Abstract

Objective

Develop and test measures of risk of deportation and mixed-status families on WIC uptake. Mixed-status is a situation in which some family members are U.S. citizens and other family members are in the U.S. without proper authorization.

Methods

Estimate a series of logistic regressions to estimate WIC uptake by merging data from Fragile Families and Child Well-being Survey with deportation data from U.S.-Immigration Customs and Enforcement.

Results

The findings of this study suggest that risk of deportation is negatively associated with WIC uptake and among mixed-status families; Mexican origin families are the most sensitive when it comes to deportations and program use.

Conclusion

Our analysis provides a typology and framework to study mixed-status families and evaluate their usage of social services by including an innovative measure of risk of deportation.

INTRODUCTION

Government policies concerning unauthorized immigrants are among the mostly hotly debated topics in the United States. Opponents of generous government policies towards unauthorized migrants point to fiscal burdens, border security, cultural-linguistic barriers and respect for the law of the land. Proponents of more generous or lenient policies, on the other hand, argue for expansion of the labor supply, human rights, and family reunification. Caught in the middle of these opposing perspectives are a sizable number of mixed-status families in which some, but not all, members of the family are U.S. citizens by birthright or naturalization while other members are in the country without proper legal authorization.

According to the Pew Hispanic Center, of the 4.3 million babies born in the U.S. in 2008, eight percent or 340,000 of these children were born into mixed-status families (Passel, 2010). One explanation for this increase is an indirect consequence of immigration enforcement. For example, as the cost of unauthorized travel between Mexico and the U.S. has increased, this has indirectly caused undocumented workers to remain in the U.S. longer and ultimately increases their chances of having a child born in the U.S.

Aside from sheer numbers, the need to study mixed-status families and their use of U.S. social services is important for several reasons. First, from a civil liberties perspective, mixed-status families are voiceless and a vulnerable population in our society. While, unauthorized parents live in the “shadows” of our society, the children do have standing (in a traditional cost- benefit analysis framework) and are protected under the 14th Amendment. “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside…””

Second, children in mixed-status families are at-risk and precisely the types of clients targeted by many social services focused on reducing poverty. Research on children of immigrants from Mexico and Central America documents that these children are particularly disadvantaged, relative to both other immigrant children and native-born white children, on measures of poverty, social economic status, parental employment, and parental education (Hernandez, Denton, & McCarntey, in press). Third, social exclusion (i.e. lack of access to a state identification card, bank accounts, and social services) has been strongly linked to low levels of cognitive ability for children in mixed-status households (Yoshikawa, Godfrey, and Rivera, 2008). To the extent that these young people remain in the U.S., public policies can serve to either enhance or diminish their eventual contributions to the U.S. economy.

In short, this is the first study to examine risk of deportation on federally funded social program take-up rates among mixed-status families in the Personal Responsibility Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA) environment. Lack of research in this area has been mostly attributed to the fact that it is difficult to identify and collect data on undocumented immigrants and even if the data were available, this population is restricted from participating in most federal programs. Because WIC provides services to mixed-status families, WIC provides an exception to the general exclusion of services to this population and allows us to assess take-up rates as well as isolate the effect risk of deportation on willingness to apply for benefits. In this research, we use the Census Bureau’s methodology to impute an individual’s status as documented or undocumented. We then apply this methodology in the Fragile Families dataset as this nationally representative dataset focuses on low-income, vulnerable households in which mixed-status families are likely to be over-represented. Additionally, the Fragile Families sampling strategy required that the focal child in the survey be born in the U.S. – making them eligible for all social services provided that they meet program eligibility requirements.

Because mixed-status families are somewhat unique relative to most social service recipients, we expand the typical take-up model to consider two key variables of interest that are particularly relevant to this population: anti-immigrant legislation which can contribute to a “chilling” environment for undocumented workers as well as the risk of deportation. For the former variable, we coded state legislation and legislative attempts for anti-immigrant content and for the latter variable we submitted a Freedom of Information Act request to Homeland Security to secure the necessary information to compute deportation risks, although this information has subsequently been made available online.

We fully recognize that there is likely to be considerable confusion about WIC eligibility among immigrants and mixed-status families. The immigrant population is diverse as it encompasses lawful permanent residents, refugees, victims of human trafficking and their “derivative beneficiaries” as well as up to 8 million immigrants who could be eligible for federal Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and President’s Obama’s new 2014 Executive Order Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents (DAPA). Additionally, the federal government allows states the discretion to expand eligibility for some social programs, at state expense. Hence, there is considerable cross-state variability in eligibility. This complex environment has also led to confusion among some program administrators and operators who have mistakenly turned away some eligible immigrants from services (Broder and Blazer, 2011). The value-laden and politically charged debates have confused many non-Hispanic Americans, thirty percent of whom mistakenly believe that the majority of Latinos in the U.S. are undocumented (NHMC, 2012). Our models of WIC take-up reflect this current political and policy environment, not a simpler environment of across-the-board inclusion or exclusion.

BACKGROUND

The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA) was the first real attempt to restrict benefits to immigrants, radically altering the policy environment for services. Under the PRWORA (P.L. 104-193) and subsequent laws,1 eligibility restrictions were enacted to restrict certain programs to legal immigrants and deny access by unauthorized migrants to most federally funded government programs.

In general, PRWORA established an official distinction between ‘qualified ‘and ‘unqualified’ aliens. Qualified aliens are those who have legal permanent residency and/or refugee status. Unqualified aliens are unauthorized migrants who are residing in the U.S. without proper documentation. While qualified aliens are eligible for some federal benefits, unqualified immigrants are denied most federal benefits including, among others, Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF), Medicare, Medicaid, state Child Health Insurance Programs (CHIP), Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly Food Stamps).

In the post-PRWORA era, some eligibility criteria have been expanded to again include unauthorized immigrants. For example, benefits have been reinstated for emergency medical treatment (under the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act of 1986) which includes testing and treatment of communicable diseases. Other benefits that have been reinstated since PRWORA include short-term, non-cash, and in-kind emergency disaster relief such as food and short-term housing. Unauthorized migrants have always been eligible for many community programs and services such as drug rehabilitation, education, HIV/AIDS testing and counseling for AIDS/HIV.

Moreover, K-12 education has always been available to unauthorized migrants although this was contested unsuccessfully in Texas (Plyer vs. Doe, 1982). Additionally, unauthorized children have been able to take advantage of the federally subsidized school lunch and breakfast programs. Other nutritional assistance programs which unauthorized migrants can access include the Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP), Summer Food Service Program, Special Milk Program, and WIC. While it is up to state discretion to provide WIC to unauthorized migrants, all states have consistently provided WIC to this population.

Although clearly written in law, in practice, there is great confusion about what state level benefits are available to both qualified and unqualified immigrants. The fact that the programmatic restrictions can vary from state to state adds to confusion over eligibility for benefits on the part of unauthorized immigrants. This confusion may explain part of the disparity between program availability and program take-up that has been well documented even among documented immigrants (Blau, 1984; Borjas & Trejo, 1991; Borjas & Hilton, 1996; Hu, 1998; Van Hook & Bean, 1998). This paper departs from this earlier stream of research by looking at the effects of other policy levers (deportation risk and anti-immigrant legislative attempts) on the take-up rates of WIC among mixed status families.

Women, Infants and Childrens (WIC) Program and Predictors of Program Use

WIC was first created as a two year pilot program in 1972 by an amendment to the Child Nutrition Act of 1966 and was made permanent in 1975. WIC’s mission is to safeguard the health of low-income women, infants, and children who are at risk for poor nutrition. WIC is currently the third largest federally funded food program behind SNAP and the Free School Breakfast and Lunch Programs and is one of the central components of our nation’s food assistance system. As of 2010, WIC enrolled 9.1 million participants of the eligible 14.1 million individuals (USDA Report No. WIC-13-ELIG, 2013). WIC participation has been increasing throughout its history with the exception of a modest decline between 1998 and 2001 and reached up to 9,175,000 Americans (USDA, 2011).

WIC is administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Food and Nutrition Service (FNS). To be eligible for WIC you must be a pregnant or postpartum woman, an infant or a child up to the age of five. Additionally, individuals must be either income eligible, at or below 185 percent of the federal poverty level, or adjunctively eligible through participation in other programs such as SNAP, Medicaid or TANF. Finally, individuals must be identified as “nutritionally at- risk” based on a medical or nutritional assessment by a staff physician, nutritionist or nurse at the local WIC office. Because of our focus on Latino mixed-status families, we additionally note that Latinos make up a substantial percentage of those participating in WIC. In 2009, just under half (45 percent) of WIC participants were of Hispanic origin (USDA Report no. CN-10-NSWP2-R2, 2012).

The likely benefits of WIC participation have been hotly debated. There is a stream of research that supports the notion that “WIC Works.” WIC participation during pregnancy has been associated with higher birth weights, fewer fetal deaths (Kotelchuck, M., et al., 1984; Kennedy, 1982; Rush, 1986; Buescher et al, 1993; Bitler and Currie, 2005) lower maternal and newborn health care costs (Schramm, 1985, 1986; Devaney et al, 1992; GAO, 1992) and negatively associated with breastfeeding (Schwartz et al, 1995; Chatterji and Brooks-Gunn (2004); Ziol-Guest and Hernandez, 2010).

The beneficial effects of WIC have been contested, however. In the “Does WIC Work” debate, Joyce et al. (2005) argue that beneficial effects of WIC identified by Bitler and Currie (2005) and other researchers resulted from the use of inappropriate measures of the key outcome variables. Once corrected, Joyce et al. (2005) argue that “WIC Doesn’t Work.” Ludwig and Miller (2005) weighed-in on this debate and ultimately determined that in fact “WIC Works.”

While WIC efficacy is important policy issue, our focus is elsewhere. Instead we investigate whether or not government actions and policies are imposing additional barriers to WIC participation for the large and growing number of mixed status families. There is a small but solid literature on the determinants of WIC uptake within the eligible population. The general premise is that the decision to enroll in WIC involves a comparison of the benefits and costs of participation, the availability of WIC clinics, and access to other welfare programs.

Neither the WIC application process nor WIC participation is costless. Factors that affect the magnitudes of the benefits and costs include state-level policy levers, state required income verification (Brien and Swann, 2001), as well as the characteristics of eligible participants. At the individual level, women who derive the greatest benefits from WIC should be more willing to bear the costs of program participation (Ludwig and Miller, 2005). WIC participants tend to be more informed, motivated, and entrepreneurial (Devaney, Hilheimer, & Shore, 1992). Particularly among Hispanics, married mothers are more likely to participate in WIC (Bitler, Currie & Scholz, 2003) relative to unwed Hispanic mothers. Research on WIC has also focused on the timing of enrollment. Ku (1989), for example, finds that early prenatal enrollment is associated with previous participation in WIC. Regarding race and ethnicity, studies show that there are statistical differences of WIC participation. In general, Black and Hispanic women and their children were more likely to participate in WIC than there non-Hispanic white counterparts (Bitler, et al., 2003; Castner et al., 2009; Swann, 2003; Tiehen & Jacknowitz, 2008).

Regarding immigration and WIC participation, there is a small literature on the individual characteristics of immigrants and WIC uptake, yet few studies have tested the role of citizenship. The general findings indicate that among all immigrants, those who lack access to child care and transportation and who feel a greater stigma from receiving a “hand-out” are less likely to enroll in WIC (Kahler et al., 1992). In comparing, WIC uptake across immigrant and native born mothers, Fomby and Cherlin (2004) find that children of noncitizens participate at higher rates and have longer duration than native-born children but there are no differences between native-born parents and naturalized citizens. This finding is further confirmed by Fortuny (2010) who show that there are no significant differences in WIC participation between naturalized U.S. citizens and native-born mothers. In several respects, immigrant women who use WIC are similar to native born mothers. These mothers are more likely to be racial minorities, unmarried, younger, less educated, and low-income (Bitler, et al., 2003; Castner et al., 2009; Swann, 2003; Tiehen & Jacknowitz, 2008). At the state-level, WIC participation rates are lower in states where less information about program eligibility is available (Kahler et al, 1992), and also lower in states that impose higher transaction costs for applying (e.g., no adjunctive eligibility, income verification) (Currie, 2004). Participation is also lower in states that have less WIC clinics (Bitler, Currie & Scholz, 2003) and states that have higher unemployment and poverty rates.

There is some older research that predates PRWORA that relates to the impact of state policy levers and the labeling of a “public charge” on social service participation. In other words, there was rumor that was circulated that if you were labeled a “public charge” on official state documents, you were then ineligible to become a permanent resident, indirectly deterring vulnerable immigrants from using services. Remember that in the pre-PRWORA era, immigrants were eligible for far more government services. Nonetheless, the extent to which policy makers wanted to make social services available to immigrants, including those who entered the country legally, was still hotly debated. As part of this debate, there were legal briefs and academic studies that addressed the impacts of being labeled a “public charge” on social service participation (Johnson, 1995; Schlosberg and Wiley, 1998; Park, 2000; Fix and Haskins, 2002). More recent policy work by Perreira et al. (2012) further discuss the impact of being labeled a “public charge” has had on the use of social services. While “public charge” has been in immigration law for more than 100 years, it was not until the mid-1980’s and early 1990’s that this highly salient issue overshadowed the conversation leading up to PRWORA, inadvertently causing a chilling effect for needy immigrants, many of whom were legally eligible to access social services. It is in this environment that Blau (1984), Borjas and Trejo (1991, 1993) and Borjas and Hilton (1996) examined uptake of AFDC among immigrants. These authors found that ceteris paribus, immigrants were less likely than native born citizens to use AFDC. While initial take-up rates were low in the immigrant population, they increased over time, possibly as the immigrants became increasingly assimilated. Alternatively, the low initial take-up rates may have resulted from the chilling environment from legal initiatives such as Proposition 187 (Asch et al., 1994; Fenton et al.,1997; Berk & Schur, 2001). While this work focuses on AFDC, not WIC, and is pre-PRWORA, the notion of a chilling environment as a result on anti-immigrant legislation and legislative bills is still relevant today.

Risk of deportation as it affects the uptake of social services among undocumented immigrants has received relatively little attention in the literature. What we know so far is that unauthorized immigrants who report high levels of fear (of deportation) are more likely to report an inability to acquire medical and dental care (Berk & Schur, 2001). Asch, Leake & Gelberg (1994) also report that undocumented immigrants feared going to physicians because they thought that it could lead to trouble with immigration authorities. These undocumented immigrants were almost four times as likely to delay seeking care for more than two months compared to their citizen counterparts. While, both of these papers are qualitative and never quantified fear or risk of deportation, these published pieces are the foundation of our theoretical framework and guide our theory on the relationship between risk of deportation and WIC uptake among mixed status families in the post-PRWORA environment.

Anti-Immigrant Climate

While social work research has concentrated on understanding psychological phenomenal like stigma, we argue that risk of deportation is an additional indicator that is driving the differences between take-up rates and WIC participation for mixed-status families. Fear and risk of deportation can take various forms. One of the most salient signals of anti-immigrant backlash are the proposed English only laws spread across the states starting in the 1980’s. While the majority of the legislative actions were defeated in states with substantial language minority populations, conservative states and states with mechanisms for direct democracy generally adopted such laws (Citrin et al. 1990; Preuhs, 2005; Tataloch, 1995). Work by Preuhs (2005) and Tatalovich (1995) estimate that of the 50 states, around half have now adopted Official English laws. Arguably adoption of this law is closely tied to resentment toward racial/ethnic minorities particularly the foreign born (Schildkraut, 2001). Other anti-immigrant bans that have negatively affected undocumented families are laws banning the issuance of driver’s licenses, laws banning day laborers sites, and measures which require proof of citizenship to rent or lease an apartment.

While in general deportations have declined since 2001, the recent forms of anti-immigrant backlash at the local level have been exacerbated by the widespread deportations by Immigrant Customs and Enforcement (ICE) at place of employment. For example, the Department of Homeland Security estimates that under the Obama administration around 395,000 undocumented immigrants were deported in 2009 (DHS, 2010). As expected this heighted enforcement has negatively affected the Latino/a community. A poll conducted by the Pew Hispanic Center (2007) shows over half of Latinos worry they, a family member, or close friend can be deported. Moreover, 67 percent of the foreign born respondents in this same poll feel that they are negatively affected by the increased enforcement and attention to illegal immigration. Moreover, since the enactment of Section 287(g) of the Immigration and Nationality Act2, which legalizes the deputation of local law officials to act as federal immigration law enforcers, deportations have been more visible in the undocumented community. As of 2011, there are agreements with 69 law enforcement agencies in 24 states that have enacted 287(g).

The effects of work site raids and the enactment of 287(g) has forced undocumented immigrants further into the shadows despite the general trends in deportation after 2001. In general, deportations began to rise after World War II and during the Korean War. Starting in the early 1960’s we witnessed an increase in deportations up to a peak in the mid-80s. It was this period in which amnesty was passed under 1986’s Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA). After a few years after IRCA, the trend continued to steadily rise in the early 1990’s reaching a 1,889,000 deportations in 2000 (DHS Yearbook, 2010).

After 2001, deportations began to drop, as the nation’s attention focused to the war on terrorism both in the invasion of Afghanistan 2001 and in Iraq 2003. This trend however reversed dramatically during the Obama’s administration as he over-turned President George W. Bush halt on worksite raids and the implementation of the Secure Communities Program3. It is now estimated that under Obama’s first administration we have deported over 1,000,000 immigrants, which is more deportations then in George W. Bush’s eight years in office.

In addition to federal action, states have been active in passing anti-immigrant legislations which make it unlawful to be in the state without proper documentation. For example, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Arizona, and Alabama have all passed anti-immigrant legislation which is forcing the undocumented to either flee or go further underground. In sum, while the number of deported aliens reached an all-time high in 2009 the presence of local foot soldiers has caused an increased climate of fear and risk of deportation amongst undocumented immigrants living in the interior.

While, there are undocumented immigrants from every corner of the world, deportations naturally affect Mexican immigrants disproportionally. In 2005 for example, around 88 percent of the 791,568 immigrants deported from the U.S. were from Mexico. This of course is largely a function of the flow of undocumented aliens from Mexico and our historical relationship with our southern neighbor. What is not clear is of those deported, how many of these unauthorized migrants have children who are American citizens. Thus far, the Urban Institute has produced the only study that has focused on the outcomes of immigration raids. The study found that of the 900 unauthorized immigrants detained in 2007 worksite raids, over 500 children were affected (Urban Institute, 2007). As noted by the study the majority of these children were in fact U.S. citizens.

What has yet to be tested is how risk of deportation affects the likelihood of a mixed-status mother’s use social services? One can argue that as the anti-immigrant sentiment increases this then can lead a mixed-status mother to decide not to participate in a government program in which her child is eligible to receive. In sum, this is the first empirical analysis to first disaggregate mixed-status mothers and quantify risk of deportation on the probability of social service take-up in mixed-status families.

METHODOLOGY

The main question in this study is how risk of deportation (Γ) in mixed-status (Μ) families affects the probability of WIC uptake? To test this question, we will estimate a series of logistic regressions with data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study. The final model is as follows4:

Where: M=Family Categories; φ = Legislative Threat; Γ= Risk of Deportation; X=Vector of mother-specific characteristics (Age, Education, Marriage Status, Number of Children, Experience with Economic Hardship, Employment, State-Fixed Effects) as well as contextual variables (percent of household on public assistance, percent of families under the poverty line).

Due to the fact that the outcome variable is binary, we will be estimating this logistic equation with a maximum likelihood estimator (MLE). Findings will be presented using logit coefficients and factor change in odds ratios. Because this survey is used to represent the U.S. nationally, weights are applied in all estimations to correct for biased standard errors, and all statistical analysis was conducted using Stata 11 software.

DATA

Studying undocumented families and program use is a challenge especially when further collapsing families into mixed-status subcategories by nationality, race and ethnicity. To model a mixed-status family one family member has to be a U.S. citizen and at least one parent should be undocumented. In order to fulfill data requirements, we make use of the survey sampling strategy of the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Survey (FFCWB). The Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study is a national longitudinal sample of all U.S. cities with 200,000 or more inhabitants between 1998 and 2000. Data have been collected on 4,898 births in 75 hospitals in 20 cities across the United States. The study then follows a cohort of parents and their children from child’s birth, 12th month, 30th month, 48th month and when the child is nine years old (currently in the field). This analysis uses the nationally representative weights to be able to generalize about the well-being of families living in fragile families.

The Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study are of particular importance for this study because of their scope and national representativeness. In addition, the Fragile Families by design includes only families who have a child born in the U.S., granting the child citizenship by birthright. The study has a representative number of mixed-status families who are sampled across time on various indicators of social service participation, earnings, and physical/mental health. Moreover, the contract data has geographic indicators which permit merging external data sources to the geographic location of the mother. The first two waves of the Fragile Families survey are utilized which were administered in 1998–2001.

External sources of data (deportation data from Special Agent in Charge Districts of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security5, undocumented population estimates from the Pew Hispanic Center, and legislative data from the Migration Policy Institute) are merged using the geo-coded indicators within Fragile Families and Child Survey. For example, if living in Indianapolis, you are under the enforcement jurisdiction of the Chicago, IL SAC district. Matching Fragile Family sites and Special Agent in Charge districts are as followed: Oakland-San Francisco, Austin-San Antonio, Baltimore-Baltimore, Detroit-Detroit, Newark-Newark, Philadelphia-Philadelphia, Richmond-Washington DC, Corpus Christi-Houston, Indianapolis-Chicago, Milwaukee-Chicago, New York-New York, San Jose-San Francisco, Boston-Boston, Nashville-New Orleans, Chicago-Chicago, Jacksonville-Tampa, Toledo-Detroit, San Antonio-San Antonio, Pittsburgh-Philadelphia, Norfolk-Washington DC.

MEASURES

Family Categories

Mixed-status mothers in this study are defined as mothers who are undocumented and who have a child who is American by birthright. Families were separated by race and ethnicity and citizenship status. For example, families were collapsed into U.S. born non-Hispanic Whites (reference group), U.S. born non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic Black naturalized, non-Hispanic Black mixed status, U.S. born Hispanic, Hispanic naturalized, Mexican-Hispanic mixed-status, and non-Mexican Hispanic mixed-status family.

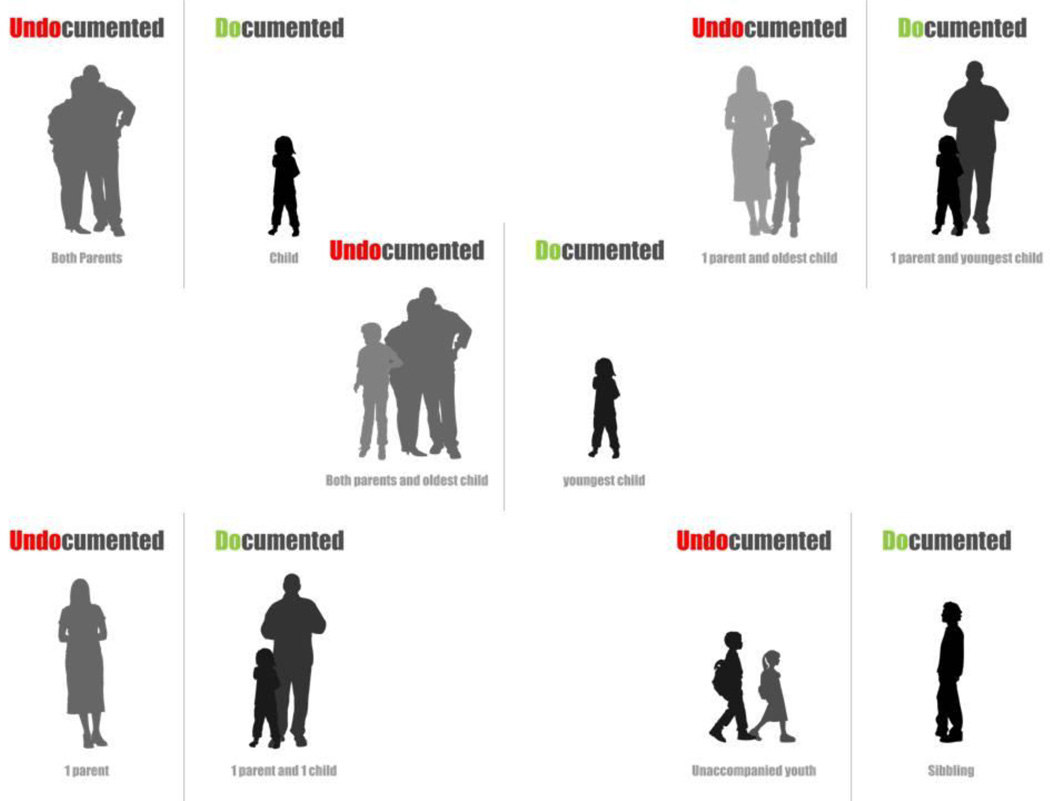

Up to this point there is no prior research on how to code mixed-status. Using qualitative interviews and focus groups, a typology was constructed and depicts the complexities of mixed-status families which are shown in Exhibit 1. Qualitative interviews suggest that mixed-status families are a function of residency in the U.S., and the demographic profile of an individual. In general, the family in the upper right hand corner of Exhibit 1, is representative of families who have come to the U.S. relatively young and have been in the U.S. long enough to form a family. The family in the center tends to be older and has already established a family in Mexico prior to immigrating to the U.S.

Exhibit 1.

Typology of Mixed-Status Families

To be coded as mixed-status in the FFCWB dataset you have to self-identify as being foreign born and non-citizen. If satisfying the above criteria you were coded as mixed-status. If, mothers were not asked the citizen question (two cities were skipped) and said they were foreign born they were coded as being citizens if they arrived pre-1986 and presumed to be non-citizens after 1986. Moreover, because the FFCWB design surveys mothers who have given birth in a U.S. hospital this automatically makes them eligible to be classified as mixed-status.

Risk of Deportation

Risk of deportation is measured as the proportion of deported aliens divided by the number of estimated unauthorized immigrants6. For example, we would expect that the risk of being deported in Texas is different than the risk of being deported in North Carolina. Deportation data are gathered from the Department of Homelands Security- Immigration Statistics office. The data are then classified by the 26 Special Agents in Charge Jurisdictions, who are responsible for enforcing specific jurisdictions within the nation’s interior. The 26 SAC offices maintain various subordinate field offices throughout their areas of responsibility, and produce statistics on deportations across time.

Risk is constructed by taking the proportion of deportations which is at the SAC district by the estimated undocumented population which is measured at the state level. In some states, there are multiple SAC districts that can be in the same state such as in Florida and New York. Furthermore, SAC jurisdictions can have multiple offices in a state have their jurisdictions reach across state boundaries.

Risk of deportation is constructed by taking the total number of deportations in the SAC district and multiplying it by the proportion of the total population of a given state by the total population of the states within the SAC region. The formula is as such:

For example, to calculate the total number of deportation in Indiana, you would take the total deported in the Chicago SAC (Indianapolis is the Chicago SAC district jurisdiction) district (n=6,493). Multiply this figure by the proportion of the total population in Indiana in 2000 (n=6,091,392) divided by the sum of the populations of each state in the Chicago SAC district (Σ(IN, KY, IL, WI, MO, KS)=36,250,793) which is (((6,091,392/36,250,793)= (0.1680)*(6,493))=1,091 deported aliens in the Hoosier State in 2000. After deriving this number you then divide by the number of estimated undocumented immigrants in that state (IN=65,000), which provides, an estimate of the risk of being deported in the state of Indiana in 2000. In this case the risk of being deported in Indiana is (1,091/65,000) =1.67 percent. This formula then allows us to estimate deportations at the state level and also take into account the areas of responsibility for each SAC district.

Deportations however are not uniform across nationalities, for example in 2000, 0.961 percent of all deportees were from Mexico, Central and South Americans made up 0.004 percent of deportees and the remaining 0.035 percent were from non-Latino America countries. To take this enforcement differences into account, we then applied weights of 0.961 for Mexican mixed-status mothers, 0.004 for Non-Mexican Hispanics mixed-status mothers and 0.035 for all other No-Hispanic mixed-status families. We can also assume U.S. born mothers and naturalized citizens do not have a risk deportation and are assigned a value of 0.

Legislative Threat

Legislative threat is the sum of anti-immigrant legislation passed, rejected, or expired across 50 states. The type of anti-immigrant legislations vary from education, public benefits, law enforcement, employment, and a category for other (this includes: family law, housing, English as an official language, etc.). The data on anti-immigrant legislation comes from a methodology7 created by the Migration Policy Institute (MPI). This methodology uses the StateNet database within LexisNexis and Westlaw to locate all state legislation that has somehow regulated immigration. As one would expect many bills were companion bills or were substantially similar to other bills introduced under different numbers in one or both houses of the legislature, each of these bills will be counted separately. Do to the fact that some bills expand immigrant rights, these bills are subtracted out to insure we are just focusing on anti-immigrant bills. While, this measure is imperfect, it does capture a negative sentiment in a geographic space. Moreover, because some laws are extreme and will never pass, we argue that including all laws (not just adopted laws) provides a more robust measure of the potential threat of anti-immigrant legislation. To control for variation in the effects of legislative threat for mixed-status mothers we take the total deportations in a given year and divide by the country of origin of the deportee. Using the same weighting scheme as in the risk of deportation that takes into account the differences in deportation by country we also use this metric for legislative threat. We also assume U.S. families are not affected by legislative threats and are assigned a value of 0.

Economic Hardship FFCWB

After testing several specifications of income and maternal well-being, this analysis uses a non-traditional approach to measure poverty. Since this study is on a population that by law is not authorized to be in the formal labor market, specifying a relative measure of economic hardship gives a better indicator of the level of economic hardship a family might be facing. Several studies indicate that maternal wellbeing is a better indicator than income, (Mayer and Jencks, 1989; Beverly, 2001; Teitler et. al, 2004; Sullivan, Turner, Danziger, 2008;, Heflin, 2009). Moreover, qualitative data regarding parent’s household income show that in general mixed-status families tend to work off the books, or use falsified documents to obtain employment. To overcome this, we constructed a measure of economic hardship. This construct is a sum of twelve indicators ranging from help with food, hunger, if the mother has had to use a homeless shelter, trouble paying bills, etc.

Additional Control Variables

In addition to family categories, risk of deportation, and legislative threat, additional control variables are included to estimate WIC participation, which are consistent with the literature. For example, education is specified with two binary variables (0=High School and above, 1=Less than High School). A binary indicator of marital status (1=married, 0=unmarried) is included to understand differences in WIC uptake by marital status as well as a binary variable on employment status (0=unemployed, 1=employed). We also include a measure of the number of children in the household and age of mother. Research indicates that older married couples are less likely to use WIC than younger single parent families and the number of additional children to be positively associated with WIC take-up (Chatterji et al., 2002). In addition, state-fixed effect dummies are included to control for the clustering of respondents within hospitals as well as contextual variables such as percent of household on public assistance and the percent of families under the poverty line.

Outcome Variable

The WIC indicator is a dichotomous measure if the mother is using the program (1=yes, 0=no). This question is only asked in the twelve month survey (second wave) of FFCWB. “Since (CHILD) was born, have you received help from any of the following agencies….or programs? WIC (Woman, Infant, and Child Program) being of the questions on the list.

Table 1, provides an overview of the key demographic family groups used in this analysis. Immigration status is broken into three categories: U.S. born citizen, naturalized citizens8 and non-citizens (mixed-status families). Race/ethnicity/nationality is broken down into the following categories: non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic non-White, Pan ethnic Hispanic, Hispanic of Mexican origin and Hispanics non Mexican ancestry. Mixed-status families represent about 11.6 percent (567/4,884) of families in the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Survey (Mexican origin representing over half). This is 2.5 percentage points above the national estimate (9 percent) taken from the 1998 Current Population Survey (Fix & Zimmerman, 1999; Passel and Clark, 1998).

Table 1.

Key Demographic Groups in Fragile Families

| Non- Hispanic White |

Non- Hispanic Non-White |

Hispanic | Hispanic: Mexican National |

Hispanic: Non Mexican National |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. Born Citizen | 1,024 | 2,283 | 790 | -- | -- |

| Naturalized Citizena | -- | 116 | 104 | -- | -- |

| Non-Citizen | -- | 120 | -- | 315 | 132 |

Note(s):

When citizenship status is missing (N=223), mothers who migrated to the U.S. prior to 1986 are categorized as naturalized citizens. Those migrating during or after 1986 are classified as non-citizens.

Table 2 provides a detailed tabulation of the summary statistics used in the analysis. In general, the FFCWB sample tends to be black (46 percent), relatively young (25 years old), and participating in WIC at high rates (70 percent). In general, over 30 percent of mothers had less than a high school education yet mothers also tended to be either be part-time or half-time employed. Fragile Family mothers in this sample also had low marriage and cohabiting rates and have at minimum two other biological children.

Table 2.

Summary Statistics for Analysis using Fragile Families Child Wellbeing Survey (n=2,764)

| Variables | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WIC | 0.728 | -- | 0 | 1 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 0.21 | -- | 0 | 1 |

| Other: U.S. Born Citizen | 0.467 | -- | 0 | 1 |

| Other: Naturalized Citizen | 0.024 | -- | 0 | 1 |

| Other: Mixed-Status | 0.025 | -- | 0 | 1 |

| Hispanic: U.S. Born Citizen | 0.162 | -- | 0 | 1 |

| Hispanic: Naturalized Citizen | 0.021 | -- | 0 | 1 |

| Hispanic: Non Mexican Mixed-Status | 0.027 | -- | 0 | 1 |

| Hispanic: Mexican Mixed-Status | 0.064 | -- | 0 | 1 |

| Age | 25.28 | 6.047 | 15 | 43 |

| Less than High School | 0.348 | -- | 0 | 1 |

| Married or Cohabitating | 0.242 | -- | 0 | 1 |

| Number of Children | 2.159 | 1.325 | 1 | 16 |

| Economic Hardship | 2.342 | 3.729 | 0 | 12 |

| Employed | 0.774 | -- | 0 | 1 |

| Risk of Deportation (percent) | 0.094 | 0.37 | 0 | 3.13 |

| Legislative Threat | 2.69 | 12.295 | 0 | 90.33 |

| Pct. of HH on Public Assistance | 0.081 | 0.072 | 0 | 1 |

| Pct. of Families Below Poverty Level | 0.191 | 0.139 | 0 | 1 |

The fact that FFCWB is a national representative sample of poor, single, families, explains the low marriage rates, WIC use, and low educational attainment.

RESULTS

The analysis uses a nationally representative sample to test the relationship between risks of deportation on the probability of WIC use. The first step in this analysis is to run a baseline logistical regression to estimate WIC participation (model 1). Model 1 provides a benchmark to examine WIC take-up differences between family categories controlling for age, education, marital status, number of children, economic hardship, employment, and contextual control variables (percent of households on public assistance and percent of families below poverty level). We then re-estimate model 1 and include risk of deportation and legislative threat to examine the probability of WIC take-up (model 2). We include logit coefficients and a column for odds ratios for a unit change (factor change in odds) of the independent variables.

From model 1 (table 3), all families (except non-Hispanic naturalized mothers) participated in WIC at higher rates than U.S. white mothers our reference category. This is particularly true for Hispanic mixed-status families and Hispanic naturalized families. In fact, the odds are 40.8 times larger, that a Hispanic mixed-status family of Mexican origin as opposed to U.S. born white mothers will participate in WIC, holding all else constant, which is significant at the 0.001 level. The odds of WIC participation for Hispanic naturalized mothers (24.8) and Hispanic non-Mexican mixed status families (12.32) are also higher compared to U.S. white mothers.

Table 3.

Logistic Coefficients for Regression of WIC Take-up using Fragile Families Child Wellbeing Survey (n=2,764).

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | β | Odds Ratios | β | Odds Ratios |

| Reference Category: White non-Hispanic | ||||

| Hispanic: U.S. Born | 1.150*** | 3.159*** | 1.142*** | 3.133*** |

| Hispanic: Mexican Mixed-Status |

3.709*** | 40.818*** | 5.723** | 305.901** |

| Hispanic: Non- Mexican Mixed- Status |

2.511*** | 12.321*** | 2.568*** | 13.045*** |

| Hispanic: Naturalized | 3.212*** | 24.831*** | 3.226*** | 25.181*** |

| Other: U.S. Born | 1.398*** | 4.049*** | 1.431*** | 4.182*** |

| Other: Mixed Status | 1.534*** | 4.638*** | 1.540*** | 4.665*** |

| Other: Naturalized | −0.14 | 0.869 | −0.14 | 0.869 |

| Age | −0.129*** | 0.879*** | −0.131*** | 0.877*** |

| Education: Less HS | −0.172 | 0.842 | −0.214 | 0.808 |

| Married | −1.340*** | 0.262*** | −1.355*** | 0.258*** |

| Number of Children | 0.282** | 1.326** | 0.274** | 1.315** |

| Hardship | 0.405*** | 1.499*** | 0.392*** | 1.481*** |

| Employed | −0.233 | 0.792 | −0.218 | 0.804 |

| Percent of HH on Public Assistance |

−0.413 | 0.662 | −0.429 | 0.651 |

| Percent of Families Below Poverty Level |

1.648 | 5.194 | 1.667 | 5.294 |

| Legislative Threat | --- | --- | 0.059 | 1.061 |

| Risk of Deportation | --- | --- | −3.645* | 0.026* |

Notes:

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.1,

β is a logit coefficient

Our findings are in line with the WIC uptake literature in that age, marital status, and additional children in the household are negatively associated with WIC participation. In our sample, as a mother gets one year older, the odds of participating in WIC decreased by 12 percent, holding all other variables constant. If the mother was married, the odds of participating in WIC decreased by 74 percent, holding all else constant. The effects of economic hardship on WIC participation was as expected, so as mother’s faced more hardship, she was more likely to participate in WIC which is statistically significant. The result for education on WIC participation was unexpected as we did not find differences on WIC participation between mothers with less than High School and mother’s with High School and secondary education, which could be attributed to the sample design as Fragile Families is a representative study of families in poverty.

The results from model 1 indicate that in fact the odds of WIC participation are larger for all mothers (except naturalized non-Hispanic) compared to U.S. white mothers. Having model 1 as a benchmark, we then examine the effects of risk of deportation and legislative threat on WIC use.

From model 2, the findings suggest that there is evidence that risk of deportation does have an effect on the probability of WIC take-up. This finding is important as it is the first study to measure and test risk of deportation as a predictor of WIC uptake. Moreover, once we control for risk of deportation and legislative threat we can better understand program use across family typologies. As hypothesized, risk of deportation is negatively associated with WIC participation. For a one percentage change in risk of deportation, the odds of WIC participation are expected to decrease by a factor of 0.026, holding all else constant, which is marginally statistically significant at the 0.1 level. In other words, for a one percentage increase in risk of deportation, the odds of participating in WIC decrease by 97 percent, holding all else constant. Moreover, we do not find evidence between the anti-immigrant legislations and WIC participation.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

This paper finds evidence that mixed-status families have higher odds of WIC uptake compared to their U.S. born white counterparts. This finding is not surprising given the rates of WIC use among Latino populations. However, this finding is novel as this is the first to disaggregate the Latino population and provides in depth heterogeneity within this growing population. Our main contribution suggest that risk of deportation does negatively affect WIC uptake, and once we control for this variable, the odds of WIC uptake increase substantially for mixed-status Mexican families, while holding other variables constant. This finding is of great importance, as it suggests that risk of being deported is having a chilling effect and preventing US children from receiving aid. This is of major concern as WIC’s mission is to safeguard the health of low-income families. Mixed-status families and Mexican mixed-status in particular should be of critical concern for policy makers interested in alleviating poverty in complex families. Mixed-status Mexican families are extremely vulnerable in this regard as they are more likely to live in poverty, are less likely to have access to health care, and living in the shadows of US society. Moreover, these families are especially at risk as family disruption through deportation removal is a real occurrence among these families.

This study is important to as it adds to the program evaluation literature that has yet to address the impact risk of deportation has had on the “chilling effect” of social services. More importantly, our analysis provides a typology and framework to study mixed-status families and evaluate their usage of WIC. Ultimately, our analysis has the potential to help service providers address the needs of children living in complex family structures and policy makers interested in understanding how these families utilize social services.

Finally, deportations and their negative association with WIC uptake contribute to the continued marginalization of this already vulnerable community. This analysis then has important implications for scholars of immigration and immigrant policy, public health researchers, and policy-makers concerned with the unintended consequences of anti-immigrant sentiment across the nation. As comprehensive immigration reform has failed to pass through the Obama administration, we hope Congress can put politics aside and realize that we are shooting ourselves in the foot by not properly investing in our youth, which is our greatest asset. Future work in this area should address the impact of deportations on health outcomes among mixed-status families with an emphasis on intra-family dynamics. Research in this area should also examine social service uptake across mixed-status families as we expect there to be differences in uptake across family type and program type based on eligibility and demand.

Footnotes

Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act [“Immigration Law” PL 104-208], the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 [PL 105-33], the Agricultural Research, Extension and Education Reform Act of 1998 [PL 105-185], the Noncitizen Benefit Clarification and Other Technical Amendments Act of 1998 [PL 105-306], the Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000 [P.L. 106-386], and the Food Stamp Reauthorization Act of 2002 [PL 107-171].

Officially passed under the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 but states did not really start adopting 237(g) agreements until 2008.

Secure Communities was adopted in 2008 to focus on the removal of the most dangerous undocumented aliens. This program is collaboration between local law officials, FBI, and ICE to double-check fingerprints of persons detained in local jails. The unintended consequences have been the deportation of aliens who have committed minor traffic violations and mother’s who have U.S. born children.

Various derivations of this model have been tested for specification, multi-collinearity and robustness.

Obtained through the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) are now publicly available.

Estimates for unauthorized immigrants are provided by the Pew Hispanic Center.

This methodology employs a combination of 17 search terms, including: Alien OR immigra! OR “nonimmigra!” OR citizenship OR noncitizen OR “non-citizen” OR “not a citizen“OR undocumented OR “lawful presence” OR “legal! presen!: OR “legal permanent residen!” OR “lawful permanent resident” OR migrant OR “basic pilot program” OR “employment eligibility” OR “unauthorized worker” OR “human trafficking” AND NOT (“responsible citizenship” OR “good citizenship” OR “citizenship training” OR unborn OR Alienate OR alienation OR “alien insur!” OR “alien company” OR “alien reinsure!”

When citizenship status is missing (N=223), mothers who migrated to the U.S. prior to 1986 are categorized as naturalized citizens. Those migrating during or after 1986 are classified as non-citizens.

Contributor Information

Edward D. Vargas, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Maureen A. Pirog, Indiana University, University of Johannesburg

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- American Immigration Council. Who and Where the DREAMers Are, Revised Estimates: A Demographic Profile of Immigrants Who Might Benefit from the Obama Administration’s Deferred Action Initiative. 2012 Oct; Accessed online on 11/15/2012 at: http://www.immigrationpolicy.org/issues/DREAM-Act. [Google Scholar]

- Asch S, Leake B, Gelberg L. Does Fear of Immigration Authorities Deter Tuberculosis Patients From Seeking Care? Western Journal Medicine. 1994;161:373–376. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk ML, Schur CL. The Effect of Fear on Access to Care Among Undocumented Latino Immigrants. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2001;3(3):151–151. doi: 10.1023/A:1011389105821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besharov DJ, Germanis P. Rethinking WIC: An Evaluation of the Women, Infants, and Children Program. Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Beverly S. Material Hardship in the United States: Evidence from the Survey of Income and Program Participation. Social Work Research. 2001;25(3):143. [Google Scholar]

- Bitler Marianne P, Currie Janet, Scholz John Karl. WIC Eligibility and Participation. The Journal of Human Resources. 2003;38:1139–1179. [Google Scholar]

- Bitler MP, Currie J. Does WIC work? The effects of WIC on pregnancy and birth outcomes. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 2005;24(1):73–93. doi: 10.1002/pam.20070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blau Francine. The Use of Transfer Payments by Immigrants. Industrial and Labor Relations Review. 1984;37 (2):222–239. [Google Scholar]

- Borjas George, Hilton Lynette. Immigration and the Welfare State: Immigrant Participation in Means-Tested Entitlement Programs. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1996;111(2):575–604. [Google Scholar]

- Borjas George, Trejo Stephen. Immigrant Participation in the Welfare System. Industrial and Labor Relations Review. 1999;44(2):195–211. [Google Scholar]

- Borjas George, Trejo Stephen. National Origin and Immigrant Welfare Recipiency. Journal of Public Economics. 1993;50(3):325–344. [Google Scholar]

- Briggs Vernon. Report of the Select Commission on Immigration and Refugee Policy: Critique Human Resource Studies. Faculty Publications. 1982 [Google Scholar]

- Broder Tanya, Blazer Jonathan. Overview of Immigrant Eligibility for Federal Programs. National Immigration Law Center; 2011. Accessed online on 11/15/2012 at http://www.nilc.org/overview-immeligfedprograms.html. [Google Scholar]

- Brown Richard, Wyn Roberta, Ojeda Victoria D. Access to Health Insurance and Health Care for Children in Immigrant Families. Los Angeles: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; 1999. Jun, [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brien MJ, Swann CA. Manuscript. SUNY-Stony Brook Department of Economics; 2001. Prenatal WIC participation and infant health: Selection and maternal fixed effects. [Google Scholar]

- Buescher PA, Larson LC, Nelson MD, Lenihan AJ. Prenatal WIC Participation Can Reduce Low Birth Weight and Newborn Medical Costs: A Cost Benefit Analysis of WIC Participation in North Carolina. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1993;93(2):163–166. doi: 10.1016/0002-8223(93)90832-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buescher Paul A, et al. Child Participation in WIC: Medicaid Costs and Use of Health Care Services. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(1) doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.1.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capps Randy, Castaneda RM, Ajay Chaudry, Robert Santos. Paying the Price: The Impact of Immigration Raids on America’s Children. A Report by the Urban Institute for the National Council of La Raza. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Castner L, Mabli J, Sykes J. Dynamics of WIC Program Participation by Infants and Children, 2001 to 2003. Final report submitted to USDA Food and Nutrition Service by Mathematica Policy Research, Inc; 2009. Apr, Retrieved from http://www.fns.usda.gov/ora/menu/published/WIC/FILES/WICDynamics2001-2003.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Case Anne, Lubotsky Darren, Paxson Christina. Economic Status and Health in Childhood: The Origins of the Gradient. The American Economic Review. 2002;92(5):1308–1344. doi: 10.1257/000282802762024520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterji Pinka, Bonuck Karen, Dhawan Simi, Deb Nandini. WIC Participation and The Initiation and Duration of Breastfeeding. Institute for Research on Poverty. 2002 Discussion Paper no. 1246-02. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterji Pinka, Jeanne Brooks-Gunn. WIC Participation, Breastfeeding Practices, and Well-Child Care Among Unmarried, Low-Income Mothers. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(8):1324–1327. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.8.1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devaney BL, Bilheimer L, Schore J. Medicaid Costs and Birth Outcomes: The Effects of Prenatal WIC Participation and Prenatal Care. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 1992;11(4):573–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez Donald J, Charney Evan., editors. From Generation to Generation: The Health and Well-Being of Children in Immigrant Families. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 1998. p. 10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fomby P, Cherlin A. Public Assistance Use Among U.S.-born Children of Immigrants. The International Migration Review. 2004;38(2):584–610. [Google Scholar]

- Fenton J, Moss N, Khalil H, Asch S. Effect of California's Proposition 187 on the Use of Primary Care Clinics. Western Journal of Medicine. 1997;166:16–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fix Michael, Zimmermann Wendy. All Under One Roof: Mixed-Status Families in an Era of Reform. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fix Michael, Ron Haskins. Welfare Benefits for Non-citizens. Brookings Institute: Center of Children and Families Briefs, Number 15 of 48. 2002 Retrieved from: http://www.brookings.edu/research/papers/2002/02/02immigration-fix. [Google Scholar]

- Fortuny K. Master’s Thesis-Georgetown University. 2010. Participation of low-Income Immigrants in the Women, Infants, and Children Program. Retrieved from: http://repository.library.georgetown.edu/handle/10822/553730. [Google Scholar]

- Heflin Colleeen, Iceland John. Poverty, Material Hardship, and Depression. Social Science Quarterly. 2009;90(5):1051–1071. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6237.2009.00645.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez D, Denton NA, McCartney SE. Early education Programs: Differential Access Among Young Children in Newcomer and Native Families. In: Waters M, Alba R, editors. The Next Generation: Immigrant youth and Families in Comparative Perspective. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Johnson Kevin. Public Benefits and Immigration: The Intersection of Immigration Status, Ethnicity, Gender and Class. 1995 42 UCLA L. REV. 1509, 1521. [Google Scholar]

- Joyce T, Gibson D, Colman S. The Changing Association Between Prenatal Participation in WIC and Birth Outcomes in New York City. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 2005;24(4):661–685. doi: 10.1002/pam.20131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler Lucinda R, O'Shea Robert M, Duffy Linda C, Buck Germaine M. Factors Associated with Rates of Participation in WIC by Eligible Pregnant Women. Public Health Reports. 1992;107(1) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy ET, et al. Evaluation of WIC Supplemental Feeding on Birth Weight. Journal of American Diet Association. 1982;80:220–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotelchuck M, et al. WIC Participation and Pregnancy Outcomes: Massachusetts Statewide Evaluation Project. American Journal of Public Health. 1984;74:1086–1092. doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.10.1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku Leighton. Factors Influencing Early Prenatal Enrollment in the WIC Program. Public Health Reports. Association of Schools of Public Health. 1974;104(3):301–306. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig J, Miller M. Interpreting the WIC Debate. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 2005;24(4):691–701. doi: 10.1002/pam.20133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer S, Jencks C. Poverty and the Distribution of Material Hardship. The Journal of Human Resources. 1989;24(1):88–114. [Google Scholar]

- Park Lisa Sun-Hee. Perpetuation of Poverty through Public Charge. 2000 78 Denv. U. L. Rev. 1162. [Google Scholar]

- Passel Jeffrey S, Randy Capps, Michael Fix. Undocumented Immigrants: Facts and Figures. Urban Institute Immigration Studies Program; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Passel Jeffrey S. Unauthorized Migrants: Numbers and Characteristics. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center; 2005. Retrieved from: http://pewhispanic.org/files/reports/46.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Passel Jeffrey, D’Vera Cohn. Trends in Unauthorized Immigration: Undocumented Inflow Now Trails Legal Inflow Source: Urban Institute Analysis of March 2005 U.S. Current Population Survey Data. Pew Hispanic Center; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Passel JS. Unauthorized immigrants and their U.S.-born children. Pew Hispanic Center; 2010. http://pewhispanic.org/files/reports/125.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Perreira K, Crosnoe R, Fortuny K, Pedroza J, Ulvestad K, Weiland C, Yoshikawa H, Chaudry A. Barriers to Immigrants’ Access to Health and Human Services Programs, ASPE Research Brief. 2012 Retried from: http://aspe.hhs.gov/hsp/11/ImmigrantAccess/Barriers/rb.shtml.

- Plyler v. Doe, 457 U.S. 202. 1982 [Google Scholar]

- Rush D. National WIC Evaluation. Vol. 1. Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle, NC: Summary Report to the U.S. Department of Agriculture; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Schlosberg C, Wiley D. The Impact of INS Public Charge Determinations on Immigrant Access to Health Care. National Health Law Program and NILC. 1998 [Google Scholar]

- Schramm W. Prenatal Participation in WIC related to Medicaid Costs for Missouri Newborns. Public Health Rep. 1982;101:607–614. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schramm WF. WIC Prenatal Participation and its Relationship to Newborn Medicaid Costs in Missouri: a Cost/Benefit Analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 1985;75(8):851–857. doi: 10.2105/ajph.75.8.851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz J, Popkin BM, Tognetti J, Zohoori N. Does WIC Participation Improve Breast-Feeding Practices? American Journal Of Public Health. 1995;85(5):729–731. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.5.729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan J, Turner L, Danziger S. The Relationship between Income and Material Hardship. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 2008;27(1):63–81. [Google Scholar]

- Swann C. The Dynamics of Prenatal WIC Participation. Institute for Research on Poverty. 2003 #1259-03. Retrieved from: http://www.ssc.wisc.edu/irp. [Google Scholar]

- Teitler Julien O, Reichman Nancy E, Nepomnyaschy Lenna. Sources of Support, Child Care, and Hardship Among Unwed Mothers, 1999–2001. Social Services Review. 2004;78(1):125–148. [Google Scholar]

- Tiehen L, Jacknowitz A. Why wait? Examining Delayed WIC Participation Among Pregnant Women. Contemporary Economic Policy. 2008;26(4):518–538. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa H, Godfrey EB, Rivera AC. Access to Institutional Resources as a Measure of Social Exclusion: Relations with Family Process and Cognitive Development in the Context of Immigration. In: Yoshikawa H, Way N, editors. Beyond the Family: Contexts of Immigrant Children’s Development. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. Vol. 121. 2008. pp. 63–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziol-Guest Kathleen, Hernandez Daphne C. First- and Second-Trimester WIC Participation Is Associated with Lower Rates of Breastfeeding and Early Introduction of Cow's Milk during Infancy. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2010;110(5):702–709. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Hispanic Center. National Survey of Latinos: As Illegal Immigration Issue Heats Up, Hispanics Feel a Chill. 2007 Retrieved from: http://pewhispanic.org/files/reports/84.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Section 287 ICE found in the Office of Public Affairs of U.S. Department of Homeland Security Worksite. http://www.ice.gov/doclib/pi/news/factsheets/060816dc287gfactsheet.pdf.

- Worksite Enforcement found in the Office of Public Affairs of U.S. Department of Homeland Security Worksite. [Updated: April 30, 2009]; Enforcement Overview http://www.ice.gov/doclib/pi/news/factsheets/worksite.pdf.

- Department of Homeland Security, Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2005. http://www.dhs.gov/ximgtn/statistics/publications/YrBk05En.shtm.

- The Urban Institute. Children of Immigrants: Facts and Figures. 2006 Retrieved from: http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/900955_children_of_immigrants.pdf.

- U.S. General Accounting Office. Early Intervention: Federal Investments Like WIC Can Produce Savings, HRD-92-18. Washington, DC: US General Accounting Office; 1992. Retrieved from: http://www.gao.gov/products/HRD-92-18. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Agriculture-Food and Nutrition Service. National Survey of WIC Participants II. 2012 Retrieved from: http://www.fns.usda.gov/Ora/menu/Published/WIC/FILES/NSWP-II.pdf.

- United States Department of Agriculture-Food and Nutrition Service. National and State-Level Estimates of Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) Eligibles and Program Reach. 2013 Retrieved from: http://www.fns.usda.gov/Ora/menu/Published/WIC/FILES/WICEligibles2010Vol1.pdf.