Abstract

Depression appears to be characterized by reduced neural reactivity to receipt of reward. Despite evidence of shared etiologies and high rates of comorbidity between depression and anxiety, this abnormality may be relatively specific to depression. However, it is unclear whether children at risk for depression also exhibit abnormal reward responding, and if so, whether risk for anxiety moderates this association. The feedback negativity (FN) is an event-related potential component sensitive to receipt of rewards versus losses that is reduced in depression. Using a large community sample (N=407) of 9-year old children who had never experienced a depressive episode, we examined whether histories of depression and anxiety in their parents were associated with the FN following monetary rewards and losses. Results indicated that maternal history of depression was associated with a blunted FN in offspring, but only when there was no maternal history of anxiety. In addition, greater severity of maternal depression was associated with greater blunting of the FN in children. No effects of paternal psychopathology were observed. Results suggest that blunted reactivity to rewards versus losses may be a vulnerability marker that is specific to pure depression, but is not evident when there is also familial risk for anxiety. In addition, these findings suggest that abnormal reward responding is evident as early as middle childhood, several years prior to the sharp increase in the prevalence of depression and rapid changes in neural reward circuitry in adolescence.

Abnormalities in neural reward circuitry may be a key feature underlying depressive disorders, particularly the core symptom of anhedonia (Naranjo, Tremblay, & Busto, 2001; Russo & Nestler, 2013). Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies have shown that compared to healthy controls, adults with depression exhibit reduced activation to rewards in striatal regions of the brain and are less likely to adjust their behavior in response to rewards (Eshel & Roiser, 2010; Henriques & Davidson, 2000; Pizzagalli et al., 2009; Pizzagalli, Jahn, & O'Shea, 2005; Smoski et al., 2009; Steele, Kumar, & Ebmeier, 2007). Older children and adolescents with depression also show abnormal reward decision-making in behavioral tasks and reduced striatal responses to reward (Forbes et al., 2009; Forbes et al., 2006).

In order to determine if an abnormality may be a vulnerability marker, rather than simply a concomitant of the disorder, it should be evident prior to onset and in healthy individuals at elevated risk (Ingram & Luxton, 2005). Two behavioral studies have reported that abnormal reward-related decision-making prospectively predicts depression in late childhood and adolescence (Forbes, Shaw, & Dahl, 2007; Rawal, Collishaw, Thapar, & Rice, 2012). In addition, several studies have reported that offspring of depressed parents, a group at elevated risk for depression (Hammen, 2009), exhibit abnormal neural response to reward. Gotlib and colleagues (2010) found that compared to girls with no parental history of depression, never-depressed girls (mean age of 12 years) with maternal histories of recurrent depression showed less activation in putamen and left insula and greater activation in right insula when anticipating rewards. Moreover, McCabe, Woffindale, Harmer, and Cowen (2012) reported that adolescent and young adult offspring of depressed parents exhibited reduced orbitofrontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex responses to reward.

These studies suggest that abnormalities in response to reward may be a vulnerability marker and precede the onset of depression. However a number of issues remain to be elucidated. First, although abnormal reward processing has been observed in offspring of depressed parents, the influence of parental anxiety has not been examined. Anxiety and depressive disorders often co-occur, with 50% or more depressed adults and youth exhibiting comorbid anxiety disorders (Fava et al., 2000; Kessler, Avenevoli, & Merikangas, 2001; Sanderson, Beck, & Beck, 1990). Moreover, there is substantial overlap in the genetic influences on depressive and anxiety disorders (Hettema, 2008). Nonetheless, reward-related abnormalities may be relatively specific to depression. Low approach-related motivation and positive affect are much more characteristic of depression than anxiety (Kasch, Rottenberg, Arnow, & Gotlib, 2002; Watson & Naragon-Gainey, 2010). In addition, a recent electroencephalogram (EEG) study found evidence of reduced left frontal EEG asymmetry, hypothesized to reflect approach motivation, while anticipating reward in adults with major depressive disorder (MDD) and their relatives, but not in adults with panic disorder and their relatives (Nelson et al., 2013; Shankman et al., 2013). In fact, there is some evidence that anxiety may be associated with heightened neural processing of reward under certain conditions. Adolescents with social phobia showed increased striatal activation during anticipation of high magnitude rewards (Guyer et al., 2012). Moreover, increased striatal activation during anticipation of rewards moderated the association between early childhood inhibited temperament and anxiety symptoms in adolescence (Pérez-Edgar et al., 2013). It is unclear, however, whether parental anxiety predicts reward processing in offspring, and if so, whether it influences the association between risk for depression and reward reactivity. Given the distinction between reward processing and depression compared to anxiety, it is possible that the effect of parental anxiety may attenuate the association between parental depression and reduced reward reactivity in offspring.

Second, little is known about how specific features of parental depression relate to reward processing in offspring. More than half of adults with depression report relatively normal levels of pleasure (Fawcett, Clark, Scheftner, & Gibbons, 1983; Oei, Verhoeven, Westenberg, Zwart, & Van Ree, 1990; Pelizza & Ferrari, 2009), suggesting depression may be heterogeneous with regard to reward reactivity. Melancholia is a subtype of depression that appears to aggregate in families (Schreier et al., 2006) and is characterized by anhedonia and lack of mood reactivity to positive events. Anhedonia is also associated with greater severity of depression (Pelizza & Ferrari, 2009), and severity aggregates in families (Schreier et al., 2006). Thus, it is possible that offspring of parents with melancholic or more severe depression will exhibit particularly diminished reactivity to reward.

Third, most research on reward processing among youth at risk for depression has used samples with a broad range of ages, often spanning middle childhood through adolescence or young adulthood. Yet, there is evidence of developmental changes in reward processing across this range. For example, in one study, ventral striatal reactivity to receipt of rewards increased between ages 10–12 and ages 14–15 (Van Leijenhorst et al., 2010). Although developmental changes in neural systems of reward processing in adolescence have been proposed as a key feature underlying the increased prevalence of depression in adolescence (Davey, Yücel, & Allen, 2008), it is unclear whether abnormal reward processing is associated with risk for depression before adolescence. Determining whether this abnormality emerges earlier in development could have important implications for understanding developmental processes in depression and for early identification and intervention.

Previous research has differentiated between two phases of reward processing: the anticipation phase and the feedback, or consummatory, phase (Pizzagalli et al., 2009; Richards, Plate, & Ernst, 2013). The feedback negativity (FN) is an event-related potential (ERP) component that reflects the feedback phase of reward processing. The FN presents as a relative negativity following negative outcomes compared to positive outcomes (e.g., rewards) and peaks approximately 250–300 ms after feedback over frontocentral recording sites (Foti, Weinberg, Dien, & Hajcak, 2011; Gehring & Willoughby, 2002; Hajcak, Moser, Holroyd, & Simons, 2006; Santesso, Dzyundzyak, & Segalowitz, 2011). The FN is often examined as the difference between the mean amplitude on loss relative to gain trials to isolate neural sensitivity to outcome valence (Dunning & Hajcak, 2007; Foti et al., 2011). More negative values for the difference score indicate greater differentiation between gains and losses (i.e., increased reactivity), and this difference score has been related to behavioral and self-report measures of reward sensitivity (Bress & Hajcak, 2013), as well as reward-related neural activity using fMRI (Carlson, Foti, Mujica-Parodi, Harmon-Jones, & Hajcak, 2011). Functionally, the FN appears to reflect a reward-related signal used to reinforce behaviors that lead to desirable outcomes (Holroyd & Coles, 2002; Weinberg, Luhmann, Bress, & Hajcak, 2012)

Depressive symptoms have been associated with a reduced FN (i.e., hyposensitivity) to monetary gains vs. losses in older youth and adults (Bress, Smith, Foti, Klein, & Hajcak, 2012; Foti & Hajcak, 2009), and this association appears to be specific to symptoms of depression rather than anxiety (Bress, Meyer, & Hajcak, 2013). In addition, the FN may reflect vulnerability for depression, as a reduced FN to monetary rewards and losses in a small sample of adolescent girls prospectively predicted the development of depressive episodes and increases in depressive symptoms over the next two years (Bress, Foti, Kotov, Klein, & Hajcak, 2013). It remains unclear, however, if parental depression is associated with a blunted FN in children, and if so, whether it is moderated by parental anxiety.

In order to evaluate the FN as a vulnerability marker for depression, we investigated whether maternal or paternal histories of depressive or anxiety disorders predicted relative reactivity to rewards versus losses in a large community sample of 9-year-old children who had never experienced a depressive episode, while controlling for child symptoms of depression and anxiety. We chose to focus on middle childhood in order to determine whether abnormalities in neural reward systems are already apparent prior to the developmental changes in reward systems and increased prevalence of depression in adolescence (Davey et al., 2008; Van Leijenhorst et al., 2010). We hypothesized that parental depression would be associated with a blunted FN in offspring (i.e., reduced differentiation between rewards and losses). Given the weaker associations of low approach motivation and positive affectivity with anxiety than depression (Shankman et al., 2013; Watson & Narragon-Gainey, 2010), and previous work linking some forms of anxiety to increased striatal activation during reward anticipation (Guyer et al., 2012; Pérez-Edgar et al., 2013), we hypothesized that parental anxiety would be associated with a normal or enhanced FN in offspring. In addition, we tentatively posited that the effect of parental anxiety would attenuate the association between parental depression and the FN in offspring, such that a blunted FN would be apparent only among children of parents with pure depression (i.e., without comorbid anxiety). Finally, we conducted exploratory analyses to evaluate whether parental melancholia or depression severity were associated with an even greater reduction of the FN in offspring of depressed parents.

Method

Participants

Participants in the current study are part of a larger prospective longitudinal study (see Olino et al., 2010). The sample was initially recruited using commercial mailing lists when the children were 3 years old (N=559). Children with no significant medical conditions or developmental disabilities and living with at least 1 biological, English-speaking parent were eligible to participate. Only 1 child per family was included. Parents and children were re-assessed when the children were approximately six years old, at which time an additional sample of 50 children were recruited through advertisements in the community in order to increase ethnic and racial diversity. The sample was evaluated again at age 9, at which time the reward task was administered. A total of 468 children completed the reward task. Data for 42 children were excluded for poor EEG data quality, and psychopathology data were missing for 8 parents and 1 child. In addition, data were excluded for 6 children due to a parental history of bipolar disorder and 4 children due to a lifetime diagnosis of a depressive disorder. Thus, the final sample in this report consisted of 407 children. The sample was 45% female and mean age at the time of the EEG assessment was 9.18 years (SD=.40). With regard to ethnicity, the sample was 11.1% Hispanic. With respect to race, the sample was 89.7% Caucasian, 7.6% African American, and 2.7% Asian.

Procedure

When the children were 3 years old, both biological parents were asked to complete a semi-structured diagnostic interview to assess their own lifetime history of psychopathology. The children were invited back to the laboratory as close as possible to their 9th birthday and completed the EEG assessment. EEG sensors were attached and children were instructed that they could win up to $5 in the reward task. Children then completed 5 practice trials prior to the start of the actual task. Children and parents also completed a semi-structured diagnostic interview to assess lifetime child psychopathology, and parents completed a semi-structured diagnostic interview assessing their own psychopathology since the initial evaluation.

Measures

Parental psychopathology

When children entered the study at age 3 (or age 6 for the supplementary sample), biological mothers and fathers were interviewed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV non-patient version (SCID; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1996). An advanced doctoral student in clinical psychology and a masters-level clinician conducted the interviews by telephone, which generally yields comparable results to face-to-face interviews (Rohde, Lewinsohn, & Seeley, 1997; Sobin, Weissman, Goldstein, & Adams, 1993). The other rater derived independent diagnoses from recorded interviews; interrater reliability (kappa) was 0.93 for lifetime depressive disorder and 0.91 for lifetime anxiety disorder (n=30). Interrater reliability could not be calculated for melancholia because there were too few cases in the reliability sample.

For the age 9 assessment, advanced doctoral students in clinical psychology and a masters-level clinician administered the SCID to biological mothers and fathers to assess psychopathology in the years since the initial assessment. One parent (generally the mother) was interviewed face-to-face; the other parent was interviewed by telephone. An expert rater with over 15 years of experience administering the SCID derived independent diagnoses from videotaped interviews. Interrater reliability (kappa) was 0.91 for depressive disorders, 0.73 for anxiety disorders, and .067 for melancholia (n=45). According to Landis and Koch (1977), kappas between 0.41 and 0.60 indicate moderate; 0.61–0.80 substantial, and 0.81 and greater almost perfect, agreement. At both assessments, SCID interviewers were supervised individually by a licensed clinical psychologist.

To measure severity of MDD, parents were asked about number of MDD symptoms (range=0–9), impairment, and treatment for their worst episode. Impairment and treatment were each rated on a 3-point scale (0=no significant impairment in major role at home or school, 1=impairment but still able to function, 2=incapacitation in major role; 0=no treatment, 1=outpatient pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy, 2=hospitalization). For each assessment, a composite severity score was calculated as the sum of z-scores for number of MDD symptoms, impairment, and treatment. When parents met criteria for MDD during the intervals covered by both SCID assessments, the higher composite severity score was used for analysis.

In cases where completion of the SCID with one parent was not possible, family history information was obtained from the other parent using a semi-structured interview (Andreasen, Endicott, Spitzer, & Winokur, 1977). Diagnoses for 24 fathers were derived solely using the family history method. Diagnoses from the initial and age 9 diagnostic assessments were combined to yield lifetime diagnoses.

Child psychopathology

At the age 9 assessment, 1 parent (generally the mother) and the child were interviewed using the DSM-IV version of the Schedule of Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children - Present and Lifetime (K-SADS-PL; Axelson, Birmaher, Zelazny, Kaufman, & Gill, 2009). Advanced doctoral students in clinical psychology and a masters-level clinician administered the K-SADS first to the parent and then to the child. Further information was then obtained to reconcile discrepancies. Summary ratings for each symptom were derived based on the combination of parent and child reports. Lifetime symptoms of depressive disorders and anxiety disorders were rated on a 3-point scale (0=Not present; 1=Subthreshold; 2=Threshold) and depression and anxiety items from the screener were summed to create dimensional scores that were used as covariates in the current analyses (depression dimensional scores could range from 0–16 and anxiety dimensional scores could range from 0–42). The screener was used to compute dimensional scores because other symptoms were assessed only for children with at least 1 symptom in the screener. Administration of the K-SADS was supervised in a group format by an experienced child psychiatrist and licensed clinical psychologist. To assess interrater reliability, a second rater independently derived ratings from videotapes for 74 participants. Intraclass correlations (ICCs) for dimensional scores of depressive and anxiety symptoms were 0.81 and 0.82, respectively. As our goal was to determine whether reward responding abnormalities are present prior to the onset of a depressive disorder, children meeting criteria for lifetime MDD or dysthymic disorder were excluded from analyses (n=4).

Reward task

The reward task was similar to a version used in previous studies (Bress et al., 2012; Dunning & Hajcak, 2007; Foti & Hajcak, 2009). The task consisted of 60 trials, presented in three blocks of 20 trials. At the beginning of each trial, participants were presented with an image of two doors and instructed to choose one door by clicking the left or right mouse button. The doors remained on the screen until the participant responded. Next, a fixation mark (+) appeared for 1000 ms, and feedback was presented on the screen for 2000 ms. Participants were told that they could either win $0.50 or lose $0.25 on each trial. A win was indicated by a green “↔,” and a loss was indicated by a red “↓.” Next, a fixation mark appeared for 1500 ms and was followed by the message “Click for the next round”, which remained on the screen until the participant responded and the next trial began. Across the task, 30 win and 30 loss trials were presented in a random order.

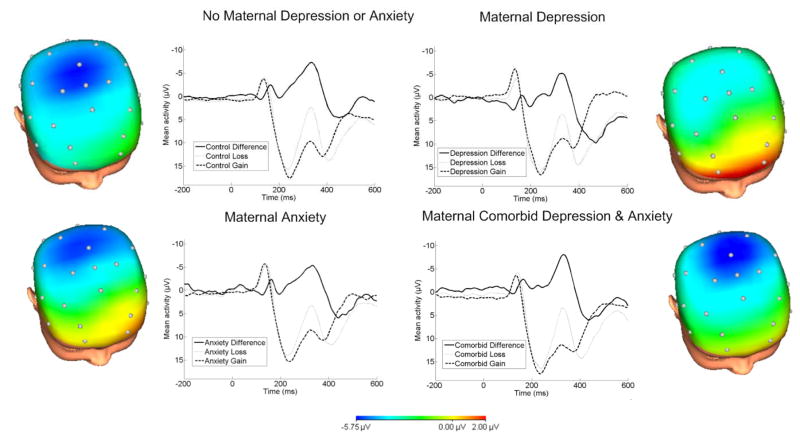

EEG Data Acquisition & Processing

The continuous EEG was recorded using a 34-channel Biosemi system based on the 10/20 system (32 channel cap with Iz and FCz added). Two electrodes were placed on the left and right mastoids, and the electrooculogram (EOG) from eye blinks and movements was recorded from facial electrodes above and below the left eye, to the left of the left eye and to the right of the right eye. The Common Mode Sense and the Driven Right Leg electrodes served as the ground electrode during data acquisition. The data were digitized at 24-bit resolution with a LSB value of 31.25nV and a sampling rate of 1024 Hz, using a low-pass fifth order sinc filter with -3dB cutoff points at 208 Hz. Off-line analysis was performed using Brain Vision Analyzer software (Brain Products). Data were re-referenced to an average mastoid reference, band-pass filtered with cutoffs of 0.1 and 30 Hz, segmented for each trial 200 ms before feedback onset and continuing for 600 ms after onset. The EEG was corrected for eye blinks (Gratton, Coles, & Donchin, 1983). Artifact rejection was completed using semi-automated procedures and the following criteria: a voltage step of more than 50 μV between data points, a voltage difference of 300 μV within a trial, and a voltage difference of less than .50 μV within 100 ms intervals. Visual inspection was used to remove additional artifacts. Data were baseline corrected using the 200 ms interval prior to feedback. ERPs were averaged across win and loss trials, and analyses focused on the FN difference score, which was calculated as the mean amplitude on loss trials minus the mean amplitude on gain trials. The FN was scored as the mean amplitude 275–375 ms following feedback, where the loss minus gain difference wave was maximal (Figure 1). In order to reduce noise associated with a recording at a single electrode, the FN was scored as the average activity across frontocentral sites (i.e., Fz, FCz, and Cz), which is consistent with previous research (e.g., Bress et al., 2013; Bress et al., 2012) and the scalp distribution of the difference wave (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

ERPs (negative up) at FCz for losses, gains and the difference, and scalp distributions depicting the loss-gain difference for children with no maternal history of anxiety or depression (top left), maternal depression only (top right), maternal anxiety only (bottom left), and maternal comorbid depression and anxiety (bottom right). Maternal depression was associated with a reduced feedback negativity (FN) only when there was no maternal history of anxiety.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Table 1 presents demographic variables and associations with maternal and paternal psychopathology. Overall, 38.1% (n=155) of children had mothers with lifetime histories of depressive disorders (24.1% MDD, 7.4% dysthymic disorder, 6.6% both) and 17.2% (n=70) had fathers with lifetime histories of depressive disorders (10.3% MDD, 2.7% dysthymic disorder, 4.2% both). Rates of current depression in parents were low, with 0.7% of mothers (n=3) and 0.5% of fathers (n=2) meeting criteria for depression in the past month. With regard to anxiety disorders, 38.8% (n=158) of children had mothers with lifetime anxiety disorders and 20.9% (n=85) had fathers with lifetime anxiety disorders. Anxiety disorders among mothers included specific phobia (16.7%), social phobia (14.7%), panic disorder (9.8%), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD; 6.1%), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; 5.2%), obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD; 3.2%), and agoraphobia without panic disorder (1.5%). Anxiety disorders among fathers included social phobia (10.1%), specific phobia (5.9%), GAD (4.2%), panic disorder (3.2%), OCD (2.5%), PTSD (1.5%), and agoraphobia without panic (1.2%). In total, 20.8% (n=85) of children had mothers with histories of both depression and anxiety and 8.3% (n=34) had fathers with histories of both depression and anxiety. In addition, 22.1% (n=90) of children had mothers with histories of substance abuse or dependence (12.8% alcohol only) and 44.0% (n=179) had fathers with histories of substance abuse or dependence (26.0% alcohol only).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and Pearson’s correlations/phi coefficientsa between demographics, predictor variables, and the feedback negativity (FN)

| Variable | Mean(SD)/% | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 9.18(0.40) | - | ||||||||||

| 2. Sex (% female) | 44.5% | −.01 | - | |||||||||

| 3. Race (% Caucasian) | 89.7% | .07 | .09 | - | ||||||||

| 4. Child depression symptoms | 0.41(1.00) | .00 | −.11* | .00 | - | |||||||

| 5. Child anxiety symptoms | 3.39(3.58) | .02 | −.02 | −.03 | .14** | - | ||||||

| 6. Mother education | 55.8%b | −.04 | .00 | .14** | −.08 | −.12* | - | |||||

| 7. Father education | 43.5%b | −.01 | −.08 | .13* | −.06 | −.09 | .39*** | - | ||||

| 8. Maternal depression | 38.1% | .01 | .02 | .03 | .06 | .22*** | −.03 | −.12* | - | |||

| 9. Maternal anxiety | 38.8% | .00 | .01 | .06 | .05 | .20*** | −.10† | −.11* | .26*** | - | ||

| 10. Paternal depression | 17.2% | −.02 | .00 | −.08 | .05 | .06 | .06 | −.07 | .11* | .09 | - | |

| 11. Paternal anxiety | 20.9% | .01 | −.02 | .04 | −.08 | −.02 | .16** | .05 | .17** | .05 | .31*** | - |

| 12. Loss-Gain FN | −4.44(7.61) | .03 | .17** | .02 | −.04 | .04 | .03 | −.02 | .05 | −.02 | −.05 | −.05 |

p<.001;

p<.01;

p<.05;

p=.05

Pearson’s correlations were calculated to examine associations involving at least 1 continuous variable; phi coefficients were calculated to evaluate associations between 2 categorical variables

Percentage of parents completing 4-year college or higher

With regard to child psychopathology, 20.6% (n=84) of children met criteria for a lifetime diagnosis of an anxiety disorder. In addition, 9.1% (n=37) met criteria for lifetime attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and 3.7% (n=15) for oppositional defiant disorder (ODD).

Associations between variables are presented in Table 1. Male children showed slightly higher rates of child depressive symptoms than females, though children’s level of depressive symptoms were low overall. Mothers with a history of depressive or anxiety disorders had children with higher rates of anxiety symptoms, but no significant associations between parental psychopathology and offspring depressive symptoms were observed. Higher rates of maternal completion of college were linked to lower child symptoms of anxiety, but higher rates of paternal anxiety disorders. Paternal completion of college was negatively related to maternal depressive and anxiety disorders. No significant effects of parental education on the FN were observed. As would be expected, distributions of maternal and paternal psychopathology differed as a function of other parental diagnoses.

Effects of Parental Depression and Anxiety on the FN

A hierarchical multiple regression analysis was calculated to examine effects on children’s FN. All categorical variables were dummy coded as 0 and 1. Child characteristics (i.e., age in months, sex, lifetime depressive symptoms, and lifetime anxiety symptoms) were entered in Step 1, followed by parental psychopathology (i.e., maternal depressive, maternal anxiety, paternal depressive, and paternal anxiety disorder) in Step 2 and interactions between diagnoses in each parent to examine comorbidity in Step 3. Results are presented in Table 2. We initially tested the model including the four cross-parent interactions (i.e., maternal depression X paternal depression, maternal anxiety X paternal anxiety, maternal depression X paternal anxiety, and maternal anxiety X paternal depression). None of the interactions were significant (ps>.40); therefore we removed these interactions from the final model to simplify the presentation of results.

Table 2.

Hierarchical regression with child characteristics, parental psychopathology, and interactions between parental depression and anxiety predicting children’s feedback negativity (FN)

| Predictor | b(SE) | β |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Child Characteristics | R2=.03, F(4, 402)=3.33, p<.05 | |

|

| ||

| Age (months) | .05(.08) | .03 |

| Sex | −2.54(.76) | .17** |

| Child depression symptoms | −.17(.38) | −.02 |

| Child anxiety symptoms | .07(.11) | .03 |

|

| ||

| 2. Parental Psychopathology Variables | Change R2=.01, F(4, 398)=0.82, p>.05 | |

|

| ||

| Maternal Depression | 2.52(1.09) | .16* |

| Maternal Anxiety | .89(1.06) | .06 |

| Paternal Depression | −1.32(1.34) | −.07 |

| Paternal Anxiety | −1.13(1.16) | −.06 |

|

| ||

| 3. Interactions | Change R2=.01, F(2, 396)=2.45, p=.09† | |

|

| ||

| Maternal Depression X Maternal Anxiety | −3.43(1.61) | −.18* |

| Paternal Depression X Paternal Anxiety | 1.15(2.15) | .04 |

|

| ||

| Total model R2=.05, F(10, 396)=2.16, p<.05 | ||

p<.01;

p<.05

When the non-significant paternal depression X paternal anxiety interaction is removed from Step 3, R2 change is significant (p<.05)

The effect of sex was significant, t(405)=3.43, p=.001, with boys showing larger FNs overall compared to girls. The effects of child age, child depressive symptoms, child anxiety symptoms, maternal anxiety, paternal anxiety and paternal depression were not significant. The effect of maternal depression was significant in the final model, t(405)=2.32, p=.02, but was qualified by a significant interaction with maternal anxiety, t(405)=−2.14, p=.03 (Figures 1 and 2). The interaction between paternal depression and paternal anxiety was not significant.

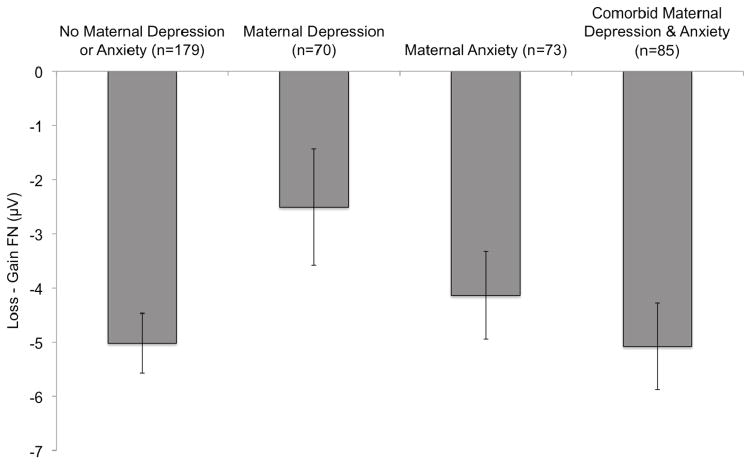

Figure 2.

Bar graph depicting means and standard errors of the loss minus gain FN difference score at the Fz, FCz, and Cz pooling for each of the maternal depression/anxiety groups. More negative FN difference scores correspond to enhanced reactivity to monetary losses relative to gains.

To interpret the maternal depression by maternal anxiety interaction, dummy coded variables were computed for each of the maternal psychopathology groups (i.e., no depression or anxiety, pure depression, pure anxiety, and comorbid depression and anxiety) and their associations with the FN were compared. Children of mothers with a history of pure depression showed a reduced FN relative to children of mothers with no history of depression or anxiety, t(405)=2.35, p=.02, and mothers with comorbid depression and anxiety, t(405)=2.13, p=.03. The comparison between children of mothers with pure depression and mothers with pure anxiety did not reach significance, t(405)=1.34, p=.18. Children of mothers with no history of depression or anxiety, mothers with histories of pure anxiety, and mothers with comorbid depression and anxiety did not significantly differ from one another (ps>.42).

The main regression analysis was repeated separately on children’s mean activity following losses and mean activity following rewards. The effects of parental psychopathology, including the maternal depression X maternal anxiety interaction, did not reach significance in either analysis, suggesting that the effect is apparent in offspring only for the relative response to rewards and losses.

Because the main effect of sex was significant, the hierarchical multiple regression model was repeated with the addition of the two- and three-way interactions between sex, maternal depression and maternal anxiety in the final step. None of the two- or three-way interactions with sex were significant (ps>.58).

The model was also calculated examining current child symptoms of depression and anxiety on the K-SADS (instead of lifetime), as well as child-reported symptoms from the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs et al., 1992) and Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED; Birmaher et al., 1997). No substantive changes in the results were observed with either model. Lastly, to evaluate whether specific parental anxiety disorders predict the FN, we tested an additional model with maternal and paternal depression, specific phobia, social phobia, OCD, PTSD, and GAD in Step 2. None of the effects of specific parental anxiety disorders reached significance (ps>.13).

Melancholia and Depression Severity

Additional analyses were computed to evaluate whether maternal melancholic features and MDD severity influence children’s FN. These analyses were limited to the 125 children of mothers with a history of MDD. Because child sex was significantly related to their FN in the previous analyses and maternal melancholia predicted greater child symptoms of depression, r(123)=.18, p=.04, child sex and children’s symptoms of depression were included as covariates.

Mothers with a history of MDD were divided into two groups: those with a history of melancholic features (n=58) and those with no history of melancholia (n=67). A hierarchical multiple regression analysis was calculated with child sex and depressive symptoms in Step 1, and maternal melancholia and maternal anxiety in Step 2. Neither maternal melancholia, β=−.06; t(123)=−.63, p>.05, nor maternal anxiety, β=−.15; t(123)=−1.76, p=.08, were significantly related to children’s FN.

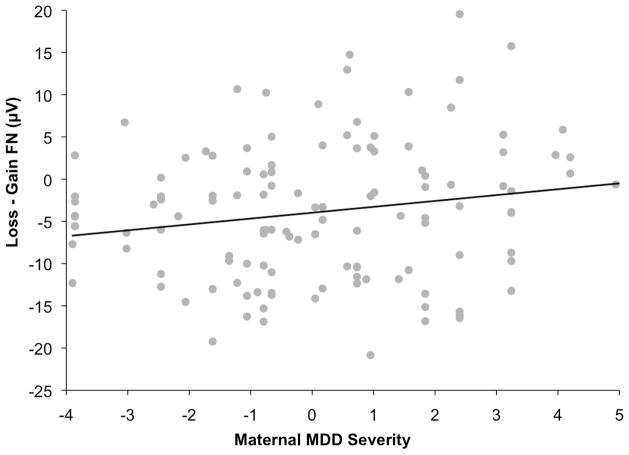

Next, the model was repeated with composite scores for maternal MDD severity replacing melancholia. Greater severity of maternal depression was associated with blunting of the FN in offspring, β=.19; t(123)=2.11, p=.04 (Figure 3), and maternal comorbid anxiety was associated with a relatively enhanced FN, β=−.18; t(123)=−2.06, p=.04.

Figure 3.

Scatter plot depicting the association between maternal MDD severity and the loss minus gain FN difference score. Greater depression severity is associated with a more blunted (i.e., less negative) FN difference score.

Lastly, we evaluated whether timing of maternal depression (prior to the child’s birth versus during the child’s life) influenced the FN. The effect of timing was not significant (p>.94).

Discussion

We found that the FN to monetary rewards and losses is reduced in children of mothers with a lifetime history of depression, but only if the mothers have no history of anxiety disorders. Thus, offspring of mothers with a history of pure depression exhibited significantly smaller FNs than offspring of mothers with no history of depressive or anxiety disorders and offspring of mothers with a history of both depressive and anxiety disorders. Although children of mothers with pure depression also exhibited a smaller FN than children of mothers with pure anxiety, this comparison was not statistically significant. Finally, among offspring of mothers with a history of MDD, greater severity of maternal depression during the worst lifetime episode was associated with greater blunting of children’s FN. These results are consistent with previous fMRI studies that found abnormal reward reactivity among offspring of depressed parents (Gotlib et al., 2010; McCabe et al., 2012), but extend this work by using electrocortical measures, focusing on younger children, and examining the effect of parental comorbid anxiety and depression severity on processing of reward feedback.

The FN is thought to reflect reinforcement learning processes (Holroyd & Coles, 2002), and the FN difference score has previously been linked both to self-reported tendency to engage in reward-related behavior and to behavioral measures of bias to make responses that are frequently rewarded (Bress & Hajcak, 2013). Thus, children with a reduced FN may exhibit less sensitivity to reward or impaired ability to learn contingencies associated with rewarding versus non-rewarding outcomes, and therefore decreased likelihood to engage in rewarding behaviors, which may increase risk for developing depression (Dimidjian, Barrera, Martell, Muñoz, & Lewinsohn, 2011). Consistent with this, it has previously been reported that a reduced FN predicts the onset of MDD in a small sample of adolescent girls (Bress et al., 2013). However, additional prospective studies are needed to determine if a blunted FN in childhood predicts the development of depression and whether abnormalities in the processing of reward feedback mediate the intergenerational transmission of depression.

Our finding that only the offspring of depressed mothers with no history of anxiety exhibited a blunted FN raises the possibility that reduced responding to reward feedback increases risk specifically for pure (without comorbid anxiety) depression. Children with maternal histories of comorbid depression and anxiety, who are at heightened risk for both disorders (Klein, Lewinsohn, Rohde, Seeley, & Olino, 2005; Weissman, Leckman, Merikangas, Gammon, & Prusoff, 1984), exhibited a typical pattern of reward processing. These results are consistent with evidence that depression with and without prominent anxiety have distinct neurobiological profiles (for a review see Ionescu, Niciu, Mathews, Richards, & Zarate, 2013).

We also found that among offspring of mothers with a history of MDD, more severe maternal depression was associated with a particularly blunted FN to rewards versus losses. As greater severity of parental depression is associated with higher rates of depression in offspring (Hammen & Brennan, 2003; Keller et al., 1986), this finding suggests that children with a reduced FN may be a subgroup at particularly high risk. The lack of an association between maternal melancholic depression and the FN in offspring was surprising because anhedonia and loss of mood reactivity to positive experiences are key features of melancholia. However, the validity of self-reports of melancholic features has been questioned (Parker et al., 1990), and these concerns are compounded when respondents are reporting on past episodes. Thus, our assessment of melancholia may not have been sensitive or specific enough to detect effects of parental melancholic depression on offspring responses to reward.

Importantly, this study is among the first to examine neural measures of reward processing as vulnerability markers for depression prior to adolescence. Developmental changes in brain reward systems may be a key feature underlying the rapid increase in the prevalence of depression beginning in adolescence (Davey, Yücel, & Allen, 2008). Our findings suggest that children at high risk for depression may begin to show abnormalities in the processing of reward feedback even before adolescence.

It should be noted that the current results were specific to the loss minus gain FN difference score, which has been used in previous FN studies to isolate neural activation specific to the valence of feedback (Bress & Hajcak, 2013; Carlson et al., 2011; Dunning & Hajcak, 2007; Foti et al., 2011). It is possible that reactivity to only loss or gain trials could drive effects; however, we did not find any significant effects of parental psychopathology on loss or gain trials when examined separately.

In contrast to effects of maternal depression, we did not find significant effects of paternal depression on sensitivity to rewards versus losses in offspring. This is consistent with our previous findings with this sample at earlier ages indicating that maternal, but not paternal, depression was associated with reduced neural reactivity to emotional faces and poorer emotion recognition skills in offspring (Kujawa et al., in press; Kujawa, Hajcak, Torpey, Kim, & Klein, 2012). It is also consistent with the weaker effects of paternal depression on child psychopathology (Brennan, Hammen, Katz, & Le Brocque, 2002; Connell & Goodman, 2002). It is important to note, however, that the rate of depression in adult males is lower than in females (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2002); consequently, our sample included a larger number of mothers than fathers with depression. In addition, diagnoses for a small proportion (5.9%) of fathers were derived using family history interviews, which have only moderate sensitivity (Andreasen et al., 1977). Thus, we cannot exclude the possibility that the lack of effects for paternal depression is due to methodological factors.

Other limitations of the current findings should be noted. The effect of maternal depression on the FN in offspring was relatively small; the entire model including covariates accounted for only 5% of the variance in the FN. However, small effects would be expected for several reasons. First, as discussed by Patrick et al. (2013), associations between neurophysiological and behavioral measures are typically small in magnitude owing to the substantial difference in methods. Second, as many offspring of depressed mothers will not develop depression and a number of offspring of mothers with no history of depression will become depressed (Hammen, 2009), the effect sizes of maternal depression on offspring psychopathology are generally small (see meta-analysis by Goodman et al., 2011). Finally, depressive disorders are characterized by etiological heterogeneity and equifinality; hence, as our findings suggest, abnormal reward processing is likely to be evident in only a subgroup of individuals with, or at risk for, depression.

In addition, the comparison between offspring of mothers with pure depression and pure anxiety did not reach significance, though the direction of means was consistent with a reduced FN among the pure depression group. It is important to note that we did not find evidence of an enhanced FN among offspring of mothers with pure anxiety disorders. Though previous research has linked anxiety to increased striatal activation during anticipation of large rewards (Guyer et al., 2012; Pérez-Edgar et al., 2013), it is possible that this effect is specific to anticipation of reward and is not captured by the FN, which reflects the feedback phase of reward processing. Also, the effects of anxiety may only be apparent when there is greater variability in the magnitude of reward and loss outcomes.

We did not find elevated rates of depressive symptoms in children of depressed parents; however, consistent with previous studies, maternal depression was associated with an increased level of anxiety symptoms in offspring (Warner, Mufson, & Weissman, 1995; Weissman et al., 2006). The lack of association between parental depression and child depressive symptoms is likely due to the low level of depressive symptoms in our sample owing to the young age of the children and the fact that we excluded those who had already developed depressive disorders.

Lastly, in the current study, males showed greater reactivity to rewards versus losses than females. In self-report studies of adults, males tend to report greater reward sensitivity (Li, Huang, Lin, & Sun, 2007; Torrubia, Avila, Moltó, & Caseras, 2001), and our study extends that finding to neural measures in children. It has been suggested that there may be sex differences in vulnerability factors prior to adolescence that contribute to the sharper rise in rates of depression in females than males following puberty (Hyde, Mezulis, & Abramson, 2008; Nolen-Hoeksema & Girgus, 1994). Reduced neural sensitivity to rewards and losses may represent an example of a sex difference in a vulnerability factor that is evident prior to adolescence. However, additional research is needed to evaluate this possibility.

In conclusion, this is the first study to directly compare the effects of parental depression and anxiety on reward processing in offspring. The offspring of mothers with a history of depression but no history of anxiety exhibited blunted neural reactivity to reward and loss feedback. Moreover, among children of depressed mothers, greater severity of maternal depression was related to greater blunting of the FN. As these children are several years away from entering the period of risk for depression and have never experienced a depressive episode, these findings suggest that the FN to reward feedback may be a vulnerability marker that precedes the onset of some forms of depression. The processes responsible for these effects may involve genetic influences or interactions with mothers who also have abnormal reward processing. Regardless, these results highlight the importance of considering comorbidity between anxiety and depression and depression severity in examining neural correlates and vulnerability markers.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grants RO1 MH069942 to Daniel N. Klein, R03 MH094518 to Greg Hajcak Proudfit, and F31 MH09530701 to Autumn Kujawa.

References

- Andreasen NC, Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Winokur G. The family history method using diagnostic criteria: Reliability and validity. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1977;34(10):1229–1235. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1977.01770220111013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelson D, Birmaher B, Zelazny J, Kaufman J, Gill MK. University of Pittsburgh Department of Psychiatry Web site. Advanced Centre for Intervention and Services Research, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic; 2009. The Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia--Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL) 2009 Working Draft. Available at: http://www.psychiatry.pitt.edu/research/tools-research/ksads-pl-2009-working-draft. [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Khetarpal S, Brent D, Cully M, Balach L, Kaufman J, Neer SM. The Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): Scale Construction and Psychometric Characteristics. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(4):545–553. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199704000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan PA, Hammen C, Katz AR, Le Brocque RM. Maternal depression, paternal psychopathology, and adolescent diagnostic outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(5):1075–1085. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.70.5.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bress JN, Hajcak G. Self-report and behavioral measures of reward sensitivity predict the feedback negativity. Psychophysiology. 2013;50(7):610–616. doi: 10.1111/psyp.12053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bress JN, Meyer A, Hajcak G. Differentiating anxiety and depression in children and adolescents: Evidence from event-related brain potentials. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2013:1–12. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.814544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bress JN, Smith E, Foti D, Klein DN, Hajcak G. Neural response to reward and depressive symptoms in late childhood to early adolescence. Biological Psychology. 2012;89:156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson JM, Foti D, Mujica-Parodi LR, Harmon-Jones E, Hajcak G. Ventral striatal and medial prefrontal BOLD activation is correlated with reward-related electrocortical activity: A combined ERP and fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2011;57(4):1608–1616. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell AM, Goodman SH. The association between psychopathology in fathers versus mothers and children's internalizing and externalizing behavior problems: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128(5):746–773. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.5.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey CG, Yücel M, Allen NB. The emergence of depression in adolescence: Development of the prefrontal cortex and the representation of reward. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2008;32(1):1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimidjian S, Barrera M, Martell C, Muñoz RF, Lewinsohn PM. The origins and current status of behavioral activation treatments for depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2011;7:1–38. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032210-104535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunning JP, Hajcak G. Error-related negativities elicited by monetary loss and cues that predict loss. NeuroReport. 2007;18(17):1875–1878. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3282f0d50b. doi:1810.1097/WNR.1870b1013e3282f1870d1850b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshel N, Roiser JP. Reward and punishment processing in depression. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;68(2):118–124. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava M, Rankin MA, Wright EC, Alpert JE, Nierenberg AA, Pava J, Rosenbaum JF. Anxiety disorders in major depression. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2000;41(2):97–102. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(00)90140-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett J, Clark DC, Scheftner WA, Gibbons RD. Assessing anhedonia in psychiatric patients: The Pleasure Scale. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1983;40(1):79–84. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790010081010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders - Non-patient editions. New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes EE, Hariri AR, Martin SL, Silk JS, Moyles DL, Fisher PM, … Dahl RE. Altered striatal activation predicting real-world positive affect in adolescent major depressive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166(1):64–73. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07081336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes EE, May JC, Siegle GJ, Ladouceur CD, Ryan ND, Carter CS, … Dahl RE. Reward-related decision-making in pediatric major depressive disorder: An fMRI study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47(10):1031–1040. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01673.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes EE, Shaw DS, Dahl RE. Alterations in reward-related decision making in boys with recent and future depression. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;61(5):633–639. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foti D, Hajcak G. Depression and reduced sensitivity to non-rewards versus rewards: Evidence from event-related potentials. Biological Psychology. 2009;81(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foti D, Weinberg A, Dien J, Hajcak G. Event-related potential activity in the basal ganglia differentiates rewards from nonrewards: Temporospatial principal components analysis and source localization of the feedback negativity. Human Brain Mapping. 2011;32(12):2207–2216. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehring WJ, Willoughby AR. The medial frontal cortex and the rapid processing of monetary gains and losses. Science. 2002;295(5563):2279–2282. doi: 10.1126/science.1066893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Rouse MH, Connell AM, Broth MR, Hall CH, Hayward D. Maternal depression and child psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2011;14:1–27. doi: 10.1007/s10567-010-0080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Hamilton JP, Cooney RE, Singh MK, Henry ML, Joormann J. Neural processing of reward and loss in girls at risk for major depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67(4):380–387. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratton G, Coles MG, Donchin E. A new method for off-line removal of ocular artifact. Electroencephalography & Clinical Neurophysiology. 1983;55(4):468–484. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(83)90135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyer AE, Choate VR, Detloff A, Benson B, Nelson EE, Perez-Edgar K, … Ernst M. Striatal functional alteration during incentive anticipation in pediatric anxiety disorders. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;169(2):205. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11010006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajcak G, Moser JS, Holroyd CB, Simons RF. The feedback-related negativity reflects the binary evaluation of good versus bad outcomes. Biological Psychology. 2006;71(2):148–154. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Children of depressed parents. In: Gotlib IH, Hammen CL, editors. Handbook of depression. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2009. pp. 275–297. [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Brennan PA. Severity, chronicity, and timing of maternal depression and risk for adolescent offspring diagnoses in a community sample. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60(3):253–258. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.3.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriques JB, Davidson RJ. Decreased responsiveness to reward in depression. Cognition and Emotion. 2000;14(5):711–724. doi: 10.1080/02699930050117684. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema JM. What is the genetic influence between anxiety and depression? American Journal of Medical Genetics. 2008;148C:140–146. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde JS, Mezulis AH, Abramson LY. The ABCs of depression: Integrating affective, biological, and cognitive models to explain the emergence of the gender difference in depression. Psychological Review. 2008;115(2):291–313. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.115.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram RE, Luxton DD. Vulnerability-Stress Models. In: Hankin BL, Abela JRZ, editors. Development of psychopathology: A vulnerability-stress perspective. Thousand Oaks, CA US: Sage Publications, Inc; 2005. pp. 32–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ionescu DF, Niciu MJ, Mathews DC, Richards EM, Zarate CA. Neurobiology of anxious depression: A review. Depression and Anxiety. 2013 doi: 10.1002/da.22095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasch KL, Rottenberg J, Arnow BA, Gotlib IH. Behavioral activation and inhibition systems and the severity and course of depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111(4):589–597. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.111.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller MB, Beardslee WR, Dorer DJ, Lavori PW. Impact of severity and chronicity of parental affective illness on adaptive functioning and psychopathology in children. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1986;43(10):930–937. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800100020004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Merikangas KR. Mood disorders in children and adolescents: An epidemiologic perspective. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;49(12):1002–1014. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DN, Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR, Olino TM. Psychopathology in the adolescent and young adult offspring of a community sample of mothers and fathers with major depression. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35(3):353–365. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Children's Depression Inventory. Toronto, ON: Multi-Health Systems, Inc; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kujawa A, Dougherty L, Durbin CE, Laptook R, Torpey D, Klein DN. Emotion recognition in preschool children: Associations with maternal depression and early parenting. Development and Psychopathology. doi: 10.1017/S0954579413000928. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujawa A, Hajcak G, Torpey D, Kim J, Klein DN. Electrocortical reactivity to emotional faces in young children and associations with maternal and paternal depression. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2012;53(2):207–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02461.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C-sR, Huang CY, Lin W-y, Sun CWV. Gender differences in punishment and reward sensitivity in a sample of Taiwanese college students. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;43(3):475–483. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2006.12.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe C, Woffindale C, Harmer CJ, Cowen PJ. Neural processing of reward and punishment in young people at increased familial risk of depression. Biological Psychiatry. 2012;72(7):588–594. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naranjo CA, Tremblay LK, Busto UE. The role of the brain reward system in depression. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 2001;25(4):781–823. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(01)00156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson BD, McGowan SK, Sarapas C, Robison-Andrew EJ, Altman SE, Campbell ML, … Shankman SA. Biomarkers of threat and reward sensitivity demonstrate unique associations with risk for psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122(3):662. doi: 10.1037/a0033982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Gender differences in depression. In: Gotlib IH, Hammen CL, editors. Handbook of depression. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 2002. pp. 492–509. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Girgus JS. The emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;115(3):424–443. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.115.3.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oei TI, Verhoeven WM, Westenberg HG, Zwart FM, Van Ree JM. Anhedonia, suicide ideation and dexamethasone nonsuppression in depressed patients. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1990;24(1):25–35. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(90)90022-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olino TM, Klein DN, Dyson MW, Rose SA, Durbin CE. Temperamental emotionality in preschool-aged children and depressive disorders in parents: Associations in a large community sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119:468–478. doi: 10.1037/a0020112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker G, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Boyce P, Wilhelm K, Brodaty H, Mitchell P, … Eyers K. Classifying depression by mental state signs. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1990;157:55–65. doi: 10.1192/bjp.157.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick CJ, Venables NC, Yancey JR, Hicks BM, Nelson LD, Kramer MD. A construct-network approach to bridging diagnostic and physiological domains: Application to assessment of externalizing psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122(3):902. doi: 10.1037/a0032807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelizza L, Ferrari A. Anhedonia in schizophrenia and major depression: State or trait? Annals of General Psychiatry. 2009;8 doi: 10.1186/1744-859x-8-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Edgar K, Hardee J, Guyer AE, Benson B, Nelson E, Gorodetsky E, … Ernst M. DRD4 and striatal modulation of the link between childhood behavioral inhibition and adolescent anxiety. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2013 doi: 10.1093/scan/nst001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzagalli DA, Holmes AJ, Dillon DG, Goetz EL, Birk JL, Bogdan R, … Fava M. Reduced caudate and nucleus accumbens response to rewards in unmedicated individuals with major depressive disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166(6):702–710. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08081201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzagalli DA, Jahn AL, O'Shea JP. Toward an objective characterization of an anhedonic phenotype: A signal-detection approach. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;57(4):319–327. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawal A, Collishaw S, Thapar A, Rice F. ‘The risks of playing it safe’: A prospective longitudinal study of response to reward in the adolescent offspring of depressed parents. Psychological Medicine. 2012;1(1):1–12. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712001158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. Comparability of telephone and face-to-face interviews in assessing axis I and II disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154(11):1593–1598. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.11.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo SJ, Nestler EJ. The brain reward circuitry in mood disorders. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nrn3381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson WC, Beck AT, Beck J. Syndrome comorbidity in patients with major depression or dysthymia: Prevalence and temporal relationships. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1990;147(8):1025–1028. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.8.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santesso DL, Dzyundzyak A, Segalowitz SJ. Age, sex and individual differences in punishment sensitivity: Factors influencing the feedback-related negativity. Psychophysiology. 2011;48(11):1481–1488. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2011.01229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreier A, Höfler M, Wittchen HU, Lieb R. Clinical characteristics of major depressive disorder run in families–a community study of 933 mothers and their children. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2006;40(4):283–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankman SA, Nelson BD, Sarapas C, Robison-Andrew EJ, Campbell ML, Altman SE, … Gorka SM. A psychophysiological investigation of threat and reward sensitivity in individuals with panic disorder and/or major depressive disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122(2):322–338. doi: 10.1037/a0030747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smoski MJ, Felder J, Bizzell J, Green SR, Ernst M, Lynch TR, Dichter GS. fMRI of alterations in reward selection, anticipation, and feedback in major depressive disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009;118(1–3):69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobin C, Weissman MM, Goldstein RB, Adams P. Diagnostic interviewing for family studies: Comparing telephone and face-to-face methods for the diagnosis of lifetime psychiatric disorders. Psychiatric Genetics. 1993;3(4):227–233. doi: 10.1097/00041444-199324000-00005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steele JD, Kumar P, Ebmeier KP. Blunted response to feedback information in depressive illness. Brain: A Journal of Neurology. 2007;130(9):2367–2374. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrubia R, Avila C, Moltó J, Caseras X. The Sensitivity to Punishment and Sensitivity to Reward Questionnaire (SPSRQ) as a measure of Gray's anxiety and impulsivity dimensions. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;31(6):837–862. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00183-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Leijenhorst L, Zanolie K, Van Meel CS, Westenberg PM, Rombouts SA, Crone EA. What motivates the adolescent? Brain regions mediating reward sensitivity across adolescence. Cerebral Cortex. 2010;20(1):61–69. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner V, Mufson L, Weissman MM. Offspring at high and low risk for depression and anxiety: Mechanisms of psychiatric disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34(6):786–797. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199506000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Naragon-Gainey K. On the specificity of positive emotional dysfunction in psychopathology: Evidence from the mood and anxiety disorders and schizophrenia/schizotypy. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(7):839–848. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg A, Luhmann CC, Bress JN, Hajcak G. Better late than never? The effect of feedback delay on ERP indices of reward processing. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2012;12(4):671–677. doi: 10.3758/s13415-012-0104-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Leckman JF, Merikangas KR, Gammon GD, Prusoff BA. Depression and anxiety disorders in parents and children: Results from the Yale family study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1984;41(9):845. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790200027004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman M, Wickramaratne P, Nomura Y, Warner V, Pilowsky D, Verdeli H. Offspring of depressed parents: 20 years later. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(6):1001–1008. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.6.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]