Abstract

Purpose

Prognostic factors in patients receiving salvage systemic therapy for advanced urothelial carcinoma (UC) include performance status (PS), liver metastasis (LM), hemoglobin (Hb) and time from prior chemotherapy (TFPC). We investigated the impact of albumin and neutrophil, lymphocyte and platelet counts.

Materials and methods

Patient level data from 10 phase II trials were utilized. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to evaluate their association with overall survival (OS). An optimal regression model was constructed using forward stepwise selection and risk groups defined using number of adverse factors. Trial was a stratification factor. External validation was conducted in a separate dataset of 5 salvage phase II trials.

Results

Data for discovery was obtained from 708 patients. After adjustment for the 4 known factors, platelet ≥upper limit of normal and albumin <lower limit of normal were significant poor prognostic factors. Only the addition of albumin was externally validated. The median OS (months) was 8.9, 6.4, 4.5 for 0–1, 2, 3+ risk factors (n=207, 171, 113) in the discovery dataset (n=491), and 10.6, 10.0, 7.0 with n=73, 47, 47 in the validation dataset (n=167). The c-index improved from 0.610 to 0.639 in the discovery set and from 0.616 to 0.646 in the validation set by adding albumin.

Conclusions

Albumin was externally validated as a prognostic factor for OS after accounting for TFPC, Hb, PS and LM status in patients receiving salvage systemic therapy for advanced UC. The discovery of molecular prognostic factors is a priority to further enhance this new preferred 5-factor clinical prognostic model.

Keywords: Advanced urothelial carcinoma, Salvage therapy, Prognosis, Albumin, Survival

Introduction

The survival outcomes of patients receiving salvage therapy for advanced urothelial carcinoma (UC) differs based on baseline prognostic factors. A 3-factor prognostic model consisting of Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG)-Performance Status (PS) >0, hemoglobin (Hb) <10 g/dL and liver metastasis (LM) was proposed by Bellmunt et al 1. Thereafter, the addition of a fourth factor, time from prior chemotherapy (TFPC), to the aforementioned 3 factors was reported to enhance the prognostic classification 2. However, these models do not provide optimal discrimination of survival and there remains substantial room for improvement.

A rationale may be offered to investigate the prognostic impact of other readily available candidate laboratory prognostic factors. These candidate factors include the neutrophil count, lymphocyte count, platelet count and albumin, since they have been demonstrated to be prognostic in other advanced solid malignancies 3, 4. Moreover, in the context of first-line platinum-based chemotherapy for advanced UC, the inclusion of hypoalbuminemia or leukocytosis enhanced separate prognostic models 5, 6. Therefore, we retrospectively analyzed a large pooled dataset of prospective phase II trials to evaluate the impact of these candidate variables in the salvage therapy setting of advanced UC independent of previously established factors, i.e. Hb, PS, LM and TFPC.

Patients and methods

Patient population

Ten prospective phase II trials of salvage systemic chemotherapy and/or biologic agent therapy following platinum-based chemotherapy for advanced UC were pooled in the discovery dataset 7–15. These 10 trials were used to discover the potential role of selected new risk factors because they were already available and had been previously used for other retrospective analyses. Thereafter, 5 other phase II trials of salvage therapy were pooled in the validation dataset 16–20. All of these trials required previous pathological confirmation of UC and the presence of measurable metastatic disease. Trials conducted after the year 2000 were selected based on the availability of individual patient level data and willingness of the respective principal investigators to provide these data. Data regarding neutrophil count, lymphocyte count, platelet count and albumin were required in addition to TFPC, Hb, ECOG-PS and LM status. The data were deidentified and provided in an Excel spreadsheet by all investigators. The included trials were approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) of the respective institutions, and this retrospective study was conducted after IRB approval at the University of Alabama, Birmingham (UAB) for retrospective analyses of such patients.

Statistical methods

OS was the primary clinical endpoint and was calculated from the date of study entry until death from any cause. Objective tumor assessment was performed by RECIST 1.0 in all trials except the trial evaluating pazopanib by Necchi et al, which used RECIST 1.1 12, 21, 22. Times to event outcomes were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to evaluate the association of neutrophil count, lymphocyte count, platelet count and albumin with OS adjusted for PS, Hb, LM and TFPC. Neutrophil count, lymphocyte count, platelet count and albumin were dichotomized as <lower limit of normal (LLN) or ≥upper limit of normal (ULN). The LLN and ULN employed uniformly for these variables were as follows: neutrophils 1500–7000 cells/mm3, lymphocytes: 1000–3000 cells/mm3, platelets: 150,000–400,000 cells/mm3, and albumin 3.5–5.5 gm/dl.

Trial was included as a stratification factor throughout. Patients in the Choueiri trial receiving docetaxel +/− vandetanib were included as one trial when stratifying for our analysis since there were no significant differences in OS between these arms 7. Patients in the trial by Gallagher et al evaluated sunitinib administered in 2 doses and schedules (50 mg daily for 4 of every 6 weeks or 37.5 mg daily continuously); hence, the different regimens were assigned a separate stratification 11. Internal validation was performed using bootstrap methods, with 95% bias-corrected and accelerated (BCa) confidence intervals, p-values and concordance statistics (c-index) calculated. External validation involved applying the risk groups defined from the development dataset to the validation dataset. All tests were two-sided and a p-value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

In the discovery dataset, of 708 patients overall, 682 were evaluable for this analysis with available PS, Hb, LM and TFPC status (Url). The neutrophil count, lymphocyte count, platelet count and albumin were available in 631, 554, 649 and 491 patients, respectively. A total of 444 patients had data on all of the above 8 variables. Data were available for all evaluated variables in all 167 patients in the validation dataset: PS, Hb, LM, TFPC, platelet count and albumin. There was no statistically (p>0.05) significant differences between the discovery and validation datasets in terms of age, gender, ECOG-PS and platelets ≥ULN. The median OS of evaluable patients in the discovery and validation datasets were 6.8 (95% CI=6.0–7.0) months (mo) and 9.4 (8.7–10.0) mo, respectively (p<0.001). Median TFPC was longer (4.4 vs. 2.7 mo, p<0.001) and more patients had LM (34% vs. 22%, p=0.002) in the discovery dataset. More patients had albumin <LLN (32% vs. 16%, p<0.001) and Hb <10 g/dL in the validation dataset (37% vs. 14%, p<0.001).

Univariable analyses to evaluate the impact of factors on OS

Univariable analyses in the discovery dataset identified 7 factors significantly associated with OS: PS, Hb, LM, TFPC, neutrophils ≥ULN, platelets ≥ULN and Albumin <LLN (Table 1). Additionally, the neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio (NLR) was also significantly associated with OS; however, NLR was not investigated further as it was not observed to add any additional information beyond neutrophils by itself.

Table 1.

Univariate analyses of potential new prognostic factors for overall survival in the discovery dataset

| Factor | Factor Type | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p-value | C-index |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UNIVARIATE ANALYSIS | ||||

| Neutrophils | Log-transformed | 1.89 (1.55, 2.31) | <0.001 | 0.585 |

| Lymphocytes | Log-transformed | 0.94 (0.76, 1.16) | 0.56 | 0.509 |

| Albumin | Log-transformed | 0.16 (0.08, 0.35) | <0.001 | 0.568 |

| Platelets | Log-transformed | 1.71 (1.32, 2.22) | <0.001 | 0.555 |

| Neutrophil/Lymphocyte ratio (NLR) | Log-transformed | 1.42 (1.20, 1.67) | <0.001 | 0.568 |

| Neutrophils | ≥ULN | 1.74 (1.41, 2.14) | <0.001 | 0.548 |

| Lymphocytes | <LLN | 1.13 (0.91, 1.39) | 0.28 | 0.515 |

| Albumin | <LLN | 2.12 (1.61, 2.80) | <0.001 | 0.558 |

| Platelets | ≥ULN | 2.17 (1.68, 2.81) | <0.001 | 0.539 |

| NLR | ≥5 | 1.46 (1.17, 1.83) | 0.001 | 0.546 |

ULN: upper limit of normal, LLN: lower limit of normal

Multivariable analysis to evaluate the independent impact of factors on OS

After adjustment for TFPC <3 mo, Hb <10 g/dl, PS >0 and LM status, only platelets ≥ULN and Albumin <LLN remained significant (Table 2). This 6-factor prognostic model was internally validated using bootstrapping; the mean c-index across bootstrap samples was 0.610 for the 4-factor model and a mean of 0.649 for the 6-factor model. The mean c-index was 0.639 for a 5-factor model model including the 4-factor model variables and albumin <LLN.

Table 2.

Multivariate analyses

| Discovery (n=491) | Validation (n=167) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value |

| TFPC <3 months | 1.49 (1.19, 1.87) | <0.001 | 1.35 (0.87, 2.08) | 0.18 |

| ECOG PS>0 | 1.39 (1.16, 1.67) | <0.001 | 1.58 (1.06, 2.35) | 0.023 |

| Liver metastasis | 1.45 (1.16, 1.81) | <0.001 | 1.26 (0.83, 1.90) | 0.27 |

| Hb <10 g/dl | 1.73 (1.27, 2.35) | <0.001 | 1.35 (0.94, 1.96) | 0.10 |

| Albumin <LLN | 1.61 (1.20, 2.15) | 0.002 | 1.90 (1.27, 2.85) | 0.002 |

In the discovery dataset, platelets ≥ULN (upper limit of normal) was also significant on multivariate analysis (HR 2.00 [1.42, 2.80], p<0.001); however, the validation dataset did not demonstrate its independent significance. Hence, the table above presents results for the 4 previously known factors (Hb [hemoglobin], TFPC [time from prior chemotherapy], LM [liver metastasis], PS [performance status]) + albumin <LLN (lower limit of normal) since only the addition of Alb <LLN was externally validated. The c-index improved from 0.610 to 0.639 in the discovery set and from 0.616 to 0.646 in the validation set by adding Albumin<LLN to the previously identified 4 factors.

External validation to evaluate the impact of independently significant factors on OS

Only the addition of Albumin <LLN was independently significantly associated with poor OS and externally validated after accounting for the previous 4-factor model (Table 2). The c-index improved from a mean of 0.616 across bootstrap samples in the 4-factor model to a mean c-index across bootstrap samples of 0.646 with the addition of albumin <LLN. There was no interaction effect between albumin and any of the previously known 4 prognostic factors in either the discovery or validation datasets. Platelets ≥ULN was not independently significant after adjusting for TFPC <3 mo, Hb <10 g/dl, PS >0 and LM status (p-value=0.43), and the c-index of 0.623 was only nominally improved over that from the 4-factor model. Interestingly, 3 of the previously identified prognostic factors (Hb, TFPC and LM) were not independently statistically significant (Table 2) in the final model using the external validation dataset, despite having similar HRs as was observed in the discovery dataset. Supportive analyses were performed using progression-free survival as the outcome, and risk score (number of 4 previously identified adverse risk factors) as a single prognostic covariate instead of all 4 factors separately, with similar results (data not shown).

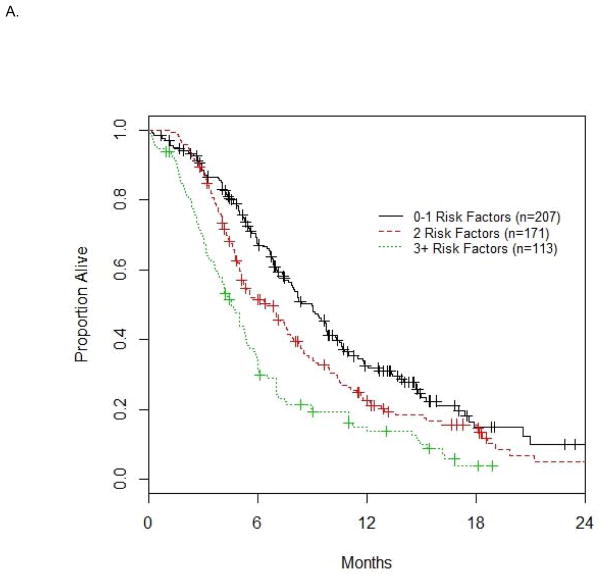

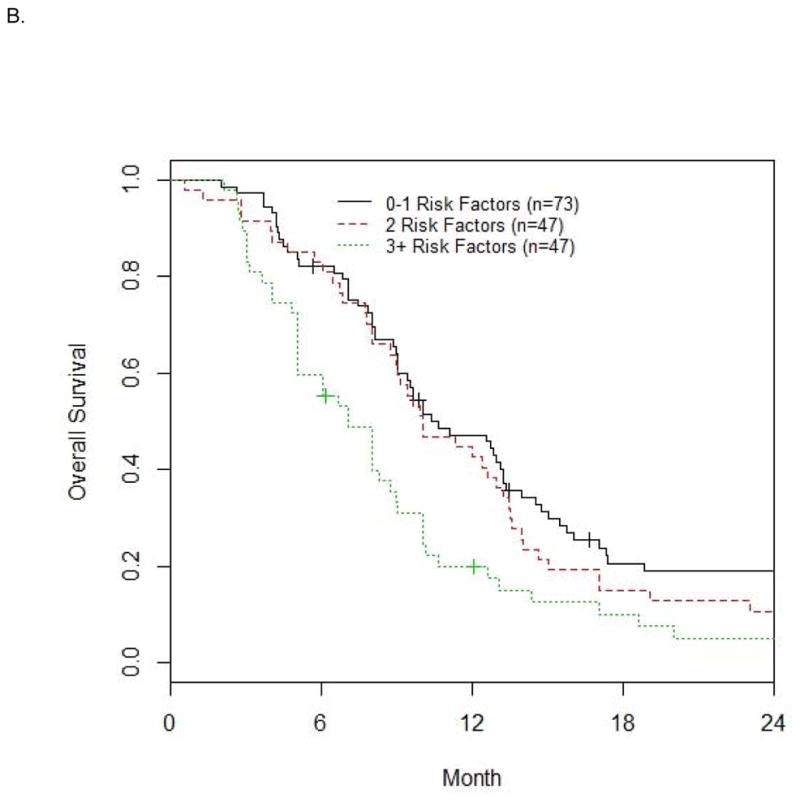

Based on the 4 a priori defined risk factors and albumin <LLN, the number of risk factors exhibited by each patient was calculated. The median OS was 8.9, 6.4 and 4.5 mo for patients with 0–1, 2 and 3+ risk factors (n=207, 171, 113 in these 3 groups, respectively) in the discovery dataset (n=491, Figure 1A), and 10.6, 10.0 and 7.0 mo (n=73, 47, 47 in these 3 groups, respectively) in the validation dataset (n=167, Figure 1B). The differences in median OS for 0–1, 2 and 3+ risk factor groups were significant overall for both the discovery (p<0.001) and validation (p=0.014) datasets.

Figure 1. Survival based on number of risk factors in the discovery (A) and validation datasets (B).

The median OS (mo) is 8.9, 6.4, 4.5 for 0–1, 2, 3+ risk factors (n=207, 171, 113) in the discovery dataset (n=491) in Fig. 1A, and 10.6, 10.0, 7.0 with n=73, 47, 47 in the validation dataset (n=167) in Fig. 1B.

Discussion

This retrospective analysis of prospective phase II trials identified and externally validated albumin <LLN as an additional poor prognostic factor for OS after controlling for previously known poor prognostic factors, i.e. ECOG-PS >0, Hb <10 g/dL, TFPC <3 months and LM 1, 2. The addition of albumin to the previously identified factors improved the c-index to 0.639 (from 0.610) in the discovery dataset and 0.632 (from 0.601) in the validation dataset. Notably, an improvement in the c-index in excess of 0.015 is deemed as being clinically relevant 23. Although platelets ≥ULN was statistically significant in the discovery dataset, it did not meet statistical significance in the validation dataset, and the improvement in c-index after adjusting for the other 5 factors (including albumin) did not exceed the threshold for clinical relevance. Thus, the addition of albumin <LLN to create an improved 5-factor prognostic model for OS is warranted. This 5-factor model resembles and harmonizes with a prognostic model proposed in the setting of first-line cisplatin-based chemotherapy, which includes PS, Hb, albumin and visceral metastasis 5.

Albumin is produced in the liver and is a reflection of nutritional status and inflammatory processes. The Glasgow prognostic score (GPS) which includes albumin and c-reactive protein (CRP), has been demonstrated to be prognostic in a number of malignancies 24. The modified (m)GPS was then devised to capture the observation that hypoalbuminemia without an elevated CRP level was rare and not associated with poor survival 25. However, our dataset could not evaluate the prognostic impact of CRP since this is not usually routinely measured in patients with advanced UC.

In addition to platelets ≥ULN, neutrophil count ≥ULN and NLR were both also statistically significant on univariable analyses in the discovery dataset. Potentially, the use of larger discovery and validation datasets may have demonstrated the significance of many more of these candidate variables. Indeed, neutrophilia and thrombocytosis are prognostic in other solid tumors such as renal cell carcinoma 4. Nevertheless, the neutrophil count, lymphocyte count, platelet count and albumin have not been previously concurrently investigated in the same study for their prognostic impact, and it is possible that albumin <LLN best captures most of the impact of inflammation and nutrition on survival. Tumor tissue and host germline molecular biomarkers may further complement our prognostic model and allow better discrimination of survival or benefit from chemotherapy 26.

The retrospective design of our study is a limitation, but we utilized individual patient level data from well conducted prospective phase II trials. Despite some heterogeneity in the eligibility criteria and patient characteristics in the different pooled trials, all trials included patients with unresectable locally advanced or metastatic disease who had progressed following prior platinum-based therapy. Both the discovery and validation datasets may be characterized as dominated by conventional salvage chemotherapy using a taxane or vinflunine, i.e. 100% of patients in the validation dataset received a taxane based chemotherapy, while 517/682 (75.8%) patients in the discovery dataset received a taxane or vinflunine. The impact of co-morbidities on survival is difficult to ascertain, although most of these trials included patients with satisfactory PS (generally 0–1). The laboratory variables evaluated were not available in all discovery dataset patients; nevertheless, albumin was available in the majority of patients (491 of 682, 72%). However, the validation dataset did have all evaluated variables available in 100% of 167 patients. Longer TFPC and LM were seen more often in the discovery dataset, while albumin <LLN and Hb <10 g/dL were more common in the validation dataset. Notwithstanding this heterogeneity in baseline factors when comparing the discovery and validation pooled trial datasets, these trials had similar inclusion criteria and outcomes observed in these two groups of trials were similarly poor. The sample size of the validation dataset was somewhat modest, and there were only 47 patients each of the groups with 2 and 3+ risk factors. Given that the data were derived from clinical trials, the applicability to patients ineligible for trials or treated off-trials may be questioned. The prognostic impact of other candidate factors such as number of lines of prior therapy, prior response, prior setting of chemotherapy (perioperative or metastatic) were not re-examined since we have already demonstrated their lack of independent significance27–29.

Conclusions

To conclude, a new, improved and updated 5-factor prognostic model in the setting of salvage therapy for advanced UC is proposed, based on results from two separate datasets of phase II clinical trials. Given the ready, affordable and universal availability of serum albumin levels, the immediate adoption of this prognostic model in clinical trials and in routine practice is warranted. The use of this model will enhance the interpretation of clinical trials. Additionally, the relevance of this 5-factor model should be studied in the setting of new classes of salvage therapy, e.g. immunotherapy with programmed death [PD]-1 inhibitors 30. In the setting of more effective agents, it is possible that the poor prognostic impact of some factors will be abolished. Finally, the discovery of novel molecular prognostic factors should be now vigorously pursued to improve prognostication and generate insights on therapeutic targets.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The following collaborators made substantial contributions to this study by providing the patient data and approving the final manuscript: Ashley M. Regazzi, MS (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY), Stephanie Mullane, MS (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA), Guenter Niegisch, MD (Heinrich Heine University, Dusseldorf, Germany), Peter Albers, MD (Heinrich Heine University, Dusseldorf, Germany), Ronan Fougeray, MD (Institut de Recherche Pierre Fabre, Boulogne, France), Srikala S. Sridhar, MD (Princess Margaret Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada), Yoo-Joung Ko, MD (Sunnybrook Odette Cancer Centre, Toronto, ON, Canada), Matthew D. Galsky, MD (Mount Sinai Cancer Center, New York, NY), Matthew I. Milowsky, MD (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC), Antonio Rozzi, MD (Istituto Neurotraumatologico Italiano, Grottaferrata, Italy), Kazumasa Matsumoto, MD (Kitasato University School of Medicine, Sagamihara, Japan), Jae-Lyun Lee, MD (Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, South Korea), Hiroshi Kitamura, MD (Sapporo Medical University School of Medicine, Sapporo, Japan), Haruki Kume, MD (University of Tokyo Hospital, Tokyo, Japan).

Footnotes

Presented in part at the Genitourinary Cancer Symposium February 2015, Orlando, FL, USA

Relevant disclosures: None

Funding sources for study: None

References

- 1.Bellmunt J, Choueiri TK, Fougeray R, et al. Prognostic factors in patients with advanced transitional cell carcinoma of the urothelial tract experiencing treatment failure with platinum-containing regimens. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1850. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sonpavde G, Pond GR, Fougeray R, et al. Time from prior chemotherapy enhances prognostic risk grouping in the second-line setting of advanced urothelial carcinoma: a retrospective analysis of pooled, prospective phase 2 trials. Eur Urol. 2013;63:717. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.11.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Templeton AJ, McNamara MG, Seruga B, et al. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju124. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heng DY, Xie W, Regan MM, et al. External validation and comparison with other models of the International Metastatic Renal-Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium prognostic model: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:141. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70559-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Apolo AB, Ostrovnaya I, Halabi S, et al. Prognostic model for predicting survival of patients with metastatic urothelial cancer treated with cisplatin-based chemotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:499. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galsky MD, Moshier E, Krege S, et al. Nomogram for predicting survival in patients with unresectable and/or metastatic urothelial cancer who are treated with cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Cancer. 2013;119:3012. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choueiri TK, Ross RW, Jacobus S, et al. Double-blind, randomized trial of docetaxel plus vandetanib versus docetaxel plus placebo in platinum-pretreated metastatic urothelial cancer. J Clin Oncol. 30:507. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.7002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaughn DJ, Srinivas S, Stadler WM, et al. Vinflunine in platinum-pretreated patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma: results of a large phase 2 study. Cancer. 2009;115:4110. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albers P, Park SI, Niegisch G, et al. Randomized phase III trial of 2nd line gemcitabine and paclitaxel chemotherapy in patients with advanced bladder cancer: short-term versus prolonged treatment [German Association of Urological Oncology (AUO) trial AB 20/99] Ann Oncol. 22:288. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ko YJ, Canil CM, Mukherjee SD, et al. Nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel for second-line treatment of metastatic urothelial carcinoma: a single group, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:769. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70162-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gallagher DJ, Milowsky MI, Gerst SR, et al. Phase II study of sunitinib in patients with metastatic urothelial cancer. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28:1373. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.3922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Necchi A, Mariani L, Zaffaroni N, et al. Pazopanib in advanced and platinum-resistant urothelial cancer: an open-label, single group, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:810. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70294-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milowsky MI, Iyer G, Regazzi AM, et al. Phase II study of everolimus in metastatic urothelial cancer. BJU Int. 2013;112:462. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11720.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Di Lorenzo G, Montesarchio V, Autorino R, et al. Phase 1/2 study of intravenous paclitaxel and oral cyclophosphamide in pretreated metastatic urothelial bladder cancer patients. Cancer. 2009;115:517. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Culine S, Theodore C, De Santis M, et al. A phase II study of vinflunine in bladder cancer patients progressing after first-line platinum-containing regimen. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:1395. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rozzi A, Salerno M, Bordin F, et al. Weekly regimen of epirubicin and paclitaxel as second-line chemotherapy in patients with metastatic transitional cell carcinoma of urothelial tract: results of a phase II study. Med Oncol. 2011;28(Suppl 1):S426. doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9749-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ikeda M, Matsumoto K, Tabata K, et al. Combination of gemcitabine and paclitaxel is a favorable option for patients with advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma previously treated with cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2011;41:1214. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyr131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee JL, Ahn JH, Park SH, et al. Phase II study of a cremophor-free, polymeric micelle formulation of paclitaxel for patients with advanced urothelial cancer previously treated with gemcitabine and platinum. Invest New Drugs. 2012;30:1984. doi: 10.1007/s10637-011-9757-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kitamura H, Taguchi K, Kunishima Y, et al. Paclitaxel, ifosfamide, and nedaplatin as second-line treatment for patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma: a phase II study of the SUOC group. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:1171. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.01909.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kakutani S, Fukuhara H, Taguchi S, et al. Combination of docetaxel, ifosfamide and cisplatin (DIP) as a potential salvage chemotherapy for metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2015;45:281. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyu201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2000;92:205. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nguyen CT, Kattan MW. How to tell if a new marker improves prediction. Eur Urol. 2011;60:226. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Forrest LM, McMillan DC, McArdle CS, et al. Comparison of an inflammation-based prognostic score (GPS) with performance status (ECOG) in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy for inoperable non-small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:1704. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McMillan DC, Crozier JE, Canna K, et al. Evaluation of an inflammation-based prognostic score (GPS) in patients undergoing resection for colon and rectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:881. doi: 10.1007/s00384-006-0259-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gallagher DJ, Vijai J, Hamilton RJ, et al. Germline single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with response of urothelial carcinoma to platinum-based therapy: the role of the host. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:2414. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pond GR, Bellmunt J, Rosenberg JE, et al. Impact of the number of prior lines of therapy and prior perioperative chemotherapy in patients receiving salvage therapy for advanced urothelial carcinoma: implications for trial design. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2015;13:71. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pond GR, Bellmunt J, Fougeray R, et al. Impact of response to prior chemotherapy in patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma receiving second-line therapy: implications for trial design. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2013;11:495. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2013.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sonpavde G, Bellmunt J, Rosenberg JE, et al. Patient eligibility and trial design for the salvage therapy of advanced urothelial carcinoma. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2014;12:395. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2014.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Powles T, Eder JP, Fine GD, et al. MPDL3280A (anti-PD-L1) treatment leads to clinical activity in metastatic bladder cancer. Nature. 2014;515:558. doi: 10.1038/nature13904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.