltrexone |

Yes | |

| Cannabinoid (CB) Receptors | ||||||

| CB1 | Gαi5 | 2-AG Anandamide LPI NADA OAE |

Nabilone THC |

Cannabidi ol |

Yes | |

| CB2 | Gαi5 | Nabilone THC |

Cannabidi ol |

Yes | ||

| Adrenergic (AR) Receptors | ||||||

| α1AR | Gαq6 | Epinepherine Norepinephrine |

Amitriptyline (NET) Despiramine (NET) Desvenlafaxine (NET) Duloxetine (NET) Levorphanol (MAO) Meperidine (NET) Nortriptyline (NET) Tapentadol (NET) Venlafixine (NET) |

Amitriptylin e Promethaz ine Nortriptylin e Trazodone |

Yes | |

| α2AR | Gαi6 | Clonidine | Trazodone | No | ||

| β1AR | Gαs7 | Atenolol Nadolol Metoprolol Propanolol Timolol |

No | |||

| β2AR | Gαs, Gαi7 |

Nadolol Propanolol Timolol |

No | |||

| β3AR | Gαs7 | Nadolol Propanolol Timolol |

Yes | |||

| Serotonin (5-HT) Receptors | ||||||

| 5-HT1 | Gαi8 | Serotonin | Amitriptyline (SERT) Despiramine (SERT) Desvenlafaxine (SERT) Duloxetine (SERT) Levorphanol |

Almotriptan Dihydroergota mine Eletriptan Frovatriptan Naratriptan Rizatriptan Sumatriptan Zolmitriptan |

Trazodone | No |

| 5-HT2 | Gαq8 | (MAO) Nortriptyline (SERT) Trazodone (SERT) Venlafaxine (SERT) |

Dihydroergota mine Methylergomet rine |

Amitriptylin e Nortriptylin e Promethaz ine Trazodone |

Yes | |

| 5-HT4 | Gαs8 | Mosapride | Yes | |||

| 5-HT6 | Gαs8 | Amitriptylin e Nortriptylin e Trazodone |

Yes | |||

| 5-HT7 | Gαs8 | Amitriptylin e Trazodone |

Yes | |||

Abbreviations: 2-AG = 2-Arachidonoylglycerol; 5-HT = Serotonin; CB = Cannabinoid; LPI = Lysophosphatidylinositol; MAO = Monoanime Oxidase; MOR-1 = Mu Opioid Receptor NADA = N-Arachidonoyl Dopamine; NET = Norepinephrine Transporter; OAE = Virodhamine (OAE); SERT = Serotonin Transporter; THC = Tetrahydrocannabinol; αAR = Alpha adrenergic receptor; βAR = Beta adrenergic receptor

Opioid receptors are among the most well known GPCRs that regulate the transmission and perception of pain. There are four opioid receptor subtypes, including: the mu opioid receptor (MOR-1), the delta opioid receptor, the kappa opioid receptor, and the nociceptin receptor. Of these subtypes, MOR-1 is the classic receptor responsible for analgesic responses to endogenous endorphins as well as exogenous drugs. Upon agonist binding to MOR-1, its associated Gαi protein is activated and produces cellular inhibition of pronociceptive neurons9. For this reason, opioids are used in the management of acute pain (such as that associated with surgery) as well as chronic pain disorders such as low back pain, extremity pain, and osteoarthritis10. Opioid antagonists, usually co-administered with opioid agonists to reduce the development of unwanted opioid side effects, are also capable of producing analgesia independently of MOR-111.

Cannabinoid receptors share similar signaling properties with MOR-1, making them attractive targets for clinical pain management. There are two cannabinoid (CB) receptor subtypes, CB1 and CB2, both of which couple to Gαi. CB receptors play a significant role in promoting analgesia in response to endocannabinoids such as 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) and anandamide. Commercially available CB agonists such as nabilone and tetrahydrocannabidol, which bind to both CB subtypes, are used to treat fibromyalgia and neuropathic pain12.

Adrenergic receptors, which mediate the physiological responses to epinephrine (Epi) and norepinephrine (NE), represent another frequently targeted class of GPCRs. The adrenergic superfamily includes three subtypes respectively of α 1ARs (α1AAR, α1BAR, α1DAR), α2ARs (α2AAR, α2BAR, α2CAR), and βARs (β1ARs, β2ARs, β3ARs). The α2AR couples to Gαi and promotes analgesia via cellular inhibition. Hence α2AR agonists such as trazodone are used to promote analgesia. In contrast, α 1AR, which is coupled to Gαq, facilitates cellular excitation of pronociceptive neurons, resulting in increased pain signaling. The βARs also facilitate pain signaling via Gαs signaling. To attenuate their excitatory contributions, α1AR and βARs are commonly used to treat a range of chronic pain disorders such as migraine, neuropathic pain, and fibromyalgia.

Finally, serotonin receptors, which mediate physiological responses to the monoamine serotonin (5-HT) play an important role in pain management8. The serotonin superfamily is quite large, including seven general members: 5-HT1 (5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, 5-HT1D, 5-HT1E, 5-HT1F), 5-HT2 (5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, 5-HT2C), 5-HT3, 5-HT4, 5-HT5, 5-HT6, and 5-HT7. With the exception of the 5-HT3 receptor, a ligand-gated ion channel, all 5-HT receptors are GPCRs. The effects of the 5-HT receptor family on pain are heavily dependent upon the receptor subtype. Triptans target Gαi-coupled 5-HT1 receptors, which promote analgesia via cellular inhibition, and normalize vascular changes associated with migraine headache13. Antidepressants promote chronic synaptic serotonin release that causes the downregulation of Gαq coupled 5-HT2 receptors, thus attenuating their excitatory contributions to pain signaling. 5-HT antagonists that target 5-HT4 receptors in the central nervous system and the gastrointestinal (GI) tract are used in the treatment of migraine14 and IBS15. Meanwhile, the net effect of 5-HT7 activation on pain is highly dependent on the location of the receptor. Activation of 5-HT7 receptors on peripheral nerve terminals produces pain16,17, while activation in midbrain structures such as the periaqueductal gray alleviates pain associated with nerve injury18.

While these conventional therapeutics are able to alleviate pain, their efficacy is limited to a subset of the population19. Additionally, their use is constrained by adverse side effects, such as altered mental state, nausea, constipation, sedation, and life-threatening respiratory depression. Variability in patient response and side-effect profiles is, in part, due to diversity in alternative splicing of GPCRs expressed in tissues that regulate pain processing. By expanding our understanding of GPCR alternative splice variants and their associated pharmacodynamic responses, we will be able to better predict patient-centered treatment outcomes.

Alternative Splicing Adds to the Diversity of GPCR Signaling

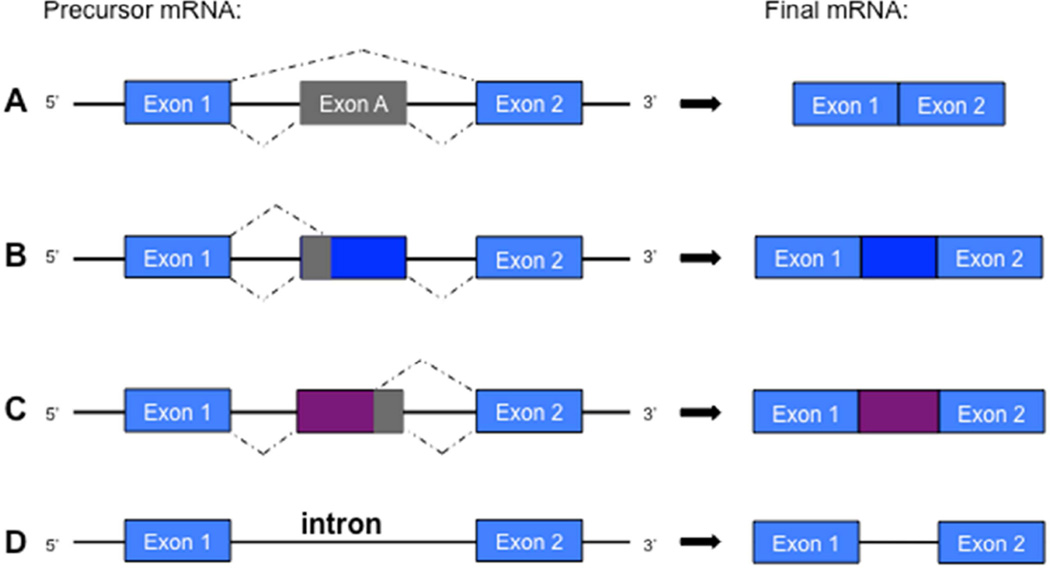

Alternative splicing is an important mechanism of gene regulation, affecting approximately 90% of all genes within the human genome20. A single gene is able to generate exponential protein coding capabilities via alternative splicing. Prior to alternative splicing, a gene is first transcribed into precursor messenger ribonucleic acid (pre-mRNA). The pre-mRNA sequence contains short protein coding regions known as exons. Interspersed between the exons are longer non-coding regions known as introns (Figure 2). Before the sequence can be translated to produce protein, the introns and alternative exons within pre-mRNA are removed, or spliced, and the constitutive exons are brought together, resulting in the canonical mRNA transcript ready for protein synthesis. When alternative splicing occurs, however, the pre-mRNA is edited such that constitutive exons are removed from, or introns are retained, in the final mRNA transcript. The most common type of alternative splicing within the human genome is exon skipping21. Here, constitutive exons are excluded from the final mRNA transcript. Another common type of alternative splicing is splice site selection, in which the portion of an exon is spliced out due the presence of a nucleotide sequence that facilitates splicing activity21. Intron retention is another type of alternative splicing in which an intron remains in the final mRNA transcript. Each type of alternative splicing will render an mRNA transcript and corresponding protein that is structurally different than the canonical protein produced from the standard template.

Figure 2.

Different types of alternative splicing. The most common type of alternative splicing in animals is A) exon skipping, in which a constitutive exon is spliced from the final mRNA transcript. Alternative B) 3’ and C) 5’ splice sites provide additional junctions within an exon, resulting in partial splicing of the exonic mRNA sequence. D) Intron retention is a rare type of alternative splicing that occurs when an intron remains within the final mRNA transcript. Abbreviations: mRNA = Messenger Ribonucleic Acid

Accumulating evidence suggests that alternative splicing significantly adds to the functional diversity of the human genome and that variations in these processes produce pathological states22. The presence of multiple GPCR splice variants allows for essential, precisely regulated differences in expression (e.g., tissue-specific expression)23, as well as in agonist binding24, agonist-induced internalization25, and intracellular signaling dynamics25,26. Some alternative splice variants even display functional characteristics opposite to the canonical form27–29 Polymorphisms that alter the ratio of functionally distinct protein isoforms through alternative splicing may produce changes in the direction of pain-relevant GPCR pharmacodynamics (e.g. coupling to stimulatory vs. inhibitory G protein effector systems), yet remain understudied. A PubMed search of “alternative splicing pain” yields only 87 relevant original research articles. Most are focused on ion channels such as voltage-gated calcium channels30 and transient receptor potential channels31,32, with only 12 articles focusing on GPCRs. This is an important area of study as identification of GPCR splice variants differentially expressed in individuals with altered pain perception and/or analgesic responses will help elucidate novel targets for the development of individualized treatment strategies.

Functional GPCR Alternative Splice Variants

Examples of alternative splice variants of pain-relevant GPCRs that exhibit diversity in expression and signaling profiles include the aforementioned MOR-1, cannabinoid receptors, adrenergic receptors, and serotonin receptors. Of additional interest are nociceptin, prostaglandin and neurokinin receptors, which are not targeted by common analgesics but are critical for the induction and modulation of pain. Accumulating evidence from in vitro, pre-clinical, and clinical studies suggests that alternative splicing of these and other GPCR transcripts adds additional layers of complexity to GPCR signaling and pharmacodynamics responses. (Table 3).

Table 3.

Signaling, Tissue Distribution, and Function of Known GPCR Splice Variants.

| Receptor Variants |

G- protein |

Tissue Distribution | Functional Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Opioid Receptors | |||

| MOR-1 | Gαi4 | brain, spinal cord > adrenal gland > small | |

| C-term | intestine34 | ||

| variants | OP binding → analgesia38 | ||

| MOR-1A | brain35 | OP binding → analgesia38 | |

| MOR-1B | brain35 | OP binding → analgesia38 | |

| MOR-1C | brain35; agonist-induced reduction36 | OP induced itch33 | |

| MOR-1D | Gαi33 | brain35 | OP binding → analgesia38 |

| MOR-1E | brain35 | OP binding → analgesia38 | |

| MOR-1F | brain35 | ? | |

| MOR-1O | brain35 | ? | |

| MOR-1P | brain35 | ? | |

| MOR-1U | brain35 | ? | |

| MOR-1V | brain35 | ? | |

| MOR-1W | brain35 | ? | |

| MOR-1X | brain35 | OP binding → analgesia39 | |

| MOR-1Y | brain35 | ||

| N-term | Novel opioid binding40 | ||

| variants | brain35 | OP binding → analgesia41 | |

| MOR-1G | brain35 | OP binding → analgesia41 | |

| MOR-1H | brain35 | OP binding → analgesia41 | |

| MOR-1I | brain35 | contributes to OIH | |

| MOR-1J | Gαs29 | brain35 | OP binding → analgesia41 |

| MOR-1K | brain35 | ? | |

| MOR-1L | brain35 | ? | |

| MOR-1M | brain35 | ||

| MOR-1N | ? | ||

| Single TM | brain35 | Stabilization of MOR-142 | |

| variants | brain35 | Stabilization of MOR-142 | |

| MOR-1Q | brain35 | ? | |

| MOR-1R | brain35 | ? | |

| MOR-1S | brain35 | ? | |

| MOR-1T | brain (human neuroblastoma cell line)37 | ? | |

| MOR-1Z | brain (human neuroblastoma cell line)37 | ||

| MOR-1SV1 | |||

| MOR-1SV2 | |||

| ORL-1 | Gα i43 | brain, immune cells, GI tract44 | |

| ORL-1Short | brain > testis > heart, kidneys, muscle, | ↓ agonist binding46 | |

| ORLLong | spleen, thymus45 brain > testis > muscle, spleen45 |

? | |

| Cannabinoid Receptors | |||

| CB1 | Gα i5 | brain, sc, DRG > pituitary > heart, lung, uterus, testis, spleen, tonsils47 |

|

| N-term | |||

| variants | ↓ agonist binding, ↓GTPγS activity48 | ||

| CB1a | similar distribution to CB1+ kidney48,49 | ↓ agonist binding, ↓GTPγS activity48 | |

| CB1b | fetal brain > GI tract, uterus, muscle > adult brain48 |

||

| CB2 | Gα i5 | immune cells/tissues > glia and macrophages in brain/sc47,50–52 |

|

| N-term | |||

| variants | ? | ||

| CB2A | testis > spleen, leukocytes > brain53 | ? | |

| CB2B | spleen > leukocytes53 | ||

| Adrenergic Receptors | |||

| α1A | Gαq6 | liver, heart, brain > prostate, kidney, bladder6 | |

| C-term variants |

Gα i7 | liver, heart > prostrate, kidney54,55 | pharmacology similar to α1A7,54,55,57 |

| α 1A-2 | Gα i7 | liver > heart, prostrate (absent in kidney)54,55 | |

| α1A-3 | Gα i7 | liver, heart > prostrate, (absent in kidney)54,55 | |

| α1A-4 | |||

| α 1A-5 | |||

| 6TM variants (−TM7) |

liver, heart, hippocampus, and prostate; expressed intracellularly56 |

impair α1A binding & cell surface expression56 |

|

| α1A-6 | |||

| α 1A-7 | |||

| α 1A-8 | |||

| α1A-9 | |||

| α1A-10 | |||

| α 1A-11 | |||

| α1A-12 | |||

| α 1A-13 | |||

| α 1A-14 | |||

| α1A-15 | |||

| α 1A-16 | |||

| α1B | Gαq6 | liver, heart, brain (including cortex) 6 | |

| 6TM variant | |||

| (−TM7) | expressed in hippocampus, but absent in | ? | |

| α 1B-2 | cortex58 | ||

| β3 | Gαs, | fat, immune cells/tissues > GI tract, DRG59,62 | |

| Gα i59,60 | |||

| C-term variants |

fat > ileum > brain63 | ? | |

| β3a (mouse) | Gαs7,61 | brain > fat, ileum63 | ? |

| β3b (mouse) | Gαs,Gαi7,61 | ||

| Serotonin Receptors | |||

| 5-HT2A | Gαq8 | cortex, hippocampus, brainstem, olfactory > basal ganglia, limbic8 |

|

| 6TM variant (−TM4) | impaired 5-HT-induced Ca++ signaling64 | ||

| 5-HT2A–tr | hippocampus, caudate, corpus collosum, amygdala, substania nigra64 |

||

| 5-HT2C | Gαq8 | choroid plexus, striatum, hippocampus, hypothalamus, olfactory, sc8,65 |

|

| 6TM variant (−TM4) 5-HT2CT |

choroid plexus, striatum, hippocampus, hypothalamus, olfactory, sc65 |

impaired 5-HT ligand binding65 | |

| C-term variant | impaired 5-HT ligand binding66 | ||

| 5-HT2AC-R- COOHΔ |

sc, cortex, cerebellum, medulla, caudate, amygdala, corpus collosum66 |

||

| 5-HT4 | Gαs8 | intestine > brain > pit > uterus, testis > spleen > heart, kidney, lung, sc74 |

|

| C-term variants | Gαs67 | ↑ constitutive AC activity, ↑ isomerization, ↓ | |

| 5-HT4a | Gαs, | intestine, brain > pit > uterus, testis > heart > | agonist internalization76,77 |

| 5-HT4b | Gαi67,68 | spleen, lung, sc74 | ↑ constitutive AC activity67 |

| 5-HT4c | Gαs67 | intestine, brain > pit > uterus > heart, spleen, | ↑ constitutive AC activity67 |

| 5-HT4d | Gαs67 | lung, sc74 | 20-fold ↑ in agonist-induced cAMP activity78 |

| 5-HT4e | Gαs69 | intestine > pit > brain > uterus, testis, heart, | ↑ constitutive AC activity69 |

| 5-HT4f | Gαs70 | spleen, sc74 | ? |

| 5-HT4g | Gαs71 | ileum, colon, but absent in brain73,75 | ? |

| 5-HT4i | Gαs72 | brain > testis > sc > intestine, pit, heart, | ↑ constitutive AC activity79 |

| 5-HT4n | Gαs73 | prostate ileum, colo75 brain, ileum, colon75 |

|

| 2nd EL loop | brain, heart, ileum, colon75 | ||

| variant | Gαs70 | brain, ileum, colon, heart75 | antagonist GR113808 acts as partial |

| 5-HT4h | brain, heart, oesophagus75 GI tract70 |

agonist70 | |

| 5-HT6 | Gαs8 | cortex, hippocampus, olfactory, striatum, amygdala, acumbens8 |

|

| 6TM variant (−TM4) | impaired binding to 5-HT and LSD80 | ||

| 5-HT6-tr | cortex, hippocampus, cerebellum, thalamus, substantia nigra, caudate80 |

||

| 5-HT7 | Gαs8 | brain, heart, GI tract, muscle, kidney, astrocytoma, glia83,84 |

|

| C-term variants |

Gαs81 | ? | |

| 5-HT7a | Gαs82 | brain, heart, GI tract, spleen, lung, | ↑ constitutive AC activity82 |

| 5-HT7b | Gαs82 | astrocytoma, glia81,83,84 | exhibit agonist-independent internalization85 |

| 5-HT7d | brain, heart, GI tract, spleen, lung, astrocytoma, glia82–84 heart, GI tract, ovary, testis, spleen, lung, astrocytoma83 |

||

| Prostaglandin E Receptors | |||

| EP3 | Gα i86 | Kidney> uterus>stomach> brain, thymus, heart, spleen86 |

|

| C-term | |||

| variants | Gα i, | ↓ constitutive AC activity86 | |

| EP3A/I | Gα1286 | ? | ↓ AC activity86 |

| EP3B/II | Gα i, | ? | ↓ or ↑ constitutive AC activity86 |

| EP3C/III | Gα1286 | ? | ? |

| EP3D | Gαi, Gαs86 | ? | ? |

| EP3E | ? | ? | ? |

| EP3F | ? | ? | |

| ? | |||

| Neurokinin Receptor | |||

| NK-1R | Gαq/1187 | brain, GI tract, lung, thyroid, immune cells88 | |

| NK-1Rtruncated | ? | ? | Impaired SP-induced calcium release89 |

Abbreviations: 5-HT = serotonin;AC = adenylyl cyclase; N-term = amino terminus; Ca++ = calcium; C-term = carboxyl terminus; cAMP = cyclic adenosine monophosphate; EL = extracellular loop; GI = gastrointestinal; LSD = lysergic acid

Opioid receptors

The pharmacologic manipulation of the mu opioid receptor is an essential component of clinical pain treatment. Although the signaling characteristics of MOR-1 are well established, we are just beginning to understand the complex nature of genetic variants that contribute to alternative splicing. At least 20 MOR-1 splice variants have been identified in mouse and human genomes25, suggesting an array of potentially functional consequences that may occur with opioid administration.

Pre-clinical studies within the past 15 years have begun to reveal the functional properties of specific MOR-1 splice variants. Pasternak and coworkers provide evidence that the gene expression of MOR-1 splice variants represent compensatory responses to chronic opioid administration that stabilize or diminish the development of tolerance90 Other studies have shown that the presentation of some unwanted side effects are due to the activation of MOR-1 splice variants. For example, Liu and colleagues have demonstrated that because of its distinct C-terminus, the splice variant MOR-1D dimerizes with the gastrin-releasing peptide receptor in the mouse spinal cord to produce opioid-induced itch33 Another splice variant known as MOR-1K, a truncated receptor lacking the N-terminus and first transmembrane, has been implicated in the paradoxical increase in pain sensitivity known as opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH). In contrast to MOR-1 which typically couples to Gαi, MOR-1K couples to Gαs to activate adenylyl cyclase (AC) and increase intracellular calcium, thus engaging pro-nociceptive signaling events that likely drive OIH29. A subsequent preclinical study in mice revealed that genetic knockdown of MOR-1K hindered the development of OIH and unmasked opioid analgesia91.

Additional studies investigating the functional characteristics of MOR-1 splice variants provide evidence that a set of these receptors promote opioid analgesia by providing exclusive binding sites for different opioids. Transgenic mice lacking exon 11, an exon that provides an alternative promoter region for the MOR transcript, demonstrated substantial reductions in the analgesic efficacies of heroin, fentanyl, and the morphine metabolite morphine-6β-glucuronide24, suggesting that exon-11 containing variants play a critical role in opioid analgesia. Exon 11-containing splice variants also mediate the analgesic effects of iodobenzoylnaltrexamide (IBNtxA), a novel synthetic opioid that produces ten times the analgesic efficacy of morphine without producing respiratory distress, dependence, tolerance, or GI distress in rodents36,40,92. MOR-1 splice variants also promote analgesia by enhancing canonical receptor function. Single-transmembrane splice variants MOR-1R and MOR-1S structurally enhance MOR-1 function by stabilizing the canonical 7TM receptor at the cellular membrane42. Collectively, these studies highlight the importance of MOR-1 alternative splice variants in mediating opioid analgesia, as well as side effects such as tolerance, itch, and OIH.

Although few preclinical studies have examined the nociceptin receptor (ORL-1), it may also play an influential role in opioid analgesia. Majumdar and colleagues demonstrate that the exon 11 splice variant MOR-1G dimerizes with ORL-1 to provide a binding site for novel opioid IBNtxA93, suggesting that ORL-1 interacts with MOR-1 splice variants to provide specific opioid binding sites. The contribution of ORL-1 to splice variant signaling is further complicated by the existence of its own splice variants, ORL-1Long and ORL-1Short94. Thus far, ORL-1Short has been implicated in the regulation of the canonical receptor, indicating a possible influence over ORL-1 function.

Cannabinoid receptors

Both the CB1 and CB2 receptors undergo alternative splicing to yield variants differing at their N-terminal region. The CB1a variant is truncated by 61 amino acids, with the first 28 amino acids completely different from the canonical CB149. While its tissue distribution largely overlaps with that of CB1, CB1a exhibits decreased agonist binding and activity, which might be due to a lack of two glycosylation sites typically important for signal transduction95. The CB1b variant lacks the first 33 N-terminus amino acids and although it overlaps with CB1 in a number of tissues, its abundant expression in fetal brain suggests it may play an important role in development48. Similar to CB1a, CB1b exhibits decreased agonist binding and activity.

The CB2 variants are generated through the use of alternate promoters located upstream of the major coding exon 353. The gene CB2A is initiated from the more distal promoter and includes exons 1a and 1b spliced to exon 3, while CB2B is initiated from the more proximal promoter and includes exon 2 spliced to exon 3. The CB2A variant is predominantly expressed in testes and at lower levels in spleen and brain. In contrast, the CB2B variant is predominantly expressed in spleen with very low expression in brain and no expression in testes. These tissue-specific distribution patterns may indicate specialized roles for the different splice variants with respect to pain modulation, immune response, and spermatogenesis.

Adrenergic receptors

Adrenergic receptors play a key role in pain processing as well as cognition and cardiovascular function. While α2ARs, β1ARs, and β2ARs are highly relevant to the modulation of pain by endogenous and exogenous agonists, the genes encoding these receptors are intronless and not subject to alternative splicing. Among the remaining adrenergic receptors, the α1AAR subtype has best most extensively studied with respect to alternative splicing.

The human α1AAR gene locus is comprised of over 8 exons and codes for 15 known splice variants96 The canonical receptor is generated through splicing exon 1 (coding for the N-terminus and transmembranes [TM] 1 to 6) together with exon 2 (coding for TM7 and the C-terminus). Four C-terminus splice variants (α1A-2, α1A-3, α1A-4, α1A-5) have been identified that are generated through the use of additional acceptor sites at varying locations within, and distal to, exon 2. The α1A-2, α1A-3, and α1A-4 variants exhibit ligand binding properties and tissue distribution profiles similar to α1AAR, although α1A-3 and α1A-4 are absent in kidney54–57. In contrast to α1AAR that couples to Gαq, these variants couple to Gαi so as to inhibit AC activity7. This diversity in α1AAR signaling may contribute to differential responses to α1AR antagonists used in the treatment of pain.

In addition, eleven 6TM variants (α1A-6, α1A-7, α1A-8…α1A-16) have been identified that are generated through exon skipping. These variants lack TM7 and their C-terminal tails are located extracellularly56 The truncated 6TM variants are expressed in similar tissues as α1AAR, but are localized exclusively within the cell and unable to bind α1AR agonists or directly mediate signal transduction. The 6TM variants do, however, impair α1AAR ligand binding and trafficking to the cell surface. Thus, α1AAR 6TM variants likely play a significant physiological role by modifying the function and expression of their parent 7TM receptors.

One α1BAR splice variant has also been identified in human brain58 The α1BAR protein is generated through splicing of exons 1 and 2. In contrast to the canonical receptor, the α1B-2AR includes an immediately adjacent sequence following exon 1 in its coding sequence and excludes exon 2 that codes for TM7. Tseng-Crank and colleagues also identified low levels of a truncated α1DAR transcript, however the result was inconclusive and naturally occurring α1DAR variants were not observed58. More work is required to determine the potential functional role of α1BAR and α1DAR variants.

The β3AR is primarily known for its ability to regulate energy metabolism and thermogenesis58, though evidence for its ability to promote functional and neuropathic pain is emerging61,63,97. The gene encoding β3AR undergoes alternative splicing within the coding region to yield two C-terminal splice variants differing with respect to tissue expression, g-protein signaling profiles, and regulatory properties57,64,98. The β3AAR and β3BAR splice variants contain completely unique terminal chains that are 13 and 17 amino acids long, respectively. The β3AAR is primarily enriched in fat tissue and couples exclusively to Gαs, while the β3BAR is primarily enriched in brain and couples to both Gαs and Gαi. In addition, the β3AAR exhibits increased agonist-induced extracellular acidification, a measure of cAMP-independent cellular activity. Their unique tissue distribution and signaling profiles, together with the known functional role of β3ARs, could indicate that β3AARs play a greater role in lipolysis/thermogenesis and that β3BAR in brain mediate pain. While these studies were conducted in mouse, it is important to note that the human β3AR contains a significant number of genetic variants that are predicted to regulate alternative splicing65,66.

Serotonin receptors

Serotonin receptors play a key role in pain processing as well as mood and GI function8 Of the 5-HT1 (A, B, D-F), 5-HT2 (A-C), 5-HT4, 5-HT5, 5-HT6, and 5-HT7 GPCR family members, the 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C, 5-HT4, 5-HT6, and 5-HT7 receptors are known to undergo alternative splicing.

The human 5-HT2 receptor subtypes (5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, and 5-HT2C) couple to Gαq proteins to promote the transient release of intracellular calcium. One truncated splice variant of 5-HT2A (5-HT2A-tr) has been identified that utilizes alternate splice donor and acceptor sites to yield a 3TM receptor with 57 unique amino acids in the C-terminal region64 The 5-HT2A-tr is co-expressed with 5-HT2A in most brain tissues, however is unable to couple to the calcium pathway. Two truncated splice variants of 5-HT2C (5-HT2CT and 5-HT2C-R-COOHΔ) have also been identified. Similar to 5-HT2A-tr, the 5-HT2CT variant utilizes alternate splice donor and acceptor sites to yield a 3TM receptor with 19 unique amino acids in the C-terminal region65 The 5-HT2C-R-COOHΔ variant retains an extra 90 nucleotides from intron 5 in the TM4 splice site, resulting in a 3TM receptor with a short C-terminus66. Compared to the canonical 5-HT2C receptor, the truncated variants exhibit similar expression patterns but have impaired 5-HT ligand binding and g -protein coupling65,66. While the relative importance of these truncated 5-HT2 splice variants in humans remains unknown, they are conserved in rat and mouse66 where their expression levels increase following nerve injury99.

The 5-HT4 receptor couples preferentially to Gαs and, while widely expressed, the highest levels are found in intestine74. Agonists targeting 5-HT4 are beneficial in alleviating abdominal pain associated with irritable bowel syndrome. Of all the 5-HT receptors, 5-HT4 possesses the greatest diversity in alternative splicing. At least ten splice variants have been identified that vary with respect to their tissue distribution and function. Nine C-terminus variants (5-HT4a, 5-HT4b, 5-HT4c, 5-HT4d, 5-HT4e, 5-HT4f, 5-HT4g, 5-HT4i, 5-HT4n) have been identified that are identical up to amino acid Leu358, after which they vary in sequence and length75. Additionally, one variant (5-HT4h) has been identified that includes exon h coding for 14 additional amino acids in the second extracellular loop70 The 5-HT4a, 5-HT4b, 5-HT4c, and 5-HT4e variants are expressed in most tissues, with distribution patterns similar to the canonical form74,75. In contrast, the 5-HT4f variant is found in the brain and GI tract, but absent in the heart and other tissues22 Meanwhile, the 5-HT4d and 5-HT4h variants are expressed exclusively in the GI tract70,72,75. While all of the 5-HT4 splice variants display typical ligand binding properties, some show notable functional differences. Both of the GI-specific 5-HT4d and 5-HT4h variants have a tendency to recognize 5-HT antagonists as partial agonists70,78 Furthermore, the 5-HT4d variant exhibits a remarkable 20-fold increase in cAMP formation following application of the 5-HT4 agonist renzapride78 The 5-HT4b variant is unique in its able to couple to Gαi as well as Gαs proteins, suggesting its diverse signaling capabilities in the GI tract, brain, and other tissues68 In the absence of ligand b inding, the majority of C-terminus variants exhibits heightened constitutive AC activity67,69,73,76–78. The ability of GPCRs to increase basal AC activity has been previously reported and can result in physiological functions of the receptor that are largely independent of endogenous ligands or exogenous drugs100. Collectively, these studies illustrate the high degree of tissue and signaling specificity for a number of 5-HT4 splice variants that may be represent attractive targets for the development of new more selective drugs for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome among other conditions.

The 5-HT6 receptor is unique in that it is expressed almost exclusively in the central nervous system8. A 3TM splice variant of 5-HT6 (5-HT6-tr) has been identified in brain that is generated through different splice donor and acceptor sites80. The corresponding receptor includes the TM1–3 and 10 unique amino acids in its C-terminus. In contrast to 5-HT6, the expression of 5-HT6-tr is limited to substantia nigra and caudate. The 5-HT6-tr receptor is able to translocate to the membrane, yet unable to bind serotonin. This splice variant may have a yet-to-be-determined function or be indicative of abnormalities due to pathologic state.

The 5-HT7 receptor is expressed on primary afferent nociceptors, as well as in pain-relevant brain regions where it couples to Gαs to mediate the transmission and modulation of pain. Three splice variants of 5-HT7 (5-HT7a, 5-HT7b, 5-HT7d) have been identified that are all generated through alternative splicing of the second intron located near the C-terminal coding region. The 5-HT7a and 5-HT7b variants have tissue expression profiles and functional characteristics similar to the canonical receptor, though 5-HT7b has been shown to exhibit significantly higher constitutive AC activity when expressed in stable cell lines101. The 5-HT7d variant is predominantly expressed in smooth muscle tissues such as the heart and GI tract82 and displays unique functional characteristics. Compared to the canonical 5-HT7 receptor and the 5-HT7a and 5-HT7b variants, the 5-HT7d variant displays agonist-independent internalization (even in the presence of antagonist) and associated reductions in agonist-induced AC activity85. It has been suggested that differences in the functional characteristics of 5-HT7 variants is due to specific features of their carboxyl tails, leading to differential interactions with protein partners that mediate their activity, trafficking, and/or internalization85,102

Prostaglandin E Receptor 3

Prostaglandins, such as prostaglandin E2, are a product of cyclooxygenase (COX) that facilitate pain transmission through binding to the prostaglandin E receptor 3 (EP3 receptor). Activation of the Gαi-coupled EP3 receptor has been shown to produce analgesia103, but also to promote HIV-induced inflammation104 and sensitization of trigeminal nociceptors105. These contradictory effects may be due to the presence of EP3 splice variants. Six C-terminus splice variants (EP3A…F) have been identified, to date. Of these, the EP3C receptor exhibits the most unique signaling characteristics as it is able to couple to Gαs as well as Gαi86. The dual coupling of the EP3C variant to different g-proteins may explain the ability of EP3 ligands to produce both analgesia and hyperalgesia.

Neurokinin-1 Receptor

Neurokin-1 receptors (NK-1Rs) are targets for the endogenous pro-pain ligand substance P. Their activation results in Gαq-mediated increases in intracellular calcium levels and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines89 Alternative splicing of the NK-1R yields a truncated variant (NK-1Rtruncated) that lacks the C-terminus and has functional properties that differ from the canonical receptor. Unlike NK-1R, activation of the NK-1Rtruncated variant does not result in increased levels of calcium or nuclear activity of factor-κB (NF-κB). Instead, activation of NK-1Rtruncated results in decreased phosphorylation of protein kinase C (PKC) and levels of interleukin-8. A recent clinical study has demonstrated the utility of an NK-1R antagonist in the treatment of chronic pain conditions and anxiety106. Results from functional studies of the NK-1Rtruncated variant suggest that splice variant-specific agonists may also be useful for pain management.

Clinical Relevance of Functional Gene Regulatory Events

Given the extensive list of alternative GPCR splice variants and their known impact on signaling and pharmacodynamics, it is expected that these variants have important clinical implications for pain management. Major strides in both preclinical and clinical research are still needed before we can reliably predict a patient’s treatment response based on their splice variant expression profile. Such strides have been made, however, in the study of another type of gene variation, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Like alternative splicing, SNPs within key pain-related genes can result in changes that subsequently affect the encoded protein. For example, SNPs in the gene encoding catechol-o-methyltransferase (COMT; an enzyme that metabolizes catecholamines) are indicative of abnormalities in COMT function and predictive of chronic pain risk and treatment response. Human genetic association studies have shown that the rs4680 SNP, alone or in combination with other nearby SNPs, is predictive of temporomandibular disorder (TMD) and fibromyalgia onset107,108. Subsequent molecular studies demonstrated that these SNPs alter the thermostability and/or structure of the COMT transcript109, explaining why patients with functional pain disorders110–112 and exacerbated postoperative pain113–116 exhibit decreased levels of COMT alongside increased levels of catecholamines. Preclinical studies further revealed that elevated levels of epinephrine/norepinephrine resulting from low COMT activity, lead to increased pain through activation of βARs117,118. Coming full circle, results from a randomized controlled trial demonstrated that the βAR antagonist propranolol provides significant pain relief for pain patients who carry the SNPs associated with decreased levels of COMT119. Together, these findings highlight the impact of gene regulation on pain as well as the utility of genetic and protein biomarkers in identifying a subgroup of patients who will benefit from specific therapies.

In a similar fashion, we believe that measurement of alternative GPCR splice variants can be used as a diagnostic tool to provide personalized pain treatment. This is already being done in cancer. In vitro studies examining the role of NK-1R alternative splicing in breast cancer cells demonstrated that overexpression of the NK-1Rtruncated variant promotes tumorigenesis120,121. A complementary clinical study further demonstrated that individuals with overexpression of the NK-1Rtruncated variant were at increased risk for colitis-associated carcinoma, while expression levels of the canonical NK-1R remained consistent between cases and controls122.

Just as the study of alternative splicing is beginning to inform diagnosis and management of patients with cancer, the study of alternative splicing in pain-relevant GPCRs has great potential to advance the current state of clinical care for patients with chronic pain. Additionally, this line of inquiry may lead to the advent of new pain therapies such as IBNtxA, a novel opioid analgesic specifically targeting 6TM mu opioid splice variants123.

Conclusion

G-protein coupled receptors play a major role in modulating the activity of a chorus of cells involved in the transmission, modulation and perception of pain. For this reason, GPCRs are the primary target of many pharmacologic interventions used in the management of acute and chronic pain. Nonetheless, the use of these medications is limited due to variability in analgesic efficacy and side effect profiles. These limitations are partly attributed to genetic differences that influence alternative splicing of pain-relevant GPCRs. The functional importance and implications of the diversity of GPCRs in contributing to the pathophysiology of clinical pain is just beginning to emerge. More research, especially in the clinical arena, is necessary to further investigate the functions of specific GPCR splice variants, as well as the dynamic interactions between multiple variants of the same canonical receptor, within the context of pain. This line of inquiry will evolve our understanding of pain mechanisms and inform the design of new and clinically useful drugs that target specific alternative splice variants altered in a subset of patients.

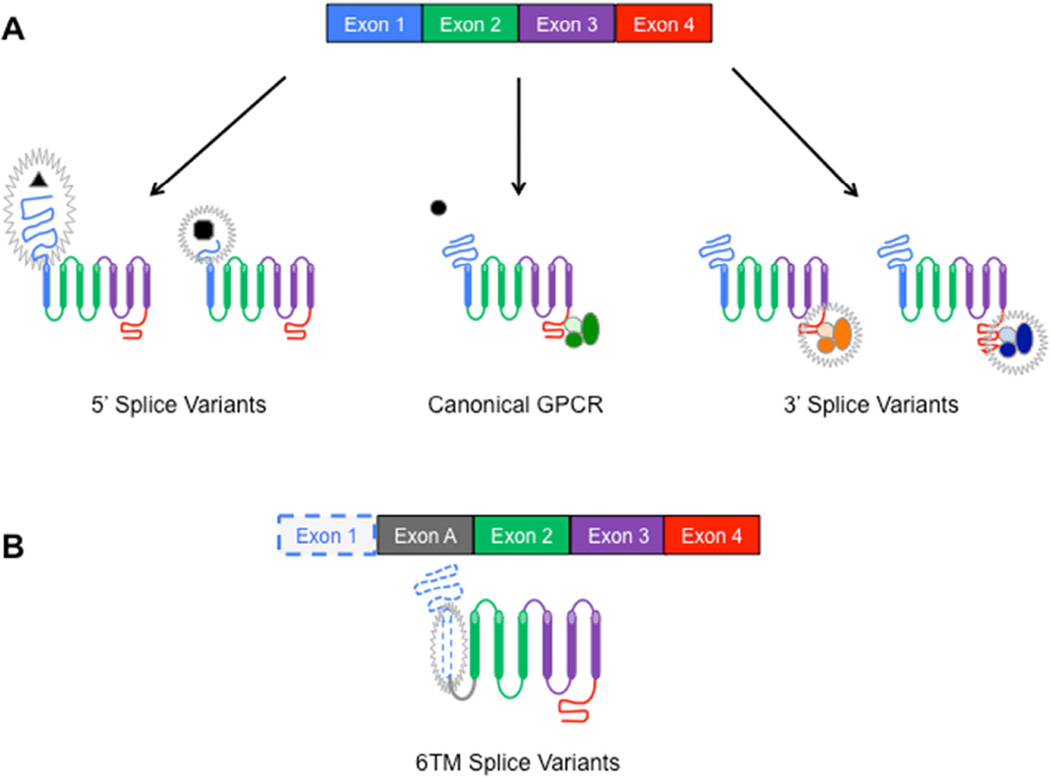

Figure 3.

Structural variations in GPCRs as a result of alternative splicing. Exons within the mRNA transcript serve as coding regions for specific sections of protein. Alternative splicing events that change or remove exonic sequences can produce GPCR splice variants with corresponding changes in protein composition and/or structure. A) For example, splicing events that lead to alterations in exon 1 can yield GPCRs with truncated N-termini that affect ligand binding, while events that lead to alterations in exon 4 can yield GPCRs with truncated C-termini that affect g-protein coupling and signaling. B) Splicing events can also lead to skipping of an exon that codes for an unit of the GPCR, such as a transmembrane, thus yielding a truncated GPCR lacking the encoded section, such as a 6 transmembrane (6TM) splice variant. Abbreviations: GPCR = G-Protein Coupled Receptor; TM = Transmembrane

Learning Objectives: On completion of this article, you should be able to (1) explain the importance of GPCRs to pain signaling and modulation; (2) explain the basic concepts of alternative splicing; and (3) describe how individual variability in alternative splicing of GPCRs may contribute to variability in the nature of pain as well as responses to analgesic drugs.

Abbreviations

- 2-AG

2-Arachidonoyglycerol

- 5-HT

5-Hydroxytryptamine

- AC

Adenylyl Cyclase

- cAMP

Cyclic Adenosine Monophosphate

- CB

Cannabinoid

- COMT

Catechol-O-Methyltransferase

- Epi

Epinephrine

- GPCR

G-protein Coupled Receptor

- GI

Gastrointestinal

- IBNtxA = IBS

Irritable Bowel Syndrome

- mRNA

messenger ribonucleic acid

- MOR-1

Mu Opioid Receptor

- NE

Norepinephrine

- NK-1R

Neurokinin-1 Receptor

- OIH

Opioid-induced Hyperalgesia

- ORL-1

Nociceptin receptor

- PKC

Protein Kinase C

- SNP

Single Nucleotide Polymorphism

- TM

Transmembrane

- αAR

Alpha adrenergic receptor

- βAR

Beta adrenergic receptor

Questions

- Which of the following medications is NOT a mu opioid receptor agonist?

- Morphine

- Fentanyl

- Hydrocodone

- Naloxone

- Methadone

- Which 5-HT receptor is exclusively targeted by triptans?

- 5-HT1

- 5-HT2

- 5-HT4

- 5-HT6

- 5-HT7

- What is the most common form of alternative splicing in humans?

- Intron Retention

- Exon Skipping

- Alternative 3’ Splice Site

- Alternative 5’ Splice Site

- Exon Retention

- Which MOR-1 splice variant contributes to opioid-induced itch?

- MOR-1A

- MOR-1D

- MOR-1G

- MOR-1K

- MOR-1S

- The α1A-2, α1A-3, and α1A-4 variants exhibit the same binding capabilities as the α1A receptor. Unlike the canonical receptor, these splice variants couple to Gαi instead of Gαs. This change in g-protein coupling is due to alternative splicing of what receptor region?

- N-terminus

- Extracellular loop 1

- C-terminus

- 1st transmembrane

- Intracellular loop 1

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: The authors report no competing interests.

References

- 1.Woolf CJ. American College of Physicians, American Physiological Society. Pain: moving from symptom control toward mechanism-specific pharmacologic management. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(6):441–451. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-8-200404200-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stone LS, Molliver DC. In search of analgesia: Emerging poles of GPCRs in pain. Mol Interv. 2009;9(5):234–251. doi: 10.1124/mi.9.5.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lundstrom K. An overview on GPCRs and drug discovery: structure-based drug design and structural biology on GPCRs. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;552:51–66. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-317-6_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alan North R. Opioid receptor types and membrane ion channels. Trends Neurosci. 1986;9:114–117. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsuda LA. Molecular aspects of cannabinoid receptors. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 1997;11(2–3):143–166. doi: 10.1615/critrevneurobiol.v11.i2-3.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michelotti GA, Price DT, Schwinn DA. Alpha 1-adrenergic receptor regulation: basic science and clinical implications. Pharmacol Ther. 2000;88(3):281–309. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(00)00092-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Summers RJ, Broxton N, Hutchinson DS, Evans BA. The Janus faces of adrenoceptors: factors controlling the coupling of adrenoceptors to multiple signal transduction pathways. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2004;31(11):822–827. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2004.04094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hannon J, Hoyer D. Molecular biology of 5-HT receptors. Behav Brain Res. 2008;195(1):198–213. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Connor M, Christie MJ. Opioid receptor signaling mechanisms. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1999;26(7):493–499. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.1999.03049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boudreau D, Korff Von M, Rutter CM, et al. Trends in long-term opioid therapy for chronic non-cancer pain. Pharmacoepidem D S. 2009;18(12):1166–1175. doi: 10.1002/pds.1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hutchinson MR, Zhang Y, Brown K, et al. Non-stereoselective reversal of neuropathic pain by naloxone and naltrexone: involvement of toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) Eur J Neurosci. 2008;28(1):20–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06321.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lynch ME, Campbell F. Cannabinoids for treatment of chronic non- cancer pain; a systematic review of randomized trials. Brit J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;72(5):735–744. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.03970.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnston MM, Rapoport AM. Triptans for the management of migraine. Drugs. 2010;70(12):1505–1518. doi: 10.2165/11537990-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Terrón JA. Is the 5-HT7 receptor involved in the pathogenesis and prophylactic treatment of migraine? Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;439(1–3):1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01436-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janice J, Kim WIK. 5-HT7 receptor signaling: improved therapeutic strategy in gut disorders. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:396. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meuser T, Pietruck C, Gabriel A, Xie G-X, Lim K-J, Pierce Palmer P. 5-HT7 receptors are involved in mediating 5-HT-induced activation of rat primary afferent neurons. Life Sci. 2002;71(19):2279–2289. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)02011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rocha-González HI, Meneses A, Carlton SM, Granados-Soto V. Pronociceptive role of peripheral and spinal 5-HT7 receptors in the formalin test. Pain. 2005;117(1):182–192. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li S-F, Zhang Y-Y, Li Y-Y, Wen S, Xiao Z. Antihyperalgesic effect of 5-HT7 receptor activation on the midbrain periaqueductal gray in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2014;127:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Max MB, Payne RG, Edwards WT. Principles of Analgesic Use in the Treatment of Acute and Cancer Pain. 4 ed. Greenview, IL: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang ET, Sandberg R, Luo S, et al. Alternative isoform regulation in human tissue transcriptomes. Nature. 2008;456(7221):470–476. doi: 10.1038/nature07509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keren H, Lev-Maor G, Ast G. Alternative splicing and evolution: diversification, exon definition and function. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11(5):345–355. doi: 10.1038/nrg2776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baralle D. Splicing in action: assessing disease causing sequence changes. J Med Gen. 2005;42(10):737–748. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.029538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kilpatrick GJ, Dautzenberg FM, Martin GR, Eglen RM. 7TM receptors: the splicing on the cake. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1999;20(7):294–301. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01355-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pan Y-X, Xu J, Xu M, Rossi GC, Matulonis JE, Pasternak GW. Involvement of exon 11-associated variants of the mu opioid receptor MOR-1 in heroin, but not morphine, actions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(12):4917–4922. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811586106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pasternak GW, Pan Y-X. Mu opioids and their receptors: Evolution of a concept. Pharmacol Rev. 2013;65(4):1257–1317. doi: 10.1124/pr.112.007138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sato M, Hutchinson DS, Bengtsson T, et al. Functional domains of the mouse beta3-adrenoceptor associated with differential G protein coupling. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;315(3):1354–1361. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.091736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boise LH, González-García M, Postema CE, et al. bcl-x, a bcl-2-related gene that functions as a dominant regulator of apoptotic cell death. Cell. 1993;74(4):597–608. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90508-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cascino I, Fiucci G, Papoff G, Ruberti G. Three functional soluble forms of the human apoptosis-inducing Fas molecule are produced by alternative splicing. J Immunol. 1995;154(6):2706–2713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gris P, Gauthier J, Cheng P, et al. A novel alternatively spliced isoform of the mu-opioid receptor: functional antagonism. Mol Pain. 2010;6(1):33. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-6-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lipscombe D, Andrade A, Allen SE. Alternative splicing: Functional diversity among voltage-gated calcium channels and behavioral consequences. BBA-Biomembranes. 2013;1828(7):1522–1529. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fruhwald J, Camacho Londono J, Dembla S, et al. Alternative splicing of a protein domain Indispensable for function of transient receptor potential melastatin 3 (TRPM3) ion channels. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(44):36663–36672. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.396663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou Y, Suzuki Y, Uchida K, Tominaga M. Identification of a splice variant of mouse TRPA1 that regulates TRPA1 activity. Nat Commun. 2013:4. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu X-Y, Liu Z-C, Sun Y-G, et al. Unidirectional cross-activation of GRPR by MOR1D uncouples itch and analgesia induced by opioids. Cell. 2011;147(2):447–458. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peng J, Sarkar S, Chang SL. Opioid receptor expression in human brain and peripheral tissues using absolute quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;124(3):223–228. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu J, Lu Z, Xu M, et al. Differential expressions of the alternatively spliced variant mRNAs of the µ opioid receptor gene, OPRM1, in brain regions of four inbred mouse strains. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(10):e111267. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wieskopf JS, Pan Y-X, Marcovitz J, et al. Broad-spectrum analgesic efficacy of IBNtxA is mediated by exon 11-associated splice variants of the mu-opioid receptor gene. Pain. 2014;155(10):2063–2070. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choi HS, Kim CS, Hwang CK, Song KY, Wang W. The opioid ligand binding of human µ-opioid receptor is modulated by novel splice variants of the receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;343(4):1132–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pasternak GW. Insights into mu opioid pharmacology: The role of mu opioid receptor subtypes. Life Sci. 2001;68(2001):2213–2219. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(01)01008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pan Y-X. Diversity and complexity of the mu opioid receptor gene: alternative pre-mRNA splicing and promoters. DNA Cell Biol. 2005;24(11):736–750. doi: 10.1089/dna.2005.24.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Majumdar S, Grinnell S, Le Rouzic V, et al. Truncated G protein-coupled mu opioid receptor MOR-1 splice variants are targets for highly potent opioid analgesics lacking side effects. Proc Natl Aca Sci USA. 2011;108(49):19778–19783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115231108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pan YX, Xu J, Mahurter L, Bolan E, Xu M, Pasternak GW. Generation of the mu opioid receptor (MOR-1) protein by three new splice variants of the Oprm gene. Proc Natl Aca Sci USA. 2001;98(24):14084–14089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241296098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu J, Xu M, Brown T, et al. Stabilization of the µ-opioid receptor by truncated single transmembrane splice variants through a chaperone-like action. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(29):21211–21227. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.458687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hawes BE, Graziano MP, Lambert DG. Cellular actions of nociceptin: transduction mechanisms. Peptides. 2000;21(7):961–967. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(00)00232-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Currò D, Yoo JH, Anderson M, Song I, Del Valle J, Owyang C. Molecular cloning of the orphanin FQ receptor gene and differential tissue expression of splice variants in rat. Gene. 2001;266(1–2):139–145. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00553-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arjomand J, Evans CJ. Differential splicing of transcripts encoding the orphanin FQ/nociceptin precursor. J Neurochem. 2001;77(3):720–729. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xie G-X, Ito E, Maruyama K, et al. An alternatively spliced transcript of the rat nociceptin receptor ORL1 gene encodes a truncated receptor. Mol Brain Res. 2000;77(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Galiegue S, Mary S, Marchand J, et al. Expression of central and peripheral cannabinoid receptors in human immune tissues and leukocyte subpopulations. Eur J Biochem. 1995;232(1):54–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ryberg E, Vu HK, Larsson N, et al. Identification and characterisation of a novel splice variant of the human CB1 receptor. FEBS Lett. 2005;579(1):259–264. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.11.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shire D, Carillon C, Kaghad M, et al. An amino-terminal variant of the central cannabinoid receptor resulting from alternative splicing. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(8):3726–3731. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.8.3726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cosenza-Nashat MA, Bauman A, Zhao ML, Morgello S, Suh HS, Lee SC. Cannabinoid receptor expression in HIV encephalitis and HIV-associated neuropathologic comorbidities. Neuropathol appl neurobiol. 2011;37(5):464–483. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2011.01177.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Benito C, Nunez E, Tolon RM, et al. Cannabinoid CB2 receptors and fatty acid amide hydrolase are selectively overexpressed in neuritic plaque-associated glia in Alzheimer’s disease brains. J Neurosci. 2003;23(35):11136–11141. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-35-11136.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yiangou Y, Facer P, Durrenberger P, et al. COX-2, CB2 and P2×7-immunoreactivities are increased in activated microglial cells/macrophages of multiple sclerosis and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis spinal cord. BMC Neurol. 2006;6(1):12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-6-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu QR, Pan CH, Hishimoto A, et al. Species differences in cannabinoid receptor 2 (CNR2 gene): identification of novel human and rodent CB2 isoforms, differential tissue expression and regulation by cannabinoid receptor ligands. Genes Brain Behav. 2009;8(5):519–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2009.00498.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chang DJ, Chang TK, Yamanishi SS, et al. Molecular cloning, genomic characterization and expression of novel human alpha1A–adrenoceptor isoforms. FEBS Lett. 1998;422(2):279–283. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Price RR, Morris DP, Biswas G, Smith MP, Schwinn DA. Acute agonist-mediated desensitization of the human 1a–adrenergic receptor is primarily independent of carboxyl terminus regulation: Implications for regulation of 1aAR splice variants. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(11):9570–9579. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111762200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Coge F, Guenin SP, Renouard-Try A, et al. Truncated isoforms inhibit [3H]prazosin binding and cellular trafficking of native human alpha1 A-adrenoceptors. Biochem J. 1999;343(Pt 1):231–239. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Daniels DV, Gever JR, Jasper JR, et al. Human cloned α1 A-adrenoceptor isoforms display α1 L-adrenoceptor pharmacology in functional studies. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;370(3):337–343. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00154-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tseng-Crank J, Kost T, Goetz A, et al. The alpha 1 C-adrenoceptor in human prostate: cloning, functional expression, and localization to specific prostatic cell types. Brit J Pharmacol. 1995;115(8):1475–1485. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb16640.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Strosberg AD. Structure and function of the beta 3-adrenergic receptor. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1997;37(1):421–450. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.37.1.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Soeder KJ, Snedden SK, Cao W, et al. The beta3-adrenergic receptor activates mitogen-activated protein kinase in adipocytes through a Gi-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(17):12017–12022. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.12017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sato M, Hutchinson DS, Evans BA, Summers RJ. Functional domains of the mouse beta(3)-adrenoceptor associated with differential G-protein coupling. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35(Pt 5):1035–1037. doi: 10.1042/BST0351035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kanno T, Yaguchi T, Nishizaki T. Noradrenaline stimulates ATP release from DRG neurons by targeting beta(3) adrenoceptors as a factor of neuropathic pain. J Cell Physiol. 2010;224(2):345–351. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Evans BA, Papaioannou M, Hamilton S, Summers RJ. Alternative splicing generates two isoforms of the beta3-adrenoceptor which are differentially expressed in mouse tissues. Brit J Pharmacol. 1999;127(6):1525–1531. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Guest PC, Salim K, Skynner HA, George SE, Bresnick JN, McAllister G. Identification and characterization of a truncated variant of the 5-hydroxytryptamine(2A) receptor produced by alternative splicing. Brain Res. 2000;876(1–2):238–244. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02664-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Canton H, Emeson RB, Barker EL, et al. Identification, molecular cloning, and distribution of a short variant of the 5-hydroxytryptamine2C receptor produced by alternative splicing. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;50(4):799–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang Q, O’Brien PJ, Chen CX, Cho DS, Murray JM, Nishikura K. Altered G protein-coupling functions of RNA editing isoform and splicing variant serotonin2C receptors. J Neurochem. 2000;74(3):1290–1300. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.741290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Blondel O, Gastineau M, Dahmoune Y, Langlois M, Fischmeister R. Cloning, expression, and pharmacology of four human 5-hydroxytryptamine 4 receptor isoforms produced by alternative splicing in the carboxyl terminus. J Neurochem. 1998;70(6):2252–2261. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70062252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pindon A, van Hecke G, van Gompel P, Lesage AS, Leysen JE, Jurzak M. Differences in signal transduction of two 5-HT4 receptor splice variants: compound specificity and dual coupling with Galphas- and Galphai/o-proteins. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;61(1):85–96. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Claeysen S, Faye P, Sebben M, Taviaux S, Bockaert J, Dumuis A. 5-HT4 receptors: cloning and expression of new splice variants. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1998;861:49–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb10172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bender E, Pindon A, van Oers I, et al. Structure of the human serotonin 5-HT4 receptor gene and cloning of a novel 5-HT4 splice variant. J Neurochem. 2000;74(2):478–489. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.740478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Irving HR, Tochon-Danguy N, Chinkwo KA, et al. Investigations into the binding affinities of different human 5-HT4 receptor splice variants. Pharmacology. 2010;85(4):224–233. doi: 10.1159/000280418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Brattelid T, Kvingedal AM, Krobert KA, et al. Cloning, pharmacological characterisation and tissue distribution of a novel 5-HT4 receptor splice variant, 5-HT4(i) N-S Arch Pharmacol. 2004;369(6):616–628. doi: 10.1007/s00210-004-0919-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vilaró MT, Cortés R, Mengod G. Serotonin 5-HT4 receptors and their mRNAs in rat and guinea pig brain: distribution and effects of neurotoxic lesions. J Comp Neurol. 2005;484(4):418–439. doi: 10.1002/cne.20447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Medhurst AD, Lezoualc’h F, Fischmeister R, Middlemiss DN, Sanger GJ. Quantitative mRNA analysis of five C-terminal splice variants of the human 5-HT4 receptor in the central nervous system by TaqMan real time RT-PCR. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2001;90(2):125–134. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(01)00095-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Coupar IM, Desmond PV, Irving HR. Human 5-HT(4) and 5-HT(7) receptor splice variants: are they important? Curr NeuroPharmacol. 2007;5(4):224–231. doi: 10.2174/157015907782793621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Claeysen S, Sebben M, Becamel C, Bockaert J, Dumuis A. Novel brain-specific 5-HT4 receptor splice variants show marked constitutive activity: role of the C-terminal intracellular domain. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;55(5):910–920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pindon A, Van Hecke G, Josson K, et al. Internalization of human 5-HT4a and 5-HT4b receptors is splice variant dependent. Bioscience Rep. 2004;24(3):215–223. doi: 10.1007/s10540-005-2582-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mialet J, Berque-Bestel I, Sicsic S, Langlois M, Fischmeister R, Lezoualc’h F. Pharmacological characterization of the human 5-HT(4(d)) receptor splice variant stably expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Brit J Pharmacol. 2000;131(4):827–835. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Vilaro MT, Doménech T, Palacios JM, Mengod G. Cloning characterization of a novel human 5-HT4 receptor variant that lacks the alternatively spliced carboxyl terminal exon. RT-PCR distribution in human brain and periphery of multiple 5-HT4 receptor variants. Neuropharmacology. 2002;42(1):60–73. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00154-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Olsen MA, Nawoschik SP, Schurman BR, et al. Identification of a human 5-HT6 receptor variant produced by alternative splicing. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1999;64(2):255–263. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(98)00338-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jasper JR, Kosaka A, To ZP, Chang DJ, Eglen RM. Cloning, expression and pharmacology of a truncated splice variant of the human 5-HT 7 receptor (h5-HT 7(b) ) Brit J Pharmacol. 1997;122(1):126–132. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Krobert K, Bach T, Syversveen T, Kvingedal A, Levy F. The cloned human 5-HT 7 receptor splice variants: a comparative characterization of their pharmacology, function and distribution. N-S Arch Pharmacol. 2001;363(6):620–632. doi: 10.1007/s002100000369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mahé C, Bernhard M, Bobirnac I, et al. Functional expression of the serotonin 5-HT7 receptor in human glioblastoma cell lines. Brit J Pharmacol. 2004;143(3):404–410. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mahé C, Loetscher E, Dev KK, Bobirnac I, Otten U, Schoeffter P. Serotonin 5-HT7 receptors coupled to induction of interleukin-6 in human microglial MC-3 cells. Neuropharmacology. 2005;49(1):40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Guthrie CR, Murray AT, Franklin AA, Hamblin MW. Differential agonist-mediated internalization of the human 5-hydroxytryptamine 7 receptor isoforms. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;313(3):1003–1010. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.081919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sugimoto Y, Narumiya S. Prostaglandin E receptors. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(16):11613–11617. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600038200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lai JP, Ho WZ, Kilpatrick LE, et al. Full-length and truncated neurokinin-1 receptor expression and function during monocyte/macrophage differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(20):7771–7776. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602563103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Muñoz M, Coveñas R. Involvement of substance P and the NK-1 receptor in human pathology. Amino Acids. 2014;46(7):1727–1750. doi: 10.1007/s00726-014-1736-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lai JP, Lai S, Tuluc F, et al. Differences in the length of the carboxyl terminus mediate functional properties of neurokinin-1 receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(34):12605–12610. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806632105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Xu J, Faskowitz AJ, Rossi GC, et al. Stabilization of morphine tolerance with long-term dosing: Association with selective upregulation of mu-opioid receptor splice variant mRNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(1):279–284. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1419183112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Oladosu F, OBuckley S, Nackley AG. Elucidating the role of MOR-1K in opioid-induced hyperalgesia via siRNA gene knockdown. International Association for the Study of Pain. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 92.Grinnell SG, Majumdar S, Narayan A, et al. Pharmacologic characterization in the rat of a potent analgesic lacking respiratory depression, IBNtxA. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2014;350(3):710–718. doi: 10.1124/jpet.114.213199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Majumdar S, Grinnell S, Le Rouzic V, et al. Truncated G protein-coupled mu opioid receptor MOR-1 splice variants are targets for highly potent opioid analgesics lacking side effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(49):19778–19783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115231108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Xie G-X, Meuser T, Pietruck C, Sharma M, Palmer PP. Presence of opioid receptor-like (ORL1) receptor mRNA splice variants in peripheral sensory and sympathetic neuronal ganglia. Life Sci. 1999;64(22):2029–2037. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kaushal S, Ridge KD, Khorana HG. Structure and function in rhodopsin: the role of asparagine-linked glycosylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91(9):4024–4028. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.4024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hawrylyshyn KA, Michelotti GA, Coge F, Guenin SP, Schwinn DA. Update on human alpha1-adrenoceptor subtype signaling and genomic organization. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25(9):449–455. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Silver K, Walston J, Yang Y, et al. Molecular scanning of the beta-3-adrenergic receptor gene in Pima Indians and Caucasians. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 1999;15(3):175–180. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-7560(199905/06)15:3<175::aid-dmrr34>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Spronsen A, Nahmias C, Krief S, Briend-Sutren M-M, Strosberg AD, Emorine LJ. The promoter and intron/exon structure of the human and mouse β3-adrenergic- receptor genes. Eur J Biochem. 1993;213(3):1117–1124. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Nakae A, Nakai K, Tanaka T, Hosokawa K, Mashimo T. Serotonin 2C receptor alternative splicing in a spinal cord injury model. Neurosci Lett. 2013;532:49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Milligan G. Constitutive activity and inverse agonists of G protein-coupled receptors: a current perspective. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;64(6):1271–1276. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.6.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Krobert KA, Levy FO. The human 5-HT7 serotonin receptor splice variants: constitutive activity and inverse agonist effects. Brit J Pharmacol. 2002;135(6):1563–1571. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gellynck E, Heyninck K, Andressen KW, et al. The serotonin 5-HT7 receptors: two decades of research. Exp Brain Res. 2013;230(4):555–568. doi: 10.1007/s00221-013-3694-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Natura G, Bär K-J, Eitner A, et al. Neuronal prostaglandin E2 receptor subtype EP3 mediates antinociception during inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(33):13648–13653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300820110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Minami T. Functional evidence for interaction between prostaglandin EP3 and κ-opioid receptor pathways in tactile pain induced by human immunodeficiency virus type-1 (HIV-1) glycoprotein gp120. Neuropharmacology. 2003;45(1):96–105. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(03)00133-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Patwardhan AM, Vela J, Farugia J, Vela K, Hargreaves KM. Trigeminal nociceptors express prostaglandin receptors. J Dent Res. 2008;87(3):262–266. doi: 10.1177/154405910808700306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tillisch K, Labus J, Nam B, et al. Neurokinin-1-receptor antagonism decreases anxiety and emotional arousal circuit response to noxious visceral distension in women with irritable bowel syndrome: a pilot study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35(3):360–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04958.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Diatchenko L, Nackley AG, Slade GD, Fillingim RB, Maixner W. Idiopathic pain disorders--pathways of vulnerability. Pain. 2006;123(3):226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Diatchenko L. Genetic basis for individual variations in pain perception and the development of a chronic pain condition. Hum Mol Gene. 2004;14(1):135–143. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Nackley AG, Shabalina SA, Tchivileva IE, et al. Human Catechol-o-methyltransferase haplotypes modulate protein expression by altering mRNA secondary structure. Science. 2006;314(5807):1930–1933. doi: 10.1126/science.1131262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Cheung KMC. The relationship between disc degeneration, low back pain, and human pain genetics. Spine J. 2010;10(11):958–960. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Orrey DC, Bortsov AV, Hoskins JM, et al. Catechol-o-methyltransferase genotype predicts pain severity in hospitalized burn Patients. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33(4):518–523. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e31823746ed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Smith SB, Reenilä I, Männistö PT, et al. Epistasis between polymorphisms in COMT, ESR1, and GCH1 influences COMT enzyme activity and pain. Pain. 2014;155(11):2390–2399. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kolesnikov Y, Gabovits B, Levin A, Voiko E, Veske A. Combined catechol-o-methyltransferase and µ-Opioid receptor gene polymorphisms affect morphine postoperative analgesia and central side effects. Anesth Analg. 2011;112(2):448–453. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e318202cc8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Tan E-C, Lim ECP, Ocampo CE, Allen JC, Sng B-L, Sia AT. Common variants of catechol-o-methyltransferase influence patient-controlled analgesia usage and postoperative pain in patients undergoing total hysterectomy. Pharmacogen J. 2015:1–7. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2015.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]