Abstract

The majority of melanoma patients harbor mutations in the BRAF oncogene, thus making it a clinically relevant target. However, response to mutant BRAF inhibitors (BRAFi) is relatively short-lived with progression free survival of only 6–7 months. Previously, we reported high expression of ribonucleotide reductase M2 (RRM2), which is rate limiting for de novo dNTP synthesis, as a poor prognostic factor in mutant BRAF melanoma patients. In this study, the notion that targeting de novo dNTP synthesis through knockdown of RRM2 could prolong the response of melanoma cells to BRAFi was investigated. Knockdown of RRM2 in combination with the mutant BRAFi PLX4720 (an analog of the FDA-approved drug vemurafenib) inhibited melanoma cell proliferation to a greater extent than either treatment alone. This occurred in vitro in multiple mutant BRAF cell lines and in a novel patient-derived xenograft (PDX) model system. Mechanistically, the combination increased DNA damage accumulation, which correlated with a global decrease in DNA damage repair (DDR) gene expression and increased apoptotic markers. After discontinuing PLX4720 treatment, cells showed marked recurrence. However, knockdown of RRM2 attenuated this rebound growth both in vitro and in vivo, which correlated with maintenance of the senescence-associated cell cycle arrest.

Keywords: melanoma, BRAF, nucleotide metabolism, apoptosis, senescence

Introduction

Melanoma is the leading cause of skin cancer deaths in the United States (1). The majority of patients (>50%) have a missense mutation in the activation loop of the serine-threonine kinase BRAF at codon 600 (2). Approximately 80–90% of mutations at this position are a substitution of the amino acid valine (V) to glutamic acid (E), BRAFV600E. This mutation leads to hyperactivation of BRAF and its downstream signaling pathways, which is thought to be the driver of these tumors (3). Thus, specific targeting of mutant BRAFV600E is clinically relevant. Since 2011, two BRAFV600E inhibitors (BRAFi) have been approved by the FDA for mutant BRAFV600E melanoma and are now standard-of-care (4). Although specific BRAFi improve survival compared to previous mainstay therapies, resistance is a common clinical outcome with most patients having progressive disease within 6–8 months (5, 6). Combined BRAF/MEK inhibition has increased progression free and overall survival compared to BRAFi alone (5, 7, 8). However, resistance is still a common outcome in these patients (9). Therefore, novel combinatorial strategies to prolong the response to BRAFi are urgently needed.

Ribonucleotide reductase M2 (RRM2) is a part of the ribonucleotide reductase (RNR) complex (10). RNR catalyzes the conversion of ribonucleoside 5′-diphosphates into 2′-deoxyribonucleoside 5′-triphosphates (dNTPs), building blocks required for both DNA replication and repair (10). RRM2 is rate-limiting for the conversion of NTPs into dNTPs during the S phase of the cell cycle (11). RRM2 is highly upregulated in melanoma cells harboring mutant BRAFV600E, and high RRM2 expression correlates with worse overall survival of melanoma patients (12). This suggests RRM2 plays a significant role in melanoma cell proliferation and tumor progression. Indeed, knockdown of RRM2 inhibits melanoma cell proliferation (12, 13). However, whether inhibition of RRM2 can prolong the treatment effect of BRAFi has not been explored.

In this study, we found that knockdown of RRM2 in combination with the BRAFi PLX4720 decreases cell proliferation both in vitro and in vivo better than either treatment alone. We determined that the combination of RRM2 knockdown and PLX4720 treatment induced melanoma cell apoptosis, which was likely due to an increase in DNA damage accumulation. Mechanistically, we identified a panel of DNA repair genes that are globally down-regulated in the combination of RRM2 knockdown and PLX4720 treatment, which may contribute to the increase DNA damage accumulation and subsequent melanoma cell apoptosis. After withdrawal from PLX4720, cells with RRM2 knockdown did not grow out in vitro, and tumors grew slower in vivo. These data suggest that inhibition of RRM2 could be a novel therapeutic strategy to prolong treatment response of melanoma patients to BRAFi.

Materials and Methods

Cells and culture conditions

Mutant BRAFV600E WM793 and ND238 human melanoma cell lines were obtained from Dr. Meenhard Herlyn’s lab at The Wistar Institute (https://www.wistar.org/lab/meenhard-herlyn-dvm-dsc/page/melanoma-cell-lines-0). WM793 cells were obtained 3 years ago and were re-authenticated by The Wistar Institute’s Genomics Facility at the end of experiments using Short tandem repeat (STR) profiling using AmpFlSTR® Identifiler® PCR Amplification Kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). ND238 cells were used within 6 months from receiving them, and the Herlyn lab group authenticated the cells using the same method described above. Cells were cultured in TU 2% media and as previously described (14).

Reagents, plasmids, and antibodies

The vemurafenib analog PLX4720 was provided by Plexxikon (Berkeley, CA). pLKO.1-shRRM2 plasmids were obtained from Open Biosystems (Waltham, MA). The following antibodies were obtained from the indicated suppliers: goat anti-RRM2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), mouse anti-cyclin A (Novocastra Laboratories, Buffalo Grove, IL), mouse anti-γH2AX (Millipore), rabbit anti-cleaved lamin A (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), rabbit anti-c-Myc (Cell Signaling), rabbit anti-PARP p85 (Promega Corporation, Fitchburg, WI), rabbit anti-phospho-ERK1/2 (Cell Signaling), mouse anti-GAPDH (Millipore), rabbit anti-pS10H3 (Millipore), and mouse anti-BrdU FITC (BD Biosciences).

Lentivirus infections

Control and shRRM2 lentivirus was packaged using the Virapower Kit from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions and as described previously (15–17). Targeting sequences for RRM2 small hairpins can be found in Supplemental Table 1. Cells stably infected with viruses encoding the puromycin-resistance gene were selected in 1 μg/ml puromycin. Lentivirus concentration for mouse experiments was performed using the Lenti-X Concentrator (Clonetech Laboratories, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Concentrated virus was dissolved in PBS.

Immunoblotting and qRT-PCR

Western immunoblotting was performed as described previously (12) using the antibodies indicated above. For analysis of mRNA expression, total RNA was extracted with Trizol (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. DNAse digestion and cleanup was performed using the RNeasy Kit (Qiagen). qRT-PCR was performed using the iScript One-Step RT-PCR with SYBR Green kit (BioRad, Hercules, California). Primers were as follows: XRCC6: Forward: 5′-GGGCTTTGACATATCCTTGTTC-3′ and Reverse: 5′-CTGGTTCATTGTTTCCCGATAG-3′; XRCC5: Forward: 5′-AGAAGAAGGCCAGCTTTGAG-3′ and Reverse: 5′-AGCTGTGACAGAACTTCCAG-3′; PRKDC: Forward: 5′-AGAAGGCGGCTTACCTGAGT-3′ and Reverse: 5′-GACATTTTTGTCAGCCAATCTTT-3′; RAD51: Forward: 5′-GCTGGGAACTGCAACTCATCT-3′ and Reverse: 5′-GCAGCGCTCCTCTCTCCAGC-3′.

BrdU labeling and SA-β-gal staining

BrdU labeling and SA-β-Gal staining was performed as previously described (12, 18). For SA-β-gal staining in sections from xenografted tumors, 10 separate fields were examined from 6 individual tumors for each of the groups. Quantification of SA-β-gal in tumor sections was determined using NIH ImageJ software by measuring the SA-β-gal positive area normalized by total image area.

Colony formation assay

For colony formation, an equal number of cells (1000 cells/well) was inoculated in 12-well plates and cultured for additional 2 weeks. Colony formation was visualized by staining the plates with 0.05% crystal violet as previously described (17). Integrated density was determined using NIH ImageJ software.

Cell cycle analysis

Cells were pelleted by centrifugation, washed with ice cold PBS, and fixed in ice-cold 70% ethanol. Cells were incubated in propidium iodide solution with sodium citrate and RNAse A. Cells were then analyzed for DNA content. FlowJo (FlowJo, LLC, Ashland, OR) was used for data analysis.

3D matrigel assay

Cells were cultured in growth factor reduce matrigel as described previously (19). Briefly, 40 μL of matrigel was plated on Falcon culture slides. After polymerization of matrigel, 4000 cells were seeded into each well of the slide and cultured in complete cell culture media + 3% matrigel. ImageJ was used to quantify acini size.

Mouse study

A short-term culture was established from a patient tumor and used to generate a cohort of xenografts. A single cell suspension of ND238 melanoma cells (1×106) was subcutaneously injected into the lower flanks of 6–8 week old, male NSG mice in a suspension of matrigel/complete media at a ratio of 1:1. PLX4720 200ppm chemical additive diet was irradiated and heat-sealed (Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ) and fed to mice once tumors were established (20). PLX4720 was provided by Plexxikon, Berkeley, CA. When tumors reached 200mm3 animals were randomly assigned into 4 different groups: (a) 50μL concentrated control virus; (b) 50μL concentrated shRRM2 virus; (c) 50μL concentrated control virus + PLX4720 (200 mg/kg); and (d) 50 μL concentrated shRRM2 virus + PLX4720 (200 mg/kg). Virus injections were performed at day 0, day 10 and weekly starting at week 6. Tumor size was assessed twice weekly by caliper measurement. Tumor volume was calculated using the formula WxWxL/2. All animal experiments were approved by The Wistar Institute’s IACUC.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was conducted by using antibodies listed above with a Dako EnVision System and the Peroxidase (DAB) kit following the manufacturer’s instructions and as previously described (27). Briefly, tissue sections were subjected to antigen retrieval by steaming in sodium citrate buffer. After quenching endogenous peroxidase activity and blocking nonspecific protein binding, sections were incubated overnight with a primary antibody at 4°C, followed by biotinylated secondary antibody, detecting the antibody complexes with the labeled streptavidin-biotin system, and visualizing them with the chromogen 3,30-diaminobenzidine. Sections were lightly counterstained with hematoxylin. Each section was scored in a blinded manner and given a combined score for the percentage of positive cells and intensity of staining (H score).

Statistical analysis

Graphpad Prism Version 5.0 was used to perform statistical analyses. Unless otherwise indicated, the student’s t test was used to determine p values of raw data. A p value <0.05 was considered significant. For tumor growth data from in vivo experiments, linear mixed-effect models were used to test the treatment effect on the tumor growth trend over time. A likelihood ratio testing nested model was used to examine if trends were overall significantly different among groups.

Results

Knockdown of RRM2 in combination with a mutant BRAF inhibitor inhibits melanoma cell proliferation

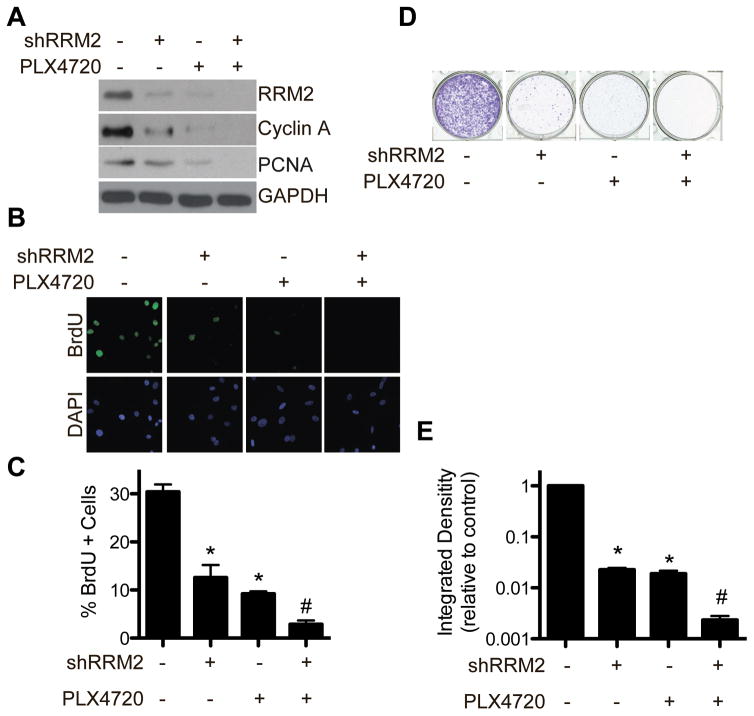

We previously published that RRM2 is significantly upregulated in BRAF mutated melanoma cell lines compared to normal melanocytes, and high RRM2 expression correlates with shorter overall survival in patients harboring oncogenic BRAF (12). Therefore, we wanted to observe the effects of RRM2 knockdown in combination with BRAFV600E inhibition in melanoma cell lines with BRAFV600E mutation. BRAFV600E mutated WM793 melanoma cells were treated with the BRAFi PLX4720 with or without knockdown of RRM2 (shRRM2) (Fig. S1A). Both knockdown of shRRM2 and treatment with PLX4720 downregulated RRM2 expression, which correlated to a decrease in the proliferation markers cyclin A (Fig. 1A) and BrdU incorporation (Fig. 1B–C). This correlated with a decrease in cell growth as determined by focus formation assays (Fig. 1D–E). The combination of shRRM2 and PLX4720 further decreased RRM2 expression, cell proliferation, and growth markers than either treatment alone (Fig. 1A–E). Similar results were observed using a second BRAFV600E mutated patient-derived melanoma cell line ND238, demonstrating this is not a cell line specific effect (Fig. S1C–D). Additionally, using a second independent hairpin to RRM2 or 3AP, a small molecule inhibitor of RRM2 (21), also showed similar effects (Fig. S1E–I). Taken together, these data indicate that inhibition of RRM2 and BRAFV600E in combination can inhibit melanoma cell growth to a greater extent than either treatment alone.

Figure 1. The combination of shRRM2 with PLX4720 inhibits cell proliferation to a greater extent than either treatment alone.

A, WM793 cells were stably infected with control or shRRM2 lentivirus and treated with DMSO or 1μM PLX4720. After 7 days in culture, RRM2, cyclin A, and PCNA protein expression was determined by western immunoblotting. GAPDH was used as a loading control. B, Same as (A) but cells were labeled with 10μM BrdU for 30 min. The incorporated BrdU was visualized by immunofluorescence. DAPI was used as a counterstain to visualize cell nuclei. C, Quantification of (B). Mean of 3 independent experiments with SEM. D, Same as (A) but an equal number of cells (1000 cells/well) were seeded in 12-well plates, and after 2 weeks in culture the plates were stained with 0.05% crystal violet in PBS to visualize focus formation. Shown are representative images of 3 independent experiments. E, The intensity of focus formed by the indicated cells was quantified using NIH image J software (n=3). Note the log scale. *p<0.05 compared with control. #p<0.05 compared with shRRM2 or PLX4720 alone.

Knockdown of RRM2 in combination with a BRAF inhibitor induces melanoma cell apoptosis, which correlates with DNA damage accumulation

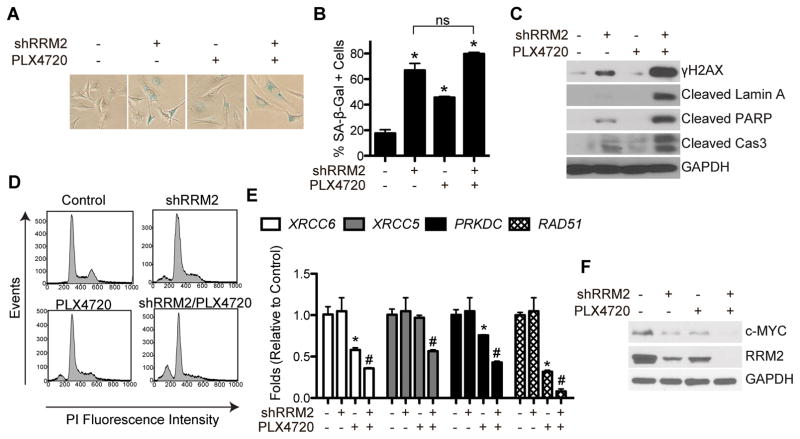

Knockdown of RRM2 inhibits cell proliferation through induction of senescence via increased DNA damage accumulation (12, 18). Additionally, it has been previously published that BRAFi induce melanoma cell senescence (22, 23). Consistently, both knockdown of RRM2 and PLX4720 alone induced senescence in WM793 melanoma cells, as determined by an increase in senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-Gal) activity (Fig. 2A–B). This correlated with an increase in γH2AX protein expression, a marker of DNA double strand breaks (Fig. 2C). Increased γH2AX protein expression was also observed using an independent shRRM2 and the small molecule inhibitor of RRM2 3AP (Fig. S1E, S2A). A marked increase in γH2AX protein expression was observed in cells treated with the combination of shRRM2 and PLX4720 (Fig. 2C). However, no further increase in SA-β-Gal activity was observed (Fig. 2A–B). These data suggest that an additional mechanism is critical for inhibiting melanoma cell proliferation in this context.

Figure 2. The combination of shRRM2 with PLX4720 induces DNA damage accumulation and melanoma cell apoptosis.

A, WM793 cells were stably infected with control or shRRM2 lentivirus and treated with DMSO or 1μM PLX4720. After 7 days in culture, cells were stained for SA-B-Gal activity. B, Quantification of (A). Mean of 3 independent experiments with SEM *p<0.01 compared with control. C, Same as (A) but γH2AX, cleaved lamin A, cleaved PARP, and cleaved caspase 3 (cas3) protein expression was determined by western immunoblotting. GAPDH was used as a loading control. D, Same as (A) but cell cycle analysis was performed after staining cells with propidium iodide. E, Same as (A) but on day 2 in culture, gene expression of the indicated mRNAs was determined by qRT-PCR. *p<0.05 compared with control. #p<0.01 compared with PLX4720 alone. F, Same as (E) but RRM2 and c-MYC protein expression was determined by immunoblotting. GAPDH was used as a loading control.

Since the combination of shRRM2 and PLX4720 inhibited cell proliferation but did not further increase senescence (Fig. 1B–E and Fig. 2A–B), we hypothesized that these cells were undergoing cell death. Indeed, western blot analysis showed an increase in a panel of apoptotic markers such as cleaved lamin A, cleaved PARP, and cleaved caspase 3 (Fig. 2C). Consistently, cells treated with shRRM2 and PLX4720 in combination had an increased percentage of sub G0/G1 cells, as determined by cell cycle analysis, suggesting an increase in apoptotic cell death (Fig. 2D, Table 1). A similar increase in apoptotic markers was observed using a second cell line, suggesting that this is not a cell line specific effect (Fig. S2B). These data indicate that the combination of RRM2 knockdown and BRAFi induces apoptotic cell death.

Table 1.

Cell cycle analysis of WM793 melanoma cells treated with shRRM2 and PLX4720 alone and in combination.

| Sub G0/G1 | G0/G1 | S | G2/M | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 1.85 | 58.7 | 11.8 | 18.8 |

| PLX4720 | 8.72 | 59.6 | 14.5 | 12.2 |

| shRRM2 | 9.51 | 63.9 | 14 | 10.7 |

| Combination | 23.3 | 54.6 | 10.3 | 7.78 |

We next wanted to determine the mechanism whereby mutant BRAF melanoma cells undergo apoptosis after the combination of RRM2 knockdown and treatment with PLX4720. Compared to shRRM2 or PLX4720 alone, the combination increased γH2AX protein expression, a marker of DNA double strand breaks (Fig. 2C). We hypothesized that the accumulation of DNA damage in the combination was due to an altered DNA damage repair response. Therefore, we profiled the expression of genes known to play a role in the repair of DNA double strand breaks in the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination (HR) pathways. Knockdown of RRM2 in combination of BRAF inhibition significantly decreased the expression of multiple genes critical for NHEJ, including XRCC6, XRCC5, and PRKDC, and the HR gene RAD51 (Fig. 2E). Similarly, genes involved in both NHEJ and HR such as MRE11, NBS1, and RAD50 were also significantly decreased in cells treated with the combination (Fig. S2C). These results suggest a global decrease in the transcription of a subset of DNA damage repair genes. Indeed, the combination of RRM2 knockdown and BRAFi led to a decrease in c-MYC expression, which is known to affect the transcription of these genes (Fig. 2F) (24). Taken together, these data suggest that RRM2 knockdown in combination with BRAFi leads to apoptosis at least in part through decreased DNA repair gene expression and increased DNA damage accumulation.

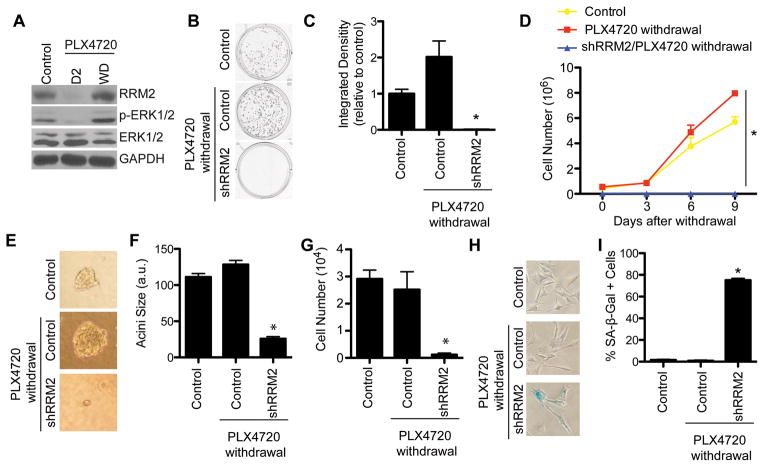

Knockdown of RRM2 maintains melanoma cell growth arrest after mutant BRAF inhibitor withdrawal

Clinical evidence suggests that resistance to BRAFi is common (5, 6), and tumors rapidly grow after patients discontinue therapy (25). Indeed, we found that while treatment of mutant BRAFV600E WM793 cells with the BRAFi PLX4720 markedly decreased RRM2 expression at an early time point, RRM2 is re-expressed after treatment and drug withdrawal (Fig. 3A). The increase in RRM2 correlated with an increase in p-ERK1/2, a marker of activated BRAF pathway signaling (Fig. 3A). Therefore, we wanted to determine whether knockdown of RRM2 could maintain the growth inhibition after cells were withdrawn from PLX4720. Control and RRM2 knockdown WM793 cells were treated with PLX4720 for one week, after which they were PLX4720 was withdrawn (Fig. S1A). Control cells withdrawn from PLX4720 exhibit a significant increase in cell proliferation both in 2D and 3D matrigel assays, which more closely mimics the in vivo microenvironment (Fig. 3B–G). However, compared with PLX4720 alone, shRRM2 cells withdrawn from PLX4720 showed a significant decrease in cell proliferation (Fig. 3B–G). This correlated with maintenance of RRM2 knockdown by the short hairpin (Fig. S3A). Similar results were observed in a second cell line and using an independent shRRM2 and the RRM2 inhibitor 3AP (Fig. S3A–K). Finally, we wanted to identify the mechanism whereby melanoma cells expressing shRRM2 and withdrawn from PLX4720 do not highly proliferate. We found that in comparison to controls, these cells remain senescent, as determined by SA-β-Gal staining (Fig. 3H–I). These data indicate that knockdown of RRM2 sustains melanoma cell growth arrest even after cells are withdrawn from PLX4720 by maintaining the senescent phenotype.

Figure 3. Knockdown of RRM2 prolongs PLX4720 treatment response after drug withdrawal.

A, WM793 cells were treated with 1μM PLX4720 for 7 days and then withdrawn from drug treatment. RRM2, p-ERK1/2, and total ERK1/2 expression was determined on day 2 (D2) during PLX4720 treatment and day 7 after withdrawal (WD). B, WM793 cells were stably infected with shRRM2 lentivirus and treated with DMSO or 1uM PLX4720. After 7 days in culture, PLX4720 was withdrawn (See Fig. S1A). An equal number of cells (1000 cells/well) were seeded in 12-well plates, and after 2 weeks in culture the plates were stained with 0.05% crystal violet in PBS to visualize focus formation. C, Quantification of (B). Mean of 3 independent experiments with SEM. D, Same as (B) an equal number of cells were seeded in 6-well plates, and cell number was determined at the indicated time points. E, Same as (B) but an equal number of cells (4000 cells/well) were seeded in matrigel in 8-well chamber slides. Representative images after an additional 2 weeks in culture are shown. F–G, Quantification of (E). Acini size (F) and cell number (G) were determined. H, Same as (B) but cells were stained for SA-β-Gal activity. I, Quantification of (G). *p<0.05 compared with control and PLX4720 withdrawal cells.

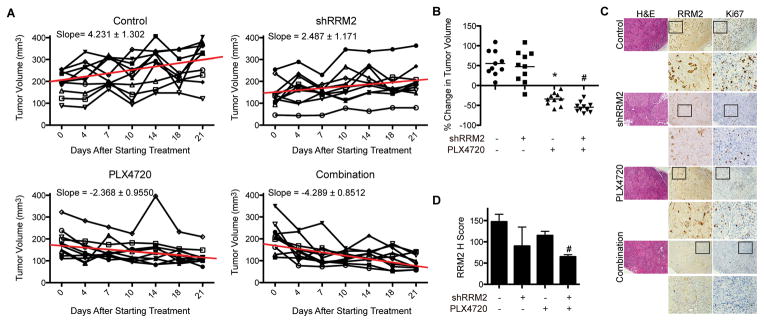

The combination of RRM2 knockdown and BRAF inhibitor inhibits melanoma patient-derived xenograft tumor growth

Since the combination of shRRM2 and PLX4720 inhibits mutant BRAF melanoma cell proliferation in vitro, we wanted to determine its effect in vivo in a xenograft mouse model. Immunocompromised NSG mice were injected with mutant BRAF ND238 melanoma cells derived from a patient. Once tumors reached 200mm3, mice were randomized and injected with either control or shRRM2 virus intratumorally (26) and fed control or PLX4720-containing chemical additive diet (200 mg/kg) (20) (Fig. S4A). RRM2 knockdown efficiency was validated by immunohistochemistry (IHC) 3 days after injection (Fig. S4B). Knockdown of RRM2 in combination with PLX4720 inhibited tumor cell growth to a greater extent than either treatment alone (Fig. 4A–B). IHC analysis at this time point showed a greater decrease in RRM2 in the combination tumors compared to either treatment alone (Fig. 4C–D). This correlated with expression of Ki67, a marker of cell proliferation (Fig. 4C, S4C). These data suggest that inhibition of RRM2 and BRAF in combination inhibits melanoma tumor growth better than either treatment alone.

Figure 4. Knockdown of RRM2 in combination with PLX4720 inhibits patient-derived melanoma tumor growth in vivo.

A, ND238 patient-derived melanoma cells were subcutaneously injected into immunocompromised NSG mice. Once tumors reached 200mm3 volume, mice were randomized into the 4 indicated groups (See Fig. S4A). Graphs show tumor growth of each individual mouse in the indicated groups. Slope based on mean tumor volume of each group is indicated along with a trend line for averages from the entire group. B, Same as (A) but graphs indicate % change in tumor volume 21 days later. *p<0.05 vs. control; #p<0.05 vs. PLX4720 alone (calculated using Mann–Whitney test). C, Immunohistochemical staining of RRM2 and Ki67 in tumors from (B). D, Quantification of RRM2 staining in (C). Expression of RRM2 in the indicated groups was quantified using the histological score. *p<0.05 vs. control; #p<0.05 vs. PLX4720 alone.

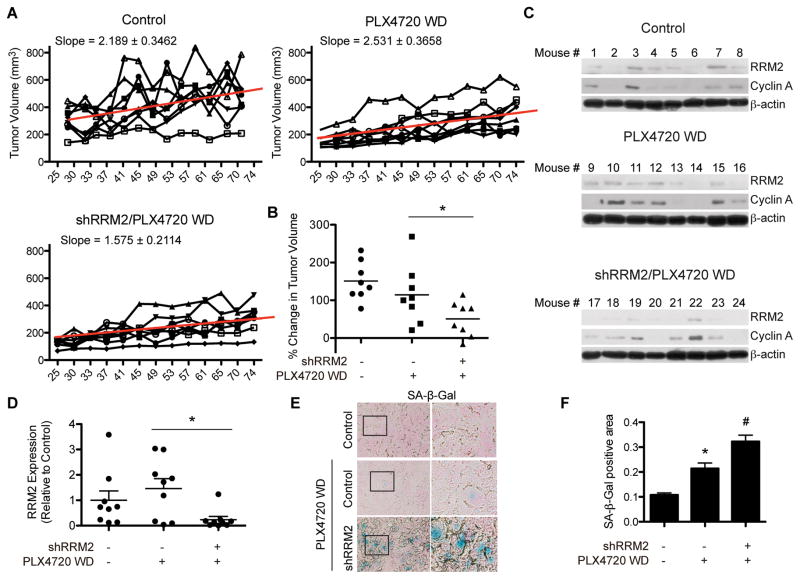

Knockdown of RRM2 prolongs the effects of the mutant BRAF inhibitor after discontinuation of the drug

We next aimed to determine the effect of RRM2 knockdown on tumor growth after discontinuation of PLX4720 treatment. After 21 days of PLX4720 treatment, mice were taken off the drug and fed a normal diet for the remainder of the study (Fig. S4A). Similar to what was observed in vitro, tumors initially treated with PLX4720 showed a marked rebound in growth after withdrawal of the drug (Fig. 5A–B, S4D). However, tumors with RRM2 knockdown withdrawn from PLX4720 displayed a decrease in this rebound phenotype (Fig. 5A–B, S4D). Slowed tumor growth correlated with an overall lower expression of RRM2 and cyclin A in the combination group, although some heterogeneity was observed (Fig. 5C–D, S4E). Similar to what was observed in vitro, the tumors with knockdown of RRM2 withdrawn from PLX4720 displayed higher SA-β-Gal activity, suggesting the slower tumor growth rate is in part due to senescence of these tumors (Fig. 5E–F). These results indicate the knockdown of RRM2 prolongs the response to mutant BRAF inhibitors after drug withdrawal in a xenograft melanoma model.

Figure 5. Knockdown of RRM2 attenuates patient derived tumor growth after withdrawal from PLX4720 in vivo.

A, ND238 patient derived tumors were discontinued from PLX4720 treatment after 21 days. Graphs show tumor growth of each individual mouse in the indicated groups. Slope based on mean tumor volume of each group is indicated along with a trend line for averages from the entire group. WD = withdrawal. B, Shown is % change in tumor volume on Day 74. *p=0.0061 PLX4720 WD vs. shRRM2/PLX4720 WD (calculated using linear mixed-effect models). C, RRM2 and cyclin A protein expression was assessed in individual tumors from (B) on day 89. β-actin was used as a loading control. D, Quantification of RRM2 expression in (C). *p<0.05 PLX4720 WD vs. shRRM2/PLX4720 WD. E, SA-β-Gal expression in tumors from (B). F, Quantification of (E) using ImageJ. *p<0.05 vs. control; #p<0.05 vs. PLX4720 WD.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that knockdown of RRM2 inhibited cell proliferation in combination with the mutant BRAFi PLX4720 to a greater extent than either treatment alone. Mechanistically, this was due to an increase in apoptosis likely mediated by decreased DNA damage repair and a subsequent increase in DNA damage accumulation. Additionally, we determined that knockdown of RRM2 extended the response to PLX4720 after treatment withdrawal. Taken together, these data indicate that inhibiting RRM2 represents a novel strategy to prolong melanoma response to BRAFi.

We found that knockdown of RRM2 inhibited melanoma cell proliferation (Fig. 1). This is consistent with previous studies showing that RRM2 inhibition can reduce melanoma cell proliferation regardless of BRAF mutation status (12, 13). Melanoma cell proliferation was further decreased when combined with the BRAFi PLX4720 (Fig. 1). PLX4720 itself decreased RRM2 expression (Fig. 1A), further underscoring the notion that RRM2 expression correlates with melanoma cell growth. Additionally, when cells were withdrawn from PLX4720 treatment and began to grow, RRM2 expression returned to parental cell levels (Fig. 3A). This is consistent with our previous study that demonstrated a correlation between RRM2 expression and the proliferative status of benign nevi or melanomas harboring oncogenic BRAF mutations (12). These data suggest RRM2 plays a role in response to mutant BRAF inhibition, and further support the idea of targeting RRM2 in combination with mutant BRAFi.

The combination of RRM2 knockdown and PLX4720 treatment significantly decreased melanoma cell proliferation compared to either treatment alone both in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 1 & 4). Some amount of heterogeneity in the RRM2 knockdown alone tumors was observed in vivo, which was likely due to outgrowth melanoma cells where RRM2 knockdown efficiency was low. Nevertheless, the combination of RRM2 knockdown and BRAFi decreased tumor volume to a greater extent than BRAFi alone (Fig. 4A–B). Consistent with our results, previous studies have shown that RRM2 knockdown induces DNA double strand breaks (12, 18, 27). We observed a further increase in γH2AX, a marker of DNA double strand breaks, in the combination of shRRM2 and PLX4720 compared to either treatment alone (Fig. 2C). DNA damage due to RRM2 inhibition is linked to induction of cellular senescence, a state of cell growth arrest (12, 18, 27, 28). Additionally, cells treated with BRAF inhibitors display some markers of senescence (22, 23). However, no synergistic increase in senescence was observed (Fig. 2A–B), suggesting another mechanism is important for the reduction in cell proliferation. Increased DNA damage in combination of RRM2 knockdown and BRAFi may be a result of decreased DNA damage repair, which can lead to apoptosis. Consistently, RRM2 relocalization to sites of DNA double strand breaks provides dNTPs for DNA repair different pathways (53). Additionally, expression of DNA damage repair genes has been shown to be a poor biomarker for melanoma (29, 30). We observed a global downregulation in genes known to play a role in HR and NHEJ, the two major DNA double strand break repair pathways (Fig. 2E) (31). Consistently, inhibition of the MEK pathway, which is downstream of BRAF, results in inactivation of multiple DNA repair pathways (32). c-MYC, a global transcriptional regulator of DNA damage repair genes (24), was downregulated in the combination of shRRM2 and PLX4720 (Fig. 2F), suggesting c-MYC may regulate expression of these genes in this context. It is possible that other mechanisms, in addition to c-MYC, are contributing to suppress transcription of DNA damage repair genes. Regulation of DNA repair pathways is complex. For instance, transcriptional regulators such as p53 and NF-κB (33, 34) and posttranscriptional modifiers such as HDACs and ATM (35, 36) may also play a role in transcriptional regulation of these genes. Nonetheless, our data suggest that the apoptosis observed in the melanoma cells treated with a combination of shRRM2 and PLX4720 is at least partially due to a decrease in DNA repair gene expression that may be regulated by c-MYC.

Resistance to BRAF inhibitors is a significant clinical hurdle, with over half of patients having progressive disease within 6–8 months (5, 6). Additionally, some studies report a rebound growth of tumors after withdrawal of BRAF inhibitor treatment (25). Herein, we found that RRM2 expression returns to control levels after withdrawal from PLX4720, which correlated with p-ERK1/2 levels, suggesting re-activation of the BRAF signaling pathway. Indeed, knockdown of RRM2 slowed the rebound growth observed after PLX4720 withdrawal both in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 3 & 5). The outgrowth of the combination tumors may be due to heterogeneity either in RRM2 knockdown efficacy, where cells with less RRM2 knockdown grow out, or due to the inherent heterogeneity of patient-derived models (37, 38). Nonetheless, we had enough power for our biostatical approach to indicate a significant slowing of tumor growth in the combination (Fig. 5A–B, S4D), which was likely due to two causes: 1) elimination of cells due to the induction of apoptosis during treatment (Fig. 2); and 2) maintenance of the senescence-associated cell growth arrest in those cells that did not undergo apoptosis (Fig. 3, 5E–F). Indeed, senescence is considered a bona fide tumor suppression mechanism and viable therapeutic outcome (39). Excitingly, the decrease in melanoma cell proliferation by the combinatorial inhibition of RRM2 and mutant BRAF is independent of PTEN, CDK4, or p16 status as WM793 cells have mutant PTEN and CDK4 and are homozygous deleted for CDKN2A (encodes for p16). Dysregulation of these pathways have been shown to be important for resistance to mutant BRAFi (40–42). Therefore, targeting nucleotide metabolism in combination with mutant BRAF inhibitors could overcome these resistance mechanisms.

As dNTPs are essential for tumor proliferation, RRM2 is an attractive therapeutic target (28, 43, 44). 3AP, the small molecule inhibitor used in this study, targets RRM2 primarily by deactivating the tyrosyl radical that is required for its function (45). In combination with DNA damaging agents such as cisplatin or radiation, 3AP shows synergistic activity (46, 47). 3AP is currently undergoing extensive clinical trials for a number of malignancies (clinicaltrials.gov). Another small-molecule inhibitor, COH29, binds RRM2 thus abrogating RNR complex formation (48). COH29 will soon undergo a Phase I clinical trial for patients with solid tumors (Clinicaltrials.gov). In addition to small molecule inhibitors, strategies of targeted RRM2 knockdown have also been developed. The 20-mer antisense oligonucleotide GTI2040 has shown promising results during Phase I clinical trials (49). Additionally, siRNAs targeting RRM2 inhibit the proliferation of head and neck tumors as well as melanoma cells (13, 50). These studies clearly indicate that targeting RRM2 could be therapeutically beneficial in a number of malignancies.

In summary, we found that inhibition of nucleotide metabolism through knockdown of RRM2 in combination with mutant BRAF inhibitor induced melanoma cell apoptosis and prolonged treatment response. Therefore, targeting nucleotide metabolism in combination with mutant BRAFi could be a feasible therapeutic strategy for mutant BRAF melanomas.

Supplementary Material

Implications.

Inhibition of RRM2 converts the transient response of melanoma cells to BRAFi to a stable response and may be a novel combinatorial strategy to prolong therapeutic response of melanoma patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Benjamin Bitler for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the NIH/NCI (Melanoma SPORE CA174523 to R.Z.; K99CA194309 to K.M.A.; PO1 CA076674 and CA182890 to M.H.), the Dr. Miriam and Sheldon G. Adelson Medical Research Foundation to M.H, and by the subsidy of the Russian Government to support the Program of competitive growth of Kazan Federal University (to N.F.). Support of Core Facilities used in this study was provided by Cancer Center Support Grant (CCSG) CA010815 to The Wistar Institute.

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of Interest: None to report

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Genomic Classification of Cutaneous Melanoma. Cell. 2015;161:1681–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hodis E, Watson IR, Kryukov GV, Arold ST, Imielinski M, Theurillat JP, et al. A landscape of driver mutations in melanoma. Cell. 2012;150:251–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Munoz-Couselo E, Garcia JS, Perez-Garcia JM, Cebrian VO, Castan JC. Recent advances in the treatment of melanoma with BRAF and MEK inhibitors. Annals of translational medicine. 2015;3:207. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2015.05.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robert C, Karaszewska B, Schachter J, Rutkowski P, Mackiewicz A, Stroiakovski D, et al. Improved overall survival in melanoma with combined dabrafenib and trametinib. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:30–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, Haanen JB, Ascierto P, Larkin J, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2507–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flaherty KT, Infante JR, Daud A, Gonzalez R, Kefford RF, Sosman J, et al. Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition in melanoma with BRAF V600 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1694–703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1210093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Long GV, Stroyakovskiy D, Gogas H, Levchenko E, de Braud F, Larkin J, et al. Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition versus BRAF inhibition alone in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1877–88. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carlino MS, Long GV, Kefford RF, Rizos H. Targeting oncogenic BRAF and aberrant MAPK activation in the treatment of cutaneous melanoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2015;96:385–98. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nordlund P, Reichard P. Ribonucleotide reductases. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:681–706. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Engstrom Y, Eriksson S, Jildevik I, Skog S, Thelander L, Tribukait B. Cell cycle-dependent expression of mammalian ribonucleotide reductase. Differential regulation of the two subunits. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:9114–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aird KM, Zhang G, Li H, Tu Z, Bitler BG, Garipov A, et al. Suppression of Nucleotide Metabolism Underlies the Establishment and Maintenance of Oncogene-Induced Senescence. Cell Rep. 2013;3:1252–65. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zuckerman JE, Hsueh T, Koya RC, Davis ME, Ribas A. siRNA knockdown of ribonucleotide reductase inhibits melanoma cell line proliferation alone or synergistically with temozolomide. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:453–60. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Satyamoorthy K, DeJesus E, Linnenbach AJ, Kraj B, Kornreich DL, Rendle S, et al. Melanoma cell lines from different stages of progression and their biological and molecular analyses. Melanoma Res. 1997;7(Suppl 2):S35–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ye X, Zerlanko B, Kennedy A, Banumathy G, Zhang R, Adams PD. Downregulation of Wnt signaling is a trigger for formation of facultative heterochromatin and onset of cell senescence in primary human cells. Mol Cell. 2007;27:183–96. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li H, Cai Q, Godwin AK, Zhang R. Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 promotes the proliferation and invasion of epithelial ovarian cancer cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2010;8:1610–8. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-10-0398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tu Z, Aird KM, Bitler BG, Nicodemus JP, Beeharry N, Zia B, et al. Oncogenic Ras regulates BRIP1 expression to induce dissociation of BRCA1 from chromatin, inhibit DNA repair, and promote senescence. Dev Cell. 2011;21:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aird KM, Li H, Xin F, Konstantinopoulos PA, Zhang R. Identification of ribonucleotide reductase M2 as a potential target for pro-senescence therapy in epithelial ovarian cancer. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:199–207. doi: 10.4161/cc.26953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amatangelo MD, Garipov A, Li H, Conejo-Garcia JR, Speicher DW, Zhang R. Three-dimensional culture sensitizes epithelial ovarian cancer cells to EZH2 methyltransferase inhibition. Cell Cycle. 2013;12:2113–9. doi: 10.4161/cc.25163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krepler C, Xiao M, Spoesser K, Brafford PA, Shannan B, Beqiri M, et al. Personalized pre-clinical trials in BRAF inhibitor resistant patient derived xenograft models identify second line combination therapies. Clin Cancer Res. 2015 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finch RA, Liu MC, Cory AH, Cory JG, Sartorelli AC. Triapine (3-aminopyridine-2-carboxaldehyde thiosemicarbazone; 3-AP): an inhibitor of ribonucleotide reductase with antineoplastic activity. Adv Enzyme Regul. 1999;39:3–12. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2571(98)00017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haferkamp S, Borst A, Adam C, Becker TM, Motschenbacher S, Windhovel S, et al. Vemurafenib induces senescence features in melanoma cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:1601–9. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Z, Jiang K, Zhu X, Lin G, Song F, Zhao Y, et al. Encorafenib (LGX818), a potent BRAF inhibitor, induces senescence accompanied by autophagy in BRAFV600E melanoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2016;370:332–44. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luoto KR, Meng AX, Wasylishen AR, Zhao H, Coackley CL, Penn LZ, et al. Tumor cell kill by c-MYC depletion: role of MYC-regulated genes that control DNA double-strand break repair. Cancer Res. 2010;70:8748–59. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carlino MS, Gowrishankar K, Saunders CA, Pupo GM, Snoyman S, Zhang XD, et al. Antiproliferative effects of continued mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway inhibition following acquired resistance to BRAF and/or MEK inhibition in melanoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12:1332–42. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vredeveld LC, Possik PA, Smit MA, Meissl K, Michaloglou C, Horlings HM, et al. Abrogation of BRAFV600E-induced senescence by PI3K pathway activation contributes to melanomagenesis. Genes Dev. 2012;26:1055–69. doi: 10.1101/gad.187252.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mannava S, Moparthy KC, Wheeler LJ, Natarajan V, Zucker SN, Fink EE, et al. Depletion of deoxyribonucleotide pools is an endogenous source of DNA damage in cells undergoing oncogene-induced senescence. Am J Pathol. 2013;182:142–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aird KM, Zhang R. Nucleotide metabolism, oncogene-induced senescence and cancer. Cancer Lett. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jewell R, Conway C, Mitra A, Randerson-Moor J, Lobo S, Nsengimana J, et al. Patterns of expression of DNA repair genes and relapse from melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:5211–21. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song L, Robson T, Doig T, Brenn T, Mathers M, Brown ER, et al. DNA repair and replication proteins as prognostic markers in melanoma. Histopathology. 2013;62:343–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2012.04362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chapman JR, Taylor MR, Boulton SJ. Playing the end game: DNA double-strand break repair pathway choice. Mol Cell. 2012;47:497–510. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Estrada-Bernal A, Chatterjee M, Haque SJ, Yang L, Morgan MA, Kotian S, et al. MEK inhibitor GSK1120212-mediated radiosensitization of pancreatic cancer cells involves inhibition of DNA double-strand break repair pathways. Cell Cycle. 2015;14:3713–24. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2015.1104437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lim JW, Kim H, Kim KH. Expression of Ku70 and Ku80 mediated by NF-kappa B and cyclooxygenase-2 is related to proliferation of human gastric cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:46093–100. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206603200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arias-Lopez C, Lazaro-Trueba I, Kerr P, Lord CJ, Dexter T, Iravani M, et al. p53 modulates homologous recombination by transcriptional regulation of the RAD51 gene. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:219–24. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen CS, Wang YC, Yang HC, Huang PH, Kulp SK, Yang CC, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors sensitize prostate cancer cells to agents that produce DNA double-strand breaks by targeting Ku70 acetylation. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5318–27. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen J. Ataxia telangiectasia-related protein is involved in the phosphorylation of BRCA1 following deoxyribonucleic acid damage. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5037–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cho SY, Kang W, Han JY, Min S, Kang J, Lee A, et al. An Integrative Approach to Precision Cancer Medicine Using Patient-Derived Xenografts. Mol Cells. 2016;39:77–86. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2016.2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cassidy JW, Caldas C, Bruna A. Maintaining Tumor Heterogeneity in Patient-Derived Tumor Xenografts. Cancer Res. 2015;75:2963–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nardella C, Clohessy JG, Alimonti A, Pandolfi PP. Pro-senescence therapy for cancer treatment. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:503–11. doi: 10.1038/nrc3057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paraiso KH, Xiang Y, Rebecca VW, Abel EV, Chen YA, Munko AC, et al. PTEN loss confers BRAF inhibitor resistance to melanoma cells through the suppression of BIM expression. Cancer Res. 2011;71:2750–60. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yadav V, Chen SH, Yue YG, Buchanan S, Beckmann RP, Peng SB. Co-targeting BRAF and cyclin dependent kinases 4/6 for BRAF mutant cancers. Pharmacol Ther. 2015;149:139–49. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smalley KS, Lioni M, Dalla Palma M, Xiao M, Desai B, Egyhazi S, et al. Increased cyclin D1 expression can mediate BRAF inhibitor resistance in BRAF V600E-mutated melanomas. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:2876–83. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mathews CK. Deoxyribonucleotide metabolism, mutagenesis and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15:528–39. doi: 10.1038/nrc3981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aye Y, Li M, Long MJ, Weiss RS. Ribonucleotide reductase and cancer: biological mechanisms and targeted therapies. Oncogene. 2015;34:2011–21. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aye Y, Long MJ, Stubbe J. Mechanistic studies of semicarbazone triapine targeting human ribonucleotide reductase in vitro and in mammalian cells: tyrosyl radical quenching not involving reactive oxygen species. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:35768–78. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.396911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kunos CA, Radivoyevitch T, Waggoner S, Debernardo R, Zanotti K, Resnick K, et al. Radiochemotherapy plus 3-aminopyridine-2-carboxaldehyde thiosemicarbazone (3-AP, NSC #663249) in advanced-stage cervical and vaginal cancers. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;130:75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kunos C, Radivoyevitch T, Abdul-Karim FW, Fanning J, Abulafia O, Bonebrake AJ, et al. Ribonucleotide reductase inhibition restores platinum-sensitivity in platinum-resistant ovarian cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J Transl Med. 2012;10:79. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou B, Su L, Hu S, Hu W, Yip ML, Wu J, et al. A small-molecule blocking ribonucleotide reductase holoenzyme formation inhibits cancer cell growth and overcomes drug resistance. Cancer Res. 73:6484–93. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Klisovic RB, Blum W, Wei X, Liu S, Liu Z, Xie Z, et al. Phase I study of GTI-2040, an antisense to ribonucleotide reductase, in combination with high-dose cytarabine in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3889–95. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rahman MA, Amin AR, Wang X, Zuckerman JE, Choi CH, Zhou B, et al. Systemic delivery of siRNA nanoparticles targeting RRM2 suppresses head and neck tumor growth. J Control Release. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.01.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.