Abstract

The development of individualized therapies has become the focus of current oncology research. Precision medicine has demonstrated great potential for bringing safe and effective drugs to those patients stricken with cancer, and is becoming a reality as more oncogenic drivers of malignancy are discovered. The discovery of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) mutations as a driving mutation in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and the subsequent success of the tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) have led the way for NSCLC to be at the forefront of biomarker-based drug development. However, this direction was not always so clear, and this article describes the lessons learned in targeted therapy development from EGFR in NSCLC.

Keywords: EGFR, NSCLC, Lung Cancer

Introduction

Advances in the understanding of the molecular pathogenesis underlying tumor development have begun to shift the field of oncology away from a “one size fits all” treatment paradigm. The discovery of oncogenic drivers has led to the development of targeted therapies that are more selective against the tumor cell. One of the first malignancies in which the biomarker-driven approach was proven successful is chronic myeloid leukemia, or CML. While the Philadelphia (Ph) chromosome had been known to be a chromosomal marker of CML for years, it was not until Druker et al. observed that specifically targeting this translocation with imatinib could cause dramatic responses.1 This groundbreaking work was followed in the solid tumor realm by trastuzamab, which benefits patients with an activated HER2 pathway signaling.2 These successes generated significant interest in researching for new targets and precision drug development. The field of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is leading the way in development of targeted therapies, many of which are now available for use in practice or clinical trials. The discovery of the role of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor mutations (EGFRm) in NSCLC tumorigenesis and subsequent development of EGFRm-specific tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) is an excellent example of personalized therapy. Consequently, extensive work detailing the genomic landscape of NSCLC and its effect on treatment and outcomes has been completed, such as published in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and the Lung Cancer Mutation Consortium (LCMC).3, 4 However, along the path from EGFRm discovery to TKI approval, many lessons were learned which can help guide future biomarker research and development, not just in NSCLC, but in all malignancies.

Lesson 1: The target should be critical to the sustenance of the cancer cell

Currently, it has been proved that EGFRm is driving a subset of NSCLC and that targeting this oncogene with an EGFRm TKI such as erlotinib, gefitinib, or afatanib is the most effective treatment strategy. However, as with many groundbreaking developments, this path was not always so clear. EGFR is a glycoprotein that plays a complicated role in signal transduction and cellular processes. It has been shown to be important in tumorigenesis for many years.5 Significant research was performed examining the biological relevance of EGFR in NSCLC, following initial observations of receptor overexpression and a corresponding association with poor prognosis.6, 7 For these reasons, targeting EGFR became an area of interest in NSCLC drug development. The oral medications erlotinib and gefitinib were designed to target the EGFR pathway as reversible small molecule inhibitors of the tyrosine kinase domain of the receptor to prevent downstream signaling. Preclinical data demonstrated anti-tumor activity in cell lines and xenograft models that were dependent on EGFR activity.8

Based on promising early phase clinical trial results,9, 10 the EGFR TKI erlotinib was studied in a phase III trial of metastatic NSCLC patients who had progressed on standard-of-care chemotherapy (BR-21). The patients were randomized to erlotinib versus placebo following progression after 1 or 2 chemotherapy regimens, but were unselected in regards to EGFR status. The study recruited 731 patients, with 488 receiving erlotinib and 243 placebo. Erlotinib was tolerated well, with the most common adverse events being rash and diarrhea. In terms of outcomes, erlotinib had a 9% response rate and a 2.2 month median progression free survival (PFS) vs. 1.8 months for placebo (p<0.001). The median overall survival was 6.7 months and 4.7 months (p<0.001) for erlotinib and placebo, respectively.11 Based on this significant, although clinically modest, overall survival benefit, erlotinib was approved by the FDA for NSCLC in 2004. The authors noted that Asian ethnicity, women, patients with adenocarcinoma, lifetime nonsmokers, and tumors that expressed EGFR in ≥ 10% of cells had improved response rates, although EGFR overexpression was not consistently found to be a predictive biomarker to TKI therapy.12 It was clear from the study that while there is a survival advantage in treating with erlotinib in an unselected NSCLC population, there was clearly a subgroup that benefitted more from TKI treatment.

Several groups hypothesized that the patients that responded well to erlotinib or gefitinib had an intrinsic difference within their EGFR receptor. In one landmark study, the researchers obtained tumor samples from patients that had responded to TKI therapy and sequenced the EGFR tyrosine kinase binding domain. They found exon 19 in-frame deletions, the exon 21 point mutation L858R, and less frequently exon 18 point mutations.13–15 In fact, when these studies are examined as a whole, of 31 patients that responded to erlotinib or gefitinib, 25 had one of these listed mutations.14

With increasing evidence linking EGFRm mutations to response to EGFR TKI therapy, the authors of BR-21 conducted post-hoc genomic analysis and correlated them with clinical outcomes. Unfortunately, while they found a trend towards increase responses, no increased survival was seen in patients with EGFRm treated with erlotinib (p=0.65).16 In retrospect, this negative result might have been due to small numbers of patients, suboptimal quality of specimens, and that mutation detection techniques were still evolving. While this negative analysis did delay the widespread acceptance of EGFRm as a predictive biomarker, the body of evidence was growing and subsequent clinical trials examined the use of EGFR TKI on selected populations. This shift led to the pivotal studies that confirmed the use of biomarker-driven, targeted therapy use in the treatment of NSCLC.

The first large, randomized phase 3 trial of an EGFR TKI in a selected population was published in 2009, entitled the IPASS study. This study randomized East Asian, never- or former light-smokers with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma that had not received prior systemic therapy to either gefitinib or standard platinum-based chemotherapy. The main goal of this study was to compare the efficacy of EGFR inhibition to chemotherapy in a clinically enriched subset of patients likely to benefit from the former. While the trial did not select specifically for EGFRm status, it was enriched for EGFRm because of the clinical selection factors utilized.14, 17 Not only did the study demonstrate non-inferiority for gefitinib relative to chemotherapy, but also showed superiority with EGFR inhibition with a PFS hazard ratio (HR) of 0.74, p<0.001.

The investigators conducted a post-hoc analysis of tumor tissue for EGFR mutation and analyzed outcomes based on this. Patients with EGFRm had response rates of 71.2% when treated with gefitinib vs. 47.3% with chemotherapy, with a HR for progression of 0.48, P<0.001.18 In fact, for patients with wild type EGFR, the outcomes were inferior with gefitinib compared to chemotherapy. This established the fact that molecular selection was superior to clinical selection with regards to utilization of EGFR inhibitors in advanced NSCLC.

The findings from the IPASS study led to a number of randomized studies that compared EGFR inhibition to chemotherapy, specifically in patients with EGFRm (Table 1). The EURTAC trial enrolled 172 patients with EGFRm NSCLC across 42 institutions in Europe and compared erlotinib to platinum-based chemotherapy as first line therapy for metastatic disease. In this selected population, erlotinib had superior outcomes to standard chemotherapy. Response rate was 64% vs. 18%, and median PFS was 9.7 months vs. 5.2 months respectively for erlotinib and chemotherapy. There was no difference in overall survival, likely due to crossover from control group to erlotinib upon disease progression.19 Similar results were seen in two studies conducted in Japan that compared gefitinib with chemotherapy in a treatment naïve, EGFRm NSCLC populations. In these trials, median PFS for gefitinib was 9.2–10.8 months vs. 5.4–6.3 months for chemotherapy.20, 21 Finally, the second generation EGFR TKI afatanib was also proven superior to first-line chemotherapy in patients with EGFRm NSCLC, with a median PFS of 13.6 months vs. 6.9 months.22 These studies led to the adoption of EGFR TKIs as the preferred standard of care in first-line therapy of patients with EGFRm NSCLC.

Table 1.

Randomized phase III trials comparing chemotherapy with 1st and 2nd generation EGFR TKIs

| Regimen | ORR | Median PFS | Median OS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Year | TKI (N) | Chemo (N) | TKI (%) | Chemo (%) | TKI (months) | Chemo (months) | TKI (months) | Chemo (months) |

| Mok et al.18, 54 | 2009 | Gefitinib(132) | Carbo-Taxol (129) | 71.2 | 47.3 | 9.5 | 6.3 | 21.6 | 21.9 |

| Mitsudomi et al.21, 55 | 2010 | Gefitinib (86) | Cis-Taxotere (86) | 62.1 | 32.2 | 9.2 | 6.3 | 34.8 | 37.3 |

| Maemondo et al.20 | 2010 | Gefitinib (114) | Carbo-Taxol (114) | 73.7 | 30.7 | 10.8 | 5.4 | 30.5 | 23.6 |

| Zhou et al.56, 57 | 2011 | Erlotinib (83) | Carbo-Gem (82) | 83 | 36 | 13.1 | 4.6 | 22.7 | 28.9 |

| Rosell et al.19 | 2012 | Erlotinib (86) | Platinum Doublet (87) | 64 | 18 | 9.7 | 5.2 | 19.3 | 19.5 |

| Sequist et al.22, 58 | 2013 | Afatanib (230) | Cis-Pem (115) | 56 | 23 | 11.1 | 6.9 | 28.2 | 28.2 |

| Wu et al.58, 59 | 2014 | Afatanib (242) | Cis-Gem (122) | 66.9 | 23 | 11 | 5.6 | 23.1 | 23.5 |

Overall, this pathway to a biomarker-driven treatment has helped teach the importance of choosing the right biomarker and the appropriate population in the era of targeted therapy. In fact, a recent meta-analysis that compared EGFR TKIs to chemotherapy in patients with EGFR wt lung tumors demonstrated superiority for chemotherapy. A total 11 trials with 1605 patients were included in the analysis. For this population, chemotherapy was associated with an improved PFS over EGFR TKIs (HR for TKI, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.10–1.81).23

Lesson 2: Resistance inevitably develops

Despite response rates of over 70%, patients with EGFR driving mutations on TKI therapy eventually progress. The median time to progression has ranged from approximately 10–13 months.18, 19, 22 Unfortunately, resistance to targeted therapy is not a problem unique to this population. Similar patterns of resistance have been seen with imatinib use in CML and crizotinib in ALK+ NSCLC.24, 25 However, secondary to the dedication of researchers and the generosity of patients in consenting to biopsies post-TKI progression, research into the resistance to EGFRm TKIs has provided valuable insights. The most common resistance mechanism seen in EGFRm patients is the development of a secondary point mutation in the EGFR active domain, substituting a bulky methionine amino acid for threonine (T790M) and inhibiting EGFR TKI binding, similar to that of the T315I mutation seen in CML.25 It was first described as a case report in 2005 in a 71 yo former smoker with an EGFR exon 19 deletion positive advanced NSCLC. The patient achieved a complete response on gefitinib, but progressed after 2 years. A repeat tumor biopsy was performed and the EGFR exons 18–21 were sequenced. While the original del19 mutation was still present, a new exon 20 T790M mutation was also found. Introduction of the T790M into EGFRm cell lines was found to confer resistance to gefitinib.26 A subsequent study found that in 2 of 5 patients with EGFRm NSCLC that had progressed on erlotinib or gefitinib harbored the T790M mutation, which again was confirmed to be resistant to EGFR TKI in in-vitro studies. However, 3 of the patients did not have the T790M mutation, indicating that other forms of resistant were likely to be present.27 Currently, the T790M mutation estimated to represent 50–60% of resistance to the first and second generation EGFRm TKIs.28 Signaling pathways that bypass the EGFRm TKI blockade have also been shown to play an integral part in resistance.

In recent years, c-MET has been shown to be a potential oncogenic driver of NSCLC, and efforts are currently underway to target c-Met amplification in a targeted fashion in NSCLC.29 c-MET, coded for by the oncogene MET, is a receptor tyrosine kinase that play an important role in a variety of cell processes, including cell invasion, growth and angiogenesis.30 c-MET has also been shown to play a role in evading TKI inhibition of EGFRm NSCLC. Engelman et al. demonstrated that one mechanism by which EGFRm leads to NSCLC is by activation of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt signaling through ERBB3 (HER3).31 They hypothesized that in EGFRm TKI resistant NSCLC, a secondary pathway caused activation of ERBB3 and continued tumorigenesis. In gefitinib-resistant cell lines, this was due to amplification of MET, leading to EGFRm independent ERBB3 signaling. When MET amplification was studied in TKI-resistant NSCLC biopsies, it was observed in 4/18 (22%) samples.32 This finding was soon confirmed with MET amplification in 9/43 (21%) of resistant patients, although interestingly was commonly seen in conjunction with the T790M mutation.32

Following this work, Sequist et al. published a case series examining resistance to the EGFR inhibitors. Biopsies were obtained from 37 patients with EGFRm NSCLC post-progression on TKI therapy. The tumor samples were examined by multiplex SNaPshot genomic sequencing, fluorescent in-situ hybridization (FISH) testing, and pathological evaluation. All patients retained their original EGFRm. Of the 37 patients, 18 (49%) were found to have the T790M mutation, which included 3 patients who concomitantly developed EGFR gene amplification, and 2 (5%) had MET amplification by FISH. For the first time, PIK3CA mutations were seen as a resistance mechanism in 2 (5%) of patients. Additionally, phenotypically, 2 (5%) patients were noted to have an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Perhaps most unexpected, in 5 (14%) patients, a full histological change was noted from adenocarcinoma to small cell lung cancer (SCLC) while retaining their original EGFRm.28 This finding was seen in another cohort of 106 biopsies of TKI resistant tumors, 2 of which were found to be of a SCLC phenotype, and 1 was a high-grade neuroendocrine tumor.33

Lesson 3. Resistance can be overcome by mechanism-based drug discovery

The best approach to treating EGFRm NSCLC patients that have progressed on first or second line EGFR TKI therapy remains under active research. Nonetheless, significant progress has been made and lessons learned along the path. For example, in the treatment of EGFR wt NSCLC, when progression is noted on radiographic imaging, typically the treatment is discontinued and a subsequent line of therapy is adopted. However, this paradigm is not as clearly applicable in EGFRm targeted therapy. Currently, EGFRm NSCLC patients who have asymptomatic, mild radiographic progression are often continued on their TKI therapy. Additionally, if there is progression in the CNS (of which the TKIs have relative low penetration) or with oligometastatic disease, local therapy such as radiation is often utilized and the TKI is continued for systemic control. In one study, patients were enrolled upon progression on either gefitinib or erlotinib, and then had their TKI discontinued. Of 10 patients that had their TKI held, 7 developed worsening of symptoms such as increased dyspnea, fatigue and pleural effusions. The patients then had their TKI restarted and all had clinical improvement or stabilization.34 In a separate retrospective study, 18 patients who progressed with non-CNS oligometastatic disease on TKI therapy and were treated with local therapy were included. Of these patients, 85% restarted TKI therapy within one month of local therapy and the median PFS after treatment re-initiation was 10 months, with the average time to a change in systemic therapy of 22 months.35 In patients that develop CNS progression, again retrospective studies support the use of local therapy to the brain followed by continuation of TKI therapy.36, 37 While local therapy and continued TKI for asymptomatic, oligoprogressive disease has become an accepted treatment standard, these non-randomized retrospective reports have to be interpreted with caution.

The recently reported IMPRESS trial has clearly demonstrated that the previously used practice of continuing TKI after progression along with subsequent chemotherapy is not beneficial. This study enrolled an Asian and European population with advanced EGFRm NSCLC that were chemotherapy naïve, initially achieved a response to first-line gefitinib and then progressed within 4 weeks prior to accrual. Patients were then randomized to cisplatin and pemetrexed with gefitinib, or the same chemotherapy regimen with placebo. From 71 centers, 265 patients were randomized and the cohorts were well balanced for baseline characteristics. They found no difference for gefitinib vs. placebo in terms of ORR (31.6% vs. 34.1%, p=0.76), disease control rate (84.2% vs. 78.8%, p=0.308), or PFS (5.4m vs. 5.4m, p=0.273), respectively. In fact, the investigators found that the OS was worse in patients who continued gefitinib (14.8m vs. 17.2m, p=0.029).38 Based on this definitive study, it is no longer necessary to continue a TKI with subsequent lines of therapy beyond progression. Additionally, the unsuccessful attempts to use various drugs, such as HDAC, c-MET, and IGF-1R inhibitors, in combination with EGFR TKIs to improve efficacy in an unselected population highlights the importance of utilizing predictive biomarkers in trial design.39–41 Interestingly, however, the combination of erlotinib with bevacizumab in an EGFRm frontline population appeared efficacious in phase II randomized trial vs. erlotinib alone, with a median PFS of 16 vs. 9.7 months, respectively.42

Currently, 3rd generation EGFR TKIs are in clinical trials and have demonstrated significant activity in patients that have progressed on erlotinib, gefitinib, or afatanib. The unique aspect of these next generation agents’ development is that they were designed to target both the activating EGFRm, as well as the most common resistance mechanism, the T790M mutation, while relatively sparing the EGFR wt receptor. The drugs that are currently furthest along in development are AZD9291 (AstraZeneca, Macclesfield, United Kingdom) and Rociletinib (CO-1686, Clovis Oncology, Boulder, CO). Both targeted therapies have shown impressive results in preclinical models.43, 44 The results of the completed phase I dose escalation and expansion cohort AZD9291 have recently been updated. The patients were heavily pretreated, 38% male and mostly Asian race. A total of 253 EGFRm patients that progressed on 1st or 2nd generation TKIs patients were recruited to the study, out of whom 222 were included in the expansion cohort. The presence of T790M mutation was confirmed in 138 patients. Outcomes with AZD9291 were impressive, but were clearly better in the patients with the T790M resistance mutation. For T790M positive patients, RR was 61% with a clinical benefit rate (CBR) of 95% and, a preliminary median PFS of 9.6 months, while for T790M negative patients, RR was 21%, CBR was 61% and median PFS 2.8 months.45 Adverse events were similar, although less frequent, than the 1st generation TKIs.

Rociletinib was also developed to target T790M and has shown promise. The early efficacy data from the expansion cohort of a phase I/II study of EGFRm patients that had progressed on first line TKIs were reported recently. For the expansion cohort, the patients had to be T790M positive. The response rate for the forty patients that were T790M positive was 58%. The median PFS had not been reached at the time of the report. Interestingly, hyperglycemia was the most common adverse event, presumably related to inhibition of the IGF-1R pathway.46 Clinical trials are progressing rapidly for these agents, as both drugs are being compared to chemotherapy in patients with acquired resistance. Other 3rd generation EGFRm TKIs are being examined, but are early in development (Table 2). It will be important moving forward to obtain biopsies from patients on a 3rd generation TKI upon progression in order to determine the resistance mechanisms. Furthermore, given the efficacy of these 3rd generation TKIs, they are currently being compared to the 1st generation EGFR TKIs in randomized trials of a treatment-naïve population.47, 48

Table 2.

3rd generation EGFR TKIs in development

| T790M Specific EGFRm TKI | Current Clinical Status | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Rociletinib | Phase I and II, III soon | Breakthrough Therapy designation |

| AZD 9291 | Phase II and III | Breakthrough Therapy designation |

| EGF 816 | Phase I/II | |

| Astellas 8273 | Phase I/II | |

| AZD 3759 | Phase I | |

| HM 61713 | Phase I |

These results hold promise for EGFRm NSCLC patients who progress on EGFR TKIs. However, there is significant room for improvement in patients who are T790M negative. Additionally, there is evidence that tumor heterogeneity for EGFR resistance exists within EGFRm NSCLC. In one study, 42 patients that had multiple biopsies post-TKI progression were reviewed. The mechanism of resistance changed between individual patient samples in 20/42 patients, with 10 patients either gaining or losing the T790M mutation while the original driver EGFRm was preserved.49

One active area of research to improve the treatment after resistance formation is combination therapy, which holds promise for the T790M negative population. Rizvi et al. recently reported data examining the anti-PD1 antibody nivolumab in combination with erlotinib in patients with advanced EGFRm NSCLC. Twenty out of 21 patients had progressed on prior therapy with erlotinib. The ORR was 19%, and 45% had stable disease as best response. The median PFS was 29.4 weeks and median overall survival had not been reached.50 While early, PD-1/PDL-1 inhibition in addition to EGFR TKI might hold promise for patients who progress on EGFR TKIs. Similarly, afatinib and cetuximab were studied in the EGFR resistant setting in a phase Ib clinical trial of 126 patients. There was a modest response to treatment with an ORR of 29% and median PFS of 4.7 on the combination; however, there was a significant skin toxicity, with 46% grade 3/4, making the clinical use of this regimen unclear.51 However, the work that has been done in exploring the best ways to approach EGFR TKI resistance should provide guidance to the development of future targeted therapies across tumor types.

Lesson 4: Achieving cure with EGFR TKI is still elusive

Finally, a key issue relates to the use of targeted therapies in early stage disease to improve the cure rate. Despite their impressive efficacy in advanced stage patients, targeted therapies to date are not curative treatments.

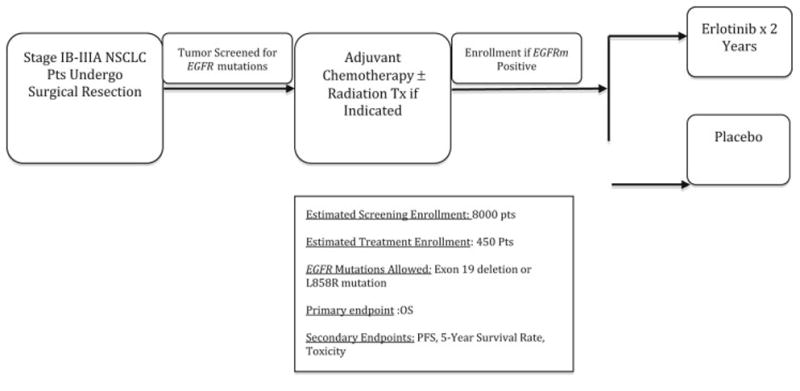

This was established by the results of the RADIANT trial, a large, randomized phase III trial that compared adjuvant erlotinib to placebo for early stage (stage IB-IIIA) disease. Patients that were EGFR positive by IHC/FISH were included following surgical resection of their primary tumor. It is important to note that EGFRm was not used as the biomarker. For the 973 patients randomized, there was no difference in disease free survival or overall survival between erlotinib and placebo. However, 161 patients were EGFRm positive, and in subset analysis, median disease-free survival was 46.4 months for erlotinib vs. 28.5 months for placebo in this patient population. The overall survival results are not mature, but the preliminary results do not demonstrate a robust difference.52 The ongoing ALCHEMIST trial is seeking to definitively answer this question, enrolling early stage EGFRm NSCLC patients who underwent surgery to either receive erlotinib or placebo for up to a two-year period with overall survival as the definitive endpoint (Figure 1).53

Figure 1.

ALCHEMIST study schema

Conclusions

The field of oncology has entered an age of biomarker-driven, targeted therapy, and EGFR mutated NSCLC has been at the forefront. Innovative research and drug design have followed the discovery of this driving mutation. However, lessons learned along the way will help guide future biomarker development. The developmental history of EGFR inhibitors has not only influenced subsequent research in lung cancer, but has extended to all solid organ malignancies. Evaluation of predictive biomarkers is now an essential part of even early phase studies. Many clinical trials are utilizing extension cohorts of phase 1 studies to evaluate efficacy in patient subsets based on putative biomarkers. It also changed the perception of lung cancer as one disease; in fact, there are many ongoing studies for evaluating agents in various subsets based on driver mutations. We have also learned that even the most targeted agent does not result in complete control/cure of the disease, since resistance develops in all patients. The use of novel combination regimens to avoid resistance might pave the way to achieve durable benefits for majority of the patients with driver mutations. The promising results with immune checkpoint inhibitors provide another avenue to improve the efficacy of targeted agents in NSCLC. It is also important to conduct tumor biopsy at the time of clinical resistance to understand the specific mechanism, since this knowledge could guide the next therapeutic choice. Thankfully, the rapid emergence of technology to conduct molecular studies in cell-free DNA obtained in peripheral blood (liquid biopsy) may obviate the need for multiple tumor biopsies. In conclusion, understanding the molecular characteristics of the tumor at every step of the way is likely to achieve the best possible therapeutic outcomes for patients with driver mutations.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Druker BJ, Talpaz M, Resta DJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of a specific inhibitor of the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase in chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1031–1037. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104053441401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, et al. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:783–792. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103153441101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;511:543–550. doi: 10.1038/nature13385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kris MG, Johnson BE, Berry LD, et al. Using multiplexed assays of oncogenic drivers in lung cancers to select targeted drugs. Jama. 2014;311:1998–2006. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shin DM, Ro JY, Hong WK, Hittelman WN. Dysregulation of epidermal growth factor receptor expression in premalignant lesions during head and neck tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3153–3159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brabender J, Danenberg KD, Metzger R, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor and HER2-neu mRNA expression in non-small cell lung cancer Is correlated with survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:1850–1855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rusch V, Klimstra D, Venkatraman E, Pisters PW, Langenfeld J, Dmitrovsky E. Overexpression of the epidermal growth factor receptor and its ligand transforming growth factor alpha is frequent in resectable non-small cell lung cancer but does not predict tumor progression. Clin Cancer Res. 1997;3:515–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moyer JD, Barbacci EG, Iwata KK, et al. Induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest by CP-358,774, an inhibitor of epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4838–4848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fukuoka M, Yano S, Giaccone G, et al. Multi-institutional randomized phase II trial of gefitinib for previously treated patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (The IDEAL 1 Trial) [corrected] J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2237–2246. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kris MG, Natale RB, Herbst RS, et al. Efficacy of gefitinib, an inhibitor of the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase, in symptomatic patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a randomized trial. Jama. 2003;290:2149–2158. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.16.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:123–132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perez-Soler R, Chachoua A, Hammond LA, et al. Determinants of tumor response and survival with erlotinib in patients with non--small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3238–3247. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paez JG, Janne PA, Lee JC, et al. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science. 2004;304:1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.1099314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pao W, Miller V, Zakowski M, et al. EGF receptor gene mutations are common in lung cancers from “never smokers” and are associated with sensitivity of tumors to gefitinib and erlotinib. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:13306–13311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405220101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2129–2139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsao MS, Sakurada A, Cutz JC, et al. Erlotinib in lung cancer - molecular and clinical predictors of outcome. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:133–144. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shigematsu H, Lin L, Takahashi T, et al. Clinical and biological features associated with epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations in lung cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:339–346. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:947–957. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R, et al. Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:239–246. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70393-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K, et al. Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2380–2388. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y, et al. Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): an open label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:121–128. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70364-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sequist LV, Yang JC, Yamamoto N, et al. Phase III study of afatinib or cisplatin plus pemetrexed in patients with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3327–3334. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.2806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee JK, Hahn S, Kim DW, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors vs conventional chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer harboring wild-type epidermal growth factor receptor: a meta-analysis. Jama. 2014;311:1430–1437. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi YL, Soda M, Yamashita Y, et al. EML4-ALK mutations in lung cancer that confer resistance to ALK inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1734–1739. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hochhaus A, Kreil S, Corbin AS, et al. Molecular and chromosomal mechanisms of resistance to imatinib (STI571) therapy. Leukemia. 2002;16:2190–2196. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kobayashi S, Boggon TJ, Dayaram T, et al. EGFR mutation and resistance of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:786–792. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pao W, Miller VA, Politi KA, et al. Acquired resistance of lung adenocarcinomas to gefitinib or erlotinib is associated with a second mutation in the EGFR kinase domain. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e73. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sequist LV, Waltman BA, Dias-Santagata D, et al. Genotypic and histological evolution of lung cancers acquiring resistance to EGFR inhibitors. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:75ra26. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Camidge DR, Ou S-H, Shapiro G, et al. ASCO. Chicago, USA: 2014. Efficacy and safety of crizotinib in patients with advanced c-MET-amplified non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sierra JR, Tsao MS. c-MET as a potential therapeutic target and biomarker in cancer. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2011;3:S21–35. doi: 10.1177/1758834011422557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Engelman JA, Janne PA, Mermel C, et al. ErbB-3 mediates phosphoinositide 3-kinase activity in gefitinib-sensitive non-small cell lung cancer cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:3788–3793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409773102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Engelman JA, Zejnullahu K, Mitsudomi T, et al. MET amplification leads to gefitinib resistance in lung cancer by activating ERBB3 signaling. Science. 2007;316:1039–1043. doi: 10.1126/science.1141478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arcila ME, Oxnard GR, Nafa K, et al. Rebiopsy of lung cancer patients with acquired resistance to EGFR inhibitors and enhanced detection of the T790M mutation using a locked nucleic acid-based assay. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1169–1180. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riely GJ, Kris MG, Zhao B, et al. Prospective assessment of discontinuation and reinitiation of erlotinib or gefitinib in patients with acquired resistance to erlotinib or gefitinib followed by the addition of everolimus. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5150–5155. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu HA, Sima CS, Huang J, et al. Local therapy with continued EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy as a treatment strategy in EGFR-mutant advanced lung cancers that have developed acquired resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:346–351. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31827e1f83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weickhardt AJ, Scheier B, Burke JM, et al. Local ablative therapy of oligoprogressive disease prolongs disease control by tyrosine kinase inhibitors in oncogene-addicted non-small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:1807–1814. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182745948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shukuya T, Takahashi T, Naito T, et al. Continuous EGFR-TKI administration following radiotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer patients with isolated CNS failure. Lung Cancer. 2011;74:457–461. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mok T, Wu YL, Nakagawa K, et al. ESMO. Madrid, Spain: 2014. Continuation of Gefitinib Plus Pemetrexed/Cisplatin of No Clinical Benefit in NSCLC Patients with Acquired Resistance to Gefitinib. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reguart N, Rosell R, Cardenal F, et al. Phase I/II trial of vorinostat (SAHA) and erlotinib for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations after erlotinib progression. Lung Cancer. 2014;84:161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ramalingam SS, Spigel DR, Chen D, et al. Randomized phase II study of erlotinib in combination with placebo or R1507, a monoclonal antibody to insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor, for advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4574–4580. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.6799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sequist LV, von Pawel J, Garmey EG, et al. Randomized phase II study of erlotinib plus tivantinib versus erlotinib plus placebo in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3307–3315. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.0570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seto T, Kato T, Nishio M, et al. Erlotinib alone or with bevacizumab as first-line therapy in patients with advanced non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring EGFR mutations (JO25567): an open-label, randomised, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:1236–1244. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70381-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walter AO, Sjin RT, Haringsma HJ, et al. Discovery of a mutant-selective covalent inhibitor of EGFR that overcomes T790M-mediated resistance in NSCLC. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:1404–1415. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cross DA, Ashton SE, Ghiorghiu S, et al. AZD9291, an irreversible EGFR TKI, overcomes T790M-mediated resistance to EGFR inhibitors in lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2014 doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang CH, Kim DW, Plachard D, et al. European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Madrid, Spain: 2014. Updated safety and efficacy from a Phase I study of AZD9291 in patients with EGFR-TKI-resistant non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sequist LV, Soria J-C, Gadgeel S, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology. Chicago, USA: 2014. First-in-human evaluation of CO-1686, an irreversible, highly selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor of mutations of EGFR (activating and T790M) [Google Scholar]

- 47.FLAURA. [accessed Feb 27, 2015]; Available from URL: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02296125?term=flaura&rank=1.

- 48. [accessed Feb 27, 2015];Rociletinib. Available from URL: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02186301?term=rociletinib&rank=3.

- 49.Piotrowska Z, Niederst M, Mino-Kenudson M, et al. ASCO. Vol. 2014. Chicago: 2014. Variation in mechanisms of acquired resistance (AR) among EGFR-mutant NSCLC patients with more than one post-resistant biopsy. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rizvi NA, Chow L, Borghaei H, et al. ASCO. Chicago, USA: 2014. Safety and response with nivolumab (anti-PD-1; BMS-936558, ONO-4538) plus erlotinib in patients (pts) with epidermal growth factor receptor mutant (EGFR MT) advanced NSCLC. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Janjigian YY, Smit EF, Groen HJ, et al. Dual Inhibition of EGFR with Afatinib and Cetuximab in Kinase Inhibitor-Resistant EGFR-Mutant Lung Cancer with and without T790M Mutations. Cancer Discov. 2014;4:1036–1045. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kelly K, Altorki N, Eberhardt WE, et al. ASCO. Chicago, USA: 2014. A randomized, double-blind phase 3 trial of adjuvant erlotinib (E) versus placebo (P) following complete tumor resection with or without adjuvant chemotherapy in patients (pts) with stage IB-IIIA EGFR positive (IHC/FISH) non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): RADIANT results. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Available from URL: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02193282.

- 54.Fukuoka M, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, et al. Biomarker analyses and final overall survival results from a phase III, randomized, open-label, first-line study of gefitinib versus carboplatin/paclitaxel in clinically selected patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer in Asia (IPASS) J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2866–2874. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.4235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yoshioka H, Mitsudomi T, Morita S, et al. ASCO. Chicago, USA: 2014. Final overall survival results of WJTOG 3405, a randomized phase 3 trial comparing gefitinib (G) with cisplatin plus docetaxel (CD) as the first-line treatment for patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhou C, Wu YL, Chen G, et al. Erlotinib versus chemotherapy as first-line treatment for patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (OPTIMAL, CTONG-0802): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:735–742. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70184-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhou C, Wu YL, Liu X, et al. ASCO. Chicago, USA: 2012. Overall survival (OS) results from OPTIMAL (CTONG0802), a phase III trial of erlotinib (E) versus carboplatin plus gemcitabine (GC) as first-line treatment for Chinese patients with EGFR mutation-positive advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang JC, Wu YL, Schuler M, et al. Afatinib versus cisplatin-based chemotherapy for EGFR mutation-positive lung adenocarcinoma (LUX-Lung 3 and LUX-Lung 6): analysis of overall survival data from two randomised, phase 3 trials. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:141–151. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71173-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu YL, Zhou C, Hu CP, et al. Afatinib versus cisplatin plus gemcitabine for first-line treatment of Asian patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring EGFR mutations (LUX-Lung 6): an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:213–222. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70604-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]