Abstract

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) can minimize HIV transmission. Prevention benefits may be compromised by barriers to virologic suppression, and by increased condomless sex among those initiating ART. We evaluated condomless sex in a cohort of HIVinfected US individuals poised to initiate ART in a clinical trial. We assessed partner and sex act type, condom use, and perception of infectiousness. Six percent of participants reported as not infectious; men who have sex with men were more likely to perceive high infectivity. Prevalence of condomless sex was 44 %; 74 % of those also reported homosexual acquisition of HIV. Predictors of increased risk of condomless sex included greater numbers of lifetime partners, recent stimulant drug use and an HIV-positive or unknown serostatus partner. In the context of serodifferent partners, lower perception of infectiousness was also associated with a higher risk of condomless sex. Results highlight opportunities for prevention education for HIV infected individuals at ART initiation.

Keywords: Condom use, HIV transmission, ART-naïve, Behavior

Introduction

The HIV epidemic in the United States is characterized by 1.1 million individuals living with HIV [1], including 47,500 new HIV infections in 2010 [2]. Approximately 90 % of HIV infections in the US are transmitted via sexual activity [3].

Antiretroviral therapy (ART)-treated individuals with HIV demonstrate reduced infectiousness to sexual partners compared to those not on ART [4, 5]. Mathematical models have suggested that if HIV diagnosis, care linkage, ART treatment, and virologic suppression were maximized, the global HIV epidemic could be extinguished [6]. Numerous psychosocial, socioeconomic, and structural barriers prevent realization of each step of this care and treatment cascade [7, 8].

Transmission-risk behavior (TRB), overwhelmingly condomless sex, may compromise the protective effect of ART via “risk compensation”—whereby the use of a strategy perceived to confer protection against HIV transmission (or acquisition) leads to an increase in risky behavior. Whether or not biomedical HIV prevention strategies lead to increased TRB is a frequently mentioned concern when scale-up of such interventions is discussed.

In order to optimally understand changes in TRB after initiation of ART, it is critical to rigorously describe TRB at the inception of ART. TRB has been assessed by others using a variety of measures, including counts of sexual partners and proportion of sex acts that are non-condom protected. Conflicting results from clinical trials of biomedical prevention strategies characterize the available literature. With regard to the effect of these interventions on TRB, the majority of studies on pre-exposure prophylaxis, post-exposure prophylaxis, and vaccines show no evidence of risk compensation; some evidence from the male circumcision, vaccine, and ART literature suggests the possibility of increased TRB accompanying such interventions [9–16]. A US-based cohort of HIV-infected women suggested fewer sexual partners after initiation of first-time ART, but also less condom use [17]. In international settings, findings have been more consistent, with the vast majority of cohorts demonstrating absence of increased TRB after ART initiation; [18–25] a single study demonstrating increased risk behavior post-ART initiation may be confounded by the improved general health status associated with ART treatment [26].

TRB, specifically condomless sex, was examined as part of a randomized, open-label trial of three ART regimens for treatment-naïve individuals [AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) A5257]. The objectives of this cross sectional baseline analysis of the A5257 study data are to describe the prevalence of self-reported condomless sex in this contemporary, ART-naïve, HIV-infected US-based population immediately prior to ART initiation. We also investigated risk factors associated with condomless sex with a specific focus on whether there was evidence of serosorting and self-reported perception of infectiousness with the goal of identifying education opportunities for HIV prevention at the point of first ART initiation.

Methods

ACTG A5257 was a phase III, prospective, randomized, open-label trial conducted at 57 ACTG and the International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials Group (IMPAACT) clinical research sites in the U.S. and Puerto Rico. Enrollment occurred between May, 2009 and June, 2011. Eligible participants were ART-naïve men and women >18 years with documented HIV-1 RNA level >1000 copies/ml who had no evidence of any major nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) or protease inhibitor (PI)-resistance associated mutations. Participants were randomized 1:1:1 to receive one of three ART regimens of tenofovir/emtricitabine (TDF/FTC) plus raltegravir (RAL), atazanavir/ritonavir (ATV/R), or darunavir/ritonavir (DRV/R). The primary study methods and results have been previously presented [27].

Sexual behaviors over the prior month were captured at study entry and annually during study follow-up by self-report through a paper-based questionnaire. The behavioral questionnaire was adapted from sexual behavior questionnaires used in previous ACTG and other National Institutes of Health Division of AIDS (NIH DAIDS) clinical trials network studies with input from site investigators (Supplementary material). Completed questionnaires were mailed to the data center for keying in a sealed envelope without oversight or review. In the event of literacy issues, or by participant request, assistance with completion of the questionnaire by site staff was permitted. The current analysis reflects questionnaires from the study entry visit only.

The questionnaire was divided into sections for primary and non-primary sexual partners. Participants were asked about the HIV serostatus of partners in the past month and the number and type of protected and unprotected sex acts with these partners. Questions regarding sex acts did not include oral sex. Additional questions included number of lifetime partners, sexual partner preference, and perception of infectiousness (the perceived likelihood of infecting a partner if practicing condomless sex). Questions requiring a specific number were left open-ended for participants to complete; questions relating to partner serostatus or perception of infectiousness included designated choices or a visual analog scale, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome of condomless sex was defined as at least one reported unprotected vaginal or anal receptive or insertive sex act in the past month. A secondary serosorted outcome was further stratified according to reported partner serostatus. Only expected responses based on the skip logic of the questionnaire were used in the endpoint definition. In the event of missing responses regarding type of sex act following a positive response indicating a given type of partner, data were imputed as follows: (a) in the event of no type of activity reported, all outcomes were assumed missing; (b) in the event of at least one type of activity reported, any missing response for the remaining types of sex acts were imputed as zero; (c) responses regarding insertive anal activity were set to missing for all females. Participants not completing the questionnaire were excluded from all analyses given no evaluable data.

The prevalence of condomless sex during the month prior to ART initiation was estimated among participants reporting any evaluable sexual activity (including those reporting no sex) as well as restricted only to those reporting sexual activity; 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) were obtained via the Wald interval from the binomial distribution.

Risk factors associated with condomless sex were evaluated only among participants reporting sexual activity in the past month. To provide a relative risk interpretation, analyses used log binomial regression—a simple log linear model with Poisson error distribution for our binary outcome. Parameter estimation used generalized estimating equations (GEE) with an independent working correlation matrix to account for misspecification of the binomial error distribution [28] as well as dependency between multiple observations within individuals (serosorting analysis only). Risk factors for condomless sex of interest were identified a priori as defined in Table 1. Risk factors with moderate evidence of an association (p ≤ 0.20) in univariate analyses were included in multivariable modeling with some exclusions for collinearity. Interpretations of the estimated relative risk (RR) ratios (95 % CIs) from the final adjusted models were guided by the consistency, trend and magnitude of the observed effects sizes in conjunction with the level of statistical evidence. Effect modification (interaction) by race/ethnicity, sex and partner serostatus was also assessed sequentially for all selected covariates. All analyses used SAS software v9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Table 1.

Definition of model covariates

| Characteristic | Covariate definitiona |

|---|---|

| HIV disease status | |

| HIV-1 RNA | Categorized as <10,000; 10,000–99,999; 100,000–500,000; >500,000 copies/mL |

| Mode of transmission | Participant self-report for acquiring HIV infection. Categorized as homosexual contact; heterosexual contact; and non-sexual contact (transfusion; injectable drug use; occupational exposure; does not want to report; unknown; or other) |

| Risk behaviors | |

| Type of alcoholic drinker | Participant self-report of alcohol use over the past month. Categorized as abstainer (0 drinks); moderate drinker (average of 1 drink/day for women and two drinks/day for men); heavy drinker (average of >3 drinks/day for women and >4 drinks/day for men); binge drinker (any report of >4 drinks in 2 h for women OR >5 drinks in 2 h for men) |

| Stimulant drug use | Participant self-report of ever using amphetamines or cocaine. Categorized as never; within last month; and more than 1 month ago or longer |

| Fertility desires/desire to have children | Participant self-report of desire to have more children. Categorized as yes; no; and unsure |

| Perception of infectiousness | Participant self-report using a continuous visual analog scale from 0 (not at all infectious) to 100 (highly infectious) of how likely the participant would be to infect someone else with HIV had the participant had condomless sex with another individual. Categorized as not infectious (0); low infectiousness (1–33); medium infectiousness (34–66); and highly infectious (67–100) |

| Sexual partner characteristics | |

| Sexual partner preference | Participant self-report of type of sexual partner. Categorized as men who have sex with only men, mostly men, both men and women, and mostly women (MSM, any); men who have sex with women only (MSW); and women who have sex with men and/or women (WSM/W) |

| Type of sexual partner in the past month | Participant self-report of primary and non-primary partners. Categorized as primary partner only; non-primary partner only; primary and non-primary partners; and no partners |

| Total number of sexual partners in lifetime? | Participant self-report of number of individuals a participant had vaginal or anal sex with over lifetime. Categorized as <5 partners; 6–20 partners; 21–50 partners; and >50 partners |

| Number of partners in the past month? | Participant self-report of number of individuals a participant had vaginal or anal sex with in the past month. Categorized as no partners; one partner; and >one partner |

| Partner serostatus | Participant self-report of HIV status of sexual partner. Categorized as HIV-positive partner; HIV-negative partner; or unsure of partner HIV status |

All characteristics were selected and defined a priori. Due to small sample size and modeling purposes, some categories were combined post hoc for analysis

Results

The ACTG A5257 population included 1810 HIV-infected treatment naïve enrolled participants. Overall, 34 % of the participants were non-Hispanic white, 42 % were non-Hispanic black, and 22 % were Hispanic. Women comprised 24 % of the population. Median (Q1–Q3) plasma viral load was 4.62 (4.14–5.12) log10 copies/mL. Approximately 31 % of the population had a baseline HIV-1 RNA level ≥100,000 copies/mL. Approximately half (49 %) of participants were diagnosed within the past year with most (90 %) reporting sexual contact as the most likely mode of transmission; the majority of participants (97 %) were aware of their HIV diagnosis for the full 1 month time horizon encompassed by our baseline behavioral questionnaire. Proportions of participants reporting alcohol and substance use in the past month are noted in Table 2. For the purposes of this analysis, we considered MSM to be men reporting any male partners; men who had sex exclusively with women were considered separately. Participants not reporting a sexual partner preference at study entry were excluded.

Table 2.

Population characteristics

| A5257 Population (N = 1810)b,c | Sex/reported sexual partner preference

|

Reported condomless sex in past month

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 1667)c | MSM (N = 1043) | MSW (N = 223) | WSM/W (N = 401) | Total (N = 637) | Yes (N = 278) | No (N = 359) | pa | |||

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Male | 1375 (76) | 1266 (76) | 1,043 (100) | 223 (100) | 0 (0) | 517 (81) | 232 (83) | 285 (79) | 0.19* | |

| Female | 435 (24) | 401 (24) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 401 (100) | 120 (19) | 46 (17) | 74 (21) | ||

| Age at study entry | ||||||||||

| 18–29 | 528 (29) | 495 (30) | 380 (36) | 35 (16) | 80 (20) | 219 (34) | 89 (32) | 130 (36) | 0.87** | |

| 30–39 | 507 (28) | 459 (28) | 302 (29) | 55 (25) | 102 (25) | 192 (30) | 94 (34) | 98 (27) | ||

| 40–49 | 510 (28) | 469 (28) | 265 (25) | 67 (30) | 137 (34) | 170 (27) | 80 (29) | 90 (25) | ||

| 50 and above | 265 (15) | 244 (15) | 96 (9) | 66 (30) | 82 (20) | 56 (9) | 15 (5) | 41 (11) | ||

| Race/ethnicity (self-reported) | ||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 616 (34) | 570 (34) | 480 (46) | 28 (13) | 62 (15) | 266 (42) | 143 (51) | 123 (34) | <0.001* | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 757 (42) | 702 (42) | 335 (32) | 125 (56) | 242 (60) | 232 (37) | 91 (33) | 141 (39) | ||

| Hispanic | 390 (22) | 350 (21) | 193 (19) | 65 (29) | 92 (23) | 119 (19) | 35 (13) | 84 (24) | ||

| Asian/more than one race | 43 (2) | 41 (2) | 32 (3) | 4 (2) | 5 (1) | 18 (3) | 9 (3) | 9 (3) | ||

| Baseline HIV-1 RNA (copies/mL) | ||||||||||

| <10,000 | 367 (20) | 340 (20) | 195 (19) | 31 (14) | 114 (28) | 140 (22) | 59 (21) | 81 (23) | 0.47** | |

| 10,000–99,999 | 888 (49) | 822 (49) | 519 (50) | 112 (50) | 191 (48) | 315 (49) | 134 (48) | 181 (50) | ||

| 100,000–500,000 | 426 (24) | 388 (23) | 254 (24) | 63 (28) | 71 (18) | 149 (23) | 73 (26) | 76 (21) | ||

| >500,000 | 129 (7) | 117 (7) | 75 (7) | 17 (8) | 25 (6) | 33 (5) | 12 (4) | 21 (6) | ||

| Homosexual contact | 978 (57) | 908 (57) | 894 (90) | 12 (6) | 2 (1) | 388 (65) | 194 (74) | 194 (58) | <0.001* | |

| Heterosexual contact | 575 (33) | 523 (33) | 35 (4) | 155 (72) | 333 (89) | 169 (28) | 55 (21) | 114 (34) | ||

| Non-sexual contact/unknown | 170 (10) | 155 (10) | 65 (7) | 49 (23) | 41 (11) | 40 (7) | 13 (5) | 27 (8) | ||

| Years since HIV-1 diagnosis | ||||||||||

| <1 | 831 (49) | 761 (48) | 472 (48) | 126 (59) | 163 (44) | 260 (44) | 109 (42) | 151 (45) | 0.31* | |

| 1–3 | 442 (26) | 405 (26) | 261 (26) | 47 (22) | 97 (26) | 172 (29) | 76 (29) | 96 (29) | ||

| 3–5 | 182 (11) | 171 (11) | 113 (11) | 14 (7) | 44 (12) | 74 (13) | 29 (11) | 45 (14) | ||

| >5 | 255 (15) | 239 (15) | 143 (14) | 28 (13) | 68 (18) | 86 (15) | 45 (17) | 41 (12) | ||

| Perception of infectiousness | ||||||||||

| Not infectious | 91 (6) | 87 (6) | 32 (3) | 16 (8) | 39 (11) | 19 (3) | 6 (2) | 13 (4) | 0.07** | |

| Low | 153 (10) | 147 (9) | 95 (10) | 15 (8) | 37 (10) | 65 (11) | 35 (13) | 30 (9) | ||

| Medium | 420 (26) | 414 (26) | 259 (26) | 52 (27) | 103 (28) | 193 (31) | 93 (34) | 100 (29) | ||

| High | 933 (58) | 916 (59) | 614 (61) | 110 (57) | 192 (52) | 338 (55) | 137 (51) | 201 (58) | ||

| Type of alcoholic drinker | ||||||||||

| Abstainer | 537 (33) | 507 (32) | 235 (24) | 78 (38) | 194 (51) | 143 (24) | 52 (20) | 91 (27) | 0.13* | |

| Moderate/heavy drinker | 681 (41) | 657 (42) | 462 (47) | 76 (37) | 119 (31) | 274 (46) | 124 (48) | 150 (45) | ||

| Binge drinker | 426 (26) | 408 (26) | 289 (29) | 49 (24) | 70 (18) | 179 (30) | 84 (32) | 95 (28) | ||

| Stimulant drug use | ||||||||||

| Never used | 1,072 (64) | 1,023 (64) | 605 (61) | 148 (72) | 270 (69) | 377 (63) | 144 (55) | 233 (68) | <0.001* | |

| >1 month ago | 488 (29) | 468 (29) | 326 (33) | 41 (20) | 101 (26) | 178 (30) | 85 (33) | 93 (27) | ||

| Within last month | 103 (6) | 97 (6) | 60 (6) | 17 (8) | 20 (5) | 47 (8) | 31 (12) | 16 (5) | ||

| Desire to have more children | ||||||||||

| Yes/unsure | 644 (39) | 618 (39) | 424 (43) | 76 (36) | 118 (30) | 259 (43) | 115 (44) | 144 (42) | 0.62* | |

| No desire | 1005 (61) | 956 (61) | 553 (57) | 134 (64) | 269 (70) | 342 (57) | 145 (56) | 197 (58) | ||

| Sexual partner preference | ||||||||||

| MSM (any) | 1043 (63) | 1043 (63) | – | – | – | 444 (71) | 220 (80) | 224 (63) | <0.001* | |

| MSW (only) | 223 (13) | 223 (13) | – | – | – | 66 (10) | 10 (4) | 56 (16) | ||

| WSM/W | 401 (24) | 401 (24) | – | – | – | 119 (19) | 46 (17) | 73 (21) | ||

| Total sex partners in lifetime | ||||||||||

| ≤5 | 248 (19) | 239 (19) | 69 (8) | 40 (24) | 130 (43) | 72 (14) | 23 (10) | 49 (17) | <0.001** | |

| 6–20 | 481 (37) | 476 (37) | 288 (35) | 68 (40) | 120 (40) | 156 (29) | 51 (21) | 105 (36) | ||

| 21–50 | 282 (22) | 279 (22) | 212 (26) | 31 (18) | 36 (12) | 140 (26) | 65 (27) | 75 (26) | ||

| >50 | 299 (23) | 296 (23) | 250 (31) | 29 (17) | 17 (6) | 163 (31) | 100 (42) | 63 (22) | ||

| Number of partners in the last month | ||||||||||

| No partners | 482 (33) | 471 (33) | 281 (31) | 65 (36) | 125 (39) | |||||

| 1 | 678 (47) | 660 (47) | 387 (43) | 97 (53) | 176 (54) | 415 (65) | 161 (58) | 254 (71) | <0.001* | |

| >1 | 286 (20) | 282 (20) | 239 (26) | 20 (11) | 23 (7) | 222 (35) | 117 (42) | 105 (29) | ||

| Type of sexual partner in the past month | ||||||||||

| Primary only | 611 (42) | 596 (42) | 333 (37) | 93 (51) | 170 (52) | 372 (58) | 147 (53) | 225 (63) | 0.043* | |

| Non-primary only | 215 (15) | 209 (15) | 185 (20) | 13 (7) | 11 (3) | 148 (23) | 72 (26) | 76 (21) | ||

| Primary and non-primary | 141 (10) | 140 (10) | 109 (12) | 12 (7) | 19 (6) | 117 (18) | 59 (21) | 58 (16) | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Sex actsd

|

||||||||||

| (N = 767) | (N = 338) | (N = 429) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Partner serostatusd | ||||||||||

| HIV+ | – | – | – | – | – | 327 | 205 (63) | 122 (37) | ||

| HIV− | – | – | – | – | – | 292 | 72 (25) | 220 (75) | ||

| Unsure/don’t know | – | – | – | – | – | 148 | 61 (41) | 87 (59) | ||

Data are number (%) of patients; MSM, men who have sex with men; MSW, men who have sex with women only; WSM/W, women who have sex with men or women

Overall p value used *Chi square and **Wilcoxon rank sum tests

Of the 1810 participants, 4 did not report race/ethnicity, 87 did not report mode of transmission, 100 did not report years since HIV-1 diagnosis, 213 did not report perception of infectiousness, 166 did not report alcohol use, 146 did not report illicit drug use, 147 did not report stimulant use, 161 did not report desire for more kids, 500 did not report number of sex partners in lifetime, 364 did not report type of sexual partner, and 364 did not report number of partners in last month

Of the 1810 participants, 143 participants did not report sexual partner preference

Participants were able to contribute more than one response (total N = 637); total N reflects number of sex acts by partner serostatus

Reported Sexual Partners and Perception of Infectiousness

The baseline sexual behavior questionnaire was completed (at least partially) by 1707 (94 %) participants; numbers of respondents by question are provided in Table 2. Among those responding, 19 % reported 5 or fewer lifetime partners, 37 % reported 6–20, 22 % reported 21–50, and 23 % reported more than 50. Among responders, 33 % reported no partners in the past month, 47 % reported one partner and 20 % reported more than one partner; 42 % reported a primary partner only, 15 % reported non-primary partners only, and 10 % reported both primary and non-primary partners. There were notable differences in these distributions by sex and reported partner preference (Table 2).

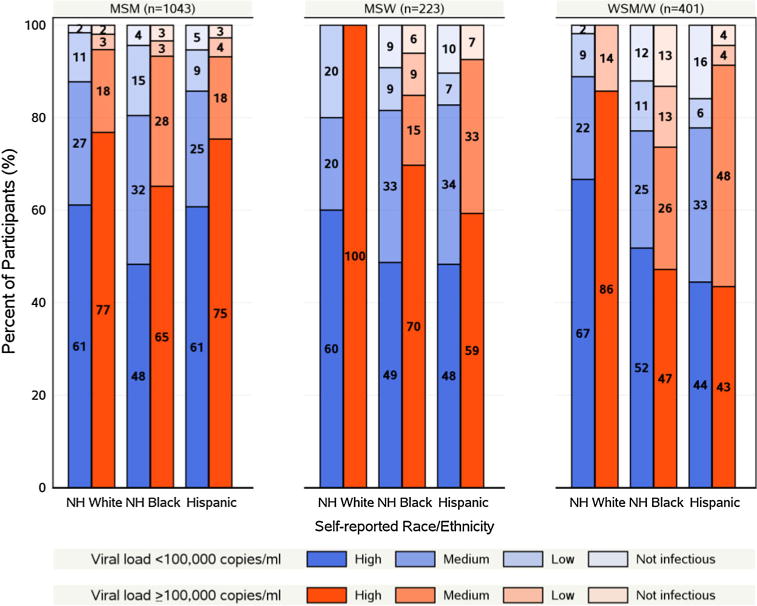

On a linear analog scale, the median perception of infectiousness was 78 (Q1–Q3 50–100). Based on our predefined categorization, 59 % considered themselves highly infectious, 26 % moderately infectious, and 9 % minimally infectious (highest, middle, and lowest thirds of the scale); 6 % considered themselves not infectious (providing a rating of 0 on a 0–100 scale) (Table 2). Of note, women were more likely to consider themselves as not infectious compared to men (11 vs 4 %); non-Hispanic blacks had the greatest proportions reporting as minimally or not infectious (58 and 50 %, respectively, among responders in these categories). Further evaluation of the perception of infectiousness by race/ethnicity and baseline HIV-1 RNA level revealed marked differences by race/ethnicity particularly among women (Fig. 1). While 65 and 75 % of non-Hispanic black and Hispanic MSM with higher baseline viral loads (>100,000 copies/ml) perceived themselves as highly infectious, only 47 and 43 % of their female counterparts reported the same perception of infectiousness. Similar differences were also apparent between Hispanic MSM versus Hispanic women with lower baseline viral loads (<100,000 copies/ml) reporting a high perception; 61 vs. 44 %, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Perception of infectiousness by baseline viral load, sex and sexual partner preference and race/ethnicity among A5257 Study Participants at Study Entry

Interestingly, participants reporting at least a college education or the highest income category (>$50,000) were more likely to report higher levels of perception of infectiousness. Perception of high infectiousness was also more commonly reported among those whose likely mode of HIV acquisition was homosexual intercourse compared to heterosexual intercourse (61 vs. 30 %, p = 0.003).

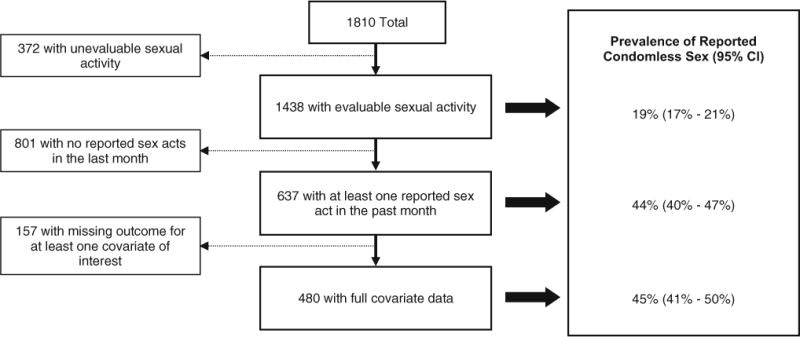

Population Reporting Condomless Sex

Among the 1438 with an evaluable outcome, the prevalence of condomless sex was 19 % (17, 21 %) (Fig. 2). Among those reporting sexual activity in the past month (n = 637), the prevalence of condomless sex was 44 % (40, 47 %).

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of reported condomless sex at baseline among A5257 Study Participants

Participants reporting condomless sex were more likely to be MSM (p < 0.001), to have a non-primary partner (p = 0.04), a greater number of lifetime partners (p < 0.001) and a greater number of partners in the past month (p < 0.001, Table 2). When accounting for partner serostatus, 63 % of sex acts with HIV-positive partners were non-condom protected, compared to 25 and 41 % of acts reported with HIV-negative or unknown serostatus partners, respectively (Table 2).

Interestingly, among 105 participants reporting multiple partners of differing serostatuses, 66 (63 %) of these indicated at least one unprotected sex act.

Predictors of Condomless Sex

Risk factors in the univariate analyses demonstrating moderate evidence of association with condomless sex included younger age, race/ethnicity, mode of HIV transmission, perception of infectiousness, stimulant drug use, type and number of partners in the past month, total number of lifetime partners and sexual partner preference. Evidence of collinearity was apparent between sexual partner preference, mode of transmission, and number of partners in the past month hence only sexual partner preference was retained in further models.

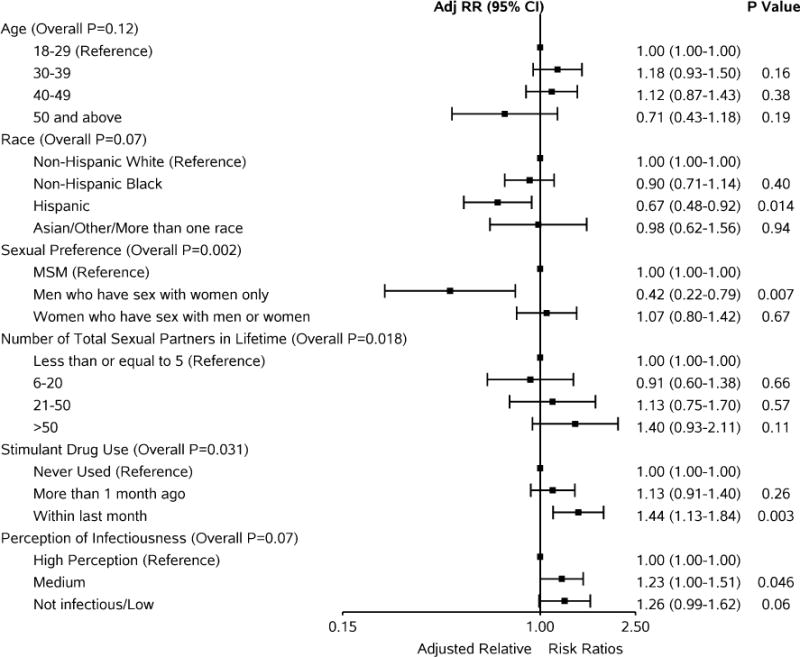

In adjusted analysis of risk factors associated with condomless sex (regardless of partner serostatus), a higher risk of condomless sex was associated with greater number of reported lifetime partners (p = 0.018) and recent stimulant drug use relative to participants reporting no drug use (p = 0.031). There was also evidence of a higher risk of condomless sex among those participants reporting low or medium perception of infectiousness relative to those with a high perception (p = 0.07, Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Adjusted relative risk ratios (95 % CI) for reported condomless sex at baseline (not accounting for partner serostatus)

The risk of condomless sex was lower for MSW compared to MSM (RR = 0.42, 95 % CI (0.22, 0.79); p = 0.007) and among those identifying as Hispanic race compared to those identifying as non-Hispanic white (RR = 0.67, 95 % CI (0.48, 0.92); p = 0.014). Relative to the lowest age group, no consistent trend was evident with increasing age and risk of condomless sex (p = 0.12), and there was no difference in the risk of condomless sex for women compared to MSM (RR = 1.07, 95 % CI (0.80, 1.42); p = 0.67).

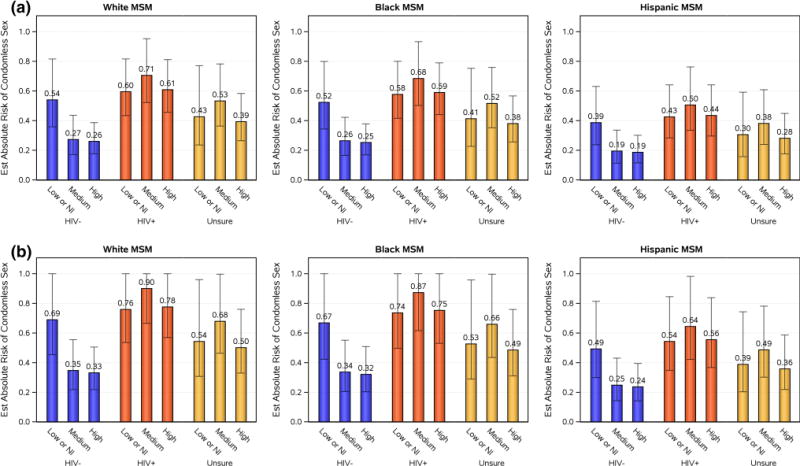

When adjusting for the effect of partner serostatus, the associations previously highlighted with the risk of condomless sex remained consistent but were attenuated (Fig. 4). Evidence of interaction between partner serostatus with self-reported perception of infectiousness was apparent (p = 0.05). Specifically, while the perception of infectiousness appeared to drive the risk of condomless sex in the setting of an HIV negative partner, this was not apparent in the setting of HIV-positive partners and partners of unknown serostatus.

Fig. 4.

Adjusted relative risk ratios (95 % CI) for reported condomless sex at baseline (accounting for partner serostatus)

This finding is illustrated via predicted absolute risk (95 % CI) of condomless sex for a subset of hypothetical individuals (Fig. 5). While the estimated risk of condomless sex with HIV-positive partners and with those of unknown serostatus is relatively consistent across all levels of perception of infectiousness, the estimated absolute risk of condomless sex with HIV-negative partners is markedly higher among participants perceiving themselves as low/non-infectious (range 0.39–0.69) compared to those participants perceiving themselves as medium or high perception of infectiousness (range 0.19–0.35, Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Estimates of predicted absolute risk of condomless sex with perception of infectiousness and partner serostatus among MSM 18–29 years of age and self-report of 21–50 sexual partners stratified by race and stimulant drug use. a No history of self-reported stimulant drug use. b Self-reported stimulant drug use in the past month. Note Error bars give 95 % confidence intervals. Due to small numbers, the “Asian/Other/More than one race” race/ethnicity group was excluded. Perception of infectiousness is defined as ‘Low or not infectious (NI)’, ‘medium’ or ‘high’ infectiousness perception; partner serostatus is defined as ‘HIV+’, ‘HIV−’, or ‘Unsure’ of partner serostatus

Sexual positioning with regards to partner serostatus was further examined among MSM participants reporting sexual activity in the past month (Table 3). Although small sample sizes precluded formal modeling of these data, observationally, differences in seropositioning behavior are apparent. Among MSM reporting sex acts with HIV negative or unknown serostatus partners, a greater proportion reported unprotected receptive acts compared to insertive acts (56 vs. 38 % and 50 vs. 41 %, respectively). In contrast, with HIV-positive partners, unprotected receptive and insertive experiences were reported in similar proportions (50 vs. 46 %).

Table 3.

Reported condomless sexual activity in the last month according to partner serostatus and positioning among MSM

| Positioning | HIV-positive

|

HIV-negative

|

Unsure of status

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | ≥1 | Total | 0 | ≥1 | Total | 0 | ≥1 | Total | |

| Number of condomless sex acts by partner serostatus (percent) | |||||||||

| Vaginal | 10 (8 %) | 11 (4 %) | 21 (6 %) | 20 (10 %) | 5 (6 %) | 25 (9 %) | 4 (4 %) | 6 (9 %) | 10 (6 %) |

| Receptive anal | 51 (43 %) | 123 (50 %) | 174 (48 %) | 113 (54 %) | 45 (56 %) | 158 (54 %) | 48 (52 %) | 33 (50 %) | 81 (51 %) |

| Insertive anal | 57 (48 %) | 113 (46 %) | 170 (47 %) | 77 (37 %) | 31 (38 %) | 108 (37 %) | 40 (43 %) | 27 (41 %) | 67 (42 %) |

Outcomes were restricted to MSM who reported sexual activity in the last month

Total column reflects number of MSM reporting sexual acts for the given positioning and partner serostatus combination; participants were able to contribute up to nine possible positioning and partner serostatus combinations

MSM, men who have sex with men

Discussion

To adequately “set the stage” for evaluating whether risk compensation occurs in a domestic population of HIV infected participants following initiation of ART, we aimed to rigorously characterize the TRB of the population immediately prior to ART initiation. Associations with TRB pre-ART provide important insights into those most at risk for risk compensation upon ART initiation. To date, evaluation of risk compensation accompanying initiation of ART in HIV-infected individuals has been largely limited to stable heterosexual serodiscordant couples as part of HIV prevention studies [4, 29]. However, increasing rates of STIs, particularly syphilis among HIV-infected MSM suggest that sexual behaviors capable of transmitting HIV are prevalent among some populations of HIV-infected MSM.

In A5257, we examined an HIV-infected population on the cusp of ART initiation as part of a randomized initial treatment trial. At this time point immediately prior to ART initiation, of those reporting at least one sex act in the past month, 44 % reported some condomless sex; nearly three quarters of those whose HIV was likely acquired through MSM contact reported some condomless sex. Increased risks for condomless sex included higher numbers of total lifetime partners, recent stimulant drug use, lower perception of infectiousness and an HIV-positive or unknown serostatus partner. This is consistent with attributable risk data and national epidemiology showing that the largest burden of new HIV infections are among MSM, and a large portion of MSM risk behavior is associated with methamphetamine use [30, 31].

Condomless sex was less prevalent among men who reported sex only with women, and also among participants reporting Hispanic ethnicity, compared to non-Hispanic white participants. Future fertility goals did not appear to be associated with rates of condomless sex, for men or women—suggesting that procreation was not the (sole) motivator for condomless intercourse among heterosexual individuals—at least at the moment immediately prior to ART initiation.

Evidence of serosorting was also apparent in this HIV-infected population. We observed that while perception of infectiousness drove the risk of condomless sex in the setting of HIV-negative serostatus partner, a relatively high risk of condomless sex was evident with HIV-positive partners regardless of the perception of infectiousness; the risk of condomless sex in the setting of partners of unknown serostatus was intermediate. We also found that women were more likely to report a perception of low or non-infectiousness compared to men, despite similar baseline viral loads between men and women. This finding may reflect an accurate perception by women of receptive vaginal intercourse as lower risk for HIV-transmission from an HIV-infected woman to an HIV-uninfected man compared to transmission from an infected man to an uninfected woman. Adjusting for perception of infectiousness and partner serostatus left only a lower risk for MSW and a higher risk for recent stimulant users. Unpacking the finding of increased condomless sex with a reduced perception of infectiousness, we found that low/no perception of infectiousness tended to be disproportionately likely among participants reporting lower socioeconomic status and black race. These results suggest a potential opportunity for additional HIV transmission risk prevention education and interventions to remind populations that pre-ART initiation remains a high-risk scenario for transmission. Interestingly, our descriptive assessment of seropositioning suggested a lower prevalence of condomless insertive sexual activity compared to receptive activity with HIV-negative and unknown serostatus partners. Unfortunately small sample sizes precluded a more robust examination of this issue.

Estimations of predicted absolute risk of condomless sex across categories of number of lifetime sexual partners, race/ethnicity groups and perceptions of infectiousness for MSM are illustrative in defining groups most at-risk for reporting condomless sex at high levels (as high as almost 90 %). We used the models generated from analyses of A5257 data to describe a hypothetical cohort that informs the predicted absolute risks of condomless sex in a theoretical cohort of HIV-infected individuals. For example, for an HIV-positive 21 year old white MSM reporting a moderate number of lifetime sexual partners, who considers himself of moderate infectiousness and has a history of stimulant drug use in the past month, the estimated absolute risk of reporting condomless sex in the past month was 90 %; in contrast, a similar individual without a history of stimulant drug use had an estimated risk of 71 % (Fig. 5). It is reassuring to note lower absolute risks of condomless sex with HIV-uninfected partners for this population as perception of infectiousness increased, with no assurance that their self-perception of infectiousness is, in fact, correct—this finding at the very least suggests appropriate concern for horizontal transmission of HIV to sexual partners.

We recognize the limitations inherent with self-reported data, including social desirability bias and misreported information, and particularly with the topics of sexual behavior and recreational drug use. The paper-based questionnaire (compared to a computer-aided questionnaire) also resulted in missing data from skip patterns and limited questionnaire responses. We addressed these issues through a pre-defined set of imputations and based interpretations and inferences on the consistency, trend and magnitude of the observed effects sizes in conjunction with the level of statistical evidence. The restriction of this analysis to participants reporting recent sexual activity prior to ART initiation also restricted our study population and question of interest and is not necessarily generalizable to those individuals who reported no recent sexual activity, or to behavior after ART has been initiated. There is evidence to suggest differences between these two groups with respect to baseline and sexual behavior characteristics; however, it is not possible to discern from this analysis—or from the data captured as part of the study—whether participants not reporting sexual activity are mindfully avoiding sexual activity, do not have an active partner during the period targeted on the questionnaire, prefer not to answer such questions, or a combination of these reasons or for another reason entirely. Additionally, this baseline cross-sectional analysis does not allow us to address the most pressing clinical and public health question: Is ART-initiation associated with changes in TRB over time? This longitudinal analysis is ongoing.

These results, however, indicate an opportunity for HIV-prevention at a moment in time when individuals are embarking on ART. Once such individuals become virologically suppressed on ART, their risk of ongoing secondary transmission is minimized. However, during the period prior to and around the time of ART initiation, behavior, and condomless sex in particular, will be the ultimate governor of HIV transmission. Understanding perception of risk and recreational stimulant use among pre- and early ART using individuals, particularly among MSM, creates an educational and interventional opportunity with the potential to reduce new HIV infections.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by Award Number U01AI068636 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and supported by National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases or the National Institutes of Health. The study team would like to additionally thank the ACTG CRS’s that conducted the A5257 protocol and the A5257 study participants. The protocol received support from the AIDS Clinical Trials Group, the Site Data Management Center Grant of UM1AI68634, the ACTG specialty laboratories listed in the manuscript, and the clinical research sites. From the sites we acknowledge the following personnel and AIDS Clinical Trials Unit Grants: Michelle Saemann, RN and Jennifer Baer, RN- Cincinnati CRS (Site 2401) Grant AI069439; Dr. Susan Koletar, Mark Hite RN- Ohio State University CRS (Site 2301) Grant UM1AI069494; Linda Meixner, RN and Edward Seefried, RN- UCSD Antiviral Research Center CRS (Site 701) Grant AI69432; Vicki Bailey, RN and Rebecca Basham, CCRP- Vanderbilt Therapeutics CRS (Site 3652) Grant 2UM1AI069439-08, CTSA Grant UL1 TR000445; David Currin RN and Miriam Chicurel-Bayard RN- Chapel Hill CRS (Site 3201) Grant UM1 AI069423-08, CTSA Grant 1UL1TR001111, CFAR Grant P30 AI50410; Teresa Spitz and Judy Frain- Washington University Therapeutics CRS (Site 2101) Grant UM1AI069439; Elizabeth Lindsey, RN and Tamara James - Alabama Therapeutics CRS (Site 5801) Grant 2UM1AI069452-08; Beverly Putnam and Cathi Basler- University of Colorado Hospital CRS (Site 6101) Grant 2UM1AI069432, CTSA Grant UL1 TR001082; Michael P. Dube, MD and Bartolo Santos, RN- University of Southern California CRS (Site 1201) Grant AI069432; Eric Daar and Sadia Shaik -Harbor UCLA CRS (Site 603) Grant AI069424, CTSA Grant UL1TR000124; Pablo Tebas MD and Aleshia Thomas RN, BSN- Penn Therapeutics CRS (Site 6201) Grant UM1-AI069534-08, CFAR Grant 5-P30-AI-045008-15; Roger Bedimo, MD and Michelle Mba, MPH-Trinity Health and Wellness Center (Site 31443) Grant U01 AI069471; David Cohn MD and Fran Moran RN- Denver Public Health CRS (Site 31470) Grant UM1 AI069503; Jorge L. Santana Bagur, MD and Ileana Boneta Dueño, RN- Puerto Rico AIDS Clinical Trials Unit CRS (Site 5401) Grant 2UM1AI069415-09; Babafemi Taiwo, MBBS, Baiba Berzins, MPH- Northwestern University CRS (Site 2701) Grant 5U01 AI069471; Dr. Emery Chang and Maria Palmer- UCLA CARE Center CRS (Site 601) Grant A1069424; Mary Adams, RN and Christine Hurley, RN - Univ. of Rochester ACTG CRS/AIDS CARE CRS/Trillium Health (Site 1101/Site 1108) Grant 2UM1 AI069511-08, CTSA Grant UL1 TR024160; Timothy Lane and Cornelius Van Dam-Greensboro CRS (Site 3203) Grant A1069423-08; Karen Tashima MD and Helen Patterson LPN - The Miriam Hospital (TMH) CRS (Site 2951) Grant 2UM1A1069412-08; Carlos del Rio, MD & Ericka Patrick, RN- The Ponce de Leon Ctr. CRS (Site 5802) Grant 2UM1 AI069418-08, CFAR Grant P30 AI050409, CTSA Grant UL1 TR000454; Norman Markowitz and Indira Brar- Henry Ford Hosp. CRS (Site 31472) Grant UM 1 A1069503; Roberto C. Arduino, MD, and Maria Laura Martinez- Houston AIDS Research Team CRS (Site 31473) Grant 2 UM1 AI069503-08, 2 UM1 AI068636-08; Rose Kim, MD and Yolanda Smith, BA- Cooper Univ. Hosp. CRS (Site 31476) Grant UM1 AI069503; Hector Bolivar, MD, Margaret A. Fischl, MD -Univ. of Miami AIDS Clinical Research Unit (ACRU) CRS (Site 901) Grant AI069477; Edward Telzak, MD and Richard Cindrich, MD-Bronx-Lebanon Hosp. Ctr. CRS (Site 31469) Grant UM1 AI069503; Paul Sax MD and Cheryl Keenan RN BC- Brigham and Women’s Hospital Therapeutics CRS (Site 107) Grant UM1AI069472; CFAR Grant P30 AI060354, CTSA UL1 TR000170; Kim Whitely, RN and Traci Davis, RN- MetroHealth CRS (Site 2503) Grant AI 69501; CTSA Grant UL1TR000439; Dr. Rodger D. MacArthur and Marti Farrough, RN, BSN - Wayne State Univ. CRS (Site 31478) Grant 2UM1AI069503-08; Judith A. Aberg, MD and Michelle S Cespedes, MPH, MD - NY Univ. HIV/AIDS CRS (Site 401) Grant UM1 AI069532; Shelia Dunaway, MD and Sheryl Storey, PA-C- University of Washington AIDS CRS (Site 1401) Grant UM AI069481; Joel Gallant, MD, and Ilene Wiggins, RN - Johns Hopkins University CRS (Site 201) Grant 2UM1 AI069465, CTSA Grant UL1TR001079; Beverly Sha, MD and Veronica Navarro, RN - Rush University CRS (Site 2702) Grant AI-069471; Vicky Watson RN and Daniel Nixon DO, PhD - Virginia Commonwealth Univ. Medical Ctr. CRS (Site 31475) CPCRA CTU award UM1 AI069503, CTSA UL1TR000058; Annie Luetkemeyer, MD and Jay Dwyer, RN- UCSF HIV/AIDS CRS (Site 801) Grant UM1 AI069496, UCSF-CTSA Grant UL1 TR000004; Kristen Allen RN and Patricia Walton RN- Case CRS (Site 2501) Grant AI069501; Dr. Princy Kumar and Dr. Joseph Timpone- Georgetown University CRS (Site 1008) Grant 1U01AI069494; Mehri McKellar, MD and Jacquelin Granholm, RN- Duke Univ. Med. Ctr. Adult CRS (Site 1601) Grant 5UM1 AI069484-07; Michael T Yin, MD MS and Madeline Torres, RN- Columbia Physicians and Surgeons CRS (Site 30329) Grant 2UM1-AI069470-08, CTSA 5UL1 RR024156; Sandra Valle, PA-C and Debbie Slamowitz, RN- Stanford CRS (Site 501) Grant AI069556; Charles E. Davis Jr., M.D. and William A. Blattner, M.D. - IHV Baltimore Treatment CRS (Site 4651) Grant U01AI069447; BMC ACTG CRS (Site 104) Benjamin Linus, MD, UM1 AI069472; Beth Israel Deaconess Med. Ctr., ACTG CRS (Site 103) Mary Albrecht, MD, UM1 AI069472; CFAR Grant P30 AI060354; Christina Megill, PA-C and Valery Hughes, NP- Cornell Chelsea CRS (Site 7804) Grant UM1AI069419, CTSA Grant UL1TR000457; Teri Flynn, MSN, ANP and Amy Sbrolla BSN, RN -Massachusetts General Hospital CRS (Site 101) Grant 2UM1AI069412-08; CFAR Grant P30 AI060354; Sharon Riddler, MD and Lisa Klevens, BSN- University of Pittsburgh CRS (Site 1001) Grant UM1 AI069494.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10461-016-1365-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data—United States and 6 US dependent areas—2010. 2012;17(3) part A. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/surveillance/2010/surveillance_Report_vol_17_no_3.html. Accessed 6 Aug 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV incidence among adults and adolescents in the United States 2007–2010. 2012 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/slideSets/index.html. Accessed 6 Aug 2015.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report: diagnoses of HIV infection and aids in the united states and dependent areas. 2011;23 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/surveillance/2011/surveillance_Report_vol_23.html. Accessed 6 Aug 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jia Z, Ruan Y, Li Q, et al. Antiretroviral therapy to prevent HIV transmission in serodiscordant couples in China (2003–11): a national observational cohort study. The Lancet. 2012;382(9899):1195–203. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61898-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Granich RM, Gilks CF, Dye C, De Cock KM, Williams BG. Universal voluntary HIV testing with immediate antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for elimination of HIV transmission: a mathematical model. The Lancet. 2009;373(9657):48–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61697-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, del Rio C, Burman WJ. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(6):793–800. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanna DB, Buchacz K, Gebo KA, et al. Trends and disparities in antiretroviral therapy initiation and virologic suppression among newly treatment-eligible HIV-infected individuals in North America, 2001–2009. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(8):1174–82. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schechter M, do Lago RF, Mendelsohn AB, Moreira RL, Moulton LH, Harrison LH. Behavioral impact, acceptability, and HIV incidence among homosexual men with access to postexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV. J Acquir Immun Defic Syndr. 2004;35(5):519–25. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200404150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin JN, Roland ME, Neilands TB, et al. Use of postexposure prophylaxis against HIV infection following sexual exposure does not lead to increases in high-risk behavior. AIDS. 2004;18(5):787–92. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200403260-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, et al. Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):423–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):399–410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen CR, Montandon M, Carrico AW, et al. Association of attitudes and beliefs towards antiretroviral therapy with HIV-seroprevalence in the general population of Kisumu, Kenya. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(3):e4573. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maughan-Brown B, Venkataramani AS. Learning that circumcision is protective against HIV: risk compensation among men and women in Cape Town, South Africa. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(7):e40753. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagelkerke NJ, Hontelez JA, de Vlas SJ. The potential impact of an HIV vaccine with limited protection on HIV incidence in Thailand: a modeling study. Vaccine. 2011;29(36):6079–85. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson TE, Gore ME, Greenblatt R, et al. Changes in sexual behavior among HIV-infected women after initiation of HAART. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(7):1141–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reynolds SJ, Makumbi F, Nakigozi G, et al. HIV-1 transmission among HIV-1 discordant couples before and after the introduction of antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2011;25(4):473–7. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283437c2b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pearson CR, Cassels S, Kurth AE, Montoya P, Micek MA, Gloyd SS. Change in sexual activity 12 months after ART initiation among HIV-positive Mozambicans. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(4):778–87. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9852-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McClelland RS, Graham SM, Richardson BA, et al. Treatment with antiretroviral therapy is not associated with increased sexual risk behavior in Kenyan female sex workers. AIDS. 2010;24(6):891–7. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833616c7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luchters S, Sarna A, Geibel S, et al. Safer sexual behaviors after 12 months of antiretroviral treatment in Mombasa, Kenya: a prospective cohort. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2008;22(7):587–94. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eisele TP, Mathews C, Chopra M, et al. High levels of risk behavior among people living with HIV Initiating and waiting to start antiretroviral therapy in Cape Town South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(4):570–7. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9279-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Apondi R, Bunnell R, Ekwaru JP, et al. Sexual behavior and HIV transmission risk of Ugandan adults taking antiretroviral therapy: 3 year follow-up. AIDS. 2011;25(10):1317–27. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328347f775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bouhnik AD, Moatti JP, Vlahov D, Gallais H, Dellamonica P, Obadia Y. Highly active antiretroviral treatment does not increase sexual risk behaviour among French HIV infected injecting drug users. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56(5):349–53. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.5.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bunnell R, Ekwaru JP, Solberg P, et al. Changes in sexual behavior and risk of HIV transmission after antiretroviral therapy and prevention interventions in rural Uganda. AIDS. 2006;20(1):85–92. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000196566.40702.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shafer LA, Nsubuga RN, White R, et al. Antiretroviral therapy and sexual behavior in Uganda: a cohort study. AIDS. 2011;25(5):671–8. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328341fb18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lennox JL, Landovitz RJ, Ribaudo HJ, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of 3 nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-sparing antiretroviral regimens for treatment-naive volunteers i nfected with HIV-1: a randomized, controlled equivalence trial. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(7):461–71. doi: 10.7326/M14-1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zou GY, Donner A. Extension of the modified Poisson regression model to prospective studies with correlated binary data. Stat Methods Med Res. 2013;22(6):661–70. doi: 10.1177/0962280211427759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jean K, Gabillard D, Moh R, et al. Effect of early antiretroviral therapy on sexual behaviors and HIV-1 transmission risk among adults with diverse heterosexual partnership statuses in Cote d’Ivoire. J Infect Dis. 2014;209(3):431–40. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koblin B, Husnik M, Colfax G, et al. Risk factors for HIV infection among men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2006;20:731–9. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000216374.61442.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ostrow DG, Plankey MW, Cox C, et al. Specific sex drug combinations contribute to the majority of recent HIV seroconversions among MSM in the MACS. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51(3):349–55. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a24b20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.