Abstract

Limited work has examined worry, or apprehensive anticipation about future negative events, in terms of smoking. One potential explanatory factor is the tendency to respond inflexibly and with avoidance in the presence of smoking-related distress (smoking-specific experiential avoidance). Participants (n = 465) were treatment-seeking daily smokers. Cross-sectional (pre-treatment) self-report data were utilized to assess trait worry, smoking-specific experiential avoidance, and four smoking criterion variables: nicotine dependence, motivational aspects of quitting, perceived barriers to smoking cessation, and severity of problematic symptoms reported in past quit attempts. Trait worry was significantly associated with greater levels of nicotine dependence, motivation to quit smoking, perceived barriers for smoking cessation, more severe problems while quitting in the past; associations occurred indirectly through higher levels of smoking-specific experiential avoidance. Findings provide initial support for the potential role of smoking-specific experiential avoidance in explaining variable in the association between trait worry and a variety of smoking processes.

Keywords: worry, tobacco, AIS, psychological inflexibility, experiential avoidance

Introduction

Trait worry reflects relatively stable individual differences in the apprehensive expectation about future negative events.1–3 Worry is associated with cognitive avoidance and difficulties with emotion; at elevated levels, the hallmark characteristic of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD;4–6). Notably, there is increasing recognition that trait worry, especially at clinical levels, is associated with greater risk of substance use disorders.7–8

The Nature of Worry and Smoking

There is presently relatively little understanding of trait worry and smoking, although separate lines of indirect research have focused on the role of health-related worry or GAD and smoking.9 For example, smokers may tend to engage in health-related worry (e.g., concerns about a lack of self-control over smoking, or concerns about the health consequences of tobacco use10–11); such worry has often been associated with an increased level of current motivation to quit and a greater number of lifetime quit attempts,11–13 although these findings have not always been entirely consistent.14 Among clinical samples, individuals diagnosed with GAD, relative to those without, are significantly more likely to smoke,15–18 and smokers with GAD may be more nicotine dependent17 and less successful in quitting smoking, relative to smokers without GAD.18–19 Importantly, examining ‘trait worry’ rather than GAD or worry specific to health may be advantageous as such an approach offers a broader dimensional framework to explicate the nature of broad-based worry from clinical and non-clinical perspectives. In one study examining trait worry among treatment-seeking smokers, higher levels of general worry were associated with cognitive-affect smoking variables, including holding stronger beliefs that smoking will reduce negative affect (outcome expectancies), smoking to reduce negative affect (motives), and perceiving more barriers to successful smoking cessation.20 These associations were evident after accounting for gender, smoking rate, Axis I psychopathology, tobacco-related medical problems, and negative affectivity.

Mechanisms Related to Worry and Smoking

Although past work has shown health-related worry, GAD, and to a lesser extent, trait worry may be important to certain smoking processes (e.g., nicotine dependence,17 motivation to quit smoking and number of lifetime quit attempts,11–13 expectancies and motives for use,20 perceived barriers to quitting,20 and abstinence outcomes18–19), the mechanisms explicating the worry-smoking relations remain largely unexplored. Given cognitive avoidance and difficulties tolerating negative emotion are considered phenotypic markers of trait worry, smokers who are worry-prone may be particularly likely to respond to smoking-related personal/internal experiences in a similar way; that is, with avoidance in the form of reliance on smoking. Thus, theoretically, it is possible that given the global nature of worry (across different domains), this avoidant-driven response style among smokers may increase vulnerability for similar avoidance responding in the context of smoking-specific distress. Indeed, there is a growing recognition that how one responds to aversive distressing states may be an important individual difference factor implicated in the maintenance of smoking and difficulties quitting.21,22 For example, smokers with a greater ability to tolerate or withstand aversive somatic distress, relative to those with a lower threshold, are less likely to lapse during a cessation attempt.22 Also, smokers with a lower tolerance of distress on laboratory tasks have shorter durations of smoking abstinence.22–24 Further, one’s tendency to avoid uncomfortable internal experiences has been implicated in the maintenance of various forms of anxiety and substance use disorders.24,26 Thus, it is plausible that experiential avoidance may play a role in the maintenance of both trait worry and cognitive and behavioral aspects of cigarette smoking, which is consistent with theoretical models that suggest that one’s tendency to respond with avoidance is likely domain general.27

The broad-based smoking literature suggests that in response to smoking-specific distress, smokers may be particularly prone to seek out opportunities to escape, avoid, or reduce distressing thoughts, feelings, and bodily discomfort and frequently may do so by smoking.28–30 This tendency is conceptualized as a smoking-specific form of experiential avoidance.28 Research suggests that an inflexible, avoidant response to smoking-related aversive thoughts, feelings, or interoceptive states (e.g., withdrawal symptoms) is of clinical importance in better understanding certain cognitive-affective vulnerabilities and processes governing the maintenance and relapse of smoking (e.g., severity of problems while quitting).31

Current Aims and Definition of Smoking-Relevant Processes

The current study aimed to examining smoking-specific experiential avoidance as an explanatory mechanism linking trait worry and an array of smoking processes. In particular, four theoretically and clinically-relevant smoking variables, that have been linked to worry,11–13,17,20 and smoking-specific experiential avoidance,32–35 were examined. First, trait worry was expected to be associated with higher levels of nicotine dependence (greater physiological reliance on cigarettes),17 and indirectly associated through smoking-specific experiential avoidance. Second, trait worry was hypothesized to be associated with greater motivation to quit smoking,11–13 and indirectly associated due to smoking-specific experiential avoidance.33 Third, trait worry was hypothesized to be associated with greater perceptions/beliefs that quitting smoking will be challenging (i.e., expecting many difficulties/obstacles),20 which would be indirectly explained by smoking-specific experiential avoidance.32 Fourth, trait worry was expected to be associated with more severe withdrawal-related problems during prior quit attempts, based on the finding that worry and experiential avoidance are associated with cessation difficulties.18–19,35 Collectively, these smoking variables represent a continuum of smoking processes that reflect maintenance of use, quit history, and cognitions and motivation regarding quitting,36 and appear to be especially relevant to emotionally-vulnerable smokers.31–35 It is possible that smoking-specific experiential avoidance may serve to maintain smoking and quit difficulties among worry-prone smokers, however, these associations have not yet been empirically tested. Based on documented relevance of several other third variables related to anxiety vulnerabilities, experiential avoidance, and cigarette smoking, the associations were expected to be evidenced after accounting for gender,20,27,37 tobacco-related medical problems,10,11 alcohol or cannabis use,38 or the trait-like propensity to experience negative mood.20,34–35

Methods

Participants

Participants (n = 465) were adult treatment-seeking daily smokers (Mage = 36.6, SD = 13.58; 48.4% female). Participants primarily identified as White (85.8%) while fewer identified as African-American (8.3%), Hispanic (2.4%), Asian (1.1%), and other (2.4%). Participants were well educated with 74.0% indicating that they completed at least part of college. In terms of relationship status, 44.1% reported marital status as never married, 33.1% as married/cohabitating, 20.9% as divorced/separated, and 1.9% as widowed. The average daily smoking rate of this sample was 16.7 (SD = 9.91), and on average, participants reported starting smoking at age 14.9 (SD = 3.44). Slightly more than one-quarter of the participants (29.6%) reported a tobacco-related illness (heart problems, hypertension, respiratory disease, and/or asthma). On average, participants reported 3.4 (SD = 2.48) previous quit attempts; 6.9% (n = 32) reported never having made a previous attempt to quit smoking. Of the sample, 44.4% met criteria for at least one current (past year) psychological disorder, and the most common primary psychiatric diagnoses included social anxiety disorder (10.3%), generalized anxiety disorder (4.9%), and alcohol use disorder (4.6%).

Measures

Structured Clinical Interview-Non-Patient Version for DSM-IV (SCID-I/NP39)

Diagnostic assessments of past year Axis I psychopathology were conducted using the SCID-I/NP, which were administered by trained research assistants or doctoral level staff and supervised by independent doctoral-level professionals. Interviews were audio-taped and the reliability of a random selection of 12.5% of interviews was checked for diagnostic accuracy; no disagreements were noted.

Smoking History Questionnaire (SHQ40)

The SHQ is a self-report questionnaire used to assess smoking history (e.g., onset of regular daily smoking), pattern (e.g., number of cigarettes consumed per day), and problematic symptoms experienced during past quit attempts (e.g., weight gain, nausea, irritability, and anxiety). In the present study, the SHQ was employed to describe the sample on smoking history and patterns of use (e.g., smoking rate), and then to create a criterion variable – the mean composite score of severity of problem symptoms experienced during past quit attempts (for those who reported ≥ 1 lifetime quit attempt).

Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND41)

The FTND is a 6-item scale that assesses gradations in tobacco dependence. Scores range from 0–10, with higher scores reflecting high levels of physiological dependence on nicotine. The FTND has adequate internal consistency, positive associations with key smoking variables (e.g., saliva cotinine), and high test-retest reliability.41,42 The FTND total score was used as a covariate in the present study and internal consistency was found to be acceptable (Cronbach’s α = .64).

Medical History Form

A medical history checklist was used to assess current and lifetime medical problems. A composite variable was computed for the present study as an index of tobacco-related medical problems, which was entered as a covariate in all models. Items in which participants indicated having ever been diagnosed (heart problems, hypertension respiratory disease and asthma; all coded 0 = no, 1 = yes) were summed and a total score was created (observed range from 0 – 3), with greater scores reflecting the occurrence of multiple markers of tobacco-related disease.

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT43)

The AUDIT is a 10-item self-report measure developed to identify individuals with alcohol problems. Total scores range from 0 to 30, with higher scores reflecting more hazardous drinking. The psychometric properties of the AUDIT are well documented. In the present study, the AUDIT total score was used as a covariate in all analyses; internal consistency was good (Cronbach’s α = .839).

Marijuana Smoking History Questionnaire (MSHQ44)

The MSHQ is a 40-item measure that assesses cannabis use history and patterns of use. One item was used in the current study to determine status of marijuana use in the past 30 days: “Please rate your marijuana use in the past 30 days” (Responses range from 0 = No use, 4 = Once a week, to 8 = More than once a day). This item was dichotomously coded to reflect a marijuana use status variable (0 = No use; 1 = Past 30-day use), which was entered as a covariate in all analyses.

Positive and Negative Affect Scales (PANAS45)

The PANAS is a self-report measure that requires participants to rate the extent to which they experience each of 20 different feelings and emotions (e.g., nervous, interested) based on a Likert scale that ranges from 1 (Very slightly or not at all) to 5 (Extremely). The measure yields two factors, negative and positive affect, and has strong documented psychometric properties.44 The negative affectivity subscale was used as a covariate in the present study; internal consistency was excellent (Cronbach’s α = .90).

The Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ46)

The PSWQ is a 16-item measure of trait worry. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (5 reverse-scored) and assess the excessiveness and uncontrollability of worry (e.g., “Once I start worrying, I cannot stop”). This scale has demonstrated good psychometric properties, including internal consistency, test–retest reliability, and discriminate validity.46–49 The PSWQ demonstrated high internal consistency in the current sample (Cronbach's α = .81).

Acceptance and Inflexibility Scale (AIS28)

The AIS is a 13-item self-reported measured that assess the link between internal (affective) triggers and smoking (smoking-related inflexibility/avoidance). Instructions ask the respondents to consider how they respond to difficult thoughts that encourage smoking (e.g., “I need a cigarette”), different feelings that encourage smoking (e.g., stress, fatigue, boredom), and bodily sensations that encourage smoking (e.g., “physical cravings or withdrawal symptoms”). Example items include “How likely is it you will smoke in response to [thoughts/feelings/sensations]?”, “How important is getting rid of [thoughts/feelings/sensations]?”, and “To what degree must you reduce how often you have these [thoughts/feelings/sensations] in order not to smoke?”. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Not at all to 5 = Very much), with higher scores reflecting more inflexibility/avoidance in the presence of difficult smoking-related thoughts, feelings, and sensations. The AIS has displayed good reliability and validity in past work.28,29,32 The AIS total score—an index of smoking inflexibility/avoidance—was used as the indirect explanatory variable. Internal consistency was excellent in the present sample (Cronbach’s α = .93).

Motivational Aspects of Smoking Cessation Questionnaire (MASC50)

The MASC is a well-established ten-item questionnaire that was employed to index various aspects of participants’ motivation to quit smoking. Participants rate ten different aspects of motivation to quit on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = No, not at all motivated to 4 = Yes, very motivated). Example items are “I wish to quit smoking” and “I want more information about quitting smoking.” The MASC has demonstrated good internal consistency.49 Research using the MASC also supports its validity, finding levels of motivation to quit are associated with perception of smoking consequences49 and number of serious quit attempts.51 The internal consistency of the MASC in the current sample was good (Cronbach’s α = .86).

Barriers to Cessation Scale (BCS52)

The BCS is a self-report assessment of perceived barriers associated with quitting smoking. Specifically, the BCS is a 19-item measure on which respondents indicate, on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = Not a barrier or not applicable to 3 = Large barrier), the degree to which they identify with each listed barriers (e.g., “Weight gain,” “Friends encouraging you to smoke,” “Fear of failing to quit”). Scores are summed to derive a total score. The BCS has strong psychometric properties, including continent and predictive validity, internal consistency, and reliability.52 The BCS total score was used as a criterion variable in the present study; internal consistency was good in the present sample (Cronbach’s α = .89).

Procedure

Adult daily smokers were recruited from the community (via flyers, newspaper ads, radio announcements) to participate in a large randomized controlled trial examining the efficacy of two smoking cessation interventions. A description of study procedures are presented elsewhere.35 Participants provided written informed consent prior to participation and the study protocol was approved by the respective Institutional Review Boards. Individuals responding to study advertisements were scheduled for an in-person, baseline assessment. After providing written informed consent, participants were interviewed using the SCID-I/NP and completed a computerized battery of self-report questionnaires. The current study is based on secondary analyses of baseline (pre-treatment) data for a sub-set of the sample; these analyses have not been reported before. Of the 724 participants assessed for the study, 574 provided baseline data. Cases were selected if all data were available for the examined covariates, predictor, indirect predictor, and criterion variables: 109 cases were removed due to incomplete data, thus 465 cases were retained for analyses. There were no differences between excluded and retained cases based on gender, age, level of education, number of current Axis I diagnoses, or level of smoking (per expired carbon monoxide breath level).

Data Analytic Strategy

Analyses were conducted in PASW Statistics 21.0 (IBM SPSS Inc.). First, zero-order correlations among the predictor (PSWQ-Total), explanatory (AIS), and all criterion variables were examined. Criterion measures were selected in order to capture a range of theoretically and clinically-relevant tobacco-related behavioral and cognitive domains related to smoking and smoking cessation: nicotine dependence (FTND), motivation to quit smoking (MASC), perceived barriers to smoking cessation (BCS-Total), and severity of problematic symptoms during past quit attempts. Next, a series of regression-based models were conducted to examine smoking-specific experiential avoidance (per AIS) as an explanatory variable in the associations between trait worry (PSWQ) and the criterion outcomes (i.e., a total of 4 models were conducted). Gender, alcohol use (AUDIT), cannabis use status (per MSHQ), negative affectivity (PANAS-NA), and tobacco-related medical problems were included as covariates in the models of M and Y. Analyses were conducted using PROCESS, a conditional modeling program that utilizes an ordinary least squares-based path analytical framework to test for both direct and indirect associations.53 All relative indirect associations were subjected to follow-up bootstrap analyses with 10,000 samples and a 95-percentile confidence interval (CI) was estimated (as recommended;54–56).

Results

Zero-order Correlations

Trait worry was significantly and positively associated with female gender, alcohol use, negative affectivity, nicotine dependence, barriers to smoking cessation, and severity of problems experienced while quitting. Smoking-specific experiential avoidance also was significantly (and positively) related to female gender, negative affectivity, and all criterion variables. Additionally, being female was related to higher self-reported levels of negative affect, perceived barriers to smoking cessation, and severity of prior problematic symptoms while quitting. See Table 1 for the descriptive data and summary of the zero-order correlations.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlations for study variables (n = 465).

| Variable | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | Mean or N (SD or %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender (% Female)a | −.106* | −.059 | .136** | .002 | .261** | .184** | −.015 | .056 | .224** | .284** | 225 (48.4) |

| 2. AUDIT totala | .195** | .245** | −.117* | .121** | .037 | −.110* | −.117* | .091 | .046 | 6.2 (6.02) | |

| 3. Cannabis Use (% Y)a | .074 | .039 | −.008 | −.066 | −.061 | −.128** | −.002 | −.109* | 260 (55.9) | ||

| 4. PANAS-NA a | .010 | .720** | .244** | .054 | −.055 | .370** | .369** | 19.1 (7.06) | |||

| 5. Medical Problems (%Y)a | −.023 | .058 | −.021 | .004 | .006 | .016 | 138 (29.7) | ||||

| 6. PSWQb | .307** | .111* | −.023 | .402** | .384** | 43.6 (14.26) | |||||

| 7. AISc | .255** | .197** | .582** | .409** | 45.0 (10.74) | ||||||

| 8. FTNDd | .219** | .196** | .179** | 5.2 (2.28) | |||||||

| 9. MASCd | .079 | .092* | 31.0 (7.12) | ||||||||

| 10. BCSd | .511** | 24.9 (11.05) | |||||||||

| 11. Quit Problemsd | 2.0 (0.67) |

Note:

p < .05;

p < .01;

Covariates;

Predictor Variable;

Explanatory Variable;

Criterion Variables

Gender = % listed are females (coded 0=male, 1=female); AUDIT Total = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; Cannabis Use = Past 30 days cannabis use status per the Marijuana Smoking History Questionnaire, percent endorsed yes is listed; Medical Problems = Tobacco-related medical problems as indicated by the a medical history form, percent endorsed yes is listed; PANAS-NA = Positive and Negative Affect Scales – Negative Affect subscale; PSWQ = Penn State Worry Questionnaire; AIS = Acceptance and Inflexibility Scale – Total score; FTND = Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence – total score; MASC = Motivational Aspects of Smoking Cessation; BCS = Barriers to Cessation Scale – Total score; Quit Problems = Average severity of problems experienced while quitting per the Smoking History Questionnaire. Columns numbers 1 – 12 correspond to the variables numbers in the far left column.

Analyses of Direct and Indirect Associations

Regression results for paths a, b, c, and c’ are presented in Table 2, which correspond to each of the four models (see Footnote 1). The estimates of the indirect paths tested, which also are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Regression results for the tested models.

| Y | Model | b | SE | t | p | CI (lower) | CI (upper) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PSWQ →S-AIS (a) | .175 | .049 | 3.550 | .0004 | .078 | .272 |

| S-AIS → FTND (b) | .055 | .010 | 5.451 | < .0001 | .035 | .075 | |

| PSWQ → FTND (c’) | .015 | .011 | 1.357 | .176 | −.007 | .0336 | |

| PSWQ → FTND (c) | .024 | .011 | 2.211 | .028 | .003 | .046 | |

| PSWQ → S-AIS → FTND (a*b) | .010 | .003 | .004 | .017 | |||

| 2 | S-AIS → MASC (b) | .145 | .032 | 4.562 | < .0001 | .083 | .208 |

| PSWQ → MASC (c’) | −.028 | .034 | −.812 | .417 | −.094 | .039 | |

| PSWQ → MASC(c) | −.002 | .034 | −.065 | .948 | −.070 | .065 | |

| PSWQ → S-AIS → MASC (a*b) | .025 | .009 | .011 | .048 | |||

| 3 | S-AIS → BCS (b) | .510 | .039 | 12.986 | < .0001 | .433 | .588 |

| PSWQ → BCS (c’) | .094 | .042 | 2.239 | .026 | .012 | .177 | |

| PSWQ → BCS (c) | .183 | .048 | 3.785 | .0002 | .088 | .278 | |

| PSWQ → S-AIS → BCS (a*b) | .089 | .025 | .042 | .139 | |||

| 4 | S-AIS → PROB (b) | .018 | .003 | 6.911 | < .0001 | .013 | .023 |

| PSWQ → PROB (c’) | .005 | .003 | 1.650 | .099 | −.001 | .010 | |

| PSWQ → PROB (c) | .001 | .003 | 2.685 | .008 | .002 | .014 | |

| PSWQ → S-AIS → PROB (a*b) | .003 | .001 | .002 | .005 | |||

Note. Path a is equal across all models; therefore, it presented only in the model with Y1 to avoid redundancies. N for analyses of models Y1–Y3 included 466 cases. Analyses for Y4 include 432 cases (those reporting ≥ 1 lifetime quit attempts). The standard error and 95% CI for a*b are obtained by bootstrap with 10,000 re-samples. PSWQ (trait worry) is the predictor variable (X), S-AIS (Smoking-related affective Inflexibility) is the explanatory variable (M), and FTND (nicotine dependence; Y1), MASC (motivational aspects of quitting; Y2), BCS (barriers to smoking cessation; Y3), and PROB (severity of quit problems; Y4) are the criterion variables. CI (lower) = lower bound of a 95% confidence interval; CI (upper) = upper bound; → = affects.

The total effect model with nicotine dependence (FTND) was significant (R2y1,x = .034, df = 6, 458, F = 2.704, p < .014; path c), as was the full model with the experiential avoidance (R2M,x = .093, df = 7,457, F = 6.708, p < .0001). The direct effect (path c’) of trait worry in terms of nicotine dependence after controlling for experiential avoidance was non-significant. Regarding the test of the indirect effect, higher levels of trait worry was associated with greater perceived barriers to smoking cessation indirectly through greater levels of smoking-specific experiential avoidance (effect a*b).

The total effects model for motivation to quit smoking (MASC; R2y2,x = .028, df = 6, 458, F = 2.179, p = .044) and the full model with experiential avoidance accounted for significant variance (R2M,x = .070, df = 7, 457, F = 4.922, p < .0001). The direct effect of trait worry on motivation to quit smoking after controlling for experiential avoidance was non-significant. Regarding the test of the indirect effect, higher levels of trait worry was associated with higher motivation to quit smoking, indirectly through higher levels of smoking-specific experiential avoidance.

For perceived barriers for quitting, the total effects model accounted for significant variance (R2y3,x = .194, df = 6, 458, F = 18.409, p < .0001). The direct effect of trait worry on barriers to smoking cessation remained significant after controlling for experiential avoidance. Next, the indirect effect was estimated and revealed that higher trait worry was associated with greater perceived barriers to smoking cessation, which occurred indirectly through greater levels of smoking-specific experiential avoidance.

In regard to severity of problems reported while quitting in the past, these analyses were conducted only on the sample of participants reporting ≥ 1 previous quit attempts (n = 432; 1 case had a missing value on this variable). Results indicated that the total effects model accounted for significant variance in severity of quit problems (R2y4,x = .246, df = 6, 425, F = 23.060, p < .0001). The full model with experiential avoidance accounted for significant variance in quit problem severity (R2M,x = .337, df = 7, 424, F = 30.845, p < .0001). The direct effect of trait worry on prior problematic symptoms while quitting, controlling for experiential avoidance, was non-significant. The indirect effect was estimated and indicated trait worry was associated with greater self-report severity of problem symptoms while quitting smoking, which occurred indirectly through greater levels of smoking-specific experiential avoidance.

Specificity Analyses

While it was expected that generalized trait worry would increase vulnerability for domain-specific experiential avoidance (i.e., smoking), as a method of further strengthening the directionality and interpretation of the observed results, four alternative models were tested. Here, proposed predictor variable (trait worry) and potential explanatory variable (smoking-specific experiential avoidance) were reversed for each of the four models tested previously.54 Tests of the indirect associations in these reversed models were estimated based on 10,000 bootstrap re-samples. Results were non-significant for nicotine dependence (b = .002, CI95% = −.001, .007), motivational aspects of quitting (b = −.004, CI95% = −.017, .005), and problems while quitting (b = .001, CI95% = −.001, .002), but was significant for perceived barriers for quitting (b = .015, CI95% = .003, .032). Thus, higher levels of general trait worry may indirectly be related to the associations between smoking-specific experiential avoidance and perceived barriers to smoking cessation.

Discussion

Limited research has examined the associations between trait worry and smoking. Given the role of cognitive and experiential avoidance in the maintenance of both trait worry3 and cigarette smoking35, the present study aimed to uniquely contribute to this emerging area of research by examining the role of smoking-specific experiential avoidance as a link between trait worry and an array of clinically-relevant smoking processes. As hypothesized, among daily treatment-seeking smokers, trait worry was associated with higher levels of nicotine dependence, greater motivation to quit smoking, more perceived barriers to smoking cessation, and greater severity of problems during prior quit attempts. These associations were explained indirectly by smoking-specific experiential avoidance – i.e., the tendency to respond with inflexibility/avoidance in the presence of aversive smoking-related thoughts, feelings, or internal sensations. These observed indirect associations were incrementally associated with the criterion variables over and above and the variance accounted for by relevant covariates including gender, alcohol and cannabis use, negative affectivity, and tobacco-related medical problems. Moreover, there appears to be a unique directional indirect association for three of the four examined outcomes; an alternative, reversed model was non-significant. This pattern of findings is consistent with theoretical expectations that the general tendency to cognitively avoid in the context of distress (i.e., via worry) may predispose smokers to rely on avoidance tactics to manage other specific forms of distress (in this case, smoking-relevant distress), which in turn, may account for increased reliance on smoking, difficulty quitting, and increased desire to quit.

Interestingly, it appears that experiential avoidance is associated with cognitive aspects of smoking (one’s perception about barriers to smoking cessation), which was explained indirectly by trait worry, suggesting potentially reciprocal relations between both general and smoking-specific aspects of experiential avoidance in terms of forecasting cessation difficulties. While the cross-sectional nature of the current data limit comprehensive understanding of these associations, the findings suggest that there is likely an important interplay between worry, smoking-specific experiential avoidance, and various aspects of smoking. These findings invite future work to explore the patterning between such variables over time.

Overall, the present findings suggest that smokers with higher levels of trait worry may be more prone to avoidance or inflexible responding in emotional smoking-related context, which may promote a greater reliance on smoking (nicotine dependence), the perception that quitting may be more difficult, and actual difficulties while quitting, as indexed by severity of previous problems while quitting. While these associations were modest in absolute size, they were incremental relative to a wide range of other factors known to co-occur with smoking, medical disease, and psychopathology. Thus, the clinical impact of experiential avoidance specific to smoking should be judged in this larger 'incremental' context. Moreover, past work suggests smoking-specific experiential avoidance is a malleable construct and therefore can be directly targeted in treatment.28,29 The extent to which addressing experiential avoidance as it relates to smoking among worry-prone smokers has not yet been investigated, although appears to worthy of further examination given the current findings.

The observation that smoking-specific experiential avoidance indirectly accounted for significant variance in the associations between of higher levels of trait worry among smokers and greater motivation to quit smoking warrants brief comment as it may seem counter intuitive. First, there was a non-significant association between trait worry and motivational aspects of quitting smoking. However, there was a robust observed association between smoking-specific experiential avoidance and motivation to quit smoking, which indirectly accounted for significant variance in the association of general worry and motivation to quit. This set of findings suggests that from a bivariate level, worry and motivation to quit are unrelated. It is only due to high levels of specific experiential avoidance (to smoking) that there was an association between trait worry on greater motivation to quit. Such a finding suggests that in the context of a (anxiety) diathesis, such as trait worry, this may give rise to the tendency to avoid smoking-related distress (i.e., thinking about the negative consequences smoking) and lack of control/capacity to adaptively respond to such distress (i.e., these smokers instead respond inflexibly by attempting to control or decrease distress through avoidance). In turn, this process may contribute to motivation to quit given the difficulties experienced in managing smoking-related distress. Thus, in this case, struggling to manage smoking-related distress adaptively may facilitate motivation to quit among worry-prone smokers, although this enhanced motivation is unlikely to actually result in successful cessation in these persons.57

There are several limitations of the current study. First, the present study relied on cross-sectional methodological design, so it is unclear whether high levels of trait worry are causally related to increases in smoking-related experiential avoidance, or related to the examined smoking processes. As a result, based on the nature of the data used in the current study, the tests of the indirect tests were solely based on a theoretical framework, not temporal sequencing. Second, self-report measures were utilized as the primary assessment methodology in the current study. The utilization of self-report methods does not fully protect against reporting errors and may be influenced by shared method variance. Thus, future studies could build upon the present work by utilizing more comprehensive multi-method protocols. For example, experiential emotional elicitation procedures such as worry-based scripts/narratives could be used to examine worry-responding in the laboratory in terms of in vivo smoking cognitions and behavior. Fourth, the sample was largely comprised of a relatively homogenous group of treatment-seeking smokers, thereby limiting generalizability of these findings to more ethnically/racially diverse samples of smokers. Fifth, the internal consistency for the FTND was relatively low, a problem that frequently occurs with this measure.63 However, Cronbach alpha values are fairly sensitive to the number of items in each scale and it is not uncommon to find lower Cronbach values with shorter scales.64 Lastly, the current study examined four aspects of smoking trajectories. Future work is needed to explore the merit of the present model over the course of a quit attempt to better understand how it applies to a broader range of tobacco-relevant processes (e.g., withdrawal symptoms, prospective quit outcomes).

Conclusions

In summary, the present study adds to the emerging research on smoking-specific experiential avoidance.28,32,35 Findings suggest the potential importance of addressing trait worry and smoking-specific cognitive inflexibility as it relates to the maintenance of smoking. While smoking cessation treatment programs have been developed to target specific emotional disorders (e.g., certain anxiety or mood disorders58–61), such approaches may be less generalizable due to phenotypic-specificity of the intervention. Broader, emotional vulnerability-based, transdiagnostic treatment approaches to smoking cessation may have superior utility. For example, in the case of general worry, by integrating worry-reduction methods via psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring, imaginal exposure/worry scripts, and emotion regulation strategies into smoking cessation treatment, it may be possible to facilitate greater success in smoking cessation. Moreover, it appears that it may be important to address smoking-specific experiential avoidance (e.g., response to unhelpful smoking cognitions – “I am lost without cigarettes”) in order to enhance psychological flexibility related to smoking (and decrease avoidance) to facilitate more successful cessation. Indeed, acceptance and commitment-based smoking cessation treatments that include various techniques to enhance psychological flexibility (e.g., experiential awareness, openness, willingness, mindfulness, cognitive diffusion) have been shown to reliably reduce smoking-specific avoidance and enhance smoking cessation outcomes.28, 29,62 It is possible that these therapeutic strategies may be particularly helpful for worry-prone smokers in order to work toward accepting distressing smoking-related thoughts (e.g., I need a cigarette), feelings (e.g., stress, nerves), and bodily states (e.g., nicotine withdrawal) when preparing and subsequently making a cessation attempt. It is also possible that such strategies may facilitate broad-based cognitive flexibility that would tap aspects of trait worry, thus potentially being well-suited for worry-prone smokers (whether with GAD or not).

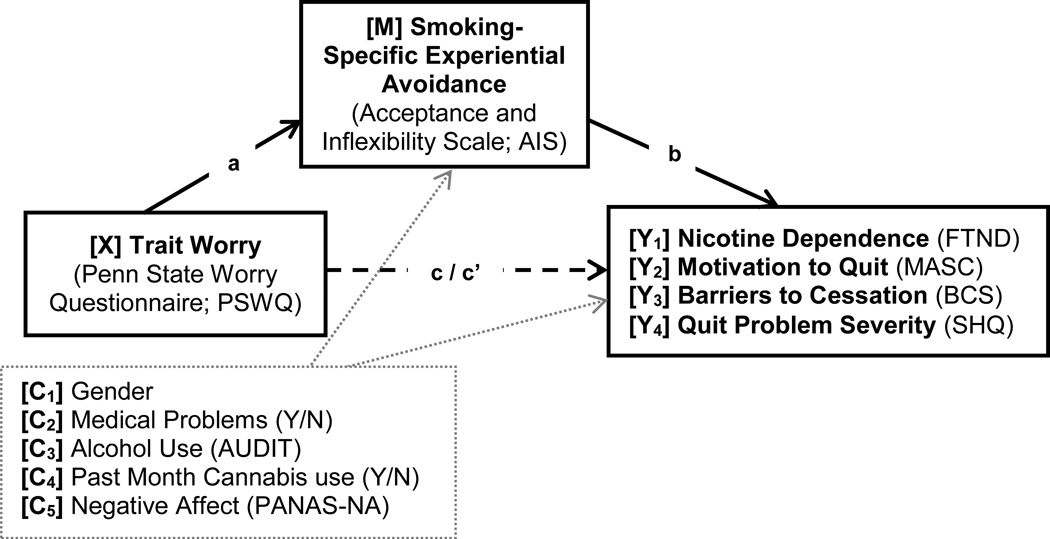

Figure 1.

Conceptual model to test of indirect associations

Notes: a = Effect of X on M; b = Effect of M on Yi; c’i = Direct effect of X on Yi controlling for M; a*b = Indirect effect of M; four separate models were conducted for each criterion variable (Y1–4). AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; PANAS-NA = Positive and Negative Affect Scales – Negative Affect subscale; PSWQ = Penn State Worry Questionnaire; FTND = Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence – total score; MASC = Motivational Aspects of Smoking Cessation; BCS = Barriers to Cessation Scale – Total score; Quit Problem Severity = Average severity of problems experienced while quitting per the Smoking History Questionnaire- SHQ.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support

This work was supported by a grant awarded to Drs. Michael J. Zvolensky and Norman B. Schmidt (R01-MH076629-01A1). Ms. Farris is supported by a cancer prevention fellowship through the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (R25T-CA057730), and a pre-doctoral National Research Service Award (F31-DA035564-01). Please note that the content presented does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, and that the funding sources had no other role other than financial support.

Footnotes

The same regression models were conducted without PANAS-NA as a covariate due to the high degree of correlation between PANAS-NA and the predictor variable (PSWQ). Additionally, models were run covarying for depressive/anxiety disorders per the SCID-I/NP (coded 1 = primary past year depressive/anxiety disorder or 0 = no past year depressive/anxiety disorder). Results from these alternative models yielded the same patterns of results – such that the relations between worry and smoking variables were explained by AIS.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th. Washington, DC: 2000. text revision. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borkovec TD. The nature, functions and origins of worry. In: Davey G, Tallis F, editors. Worrying: perspectives on theory assessment and treatment. Sussex, England: Wiley & Sons; 1994. pp. 5–33. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borkovec TD, Alcaine OM, Behar E. Avoidance theory of worry and generalized anxiety disorder. In: Heimberg R, Turk C, Mennin D, editors. Generalized anxiety disorder: Advances in research and practice. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2004. pp. 77–108. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrews G, Hobbs MJ, Borkovec TD, et al. Generalized worry disorder: A review of DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder and options for DSM-V. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:134–147. doi: 10.1002/da.20658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borkovec TD, Roemer L. Perceived functions of worry among generalized anxiety disorder subjects: Distraction from more emotionally distressing topics? J Behav Ther Exp Psy. 1995;26:25–30. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(94)00064-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mennin DS, Heimberg RG, Turk CL. Applying an emotional regulation framework to integrative approaches to generalized anxiety disorder. Clin Psychol-Sci Pr. 2002;9:85–90. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS, et al. Prevalence, correlates, co-morbidity, and comparative disability of DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder in the USA: Results from the national epidemiological survey on alcohol and related conditions. Psychol Med. 2005;35:1747–1759. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Analucia AA, Hasin DS, Nunes EV, et al. Comorbidity of generalized anxiety disorder and substance use disorders: Results from the national epidemiological survey on alcohol and related conditions. J Clin Psychiat. 2010;71(9):1187–1195. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05328gry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spada MM, Nikčević AV, Moneta GB. Metacognition as a mediator of the relationship between emotion and smoking dependence. Addict Behav. 2007;32:2120–2129. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Köblitz AR, Magnan RE, McCaul KD. Smokers’ thoughts and worries: A study using ecological momentary assessment. Health Psychol. 2009;28:484–492. doi: 10.1037/a0014779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCaul KD, Mullens AB, Romanek KM. The motivational effects of thinking and worrying about the effects of smoking cigarettes. Cognition Emotion. 2007;21:1780–1798. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dijkstra A, Brosschot J. Worry about health in smoking behaviour change. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41:1081–1092. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(02)00244-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magnan RE, Koblitz AR, Zielke DJ. The effects of warning smokers on perceived risk, worry, and motivation to quit. Ann Behav Med. 2009;37:46–57. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9085-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klein WMP, Zajac LE, Monin MM. Worry as a moderator of the association between risk perceptions and quitting intentions in young adult and adult smokers. Ann Behav Med. 2009;38:256–261. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cougle JR, Zvolensky MJ, Fitch KE, et al. The role of comorbidity in explaining the associations between anxiety disorders and smoking. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12:355–364. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cranford JA, Eisenberg D, Serras AM. Substance use behaviors, mental health problems, and use of mental health services in a probability sample of college students. Addict Behav. 2009;34:134–145. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodwin RD, Zvolensky MJ, Keyes KM. Mental disorders and cigarette use among adults in the United States. Am J Addiction. 2010;21:416–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2012.00263.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lasser K, Boyd J, Woolhandler S, et al. Smoking and mental illness. JAMA-J Am Med Assoc. 2000;284:2606–2610. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.20.2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piper ME, Cook JW, Schlam TR, et al. Anxiety diagnoses in smokers seeking cessation treatment: Relations with tobacco dependence, withdrawal, outcome and response to treatment. Addiction. 2010;106:418–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03173.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peasley-Miklus CE, McLeish AC, Schmidt NB. An examination of smoking outcome expectancies, smoking motives and trait worry in a sample of treatment-seeking smokers. Addict Behav. 2012;37:407–413. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leyro TM, Zvolensky MJ, Vujanovic AA. Anxiety sensitivity and smoking motives and outcomes expectancies among adult daily smokers: Replication and extension. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:985–994. doi: 10.1080/14622200802097555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown RA, Lejuez CW, Strong DR, et al. A prospective examination of distress tolerance and early smoking lapse in adult self-quitters. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11:493–502. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hajek P, Belcher M, Stapleton J. Breath-holding endurance as a predictor of success in smoking cessation. Addict Behav. 1987;12:285–288. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(87)90041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.West RJ, Hajek P, Belcher M. Severity of withdrawal symptoms as a predictor of outcome of an attempt to quit smoking. Psychol Med. 1989;19:981–985. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700005705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blackledge JT, Hayes SC. Emotion regulation in acceptance and commitment therapy. JCLP/In Session: Psychotherapy in Practice. 2001;57:243–255. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(200102)57:2<243::aid-jclp9>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayes SC, Wilson KG, Gifford EV, et al. Experiential avoidance and behavioral disorders: A functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment. J Consult Clin Psych. 1996;64:1152–1168. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.6.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trafton JA, Gifford EV. Behavioral reactivity and addiction The adaptation of behavioral response to reward opportunities. J Neuropsych Clin Neuros. 2008;20:23–35. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2008.20.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gifford EV, Kohlenberg BS, Hayes SC, et al. Acceptance-based treatment for smoking cessation. Behav Ther. 2004;35:689–705. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gifford EV, Ritsher JB, McKellar JD. Acceptance and relationship context: a model of substance use disorder treatment outcome. Addiction. 2006;101:1167–1177. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leyro TM, Zvolensky MJ, Bernstein A. Distress tolerance and psychopathological symptoms and disorders: A review of the empirical literature among adults. Psych Bull. 2010;136:576–600. doi: 10.1037/a0019712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zvolensky MJ, Baker KM, Leen-Feldner E, et al. Anxiety sensitivity: Association with intensity of retrospectively rated smoking-related withdrawal symptoms and motivation to quit. Cogn Behav Ther. 2004;33:114–125. doi: 10.1080/16506070310016969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zvolensky MJ, Farris SG, Schmidt NB, et al. The role of smoking inflexibility/avoidance in the relation between anxiety sensitivity and tobacco use and beliefs among treatment-seeking smokers. Exp Clin Psychopharm. 2014;22:229–237. doi: 10.1037/a0035306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buckner JD, Farris SG, Zvolensky MJ, et al. Dysphoria and smoking among treatment seeking smokers: The impact of smoking-related inflexibility/avoidance. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2014 doi: 10.3109/00952990.2014.927472. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farris SG, Zvolensky MJ, Blalock JA, et al. Negative affect and smoking motives sequentially mediate the effect of panic attacks on tobacco-relevant processes. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2014;40:230–239. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2014.891038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Farris SG, Zvolensky MJ, Schmidt Smoking-specific experiential avoidance cognition: Explanatory relevance to pre- and post-cessation nicotine withdrawal, craving and negative affect. Addict Behav. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.07.026. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Japuntich SJ, Leventhal AM, Piper ME, et al. Smoker characteristics and smoking-cessation milestones. Am J Preven Med. 2011;40:286–294. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gifford EV, Lillis J. Avoidance and inflexibility as a common clinical pathway in obesity and smoking treatment. J Health Psych. 2009;14:992–996. doi: 10.1177/1359105309342304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bonn-Miller MO, Zvolensky MJ, Johnson KA. Uni-morbid and co-occurring marijuana and tobacco use: Examination of concurrent associations with negative mood states. J Addict Dis. 2010;29:68–77. doi: 10.1080/10550880903435996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I disorders, research version, non-patient edition (SCIDI/NP) New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown RA, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, et al. Distress tolerance and duration of past smoking cessation attempts. J Abnorm Psychol. 2001;111:180–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, et al. The Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence: A revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Brit J Addict. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pomerleau C, Carton S, Lutzk M. Reliability of the Fagerstrom tolerance questionnaire and the Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence. Addict Behav. 1994;19:33–39. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)90049-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Saunders J, et al. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1992. AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Health Care, Revision, WHO Document No. WHO/PSA/92.4. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bonn-Miller MO, Zvolensky MJ. An evaluation of the nature of marijuana use and its motives among young adult active users. Am J Addiction. 2009;18:409–416. doi: 10.3109/10550490903077705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;47:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meyer TJ, Miller ML, Metzger RL. Development and validation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Behav Res Ther. 1990;28:487–495. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(90)90135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Behar E, Alcaine O, Zuellig AR, et al. Screening for generalized anxiety disorders using the Penn State Worry Questionnaire: A receiver operating characteristic analysis. J Behav Ther Exp Psy. 2003;34:25–43. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7916(03)00004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brown TA, Antony MM, Barlow DH. Psychometric properties of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire in a clinical anxiety disorders sample. Behav Res Ther. 1992;30:33–37. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(92)90093-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fresco DM, Menin DS, Heimberg RG, et al. Using the Penn State Worry Questionnaire to identify individuals with generalized anxiety disorder: A receiver operating characteristic analysis. J Behav Ther Exp Psy. 2003;34:283–291. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rundmo T, Smedslund G, Gotestam KG. Motivation for smoking cessation among the Norwegian public. Addict Behav. 1997;22:377–386. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(96)00056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Royce JM, Hymowitz N, Corbett K. Smoking-cessation factors among African American and Whites. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:220–226. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.2.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Macnee CL, Talsma A. Development and testing of the barriers to cessation scale. Nurs Res. 1995;44:214–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guildford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hayes AF. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun Monogr. 2009;76:408–420. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav Res Meth Instru C. 2004;36:717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Meth. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zvolensky MJ, Bernstein A. Cigarette smoking and panic psychopathology. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2005;14:301–305. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Feldner MT, Smith RC, Monson CM, et al. Initial evaluation of an integrated treatment for comorbid PTSD and smoking using a nonconcurrent, multiple-baseline design. Behav Ther. 2013;44:514–528. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hertzberg MA, Moore SD, Feldman ME. A preliminary study of bupropion sustained-release for smoking cessation in patients with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychopharm. 2001;21:94–98. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200102000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.MacPherson L, Tull MT, Matusiewicz AK. Randomized controlled trial of behavioral smoking cessation treatment for smokers with elevated depressive symptoms. J consult Clin Psych. 2010;78:55–61. doi: 10.1037/a0017939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McFall M, Saxon AJ, Malte CA, et al. Integrating tobacco cessation into mental health care for posttraumatic stress disorder. JAMA-J Am Med Assoc. 2010;304:2485–2493. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bricker JB, Mann SL, Marek PM, et al. Telephone-delivered acceptance and commitment therapy for adult smoking cessation: A feasibility study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12:454–458. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Korte KJ, Capron DW, Zvolensky MJ, Schmidt NB. The Fagerström scales: Does altering the scoring enhance the psychometric properties? Addict Behav. 2013;38:1757–1763. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.DeVellis RF. Scale development: Theory and applications. 2. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]