Abstract

A learning plan is a tool to guide the development of knowledge, skills and professional attitudes required for practice. A learning plan is an ideal tool for both supervisors and mentors to guide the process of teaching and learning a medical ultrasound examination. A good learning plan will state the learning goal, identify the learning activities and resources needed to achieve this goal, and highlight the outcome measures, which when achieved indicate the goal has been accomplished. A skill acquisition plan provides a framework for task acquisition and skill stratification; and is an extension of the application of the student learning plan. One unique feature of a skill acquisition plan is it requires the tutor to first undertake a task analysis. The task steps are progressively learnt in sequence, termed scaffolding. The skills to develop and use a learning or skill acquisition plan are also learnt, but are an integral component to the ultrasound tutors skill set. This paper will provide an outline of how to use and apply a learning and skill acquisition plan. We will review how these tools can be personalised to each student and skill teaching environment.

Keywords: learning plan, skill acquisition, SMART objectives, task deconstruction, ultrasound

Introduction

A learning plan is a tool that guides the development of knowledge, skills and professional attitudes required for practice. A learning plan is an ideal tool for both supervisors and mentors to guide the process of teaching and learning to perform a medical ultrasound examination. A good learning plan will state the learning goal, identify the learning activities and resources beneficial to achieve the goal, and highlight the outcome measures, which when achieved indicate the goal has been accomplished. A professional practice learning plan is premised on adult learning principles. Adult learners are self‐directed, learn through experience, and require an understanding as to how and why the information is relevant to their immediate learning outcomes. 1 The benefits of using and applying adult learning theories to teaching events include improved learner commitment and better achievement of learning outcomes. 2 In the context of medical ultrasound, a learning plan is collaborative, centred on the student and outlines the pathway by which the goals can be achieved. This allows the student to be self‐directed and pace their own learning to achieve the requisite outcomes. The purpose of this paper is to outline what a learning plan is and how it can be used to define, document and target goal achievement in medical ultrasound imaging. We also provide examples of learning plans applied to acquisition of the skills needed in medical ultrasound imaging.

What is a learning plan?

A learning plan is an explicit and transparent document that itemises the measurable learning goal or objective, 3 identifies learning strategies and resources to develop the knowledge, skills or professional attitudes required for clinical practice, and specifies what it is the learner must know, do or apply in order to accomplish the goal. A clear and concise learning plan guides both learner and tutor through the required process to achieve the learning goal.

Knowledge of how to develop learning plans for your learners and apply a learning plan to your clinical environment is a useful skill for a supervisor or mentor to acquire. These skills when developed, allow the supervisor to determine if using a learning plan is the most appropriate tool for the educational context. To assist this decision making process, it is first necessary to have a good understanding of the curriculum required by any credentialing body to achieve certification. The knowledge, skills and professional attitudes required to achieve competence form the goal posts for your learners' achievements. The individual learning needs and goals that arise as a result of knowledge of curricular content, should underpin the activities and outcome measures recorded in an individualised learning plan.

Identifying the learning need

The first step when using a learning plan requires the learner or tutor to identify the learning need. This is an important step to ensure the learning need is required and refined, so the planned activities are relevant to the learning need, and the learning strategy and format is appropriate for the learners experience and context. 4 The learning need should be explicitly outlined and linked to learning objectives, assessment hurdles (university clinical assessment) such as credentialing or competency criteria, or a personal education objective. Alternatively, the learning need may be identified after discussion with the learner, viewing a log book, observing a skill performance or based on patient or professional practice feedback. Each of these scenarios require the tutor to ascertain what is the student's current level of knowledge or skill (prior learning) and what is the required level to achieve competence; a process also known as a gap analysis. 5 The learning need(s) are determined from this well‐thought‐through outcome disparity. After identifying a learning need, an action plan is constructed to work towards achieving the identified outcome or goal. 4 Learning plans should highlight and build upon a learner's prior learning. This is an important adult learning principle which both acknowledges and capitalises on historical experiences, knowledge and skills. 6

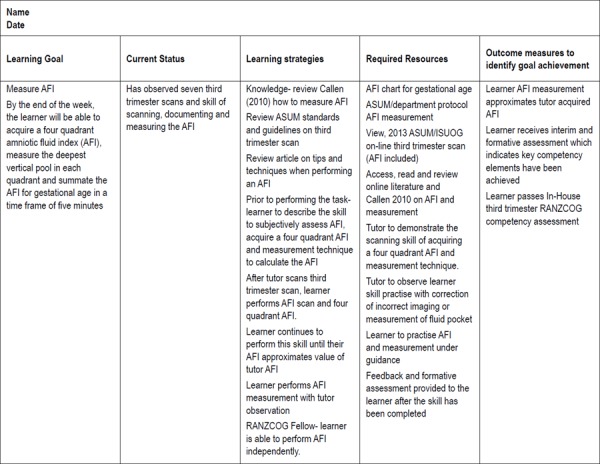

Figure 1 is an example of a learning plan which contains a learning need relevant to the learner's area of expertise and stage of learning. In this case, the learning need is to acquire, document and measure the amniotic fluid index (AFI) for an Obstetrics and Gynaecology (O&G) registrar, undertaking the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG) In‐Hospital clinical assessment of trainee competence. 7

Figure 1.

An example of a learning plan to achieve a learning need or goal (used with permission from ASUM).

Writing a learning objective

A learning need is a yet to be achieved dimension of knowledge, skill or attitude 4 required to exhibit safe practice. 8 After identifying the learning need, it should be restated as a learning objective or goal that becomes measurable. A learning objective is a written statement outlining the goal you wish the learner to achieve. Learning objectives contain a verb and focus on one of three areas; knowledge, skills and professional practice attitudes. A learning objective must be measurable. 3 When the objective is not capable of being quantified, either the goal is both too large and unwieldy, or a learning plan is not applicable in this clinical context. Where the objective is not measurable because the task is too large, this can be rectified by breaking the task down into smaller tasks, 9 continuing this process until the objective becomes measurable. 3

Effective learning objectives should be SMART. 10 A familiar acronym, SMART, highlights that a well written learning objective should be specific (S), detailed and straight forward, measurable (M) as it quantifies the goal, achievable (A) as it has the ability to be accomplished, realistic (R) as the resources to achieve the goal are available and achieved in an appropriate time frame (T). 10 Writing a SMART learning objective is an acquired tutor skill that is aided by the use of educational tools to assist the writing process.

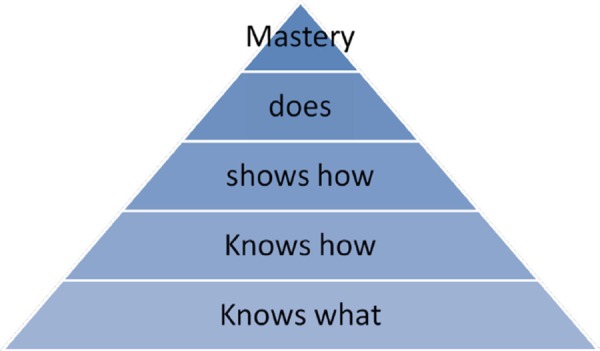

Blooms' taxonomy 4 and Millers' pyramid 4 are useful tools to develop written learning objectives. Millers' triangle (shown in Figure 2) depicts the hierarchy of skills from knowing the theory applicable to performing the skill, through to achieving skill mastery. With advancing skill expertise the verbs to define the outcomes for each skill hierarchy change. A tool that classifies verbs according to the learning domain is Bloom's taxonomy. Key words are listed and categorised to describe behaviours required of the learner, which are linked to either the cognitive domain (knowledge), psychomotor domain (skills) or professional practice domain (attitudes). Table 1 provides some examples relevant to medical ultrasound practice to assist tutors writing SMART objectives.

Figure 2.

Millers' Skill triangle (Dent and Harden 2009, p.19) depicting skill acquisitions from ‘knows what’ to ‘mastery’. Behavioural verbs can be linked to the skill stage ‘knows how’ to ‘mastery’. Knows what is declarative knowledge linked to the skill and a knowledge verb would be used to assess learner cognition of the task.

Table 1.

Verbs to describe core behaviours applicable to medical ultrasound imaging adapted from Dent and Harden 2009 p.18.

| Domain | Outcome |

|---|---|

| Knowledge | Analyse, outline, identify, describe, define, list, compare, apply, calculate, evaluate |

| Skill (task or communication) | Demonstrate, calculate, operate, perform, document, recognise, role‐play |

| Attitudes | Model, manage, specify, advocate, formulate, recommend, assess, exemplify |

Selecting the required learning strategies and resources

A learning strategy is a series of planned activities to support attainment of the learning outcome. They may be teacher or learner centred, ideally based on the learning style of the learner, and should be the most appropriate activities to achieve the outcome. 11 , 12 A learning plan preferably incorporates a wide range of adult learning activities including self‐directed learning, experiential learning, and reflective practice which combine to create a holistic learning experience. 8 Learning strategies should be written using specific words such as review, identify, perform, describe, construct and apply, to describe behavior. 13 The activities to build the knowledge and skills required to guide achievement of the learning outcome mirror these key words.

The resources required to support the learning outcome should mirror the learning strategies. The resources to accomplish a learning strategy are reliant upon tutor sonographers, resources and technology. In medical ultrasound imaging they may include criteria charts, policy documents, professional practice standards, recognised general and specialist text books, and interesting and accessible electronic learning aides and documents. The sequencing and incorporation of some or all of these types of resources are important decisions for the development of the learning plan, and will be based on the individual learner needs.

Documenting the outcome measures to identify goal achievement

A learning plan should clearly state outcome measures that identify student goals have been achieved. The outcome measures are linked to the educational behaviours specified in the learning strategies. They refer to defined activities or formative and summative assessments, which denote goal achievement when completed by the learner. For example, learner measurement of amniotic fluid index (AFI) measurement approximates tutor acquired AFI. Using this example, a misaligned outcome measure includes asking the learner to acquire and measure a single deepest pocket of amniotic fluid. This was not the specified learning goal in this example. Furthermore, there were no assigned learning strategies to support this skill outcome such as, the student will be able to describe the appropriate clinical context to acquire, measure and document a single deepest pocket of amniotic fluid in third trimester.

A learning plan provides a visual timeline of the depth and breadth of chronicled hurdles and achievements, and the time span to achieve the learning goals. Regular review of learner achievements provides feedback on learner progress and provides an opportunity to suggest further educational interventions when required. This record becomes a useful inventory of clinical progress, in particular when multiple tutors are involved in a learner's clinical skill development. A learning plan in this clinical context, has the potential to make adult learners accountable for their progress, and moves the responsibility of achieving learning outcomes from the tutors to the learner.

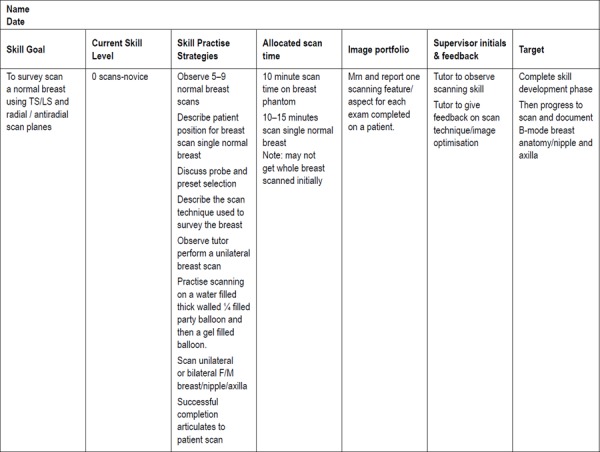

Skill acquisition plan

A skill acquisition plan provides a framework for skill acquisition and skill stratification; and is an extension of the application of the student learning plan. One unique feature of a skill acquisition plan is it requires the tutor to first undertake a task analysis. 9 , 15 This is a process where a skill is broken down into steps. 15 Subsequent to identifying the skill steps, they are learned in a stepped progression of tasks, termed scaffolding. 16 Scaffolding is an important teaching tenet to enable a learners' progression from simple to complex skill acquisition. In Figure 3, the skill acquisition plan provides a suggested framework and plan for a learner to acquire and develop the skills to perform a breast scan. A skill acquisition plan involves the tutor using formal and informal aides to assist development of scanning skills. 17 Informal aides include thick walled balloons filled with 1–2 cups of viscous scanning gel and tied tightly and formed in a shape to resemble an ellipse. Scanning over a phantom with curved edges develops important scanning skills required to perform a breast scan. Skill acquisition plans provide a task development timeline and tangible hurdles to accomplish. A skill acquisition plan is but one tool to assist skill development.

Figure 3.

Skill acquisition plan provides a suggested articulation for s novice sonographer (adapted from ASUM learning plan).

Conclusion

A learning plan is one tool to manage an adult learner's clinical education thoroughfare in their discipline. Using a learning or skill acquisition plan is a straight forward process once the learning need is known. When the learning need is restated as a measurable and SMART objective, 10 a learning or skill acquisition plan is a suitable instrument to use to realise the learning goal. The skills to develop, and use a learning or skill acquisition plan are also learned, but are an integral component to the ultrasound tutor's skill set.

Competing Interests

None Identified

References

- 1. Unigwe SC. Lecturers' Appraisal of Application of Andragogical Learning Principles during Instructions in Tertiary Institutions. Journal of Educational and Social Research 2013; 3 (8): 151–56. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Curran MK. Examination of the Teaching Styles of Nursing Professional Development Specialists, Part II: Correlational Study on Teaching Styles and Use of Adult Learning Theory. J Contin Educ Nurs 2014; 45 (8): 353–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tempest E. How to draw up SMART objectives that will work. In Nursing Times. London: Emap Limited; 2012. p. 37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dent JA, Harden RM. A Practical Guide for Medical Teachers. Third ed. Edingurgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fater KH. Gap Analysis: A Method to Assess Core Competency Development in the Curriculum. Nurs Educ Perspect 2013; 34 (2): 101–05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rose M, Best D. Transforming Practice through Clinical Education, Professional supervision and Mentoring. Edinburgh: Elsevier‐Churchhill Livingstone; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7. RANZCOG . The Royal Australian and New Zealand of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists: In‐House Clinical Assessment Ultrasound 2014 [15/8/2014]; Available at https://www.ranzcog.edu.au/assessment‐workshops‐forms/in‐hospital‐clinical‐assessments.html.

- 8. Talbot M. Monkey see, monkey do: a critique of the competency model in graduate medical education. Med Educ 2004; 38 (6): 587–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Walker D, Griffiths L. SmART Literacy Learning – Let's Step Outside the Box Educating Young Children. Learning and Teaching in the Early Childhood Years 2009; 15 (1): 13–32. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Reed VA, Schifferdecker KE, Turco MG. Motivating learning and assessing outcomes in continuing medical education using a personal learning plan. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2012; 32 (4): 287–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen CC, Jones KT, Moreland K. Differences in learning styles: implications for accounting education and practice. The CPA Journal 2014: 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mumford A. Putting learning styles to work: An integrated approach. Industrial and Commercial Training 1995; 27 (8): 28. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mutton T, Hagger H, Burn K. Learning to plan, planning to learn: the developing expertise of beginning teachers. Teachers and Teaching 2011; 17 (4): 399–416. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Phipps D, Meakin GH, Beatty PC, Nsoedo C, Parker D. Human factors in anaesthetic practice: insights from a task analysis. Br J Anaesth 2008; 100 (3): 333–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sullivan ME, Brown CV, Peyre SE, Salim A, Martin M, Towfigh S, Grunwald T. The use of cognitive task analysis to improve the learning of percutaneous tracheostomy placement. Am J Surg 2007; 193 (1): 96–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rovegno I, Cone SL, Cone TP. An accomplished teacher's use of scaffolding during a second‐grade unit on designing games. Res Q Exerc Sport 2012; 83: 221–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nicholls D, Sweet L, Hyett J. Psychomotor skills in medical ultrasound imaging: an analysis of the core skill set. J Ultrasound Med 2014; 33: 1349–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]