Abstract

Protein phosphatase magnesium-dependent-1A (PPM1A) dephosphorylates SMAD2/3, which suppresses TGF-β signaling in keratinocytes and during Xenopus development; however, potential involvement of PPM1A in chronic kidney disease is unknown. PPM1A expression was dramatically decreased in the tubulointerstitium in obstructive and aristolochic acid nephropathy, which correlates with progression of fibrotic disease. Stable silencing of PPM1A in human kidney-2 human renal epithelial cells increased SMAD3 phosphorylation, stimulated expression of fibrotic genes, induced dedifferentiation, and orchestrated epithelial cell-cycle arrest via SMAD3-mediated connective tissue growth factor and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 up-regulation. PPM1A stable suppression in normal rat kidney-49 renal fibroblasts, in contrast, promoted a SMAD3-dependent connective tissue growth factor and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1–induced proliferative response. Paracrine factors secreted by PPM1A-depleted epithelial cells augmented fibroblast proliferation (>50%) compared with controls. PPM1A suppression in renal cells further enhanced TGF-β1–induced SMAD3 phosphorylation and fibrotic gene expression, whereas PPM1A overexpression inhibited both responses. Moreover, phosphate tensin homolog on chromosome 10 depletion in human kidney-2 cells resulted in loss of expression and decreased nuclear levels of PPM1A, which enhanced SMAD3-mediated fibrotic gene induction and growth arrest that were reversed by ectopic PPM1A expression. Thus, phosphate tensin homolog on chromosome 10 is an upstream regulator of renal PPM1A deregulation. These findings establish PPM1A as a novel repressor of the SMAD3 pathway in renal fibrosis and as a new therapeutic target in patients with chronic kidney disease.—Samarakoon, R., Rehfuss, A., Khakoo, N. S., Falke, L. L., Dobberfuhl, A. D., Helo, S., Overstreet, J. M., Goldschmeding, R., Higgins, P. J. Loss of expression of protein phosphatase magnesium-dependent 1A during kidney injury promotes fibrotic maladaptive repair.

Keywords: TGF-β, PAI-1, CTGF, PTEN, renal fibrosis

Renal fibrotic disorders are generally refractive to current therapies. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) affects >12% of the U.S. population alone (1–4), with CKD risk factors (e.g., diabetes and hypertension) likely to increase worldwide in the coming decades. Renal replacement therapy, either dialysis or transplantation, is inadequate to meet patient demand, which further adds to the increasing public health burden (1–4).

Diabetic, hypertensive, acute or toxic, and obstructive kidney injury result in maladaptive repair (i.e., epithelial cell-cycle arrest and death, secretion of fibrotic factors, persistent inflammation, and accumulation of extracellular matrix–producing myofibroblasts), which eventually culminates in progressive fibrosis, tissue scarring, and end-stage renal disease (1–8). Regardless of the initial insult, activation of the TGF-β pathway is a prominent driver of a dysfunctional repair response, which leads to fibrosis (5–11). Binding of TGF-β1 ligands to the RI/RII receptor complex initiates both canonical SMAD2/3 and noncanonical (e.g., reactive oxygen species, ataxia telangiectasia mutated, p53, epidermal growth factor receptor, MAPK, Rho-GTPases) downstream signaling in kidney cells (9–15). Subsequent assembly of multimeric transcriptional complexes (e.g., SMADs, p53) leads to elevated expression of profibrotic target genes [e.g., plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), extracellular matrix proteins] and context-dependent phenotypic responses (e.g., cell-cycle arrest, proliferation, or apoptosis) (9–11, 13–15).

As a master regulator of organ fibrosis and vascular disease, TGF-β1 signal propagation is subjected to extensive negative control at the level of receptor activity, SMAD2/3 phosphorylation, SMAD2/3 nuclear translocation or exit, transcriptional complex assembly, and target promoter engagement, thereby tightly regulating associated transcriptional and biologic responses (9–11, 16, 17). Deficiencies in key negative regulators of the TGF-β pathway [e.g., bone morphogenic protein-6/7 (BMP-6/7), Sloan Kettering Institute proto-oncogene (Ski), Ski-related novel gene (Sno), and SMAD7] are evident during progression of renal disease. BMP-6/7–mediated activation of SMAD1/4/5, for example, antagonizes the TGF-β1–induced SMAD2/3 pathway (18, 19). Loss of BMP-6/7 signaling, evident during kidney injury, leads to exacerbated TGF-β1 responses and renal disease (18, 19). SMAD2/3 activation is inhibited by SMAD7 and the SMAD2/3 corepressors, Ski and SnoN, which suppresses target gene expression (16, 20). Progression of renal disease is accompanied by loss—via ubiquitin-dependent degradation—of several negative regulators (e.g., SMAD7, Ski, SnoN), which leads to persistent TGF-β1 signaling in the failing kidney (20–22). Gene transfer of SMAD7 to the kidney dramatically reduced interstitial fibrosis induced by unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) (23).

Protein phosphatase magnesium-dependent 1A (PPM1A; also known as protein phosphatase 2Cα) has been recently shown to have C-terminal SMAD2/3 phosphatase activity, a critical event in the termination of TGF-β1 signaling (24). We recently demonstrated that TGF-β1 stimulation reduces the nuclear fraction of PPM1A via Rho/ROCK-dependent mechanisms, thereby further enhancing SMAD3-dependent target gene (e.g., PAI-1) expression in vascular smooth muscle cells (25). This study, to our knowledge, presents the first investigation of the potential deregulation and mechanistic involvement of PPM1A in progression of chronic kidney injury and details upstream and downstream effectors of PPM1A in the context of renal pathology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and creation of stable cell lines

Human kidney-2 (HK-2) proximal tubular epithelial cells and normal rat kidney-49 fibroblast (NRK-49F) cells were grown in DMEM that was supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). To generate stable cell lines, semiconfluent HK-2 and NRK-49F cells were treated with 5 μg/ml polybrene in 10% FBS/DMEM and infected with PPM1A or control lentiviral particles (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and incubated overnight. After incubation in fresh complete medium for 24 h, cells stably expressing PPM1A or control short hairpin RNA (shRNA) were selected with 5 μg/ml puromycin + 10% FBS/DMEM with medium changes every 3 d. PPM1A knockdown was confirmed by Western blot analysis. To generate SMAD3-, PAI-1–, and CTGF-silenced HK-2 or NRK-49F cells in the context of a stable PPM1a knockdown, 60% confluent PPM1a shRNA-expressing cells were reinfected (for 1 d) with control or SMAD3, PAI-1, or CTGF shRNA lentiviral constructs (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), followed selection in puromycin. In transient PPM1A overexpression experiments, HK-2 and NRK-49F cells or phosphate tensin homolog on chromosome 10 (PTEN) shRNA stably expressing cells were infected with PPM1A human ORF cDNA or control Lentifect lentiviral particles (GeneCopoeia, Rockville, MD, USA) for 24–48 h. Cells were allowed to recover for 2–3 d before TGF-β1 stimulation or were subjected to puromycin selection. For transient PPM1A silencing, 50% confluent NRK-49F cells were transfected with Accell control constructs or PPM1a small interfering RNA (siRNA; 250–500 nM; Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO, USA) by using Accell siRNA delivery medium for 2–3 d, followed by a 2-d recovery in 5% FBS/DMEM. Western blot analysis confirmed PPM1A expression levels in both approaches.

Induction of renal fibrosis in response to UUO

Mice were anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation, and a small incision was made in the flank under aseptic conditions. The left ureter was exposed and ligated with two 5-0 silk sutures. Control mice underwent sham procedures but not ureteral ligation. At 7 and 14 d postsurgery, all animals were euthanized, and obstructed (UUO), contralateral, and sham kidneys were harvested. This protocol was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the University of Utrecht (Utrecht, The Netherlands).

Aristolochic acid–induced nephropathy

C57Bl/6 male mice received an i.p. injection of aristolochic acid (AA) sodium salt (5 mg/kg body weight dissolved in distilled water; A9451; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) once a day consecutively for 5 d or NaCl vehicle (control animals) alone. Urine creatinine levels were measured to confirm renal injury in response to AA (J2L Elitech, LabartheInard, France). At 25 d after initial injections, mice in both groups were euthanized by ketamine-xylazine-atropine.

Plasma urea measurements

Plasma urea concentrations were determined by using a colorimetric assay (Diasys Diagnostic Systems, Holzheim, Germany). Standard curves were generated by using commercially available urea (Diasys Diagnostic Systems).

Renal epithelial-fibroblast crosstalk studies

Conditioned medium that was isolated from PPM1A shRNA or control shRNA HK-2 epithelial cells (at similar density) were directly added to identically confluent control shRNA stably expressing NRK-49F fibroblasts for 3 d. Fibroblast growth was measured by using the Sceptor 2.0 Handheld Automated Cell Counter (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) according to manufacturer recommendations.

Immunoblotting

Western blots were performed as described (26). Specific antibodies used include rabbit anti-PPM1A (1:2000), mouse anti-PPM1A (1:1000), rabbit anti–phospho-SMAD3 (1:1000), rabbit anti-fibronectin (1:10,000), rabbit anti-CTGF (1:2000), rabbit anti–α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) (1:2000), and rabbit anti–collagen IV (1:500; all from Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA). Rabbit anti-PTEN (1:2000), rabbit anti-vimentin (1:2000), rabbit anti-pSMAD2/3 (1:1000), rabbit anti–glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; 1:5000), goat anti-CTGF (1:1000), and rabbit anti p21 (1:1000) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Rabbit anti–PAI-1 (1:3000) was previously described (26). Membranes were incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies and immunoreactive proteins were visualized with ECL reagent and quantitated by densitometry. GAPDH provided a normalization control.

Subcellular fractionation

PTEN shRNA- and control shRNA-expressing HK-2 cells were scraped in PBS, pelleted by centrifugation, and resuspended in hypertonic solution A (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 10 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 0.1 mM EGTA) that was supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail and shaken on ice for 20 min. Solution B (3% NP-40) was added, followed by centrifugation (8000 rpm, 60 s) to isolate cytoplasmic fraction. Remaining pellet was resuspended in solution C (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 0.42 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, and 1 mM DTT) that was supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail, subjected to several freeze/thaw cycles, and incubated overnight in the cold room. Nuclear (supernatant) fraction was separated at 8000 rpm for 5 min. GAPDH and lamin A/C provided markers of the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions, respectively.

Immunohistochemistry

Deparaffinized kidney sections were probed with primary Abcam rabbit antibodies to PPM1A (1:500) and PTEN (1:500) and morphometric analyzed as detailed (26).

Cell-cycle analysis

Control shRNA- and PPM1A shRNA-expressing HK-2 cells were grown in serum-containing medium that was supplemented with Puromycin for 2–3 d. Trypsin-harvested cells were incubated with soybean trypsin inhibitor for 5 mins, washed twice in PBS, and fixed in suspension in 95% ethanol for 1 h. Cells were washed in PBS 2 times and were incubated with RNaseA (20 μl/ml) and propidium iodide (2.5 μg/ ml) in PBS/Triton X-100 for 2 h in the dark. Cell-cycle distributions were measured by using a FACS Calibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and analyzed with FlowJo software (FlowJo, Ashland, OR, USA).

Statistical analysis

Two-tailed Student’s t test and ANOVA with Tukey post hoc analysis were used to assess statistical differences. A value of P < 0.05 is considered significant.

RESULTS

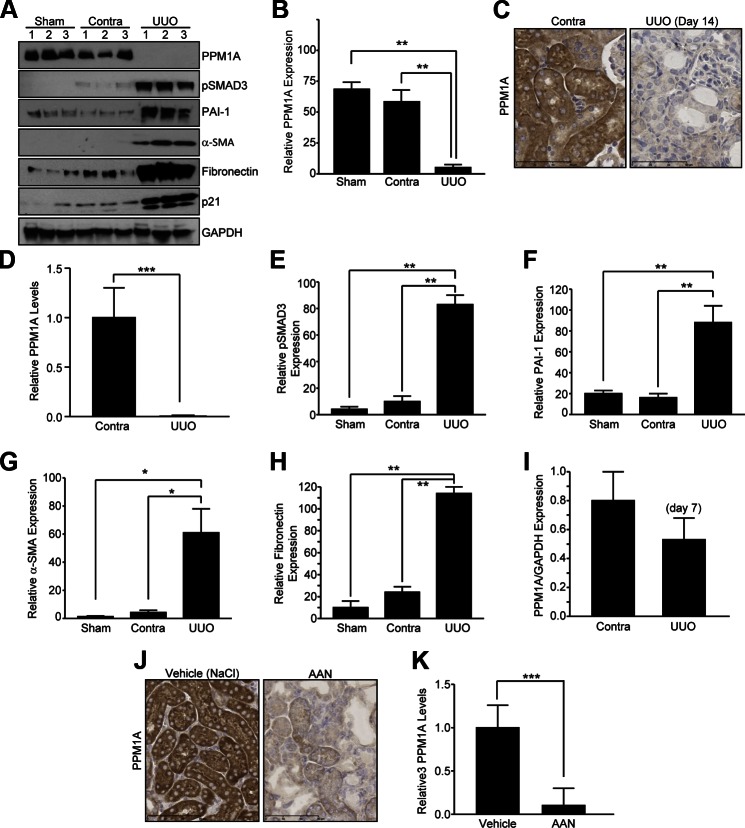

Progressive loss of PPM1a expression in CKD induced by UUO and AA nephropathy

Two well-established mouse models of tubulointerstitial fibrosis were used to investigate potential PPM1A deregulation in CKD. UUO is a highly reproducible model, with little interanimal variation for inducing renal fibrosis, and it mimics obstructive uropathy in children (27). AA nephropathy (AAN) is also an established CKD model, and AA administration in mice recapitulates certain features of human nephropathy that are evident in Chinese and Balken populations as a result of consumption of this toxic herb (28). In late stages of UUO (d 14), renal PPM1A expression is dramatically decreased by 90% as evident in immune blot analysis (Fig. 1A, B; P < 0.01, UUO vs. contralateral or sham controls) and immunohistochemistry (Fig. 1C, D; P < 0.001, UUO vs. contralateral kidneys), which exhibited prominent tubular expression of this phosphatase (Fig. 1A–D). PPM1A reduction in the obstructed kidney correlated with elevated SMAD3 activation (Fig. 1A, E; P < 0.01) and expression of PAI-1 (Fig. 1A, F; P < 0.01), α-SMA (Fig. 1A, G; P < 0.05), fibronectin (Fig. 1A, H; P < 0.01), and p21 (Fig. 1). Time course analysis indicates that renal expression of PPM1A is partially decreased (35%) by d 7 after UUO compared with contralateral controls (Fig. 1I), which suggests progressive PPM1A loss in chronic renal injury. A similar loss of PPM1A expression (>90%) was evident in the tubulointerstitial regions in AA-injured kidneys compared with NaCl vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 1J, K; P < 0.001), which indicated that PPM1A deregulation is common in both mouse models of CKD. Furthermore, plasma urea levels were elevated in mice that underwent renal obstruction (Supplemental Fig. 1A; P < 0.05 vs. sham control) and AAN (Supplemental Fig. 1B; P < 0.05 vs. NaCl vehicle), which was further indicative of the state of renal malfunction in diseased mice in response to both types of renal injury.

Figure 1.

Tubular and interstitial loss of PPM1A expression in late stages of UUO and AA nephropathy (AAN). A) Immunoblotting for PPM1A (A, B), pSMAD3 (A, E), PAI-1 (A, F), α-SMA (A, G), fibronectin (A, H), and GAPDH (a loading and normalization marker) expression levels in sham, contralateral (contra), and obstructed (UUO) mouse kidneys at d 14 postsurgery (n = 3–6 animals per experimental condition). Numbers 1–3 in panel A depict 3 individual mice for the indicated group. C) Immunohistochemistry images of paraffin sections of the contralateral or ligated (UUO; d 14) kidneys derived from the same mice (A) by using a rabbit anti-PPM1A antibody. D) Quantitative image analysis of diaminobenzidine (DAB) expression to assess differences in PPM1A expression between UUO and contralateral kidneys, setting staining intensity of the contra kidney as 1. B, E–I) Histograms depict relative expression of indicated markers in UUO and contralateral or sham kidneys. I) Western blot analysis for PPM1A and GAPDH expression in lysates derived from contralateral and UUO kidneys at d 7 postsurgery (n = 3 mice). J) Immunostaining of kidney sections from mice treated with aristolochic acid (AAN; 5 mg/kg for 25 d) or NaCl vehicle. K) Histogram illustrates relative PPM1A levels in the AAN- and NaCl-administered kidneys, setting DAB intensities for NaCl-treated controls as 1. Data are given as means ± sd. Scale bars, 60 μM (C), 90 μΜ (J). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

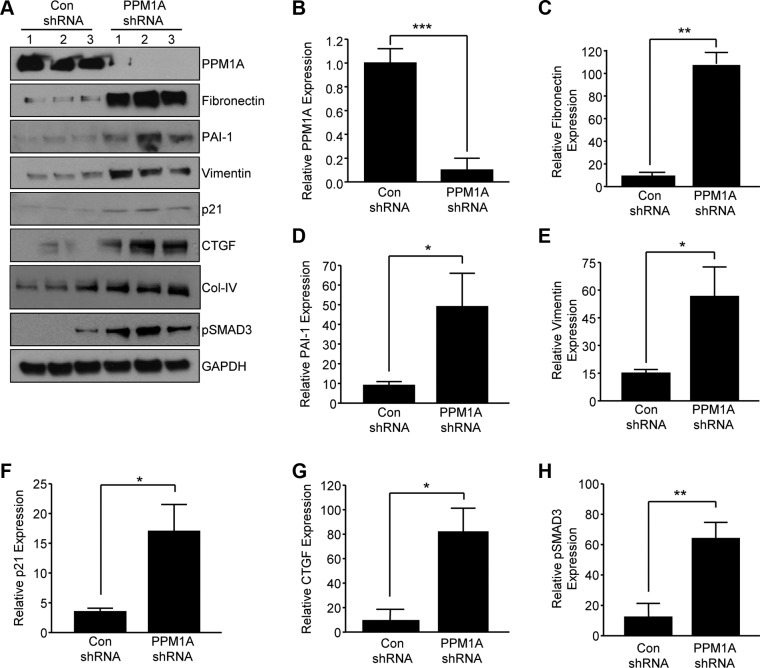

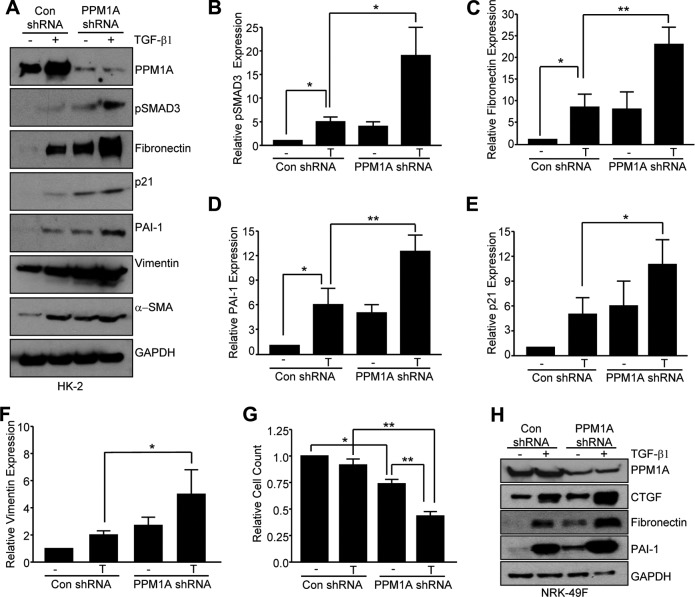

Stable silencing of PPM1A expression in human renal epithelial cells promoted a fibrogenic response

To mimic PPM1A loss in renal tubules in response to kidney injury, stable silencing of PPM1A in HK-2 human renal epithelial cells via lentiviral transduction was used, which results in a >90% decrease in PPM1A protein expression compared with control shRNA-transduced cultures (Fig. 2A, B; P < 0.001). Prolonged PPM1A suppression (maintained for 5–7 d) increased expression of fibronectin (Fig. 2A, C;10-fold, P < 0.01), PAI-1 (Fig. 2A, D; 5-fold, P < 0.05), vimentin (Fig. 2A, E; 3.7-fold, P < 0.05), p21 (Fig. 2A, F; 4-fold, P < 0.05), CTGF (Fig. 2A, G; 7-fold, P < 0.05), collagen IV (Fig. 2A), and pSMAD3 (Fig. 2A, H; 7.5-fold, P < 0.01) expression compared with control shRNA-expressing cells.

Figure 2.

Prolonged silencing of PPM1a expression in HK-2 epithelial cells leads to fibrotic gene reprogramming. A) Subconfluent control (con) shRNA and PPM1A shRNA stably expressing cell cultures were maintained in low serum (0.1%) medium for 5–7 d and cellular lysates that were immunoblotted with antibodies to PPM1A (A, B), fibronectin (A, C), PAI-1 (A, D), vimentin (A, E), p21 (A, F), CTGF (A, G), collagen IV (Col-IV; A), pSMAD3 (A, H), and GAPDH (A). Numbers 1–3 in panel A represent 3 independent cultures of the indicated cell types. B–H) Plots summarize relative expression of indicated markers, setting levels in controls as 1. Data are given as means ± sd. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 vs. con shRNA.

Epithelial cell-cycle arrest upon PPM1A knockdown is orchestrated via SMAD3-mediated CTGF and PAI-1 up-regulation

PPM1A depletion is also accompanied by decreased epithelial cell growth (∼38%; Fig. 3A, B; P < 0.01) and G1 cell-cycle arrest (Fig. 3C), which is consistent with p21 up-regulation, compared with control shRNA transductants (Fig. 2). PPM1A silencing in HK-2 cells reflected a 5-fold increase in the fraction of cells with mesenchymal morphology (Fig. 3D; P < 0.001 vs. control shRNA), which suggested that PPM1A deregulation in epithelial dedifferentiation corresponded with the increased vimentin expression (Fig. 2). To evaluate SMAD3 as a downstream transducer of PPM1A down-regulation (given the activation of SMAD3 in PPM1A-depleted cells; Fig. 2), PPM1A stable knockdown HK-2 cells that were transduced with SMAD3 or control shRNA lentiviral particles and double-deficient cells were subjected to Western blot analysis to confirm SMAD3 reduction (Fig. 3E). Cells with stable dual PPM1A and SMAD3 silencing (PPM1A + SMAD3 shRNA cells) exhibit reduced expression of both PAI-1 and CTGF (Fig. 3E) compared with PPM1A cells that were stably infected with control shRNA lentivirus (PPM1A + control shRNA cultures). Growth inhibition evident in (PPM1A + control shRNA-expressing cultures was relieved in PPM1A + SMAD3 shRNA cells (Fig. 3F; P < 0.01), which suggested that SMAD3 activation in response to PPM1A loss mediated not only fibrotic gene expression but also suppression of epithelial proliferation. Furthermore, silencing of PAI-1 or CTGF expression (PPM1A + PAI-1 shRNA and PPM1A + CTGF shRNA cells) in stably PPM1A-depleted cells similarly rescued proliferative response in PPM1a + control shRNA double transductants (Fig. 3F; P < 0.01 vs. PPM1A + PAI-1 shRNA; P < 0.01 vs. PPM1A + CTGF shRNA), which indicated novel roles for PAI-1 and CTGF induction in the growth-inhibited phenotype associated with PPM1A deficiency.

Figure 3.

Stable silencing of PPM1A leads to epithelial dedifferentiation and cell-cycle arrest via SMAD3-dependent mechanisms. A) Stable PPM1A shRNA knockdown or control shRNA HK-2 cells (con; seeded at similar density) were grown for 7 d in 10% FBS-containing medium, then stained with Crystal Violet. B) Relative cell counts in triplicate cultures for each experimental condition were determined, setting values in controls as 1. **P < 0.01 vs. con shRNA cells. C) Flow cytometric analysis of propidium iodide–stained PPM1A shRNA– and con shRNA–expressing cells grown in complete medium for 2–3 d provided assessments of cell cycle distribution. Insets in each histogram highlight percentages of G1, S, and G2/M phase cells. D) Histogram illustrates the fraction of PPM1A-knockdown or control cells exhibiting fibroblast morphology after 5 d growth as a percentage of the total population. ***P < 0.001 vs. con shRNA. E) Immunoblotting of lysates derived from stably expressing PPM1A + con, PPM1A + SMAD3, (PPM1A + PAI-1, and PPM1A + CTGF shRNA double-tranductant HK-2 cells for SMAD3, PAI-1, CTGF, and GAPDH expression. F) Triplicate cultures of each of these 4, initially seeded equally (∼25,000 cells), cell types were grown for 3 d before cell count. Data are given as means ± sd. Scale bars, 200 μM. **P < 0.01 vs. PPM1A + con stably expressing cells.

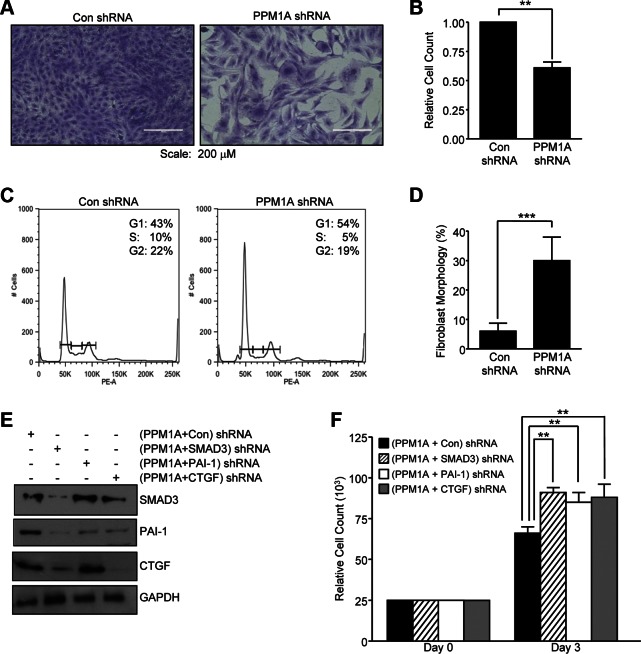

PPM1A deregulation in NRK-49F cells promoted a proliferative phenotype via SMAD3-CTGF-PAI-1 up-regulation

Stable PPM1A knockdown in NRK-49F renal fibroblasts increased pSMAD3 levels and expression of SMAD3 target genes PAI-1 and CTGF relative to control shRNA transductants (Fig. 4A). In sharp contrast to epithelial cells, PPM1A silencing in NRK-49F cells promoted growth (>50%) compared with control shRNA lentiviral-infected cultures (Fig. 4B, C; P < 0.01). Transient silencing of PPM1A expression via siRNA approaches in NRK-49F cells similarly produced a fibroproliferative response relative to control siRNA-expressing cells at d 5 after transfection (Fig. 4D, E; P < 0.05 vs. control siRNA). SMAD3 knockdown in stable PPM1A shRNA-expressing renal fibroblasts (PPM1A + SMAD3 shRNA cells) markedly reduced levels of PAI-1 and CTGF (Fig. 4F) and decreased (>50%) proliferation (Fig. 4G, H; P < 0.001) relative to PPM1A shRNA-expressing NRK-49F cells that were transduced with a control lentivirus (termed PPM1A + control shRNA cells). Similarly, dual stable silencing of PPM1A and PAI-1 (PPM1A + PAI-1 shRNA cultures) or PPM1A and CTGF (PPM1a + CTGF shRNA cells) suppressed growth relative to PPM1A + control shRNA fibroblasts (Fig. 4F–H; P < 0.001 for both PPM1A + PAI-1 shRNA and PPM1A + CTGF shRNA). These findings established that SMAD3-dependent PAI-1 and CTGF induction in response to PPM1A silencing are critical regulators of NRK-49F proliferation.

Figure 4.

Silencing of PPM1A in NRK-49F renal fibroblasts promotes fibroproliferative phenotype. A) NRK-49F cells stably expressing PPM1A or control shRNA (con) were grown for 3–5 d and lysates were probed for PPM1A, pSMAD3, PAI-1, CTGF, and GAPDH expression by Western blot analysis. B, C) Crystal Violet staining (B) and actual cell count analysis (C) of similarly seeded control and PPM1A shRNA fibroblasts after 3 d growth. Plot illustrates cell number (means ± sd) in triplicate cultures for each condition at d 3. **P < 0.01 vs. con shRNA. D, E) Extracts of similarly seeded control siRNA and PPM1A siRNA transfected NRK-49F cells after 5 d growth were Western blotted for PPM1A, fibronectin, and GAPDH (D) and cell count analysis (E). Plot represents the means ± sd of cell counts on triplicate cultures setting cell number in control siRNA–expressing fibroblasts as 1. *P < 0.05. F) Extracts of double shRNA construct NRK-49F cells PPM1A + con, PPM1A + SMAD3, PPM1A + PAI-1, and PPM1A + CTGF were blotted for SMAD3, PAI-1, CTGF, and GAPDH. G) These 4 double-transductant cell types cultures were seeded at similar densities and allowed to grow for 5 d before Crystal Violet staining and cell counting. Scale bar, 200 μM H) Histogram depicts means ± sd of triplicate cell counts, setting the relative cell number in PPM1A + con shRNA–expressing cultures as 1. **P < 0.01 vs. PPM1A + con 49F cells.

PPM1A depletion exacerbates TGF-β1–induced fibrotic phenotype

Concurrent loss of PPM1A expression and TGF-β1/SMAD3 activation in fibrotic kidneys (Fig. 1) warranted an investigation of possible cooperation between these events in renal injury. TGF-β1–induced SMAD3 phosphorylation (Fig. 5A, B; P < 0.05) as well as fibronectin (Fig. 5A, C; P < 0.01), PAI-1 (Fig. 5A, C; P < 0.01), p21 (Fig. 5A, D; P < 0.05), and vimentin (Fig. 5A, E; P < 0.05) expression in control shRNA transductants was further enhanced in PPM1A-depleted HK-2 cells. Moreover, TGF-β1–dependent reduction in cell number (∼12%) in control conditions was further increased (∼58%) by PPM1A silencing (Fig. 5F; P < 0.01). TGF-β1–mediated fibronectin, PAI-1, and CTGF expression in NRK-49F cells that were stably transduced with control shRNA was similarly further augmented in stable PPM1A knockdown fibroblasts (Fig. 5H).

Figure 5.

PPPM1A and TGF-β1 cooperate in induction of fibrotic genes and epithelial proliferative arrest. A–F) Serum-deprived confluent PPM1A- or control shRNA-expressing cultures remained untreated (−) or were stimulated (+) with TGF-β1(2 ng/ml) for 24 h and lysates were processed by Western blot analysis for PPM1A (A), pSMAD3 (A, B), fibronectin (A, C), PAI-1 (A, D), p21 (A, E), vimentin (A, F), and GAPDH expression (A). B–F) Plots illustrate the means ± sd for pSMAD3, fibronectin, PAI-1, p21, and vimentin levels (for 3 independent experiments); expression of pSMAD3, fibronectin, PAI-1, p21, and vimentin in the untreated (−) control shRNA (con) cells was set to 1 in each case. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 vs. con shRNA cells stimulated with TGF-β1 (T). Con shRNA or PPM1A shRNA-expressing HK-2 cells seeded at similar density were grown in low serum (2.5%) medium for 3 d with (T) or without (−) TGF-β1 before cell count analysis. G) Plot presents summary of data (means ± sd), setting cell number in unstimulated (−) con shRNA-expressing cells as 1. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 as indicated between groups. H) Serum-deprived NRK-49F cells stably expressing control or PPM1A shRNA constructs were stimulated with TGF-β1 for 24 h before Western blot determination of PPM1A, CTGF, fibronectin, PAI-1, and GAPDH levels.

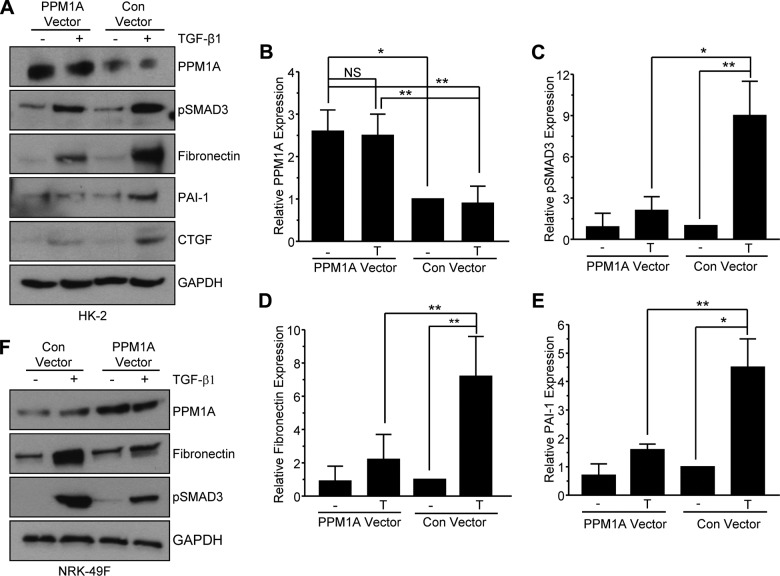

PPM1A ectopic expression inhibits TGF-β1–induced fibrotic programming

Transient overexpression of PPM1A (2.5-fold more than endogenous levels in HK-2 renal epithelial cells; Fig. 6A, B; P < 0.05) by lentiviral transduction effectively suppressed TGF-β1–induced SMAD3 activation (Fig. 6A, C; P < 0.05) and reduced fibronectin (Fig. 6A, D; P < 0.01) and PAI-1 (Fig. 6A, E; P < 0.01) levels compared with cytokine-stimulated, lentiviral-infected controls. Ectopic expression of PPM1A in NRK-49F fibroblasts similarly inhibited TGF-β1–induced SMAD3 phosphorylation and fibronectin expression (Fig. 6F). Collectively, these findings strongly implicate PPM1A as a negative regulator of the TGF-β1/SMAD3-driven renal fibrotic cascades.

Figure 6.

Transient overexpression of PPM1A inhibits the TGF-β1–driven fibrotic response in HK-2 and NRK-49F cells. A–E) Serum-starved HK-2 cells transduced with either a lentiviral control (con) or PPM1A expression vector were stimulated (+) or not (−) with TGF-β1 for 24 h before Western blot analysis for PPM1A (A, B), pSMAD3 (A, C), fibronectin (A, D), and PAI-1 (A, E). B–E) Histograms illustrate a summary (means ± sd) of relative levels of indicated proteins in triplicate experiments, setting values for control vector transduced HK-2 cells in the absence (−) of TGF-β1 (T) stimulation as 1. F) Western blot analysis of PPM1A, fibronectin, and pSMAD3 in NRK-49F renal fibroblasts treated (+) or untreated (−) with TGF-β1 for 24 h after infection with control or PPM1A expression vector lentiviral particles. NS, not significant. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 as indicated between groups.

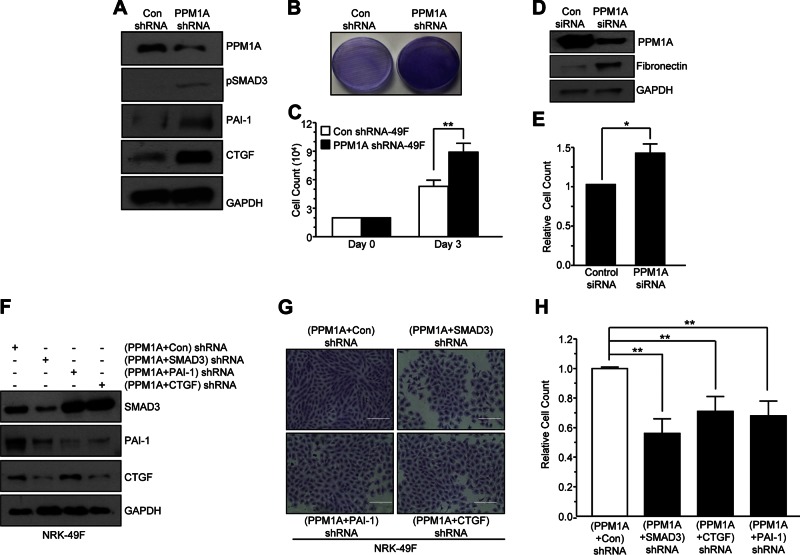

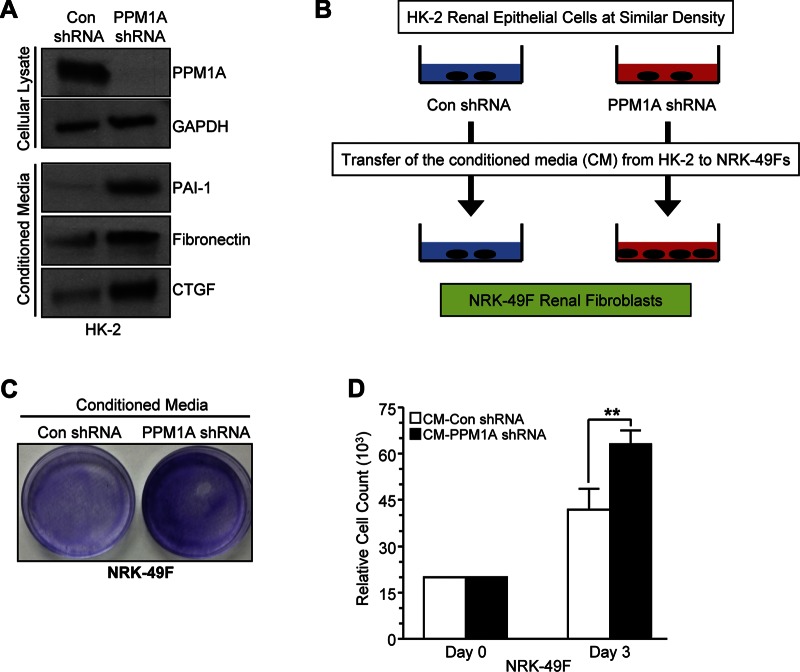

Epithelial paracrine factor secretion consequent to PPM1A silencing promotes renal fibroblast proliferation

Paracrine factors (e.g., CTGF and TGF-β1) secreted by growth-arrested epithelial cells promote fibroblast proliferation during the transition of acute renal injury to renal fibrosis and CKD (5, 29). PPM1A depletion in HK-2 cells (Fig. 7, top) also triggers secretion of PAI-1, fibronectin, and CTGF as evident by analysis of conditioned medium derived from PPM1A or control shRNA-expressing cells (Fig. 7, bottom). To investigate potential renal epithelial-fibroblast crosstalk in the context of epithelial PPM1A silencing, conditioned medium from control or PPM1A-silenced cells grown in low serum were transferred to identically seeded control shRNA-expressing NRK-49F fibroblasts (Fig. 7B). After a 3 d of subsequent incubation, crystal violet staining (Fig. 7C) and cell counts indicated that PPM1A-depleted HK-2 conditioned medium triggered NRK-49F growth (Fig. 7D, ∼50%; P < 0.01) compared with medium derived from control shRNA-expressing HK-2 cultures. These data suggest that epithelial PPM1A deregulation in renal injury could promote epithelial-mesenchymal communication via nonautonomous mechanisms.

Figure 7.

Conditioned medium from epithelial PPM1A-knockdown cells promotes renal fibroblast proliferation. A) Cell lysates from control (con) and PPM1A shRNA-expressing HK-2 cells were Western blotted for PPM1A and GAPDH (top). Conditioned medium (CM) from these same cultures were probed for PAI-1, fibronectin, and CTGF (bottom). B–D) As outlined in the experimental design (B), CM isolated from equally dense PPM1A knockdown and/or control HK-2 cells (CM-PPM1A shRNA and CM-con shRNA, respectively; C, D) were directly added to NRK-49F fibroblast cultures at similar initial densities. Effects on growth were assessed 3–5 d later by Crystal Violet staining (C) and cell count. D) Plot illustrates cell count data (means ± sd) from triplicate cultures/condition on d 3 after transfer of CM. **P < 0.01 vs. NRK-49F cells grown in CM from control shRNA HK-2 cells.

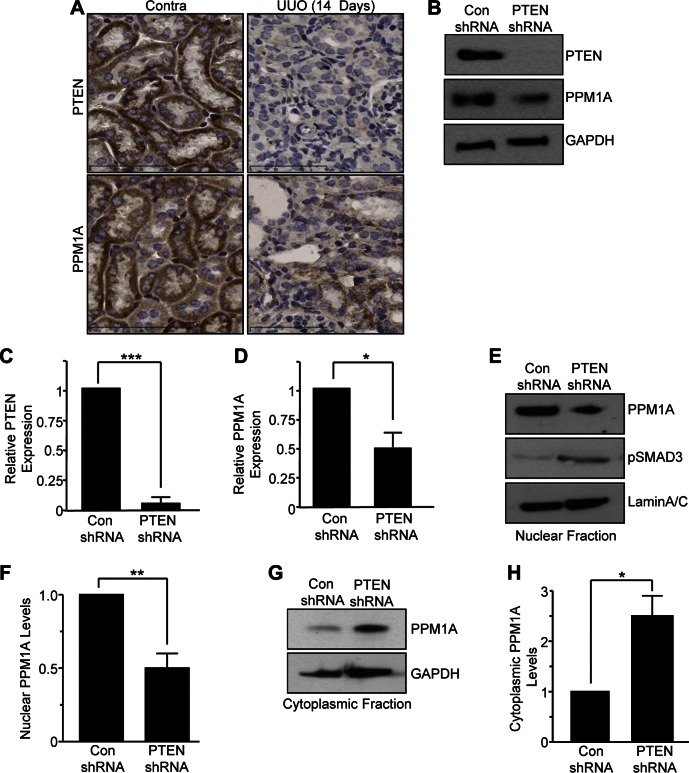

PTEN is an upstream regulator of renal PPM1A

Relatively little is known about upstream mediators of PPM1A control in general or in the context of tissue injury. Tumor suppressor PTEN interacts with PPM1A to stabilize its expression in scleroderma (30). PTEN expression, in fact, is lost in several models of renal injury (e.g., UUO, AAN) and PTEN depletion in epithelial cells promoted secretion of fibrotic factors, G1 cell-cycle arrest, and dedifferentiation, in part, via SMAD3-dependent mechanisms (26), which is reminiscent of the phenotypic consequences of PPM1A silencing in HK-2 cells (Figs. 2 and 3). These findings, as well as the observation that PTEN and PPM1A expression in renal tubules and interstitial cells is significantly reduced in late stages of obstructive nephropathy (UUO; d 14) (Fig. 8A), prompted an investigation of PTEN as an upstream regulator of PPM1A in renal pathology. PTEN-silenced HK-2 cells (Fig. 8B, C; 95% decrease; P < 0.001) were used to mimic epithelial loss of PTEN expression in kidney injury. These cells, when maintained in low serum–containing medium, not only have reduced total PPM1A expression (∼52%; Fig. 8B, D; P < 0.05) but also decreased nuclear PPM1A levels (>50%; Fig. 8E, F; P < 0.01) as well as increased PPM1A in the cytoplasmic fraction (>2.4-fold; Fig. 8G, H; P < 0.05) compared with control shRNA-expressing epithelial cultures. Decreased total PPM1A levels and its altered distribution (from nucleus to cytoplasm) evident in PTEN knockdown cultures is associated with increased SMAD3 activation compared with control shRNA transductants (Fig. 8E) (26).

Figure 8.

PTEN regulates PPM1A levels and intracellular localization in HK-2 cells. A) UUO and contralateral (contra) kidneys (d 14 after surgery) were immunostained with rabbit antibodies to PTEN and PPM1A. Scale bars, 60 μM. B) Cell extracts from PTEN-knockdown and control shRNA-transduced HK-2 cells (maintained in low serum medium for 5 d) were Western blotted for PTEN, PPM1A, and GAPDH. C, D) Histograms illustrate relative PTEN and PPM1A levels (means ± sd) in PTEN-depleted HK-2 cells for 3 separate experiments vs. control shRNA (con) lentiviral-infected cells. E–H) Nuclear (E, F) and cytoplasmic fractions (G, H) isolated from parallel PTEN and control shRNA cultures as described in panel B were probed for PPM1A and pSMAD3 (E); lamin A/C and GAPDH provided protein loading controls for the nuclear (E) and cytoplasmic (G) fractions, respectively. Plots illustrate the relative PPM1A nuclear (F) and cytoplasmic (H) levels (means ± sd) in 3 independent experiments, setting PPM1A expression in control shRNA cultures as 1. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 vs. control shRNA cells; ***P < 0.001.

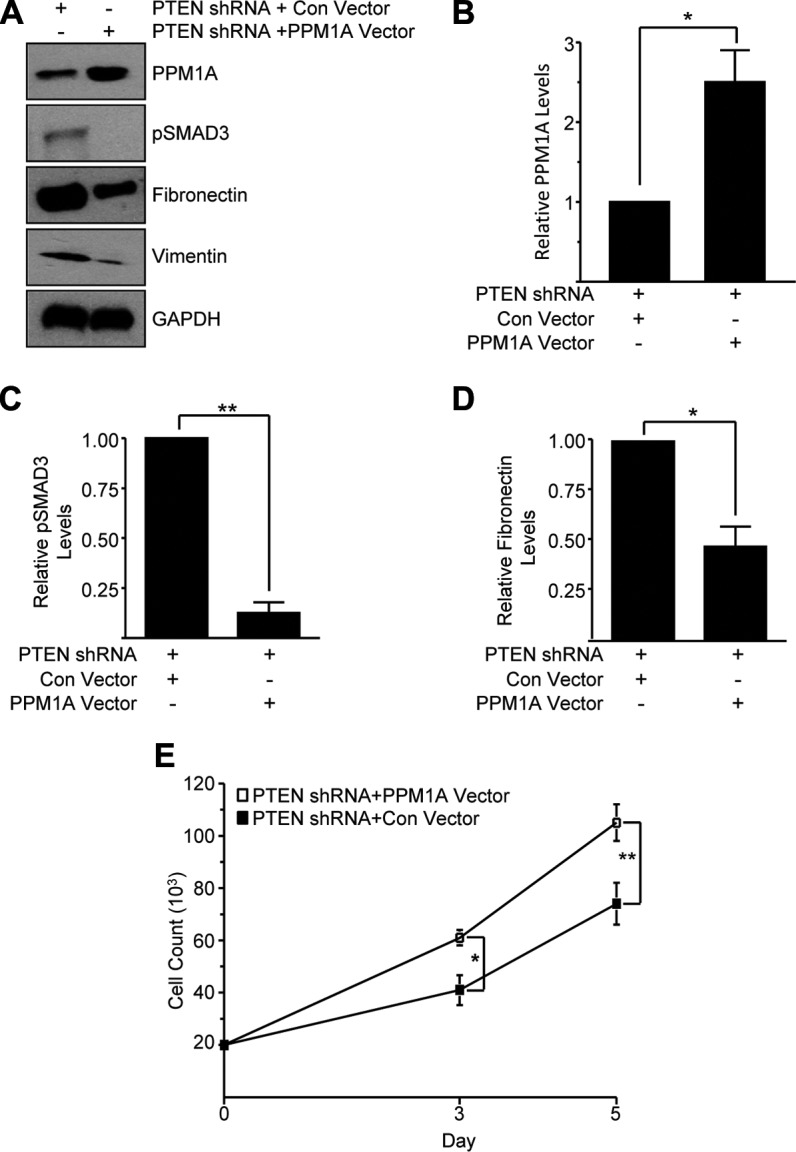

Forced overexpression (>2.3-fold increase) of PPM1A (Fig. 9A, B; P < 0.05) by lentiviral transduction in PTEN-depleted HK-2 cells (PTEN shRNA + PPM1A vector) indeed attenuated SMAD3 phosphorylation (>85%; Fig. 9A, C; P < 0.01), fibronectin expression (>53%; Fig. 9A, D; P < 0.05), and vimentin expression (Fig. 9A) relative to control vector–infected PTEN shRNA-expressing cells (PTEN shRNA + control vector cells; Fig. 9). Similarly, cell growth of PTEN shRNA + control vector HK-2 cultures was significantly increased by PPM1A ectopic expression (Fig. 9E; P < 0.01) at d 5. These findings demonstrate that pSMAD3 inactivation by PPM1A overexpression overrides pSMAD3-mediated proliferative arrest imposed by epithelial PTEN depletion, which is consistent with previous observations (26). These data clearly implicate PTEN as an upstream regulator of PPM1A in the orchestration of epithelial dysfunction in renal injury.

Figure 9.

Ectopic PPM1A ectopic expression reverses epithelial dysfunction induced by PTEN depletion. A–D) Extracts from PTEN-depleted HK-2 cells infected with lentiviruses engineered to deliver a control (con) vector or PPM1A expression construct (termed PTEN shRNA + con vector and PTEN shRNA + PPM1A vector, respectively) were Western blotted for PPM1A (A, B), pSMAD3 (A, C), fibronectin (A, D), vimentin, and GAPDH (A). Cell counts of equally seeded PTEN shRNA + con vector– and PTEN shRNA + PPM1A vector–expressing cells were done on d 3 and 5 of culture. E) Plot depicts cell number (means ± sd) in triplicate cultures for each cell type. *P ≤ 0.05; **P < 0.01 vs. PTEN shRNA + con vector cells.

DISCUSSION

Loss of PPM1A expression—in both UUO and AAN models of renal injury—initiates production of fibrotic factors, including PAI-1, CTGF, and fibronectin, and induces epithelial dedifferentiation, which is consistent with vimentin and α-SMA up-regulation, as well as epithelial G1 arrest, whereas PPM1A silencing in renal fibroblasts generates a proliferative phenotype. TGF-β1–stimulated fibrotic gene expression in renal cells requires SMAD3 activation (13–15) and, accordingly, ectopic expression of PPM1A-attenuated TGF-β1–induced SMAD3 phosphorylation and subsequent induction of fibrotic genes in renal epithelial cells and fibroblasts (Fig. 6). Collectively, these findings establish PPM1A as a novel suppressor of TGF-β1/SMAD3 signaling and that prolonged PPM1A loss in renal cells promotes a fibrotic phenotype.

PAI-1 and CTGF are known causative factors and downstream targets of the TGF-β1/SMAD3 pathway in renal fibrosis (10, 11, 31), yet the role CTGF and PAI-1 induction in cell growth control during renal injury is less well understood. Our current findings establish PAI-1 and CTGF as important regulators of epithelial proliferative arrest initiated by PPM1A depletion as dual silencing of PAI-1 or CTGF with PPM1A-rescued HK-2 cells from the proliferative inhibition imposed by PPM1A silencing (Fig. 3). In contrast, fibroblast growth in response to PPM1A silencing is blocked by SMAD3, PAI-1, or CTGF shRNA lentiviral transduction in PPM1A-depleted NRK-49F cells (Fig. 4). PAI-1 and CTGF up-regulation downstream of PPM1A loss, therefore, promotes renal fibroblast proliferation while imposing proliferative defects in epithelial cells, highlighting novel roles for PAI-1 and CTGF in maladaptive cell cycle control in tubular-interstitial pathology. Moreover, loss of PPM1A expression in epithelial cells could promote epithelial-fibroblast communication during renal injury given that certain fibrotic factors (e.g., CTGF, PAI-1) secreted by PPM1A-depleted HK-2 cells promoted NRK-49F fibroblast proliferation (Fig. 7) (29).

UUO- and AA-induced renal injury is accompanied by TGF-β1 up-regulation in the tubulointerstitium, and fibrotic progression in both models is mediated by SMAD3-dependent mechanisms (9–11, 13, 32). Concurrent TGF-β1/SMAD3 activation and loss of PPM1A in renal tubular cells (Fig. 1) exacerbates TGF-β1–driven fibrosis marker gene expression and reduces epithelial cell growth. These studies identify PTEN as an upstream regulator of PPM1A expression and establish that the PTEN loss-induced, SMAD3-mediated renal fibrotic phenotype is linked to PPM1A deficiency and cellular mislocalization (Fig. 8) (26). Accordingly, loss of PTEN in renal injury correlated with decreased PPM1A expression in later stages of renal obstruction, which further highlights in vivo relevance.

Several recent studies suggest that PPM1A deregulation in nonrenal pathologies is involved in tissue response to injury. Expression of VEGF and angiogenesis, inflammation, and expression of TGF-β1 target genes during experimental ocular repair is further enhanced in PPM1A-knockout mice compared with wild-type counterparts, which suggests that PPM1A also serves as an inhibitor of TGF-β1 signaling during eye injury (33). PPM1A expression is also decreased at sites of experimental skin trauma, and PPM1A genetic silencing in the skin in mice resulted in delayed dermal wound closure via SMAD2/3-dependent pathways compared with control counterparts that were identically subjected to dermal injury (34).

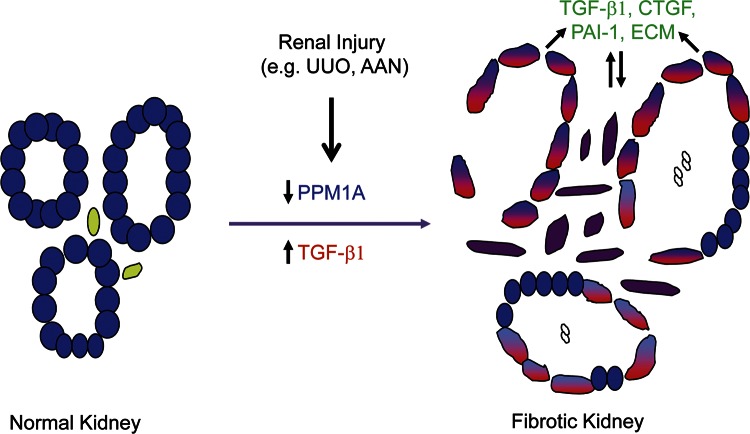

This study identifies PPM1A as a novel repressor of the SMAD3 pathway in renal fibrosis but also demonstrates that decreased PPM1A expression in kidney injury promotes maladaptive repair, highlighted by epithelial growth arrest, dedifferentiation, fibrotic factor secretion, and fibroblast proliferation (Fig. 10). These findings also implicate PPM1A as a novel antifibrotic target in the context of renal injury, and the restitution of PPM1A expression may represent a selective approach to reduce renal scarring as a complement to broad-spectrum TGF-β1 targeting modalities currently in clinical trials for treating a variety of fibrotic disorders.

Figure 10.

A model for PPM1A involvement in renal fibrosis. PPM1A expression (blue) is readily evident in differentiated renal tubules. Kidney injury (e.g., induced in response to AA or UUO) is accompanied by a progressive reduction (blue + red) of PPM1A in the tubular and interstitial regions, with increases in tissue TGF-β1 levels (red). Prolonged PPM1A silencing promotes secretion of fibrotic factors PAI-1, CTGF, and extracellular matrix (ECM) molecules, such as fibronectin and collagen, increasing cellular plasticity and cell-cycle arrest in epithelial cells while promoting fibroblast proliferation via SMAD3 dependent mechanisms. PPM1A loss-orchestrated maladaptive repair response is further aggravated in the presence of TGF-β1 up-regulation, a prominent feature of CKD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Charlotte Graver Foundation, the Friedman Cancer Research Foundation, and the U.S. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grant GM057242 (to P.J.H.). R.G. was previously employed (2008–2009 by, performs contract research for, and receives reagents for CTGF-related research from FibroGen.

Glossary

- AA

aristolochic acid

- AAN

aristolochic acid nephropathy

- BMP-6/7

bone morphogenic protein-6/7

- CKD

chronic kidney disease

- CTGF

connective tissue growth factor

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- HK-2

human kidney 2

- NRK-49F

normal rat kidney-49 fibroblast

- PAI-1

plasminogen activator inhibitor-1

- PPM1A

protein phosphatase magnesium-dependent 1A

- PTEN

phosphate tensin homolog on chromosome 10

- shRNA

short hairpin RNA

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- Ski

Sloan Kettering Institute proto-oncogene

- α-SMA

α-smooth muscle actin

- Sno

Ski-related novel gene

- UUO

unilateral ureteral obstruction

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R. Samarakoon and P. J. Higgins conceived and designed the experiments; R. Samarakoon, A. Rehfuss, N. S. Khakoo, L. L. Falke, A. D. Dobberfuhl, S. Helo, and J. M. Overstreet performed experiments and performed data analysis; R. Goldschmeding contributed key reagents and materials; R. Samarakoon and P. J. Higgins wrote the paper; and all authors agreed on the manuscript prior to submission.

REFERENCES

- 1.Friedman S. L., Sheppard D., Duffield J. S., Violette S. (2013) Therapy for fibrotic diseases: nearing the starting line. Sci. Transl. Med. 5:167sr [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jha V., Garcia-Garcia G., Iseki K., Li Z., Naicker S., Plattner B., Saran R., Wang A. Y., Yang C. W. (2013) Chronic kidney disease: global dimension and perspectives. Lancet 382, 260–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perico N., Remuzzi G. (2012) Chronic kidney disease: a research and public health priority. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 27, iii19–iii26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Couser W. G., Remuzzi G., Mendis S., Tonelli M. (2011) The contribution of chronic kidney disease to the global burden of major noncommunicable diseases. Kidney Int. 80, 1258–1270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang L., Humphreys B. D., Bonventre J. V. (2011) Pathophysiology of acute kidney injury to chronic kidney disease: maladaptive repair. Contrib. Nephrol. 174, 149–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strutz F., Neilson E. G. (2003) New insights into mechanisms of fibrosis in immune renal injury. Springer Semin. Immunopathol. 24, 459–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boor P., Ostendorf T., Floege J. (2010) Renal fibrosis: novel insights into mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 6, 643–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duffield J. S., Lupher M., Thannickal V. J., Wynn T. A. (2013) Host responses in tissue repair and fibrosis. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 8, 241–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loeffler I., Wolf G. (2014) Transforming growth factor-β and the progression of renal disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 29, i37–i45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samarakoon R., Overstreet J. M., Higgins P. J. (2013) TGF-β signaling in tissue fibrosis: redox controls, target genes and therapeutic opportunities. Cell. Signal. 25, 264–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samarakoon R., Overstreet J. M., Higgins S. P., Higgins P. J. (2012) TGF-β1 → SMAD/p53/USF2 → PAI-1 transcriptional axis in ureteral obstruction-induced renal fibrosis. Cell Tissue Res. 347, 117–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Massagué J. (2012) TGFβ signaling in context. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13, 616–630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samarakoon R., Dobberfuhl A. D., Cooley C., Overstreet J. M., Patel S., Goldschmeding R., Meldrum K. K., Higgins P. J. (2013) Induction of renal fibrotic genes by TGF-β1 requires EGFR activation, p53 and reactive oxygen species. Cell. Signal. 25, 2198–2209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Overstreet J. M., Samarakoon R., Gardona-Grau D., Goldschmeding R., Higgins P. J. (2015) Tumor suppressor ATM functions downstream of TGF-β1 in orchestrating pro-fibrotic responses. FASEB J. 29, 1258–1268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Overstreet J. M., Samarakoon R., Meldrum K. K., Higgins P. J. (2014) Redox control of p53 in the transcriptional regulation of TGF-β1 target genes through SMAD cooperativity. Cell. Signal. 26, 1427–1436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Itoh S., ten Dijke P. (2007) Negative regulation of TGF-beta receptor/Smad signal transduction. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 19, 176–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Samarakoon R., Higgins P. J. (2008) Integration of non-SMAD and SMAD signaling in TGF-β1-induced plasminogen activator inhibitor type-1 gene expression in vascular smooth muscle cells. Thromb. Haemost. 100, 976–983 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zeisberg M., Hanai J., Sugimoto H., Mammoto T., Charytan D., Strutz F., Kalluri R. (2003) BMP-7 counteracts TGF-beta1-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and reverses chronic renal injury. Nat. Med. 9, 964–968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dendooven A., van Oostrom O., van der Giezen D. M., Leeuwis J. W., Snijckers C., Joles J. A., Robertson E. J., Verhaar M. C., Nguyen T. Q., Goldschmeding R. (2011) Loss of endogenous bone morphogenetic protein-6 aggravates renal fibrosis. Am. J. Pathol. 178, 1069–1079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fukasawa H., Yamamoto T., Togawa A., Ohashi N., Fujigaki Y., Oda T., Uchida C., Kitagawa K., Hattori T., Suzuki S., Kitagawa M., Hishida A. (2004) Down-regulation of Smad7 expression by ubiquitin-dependent degradation contributes to renal fibrosis in obstructive nephropathy in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 8687–8692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang J., Zhang X., Li Y., Liu Y. (2003) Downregulation of Smad transcriptional corepressors SnoN and Ski in the fibrotic kidney: an amplification mechanism for TGF-beta1 signaling. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 14, 3167–3177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fukasawa H., Yamamoto T., Togawa A., Ohashi N., Fujigaki Y., Oda T., Uchida C., Kitagawa K., Hattori T., Suzuki S., Kitagawa M., Hishida A. (2006) Ubiquitin-dependent degradation of SnoN and Ski is increased in renal fibrosis induced by obstructive injury. Kidney Int. 69, 1733–1740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lan H. Y., Mu W., Tomita N., Huang X. R., Li J. H., Zhu H. J., Morishita R., Johnson R. J. (2003) Inhibition of renal fibrosis by gene transfer of inducible Smad7 using ultrasound-microbubble system in rat UUO model. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 14, 1535–1548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin X., Duan X., Liang Y. Y., Su Y., Wrighton K. H., Long J., Hu M., Davis C. M., Wang J., Brunicardi F. C., Shi Y., Chen Y. G., Meng A., Feng X. H. (2006) PPM1A functions as a Smad phosphatase to terminate TGFbeta signaling. Cell 125, 915–928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samarakoon R., Chitnis S. S., Higgins S. P., Higgins C. E., Krepinsky J. C., Higgins P. J. (2011) Redox-induced Src kinase and caveolin-1 signaling in TGF-β1-initiated SMAD2/3 activation and PAI-1 expression. PLoS One 6, e22896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Samarakoon R., Helo S., Dobberfuhl A. D., Khakoo N. S., Falke L., Overstreet J. M., Goldschmeding R., Higgins P. J. (2015) Loss of tumour suppressor PTEN expression in renal injury initiates SMAD3- and p53-dependent fibrotic responses. J. Pathol. 236, 421–432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chevalier R. L., Forbes M. S., Thornhill B. A. (2009) Ureteral obstruction as a model of renal interstitial fibrosis and obstructive nephropathy. Kidney Int. 75, 1145–1152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gökmen M. R., Cosyns J. P., Arlt V. M., Stiborová M., Phillips D. H., Schmeiser H. H., Simmonds M. S., Cook H. T., Vanherweghem J. L., Nortier J. L., Lord G. M. (2013) The epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of aristolochic acid nephropathy: a narrative review. Ann. Intern. Med. 158, 469–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang L., Besschetnova T. Y., Brooks C. R., Shah J. V., Bonventre J. V. (2010) Epithelial cell cycle arrest in G2/M mediates kidney fibrosis after injury. Nat. Med. 16, 535–543, 1p, 143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bu S., Kapanadze B., Hsu T., Trojanowska M. (2008) Opposite effects of dihydrosphingosine 1-phosphate and sphingosine 1-phosphate on transforming growth factor-beta/Smad signaling are mediated through the PTEN/PPM1A-dependent pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 19593–19602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Falke L. L., Goldschmeding R., Nguyen T. Q. (2014) A perspective on anti-CCN2 therapy for chronic kidney disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 29, i30–i37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou L., Fu P., Huang X. R., Liu F., Chung A. C., Lai K. N., Lan H. Y. (2010) Mechanism of chronic aristolochic acid nephropathy: role of Smad3. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 298, F1006–F1017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dvashi Z., Sar Shalom H., Shohat M., Ben-Meir D., Ferber S., Satchi-Fainaro R., Ashery-Padan R., Rosner M., Solomon A. S., Lavi S. (2014) Protein phosphatase magnesium dependent 1A governs the wound healing-inflammation-angiogenesis cross talk on injury. Am. J. Pathol. 184, 2936–2950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang X., Teng Y., Hou N., Fan X., Cheng X., Li J., Wang L., Wang Y., Wu X., Yang X. (2011) Delayed re-epithelialization in Ppm1a gene-deficient mice is mediated by enhanced activation of Smad2. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 42267–42273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]