Abstract

Background and study aims: Endoscopic vacuum treatment (EVT) is increasingly used in the treatment of anastomotic leakages and perforations in the upper gastrointestinal tract. However, sponges often have to be mounted individually on a gastric tube and endoscopic introduction of the latter into an infected extraluminal cavity is challenging. In order to facilitate this procedure in some anatomical situations, we developed the prototype of a new sponge for EVT called a two-side sponge (TSS).

Introduction

Endoscopic vacuum treatment (EVT) is increasingly used in the clinical management of anastomotic leakages and perforations in the upper gastrointestinal tract 1 2 3.

However, unlike EVT for rectal indications, a setting in which the Endo Sponge (Endo-SPONGE®; B-Braun Melsungen AG, Melsungen, Germany) is very well established, no commercial equipment was available for EVT in the upper gastrointestinal tract until a short time ago. The EVT sponge had to be mounted individually on a gastric tube and introducing it into an anastomotic leakage or perforation cavity was challenging. Recently, a new system called Eso-SPONGE® was launched by Braun Melsungen, for upper gastrointestinal tract EVT. The usability of this device has still to be proven. The technique, however, is comparable to that with the Endo-SPONGE® and the main difference is that the over-tube is twice as long (56 cm).

We recently reported a novel pull-through technique for EVT of an insufficient pancreaticogastrostomy 4. A precondition for this procedure is an endoscopically attainable abdominal drainage in the extraluminal cavity which was placed close to the anastomosis during the operation. A gastric tube is connected to the external end of the abdominal drain and the internal end of the tube is grasped endoscopically in the extraluminal cavity and drawn out orally. An Eso-SPONGE® is minimized in size, connected to the oral end of the gastric tube, and drawn into the cavity under endoscopic view by pulling the gastric tube on its outer abdominal end. Extraction of the sponge is performed by pulling with forceps on a previously attached thread 4.

In order to facilitate the procedure and to avoid self-mounted EVT, we developed a prototype two-sided sponge (TSS), which is suitable for EVT especially in the upper gastrointestinal tract (stomach and duodenum) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

TSS (two-sided sponge): An 8 × 2-cm open-pored polyurethane sponge is fixed in the center of a 160-cm plastic tube. The connection between the plastic tube and the polyurethane sponge is sutured and glued. Prototype (Braun Melsungen).

Patients and methods

Design of the Two-Sided Sponge (TSS)

An 8 × 2 cm open-pored polyurethane sponge is affixed to the center of a 160 cm-long plastic tube by means of sutures with additional gluing for maximum strength. The prototype of the TSS was produced by Braun Melsungen.

Two-Side Sponge (TSS) Treatment

The TSS introduction into the cavity is comparable to the procedure described above 4. Under endoscopic control, the sponge can be easily introduced into the cavity by pulling on the outer abdominal end of the TSS tube. If necessary, sponge positioning can be corrected by pulling on the proximal or distal TSS tube end. Pendular movement of the TSS can be achieved by pulling on its respective tube end (Fig. 2). The proximal sponge tube is then diverted through the nose. Sponge changes thus become very easy and fast. First the oral tube end is diverted from the nose to the mouth. Pulling on the oral tube end the TSS can be easily extracted. Because the distal sponge tube is long enough, it can be pulled out orally as well and can then be used as a pull-through tube for the next TSS. The vacuum can be applied alternatively at the proximal or distal or both tube ends. The advantages of the new TSS are listed in Table 1.

Fig. 2.

Illustration of a posterior-anterior view of a two-sided sponge (TSS) placed in an insufficient pancreaticogastrostomy. Introduction of the sponge into the extraluminal cavity is performed by pulling on the abdominal TTS tube end. Precise sponge adjustment is easy because a pendular movement can be exerted on the sponge by pulling on the oral or abdominal tube end respectively.

Table 1. Advantages and disadvantages of the two-sided sponge (TSS).

| Advantages |

|

|

|

|

|

| Limits |

|

|

Case Reports

Patient 1

We treated a 50-year-old woman with a post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) perforation of the duodenum. ERCP was carried out to evaluate a choledochus cyst. Two days later, the patient developed an acute abdomen with high inflammatory signs and signs of acute pancreatitis in laboratory findings. Computed tomography showed significant thickening of the duodenal wall, but no signs of pancreatitis. To exclude duodenal perforation, laparotomy was carried out on day 3. No duodenal perforation was detected but there were signs of necrotizing pancreatitis. A pancreatic necrosectomy was performed and an abdominal drain was placed. Because of ongoing intestinal secretion from the abdominal drain, the patient underwent re-laparotomy 6 days later. Duodenal perforation then was seen close to the papilla Vater, which was closed by single stitches, with additional cholecystectomy and placement of a T-drainage. The resumption of intestinal secretion from the abdominal drain was the indication for TSS, which was performed 2 days later. Operative treatment would have necessitated Whipple’s resection, which was impossible due to the severe septic constellation with generalized peritonitis. Endoscopy showed suture breakdown and a duodenal perforation of more than half the circumference, including the papilla of Vater (Fig. 3). In the cavity, there was an accessible abdominal drain (Fig. 4). Using the technique previously described, introduction of the TSS was easy (Fig. 5). Five TTS changes were performed at 5-day intervals. In all cases the described technique could be applied and no intervention took longer than 10 minutes to 15 minutes. A negative pressure of 100 mmHg was applied. This led to significant cleaning of the infected cavity with clinical improvement and distinct regression of the sepsis and peritonitis (Fig. 6). Finally, a pancreas-preserving duodenectomy could be performed, 6 weeks after the perforation.

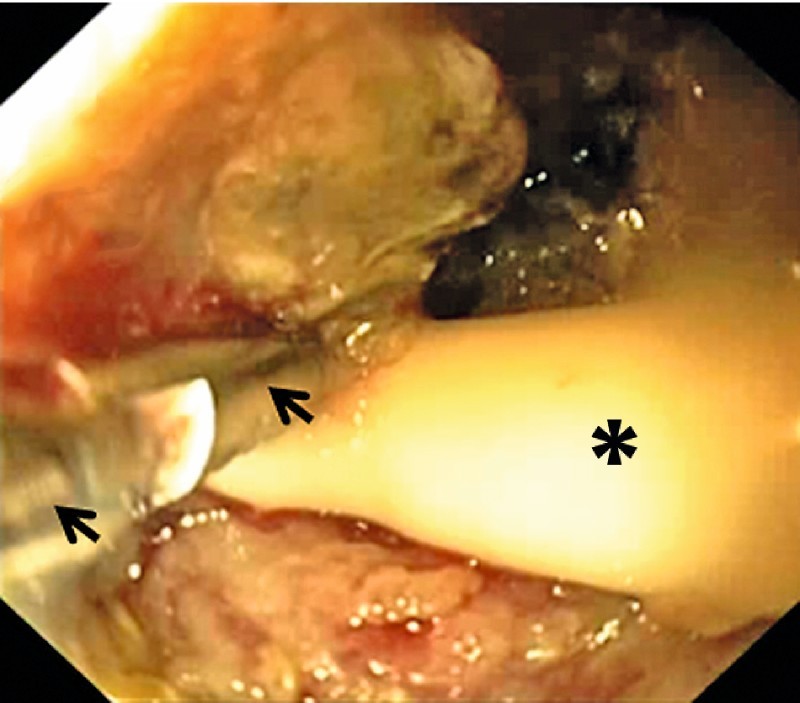

Fig. 3.

Gastroduodenoscopy showing the duodenal perforation (arrows). Duodenal lumen (asterisk).

Fig. 4.

Endoscopic view into the cavity. An abdominal drain (asterisk) is grasped with endoscopic forceps (arrows).

Fig. 5.

The two-sided sponge (TSS) is almost completely drawn into the cavity. Only a small part still extends into the duodenal lumen.

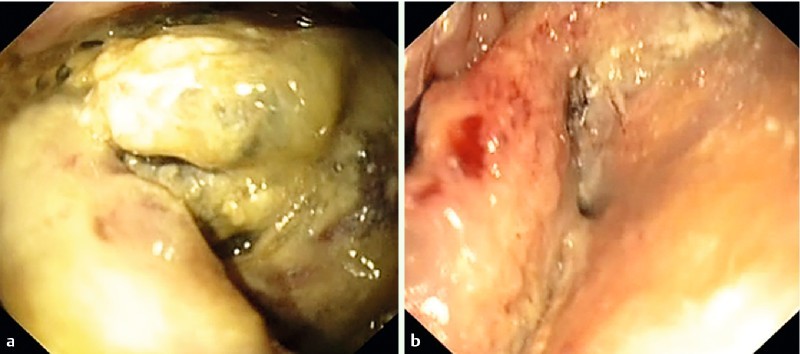

Fig. 6.

View into the cavity. a infected necrotic tissue. b Significant cleaning of the infected cavity after treatment with the two-sided sponge (TSS).

Patient 2

A 66-year-old patient underwent pylorus-preserving pancreatic head resection due to pancreatic carcinoma (pT3, pN0, pL0, pV0). On Day 6, gastric liquid was observed in the drains and a relatively small pancreaticogastrostomy insufficiency with an infected cavity was seen on gastroscopy. Abdominal drainage was visible in the endoscopically “hard-to-introduce” cavity (Fig. 7). TTS treatment was initiated ( Fig.8). The vacuum pump was used to apply negative pressure of 50 mmHg and the sponge was changed twice (at 5-day intervals). Ten days after initial sponge placement, a clean cavity with sponge-induced granulation tissue was observed and the TSS was replaced by a rubber tube, which was drawn back stepwise over 6 days as described earlier 4. Sixteen days after beginning TSS treatment, the anastomotic leak and cavity were completely healed.

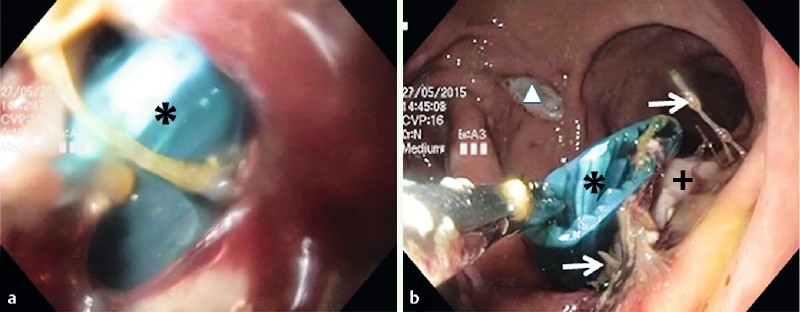

Fig. 7.

Insufficient pancreaticogastrostomy. a view into the infected cavity with visible abdominal drainage (asterisk). b The abdominal drainage was grasped endoscopically in the cavity and is about to be drawn out orally through the upper gastrointestinal tract. Anastomotic threads (arrows), pancreas (cross), anterior gastrotomy (triangle).

Fig. 8.

Two-sided sponge treatment. The two-sided sponge (TSS) has been introduced almost totally into the insufficient pancreaticogastrostomy. Only a small part still extends into the gastric lumen. Sponge (asterisk), pancreaticogastrostomy with pancreas protruding into the gastric lumen (cross).

Discussion

The great majority of case reports describe EVT of anastomotic leakages after esophagectomy or gastrectomy in an area 40 cm to 45 cm from the incisors 1 3 5 6 7 8. Until recently, a commercial set was only available for treatment of rectal leakages (Endo-SPONGE®) with an over-tube length of 28 cm. For EVT in the upper gastrointestinal tract, sponges had to be mounted individually on a gastric tube 2 3 8. Alternatively an Endo-SPONGE® could be trimmed to an appropriate size. Because of its short length, the Endo-SPONGE® tube had to be extended with a gastric tube.

Self-mounted endosponges must be relatively small in order to allow for introduction into the cavity with an endoscope. Generally the so-called “back pack” technique is used 2 3. The sponge is grasped by a thread fixed previously at its tip and then pulled parallel to the endoscope into the cavity, a technique that can be very demanding, especially in case of small and “hard-to-introduce” cavity entrances. With the TSS, sizes comparable to that of the Endo-SPONGE® can be introduced into the cavity, space permitting. Pulling on the abdominal external TSS tube, more force can be exerted on the sponge than in the endoscopic “back pack” technique. Another advantage compared to self-mounted sponges is the reduced potential risk of sponge separation pulling at the gastric tube during changes or removals. With a larger sponge, more extraction force is needed because of the increased tissue ingrowth into the sponge pores. If a sponge with abundant tissue ingrowth gets separated from the gastric tube, extraction by endoscopic means alone may be very problematic. Using endoscopic forceps, the sponge may break into small pieces and operative removal may become necessary.

Whether the recently launched Eso-SPONGE® is appropriate to replace self-mounted sponges has yet to be determined. In cases of small or sharp-angulated entrances into the cavity, introduction of the relatively stiff over-tube might be difficult. Furthermore, the Eso-SPONGE® device might be too short for EVT below the diaphragm.

In addition to the procedure described here, the TSS can also be used for the conventional endoscopic “back pack” technique. In this case, one has only to cut off one side of the TTS tube at the level of the sponge. The sponge can then be trimmed in length and diameter to meet the anatomical requirements.

Few reports exist of application of EVT in the abdominal upper gastrointestinal tract (e. g. antrum, duodenum) 4 9 10 11 12 13. Generally, placement of a sponge becomes more difficult, the deeper the cavity is located in the gastrointestinal tract. The maneuverability and exertable pressure of the endoscope tip decreases with increasing depth of introduction. Introduction of the sponge into the cavity with an endoscope or an over-tube (Eso-SPONGE®) is challenging, especially in case of sharp angles. If anatomical conditions permit, use of the TSS seems to be a good alternative to other procedures.

Conclusions

The TSS has proven its worth in these 2 clinical cases of EVT. Certainly, more experience with TSS treatment has to be gained in order to evaluate its suitability for routine use. TSS treatment is an alternative to other EVT procedures only if abdominal drainage is attainable in the cavity.

TSS treatment may lends itself to a new treatment strategy in the future. In cases of a difficult anastomosis in the upper abdominal GI-tract, the surgeon could place drainages as straight and close as possible to that anastomosis. That would increase the chance of successful TSS treatment in case of later suture breakdown. With TSS, flexible endoscopy may become an inherent part of the strategy and management of postoperative gastrointestinal complications.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None

References

- 1.Mennigen R, Harting C, Lindner K. et al. Comparison of Endoscopic Vacuum Therapy Versus Stent for Anastomotic Leak After Esophagectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:1229–1235. doi: 10.1007/s11605-015-2847-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mennigen R, Senninger N, Laukoetter M G. Novel treatment options for perforations of the upper gastrointestinal tract: endoscopic vacuum therapy and over-the-scope clips. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:7767–7776. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i24.7767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schorsch T, Müller C, Loske G. Endoscopic vacuum therapy of anastomotic leakage and iatrogenic perforation in the esophagus. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:2040–2045. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2707-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fischer A, Richter-Schrag H J, Hoeppner J. et al. Endoscopic intracavitary pull-through vacuum treatment of an insufficient pancreaticogastrostomy. Endoscopy. 2014;46:E218–E219. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1364951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schniewind B, Schafmayer C, Voehrs G. et al. Endoscopic endoluminal vacuum therapy is superior to other regimens in managing anastomotic leakage after esophagectomy: a comparative retrospective study. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:3883–3890. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-2998-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brangewitz M, Voigtländer T, Helfritz F A. et al. Endoscopic closure of esophageal intrathoracic leaks: stent versus endoscopic vacuum-assisted closure, a retrospective analysis. Endoscopy. 2013;45:433–438. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1326435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bludau M, Hölscher A H, Herbold T. et al. Management of upper intestinal leaks using an endoscopic vacuum-assisted closure system (E-VAC) Surg Endosc. 2014;28:896–901. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3244-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loske G, Schorsch T, Müller C. Intraluminal and intracavitary vacuum therapy for esophageal leakage: a new endoscopic minimally invasive approach. Endoscopy. 2011;43:540–544. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loske G, Lang U, Schorsch T. et al. Complex vacuum therapy of an abdominal abscess from gastric perforation: Case report of innovative operative endoscopic management. Chirurg. 2015;86:486–490. doi: 10.1007/s00104-015-2993-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischer A, Baier P K, Hopt U T. et al. Laparoendoscopic mediastinal vacuum therapy of a gastric perforation through the diaphragm. Endoscopy. 2011;43:E393–E394. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schorsch T, Müller C, Loske G. Pancreatico-gastric anastomotic insufficiency successfully treated with endoscopic vacuum therapy. Endoscopy. 2013;45:E141–E142. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1326260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loske G, Strauss T, Riefel B. et al. Endoscopic vacuum therapy in the management of anastomotic insufficiency after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Endoscopy. 2012;44:E94–E95. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1291698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loske G, Schorsch T, Mueller C T. Endoscopic intraluminal vacuum therapy of duodenal perforation. Endoscopy. 2010;42:E109. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1243947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]