Structured Abstract

Purpose

There is substantial heterogeneity within human papillomavirus (HPV) associated head and neck cancer (HNC) tumors that predispose them to different outcomes, however the molecular heterogeneity in this subgroup is poorly characterized due to various historical reasons.

Experimental Design

We performed unsupervised gene expression clustering on deeply-annotated (transcriptome and genome) HPV(+) HNC samples from two cohorts (84 total primary tumors), including 18 HPV(−) HNC samples, to discover subtypes and characterize the differences between subgroups in terms of their HPV characteristics, pathway activity, whole-genome somatic copy number alterations and mutation frequencies.

Results

We identified two distinct HPV(+) subtypes (namely HPV-KRT and HPV-IMU). HPV-KRT is characterized by elevated expression of genes in keratinocyte differentiation and oxidation-reduction process, whereas HPV-IMU has strong immune response and mesenchymal differentiation. The differences in expression are likely connected to the differences in HPV characteristics and genomic changes. HPV-KRT has more genic viral integration, lower E2/E4/E5 expression levels and higher ratio of spliced to full length HPV oncogene E6 than HPV-IMU; the subgroups also show differences in copy number alterations and mutations, in particular the loss of chr16q in HPV-IMU and gain of chr3q and PIK3CA mutation in HPV-KRT.

Conclusion

Our characterization of two subtypes of HPV(+) HNC tumors provides valuable molecular level information that point to two main carcinogenic paths. Together, these results shed light on stratifications of the HPV(+) HNCs and will help to guide personalized care for HPV(+) HNC patients.

Keywords: Head and neck cancer, human papillomavirus

Introduction

Head and neck cancer (HNC) affects approximately 600,000 patients per year globally, and with five-year survival rates ranging from 37 to 62 percent (1). The majority of HNC cases have been historically attributed to excessive use of carcinogens such as tobacco and alcohol, but a significant and increasing proportion of cases are associated with high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. In fact, it is predicted that by 2020 the number of HPV(+) HNC cases will outnumber cervical cancer cases (2). Similar to cervical cancer, HPV type 16 is the most common high risk type, accounting for 87% of HPV(+) cases in oropharyngeal HNC, 68% in oral HNC and 69% in laryngeal HNC (3,4). Currently, approximately 75% of oropharyngeal tumors are associated with HPV; the prevalence of HPV in non-oropharyngeal sites such as oral cavity and larynx is relatively rare but still occurs (5,6). Overall, HPV(+) HNC patients tend to have more favorable prognosis and treatment response rates, and different patient characteristics such as younger age at diagnosis, lower smoking rate, and higher intake of beneficial micronutrients compared to their HPV(−) counterparts (7–9). They also have key molecular differences, such as the observed high expression of p16 (CDKN2A) in HPV(+) tumors and loss of p16 expression in HPV(−) tumors, and HPV(+) tumors are generally less-differentiated (10) and have different copy number profiles (11) compared to HPV(−) tumors.

HPV normally infects the basal layer of the epithelium, and then exploits the epithelial-to-keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation pathways in order to complete the viral life cycle. HPV expresses two main viral oncoproteins, E6 and E7, which cooperatively inhibit apoptosis and enhance tumor cell growth and proliferation by inducing degradation of tumor suppressor p53 and disruption of function of the retinoblastoma protein (Rb), respectively (12). Alteration of additional pathways, such as suppression of immune response(13) and cell adhesion(14), and induction of DNA damage(15) and oxidative stress(16), may also be important for tumor transformation.

High-risk HPV E6 is expressed in cells as two main isoforms: a full-length variant (E6) and truncated variants often collectively referred to as E6*. It was shown that E6* inversely regulates the ability of E6 to degrade p53 (17). Full-length E6 and E6* also bind to different sites of procaspase 8 and alternatively modulate its stability (destabilizing and stabilizing, respectively) (18). The ratio of spliced E6 also correlated with outcomes in HPV positive oropharyngeal patients (19). In addition to the combined oncogenic potential of the E6 and E7 proteins, the integration of part or all of the HPV genome into the host genome is suggested to trigger focal genomic instability and further drive the neoplastic process, and is estimated to occur in 75% of HNC cases, of which an estimated 54% are integrated into a known gene (20,21). Integrated viral transcripts are more stable than those derived from episomal HPV (22), and integration confers an increased proliferative capacity and selective growth advantage (12,22). Expression of these transcripts is key, as it has been observed that tumors positive for HPV DNA, but negative for HPV RNA, have similar gene expression and TP53 mutation frequencies as HPV(−) tumors (23).

Several studies have investigated the differences in gene expression and copy number changes between HPV(+) and HPV(−) tumors (24,25), or have defined gene expression subtypes of HNCs irrespective of HPV status (26,27). To date, only two studies have identified expression subtypes of HPV(+) HNCs (24,28); both studies used microarray data, thus limiting their ability to comprehensively characterize the differences between subtypes and identify the underlying causes of the expression differences. Here, by deep analyses of 36 HNC tumors (18 HPV(+); 18 HPV(−)) collected at the University of Michigan with transcriptome and whole genome copy number alterations (CNA) data, we define two robust HPV(+) subtypes distinguished by gene expression patterns. Membership in the two subgroups correlates with genic viral integration status, E2/E4/E5 expression and E6 splicing ratio. In addition, the clusters show different CNA patterns, mutation frequencies in PIK3CA and expression of cancer-relevant pathways, such as host immune response and keratinocyte differentiation. Validation analyses carried out on 66 additional HPV(+) HNC samples from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) yielded the same findings, demonstrating the robustness of the subtypes and their related characteristics.

Methods

Tumor tissue acquisition, DNA and RNA extraction

As a part of our ongoing survivorship cohort, we identified incident cases of HNC patients at University of Michigan hospital with untreated oropharynx or oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma between 2011 – 2013. Written informed consent was obtained, and the study was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board. Pretreatment tumor tissue and blood were collected into a cryogenic storage tube and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen by surgical staff until storage at −80C. The flash frozen tissues were embedded in OCT media in vinyl cryomolds on dry ice and stored in −80C until prepared for histology. H&E slides were sectioned from each frozen tumor specimen on a cryostat and assessed by a board certified, HNC expert pathologist for degrees of cellularity and necrosis. Criteria used for inclusion in the study were a minimum of 70% cellularity and less than 10% necrosis. The first 36 tumors meeting these criteria were selected. Using a sterile scalpel, surface scrapings were taken directly from the frozen tissue blocks from the region of tissue identified as having at least 70% tumor cellularity, over dry ice to allow the tissue to remain frozen. Frozen scrapings were placed into pre-chilled tubes on dry ice and processed using the Qiagen AllPrep DNA/RNA/Protein Mini Kit (Valencia, CA, USA) as per manufacturer protocol. Blood DNA from the same patients was isolated using the Qiagen QIAamp Blood DNA Mini Kit.

RNA-seq and SNP-array protocol

RNA library construction and sequencing on Illumina HiSeq using 100 nt paired-end reads were performed by the University of Michigan DNA sequencing Core Facility. Samples were multiplexed and ran on multiple lanes to avoid lane variations. DNA isolates from all tumors and matched blood samples were run on the Illumina HumanOmniExpress BeadChip SNP-array. The raw microarray images were processed by Illumina Genome Studio to yield the log R ratio (LRR) values and B allele frequency (BAF) values. Raw and processed RNA-seq and SNP-array data can be accessed from GEO with the accession number GSE74956.

RNA-seq analysis

The RNA-seq libraries were aligned to both human and HPV genomes to quantify the host and viral gene expression and determine HPV status. Samples were classified as HPV(+) if they had more than 500 read pairs aligned to any HPV genome. Of all 36 tumors, we identified 14 HPV type16, one type18, one type33, and two type35. Virus genic integration events were detected using VirusSeq (29). Full-length E6 percent was calculated as the ratio of full-length E6 over all E6 transcripts. Variant calling was performed following GATK Best Practices on RNA-seq data (30), and the resulting variants were filtered to leave only the ones predicted to be damaging. RNA-seq fastq files of 66 TCGA HPV+ tumor samples were downloaded from cghub (31). The data were re-aligned and analyzed in the same way as UM RNA-seq data described above, except for variant calling. Gene somatic mutations for TCGA samples were instead downloaded from Xena (32). See Supplementary Methods for additional RNA-seq analysis details.

Subtype discovery and pathway scores

Standard hierarchical clustering and consensus clustering methods (33) were both performed on gene expression matrices and produced consistent results. The cluster memberships were robust to the choices of different clustering parameters and number of top variable genes. Sample-wise pathway scores were computed as aggregated ranks of gene expression levels for four selected representative gene sets: E6 regulated genes, EMT genes, T-cell activation (GO: 0042110) and keratinocyte differentiation (GO: 0030216). See supplementary methods for details.

CNA analysis

OncoSNP v2.1 was run on every tumor and matched normal, with the setting that the maximal possible stromal contamination is 0.5 (34). The level 1 through level 5 CNA output data from OncoSNP were overlaid to provide the final CNA calls. The copy number for each gene was calculated as the average copy number of the segments overlapping the gene rounded to the nearest integer. Segmented whole genome copy number variation data for TCGA samples were downloaded from TCGA data portal. The copy number values for TCGA samples were stored as log2 ratios of the tumor probe intensity to the normal intensity. Gene-level CNAs for PIK3CA were downloaded from Xena (32) for TCGA samples.

Results

Overview of differential expression results from HPV(+) and HPV(−) tumors

We performed transcriptomic analysis via RNA-deep sequencing on 36 tumor samples (18 HPV+ and 18 HPV-) to define gene expression levels. Supervised differential expression analysis using HPV status as the group variable identified 1887 and 1644 genes significantly up-regulated and down-regulated in HPV(+) samples, respectively (false discovery rate (FDR)<0.05 and absolute fold change>2). We annotated the genes to neoplasm-related terms downloaded from Gene2MeSH (35), and re-identified several important differentially expressed genes: TP53, CDKN2A, BRCA2, CYP2E1, KIT and EZH2 were significantly up-regulated in HPV(+) tumors, and CCND1, GSTM1, HIF1A, MMP2, CD44 and MET were down-regulated (Table S1).

We performed Gene Ontology enrichment analysis with LRpath (36) and found that “immune response”, “cell cycle”, and “DNA replication” were up-regulated in HPV(+) samples compared to HPV(−), whereas “extracellular matrix” and “epithelium development” were up-regulated in HPV(−) samples (Table S2). These findings are consistent with what has been previously reported (24). Enrichment analysis with cytobands identified several locations on 11q (11q13, 11q22.3 and 11q23.3) as enriched for genes up-regulated in HPV (−) samples. This may be driven by frequent focal amplification of 11q13 and 11q22 in HPV(−) samples and deletion of the far end of chr11q in HPV(+) samples (Fig S1) (27).

Unsupervised clustering revealed two HPV(+) subgroups

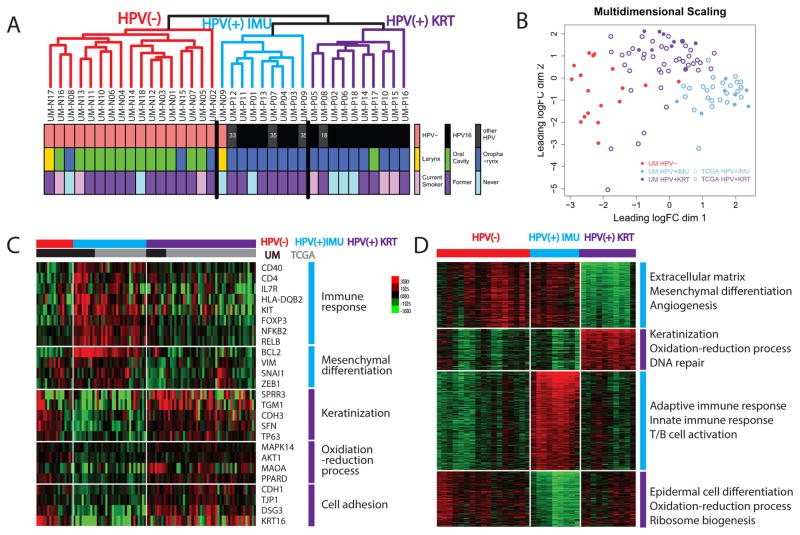

Unsupervised clustering using the 6922 most variably expressed genes among all samples revealed three distinct groups ( 1A and Fig S2A). First, HPV(−) samples were distinguished from HPV(+) samples, except for one HPV(−) sample which clustered with HPV(+) samples. The 18 HPV(+) samples separated into two clusters of 8 and 10 HPV(+) samples. These clustering results were robust to various clustering metrics (Euclidean distance, centered or uncentered Pearson’s correlation), linkages (single, average or robust) and different numbers of top variable genes used. To assure that the clusters we found are generalizable and not limited to our cohort, we included 66 additional HPV(+) samples from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) HNC cohort, and then performed unsupervised clustering on the 84 HPV(+) samples combined. Again, two clusters were robustly identified (Fig 1B and Figure S2B]. The clusters were not associated with smoking history, anatomical site, clinical N stage or tumor stage, but were correlated with gender, clinical T stage and HPV type (α-level = 0.05), although we were underpowered to compare most epidemiologic characteristics (Fig 1A and Table 1).

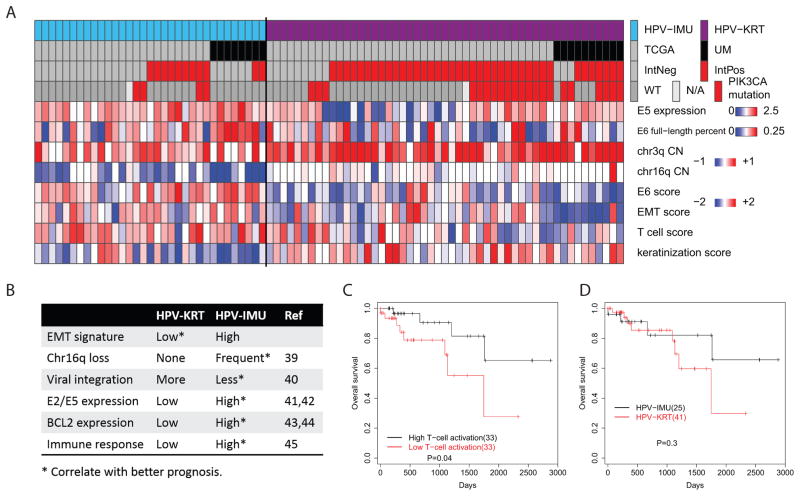

Figure 1. Identification of two HPV(+) subgroups and pathway differences between them.

(A) Hierarchical clustering (shown here) and consensus clustering (Fig S1A) revealed two distinct HPV(+) clusters in the UM cohort. (B) Multi-Dimensional Scaling plot displaying the relationship among combined UM (n=36) and TCGA (n=66) samples by subgroup. The HPV-KRT subgroup is more similar to the non-HPV samples than is the HPV-IMU subgroup. (C) Heatmap showing representative genes/pathways different between HPV-KRT and HPV-IMU. (D) Heatmap showing the top differentially expressed genes (and pathways) among the three clusters from UM cohort. The genes were grouped by their expression signatures across the three clusters. The genes used to generate this heatmap are listed in Table S5.

Table 1.

Patient demographics.

| UM tumors | TCGA tumors | p-valuea | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Non-HPV | HPV-KRT | HPV-IMU | Total | HPV-KRT | HPV-IMU | ||

|

| ||||||||

| 36 | 18 | 10 | 8 | 66 | 41 | 25 | ||

| Age | ||||||||

| Median (std) | 56.5(10) | 55.5(6.8) | 62.5(6.7) | 58(10) | 57 (7.8) | 0.38 | ||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 26 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 60 | 35 | 25 | 0.039 |

| Female | 10 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 0 | |

| HPV type | ||||||||

| HPV16 | 14 | 9 | 5 | 55 | 37 | 18 | 0.022 | |

| HPV18 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| HPV33 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 3 | 5 | ||

| HPV35 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Anatomical Site | ||||||||

| Oropharynx | 20 | 3 (17%) | 9 (90%) | 8 (100%) | 47 | 26 (63%) | 21 (84%) | 0.051 |

| Oral Cavity | 14 | 13 (72%) | 1 (10%) | 0 | 16 | 13 (32%) | 3 (12%) | |

| Larynx | 2 | 2 (11%) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 (4%) | |

| Hypopharynx | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 (5%) | 0 | |

| Tumor Stage | ||||||||

| I-II | 5 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 6 | 6 | 0.27 |

| III | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 4 | |

| IV | 28 | 13 | 9 | 6 | 22 | 32 | 15 | |

| T stage | ||||||||

| T1–T2 | 14 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 23b | 16 | 0.045 | |

| T3–T4 | 22 | 12 | 7 | 3 | 27 | 7 | ||

| N stage | ||||||||

| N0 | 10 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 12c | 6 | 0.64 | |

| N1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | ||

| N2 | 17 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 25 | 14 | ||

| N3 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | ||

| Smoking | ||||||||

| Never | 7 | 3(17%) | 3(30%) | 1(13%) | 22 | 11 (27%) | 11 (44%) d | 0.66 |

| Former | 23 | 12(66%) | 4(40%) | 7(87%) | 30 | 23 (56%) | 7 (28%) | |

| Current | 6 | 3(17%) | 3(30%) | 0 | 13 | 7 (17%) | 6 (24%) | |

tests were performed between HPV-KRT and HPV-IMU for both cohorts combined. Wilcoxon rank sum test was performed for age, whereas Fisher’s exact test was used for other variables. For HPV type, HPV16 versus others combined was tested. For anatomical sites, only oropharynx versus oral cavity was tested due to insufficient tumors from other sites. For N stage, N0, N1 versus N2, N3 was tested.

There was one missing value for each of these features (all from different samples).

Differentially regulated genes and pathways between HPV(+) subgroups

We next characterized the molecular differences between the HPV(+) subgroups. Differential expression analysis between the two HPV(+) clusters found 3515 genes significantly differentially expressed (absolute fold change>2 and FDR<0.05). Up-regulated genes in one cluster were enriched for “immune response”, “mesenchymal cell differentiation” and various differentiation and development-related terms; up-regulated genes in the other cluster were most significantly enriched for “keratinocyte differentiation” and “oxidative reduction process” (complete list in Table S3). Therefore, we named the clusters HPV-IMU and HPV-KRT respectively. The top differentially expressed genes from each relevant gene set are shown in Fig 1C, including BCL2 for mesenchymal differentiation, CDH3 and TP63 for keratinization, and CDH1 and KRT16 for cell adhesion. To understand how the pathways were dysregulated in the context of all HNC tumors, we compared each HPV(+) cluster to the other cluster and HPV(−) samples, and identified pathways that were uniquely up- or down-regulated (see supplementary methods). Enrichment testing results showed remarkably elevated immune response in HPV-IMU, consisting of increased T-cell activation, B-cell activation, and lymphocyte activation, and repression of both mesenchymal differentiation and extracellular matrix-related expression in HPV-KRT; it also showed increased keratinization/epidermal differentiation and oxidative-reduction process gene expression in HPV-KRT relative to HPV-IMU, with mixed expression in the HPV(−) samples (Fig 1D). Multidimensional scaling analysis revealed that the HPV-KRT subgroup was overall more similar to the HPV(−) samples (Fig 1B). We observed that HPV-KRT patients were more likely to be female, of type HPV16, and higher T stage (3 or 4) compared to HPV-IMU patients.

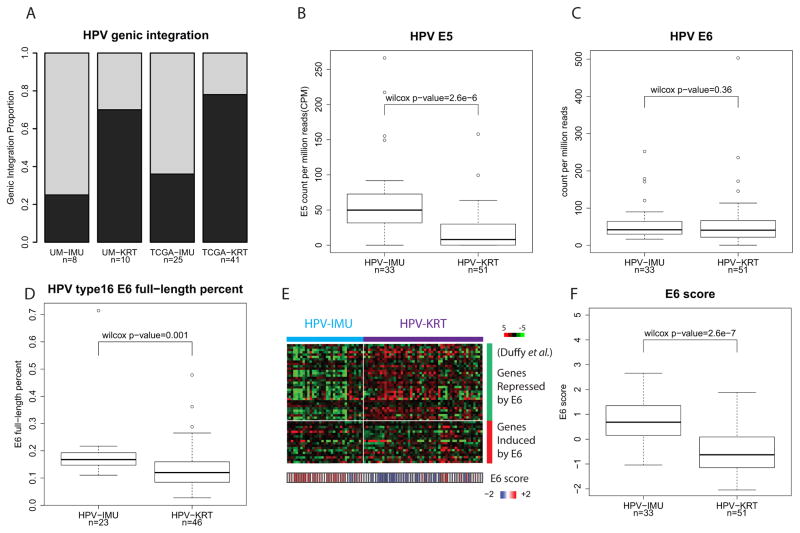

HPV(+) subgroups correlate with HPV integration, E2/E4/E5 expression levels, full-length E6 percent and E6 activity

We investigated HPV genic integration status and integration sites with VirusSeq (29) using RNA-seq data for the HPV(+) tumors. Nine of the 18 UM and 41 of the 66 TCGA HPV+ samples were found to contain at least one genic HPV integration site identified from virus-host fusion gene expression, hereafter denoted as genic-integration. Surprisingly, cluster HPV-KRT had more samples with genic-integration (7 out of 10; 70%) than cluster HPV-IMU (2 out of 8; 25%). The same difference was observed for TCGA data, where cluster HPV-KRT had 32 out of 41 (78%) with a genic-integration and HPV-IMU had 9 out of 25 (36%) (Fig 2A). This difference in genic-integration was significant between subgroups (combined p-value=0.0001; Fisher’s exact test).

Figure 2. HPV(+) subgroups correlate with several HPV characteristics.

(A) Barplot showing HPV-KRT tumors were more likely to have a detected genic-integration than HPV-IMU. (B) Boxplot of HPV E5 expression levels; HPV-KRT had lower E5 expression than HPV-IMU. (See Fig S2A,B for plots of E2 and E4.) (C) Boxplot of HPV E6 expression levels. (D) Boxplot of HPV E6 full-length percent for HPV type 16 samples. HPV-KRT had significantly lower E6 full-length percent than HPV-IMU. (E) Heatmap of the E6-regulated genes from Duffy et al. (38), showing genes repressed by E6 were lower expressed in HPV-IMU. E6 activity score is displayed at the bottom. (F) Boxplot of E6 activity score shows overall higher E6 activity in HPV-IMU. (See supplementary methods for how E6 score is calculated.)

We next tested whether any of the early HPV genes (E1, E2, E4, E5, E6, E7) were differentially expressed between the subgroups. Of these we found that E2, E4, and E5 had significantly lower expression in the HPV-KRT subgroup (E5 in Fig 2B, and E2 and E4 in Fig S3A,B), whereas E6 (fig 2C) and E7 (fig S3C) did not. HPV integration frequently associates with loss of E2, E4, and/or E5 (37). Since the HPV-KRT cluster had more genic integration events than HPV-IMU, this result is consistent with the difference in genic integration events. Upon closer examination, 4 of the 9 UM genic-integration-positive samples and 22 of the 41 TCGA samples displayed lost expression of E2/E4/E5 (Fig S3D).

It is known that E6 may be expressed in either of two main forms: a full-length E6 isoform and various spliced isoforms, together referred to as E6*, which have different functions not yet fully understood. We next asked whether the ratio of full-length E6 to total E6 expression correlates with subgroup membership (Fig S3E; see supplementary methods for details). Because the full-length E6 percentages differed significantly by HPV types (Fig S3F), we restricted our analysis to only the most prevalent HPV type, HPV16 (82% of all cases). HPV-KRT has significantly lower full-length E6 percent than HPV-IMU (Fig 2D) (Wilcox rank sum test p =0.001), suggesting that HPV-KRT expresses less full-length E6 transcript and more spliced form E6*.

Although the full-length E6 percent was different between subgroups, total E6 expression levels measured by RNA-seq were not (Fig 2C). Since the expression levels were quantified using RNA levels, they may not reflect the actual E6 protein activity levels in the cell. We took advantage of a published study by Duffy et al (38) of 51 genes (35 down and 16 up) regulated by E6, to calculate an E6 activity score for each tumor sample (see supplementary methods). Overall, the E6 score was significantly higher in HPV-IMU, indicating elevated E6 activity in HPV-IMU (Fig 2E,F; p=2.6e-7). In particular, the genes down-regulated by E6 in Duffy’s study were more repressed in HPV-IMU than HPV-KRT, whereas the up-regulated genes were induced to a lesser degree (Fig 2E).

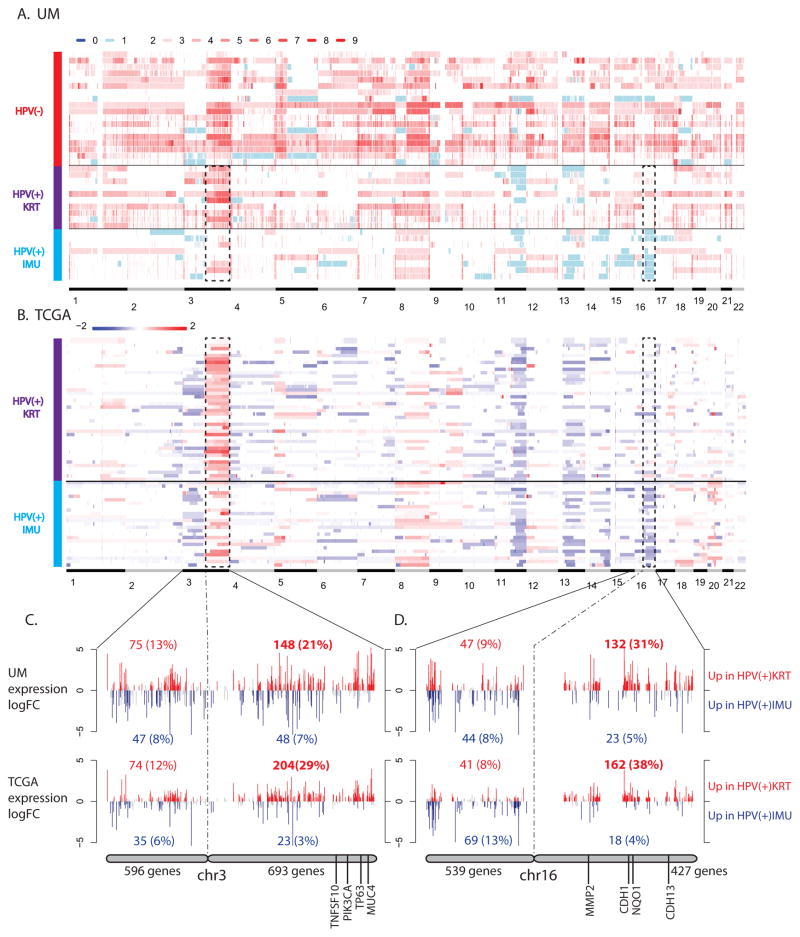

Correlation of subgroups with copy number alterations and PIK3CA mutation

Examining genomic properties of the two HPV(+) subgroups allowed us to further compare them with the HPV(−) HNC samples. Somatic copy numbers were obtained for all samples by analyzing SNP-array data from tumors and blood (see Methods). In our sample of 36 tumors, HPV(−) samples tended to harbor more copy number gains than HPV(+) samples (Fig 3A). In addition to the commonly observed copy number changes associated with HPV status (gain of 3q, 5p, 8q in HPV(−) tumors and loss of 11q and 13q in HPV(+) tumors) (27), we found substantial differences between the two HPV(+) subgroups. Overall, HPV-KRT tumors tended to have more amplifications than HPV-IMU. Particularly at the chromosomal arm level, HPV-KRT had more amplifications on all or a significant portion of chr3q than subgroup HPV-IMU (p=1.7e-5, Wilcoxon test). In addition, HPV-IMU had frequent copy number loss on chr16q, which was completely absent in HPV-KRT and HPV(−) samples. Differences in chr3q CNA gain and chr16q CNA loss were also observed in the respective HPV(+) TCGA subgroups (Fig 3B).

Figure 3. HPV(+) subgroups differ by copy number alterations.

(A,B) Heatmaps of somatic copy numbers for UM (A) and TCGA (B) samples. The dark dashed lines highlight the regions that differ by HPV(+) subgroup (chr3q gain and chr16q loss). The color legends show absolute copy number estimates for UM samples and log2 ratios of tumor to normal intensity for TCGA samples. (C,D) Plots showing the expression fold changes of genes on chr3q (C) and chr16q (D). There were more up-regulated genes (shown in red) than down-regulated genes (shown in blue) in HPV-KRT compared to HPV-IMU due to the CNA difference. Known differentially expressed cancer-related genes are noted for each. Significance was defined by q-value < 0.05.

To determine if the CNAs affected gene expression differences, we asked what percent of the genes on chr3q and chr16q were up versus down-regulated. Out of the 693 and 427 genes on chr3q and chr16q, 148 (21%) and 132 (31%) genes were significantly up-regulated in HPV-KRT compared to HPV-IMU, respectively; in contrast, a much smaller percent of genes were down-regulated (7% and 5%) (Fig 3C,D). This is quite distinct from the opposite arms of these chromosomes, 3p and 16p, where nearly equal percentages of genes were up and down regulated. The same trends were observed for TCGA data (Fig 3C,D). This suggests that the gain and loss of copy numbers in part drove the expression differences between the two subgroups. Using neoplasm-related gene annotations from Gene2MeSH (35), we found 33 oncology-related genes, including TNSF10, PIK3CA, TP63 and MUC4 on chr3q, and MMP2, CDH1, NQO1 and CDH13 on chr16q (Table S4). Nineteen of the 33 genes were also differentially expressed between the clusters.

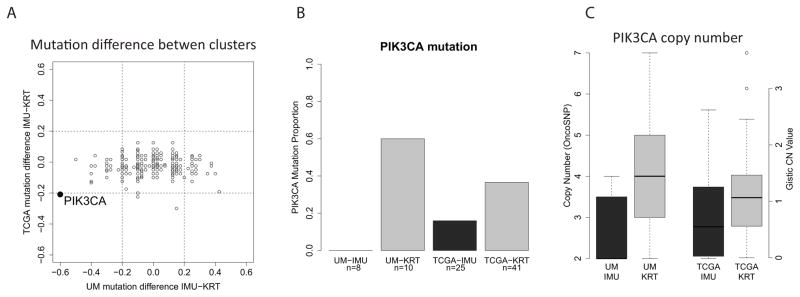

To investigate if there were any differences in gene mutation frequencies between the two subgroups, we analyzed expressed, non-synonymous mutations derived from the RNA-seq data. We also obtained TCGA gene-level somatic mutation data from Xena UCSC (32). None of the genes had a mutation percent difference between HPV-KRT and HPV-IMU greater than 20% in both cohorts, except for oncogene PIK3CA (Fig 4A). PIK3CA had a mutation in a striking 60% of samples from the HPV-KRT subgroup and 0% in HPV-IMU for the UM cohort. In TCGA, the difference was smaller (37% in HPV-KRT versus 16% in HPV-IMU), however still appreciable (Fig 4B). Five of the 6 UM PIK3CA mutations were known activating mutations (E545K, E545G and E542K), while the remaining mutation has unknown effect (E81K). Similarly, 17 out of the 19 mutations from TCGA were known activating mutations. Additionally, PIK3CA is located on chr3q, which was also found to have more amplifications in HPV-KRT. Not surprisingly, the copy numbers of PIK3CA were higher in HPV-KRT (Fig 4C). Together, these two results strongly suggest up-regulated PI3-kinase activity in the HPV-KRT tumors.

Figure 4. The HPV-KRT subgroup has more PIK3CA mutations and amplifications.

(A) Scatterplot showing the difference in mutation percent between the HPV(+) subgroups for each gene. PIK3CA was the only gene that had > 20% difference in both the UM and TCGA cohorts. The difference was calculated by subtracting the mutation percent in HPV-KRT from that of HPV-IMU. (B) Barplot showing the PIK3CA mutation percent for each subgroup and cohort (see supplementary methods for details). (C) Boxplot showing that in both cohorts, HPV-KRT had more PIK3CA copy number amplifications than HPV-IMU.

Characteristics associated with HPV(+) subgroups and patient survival

Summarizing and visualizing all of the above findings, we observe that although the clusters can be robustly separated by expression patterns, there remains substantial heterogeneity within each subgroup for each variable (Fig 5A). For example, we created an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) score for each tumor, which combines the expression levels of the epithelial and mesenchymal differentiation genes (see Methods). While the HPV-KRT subgroup clearly had lower EMT scores overall, there was substantial variation in scores, especially among the TCGA cohort. HPV-IMU has higher levels of immune response (represented in Fig 5A by an overall T cell score), frequent chr16q loss, less viral integration in an expressed genic region, more E2/E5, and higher BCL2 gene expression. Except for a stronger EMT signature, all other attributes for HPV-IMU were correlated with better prognosis in the literature (Fig 5B and Discussion). Because the elevated immune response in HPV-IMU could be an indication of higher infiltration of cytotoxic T-cells, we calculated a T-cell activation score for each tumor based on 196 genes from the GO term “T-cell activation” (see Methods). Using overall survival data from TCGA, we found that TCGA HPV(+) tumors with high T-cell activation scores had better overall survival than those with low T-cell activation scores (Fig 5C; p<0.05). Although we did not find a significant difference in overall survival between HPV-KRT and HPV-IMU with the same TCGA data, HPV-KRT tended to have worse overall survival than HPV-IMU (Fig 5D), consistent with the general predictions from literature (39–45) and the findings between HPV(+) subgroups in Keck et al (28). Tumor stage and site are two important covariates. To address a potential confounding effect, we performed a multivariate risk analysis using cluster membership, clinical stage (stage 1–3 vs stage 4) and site (oropharyngeal vs non-oropharyngeal). Compared to the univariate analysis we presented (Fig 5D), the trend of increasing risk in HPV-KRT remained, though the coefficient became smaller (0.608 to 0.369) with the p-value remaining insignificant. Lack of a significant difference could be due to the poor follow-up data available from TCGA, or due to truly similar overall survival between subgroups. In either case, the many above-described differences strongly suggest that different therapies may best benefit patients within each subgroup.

Figure 5. Summary of characteristics that differ by HPV(+) subgroup, and prognosis.

(A) Heatmap of variables that correlated with HPV(+) subgroup. The columns represent samples, sorted by cluster, cohort, viral integration and PIK3CA mutation. E5 expression values are the log10 transformed CPM values. (B) Observed features and associated publications suggesting better prognosis for HPV-IMU for all but EMT. (C) Overall survival for TCGA tumors with high and low T-cell activation scores. (D) Overall survival for HPV-KRT and HPV-IMU tumors from TCGA cohort. (C,D) P-values were calculated using a univariate Kaplan-Meier log rank test.

Discussion

Head and neck squamous cell carcinomas represent a heterogeneous disease that consists of two molecular and clinically distinct entities distinguished by HPV infection. Due to a lack of HPV information and/or a small number of HPV(+) cases in most previous studies, attempts to identify tumor subtypes in HNCs have often neglected HPV as an important variable. In one study, Pyeon et al found two distinct subgroups of HPV(+) cancers, which were differentiated by a few key genes (24). Keck et al also independently identified two HPV(+) subtypes (28), and characterized differences in morphology (differentiation and proliferation), expression (mesenchymal and immune response) and copy number of a few key neoplasm genes (PIK3CA, TP63, SOX2) between subtypes. However, they were unable to comprehensively describe molecular differences between the HPV(+) subtypes. Specifically, it remained unclear how these subtypes correlated with HPV characteristics, and the likely cause for their distinct behaviors.

Using unsupervised clustering analysis, we independently identified two robust HPV(+) subgroups with our cohort that persisted when we applied the same algorithm to the TCGA cohort. Although our clusters are constructed on RNA-seq data as opposed to microarrays, they share similarities with the two HPV(+) clusters found in Keck et al. (28). We observed similar differences between the two clusters in immune response, mesenchymal differentiation and keratinization, and copy number changes in PIK3CA and TP63. However, whereas we found that the two HPV(+) groups clustered separately from the HPV(−) tumors (with one exception), Keck et al found a significant number of HPV(−) tumors co-clustered in each of their two HPV(+) subgroups. The one HPV(−) sample that clustered with HPV-IMU in our cohort had an induced immune response expression profile similar to that of the HPV-IMU subgroup, and it was classified as laryngeal, possibly explaining its outlier status. In addition to providing an independent source validating the existence of two HPV(+) subtypes, we greatly expanded the depth of characterization by comprehensively profiling the expressed mutations, whole-genome CNAs and exploring HPV characteristics. Most importantly, our findings highlight two oncogenic paths in HPV(+) tumors that are likely driven by differences in HPV characteristics, chromosome-arm level CNAs, and PI3K pathway activity. Interestingly, the subtype membership also seemed to correlate with other demographic variables: the KRT group tended to have more females, more high-stage tumors and more non-oropharynx tumors. The gender ratio was similar between subtypes in Keck et al (28), and the p-value was very close to 0.05 in our analysis (Table 1), suggesting that this may be a spurious result and will need validation with larger cohorts.

The most significant difference in expression between the HPV(+) clusters is the up-regulation of mesenchymal and immune-response genes in the HPV-IMU group, and keratinization and oxidation-reduction process in HPV-KRT. In fact, all of these pathways can be explained by the biology of HPV carcinogenesis. The HPV E6 oncoprotein is reported to down-regulate a large number of genes involved in keratinocyte differentiation, and up-regulate genes normally expressed in mesenchymal lineages (38). In addition, HPV type16 spliced variant E6* induces oxidative stress (16). Our analysis revealed that the HPV-IMU group had higher E6 activity whereas HPV-KRT had higher levels of the spliced forms of E6, E6*, which is concordant with the repressed keratinization and induced mesenchymal differential pathways in HPV-IMU and higher oxidation-reduction response in HPV-KRT. The HPV-KRT group was also more likely to have a detected HPV integration event, which may drive the expression of more E6* and less full-length E6.

The higher immune response in HPV-IMU may be particularly relevant, as it was shown that HPV(+) HNCs have a different immune profile than their HPV(−) counterparts, featuring higher numbers of infiltrating CD8+ T lymphocytes, myeloid dendritic cell and proinflammatory chemokines (46). Together, these are hypothesized to promote better response to treatment in HPV(+) patients (46). In our study, we showed that stronger immune response could indeed predict better overall survival (Fig 5C). We hypothesize that when HPV shifts from the initial episomal form to an integrated transcribed form, the inflammatory/immune response towards HPV concurrently weakens. That may explain why HPV-IMU, having fewer HPV-integration events, have a stronger immune response. The stronger inflammatory/immune response in the HPV-IMU group may partially explain why HPV(+) HNCs overall have better prognosis.

Another key finding of our study is that more chr3q amplifications were observed in HPV-KRT, whereas frequent chr16q deletions were found in HPV-IMU. These two signature copy number changes were evident in the independent UM and TCGA cohorts, validating these findings. However, the functional significance behind the associations of the copy number signatures with subgroups is unclear. One possible explanation could be that the change in copy number of a few key genes on chr3q and chr16q favors the survival/growth of tumor cells in each respective subgroup, thus they were each positively selected in the tumor evolution of each subtype. We queried a tumor associated gene (TAG) database (47) for the percent of oncogenes and tumor repressor genes (TSG) on chr3q and chr16q, and interestingly, the majority of TAGs on chr3q are oncogenes (14 oncogenes, 4 TSGs, and 9 unknown) whereas most TAGs on chr16q are TSGs (12 TSGs, 1 oncogene, and 2 unknown). This preliminary result suggests that the amplification of chr3q and deletion of chr16q are both more likely to promote tumor growth. Examining the genes more closely, we found that on chr3q, several key cancer genes stood out as having anti-apoptotic function, such as PIK3CA, TP63, MUC4, which may promote cancer cell survival for HPV-KRT as a result of chr3q amplification. Particularly ΔNp63α (an isoform of p63) is dominantly over expressed in HNC and plays a pivotal anti-differentiation and anti-apoptosis role in the formation of HNC (48). On chr16q, CDH1, CDH13, and BCAR1 were associated with cell adhesion, thus the attenuation of their expression by copy number loss in HPV-IMU likely strengthens EMT properties in this subtype.

When we investigated the mutation difference between the clusters, PIK3CA was found to be the top hit. PI3-kinase signaling pathway has previously been implicated in tumorigenesis and PIK3CA activating mutations have been found in various cancer types (49). We discovered that the HPV-KRT subgroup not only has more PIK3CA activating mutations, but also more copy number gains of PIK3CA. This suggests elevated PIK3CA activity is important especially in the HPV-KRT group, and may further implicate a difference in tumorigenesis paths between the two subtypes.

One limitation of our study is the lack of patient survival data. UM HPV(+) tumors were collected between 2011–2013, and due to high overall survival in this group, we are not yet able to perform meaningful risk analysis on these patients. The TCGA cohort has 66 HPV(+) samples, however most of the patients were lost to follow-up after 12 months, therefore effectively reducing the sample size and conferring the analysis a much lower power, especially in analyses including covariate adjustment. Nevertheless, HPV-KRT patients are conceived to have worse outcome based on several lines of evidence. First, HPV-KRT’s expression profiles (Fig 1B) and copy number profiles, particularly gain on chr3q (Fig 3A), are more similar to those of HPV(−) patients, who are known to have worse treatment response and survival. HPV-IMU has more frequent chr16q loss, which was reported to correlate with better survival for patients with oropharyngeal SCCs (39). In addition, HPV-KRT tumors are more likely to have expressed genic virus integration events, which may be indicative of or contribute to a higher level of genomic instability. In cervical cancer, it was found that patients who only had integrated HPV expression had a trend towards worse disease free survival compared to patients with both integrated and episomal HPV forms (40). Studies on HNCs showed worse recurrence-free survival for HPV(+) tumors with low levels of E2 (41) and E5 (42), markers for integrated HPV. HPV-IMU has much higher levels of BCL2 expression than HPV-KRT, which has been reported to correlate with more favorable outcome in HNCs (43,44). HPV-IMU also has higher immune response, which was shown to correlate with better survival in HPV(+) oropharyngeal cancer (45). Altogether, this network of correlated events and pathways implies that the HPV-IMU and HPV-KRT subtypes proceed through carcinogenesis using different driving forces, and are thus likely to benefit from different treatment strategies. While patients falling in the HPV-IMU subgroup may benefit more from immunotherapies and treatment targeting EMT, HPV-KRT may benefit from strategies to induce tissue-based inflammation (50). Furthermore, our results strongly suggest that most of these differences are driven by characteristics of the HPV infection itself.

In conclusion, we identified two subtypes of HNC HPV(+) tumors based initially on expression patterns from RNA-seq data, but found to strongly correlate with a substantial number of important molecular markers, including viral characteristics, CNAs, and oncogenic PIK3CA mutations. This study takes a significant step towards decoding the molecular heterogeneity among HPV-associated HNCs. Our work has important translational implications that could guide biomarker development and precision medicine for HPV(+) HNC patients.

Supplementary Material

Statement of translational relevance.

Despite significant clinical implications, the molecular characteristics of human papillomavirus associated (HPV(+)) head and neck cancers (HNC) are less well characterized than HPV-negative (HPV(−)) tumors. We deeply characterized the genomic and transcriptomic signatures of HPV(+) and HPV(−) HNCs to determine if there are molecular subgroups that may correspond to clinical outcomes. We identified two robust HPV(+) subtypes using gene expression-based clustering. One subtype (HPV-KRT) has more keratinization, viral integration events, spliced E6*, chr3q amplifications and PIK3CA mutations, whereas the other subtype (HPV-IMU) has more mesenchymal differentiation, full-length E6 activity and chr16q deletions, and stronger immune response. Literature concerning these features suggest a worse outcome for HPV-KRT; the expected trend was observed in The Cancer Genome Atlas survival analysis. Our study provides insight into the key genetic events that likely drive two different paths of oncogenesis in HPV(+) HNCs, which will be important for guiding personalized treatment plans for HPV(+) patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was funded by National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute [R01CA158286], the University of Michigan Specialized Programs of Research Excellence (SPORE) Grant [P50CA097248], as well as by the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) training grant [T32 HG00040].

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare there are no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin H-R, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893–917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Hernandez BY, Xiao W, Kim E, et al. Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4294–301. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.4596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kreimer AR, Clifford GM, Boyle P, Franceschi S. Human papillomavirus types in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas worldwide: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:467–75. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walline HM, Komarck C, McHugh JB, Byrd SA, Spector ME, Hauff SJ, et al. High-risk human papillomavirus detection in oropharyngeal, nasopharyngeal, and oral cavity cancers: comparison of multiple methods. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg American Medical Association. 2013;139:1320–7. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2013.5460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, Weber R, Rosenthal DI, Nguyen-Tân PF, et al. Human Papillomavirus and Survival of Patients with Oropharyngeal Cancer. N Engl J Med New England Journal of Medicine ({NEJM}/{MMS}) 2010;363:24–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chung CH, Zhang Q, Kong CS, Harris J, Fertig EJ, Harari PM, et al. p16 Protein Expression and Human Papillomavirus Status As Prognostic Biomarkers of Nonoropharyngeal Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3930–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.5228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maxwell JH, Kumar B, Feng FY, Worden FP, Lee JS, Eisbruch A, et al. Tobacco use in human papillomavirus-positive advanced oropharynx cancer patients related to increased risk of distant metastases and tumor recurrence. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1226–35. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dayyani F, Etzel CJ, Liu M, Ho C-H, Lippman SM, Tsao AS. Meta-analysis of the impact of human papillomavirus (HPV) on cancer risk and overall survival in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC) Head Neck Oncol England. 2010;2:15. doi: 10.1186/1758-3284-2-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arthur AE, Duffy SA, Sanchez GI, Gruber SB, Terrell JE, Hebert JR, et al. Higher micronutrient intake is associated with human papillomavirus-positive head and neck cancer: a case-only analysis. Nutr Cancer. 2011;63:734–42. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2011.570894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Syrjanen S. The role of human papillomavirus infection in head and neck cancers. Ann Oncol England. 2010;21:vii243–5. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayes DN, Van Waes C, Seiwert TY. Genetic Landscape of Human Papillomavirus-Associated Head and Neck Cancer and Comparison to Tobacco-Related Tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3227–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moody Ca, Laimins La. Nat Rev Cancer. Vol. 10. Nature Publishing Group; 2010. Human papillomavirus oncoproteins: pathways to transformation; pp. 550–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tindle RW. Immune evasion in human papillomavirus-associated cervical cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:59–64. doi: 10.1038/nrc700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whiteside MA, Siegel EM, Unger ER. Human papillomavirus and molecular considerations for cancer risk. Cancer. 2008;113:2981–94. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duensing S, Münger K. The human papillomavirus type 16 E6 and E7 oncoproteins independently induce numerical and structural chromosome instability. Cancer Res. 2002;62:7075–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams VM, Filippova M, Filippov V, Payne KJ, Duerksen-Hughes P. Human Papillomavirus Type 16 E6* Induces Oxidative Stress and DNA Damage. J Virol. 2014;88:6751–61. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03355-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pim D, Banks L. HPV-18 E6*I protein modulates the E6-directed degradation of p53 by binding to full-length HPV-18 E6. Oncogene. 1999;18:7403–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tungteakkhun SS, Filippova M, Fodor N, Duerksen-Hughes PJ. The Full-Length Isoform of Human Papillomavirus 16 E6 and Its Splice Variant E6* Bind to Different Sites on the Procaspase 8 Death Effector Domain. J Virol. 2009;84:1453–63. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01331-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hong A, Zhang X, Jones D, Zhang M, Lee CS, Lyons JG, et al. E6 viral protein ratio correlates with outcomes in human papillomavirus related oropharyngeal cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2015:1–7. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2015.1108489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akagi K, Li J, Broutian TR, Padilla-Nash H, Xiao W, Jiang B, et al. Genome-wide analysis of HPV integration in human cancers reveals recurrent, focal genomic instability. Genome Res. 2014;24:185–99. doi: 10.1101/gr.164806.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parfenov M, Sekhar C, Gehlenborg N, Freeman SS, Danilova L, Pedamallu CS, et al. Characterization of HPV and host genome interactions in primary head and neck cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111:15544–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1416074111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeon S, Lambert PF. Integration of human papillomavirus type 16 DNA into the human genome leads to increased stability of E6 and E7 mRNAs: implications for cervical carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:1654–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wichmann G, Rosolowski M, Krohn K, Kreuz M, Boehm A, Reiche A, et al. The role of HPV RNA transcription, immune response-related gene expression and disruptive TP53 mutations in diagnostic and prognostic profiling of head and neck cancer. Int J Cancer. 2015;00 doi: 10.1002/ijc.29649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pyeon D, Newton Ma, Lambert PF, Den Boon Ja, Sengupta S, Marsit CJ, et al. Fundamental differences in cell cycle deregulation in human papillomavirus-positive and human papillomavirus-negative head/neck and cervical cancers. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4605–19. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slebos RJC. Gene Expression Differences Associated with Human Papillomavirus Status in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res United States. 2006;12:701–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chung CH, Parker JS, Karaca G, Wu J, Funkhouser WK, Moore D, et al. Molecular classification of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas using patterns of gene expression. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:489–500. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lawrence MS, Sougnez C, Lichtenstein L, Cibulskis K, Lander E, Gabriel SB, et al. Comprehensive genomic characterization of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Nature. 2015;517:576–82. doi: 10.1038/nature14129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keck MK, Zuo Z, Khattri A, Stricker TP, Brown CD, Imanguli M, et al. Integrative Analysis of Head and Neck Cancer Identifies Two Biologically Distinct HPV and Three Non-HPV Subtypes. Clin Cancer Res United States. 2014;21:870–81. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen Y, Yao H, Thompson EJ, Tannir NM, Weinstein JN, Su X. VirusSeq: software to identify viruses and their integration sites using next-generation sequencing of human cancer tissue. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:266–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DePristo MA, Banks E, Poplin R, Garimella KV, Maguire JR, Hartl C, et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat Genet. 2011;43:491–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilks C, Cline MS, Weiler E, Diehkans M, Craft B, Martin C, et al. The Cancer Genomics Hub (CGHub): overcoming cancer through the power of torrential data. Database. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1093/database/bau093. bau093–bau093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldman M, Craft B, Swatloski T, Cline M, Morozova O, Diekhans M, et al. The UCSC Cancer Genomics Browser: update 2015. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D812–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Monti S, Tamayo P, Mesirov J, Golub T. Consensus clustering: A resampling based method for class discovery and visualization of gene expression microarray data. Mach Learn. 2003;52:91–118. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yau C, Mouradov D, Jorissen RN, Colella S, Mirza G, Steers G, et al. A statistical approach for detecting genomic aberrations in heterogeneous tumor samples from single nucleotide polymorphism genotyping data. Genome Biol BioMed Central Ltd. 2010;11:R92. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-9-r92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ade AS, Wright ZC, States D. Gene2MeSH [Internet] 2007 Available from: http://gene2mesh.ncibi.org.

- 36.Sartor MA, Leikauf GD, Medvedovic M. LRpath: a logistic regression approach for identifying enriched biological groups in gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:211–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.zur Hausen H. Papillomaviruses and cancer: from basic studies to clinical application. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:342–50. doi: 10.1038/nrc798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duffy CL, Phillips SL, Klingelhutz AJ. Microarray analysis identifies differentiation-associated genes regulated by human papillomavirus type 16 E6. Virology. 2003;314:196–205. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00390-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klussmann JP, Mooren JJ, Lehnen M, Claessen SMH, Stenner M, Huebbers CU, et al. Genetic signatures of HPV-related and unrelated oropharyngeal carcinoma and their prognostic implications. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:1779–86. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shin H-J, Joo J, Yoon JH, Yoo CW, Kim J-Y. Physical Status of Human Papillomavirus Integration in Cervical Cancer Is Associated with Treatment Outcome of the Patients Treated with Radiotherapy. In: Lo AWI, editor. PLoS One. Vol. 9. 2014. p. e78995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramqvist T, Mints M, Tertipis N, Näsman A, Romanitan M, Dalianis T. Studies on human papillomavirus (HPV) 16 E2, E5 and E7 mRNA in HPV-positive tonsillar and base of tongue cancer in relation to clinical outcome and immunological parameters. Oral Oncol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Um SH, Mundi N, Yoo J, Palma Da, Fung K, MacNeil D, et al. Variable expression of the forgotten oncogene E5 in HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer. J Clin Virol Netherlands. 2014;61:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2014.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilson GD, Saunders M, Dische S, Richman P, Daley F, Bentzen SM. bcl-2 expression in head and neck cancer: an enigmatic prognostic marker. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2001;49:435–41. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)01498-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Camisasca DR, Honorato J, Bernardo V, da Silva LE, da Fonseca EC, de Faria PAS, et al. Expression of Bcl-2 family proteins and associated clinicopathologic factors predict survival outcome in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:225–33. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.King EV, Ottensmeier CH, Thomas GJ. The immune response in HPV(+) oropharyngeal cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2014;3:e27254. doi: 10.4161/onci.27254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Partlová S, Bouček J, Kloudová K, Lukešová E, Zábrodský M, Grega M, et al. Distinct patterns of intratumoral immune cell infiltrates in patients with HPV-associated compared to non-virally induced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncoimmunology. 2015;4:e965570. doi: 10.4161/21624011.2014.965570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen J-S, Hung W-S, Chan H-H, Tsai S-J, Sun HS. In silico identification of oncogenic potential of fyn-related kinase in hepatocellular carcinoma. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:420–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rothenberg SM, Ellisen LW. The molecular pathogenesis of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Invest American Society for Clinical Investigation. 2012;122:1951–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI59889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yuan TL, Cantley LC. Oncogene. Vol. 27. Macmillan Publishers Limited; 2008. PI3K pathway alterations in cancer: variations on a theme; pp. 5497–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gajewski TF, Schreiber H, Fu Y-X. Innate and adaptive immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:1014–22. doi: 10.1038/ni.2703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.