Significance

Cilia are highly conserved organelles present in most eukaryotic cell types. The transition zone (TZ) is a ciliary subdomain that acts as a “gate” to control the composition of the cilium. The importance of the TZ is reflected in the many human diseases (termed ciliopathies) that are caused by mutations in TZ complexes. Here, we use a new proteomics technique to find new components of the African trypanosome TZ. We leverage the extraordinary tractability of this system to investigate TZ proteins, localizing them to distinct subdomains within the TZ, and demonstrating their essential roles in building cilia. We show that while orthologs of some ciliopathy complexes show long-term association with the TZ, others are highly dynamic.

Keywords: transition zone, cilium/flagellum, BBSome, MKS/B9 complex, trypanosome

Abstract

The transition zone (TZ) of eukaryotic cilia and flagella is a structural intermediate between the basal body and the axoneme that regulates ciliary traffic. Mutations in genes encoding TZ proteins (TZPs) cause human inherited diseases (ciliopathies). Here, we use the trypanosome to identify TZ components and localize them to TZ subdomains, showing that the Bardet-Biedl syndrome complex (BBSome) is more distal in the TZ than the Meckel syndrome (MKS) complex. Several of the TZPs identified here have human orthologs. Functional analysis shows essential roles for TZPs in motility, in building the axoneme central pair apparatus and in flagellum biogenesis. Analysis using RNAi and HaloTag fusion protein approaches reveals that most TZPs (including the MKS ciliopathy complex) show long-term stable association with the TZ, whereas the BBSome is dynamic. We propose that some Bardet-Biedl syndrome and MKS pleiotropy may be caused by mutations that impact TZP complex dynamics.

Cilia, or flagella (the two terms are used here interchangeably), are multifunctional organelles that were present in the last common eukaryotic ancestor (1). Defects in cilia are responsible for pleiotropic human diseases (called ciliopathies) and their function is essential for pathogenesis in protozoan parasites (2, 3).

During ciliogenesis, a microtubule organizing center called the “basal body” docks at the membrane. Basal bodies are built from nine microtubule triplets and two microtubules from each triplet extend to form a transition zone (TZ) and, ultimately, the axoneme. Thus, the TZ represents a structural junction between the basal body and the axoneme.

As expected from its strategic position between the basal body and the axoneme, the TZ acts as a “ciliary gate” that controls ciliary composition and function (4). Many ciliopathies are caused by defects in complexes that associate with the TZ, including Meckel syndrome (MKS), Joubert syndrome and Bardet-Biedl syndrome (BBS). Studies using murine kidney epithelial cells and embryos suggest that the MKS complex demarcates the ciliary membrane by forming a diffusion barrier at the base of the cilium (5–7). On the other hand, the BBS complex (BBSome) is an adapter for intraflagellar transport (IFT) complexes that cross the TZ barrier to transport sensory proteins between the ciliary membrane and the cell body (8, 9).

The TZ has distinctive structural features. At the proximal boundary of the TZ, where the basal body C tubule terminates, a “terminal plate” crosses the TZ. Studies in Tetrahymena suggest that the terminal plate contains pores for the passage of IFT “trains” that deliver axonemal components to the distal tip of flagella (10). Striated transitional fibers radiate from the distal end of the basal body triplets to join the plasma membrane (11–14), forming blades thought to create a physical barrier preventing vesicles from entering the ciliary lumen. Electron microscopy (EM) studies in Chlamydomonas suggest that the junction of the transitional fibers and the membrane provides a docking site for IFT particles (15). Y-shaped linkers (or “Y linkers”) extend from the outer microtubule doublets of the TZ to the flagellar membrane, generating a stable (i.e., detergent resistant) membrane domain (16).

The distal boundary of the TZ is defined by the start of the nexin links and dynein arms on the outer axonemal doublets (13, 17), a location somewhat distal to that of the start of the central pair of microtubules in motile cilia. The basal plate anchors at least one microtubule of the central pair (18, 19) and is derived from two electron-dense discs that cross the distal TZ (20).

Although multiple studies have addressed the composition of flagella and basal bodies in a variety of systems (3, 21–25), biochemical studies on the TZ have been limited by difficulties in obtaining sufficient material of high quality. Recent elegant work used the specific biology of Chlamydomonas to purify TZ remnants from cell walls after axoneme disassembly, identifying proteins specific to green algae as well as orthologs of candidate ciliopathy genes (26).

Trypanosoma brucei is an excellent system to study ciliary biology, having unique tractability among flagellated cells. Trypanosomes possess a basal body pair that subtends a single flagellum and whose duplication reflects that of the mammalian centriole. The trypanosome flagellum exhibits the canonical features of the TZ and the trypanosome genome encodes much of the known conserved biology required for TZ function (such as IFT, MKS, and BBS proteins) (27, 28). Therefore, insights gained from trypanosome TZ biology are likely to apply to other eukaryotic cell types.

Here, we identified protein components of the TZ and nearby structures, using an innovative proteomic approach with general applicability for the biochemical analysis of discrete cytoskeletal structures. We leverage this proteome to uncover basic information about the function and dynamics of the TZ, providing insights into how ciliopathies might cause pleiotropic diseases.

Results

IP-Based Enrichment of TZ Fraction Containing Ciliopathy Proteins.

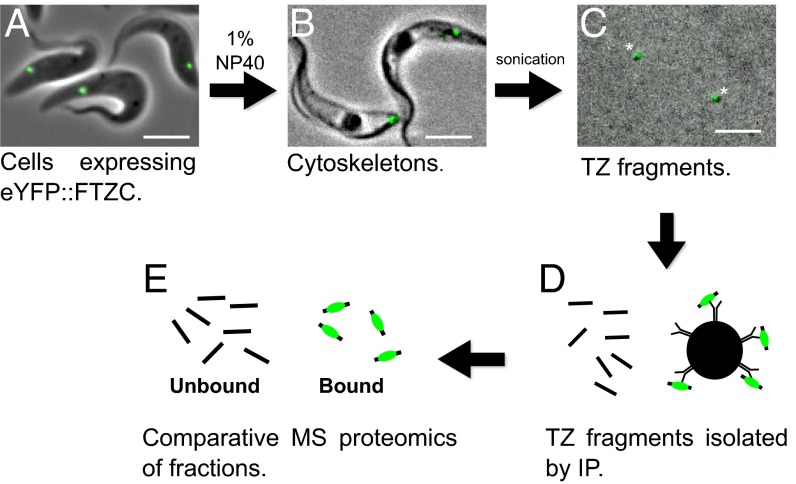

Initially we tagged one of the earliest described TZ proteins (TZPs), flagellar transition zone component (FTZC) (29), with enhanced YFP (eYFP) and confirmed the localization of the fusion protein at the TZ by microscopy (Fig. 1A). To enrich for TZs, we sonicated detergent-extracted cells (cytoskeletons) to small fragments (Fig. 1 B–D) before immunoprecipitation (IP) using anti-eYFP-conjugated Dynabeads (Fig. 1 E and F). Flagellar fragments still contained eYFP::FTZC at each stage of preparation (Fig. 1 A–D), demonstrating that TZ structures remained substantially intact.

Fig. 1.

Isolation of transition zones. (A) Live cells expressing eYFP::FTZC at the TZ (green) were (B) treated with 1% Nonidet P-40 to extract the soluble material. (C) Washed cytoskeletons were sonicated to shear the TZs from other flagellar material. Tagged FTZC remained bound to the TZ at each step of the procedure (asterisk). (D) TZ fragments were isolated by anti-eYFP IP using Dynabeads and then (E) analyzed by mass spectrometry.

Analysis by MS showed that the IP fractions were highly complex. Approximately 2,600 and 2,300 proteins were detected in the unbound (TZ depleted) and bound fractions (TZ enriched), respectively. This cohort size was expected, given the sensitivity of modern MS. Importantly, known TZPs were highly enriched in the bound fraction, including the bait protein FTZC (191-fold enriched) and orthologs of ciliopathy proteins (Fig. 2A and Datasets S1 and S2), suggesting that analysis by considering enrichment was a likely way to define novel TZ components. Therefore, the 192 proteins that were either more than fivefold enriched in, or exclusive to, the bound fraction were considered “priority” TZ candidates.

Fig. 2.

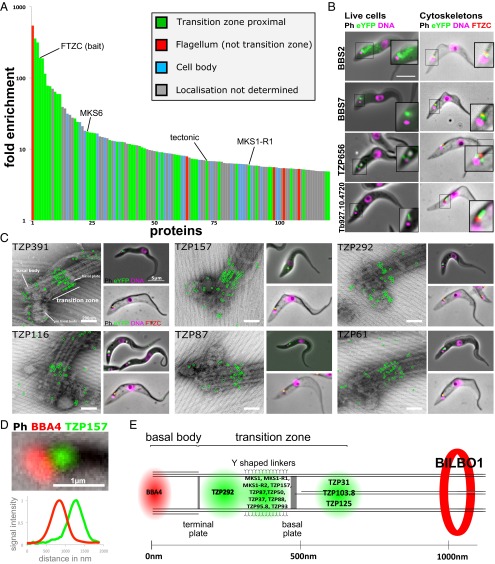

TZ subdomains defined by protein localization. (A) The localization of the proteins more than fivefold enriched in the IP-bound fraction is indicated by the color of each bar. All TZ proximal (green, includes the TZPs) and flagellum proteins (red) were verified by protein tagging. Cell body (blue) localization was judged either on protein tagging (this study) or likely localization based on known protein function. Localization not determined (gray) includes proteins where protein tagging did not give a convincing localization and proteins that were not tagged. (B) Fluorescence imaging of cell lines expressing tagged BBS2, BBS7, TZP656, and Tb927.10.4720 as live cells or as cytoskeletons stained with anti-FTZC. (C) The position of six TZPs was determined using immunogold labeling and TEM of whole cytoskeletons (Left) and fluorescence imaging of live cells (Top Right) or as cytoskeletons stained with anti-FTZC (Bottom Right). (D) Representative example of a flagellum stained with BBA4 isolated from cells expressing tagged TZP157. (E) The distance between eYFP and BBA4 signals was used to calculate protein localization within the TZ, based on the positioning of structural features as seen by EM.

TZ and Ciliary SubDomains Defined by Protein Localization Using Light and Electron Microscopy.

We selected 80 of the 192 priority TZ candidates based on their bioinformatics profiles (excluding obvious contaminants such as histones and ribosomal proteins), tagged them using a high-throughput approach, and verified the fusion protein’s localization by microscopy (30). Of these, 34 proteins (43%) localized at the TZ, 4 proteins (5%) localized to cytoskeletal structures close to the TZ, 7 proteins (8%) localized to the flagellum, and 7 proteins (8%) localized to the cell body (Fig. 2A, Dataset S2, and Fig. S1). Importantly, 10 of the 12 most enriched proteins localized at the TZ (Fig. 2A), demonstrating the effectiveness of this strategy at identifying TZPs. Twenty-eight (35%) priority TZ candidates, including trypanosome orthologs of known TZ ciliopathy proteins (e.g., tectonic and TMEM231) (28) were not localized to a discrete cellular structure, possibly because the tag disrupted proper folding of the tagged protein. Careful bioinformatics scrutiny and subsequent tagging of proteins that were less than fivefold enriched revealed another 8 TZPs (total of 42 TZPs). Of the 8 MKS complex components that are conserved in trypanosomes, only 2 were not detected, suggesting that the false negative rate was low. The BBSome components BBS2 and BBS7 were both highly enriched and localized at the TZ, but BBS2 showed significant additional staining on the flagellar pocket membrane (Fig. 2B).

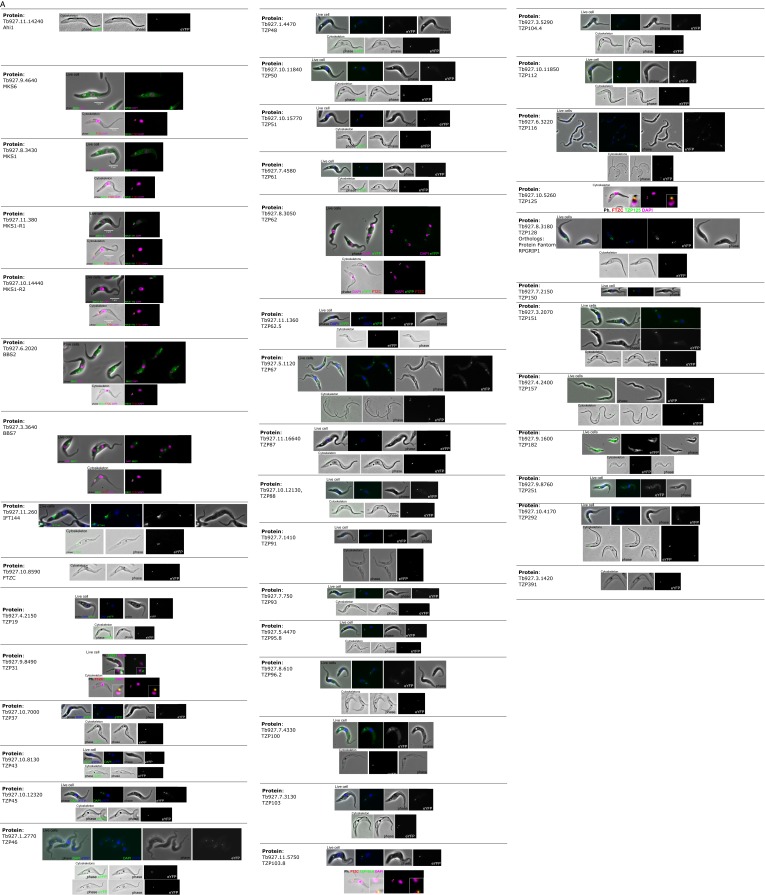

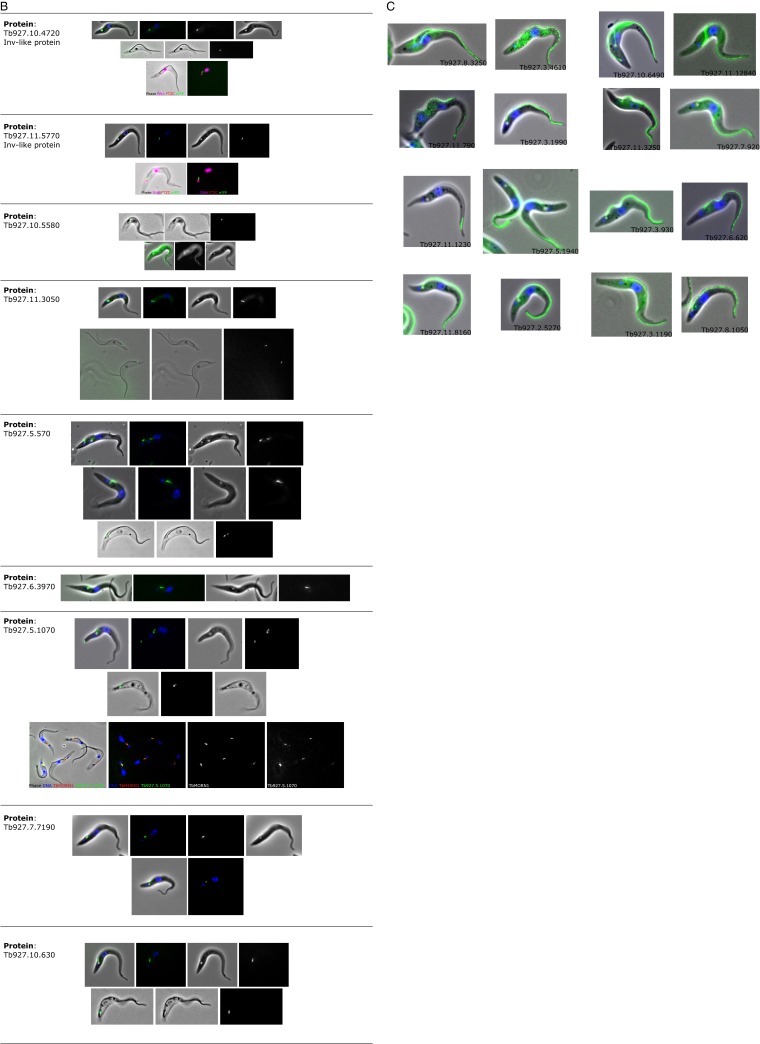

Fig. S1.

Collected light microscopy of cells expressing tagged proteins that localized to (A) the TZ, (B) proximal to the TZ, and (C) to the flagellum, but not notably enriched near the TZ.

Of the proteins that localized to cytoskeletal structures near the TZ, two proteins localized to an area distally adjacent to the TZ that, based on its position relative to the TZ, corresponds to the Inv compartment observed in other systems (31, 32) (Fig. 2B and Fig. S1). This defines a trypanosome ciliary subdomain that we call here the “Inv-like compartment.”

Transmission EM (TEM) of immunogold-labeled cytoskeletons revealed that TZPs localize to subdomains within the TZ (Fig. 2C). TZP391 and TZP157 (TZPs with molecular weights of 391 kDa and 157 kDa, respectively) formed lines along the longitudinal TZ axis, with a periodicity consistent with that of the outer doublets of the TZ. Labeling for TZP61, TZP87, and TZP116 was mostly in the distal TZ, whereas labeling for TZP292 was concentrated in the proximal TZ, with some labeling on the probasal body, which is consistent with the light microscopy data.

We then defined these subdomains for a wider range of proteins using a two-color fluorescence light microscopy method previously used to map eukaryotic kinetochores with nanoscale accuracy (33, 34). We labeled flagella isolated from cells expressing tagged TZPs with the BBA4 monoclonal antibody (35) to mark the proximal end of the basal body (Fig. 2D) and measured the distance between the BBA4 and TZ signal on many (>200) flagella. We included tagged BILBO1 (36) in this analysis to mark the point along the flagellum where it exits the flagellar (or ciliary) pocket and then overlaid the positions onto a structural map built from EM data.

The two-color fluorescence analysis showed that there are distinct protein subdomains within the TZ (Fig. 2E), confirming and extending the EM data. Three TZPs lie just distal to the basal plate, an ideal location for proteins involved in nucleation/maintenance of the central pair of microtubules. Most of the TZPs lie just proximal to the basal plate, suggesting this is the most complex part of the TZ. Consistent with the immunogold data, TZP292 lies more proximal to TZP157 and TZP87, which together lie in the same region.

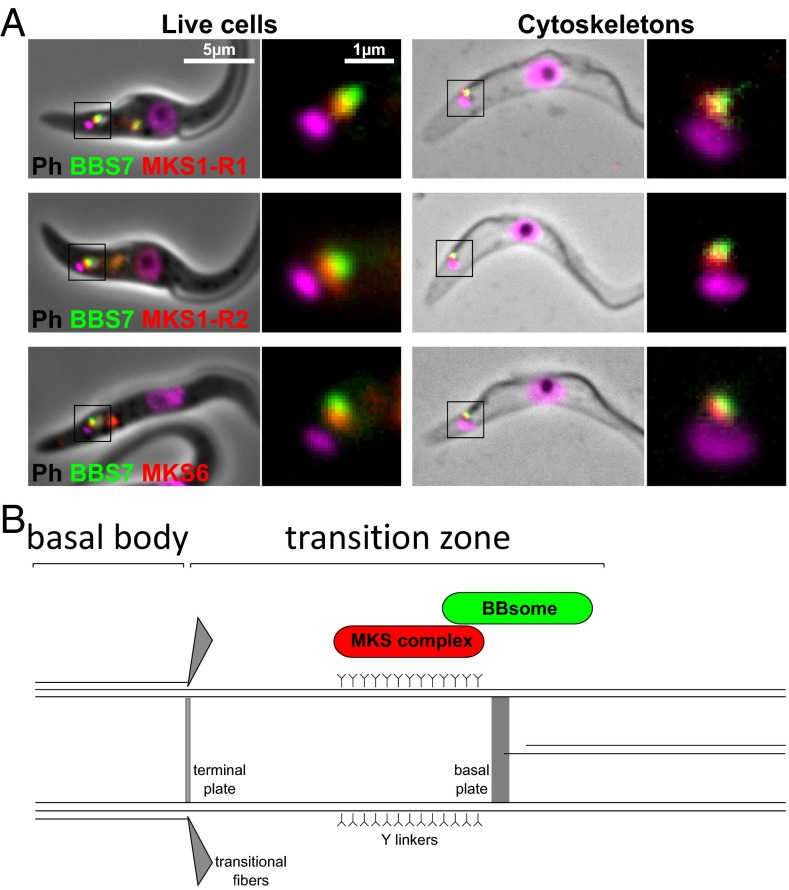

The BBSome Is More Distal Than the MKS Complex Within the TZ.

We then determined the relative localizations of the MKS complex and the BBSome by coexpressing members of each complex tagged with a different color fluorescent protein. When tagged BBS7 (BBSome, green) was coexpressed with tagged MKS6, MKS1-R1, or MKS1-R2 (MKS complex, red), some overlap of signal was observed, but the BBSome signal was consistently more distal in the TZ than the MKS complex in both live cells and cytoskeletons (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The BBSome is more distal than the MKS complex. (A) Cells coexpressing BBS7 and MKS proteins tagged with different color fluorescent proteins (green, mNeonGreen and red, tagRFPt) were imaged as live cells and cytoskeletons. (B) The positions of the MKS complex and the BBSome are marked on a structural diagram of the proximal flagellum.

An Evolutionary Analysis of the Transition Zone.

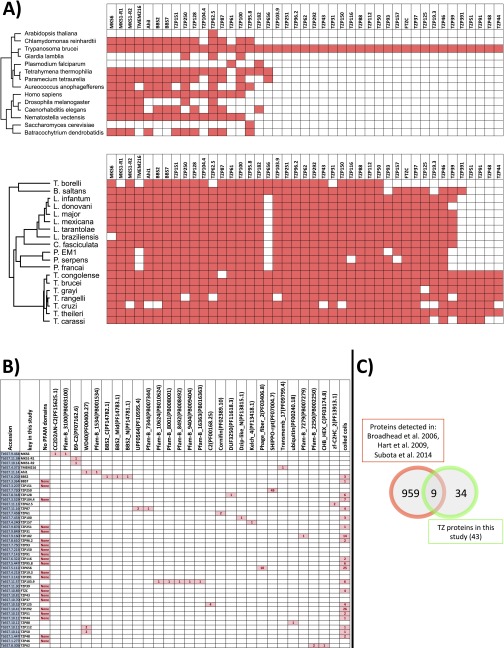

To determine the evolutionary conservation of the proteins localized in this study, we used Orthofinder (37) to cluster genes from 14 ciliated and nonciliated eukaryotic organisms into orthologous groups. Ortholog groups containing TZPs were then refined using published literature on the canonical TZPs (27, 28), protein alignments, and PFAM hidden Markov models (Dataset S2).

Using this method, 56% of the TZ-localized proteins were exclusive to kinetoplastids, with 36% and 34% having human or Chlamydomas orthologs, respectively (Dataset S2 and Fig. S2). A similar analysis on kinetoplastid genomes showed that most of the TZPs were well conserved in other kinetoplastids (such as Leishmania spp.), but four TZPs were specific to Trypanosoma spp. (Fig. S2). Five of the TZP human orthologs had no previously reported link with the TZ. A full list of the TZPs, their human orthologs, and their associated diseases is in Dataset S2.

Fig. S2.

(A) An evolutionary tree of the proteins that were localized to the TZ in this study. Presence or absence in an evolutionary lineage was initially assessed using OrthoFinder (36) and refined using published literature, alignments, and hidden Markov models. Although many of the proteins are conserved, over half are specific to the kinetoplastids. Most TZPs are conserved within the kinetoplastids, but four TZPs are unique to the Trypanosoma spp. (B) Analysis of the PFAM domains and coiled coils of the TZPs. The B9-C2 PFAM was detected in B9-R1 and B9-R2. WD40 protein–protein interaction domain was detected in 3 different proteins, but is also found in 117 other predicted proteins in the trypanosome genome, suggesting that it does not have a function specifically associated with the TZ. Coiled coils were predicted using the program COILS (www.ch.embnet.org/software/COILS_form.html), with a window size of 21 residues and a cutoff score of 0.8, and it was revealed that some TZPs showed extensive coiled-coil structure, whereas other TZPs had no coiled coils predicted. (C) Most (>80%) of the TZPs identified in this study were not detected in any of the published trypanosome flagellum proteomes.

The proteins of the trypanosome Inv-like compartment appear to be kinetoplastid specific. Tb927.10.4720 shares some sequence homology to inversin/nephronophthisis-2 in other systems, but is probably not a true ortholog because it does not encode the characteristic IQ domain (31).

Of the 21 proteins that localized evenly along the axoneme, 8 had never been detected in any flagellum proteome, 13 (including 6 dyneins) had human orthologs, of which 9 were associated with human diseases such as retinitis pigmentosa and polydactyly, whereas the remaining 5 were unique to kinetoplastids (Dataset S2).

TZPs Are Stably Associated with the TZ in the Absence of Cytoplasmic Protein.

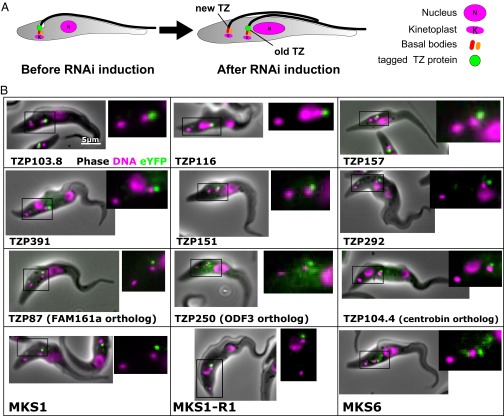

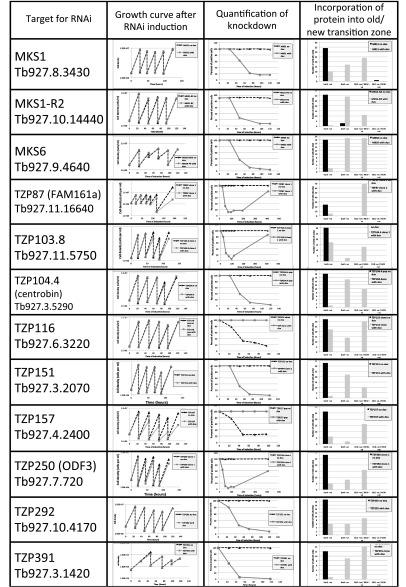

To study the function of TZPs, we ablated the expression of 12 proteins (6 with human orthologs and 6 kinetoplastid specific) by RNAi in cells expressing a tagged version of the target protein.

Trypanosomes have a single flagellum that duplicates once every cell cycle such that the new flagellum and TZ in a dividing cell are always positioned more posterior than the old (38) (Fig. 4A). For all 12 TZPs that were targeted by RNAi, >25% of dividing cells exhibited a positive old and negative new TZ after 24 h of induction (Fig. 4B and Fig. S3), showing that TZPs made before RNAi induction were stably associated with the old TZ. At later time points, in the majority of dividing cells both TZs were negative, demonstrating that RNAi was effective.

Fig. 4.

TZP is stably associated with the TZ after RNAi. (A) Cartoon showing a cell undergoing division before and after RNAi of a tagged TZP if the protein is stably incorporated into the TZ. (B) Example dividing cells from 12 cell lines expressing tagged proteins after RNAi. All 12 TZPs that were tested, including 6 with human orthologs, gave a negative new and positive old TZ at early RNAi time points.

Fig. S3.

Twelve TZPs were targeted for RNAi in cells expressing the YFP-tagged protein. RNAi cell lines were assessed for growth phenotype (Left) and the proportion of cells with effective knockdown of the protein was assessed (Center) by counting cells with at least one TZ that was positive for the tagged protein. Dividing cells with two flagella at 24 h RNAi were analyzed to determine whether the old and new TZs were positive for the ablated protein (Right). Four of 12 TZPs gave a growth phenotype, as judged by reduced growth and subsequent growth of cells without ablated TZP. Three of these—TZP157, TZP103.8, and TZP250—were associated with a severe morphological defect. Despite a clear and reproducible growth defect, TZP87, the trypanosome ortholog of FAM161a, had no obvious morphological phenotype.

However, it is possible that, in the cell lines where RNAi was associated with a defective flagellum, the new TZ was negative because it was abnormal and unable to recruit new TZPs. We therefore moved to confirm our conclusion of long TZP residency by using labeling of HaloTag fusion proteins.

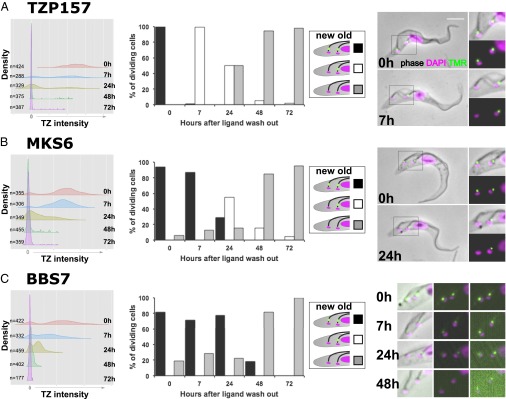

The MKS Complex and Other TZPs Are Stably Associated with the TZ but the BBSome Is Dynamic.

To study the dynamics of TZPs in minimally perturbed cells, we tagged nine TZPs (six conserved in humans and three kinetoplastid specific) with a HaloTag, a modified haloalkane dehalogenase that can be covalently labeled with a fluorophore (39). We labeled the fusion protein with a tetramethylrhodamine (TMR) fluorophore and then washed the ligand from the cells to ensure that newly made TZP was not labeled. We then observed the labeled “old” protein after 0, 7, 24, 48, and 72 h by microscopy; the 7-h time point corresponds to half of one cell cycle, meaning that the new (posterior) flagellum in dividing cells was built after protein labeling.

TZP157 (Fig. 5A) and TZP391 (Fig. S4) showed a single peak of brightly labeled TZs at 0 h. At 7 h, newly made, unlabeled TZs were observed and the proportion of negative TZs increased over time. The average intensity of the positive TZs reduced somewhat over time, revealing a low rate of protein dissociation from the TZ. Nonetheless, even at 72 h (about six cell divisions), rare cells with a bright TZ demonstrated that TZPs have long-term stable association with the TZ. All dividing cells at 7 h had a positive old and negative new TZ, showing that a cytoplasmic pool of TZP does not contribute to building new TZs over successive cell cycles, either because the pool is very small and/or very unstable.

Fig. 5.

The association of (A) TZP157, (B) MKS6, and (C) BBS7 with the TZ was assessed using fluorophore labeling of proteins tagged with a HaloTag. Cells were analyzed after the ligand was washed from the culture and the intensity of all TZs at each time point was measured (arbitrary units) and plotted on a kernel density plot (Left). Unlabeled (negative) TZs at 0 h were due to not all cells expressing correctly tagged TZP in a nonclonal population of cells. Dividing cells were scored (n > 100) according to whether the new/old TZ was labeled (Middle). Sample cytoskeletons of dividing cells are shown (Right). BBS7 (C, Right) shows examples of the posterior of the cell, processed using the same contrast for comparison of TZ intensity between different time points (Left and Middle) and with adjusted contrast to see weak TZ signals (Right).

Fig. S4.

The dynamics of TZ association was investigated by expressing the HaloTag fused to the N terminus of TZPs expressed from the endogenous locus. Tagged protein was labeled with the HaloTag ligand conjugated to a tetramethylrhodamine (TRITC) fluorophore, which was subsequently washed from the culture. Cells were analyzed by microscopy and the cell density was measured at 0, 7, 24, 48, and 72 h. The intensity of TZs was measured at each time point and plotted on a kernel density plot (Left). Dividing cells were scored (n > 100) according to whether the new/old TZ was labeled (Middle). Examples of dividing cells treated with Nonidet P-40 to extract unbound label are shown (Right). Unlabeled (negative) TZs at 0 h are due to not all cells expressing correctly tagged TZP in a nonclonal population of cells. Proteins included in this analysis are: TZP157, MKS6, BBS7 (shown in Fig. 3), MKS1, MKS1-R1, MKS1-R2, TZP87, TZP103.8, and TZP391.

As with TZP157/TZP391, all four MKS proteins and TZP87 exhibited long-term stable association with the TZ (Fig. 5B and Fig. S5). However, after 7 h the TZ intensity profile was very similar to 0 h and cells with positive old and negative new TZs were not observed, and even after 24 h (two cell cycles), dividing cells with both TZs positive were observed. Together, these data suggest that newly made TZP does not significantly contribute to building the new TZ and there is a large pool of MKS and TZP87 protein that contributes to building new TZs over several cell cycles.

Fig. S5.

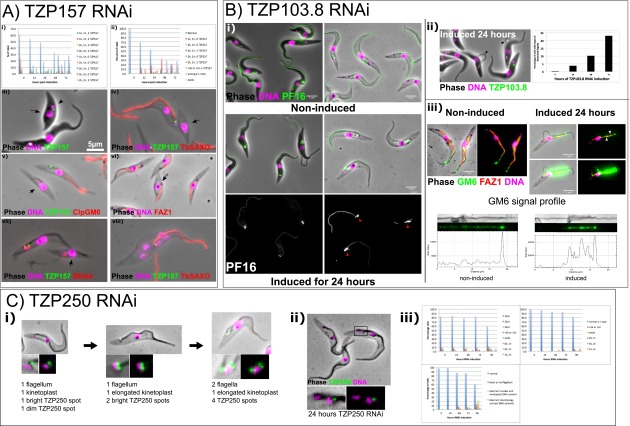

RNAi phenotypes of three TZPs. (A) TZP157 ablation causes cell cycle and morphological defects. The cell cycle position of trypanosomes can be accurately determined by the number of kinetoplasts (k) and nuclei (n) that each cell has. A cell in G1 (=1k1n) first duplicates its kinetoplast (=2k1n) and then its nuclei (=2k2n) before undergoing cytokinesis. (i) The number of kinetoplasts, nuclei and TZP157 foci were quantified over a 72 h RNAi time course. (ii) The quantification was replotted such that cells with 1k1n 1 TZP157, 1k1n 2 TZP157, 2k1n 2 TZP157, and 2k2n 2 TZP157 were grouped into a “normal” category so that the emergence of aberrant cells could be more easily visualized. (iii–vii) Cells expressing eYFP::TZP157 were induced to knockdown TZP157 by RNAi for 24 h. (iii) Live cells were stained with Hoechst. Methanol-fixed cytoskeletons were stained with antibodies against different structures: (iv) flagellum marker TbSAXO, (v) flagellum-side FAZ marker ClpGM6, (vi) cell body side FAZ marker FAZ1, and (vii) and the basal body marker BBA4. Small cells are indicated with an arrow and the flagellar pocket in the live cell is indicated with an arrow head. (viii) A representative “monster” after 48 h TZP157 RNAi with more than two kinetoplasts and more than two nuclei stained with α-TbSAXO shows the single TZP157+ flagellum, suggesting that this cell inherited the “old” flagellum in an early aberrant cytokinesis event, followed by additional subsequent aberrant cell divisions. In the small, aflagellate cells, all markers for the flagellum are absent, whereas markers for the basal bodies and the cell body side FAZ are present. (B) TZP103.8 ablation causes accumulation of cells with no central pair apparatus and aggregation of insoluble tagged PF16 in the cytoplasm near the TZ. (i) RNAi of TZP103.8 in cells expressing eYFP::PF16. At 0 h, eYFP::PF16 is incorporated into the axoneme and remains after detergent extraction (Bottom two panels). After 24 h, some cells have failed to incorporate eYFP::PF16 into the flagellum, and there is an accumulation of insoluble eYFP::PF16 near the TZ, even in cells that have eYFP::PF16 incorporated into the flagellum (Bottom four panels). Red arrowheads indicate insoluble eYFP::PF16. Left hand panels show live cells, Right hand panels show cytoskeletons. (ii) Knockdown of TZP103.8 in cells expressing eYFP::TZP103.8. There is an accumulation of cells with loops of detached flagella, rising to >22% after 72 h. Arrowheads indicate loops of detachment in representative cells. (iii) Noninduced cells and cells with TZP103.8 ablated for 24 h were stained with antibodies against the cell body side marker FAZ1, and the flagellum side marker ClpGM6. Top two micrographs of induced cells show correct contrast and Bottom two panels show contrast enhanced to see faint signals. FAZ1 appears to be normal in cells with detached flagella, whereas ClpGM6 is mostly absent from the loops that are detached from the cell body and shows strong spots of accumulation on the subdistal part of the FAZ, indicative of a FAZ assembly defect (arrowheads). The flagellum was straightened using a 40-pixel segmented line and the ClpGM6 signal along the flagellum was plotted in the noninduced Left-hand cell, and the induced cell, to show the aberrant distribution of ClpGM6 within the FAZ (Bottom). (C) TZP250 ablation causes cell cycle and morphological defects. (i) Cells expressing eYFP::TZP250 were treated with detergent to extract soluble material and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. In cells with one flagellum, one bright and one dim spot were observed, suggestive of the probasal body and the TZ or basal body. In cells where the probasal body has began to mature and the kinetoplast has elongated before division, the material is added to the probasal body and the dim spot becomes brighter. Cells with duplicating flagella exhibit four TZP250 spots, consistent with the presence of two pairs of basal bodies per TZ. (ii) In cytoskeletons with ablated TZP250, a dividing cell with one TZP250 spot on the old flagellum is seen, suggesting that the remaining TZP250 was incorporated into the flagellum during probasal body maturation in the previous cell cycle, but was sufficiently depleted such that none was available for addition to the new probasal body. (iii) Top Left and Top Right show the kinetoplast and nuclear DNA content of cells undergoing TZP250 RNAi, with the Top Right panel dividing the data into normal DNA content (i.e., that observed in a normal cell division) and aberrant DNA content. There is some accumulation of aberrant cell types, rising to 18% after 96 h of TZP250 ablation, indicative of cell cycle defects associated with defective flagellum biogenesis. The Bottom panel includes a morphological analysis and shows that there is an accumulation of cells with a short, or no, flagellum. By 96 h, 40% of cells show either a morphological defect or a DNA segregation defect.

Only BBS7 showed evidence of fast dissociation from the TZ (Fig. 5C). Positive TZs were significantly dimmer after only 7 h, dividing cells with a positive old and negative new TZ were never observed, and even after 48 h, dividing cells with both TZs positive were observed. Therefore, BBS7 segregates approximately equally between the old and new TZs at cytokinesis, indicating a high rate of BBSome flux between the TZ and the cytoplasm or, less likely, that BBS7 is in a TZ structure that segregates at cell division.

TZPs Have Essential Roles in Flagellum Biogenesis and Motility.

RNAi knockdown caused a growth defect in 4 of the 12 TZPs tested (Fig. S3), and 3 of these were associated with severe morphological defects.

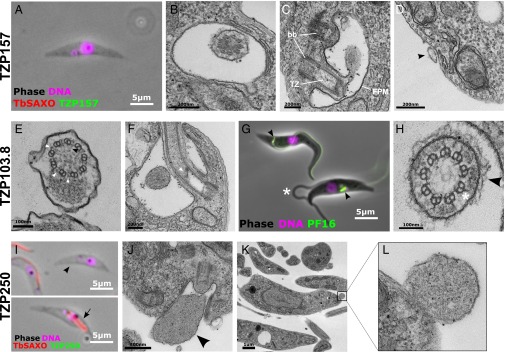

Knockdown of TZP157 caused rapid lethality and early accumulation of cells with no axoneme (Fig. 6A and Fig. S5) and late accumulation of multinucleate cells with multiple basal bodies and a single flagellum positive for the target protein (Fig. S5). TZ cross-sections revealed no obvious defects (Fig. 6B). Instead, an axonemeless membrane sleeve extended alongside the cell body from TZ stubs (Fig. 6 C and D), similar to that observed in anterograde IFT mutants (40, 41).

Fig. 6.

TZPs have essential roles in building the flagellum and its substructures. (A–D) Cells after 24 h of TZP157 RNAi induction. (A) A cytoskeleton with no axoneme is negative for TbSAXO. (B) Cross-section TEM of the TZ. (C) Thin-section EM showing the stub of TZ inside the flagellar pocket (FP). Basal body (bb), transition zone (TZ) and flagellar pocket membrane (FPM) are clearly visible. (D) The axonemeless flagellar membrane sleeve (arrowhead) is attached to the cell body of the trypanosome distal to its exit from the flagellar pocket. (E–H) Cells after 72 h of TZP103.8 RNAi induction. (E) Thin-section EM cross-section of the flagella axoneme with the central pair of microtubules missing, but intact dynein arms (white arrowheads) and radial spokes (black arrowhead). (F) A longitudinal TZ section shows a reduced basal plate (arrowhead). (G) Live cells expressing eYFP::PF16 after 48 h of TZP103.8 exhibit an accumulation of tagged PF16 in the cytoplasm near the TZ (arrowheads), defective incorporation of PF16 into the flagellum, and loops of flagellum detachment from the cell body (asterisk). (H) TZ cross-section showing an intact collarette (arrowhead) and Y linkers (asterisk). (I–L) Cells after 72 h of TZP250 RNAi induction. (I) Staining with anti-TbSAXO reveals cytoskeletons with either no flagellum (arrowhead) or a shortened flagellum (arrow). (J) Longitudinal thin-section EM showing a TZ stub linked to a glob of nonaxoneme material (arrowhead) by the flagellar membrane. (K and L) The axonemeless flagellum remnant attached to the cell body distal to flagellum exit from the flagellar pocket.

Knockdown of TZP103.8 was lethal, causing paralysis (Movie S1), absence of the axonemal central pair apparatus (Fig. 6E), and a reduced basal plate (Fig. 6F). The central pair projection protein, PF16, was not incorporated into the axoneme and was instead visible as insoluble aggregates in the cytoplasm near the TZ (Fig. 6G and Fig. S5). However, in contrast to a previous study that showed outer dynein arms were often missing in cells depleted of PF16 (42), the outer doublets retained the full complement of outer dynein arms (Fig. 6E). Moreover, after 72 h, RNAi axonemes missing the central pair were >20-fold more prevalent in TZP103.8-depleted cells [82% (n = 22), this study] than in PF16-depleted cells (42), suggesting that the missing central pair was the primary effect of TZP103.8 depletion, with the absence of axonemal PF16 being a consequence of this. The other structural features of the axoneme (e.g., inner dynein arms and radial spokes) and the TZ (e.g., Y linkers and collarette) appeared unaffected (Fig. 6 E and H). Similar to PF16 knockdown studies (42), loops of flagellum detachment from the cell body were observed, as were defects in the flagellum-cell body attachment apparatus (Fig. 6G and Fig. S5). The RNAi phenotype and the location of TZP103.8 just distal to the basal plate (Fig. 2E) suggest a role in nucleating/stabilizing the central pair apparatus.

Knockdown of TZP250 caused a subtle growth defect (Fig. S3), an accumulation of cells with a short, or absent, flagellar axoneme (Fig. 6I), and cells with an axonemeless membrane sleeve filled with amorphous material extending from TZ stubs (Fig. 6 J–L), with a later accumulation of multinucleate cells (Fig. S5). Microscopy of ablated cells showed loss of the targeted protein from first the probasal body and then the matured TZ (Fig. S5). The phenotype was not very penetrant, with 60% of cells exhibiting no discernible phenotype after 96 h of RNAi induction, suggesting that TZP250 levels remained above a functional threshold in most cells.

Discussion

A method whereby specific subregions of a large, complex cytoskeletal structure could be isolated by IP is likely to represent a powerful tool for proteomics analysis. We developed such a method for the TZ using the trypanosome system because it combines well-established flagellum structure and ontogeny with superb molecular tools. A powerful feature of our strategy is that it also enriches for structures near the bait. Hence, in addition to identifying 42 TZPs, we found two components of the Inv-like compartment, providing clues that such a compartment exists in the Excavata.

Over one-third of the TZPs are highly conserved across eukaryotes (Fig. S2). Nevertheless, our data indicate a considerable level of specialization in the trypanosome TZ, with over half of the TZPs being kinetoplastid specific. Of the 12 TZPs conserved in Chlamydomonas, half had orthologs detected in the Chlamydomonas TZ proteome (Ahi1, MKS6, MKS1-R1, BBS7, FAM161a, and DZIP) (26), leaving 6 that were not (MKS1-R2, BBS2, ODF3, FAM161a, TZP62, and TZP95.8).

The use of detergent during TZ enrichment may cause loss of some types of protein, possibly explaining the absence of the ESCRT proteins that were localized to the Chlamydomonas TZ (26). However, the presence of many TZPs with predicted membrane-association domains (C2 domains, transmembrane domains, and signal peptides) (Fig. S2) demonstrates that membrane proteins bound to the higher order structure of the TZ were not excluded.

The majority of the TZPs, including those of the MKS complex, localized to the distal half of the TZ, in the same region as that expected for the Y linkers. This is consistent with the hypothesis that the MKS complex associates with the Y linkers (4, 43) and is in agreement with the absence of Y linkers in worm NPHP/MKS mutants (7, 44), and with the lack of both Y linkers and MKS complex genes in five major clades of higher plants (28).

We show that, whereas some TZPs are essential for building new flagella, others are required for building specific axoneme substructures, such as the central pair apparatus. Nine of 12 TZPs we analyzed by RNAi did not give an obvious phenotype after RNAi, suggesting a high degree of redundancy within the TZ. Of those that gave a severe phenotype, only TZP250 is conserved in humans. TZP250 is an ortholog of human ODF3, a component of the outer dense fibers of sperm flagella (45, 46) that is also expressed in other tissues (45). Although human ODF3 has not been functionally analyzed, aberrant expression of splice variants is associated with prostate cancer (47) and a genome-wide association study links it to uterine fibroids (48). Therefore, ODF3-linked diseases may in fact be ciliopathies.

To date, the only assessment of dynamic assembly into the TZ has been performed on CEP290 and components of the MKS complex. CEP290, a Y-linker protein not found in trypanosomes (28), demonstrated a high rate of transfer between the TZs in mating Chlamydomonas gametes (16). In contrast, MKS proteins showed little fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) after 30 min (49), suggesting that little cytosolic TZP is added to mature TZs over very short time courses.

We used two methods to address the dynamics of TZP association with the TZ. We first used RNAi to show that components of the MKS complex, trypanosome orthologs of human FAM161a, ODF3 and centrobin, and trypanosomatid-specific proteins were stably associated with the TZ in the absence of a cytoplasmic pool.

We then addressed the dynamics of TZ association in a cell line where gene expression was not perturbed by labeling constitutively expressed HaloTag::TZP fusion proteins. We showed that TZPs, including four components of the MKS complex, show long-term stable association with the TZ and that newly made MKS proteins do not significantly contribute to building the new TZ. Together, our data suggest a model whereby the MKS proteins assemble into a complex (or are otherwise processed) before being built into the TZ; once incorporated, they remain in place with little or no exchange for newly built complexes.

In contrast to the other proteins in this study, we showed that, although BBS7 also had low turnover in the cell, cellular BBS7 was shared approximately equally between the old and new TZs at cytokinesis, suggesting exchange between the TZs via the cytoplasm. This finding suggests that the BBSome was observed to be distally adjacent to the MKS complex (Fig. 3) because it lingers there to facilitate its transfer between the IFT machinery specialized for crossing the TZ and that for transporting cargo to and from the ciliary tip. Kinesin II was recently shown to be specialized for crossing the TZ in Caenorhabditis elegans phasmid cilia, with gradual handover of cargo to OSM3 occurring distal to the TZ (50). The BBSome was only observed to significantly overlap with the MKS complex in a minority (<5%) of cells, presumably because it crosses the TZ too infrequently or quickly to be easily observed. The BBSome was recently localized to the flagellar pocket of the bloodstream form of trypanosomes, but the presence of the BBSome at the TZ was not tested by examining cytoskeletons (51). The fact that we do not observe BBSome signal as moving IFT-associated punctae in live cells may reflect technical limitations and the low abundance of the BBSome inside the trypanosome flagellum.

Understanding the dynamics of TZ complexes may give insights into how TZ mutations cause disease. For example, mutations that reduce the stable incorporation of the MKS complex into the TZ may be more damaging in tissues with high cellular residency and little turnover, such as the retina, than in tissues with fast turnover, such as epithelial cells. Similarly, mutations that reduce the dynamic association of the BBSome with the TZ would especially impact tissues requiring fast turnover of BBSome cargo, such as the olfactory epithelium. This may contribute to the extraordinary tissue pleiotropy of TZ ciliopathies.

Materials and Methods

Trypanosomes.

SmOxP927 P9 trypanosomes (52) were cultured in SDM79 (53) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FCS at 28 °C. Transgenic cell lines were generated as described (30). RNAi plasmids were made using primers designed by RNAi-it (54) and cloned into the pQuadra stem loop vector (55). All tagged cell lines were generated using the pPOT system (30).

TZ Enrichment By IP.

To prepare the input material for IP, 5 × 109 trypanosomes (procyclic form) were washed twice in 20 mL of PBS and resuspended in 30 mL of 1% Nonidet P-40 in PEME (100 mM Pipes pH 6.9, 1 mM MgSO4, 2 mM EGTA, 0.1 mM EDTA) with protease inhibitors (PIs) (50 μM leupeptin, Sigma L2884; 7.5 μM pepstatin A, Sigma P5318; 0.5 μM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, Roche 10837091001; and 5 μM E-64d, Biomol/ENZO PI-107) for 3 min, pelleted, and resuspended in 10 mL PEME with 200 mM NaCl with PI. This material was then sonicated for 3 × 10 s using a probe sonicator (MSE Sanyo Soniprep 150) with a 10-μm amplitude, incubated for 45 min on ice, pelleted, washed in 1% Nonidet P-40 in PBS with PI, pelleted, and resuspended in 1.3 mL 0.5% Nonidet P-40 in PBS with PI and then sonicated for 3 min in 10-s pulses on ice. To perform the IP, 100 μL of Dynabeads cross-linked to α-YFP (Roche 11814460001) using dimethyl pimelimidate (as described in ref. 56) were incubated with the sonicated “input” material for 30 min rotating at room temperature; after removal of the beads, the depleted “unbound” fraction was retained for analysis. The beads were then washed three times in 1 mL buffer H0.15 (25 mM Hepes, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA-KOH, 15% glycerol 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 150 mM KCl) with PI and rinsed four times in 1 mL preelution buffer (50 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 8.3, 75 mM KCl, and 1 mM EGTA). “Bound” material was dissociated from the beads by incubating them in 60 μL of elution buffer (0.3% SDS, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris pH 8.3) for 20 min, with subsequent removal of the Dynabeads using a magnet. Unbound (depleted) and bound (enriched) fractions were fractionated by SDS/PAGE, cut into three slices (excluding the strong 50-kDa tubulin band) and analyzed using a Thermo QExactive Orbitrap LC/MS/MS after trypsin digest. Enrichment of protein in the bound fraction was calculated using their percentage composition based on their spectral index normalized quantification (SINQ) scores (57).

Light Microscopy.

Live cells and cytoskeletons were prepared for microscopy as described (30). Concentrations of primary antibodies: BBA4 (58): 1/50; α-PFR2 (L8C4) (59): 1/50; α-TbSAXO (Mab25) (60): 1:20; TFP1: 1/50; α-TbMORN1 (61): 1/3,000; α-FTZC (29): 1/2000; and α-TbBILBO1 (36): 1/10. Images were acquired using a Leica wide-field fluorescence microscope and an sCMOS camera (Andor) and analyzed using ImageJ. DNA was visualized using 1 ng⋅mL−1 Hoechst (live cells) or 1 μg⋅mL−1 DAPI (cytoskeletons).

HaloTag Labeling.

Cells constitutively expressing HaloTag::TZP from the endogenous locus were maintained in exponential growth for several days and then labeled for ∼18 h using 1:1,000 “TMR-direct” (Promega) in SDM79 supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FCS, washed three times in fresh medium and resuspended at 5 × 106 cells⋅mL−1. Samples were taken for analysis at 0, 7, 24, 48, and 72 h after wash out of the ligand. TZ intensity was quantified by measuring the signal at each TZ and subtracting the background signal measured using a 15-pixel offset. To analyze dividing cells, the TZs from cytoskeletons with two kinetoplasts were scored as positive or negative based on whether there was detectable signal.

Two-Color TZ Mapping.

Flagella for two-color mapping were prepared by resuspending cytoskeletons in 65 mM CaCl2, 30 mM Pipes at pH 6.9, pelleting and resuspending in 40 mM Pipes, 5 mM MgSO4, 1 mM CaCl, 100 μg⋅mL−1 DNase, 100 μg⋅mL−1 RNase, incubated for 5 min, pelleted, and resuspended in PBS. Flagella were settled onto glass slides and fixed in methanol before staining with BBA4 and image acquisition. The distance between the BBA4 signal and the tagged TZP was measured (using an ImageJ macro produced in house) by aligning the red and green signals in the x axis, calculating Gaussian distribution for each, and then calculating the distance between the peaks of each histogram. The average of >200 measurements was used to calculate the distance of the TZP along the flagellum.

EM.

Thin-section EM was performed as described (62). Immunogold labeling of whole-mount cytoskeletons was performed by settling washed cells onto charged, formvar-coated grids, treating with 1% Nonidet P-40 in PBS for 5 min, block (1% BSA in PBS) for 20 min, staining with α-GFP (Invitrogen A11122; 1/500) in block for 45 min, washing three times in PBS, staining with 10 nm gold particle conjugated secondary antibody (Sigma G7402; 1/50) in block for 45 min, washing two times in PBS, followed by fixation for 10 min in 2.5% glutaraldehyde. Samples were then washed twice in PEME, stained for 1 s in 1% aurothioglucose, dried on filter paper, and imaged by TEM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Bungo Akiyoshi for advice on the IP; Frederick Bringaud, Melanie Bonhivers, and Brooke Morriswood for antibodies; Mike Fiebig for help with the evolutionary analysis and R scripts; Johanna Höög for prepublication access to EM data; Steve Kelly for prepublication access to OrthoFinder; Jack Sunter for helpful discussions; and Richard Wheeler for help with TZ cartography analysis. S.D. was funded by a Sir Henry Wellcome Fellowship (092201/Z/10/Z). Work in the K.G. laboratory is funded by the Wellcome Trust (WT066839MA and 104627/Z/14/Z).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1604258113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Wickstead B, Gull K. The evolution of the cytoskeleton. J Cell Biol. 2011;194(4):513–525. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201102065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alsford S, et al. High-throughput phenotyping using parallel sequencing of RNA interference targets in the African trypanosome. Genome Res. 2011;21(6):915–924. doi: 10.1101/gr.115089.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Broadhead R, et al. Flagellar motility is required for the viability of the bloodstream trypanosome. Nature. 2006;440(7081):224–227. doi: 10.1038/nature04541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reiter JF, Blacque OE, Leroux MR. The base of the cilium: Roles for transition fibres and the transition zone in ciliary formation, maintenance and compartmentalization. EMBO Rep. 2012;13(7):608–618. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chih B, et al. A ciliopathy complex at the transition zone protects the cilia as a privileged membrane domain. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;14(1):61–72. doi: 10.1038/ncb2410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcia-Gonzalo FR, et al. A transition zone complex regulates mammalian ciliogenesis and ciliary membrane composition. Nat Genet. 2011;43(8):776–784. doi: 10.1038/ng.891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams CL, et al. MKS and NPHP modules cooperate to establish basal body/transition zone membrane associations and ciliary gate function during ciliogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2011;192(6):1023–1041. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201012116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lechtreck K-F, et al. The Chlamydomonas reinhardtii BBSome is an IFT cargo required for export of specific signaling proteins from flagella. J Cell Biol. 2009;187(7):1117–1132. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200909183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nachury MV, et al. A core complex of BBS proteins cooperates with the GTPase Rab8 to promote ciliary membrane biogenesis. Cell. 2007;129(6):1201–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ounjai P, et al. Architectural insights into a ciliary partition. Curr Biol. 2013;23(4):339–344. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Toole ET, Giddings TH, McIntosh JR, Dutcher SK. Three-dimensional organization of basal bodies from wild-type and delta-tubulin deletion strains of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14(7):2999–3012. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-11-0755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibbons IR, Grimstone AV. On flagellar structure in certain flagellates. J Biophys Biochem Cytol. 1960;7:697–716. doi: 10.1083/jcb.7.4.697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ringo DL. Flagellar motion and fine structure of the flagellar apparatus in Chlamydomonas. J Cell Biol. 1967;33(3):543–571. doi: 10.1083/jcb.33.3.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson RG. The three-dimensional structure of the basal body from the rhesus monkey oviduct. J Cell Biol. 1972;54(2):246–265. doi: 10.1083/jcb.54.2.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deane JA, Cole DG, Seeley ES, Diener DR, Rosenbaum JL. Localization of intraflagellar transport protein IFT52 identifies basal body transitional fibers as the docking site for IFT particles. Curr Biol. 2001;11(20):1586–1590. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00484-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Craige B, et al. CEP290 tethers flagellar transition zone microtubules to the membrane and regulates flagellar protein content. J Cell Biol. 2010;190(5):927–940. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201006105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gibbons IR. The relationship between the fine structure and direction of beat in gill cilia of a lamellibranch mollusc. J Biophys Biochem Cytol. 1961;11:179–205. doi: 10.1083/jcb.11.1.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dute R, Kung C. Ultrastructure of the proximal region of somatic cilia in Paramecium tetraurelia. J Cell Biol. 1978;78(2):451–464. doi: 10.1083/jcb.78.2.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tucker JB. Development and deployment of cilia, basal bodies, and other microtubular organelles in the cortex of the ciliate Nassula. J Cell Sci. 1971;9(3):539–567. doi: 10.1242/jcs.9.3.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Höög JL, et al. Modes of flagellar assembly in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and Trypanosoma brucei. eLife. 2014;3:e01479. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hart SR, et al. Analysis of the trypanosome flagellar proteome using a combined electron transfer/collisionally activated dissociation strategy. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2009;20(2):167–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ishikawa H, Thompson J, Yates JR, 3rd, Marshall WF. Proteomic analysis of mammalian primary cilia. Curr Biol. 2012;22(5):414–419. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kilburn CL, et al. New Tetrahymena basal body protein components identify basal body domain structure. J Cell Biol. 2007;178(6):905–912. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200703109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pazour GJ, Agrin N, Leszyk J, Witman GB. Proteomic analysis of a eukaryotic cilium. J Cell Biol. 2005;170(1):103–113. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200504008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Subota I, et al. Proteomic analysis of intact flagella of procyclic Trypanosoma brucei cells identifies novel flagellar proteins with unique sub-localization and dynamics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014;13(7):1769–1786. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.033357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diener DR, Lupetti P, Rosenbaum JL. Proteomic analysis of isolated ciliary transition zones reveals the presence of ESCRT proteins. Curr Biol. 2015;25(3):379–384. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.11.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hodges ME, Scheumann N, Wickstead B, Langdale JA, Gull K. Reconstructing the evolutionary history of the centriole from protein components. J Cell Sci. 2010;123(Pt 9):1407–1413. doi: 10.1242/jcs.064873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barker AR, Renzaglia KS, Fry K, Dawe HR. Bioinformatic analysis of ciliary transition zone proteins reveals insights into the evolution of ciliopathy networks. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:531. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bringaud F, et al. Characterization and disruption of a new Trypanosoma brucei repetitive flagellum protein, using double-stranded RNA inhibition. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2000;111(2):283–297. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(00)00319-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dean S, et al. A toolkit enabling efficient, scalable and reproducible gene tagging in trypanosomatids. Open Biol. 2015;5(1):140197. doi: 10.1098/rsob.140197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shiba D, et al. Localization of Inv in a distinctive intraciliary compartment requires the C-terminal ninein-homolog-containing region. J Cell Sci. 2009;122(Pt 1):44–54. doi: 10.1242/jcs.037408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Warburton-Pitt SRF, et al. Ciliogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans requires genetic interactions between ciliary middle segment localized NPHP-2 (inversin) and transition zone-associated proteins. J Cell Sci. 2012;125(Pt 11):2592–2603. doi: 10.1242/jcs.095539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joglekar AP, Bloom K, Salmon ED. In vivo protein architecture of the eukaryotic kinetochore with nanometer scale accuracy. Curr Biol. 2009;19(8):694–699. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.02.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wan X, et al. Protein architecture of the human kinetochore microtubule attachment site. Cell. 2009;137(4):672–684. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Woods A, et al. Definition of individual components within the cytoskeleton of Trypanosoma brucei by a library of monoclonal antibodies. J Cell Sci. 1989;93(Pt 3):491–500. doi: 10.1242/jcs.93.3.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bonhivers M, Nowacki S, Landrein N, Robinson DR. Biogenesis of the trypanosome endo-exocytotic organelle is cytoskeleton mediated. PLoS Biol. 2008;6(5):e105. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Emms DM, Kelly S. OrthoFinder: Solving fundamental biases in whole genome comparisons dramatically improves orthogroup inference accuracy. Genome Biol. 2015;16(1):157. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0721-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robinson DR, Sherwin T, Ploubidou A, Byard EH, Gull K. Microtubule polarity and dynamics in the control of organelle positioning, segregation, and cytokinesis in the trypanosome cell cycle. J Cell Biol. 1995;128(6):1163–1172. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.6.1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Los GV, et al. HaloTag: A novel protein labeling technology for cell imaging and protein analysis. ACS Chem Biol. 2008;3(6):373–382. doi: 10.1021/cb800025k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Absalon S, et al. Intraflagellar transport and functional analysis of genes required for flagellum formation in trypanosomes. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19(3):929–944. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-08-0749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davidge JA, et al. Trypanosome IFT mutants provide insight into the motor location for mobility of the flagella connector and flagellar membrane formation. J Cell Sci. 2006;119(Pt 19):3935–3943. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Branche C, et al. Conserved and specific functions of axoneme components in trypanosome motility. J Cell Sci. 2006;119(Pt 16):3443–3455. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garcia-Gonzalo FR, Reiter JF. Scoring a backstage pass: Mechanisms of ciliogenesis and ciliary access. J Cell Biol. 2012;197(6):697–709. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201111146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang L, et al. TMEM237 is mutated in individuals with a Joubert syndrome related disorder and expands the role of the TMEM family at the ciliary transition zone. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89(6):713–730. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Petersen C, Aumüller G, Bahrami M, Hoyer-Fender S. Molecular cloning of Odf3 encoding a novel coiled-coil protein of sperm tail outer dense fibers. Mol Reprod Dev. 2002;61(1):102–112. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Egydio de Carvalho C, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of a complementary DNA encoding sperm tail protein SHIPPO 1. Biol Reprod. 2002;66(3):785–795. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod66.3.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ghafouri-Fard S, Ghafouri-Fard S, Modarressi MH. Expression of splice variants of cancer-testis genes ODF3 and ODF4 in the testis of a prostate cancer patient. Genet Mol Res. 2012;11(4):3642–3648. doi: 10.4238/2012.October.4.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cha P-C, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies three loci associated with susceptibility to uterine fibroids. Nat Genet. 2011;43(5):447–450. doi: 10.1038/ng.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lambacher NJ, et al. TMEM107 recruits ciliopathy proteins to subdomains of the ciliary transition zone and causes Joubert syndrome. Nat Cell Biol. 2016;18(1):122–131. doi: 10.1038/ncb3273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Prevo B, Mangeol P, Oswald F, Scholey JM, Peterman EJG. Functional differentiation of cooperating kinesin-2 motors orchestrates cargo import and transport in C. elegans cilia. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17(12):1536–1545. doi: 10.1038/ncb3263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Langousis G, et al. Loss of the BBSome perturbs endocytic trafficking and disrupts virulence of Trypanosoma brucei. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(3):632–637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518079113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Poon SK, Peacock L, Gibson W, Gull K, Kelly S. A modular and optimized single marker system for generating Trypanosoma brucei cell lines expressing T7 RNA polymerase and the tetracycline repressor. Open Biol. 2012;2(2):110037. doi: 10.1098/rsob.110037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brun R, Schönenberger MJ. Cultivation and in vitro cloning or procyclic culture forms of Trypanosoma brucei in a semi-defined medium. Short communication. Acta Trop. 1979;36(3):289–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Redmond S, Vadivelu J, Field MC. RNAit: An automated web-based tool for the selection of RNAi targets in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2003;128(1):115–118. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(03)00045-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Inoue M, et al. The 14-3-3 proteins of Trypanosoma brucei function in motility, cytokinesis, and cell cycle. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(14):14085–14096. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412336200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Unnikrishnan A, Akiyoshi B, Biggins S, Tsukiyama T. An efficient purification system for native minichromosome from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;833:115–123. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-477-3_8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Trudgian DC, et al. Comparative evaluation of label-free SINQ normalized spectral index quantitation in the central proteomics facilities pipeline. Proteomics. 2011;11(14):2790–2797. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201000800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Woodward R, Carden MJ, Gull K. Immunological characterization of cytoskeletal proteins associated with the basal body, axoneme and flagellum attachment zone of Trypanosoma brucei. Parasitology. 1995;111(Pt 1):77–85. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000064623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kohl L, Sherwin T, Gull K. Assembly of the paraflagellar rod and the flagellum attachment zone complex during the Trypanosoma brucei cell cycle. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1999;46(2):105–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1999.tb04592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dacheux D, et al. A MAP6-related protein is present in protozoa and is involved in flagellum motility. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e31344. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Morriswood B, et al. The bilobe structure of Trypanosoma brucei contains a MORN-repeat protein. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2009;167(2):95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lacomble S, et al. Three-dimensional cellular architecture of the flagellar pocket and associated cytoskeleton in trypanosomes revealed by electron microscope tomography. J Cell Sci. 2009;122(Pt 8):1081–1090. doi: 10.1242/jcs.045740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.