Significance

The work identifies the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4B (eIF4B) as a substrate of maternal and embryonic leucine zipper kinase (MELK), a mitotic kinase known to be essential for aggressive types of malignancy. The MELK–eIF4B axis thus represents a previously unidentified signaling pathway that regulates protein synthesis during mitosis and, consequently, the survival of cancer cells.

Keywords: MELK, eIF4B, MCL1, protein synthesis, mitosis

Abstract

The protein kinase maternal and embryonic leucine zipper kinase (MELK) is critical for mitotic progression of cancer cells; however, its mechanisms of action remain largely unknown. By combined approaches of immunoprecipitation/mass spectrometry and peptide library profiling, we identified the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4B (eIF4B) as a MELK-interacting protein during mitosis and a bona fide substrate of MELK. MELK phosphorylates eIF4B at Ser406, a modification found to be most robust in the mitotic phase of the cell cycle. We further show that the MELK–eIF4B signaling axis regulates protein synthesis during mitosis. Specifically, synthesis of myeloid cell leukemia 1 (MCL1), an antiapoptotic protein known to play a role in cancer cell survival during cell division, depends on the function of MELK-elF4B. Inactivation of MELK or eIF4B results in reduced protein synthesis of MCL1, which, in turn, induces apoptotic cell death of cancer cells. Our study thus defines a MELK–eIF4B signaling axis that regulates protein synthesis during mitosis, and consequently influences cancer cell survival.

Maternal and embryonic leucine zipper kinase (MELK) is a serine/threonine kinase with potential roles in mitosis. Similar to other established mitotic factors, such as Aurora kinases and cyclin B1, MELK demonstrates increased protein abundance during mitosis and is degraded when cells progress into G1 phase (1, 2). Our recent study proposed an essential role of MELK in the mitotic progression of specific cancer cell types, with MELK knockdown resulting in multiple mitotic defects, including G2/M arrest and mitotic cell death (2). Despite these advances, there is a lack of mechanistic understanding of the role of MELK during cell division. An immediate question is the identity of the MELK substrates that mediate its role in mitosis, such as promoting mitotic cell survival.

Myeloid cell leukemia 1 (MCL1) is an important negative regulator of apoptosis. Uniquely among the Bcl-2 family, it is turned over rapidly by ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis and must be continuously resupplied by translation (3, 4). Protein abundance of MCL1 decreases during prolonged mitotic arrest induced by antimicrotubule drugs, rendering arrested cells highly sensitive to inhibitors of other Bcl-2 family members (5). We thus speculate that synthesis of MCL1 is important for cell survival during normal and drug-arrested mitosis and, conversely, that a drug that decreases MCL1 synthesis during mitosis might have anticancer potential.

The rate of protein synthesis and other basic biological processes, such as DNA or RNA biogenesis, fluctuates throughout the cell cycle. Overall protein synthesis significantly decreases when cells enter mitosis (6, 7), consistent with the notion that macromolecule synthesis predominantly occurs in interphase before the segregation of cellular mass in mitosis.

A recent study based on ribosome profiling identified a set of genes that are translationally repressed in mitosis, and proposed that suppressed protein synthesis might provide a unique mechanism to complement the posttranslational inactivation of specific proteins (8). Nevertheless, protein synthesis still occurs during mitosis, although at an overall rate that is 30–65% of the overall rate in interphase cells (6, 8, 9). Moreover, the translation of certain mRNAs, such as c-Myc, MCL1, and ornithine decarboxylase (ODC), is even elevated during mitosis (8, 9). Together, these studies suggest that protein synthesis may be functionally important for mitotic cells and might be finely regulated by as yet unidentified signaling pathways.

In this study, we aimed to identify downstream effectors of the mitotic kinase MELK. Intriguingly, we found that MELK phosphorylates the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4B (eIF4B). Our data implicate the MELK–eIF4B pathway as a previously unrecognized signaling mechanism regulating mitotic protein synthesis and tumor cell survival.

Results

Peptide Library Screen Identifies the Optimal Substrate Motif for MELK.

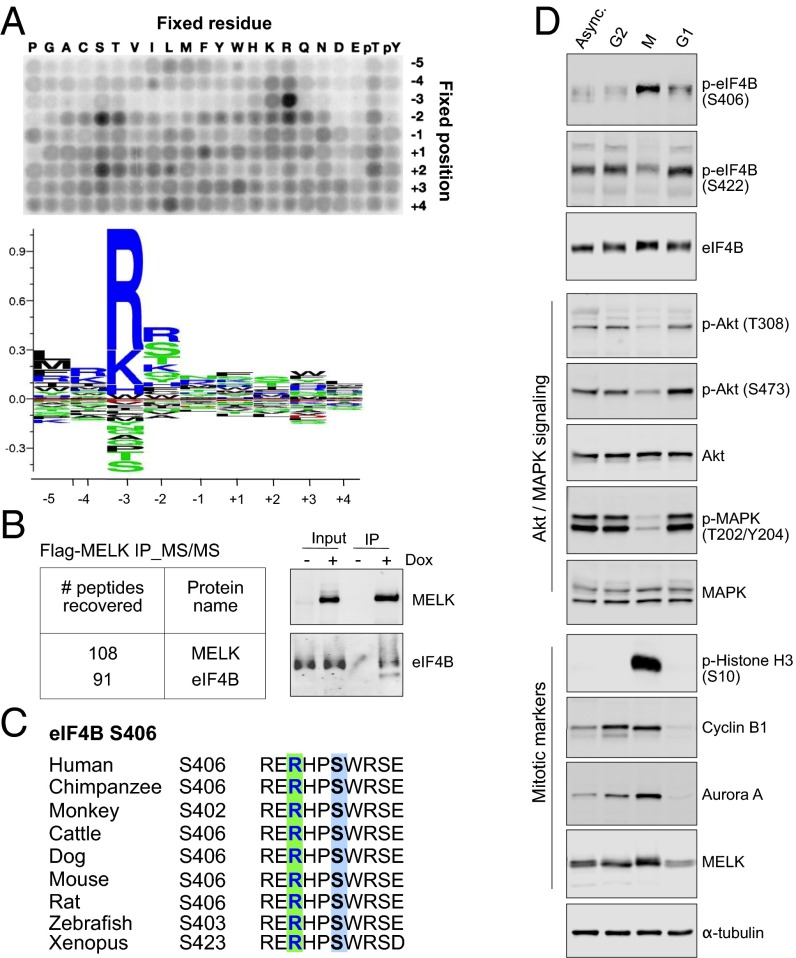

To identify kinase substrates of MELK that mediate its role in the regulation of mitosis and cell survival, we determined the consensus phosphorylation motif for MELK. Proteins carrying the optimal substrate motif are likely phosphorylated by MELK, and thus represent potential in vivo substrates. We expressed active full-length human MELK in insect cells and subjected the purified kinase to positional scanning peptide library screening, a technique that has been used extensively to identify optimal substrate motifs for kinases (10, 11). The profiling demonstrated that MELK is highly selective for its substrate, with a strong preference for arginine at the −3 position relative to the phosphoacceptor site (Fig. 1A). In addition, arginine was positively selected in the −2 and −4 positions, and hydrophobic residues were strongly selected against in the −3 position (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Consensus phosphorylation motif for MELK. (A) Positional scanning peptide library (PSPL) screen identified the optimal phosphorylation motif for MELK. (Top) Phosphor imaging of a PSPL screen after in vitro reaction with recombinant full-length MELK and radiolabeled ATP. Each peptide contains one fixed residue at one of nine positions relative to the centrally fixed phosphoacceptor (serine or threonine). Reactions were spotted onto a membrane and exposed to a phosphor storage screen. (Bottom) Sequence motif generated using quantified and normalized data from the above screen. (B) Immunoprecipitation (IP)/mass spectrometric (MS) assay identified MELK–eIF4B interaction during mitosis. MDA-MB-468 cells stably transduced with doxycycline (Dox)-inducible Flag-tagged MELK were left untreated or treated with Dox (100 ng/mL) for 3 d, followed by overnight treatment with nocodazole. Mitotic cells were harvested for IP using anti-Flag magnetic beads. The bound fractions were eluted and subjected to tandem mass spectrometric (MS/MS) analysis. (Left) Chart indicates the recovered peptide reads. (Right) Immunoblots show the interaction between eIF4B and Flag-MELK in mitotic lysates. (C) S406 and the upstream (−3) arginine are highly conserved across evolution. (D) EIF4B phosphorylation and Akt/MAPK signaling during cell cycling. MDA-MB-468 cells were either untreated [asynchronized (Async.)] or treated with nocodazole overnight to obtain floating mitotic cells (M) and attached cells that are enriched for cells in G2 phase. A sample of the mitotic cells was washed and incubated with nocodazole-free medium for 4 h to release cells into G1 phase. Cells were subjected to immunoblot analysis as indicated.

Because bioinformatics analysis revealed a large number of proteins carrying the optimal motif, we sought another approach to narrow down the hits. We reasoned that proteins that physically interact with MELK during mitosis might represent potential substrates. To identify such proteins, we stably introduced doxycycline-inducible Flag-tagged MELK into the breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-468 and immunoprecipitated Flag-MELK from lysates of mitotic cells obtained by nocodazole-induced cell cycle arrest at prometaphase. Tandem mass spectrometric analysis identified high enrichment of MELK together with eIF4B (Fig. 1B and Table S1), a translation initiation factor with roles in regulating cell survival (12). The MELK–eIF4B interaction was further confirmed by ectopic expression of MELK or eIF4B in HEK293T cells (Fig. S1A).

Table S1.

Peptides recovered from Flag-MELK IP

| Total peptides | Total peptides | Matched protein |

| 84 | 166 | LRPPRC_IPI:IPI00783271.1 |

| 78 | 151 | FLNA_IPI:IPI00302592.2 |

| 47 | 108 | MELK_IPI:IPI00006471.3 |

| 35 | 91 | EIF4B_IPI:IPI00012079.3 |

| 33 | 37 | MYH9_IPI:IPI00019502.3 |

| 32 | 48 | ACAP2_IPI:IPI00014264.5 |

| 29 | 49 | HSPA5_IPI:IPI00003362.2 |

| 29 | 76 | STK38_IPI:IPI00027251.1 |

| 27 | 28 | ROCK1_IPI:IPI00022542.1 |

| 26 | 55 | PRMT5_IPI:IPI00064328.3 |

| 26 | 73 | LANCL2_IPI:IPI00032995.1 |

| 24 | 42 | HSPA8_IPI:IPI00003865.1 |

| 24 | 34 | HSPA9_IPI:IPI00007765.5 |

| 23 | 29 | DHX15_IPI:IPI00396435.3 |

| 22 | 23 | CCT8_IPI:IPI00302925.4 |

| 21 | 32 | ANKFY1_IPI:IPI00159899.9 |

| 19 | 26 | CCT2_IPI:IPI00297779.7 |

| 19 | 24 | GLUD1_IPI:IPI00016801.1 |

| 18 | 22 | TCP1_IPI:IPI00290566.1 |

| 18 | 23 | CCT3_IPI:IPI00290770.3 |

| 18 | 20 | DDX42_IPI:IPI00409671.3 |

| 18 | 18 | LMNA_IPI:IPI00021405.3 |

| 18 | 18 | THBS1_IPI:IPI00296099.6 |

| 17 | 23 | TUFM_IPI:IPI00027107.5 |

| 17 | 23 | EGFR_IPI:IPI00018274.1 |

| 16 | 21 | VCP_IPI:IPI00022774.3 |

| 16 | 20 | HSP90B1_IPI:IPI00027230.3 |

| 15 | 19 | SERPINH1_IPI:IPI00032140.4 |

| 15 | 19 | CCT7_IPI:IPI00018465.1 |

| 15 | 15 | SUPT16H_IPI:IPI00026970.4 |

| 14 | 23 | ILK-2_IPI:IPI00302927.6 |

| 14 | 16 | CCT5_IPI:IPI00010720.1 |

| 14 | 15 | PABPC1_IPI:IPI00008524.1 |

| 13 | 19 | HSP90AA1_IPI:IPI00382470.3 |

| 13 | 17 | RBM10_IPI:IPI00375731.1 |

| 12 | 16 | CTTN_IPI:IPI00029601.6 |

| 12 | 24 | C11orf84_IPI:IPI00106955.3 |

| 12 | 18 | PDIA6_IPI:IPI00299571.5 |

| 12 | 12 | ATP5A1_IPI:IPI00440493.2 |

| 12 | 12 | MTHFD1L_IPI:IPI00291646.3 |

| 12 | 16 | GSTK1_IPI:IPI00219673.6 |

| 12 | 12 | ATP5B_IPI:IPI00303476.1 |

| 12 | 17 | HSP90AB1_IPI:IPI00414676.6 |

| 12 | 13 | PRKDC_IPI:IPI00296337.2 |

| 11 | 14 | HTATSF1_IPI:IPI00013788.1 |

| 11 | 12 | SMEK1_IPI:IPI00017290.4 |

| 11 | 11 | HSPD1_IPI:IPI00784154.1 |

| 11 | 14 | STK38L_IPI:IPI00237011.5 |

| 11 | 12 | RPS3_IPI:IPI00011253.3 |

| 11 | 14 | PPIB_IPI:IPI00646304.4 |

| 11 | 16 | TRIM21_IPI:IPI00018971.8 |

| 11 | 12 | MCM5_IPI:IPI00018350.3 |

| 10 | 11 | SYNCRIP_IPI:IPI00018140.3 |

| 10 | 19 | TUBB2C_IPI:IPI00007752.1 |

| 10 | 10 | SNRNP200_IPI:IPI00420014.2 |

| 10 | 15 | SMEK1_IPI:IPI00217013.2 |

| 10 | 11 | CCT6A_IPI:IPI00027626.3 |

| 10 | 10 | HDLBP_IPI:IPI00022228.2 |

| 10 | 10 | HADHA_IPI:IPI00031522.2 |

| 10 | 11 | SQRDL_IPI:IPI00009634.1 |

| 10 | 14 | TUBA4A_IPI:IPI00007750.1 |

| 10 | 10 | RPS9_IPI:IPI00221088.5 |

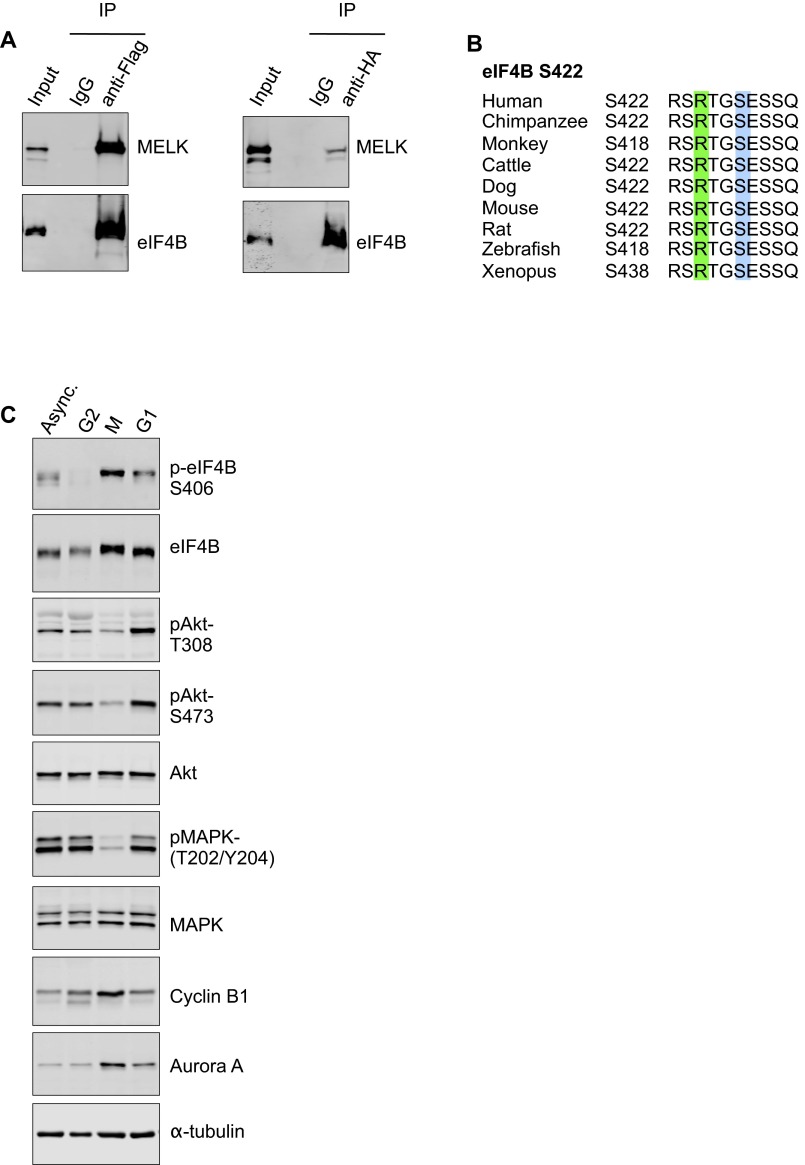

Fig. S1.

eIF4B phosphorylation in mitotic cells. (A) MELK interacts with eIF4B. HEK293T cells were transfected with Flag-tagged MELK (Left) or HA-tagged eIF4B (Right). At 36 h after transfection, cell lysates were prepared and incubated with magnetic beads conjugated with anti-Flag (Left), anti-HA (Right), or control IgG. Samples were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-MELK or anti-eIF4B antibodies. (B) S422 and upstream (−3) arginine are highly conserved throughout evolution. (C) Phosphorylation of eIF4B and Akt/MAPK during the cell cycle. MDA-MB-468 cells were either left untreated [asynchronized (Async.)] or treated with paclitaxel (100 nM) for 18 h. Mitotic cells (M) were isolated by shake-off, and the attached cells enriched for G2 phase were harvested. A sample of the M was washed and released into G1 phase after 4 h of incubation in the absence of paclitaxel. Cell lysates were prepared in radioimmunoassay precipitation (RIPA) buffer and subjected to immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies.

We proceeded to examine whether eIF4B carries the optimal substrate motif for MELK. Two serine residues of eIF4B, Ser406 and Ser422, conformed to the consensus phosphorylation sequence (Fig. 1C and Fig. S1B). In addition, S406/S422 and their flanking residues are evolutionarily conserved across vertebrates (Fig. 1C and Fig. S1B), indicating that these residues might be subject to posttranslational modifications. Together, these findings suggest that eIF4B might be a protein substrate of MELK.

EIF4B Phosphorylation During Mitosis.

Given that MELK is a mitotic kinase, its potential role in regulating eIF4B phosphorylation drove us to investigate first how eIF4B phosphorylation occurs at different stages of the cell cycle. We harvested mitotic MDA-MB-468 cells at prometaphase through nocodazole- or paclitaxel-induced cell cycle arrest. As expected, the cells were enriched for mitotic factors, including MELK, cyclin B1, and Aurora kinase A, and, interestingly, exhibited strong phosphorylation of eIF4B at Ser406, but not at Ser422 (Fig. 1D and Fig. S1C). In contrast, phosphorylation of some of the known upstream signaling molecules, such as Akt or MAPK (13), was apparently decreased in mitotic cells (Fig. 1D and Fig. S1C).

MELK Directly Phosphorylates eIF4B at Ser406.

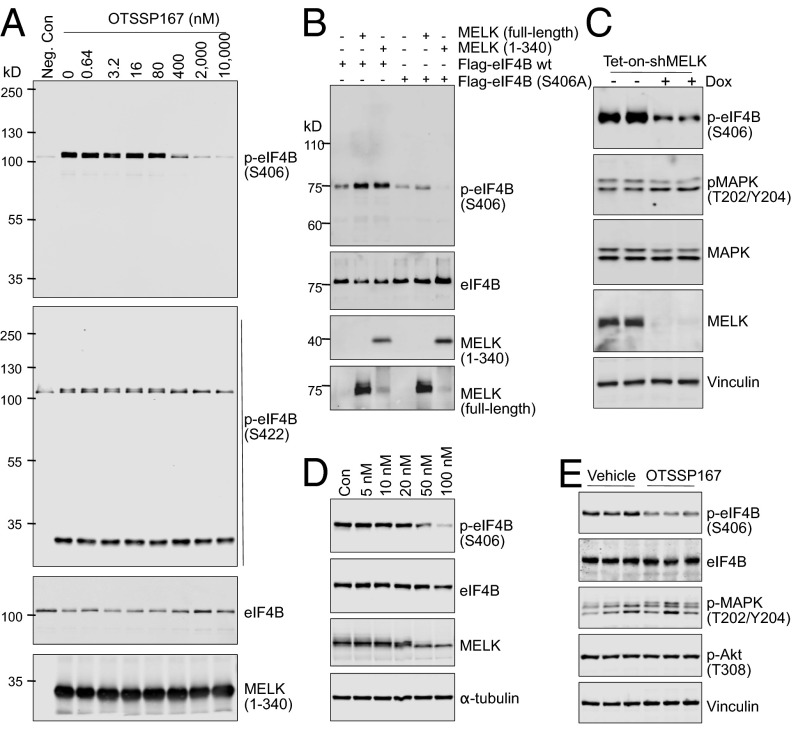

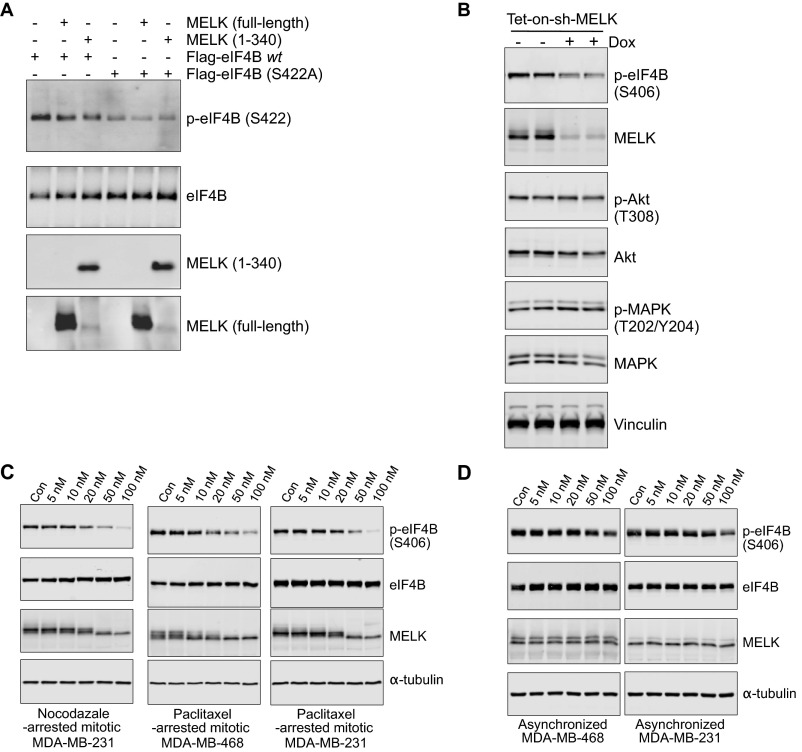

To investigate whether MELK phosphorylates eIF4B, we first performed in vitro kinase assays using purified recombinant MELK and eIF4B. MELK potently induced phosphorylation of eIF4B at Ser406, and to a lesser extent at Ser422, as indicated by immunoblot analysis with phospho-specific antibodies (Fig. 2A). We also examined the effect of chemical inhibition of MELK kinase activity using OTSSP167 (14), and found that the inhibitor efficiently suppressed MELK-driven eIF4B phosphorylation at Ser406 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A). To confirm that MELK is a bona fide kinase for eIF4B, we performed kinase reactions consisting of MELK (full-length or kinase domain) together with eIF4B (wild type or with mutations introduced at Ser406 or Ser422). The immunoprecipitated eIF4B was readily phosphorylated at Ser406 by full-length MELK or its kinase domain (Fig. 2B), and, as expected, the phosphorylation was abolished when serine was mutated to alanine (S406A) (Fig. 2B). In contrast, MELK was unable to catalyze the phosphorylation of eIF4B at S422 (Fig. S2A).

Fig. 2.

MELK regulates the phosphorylation of eIF4B. (A) MELK phosphorylates recombinant eIF4B selectively at Ser406. Recombinant GST-eIF4B (240 ng per reaction) was incubated without [negative control (Neg. Con), first lane] or with (1 μg per reaction) MELK kinase in the presence of OTSSP167 (0.64–10,000 nM; DMSO was used as a vehicle control, second lane). ATP was used at a final concentration of 300 μM. After incubation for 30 min at room temperature, the reaction was terminated and the samples were subjected to immunoblotting. Note that anti–p-eIF4B (S4222) also recognizes MELK. The relatively high concentration of OTSSP167 needed to suppress eIF4B phosphorylation is likely due to the high concentration of MELK protein (∼500 nM) used in the assay. (B) MELK phosphorylates immunoprecipitated eIF4B at Ser406 in vitro. Recombinant full-length or kinase domain of MELK was subjected to in vitro kinase assay using immunoprecipitated Flag-eIF4B [wild type (wt)] or Flag-eIF4B (S406A). Reactions were analyzed by immunoblotting. (C) MELK knockdown inhibits eIF4B phosphorylation at S406. MDA-MB-468 cells stably transduced with Dox-inducible short hairpin MELK (shMELK) were left untreated or treated with Dox. Mitotic cells were harvested, and lysates were subjected to immunoblotting. (D) Submicromolar doses of OTSSP167 inhibit eIF4B phosphorylation in mitotic cells. Mitotic MDA-MB-468 cells were harvested by nocodazole-induced prometaphase arrest and treated for 30 min with increasing concentrations of OTSSP167 in the presence of nocodazole (200 ng/mL) and MG132 (10 μM). Lysates were subjected to immunoblotting. Note that inhibition of eIF4B phosphorylation correlates with altered electrophoretic mobility of MELK. (E) OTSSP167 inhibits eIF4B phosphorylation in vivo. Mice with breast cancer cell xenografts were treated with vehicle (0.5% methylcellulose) or OTSSP167 (5 mg/kg) for 13 d. Tumors were isolated and radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysates were subjected to immunoblotting. Note that phosphorylation of eIF4B, but not Akt or MAPK, was inhibited by OTSSP167. Each lane represents one independent tumor sample.

Fig. S2.

MELK phosphorylates eIF4B specifically at Ser406. (A) MELK does not phosphorylate eIF4B at S422 in vitro. Recombinant full-length or kinase domain of MELK was subjected to in vitro kinase assay using immunoprecipitated Flag-eIF4B [wild type (wt)] or Flag-eIF4B (S422A). Reactions were analyzed by immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies. (B) Doxycycline (Dox)-inducible knockdown of MELK decreases mitotic phosphorylation of eIF4B at S406. BT549 cells stably transduced with tet-on-shMELK were either left untreated or treated with Dox (100 ng/mL). After 3 d, the cells were treated with nocodazole (200 ng/mL) for 20 h. Mitotic cells were harvested by shake-off. Lysates were prepared in RIPA buffer and subjected to immunoblotting. (C) MELK inhibition impairs eIF4B phosphorylation at S406 in nocodazole or paclitaxel-arrested mitotic cells. Indicated cell lines were prepared and treated with OTSSP167 at different concentrations for 30 min. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting. (D) Asynchronized cells were treated with OTSSP167 at indicated concentrations for 30 min, and cell lysates were prepared for immunoblotting. Note that a high dose of OTSSP167 (100 nM) causes significant suppression of eIF4B phosphorylation. Con, control.

To test whether eIF4B phosphorylation in mitotic cells is regulated by MELK, we used a doxycycline-inducible shRNA platform to knock down MELK expression (15) and found that Ser406 phosphorylation of eIF4B in mitotic cells (MDA-MB-468, BT549) was strongly suppressed by the loss of MELK (Fig. 2C and Fig. S2B). Moreover, the MELK inhibitor OTSSP167 reduced eIF4B phosphorylation in mitotic cells at concentrations in the nanomolar range. Interestingly, OTSSP167 concurrently increased the electrophoretic mobility of MELK (Fig. 2D and Fig. S2C), suggesting possible dephosphorylation and inactivation of MELK. Together, data from in vitro and in vivo assays point to a predominant role of MELK in phosphorylating eIF4B at Ser406 in mitotic cells.

Both MELK expression and eIF4B phosphorylation, although most abundant during mitosis, were also observed in interphase, such as in cells in G1 phase (Fig. 1D), suggesting that MELK might also contribute to eIF4B phosphorylation outside of mitosis. Indeed, MELK inhibition in asynchronized cells (MDA-MB-468 and MDA-MB-231) caused a significant, albeit reduced, inhibition of eIF4B phosphorylation (Fig. S2D). In addition, treatment of mice bearing xenografted MDA-MB-231 tumors with OTSSP167 resulted in reduced phosphorylation of eIF4B at Ser406 in the absence of suppressed Akt/MAPK signaling (Fig. 2E). These observations indicate that the role of MELK in phosphorylating eIF4B is most prominent in mitosis but might extend to other cell cycle stages.

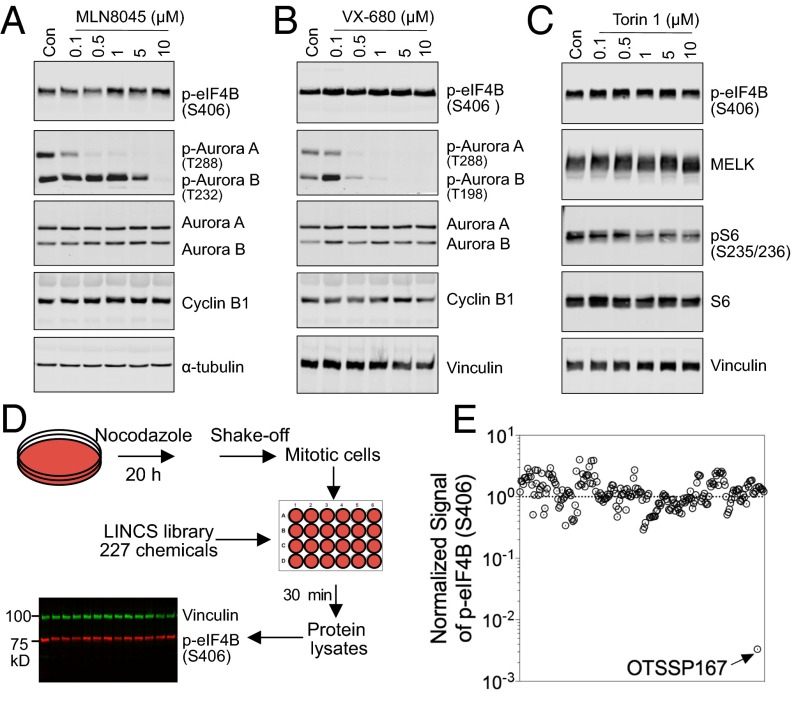

Chemical Library Screen Identifies MELK as the Unique Mitotic Kinase Phosphorylating eIF4B.

We next investigated whether MELK is the only kinase responsible for eIF4B phosphorylation during mitosis. A large number of kinases are expressed in mitotic cells, including Aurora kinases, CDK1, MPS1, and PLK1. Recent studies also documented hyperactivation of mTOR complex 1 during mitosis despite the fact that the protein abundance of mTOR does not fluctuate during the cell cycle, unlike the established mitotic kinases (7). We first tested whether inhibition of Aurora kinases affects eIF4B phosphorylation. Both MLN8045 and VX-680 (16, 17) suppressed the autophosphorylation of Aurora A and Aurora B (at a high dose for MLN8045) but failed to decrease, and in fact even enhanced, eIF4B phosphorylation (Fig. 3 A and B). Similarly, the highly potent ATP-competitive inhibitor of mTOR Torin 1 (18) was also unable to inhibit eIF4B phosphorylation (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

MELK-specific regulation of eIF4B phosphorylation during mitosis. (A and B) Insensitivity of eIF4B phosphorylation (S406) to inhibition of Aurora kinases. Mitotic cells were harvested by shake-off following overnight treatment with nocodazole (200 ng/mL) and treated with increasing concentrations of MLN8045 (A) or VX-680 (B) for 30 min in the presence of nocodazole and MG132 (10 μM). Cells were harvested for immunoblotting. Con, control. (C) Insensitivity of eIF4B phosphorylation (S406) to mTOR inhibition. The assay was performed as in A and B, but in the presence of the mTOR inhibitor Torin 1. (D) Schematic diagram of the chemical library screen for small molecules that inhibit S406 phosphorylation of eIF4B. Mitotic cells were harvested by shake-off after treatment with nocodazole and exposed to 227 small inhibitors individually at a final concentration of 5 μM. RIPA lysates were subjected to fluorescent immunoblotting with anti–p-eIF4B (S406) and antivinculin (loading control) antibodies. (E) Normalized signals of eIF4B phosphorylation from the chemical library screen. Note that OTSSP167 was the strongest inhibitor of eIF4B phosphorylation among all of the chemicals tested.

To study systemically whether other kinases besides MELK are involved in regulating mitotic phosphorylation of eIF4B, we screened a chemical library for any compounds capable of suppressing eIF4B signaling. The Library of Integrated Network-Based Cellular Signatures (LINCS) project has collected and characterized more than 200 kinase inhibitors, most of which are commercially available (https://lincs.hms.harvard.edu/). We screened this panel at a single dose of 5 μM by incubation with nocodazole-arrested mitotic cells (MDA-MB-231) for 30 min, followed by immunoblot analysis of phospho-eIF4B (Ser406) (Fig. 3D). Of the 227 kinase inhibitors tested, only OTSSP167 showed robust inhibition of mitotic eIF4B phosphorylation at Ser406 (Fig. 3E and Table S2). Therefore, we concluded that MELK inhibition uniquely induced potent inhibition of mitotic phosphorylation of eIF4B.

Table S2.

Chemical library screen for inhibitors suppressing eIF4B phosphorylation

| SM HMS LINCS ID | SM name | Alternative names | LINCS ID | PubChem CID | Normalized p-eIF4B (S406)/vinculin |

| 10001-101 | (R)-Roscovitine | CYC202; Seliciclib | LSM-1001 | 160355 | 1.197703546 |

| 10002-101 | ALW-II-38-3 | LSM-1002 | 24880028 | 1.796850516 | |

| 10003-101 | ALW-II-49-7 | LSM-1003 | 24875320 | 1.784969631 | |

| 10004-101 | AT-7519 | LSM-1004 | 11338033 | 1.601992176 | |

| 10005-101 | Tivozanib | AV-951 | LSM-1005 | 9911830 | 2.038550714 |

| 10006-101 | AZD7762 | LSM-1006 | 67077825 | 2.063442535 | |

| 10007-101 | AZD8055 | LSM-1007 | 25262965 | 1.902014416 | |

| 10008-101 | Sorafenib | BAY-439006 | LSM-1008 | 216239 | 2.875109974 |

| 10009-101 | CP466722 | LSM-1009 | 44551660 | 2.121151961 | |

| 10010-101 | CP724714 | LSM-1010 | 53401057 | 2.50132975 | |

| 10011-101 | Flavopiridol | Alvocidib; HMR-1275; L868275 | LSM-1011 | 5287969 | 2.12465869 |

| 10012-101 | GSK429286A | LSM-1012 | 11373846 | 1.556566278 | |

| 10013-101 | GSK461364 | LSM-1013 | 15983966 | 0.509226884 | |

| 10014-101 | GW843682 | LSM-1014 | 9826308 | 1.069507822 | |

| 10015-101 | HG-5-113-01 | LSM-5982 | 25226483 | 2.717613168 | |

| 10016-101 | HG-5-88-01 | LSM-5245 | 25226117 | 1.654874065 | |

| 10017-101 | HG-6-64-01 | KIN001-206 | LSM-1017 | 2.691833536 | |

| 10018-101 | Neratinib | HKI-272 | LSM-1018 | 53398697 | 1.056430224 |

| 10019-101 | JW-7-24-1 | LSM-5674 | 69923936 | 1.308477581 | |

| 10020-101 | Dasatinib | BMS-354825; Sprycel | LSM-1020 | 3062316 | 1.447588823 |

| 10021-101 | Tozasertib | VX680; MK-0457 | LSM-1021 | 5494449 | 2.403164247 |

| 10022-101 | GNF2 | LSM-1022 | 5311510 | 1.533458882 | |

| 10023-103 | Imatinib | Gleevec; Glivec; CGP-57148B; STI-571 | LSM-1023 | 5291 | 0.507833134 |

| 10024-101 | NVP-TAE684 | LSM-1024 | 16038120 | 0.650864909 | |

| 10025-101 | CGP60474 | MLS000911536; SMR000463552 | LSM-1025 | 644215 | 1.143196392 |

| 10026-101 | PD173074 | LSM-1026 | 1401 | 1.349794193 | |

| 10027-101 | Crizotinib | PF02341066 | LSM-1027 | 11626560 | 2.35849665 |

| 10028-102 | BMS345541 | LSM-1028 | 9813758 | 2.284241161 | |

| 10029-101 | GW-5074 | LSM-1029 | 5034 | 2.933896073 | |

| 10030-101 | KIN001-042 | LSM-1030 | 6539732 | 2.034373016 | |

| 10031-101 | KIN001-043 | LSM-1031 | 24906282 | 2.277225052 | |

| 10032-101 | Saracatinib | AZD0530 | LSM-1032 | 10302451 | 1.909534768 |

| 10033-101 | KIN001-055 | LSM-1033 | 3796 | 1.713826382 | |

| 10034-101 | AS601245 | JNK inhibitor V | LSM-1034 | 10109823 | 1.603949462 |

| 10035-101 | Sigma A6730 | KIN001-102; AKT inhibitor VIII; Akt1/2 kinase inhibitor | LSM-1035 | 10196499 | 1.236566245 |

| 10036-101 | SB 239063 | LSM-1036 | 5166 | 0.923668654 | |

| 10037-101 | AC220 | LSM-1037 | 24889392 | 0.66036709 | |

| 10038-101 | WH-4-023 | LSM-1038 | 0.705242221 | ||

| 10039-101 | WH-4-025 | LSM-1039 | 0.878242979 | ||

| 10040-101 | R406 | LSM-1040 | 11213558 | 1.290023399 | |

| 10041-101 | BI-2536 | NPK33-1-98-1 | LSM-1041 | 11364421 | 0.933762381 |

| 10042-101 | Motesanib | AMG706 | LSM-1042 | 11667893 | 0.982748388 |

| 10045-101 | A443654 | LSM-1045 | 10172943 | 0.33916124 | |

| 10046-101 | SB590885 | LSM-1046 | 53239990 | 1.088672775 | |

| 10047-101 | GDC-0941 | LSM-1047 | 17755052 | 1.260658806 | |

| 10048-101 | PD184352 | CI-1040 | LSM-1048 | 6918454 | 1.16452136 |

| 10049-101 | PLX-4720 | LSM-1049 | 24180719 | 1.176273559 | |

| 10050-101 | AZ-628 | LSM-1050 | 11676786 | 1.04927208 | |

| 10051-104 | Lapatinib | GW-572016; Tykerb | LSM-1051 | 208908 | 0.429396894 |

| 10052-101 | Rapamycin | Sirolimus | LSM-1052 | 5040 | 0.402750239 |

| 10053-101 | ZSTK474 | LSM-1053 | 11647372 | 0.41805056 | |

| 10054-101 | AS605240 | LSM-1054 | 24906273 | 0.732759892 | |

| 10055-101 | BX-912 | LSM-1055 | 11754511 | 2.605846607 | |

| 10056-101 | Selumetinib | AZD6244; Array142886 | LSM-1056 | 10127622 | 0.553955666 |

| 10057-102 | MK2206 | LSM-1057 | 24964624 | 1.504894522 | |

| 10058-101 | CG-930 | JNK930 | LSM-1058 | 57394468 | 4.007666972 |

| 10060-101 | TAK-715 | LSM-1060 | 9952773 | 1.613382403 | |

| 10061-101 | NU7441 | KU 57788 | LSM-1061 | 11327430 | 1.569151414 |

| 10062-101 | GSK1070916 | KIN001-216 | LSM-1062 | 46885626 | 2.337479347 |

| 10063-101 | OSI-027 | LSM-1063 | 56965966 | 1.942365366 | |

| 10064-101 | WYE-125132 | LSM-1064 | 25260757 | 1.462093205 | |

| 10065-101 | KIN001-220 | Genentech 10 | LSM-1065 | 44139710 | 2.178706316 |

| 10066-101 | MLN8054 | LSM-1066 | 11712649 | 2.270808355 | |

| 10067-101 | Barasertib | AZD1152-HQPA | LSM-1067 | 16007391 | 2.241656229 |

| 10068-101 | PLX4032 | RG7204; R7204; RO5185426 | LSM-1068 | 42611257 | 3.07767941 |

| 10069-101 | Enzastaurin | LY317615 | LSM-1069 | 176167 | 1.655733221 |

| 10070-101 | NPK76-II-72-1 | LSM-1070 | 46843648 | 3.842016417 | |

| 10071-101 | PD0332991 | LSM-1071 | 5330286 | 1.627198217 | |

| 10072-101 | PF562271 | KIN001-205 | LSM-1072 | 11713159 | 3.899881066 |

| 10073-101 | PHA-793887 | LSM-1073 | 46191454 | 2.17518565 | |

| 10074-101 | KU55933 | LSM-1074 | 5278396 | 1.21796861 | |

| 10075-101 | QL-X-138 | LSM-5803 | 1.752769285 | ||

| 10076-101 | QL-XI-92 | LSM-5394 | 1.035369776 | ||

| 10077-101 | QL-XII-47 | LSM-6019 | 71748056 | 0.922741288 | |

| 10078-101 | THZ-2-98-01 | LSM-1078 | 1.14616835 | ||

| 10079-101 | Torin1 | LSM-1079 | 49836027 | 0.878415444 | |

| 10080-101 | Torin2 | LSM-1080 | 51358113 | 1.055414012 | |

| 10081-101 | KIN001-244 | LSM-1081 | 49766501 | 0.81807548 | |

| 10082-101 | WZ-4-145 | LSM-1082 | 0.91286562 | ||

| 10083-101 | WZ-7043 | LSM-5749 | 0.926100059 | ||

| 10084-101 | WZ3105 | LSM-5970 | 42628507 | 0.94546971 | |

| 10085-101 | WZ4002 | LSM-1085 | 44607530 | 1.099049369 | |

| 10086-101 | XMD11-50 | LRRK2-in-1 | LSM-1086 | 46843906 | 1.018094245 |

| 10087-101 | XMD11-85h | LSM-1087 | 1.101511287 | ||

| 10088-101 | XMD13-2 | LSM-1088 | 1.361331 | ||

| 10089-101 | XMD14-99 | LSM-6297 | 1.560871453 | ||

| 10090-101 | XMD15-27 | LSM-1090 | 1.528830129 | ||

| 10091-101 | XMD16-144 | LSM-1091 | 1.299223341 | ||

| 10092-101 | JWE-035 | LSM-1092 | 57340671 | 1.125954857 | |

| 10093-101 | XMD8-85 | LSM-1093 | 46844147 | 0.701433806 | |

| 10094-101 | XMD8-92 | LSM-1094 | 46843772 | 0.474119972 | |

| 10095-101 | ZG-10 | LSM-1095 | 0.632899738 | ||

| 10096-101 | ZM-447439 | LSM-1096 | 9914412 | 0.871172197 | |

| 10097-101 | Erlotinib | OSI-774 | LSM-1097 | 176870 | 1.370711224 |

| 10098-101 | Gefitinib | ZD1839 | LSM-1098 | 123631 | 1.062687263 |

| 10099-101 | Nilotinib | AMN-107 | LSM-1099 | 644241 | 1.126974966 |

| 10100-101 | JNK-9L | KIN001-204 | LSM-1100 | 59588070 | 1.096675185 |

| 10101-101 | PD0325901 | PD-325901 | LSM-1101 | 9826528 | 1.296299084 |

| 10104-101 | RO-3306 | LSM-1104 | 71433937 | 0.613208707 | |

| 10105-101 | MPS-1-IN-1 | HG-5-125-01 | LSM-1105 | 25195352 | 1.347473378 |

| 10106-101 | XMD-12 | LSM-1106 | 54592204 | 1.051504315 | |

| 10109-101 | YM 201636 | Kin001-170 | LSM-1109 | 9956222 | 1.176291546 |

| 10110-101 | FR180204 | KIN001-230 | LSM-1110 | 11493598 | 1.004015911 |

| 10111-101 | TWS119 | LSM-1111 | 9549289 | 1.006889712 | |

| 10112-101 | PF477736 | LSM-1112 | 16750408 | 1.114963035 | |

| 10113-101 | Kin237 | Kin001-237; c-Met/Ron dual kinase inhibitor | LSM-1113 | 16757524 | 2.009251213 |

| 10114-101 | Pazopanib | GW786034 | LSM-1114 | 10113978 | 2.716024512 |

| 10115-102 | LDN-193189 | DM 3189 | LSM-1115 | 25195294 | 1.379353013 |

| 10116-101 | PF431396 | LSM-1116 | 11598628 | 1.083933499 | |

| 10117-101 | Celastrol | LSM-1117 | 5315765 | 1.352759395 | |

| 10118-101 | Amuvatinib | MP470 | LSM-1118 | 11282283 | 1.17713665 |

| 10119-101 | SU11274 | PKI-SU11274 | LSM-1119 | 53396327 | 1.204101689 |

| 10120-102 | Canertinib | CI-1033; PD-183805 | LSM-1120 | 156414 | 1.194695607 |

| 10121-101 | SB525334 | LSM-1121 | 9967941 | 0.875127226 | |

| 10122-101 | NVP-AEW541 | AEW541 | LSM-1122 | 46881851 | 0.291941727 |

| 10123-101 | SGX523 | LSM-1123 | 24779724 | 0.315938865 | |

| 10124-101 | MGCD265 | LSM-1124 | 24901704 | 0.377790303 | |

| 10125-101 | PHA-665752 | LSM-1125 | 66596670 | 0.919023711 | |

| 10126-101 | PI103 | LSM-1126 | 9884685 | 1.045250399 | |

| 10127-101 | Dovitinib | TKI_258; TKI258 | LSM-1127 | 49830557 | 1.115987595 |

| 10128-101 | GSK 690693 | LSM-1128 | 16048642 | 0.464314499 | |

| 10129-101 | PCI-32765 | LSM-1129 | 16126651 | 0.463234881 | |

| 10130-101 | Masitinib | AB1010 | LSM-1130 | 10074640 | 0.479937758 |

| 10131-101 | Tivantinib | ARQ197 | LSM-1131 | 11494412 | 0.465045725 |

| 10132-101 | BMS-387032 | SNS-032 | LSM-1132 | 3025986 | 0.478334331 |

| 10133-101 | Afatinib | BIBW-2992 | LSM-5742 | 57519523 | 0.481581186 |

| 10134-101 | GSK1904529A | LSM-1134 | 25124816 | 0.575227365 | |

| 10135-101 | OSI 906 | LSM-1135 | 11640390 | 0.609908411 | |

| 10136-101 | TPCA-1 | LSM-1136 | 9903786 | 0.786047558 | |

| 10137-101 | BMS509744 | BMS-509744 | LSM-1137 | 11467730 | 0.781029121 |

| 10138-101 | Ruxolitinib | INCB018424 | LSM-1139 | 25126798 | 0.722905845 |

| 10139-101 | AZD-1480 | LSM-1140 | 46861588 | 0.792774789 | |

| 10140-101 | CYT387 | LSM-1141 | 25062766 | 1.029063396 | |

| 10141-101 | TG 101348 | LSM-1142 | 16722836 | 1.108929975 | |

| 10142-101 | GSK-1120212 | GSK1120212; JTP-74057 | LSM-1143 | 11707110 | 1.035621271 |

| 10143-101 | BMS 777607 | LSM-1144 | 24794418 | 1.037536877 | |

| 10144-101 | Olaparib | AZD2281; KU-0059436 | LSM-1145 | 23725625 | 0.909629031 |

| 10145-102 | Veliparib | ABT-888 | LSM-1146 | 11960529 | 0.842480273 |

| 10146-101 | GSK2126458 | LSM-1147 | 52914946 | 0.619658904 | |

| 10147-101 | NVP-BKM120 | LSM-1148 | 16654980 | 0.600168165 | |

| 10148-101 | XL147 | SAR245408 | LSM-1149 | 52914932 | 0.645857739 |

| 10149-102 | Y39983 | LSM-1150 | 9810884 | 0.878862108 | |

| 10150-101 | Ponatinib | AP24534 | LSM-1151 | 24826799 | 0.911583392 |

| 10151-101 | BIBF-1120 | Vargatef | LSM-1152 | 56965894 | 0.794713743 |

| 10152-101 | MK 1775 | LSM-1153 | 24856436 | 0.589353743 | |

| 10153-101 | KIN001-266 | LSM-1154 | 44143370 | 0.769034963 | |

| 10154-101 | AT7867 | LSM-1155 | 11175137 | 0.668385776 | |

| 10155-101 | KU-60019 | LSM-1156 | 16117018 | 0.632957482 | |

| 10156-101 | JNJ38877605 | LSM-1157 | 46911863 | 0.553079045 | |

| 10157-101 | Foretinib | XL880; GSK1363089 | LSM-1158 | 42642645 | 0.763822095 |

| 10158-101 | AZD 5438 | KIN001-239 | LSM-1159 | 16747683 | 0.528159223 |

| 10159-101 | Pelitinib | EKB-569 | LSM-1160 | 216467 | 0.819518458 |

| 10160-101 | SB 216763 | LSM-1161 | 176158 | 0.950210556 | |

| 10161-101 | NVP-AUY922 | LSM-1162 | 53401173 | 0.801578531 | |

| 10162-101 | SP600125 | LSM-1163 | 8515 | 0.861808171 | |

| 10163-101 | BIX 02189 | LSM-1164 | 0.968534608 | ||

| 10164-101 | AZD8330 | ARRY-424704; ARRY-704 | LSM-1165 | 16666708 | 0.90066059 |

| 10165-101 | PF04217903 | LSM-1166 | 17754438 | 0.950305021 | |

| 10166-101 | BAY61-3606 | LSM-1167 | 10200390 | 1.22682713 | |

| 10167-101 | SB 203580 | RWJ 64809; PB 203580 | LSM-1168 | 176155 | 0.946537481 |

| 10168-101 | VX-745 | LSM-1169 | 3038525 | 0.65132132 | |

| 10169-101 | Doramapimod | BIRB 796 | LSM-1170 | 156422 | 0.782130707 |

| 10170-101 | JNJ 26854165 | LSM-1171 | 60167550 | 0.861305329 | |

| 10171-101 | TGX221 | LSM-1172 | 9907093 | 1.066374647 | |

| 10172-101 | GSK1059615 | LSM-1173 | 71317162 | 1.694786056 | |

| 10173-101 | XL765 | SAR245409 | LSM-1174 | 49867926 | 2.278712817 |

| 10174-101 | A 769662 | LSM-1175 | 54708532 | 2.181401636 | |

| 10175-101 | Sunitinib | Sutent; SU11248 | LSM-1176 | 3086686 | 2.205511276 |

| 10176-101 | Y-27632 | LSM-1177 | 5711 | 0.842124815 | |

| 10177-101 | Brivanib | BMS-540215 | LSM-1178 | 11451527 | 0.951738314 |

| 10178-101 | OSI-930 | LSM-1179 | 9868037 | 1.032584208 | |

| 10179-101 | ABT-737 | LSM-1180 | 11228183 | 1.126422454 | |

| 10180-101 | CHIR-99021 | CT99021; KIN001-157 | LSM-1181 | 9956119 | 0.796843315 |

| 10181-101 | GDC-0879 | LSM-1182 | 57519545 | 0.749396012 | |

| 10182-101 | Linifanib | ABT-869; AL-39324 | LSM-1183 | 11485656 | 0.760089426 |

| 10183-101 | BGJ398 | KIN001-271; NVP-BGJ398 | LSM-1184 | 53235510 | 1.017196562 |

| 10184-101 | ON-01910 | LSM-1185 | 1.663638422 | ||

| 10185-101 | CC-401 | LSM-1186 | 10430360 | 1.455918694 | |

| 10186-102 | Chelerythrine chloride | LSM-1187 | 2703 | 1.743156301 | |

| 10187-101 | Ki20227 | LSM-1188 | 57345770 | 1.625687467 | |

| 10188-101 | BX795 | LSM-1189 | 10077147 | 1.59013903 | |

| 10189-101 | Bosutinib | SKI-606 | LSM-1190 | 5328940 | 2.405091896 |

| 10190-101 | PIK-93 | LSM-1191 | 6852167 | 2.203008586 | |

| 10191-101 | HMN-214 | LSM-1192 | 54143018 | 2.603891467 | |

| 10192-101 | KW2449 | KW-2449 | LSM-1193 | 67089852 | 1.531038052 |

| 10193-101 | Kin236 | Tie2 kinase inhibitor | LSM-1194 | 23625762 | 2.429232222 |

| 10194-106 | Cabozantinib | Cabozantinib S-malate; XL-184; BMS-907351 | LSM-1195 | 25102847 | 2.444282396 |

| 10195-101 | KIN001-269 | LSM-1196 | 11654378 | 2.58049853 | |

| 10196-101 | KIN001-270 | LSM-1197 | 66577006 | 2.393323376 | |

| 10197-102 | KIN001-260 | Bayer IKKb inhibitor | LSM-1198 | 67135703 | 1.802186465 |

| 10198-101 | Vandetanib | ZD6474; Zactima; Caprelsa | LSM-1199 | 3081361 | 1.551488714 |

| 10199-101 | PF 573228 | LSM-1200 | 11612883 | 0.995703518 | |

| 10200-101 | NVP-BHG712 | KIN001-265 | LSM-1201 | 16747388 | 0.514497652 |

| 10201-101 | CH5424802 | LSM-1202 | 49806720 | 0.556860557 | |

| 10202-101 | D 4476 | LSM-1203 | 6419753 | 0.629024926 | |

| 10203-101 | A66 | LSM-1204 | 42636535 | 0.790263551 | |

| 10204-101 | CAL-101 | LSM-1205 | 11625818 | 0.907660675 | |

| 10205-101 | INK-128 | LSM-1206 | 45375953 | 1.139088499 | |

| 10206-101 | RAF 265 | LSM-1207 | 11656518 | 1.28101805 | |

| 10207-101 | NVP-TAE226 | CHIR-265 | LSM-1208 | 9934347 | 0.979705086 |

| 10208-101 | JNK-IN-5A | TCS JNK 5a; KIN001-188 | LSM-1209 | 766949 | 1.270556989 |

| 10209-101 | BMS-536924, KIN001-126 | LSM-1210 | 68925359 | 1.244170198 | |

| 10213-101 | KIN001-111/A770041 | LSM-1214 | 9549184 | 1.325637216 | |

| 10218-101 | SU6656 | LSM-1219 | 5309 | 1.333588108 | |

| 10220-101 | PKC412 | LSM-1221 | 16760627 | 0.855362067 | |

| 10221-101 | GSK2334470 | LSM-1222 | 46215815 | 0.837712491 | |

| 10222-101 | Dacomitinib | PF-00299804 | LSM-1223 | 57519532 | 0.924157275 |

| 10223-101 | AG1478 | Tyrphostin | LSM-1224 | 2051 | 1.065735147 |

| 10224-104 | AST1306 | LSM-1225 | 24739943 | 0.9808901 | |

| 10225-101 | Regorafenib | BAY 73-4506 | LSM-1226 | 11167602 | 1.36922362 |

| 10232-101 | BEZ235 | NVP-BEZ235 | LSM-4255 | 11977753 | 0.766095857 |

| 10233-101 | BYL719 | LSM-4256 | 56649450 | 1.576765537 | |

| 10234-101 | GDC-0980 | LSM-4257 | 66694608 | 1.446980047 | |

| 10235-101 | RAD001 | Everolimus | LSM-4258 | 53398658 | 1.794965974 |

| 10282-101 | Vorinostat | Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA); Zolinza | LSM-3828 | 5311 | 1.819556839 |

| 10285-101 | PHA-767491 | LSM-6304 | 11715767 | 1.848538985 | |

| 10286-102 | BS-181 | LSM-6305 | 49867929 | 1.136561501 | |

| 10287-101 | Dinaciclib | SCH727965 | LSM-6306 | 46926350 | 1.098502851 |

| 10288-101 | SGI-1776 | LSM-6307 | 24795070 | 1.210051596 | |

| 10289-101 | AZD4547 | LSM-6308 | 51039095 | 1.396874436 | |

| 10336-101 | Epigallocatechin gallate | EGCG | LSM-5661 | 65064 | 1.450636465 |

| 10337-102 | OTSSP167 | LSM-6340 | 71543332 | 0.00332 | |

| 10338-101 | GDC-0068 | LSM-6341 | 24788740 | 1.448246607 | |

| 10340-101 | HG-9-91-01 | LSM-6343 | 1.327184634 | ||

| 10341-101 | HG-14-8-02 | LSM-6344 | 71496458 | 1.34586865 | |

| 10342-101 | HG-14-10-04 | LSM-6345 | 56655374 | 1.297596531 | |

| 10349-106 | NVP-BGT226 | 1.214916579 | |||

CID, compound ID; HMS, Harvard Medical School; ID, identification; LINCS, Library of Integrated Network-Based Cellular Signatures; SM, small molecule.

A MELK–eIF4B Axis in Mitotic Cells.

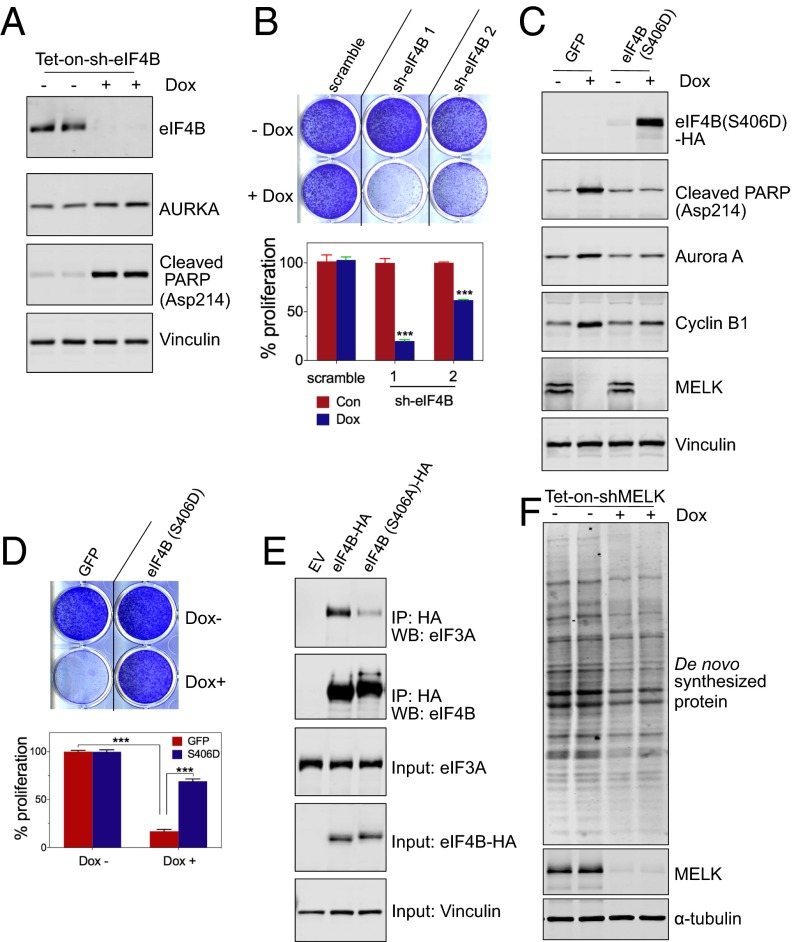

MELK was recently implicated in the proliferation and survival of basal breast cancer (BBC) rather than luminal breast cancer cells, with MELK depletion causing mitotic errors and mitosis-associated cell death (2). We therefore examined whether eIF4B phosphorylation represents a major downstream event in cell proliferation and survival. Similar to the effect of loss of MELK expression (2), doxycycline-induced EIF4B knockdown induced apoptotic cell death and the appearance of G2/M markers, such as Aurora A (Fig. 4A and Fig. S3A); furthermore, EIF4B knockdown strongly impaired the proliferation of MDA-MB-468 BBC cells (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

MELK–eIF4B signaling in cell growth and protein synthesis. (A and B) Effect of EIF4B knockdown on cell growth. MDA-MB-468 cells stably transduced with tet-on-short hairpin eIF4B (sh-eIF4B) were either left untreated or treated with Dox (100 ng/mL) for 3 d. (A) Mitotic lysates of nocodazole-arrested cells were used for immunoblotting. AURKA, Aurora A kinase. Cells transfected with control shRNA or two independent sh-eIF4B molecules were subjected to a cell proliferation assay with crystal violet staining (B, Top) and quantification of cell proliferation by absorbance of extracted stain (B, Bottom), ***P < 0.001. Note that sh-eIF4B-2 was used in A. (C and D) Phosphomimetic mutant of eIF4B (S406D) partially restores cell growth in cells with MELK depletion. MDA-MB-468 cells with tet-on-shMELK were stably transduced with a Dox-inducible construct encoding GFP or eIF4B (S406D)-HA. (C) Immunoblot shows that cells with ectopic expression of eIF4B (S406D) exhibited decreased cell death (indicated by PARP cleavage) and alleviated G2/M arrest (indicated by the protein abundance of Aurora A and cyclin B1) upon knockdown of MELK. (D) Crystal violet staining of cells (Top) and quantification of cell proliferation by absorbance of extracted stain (Bottom), ***P < 0.001. (E) Nonphosphorylatable mutant of eIF4B (S406A) shows decreased interaction with eIF3. HEK293T cells were transfected with the indicated vectors, and lysates were subjected to IP using anti-HA antibody. EV, empty vector; WB, Western blot. (F) De novo protein synthesis in mitotic cells with loss of MELK. Cells stably transduced with Dox-inducible shMELK were left untreated or treated with Dox for 3 d followed by 20-h treatment with nocodazole. Mitotic cells were harvested and assayed for incorporation of a methionine analog (31). Lysates were prepared for immunoblotting.

Fig. S3.

MELK–eIF4B signaling in cell growth and protein synthesis. (A) EIF4B knockdown induces cell death. MDA-MB-231 cells were stably transduced with tet-on-sh-eIF4B. Cells were left untreated or treated with Dox (100 ng/mL) for 4 d, and lysates were harvested for immunoblotting. Note that Aurora A kinase (AURKA) was used as a marker for the G2/M phase of the cell cycle and PARP cleavage at Asp214 was a marker of apoptotic cell death. (B and C) Ectopic expression of phosphomimetic eIF4B partially rescues MELK knockdown-induced G2/M arrest and suppression of cell growth. (B) BT-549 cells with tet-on-shMELK were stably introduced with tet-on-GFP or tet-on-eIF4B (S406D). (Left) Cells were left untreated or treated with Dox (100 ng/mL) for 4 d, and lysates were harvested for immunoblotting. (Right Top) Cells seeded in 12-well plates were treated for 7 d, fixed, and stained with crystal violet. (Right Bottom) Absorbance of extracted stain was measured for the quantification of cell growth. ***P < 0.01. (C) MDA-MB-468 cells with tet-on-shMELK were stably transduced with pWzl-GFP or -eIF4B (S406E). Cells were used for assays as in B. ***P < 0.001. (D) MDA-MB-468 cells with tet-on-sh-eIF4B were stably transduced with pWzl-GFP, -eIF4B (S406A), or -eIF4B (S406E). (Top) Cells were left untreated or treated with Dox (100 ng/mL) for 7 d, fixed, and stained with crystal violet. (Bottom) Absorbance of extracted stain was measured for quantification of cell growth. (E) MELK overexpression increases eIF4B phosphorylation and eIF4B-eIF3A interaction. HEK293T cells were transfected with HA-tagged eIF4B and either control vector or vector encoding MELK. At 36 h after transfection, cells were harvested for IP with anti-HA antibody and subjected to immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies. WB, Western blotting. (F) De novo protein synthesis in mitotic cells. Nocodazole-arrested mitotic cells (MDA-MB-468) were left untreated or treated with increasing concentrations of cycloheximide (CHX) for 30 min and then treated with puromycin (puro; 1.5 μg/mL) for 10 min. Lysates were subjected to immunoblotting using antipuromycin antibody. Lysate from cells without puromycin treatment was used as a negative Con (first lane). (Bottom) Histogram indicates the normalized signal of incorporated puromycin. (G) Cells with Dox-inducible shMELK or sh-eIF4B (tet-on-shRNA-neomycin vector) were left untreated or treated with Dox for 3 d, followed by 20 h of treatment with nocodazole. Mitotic cells were harvested and treated with puromycin for 10 min. Lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis using antipuromycin antibody.

We then proceeded to investigate whether eIF4B phosphorylation at S406 is critical for the role of MELK or eIF4B in cell proliferation and survival. For this purpose, we introduced doxycycline-inducible phosphomimetic eIF4B (S406E or S406D) together with doxycycline-inducible shRNA targeting MELK or eIF4B into cells. Expression of the phosphomimetic form of eIF4B in both MDA-MB-468 and BT549 cells partially rescued the proapoptotic and antiproliferative effects caused by the loss of MELK or eIF4B (Fig. 4 C and D and Fig. S3 B–D), suggesting that eIF4B phosphorylation at Ser406 represents a major functional downstream event of MELK.

MELK–eIF4B Signaling Controls Protein Synthesis During Mitosis.

EIF4B is known to stimulate the RNA helicase activity of eIF4A responsible for unwinding the secondary structure of the 5′-UTR of mRNA (19). In addition, eIF4B promotes protein synthesis, in part, by interacting with eIF3 to facilitate the binding of mRNA with ribosomes (20). We found that mutating serine 406 to alanine (S406A) strongly decreased the interaction between eIF4B and eIF3 (Fig. 4E) and that MELK overexpression promoted S406 phosphorylation as well as the eIF4B–eIF3 interaction (Fig. S3E). These data suggest that MELK-mediated eIF4B phosphorylation might be important for efficient formation of the translation initiation complex.

To investigate a potential role of the MELK–eIF4B pathway in mRNA translation during mitosis, we harvested nocodazole-arrested mitotic cells (MDA-MB-468) that were pretreated with doxycycline to induce depletion of MELK or eIF4B and detected the synthesis of nascent protein using a puromycin-based approach (21). We confirmed active protein synthesis in mitotic cells (Fig. S3F) and found that MELK or EIF4B knockdown strongly reduced the synthesis of nascent proteins (Fig. S3G). MELK knockdown also resulted in a more than twofold decrease in global protein synthesis, as indicated by the incorporation of a methionine analog into nascent protein (Fig. 4F). Together, these data suggest a role of MELK–eIF4B signaling in regulating protein synthesis during mitosis.

MELK-eIF4B Regulates MCL1 Protein Abundance and Cancer Cell Survival.

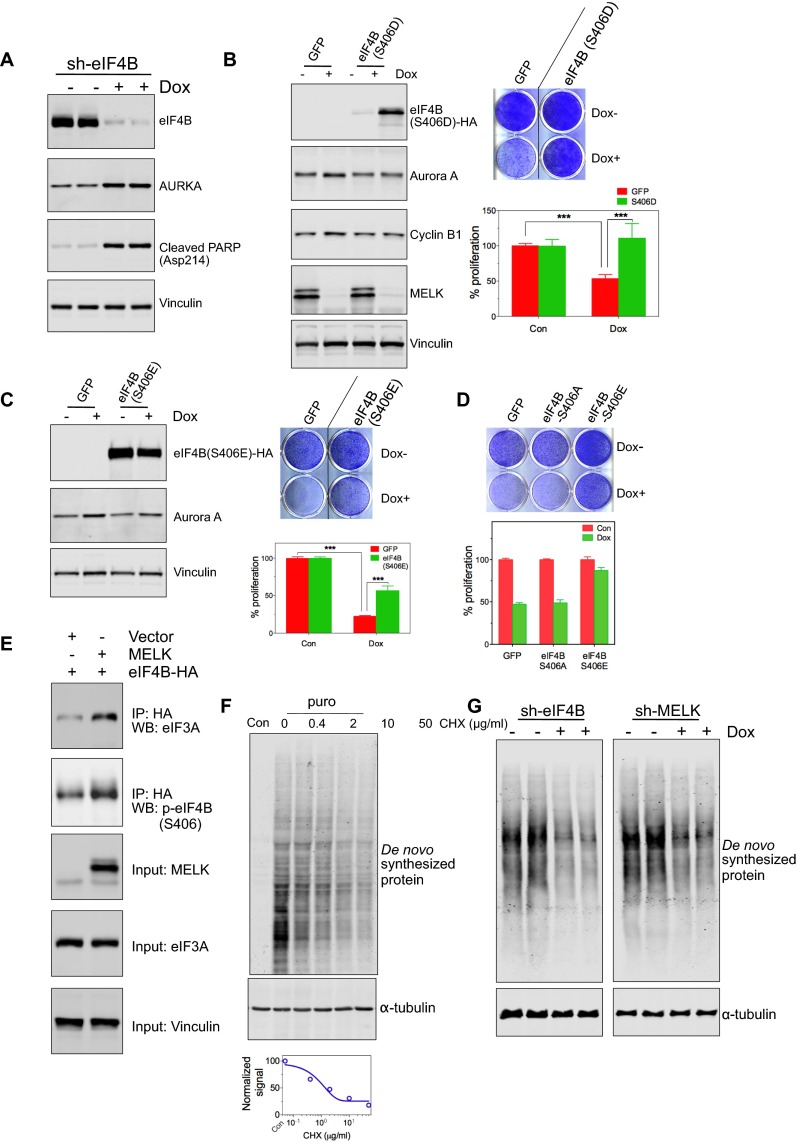

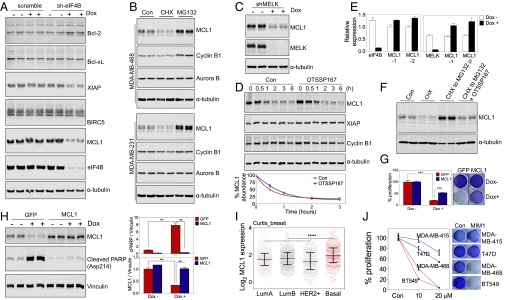

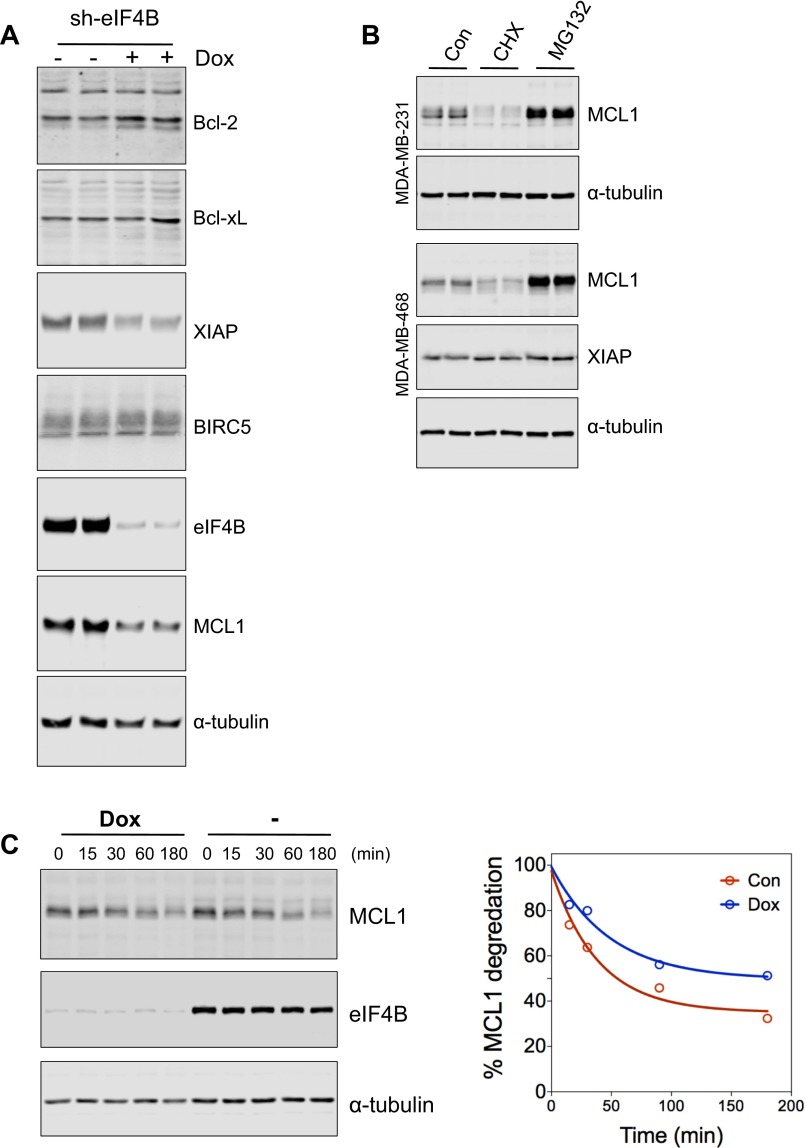

The role of MELK-eIF4B in regulating cell survival during passage through mitosis (Fig. 4 A and B and Fig. S3A) led us to hypothesize that the synthesis of certain antiapoptotic protein(s) might be highly dependent on MELK–eIF4B signaling. To identify such factor(s), we analyzed the abundance of antiapoptotic proteins in mitotic cells depleted for eIF4B and found that the protein abundance of MCL1 and XIAP, but not Bcl2, Bcl-xL, or BIRC5/survivin, was reduced upon EIF4B knockdown (Fig. 5A and Fig. S4A). This finding is consistent with the faster turnover of MCL1 compared with other BH3 family proteins described previously (3). Also consistent with previous studies (4), active protein synthesis and degradation of MCL1, but not XIAP, were observed in mitotic cells (Fig. 5B and Fig. S4B). Therefore, we focused on the role of MCL1 in mediating MELK–eIF4B signaling and regulating cell survival.

Fig. 5.

MELK–eIF4B signaling regulates the protein synthesis of MCL1 during mitosis. (A) Analysis of antiapoptotic proteins in mitotic cells with loss of eIF4B. MDA-MB-231 cells stably transduced with tet-on-sh-eIF4B were left untreated or treated with Dox for 2 d, followed by 20-h treatment with nocodazole (200 ng/mL). Mitotic cells were harvested by shake-off and analyzed by immunoblotting. Note that the protein abundance of MCL1 and XIAP, but not Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, or BIRC5, was decreased upon loss of eIF4B. (B) Synthesis and degradation of MCL1 protein in mitotic cells. Paclitaxel-arrested mitotic cells from the indicated cell lines were left untreated (Con) or were treated with cycloheximide (CHX, 50 μg/mL) or MG132 (10 μM) for 2 h. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting. (C) Loss of MELK reduces MCL1 protein abundance in mitotic cells. Cells with tet-on-shMELK were left untreated or treated with Dox for 2 d, and then treated with nocodazole for 20 h for the harvest of mitotic cells. (D) MELK inhibition does not alter the stability of MCL1. Mitotic cells were treated with CHX (100 μg/mL) or CHX combined with OTSSP167 (50 nM) for the indicated time. (Top) Lysates were prepared for immunoblotting. (Bottom) Signal of MCL1 was quantified and normalized to the signal of α-tubulin. (E) MCL1 transcription is not down-regulated upon MELK or EIF4B knockdown. Cells were treated as in C and harvested for total RNA extraction, followed by reverse transcription and quantitative PCR using primer pairs specific for MELK or eIF4B and two independent pairs of primers for MCL1. (F) MELK inhibition impairs the synthesis of MCL1. Mitotic cells were either left untreated or treated with CHX for 90 min. A sample of the CHX-treated cells was washed and incubated in the presence of MG132 (CHX to MG132) or MG132 plus OTSSP167 (50 nM) (CHX to MG132 + OTSSP167) for 90 min. Cell lysates were prepared for immunoblotting. (G) Ectopic expression of MCL1 results in partial rescue of growth inhibition in cells depleted for MELK. MDA-MB-468 cells with tet-on-sh-MELK were transduced with pWzl retroviral vector encoding GFP or MCL1. Cells were seeded in 12-well plates (20,000 cells per well), and either left untreated or treated with Dox (100 ng/mL) for 7 d. (Right) Cells were stained with crystal violet. (Left) Stain was extracted for quantification of cell growth. ***P < 0.001. (H) MCL1 overexpression alleviates cell death induced by MELK knockdown. (Left) Cells as in G were left untreated or treated with Dox (100 ng/mL) for 4 d before immunoblotting. (Right) Signals of PARP cleavage and MCL1 protein abundance were normalized to signals of vinculin. **P < 0.01. (I) Overexpression of MCL1 in BBC. Tumor samples in the Curtis et al. cohort (32) were classified into five distinct molecular subtypes (33). Note that BBC tumors have a higher expression level of MCL1 than luminal or HER2+ breast cancer. ****P < 0.0001. (J) BBC cells are sensitive to MCL1 inhibition. BBC (MDA-MB-468, BT549) and luminal breast cancer (MDA-MB-415, T47D) cells were treated with vehicle control or MCL1 inhibitor (MIM1). (Right) Cells were stained with crystal violet. (Left) Absorbance of extracted stain was measured for the quantification of cell growth.

Fig. S4.

Mitotic translation of MCL1. (A) Effect of EIF4B knockdown on the expression of antiapoptotic proteins. MDA-MB-231 cells stably transduced with tet-on-sh-eIF4B were left untreated or treated with Dox for 2 d, followed by 20 h of treatment with paclitaxel. Mitotic cells were harvested by shake-off, and cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting. Note that the protein abundance of MCL1 and XIAP, but not Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, or BIRC5, was decreased upon loss of eIF4B. (B) MCL1 protein abundance in mitotic cells is sensitive to perturbation of protein synthesis or degradation. Nocodazole-arrested mitotic cells from the indicated cell lines were left untreated (Con) or treated with CHX (50 μg/mL) or MG132 (10 μM) for 2 h. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting. (C) EIF4B knockdown does not accelerate MCL1 degradation. MDA-MB-231 cells stably transduced with tet-on-sh-eIF4B were left untreated or treated with Dox (100 ng/mL) for 2 d. Cells were treated with nocodazole for 20 h, and the resultant mitotic cells were treated with CHX (100 μg/mL) for the indicated time. (Left) Cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies. (Right) MCL1 signal was quantified and normalized to the signal of a loading control (α-tubulin).

Similar to eIF4B depletion, MELK knockdown significantly decreased the abundance of MCL1 in mitotic cells (Fig. 5C). To test whether MCL1 loss promoted by the loss of eIF4B and MELK was caused by an increase in proteolysis or a decrease in synthesis, we added cycloheximide to block mRNA translation and performed immunoblotting to measure protein stability during mitotic arrest. We found that the protein stability of MCL1 was not altered by MELK or eIF4B inhibition (Fig. 5D and Fig. S4C), indicating that loss of eIF4B and MELK affects MCL1 synthesis but not proteolysis. We next measured mRNA levels of MCL1 using two independent probes for quantitative PCR and found that mRNA expression was not reduced, or was even slightly increased, upon MELK or EIF4B knockdown (Fig. 5E). To address a direct role of MELK in regulating MCL1 synthesis, we pretreated cells with cycloheximide to deplete MCL1 protein and, after washing away the cycloheximide, treated the cells with MG132 to observe newly synthesized MCL1. MELK inhibition by OTSSP167 efficiently decreased the synthesis of MCL1 protein (Fig. 5F), suggesting a role of MELK in regulating the de novo synthesis of MCL1, presumably via regulation of eIF4B phosphorylation.

To study whether MCL1 synthesis represents a critical downstream effector of the MELK–eIF4B pathway, we introduced exogenous MCL1 into cells stably transduced with tet-on-short hairpin MELK. MCL1 overexpression in MDA-MB-468 cells partially rescued the growth inhibition and cell death resulting from MELK knockdown (Fig. 5 G and H). We previously found that MELK is selectively required by BBC, an aggressive and therapeutically recalcitrant type of breast cancer (2). Interestingly, the level of MCL1 transcript was higher in BBC than in other subtypes of breast cancer (Fig. 5I). Moreover, MCL1 inhibition using a small-molecule inhibitor, MIM1 (22), caused more prominent defects in cell proliferation in BBC cells than in luminal breast cancer cells (Fig. 5J). These observations suggest that BBC cells might be addicted to high MCL1 levels for successful passage through mitosis, which, in turn, depends on up-regulation of MCL1 synthesis during mitosis by MELK–eIF4B signaling.

Discussion

The cellular functions and regulatory mechanisms of mitotic translation are poorly understood. The Ser/Thr kinase MELK is one of the proteins that show increased abundance during mitosis. Our initial biochemical studies identified eIF4B as one of the kinase substrates of MELK, with selective phosphorylation at Ser406. A chemical library screen of more than 200 kinase inhibitors indicated that MELK is uniquely capable of phosphorylating MELK. We further demonstrated that the MELK–eIF4B signaling pathway regulates protein synthesis in mitotic cells and, in particular, synthesis of the antiapoptotic protein MCL1.

The control of protein synthesis plays a critical role in regulating cell growth, survival, and tumorigenesis (23). Aberrations in translational control frequently occur in cancer, often through activation of PI3K–MAPK–mTOR signaling (23, 24) but also through overexpression of translation initiation factors, such as eIF4E (25) and helicase protein DHX29 (26). Here, we identify the MELK–eIF4B pathway as a previously unidentified strategy used by tumor cells to regulate mitotic translation and promote survival. Given the widespread overexpression of MELK in high-grade tumors, our findings in breast cancer may be applicable to many other aggressive types of malignancy, such as high-grade serous ovarian cancer and glioblastoma.

How does eIF4B phosphorylation affect protein synthesis? Consistent with a recent study (27), we find that eIF4B phosphorylation at Ser406 is required for the interaction between eIF4B and the eIF3 translation initiation complex. Those observations suggest a model in which eIF4B phosphorylation promotes the recruitment of ribosomes to mRNA and, consequently, protein synthesis. Intriguingly, the same eIF4B phosphorylation suppresses neuronal protein synthesis because eIF4B binds to regulatory non–protein-coding brain cytoplasmic RNAs with high affinity, and is thus sequestered from initiating translation of other protein-coding transcripts (28). It will be extremely interesting to study how eIF4B phosphorylation regulates protein synthesis in different cell types.

Our work demonstrates a role of the MELK–eIF4B pathway in controlling the translation of MCL1, a short-lived antiapoptotic protein whose gene is frequently amplified in various tumor types (29). Notably, MCL1 gene amplification is observed in breast tumors treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy (30). The identified mechanism for regulation of MCL1 synthesis also implicates the MELK–eIF4B pathway as a promising therapeutic target for cancers that display MCL1 gene amplification/overexpression and depend on MCL1 for cell survival.

As the only unstable antiapoptotic BH3 family protein, MCL1 plays a major role in determining the response of cancer cells to therapeutic intervention. Protein degradation of MCL1 is induced during prolonged mitotic arrest promoted by antimicrotubule drugs, such as paclitaxel (5), and it was proposed that sensitivity to this class of drugs depends, in part, on expression levels of the E3 ligases that promote MCL1 ubiquitination (4). Here, we show that a decrease in MCL1 synthesis also accounts for the selective killing of BBC cells by MELK inhibition. It is not clear why BBC cells are more sensitive to loss of MCL1 synthesis in mitosis than other breast cancer subtypes, although because BBC cells express more MCL1, they may be more addicted to its antiapoptotic effects. Given that the antiapoptotic roles of MCL1 are targeted by multiple modes of chemotherapy, our findings suggest clinical benefits of combination regimens using MELK inhibitors to repress mitotic phosphorylation of eIF4B and consequent MCL1 synthesis.

Although we find that the translation of MCL1 mRNA in mitotic cells is regulated by the MELK–eIF4B pathway, MCL1 overexpression only partially rescued the growth inhibition resulting from the loss of MELK. It is likely that the signaling may also have an impact on the protein synthesis of other prosurvival mRNAs, especially those prosurvival mRNAs with a structured 5′-UTR that consequently have a high dependence on eIF4B (12). The translation of these mRNAs, including MCL1, may collectively mediate the MELK–eIF4B signaling and regulate the mitotic survival of cancer cells.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines were cultured under standard conditions. Floating mitotic cells were harvested through nocodazole- or paclitaxel-induced metaphase arrest. Both MCL1 and eIF4B were cloned from cDNA libraries prepared from human BCC culture. Protein extraction, immunoblotting, and quantitative RT-PCR were performed using standard methods. A detailed description of reagents and protocols used in this study can be found in SI Materials and Methods.

SI Materials and Methods

Plasmids.

Human eIF4B was cloned from the reverse transcription products of total RNA extracted from human mammary epithelial cells using the following primers (forward: ATGGCGGCCTCAGCAAAAAAG; reverse: CTATTCGGCATAATCTTCTC). The 1.8-kb PCR product was used as a template for amplification of Flag-tagged or HA-tagged eIF4B with restriction sites. The resultant plasmid constructs (pWzl-Flag-eIF4B and pTrex-eIF4B-HA) were verified by sequencing. Site-directed mutagenesis of eIF4B was performed using QuikChange XL (Stratagene), and all mutant constructs were confirmed by sequencing.

To generate pLKO-tet-on-shRNA targeting human eIF4B, synthesized oligonucleotides were annealed and ligated with digested pLKO vector. The sequences for sh-eIF4B-1 and sh-eIF4B-2 were GGACCAGGAAGGAAAGATGAA and GCGGAGAAACACCTTGATCTT, respectively.

Retroviral and Lentiviral Gene Delivery.

Retroviruses were generated by transfecting HEK293T cells with retroviral plasmids and packaging DNA. Typically, 1.6 μg of pWzl DNA, 1.2 μg of pCG-VSVG (glycoprotein G of the vesicular stomatitis virus), 1.2 μg of pCG-gap/pol, and 12 μL of lipid of Metafectene Pro (Biontex) were used. DNA and lipid were each diluted in 300 μL of PBS and mixed; after 15 min of incubation, they were added to a 6-cm dish that had been seeded with 3 million HEK293T cells 1 d previously. Viral supernatant was collected 48 and 72 h posttransfection. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.45-μm membrane and added to target cells in the presence of 8 μg/mL polybrene (Millipore). Lentiviruses were generated with a similar approach, except the cells were transfected with 2 μg of pLKO DNA, 1.5 μg of pCMV-dR8.91, and 0.5 μg of pMD2-VSVG. Cells were selected with antibiotics, starting 72 h after the initial infection. Puromycin and blasticidin were used at final concentrations of 1.5 μg/mL and 4 μg/mL respectively.

Antibodies.

Antibodies to the following proteins were used for immunoblotting or immunoprecipitation (IP): puromycin (MABE343; Millipore), MELK (2916; Epitomics), p-eIF4B (S406) [8151; Cell Signaling Technology (CST)], p-eIF4B (S422) (3591; CST), eIF4B (3592; CST), MCL1 (5453; CST), XIAP (2045; CST), p-Akt (S473) (4060; CST), p-MAPK (T202/Y204) (4370; CST), cleaved PARP (Asp214) (9541; CST), Aurora A (4718; CST), and vinculin (V9131; Sigma). Anti-HA magnetic beads were from Pierce (88836), and anti-Flag magnetic beads were from Sigma (M8823). Secondary antibodies used were Alexa Fluor 680 goat anti-rabbit IgG (A-21109; Invitrogen) and IRDye800-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Rockland).

IP.

Cells were lysed with buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 100 mM NaCl, 1% Triton, protease inhibitor mixture (Roche), and phosphatase inhibitor mixture (Pierce). Cleared lysates were incubated with anti-mouse IgG magnetic beads (New England Biolabs) for the elimination of proteins with nonspecific binding to immunoglobins and/or beads. The lysates were then incubated overnight with anti-Flag (M8823; Sigma) or anti-HA magnetic beads (88836; Pierce). The beads were washed with lysis buffer five times before SDS sample buffer was added to prepare samples for immunoblotting. For mass spectrometry assay, proteins binding to anti-Flag beads were eluted using Flag peptides (F4799; Sigma) and precipitated by trichloroacetic acid. The sample was submitted to the Taplin Biological Mass Spectrometry Facility (Harvard Medical School) for mass spectrometry analysis.

Expression and Purification of MELK.

Full-length human MELK and its kinase domain (aa 1–340) were expressed using a baculovirus system. Briefly, vectors encoding MELK [pTriEx-His-GST-tobacco etch virus (tev)-MELK] were introduced into sf9 insect cells for generation of virus. BTI-TN-5B1-4 insect cells were infected with virus to express MELK. Lysates were subjected to His-tag affinity chromatography, GST-tag affinity chromatography, removal of His- and GST-tags using TEV protease, and size exclusion chromatography.

In Vitro Kinase Assay.

Flag-tagged eIF4B or Flag-eIF4B (S406A) was transfected into HEK293T cells (4 μg of DNA for cells in a 60-mm dish). At 36 h after transfection, the cells were lysed with IP buffer [100 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, supplemented with protease/phosphatase inhibitor mixture]. Lysates were cleared by incubation with anti-mouse IgG conjugated to magnetic beads (4 °C, 30 min) and then immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag M2 magnetic beads (Sigma; 4 °C, 120 min). The beads with bound antigens were washed five times with IP buffer. During the last wash, the beads were aliquoted into 1.5-mL microcentrifuge tubes. After removal of IP buffer, the beads were washed once with 1× kinase buffer without ATP [5 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 5 mM β-glycerophosphate, 2 mM DTT, 0.1 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM MgCl2; CST], and 40 μL of 1× kinase buffer with 200 mM ATP was added to each tube, followed by 5 μL of buffer without or with 500 ng of recombinant MELK. The mixture was incubated at 30 °C for 30 min, and the reaction was terminated by the addition of 40 μL of 2× SDS sample buffer. The samples were boiled and subjected to immunoblotting. For the kinase reaction containing GST-tagged eIF4B (H00001975-P01; Abnova), 240 ng of GST-eIF4B, 1 μg of MELK (kinase domain), and 300 μM ATP were used in a total reaction volume of 50 μL.

Positional Scanning Peptide Library Screen.

The positional scanning peptide library screen was performed as described previously (11, 34) using active full-length human MELK purified from insect cells. Briefly, a set of 180 biotin-conjugated peptides with the following sequence, Y-A-X-X-X-X-X-S/T-X-X-X-X-A-G-K-K-biotin, was used, where S/T indicates an equimolar mixture of Ser and Thr, and one of the nine X positions is substituted with each of the 20 total amino acids. Thus, each amino acid surrounding the S/T can be systematically evaluated. Peptides were arrayed in 384-well plates in buffer [50 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 20 mM MgCl2, 0.02 mg/mL BSA, 0.01% Brij 35, 5 mM DTT, 0.5 mM EGTA]. Full-length recombinant MELK and ϒ-[32P]-ATP were added to wells to final concentrations of 50 μM for peptide and 100 μM and 0.025 μCi/μL for ATP. After incubation for 2 h at 30 °C, aliquots of the reactions were spotted onto a streptavidin membrane. The membrane was quenched, washed extensively, dried, and exposed to a phosphor storage screen.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Thomas Roberts for scientific discussions. We thank the Harvard Medical School (HMS) LINCS Center for providing kinase inhibitors and the HMS Taplin Biological Mass Spectrometry Facility for mass spectrometry analysis. This work was supported by the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (J.J.Z.) and by NIH Grants R01GM039565 (to T.J.M.), R01GM041890 (to L.C.C.), R01CA172461 (to J.J.Z.), 1P50CA168504 (to J.J.Z.), and R35CA210057 (to J.J.Z.).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: L.C.C. is a member of the Board of Directors of, and holds equity in Agios Pharmaceuticals, a company that is developing drugs that target cancer metabolism. L.C.C. is also a founder of and holds equity in Petra Pharmaceuticals. The data presented in this manuscript are unrelated to research at Agios Pharmaceuticals or Petra Pharmaceuticals. The phosphorylation of eIF4B and related methods of use reported in this study are covered in the following published patent application: WO 2015073509 A2.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1606862113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Badouel C, Chartrain I, Blot J, Tassan JP. Maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase is stabilized in mitosis by phosphorylation and is partially degraded upon mitotic exit. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316(13):2166–2173. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang Y, et al. MELK is an oncogenic kinase essential for mitotic progression in basal-like breast cancer cells. eLife. 2014;3:e01763. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams KW, Cooper GM. Rapid turnover of mcl-1 couples translation to cell survival and apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(9):6192–6200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610643200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wertz IE, et al. Sensitivity to antitubulin chemotherapeutics is regulated by MCL1 and FBW7. Nature. 2011;471(7336):110–114. doi: 10.1038/nature09779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shi J, Zhou Y, Huang HC, Mitchison TJ. Navitoclax (ABT-263) accelerates apoptosis during drug-induced mitotic arrest by antagonizing Bcl-xL. Cancer Res. 2011;71(13):4518–4526. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fan H, Penman S. Regulation of protein synthesis in mammalian cells. II. Inhibition of protein synthesis at the level of initiation during mitosis. J Mol Biol. 1970;50(3):655–670. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(70)90091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramírez-Valle F, Badura ML, Braunstein S, Narasimhan M, Schneider RJ. Mitotic raptor promotes mTORC1 activity, G(2)/M cell cycle progression, and internal ribosome entry site-mediated mRNA translation. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30(13):3151–3164. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00322-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanenbaum ME, Stern-Ginossar N, Weissman JS, Vale RD. Regulation of mRNA translation during mitosis. eLife. 2015;4:e07957. doi: 10.7554/eLife.07957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pyronnet S, Dostie J, Sonenberg N. Suppression of cap-dependent translation in mitosis. Genes Dev. 2001;15(16):2083–2093. doi: 10.1101/gad.889201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gwinn DM, et al. AMPK phosphorylation of raptor mediates a metabolic checkpoint. Mol Cell. 2008;30(2):214–226. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hutti JE, et al. A rapid method for determining protein kinase phosphorylation specificity. Nat Methods. 2004;1(1):27–29. doi: 10.1038/nmeth708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shahbazian D, et al. Control of cell survival and proliferation by mammalian eukaryotic initiation factor 4B. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30(6):1478–1485. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01218-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Gorp AG, et al. AGC kinases regulate phosphorylation and activation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4B. Oncogene. 2009;28(1):95–106. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung S, et al. Development of an orally-administrative MELK-targeting inhibitor that suppresses the growth of various types of human cancer. Oncotarget. 2012;3(12):1629–1640. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiederschain D, et al. Single-vector inducible lentiviral RNAi system for oncology target validation. Cell Cycle. 2009;8(3):498–504. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.3.7701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harrington EA, et al. VX-680, a potent and selective small-molecule inhibitor of the Aurora kinases, suppresses tumor growth in vivo. Nat Med. 2004;10(3):262–267. doi: 10.1038/nm1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manfredi MG, et al. Antitumor activity of MLN8054, an orally active small-molecule inhibitor of Aurora A kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(10):4106–4111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608798104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thoreen CC, et al. An ATP-competitive mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor reveals rapamycin-resistant functions of mTORC1. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(12):8023–8032. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900301200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rozen F, et al. Bidirectional RNA helicase activity of eucaryotic translation initiation factors 4A and 4F. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10(3):1134–1144. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.3.1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Méthot N, Song MS, Sonenberg N. A region rich in aspartic acid, arginine, tyrosine, and glycine (DRYG) mediates eukaryotic initiation factor 4B (eIF4B) self-association and interaction with eIF3. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16(10):5328–5334. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmidt EK, Clavarino G, Ceppi M, Pierre P. SUnSET, a nonradioactive method to monitor protein synthesis. Nat Methods. 2009;6(4):275–277. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen NA, et al. A competitive stapled peptide screen identifies a selective small molecule that overcomes MCL-1-dependent leukemia cell survival. Chem Biol. 2012;19(9):1175–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silvera D, Formenti SC, Schneider RJ. Translational control in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(4):254–266. doi: 10.1038/nrc2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mamane Y, Petroulakis E, LeBacquer O, Sonenberg N. mTOR, translation initiation and cancer. Oncogene. 2006;25(48):6416–6422. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li BD, Liu L, Dawson M, De Benedetti A. Overexpression of eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) in breast carcinoma. Cancer. 1997;79(12):2385–2390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parsyan A, et al. The helicase protein DHX29 promotes translation initiation, cell proliferation, and tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(52):22217–22222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909773106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cen B, et al. The Pim-1 protein kinase is an important regulator of MET receptor tyrosine kinase levels and signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34(13):2517–2532. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00147-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eom T, et al. Neuronal BC RNAs cooperate with eIF4B to mediate activity-dependent translational control. J Cell Biol. 2014;207(2):237–252. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201401005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beroukhim R, et al. The landscape of somatic copy-number alteration across human cancers. Nature. 2010;463(7283):899–905. doi: 10.1038/nature08822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Balko JM, et al. Molecular profiling of the residual disease of triple-negative breast cancers after neoadjuvant chemotherapy identifies actionable therapeutic targets. Cancer Discov. 2014;4(2):232–245. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dieterich DC, et al. Labeling, detection and identification of newly synthesized proteomes with bioorthogonal non-canonical amino-acid tagging. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(3):532–540. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Curtis C, et al. METABRIC Group The genomic and transcriptomic architecture of 2,000 breast tumours reveals novel subgroups. Nature. 2012;486(7403):346–352. doi: 10.1038/nature10983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parker JS, et al. Supervised risk predictor of breast cancer based on intrinsic subtypes. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(8):1160–1167. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turk BE, Hutti JE, Cantley LC. Determining protein kinase substrate specificity by parallel solution-phase assay of large numbers of peptide substrates. Nat Protoc. 2006;1(1):375–379. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]