Abstract

Background

The United States has a large community supervision population, a growing number of whom are women. Trichomonas vaginalis infection is strongly associated with an increased risk of HIV acquisition and transmission, particularly among women, but there is a paucity of research on HIV and T. vaginalis co-infection among women under community supervision.

Methods

This paper examines the prevalence of T. vaginalis infection and T. vaginalis and HIV co-infection at baseline among women under community supervision in New York City. It also examines the 12-month outcomes of women treated for T. vaginalis. Women received biological tests for HIV and T. vaginalis at baseline and 12 months follow-up.

Results

Of the 333 women tested for sexually transmitted infections, 77 women (23.1%) tested positive for T. vaginalis at baseline and 44 (13.3%) were HIV positive. HIV-positive women had significantly higher rates of T. vaginalis infection than HIV-negative women (36.4% vs. 21.3%, p≤0.05). Sixteen women (4.8%) were co-infected with T. vaginalis and HIV. Of the 77 women who were positive for T. vaginalis infection at baseline, 58 (75.3%) received treatment by a healthcare provider. Of those who received treatment, 17 (29.3%) tested positive for T. vaginalis at the 12 month follow-up.

Conclusions

Given the high prevalence of T. vaginalis among this sample of women, particularly among HIV positive women, and high levels of reinfection or persistent infection, screening for T. vaginalis among women under community supervision may have a substantial impact on reducing HIV acquisition and transmission among this high risk population.

Keywords: T. vaginalis, HIV, women, community supervision, trichomoniasis

Short Summary

A study of women under community supervision found higher rates of T. vaginalis infection among HIV-positive women than among HIV-negative women.

INTRODUCTION

In 2014, an estimated 4.7 million adults (or about 1 in 52 US adult residents) were under community supervision (which can include individuals on probation or parole, in community courts, or in alternative to incarceration programs) and approximately 25% of individuals under community supervision were female, up from 22% in 2000.1 Women under community supervision are disproportionately black and socioeconomically disadvantaged2 and bear a disproportionately high HIV and STI burden.3 They are at increased risk for HIV and STI acquisition, as they have been found to engage in higher levels of injection drug use and unprotected sex than men under community supervision.4 Despite their increased risk, they are rarely tested for HIV or STIs. It is estimated that only 18% of individuals in the U.S. community corrections system receive HIV screening and just 0.02% receive STI testing.5 Furthermore, few studies have examined rates of HIV and STIs among this large high-risk population, and many used less-reliable data measures, such as self-reported survey data rather than biological testing.2 Given the sheer number of women under community supervision and their elevated risk for HIV and STIs, this lack of data represents a substantial gap in public health knowledge.

Women are often more adversely affected by STIs than men and are particularly in need of STI screening. For example, chronic genital chlamydia infection in women can lead to pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), infertility and ectopic pregnancy, but reproductive outcomes in men are comparatively minor.6 Human papillomavirus (HPV) can result in cancer, particularly cervical cancer in women, but the occurrence of HPV-related cancers in men is much less frequent.7 Likewise, prolonged T. vaginalis infection in women can result in PID, pre-term delivery, and low birth weight, but men rarely experience consequences of infection.8

T. vaginalis infection is the most prevalent curable STI in the United States and the world (affecting approximately 276 million people a year), with prevalence rates higher than both C. trachomatis and N. gonorrheae combined.9 Unlike infections with C. trachomatis and N. gonorrheae, however, trichomoniasis is not classified as a notifiable disease in the United States and receives little public health attention. Though often discounted as an infection with few consequences, if left untreated, T. vaginalis infection can result in a host of adverse reproductive health outcomes, such as pregnancy complications and PID.10,11 Furthermore, it is also associated with increased risk for HIV transmission and acquisition.12,13 Quinlivan et al. estimated that 23% of HIV transmission events from HIV-infected women may be attributable to T. vaginalis infection when 22% of women are co-infected with T. vaginalis (a rate not uncommon among high-risk populations), thus suggesting the importance of T. vaginalis control among HIV positive women.14 Another study found that, in the US, 747 new HIV cases in women a year are a result of the facilitative effects of T. vaginalis infection on the transmission of HIV.15 Although research has indicated that effective T. vaginalis control may reduce HIV transmission and acquisition,16 the infection is asymptomatic in the majority of cases,17 so it is rarely screened for and often remains untreated.18

T. vaginalis infection has a much higher prevalence among black women than women of other racial and ethnic backgrounds.13 In the United States, a population-based study revealed an overall prevalence of 3.1% among women aged 14–49 years, with rates as high as 13.3% among black women.17 A study in Baltimore showed that 1 in 7 black women were found to be infected with T. vaginalis (estimated prevalence 14.2%).19 Another study found that black women had T. vaginalis rates that were ten times higher than white women, constituting a significant health disparity.17 Unlike other STIs, T. vaginalis infection disproportionately affects older women,18 who are also overrepresented in the criminal justice system. A national profile shows that women in the criminal justice system are typically in their early to mid-thirties.20 Given the adverse reproductive effects of this parasite and its ability to facilitate the acquisition and transmission of HIV, it is imperative that this major health disparity gap for a population as high-risk as older black women under community supervision be addressed. T. vaginalis infection can be screened for outside of clinical settings (such as at a community supervision facility) by nucleic acid amplification testing from a self-collected vaginal swab and it is easily treated (often with only a single dose of metronidazole). Thus, providing regular screenings and adequate treatment among women under community supervision may be a relatively simple public health solution that could greatly reduce the morbidity of this infection.

This paper (1) assesses HIV and T. vaginalis prevalence and co-infection using biological data among women under community supervision in New York City, and (2) examines treatment outcomes at the 12 month follow-up among women who were positive for T. vaginalis at baseline.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design and Study Population

We used data from a randomized controlled trial testing the efficacy of a behavioral HIV/STI intervention (WORTH) among drug-involved women in the community corrections system.21 Women were randomized into three arms: two intervention arms and a control arm. We used biological STI data from the baseline assessment and the 12 month follow-up interview. A total of 1,104 women were screened from community courts and probation sites in New York City. Of these, 337 women completed informed consent and baseline interviews, 306 were randomized into the study arms, and 278 women completed the 12 month assessment. To be eligible for inclusion, women had to be 1) 18 years of age or older, 2) under community supervision in a community or criminal court, on probation or parole, under drug treatment court supervision or another alternative to incarceration program (such as family court programs) within the past 90 days, 3) report one or more incidents of illicit drug use within six months, 4) have one or more incidents of unprotected vaginal or anal intercourse within the past 90 days, and 5) be HIV positive or at risk for HIV/STIs. Data were collected at community supervision sites throughout New York City. Trained staff administered surveys at baseline, and three month, six month and 12 month follow-up periods. Biological HIV and STI tests were completed at baseline and 12 month follow-up. Participants were reimbursed for completing assessments and intervention sessions, up to a maximum of $265 for the completion of all assessments, intervention sessions, and testing. All participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study. This study was approved by institutional review boards at Columbia University and the Center for Court Innovation.

Measures

At baseline and during each of the follow-up periods, women completed a computer-assisted self-administered interview (CASI) approximately an hour and a half in length. This interview elicited detailed information on sociodemographic characteristics (age, ethnicity, marital status, education level, employment status, monthly income, and location of residency), incarceration history, alcohol and substance use history, sexual behaviors, and sexual partner characteristics.

Diagnosis of HIV and STIs, treatment, and follow-up

HIV biological testing

Oral swabs were collected from participants at baseline and 12 month follow-up to test for the presence of HIV-1 and HIV-2 antibodies using the OraQuick ADVANCE Rapid HIV Test.

STI biological testing

Women obtained a self-collected vaginal swab during their visit at both the baseline and 12-month follow-up sessions to test for T. vaginalis, C. trachomatis, and N. gonorrhoeae. Specimens were collected Monday through Thursday and shipped twice weekly (on Tuesdays and Thursdays). After the specimens were collected, they were logged and refrigerated immediately. Specimens were then packaged for shipment and transported on ice packs to the clinical laboratory at Emory University via FedEx priority overnight, morning delivery, where they were immediately incubated and refrigerated at 2–8°C. Lab tests were conducted sometime between the same day of arrival up to five days after arrival. Specimens were tested for T. vaginalis using the Taq-Man PCR assay, developed and validated by the Caliendo Laboratory at Emory University.22 The limit of detection for this assay is <0.2 organisms per reaction or 40 copies per ml. The sensitivity and specificity of the TV assay is 100% and 99.6%.22 C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhea were tested for using the Becton Dickinson Probe ET Amplified DNA Assay (Becton, Dickinson and Co, Sparks, Maryland).

Participants with positive HIV/STI test results received risk-reduction counseling from the Clinical Research Coordinator (CRC) and were encouraged to inform their partners and have their partner treated simultaneously. All women who tested positive for an STI were referred by the CRC to a physician for the appropriate treatment and provided the CRC with forms completed by their medical providers to verify treatment. All women were retested for STIs at the 12 month follow-up assessment and all HIV-negative women were retested for HIV.

T. vaginalis treatment outcomes at 12 months

We followed all women who were infected with T. vaginalis infection at baseline and determined 1) whether they received treatment for T. vaginalis infection or not, 2) whether they tested positive for T. vaginalis infection at the 12 month follow-up assessment, and 3) the incident infections of T. vaginalis at the 12 month follow-up assessment. Treatment costs were covered by the participants’ insurance or by study funds for participants who had no insurance.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the sample. We used chi-square tests to compare significant differences in STIs between HIV positive and HIV negative individuals. Individuals who had missing data were excluded from the analysis. Out of 337 women who completed baseline interviews, four were excluded because they did not provide vaginal swabs for STI testing, so 333 women were retained for analysis in this paper. In the chi-square test examining T. vaginalis among HIV positive and negative individuals, an additional two women were excluded because they refused an HIV test. Descriptive statistics were conducted to illustrate treatment outcomes of T. vaginalis infection. All analyses were conducted using SPSS 23 (Durham, NC).

RESULTS

Sociodemographic characteristics

Table 1 provides information on the main demographic characteristics of the sample. The mean age was 41.3 years, with participants ranging in age from 18–62 years (interquartile range, 33–49 years). Almost three-quarters of women identified as black or African American (71.2%). Most women were unemployed (91.0%) and had a high school education or less (73.6%). The majority of women were highly impoverished. Over half (57.2%) of the women surveyed made less than $400 a month and over a quarter (29.4%) made between $401-$850 a month. The majority of women were single (67.0%). Women who were black/African American were significantly more likely to be infected with T. vaginalis than women who were not black/African American (p≤0.05). There were no other sociodemographic differences between women who were infected with T. vaginalis and women who were not.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of women under community supervision in New York City, 2009–2011 (N=333)

| Overall N=333 |

Positive for T. vaginalis N=77 |

Negative for T. vaginalis N=256 |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 41.3 (10.5) | 40.9 (9.56) | 41.4 (10.76) | .707 |

| Race/Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| Black/African American | 237 (71.2%) | 62 (80.5%) | 175 (68.4%) | .039 |

| Not black/African American | 96 (28.8%) | 15 (19.5%) | 81 (31.6%) | |

| Education | ||||

| High school or less | 245 (73.6%) | 61 (79.2%) | 184 (71.9%) | .200 |

| Some college or more | 88 (26.4%) | 16 (20.8%) | 72 (28.1%) | |

| Employment status | ||||

| Unemployed | 303 (91.0%) | 73 (94.8%) | 230 (89.8%) | .324 |

| Occasional or seasonal | 6 (1.8%) | 2 (2.6%) | 4 (1.6%) | |

| Part-time | 13 (3.9%) | 1 (1.3%) | 12 (4.7%) | |

| Full-time | 11 (3.3%) | 1 (1.3%) | 10 (3.9%) | |

| Monthly income | ||||

| Less than $400 per month | 192 (57.7%) | 51 (66.2%) | 141 (55.1%) | .156 |

| $400–850 per month | 98 (29.4%) | 20 (26.0%) | 78 (30.5%) | |

| $851 or higher per month | 43 (12.9%) | 6 (7.8%) | 37 (14.5%) | |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Single, never married | 223 (67.0%) | 54 (70.1%) | 169 (66.0%) | .796 |

| Married | 52 (15.6%) | 11 (14.3%) | 41 (16.0%) | |

| Divorced/Separated/Widowed | 58 (17.4%) | 12 (15.6%) | 46 (18.0%) | |

HIV/STI prevalence and co-infections

Baseline prevalence of STI infections are shown in Table 2. The rate of C. trachomatis infection was 3.0% (n=10) and N. gonorrheae was 1.2% (n=4). Nearly a quarter of participants tested positive for T. vaginalis infection (23.1%, n=77). Of the 331 women tested both for STIs and HIV, 44 (13.3%) were HIV positive. Sixteen women (4.8%) were co-infected with T. vaginalis and HIV. Rates of T. vaginalis infection were found to be significantly higher among HIV positive women than among HIV negative women (36.4% vs. 21.3%, p≤0.05). Other co-infections included one participant diagnosed with both T. vaginalis and N. gonorrheae (0.3%) and one participant diagnosed with both C. trachomatis and N. gonorrheae (0.3%). No HIV positive participants were diagnosed with C. trachomatis or N. gonorrheae. Among the 77 women who tested positive for T. vaginalis infection at baseline, only two (2.6%) had been previously tested in the past 90 days.

Table 2.

Baseline prevalence of STIs and chi-square analysis among HIV positive and HIV negative women in the community corrections system in New York City, 2009–2011 (N=333 women with STI test results; N=331 women with both STI and HIV test results)

| Overall, N=333 |

HIV positive, N=44 |

HIV negative, N=287 |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. trachomatis | 10 (3.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 10 (3.5%) | .370 |

| N. gonorrhoeae | 4 (1.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (1.4%) | 1.00 |

| T. vaginalis | 77 (23.1%) | 16 (36.4%) | 61 (21.3%) | .027 |

T. vaginalis treatment

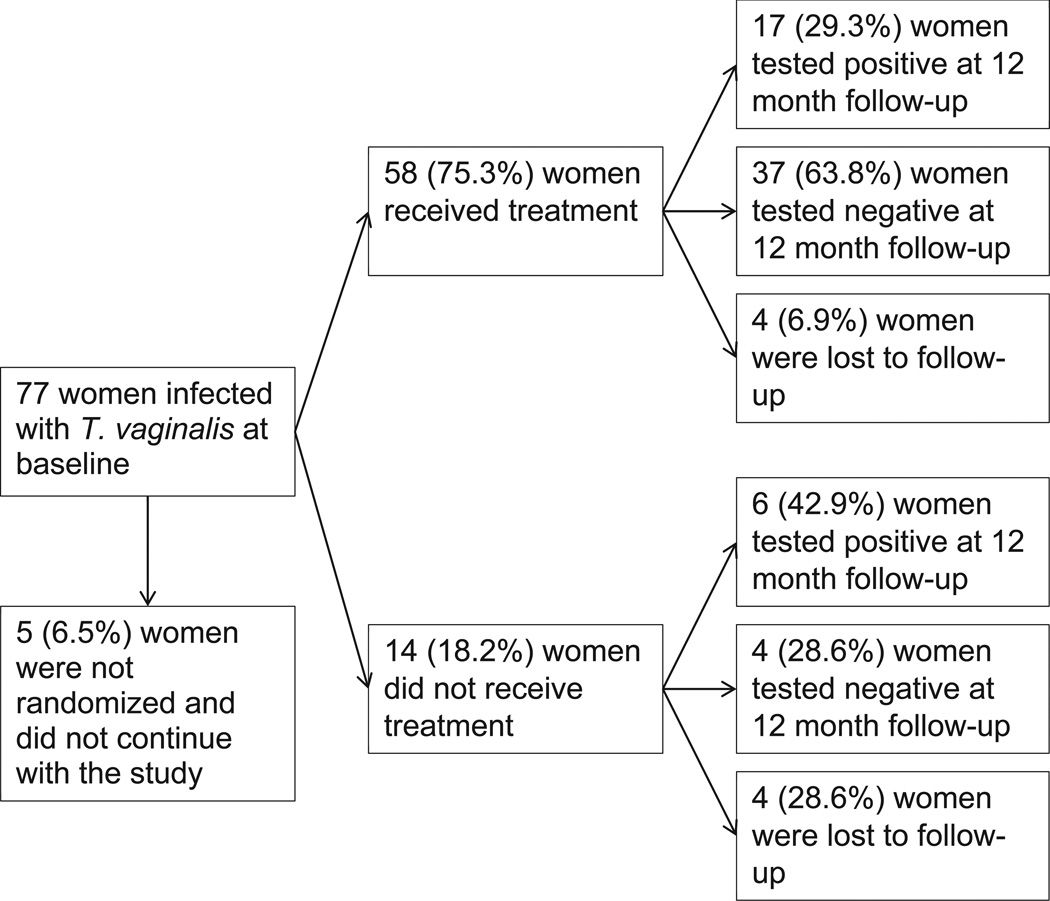

Of the 77 women infected with T. vaginalis at baseline (see Figure 1), 5 (6.5%) women were not randomized into a study arm and did not continue with the study, 58 (75.3%) women received treatment for T. vaginalis infection, and 14 (18.2%) women did not receive treatment for T. vaginalis infection. Of those who were treated, over a quarter (29.3%) tested positive for T. vaginalis at the 12 month follow-up assessment. Of those who were not treated for T. vaginalis infection at baseline, nearly half (42.9%) tested positive for T. vaginalis at the 12 month follow-up. There were no significant differences in treatment outcomes between women who were HIV positive and those who were HIV negative. Among the 206 women not infected with T. vaginalis at baseline and retained through the 12 month follow-up period, 25 developed new T. vaginalis infections, with an overall incidence rate of 12.1 per 100 person-years. We did not find any significant differences in T. vaginalis prevalence or treatment outcomes between women in the three study arms.

Figure 1.

T. vaginalis treatment flowchart

DISCUSSION

Our findings showed a high rate of T. vaginalis infection among this sample of women under community supervision, particularly among HIV-positive women. At the baseline assessment, over a third of HIV-positive women were infected with T. vaginalis, as opposed to approximately a fifth of HIV-negative women. These results highlight the importance of effective T. vaginalis control among populations that also have a high prevalence of HIV infection, such as women under community supervision. Research has shown that T. vaginalis infection is associated with increased HIV acquisition and transmission.13 In a longitudinal study among African women, Van Der Pol et. al found that the adjusted odds ratio for HIV acquisition was 2.74 for T. vaginalis positive cases.12 Other studies have also indicated that T. vaginalis infection significantly contributes to HIV acquisition and transmission in the U.S.14,15

Though this paper was not designed to examine the contributing effects of T. vaginalis infection on HIV acquisition and transmission, these results illustrate the high burden of T. vaginalis infection among HIV-positive women under community supervision. Other studies among women involved in the criminal justice system have also found a high prevalence of T. vaginalis infection (26.0% in the Northeast/Midwest and 52.6% in Indianapolis),23,24 indicating that targeted screening among this population would be beneficial. The vast majority of women in our study had not been previously screened for T. vaginalis infection and thus, had not been linked to treatment. Effective treatment of T. vaginalis has been shown to reduce HIV genital shedding beyond ART provision,16 and therefore, may reduce HIV transmission. Furthermore, research indicates that annual T. vaginalis screening and treatment for HIV-positive women would result in a lifetime savings of $553 per woman in the prevention of new HIV infections to susceptible partners (approximately $159,264,000 total saved annually).25 Thus, T. vaginalis screening and treatment programs among populations that bear a high burden of HIV and T. vaginalis infection, such as women under community supervision, may be a cost-effective way of reducing HIV transmission. Increased partnerships between public health and criminal justice systems may be one way to expand STI screening and treatment to better reach vulnerable populations. Though STI testing in community supervision settings is not common, a study from Indianapolis indicated that community court-based STI screening programs can be an effective way to increase STI testing and linkage to care among individuals under community supervision.26 The expansion of such programs into community supervision settings in NYC and other areas in the US could serve to increase the detection and treatment of T. vaginalis infection.

Consistent with other studies,27,28 our findings indicated that untreated T. vaginalis infection may persist for extended periods of time (up to 12 months). Nearly half of participants in our study who did not receive treatment at baseline were infected with T. vaginalis at the 12 month follow-up assessment. The proportion of women who were positive at 12 months was not statistically significantly different among those who were and were not treated at baseline, indicating a need for regular T. vaginalis screenings and follow-up among both those who have and have not previously received treatment. Though we are unable to determine whether positive results at 12 months are persistent infections or reinfections, the outcomes of persistent or repeated T. vaginalis infection can be severe. Prolonged infection with T. vaginalis can result in a range of adverse reproductive health sequelae, including PID, preterm delivery, low birth weight, and, in rare instances, respiratory infections in neonates.10,11,29 T. vaginalis infections are often asymptomatic,30 and therefore, routine screening and timely linkage to effective treatment are needed to reduce negative outcomes. Targeted efforts to increase both may be warranted for this at-risk population.

Even after receiving treatment for T. vaginalis infection at baseline, nearly 30% of women in our study were found to be infected with T. vaginalis 12 months later. The source of these repeat infections is unclear. Possible sources of repeat positives after treatment are reinfection from an untreated baseline partner, infection from a new partner, or treatment failure. Though women were encouraged to have their partner screened and treated for T. vaginalis, we did not verify partner treatment. Partner referral methods for STI testing and treatment are limited in effectiveness,18 and it is probable that few of these women’s partners were actually screened and treated for T. vaginalis infection. It is also possible that some women may have been infected by a new partner. Over half of the women in our study had multiple sex partners. Treatment failure may be another cause of a repeat positive. Treatment of T. vaginalis with a single 2g dose of metronidazole is the standard of care for HIV negative women (500 mg twice a day for 7 days for HIV positive women),28 but it is imperfect. Previous studies have found high repeat infection rates (8–20%) among women receiving a 2g dose of metronidazole, indicating that a single dose of metronidazole may be insufficient in some cases.31–33 Regardless of the reason for a repeat positive, these findings highlight the need for regular rescreening, effective treatment regimens and partner treatment strategies.

The data have a number of limitations that should be considered. First, although we had participants return signed forms from the doctor stating that they were treated for T. vaginalis infection, we did not have them return the prescription bottles, so we cannot ensure that they actually received or took the prescription. Second, we did not re-test women treated for T. vaginalis infection immediately post-treatment; thus, we were unable to distinguish reinfection from persistent infection or treatment failure. Third, although we encouraged women to have their partners screened and treated for T. vaginalis infection, we did not verify partner testing and treatment. Finally, these data were obtained from a convenience sample of drug using women under community supervision in New York City; thus, our findings may not be generalizable to broader populations or community supervision populations in other geographical settings.

T. vaginalis infection is an important STI that can result in severe reproductive health outcomes and has the potential to amplify the acquisition and transmission of HIV. T. vaginalis infection has been shown to disproportionately affect black women from low socioeconomic backgrounds, a demographic group that is also disproportionately represented in community supervision settings and has a high burden of HIV. Despite a growing body of research demonstrating its importance, T. vaginalis continues to be largely ignored in public health discourse, perhaps because of the demographic of individuals most affected by this pathogen. Targeted screening among high risk populations most affected by this infection, such as women in community supervision settings and their partners, may greatly improve T. vaginalis control. Without specific screening mandates and targeted funding, T. vaginalis infection will continue to place disadvantaged women at increased risk for adverse reproductive health outcomes and facilitate the acquisition and transmission of HIV infection.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the assistance of the Center for Court Innovation and the New York City Department of Probation for supporting the implementation of this study, and want to particularly thank the women who participated in this study.

FUNDING

This study was funded by the National Institute of Drug Abuse (grant #R01DA025878). Dr. Davis is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (T32 grant #MH019139 and P30 grant #MH043520) and Dr. Dasgupta is supported by the National Institute of Drug Abuse (T32 grant #DA037801).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest exist.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bureau of Justice Statistics. Adults Under Community Supervision Declined in 2014. 2015. For the Seventh Consecutive Year U.S. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larney S, Hado S, McKenzie M, Rich J. Unknown Quantities: HIV, Viral Hepatitis, and Sexually Transmitted Infections in Community Corrections. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2014;41:283. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Among African Americans. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belenko S, Langley S, Crimmins S, Chaple M. HIV Risk Behaviors, Knowledge, and Prevention Education Among Offenders under Community Supervision: A Hidden Risk Group. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2004;16:367–385. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.4.367.40394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cropsey K, Binswanger I, Clark C, Taxman F. The unmet medical needs of correctional populations in the United States. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2012;104:487–492. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30214-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marrazzo J. Enhancing Women's Sexual Health: Prevention Measures in Diverse Populations of Women. In: Aral S, Fenton K, Lipshutz J, editors. The New Public Health and STD/HIV Prevention: Personal, Public and Health Systems Approaches. New York: Springer Science+Business Media; 2013. pp. 197–218. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parkin D, Bray F. Chapter 2: The burden of HPV-related cancers. Vaccine. 2006;24:S11–S25. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.05.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Der Pol B. Trichomonas vaginalis Infection: The Most Prevalent Nonviral Sexually Transmitted Infection Receives the Least Public Health Attention. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2007;44 doi: 10.1086/509934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Global prevalence and incidence of selected curable sexually transmitted infections. Geneva: WHO; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silver B, Guy R, Kaldor J, Jamil M, Rumbold A. Trichomonas Vaginalis as a cause of perinatal morbidity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2014;41:369–376. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moodley P, Wilkinson D, Connolly C, Moodley J, Sturm A. Trichomonas vaginalis is associated with pelvic inflammatory disease in women infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2002;34:519–522. doi: 10.1086/338399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Der Pol B, Kwok C, Pierre-Louis B, et al. Trichomonas vaginalis infection and human immunodeficieincy virus acquisition in African women. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2008;197:548–554. doi: 10.1086/526496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kissinger P, Adamski A. Trichomoniasis and HIV interactions: a review. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2013;89:426–433. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2012-051005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quinlivan E, Patel S, Grodensky C, Tien H, Hobbs M. Modeling the impact of Trichomonas vaginalis infection on HIV transmission in HIV-infected individuals in medical care. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2012;39:671–677. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3182593839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chesson H, Blandford J, Pinkerton S. Estimates of the annual number and cost of new HIV infections among women attributable to trichomoniasis in the United States. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2004;31:547–551. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000137900.63660.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kissinger P, Amedee A, Clark R, et al. Trichomonas vaginalis treatment reduces vaginal HIV-1 shedding. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2009;36:11–16. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318186decf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sutton M, Sternberg M, Koumans E, McQuillan G, Berman S, Markowitz L. The prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis infection among reproductive-age women in the United States, 2001–2004. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2007;45:1319–1326. doi: 10.1086/522532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kissinger P. Epidemiology and Treatment of Trichomoniasis. Current Infectious Disease Reports. 2015;17:31. doi: 10.1007/s11908-015-0484-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bachmann L, Hobbs M, Sena A, et al. Trichomonas vaginalis Genital Infections: Progress and Challenges. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2011;53:S160–S172. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Covington S. Women and the criminal justice system. Women's Health Issues. 2007;17:180–182. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Goddard-Eckrich D, et al. Efficacy of a Group-Based Multimedia HIV Prevention Intervention for Drug-Involved Women under Community Supervision: Project WORTH. PloS One. 2014;9:e111528. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caliendo A, Jordan J, Green A, Ingersoll D, Diclemente R, Wingood G. Real-Time PCR improves Detection of Trichomonas vaginalis infection compared with culture using self-collected vaginal swabs. Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005;13:145–150. doi: 10.1080/10647440500068248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roth A, Williams J, Ly R, et al. Changing Sexually Transmitted Infection Screening Protocol Will Result in Improved Case Finding for Trichomonas vaginalis Among High-Risk Female Populations. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2011;38:398–400. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318203e3ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nijhawan A, DeLong A, Celentano D, et al. The Association Between Trichomonas Infection and Incarceration in HIV-Seropositive and At-Risk HIV-Seronegative Women. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2011;38:1094–1000. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31822ea147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lazenby G, Unal E, Andrews A, Simpson K. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Annual Trichomonas vaginalis Screening and Treatment in HIV-Positive Women to Prevent HIV Transmission. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2014;41:353–358. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roth A, Fortenberry J, Van Der Pol B, et al. Court-based participatory research: collaborating with the justice system to enhance sexual health services for vulnerable women in the United States. Sexual Health. 2012;9:445–452. doi: 10.1071/SH11170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Der Pol B, Williams J, Orr D, Batteiger B, Fortenberry J. Prevalence, incidence, natural history, and response to treatment of Trichomonas vaginalis infection among adolescent women. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2005;192:2039–2044. doi: 10.1086/498217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kissinger P. Trichomonas vaginalis: a review of epidemiologic, clinical and treatment issues. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2015;15:307. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-1055-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carter J, Whithaus K. Neonatal respiratory tract involvement by Trichomonas vaginalis: a case report and review of the literature. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2008;78:17–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allsworth J, Ratner J, Peipert J. Trichomoniasis and other sexually transmitted infections: results from the 2001–2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2009;36:738–744. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181b38a4b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwebke J, Desmond R. A randomized controlled trial of partner notification methods for prevention of trichomoniasis in women. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2010;37:392–396. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181dd1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kissinger P, Secor W, Leichliter J, et al. Early repeated infections with Trichomonas vaginalis among HIV-positive and HIV-negative women. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2008;46:994–999. doi: 10.1086/529149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spence M, Harwell T, Davies M, Smith J. The minimum single oral metronidazole dose for treating trichomoniasis: a randomized, blinded study. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1997;89:699–703. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)81437-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]