Abstract

Introduction

Skeletal muscle wasting and weakness with mitochondrial dysfunction (MD) are major pathological problems in burn injury (BI) patients. Fibrinogen levels elevated in plasma is an accepted risk factor for poor prognosis in many human diseases, and is also designated one of damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMPs) protein. The roles of upregulated fibrinogen on muscle changes of critical illness including BI are unknown. The hypothesis tested was that BI-upregulated fibrinogen plays a pivotal role in the inflammatory responses and MD in muscles, and that DAMPs inhibitor, glycyrrhizin mitigates the muscle changes.

Methods

After third degree BI to mice, fibrinogen levels in the plasma and at skeletal muscles were compared between BI and sham-burn (SB) mice. Fibrinogen effects on inflammatory responses and mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) loss were analyzed in C2C12 myotubes. In addition to survival, the anti-inflammatory and mitochondrial protective effects of glycyrrhizin were tested using in vivo microscopy of skeletal muscles of BI and SB mice.

Results

Fibrinogen in plasma and its extravasation to muscles significantly increased in BI versus SB mice. Fibrinogen applied to myotubes evoked inflammatory responses (increased MCP-1 and TNF-α; 32.6 and 3.9 fold, respectively) and reduced MMP; these changes were ameliorated by glycyrrhizin treatment. In vivo MMP loss and superoxide production in skeletal muscles of BI mice were significantly attenuated by glycyrrhizin treatment, together with improvement of BI survival rate.

Conclusions

Inflammatory responses and MMP loss in myotubes induced by fibrinogen were reversed by glycyrrhizin. . Anti-inflammatory and mitochondrial protective effect of glycyrrhizin in vivo leads to amelioration of muscle MD and improvement of BI survival rate.

INTRODUCTION

Muscle wasting and the associated muscle weakness (1, 2) is a concomitant feature of many types of critical illnesses including burn injury (BI), major trauma, or sepsis, and also seen with immobilization, and denervation. The muscle wasting and muscle weakness of critical illness often leads to dependence on mechanical ventilation (3), with increased morbidity, mortality and medical costs (4). The “muscle wasting condition” of critical illness does not imply a state of muscle atrophy alone, but also include metabolic derangements manifested as hyper-turnover of proteins, insulin resistance, and mitochondrial dysfunction (MD) in muscle, all of which have systemic implications (5). Importantly, the distant muscles away from the site of BI are often affected, leading to a generalized muscle asthenia. It is therefore imperative to establish therapeutic targets with the aim to prevent the muscle asthenia in critically ill patients including BI. Clear delineation as to how these catabolic events are switched on, and how they affect the muscle changes remain to be fully elucidated. Of note, many lines of evidence document that MD and derangements in the regulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) accompany muscle wasting during critical illnesses (6).

MD is closely related to ongoing cellular detrimental processes including superoxide production (7) and release of apoptotic-signal mediators (8) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) (9), all of which have systemic effects including increased risk for multiple organ failure (10). By post-mortem analyses of harvested samples, we previously provided indirect evidence for the involvement of MD during BI-induced muscle changes in mice (11). Although several therapeutic approaches targeting protection of mitochondria have been proposed, the link between MD and ROS and their role in overall survival has not been investigated in detail especially in the in vivo settings due to technical difficulties associated with mitochondrial analyses in vivo.

Fibrinogen is a major constituent of the blood coagulation cascade. In clinical pathological states, plasma levels of fibrinogen correlates well with the prognosis of patients including cardiovascular (12) and non-cardiovascular diseases (13), and has been accepted as a biochemical marker for the patient prognosis. Still unanswered question, however, is whether fibrinogen serves as the causative pathological protein or just an auxiliary inflammatory marker. Accumulating evidence mainly from cell culture work suggests that fibrinogen directly stimulates, and thus acts an intrinsic ligand for toll-like receptor (TLR)-4 in many cells (14), implying that fibrinogen can be an inflammatory mediator and also act as a constituent of DAMPs (15). Whether fibrinogen has deleterious effects directly on muscle cells has not been studied, however.

Glycyrrhizin is a major component purified from licorice root and has been widely used as herbal medicine. Previously, it has been used to effectively treat various inflammatory diseases including chronic hepatitis (16), and suggested as therapy against other inflammatory pathologies including BI (17). Previous studies have demonstrated that glycyrrhizin exerts anti-inflammatory effects by blocking TLR2/4 signaling (18), and through mitochondria-protective effects (19). The in vivo role of glycyrrhizin on skeletal muscle mitochondria protection or its effect on improving the prognosis of critical illnesses, however, has not been investigated. In the current study, direct pathological roles of fibrinogen on myotubes and the protective efficacy of glycyrrhizin were examined in C2C12 cell culture system. Using BI mouse as a paradigm of critical illness and muscle wasting, the hypothesis tested was that BI-induced increased fibrinogen levels lead to inflammatory responses and MD in muscle, and that glycyrrhizin treatment mitigates these muscle changes and overall prognosis after BI.

METHODS

Materials

MitoSOX, DiOC6 (3,3'-Dihexyloxacarbocyanine Iodide), Cell Tracker, JC-1, LinearFlow Intensity Calibration beads, Trizol and SYBR Green were from ThermoFisher Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). Antibody against fibrinogen-γ was obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, MA), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) from Abgent (San Diego, CA) and glycyrrhizin from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) kit for fibrinogen was from Genway Biotech (San Diego, CA)

Animal Study

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee at Massachusetts General Hospital. Male BL6 mouse (Jackson, MA), of 6 weeks age, weighting 20–30g, were used. After acclimatization, the animals were randomly allocated to different experimental groups.

Burn Injury (Local): Under anesthesia with pentobarbital (65mg/kg BW), a third degree burn injury was inflicted on the tibialis anterior (TA) muscle according to the method previously described (20). Burn Injury (Systemic): A third degree BI covering 35% of body surface area was administered under pentobarbital anesthesia as previously described (21). SB injury served as the control group. Survival rate was measured and compared among groups.

Drug Treatment

Dosage of glycyrrhizin: Based on previous cell culture studies with glycyrrhizin administered directly to cells showed no cytotoxic effect at least up to 50μg/ml (22, 23). Thus, 50μg/ml dose of glycyrrhizin was selected for the C2C12 cell culture experiments and in vivo intramuscular-injection experiment. According to the previous in vivo experiments in rodents with systemic administration, the glycyrrhizin effective doses ranged from 5 - 200mg/kg (24, 25) The current study utilized intraperitoneal injection of 50mg/kg.

Local administration of glycyrrhizin: In the treatment group, 50μg/ml glycyrrhizin in Krebs-Ringer solution (KR) was intramuscularly injected at the acute phase after BI (30 minutes), and incubated for 60 minutes. In the control groups, only solvent (KR) and no glycyrrhizin was injected by the same method.

Systemic administration: In the in vivo glycyrrhizin treatment experiments, 50mg/kg glycyrrhizin was administered daily by intra-peritoneal injection. In the control group, the same amount of normal saline was injected daily.

Staining for ROS

After the 60 minute incubation with glycyrrihizin or saline, a fluorescent indicator dye for detection of mitochondria-derived superoxide, MitoSOX (5μM) was injected intramuscularly into the tibialis anterior after local BI and incubated for 60 minutes. In vivo microscopy was performed as previously described (26). For in vivo detection of ROS, mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital, intubated and mechanically ventilated. Tibialis muscles were exposed and immersed in Krebs Ringer for observation. The specificity and validity of the fluorescent signal detected were confirmed by signal elimination with anti-oxidant, ascorbic acid. The consistency of image signals among assays was confirmed with fluorescent intensity standard beads co-injected into the tissue (488nm LinearFlow Calibration beads). The timing of measurement was expressed as the time point of data acquisition.

Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential

In the systemic BI, the sternomastoid muscles were exposed and incubated with 40nM DiOC6 for 30 minutes, for mitochondria-specific staining (27). Cell Tracker Orange was used as non-specific staining to validate the consistency of the staining among groups. After the incubation with dyes, muscles were washed with Krebs-Ringer and the mouse was placed under the microscope for observation. Previously DiOC6 has been used for staining endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and nuclear envelop at 1 to 5 μM (20-100 times higher concentration than that used of mitochondrial membrane potential). Thus, under conditions employed in this study, ER or nuclear envelope is not stained (27).

Fibrinogen assay (Western blot)

The blood sampling for fibrinogen levels was performed in the three groups of mice (SB, BI alone, and BI with glycyrrhizin). After plasma separation by centrifugation, the samples were diluted 500 times and run on SDS-polyacrylamide gel and fibrinogen in each plasma sample was quantified by Western blot. Anti-fibrinogen gamma chain antibody was used as the first antibody followed by anti-rabbit HRP as the second antibody.

ELISA

Plasma levels of fibrinogen were quantified by ELISA according to manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, appropriately diluted plasma samples both from burn mice and sham-burn controls were applied to ELISA plate along with fibrinogen standards. After binding of the peroxidase-conjugated antibody, the bound quantity was measured by the reaction of chromogenic substrate at 450nm.

Immunohistochemistry

As previously described (11), after rinsing of tissue blood, the harvested muscle samples were snap-frozen in pre-cooled methylbutane, cryosectioned, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, blocked and stained with anti-fibrinogen antibody.

Tissue homogenization

According to the standard homogenization method (21), harvested muscle samples were homogenized using Polytron tissue grinder in the homogenization buffer containing 20mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.4), 2% Triton X-100, 150mM NaCl, 1mM (EDTA) supplemented with 5μg/ml aprotinin, 10μg/ml leupeptin, 10μg/ml pepstatin A and 1mM PMSF. Crude tissue homogenates were obtained by low-speed centrifugation at 800xg for 10 minutes. Total protein concentrations were measured and adjusted among samples.

Mitochondria staining assay in C2C12 myogenic cells

C2C12 cell were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin and streptomycin. To induce differentiation, medium was changed to DMEM with 2% horse serum. After 1 hour of pre-incubation with or without glycyrrhizin (50μg/ml), the C2C12 cells were stimulated with different concentrations of fibrinogen for 2 hours. Then, the dishes were washed with PBS and incubated with 10μg/ml JC-1 for 10 minutes with constant rocking. After washing, the cells were observed under the fluorescent microscope.

RT-PCR of inflammatory mediators produced by C2C12 cells

Following pre-incubation with or without glycyrrhizin (50μg/ml), differentiated C2C12 myotubes were incubated with different concentrations of fibrinogen for 2 hours. After washing, the cells were harvested by snap freezing in liquid nitrogen. The cells are scraped and homogenized in a standard Trizol homogenization method. After extracting mRNAs, inflammatory mediators were quantified by SYBR-Green mediated quantitative real-time PCR method using ViiA™ 7 Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Data analysis

Fluorescent Signal was captured by Nikon Eclipse 800 microscope equipped with CCD-Spot Camera. The captured images were fed into a post-acquisition analysis software, Image J. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean and analyzed with Student's t-test for two-group comparison, one-way ANOVA and Tukey's method for three-group comparison (GraphPad Prism), Welch's ANOVA with Games-Howell's method was used for time-course analysis, and Kaplan-Meier method for the survival curve analyses. A value of p<0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

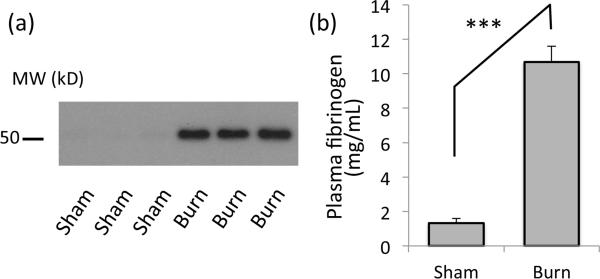

Fibrinogen in plasma is increased after burn injury

To examine whether BI causes upregulation of circulating fibrinogen in the blood, plasma samples from experimental and control groups at post burn day 3 (PBD3) were analyzed by Western blotting (Fig.1a). The intensity of the plasma fibrinogen band was significantly higher than sham. The plasma concentration of fibrinogen was 10.69 +/− 0.91 vs. 1.34 +/− 0.25 (mg/ml) for burn and sham-burn mice by ELISA (Fig.1b). The observed increase of the band at 50kD indeed represents fibrinogen based on the velocity gradient endogenous molecular weight confirmation (migrates at 300kD to 400kD, supplementary data) corresponding to the full size of fibrinogen complex.

Figure 1. Plasma fibrinogen is increased in burn-injured mice.

(a) Western blotting with anti-fibrinogen-γ antibody shows a single band at 50kD increased in the plasma from burned mice (Burn), as compared to that from SB control (Sham). Three representative results from samples from different mice are shown. (b) Plasma fibrinogen concentration measured by ELISA is shown. ***: p<0.001, Student's t-test, n=4.

To analyze whether increased plasma fibrinogen leads to extravasation of fibrinogen to the skeletal muscle tissues, immunofluorescent staining of the tibialis anterior muscle was performed at day 3 after BI to trunk. As shown in Fig.2, the tibialis muscle distant from body burn showed significantly higher cell surface staining suggesting extravasated fibrinogen accumulated in the interstitial space or attached to the sarcolemmal surface.

Figure 2. Immunohistochemistry of fibrinogen on the skeletal muscle tissues.

(a) At day 3 after burn injury, tibialis anterior muscle was harvested, cyrosectioned and stained for fibrinogen-γ. Burn injury increased the cell surface staining for fibrinogen as pointed by white arrows. (b) Cell membrane staining was quantified by densitometry. *: p<0.05 by Student's-t, N=5. White bar=20μm.

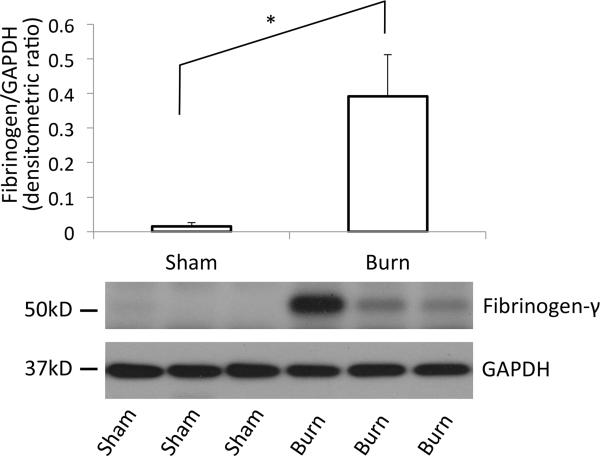

To confirm the increased fibrinogen level in the vicinity of muscle tissue, tibialis anterior muscles harvested at PBD3 were homogenized and tissue fibrinogen amount was quantified by Western blotting using an anti fibrinogen antibody. As show in Fig.3, distant muscle from burn injury showed significant increase in the amount of fibrinogen as compared to sham-burn controls (Fig.3), confirming the data from immunofluorescence staining (Fig2).

Figure 3. Western blotting of tibialis muscle confirms fibrinogen accumulation in the tissue.

At day 3 after burn injury, tibialis anterior muscles were harvested, homogenized and total homogenate were immunoblotted against fibrinogen. Band intensity of the Western blotting results was quantified by densitometry. y-axis represents arbitrary densitometric unit. GAPDH was used as internal control *:p<0.05, n=5, Student's t-test.

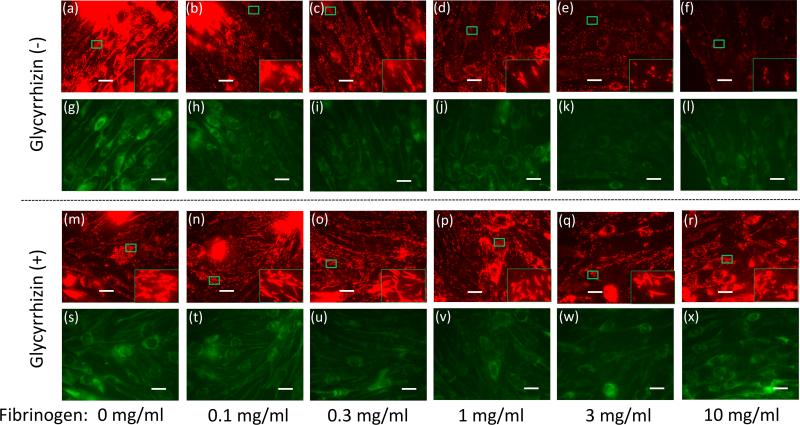

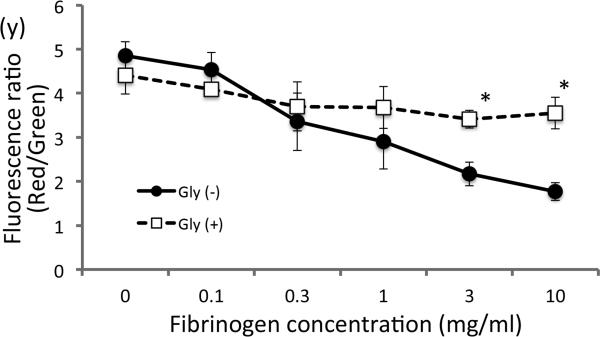

Fibrinogen causes loss of MMP in myotubes

Previous studies reported that critical illnesses including burn injury and sepsis lead to MD (8, 11). One reflector of mitochondrial function is the measure of the mitochondrial membrane potential (8). To examine whether fibrinogen has direct biological effect on muscle cells, differentiated C2C12 cells were treated with increasing doses of fibrinogen (0-10mg/ml). Fibrinogen treatment decreased MMP in a dose-dependent manner (Fig.4a-f). This finding is consistent with previous studies reporting direct effect of fibrinogen on other cell types (14), where enhanced TLR-mediated signaling was attributed to fibrinogen. The concentrations producing MMP loss (1-10mg/ml) overlap the range of the estimated fibrinogen concentrations in the interstitial fluid in muscle from BI mice (2.5-7.5mg/ml, see above). Based on the previous reports for glycyrrhizin attenuating TLR signaling (18) and inflammation (19), we incubated the C2C12 muscle cells with glycyrrhizin before and during the treatment with fibrinogen. MMP loss induced by fibrinogen was ameliorated by glycyrrhizin (Fig.4s-x&y).

Figure 4. Fibrinogen directly induces reduction in membrane potential.

Differentiated C2C12 cells were treated with increasing fibrinogen concentrations and mitochondrial membrane potential was measured by staining with JC-1. Red fluorescence, representing high mitochondrial membrane potential, diminished with increasing doses of fibrinogen without glycyrrhizin treatment (a-f) while green staining for low membrane potential in mitochondria was relatively unchanged (g-l). Glycyrrhizin treatment (m-x) ameliorated the reduction in mitochondrial membrane potential.

Inlet in each figure shows magnified view of the mitochondria staining. With the loss of membrane potential, the red staining changes from elongated form into punctuate staining. (y) Fluorescence intensity was quantified by densitometry, and the ratio of red/green was plotted for the groups with or without glycyrrhizin treatment. *:p<0.05 by Student's-t test, n=3. White bar=20μm.

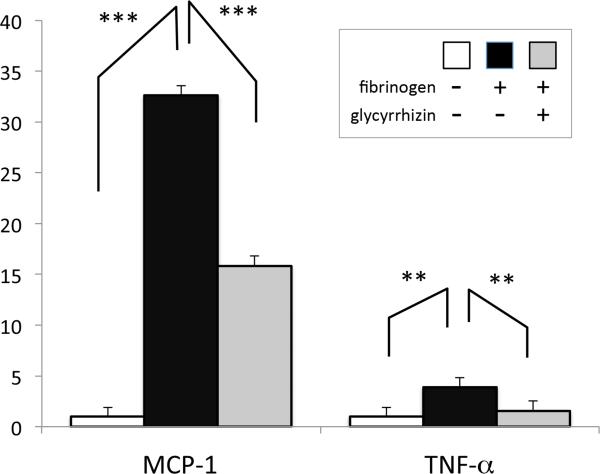

Fibrinogen-induced inflammatory responses in myotubes are reduced by glycyrrhizin treatment

To further evaluate the effect of fibrinogen on muscles, differentiated C2C12 myotubes were stimulated by 3mg/ml fibrinogen for 2 hours with or without glycyrrhizin treatment. Total RNA was extracted and mRNAs for monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and GAPDH were quantified by real-time RT-PCR. Relative quantification after normalization against GAPDH transcripts revealed inflammatory response evoked by fibrinogen, with MCP-1 and TNF-α upregulated to 32.6 and 3.9 time, respectively. Glycyrrhizin significantly ameliorated the inflammatory response (Fig.5).

Figure 5. Fibrinogen induces inflammatory responses in myotubes.

C2C12 cells were treated with 3mg/ml fibrinogen for 2 hours with or without glycyrrhizin. Total RNA was purified from the harvested cells and quantitative real time RT-PCR performed. Relative quantification of inflammatory cytokines (MCP-1 and TNF-α) expression normalized against GAPDH (internal control) is shown as bar graphs with standard error. ***:p<0.001, **:p<0.01 by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's comparison. N=4.

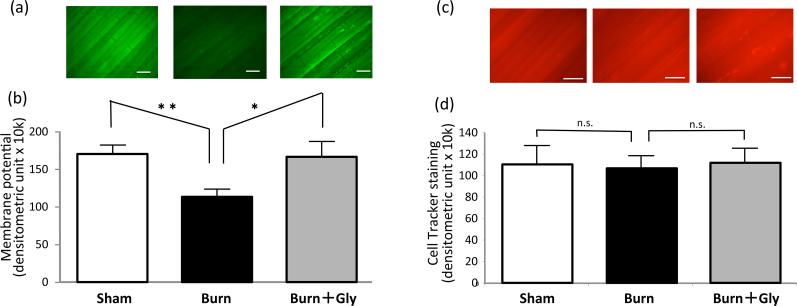

BI-induced disturbed MMP is ameliorated by glycyrrhizin treatment

Despite the well-established importance of mitochondria in skeletal muscle functions, most previous studies related to critical illnesses measured MMP using cell culture models or using purified mitochondria due to the technical difficulties in measuring its functions directly in vivo. Whether the whole body BI to mice leads to reduction in skeletal muscle membrane potential was examined using in vivo in distant sternomastoid muscle.

MMP was analyzed in the skeletal muscles from three groups of mice (burn, sham-burn control, and burn with glycyrrhizin treatment) at PBD3 under in vivo microscopy using DiOC6, the MMP dependent dye (27). The consistency of staining condition was confirmed by the counter staining with non-specific CellTracker dye. BI mice showed significant decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential (Fig.6), supporting the presence of a systemic MD in burns. Consistent with the cell culture work (Fig.4), glycyrrhizin treatment ameliorated the MMP defect.

Figure 6. Mitochondrial membrane potential loss in burns is ameliorated by glycyrrhizin treatment.

(a) In vivo microscopic images of sternomastoid muscles are shown to investigate the systemic effect of burn injury. Muscles were stained by DiOC6 for mitochondrial membrane potential after whole body burn injury with or without glycyrrhizin treatment. (b) DiOC6 signal for mitochondrial membrane potential was analyzed by densitometry and shown as the average value of fluorescent intensity with the standard error (N=7). (c) Counterstaining with CellTracker as the internal control is shown. (d) The staining intensity was equivalent among all three groups. Fluorescent signal of burn group was significantly lower than that of sham-burn control group (Sham). Glycyrrhizin treatment group (Burn+Gly) showed improved signal as compared to burn treated with normal saline (Burn). N=7, *:p<0.05, **:p<0.01 by ANOVA with Tukey's comparison. n.s: not statistically significant. White bar=200μm.

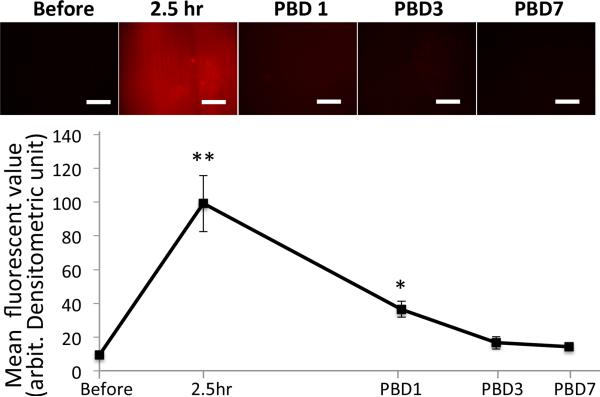

Burn injury increases mitochondria-derived superoxide production in skeletal muscles

Previous reports have documented ROS production is closely related to various organ dysfunctions in critical illnesses including burn injury (6) and sepsis (28). We thus next measured mitochondria-derived superoxide production in muscle samples following BI. At pre-determined time points after local BI, tibialis anterior muscles were stained with MitoSOX and observed under in vivo microscopy (Fig.7). Time course analysis showed that superoxide production in the muscles of BI mice follows chronological changes. Among the time points tested, 2.5 hour after BI gave the highest degree of superoxide staining, which gradually diminished during the next few days. By day 3 to 7 after burn injury, the superoxide production was down to the basal levels.

Figure 7. Burn injury alters mitochondria-derived superoxide production in a time-dependent manner.

At predetermined time points after burn injury, superoxide production from mitochondria, stained by MitoSOX, was measured in tibialis anterior muscles under in vivo microscopy to study the local effect of BI. Superoxide increased at 2.5 hours after burn injury (‘2.5hr’) and decreased with time following days after burn injury (‘PBD’ on the x-axis represents post burn day). **:p<0.01, *:p<0.05, n=5, Welch's ANOVA with Games-Howell's comparison. White bar=200μm, x-axis is shown in a logarithmic scale.

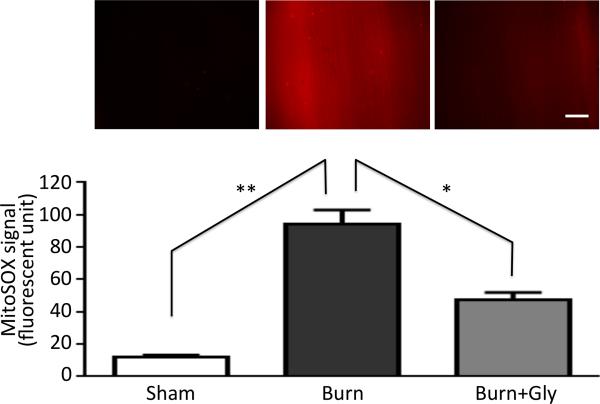

Glycyrrhizin ameliorates elevated mitochondrial superoxide production in BI mice

To test whether blocking the inflammatory effect by glycyrrhizin reverses the increase in burn-induced superoxide production from mitochondria, MitoSOX signals were compared between burn injury groups with and without glycyrrhizin at 2.5 hour after burn injury. As shown in Fig.8, local BI caused a significant increase in the superoxide production as compared to sham-burn injury. Burn-induced superoxide production was suppressed by glycyrrhizin treatment.

Figure 8. Burn injury-induced increased superoxide production from mitochondria in skeletal muscle was ameliorated by glycyrrhizin treatment.

In vivo microscopic image are shown for the mitochondria-derived superoxide stained in tibialis anterior muscles by MitoSOX (upper panel) to study the effect of local BI. MitoSOX signal was quantified by densitometry and expressed as the mean value in each group with the standard error (lower panel, N=5). Burn injury (Burn) increased the signal as compared to sham-burn control (Sham), and glycyrrhizin (Burn+Gly) ameliorated the increased signal. **:p<0.01, *:p<0.05 by ANOVA with Tukey's comparison. N=5. White bar represents 200μm.

Glycyrrhizin improves burn survival rate

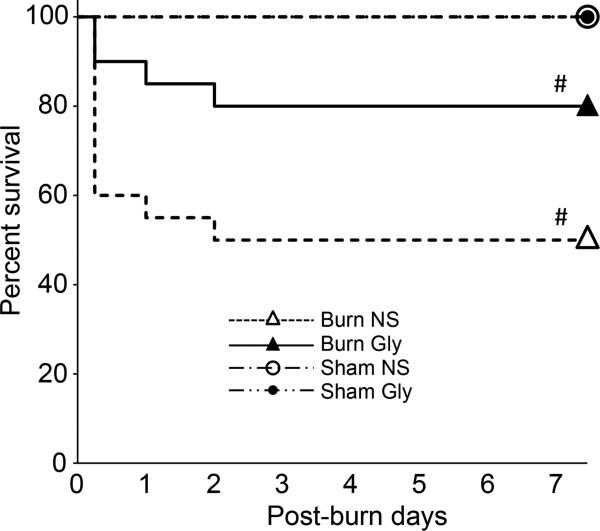

Previous studies have documented the association of MD to the poor prognosis in critical illness models (29). Indicators of tissue MD, including serum lactate and mitochondria DNA, have been related to poor prognosis in critical illnesses in the clinical studies (30, 31). To assess the impact of mitochondria protection by glycyrrhizin treatment on the prognosis of BI mice, the efficacy of glycyrrhizin treatment on BI survival rate was examined. The survival rate of BI mice significantly improved from 50% to 80% by glycyrrhizin treatment (Fig.9, p<0.05). The improved survival rate is consistent with the hypothesis that burn-induced MD and superoxide production can lead to poor survival after burn injury.

Figure 9. Kaplan-Meier analysis of the efficacy of glycyrrhizin treatment.

Survival rate of the whole body burn injury was analyzed with or without glycyrrhizin treatment. As compared to control group with normal saline injection (‘Burn NS’), glycyrrhizin treatment (‘Burn Gly’) significantly improved the BI survival rate. Sham-burn control group with or without treatment showed no mortality. #: p<0.05 by log-rank test. N=20 for Burn NS, 20 for Burn Gly, 5 for Sham NS, 5 for Sham Gly. X-axis represents post-burn days and y-axis shows percent survival.

DISCUSSION

In the current study, we document that BI-induces upregulation of the inflammatory mediator, fibrinogen. The increased levels of plasma fibrinogen extravasated onto the skeletal muscle tissues. Using in vitro cell culture experiment, we demonstrate for the first time that fibrinogen can induce MD and inflammatory responses (increased MCP-1 and TNF- α) in the skeletal myocytes and that glycyrrhizin treatment ameliorated the MD and inflammatory responses. In vivo microscopy experiments demonstrated for the first time that glycyrrhizin treatment reversed BI-induced MD and ROS production in the mouse skeletal muscle, and also resulted in improved survival rate after BI.

Increased levels of plasma fibrinogen

The current study demonstrated plasma fibrinogen levels are significantly increased at PBD3 as compared to sham-burn controls using Western Blotting and ELISA. Accordingly previous studies with burns, serum/plasma fibrinogen level is increases from PBD1 to PBD5 (32-34). Previous studies showed maximal metabolic changes are often observed at PBD3 (35). Thus, the current study prioritized showing differences in fibrinogen levels at PBD3, but does not exclude the possibility that plasma fibrinogen levels and other parameters may show peak at earlier or later time points.

Roles of mitochondria dysfunction in burn injury

Severe burn injury in humans has poor prognosis because of major complications which include neuromuscular dysfunction with muscle mass loss (36), increased vascular permeability (37), systemic inflammation, hypermetabolic state (38), insulin resistance (39) and multiple organ failure. Notably, MD has been implicated in these specific conditions (40), but detailed understanding of the mitochondrial changes have not been elucidated (38). Specifically, MD leads to release ROS and various damaged mitochondrial molecules including high mobility group box 1 (HMGB-1). ROS can also trigger production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and inflammatory mediators including MCP-1 and TNF-α (41). Pro-inflammatory cytokines and ROS can stimulate JAK-STAT signaling (42), leading to the production and release of fibrinogen by the liver, thus creating a vicious cycle of inflammation. Suppression of this vicious circle could possibly lead to tissue preservation and organ survival. The current study, by using novel in vivo microscopic techniques combined with conventional assays and cell culture approaches, provide evidence that mitochondria protection can impact prognosis in severe BI. This study focused on skeletal muscle mitochondria, given that skeletal muscle MD is considered to play a major role in muscle wasting of BI and a major risk factor for the poor prognosis in critical illness when there is severe muscle asthenia of BI patients.

Novel role of fibrinogen

It has been well accepted that increased fibrinogen is a risk factor not only for cardiovascular but also for non-cardiovascular diseases (13). Recent mechanistic studies demonstrated that TLR4 can be stimulated by fibrinogen (14). There have been accumulating reports suggesting crosstalk between innate immunity and coagulation system (43). There has been no study, however, that has examined the direct effect of fibrinogen on the muscle cells. In the current study, we have demonstrated the fibrinogen directly evokes pro-inflammatory responses and causes decreased MMP in myotubes. One reasonable question will be why nature has evolved so that fibrinogen plays two different roles. In major trauma, coagulation system including activation of fibrinogen plays pivotal roles in controlling the bleeding and thus essential for the survival of individuals and the species.

Activation of inflammation and suppression of the mitochondrial functions in muscle tissue by fibrinogen may be an evolutionary adaptation benefiting survival of animals under traumatic conditions by decreased protein synthesis and enhancing protein breakdown for transport of amino acids to tissue repair sites. For example, when there is massive bleeding, the individual has to survive by suppressing and controlling the energy expenditure, reminiscent of the process employed during hibernation, a reasonable evolutionary approach by nature when no surgical intervention was available. In the modern era with advanced medical technologies where bleeding and infection can be controlled, however, the negative impact of excess inflammatory responses or suppression of organ functions seem to continue to occur despite surgical and medical maneuvers.

Therapeutic value of glycyrrhizin on burn-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and ROS

The current work has provided novel in vivo evidence that glycyrrhizin ameliorates the defect in mitochondrial function and suppresses mitochondria-derived superoxide production after burn injury. It does not, however, exclude the possibility that the effect of glycyrrhizin exerts its effect on mitochondria protection secondarily through suppression of systemic and local inflammation (44) or the possibility that improvement of survival may be through other mechanisms. The fact the glycyrrhizin inhibited mitochondrial changes ex vivo suggests a direct action also. Further studies are necessary to determine the primary in vivo target of glycyrrhizin. Mitochondrial protective effect and anti-inflammatory action of glycyrrhizin may cross-talk, based on previous studies documenting that glycyrrhizin by blocking TLR2/4 signaling inhibits inflammatory mediators (18), and suppresses the release of DAMPs from cells which are put under destructive stresses (45).

Among many other anti-inflammatory agents and interventions (46), however, glycyrrhizin has a long history of clinical use for treatment of chronic hepatitis (16), and its safety has been well studied. The current study therefore provides scientific evidence of glycyrrhizin as the promising therapeutic choice in BI-induced metabolic changes.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates a direct effect of fibrinogen on inflammatory responses and MMP in myotubes. Anti-inflammatory and mitochondrial protective effect of glycyrrhizin leads to amelioration of MD in vivo and improvement of survival rate after BI. This study does not, however, exclude the possibility that mitochondrial functions in other vital organs are also involved in affecting the prognosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: supported by Massachusetts General Hospital, Department of Anesthesia, Critical Care and Pain Medicine Department Fund (to Dr. Yasuhara, Boston, Massachusetts), partly by National Institutes of Health P-50 GM2500: Project-I (to Dr. Jeevendra Martyn, Bethesda, Maryland), partly by Shriners Research Grant (to Dr. Jeevendra Martyn, Tampa, Florida) and partly by Grant-in-Aid for Researchers, Hyogo College of Medicine, 2014 (to Dr. Ryusuke Ueki, Hyogo, Japan)

REFERENCES

- 1.Desai SV, Law TJ, Needham DM. Long-term complications of critical care. Critical care medicine. 2011;39(2):371–379. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181fd66e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Helm PA, Pandian G, Heck E. Neuromuscular problems in the burn patient: cause and prevention. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 1985;66(7):451–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Safdar N, Dezfulian C, Collard HR, Saint S. Clinical and economic consequences of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a systematic review. Critical care medicine. 2005;33(10):2184–2193. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000181731.53912.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warren DK, Shukla SJ, Olsen MA, Kollef MH, Hollenbeak CS, Cox MJ, Cohen MM, Fraser VJ. Outcome and attributable cost of ventilator-associated pneumonia among intensive care unit patients in a suburban medical center. Critical care medicine. 2003;31(5):1312–1317. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000063087.93157.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen S, Nathan JA, Goldberg AL. Muscle wasting in disease: molecular mechanisms and promising therapies. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2015;14(1):58–74. doi: 10.1038/nrd4467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parihar A, Parihar MS, Milner S, Bhat S. Oxidative stress and anti-oxidative mobilization in burn injury. Burns : journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries. 2008;34(1):6–17. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mantel C, Messina-Graham SV, Broxmeyer HE. Superoxide flashes, reactive oxygen species, and the mitochondrial permeability transition pore: potential implications for hematopoietic stem cell function. Current opinion in hematology. 2011;18(4):208–213. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3283475ffe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yasuhara S, Asai A, Sahani ND, Martyn JA. Mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, and alternative pathways of cell death in critical illness. Critical care medicine. 2007;35(9 Suppl):S488–495. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000278045.91575.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krysko DV, Agostinis P, Krysko O, Garg AD, Bachert C, Lambrecht BN, Vandenabeele P. Emerging role of damage-associated molecular patterns derived from mitochondria in inflammation. Trends in immunology. 2011;32(4):157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stallons LJ, Funk JA, Schnellmann RG. Mitochondrial Homeostasis in Acute Organ Failure. Current pathobiology reports. 1(3):2013. doi: 10.1007/s40139-013-0023-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yasuhara S, Perez ME, Kanakubo E, Yasuhara Y, Shin YS, Kaneki M, Fujita T, Martyn JA. Skeletal muscle apoptosis after burns is associated with activation of proapoptotic signals. American journal of physiology Endocrinology and metabolism. 2000;279(5):E1114–1121. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.279.5.E1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowe GD. Fibrinogen assays for cardiovascular risk assessment. Clinical chemistry. 2010;56(5):693–695. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.145342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perisanidis C, Psyrri A, Cohen EE, Engelmann J, Heinze G, Perisanidis B, Stift A, Filipits M, Kornek G, Nkenke E. Prognostic role of pretreatment plasma fibrinogen in patients with solid tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer treatment reviews. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Docherty NG, Godson C. Fibrinogen as a damage-associated mitogenic signal for the renal fibroblast. Kidney international. 2011;80(10):1014–1016. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosin DL, Okusa MD. Dangers within: DAMP responses to damage and cell death in kidney disease. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2011;22(3):416–425. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010040430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iino S, Tango T, Matsushima T, Toda G, Miyake K, Hino K, Kumada H, Yasuda K, Kuroki T, Hirayama C, Suzuki H. Therapeutic effects of stronger neo-minophagen C at different doses on chronic hepatitis and liver cirrhosis. Hepatology research : the official journal of the Japan Society of Hepatology. 2001;19(1):31–40. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6346(00)00079-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Musumeci D, Roviello GN, Montesarchio D. An overview on HMGB1 inhibitors as potential therapeutic agents in HMGB1-related pathologies. Pharmacology & therapeutics. 2014;141(3):347–357. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Honda H, Nagai Y, Matsunaga T, Saitoh S, Akashi-Takamura S, Hayashi H, Fujii I, Miyake K, Muraguchi A, Takatsu K. Glycyrrhizin and isoliquiritigenin suppress the LPS sensor toll-like receptor 4/MD-2 complex signaling in a different manner. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2012;91(6):967–976. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0112038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim DE, Youn YC, Kim YK, Hong KM, Lee CS. Glycyrrhizin prevents 7-ketocholesterol toxicity against differentiated PC12 cells by suppressing mitochondrial membrane permeability change. Neurochemical research. 2009;34(8):1433–1442. doi: 10.1007/s11064-009-9930-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kashiwagi A, Hosokawa S, Maeyama Y, Ueki R, Kaneki M, Martyn JA, Yasuhara S. Anesthesia with Disuse Leads to Autophagy Up-regulation in the Skeletal Muscle. Anesthesiology. 2015;122(5):1075–1083. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hosokawa S, Koseki H, Nagashima M, Maeyama Y, Yomogida K, Mehr C, Rutledge M, Greenfeld H, Kaneki M, Tompkins RG, Martyn JA, Yasuhara SE. Efficacy of phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor on distant burn-induced muscle autophagy, microcirculation, and survival rate. American journal of physiology Endocrinology and metabolism. 2013;304(9):E922–933. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00078.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ashfaq UA, Masoud MS, Nawaz Z, Riazuddin S. Glycyrrhizin as antiviral agent against Hepatitis C Virus. Journal of translational medicine. 2011;9(112) doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takei M, Kobayashi M, Herndon DN, Pollard RB, Suzuki F. Glycyrrhizin inhibits the manifestations of anti-inflammatory responses that appear in association with systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS)-like reactions. Cytokine. 2006;35(5-6):295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hidaka I, Hino K, Korenaga M, Gondo T, Nishina S, Ando M, Okuda M, Sakaida I. Stronger Neo-Minophagen C, a glycyrrhizin-containing preparation, protects liver against carbon tetrachloride-induced oxidative stress in transgenic mice expressing the hepatitis C virus polyprotein. Liver international : official journal of the International Association for the Study of the Liver. 2007;27(6):845–853. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2007.01492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okamoto T, Yoshida S, Kobayashi T, Okabe S. Inhibition of concanavalin A-induced mice hepatitis by coumarin derivatives. Japanese journal of pharmacology. 2001;85(1):95–97. doi: 10.1254/jjp.85.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kashiwagi A, Hosokawa S, Maeyama Y, Ueki R, Kaneki M, Martyn JA, Yasuhara S. Anesthesia with Disuse Leads to Autophagy Up-regulation in the Skeletal Muscle. Anesthesiology. 2014 doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson LV, Walsh ML, Bockus BJ, Chen LB. Monitoring of relative mitochondrial membrane potential in living cells by fluorescence microscopy. The Journal of cell biology. 1981;88(3):526–535. doi: 10.1083/jcb.88.3.526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nethery D, DiMarco A, Stofan D, Supinski G. Sepsis increases contraction-related generation of reactive oxygen species in the diaphragm. Journal of applied physiology. 1999;87(4):1279–1286. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.4.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singer M. The role of mitochondrial dysfunction in sepsis-induced multi-organ failure. Virulence. 2014;5(1):66–72. doi: 10.4161/viru.26907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kung CT, Hsiao SY, Tsai TC, Su CM, Chang WN, Huang CR, Wang HC, Lin WC, Chang HW, Lin YJ, Cheng BC, et al. Plasma nuclear and mitochondrial DNA levels as predictors of outcome in severe sepsis patients in the emergency room. Journal of translational medicine. 10130:2012. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeng JC, Jablonski K, Bridgeman A, Jordan MH. Serum lactate, not base deficit, rapidly predicts survival after major burns. Burns : journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries. 2002;28(2):161–166. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(01)00098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zeineh RA, Steigmann F, Fiorella BJ, Pillay VK. Metabolism of plasma proteins in burn patients. South African medical journal = Suid-Afrikaanse tydskrif vir geneeskunde. 1973;47(41):1959–1961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alkjaersig N, Fletcher AP, Peden JC, Jr., Monafo WW. Fibrinogen catabolism in burned patients. The Journal of trauma. 1980;20(2):154–159. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198002000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schaden E, Hoerburger D, Hacker S, Kraincuk P, Baron DM, Kozek-Langenecker S. Fibrinogen function after severe burn injury. Burns : journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries. 2012;38(1):77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakazawa H, Yamada M, Tanaka T, Kramer J, Yu YM, Fischman AJ, Martyn JA, Tompkins RG, Kaneki M. Role of protein farnesylation in burn-induced metabolic derangements and insulin resistance in mouse skeletal muscle. PloS one. 2015;10(1):e0116633. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kraft R, Herndon DN, Finnerty CC, Shahrokhi S, Jeschke MG. Occurrence of multiorgan dysfunction in pediatric burn patients: incidence and clinical outcome. Annals of surgery. 2014;259(2):381–387. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31828c4d04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shaterian A, Borboa A, Sawada R, Costantini T, Potenza B, Coimbra R, Baird A, Eliceiri BP. Real-time analysis of the kinetics of angiogenesis and vascular permeability in an animal model of wound healing. Burns : journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries. 2009;35(6):811–817. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Porter C, Herndon DN, Borsheim E, Bhattarai N, Chao T, Reidy PT, Rasmussen BB, Andersen CR, Suman OE, Sidossis LS. Long-Term Skeletal Muscle Mitochondrial Dysfunction is Associated with Hypermetabolism in Severely Burned Children. Journal of burn care & research : official publication of the American Burn Association. 2015 doi: 10.1097/BCR.0000000000000308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Porter C, Herndon DN, Sidossis LS, Borsheim E. The impact of severe burns on skeletal muscle mitochondrial function. Burns : journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries. 2013;39(6):1039–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee HY, Kaneki M, Andreas J, Tompkins RG, Martyn JA. Novel mitochondria-targeted antioxidant peptide ameliorates burn-induced apoptosis and endoplasmic reticulum stress in the skeletal muscle of mice. Shock. 2011;36(6):580–585. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3182366872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Naik E, Dixit VM. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species drive proinflammatory cytokine production. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2011;208(3):417–420. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simon AR, Rai U, Fanburg BL, Cochran BH. Activation of the JAK-STAT pathway by reactive oxygen species. The American journal of physiology. 1998;275(6 Pt 1):C1640–1652. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.6.C1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Esmon CT. Interactions between the innate immune and blood coagulation systems. Trends in immunology. 2004;25(10):536–542. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Genovese T, Menegazzi M, Mazzon E, Crisafulli C, Di Paola R, Dal Bosco M, Zou Z, Suzuki H, Cuzzocrea S. Glycyrrhizin reduces secondary inflammatory process after spinal cord compression injury in mice. Shock. 2009;31(4):367–375. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181833b08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu CX, He LX, Guo H, Tian XX, Liu Q, Sun H. Inhibition effect of glycyrrhizin in lipopolysaccharide-induced high-mobility group box 1 releasing and expression from RAW264.7 cells. Shock. 2015;43(4):412–421. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Linden K, Scaravilli V, Kreyer SF, Belenkiy SM, Stewart IJ, Chung KK, Cancio LC, Batchinsky AI. Evaluation of the Cytosorb Hemoadsorptive Column in a PIG Model of Severe Smoke and Burn Injury. Shock. 2015;44(5):487–495. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.