Abstract

The strict anaerobe Clostridium difficile is the most common cause of nosocomial diarrhea, and the oxygen-resistant spores that it forms have a central role in the infectious cycle. The late stages of sporulation require the mother cell regulatory protein σK. In Bacillus subtilis, the onset of σK activity requires both excision of a prophage-like element (skinBs) inserted in the sigK gene and proteolytical removal of an inhibitory pro-sequence. Importantly, the rearrangement is restricted to the mother cell because the skinBs recombinase is produced specifically in this cell. In C. difficile, σK lacks a pro-sequence but a skinCd element is present. The product of the skinCd gene CD1231 shares similarity with large serine recombinases. We show that CD1231 is necessary for sporulation and skinCd excision. However, contrary to B. subtilis, expression of CD1231 is observed in vegetative cells and in both sporangial compartments. Nevertheless, we show that skinCd excision is under the control of mother cell regulatory proteins σE and SpoIIID. We then demonstrate that σE and SpoIIID control the expression of the skinCd gene CD1234, and that this gene is required for sporulation and skinCd excision. CD1231 and CD1234 appear to interact and both proteins are required for skinCd excision while only CD1231 is necessary for skinCd integration. Thus, CD1234 is a recombination directionality factor that delays and restricts skinCd excision to the terminal mother cell. Finally, while the skinCd element is not essential for sporulation, deletion of skinCd results in premature activity of σK and in spores with altered surface layers. Thus, skinCd excision is a key element controlling the onset of σK activity and the fidelity of spore development.

Author Summary

Clostridium difficile, a major cause of antibiotic-associated diarrhea, produces resistant spores that facilitate its persistence in the environment including hospitals. C. difficile transmission is mediated by contamination of gut by spores. Understanding how this complex developmental process is regulated is fundamental to decipher the C. difficile transmission and pathogenesis. A less tight connection between the forespore and mother cell lines of gene expression is observed in C. difficile compared to Bacillus subtilis especially at the level of the late sigma factor, σK. In C. difficile, the sigK gene is interrupted in most of the strains by a prophage-like intervening sequence, skinCd, which is excised during sporulation. Contrary to B. subtilis, CD1231 encoding the large serine recombinase required for skinCd excision, is constitutively expressed and a recombination directionality factor, whose synthesis is detected only in the mother cell, restricts skinCd excision to this terminal cell. These two proteins are necessary and sufficient to trigger skinCd excision promoting the timely appearance of σK, which in turn switches-on late sporulation events. While several strains of C. difficile lack a skin element, we show that deletion of skinCd results in premature σK activity and in spores with altered surface layers, a property that might be important for host colonization.

Introduction

Endosporulation is an ancient bacterial cell differentiation process allowing the conversion of a vegetative cell into a mature spore through a series of morphological steps [1, 2]. Many bacilli, clostridia and related organisms form bacterial spores. The spores have the ability to withstand extreme physical and chemical conditions and their resistance properties allow them to survive for long periods in a variety of environments. Spores serve as the infectious vehicle for several pathogens such as Bacillus anthracis, Bacillus cereus and Clostridium difficile [3, 4]. C. difficile is the main cause of antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Disruption of the intestinal flora caused by antibiotherapy increases the risk to develop a C. difficile infection. After ingestion, C. difficile spores germinate in the intestine in the presence of specific bile salts [5]. Then, vegetative forms multiply and produce two toxins, TcdA and TcdB, which are the main virulence factors [6]. These toxins cause enterocyte lysis and inflammation leading to diarrhea, colitis, pseudomembranous colitis or more severe symptoms including bowel perforation, sepsis and death. During the infection process, C. difficile also forms spores in the gut that are essential for transmission of this strict anaerobe and contribute to the establishment of reservoirs in the environment including the host and hospital settings [7, 8].

Despite the importance of spores in the infectious cycle, our knowledge of the molecular mechanisms underlying spore development in C. difficile is still scarce. Sporulation has been extensively studied in the model organism Bacillus subtilis [9, 10]. At the onset of sporulation, an asymmetric division forms a forespore and a mother cell. A key developmental transition is when the mother cell finishes engulfing the forespore, which becomes fully surrounded by the mother cell. The mother cell maintains metabolic potential in the forespore and contributes to assembly of the spore protective structures and to the release of mature spores. The developmental program of sporulation is mainly governed by the sequential appearance of four cell type-specific sigma factors: σF in the forespore and σE in the mother cell control early stages of development, prior to engulfment completion, and are replaced by σG and σK following engulfment completion. The main morphological stages of sporulation are conserved among spore-formers, which also share a core of sporulation genes [11, 12]. Nevertheless, recent work has highlighted important differences in the genetic control of sporulation between the aerobic bacilli and the anaerobic clostridia [13–15].

In C. difficile, the main functions and periods of activity of the sporulation σ factors are largely conserved relative to B. subtilis [16–18]. In B. subtilis, several mechanisms including signaling pathways between the two compartments and the architecture of the mother cell- and forespore-specific lines of gene expression, formed by interlocked feed-forward loops (FFLs), converge for the timely activation of the σ factors at specific developmental stages [9, 19]. However, in C. difficile, the communication between the forespore and the mother cell appears less effective, contributing for a weaker connection between morphogenesis and gene expression [16–18]. Indeed, the activation of the σE regulon in the mother cell just after asymmetric division, is rigorously dependent on σF in B. subtilis, but is partially independent of σF in C. difficile. Likewise, the synthesis of the forespore signaling protein SpoIIR, essential for pro-σE processing, is strictly dependent on σF in B. subtilis but partially independent of σF in C. difficile [18]. Furthermore, in B. subtilis, the onset of σG activity coincides with engulfment completion and requires the activity of σE, while in C. difficile σG activity is detected in pre-engulfment sporangia and this early activity is independent of σE [20, 21]. Finally, several levels of regulation ensure that the activity of σK in B. subtilis is restricted to the mother cell following engulfment completion. Firstly, the sigK gene is interrupted by an intervening prophage-like element, skinBs. Secondly, expression of sigK and of spoIVCA encoding a member of the large serine recombinases (LSRs) superfamily [22] responsible for skinBs excision is under the control of σE and requires the transcriptional regulator SpoIIID [19, 23]. Expression of spoIIID is also controlled by σE, but since SpoIIID is auto-regulated [24], a coherent FFL delays expression of the spoIVCA and sigK genes towards the end of engulfment [19, 25]. Moreover, σK activity depends on the cleavage of an inhibitory pro-sequence, a step controlled by σG. Finally, σK directs expression of an anti-sigma factor, CsfB that inhibits σE, thereby promoting transition from σE- to σK-controlled stages in the mother cell [26]. σK is required for assembly of the spore cortex and the more external coat, the main spore surface structures, as well as for mother cell lysis. The segregation of σK activity to post-engulfment sporangia in B. subtilis is explained by multi-level regulation of σK synthesis and activation. Redundancy ensures fail-safe solutions and increases robustness of the developmental process.

In C. difficile, σK is dispensable for cortex biogenesis but is required for the assembly of the spore coat and of the exosporium and for mother cell lysis [17]. sigK is interrupted by a skinCd element, which is excised during sporulation [27]. The skin elements of B. subtilis and C. difficile have different sizes and gene content and are inserted at different sites and in opposite orientation indicating that integration into sigK has occurred independently during evolution [27]. Previous studies have also shown that some transcription of sigK takes place during engulfment [17]. However, σK of C. difficile lacks a pro-sequence [27] and accordingly, σG is dispensable for σK activation [16–18]. In the absence of this cleavage at the end of engulfment, skinCd excision is likely a crucial element in the regulation of σK activity in C. difficile. Importantly, given the role of σK in the assembly of the spore surface layers together with the observation that some strains of C. difficile lack skinCd [27, 28], it is imperative to better understand excision of the element in this organism.

The CD1231 gene, located within skinCd, codes for a protein similar to the SpoIVCA recombinase of skinBs [27, 29]. Surprisingly, σE does not control CD1231 expression in C. difficile [18, 30], which, as we now show, is expressed constitutively. In this work, we studied the role of CD1231 in sporulation and in skinCd excision. We demonstrated that another factor present in the skinCd element, CD1234 encoded by a gene under σE and SpoIIID control is required for skinCd excision but not integration. Thus, CD1234 is a recombination directionality factor that restricts skinCd excision to the mother cell. Importantly, we showed that skinCd is a key element in controlling the onset of σK activity, which in turn is important for proper spore morphogenesis and function.

Results

Role of CD1231 in sporulation

The skinCd element of strain 630Δerm inserted into the sigK gene contains 19 genes (Fig 1A). CD1231, located immediately upstream of the 3´-moiety of sigK (CD1230), is the unique gene within the skinCd element coding for a protein with similarity to large serine recombinases (LSRs) superfamily [22]. The first 300 amino acid residues of CD1231 share 24% identity with SpoIVCA, the recombinase encoded by skinBs [31], and 30% identity over its entire length to the SprA protein, responsible for the excision of the B. subtilis SPβ prophage [32]. CD1231 is also similar to other C. difficile recombinases associated with conjugative transposons. A domain analysis of CD1231 (Fig 1B) identifies the three main structural domains of LSRs and the motifs that connect them: the N-terminal resolvase domain (LSR-NTD) bearing the conserved catalytic nucleophile (Ser at position 10) and additional catalytic residues, followed by a recombinase domain (RD), a zinc β-ribbon domain (ZD) and a coiled coil (CC) motif (Figs 1B and S1). The RD, the ZD and the CC form the C-terminal domain (LSR-CTD); the NTD and CTD are linked by a long α-helix (αE) while a short linker connects the RD to the ZD [22]. In CD1231 as in other LSRs, the CTD is followed by an extension of variable length, which is mostly α-helical (S1 Fig) [22].

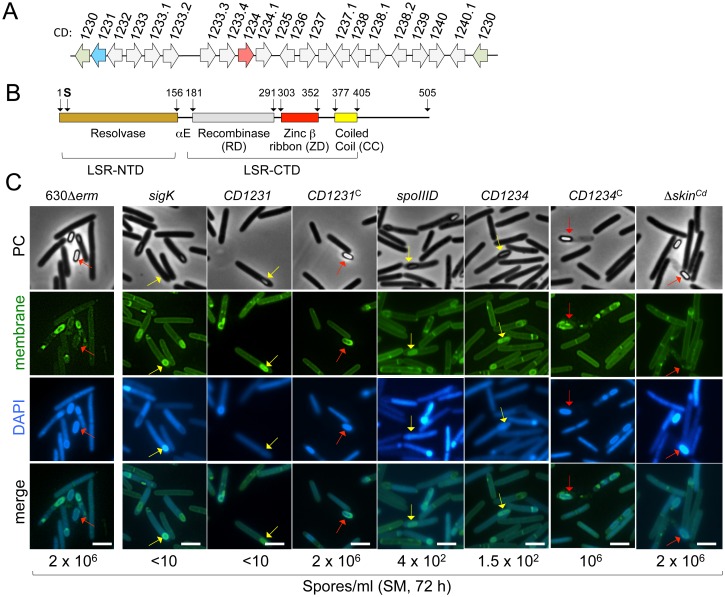

Fig 1. The skinCd gene CD1231, coding for a serine recombinase, is required for sporulation.

A: schematic representation of the sigK-skinCd region of the C. difficile 630Δerm chromosome. The two halves of the sigK gene (5‘ and 3’ part of CD1230) are shown in green, and the CD1231 gene, coding for a protein of the large serine recombinase family is shown in blue. The CD1234 gene is shown in pink. B: domain organization of the CD1231 serine recombinase. The horizontal black line is a linear representation of the amino acid sequence. The three conserved domains identified are color-coded: brown, resolvase domain (PF00239, which forms the N-terminal domain (NTD); grey, recombinase domain (RD; PF07508); red, a zinc ribbon domain (ZD; PF13408); yellow, a coiled-coil (CC) motif. The recombinase domain, the zinc finger and the coiled-coil form the C-terminal domain (CTD). A long α-helix linking the NTD and CTD domains is indicated as αE. The catalytic serine, close to the N-terminal end of the protein, is represented. C: cells of the WT strain 630Δerm, the ΔskinCd, spoIIID, sigK, CD1231 and CD1234 mutants and the complemented strains, CDIP533 and CDIP397, carrying multicopy alleles of CD1231 (CD1231C) or CD1234 (CD1234C) expressed under the control of their native promoters were collected after 24 h of growth in liquid SM, stained with the DNA stain DAPI and the membrane dye MTG and examined by phase contrast and fluorescence microscopy. The red arrows point to phase bright spores and the yellow arrows to phase grey spores. Scale bar, 1μm. The titer of heat resistant spores measured for each strain after 72 h of growth in SM is indicated below the panels. The titer of heat resistant spores at 48 h was 0.75 x 106 for strain 630Δerm and for the ΔskinCd mutant.

In B. subtilis, the excision of the skinBs element occurs in the mother cell, and creates an intact sigK gene, essential for sporulation. Since σK is required for sporulation in C. difficile [15], inactivation of CD1231, which is probably involved in skinCd excision, would cause a block in the process. We constructed a CD1231 mutant (CDIP526) using the Clostron system (S2 Fig) as well as a complemented strain (CDIP533) carrying CD1231 under the control of its promoter (pMTL84121-CD1231; see below). We then examined the morphology of the strains by phase contrast and fluorescence microscopy after 24 h of growth in sporulation medium (SM), and we tested the efficiency of heat-resistant spore formation at 72 h. The 630Δerm strain produced 2 x106 heat-resistant CFU/ml and phase bright spores, either free or still inside the mother cell, were seen (Fig 1C). In contrast, less than 10 heat resistant CFU/ ml were detected for the CD1231 mutant. While some phase gray spores were seen in cultures of the mutant at 24 h, free spores were not detected (Fig 1C). Complementation of the CD1231 mutation restored the wild-type phenotype (Fig 1C). Therefore, inactivation of the CD1231 gene severely impaired sporulation. The phenotype caused by the CD1231 mutation phenocopied that imposed by a sigK mutation in that phase gray, heat-sensitive spores were formed that often were seen in a angle relative to the long axis of the cell (Fig 1C) [16, 17]. Moreover, as found for a sigK mutant, formation of the phase gray spores was not accompanied by loss of viability of the mother cell, as is the case for the wild-type strain [17]. These observations strongly suggest that σK is inactive in this mutant.

Constitutive expression of the CD1231 gene

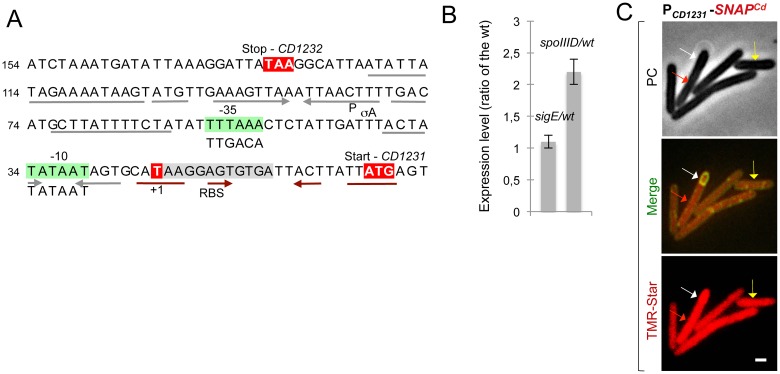

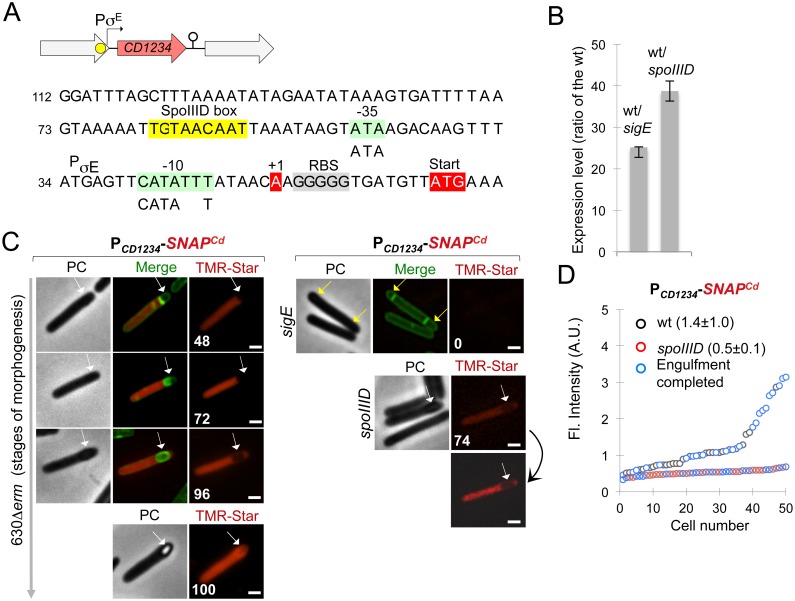

Expression of the spoIVCA gene in B. subtilis is under the dual control of the mother cell proteins σE and SpoIIID leading to the restriction of skinBs excision to this compartment [19, 33]. However, previous transcriptome studies suggested that σE or SpoIIID does not control CD1231 expression in C. difficile [18, 30]. Moreover, qRT-PCR using RNA extracted from SM cultures of the strain 630Δerm, a sigE mutant and a spoIIID mutant did not show variations in the level of CD1231 expression in the sigE mutant and only a slight increase in the spoIIID mutant relative to the wild-type strain (Fig 2B). In our genome-wide mapping of promoters in strain 630Δerm [34], a transcriptional start site (TSS) was found 21 bp upstream of the CD1231 start codon and -35 (TTTAAA) and -10 (TATAAT) sequences for σA-dependent promoters are present upstream of this TSS while no consensus for σE is found (Fig 2A). This suggests that expression of CD1231 is under the control of σA and therefore probably not confined to the mother cell. To test this possibility, we constructed a PCD1231-SNAPCd fusion and this fusion was transferred to the 630Δerm strain. Samples of cultures expressing PCD1231- SNAPCd were collected at 24 h of growth in SM, and the cells doubly labeled with the SNAP substrate TMR-Star and the membrane dye MTG. Expression of PCD1231- SNAPCd was detected in 93% of the vegetative cells scored, consistent with the presence of a σA-type promoter. However, expression of PCD1231-SNAPCd was also detected in sporulating cells in both the forespore and the mother cell (78% of the sporangia) (Fig 2C). Thus, in agreement with the absence of a requirement for σE and SpoIIID for its expression as determined by qRT-PCR, CD1231 is not a mother cell-specific gene.

Fig 2. Constitutive expression of the skinCd gene CD1231.

A: promoter region of the CD1231 gene. The mapped transcriptional start sites (+1, red) [34] and the -10 and -35 promoter elements (green boxes) that match the consensus for σA recognition are indicated. Also represented are the stop codon of CD1232 and the start codon of CD1231 (red). Inverted repeats upstream (grey arrows) and downstream (brown) of the +1 position are indicated as well as a possible RBS overlapping the left arm of these repeats. B: qRT-PCR analysis of CD1231 transcription in strain 630Δerm, and in sigE or spoIIID mutant. RNA was extracted from cells collected 14 h (sigE mutant) or 15 h (spoIIID mutant) after inoculation in liquid SM. Expression is represented as the fold ratio between the indicated mutants and the wild-type (WT). Values are the average ± SD of two independent experiments. C: cells of the C. difficile 630Δerm strain carrying a PCD1231-SNAPCd transcriptional fusion were collected after 24 h of growth in liquid SM, stained with TMR-Star and the membrane dye MTG, and examined by phase contrast (PC) and fluorescence microscopy. The merged images show the overlap between the TMR-Star (red) and MTG (green) channels. The yellow arrow shows a vegetative cell expressing PCD1231-SNAPCd, the white arrow shows expression in the forespore and the red arrow expression in the mother cell. Scale bar, 1 μm.

Control of sigK transcription and σK activity by SpoIIID

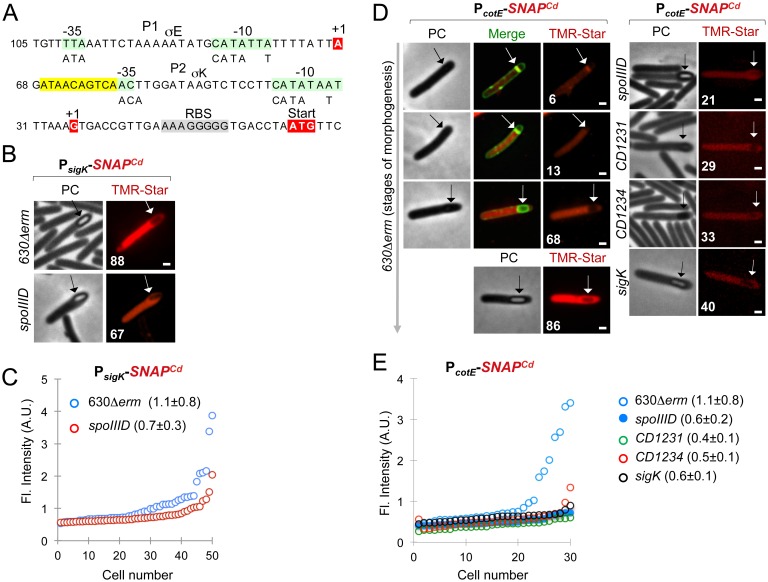

Previous work indicated that the skinCd element is excised from the chromosome only during sporulation [27]. This suggests that a factor is required in addition to CD1231 to trigger excision during sporulation. In a first step to search for this factor, we wanted to establish the requirements for sigK transcription and σK activity. Previous work has shown that SpoIIID is required for sporulation and for the transcription of the sigK gene in C. difficile [16, 18, 30]. Importantly, expression of a skinCd-less version of the sigK gene from a SpoIIID-independent promoter largely bypasses the requirement for SpoIIID for sporulation [30]. While showing that a critical function of SpoIIID in sporulation is to ensure efficient sigK expression, this result does not discard a possible role of SpoIIID in skinCd excision. Here, we examined the effect of a spoIIID mutation on sigK transcription using a PsigK-SNAPCd fusion and on the activity of σK using a fusion of the σK-controlled PcotE to SNAPCd [17]. Two TSSs have been mapped in the sigK promoter region (Fig 3A) [18]. The upstream promoter (P1) matches the consensus for σE recognition, whereas the downstream promoter (P2) matches the consensus for σK recognition [18]. Using the consensus of SpoIIID of B. subtilis [19], a possible SpoIIID binding site is found upstream of P2 and downstream of P1 (Fig 3A). Transcription of sigK was detected in the mother cell of the wild-type strain soon after septation and during engulfment [17], but increased following engulfment completion, when it was detected in 88% of the sporangia (Fig 3B). In contrast, transcription of sigK was detected in only 67% of the spoIIID mutant sporangia in which engulfment was completed (Fig 3B). Moreover, quantification of the fluorescence signal from PsigK-SNAPCd in those cells revealed a reduction of the signal per sporangia, from 1.1±0.8 arbitrary units (A.U.) in the wild-type strain, to 0.7±0.3 A.U. in the spoIIID mutant (Fig 3C). The arrangement of the sigK promoter region suggests that the low level of transcription during engulfment may arise from P1 whereas the main period of sigK transcription could involve utilization of P2 possibly by σE first, then by σK, with the assistance of SpoIIID. P2 may also be involved in the late, positive auto-regulation of σK in cells carrying phase bright spores [17, 18] (see also the Discussion). Thus, following engulfment completion, transcription of sigK is reduced, but not abolished, in the absence of SpoIIID both in terms of the number of cells in which transcription is activated and, although a less pronounced effect, in the level of expression per cell. The reduction in sigK transcription in the spoIIID mutant is in line with earlier results [18, 30].

Fig 3. Control of sigK expression and of σK activity.

A: promoter region of the sigK gene. The transcriptional start sites (+1, red) as previously mapped [34], the -10 and -35 promoter elements (green) that match the consensus for σE or σK recognition (represented below the sequence), the SpoIIID box (yellow), and the start codon of the sigK gene, are indicated. B: microscopy analysis of C. difficile cells carrying a PsigK-SNAPCd fusion in strain 630Δerm and in the spoIIID mutant. The cells collected after 24 h of growth in SM were stained with TMR-Star and examined by phase contrast (PC) and fluorescence microscopy. The morphological stage at which sigK transcription reaches its maximum, concomitant with the appearance with phase gray spores, is illustrated. The position of the forespore is clearly seen in the PC images. The numbers represent the percentage of cells at the indicated stage that show expression of the reporter fusion. C: quantitative analysis of the fluorescence intensity (Fl., in arbitrary units, A.U.) in sporulating cells (as in B) expressing PsigK- SNAPCd. The numbers in the legend represent the average fluorescence intensity ± SD (a minimum of 50 cells were scored). D: microscopy analysis of cells carrying fusions of the σK-dependent cotE promoter to SNAPCd in strain 630Δerm and in the spoIIID, CD1231, CD1234 and sigK mutants. Cells were collected and processed for imaging as indicated in panel B. However, MTG staining was used to visualize the forespore membranes and the stage of sporulation during engulfment; the merged images show the overlap between TMR-star (red) and MTG (green). Note that merged images (MTG/TMR-Star) are not shown whenever the position of the forespore is seen in the PC images. The panels are representative of the expression patterns observed for different sporulation stages, ordered from early to late. For the mutant strains, the morphological stage characteristic of each mutant is shown. The numbers refer to the percentage of cells at the represented stage showing SNAPCd fluorescence. E: quantitative analysis of the fluorescence (Fl.) intensity in the various strains expressing PcotE-SNAPCd. The numbers in the panels are the average fluorescence intensity ± SD (30 cells were analyzed). In B and D, the arrows show the position of developing spores. Scale bar, 1 μm.

As a measure of σK activity, PcotE-driven production of SNAPCd was detected in the mother cell in 6–13% of the wild-type sporangia during engulfment but increased to 68% just after engulfment completion and was seen in 86% of the sporangia when phase bright spores became visible (Fig 3D). Expression of PcotE-SNAPCd was detected in only 40% of the sigK mutant sporangia that reached late stages of morphogenesis to form partially refractile spores, and the average fluorescence signal per sporangia decreased to 0.6±0.1 A.U. (Fig 3E). Importantly, disruption of spoIIID or CD1231 reduced expression of PcotE-SNAPCd to only 21% and 29% of the sporangia that reached late stages of morphogenesis. Moreover, the average fluorescence intensity per cell was of 0.6±0.2 A.U. and 0.4±0.1 A.U. in the spoIIID or CD1231 mutant, respectively as compared to 1.1±0.8 A.U. for the wild-type strain (Fig 3D and 3E). Thus, disruption of sigK, spoIIID, or CD1231 reduced expression of the PcotE-SNAPCd fusion approximately to the same extent. In any event, the increase in σK activity following engulfment completion is not seen in CD1231 and spoIIID mutants, compatible with a role for CD1231 and SpoIIID in the control of σK activity. This strongly suggests that SpoIIID may play a role in skinCd excision.

The cell type-specific excision of skinCd requires SpoIIID

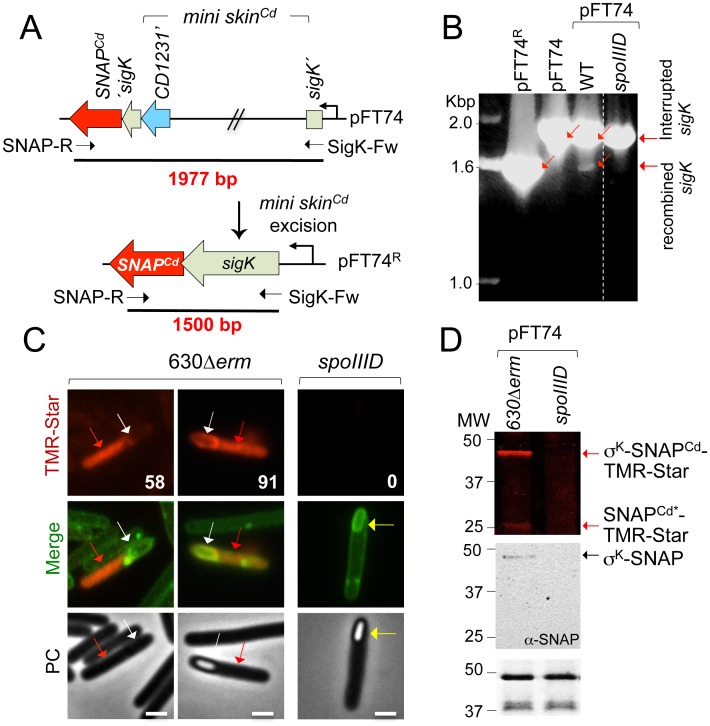

To examine the time and requirements of skinCd excision, we devised an assay to monitor reconstitution of a functional sigK gene in C. difficile. We previously described a plasmid, pFT38, carrying a sigK gene disrupted by a mini-skinCd element bearing a deletion of all the skinCd genes except CD1231 [17]. We modified this plasmid in order to create a translational fusion between the C-terminal moiety of σK and SNAPCd and to remove the 5´-end of CD1231 (i.e., only the chromosomal CD1231 is functional) (Fig 4A). This plasmid, pFT74, was introduced in strain 630Δerm and in the spoIIID mutant. Excision through recombination involving sequences at the ends of the mini-skinCd element reconstitutes the sigK gene (Fig 4A). The recombined sigK in pFT74 named pFT74R was first detected by PCR using an oligonucleotide hybridizing to the 5’ moiety of the sigK gene and a second in the SNAPCd gene: a fragment of 1500 bp is expected upon mini-skinCd excision instead of 1977 bp for pFT74 (Fig 4A). The 1500 bp PCR fragment was detected in strain 630Δerm but not in the spoIIID mutant (Fig 4B) indicating that SpoIIID is necessary for mini-skinCd excision. This is also the case for the chromosomal copy of the skinCd element as described below.

Fig 4. Time of excision of a mini-skinCd element as detected by production of a σK-SNAPCd fusion protein.

A: schematic representation of plasmid pFT74, containing the SNAPCd reporter fused in frame to the 3´-end of sigK. The sigK gene is interrupted by a mini-skinCd element carrying the 3´end of the CD1231 gene (blue). When skinCd excision occurs to form pFT47R, σK-SNAPCd is produced. The size of the inserts before and after recombination is indicated. The primers used for PCR analysis are indicated. B: analysis of skinCd excision by PCR using the primer pair indicated in panel A and DNA extracted from cultures of the strain 630Δerm, and the spoIIID mutant after 24 h of growth in SM. The red arrows point to the recombined sigK and the interrupted gene. pFT74 and pFT74R were used as controls for non-recombined and recombined sigK, respectively. C: fluorescence microscopy analysis of sporulating cells producing σK-SNAPCd in the strain 630Δerm and in the spoIIID mutant. Cells grown in SM were collected at 24 h and stained with the membrane dye MTG and TMR-Star. The red arrows point to the mother cell, and the white arrow to the developing spore. The yellow arrow shows the position of a spore in a spoIIID sporangium. The numbers refer to the percentage of cells at the represented stage showing production of the fusion. Scale bar, 1 μm. D: accumulation of σK-SNAPCd in extracts produced from sporulating cells of the WT and spoIIID mutant. The cells were collected from SM cultures 24 h after inoculation, labeled with the TMR-Star substrate. Proteins in whole cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE, visualized by fluoroimaging or subject to immunoblot analysis with anti-SNAP antibodies. A section of the corresponding Coomassie-stained gel is shown as a loading control. The arrows indicate the position of the TMR-Star-labeled σK-SNAPCd fusion (expected size 47 kDa). The asterisk points to a possible degradation product of σK-SNAPCd (SNAPCd*) of about 25 kDa. The position of molecular mass markers (in kDa) is shown on the left side of the panels.

To gain further insight into the time of excision relative to the course of spore morphogenesis, we monitored production of the σK-SNAPCd translational fusion formed after mini-skinCd excision at the single cell level by fluorescence microscopy (Fig 4C). Production of σK-SNAPCd was detected only in the mother cell in 58% of the wild-type sporangia in which spores were not yet discernible in the mother cell by phase contrast microscopy but that were close to or just after engulfment completion as judged from the MTG staining pattern (membranes almost fused or fused) (Fig 4C). However, σK-SNAPCd was detected in 91% of the sporangia in which partially phase bright or phase bright spores were visible by phase contrast microscopy (Fig 4C). This parallels the pattern of sigK transcription and σK activity [17] and suggests that σK is active as soon as it is produced after skinCd excision. In contrast, no accumulation of σK-SNAPCd was detected in the spoIIID mutant (Fig 4C) even if the sigK gene remains expressed in this mutant (Fig 3A). σK-SNAPCd (47 kDa) was detected by Western blotting using anti-SNAP antibodies and by fluorimaging in crude extracts of strain 630Δerm but not in extracts prepared from the spoIIID mutant (Fig 4D). These results strongly suggest that SpoIIID is required for skinCd excision in C. difficile as also observed for B. subtilis. Moreover, since the main period of sigK transcription, σK accumulation and σK activity appear to coincide during the course of morphogenesis, skinCd excision and sigK transcription seem to concur to delay the onset of σK activity.

CD1234 is a mother cell-specific skinCd gene

Given that skinCd excision did not take place in vegetative cells or in the forespore in spite of CD1231 expression in these cells and the suspected role of SpoIIID in controlling σK activity via skinCd excision, we inferred that a factor probably encoded within skinCd and produced under the joint control of σE and SpoIIID could modulate CD1231 synthesis and activity. Among the 19 skinCd genes, only CD1234 (Fig 5A) was down-regulated in a sigE and in a spoIIID mutant in transcriptome analyses [18, 30]. CD1234 codes for a small protein of 72 amino acids, with a predicted pI of 5.5 and no significant similarity to proteins found in databases. We confirmed by qRT-PCR using RNA extracted from SM cultures that CD1234 expression decreased 25-fold and 40-fold in a sigE and in a spoIIID mutant, respectively as compared to the wild-type strain (Fig 5B). We mapped a TSS 14 bp upstream of the start codon of CD1234, and a consensus sequence for σE recognition was detected upstream of this TSS [18]. Using the SpoIIID consensus sequence of B. subtilis [19], we also identified a putative SpoIIID binding motif (TGTAACAAT) centered 46 bp upstream of the CD1234 TSS (Fig 5A) in agreement with the positive control of CD1234 expression by SpoIIID.

Fig 5. CD1234 is a mother cell-specific gene.

A: the panel represents the region of the CD1234 gene within the skinCd element (top) and the sequence of its promoter region (bottom). The transcriptional start site (+1, red), the -10 and -35 promoter elements (green) that match the consensus for the σE binding (represented below the sequence), and a putative SpoIIID binding site (yellow) are represented. B: qRT-PCR analysis of CD1234 transcription in strain 630Δerm (WT), and in sigE or spoIIID mutant. RNA was extracted from cells collected 14 h (sigE mutant) and 15 h (spoIIID mutant) after inoculation in liquid SM. Expression is represented as the fold ratio between the WT strain and the indicated mutants. Values are the average ± SD of two independent experiments. C: microscopy analysis of cells of the 630Δerm strain and of the sigE and spoIIID mutants carrying a PCD1234-SNAPCd transcriptional fusion. The cells were collected 24 h after inoculation in liquid SM, stained with TMR-Star and the membrane dye MTG, and examined by phase contrast (PC) and fluorescence microscopy. Merged images (MTG/TMR-Star) are not shown whenever the position of the forespore is clearly seen in the phase contrast images. The panels are representative of the expression patterns observed for different stages of sporulation, ordered from early to late. For the mutant strains, the morphological stage characteristic of each mutant is shown. The numbers in the panels refer to the percentage of cells at the represented stage showing SNAPCd fluorescence. The white arrows show the position of the developing spore in WT or spoIIID sporangia, and the yellow arrows the two-forespore compartments characteristic of a sigE mutant (disporic phenotype). Note that the TMR-Star panel for the spoIIID mutant is shown repeated with enhanced contrast (the two panels linked by a curved arrow) so that the lack of signal in the forespore is clearly seen. Scale bar, 1 μm. D: quantitative analysis of the fluorescence intensity in sporulating cells of the strains shown in C. The numbers in the legend represent the average ± SD of fluorescence intensity (50 cells were scored in each case) in the WT or spoIIID mutant. No difference was observed for sporangia before (black symbol in the curve for the WT and red symbols in the curve for the spoIIID mutant) or after engulfment completion (blue symbols in both curves).

To examine the compartment and time of CD1234 expression during sporulation, we constructed a PCD1234-SNAPCd transcriptional fusion. This fusion was transferred by conjugation into the 630Δerm strain and the sigE or spoIIID mutant. In the wild-type strain, SNAP production confined to the mother cell, was detected in 48% and 72% of the cells just after asymmetric division and during engulfment, respectively and persisted until late stages in development, when phase bright spores were seen (Fig 5C). SNAPCd production was eliminated by mutation of sigE (Fig 5C) while the average intensity of the SNAPCd-TMR signal decreased from 1.4±1 in the 630Δerm strain to 0.5±0.1 in a spoIIID mutant (Fig 5D). Together, these results indicate that CD1234 is a mother cell-specific gene expressed under the joint control of σE and SpoIIID.

The CD1234 gene is required for sporulation

To investigate the role of CD1234 in sporulation, we constructed a CD1234 mutant, CDIP396, using the Clostron system (S2 Fig). A complemented strain, CDIP397, carrying the CD1234 gene expressed under the control of its native promoter was also constructed. We examined the morphology of the CD1234 mutant using phase contrast and fluorescence microscopy. Some phase bright or partially phase bright spores were present in cultures of the CD1234 mutant but free spores were not detected. The mutant formed only 1.5 x 102 heat-resistant spores/ml of culture at 72 h of growth in SM (i.e. 104 less than the wild-type) (Fig 1C). Importantly, the wild-type phenotype was restored in the complemented strain (Fig 1C). Thus, inactivation of the CD1234 gene strongly impaired sporulation. Nevertheless, the CD1234 mutant like the spoIIID mutant was not as severely affected in sporulation as the sigE and sigK mutants [16, 17] or CD1231 mutant (Fig 1C).

CD1231 and CD1234 are required for σK activity

Since both CD1231 and CD1234 are likely required for skinCd excision, a prerequisite for σK activation, we tested the impact of CD1231 and CD1234 inactivation on the expression of σK or σE targets using qRT-PCR (Table 1). We extracted RNA from strain 630Δerm, the CD1231 and CD1234 mutants and the complemented strains after 24 h of growth in SM, a time where σK target genes are highly expressed [18]. As expected, expression of CD1231 and CD1234 was strongly reduced in the CD1231 and CD1234 mutants, respectively (Table 1). The expression of three σE targets (spoIIIAA, spoIVA, spoIIID) was not significantly altered in the CD1231 and CD1234 mutants as compared to the wild-type strain. In sharp contrast, expression of six σK target genes strongly decreased in the CD1231 or CD1234 mutant compared to the wild-type strain (Table 1), as observed previously for a sigK mutant [18]. CD1231 and CD1234 were about 10-fold more expressed in the CD1231 (pMTL84121-CD1231) and CD1234 (pMTL84121-CD1234) strains than in 630Δerm (Table 1), and expression of the σK target genes was fully or partially restored in these strains. Accordingly, expression of a PcotE-SNAPCd fusion decreased in a CD1231 mutant compared to strain 630Δerm as described above and was reduced in the CD1234 mutant. Only 33% of the sporangia that reached late stages of development expressed the fusion when CD1234 is inactivated compared to 86% for the wild-type strain (Fig 3D). Moreover, the average intensity of the fluorescence signal decreased from 1.1±0.8 A.U. (WT) to 0.5±0.1 (CD1234), similar to the intensity seen for the CD1231 mutant (Fig 3E). In conclusion, expression of σK-dependent but not of σE-dependent genes requires CD1231 and CD1234 as expected for proteins involved in sigK reconstruction through skinCd excision.

Table 1. Effect of CD1231 or CD1234 inactivation on the expression of σK or σE targets.

| Fold change | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | 630Δerm/ CD1231 | 630Δerm/ CD1231C | 630Δerm/ CD1234 | 630Δerm/ CD1234 C |

| CD1231 | 11.5 +/-1.5 | 0.1 +/-0.01 | 1.24 +/-0.02 | 1.3 +/-0.03 |

| σE targets | ||||

| spoIIIAA | 1.3 +/-0.3 | ND | 0.85 +/- 0.25 | ND |

| spoIVA | 2.9 +/-1 | ND | 1.7 +/- 0.1 | ND |

| spoIIID | 2.45 +/-0.5 | ND | 1.3 +/- 0.7 | ND |

| sigK | 167 +/-12 | 2.55 +/- 0.1 | 206 +/-32 | 1.9 +/- 0.1 |

| CD1234 | 1.85 +/- 0.05 | 2 +/- 0.1 | 545 +/-140 | 0.11 +/-0.01 |

| σK targets | ||||

| sleC | 95 +/- 19 | 4.75 +/-1.25 | 86 +/- 20 | 3.75 +/- 0.25 |

| cotBC | 2045 +/- 49 | 9 +/- 1 | 1650 +/-430 | 1 +/- 0.4 |

| bclA1 | 88 +/- 4.5 | 2.6 +/- 1.3 | 53 +/- 6 | 2.8 +/- 1.1 |

| cotE | 149 +/-5 | 8.5 +/- 3 | 89 +/- 8 | 6 +/-0.2 |

| CD1133 | 31 +/- 2 | 2.7 +/- 0.8 | 30 +/-1 | 2.2 +/-0.8 |

| CD3580 | 70 +/-15 | 2.9 +/- 0.9 | 50 +/-5 | 3 +/- 0.5 |

Total RNAs were extracted from C. difficile 630Δerm strain, the CD1231 and CD1234 mutants, and the complementation strains CD1231C (CD1231 mutant with pMTL84121-CD1231) and CD1234C (CD1234 mutant with pMTL84121-CD1234) after 24 h of growth in SM medium. After reverse transcription, specific cDNAs were quantified by qRT-PCR using the DNApolIII gene for normalization. The results presented correspond to the mean of at least two independent experiments.

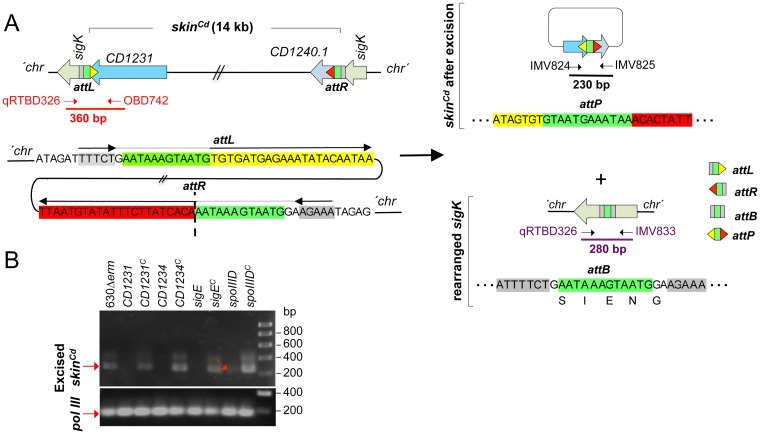

skinCd excision during growth and sporulation requires both CD1231 and CD1234

The temporal control of skinCd excision and its confinement to the terminal mother cell may thus require the σE- and SpoIIID-controlled gene, CD1234. We tested excision of the chromosomal skinCd in strain 630Δerm and in the CD1231, CD1234, sigE and spoIIID mutants (Fig 6). In B. subtilis, skinBs excision occurs within two 5 bp inverted repeats that flank an imperfect 21 bp repeat [35]. In C. difficile, excision is expected to occur by means of a recombination event involving attL and attR (by analogy with the sequences involved in phage excision) at the left and right ends of skinCd (Fig 6A) [27]. As in B. subtilis, attL and attR consist of two half-sites formed by a 5 bp inverted repeat external to a longer 22 bp imperfect inverted repeat (Fig 6A) and of two conserved 12 bp motifs, one in attL and one in attR, within which recombination take place (in green in Fig 6A). The intervening DNA is excised as a circular molecule carrying attP (by analogy with sequences responsible for phage integration), leaving behind a chromosomal attB site (analogous to prophage insertion sequences in the bacterial chromosome) (Fig 6A).

Fig 6. Requirements for skinCd excision in C. difficile.

A: schematic representation of skinCd excision from the 630Δerm chromosome and of the recombination products derived from the process. The attL (the half-sites are represented by the green box and the yellow triangle) and attR (the green box and the red triangle) in the chromosome, attP in the excised skinCd (half-sites correspond to yellow and red triangles) and attB in the chromosome (green and grey boxes) are represented. The horizontal arrows represent inverted repeats. The vertical dashed line represents the point of junction of the sequenced following recombination. The oligonucleotides used to amplify the 5’ junction of skinCd (OBD742-qRTBD326), the reconstructed sigK gene (qRTBD326-IMV833) and the circularized skinCd (IMV824-IMV825) are indicated, as well as the expected size of the respective products. B: detection of skinCd excision in different strains by PCR using primers IMV824 and IMV825 and DNA extracted from the indicated strains grown in liquid SM medium for 24 h. CD1231C denotes the CD1231 mutant complemented with pMTL84121-CD1231 and CD1234C the CD1234 mutant complemented with pMTL84121-CD1234. sigEC and spoIIIDC correspond to the sigE or spoIIID mutant complemented with pMTL84121-sigE or pMTL84121-spoIIID, respectively.

The excised circular element obtained after excision of skinCd can be monitored by PCR using primers annealing upstream and downstream of attP (Fig 6A). During sporulation, skinCd excision was detected in strain 630Δerm (Fig 6B, lane 1), but not in the CD1231 (lane 2), CD1234 (lane 4) and sigE (lane 6) mutants. A very faint band corresponding to the excised skinCd was detected in the spoIIID mutant (lane 8, red arrow and red dot). Plasmids bearing the disrupted chromosomal genes restored skinCd excision to all mutants (Fig 6B, lane 3, 5, 7, 9). Thus, skinCd excision during sporulation requires both CD1231 and CD1234. Moreover, the results confirm the key role of SpoIIID and σE in skin excision likely through their control of the cell type-specific production of CD1234.

To test whether expression of CD1234 could result in skinCd excision during vegetative growth, we constructed a plasmid carrying CD1234 under the control of an ATc-inducible promoter (pDIA6103-PtetCD1234). This plasmid or the empty vector pDIA6103 were introduced into strain 630Δerm and the sigE, spoIIID, CD1231 and CD1234 mutants. The resulting strains were grown for 4 h in TY medium. Following induction of CD1234 expression, the cells were either plated onto BHI or harvested for DNA extraction. qPCR was then performed with 2 primer pairs, one corresponding to DNApolIII as a control and the second to sigK on both sides of attB for the detection of skinCd excision. The ΔCt (CtsigK-CtpolIII) was determined for each strain carrying either pDIA6103 or pDIA6103-PtetCD1234. The ΔCt was >10 for all strains containing pDIA6103. Interestingly, the ΔCt was reduced to < 1 for all strains containing pDIA6103-Ptet-CD1234 with the exception of the CD1231 mutant where a ΔCt of 18 was observed, as was also the case for the strain CD1231 (pDIA6103) (Table 2). In parallel, chromosomal DNA was extracted from 8 independent clones obtained after seeding BHI plates with samples from the cultures of the different strains carrying pDIA6103-PtetCD1234. For each clone, we tested the presence of skinCd in the chromosome by PCR amplification of the 5’ junction of the skin (attL) using one oligonucleotide located in the 3’ part of CD1231 and the second in sigK (Fig 6A). While the skinCd/chromosome junction was detected in only 1 out of 8 clones tested for strains 630Δerm, sigE, spoIIID or CD1234, this junction was amplified for the 8 clones of the CD1231 mutant (Table 2). This confirmed that skinCd was excised after induction of CD1234 expression during growth of the wild-type strain and of the sigE, spoIIID and CD1234 mutants. In contrast, skinCd remained integrated in the CD1231 mutant under similar conditions.

Table 2. Excision of skinCd during growth in strains producing CD1234 under Ptet control.

| ΔCt = CtsigK-CtpolIII | Detection of skinCd junction by PCR | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | pDIA6103 | pDIA6103-Ptet-CD1234 | |

| 630Δerm | 10.9+/-0.5 | 0.8+/-0.4 | 0/8 |

| sigE::erm | 17.9+/-0.5 | 0.6+/-0.5 | 1/8 |

| spoIIID::erm | 16.3+/-0.15 | 0.85+/-0.35 | 1/8 |

| CD1231::erm | 18.3+/-0.25 | 18+/-1 | 8/8 |

| CD1234::erm | 17.9+/-0.25 | 0.65+/-0.35 | 1/8 |

Strains 630Δerm, sigE::erm, spoIIID::erm, CD1234::erm and CD1231::erm containing either pDIA6103 or pDIA6103-Ptet-CD1234 were grown in TY medium for 4 h at which time ATc (100 ng/ml) was added. After 2 h of induction, cells were serially diluted and plated on BHI or collected and DNA extracted. qPCR was performed on with 2 primer pairs: one corresponding to DNApolIII as a control and the second to sigK on both sides of the skin insertion site (qRTBD325-qRTBD326). Chromosomal DNA extracted from 8 independent clones obtained after plating the cultures on BHI was used to amplify the 5’ junction of the skin using one primer in sigK (qRTBD326) and one in CD1231 (OBD742) (See Fig 6A). The number of positive clones among the eight tested is indicated.

In conclusion, these results indicate that during C. difficile growth: i) excision occurs if and only if CD1234 is produced; ii) under these conditions skinCd excision is independent of σE and SpoIIID; and iii) excision is absolutely dependent on the skinCd CD1231 recombinase, even if CD1234 is induced. Together, these results indicate that both CD1231 and CD1234 are necessary for skinCd excision in C. difficile.

Evidence that CD1231 and CD1234 directly interact

Since CD1231 was not specifically transcribed during sporulation and its expression was not altered in a CD1234 background (Table 1), we reasoned that CD1234 could post-transcriptionally control the synthesis or activity of CD1231. The integration reaction catalyzed by the LSRs is unidirectional, in that excision often requires an additional recombination directionality factor (RDF) that modulates the LSR activity by direct protein-protein interactions [22, 36, 37]. We therefore tested whether CD1231 and CD1234 could interact using pull-down assays. Whole cell extracts prepared from E. coli BL21(DE3) strains producing separately CD1234-His6 and CD1231-Strep or co-producing the two proteins under the control of PT7lac were prepared. None of the proteins was detected by Coomassie staining, but they were detected by immunoblotting with antibodies to their C-terminal tags (S4A and S4B Fig). The extracts were then incubated with Ni2+-NTA agarose beads, and following washing and elution, the bound proteins were identified by immunoblotting. While a protein of about 30 kDa recognized by the Strep-tag antibody seems to bind non-specifically to the beads, the full length CD1231-Strep as well as two probable degradation products, of about 37 and 40 kDa, were only detected in the presence of CD1234-His6 (S4B Fig). The two likely degradation fragments of CD1231-Strep may contain the CTD domain followed by the C-terminal extension (residues 405–505) consistent with the existence of a protease-sensitive site just downstream of the NTD in the recombinases from phages C31 and Bxb1 and from transposon TnpX [22, 38] (S4D Fig). These fragments may be retained by the Ni2+ column because they bind to the full-length CD1231-Strep recombinase or to CD1234-His6 (S4D Fig). In a different set of experiments, full-length CD1231-Strep was retained by the beads when these were pre-incubated with extracts prepared from BL21(DE3) cells producing CD1234-His6 and not Tgl-His6, an unrelated spore-associated protein from B. subtilis [39, 40], which accumulated to much higher levels than CD1234-His6 (S4C Fig). Together, these results indicate that CD1234 and CD1231 were part of a complex that formed in E. coli and suggest that CD1234 might control the activity of CD1231 by direct interaction.

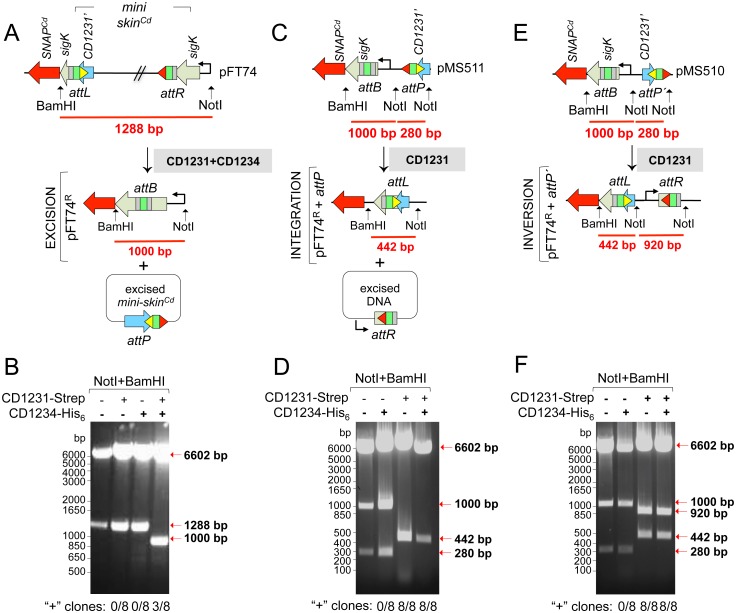

CD1231 and CD1234 are necessary and sufficient for skinCd excision in E. coli

To test whether CD1234 and CD1231 were sufficient for skinCd excision, we used a heterologous host E. coli. The plasmid pFT74 carrying a mini skinCd element integrated into sigK was introduced in E. coli carrying plasmids for expression of CD1231, CD1234 or the co-expression of both genes. The cells were first induced to produce CD1231, CD1234 or both. The plasmid pFT74 was then purified and examined for the recombination reaction by digestion with BamHI and NotI (Fig 7A). Digestion of the resulting recombined plasmid obtained after mini skinCd excision, termed pFT74R, with BamHI and NotI should produce a fragment of 1000 bp as compared to a fragment of 1288 bp for the parental plasmid carrying the mini-skin (pFT74). A fragment of 1000 bp was not isolated from cells producing neither CD1234 alone nor CD1231 alone or a mutant allele of CD1231 in which the putative catalytic serine in the NTD was changed to an alanine (S10A) (Figs 1B, 7B and S5). By contrast, pFT74R was detected in cells in which both proteins were produced (Fig 7B). Together, these results show that CD1231 requires CD1234 as an auxiliary factor for the recombination reaction between attL and attR that results in skinCd excision.

Fig 7. Detection of recombinase activity in E. coli.

E. coli cells were transformed with plasmids pFT74 (A) or pFT74R-attP carrying a skinCd-less sigK gene and attP in both possible orientations (C and E). The resulting strains were then transformed with plasmids containing the CD1231-Strep, CD1234-His6 or both genes (“+” signs) under the control of an IPTG inducible promoter. A, C and E: schematic representation of the recombination event (skinCd excision in A, skinCd integration in C and DNA inversion in E), the expected recombination products and the size of the intact and recombined inserts between the BamHI and NotI sites. attP´denotes an inverted attP site. B, D and F: analysis of the recombinant events following pFT74 or pFT74R-attP recovery from E. coli strains producing CD1231-Strep, CD1234-His6 or both genes (“+” signs) and digestion with BamHI and NotI. pFT74 and pFT74R+attP from strains that did not produce CD1231-Strep or CD1234-His6 were used as controls for non-recombined and recombined sigK, respectively. The size of molecular marker (in bp) is indicated on the left side of the panels. The “+” sign at the bottom of the panels indicate clones where the expected recombination event has occurred (8 clones were analyzed).

CD1231 is sufficient for skinCd integration in E. coli

While both CD1231 and CD1234 are required for skinCd excision in E. coli, we also wanted to test the involvement of these proteins in integration reactions. With that purpose, the attP site of the prophage-like element was inserted into pFT74R, which already contains the integration sequence attB as the result of the excision reaction (Fig 7A). Two plasmids were constructed, one with attP and attB in the same orientation (pMS511; Fig 7C) and one with attB and attP in opposite orientation (attP´ in pMS510; Fig 7E). These plasmids were introduced in E. coli cells carrying the plasmids for expression of CD1231, CD1234 or both. Cells were induced to produce CD1231, CD1234 or both and then the plasmids were purified and examined for recombination events between attP and attB by digestion with BamHI and NotI. Two types of recombination events serve as readouts for the ability of CD1231 to catalyze DNA integration. A recombination event between attP and attB should result in the removal of the intervening DNA for pMS511 (Fig 7C) or in the inversion of the intervening DNA in the case of pMS510 (Fig 7E). We showed that CD1231 is necessary and sufficient for both types of recombination events involving attP and attB (Fig 7D and 7F). No recombined products of pMS510 or pMS511 were retrieved when the catalytically inactive CD1231 bearing the S10A substitution was produced, alone or together with CD1234 (S5 Fig).

These results showed that CD1231 is sufficient for the integration event that results from the recombination between attP and attB, but requires CD1234 for the excision event that results from the recombination reaction involving attL and attR. Thus, CD1234 is a recombination directionality factor (RDF) assisting CD1231 in skinCd excision.

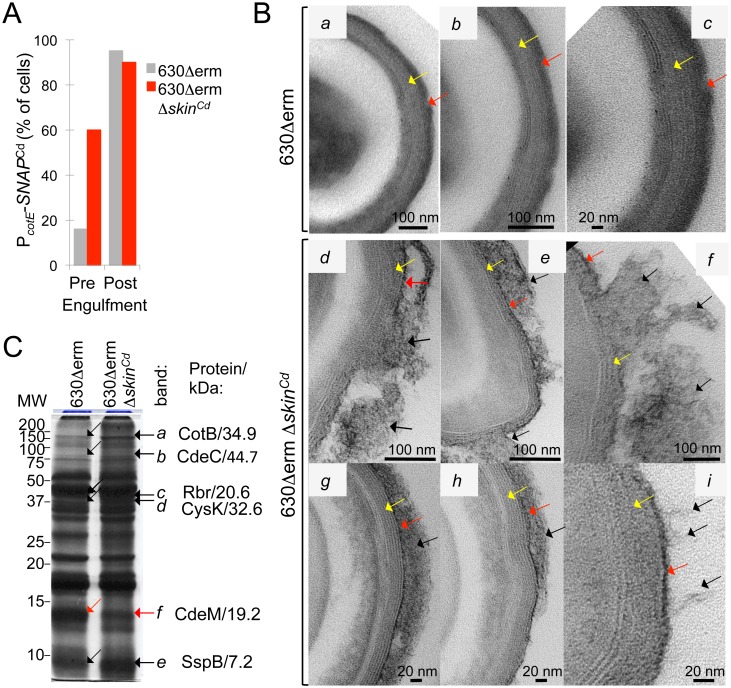

Deletion of the skinCd element causes premature activity of σK

While the regulated excision of skinCd has been suggested as a critical mechanism for efficient sporulation in C. difficile [17, 27], a more recent study suggests that skinCd is not essential for the formation of heat-resistant spores in this organism [30]. However, skinCd excision controls the onset of σK activity. The deletion of the skin in a pro-less sigK strain in B. subtilis imposes changes in the mother cell line of gene expression leading to altered spore structure and functional properties, while the final titer of spores formed is reduced compared to the wild-type [41, 42]. To analyze more precisely the involvement of skinCd in sporulation, we took advantage of the 630Δerm, which expressed CD1234 under Ptet control, to obtain a congenic derivative of strain 630Δerm lacking skinCd (summarized in S6A Fig). Addition of ATc during growth led to skinCd excision and after plating of the cells, DNA was extracted from isolated colonies. We identified several clones that carried a reconstructed sigK gene (S6B Fig, lane 1) but lacked the 5’ junction of skinCd in the chromosome (S6B Fig, lane 2) and the excised form of skinCd that was lost after cellular division (S6B Fig, lane 3). In a second step, a clone carrying an intact sigK gene was cured of the pDIA6103-PtetCD1234 plasmid by successive cycles of growth and dilution in TY medium. After plating, Tm-sensitive clones that had lost pDIA6103-PtetCD1234 were isolated. One clone was named 630Δerm ΔskinCd. Phase contrast microscopy experiments revealed the presence of free spores in both the 630Δerm and 630Δerm ΔskinCd strains (Fig 1C) and the titer of heat resistant spores measured 48 h and 72 h after inoculation in SM medium was almost identical for both strains (Fig 1C). Moreover, the percentage of sporulation measured for the two strains at 12 h (0.4% for 630Δerm and 0.3% for 630Δerm Δskin), 18 h (1.6% and 1.1%) and 24 h (6.4% and 5.4%) following inoculation into SM also did not differ significantly. Thus, in agreement with the previous results using a skinCd-less sigK gene expressed from a SpoIIID-independent promoter [30], deletion of skinCd did not appear to affect the final titer of spores and the kinetics of sporulation.

We then analyzed transcription of sigK and of σK target genes by qRT-PCR in the 630Δerm and 630Δerm ΔskinCd strains. We first harvested the cultures between 10 h and 24 h of growth in SM. After RNA extraction, we tested the expression of sigK using oligonucleotides located on both sides of the skinCd insertion into sigK and of σK target genes. The results showed that the expression of sigK and of several sigK targets (cotE, cotBC, sleC, cdeC, bclA1 and bclA3) was higher in the Δskin strain than in the 630Δerm strain (S2 Table). Lastly, we monitored the activity of σK at the single cell level using a PcotE-SNAPCd transcriptional fusion in the wild-type and ΔskinCd background. Fluorescence microscopy revealed that the signal intensity from the accumulation of TMR-Star-labeled SNAPCd did not differ significantly between wild-type and ΔskinCd sporangia, before or after engulfment completion. Strikingly, however, the ΔskinCd mutation increased the fraction of cells that showed PcotE-SNAPCd expression and hence σK activity, prior to engulfment completion, from 20% (WT) to 60% (ΔskinCd) (Fig 8A). Thus, expression of a skinCd-less sigK gene from its native promoter results in premature σK activity.

Fig 8. skinCd controls the time of σK activation and the fidelity of morphogenesis.

A: quantitative analysis of the cells with fluorescence before and after the completion of engulfment in C. difficile cells carrying the PcotE-SNAPCd fusion (σK-responsive) in strain 630Δerm and 630Δerm ΔskinCd. SNAPCd production was monitored as described in the legend for fig 3. B: purified spores were processed for imaging by transmission electron microscopy. Sections showing details of the spore surface layers for representative specimens are shown (the entire spores are shown in S7 Fig). The yellow arrow indicates the lamellar, inner structure of the coat, whereas the red arrow points to the more electrondense surface layer. The black arrows indicate material peeling off the surface of the spores. C: spores of the 630Δerm and 630Δerm ΔskinCd strains were purified by density gradient centrifugation, the spore surface proteins extracted and resolved by 15% SDS-PAGE. Bands a to d and e show increased representation in spores of the ΔskinCd strain, whereas band f shows reduced representation in ΔskinCd spores as compared to the 630Δerm. The proteins identified in these bands by mass spectrometry are indicated, together with their predicted molecular weight.

Deletion of the skinCd element in strain 630Δerm affects the assembly of the spore surface layers

Activation of σK in B. subtilis is tightly linked to engulfment completion, and mutations that cause its premature activation result in alterations in the properties of the resulting spores [41, 42]. σK plays an important role in the assembly of the spore coat [16, 17] and because σK was active prior to engulfment completion in a larger fraction of the 630Δerm ΔskinCd sporangia as compared to the 630Δerm strain, we examined ultrastructure and the polypeptide composition of the spore surface layers in the two strains. Spores were density gradient purified from cultures of the 630Δerm and 630Δerm ΔskinCd strains, and processed for electron microscopy. Under our conditions, spores of the 630Δerm strain showed a more internal lamellar coat (Fig 8B, yellow arrows in panels a to c), covered by a more external electrondense layer (red arrows); this layer had a uniform and compact appearance around the entire spore (Figs 8B and S7; see also [17]). It may correspond to an exosporium-like layer, which in C. difficile seems to be closely apposed to the underlying coat ([3]; see also below). In contrast, the electrondense outer layer was less compacted in spores of the ΔskinCd strain, and absent in some sections (Fig 8B, black arrows in panels d to i). The disorganization of the outer layer presumably allowed the visualization of a thin electrondense layer forming the edge of the lamellar coat and in close apposition to it (Fig 8B, red arrows in panels d to i). However, this thin layer was missing in some sections and material from the inner lamellar layer appeared to peel off the spore in those sections (Fig 8B, black arrows in panels d and f). Overall, the lamellar coat layer also appeared to be less dense, making its structural organization more apparent (Fig 8B, d to i and S7 Fig). Spore surface proteins from both the coat and exosporium layers were extracted from spores of the 630Δerm and ΔskinCd strains and resolved by SDS-PAGE. Several proteins showed increased extractability from spores of the ΔskinCd strain relative to the wild-type strain (Fig 8C, black arrows, bands a through d and e), whereas a protein of about 12 kDa (red arrow, band f) showed reduced extractability. Mass spectrometry analysis indicates that band a (size close to 200 kDa) contains CotB, whereas band b (size around 80 kDa) contains CdeC. Because the predicted sizes of CotB and CdeC are 34.9 kDa and 44.7 kDa, respectively, these two species may represent cross-linked products of these proteins. CotB and CdeC are likely critical determinants for the assembly of the spore exosporium [3]. Rubrerythrin (Rbr) with a predicted size of 20.6 kDa and CysK, with a predicted size of 32.6 kDa, are detected in bands c and d, at about 37 kDa (Fig 8C). At least Rbr, found in a band of about twice its predicted molecular weight, may form cross-linked homodimers, or be cross-linked to a protein of about 20 kDa. In contrast, a likely proteolytic fragment of the 19.2 kDa-exosporium protein CdeM, shows decreased representation or extractability in the mutant (Fig 8C, band f). The alterations in the assembly of CotB, CdeC and CdeM may explain at least in part the morphology of the outer spore layers in the ΔskinCd strain (Fig 8B); possibly, the Δskin deletion affects mainly the assembly of the exosporium-like layer that in C. difficile seems to be juxtaposed to the coat, while the morphological alterations seem at the level of the coat may be in part a consequence of a misassembled exosporium-like layer. The increased representation of SspB (a forespore-specific protein) [18] may indicate that the spores of the mutant are more permeable or more sensitive to the extraction procedure (Fig 8C, band e). In toto, we conclude that deletion of skinCd affects the assembly of the C. difficile spore surface layers. The alterations in the assembly of the spore coat and of a more external possible exosporium-like layer are most likely due to the premature activity of σK in 630Δerm ΔskinCd sporangia.

Discussion

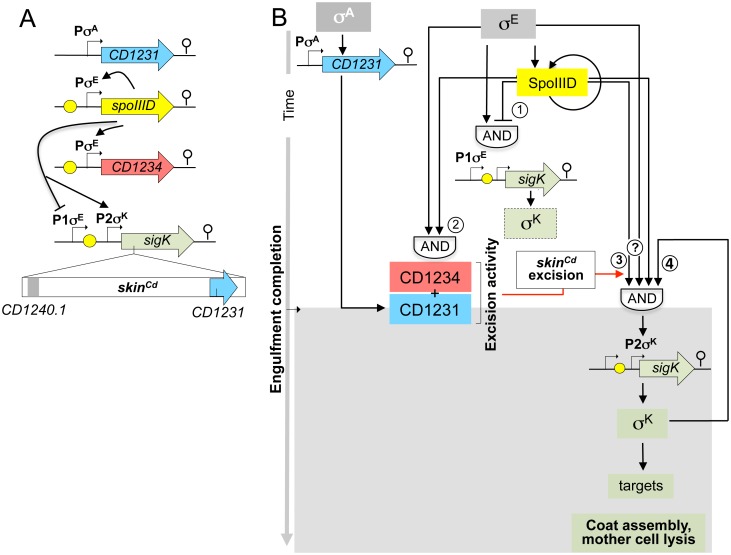

The mother cell-specific excision of the skin element, in either B. subtilis or C. difficile, is essential for the production of a functional sigK gene. In B. subtilis, expression of the gene coding for SpoIVCA, the LSR responsible for skinBs excision is under the joint control of σE and SpoIIID [33]. Hence, skinBs excision is restricted to the terminal mother cell. Excision of the skinCd element is absolutely dependent on CD1231 encoding a SpoIVCA homologue, but expression of this gene is not restricted to the mother cell. Rather, CD1231 is transcribed from a σA-dependent promoter and is expressed in vegetative cells and during sporulation in both compartments. An important finding of the present investigation is that excision of skinCd requires, in addition to CD1231, the product of a gene, CD1234, whose expression is under the control of both σE and SpoIIID (Fig 9). It is the requirement for CD1234 that restricts skinCd excision to the mother cell. However, the inactivation of CD1234 or SpoIIID does not reduce sporulation to the level observed for the CD1231 or sigK gene disruption. CD1234 and SpoIIID thus appear less crucial for sporulation than σK or the catalytic function of the LSR, CD1231. It seems possible that CD1231 occasionally performs excision of skinCd without CD1234. Nevertheless, the normal requirement of CD1234 for skinCd excision in C. difficile is paralleled by its requirement for the CD1231-dependent excision of a mini-skinCd in a heterologous host, E. coli but conversely, CD1234 is not required for the CD1231-dependent skinCd integration. Thus, our recombination assays show that CD1234 is a RDF [22, 32, 37]. RDFs likely stimulate formation of the synapse complex between attL and attR by competing for inhibitory interactions involving the CC motifs of LSRs or inhibit formation or otherwise destabilize the synaptic complex formed between attB and attP possibly by stabilizing the auto-inhibitory activity of the CC motifs in this complex [22, 37]. Accordingly, the RDFs interact with the recombinase in solution, in line with our observation that CD1231 and CD1234 are part of a complex that formed in E. coli. Both structural studies and the isolation of mutations close or within the CC motif of the ϕC31 LSR that allows it to recombine attL and attR in the absence of the cognate RDF, suggest binding of the CC motifs by the RDF [22, 37]. More studies are needed to unravel the mechanism by which CD1234 cooperates with the CD1231 LSR to control skinCd excision. RDFs have been identified for several LSRs. However, they do not share significant sequence similarity and most of them appear to be small, basic proteins. In contrast, CD1234 is acidic like SprB, the RDF of phage SPβ [32]. SprB is required for the SprA recombinase-mediated excision of phage SPβ. A RDF assisting SpoIVCA in the excision of skinBs has not been identified, but the function of the skinBs-encoded genes has not been inspected individually.

Fig 9. The sporulation network leading to skinCd excision and σK activation in C. difficile.

A: schematic representation of the genes involved in skinCd excision and σK activation in C. difficile. Bent arrows show the promoters and yellow dots represent putative SpoIIID binding sites. The lines represent the control exerted by SpoIIID over the indicated genes. B: model of the organization of the mother cell transcriptional network. σE drives production of SpoIIID, which then activates transcription of both CD1234 and sigK P2. CD1234 and probably also sigK P2 (the later indicated by a question mark in A and B) are under the control of a coherent FFL with an AND gate logic (2 and 3 in the figure) established by σE and SpoIIID thought to delay skinCd excision (which also requires the CD1231 recombinase) and the main period of sigK transcription to post-engulfment sporangia. Then, a positive auto-regulatory loop combined with a positive control by SpoIIID leads to an increase in sigK transcription at P2 (4 in the figure) and to σK activity. SpoIIID may also repress transcription from the σE-dependent sigK P1; the two regulatory proteins could thus form an incoherent FFL with an AND gate logic (1 in the figure), which could result in a low level of sigK transcription during engulfment. Transcription from sigK P1 would be shut-off coincidently with activation of P2. Possibly this would lead to a pulse in the production of σK in some cells in which skinCd is excised during engulfment (indicated as a dotted box in figure). As shown by correlating transcription of σK-dependent genes with stages of morphogenesis using single cell analysis, the onset of the main period of σK activity coincides with the transition from phase grey to phase bright spores, presumably when synthesis of the spore cortex is finalized and the final stages in the assembly of the spore coat and exosporium begins.

Recent studies have examined in detail the sporulation program of C. difficile and provided evidence that the temporal compartmentalization of sigma factor activity is less tightly regulated in C. difficile as compared to B. subtilis [16–18]. A difference between the sporulation programs in the two organisms may be the existence of a higher degree of redundancy in the control of gene expression at key stages in morphogenesis in B. subtilis. The control over spoIVCA and sigK transcription, skinBs excision, and proteolytical removal of the inhibitory pro-sequence ensures that σK is only active following engulfment completion in B. subtilis [41–43]. Since σK in C. difficile lacks a pro-sequence, the main period of σK activity may be mainly dictated by the time of CD1234 production and skinCd excision (Fig 9). In B. subtilis, both the sigK and spoIVCA genes are controlled by a coherent FFL involving σE and SpoIIID [19]. Thus, both the SpoIVCA-mediated skinBs excision and the transcription of sigK are delayed towards the end of the engulfment sequence, when the forespore signal that leads to pro-σK processing results in “just-in-time” activation of σK. In C. difficile, transcription of CD1234 and sigK decreased in a spoIIID mutant. We detected a common binding motif in the promoter region of these genes suggesting a direct effect of SpoIIID on their transcription. This motif is also present upstream of spoIIID itself allowing us to propose an auto-regulation for SpoIIID and to define a first consensus for the SpoIIID binding site of C. difficile (KRTAACARK) (S3A and S3B Fig) sharing partial similarity with the SpoIIID consensus of B. subtilis (S3C Fig) [19].

Our results show that expression of CD1234 in C. difficile relies on a coherent FFL involving σE and SpoIIID (Fig 9B) [19]. Although transcription of CD1234 is detected in the mother cell soon after asymmetric division and does not increase during or following engulfment completion, it is possible that the CD1234 protein only reaches a threshold level following engulfment completion. The effect of a spoIIID deletion on the transcription of sigK as assessed here using SNAPCd labeling and scoring of cells in which engulfment had been completed is less pronounced than previously reported on the basis of a more sensitive qRT-PCR analysis [18]. It seems possible that binding of SpoIIID to the sigK regulatory region represses the σE-dependent P1 promoter towards the end of the engulfment process, while allowing activation of transcription from P2 (Fig 3A). If so, deletion of spoIIID would allow prolonged utilization of P1 by σE, possibly explaining the reduced effect of the mutation following engulfment completion as seen here (Fig 3B). We do not presently know whether P2 is initially utilized by σE with the help of SpoIIID, and later by σK. Further work is needed to test these possibilities. In any event, positive auto-regulation of sigK transcription at P2 may then increase production of active σK locking the cells in a late-mode of gene expression [16–18] (Fig 9B). This genetic architecture may allow delaying sigK transcription and skinCd excision to ensure that the main period of σK activity follows engulfment completion [17]. Thus, although the pro-sequence is absent from σK, some level of redundancy also appears to be embedded in the activation of σK in C. difficile, with delayed transcription and rearrangement contributing to its timely activation. As we show here, the rearrangement is important, since expression of a skinCd-less sigK gene increases σK activity during engulfment. In this regard, we comment on the possible function of sigK P1. If indeed this promoter is repressed through binding of SpoIIID to the downstream box, P1 would be subject to a type I incoherent FFL, which could result in a pulse of sigK transcription (Fig 9B) [44]. Provided skinCd excision also occurs, a pulse in sigK transcription may result in σK activation during engulfment in some cells in a population (Fig 9B). Given that a skinCd-less sigK allele leads to alteration in the spore surface structure, we speculate that this regulatory scheme could produce spores with different structure and functional properties in a fraction of the population.

The presence of a skin element remains an exception in clostridia. Although the still more familiar designation of C. difficile was used herein, the organism differs significantly from typical Clostridial species, and was recently placed in the Peptostreptococcaceae family and renamed Peptoclostridium difficile [45]. Nevertheless, a prophage integrated into sigK is found in Clostridium tetani [46], in some strains of C. botulinum and in a strain of C. perfringens [47]. Absence of a skin element may be related to the involvement of σK in functions in addition to its role as a late mother cell-specific transcription factor. For instance, in C. acetobutylicum and C. botulinum, σK is required for entry into sporulation and for solventogenesis in the former organism and for cold and salt stress in the latter, while in C. perfringens σK is also involved in enterotoxin production [48]. It thus seems likely that skinCd together with the compartmentalized expression of CD1234 helps preventing ectopic and heterochronic activity of σK. This suggestion is in agreement with the observation that bypassing both the recombination and pro-protein processing levels of control leads to some activity of σK during stationary phase under conditions that do not support efficient sporulation by B. subtilis [42]. This inappropriate activity of σK is most likely the result of auto-regulation, and shows that even in B. subtilis, transcriptional control alone is not sufficient to restrict the activity of σK to the mother cell during late stages of spore development but also for proper sporulation as a pro-less skin-less strain of B. subtilis shows reduced sporulation [41, 42]. In contrast, the early activity of σK in the ΔskinCd strain of C. difficile, while causing alterations in coat assembly, does not affect the final titer of heat resistant spores. It is possible that the sporulation program in C. difficile is more permissive to changes in the proper timing of morphogenetic events [16–18]. It is also possible, however, that an additional as yet unidentified mechanism, controls the activity of σK in C. difficile.

Why the expression of CD1231 is not restricted to the mother cell is intriguing and might suggest the possible existence of other functions than skin excision for this recombinase. CD1231 may also function occasionally in the forespore or in vegetative cells, in the absence of CD1234, resulting in permanent elimination of skinCd, as it is known that some strains of C. difficile including epidemic strains lack this element [27, 28, 49]. This possibility also raises the question of whether in those strains σK is recruited to additional functions, by analogy with C. perfringens, C. botulinum and C. acetobutylicum. Importantly, as we show that the premature activity of σK during sporulation in C. difficile imposes alterations to the assembly of the spore surface layers, we speculate that spores of the skinCd-less epidemic strains may have alterations in structural and/or functional properties important for spore persistence and infection.

Reminiscent of the situation with skin, whose deletion alters assembly and function of the spore surface layers, it is noteworthy that the B. subtilis SPβ prophage is inserted into the spsM gene, required for the glycosylation of proteins at the spore surface, and that SPβ excision during sporulation depends on the mother cell-specific expression of the SPβ gene coding for the SprB RDF. Remarkably, SPβexcision during sporulation does not result in the assembly of phage particles, most likely because the prophage genes lack mother cell-specific promoters [32]. In different spore-formers, several other sporulation genes such as spoVFB encoding the dipicolinate synthase and spoVR involved in cortex formation are interrupted by phage-like elements that are able to excise during sporulation [32, 50]. Moreover, developmentally-controlled, recombinase-dependent excision of phage-like intervening elements also takes place in cyanobacteria where these elements, interrupting genes required for nitrogen fixation, are excised during heterocyst differentiation [51]. Insertion of phages or phage like elements in genes that are specifically expressed in terminal cell lines ensures their vertical transmission and minimizes cost for the host. However, regulated prophage excision may also occur in non-terminally differentiated cells. The Listeria monocytogenes comK gene, coding for the competence master regulatory protein, is interrupted by a prophage [52]. The DNA-uptake complex formed by the Com proteins is required for L. monocytogenes to escape from macrophage phagosomes and remarkably, excision of the comK intervening sequence is specifically induced during intracellular growth within phagosomes [52]. Also remarkably, prophage excision from comK as observed for SPβ excision in B. subtilis sporangia does not result in the production of phage particles [52]. Clearly, whether or not in terminally differentiated cells, host “domestication” of prophage excision, may lead to additional levels of genetic control over important cellular functions [22, 53].

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains, growth and sporulation conditions

C. difficile strains and plasmids used in this study are presented in Table 3. C. difficile strains were grown anaerobically (5% H2, 5% CO2, and 90% N2) in Brain Heart Infusion (BHI, Difco), which was used for selection of conjugants, in TY (Bacto tryptone 30 g.L-1, yeast extract 20 g.L-1, pH 7.4) or in sporulation medium (SM) [54], which was used for sporulation assays. SM medium contained per liter: 90 g Bacto tryptone, 5 g Bacto peptone, 1 g (NH4)2SO4, 1.5 g Tris Base. When necessary, cefoxitin (Cfx; 25 μg/ml), thiamphenicol (Tm; 15 μg.ml-1) or erythromycin (Erm; 2.5 μg.ml-1) was added to C. difficile cultures. E. coli strains were grown in LB broth. When indicated, ampicillin (100 μg.ml-1) or chloramphenicol (15 μg.ml-1) was added to the culture medium. The antibiotic analog anhydrotetracycline (ATc; 100 ng.ml-1) was used for induction of the Ptet promoter present in derivatives of the C. difficile pDIA6103 vector [34].

Table 3. Bacterial strains used in this study.

| Strain | Relevant Genotype/phenotype | Origin/Reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| Top10 | F- mcrA Δ (mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) f80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 deoR, recA1 araD139 Δ (ara-leu)7697 galK rpsL(StrR) endA1 nupG | Invitrogen |

| HB101 (RP4) | supE44 aa14 galK2 lacY1 Δ(gpt-proA) 62 rpsL20 (StrR)xyl-5 mtl-1 recA13 Δ(mcrC-mrr) hsdSB(rB-mB) RP4 (Tra+ IncP ApR KmR TcR) | Laboratory stock |

| BL21(DE3) | F−ompT gal dcm lon hsdSB(rB- mB-) λ(DE3 [lacI lacUV5-T7 gene 1 ind1 sam7 nin5]) | Novagen |

| C. difficile | ||

| 630Δerm | wild-type | Laboratory stock |

| AHCD532 | 630Δerm sigE::ermB | [17] |

| AHCD535 | 630Δerm sigK::ermB | [17] |

| AHCD601 | 630Δerm pFT47- PsigK -SNAPCd | [17] |

| AHCD667 | 630Δerm pFT47-PCD1231-SNAPCd | This work |

| AHCD690 | 630Δerm spoIIID::ermB pFT47- PsigK -SNAPCd | This work |

| AHCD695 | 630Δerm pFT47- PcotE- SNAPCd | [17] |

| AHCD699 | 630Δerm sigK::ermB pFT47- PcotE- SNAPCd | [17] |

| AHCD700 | 630Δerm spoIIID::ermB pFT47- PcotE- SNAPCd | This work |

| AHCD758 | 630Δerm CD1234::ermB pFT47- PcotE- SNAPCd | This work |

| AHCD763 | 630Δerm CD1231::ermB pFT47- PcotE- SNAPCd | This work |

| AHCD787 | 630Δerm pFT74 (SigK-SNAP, skin+) | This work |

| AHCD800 | 630Δerm spoIIID::ermB pFT74 (SigK-SNAP, skin+) | This work |

| AHCD851 | 630Δerm ΔskinCd pFT47- PcotE-SNAPCd | This work |

| CDIP224 | 630Δerm spoIIID::ermB | [18] |

| CDIP345 | 630Δerm sigE::ermB pFT47-PCD1234-SNAPCd | This work |

| CDIP389 | 630Δerm pFT47-PCD1234-SNAPCd | This work |

| CDIP396 | 630Δerm CD1234::ermB | This work |

| CDIP397 | 630Δerm CD1234::ermB pMTL84121-CD1234 | This work |

| CDIP399 | 630Δerm spoIIID::ermB pFT47-PCD1234-SNAPCd | This work |

| CDIP526 | 630Δerm CD1231::ermB | This work |

| CDIP533 | 630Δerm CD1231::ermB pMTL84121-CD1231 | This work |

| CDIP560 | 630Δerm pDIA6103 | This work |

| CDIP561 | 630Δerm pDIA6103-CD1234 | This work |

| CDIP562 | 630Δerm spoIIID::ermB pDIA6103 | This work |

| CDIP563 | 630Δerm spoIIID::ermB pDIA6103-CD1234 | This work |

| CDIP564 | 630Δerm sigE::ermB pDIA6103 | This work |

| CDIP565 | 630Δerm sigE::ermB pDIA6103-CD1234 | This work |

| CDIP566 | 630Δerm CD1231::ermB pDIA6103 | This work |

| CDIP567 | 630Δerm CD1231::ermB pDIA6103-CD1234 | This work |

| CDIP568 | 630Δerm CD1234::ermB pDIA6103 | This work |

| CDIP569 | 630Δerm CD1234::ermB pDIA6103-CD1234 | This work |

| CDIP583 | 630Δerm ΔskinCd | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pMTL007 | ClosTron plasmid; catP; intron containing ermB::RAM (CmR/TmR)1 | [55] |

| pMTL84121 | Clostridia modular plasmid; catP (CmR/TmR) | [56] |

| pDIA6103 | pRPF185 ΔgusA | [34] |

| pFT38 | pMTL84121-sigKskin+ (CmR/TmR) | [17] |

| pFT47 | pMTL84121-SNAPCd (CmR/TmR) | [17] |

| pFT51 | pFT47 PsigK-SNAPCd | [17] |

| pFT69 | pFT47 PcotE-SNAPCd | [17] |