Abstract

Objective

Attitudes towards marijuana are changing, the prevalence of DSM-IV cannabis use disorder has increased, and DSM-5 modified the diagnostic criteria for cannabis use disorders. Therefore, updated information is needed on the prevalence, demographic characteristics, psychiatric comorbidity, disability and treatment for DSM-5 cannabis use disorders in the US adult population.

Method

In 2012–2013, a nationally representative sample of 36,309 participants ≥18 years were interviewed in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III (NESARC-III). Psychiatric and substance use disorders were assessed using the Alcohol Use Disorders and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-5.

Results

Prevalence of 12-month and lifetime marijuana use disorder was 2.5% and 6.3%. Among those with 12-month and lifetime marijuana use disorder, marijuana use was frequent; mean days used per year was 225.3 (SE=5.69) and 274.2 (SE=3.76). Odds of 12-month and lifetime marijuana use disorder were higher for men, Native Americans, those unmarried, with low incomes, and young adults, (e.g., OR=7.2, 95% CI 5.5–9.5 for 12-month disorder among those 18–24 years compared to those ≥45 years). Marijuana use disorder was associated with other substance disorders, affective, anxiety and personality disorders. Twelve-month marijuana use disorder was associated with disability. As disorder severity increased, virtually all associations became stronger. Only 24.3% with lifetime marijuana use disorder participated in 12-step programs or professional treatment.

Conclusions

DSM-5 marijuana use disorder is prevalent, associated with comorbidity and disability, and often untreated. Findings suggest the need to improve prevention methods, and educate the public, professionals and policy makers about the harms associated with marijuana use disorders and available interventions.

Cannabis use and DSM-IV cannabis use disorders are associated with adverse consequences (1, 2), including cognitive decline (3–5), impaired educational or occupational attainment (6–8), impaired driving ability (9–13), emergency room visits (14), psychiatric symptoms (15–17), poor quality of life (18), other drug use (19), and risk of addiction or substance use disorders (1). Despite this, Americans increasingly view marijuana use as harmless (1, 20–22) and support its legalization (23). Reflecting these changing views, twenty-three states now have laws permitting marijuana use for medical purposes (of which four also legalized marijuana for recreational use). Marijuana use is more prevalent in these twenty-three states than in others (24–26). Consistent with these changes, marked increases have occurred in the U.S. prevalence of DSM-IV cannabis use disorder among veterans (27) and adults in the general population (28, 29). Cannabis-related emergency room visits and fatal car crashes have also increased (11, 30).

Earlier studies conducted when cannabis use was less prevalent (and therefore more deviant) showed a high degree of comorbidity between cannabis use disorders and other common mental disorders (17, 31–34). However, the increased prevalence of adult cannabis use disorders may now include more individuals without vulnerability to other psychiatric disorders. If so, comorbidity patterns may have changed; thus, the increased prevalence of cannabis use disorder creates a need for updated information on its comorbidity.

Additionally, all knowledge regarding the U.S. prevalence, demographic and clinical correlates of cannabis use disorders is based on DSM-IV definitions (17, 29, 31). In DSM-5, the diagnostic criteria for cannabis use disorders were revised (35) to combine dependence and abuse criteria into a single disorder (36), drop the legal problems criterion, and add craving, withdrawal and a severity metric (mild, moderate, severe) (36). Therefore, new information on DSM-5 cannabis use disorders is needed.

We provide the first nationally representative information on DSM-5 cannabis use disorder using data from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) 2012–2013 NESARC-III. This includes current and lifetime prevalence, age of onset, frequency of cannabis use among those diagnosed, demographic correlates, psychiatric comorbidity, disability, and likelihood of participation in interventions including professional treatment and 12-step programs.

METHOD

Sample

The NESARC-III target population was the noninstitutionalized civilian population ≥18 years in households and selected group quarters (37, 38). Respondents were selected through multistage probability sampling, including primary sampling units (counties/groups of contiguous counties); secondary sampling units (SSU - groups of Census-defined blocks); and tertiary sampling units (households within SSUs from which respondents were selected, with Blacks, Asians, and Hispanics oversampled. Data were collected April 2012–June 2013, and analyzed May-June, 2015. Data were adjusted for nonresponse and weighted to represent the U.S. population based on the 2012 American Community Survey (39). These weighting adjustments compensated adequately for nonresponse (38). The total sample size was 36,309: household response rate was 72%; person-level response rate, 84%, and overall response rate, 60.1% comparable to other current U.S. national surveys (40, 41). NESARC-III sample characteristics are presented elsewhere (38). Informed consent was electronically recorded; respondents received $90.00 for participation. Institutional review boards at the National Institutes of Health and Westat (NESARC-III contractor) approved the study protocol.

Assessments

The NIAAA Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-5 (AUDADIS-5) (42) was the diagnostic interview. AUDADIS-5 measures drug and alcohol use (e.g., onset, frequency), DSM-5 drug, alcohol and nicotine use disorders, and selected psychiatric disorders in the last 12 months and prior to the last 12 months. DSM-5 cannabis use disorder diagnoses required ≥2 of 11 criteria within a 12-month period. Twelve-month and prior diagnoses were aggregated to form lifetime diagnoses. Consistent with DSM-5, cannabis use disorders were classified as mild (2–3 criteria), moderate (4–5 criteria) or severe (≥6 criteria).

Test-retest reliability of 12-month and lifetime cannabis use was substantial (kappa=0.78, 0.77) in a general population sample (43). Test-retest reliabilities of DSM-5 cannabis use disorders (kappa=0.41, 0.41) and their dimensional criteria scales (intraclass correlation coefficients [ICC]=0.70, 0.71) were fair to substantial in a general population sample (N=1006) (44). Procedural validity was assessed through blind clinician re-appraisal using the semi-structured, clinician-administered Psychiatric Research Interview for Substance and Mental Disorders, DSM-5 version (PRISM-5) (45) in a separate general population sample (N=712). AUDADIS-5/PRISM-5 concordance was moderate for cannabis use disorder (kappa=0.60, 0.51) and substantial for its dimensional criteria scale (ICC=0.79, 0.78) (46).

Other Psychiatric Disorders

DSM-5 alcohol, nicotine and drug disorder diagnoses were derived similarly to cannabis disorder diagnoses. Test-retest reliabilities were moderate to substantial for these disorders (kappa=0.40–0.87), and their criteria scales (ICC=0.45–0.84) (44). AUDADIS-5/PRISM-5 concordance for alcohol, nicotine and drug disorders and corresponding criteria scales was fair to substantial (kappa=0.36–0.66; ICCs=0.68–0.91) (46).

DSM-5 mood disorders included primary major depression, dysthymia, bipolar I and bipolar II disorders. Anxiety disorders included panic, agoraphobia, social and specific phobias and generalized anxiety. Consistent with DSM-5, primary mood and anxiety diagnoses excluded substance- and medically-induced disorders. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and schizotypal, borderline and antisocial personality disorders were also assessed. Reliability and validity of these diagnoses was fair to moderate (44, 47).

Disability/Impairment

Current disability was measured using the 12-item Short Form Health Survey, version 2 (SF-12v2), a widely-used survey measure (48). SF-12v2 scales included mental health, social functioning, role emotional functioning, and Mental Component Summary (MCS). Each SF-12v2 norm-based disability score has mean=50, standard deviation=±10, and range=0–100; lower scores indicate greater disability.

Service utilization

Utilization of services for problems with cannabis among individuals with cannabis use disorder was assessed for 14 modalities, including professional inpatient and outpatient treatment settings, and peer support, e.g., 12-step programs such as Alcoholics Anonymous.

Statistical Analyses

Weighted means and percentages were computed for continuous and categorical correlates of 12-month and lifetime cannabis use disorder, overall and by severity level. Odds ratios (ORs) from multivariable logistic regressions indicated associations between cannabis use disorder and each sociodemographic characteristic, adjusted for all others. ORs of cannabis use disorders with psychiatric comorbidity were derived similarly. The relationship of 12-month cannabis use disorder to SF-12v2 scales was assessed using linear regression, controlling for sociodemographic characteristics. To account for the NESARC-III complex sample design, analyses utilized SUDAAN, version 11.0 (49).

Results

Prevalence, onset, frequency of use

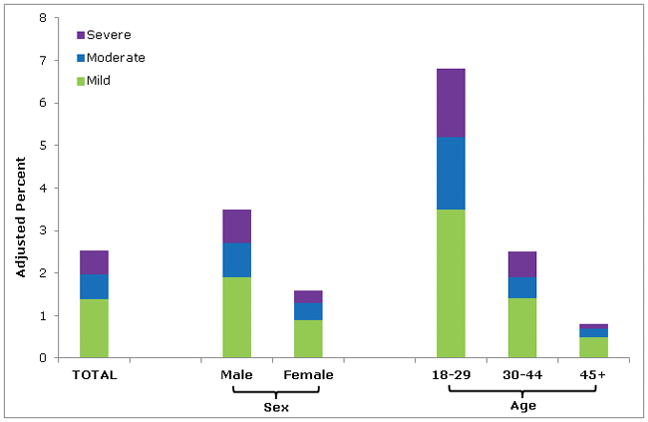

Table 1 shows the prevalence and standard errors of 12-month and lifetime DSM-5 cannabis use disorder for the entire sample and by sociodemographic characteristics. (In addition, Figure 1 summarizes 12-month prevalence for the entire sample and by sex and age). As shown in Table 1, the prevalence of 12-month and lifetime DSM-5 cannabis use disorder was 2.54% and 6.27%. The 12-month and lifetime prevalence of mild, moderate and severe cannabis use disorders was 1.38%, 0.59% and 0.57%; and 2.85%, 1.42% and 2.00%, respectively.

Table 1.

Prevalence of 12-Month and Lifetime DSM-5 Cannabis Use Disorder by Sociodemographic Characteristics

| Characteristic | 12-Month 21 Cannabis Use Disorder, % (SE) | Lifetime Cannabis Use Disorder, % (SE) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any cannabis use disorder (n=972) | Mild (n=516) | Moderate (n=242) | Severe (n=214) | Any cannabis use disorder (n=2,242) | Mild (n=1,002) | Moderate (n=529) | Severe (n=711) | |

| Total | 2.54 (0.11) | 1.38 (0.07) | 0.59 (0.05) | 0.57 (0.05) | 6.27 (0.23) | 2.85 (0.13) | 1.42 (0.10) | 2.00 (0.10) |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 3.5 (0.19) | 1.9 (0.12) | 0.8 (0.08) | 0.8 (0.10) | 8.4 (0.34) | 3.7 (0.18) | 1.9 (0.16) | 2.8 (0.17) |

| Female | 1.7 (0.13) | 0.9 (0.09) | 0.4 (0.06) | 0.3 (0.04) | 4.3 (0.23) | 2.1 (0.15) | 1.0 (0.10) | 1.3 (0.10) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| White | 2.2 (0.14) | 1.3 (0.09) | 0.5 (0.06) | 0.4 (0.06) | 6.7 (0.30) | 3.2 (0.17) | 1.5 (0.14) | 2.0 (0.14) |

| Black | 4.5 (0.39) | 2.1 (0.21) | 1.2 (0.15) | 1.2 (0.21) | 7.2 (0.47) | 3.1 (0.25) | 1.7 (0.18) | 2.5 (0.27) |

| Native American | 5.3 (1.45) | 2.7 (1.31) | 0.9 (0.36) | 1.7 (0.72) | 11.5 (1.84) | 4.9 (1.33) | 1.7 (0.58) | 4.9 (1.12) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1.3 (0.28) | 0.4 (0.18) | 0.4 (0.18) | 0.4 (0.17) | 3.1 (0.50) | 1.4 (0.36) | 0.8 (0.20) | 0.9 (0.26) |

| Hispanic | 2.6 (0.21) | 1.2 (0.16) | 0.7 (0.13) | 0.7 (0.12) | 4.5 (0.41) | 1.7 (0.22) | 1.2 (0.20) | 1.6 (0.20) |

| Age, y | ||||||||

| 18–29 | 6.9 (0.40) | 3.5 (0.27) | 1.7 (0.18) | 1.6 (0.17) | 11 (0.56) | 4.7 (0.35) | 2.9 (0.25) | 3.5 (0.24) |

| 30–44 | 2.5 (0.21) | 1.4 (0.16) | 0.5 (0.09) | 0.6 (0.11) | 7.4 (0.38) | 3.2 (0.23) | 1.5 (0.15) | 2.8 (0.23) |

| ≥45 | 0.8 (0.07) | 0.5 (0.05) | 0.2 (0.03) | 0.1 (0.04) | 3.7 (0.19) | 2.0 (0.13) | 0.8 (0.09) | 1.0 (0.10) |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married/cohabiting | 1.3 (0.10) | 0.7 (0.07) | 0.3 (0.05) | 0.3 (0.06) | 5.0 (0.23) | 2.3 (0.16) | 1.0 (0.09) | 1.7 (0.12) |

| Widowed/separated/divorced | 1.9 (0.21) | 1.1 (0.18) | 0.4 (0.08) | 0.4 (0.10) | 5.3 (0.34) | 2.6 (0.25) | 1.1 (0.14) | 1.5 (0.17) |

| Never married | 6.4 (0.36) | 3.3 (0.26) | 1.6 (0.17) | 1.4 (0.14) | 10.4 (0.45) | 4.4 (0.29) | 2.8 (0.23) | 3.2 (0.19) |

| Education | ||||||||

| Less than high school | 3.2 (0.30) | 1.6 (0.2) | 0.8 (0.18) | 0.8 (0.15) | 5.7 (0.42) | 2.3 (0.21) | 1.5 (0.23) | 1.9 (0.22) |

| High school | 3.0 (0.20) | 1.6 (0.15) | 0.7 (0.10) | 0.7 (0.12) | 7.4 (0.40) | 3.5 (0.25) | 1.6 (0.18) | 2.3 (0.19) |

| Some college or higher | 2.2 (0.14) | 1.2 (0.10) | 0.5 (0.06) | 0.5 (0.06) | 5.9 (0.25) | 2.7 (0.16) | 1.3 (0.11) | 1.9 (0.12) |

| Family income, $ | ||||||||

| 0–19,999 | 4.9 (0.30) | 2.5 (0.19) | 1.1 (0.14) | 1.3 (0.15) | 8.5 (0.45) | 3.6 (0.27) | 2.1 (0.21) | 2.8 (0.22) |

| 20,000–34,999 | 2.5 (0.23) | 1.5 (0.18) | 0.5 (0.08) | 0.6 (0.11) | 6.5 (0.37) | 3.2 (0.25) | 1.3 (0.15) | 2.0 (0.19) |

| 35,000–69,999 | 2.1 (0.16) | 1.2 (0.12) | 0.5 (0.10) | 0.4 (0.07) | 6.2 (0.28) | 2.9 (0.22) | 1.3 (0.14) | 2.0 (0.14) |

| ≥70,000 | 1.2 (0.14) | 0.7 (0.10) | 0.3 (0.08) | 0.2 (0.05) | 4.6 (0.30) | 2.1 (0.19) | 1.1 (0.16) | 1.4 (0.16) |

| Urbanicity | ||||||||

| Urban | 2.7 (0.12) | 1.5 (0.09) | 0.6 (0.06) | 0.6 (0.06) | 6.5 (0.23) | 3.0 (0.14) | 1.5 (0.10) | 2.1 (0.10) |

| Rural | 1.8 (0.21) | 1.0 (0.13) | 0.4 (0.08) | 0.5 (0.11) | 5.5 (0.47) | 2.4 (0.26) | 1.2 (0.19) | 1.8 (0.22) |

| Region | ||||||||

| Northeast | 2.7 (0.26) | 1.3 (0.17) | 0.8 (0.17) | 0.6 (0.11) | 7.0 (0.45) | 3.0 (0.34) | 1.5 (0.24) | 2.5 (0.19) |

| Midwest | 2.3 (0.23) | 1.2 (0.17) | 0.5 (0.08) | 0.6 (0.14) | 6.5 (0.37) | 2.9 (0.26) | 1.4 (0.15) | 2.3 (0.21) |

| South | 2.3 (0.20) | 1.2 (0.12) | 0.5 (0.08) | 0.5 (0.09) | 5.3 (0.49) | 2.5 (0.24) | 1.3 (0.20) | 1.5 (0.19) |

| West | 3.1 (0.22) | 1.8 (0.14) | 0.7 (0.1) | 0.6 (0.09) | 7.0 (0.34) | 3.3 (0.22) | 1.6 (0.17) | 2.1 (0.15) |

Figure 1.

Prevalence of 12-Month DSM-5 Cannabis Use Disorder in the United States, by Severity

aPrevalences reflect numbers adjusted for nonresponse, and weighted to represent the U.S. population based on the 2012 American Community Survey. Total n=36,309; Males n=15,862; Females n=20,447; Age 18–29 n=8,126; Age 30–44 n=10,135; Age 45+ n=5,806.

Mean age at onset of cannabis use disorder was 21.7 (SE=0.23) years; mean ages at onset of mild, moderate and severe disorders were 23.1 (SE=0.38), 21.2 (SE=0.44), and 20.1 (SE=0.34) years.

Among those with 12-month cannabis use disorder, the mean number of days cannabis was used in the prior 12 months was 225.3 (SE=5.69); among those with mild, moderate and severe 12-month disorder, the mean days used was 206.5 (SE=7.79), 243.5 (SE=10.60), and 252.2 (SE=14.03). Among those with lifetime cannabis use disorder, the mean number of days cannabis was used per year during the period of heaviest use was 274.2 (SE=3.76); among those with mild, moderate and severe lifetime disorder, mean days used was 243.7 (SE=5.98), 284.2 (SE=6.36), and 310.4 (SE=4.48), respectively.

Sociodemographic characteristics

Table 2 shows the adjusted odds ratios of DSM-5 cannabis use disorder by sociodemographic characteristics. Men had higher odds of cannabis use disorder than women, across timeframes and severity levels (OR=1.8–2.8).

Table 2.

Adjusted Odds Ratios (AOR) of 12-Month and Lifetime DSM-5 Cannabis Use Disorder by Sociodemographic Characteristicsa

| Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval)b | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | 12-Month Cannabis Use Disorder | Lifetime Cannabis Use Disorder | ||||||

| Any Cannabis Use Disorder | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Any Cannabis Use Disorder | Mild | Moderate | Severe | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 2.2 (1.84–2.68) | 2.2 (1.77–2.79) | 1.8 (1.26–2.51) | 2.8 (1.99–4.02) | 2.1 (1.84–2.33) | 1.9 (1.64–2.18) | 2.1 (1.64–2.57) | 2.4 (1.93–2.95) |

| Female | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| White | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) |

| Black | 1.4 (1.11–1.79) | 1.1 (0.88–1.47) | 1.7 (1.09–2.56) | 2.0 (1.20–3.30) | 0.9 (0.74–1.09) | 0.8 (0.64–1.00) | 0.9 (0.64–1.26) | 1.1 (0.77–1.43) |

| Native American | 2.1 (1.18–3.67) | 1.7 (0.66–4.59) | 1.7 (0.75–3.86) | 3.6 (1.41–9.36) | 1.7 (1.18–2.38) | 1.5 (0.87–2.62) | 1.1 (0.55–2.20) | 2.4 (1.42–3.94) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.4 (0.24–0.59) | 0.2 (0.08–0.46) | 0.6 (0.27–1.47) | 0.8 (0.33–1.87) | 0.3 (0.25–0.49) | 0.3 (0.20–0.58) | 0.4 (0.22–0.64) | 0.3 (0.20–0.60) |

| Hispanic | 0.7 (0.52–0.81) | 0.5 (0.35–0.64) | 0.8 (0.46–1.40) | 1.1 (0.69–1.83) | 0.4 (0.37–0.55) | 0.4 (0.29–0.47) | 0.5 (0.34–0.79) | 0.5 (0.39–0.71) |

| Age, y | ||||||||

| 18–29 | 7.2 (5.45–9.51) | 6.5 (4.38–9.59) | 7.1 (4.58–10.98) | 9.7 (4.87–19.41) | 2.9 (2.53–3.40) | 2.4 (1.97–2.96) | 3.3 (2.41–4.51) | 3.6 (2.79–4.73) |

| 30–44 | 3.6 (2.71–4.75) | 3.5 (2.40–5.03) | 3.0 (1.84–4.82) | 4.8 (2.46–9.36) | 2.3 (1.96–2.62) | 1.9 (1.50–2.31) | 2.2 (1.65–2.95) | 3.1 (2.36–4.01) |

| ≥45 | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married/cohabiting | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) |

| Widowed/separated/divorced | 1.8 (1.30–2.49) | 1.8 (1.18–2.74) | 1.8 (0.92–3.39) | 1.8 (0.93–3.59) | 1.2 (1.02–1.36) | 1.2 (0.96–1.54) | 1.3 (1.00–1.79) | 1.0 (0.79–1.34) |

| Never married | 1.8 (1.48–2.24) | 1.8 (1.26–2.46) | 2.3 (1.53–3.52) | 1.5 (1.01–2.33) | 1.2 (1.07–1.40) | 1.2 (1.00–1.54) | 1.6 (1.26–2.05) | 1.0 (0.79–1.22) |

| Education | ||||||||

| Less than high school | 1.2 (0.92–1.60) | 1.2 (0.83–1.65) | 1.3 (0.72–2.47) | 1.2 (0.77–1.93) | 1.0 (0.82–1.16) | 0.9 (0.73–1.14) | 1.1 (0.74–1.58) | 1.0 (0.73–1.31) |

| High school | 1.1 (0.95–1.38) | 1.1 (0.86–1.46) | 1.2 (0.80–1.67) | 1.2 (0.79–1.83) | 1.2 (1.04–1.35) | 1.2 (1.04–1.48) | 1.1 (0.89–1.47) | 1.1 (0.91–1.43) |

| Some college or higher | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) |

| Family income, $ | ||||||||

| 0–19,999 | 2.5 (1.89–3.34) | 2.4 (1.61–3.51) | 2.0 (1.05–3.79) | 3.7 (2.00–6.79) | 1.7 (1.46–2.10) | 1.6 (1.26–2.16) | 1.6 (1.12–2.34) | 2.0 (1.43–2.81) |

| 20,000–34,999 | 1.5 (1.07–2.06) | 1.6 (1.06–2.46) | 1.1 (0.59–1.88) | 1.7 (0.91–3.35) | 1.4 (1.14–1.65) | 1.5 (1.19–1.92) | 1.1 (0.76–1.52) | 1.4 (1.00–1.97) |

| 35,000–69,999 | 1.4 (1.03–1.83) | 1.4 (0.96–2.06) | 1.4 (0.71–2.73) | 1.3 (0.70–2.31) | 1.3 (1.09–1.51) | 1.3 (1.05–1.69) | 1.1 (0.79–1.62) | 1.3 (1.04–1.73) |

| ≥70,000 | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) |

| Urbanicity | ||||||||

| Urban | 1.2 (0.92–1.48) | 1.3 (0.98–1.79) | 1.1 (0.72–1.63) | 0.9 (0.54–1.54) | 1.2 (0.98–1.40) | 1.3 (1.01–1.62) | 1.1 (0.79–1.48) | 1.1 (0.85–1.42) |

| Rural | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) |

| Region | ||||||||

| Northeast | 0.8 (0.65–1.06) | 0.7 (0.49–0.90) | 1.1 (0.64–1.83) | 1.1 (0.68–1.73) | 0.9 (0.80–1.10) | 0.8 (0.65–1.10) | 0.9 (0.60–1.25) | 1.1 (0.92–1.43) |

| Midwest | 0.6 (0.50–0.84) | 0.5 (0.39–0.77) | 0.7 (0.41–1.06) | 1.0 (0.58–1.72) | 0.8 (0.68–0.92) | 0.7 (0.58–0.91) | 0.7 (0.52–1.00) | 1.0 (0.76–1.21) |

| South | 0.6 (0.48–0.77) | 0.6 (0.43–0.73) | 0.6 (0.39–0.96) | 0.8 (0.46–1.25) | 0.7 (0.53–0.83) | 0.7 (0.53–0.86) | 0.7 (0.46–1.03) | 0.6 (0.47–0.85) |

| West | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) |

Significant (p < 0.05) odds ratios appear in bold font.

Odds ratios for associations of each sociodemographic variable with any, mild, moderate, and severe Cannabis use disorders are adjusted for all other sociodemographic characteristics.

Compared to whites, 12-month odds of cannabis use disorders were higher in Native Americans and Blacks, but lower in Asian/Pacific Islanders and Hispanics. By severity, 12-month odds were higher in blacks than whites at moderate and severe levels (OR=1.7–2.0), and lower in Asians/Pacific Islanders and Hispanics at low severity. Blacks did not differ from whites on odds of lifetime cannabis use disorder, but Asians/Pacific Islanders and Hispanics had lower odds than whites overall and across severity levels (OR=0.3–0.5).

Compared to those age ≥45, the odds for 12-month cannabis use disorder were substantially higher than in those age 18–29 (OR=7.2) and 30–44, (OR=3.6) overall, and across severity levels. For lifetime disorder, the odds were also significantly higher in those 18–29 and 30–44 than in those ≥45 (OR=1.9–3.6).

Compared to married respondents, odds for 12-month cannabis use disorder were higher in those never married, overall and across severity levels (OR=1.5–2.3); those previously married had higher odds than married respondents, but only at the mild severity level. Marital status and lifetime cannabis use disorder were weakly or not related.

Education was largely unrelated to cannabis use disorder. However, compared to those at the highest income level, odds of 12-month and lifetime disorders were greater for those at the lowest income level, overall and across severity levels (OR=1.6–3.7). Comparing odds of intermediate and highest income levels produced weaker and less consistent results.

Those in urban and rural areas did not differ. However, compared to those in the West, those in the Midwest or the South had significantly lower odds of 12-month and lifetime cannabis use disorders (OR=0.6–0.8). These regional differences were most consistent at the low severity level.

Comorbidity

12-month cannabis use disorder (Table 3) was associated with other substance disorders (OR=6.0–9.3), mood disorders (OR=2.7–5.0), anxiety disorders (OR=1.7–3.7), PTSD (OR=3.8) and personality disorders (OR=3.8–5.0). Lifetime cannabis use disorder (Table 3) was also associated with other substance disorders (OR=6.6–13.4), mood disorders (OR=2.6–3.8), anxiety disorders (OR=2.1–3.2), PTSD (OR=5.0) and personality disorders (OR=4.0–4.7). Across severity levels, 12-month and lifetime cannabis use disorders were associated with other disorders. Further, with few exceptions (12-month Bipolar II, agoraphobia and specific phobia), associations became stronger (i.e., progressively higher odds ratios) as severity of cannabis use disorder increased. For example, ORs of PTSD and 12-month mild, moderate and severe cannabis use disorder were 2.1, 6.2, and 9.5; of nicotine use disorder, 4.8, 7.3, and 10.5; and of borderline personality disorder, 4.0, 4.9, and 8.8. Supplemental Table 1 provides additional comorbidity information, i.e., 12-month and lifetime prevalence of DSM-5 cannabis use disorder (any, mild, moderate, severe) among participants with 12-month or lifetime diagnoses of each disorder in Table 3. Cannabis use disorders had higher prevalence among participants with other disorders than in the total sample. For any 12-month and lifetime cannabis use disorder, prevalence ranged from 4.0% and 10.7% (specific phobia) to 22.5% and 34.9% (other drug use disorder).

Table 3.

Adjusted Odds Ratios of 12-Month and Lifetime DSM-5 Cannabis Use Disorder and Psychiatric Disorders a

| Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12-Month Cannabis Use Disorder | Lifetime Cannabis Use Disorder | |||||||

| Any Cannabis Use Disorder | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Any Cannabis Use Disorder | Mild | Moderate | Severe | |

| Any other substance use disorder | 9.3 (7.70–11.21) | 7.4 (5.92–9.34) | 12.2 (7.76–19.31) | 13.1 (7.86–21.98) | 14.5 (11.95–17.60) | 10.5 (7.81–14.09) | 19.4 (13.56–27.72) | 21.9 (15.24–31.56) |

| Alcohol use disorder | 6.0 (5.10–6.97) | 5.1 (4.14–6.27) | 7.7 (5.06–11.60) | 6.8 (4.61–10.01) | 7.8 (6.95–8.74) | 6.1 (5.09–7.30) | 9.6 (7.51–12.31) | 10.1 (7.88–12.91) |

| Any other drug use disorder | 9.0 (6.65–12.19) | 6.6 (4.30–10.01) | 11.5 (7.18–18.42) | 13.4 (8.26–21.66) | 10.0 (8.56–11.76) | 7.9 (6.22–10.04) | 9.2 (7.29–11.69) | 14.6 (12.01–17.66) |

| Nicotine use disorder | 6.2 (5.24–7.34) | 4.8 (3.86–5.97) | 7.3 (5.11–10.41) | 10.5 (7.35–15.05) | 6.6 (5.79–7.64) | 5.1 (4.32–6.03) | 7.9 (6.08–10.25) | 8.9 (7.25–10.96) |

| Any mood disorder | 3.8 (3.10–4.56) | 2.8 (2.21–3.48) | 3.5 (2.55–4.75) | 8.1 (5.74–11.40) | 3.3 (2.94–3.73) | 2.3 (1.92–2.67) | 3.4 (2.67–4.31) | 5.6 (4.53–6.94) |

| Major depressive disorder | 2.8 (2.33–3.41) | 2.2 (1.77–2.84) | 3.1 (2.29–4.23) | 4.2 (2.76–6.40) | 2.6 (2.26–2.95) | 2.0 (1.65–2.47) | 2.6 (2.05–3.33) | 3.6 (2.97–4.34) |

| Bipolar I | 5.0 (3.65–6.75) | 3.4 (2.16–5.47) | 4.1 (2.29–7.22) | 10.1 (6.32–16.08) | 3.8 (3.10–4.59) | 2.2 (1.52–3.27) | 4.0 (2.82–5.80) | 5.9 (4.53–7.75) |

| Bipolar II | 2.7 (1.10–6.62) | 2.7 (0.80–9.46)b | 3.4 (0.74–15.51) b | 1.9 (0.42–8.18) b | 2.8 (1.51–5.23) | 2.3 (0.80–6.81) b | 3.3 (1.35–8.24) | 3.1 (1.34–7.26) |

| Any anxiety disorder | 2.8 (2.24–3.39) | 2.2 (1.64–2.93) | 2.9 (2.02–4.03) | 4.4 (2.96–6.56) | 2.9 (2.54–3.31) | 2.3 (1.87–2.73) | 3.0 (2.29–4.05) | 3.9 (3.16–4.86) |

| Panic disorder | 3.3 (2.50–4.48) | 2.5 (1.58–3.84) | 2.8 (1.60–5.04) | 6.6 (3.74–11.58) | 3.2 (2.66–3.76) | 2.4 (1.85–3.20) | 3.3 (2.29–4.72) | 4.3 (3.18–5.72) |

| Agoraphobia | 2.6 (1.64–4.06) | 2.4 (1.44–4.07) | 3.5 (1.39–9.08) | 2.0 (1.02–3.97) | 2.9 (2.25–3.79) | 2.1 (1.35–3.24) | 3.9 (2.35–6.34) | 3.5 (2.54–4.93) |

| Social phobia | 2.3 (1.61–3.27) | 1.3 (0.74–2.21) b | 3.5 (1.96–6.27) | 3.9 (1.85–8.18) | 2.7 (2.22–3.40) | 2.0 (1.42–2.90) | 2.6 (1.77–3.96) | 4.0 (2.85–5.53) |

| Specific phobia | 1.7 (1.28–2.29) | 1.4 (0.95–2.16) b | 2.2 (1.28–3.65) | 1.9 (1.21–3.14) | 2.1 (1.73–2.46) | 1.4 (1.04–1.91) | 2.9 (2.00–4.07) | 2.6 (2.01–3.24) |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 3.7 (2.79–5.02) | 3.0 (2.01–4.34) | 3.6 (2.40–5.50) | 6.3 (3.43–11.53) | 3.2 (2.75–3.74) | 2.5 (2.01–3.10) | 3.4 (2.51–4.47) | 4.3 (3.26–5.64) |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 4.3 (3.26–5.64) | 2.1 (1.34–3.30) | 6.2 (3.98–9.59) | 9.5 (6.18–14.75) | 3.8 (3.15–4.67) | 2.4 (1.81–3.21) | 4.3 (3.16–5.85) | 6.0 (4.55–7.88) |

| Any personality disorder | 4.8 (3.96–5.75) | 4.1 (3.30–4.99) | 4.4 (3.01–6.31) | 7.9 (4.98–12.59) | 4.7 (4.18–5.28) | 3.2 (2.76–3.74) | 4.7 (3.65–5.95) | 8.0 (6.34–10.19) |

| Schizotypal | 4.4 (3.60–5.46) | 3.7 (2.85–4.90) | 4.0 (2.82–5.63) | 7.0 (4.60–10.62) | 4.0 (3.46–4.72) | 2.7 (2.16–3.35) | 4.3 (3.26–5.60) | 6.2 (4.84–7.98) |

| Borderline | 5.0 (4.13–6.10) | 4.0 (3.13–5.15) | 4.9 (3.30–7.12) | 8.8 (5.83–13.41) | 4.5 (3.96–5.19) | 3.0 (2.49–3.53) | 4.6 (3.52–6.05) | 7.7 (6.17–9.67) |

| Antisocial | 3.8 (3.05–4.75) | 3.5 (2.61–4.62) | 3.9 (2.44–6.19) | 4.6 (2.95–7.18) | 4.7 (4.07–5.34) | 3.5 (2.89–4.27) | 4.4 (3.36–5.71) | 6.7 (5.26–8.53) |

Controlling for sex, age, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, family income, urban/rural, and region (Midwest, Northeast, South, West)

Except these odds ratios, all other odds ratios are significant (p < 0.05)

Disability

Respondents with 12-month cannabis use disorder differed significantly from others (p<0.001) on all disability components (Table 4), with disability increasing significantly as cannabis disorder severity increased. For those with severe cannabis use disorder, the mean Mental Component Summary score was ~.75 s.d. below the mean. Greatest impairment was found in the role emotional functioning domain, with a score.85 s.d. below the mean. By the exact number of DSM-5 cannabis use disorder criteria, increasing disorder severity was also generally associated with greater disability (lower SF-12 scores).

Table 4.

12-Month Cannabis Use Disorder and Mean SF-12 Norm-Based Mental Disability Scores

| Mean Norm-Based Scores (SE) | Mental Component Summary | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-12 Mental Components | ||||

| Mental Health | Social Functioning | Role/Emotional Functioning | ||

| No Cannabis Use Disorder | 51.9 (0.09) | 50.7 (0.10) | 48.5 (0.11) | 51.0 (0.08) |

| Any Cannabis Use Disorder | 46.7 (0.46)a | 46.8 (0.52) a | 44.3 (0.55) a | 45.3 (0.50) a |

| Mild Disorder | 48.2 (0.54) a | 48.0 (0.67) a | 45.4 (0.66) a | 46.9 (0.63) a |

| Moderate Disorder | 46.1 (0.95) a | 46.9 (0.91) a | 44.3 (0.88) a | 44.5 (0.92) a |

| Severe Disorder | 43.7 (0.98) a | 43.6 (1.15) a | 41.5 (1.12) a | 42.2 (0.95) a |

| Number of Cannabis Use Disorder Criteria | ||||

| 0 | 51.9 (0.09) | 50.8 (0.09) | 48.6 (0.12) | 51.1 (0.08) |

| 1 | 48.8 (0.51) a | 48.3 (0.47) a | 47.2 (0.45) b | 47.7 (0.49) a |

| 2 | 48.2 (0.72) a | 48.0 (0.82) b | 45.5 (0.80) a | 46.9 (0.80) a |

| 3 | 48.3 (0.89) a | 48.0 (0.95) a | 45.1 (0.93) a | 46.9 (0.87) a |

| 4 | 46.4 (1.06) a | 47.0 (1.11) b | 44.7 (1.18) b | 44.8 (1.03) a |

| 5 | 45.7 (1.61) a | 46.7 (1.58) b | 43.7 (1.40) a | 44.0 (1.61) a |

| 6 | 44.6 (2.23) b | 44.1 (2.42) b | 43.8 (2.04) c | 44.9 (1.66) a |

| 7 | 46.5 (1.31) a | 44.3 (2.06) b | 43.3 (2.23) c | 44.5 (1.80) b |

| 8 | 43.0 (2.26) a | 46.4 (2.04) c | 40.7 (1.80) a | 41.4 (1.76) a |

| 9 | 38.7 (2.22) a | 40.5 (3.09) b | 39.9 (1.82) a | 37.3 (2.21) a |

| 10 | 41.7 (2.44) a | 41.0 (5.30) | 33.9 (3.47) a | 36.9 (2.77) a |

| 11 | 44.9 (3.65) c | 38.9 (5.10) b | 37.0 (5.53) b | 37.4 (5.55) b |

Significantly different (p<.001) from score for individuals with no cannabis use disorder/zero cannabis use disorder criteria, after adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics.

Significantly different (p<.01) from score for individuals with no cannabis use disorder/zero cannabis use disorder criteria,, after adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics.

Significantly different (p<.05) from score for individuals with no cannabis use disorder/zero cannabis use disorder criteria,, after adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics.

Service utilization

Among respondents with 12-month and lifetime DSM-5 cannabis use disorders, 7.2% and 13.7% received any type of service for cannabis problems (Table 5). For 12-month disorders, service utilization rates were 4.1%, 6.0% and 15.7% for mild, moderate and severe disorders; lifetime rates were 7.3%, 11.7% and 24.3%. By type/source of intervention, individuals with 12-month cannabis use disorders were most likely to use physicians/other health care practitioners (4.8%), followed by 12-step groups (3.2%), and rehabilitation programs, outpatient clinics, inpatient facilities, family/social services or detoxification programs (range, 0.9%–1.5%). Other settings were utilized less. Individuals with lifetime cannabis use disorders were most likely to use 12-step groups (8.0%), followed by physicians/other health care practitioners (5.2%), and rehabilitation programs, outpatient clinics, inpatient facilities, family/social services or detoxification programs (range, 1.6%–5.0%). Other settings were used less. Across cannabis disorder severity levels, most-to-least commonly-used intervention sources were ordered similarly.

Table 5.

Cannabis-Specific Treatment/intervention Among Individuals with 12-Month and Lifetime Cannabis Use Disorder

| Treatment/intervention Setting | 12-Month Cannabis Use Disorder | Lifetime Cannabis Use Disorder | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any % (se) | Mild% (se) | Moderate% (se) | Severe% (se) | Any % (se) | Mild% (se) | Moderate% (se) | Severe% (se) | |

| 12-Step program | 3.17 (0.79) | 1.07 (0.45) | 3.79 (1.79) | 7.63 (2.90) | 7.98 (0.71) | 3.64 (0.64) | 7.10 (1.45) | 14.81 (1.69) |

| Family/social services | 0.86 (0.35) | 0.78 (0.48) | 0.36 (0.36) | 1.57 (1.05) | 1.96 (0.39) | 0.85 (0.31) | 1.44 (0.61) | 3.92 (0.98) |

| Detoxification | 1.04 (0.55) | 0.27 (0.27) | 0.15 (0.15) | 3.80 (2.30) | 2.66 (0.42) | 1.00 (0.33) | 1.87 (0.73) | 5.58 (1.05) |

| Other inpatient facility | 1.16 (0.55) | 0.12 (0.12) | 0.70 (0.56) | 4.16 (2.32) | 1.62 (0.32) | 0.36 (0.17) | 1.33 (0.50) | 3.62 (0.92) |

| Outpatient clinic | 1.46 (0.56) | 0.39 (0.29) | 0.71 (0.50) | 4.81 (2.31) | 3.98 (0.64) | 1.11 (0.43) | 3.09 (1.04) | 8.73 (1.33) |

| Rehabilitation program | 1.51 (0.59) | 0.54 (0.39) | 0.68 (0.47) | 4.70 (2.37) | 4.98 (0.56) | 2.17 (0.55) | 4.53 (1.19) | 9.32 (1.30) |

| Methadone maintenance | - | - | - | - | 0.02 (0.01) | - | - | 0.06 (0.05) |

| Emergency department | 0.04 (0.04) | - | - | - | 0.77 (0.21) | 0.35 (0.21) | 0.47 (0.35) | 1.59 (0.54) |

| Halfway house | 0.06 (0.06) | - | - | - | 0.58 (0.15) | 0.15 (0.13) | 0.11 (0.11) | 1.52 (0.44) |

| Crisis center | 0.23 (0.17) | - | - | - | 0.63 (0.20) | 0.25 (0.16) | 0.19 (0.16) | 1.49 (0.54) |

| Employee assistance program | - | - | - | - | 0.60 (0.19) | 0.56 (0.29) | 0.28 (0.28) | 0.89 (0.39) |

| Clergy | 0.70 (0.30) | - | 0.88 (0.64) | 2.21(1.16) | 1.46 (0.27) | 0.52 (0.28) | 1.71 (0.61) | 2.63 (0.60) |

| Physician/other health carepractitioners | 4.83 (1.24) | 2.96 (1.53) | 3.73 (2.42) | 10.50 (2.80) | 5.18 (0.59) | 2.78 (0.84) | 4.67 (1.38) | 8.96 (1.11) |

| Other | 0.64 (0.34) | 0.10 (0.10) | - | 2.63 (1.47) | 1.04 (0.26) | 0.66 (0.25) | 0.45 (0.27) | 1.98 (0.71) |

| Any treatment or intervention | 7.16 (1.35) | 4.14 (1.62) | 5.98 (2.49) | 15.73 (3.49) | 13.69 (0.86) | 7.26 (0.90) | 11.72 (1.86) | 24.27 (1.91) |

Note: -, Zero prevalence.

Discussion

Among U.S. adults in 2012–2013, the prevalence of DSM-5 12-month cannabis use disorder was 2.54%, representing ~5,982,000 Americans, and the lifetime prevalence was 6.27%, representing ~14,757,000 Americans. Corresponding DSM-IV 12-month and lifetime rates in NESARC-III, 2.9% and 11.7% (29), showed that a substantial increase occurred since the 2001–2002NESARC, in which the 12-month and lifetime rates were 1.5% and 8.5% (29), an increase apparently driven by greater prevalence of cannabis users (29).

The prevalence and odds of 12-month and lifetime cannabis use disorders were greater among men than women, consistent with earlier surveys (17, 50, 51).

In NESARC-III, the odds for 12-month cannabis use disorders were higher among younger than older age groups, with striking differences between those age 18–29 and those ≥45 (ORs=6.5–9.7). While the prevalence of cannabis use disorder increased across all age groups between the 2001–2002 NESARC and the 2012–2013 NESARC-III, the age differential in DSM-5 cannabis use disorder in NESARC-III is considerably more pronounced than in the NESARC (17). The general increases suggest the operation of a period effect, while the sharply increased age differential suggests an additional cohort effect in the youngest adults. The general increase plus the sharp age differential in NESARC-III for DSM-5 cannabis use disorder are consistent with similar time trends among those favoring legalization of marijuana for recreational use (52). These trends all appear to reflect different manifestations of the increasingly accepting social attitudes towards marijuana use.

The odds of cannabis use disorder varied by race/ethnic group. For 12-month and lifetime disorders, odds were lower for Asians/Pacific Islanders and Hispanics than whites, but higher in Native Americans, consistent with the NESARC (17). For blacks, odds of 12-month cannabis use disorders were significantly higher than whites, in contrast to NESARC, in which blacks did not differ from whites. For lifetime cannabis use disorder, the odds did not differ between blacks and whites in NESARC-III, while in NESARC, blacks had significantly lower odds of lifetime cannabis use disorder than whites (17). Thus, the risk in blacks relative to whites has increased over the past decade. This is consistent with notable increases in the prevalence of cannabis use and cannabis use disorders among blacks (29, 53–55). While reasons for this change are unclear, increasing economic disparity between blacks and whites since the 2008 economic recession (56, 57) may have exacerbated neighborhood factors (disorder, violence, visible drug dealing) that increase adolescent marijuana use (58), and may function similarly in adults, an issue warranting investigation. Blacks may also hold different attitudes towards marijuana than whites, possibly viewing it as a natural and therefore safe substance (22). This also warrants investigation.

Participants with the lowest incomes had higher odds of cannabis use disorder than others. Income disparities in distal and proximal form are related to cannabis outcomes, including early exposure to disadvantaged macroeconomic environments (59), low parental socioeconomic status as a moderator of the risk of family history of addiction (60), and current residence in high-unemployment neighborhoods (61). Cannabis disorders and concurrent economic disparity may be related if the stress of disadvantaged economic conditions leads to marijuana use as a coping mechanism, increasing the risk for cannabis use disorders among users with a vulnerability to such disorders. However, the relationship may be bi-directional, since early adolescent use of marijuana is associated with subsequent lower adult cognitive functioning (3–5), which could impair the chances for the educational and occupational achievement (6–8) that would bring higher incomes. This important yet complex relationship merits further study to inform policy and personal decisions regarding marijuana use.

Similar to NESARC findings (17), 12-month and lifetime cannabis use disorders were strongly and consistently associated with other substance and mental disorders. Thus, despite the increasingly normative nature of marijuana use and the increased adult prevalence of cannabis use disorders, those with cannabis use disorders continue to be vulnerable to other common mental disorders. In patient settings, those with drug and psychiatric disorders often exhibit more persistent, severe, and treatment-resistant symptoms than patients with drug disorders only (62). Research indicates that the best treatment for such comorbid conditions is concurrent treatment for both disorders (62). Therefore, study findings indicate an increased need for settings that provide evidence-based treatments for both conditions. Further, multivariable investigation indicates two latent transdiagnostic domains of comorbidity, the internalizing (INT) and externalizing (EXT) (63) domains. EXT is characterized by antisocial personality disorder and substance disorders; INT is characterized by distress (major depression, dysthymia, generalized anxiety) or fear (panic, social phobia, specific phobia). These domains have been replicated across gender and race/ethnic groups (64, 65). Given the changing legal and attitudinal climate in the U.S. regarding marijuana use, re-examining cannabis use disorders within this transdiagnostic framework is warranted to better understand its relationship to other substance and psychiatric disorders, and to inform the development of more effective treatments.

Participants with cannabis use disorders experienced considerable disability across different domains. The level of disability, particularly among those with severe disorders, was consistent with the very frequent cannabis use reported (252.2 and 310.4 days per year among those with 12-month and lifetime severe cannabis use disorders). These disability and use patterns attest to the severity of the disorder, which clearly is not a benign or harmless condition. Further, the disability levels were greater than the corresponding levels associated with alcohol use disorders in NESARC-III (38). Previous research suggests that even after cannabis use disorders remit, disability persists (66). Whether this persistence is mediated by prolonged cognitive impairments associated with early marijuana use (3–5), by aspects of the disorder itself (e.g., particular diagnostic criteria) or other factors warrants investigation.

Relatively few participants with cannabis use disorders received any type of services, a situation unimproved since NESARC (17). For alcohol use disorders, factors predicting lack of service use include viewing alcohol problems as stigmatized (67) or not serious (68), preference for self-reliance, and beliefs that treatment is ineffective (68). Similar factors appear related to lack of service use for cannabis disorders (31, 69), a topic warranting further investigation. Evidence-based treatments (70–72) are available for cannabis use disorders (33). Public and professional education about treatment efficacy and availability that destigmatizes helpseeking may encourage individuals with cannabis use disorders to seek treatment. Given the increased prevalence of these disorders among U.S. adults (27, 29), provision of such services and public education about treatment appears critically needed.

DSM-5 diagnoses of cannabis use disorders differed from DSM-IV by adding criteria for craving and cannabis withdrawal. Among participants with 12-month DSM-5 cannabis use disorder, 60.50% (SE=2.05) had craving for cannabis, 32.48% (SE=2.09) had cannabis withdrawal, and 23.06% (SE=1.84) had both. In NESARC-III, the prevalence of moderate to severe DSM-5 cannabis use disorder was higher than DSM-IV cannabis dependence, a difference attributed to the cannabis withdrawal criterion (73). Earlier studies showed how the craving and cannabis withdrawal criteria operate in the general population (36, 74, 75), e.g., model fit of cannabis disorder criteria improved after addition of withdrawal (76). While studies of DSM-5 cannabis use disorder in NESARC-III show good reliability and validity (44, 46), further nosological studies focused on craving and withdrawal should be conducted in NESARC-III data.

NESARC-III findings of increased rates of cannabis use disorder (29) are inconsistent with the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), which found stable prevalence of cannabis use disorder between 2002 and 2013 (77). However, the NESARC-III findings are consistent with other national indicators of increases in cannabis use disorders (27) and other serious cannabis-related problems, e.g., emergency room visits, fatal car crashes (11, 30). These increases are consistent with a changing landscape of increasingly permissive marijuana attitudes and laws. Changing laws may benefit society by reducing the harms of socially patterned drug arrests (78). However, the laws may affect public health adversely by leading to more marijuana users, including some vulnerable to cannabis use disorders. Continued surveillance of these trends is needed to monitor the balance of social costs and benefits, and treatment needs.

Lifetime rates of DSM-5 cannabis use disorder were highest in those aged 18–29. This could be artifactual due to recall failure for earlier disorders among older individuals (79). However, this report and others (17) show that risk for onset of cannabis use disorder peaks in late adolescence/early 20s, and remission often occurs within 3–4 years (17, 80). Given that, the finding of higher rates of lifetime disorders among those aged 18–29 may well be valid. Further studies are needed to address this issue.

Study limitations are noted. Only common psychiatric disorders were assessed. Some population segments were not included, e.g., prisoners, homeless, long-term inpatients. NESARC-III was also cross-sectional. Prospective surveys are needed to investigate the stability and causal directions of the relationships. The study also did not distinguish between associations explained by greater use of cannabis or greater risk of a disorder given such use; future studies should address this issue. NESARC-III also had important strengths, including a large sample, reliable and valid measures, and rigorous field methodology. NESARC-III is also unique in providing current, comprehensive information on DSM-5 cannabis use disorder and its correlates and comorbidity in the U.S. adult general population.

In summary, DSM-5 cannabis use disorder is a highly prevalent, comorbid, disabling disorder that often goes untreated. Numerous risk factors were identified that could stimulate further studies of differences in correlates of DSM-5 cannabis use disorder by sex, age and race/ethnicity, and inform additional hypothesis-driven studies. Most importantly, this study highlighted the urgency of identifying and implementing effective prevention methods. The study also highlights the need to educate the public, professionals and policymakers about the seriousness of cannabis use disorder, and for public health efforts to destigmatize and encourage help-seeking for cannabis use disorder among those who cannot reduce their use of marijuana on their own, despite substantial harm to themselves and others.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding Support/Role of Sponsors: The NESARC-III was sponsored by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), with supplemental support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Sponsors and funders of the NESARC-III had no role in the design and conducted of the study; collection, management analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review and approval of the manuscript.

Grant Support: Support is acknowledged from NIDA R01DA034244-01 and New York State Psychiatric Institute (Dr. Hasin); NIDA F32 DA036431 (Dr. Kerridge); and from the intramural program, NIAAA, NIH.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: No conflicts of interest declared by any author.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views of any of the sponsoring organizations or agencies or the US government.

References

- 1.Volkow ND, Baler RD, Compton WM, et al. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2219–2227. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1402309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall W. The adverse health effects of cannabis use: what are they, and what are their implications for policy? Int J Drug Policy. 2009;20:458–466. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meier MH, Caspi A, Ambler A, et al. Persistent cannabis users show neuropsychological decline from childhood to midlife. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E2657–2664. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206820109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Renard J, Krebs MO, Jay TM, et al. Long-term cognitive impairments induced by chronic cannabinoid exposure during adolescence in rats: a strain comparison. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2013;225:781–790. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2865-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Shea M, McGregor IS, Mallet PE. Repeated cannabinoid exposure during perinatal, adolescent or early adult ages produces similar longlasting deficits in object recognition and reduced social interaction in rats. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20:611–621. doi: 10.1177/0269881106065188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lynskey M, Hall W. The effects of adolescent cannabis use on educational attainment: a review. Addiction. 2000;95:1621–1630. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.951116213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. (HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14–4863) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Compton WM, Gfroerer J, Conway KP, et al. Unemployment and substance outcomes in the United States 2002–2010. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;142:350–353. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lenne MG, Dietze PM, Triggs TJ, et al. The effects of cannabis and alcohol on simulated arterial driving: Influences of driving experience and task demand. Accid Anal Prev. 2010;42:859–866. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartman RL, Huestis MA. Cannabis effects on driving skills. Clin Chem. 2013;59:478–492. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2012.194381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brady JE, Li G. Trends in alcohol and other drugs detected in fatally injured drivers in the United States, 1999–2010. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;179:692–699. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramaekers JG, Berghaus G, van Laar M, et al. Dose related risk of motor vehicle crashes after cannabis use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;73:109–119. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartman RL, Brown TL, Milavetzd G, et al. Cannabis Effects on Driving Lateral Control With and Without Alcohol. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.06.015. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2011: National Estimates of Drug-Related Emergency Department Visits. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2013. (HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13–4760) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis GP, Compton MT, Wang S, et al. Association between cannabis use, psychosis, and schizotypal personality disorder: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Schizophr Res. 2013;151:197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Di Forti M, Marconi A, Carra E, et al. Proportion of patients in south London with first-episode psychosis attributable to use of high potency cannabis: a case-control study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2:233–238. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stinson FS, Ruan WJ, Pickering R, et al. Cannabis use disorders in the USA: prevalence, correlates and co-morbidity. Psychol Med. 2006;36:1447–1460. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lev-Ran S, Imtiaz S, Taylor BJ, et al. Gender differences in health-related quality of life among cannabis users: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;123:190–200. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Secades-Villa R, Garcia-Rodriguez O, Jin CJ, et al. Probability and predictors of the cannabis gateway effect: a national study. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26:135–142. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Monitoring the Future. Data Tables and Figures. Ann Arbor, MI: NAHDAP/ICPSR, The University of Michigan; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berg CJ, Stratton E, Schauer GL, et al. Perceived harm, addictiveness, and social acceptability of tobacco products and marijuana among young adults: marijuana, hookah, and electronic cigarettes win. Subst Use Misuse. 2015;50:79–89. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2014.958857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sinclair CF, Foushee HR, Scarinci I, et al. Perceptions of harm to health from cigarettes, blunts, and marijuana among young adult African American men. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24:1266–1275. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2013.0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gallup. Majority Continues to Support Pot Legalization in US. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cerda M, Wall M, Keyes KM, et al. Medical marijuana laws in 50 states: investigating the relationship between state legalization of medical marijuana and marijuana use, abuse and dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;120:22–27. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wall MM, Poh E, Cerda M, et al. Adolescent marijuana use from 2002 to 2008: higher in states with medical marijuana laws, cause still unclear. Ann Epidemiol. 2011;21:714–716. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hasin DS, Wall M, Keyes KM, et al. Medical marijuana laws and adolescent marijuana use in the USA from 1991 to 2014: results from annual, repeated cross-sectional surveys. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2:601–608. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00217-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonn-Miller MO, Harris AH, Trafton JA. Prevalence of cannabis use disorder diagnoses among veterans in 2002, 2008, and 2009. Psychol Serv. 2012;9:404–416. doi: 10.1037/a0027622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Compton WM, Grant BF, Colliver JD, et al. Prevalence of marijuana use disorders in the United States: 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. JAMA. 2004;291:2114–2121. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.17.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hasin DS, Saha TD, Kerridge BT, et al. Marijuana use disorders in the United States between 2001–2002 and 2012–2013. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1858. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2011: National Estimates of Drug-Related Emergency Department Visits. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2013. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13–4760. DAWN Series D-39. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khan SS, Secades-Villa R, Okuda M, et al. Gender differences in cannabis use disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;130:101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Conway KP, Compton W, Stinson FS, et al. Lifetime comorbidity of DSM-IV mood and anxiety disorders and specific drug use disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:247–257. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Copeland J, Clement N, Swift W. Cannabis use, harms and the management of cannabis use disorder. Neuropsychiatry. 2014;4:55–63. [Google Scholar]

- 34.van der Pol P, Liebregts N, de Graaf R, et al. Mental health differences between frequent cannabis users with and without dependence and the general population. Addiction. 2013;108:1459–1469. doi: 10.1111/add.12196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hasin DS, O’Brien CP, Auriacombe M, et al. DSM-5 criteria for substance use disorders: recommendations and rationale. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:834–851. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12060782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grant BF, Amsbary M, Chu A, et al. Source and Accuracy Statement: National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III (NESARC-III) Rockville, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder: Results From the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:757–766. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bureau of the Census. American Community Survey, 2012. Suitland, MD: Bureau of the Census; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. (HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14–4863) [Google Scholar]

- 41.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Summary Health Statistics for US Adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2012. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, et al. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition Version (AUDADIS-5) Rockville, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grant BF, Harford TC, Dawson DA, et al. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview schedule (AUDADIS): reliability of alcohol and drug modules in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1995;39:37–44. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01134-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Smith SM, et al. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-5 (AUDADIS-5): reliability of substance use and psychiatric disorder modules in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;148:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hasin DS, Aivadyan C, Greenstein E, et al. Psychiatric Research Interview for Substance Use and Mental Disorders, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (PRISM-5) Version. New York, NY: Columbia University, Department of Psychiatry; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hasin DS, Greenstein E, Aivadyan C, et al. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-5 (AUDADIS-5): procedural validity of substance use disorders modules through clinical re-appraisal in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;148:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hasin DS, Shmulewitz D, Stohl M, et al. Procedural validity of the AUDADIS-5 depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder modules: Substance abusers and others in the general population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;152:246–256. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gandek B, Ware JE, Jr, Aaronson NK, et al. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability of the SF-36 in eleven countries: results from the IQOLA Project. International Quality of Life Assessment. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1149–1158. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00106-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN Language Manual, Release 11.0. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haberstick BC, Young SE, Zeiger JS, et al. Prevalence and correlates of alcohol and cannabis use disorders in the United States: results from the national longitudinal study of adolescent health. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;136:158–161. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Teesson M, Slade T, Swift W, et al. Prevalence, correlates and comorbidity of DSM-IV Cannabis Use and Cannabis Use Disorders in Australia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2012;46:1182–1192. doi: 10.1177/0004867412460591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Motel S. FactTank: News in the Numbers. Pew Research Center; Apr 14, 2015. 6 facts about marijuana. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance - United States, 2011. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2012;61:1–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, et al. Monitoring the Future national results on drug use: 2012 Overview, Key Findings on Adolescent Drug Use. Ann Arbor: Institute of Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: summary of national findings. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2013. (HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13–4795) [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kochhar R, Fry R, Taylor P. Social & Demographic Trends. Pew Researcg Center; Jul 26, 2011. Wealth Gaps Rise to Record Highs Between Whites, Blacks, Hispanics. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kochhar R, Fry R. FactTank: News in the Numbers. Pew Research Center; Dec 12, 2014. Wealth inequality has widened along racial, ethnic lines since end of Great Recession. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reboussin BA, Green KM, Milam AJ, et al. Neighborhood environment and urban African American marijuana use during high school. J Urban Health. 2014;91:1189–1201. doi: 10.1007/s11524-014-9909-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ramanathan S, Balasubramanian N, Krishnadas R. Macroeconomic environment during infancy as a possible risk factor for adolescent behavioral problems. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:218–225. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Melchior M, Choquet M, Le Strat Y, et al. Parental alcohol dependence, socioeconomic disadvantage and alcohol and cannabis dependence among young adults in the community. Eur Psychiatry. 2011;26:13–17. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tucker JS, Pollard MS, de la Haye K, et al. Neighborhood characteristics and the initiation of marijuana use and binge drinking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;128:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.National Institute on Drug Abuse. Comorbidity: Addiction and Other Mental Illnesses. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. (NIH Publication Number 10–5771) [Google Scholar]

- 63.Krueger RF. The structure of common mental disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:921–926. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Eaton NR, Keyes KM, Krueger RF, et al. An invariant dimensional liability model of gender differences in mental disorder prevalence: evidence from a national sample. J Abnorm Psychol. 2012;121:282–288. doi: 10.1037/a0024780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Eaton NR, Keyes KM, Krueger RF, et al. Ethnicity and psychiatric comorbidity in a national sample: evidence for latent comorbidity factor invariance and connections with disorder prevalence. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48:701–710. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0595-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rubio JM, Olfson M, Villegas L, et al. Quality of life following remission of mental disorders: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74:e445–450. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m08269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Keyes KM, Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, et al. Stigma and treatment for alcohol disorders in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172:1364–1372. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cohen E, Feinn R, Arias A, et al. Alcohol treatment utilization: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;86:214–221. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.van der Pol P, Liebregts N, de Graaf R, et al. Facilitators and barriers in treatment seeking for cannabis dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;133:776–780. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dutra L, Stathopoulou G, Basden SL, et al. A meta-analytic review of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:179–187. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Danovitch I, Gorelick DA. State of the art treatments for cannabis dependence. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2012;35:309–326. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Marshall K, Gowing L, Ali R, et al. Pharmacotherapies for cannabis dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;12:CD008940. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008940.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Smith SM, et al. Nosologic Comparisons of DSM-IV and DSM-5 Alcohol and Drug Use Disorders: Results From the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2015;76:378–388. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Compton WM, Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, et al. Crosswalk between DSM-IV dependence and DSM-5 substance use disorders for opioids, cannabis, cocaine and alcohol. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132:387–390. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hasin DS, Keyes KM, Alderson D, et al. Cannabis withdrawal in the United States: results from NESARC. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:1354–1363. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Agrawal A, Lynskey MT. Does gender contribute to heterogeneity in criteria for cannabis abuse and dependence? Results from the national epidemiological survey on alcohol and related conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88:300–307. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.SAMHSA. Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. (HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14–4863) [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mitchell O, Caudy MS. Examining racial disparities in drug arrests. Justice Quarterly. 2015;32:288–313. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Taylor A, et al. How common are common mental disorders? Evidence that lifetime prevalence rates are doubled by prospective versus retrospective ascertainment. Psychol Med. 2010;40:899–909. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Feingold D, Fox J, Rehm J, et al. Natural outcome of cannabis use disorder: a 3-year longitudinal follow-up. Addiction. 2015 Jul 25; doi: 10.1111/add.13071. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.