Abstract

Background

Research consistently shows drinking-to-cope (DTC) motivation is uniquely associated with drinking-related problems. We furthered this line of research by examining whether DTC motivation is predictive of processes indicative of poor emotion regulation. Specifically, we tested whether nighttime levels of episode-specific DTC motivation, controlling for drinking level, were associated with intensified affective reactions to stress the following day (i.e., stress-reactivity).

Design and Methods

We used a micro-longitudinal design to test this hypothesis in two college student samples from demographically distinct institutions: a large, rural state university (N = 1421; 54% female) and an urban historically Black college/university (N = 452; 59% female).

Results

In both samples the within-person association between daily stress and negative affect on days following drinking episodes was stronger in the positive direction when previous night’s drinking was characterized by relatively higher levels of DTC motivation. We also found evidence among students at the state university that average levels of DTC motivation moderated the daily stress-negative affect association.

Conclusions

Findings are consistent with the notion that DTC motivation confers a unique vulnerability that affects processes associated with emotion regulation.

Keywords: Drinking to cope motivation, alcohol use, stress-reactivity

It is commonly found that individuals who are motivated to consume alcohol as a means of alleviating negative affect and coping with stress (i.e., drinking to cope, or DTC) experience more drinking-related problems, even after drinking level is controlled (e.g., Carey & Correia, 1997; Cooper, Frone, Russell, & Mudar, 1995; Merrill & Read, 2010; Merrill, Wardell, & Read, 2014; Simons, Gaher, Correia, Hansen, & Christopher, 2005). This unique effect is often attributed to a feedback process in which this maladaptive coping strategy results in continued distress and further deterioration of coping abilities and resources (Abrams & Niaura, 1987; Cooper, Russell, & George, 1988; Merrill et al., 2014). Although numerous studies have examined DTC motivation as an outcome of coping styles and other factors relevant to the stress and coping process (for a review, see Kuntsche, Knibbe, Gmel, & Engels, 2006), few studies have focused on DTC motivation as a predictor of emotion regulation processes. In the present study, we used a micro-longitudinal design to examine whether affective reactions to daily stress on days following drinking episodes were exacerbated by the degree to which drinking was motivated by coping reasons. We examined this process in two samples of college student drinkers – a high-risk population for drinking problems (Jackson, Sher, & Park, 2005; O’Malley & Johnston, 2002).

Multiple studies have linked individual differences in DTC motivation levels to indicators of poor emotion regulation. For example, results from Veilleux, Skinner, Reese and Shaver’s (2014) cross-sectional study of college students and non-college adults showed that individuals with high DTC motivation levels were more likely to report feeling intense negative emotions and that this association was mediated by a lack of emotional clarity and deficient emotion-regulation strategies. Similarly, Colder (2001) found that individuals high in DTC motivation, but not other drinking motives, showed a stronger positive association between life stress and heightened electrodermal reactivity to a negative mood induction. Finally, Littlefield, Sher and Wood’s (2010) longitudinal study showed that increases in DTC motivation in young adulthood were related to increases in personality dimensions associated with maladaptive emotion-regulation and low self-control, namely neuroticism and impulsivity.

Results from studies using micro-longitudinal designs also support the notion that DTC motivation might have deleterious effects on emotion-regulation processes. Armeli, O’Hara, Ehrenberg, Sullivan and Tennen (2014) found that college students reported higher levels of negative affect and fatigue on days following drinking episodes characterized by relatively higher levels of DTC motivation, independent of drinking level. Similarly, Piasecki, Sher, Slutske and Jackson’s (2014) ecological momentary assessment study of the subjective effects of drinking in a sample of community adults indicated that individuals with higher overall levels of DTC motivation were more likely to report, in real-time, “feeling worse” after consuming their first drink. In both studies, it appears that DTC motivation might impede effective emotion regulation and possibly prolong distress, which could help explain DTC motivation’s unique association with short- and long-term drinking-related consequences (Merrill et al., 2014).

Armeli et al. (2014) posited that the deleterious effects of DTC motivation on distress might be explained by processes related to the attention allocation model (AAM; Steele & Josephs, 1988, 1990) and ego-depletion (Baumeister, Vohs, & Tice, 2007; Muraven & Baumeister, 2000). Consistent with the AAM, coping-motivated drinking might result in a narrowing of attention and increased focus on distress, which in turn, would require continued regulation of affective states. Sustained emotion regulation efforts could further drain individuals’ limited supply of self-control resources (i.e., ego-depletion), which is often associated with fatigue (Hagger, Wood, Stiff, & Chatzisarantis, 2010). These hypothesized mechanisms related to decreased self-control resources are consistent with findings showing DTC motivation related to distinct subtypes of drinking-related problems relevant to self-regulation such as impulse control, poor self-care, academic and occupational problems, and exacerbated negative affect (Merrill & Read, 2010; Merrill et al., 2014).

Further support for the posited negative feedback effects of DTC motivation in the stress and coping process would come from demonstrating that discrete instances of elevated levels of DTC motivation are proximally related to decreased ability to regulate affect. Research using micro-longitudinal designs have often conceptualized the within-person association between daily or momentary levels of stress and negative affect (i.e., how negative affect changes as a function of deviations from individual’s mean stress levels or “stress-reactivity”) as an indicator of poor emotion regulation. Studies using this approach often focus on how stress-reactivity is related to person-level vulnerability factors; for example, numerous studies have shown that stress-reactivity is stronger for individuals high in neuroticism (Bolger & Zuckerman, 1995; Gunthert, Cohen, & Armeli, 1999). Other studies have found stronger daily stress-reactivity associated with genetic risk (Gunthert et al., 2007) and among individuals who reported childhood trauma (Glaser, van Os, Portegijs, & Myin-Germeys, 2006). It should be noted that Veilleux et al. (2014) did not find a between-person association between global, retrospective reports of emotional-reactivity (i.e., the tendency to respond strongly to emotional stimuli) and average levels of DTC motivation. However, retrospective reports of such micro-processes tend not to correlate with more sophisticated approaches that model such processes using close-to-real time reports (Henry, Moffitt, Caspi, Langley, & Silva, 1994; Shiffman, 2000; Todd, Tennen, Carney, Armeli, & Affleck, 2004). Indeed, Curran and Bauer (2011) warn against drawing inferences about within-person processes – such as how affect changes within-person from day to day – from findings obtained at the between-person level of analysis (e.g., Veilleux et al., 2014).

In the present study we used a micro-longitudinal design in which college students from two demographically disparate college student samples – a large, rural state university and an urban historically Black college/university (HBCU) – reported daily on their drinking level, drinking motivation, stress and negative affect. Repeated assessment of these variables in close to real time allowed us to advance our understanding of the proximal within-person effects of DTC motivation on the stress and coping process in several ways. First, it allowed us to minimize recall biases that might be present in studies using retrospection of such processes (e.g., Veilleux et al., 2014). Second, it allowed us to evaluate how relative changes in episode-specific levels of DTC motivation, controlling for the amount of alcohol consumed, were related to temporally proximal stress-reactivity. Thus, our core hypothesis was that on days after drinking episodes, individuals will show a stronger positive association between daily stress and negative affect when drinking episodes were characterized by higher levels of DTC motivation compared to lower levels of DTC motivation.

We also attempted to rule out several alternative explanations for the moderating effects of episode-specific levels of DTC motivation. First, we tested whether greater stress-reactivity was due to relative changes in daily physical ailments, which might result from previous night’s drinking. We also examined whether the effect of DTC motivation was distinct from drinking motives to enhance positive emotions (DTE), which is commonly reported among college students (e.g., Merrill et al., 2014; O’Hara, Armeli, & Tennen, 2015) and is correlated with DTC motivation at the episode level of analysis (Arbeau, Kuiken, & Wild, 2011; O’Hara et al., 2015).

Finally, given recent evidence indicating that DTC motivation has both state and trait components (Armeli et al., 2014; Arbeau et al, 2011; O’Hara, Boynton et al., 2014), we also examined whether average levels of DTC motivation (aggregated across drinking episodes) exerted a separate person-level vulnerability on daily stress-reactivity. Given previous research indicating an association between DTC motivation and neuroticism (Cooper, Agocha, & Sheldon, 2000) and between neuroticism and stress-reactivity (Gunthert et al., 1999; O’Hara, Armeli, Boynton, & Tennen, 2014), we included neuroticism as a control variable.

Methods

Participants and procedure

Procedures were approved by the institutional review boards at a large, rural state university (sample 1) and an urban HBCU (sample 2), both located on the east coast. The study protocol was nearly identical at both universities. Undergraduates were recruited across multiple semesters through a variety of methods including the psychology research pool, campus-wide broadcast emails and flyers, and word-of-mouth to participate in a study about daily experiences and health-related behavior. Only students who reported drinking alcohol at least twice in the past month and had not received treatment for alcohol use (measured during prescreening) were eligible. Students who qualified (sample 1 N = 1,818; sample 2 N = 741) attended an introductory session at which time they provided informed consent and were given log-in information for the secure website at which they could first complete a baseline survey, in which demographics and neuroticism were assessed, and subsequently, the daily diary surveys.

Several weeks after completing the baseline survey, participants began the daily diary portion of the study. Each day for 30 days, between the hours of 2:30 p.m. and 7:00 p.m., participants accessed a secure website and completed a brief survey. This time window was selected to coincide with most undergraduate students’ naturally occurring end of school day but before typical evening activities begin (including drinking). Relevant to our study, participants were asked each day to report their daily affect, stress and physical ailments, as well as alcohol consumption for the past evening (i.e., after the previous day’s survey) and for the current day. If any alcohol use was reported, participants were queried about their episode-specific drinking motivation (i.e., DTC and DTE). Participants were paid or provided with classroom credit for both the baseline survey and the daily diary portions of the study.

Participants were not included in the final analyses if they did not participate in the daily diary phase or participated but failed to complete 50% of the daily surveys (sample 1 n = 173; sample 2 n = 243), or if they were missing data on relevant person- or daily-level variables (sample 1 n = 224; sample 2 n = 46). Participants were not excluded based on demographics as our interest was to test our hypotheses in two unique college samples, and not to draw comparisons based on race or any other demographic difference between samples. This procedure resulted in final samples for analysis of N = 1421 (sample 1) and N = 452 (sample 2). Sample 1 had a mean age of 19.3 years (SD = 1.4), was 54% female, was mostly freshmen and sophomores (72%), and was mostly White (83%). Sample 2 had a mean age of 20.2 years (SD = 1.7), was 59% female, was mostly juniors or higher (56%) and was mostly African American/Black (96%).

For sample 1, excluded participants were more likely to be male (55%), χ2(1) = 10.2, p = .001, non-White (34%), χ2(1) = 50.9, p < .001, freshmen and sophomores (80%), χ2(1) = 11.9, p = .001, and younger (Mage = 19.1, SD = 1.5), t(1814) = 2.0, p = .04. For sample 2, excluded participants were more likely to be male (57%), χ2(1) = 16.7, p < .01, freshmen and sophomores (52%), χ2(1) = 5.0, p = .025, and younger (Mage = 19.9, SD = 1.6), t(735) = −2.1, p = .03.

It should be noted that although (Armeli et al., 2014) examined the association between episode-specific levels of DTC motivation and next-day negative affect in the state university sample, they did not examine daily stress and the posited moderating effect of DTC motivation on the daily stress-negative affect association (which was the focus of the present study).

Measures

Daily alcohol use

Participants reported each day the number of alcoholic drinks they consumed the previous night “with others/in a social setting” (i.e., social drinking) and “alone/not interacting with others” (i.e., nonsocial drinking). Participants followed the same procedure for reporting number of drinks they consumed that day up to reporting time; given the low levels of daytime drinking, we collapsed across the social and nonsocial categories to create a daytime total. A drink was defined as one 12-oz. can or bottle of beer, 5-oz. glass of wine, 12-oz. wine cooler, or 1-oz. measure of distilled spirits straight or in a mixed drink. Responses were made using a 17-item scale ranging from 0 to 15, or >15 (recoded as 16). We retained each drinking type as separate control variables given that non-social drinking is posited to be more maladaptive in college drinkers (Gonzalez & Skewes, 2013) and it showed distinct effects on mood states in a Armeli et al.’s (2014) previous analysis of sample 1.

Episode-specific drinking motives

On days when participants reported drinking during the previous evening, they completed an adapted version of Cooper’s (1994) coping and enhancement drinking motives scales. Specifically, if participants reported having at least one drink they were asked, “Why did you drink last night?” DTC was assessed with the following items: To forget my ongoing problems/worries, To feel less depressed, To feel less nervous, To avoid dealing with my ongoing problems, To cheer up, Because I was angry, and To feel more confident/sure of myself. DTE was assessed with two items (Because I like the pleasant feeling and To have fun) derived from two of the higher-loading items in Cooper (1994). The imbalance of items across the two scales was due to the aims of the larger project (from which these data were drawn), which focused on different aspects of DTC motivation (which was not the focus of our analysis). Participants responded to each item using a 3-point scale (0 = no, 1 = somewhat, 2 = definitely). Responses were averaged together; Cronbach’s αs were as follows: .84 (coping subscale) and .65 (enhancement subscale) in sample 1; .84 (coping subscale) and .57 (enhancement subscale) in sample 2.1

Daily stress

Each day participants were asked to “Rate TODAY’S overall stressfulness” using a 7-point scale (0 = not at all to 6 = extremely).

Daily negative affect

Each day participants reported on their affective states using adjective rating scales derived from the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule–Expanded (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988) and Larsen and Diener’s (1992) mood circumplex; responses were made using a 5-point scale (1 = not at all to 5 = extremely). Negative affect was measured with 6 items (nervous, anxious, sad, dejected, angry, hostile). Responses were averaged together. Cronbach’s α’s were .82 for sample 1 and .81 for sample 2.

Daily physical ailments

Each day participants rated whether they were “feeling ill: cold, flu, headache, etc.” today using a 7-point scale (0 = not at all to 6 = extremely).

Neuroticism

At baseline participants completed the 48-item neuroticism scale from the NEO-PI-R (Costa & McCrae, 1992). Participants responded to each statement using a Likert-type scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), and responses were averaged together. Cronbach’s α’s were .93 (sample 1) and .91 (sample 2).

Statistical analysis

We used two-level hierarchical linear models (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) to test the main hypotheses regarding the moderating effects of episode-specific and mean levels of DTC motivation on the within-person stress-affect association. The central part of the model predicted current day’s negative affect from previous evening’s episode-specific DTC motivation and current day’s stress rating. We focused only on nighttime drinking because of the very low rate of daytime drinking. We controlled for prior day’s negative affect (prior to the drinking episode) to examine change in affect from day t – 1 to day t as a function of current day’s stress levels. Models also included the following control variables: DTE motivation and levels of social and nonsocial drinking from the previous evening, current day physical ailments and total daytime alcohol use up to reporting time. All of these variables were reported on day t. We also controlled for sex (coded 0 = male, 1 = female) and weekend–weekday (0 = Sunday through Thursday; 1 = Friday and Saturday).

Episode-specific DTC motivation and daily stress were person-mean centered and their respective means were also included in the model, which allowed us to disentangle within- and between-person associations (Curran & Bauer, 2011). This procedure was also done for DTE motivation, previous night’s social and nonsocial drinking and current day’s ailments in order to evaluate their possible moderating effects. For parsimony and because we made no direct predictions about their within-person effects, all other dimensional variables were grand-mean centered. Also for parsimony, only the intercepts and the slopes for daily stress and DTC drinking motives were specified as random effects. To test the hypothesized interactive effects between episode-specific and mean levels of DTC motivation and daily stress, product terms were entered in a second step. The daily stress-neuroticism interaction was also included because this effect is commonly found and including it would help to reduce error variance in the model. In a final step we included the interactions involving social and nonsocial drinking, DTE motivation and daily ailments, which allowed us to test whether our interaction of interest remained significant after accounting for these possibly confounded effects.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

For sample 1, the final 1,421 participants completed 88% of the 30 daily surveys (for a total of 37,514 person-day surveys out of a possible 42,630). Participants in sample 1 drank on 20.6% of the nights (7,728 person-days); of these nights, 83% (6,419 person-days; a mean of 4.51 drinking episodes per person, SD = 3.17) had complete data and were analyzed. For sample 2, the final 452 participants completed 80% of the 30 daily surveys (for a total 10,848 person-day surveys out of a possible 13,560). Participants in sample 2 drank on 23.7% of the nights (2571 person-days); of these nights, 77% (1,972 person-days; a mean of 4.36 drinking episodes per person, SD = 3.10) had complete data and were analyzed. Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for the core study variables. Drinks per episode were somewhat higher in sample 1, but the two samples were generally similar in terms of the mean levels of the remaining study variables.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics

| Sample 1 | Sample 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Percent social drinking daysa | 95.9% | 90.9% |

| Percent non-social drinking daysa | 15.9% | 30.0% |

| Total drinks per episode | 5.78 (4.41) | 3.86 (3.32) |

| Social drinks per episodeb | 5.45 (3.75) | 3.43 (2.69) |

| Non-social drinks per episodeb | 3.48 (3.40) | 2.47 (1.97) |

| DTC motivation | .20 (.29) | .21 (.30) |

| DTE motivation | 1.20 (.53) | 1.03 (.53) |

| Daily stress | 2.48 (1.12) | 2.43 (1.15) |

| Daily physical ailments | .80 (1.11) | .52 (.86) |

| Daily negative affect | 1.37 (.44) | 1.33 (.44) |

| Neuroticism | 3.53 (.75) | 3.41 (.73) |

| Daytime drinkingc | .29 (1.70) | .61 (2.32) |

Note. Values are Means (SDs). DTC = drinking to cope; DTE = drinking to enhance.

Percent of total drinking episodes that had this type of drinking.

For episodes when this type of drinking occurred.

Mean (SD) per day after nighttime drinking episodes. Sample 1: large, rural state university; Sample 2: historically Black college/university

Multilevel regression results

Table 2 shows the results of the multilevel regressions. For parsimony and to avoid type I error inflation, we interpret only the results for the relevant predictors involved in the hypothesized interactions. In both samples, relatively higher levels of DTC motivation from the prior evening and current day stress were associated with higher levels of current day negative affect (see block 1).

Table 2.

Multilevel regression results predicting daily negative affect

| Sample 1 |

Sample 2 |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI | 95% CI | ||||||||||

| Block | b | SE | p | LL | UL | b | SE | p | LL | UL | |

| 1 | Sex | −.027 | .023 | .228 | −.072 | .017 | −.024 | .015 | .111 | −.054 | .006 |

| Mean daily stress | .078 | .013 | <.001 | .052 | .105 | .123 | .007 | <.001 | .108 | .138 | |

| Mean non-social drinking | .047 | .029 | .110 | −.011 | .104 | .060 | .019 | .002 | .022 | .098 | |

| Mean social drinking | .009 | .014 | .501 | −.018 | .037 | .016 | .007 | .022 | .002 | .029 | |

| Mean DTC | .487 | .048 | <.001 | .393 | .581 | .447 | .030 | <.001 | .387 | .507 | |

| Mean DTE | −.032 | .023 | .166 | −.077 | .013 | −.044 | .015 | .004 | −.073 | −.014 | |

| Mean physical ailments | .041 | .014 | .004 | .013 | .069 | .030 | .007 | <.001 | .016 | .045 | |

| Neuroticism | .010 | .016 | .534 | −.021 | .041 | .021 | .010 | .037 | .001 | .042 | |

| Weekend | .021 | .017 | .218 | −.012 | .054 | −.001 | .008 | .935 | −.017 | .016 | |

| Prior day negative affect | .248 | .018 | <.001 | .214 | .283 | .167 | .009 | <.001 | .148 | .185 | |

| Daytime drinking | .016 | .005 | .001 | .007 | .025 | .011 | .003 | <.001 | .005 | .017 | |

| Daily stress | .132 | .006 | <.001 | .121 | .143 | .098 | .008 | <.001 | .083 | .114 | |

| Daily physical ailments | .002 | .004 | .541 | −.005 | .010 | .017 | .008 | .023 | .002 | .032 | |

| Episode non-social drinking | .010 | .003 | <.001 | .005 | .016 | .003 | .006 | .586 | −.009 | .016 | |

| Episode social drinking | .000 | .002 | .813 | −.003 | .003 | −.003 | .004 | .376 | −.010 | .004 | |

| Episode DTC | .270 | .030 | <.001 | .210 | .330 | .192 | .053 | <.001 | .087 | .296 | |

| Episode DTE | −.043 | .010 | <.001 | −.062 | −.023 | .003 | .018 | .851 | −.031 | .038 | |

| 2 | Daily stress × Episode DTC | .087 | .017 | <.001 | .055 | .120 | .048 | .024 | .046 | .001 | .094 |

| Daily stress × Mean DTC | .076 | .022 | <.001 | .034 | .118 | .001 | .029 | .959 | −.055 | .058 | |

| Daily stress × Neuroticism | .015 | .008 | .062 | −.001 | .030 | .027 | .011 | .017 | .005 | .048 | |

| 3 | Daily stress × Daily illness | .001 | .003 | .770 | −.006 | .008 | .007 | .005 | .161 | −.003 | .018 |

| Daily stress × Non-social drinking | −.001 | .002 | .731 | −.005 | .004 | .003 | .005 | .478 | −.006 | .013 | |

| Daily stress × Social drinking | .000 | .001 | .955 | −.003 | .003 | .000 | .003 | .959 | −.005 | .005 | |

| Daily stress × Episode DTE | −.015 | .009 | .101 | −.034 | .003 | −.001 | .013 | .917 | −.028 | .025 | |

Note. Sample 1: large, rural state university; Sample 2: historically Black college/university. DTC = drinking to cope; DTE = drinking to enhance.

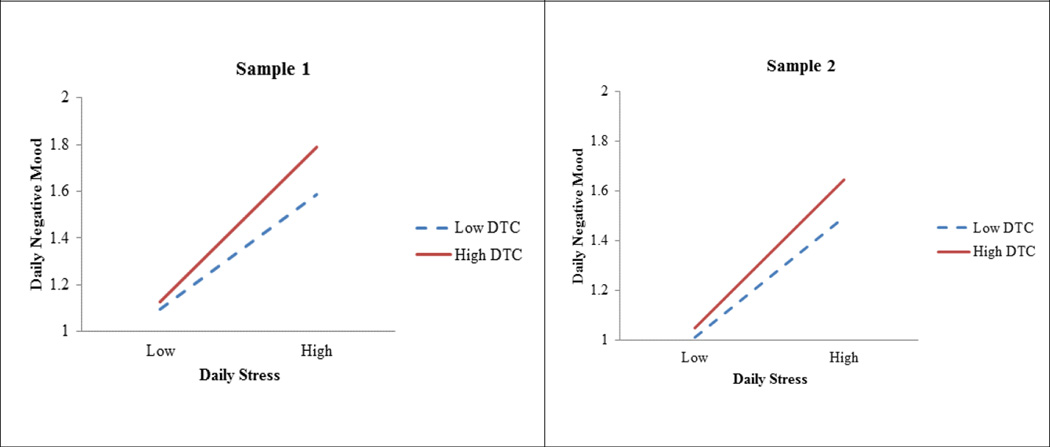

The hypothesized interactive effects are shown in block 2. In both samples, relative levels of DTC motivation from the prior evening moderated the within-person association between daily stress and negative mood (the forms of which are shown in Figure 1; low/high values of stress correspond to plus/minus 2 SDs from the mean; low/high values of DTC motivation correspond to plus/minus 1 SD from the mean). Specifically, on days following drinking episodes characterized by relatively higher levels of DTC motivation, there was a stronger positive association between relative increases in daily stress and negative affect. In sample 1, but not sample 2, we also found that aggregate level of DTC motivation moderated the within-person stress-negative affect association; specifically, individuals with higher mean levels of DTC motivation had stronger positive associations between relative changes in daily stress and negative affect.

Figure 1. Moderating effect of episode-specific levels of drinking-to-cope motivation (DTC) on daily stress-negative mood association.

Sample 1: large, rural state university; Sample 2: historically Black college/university. Results from in both samples indicate that the daily stress-negative affect associations are stronger in the positive direction on days following drinking episodes characterized by relatively higher levels of DTC motivation.

In block 3 we added the interactions between daily stress and previous evening’s social and non-social alcohol use, previous evening’s DTE motivation, and today’s physical ailments. None of these interactions was significant. Inclusion of these interaction terms did reduce the daily stress × episode-specific DTC motivation interaction in sample 2 to marginal significance (b = 0.043, SE = .024 p = .077), though this effect remained significant at the .05 alpha level in sample 1 (b = 0.092, SE = .017, p < .001).

Discussion

We found in two demographically diverse samples of college students that when individuals reported relatively higher levels of DTC motivation in their evening drinking episodes, the following day they had more intense affective reactions to daily stress (i.e., stronger within-person stress-affect associations). We also found that average levels of DTC motivation exerted a separate moderating effect that was similar in form; however this effect was limited to the state university sample.

Our findings add to previous literature on the deleterious effects of drinking as a method of coping with distress. Early social learning-based coping-deficits models (Abrams & Niaura, 1987; Cooper et al., 1988) posited a feedback loop in which DTC results in continued distress and a cycle of continued drinking, eventually leading to dependence symptoms and drinking as a method to cope with withdrawal symptoms. Findings from our study, and other recent studies (Armeli et al., 2014; Piasecki et al., 2013), begin to shed light on one aspect of this model: namely the unique link between DTC motivation and subsequent distress. Specifically, our results indicate that over and above the amount of alcohol consumed, coping reasons for drinking might impede emotion regulation processes – conceptualized in our study as the within-person stress-negative affect association. Our findings also indicate that these processes are present in more normative, non-abuse/dependent populations.

Our findings are generally consistent with recent work positing attention-allocation and ego-depletion mechanisms underlying the deleterious effects of DTC motivation. Specifically, drinking with the expressed purpose of coping could result in increased focus on distress and have the paradoxical effect of exacerbating such distress (e.g., Armeli, O’Hara et al., 2014; Piasecki et al., 2014), which in turn leads to continued emotion-regulation efforts. Sustained emotion-regulation could tax individuals’ self-regulation resources (Baumeister et al., 2007; Muraven & Baumeister, 2000), resulting in fatigue (Armeli et al., 2014) and the inability to effectively manage stressful situations, resulting in more intense affective reactions. It should be noted, however, that we did not measure attention allocation and ego depletion directly. Also, our non-experimental design does not allow us rule out other factors that might be confounded with evening levels of DTC motivation. For example, high levels of DTC motivation might be caused by concurrent negative events that arose between measurements, and it is these events, and not DTC motivation levels, that influence next day’s stress-reactivity (i.e., including prior night stress levels into the predictive model would render the moderating effect of DTC motivation non-significant). However, this pattern of findings would not be totally inconsistent with our posited framework. For example, it is possible that attention allocation process set in motion by DTC motivation could exacerbate the severity of appraisals of such stressors, which in turn causes the posited depletion effects. Future studies using more fine-grained reporting strategies in which these variables are assessed immediately prior to and during drinking episodes are needed to better evaluate these processes.

We also found a moderating effect of average levels of DTC motivation, which could indicate that chronically high levels, in addition to proximal relative levels, might exert an effect on self-control resources via the posited pathways. However, this effect was significant only in the state college sample. Although greater power might partly explain this difference, there was not even a trend observed in the HBCU sample. Ethnic differences seem like a viable explanation for this difference, but attributing it to the predominantly African American make-up of the HBCU sample (versus the predominantly Caucasian make-up of the state university sample) is problematic given the confounded nature of the minority status of the HBCU sample with other characteristics of this college. For example, African Americans in our minority sample HBCU might differ substantially from African Americans at other universities in terms of a variety of socio-economic and cultural factors. Thus, it is unclear what aspects of the samples might account for this and other differences or whether these differences are simply due to sampling variability. Again, our goal was not to examine ethnic differences in these processes. Rather, our goal was to replicate our findings in two distinct samples, which we believe is one of the strengths of the study. Future studies with the goal of testing ethnicity differences should use appropriate sampling strategies to obtain less confounded comparisons.

It should be noted that the moderating effects of DTC motivation were small in size (attesting to the high power of the study). Inspection of the size of the coefficients indicated that the effect of stress on negative affect increased by only a small amount for a unit increase in coping motivation. One possibility is that in some situations the posited myopia effects are beneficial in terms of coping, thus attenuating our moderating effects. More specifically, reports of drinking to cope in some episodes might have been indicative of using alcohol as a method to unwind or relax after successful coping. In such situations – especially if distractions (e.g., social interaction) were present – negative mood would not be exacerbated and our posited ego depletion effects would not take place. Future studies should attempt to tease out hypothetically less problematic types of coping-related drinking (e.g., drinking after engagement in the stress and coping process) from more problematic forms (e.g., drinking as a primary coping strategy).

In addition to the small effects, our results are limited to time periods temporally proximal to drinking episodes (i.e., the day after nighttime drinking), which were relatively infrequent in our samples. These issues raise the possibility that the deleterious effects of DTC motivation on stress-reactivity in daily life are negligible. However, one could posit that the reduction of self-control resources due to repeated instances of coping-related drinking accumulate over time in an additive or multiplicative fashion. Also, we observed this effect in normative, non-clinical samples. Among individuals who chronically engage in DTC, self-control resources might fail to fully recover, resulting in more intense and long-lasting deficits in their ability to regulate affective states. Future studies combining daily process and long-term longitudinal designs are needed to examine developmental trajectories for these processes and how they relate to other indicators of emotion regulation and ultimately alcohol use and alcohol-related problems.

Related to the issue of focusing on days following drinking episodes is whether or not stress-reactivity exacerbated by DTC motivation is comparable to stress-reactivity following abstinent days. This is a difficult question to address with our data given that DTC motivation was only assessed when individuals drank. Thus, from a purely analytic standpoint, it is not clear how to code abstinent days in terms of DTC motivation. Furthermore, comparing stress-reactivity across these types of days might be somewhat of an apples and oranges comparison; days after drinking episodes might be confounded with a host of other factors that might alter stress-reactivity. For example, college students are more likely to drink on nights when they do not have classes the following day (Wood, Sher, & Rutledge, 2007) and the majority of drinking among college students takes place Thursdays through Saturdays (Armeli et al., 2014; Del Boca et al., 2004; Wood et al., 2007). Days after drinking episodes, therefore, might often be characterized as low effort due to a lack of responsibilities – a factor that could be associated with reduced stress-reactivity in general. Given these issues, it is not clear how informative comparing stress-reactivity across these days might be.

Several additional limitations of our study merit mention. First, the attrition rate in our HBCU sample was considerably higher than in our state university sample. Although the pattern of differences between included and excluded participants was similar across the two samples, the final participants in our minority sample might have differed from excluded participants on other unmeasured variables; these differences might account for some of the disparate findings across the samples. Differential attrition issues aside, our goal was to replicate our findings across two distinct samples, which is what we found. Another concern relates to having individuals recall their previous night’s drinking motives; even after such a brief period there is a possibility for recall error. However, we believe that having students recall their motives from a specific episode after only several hours represents an important advancement over the overwhelming majority of studies examining dinking motives in which individuals are asked to retrospect across multiple episodes over indeterminate periods of time. Nevertheless, future research should use more fine-grained real-time reporting procedures for assessing drinking motives and their proximal correlates (e.g., Piasecki et al., 2014). A third limitation concerns the psychometric properties of some of our daily measures. Our drinking to enhance subscale demonstrated low reliability, especially in our minority sample. Thus, its associations with other variables might have been attenuated. However, as we described above (see footnote), this measure was a stronger predictor of some conceptually relevant types of drinking than drinking to cope, thus it is not clear that its low reliability was the sole reason that it was unrelated to stress-reactivity. A related psychometric issue concerns our use of single-item indicators for several measures (e.g., daily stress, physical symptoms), the reliability of which could not be assessed. However, consistent with Wanous and Reichers (1996), we believe that constructs such as these can be measured in a reliable and valid fashion with single items, which was supported by our findings showing them to be significantly related to relevant variables. More generally, micro-longitudinal studies must balance the advantages of limiting participant burden (by using brief measures) against comprehensive assessment (e.g., multi-item measures).

These limitations notwithstanding, we believe that our findings add to a growing literature focusing on the micro-processes underlying the deleterious effects of DTC motivation on well-being. Our findings provide a viable pathway – deficient emotion regulation processing – linking DTC motivation to commonly assessed drinking-related problems associated with self-regulation.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants 5P60-AA003510 and R21AA017584 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and M01RR10284 from National Center for Research Resources.

Footnotes

It should be noted that although the enhancement scale demonstrated low internal consistency (especially in sample 2), we do not believe that this renders useless a comparison of its moderating effect to that of DTC motivation. For example, results of a multilevel regression analysis (using the analytic procedure described below) in which we predicted social drinking levels from both measures of episode-specific motives indicated that enhancement motives were a stronger unique predictor of social drinking in the state university sample (enhancement motives: b = 2.64, p < .001, versus DTC motives: b = 1.23, p < .001) and in the HBCU sample (b = 1.59, p < .001 versus DTC motives: b = −0.22, p = .29). Thus, in this case, the relatively low reliability of the enhancement measure did not attenuate its effects, at least relative to the effects of DTC motivation.

Contributor Information

Stephen Armeli, Email: armeli@fdu.edu.

Ross E. O’Hara, Email: rossohara.psych@gmail.com.

Jon Covault, Email: jocovault@uchc.edu.

Denise M. Scott, Email: d_m_scott2@howard.edu.

Howard Tennen, Email: tennen@nso1.uchc.edu.

References

- Abrams DB, Niaura RS. Social learning theory. In: Blane HT, Leonard KE, editors. Psychological theories of drinking and alcoholism. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1987. pp. 131–178. [Google Scholar]

- Arbeau KJ, Kuiken D, Wild TC. Drinking to enhance and to cope: A daily process study of motive specificity. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:1174–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armeli S, O’Hara RE, Ehrenberg E, Sullivan TP, Tennen H. Episode-specific drinking to cope motivation, daily mood and fatigue-related symptoms among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75:766–774. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armeli S, Tennen H, Todd M, Carney MA, Mohr C, Affleck G, Hromi A. A daily process examination of the stress-response dampening effects of alcohol consumption. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17:266–276. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.4.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Vohs KD, Tice DM. The strength model of self-control. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2007;16:351–355. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Zuckerman A. A framework for studying personality in the stress process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:890–902. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Correia CJ. Drinking motives predict alcohol-related problems in college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:100–105. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colder CR. Life stress, physiological and subjective indexes of negative emotionality, and coping reasons for drinking: Is there evidence for a self-medication model of alcohol use? Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15:237–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6:117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M, Agocha V, Sheldon MS. A motivational perspective on risky behaviors: The role of personality and affect regulatory processes. Journal of Personality. 2000;68:1059–1088. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:990–1005. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Russell M, George WH. Coping, expectancies, and alcohol abuse: A test of social learning formulations. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97:218–230. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Jr, McCrae RR. NEO personality inventory-revised (NEO-PI-R) and NEO five-factor inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. The disaggregation of within-person and between-person effects in longitudinal models of change. Annual Review of Psychology. 2011;62:583–619. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Boca FK, Darkes J, Greenbaum PE, Goldman MS. Up Close and Personal: Temporal Variability in the Drinking of Individual College Students During Their First Year. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:155–164. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser J, van Os J, Portegijs PM, Myin-Germeys I. Childhood trauma and emotional reactivity to daily life stress in adult frequent attenders of general practitioners. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2006;61:229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez VM, Skewes MC. Solitary heavy drinking, social relationships, and negative mood regulation in college drinkers. Addiction Research & Theory. 2013;21:285–294. [Google Scholar]

- Gunthert KC, Cohen LH, Armeli S. The role of neuroticism in daily stress and coping. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:1087–1100. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.5.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunthert KC, Conner TS, Armeli S, Tennen H, Covault J, Kranzler HR. Serotonin transporter gene polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) and anxiety reactivity in daily life: A daily process approach to gene-environment interaction. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2007;69:762–768. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318157ad42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagger MS, Wood C, Stiff C, Chatzisarantis NLD. Ego depletion and the strength model of self-control: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2010;136:495–525. doi: 10.1037/a0019486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry B, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Langley J, Silva PA. On the ‘remembrance of things past’: A longitudinal evaluation of the retrospective method. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6:92–101. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Sher KJ, Park A. Drinking among college students: Consumption and consequences. In: Galanter M, editor. Recent developments in alcoholism (Vol. 17): Alcohol problems in adolescents and young adults. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 2005. pp. 85–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Who drinks and why? A review of socio-demographic, personality, and contextual issues behind the drinking motives in young people. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:1844–1857. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen RJ, Diener E. Promises and problems with the circumplex model of emotion. In: Clark MS, editor. Emotion: Review of personality and social psychology, No. 13. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1992. pp. 25–59. [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Sher KJ, Wood PK. Do changes in drinking motives mediate the relation between personality change and “maturing out” of problem drinking? Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119:93–105. doi: 10.1037/a0017512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Read JP. Motivational pathways to unique types of alcohol consequences. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:705–711. doi: 10.1037/a0020135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Wardell JD, Read JP. Drinking motives in the prospective prediction of unique alcohol-related consequences in college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75:93–102. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muraven M, Baumeister RF. Self-regulation and depletion of limited resources: Does self-control resemble a muscle? Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:247–259. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara RE, Armeli S, Boynton MH, Tennen H. Emotional stress-reactivity and positive affect among college students: The role of depression history. Emotion. 2014;14:193–202. doi: 10.1037/a0034217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara RE, Armeli S, Tennen H. College students’ drinking motives and social-contextual factors: Comparing associations across levels of analysis. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2015;29:420–429. doi: 10.1037/adb0000046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara RE, Boynton MH, Scott DM, Armeli S, Tennen H, Williams C, Covault J. Drinking to cope among African American college students: An assessment of episode-specific motives. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28:671–681. doi: 10.1037/a0036303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. Epidemiology of alcohol and other drug use among American college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;(Supplement 14):23–39. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki TM, Cooper ML, Wood PK, Sher KJ, Shiffman S, Heath AC. Dispositional drinking motives: Associations with appraised alcohol effects and alcohol consumption in an ecological momentary assessment investigation. Psychological Assessment. 2014;26:363–369. doi: 10.1037/a0035153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki TM, Sher KJ, Slutske WS, Jackson KM. Hangover frequency and risk for alcohol use disorders: Evidence from a longitudinal high-risk study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:223–234. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. 2nd. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S. Real-time self-report of momentary states in the natural environment: Computerized ecological momentary assessment. In: Stone AA, Turkkan JS, Bachrach CA, Jobe JB, Kurtzman HS, Cain VS, editors. The science of self-report: Implications for research and practice. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2000. pp. 277–296. [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Gaher RM, Correia CJ, Hansen CL, Christopher MS. An affective-motivational model of marijuana and alcohol problems among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:326–334. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Josephs RA. Drinking your troubles away. II: An attention-allocation model of alcohol’s effect on psychological stress. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97:196–205. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.2.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Josephs RA. Alcohol myopia. Its prized and dangerous effects. American Psychologist. 1990;45:921–933. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd M, Tennen H, Carney M, Armeli S, Affleck G. Do we know how we cope? Relating daily coping reports to global and time-limited retrospective assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;86:310–319. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.2.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veilleux JC, Skinner KD, Reese ED, Shaver JA. Negative affect intensity influences drinking to cope through facets of emotion dysregulation. Personality and Individual Differences. 2014;59:5996–101. [Google Scholar]

- Wanous JP, Reichers AE. Estimating the reliability of a single-item measure. Psychological Reports. 1996;78:631–634. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood PK, Sher KJ, Rutledge PC. College student alcohol consumption, day of the week, and class schedule. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31(7):1195–1207. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00402.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]