Abstract

Aim:

The objective of this pilot study was to determine the accuracy of point-of-care B-line lung ultrasound in comparison to NT Pro-BNP for screening acute heart failure.

Materials and Methods:

An 8-zone lung ultrasound was performed by experienced sonographers in patients presenting with acute dyspnea in the ED. AHF was determined as the final diagnosis by 2 independent reviewers.

Results:

Contrary to prior studies, B-line ultrasound in our study was highly specific, but moderately sensitive for identifying patients with AHF. There was a strong association between elevated NT-proBNP levels and an increased number of B-lines.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, point-of-care lung ultrasound is a helpful tool for ruling in or ruling out important differential diagnoses in ED patients with acute dyspnea.

Key words: thorax, chest ultrasound, thoracic ultrasound, emergency care

Introduction

Acute dyspnoea is a common chief complaint of patients presenting to the emergency department (ED) and is associated with high morbidity and mortality. About 50% of dyspnoeic patients display acute heart failure (AHF) 1. Rapid accurate diagnosis of AHF is hindered due to lacking sensitivity and specificity of clinical signs and symptoms. The primary aim of this pilot study was to determine the accuracy of point of care ultrasound for evaluation of acute dyspnea in the ED in comparison to circulating N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) levels.

Methods

We enrolled a convenience sample of 25 patients (≥ 18 years) presenting with undifferentiated acute dyspnoea to the ED of a German urban academic hospital. The study was approved by the local ethical committee. After obtaining written informed consent, 2 experienced sonographers performed an 8-zone lung ultrasound (LUS; 2–5 MHz phased array transducer, General Electric Vivid S6). Scans were evaluated offline by 2 medical experts blinded to clinical data (Cohens kappa=0.9). Positive ultrasound confirmation of AHF was defined, as the bilateral existence of 2 or more positive regions with 3 or more B-lines. Clinical and demographic data, comorbidities, laboratory test results, transthoracic echocardiographic (TTE) data and 12-lead electrocardiography (ECG) data were obtained by reviewing all medical records available.

Final adjudicated diagnosis of acute heart failure was done by 2 experience physicians (cardiologist, emergency physician). If a disagreement about AHF diagnosis was present, a third experienced cardiologist settled disagreement 2 3.

Primary endpoint was the accuracy of LUS for screening of AHF and compare it to circulating NT-proBNP levels. Continuous variables are presented as means (± SD) or medians (interquartile range [IQR]), categorical variables as numbers and percentages. Comparisons of different diagnostic tools or in different subgroups of patients were performed using the Mann-Whitney U test for independent variables. For categorical data the Pearson chi-square, respectively Fisher’s exact test was used. Proportions are described with 95% confidence intervals (CI). P-values<0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using SPSS IBM Statistik 20 version for Windows, Munich, Germany.

Results

25 patients were included for analysis (Table 1). Median age was 72 years (IQR 60.5–80.5), 68% (n=17) were male and 76% (n=19) had a previous history of chronic heart failure (CHF). 60% (n=15) of patients had a final adjudicated diagnosis of AHF.

Table 1 Patient characteristics and diagnostic parameters.

| variables | whole cohort, n=25 | AHF, n=15 | no AHF, n=10 | p= |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| demography | ||||

| age, median (Q1–Q3) | 72 (60.5–80.5) | 80 (65–81) | 63.5 (40.25–72.25) | 0.011 |

| male, n (%) | 17 (68.0) | 11 (73.3) | 6 (69.0) | 0.667 |

| vitals at first contact | ||||

| heart rate, bpm | 90 | 88 | 92 | 0.698 |

| systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 138 | 136 | 140 | 0.651 |

| diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 78 | 76 | 82 | 0.438 |

| oxygen saturation, % | 96.0 | 96.0 | 96.0 | 0.922 |

| respiratory rate, bpm | 17 | 18 | 16 | 0.64 |

| temperature, C | 36.7 | 36.7 | 36.7 | 0.897 |

| history | ||||

| chronic heart failure, n (%) | 19 (76.0) | 15 (100) | 4 (40.0) | 0.001 |

| previous myocardial infarction, n (%) | 5 (20.0) | 4 (26.7) | 1 (10.0) | 0.615 |

| coronary artery disease, n (%) | 14 (56.0) | 11 (73.3) | 3 (39.0) | 0.032 |

| hypertension, n (%) | 22 (88.0) | 15 (100) | 7 (70.0) | 0.052 |

| chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, n (%) | 6 (24.0) | 3 (20.0) | 3 (30.0) | 0.653 |

| malignancy, n (%) | 5 (20.0) | 4 (26.7) | 1 (10.0) | 0.615 |

| final diagnosis | ||||

| cardiac, n (%) | 15 (60.0) | 14 (93.3) | 1 (10.0) | <0.001 |

| pulmonary, n (%) | 3 (12.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (30.0) | 0.052 |

| mixed cardiac pulmonary, n (%) | 1 (4.0) | 1 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 |

| other, n (%) | 6 (24.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (60.0) | 0.001 |

| AHF, n (%) | 15 (60.0) | 15 (100) | 0 (0.0) | |

| no AHF, n (%) | 10 (40.0) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (100) | |

| laboratory test | ||||

| sodium, mmol/L | 139.6 | 139 | 140.5 | 0.503 |

| potassium, mmol/L | 4.192 | 4.28 | 4.06 | 0.253 |

| creatinine, mg/dL | 1.23 | 1.45 | 0.9 | 0.007 |

| BUN, mmol/L | 23.75 | 30.72 | 13.31 | 0.001 |

| NT-proBNP, (pg/ml) | 5 244 | 7 214 | 320 | 0.005 |

| cTnT-hs, ng/L | 0.0391 | 0.0443 | 0.0312 | 0.005 |

| 12-lead EC | ||||

| sinus rhythm, n (%) | 15 (60.0) | 6 (40.0) | 9 (90.0) | 0.012 |

| atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 9 (36.0) | 8 (53.3) | 1 (10.0) | 0.027 |

| other rhythm, n (%) | 1 (4.0) | 1 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 |

| left bundle branch block, n (%) | 3 (12.0) | 2 (13.3) | 1 (10.0) | 1 |

| right bundle brunch block, n (%) | 1 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (10.0) | 0.4 |

| pacemaker rhythm, n (%) | 1 (4.0) | 1 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 |

| ST elevation, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | _ |

| myocardial ischemia, n (%) | 5 (20.0) | 3 (20.0) | 2 (20.0) | 1 |

| lung ultrasound | ||||

| LUS positive for AHF, n (%) | 6 (24.0) | 6 (40.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.051 |

| echocardiography | ||||

| LVEDD, mm | 56.1 | 56.7 | 54.5 | 0.777 |

| EF, % | 44.6 | 40.5 | 54.8 | 0.062 |

| LA, ml | 90.8 | 93.9 | 83 | 1 |

| chest X-ray | ||||

| Overall impression, (mean) | 1.9 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 0.059 |

| 1, n (%) | 6 (24.0) | 2 (13.3) | 4 (40.0) | 0.175 |

| 2, n (%) | 16 (64.0) | 10 (66.7) | 6 (60.0) | 0.734 |

| 3, n (%) | 3 (12.0) | 3 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.25 |

| cardiothoracic ratio | 0.54 | 0.58 | 0.48 | <0.001 |

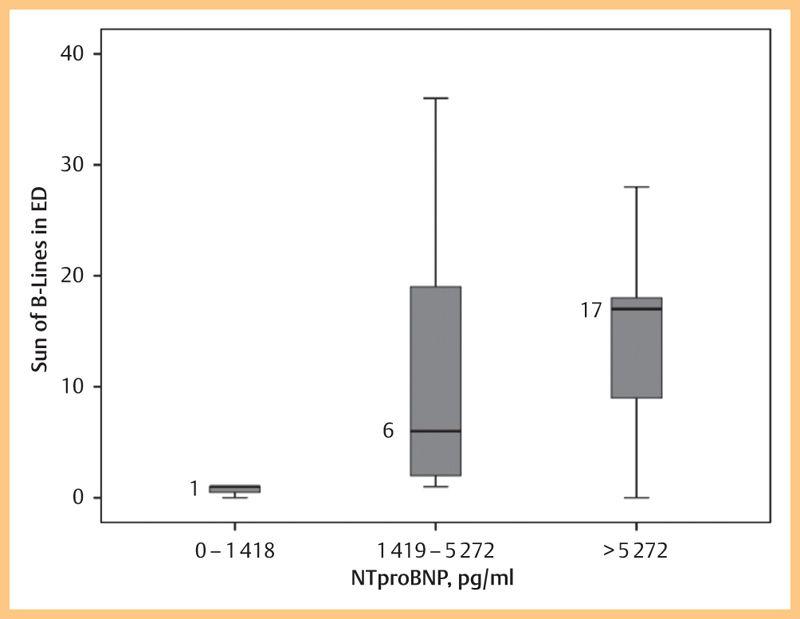

Evaluation of laboratory tests, ECG, transthoracic echocardiography, chest X-ray and LUS are presented in Table 1. The sensitivity for LUS to detect AHF was 40% and the specificity 100% (Positive predictive value: 100%; negative predictive value: 52.6%). Analysis displays an association among the total number of B-lines and NT-proBNP levels in AHF patients (p=0.005, Table 1, Fig. 1). Decline in amount of total B-lines after treatment accompanied decrease in symptoms as assessed by a VAS-dyspnoea scale.

Fig. 1.

Boxplot of B-lines by different NT-proBNP groups in patients with acute dyspnea (n=14 patients in total with available NT-proBNP values). The graph shows a strong association among elevated NT-proBNP levels and the increased number of B-lines.

Discussion

B-line LUS is proposed as a tool used at the point-of-care to support clinical decision making in patients with acute dyspnoea. 4 5 6. In this pilot study, B-line ultrasound in the ED was highly specific, but moderately sensitive to identify patients with AHF.

The major finding of our study corroborates and extends previous findings. 2 or more positive regions with 3 or more B-lines as demonstrated by point-of-care LUS display a very high specificity to support the diagnosis of AHF in ED patients with acute dyspnoea (specificity 75–91%) 7 8. In contrast to previous examinations, diagnostic sensitivity in our trial (40%) is moderate as compared to previous reports (70 –92%) 7 8. It is tempting to speculate that this may be due to the method of final adjudication of AHF diagnosis in respective trials: Final adjudicated diagnosis of AHF in our trial was done by 2 experienced physicians (cardiologist, emergency physician) using all available patient data for adjudication 1 10, while other reports used scores including descriptive methods of pulmonary congestions and/or cardiac decompensation for final diagnosis questioning accuracy of final adjudicated diagnosis 6 8. Of note, some of the enrolled patients were pre-treated by EMS based emergency physicians before being admitted to ED. Use of pre-hospital diuretics may have influenced the presence of B-lines due to their rapid resolution after treatment. Nevertheless, emergency LUS of study subjects was performed within 1 h of presentation to the ED confirming the validity of our findings. Miglioranza found a sensitivity for LUS of 85% in outpatients with a mean age of 53 years 8. Our cohort was older with a median age of 72 years (IQR 60.5–80.5) and contrary to prior ED studies a history of CHF was present in nearly all patients (vs. 75% described by Anderson, 2013) 9.

As demonstrated by our data, radiographic signs show a moderate diagnostic accuracy to detect AHF 11, while NT-proBNP levels display a high diagnostic accuracy for identifying AHF as the cause of acute dyspnoea 12. In addition, it has to be recognized that LUS technique to correctly identify B-lines is not fully standardized. In particular, heterogeneity of equipment (type of probe used, frequency), and individual technique used (how long are the pleural line segments visualized at each spot, type of the probe, pressure applied, scanning sector angle) may influence the diagnostic accuracy of LUS. The conclusions of our findings may also be limited due to the low sample size and bias may have occurred due to the convenience sample of this trial. The strong association among elevated NT-proBNP levels and the increased number of B-Lines (≥ 12) confirmes the validity and strength of our data, which has also been shown by previous reports 13. Adequately powered diagnostic studies are required to confirm the utility of this evaluation strategy.

Conclusion

Lung ultrasound appears to be a helpful screening method for patients with acute dyspnea regarding AHF. LUS is a rapid, timely available and very specific method to support the diagnosis of AHF in patients presenting with acute dyspnoea to the ED. In contrast to circulating natriuretic peptide levels, sensitivity of LUS is intermediate. Therefore a combined strategy of NT-proBNP testing and LUS will lead to fast and reliable results to support the diagnosis of AHF.

References

- 1.Christ M, Laule-Kilian K, Hochholzer W. et al. Gender-specific risk stratification with B-type natriuretic peptide levels in patients with acute dyspnea: insights from the B-type natriuretic peptide for acute shortness of breath evaluation study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1808–1812. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McMurray J J Adamopoulos S Anker S D et al. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC Eur Heart J 2012331787–1847.Erratum in: Eur Heart J 2013; 34: 158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nieminen M S, Böhm M, Cowie M R. et al. Executive summary of the guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of acute heart failure: the Task Force on Acute Heart Failure of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:384–416. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Volpicelli G, Elbarbary M, Blaivas M. et al. International evidence-based recommendations for point-of-care lung ultrasound. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:577–591. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2513-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lichtenstein D A, Mezière G A. Relevance of lung ultrasound in the diagnosis of acute respiratory failure: the BLUE protocol. Chest. 2008;134:117–125. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neskovic A N, Hagendorff A, Lancellotti P. et al. Emergency echocardiography: the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging recommendations. European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;14:1–11. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jes193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bitar Z, Maadarani O, Almerri K. Sonographic chest B-lines anticipate elevated B-type natriuretic peptide level, irrespective of ejection fraction. Ann Intensive Care. 2015;5:56. doi: 10.1186/s13613-015-0100-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miglioranza M H, Gargani L, Sant’Anna R T. et al. Lung ultrasound for the evaluation of pulmonary congestion in outpatients: a comparison with clinical assessment, natriuretic peptides, and echocardiography. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:1141–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson K L, Jenq K Y, Fields J M. et al. Point-of-care ultrasound diagnoses acute decompensated heart failure in the ED regardless of examination findings. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32:385–388. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2013.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bahrmann P, Christ M, Hofner B, Bahrmann A, Achenbach S, Sieber C C, Bertsch T. Prognostic value of different biomarkers for cardiovascular death in unselected older patients in the emergency department. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2015;19 doi: 10.1177/2048872615612455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Studler U, Kretzschmar M, Christ M, Breidthardt T, Noveanu M, Schoetzau A, Perruchoud A P, Steinbrich W, Mueller C. Accuracy of chest radiographs in the emergency diagnosis of heart failure. Eur Radiol. 2008;18:1644–1652. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-0930-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mueller C, Scholer A, Laule-Kilian K. et al. Use of B-type natriuretic peptide in the evaluation and management of acute dyspnea. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:647–654. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gargani L, Frassi F, Soldati G. et al. Ultrasound lung comets for the differential diagnosis of acute cardiogenic dyspnoea: a comparison with natriuretic peptides. Eur J Heart Fail. 2008;10:70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]