Abstract

Estradiol (E2) perfusion rapidly increases the strength of fast excitatory transmission and facilitates long-term potentiation in the hippocampus, two effects likely related to its memory-enhancing properties. Past studies showed that E2's facilitation of transmission involves activation of RhoA signaling leading to actin polymerization in dendritic spines. Here we report that brief exposure of adult male hippocampal slices to 1 nM E2 increases the percentage of postsynaptic densities associated with high levels of immunoreactivity for activated forms of the BDNF receptor TrkB and β1-integrins, two synaptic receptors that engage actin regulatory RhoA signaling. The effects of E2 on baseline synaptic responses were unaffected by pretreatment with the TrkB-Fc scavenger for extracellular BDNF or TrkB antagonism, but were eliminated by neutralizing antisera for β1-integrins. E2 effects on synaptic responses were also absent in conditional β1-integrin knockouts, and with inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases, extracellular enzymes that generate integrin ligands. We propose that E2, acting through estrogen receptor-β, transactivates synaptic TrkB and β1-integrin, and via mechanisms dependent on integrin activation and signaling, reversibly reorganizes the spine cytoskeleton and thereby enhances synaptic responses in adult hippocampus.

Introduction

Acute treatments with estradiol (E2), the most potent and prevalent estrogen, improve learning in male and female rodents, while reduced levels impair retention in a variety of behavioral paradigms in female rodents (Luine and Frankfurt, 2012). Understanding processes responsible for these effects would be a significant step towards the development of cellular explanations for a broad range of memory-related phenomena. Neurobiological studies have identified two effects of E2 that constitute plausible explanations for its rapid actions on memory and cognition: (1) brief exposures rapidly enhance transmission within cortical networks, and (2) E2 lowers the threshold for inducing long-term potentiation (LTP), a form of plasticity implicated in memory encoding (Bi et al, 2000; Foy et al, 1999; Kramar et al, 2009). How the steroid produces these actions is not yet understood. One possibility is suggested by recent work showing that E2 engages actin-regulatory signaling involved in the production of LTP (Kramar et al, 2009; Yuen et al, 2011) and may thereby produce a mild and reversible potentiation of excitatory synaptic responses. Specifically, cytoskeletal effects of E2 are associated with stimulation of RhoA GTPase signaling leading to phosphorylation (inactivation) of the actin-depolymerizing protein cofilin. Moreover, E2-induced increases in the strength of synaptic transmission are accompanied by actin polymerization in dendritic spines and both effects are blocked by latrunculin (Kramar et al, 2009), which disrupts actin filament assembly.

The present studies further investigated mechanisms through which E2 influences the spine cytoskeleton. It has been proposed (Spencer et al, 2008) that E2 transactivates synaptic TrkB receptors for BDNF. This possibility is of considerable interest here because BDNF engages RhoA-to-cofilin signaling leading to LTP-related actin polymerization (Panja and Bramham, 2014; Rex et al, 2009). We first determined if E2 increases TrkB phosphorylation at excitatory synapses in adult rat hippocampus and then asked if scavenging extracellular BDNF blunts the effects of E2 on transmission.

Integrins constitute a second group of receptors that have an essential role in structural changes required for shifting synapses into the potentiated state. Integrins are αβ heterodimeric transmembrane proteins that mediate cell–extracellular matrix adhesion and exert a strong regulatory influence on the actin cytoskeleton (DeMali et al, 2003). β1 Family integrins are localized to excitatory synapse postsynaptic densities (PSDs) (Mortillo et al, 2012) and critical for activity-induced synaptic plasticity and the associated actin remodeling (Chan et al, 2006; Kramar et al, 2006; Nagy et al, 2006; Wang et al, 2008). Moreover, integrins influence signaling by neighboring receptors including those for estrogen and growth factors (Meng et al, 2011; Miranti and Brugge, 2002; Munger and Sheppard, 2011). Accordingly, we tested if in acute hippocampal slices E2 perfusion activates synaptic β1-integrins and if neutralizing β1 function reduces the steroid's effect on transmission.

Materials and methods

Hippocampal Slice Electrophysiology

Acute hippocampal slices were prepared from young adult male and female rats (Sprague–Dawley; 40–50 days old) and mice (C57BL6/J; 2.5–3 months), collected into chilled high magnesium artificial cerebral spinal fluid (ACSF) containing (in mM): 124 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1.25 KH2PO4, 5.0 MgSO4, 26 NaHCO3, and 10 dextrose and then transferred to an interface recording chamber at 31±1 °C with 60–70 ml/h infusion of oxygenated ACSF containing (in mM): 124 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1.25 KH2PO4, 1.5 MgSO4, 26 NaHCO3, 2.5 CaCl2, and 10 dextrose (Trieu et al, 2015). Experiments began 1.5–2 h later. To study responses of Schaffer-commissural (S-C) innervation of field CA1b stratum radiatum (SR), stimulating electrodes were placed in CA1a and CA1c SR and a glass recording electrode (2 M NaCl filled, 2–3 MΩ) was positioned in CA1b SR. Stimulation intensity was set to elicit field EPSPs (fEPSPs) that were 50–60% of the maximum spike-free response. fEPSP initial slopes and peak amplitudes were measured using NACGather 2.0 (Theta Burst Corp., Irvine, CA, USA). Baseline stimulation was applied as single pulses at 3/min. LTP was induced with one train of theta burst stimulation (TBS: 10 bursts of 4 pulses at 100 Hz, 200 ms between bursts; at baseline stimulation intensity). For quantitative analyses, the ‘N' values reflect the number of slices per group.

Drug Application

Antagonists were introduced to the ACSF perfusion line using a syringe pump; E2 was introduced via the ACSF perfusate at 1.17 baseline rate. Vehicle controls and antagonists were run in parallel using slices from the same animal. Drug, neutralizing antisera, and TrkB-Fc experiments used concentrations selected from the literature and our prior work. Agents used included estrogen receptor-α (ERα) antagonist MPP (1, 3-Bis (4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-methyl-5-[4-(2-piperidinylethoxy) phenol]-1H-pyrazole dihydrochloride), ERβ antagonist PHTPP (4-[2-phenyl-5,7-bis(trifluoromethyl)pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-3-yl]phenoland), β-E2 ((17β)-estra-1,3,5(10)-triene-3,17-diol), GM6001 and batimastat (Tocris, Bristol, UK), and G-15 (Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI); these compounds were prepared in 100% dimethylsulfoxide and diluted to a final concentration in ACSF. TrkB-Fc Chimera Protein (688-TK; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), ANA-12 (Tocris), and neutralizing anti-β1-integrin (MAB1987Z; Millipore, Billerica, MA) were diluted in ACSF to 2 μg/ml, 500 nM, and 0.2 mg/ml, respectively. The latter two reagents were applied locally by pressure ejection (Picospritzer; General Valve, Fairfield, NJ) (Kramar et al, 2006).

Immunostaining and Fluorescence Deconvolution Tomography

Hippocampal slices were processed for dual immunofluorescence and fluorescence deconvolution tomography as described (Seese et al, 2012, 2013). Primary antisera cocktails included rabbit anti-ERα (1:700, sc-543), mouse anti-ERβ (1:700, sc-390243) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), rabbit anti-pTrkB Tyr515 (1:500, NB100-92656; Novus Biochem, Littleton, CO) (Simmons et al, 2013) and anti-activated β1-integrin (1:400, MAB2259Z, Millipore, Middleton MA) (Ni et al, 1998) in combination with anti-PSD95 (1:1000, MA1-045 (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) or ab12093 (Abcam, Cambridge UK)). Secondary antisera included AlexaFluor 594 anti-rabbit IgG and AlexaFluor 488 anti-mouse IgG (1:1000; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Epifluorescence image z-stacks were collected at × 63 in 200 nm steps through 2 μm from CA1b SR (4–5 stacks per slice). Images were processed through restorative deconvolution (99% confidence, Volocity 4.0; Perkin-Elmer) and individual z-stacks were used to construct a three-dimensional (3D) montage of each sample field (136 × 105 × 2 μm3); elements meeting size constraints of synapses, and detected across multiple intensity thresholds, were quantified using automated systems (Rex et al, 2009; Seese et al, 2013). This resulted in the analysis of ~30 000 PSDs per sample field and >100 000 PSDs per slice. Elements were considered double labeled if there was overlap in the two fluorophores as assessed in 3D. The density of a particular immunolabel colocalized with PSD95 was measured for each synapse and expressed as a percent of all double-labeled PSDs for construction of intensity frequency distributions.

β1-Integrin Knockouts

Conditional β1-integrin knockouts (cKOs) were created by crossing mice with floxed β1-integrin gene exon 3, with mice expressing Cre-recombinase under the CaMKII promoter (Chan et al, 2006; Mortillo et al, 2012). In progeny, Cre expression in excitatory hippocampal and cortical neurons (Tsien et al, 1996) leads to excision of β1 exon 3, and disrupted β1 protein expression, from ~3 weeks of age; experiments were conducted on 2–3-month-old mice. The genetic manipulation was verified by PCR of genomic DNA and by rtPCR of mRNA, isolated from hippocampus, using primers spanning β1 exon 3: 5′-GAATTTGCAACTGGTTTCCTGG-3′ and 5′-ACAACAGCTGCTTCTAAAATTGA-3′. Mice were verified to contain Lox-p sites and Cre-recombinase expression by PCR of DNA from tail snips.

Statistics

Results are presented as means±SEM. Statistical significance (p<0.05) was evaluated using two-tailed Student's t-test, and one- and two-way analysis of variance (GraphPad Prism, San Diego, CA). In graphs asterisks denote the level of significance (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001).

Results

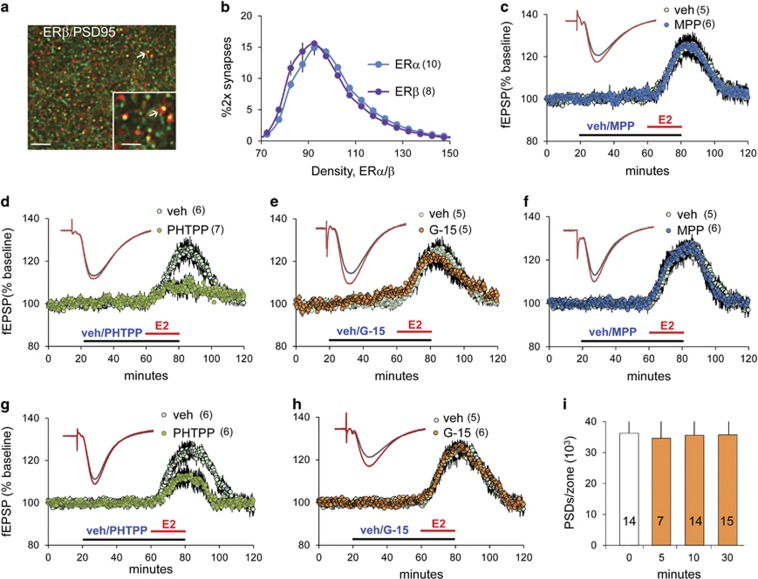

Synaptic Localization of ERα and ERβ

Both ERα and ERβ have been localized to dendritic spines (Hara et al, 2015). We used dual fluorescence deconvolution tomography (FDT) (Figure 1a) (Seese et al, 2012, 2013) to compare the distribution and density of these receptors at excitatory synapses in CA1 SR in hippocampal slices from young adult male rats. While absolute values for labeling intensity cannot be compared for two antibodies, intensity–frequency–distribution curves (% double-labeled synapse-sized elements across a series of immunolabeling-density bins) provide a relative measure (normalized per slice) for comparison of ERα and ERβ. The incidence of PSD localization and intensity–frequency–distribution curves were comparable for the two ERs (p>0.70; Figure 1b), suggesting that there were no differences in their relative abundance at field CA1 SR synapses.

Figure 1.

Estradiol (E2) enhances synaptic transmission through estrogen receptor-β (ERβ) in rat slices. (a) Deconvolved image shows postsynaptic density 95 (PSD95) (green) and ERβ (red) immunostaining; double-labeled elements appear yellow (arrows; bar: 10 μm; inset bar:1 μm). (b) Immunolabeling intensity frequency distributions for ERα and ERβ colocalized with PSD95 (% of all double-labeled (2 ×) PSD95+ elements shown; mean±SEM values; F(19,320)=11.29, p>0.70, two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). (c–e) E2 (1 nM) applied to male slices for 20 min rapidly increased excitatory postsynaptic potential (fEPSP) slope: this response was not affected by pretreatment with (c) ERα antagonist MPP (1, 3-bis (4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-methyl-5-[4-(2-piperidinylethoxy) phenol]-1H-pyrazole dihydrochloride) (3 μM) or (e) GPER1 antagonist G-15 (100 nM) but was blocked by (d) ERβ antagonist PHTPP (3 μM; t(10)=3.658, p=0.005 for E2 vs E2+PHTPP; two-tailed t-test). (f–h) E2 (1 nM) applied to female slices for 20 min enhanced fEPSPs as in males: antagonists of ERα (f) or GPER1 (h), perfused at the same concentrations used in the male studies, had no effect on E2's response facilitation. (g) However, ERβ antagonist PHTPP markedly reduced effects of E2 (t(10)=2.69, p=0.027; two-tailed t-test). (i) Numbers of PSD95+ synapses do not differ with time after E2 perfusion onset in male slices (F(3,46)=0.268, p=0.848, one-way ANOVA). Numbers within parentheses and on bars denote the number of slices per group.

Exogenous E2 Enhances Transmission via ERβ

Next, we tested which ER mediates the synaptic response facilitation produced by exogenous E2. E2 (1 nM) was perfused for 20 min into hippocampal slices from young adult male rats with low-frequency (3/min) stimulation applied to the S-C projections; fEPSPs were collected from CA1b SR. Response size increased within 2–5 min of E2 arrival in the chamber and shortly thereafter reached a plateau at 15–30% above baseline (Figure 1c). Past work showed that E2's effects on fEPSPs in field CA1 are not accompanied by changes in S–C paired-pulse facilitation or NMDA receptor currents, measures that would reflect changes in neurotransmitter release (Kramar et al, 2009). Moreover, feedforward inhibition mediated by GABA-A or GABA-B receptors was not detectably affected by 20 min E2 perfusion (Kramar et al, 2009).

The response enhancement produced by E2 was not affected by ERα antagonist MPP (3 μM; E2: 23.97±9.47%, E2+MPP: 25.12±11.13%) but was effectively eliminated by ERβ blocker PHTPP (3 μM; E2: 22.25±7.47%, E2+PHTPP: 6.25±7.16%, p=0.005; E2+PHTPP vs baseline, p=0.07)(Figures 1c and d). These results accord with evidence that ERβ agonist WAY-200070 replicates the effects of E2 on transmission, whereas ERα agonist PTT does not (Kramar et al, 2009). The G-protein-coupled ER-1 (GPER1) reportedly contributes importantly to exogenous E2 effects on excitatory transmission in female rodents (Kumar et al, 2015; Oberlander and Woolley, 2016). However, in slices from male rats GPER1 antagonist G-15 (100 nM) did not attenuate E2's effects on S-C fEPSPs (E2: 24.34±6.19%, E2+G-15: 22.60±2.57% Figure 1e). These results indicate that in males ERβ mediates effects of applied E2 on S-C response facilitation.

Similar results were obtained using slices from female rats: E2 increased fEPSPs in vehicle-treated slices with the same magnitude and time course as in male slices, and these effects did not differ across estrus cycle stages (diestrus: 44% of cases; estrus: 26% proestrus: 26%). Pretreatment with ERβ blocker PHTTP markedly reduced but, in contrast to effects in males, did not eliminate response enhancement by E2 (E2: 25.1±10.55%, E2+PHTPP: 13.37±8.52% p=0.027; E2+PHTPP vs baseline, p=0.004; Figure 1g), whereas ERα and GPER1 antagonists had no effect (E2: 24.95±8.67% vs E2+MPP: 26.27±5.24% E2: 26.54±11.09% vs E2+G-15: 26.34±5.20% Figures 1f and h).

Many studies have shown that E2 increases the number of spines (Hara et al, 2015; Luine and Frankfurt, 2012; Mukai et al, 2007) and spine synapses (Fester and Rune, 2015; Leranth et al, 2000), but whether this effect occurs quickly enough to contribute to the rapid facilitation of synaptic responses is unclear. Accordingly, we used FDT to count the number of PSD95-immunopositive (+) synapses in CA1 SR of slices harvested 5–30 min after E2 perfusion onset: the steroid did not increase the number of immunolabeled PSDs through 30 min (Figure 1i).

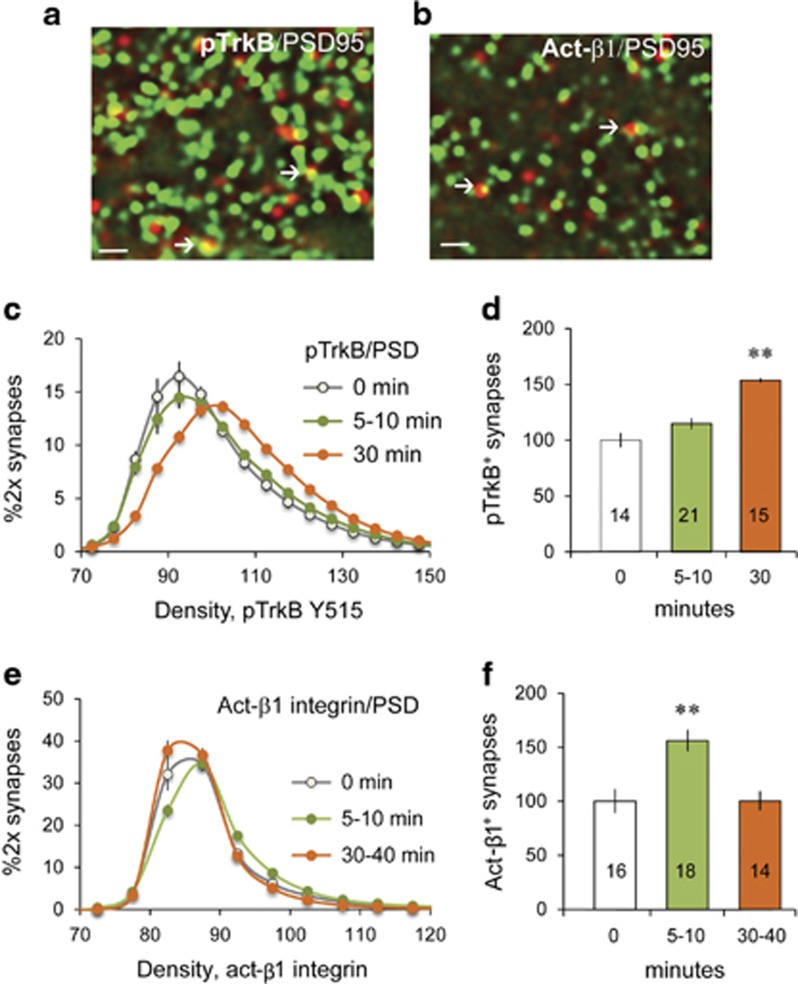

E2 Activates Synaptic TrkB and β1-Integrins

E2 initiates RhoA signaling leading to cofilin phosphorylation and actin polymerization in dendritic spines; this sequence is critical for response facilitation by the steroid (Kramar et al, 2009). Synaptic TrkB (Rex et al, 2007) and β1-integrins (Kramar et al, 2006) both promote the dendritic spine actin filament assembly that is essential for TBS-induced LTP. This raises the possibility that E2 produces its effects on actin, and thus on synaptic facilitation, by engaging one or both of these receptors.

We tested for TrkB activation in male rat slices using dual immunofluorescence and FDT to measure immunoreactivity (ir) for phosphorylated (p) TrkB Tyr515 (Chen et al, 2010) colocalized with PSD95 (Figure 2a). E2 perfusion caused a rightward shift in the intensity–frequency–distribution for pTrkB+ elements that was modest after 5–10 min but robust after 30 min relative to vehicle control (0 min) slices (p<0.0001), indicating that E2 increased pTrkB levels in the postsynaptic compartment (Figure 2c). As a consequence, the percentage of double-labeled contacts highly enriched in pTrkB (immunolabeling intensities >110) was significantly elevated at 30 min (Figure 2d).

Figure 2.

Estradiol (E2) perfusion activates synaptic TrkB and β1-integrin. (a and b) Images show dual immunolabeling for (a) postsynaptic density 95 (PSD95) (green) and pTrkB Y515 (red) and (b) for PSD95 (green) and activated β1 (red) (bar: 1.5 μm); double-labeled elements appear yellow (arrows). (c) Intensity frequency distributions for pTrkB-ir colocalized with PSD95 in slices collected before (0 min), 5–10 min, or 30 min after E2 perfusion onset (means±SEM): the 30 min curve was statistically different from 0 min baseline (F(56,1363)=9.82, p<0.0001, two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA)). (d) Plot of the percent of pTrkB+ PSDs with high density (≥110) pTrkB-ir normalized to the 0 min group mean shows an increase in densely pTrkB+ PSDs at 30 min only (F(2,49)=7.30; p<0.002, one-way ANOVA; **p<0.01, 30 vs 0 min). (e) Intensity frequency distributions for activated β1-ir plotted as in (c) (SEM bars smaller than icons): The 5–10 min curve was right-shifted relative to 0 min (F(56,1463)=3.87, p<0.0001, two-way ANOVA). (f) Percent of activated β1+ PSDs, normalized to ‘0 min' mean, shows an increase at 5–10 min (F(2,43)=11.81, p<0.0001, one-way ANOVA; **p<0.01, 5 vs 0 min). Numbers in bars denote the number of slices per group.

We used the same experimental design to test if E2 increases the proportion of excitatory synapses associated with activated β1-integrin (Figure 2b). E2 perfusion caused a pronounced rightward shift in the intensity–frequency–distribution for activated β1 colocalized with PSD95; the effect was robust at 5–10 min (p<0.0001) and greatly reduced by 30 min (Figure 2e). The percentage of PSDs associated with dense activated β1 immunolabeling was also elevated at 5–10 min but not 30 min time points (Figure 2f).

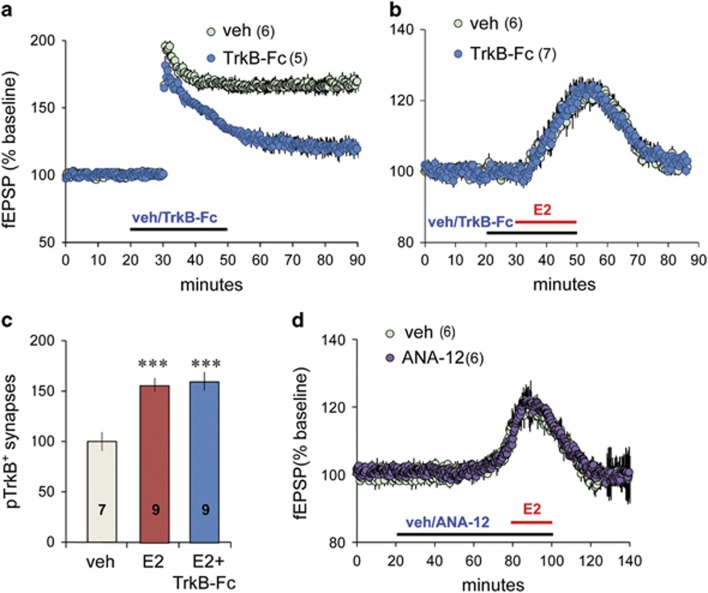

Effects of Sequestering BDNF or Blocking TrkB on E2-Induced Synaptic Facilitation

Next, we tested if BDNF is required for E2-driven TrkB activation and synaptic response facilitation in slices from male rats. TrkB-Fc scavenges extracellular BDNF (Shelton et al, 1995) and blocks TrkB activation in many experimental systems. It also prevents stable TBS-LTP (Rex et al, 2007). TrkB-Fc (2 μg/ml) pretreatment produced the predicted elimination of LTP (Figure 3a) but did not block E2's facilitation of transmission: The S-C fEPSP response facilitation after 30 min E2 perfusion was the same with and without TrkB-Fc present (veh: +20.0±1.59% TrkB-Fc: +22.20±3.87%) (Figure 3b). Moreover, E2-induced increases in postsynaptic pTrkB-ir were unaffected by TrkB-Fc (Figure 3c). These results indicate that E2's effects on synaptic TrkB constitute transactivation rather than changes in ligand action.

Figure 3.

Estradiol (E2) effects on transmission do not depend on brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) or TrkB signaling. (a) TrkB-Fc (2 μg/ml; at horizontal bar) blocked Schaffer-commissural (S-C) long-term potentiation (LTP) induced with theta burst stimulation (TBS) applied at 30 min (t(12)=3.83, p=0.002 vs veh at 55–60 min post-TBS; two-tailed t-test). (b) TrkB-Fc did not influence E2's effects on synaptic responses (t(9)=0.510, p=0.623 vs veh; two-tailed t-test). (c) The percentage of postsynaptic density 95-positive (PSD95+) elements colocalized with dense pTrkB-ir was similarly elevated in slices treated with E2 or E2+TrkB-Fc, relative to vehicle (veh) control values (F(2,22)=12.4, p=0.0002, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA); ***p<0.001 vs veh; Bonferroni's post hoc test). (d) ANA-12 (750 nM) did not block E2's effects on transmission (t(10)=0.25, p=0.81 vs veh; two-tailed t-test). Numbers within parentheses and on bars denote the number of slices per group. A full color version of this figure is available at the Neuropsychopharmacology journal online.

We tested if E2 effects on synaptic responses require TrkB activity. ANA-12 is a high-affinity TrkB antagonist shown to reduce BDNF-induced growth effects (Cazorla et al, 2011) and TrkB phosphorylation (M Chao, personal communication). At 500 nM ANA-12 disrupts field CA1 LTP in male slices (not shown). Here we used a higher concentration (750 nM) for 60 min before and during E2 treatment; ANA-12 did not diminish E2's enhancement of synaptic responses (E2: 19.76±3.49% E2+ANA-12: 20.18±2.20%) (Figure 3d).

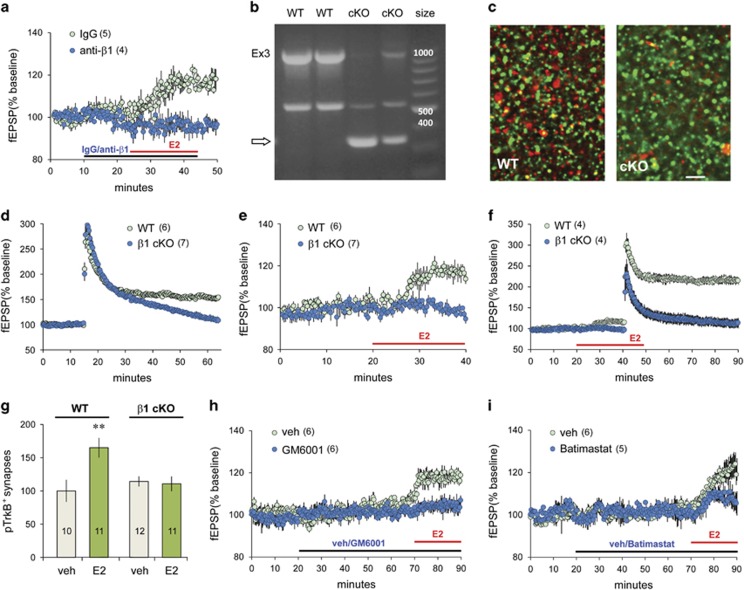

E2-Induced Synaptic Facilitation Depends Upon β1-Integrin Function

In contrast to effects of TrkB manipulation, perfusion of function blocking antisera for β1-integrin (Kramar et al, 2006) fully disrupted E2's enhancement of S-C responses, without altering baseline transmission (Figure 4a): the fEPSP slope in anti-β1-treated slices was 97.0±0.8% of pretreatment baseline just before E2 perfusion and 96.1±0.4% at its conclusion. This indicates that β1-integrin function is essential for E2-induced increases in fEPSPs. To further test this conclusion, we evaluated the effects of E2 perfusion in hippocampal slices from cKO mice in which hippocampal β1 expression is knocked down in CaMKII-expressing, excitatory neurons beginning at ~3 weeks of age; expression is retained in glia and GABAergic neurons (Chan et al, 2006). PCR analysis of genomic DNA (Figure 4b) and reverse-transcribed DNA purified from the hippocampus (not shown) verified the excision of β1 exon 3 and the presence of truncated mRNA transcripts in cKOs relative to floxed β1 wild types (WTs; lacking Cre-recombinase expression). Moreover, punctate β1-ir was markedly reduced in CA1 SR of cKOs relative to WTs (Figure 4c). Previous studies showed that LTP consolidation is blocked in β1 cKOs (Chan et al, 2006). We confirmed this result (Figure 4d) and then tested effects of E2 perfusion. E2 had no significant effect on synaptic responses in slices from β1 cKOs (Figure 4e), supporting the conclusion that β1-integrin function is essential for E2's actions on synaptic transmission. Moreover, application of TBS to E2-treated slices produced a markedly greater than normal LTP in WTs, as described previously (Bi et al, 2000; Foy et al, 1999), but failed to induce potentiation in β1 cKOs. (Figure 4f). Estrogen reduces feedback inhibition in the hippocampus (Steffensen et al, 2006), an effect that could potentially enhance LTP induction. However, applied E2 does not influence burst response facilitation during S-C TBS (Kramar et al, 2009); this indicates it acts primarily on events that follow initial induction at excitatory synapses.

Figure 4.

Estradiol's (E2's) effects on synaptic transmission depend upon β1-integrin function. (a) Plot of field CA1 excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs) shows that neutralizing anti-β1 blocked E2's enhancement of Schaffer-commissural (S-C) transmission (t(16)=2.78, p=0.013; two-tailed t-test for increase above baseline at 20 min post-E2 onset), whereas control immunoglobulin G (IgG) was without effect. (b) PCR products from hippocampal genomic DNA, for samples from homozygous floxed β1 wild types ‘WTs' (lacking Cre expression), and homozygous conditional β1-integrin knockout (cKO) mice, generated using primers that span β1 exon 3 (base pair size markers at right): WTs have a prominent ~1000 bp band reflecting the presence of the floxed β1 exon 3 (Ex 3; verified by sequencing), whereas the cKOs have a weak band at this position but a prominent band at 300 bp (arrow) corresponding to the recombined sequence generated with β1 exon 3 excised (Chan et al, 2006). (c) Deconvolved images of immunolabeling for postsynaptic density 95 (PSD95) (green) and β1-integrin (red) in CA1 SR show the marked reduction in punctate β1-ir in a cKO mouse relative to a paired floxed β1 WT; retention of some β1-ir is consistent with continued expression by glia and inhibitory neurons (bars=3 μm). (d) Theta burst stimulation (TBS)-induced long-term potentiation (LTP) was severely impaired in β1-integrin cKOs (t(11)=4.03, p=0.002 vs WT; two-tailed t-test). (e) E2 did not increase baseline transmission in β1 cKOs, although increases were robust in WTs (t(6)=5.05, p=0.002; two-tailed t-test at 20 min post-E2 onset). (f) In the same slices shown in (e), TBS-induced LTP was enhanced in E2-treated WT slices (110.9±5.43% over E2 baseline; ~2-fold normal, WT LTP effect) but was absent in E2-treated slices from β1 cKOs. (g) Fluorescence deconvolution tomography (FDT) quantification of densely pTrkB Y515-immunoreactive PSDs (immunolabeled for PSD95) shows an increase in pTrkB+ synapses with E2 vs vehicle (veh) treatment in field CA1 SR of floxed β1 WTs but not β1 cKOs (F(1,40)=7.23, p=0.0104, two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA); **p<0.01 for veh- vs E2-treated WT; p>0.05 for veh- vs E2-treated β1 cKOs; Bonferroni post hoc test). (h and i) Effects of E2 on baseline transmission were (h) absent in slices pretreated with the matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) inhibitor GM6001 (25 μM) (t(10)=3.67, p=0.004; two-tailed t-test for E2 vs E2+GM600 1% increase above baseline), and (i) reduced by MMP inhibitor batimastat (4 nM) (t(10)=4.27, p=0.034; two-tailed t-test for % increase above baseline).

Next, we asked if TrkB activation by perfused E2 is dependent on β1-integrins. Slices from β1 cKOs and floxed β1 WTs were treated with E2 for 30 min and then processed for dual immunofluorescence and FDT (as above). The increase in the proportion of PSDs associated with dense pTrkB-ir after E2 treatment was confirmed for WTs (p<0.001) but absent for β1 cKOs (Figure 4g). These results constitute the first evidence that integrins influence activation of synaptic TrkB.

Prior studies have shown that β1-integrin-dependent LTP is blocked by inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9) (Nagy et al, 2006; Wang et al, 2008), which cleaves matrix proteins to generate integrin ligands, and that E2 can increase extracellular MMP9 activity (Merlo and Sortino, 2012). We tested if MMP inhibition alters E2 actions on synaptic responses in slices from male rats. Perfusion of the broad-spectrum MMP inhibitor GM6001 (25 μM) blocked E2's facilitation of S-C fEPSPs (p=0.004) (Figure 4h). Perfusion of batimastat (4 nM), an inhibitor with greater selectivity for MMP2 and MMP9, significantly attenuated E2's response facilitation (p=0.034; Figure 4i). These results indicate that E2's activation of β1 is dependent on the generation of extracellular integrin ligands.

Discussion

We previously hypothesized that E2 perfusion generates a weak and unstable form of LTP (Kramar et al, 2009). Evidence for this came from the observation that E2 activates elements of actin signaling required for potentiation and that inhibiting this signaling eliminates E2's effects on synaptic responses. However, the hypothesis lacked information on how E2, presumably acting on membrane ERs, engages postsynaptic cytoskeletal signaling. One possibility is that ERβ, shown here and previously (Kramar et al, 2009; Smejkalova and Woolley, 2010) to mediate response facilitation, acts through G proteins to directly activate Rho GTPases leading to cofilin phosphorylation and actin filament assembly. An alternative explanation is that bound ERs act indirectly by stimulating other synaptic components that drive dendritic spine actin polymerization; we tested this point with regard to integrins and TrkB, previously shown to be critical for activity-regulated actin polymerization in field CA1 (Kramar et al, 2006; Rex et al, 2007).

We confirmed that ERα and ERβ are comparably abundant at PSDs in CA1 SR and, using receptor-specific antagonists, obtained evidence that ERβ mediates exogenous E2's synaptic response facilitation in slices from male rats. These results agree with reports that ERβ mediates postsynaptic actions of applied E2 in male CA1 (Kramar et al, 2009; Oberlander and Woolley, 2016). In contrast, ERβ antagonist PHTPP did not fully block E2's synaptic response facilitation in slices from female rats even though ERα and GPER1 antagonists were without effect. The latter result was surprising given evidence from studies using receptor agonists that ERβ is involved but GPER1 has a larger role in postsynaptic S-C response facilitation with E2 infusion in female rats (Kumar et al, 2015; Oberlander and Woolley, 2016). Clearly, more work is needed to understand the apparent discrepancies between these studies and sex differences in GPER1 regulation of synaptic transmission (Kumar et al, 2015). Although the present results imply that ERα does not mediate acute effects of exogenous E2 on synaptic physiology in either sex, our experiments did not specifically explore presynaptic actions of this receptor (Oberlander and Woolley, 2016) or possibilities that ERα may become involved when E2 is applied for longer intervals or at higher concentrations. The last point is important given the possibility that locally derived E2 can reach higher concentrations in the confined space of the synaptic junction (Ooishi et al, 2012).

Applied E2 increased the levels of activated (Y515-phosphorylated) TrkB at PSD95+ excitatory synapses within 30 min. This increase was not attenuated in the presence of BDNF scavenger TrkB-Fc, indicating that E2 signaling transactivates the BDNF receptor. Transactivation of TrkB, in the absence of BDNF, has been described for several treatments including 5-HT (Samarajeewa et al, 2014), epidermal growth factor (Puehringer et al, 2013), antidepressant drugs (Rantamaki et al, 2011), and adenosine (Rajagopal and Chao, 2006). Mechanisms are not fully resolved but links between G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and Src kinases are well established (Rajagopal and Chao, 2006). This is noteworthy because ERs signal through Src kinases (Bi et al, 2000) and Src inhibitors block TrkB phosphorylation associated with LTP (Chen et al, 2010). We therefore suggest that ERβ signaling through a Src kinase may mediate effects of E2 on TrkB.

The functional consequences of E2-induced TrkB transactivation are unclear: this response appears to be too slow to initiate the rapid effects of E2 on synaptic responses (within 5 min), although TrkB signaling may contribute to the maintenance of enhanced responses. It is interesting in this regard that TrkB-Fc does not affect the first few minutes of LTP but causes potentiation to decay thereafter. Moreover, we found the TrkB antagonist ANA-12, applied at concentrations that block TBS-induced LTP, did not attenuate E2's effects on S-C synaptic responses. This indicates that TrkB does not mediate the rapid effects of applied E2 on synaptic physiology. Another possibility is that E2's activation of TrkB contributes to the later production of new dendritic spines. We did not detect increases in PSDs after 30-min E2 perfusions, although initial spine changes may be evident at this time point. Further work is needed to determine if E2's transactivation of TrkB contributes to changes in spine and synapse numbers.

E2 caused synaptic β1-integrins to shift into their activated state and work with neutralizing antisera, and β1-integrin cKO mice showed that this effect is critical for exogenous E2's enhancement of S-C synaptic responses. Effects of E2 on synaptic integrins were rapid and brief: activated β1 levels were increased within 5–10 min but had subsided 25 min later. A similarly rapid and transient activation of synaptic β1-integrins was found in LTP experiments with activation peaking at 2 min post-TBS and dissipating within 10 min (Babayan et al, 2012).

Integrin transactivation occurs in a broad range of contexts and cell types, and is argued to be involved in clinically important conditions such as atherosclerosis and cancer. For example, the inflammatory mediator leukotriene B4 acting through a defined membrane receptor transactivates integrins leading to signaling through integrin-associated focal adhesion kinase and actin polymerization (Moraes et al, 2010). These events are present within 15 min and thus bear some resemblance to synaptic effects of perfused E2. A recent and detailed description of integrin transactivation by GPCRs concluded that two mechanisms are involved: (i) stimulation of the small GTPase Rap1 and actions on submembrane proteins (kindlins) that promote integrin activation, and (ii) recruitment of adaptor proteins to the C terminus of the β-integrin subunit (Ortega-Carrion et al, 2015). The present studies also provide evidence that β1-integrins are necessary for E2's activation of TrkB. This was not entirely unexpected given that integrins interact with other transmembrane proteins, including growth factor receptors, in many circumstances (Meng et al, 2011; Munger and Sheppard, 2011). However, synaptic TrkB activation could also be secondary to rapid cytoskeletal changes that accompany integrin activation, events that may influence the status of various membrane receptors. It is also possible that the enhanced synaptic responses elicited by E2, which require functional β1-integrins, produce effects that alter the status of synaptic TrkB. Resolving these questions will be a challenging but necessary step in explicating E2's actions on excitatory transmission.

Further work showed that MMP inhibition blocks the effects of E2 on synaptic physiology. These extracellular enzymes both generate integrin ligands from the extracellular matrix and process proBDNF to produce the mature neurotrophin (Ethell and Ethell, 2007). However, given evidence that neither BDNF sequestration with TrkB-Fc nor TrkB antagonism disrupts E2's facilitation of synaptic responses, the MMPs most likely contribute to E2's effects on transmission by enabling integrin activities. It is possible that constitutive MMP activity is required to maintain an integrin ligand pool. Alternatively, perfused E2 may activate MMPs, as previously reported for neuroblastoma (Merlo and Sortino, 2012), which then produce integrin ligands. Past work showed that induction of field CA1 LTP activates MMP9, and that blocking the proteinase disrupts potentiation (Nagy et al, 2006; Wang et al, 2008). Moreover, perfusion of activated MMP9 initiates β1-integrin-mediated signaling to cofilin, actin polymerization, and potentiation of synaptic responses. Related to this, LTP stabilization is prevented by intracellular application of agents that block exocytosis (Wang et al, 2008). Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) is one candidate for the releasable intermediary: E2 stimulates tPA secretion (Hoetzer et al, 2003) and, via generation of extracellular plasmin, it activates MMPs (Tsilibary et al, 2014). As inhibitors of tPA block LTP (Hoffman et al, 1998), it should be straightforward to test if they similarly block E2-induced increases in fast, excitatory synaptic transmission.

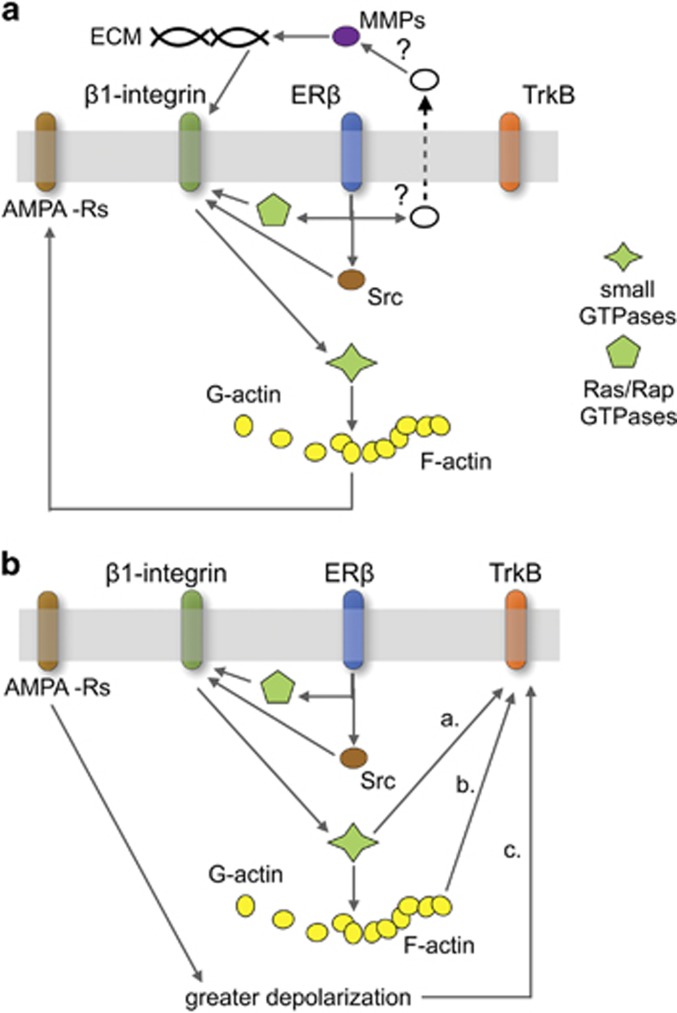

The above arguments can be summarized in a simplified, provisional model of how E2 enhances EPSPs and primes synapses for LTP (Figure 5). Importantly, this scheme does not specifically address E2's actions on transmission in females, where the situation is likely more complicated than in males. E2 is synthesized within axon terminals and in hippocampal field CA1 locally produced E2 is required for LTP in females only (Vierk et al, 2012). There is also evidence from whole-cell recordings that exogenous E2 has synapse-specific effects on pre- vs postsynaptic mechanisms that differ between males and females (Oberlander and Woolley, 2016). Information on whether transactivation events shown here to mediate the effects of exogenous E2 in males are also engaged by agonists for the different ERs, and by locally derived E2 most particularly in females, should provide better understanding of synapse- and region-specific E2 actions (Briz et al, 2015; Oberlander and Woolley, 2016) and the larger question of sex differences in learning-related synaptic plasticity.

Figure 5.

Proposed mechanisms whereby exogenous estradiol (E2) enhances fast excitatory transmission in adult male hippocampus. (a) Rapid E2 effects involving β1-integrins. Published work indicates that perfused E2 acting through synaptic estrogen receptor-β (ERβ) engages Src family kinases and Ras/Rap GTPases, and releases factors (eg, tPA: ‘?') that activate extracellular matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs); together, these intra- and extracellular events shift synaptic β1-integrins into their activated configuration. Integrins then drive downstream small Rho GTPases that enable local polymerization of filamentous actin (F-actin) from actin monomers (G-actin); this cytoskeletal reorganization affects AMPA receptors (AMPA-Rs) so as to increase the effects of released glutamate, resulting in enhanced synaptic currents. (b) Delayed activation of TrkB. Integrin signaling set in motion by E2/ERβ could affect TrkB through three routes: a. transactivation resulting from β1-dependent stimulation of small GTPases; b. formation and elaboration of actin networks that affect the probability of TrkB phosphorylation; and c. enhanced depolarization produced by afferent activity, an effect dependent on β1-integrin activation. Earlier work showing that actin polymerization is critical for E2's enhancement of synaptic transmission favors hypothesis ‘b'. A full color version of this figure is available at the Neuropsychopharmacology journal online.

Funding and disclosure

The authors declare that this work was funded by NINDS grants NS045260, NS085709 and T32 NS45540 (the latter supported SK) and by funds from the Thompson Foundation to the UCI Center for Autism Research and Translation. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Ivan Soltesz for providing CaMKII-Cre mice used for generating the β1 cKOs, Dr Moses Chao for information on TrkB antagonists, and Dr Julie Lauterborn for comments on the manuscript.

References

- Babayan AH, Kramar EA, Barrett RM, Jafari M, Haettig J, Chen LY et al (2012). Integrin dynamics produce a delayed stage of long-term potentiation and memory consolidation. J Neurosci 32: 12854–12861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi R, Broutman G, Foy MR, Thompson RF, Baudry M (2000). The tyrosine kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways mediate multiple effects of estrogen in hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 3602–3607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briz V, Liu Y, Zhu G, Bi X, Baudry M (2015). A novel form of synaptic plasticity in field CA3 of hippocampus requires GPER1 activation and BDNF release. J Cell Biol 210: 1225–1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazorla M, Premont J, Mann A, Girard N, Kellendonk C, Rognan D (2011). Identification of a low-molecular weight TrkB antagonist with anxiolytic and antidepressant activity in mice. J Clin Invest 121: 1846–1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CS, Weeber EJ, Zong L, Fuchs E, Sweatt JD, Davis RL (2006). Beta 1-integrins are required for hippocampal AMPA receptor-dependent synaptic transmission, synaptic plasticity, and working memory. J Neurosci 26: 223–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LY, Rex CS, Sanaiha Y, Lynch G, Gall CM (2010). Learning induces neurotrophin signaling at hippocampal synapses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 7030–7035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMali KA, Wennerberg K, Burridge K (2003). Integrin signaling to the actin cytoskeleton. Curr Opin Cell Biol 15: 572–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ethell IM, Ethell DW (2007). Matrix metalloproteinases in brain development and remodeling: synaptic functions and targets. J Neurosci Res 85: 2813–2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fester L, Rune GM (2015). Sexual neurosteroids and synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus. Brain Res 1621: 162–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foy MR, Xu J, Xie X, Brinton RD, Thompson RF, Berger TW (1999). 17Beta-estradiol enhances NMDA receptor-mediated EPSPs and long-term potentiation. J Neurophysiol 81: 925–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara Y, Waters EM, McEwen BS, Morrison JH (2015). Estrogen effects on cognitive and synaptic health over the lifecourse. Physiol Rev 95: 785–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoetzer GL, Stauffer BL, Irmiger HM, Ng M, Smith DT, DeSouza CA (2003). Acute and chronic effects of oestrogen on endothelial tissue-type plasminogen activator release in postmenopausal women. J Physiol 551: 721–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman KB, Martinez J, Lynch G (1998). Proteolysis of cell adhesion molecules by serine proteases: a role in long term potentiation? Brain Res 811: 29–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramar EA, Chen LY, Brandon NJ, Rex CS, Liu F, Gall CM et al (2009). Cytoskeletal changes underlie estrogen's acute effects on synaptic transmission and plasticity. J Neurosci 29: 12982–12993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramar EA, Lin B, Rex CS, Gall CM, Lynch G (2006). Integrin-driven actin polymerization consolidates long-term potentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 5579–5584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Bean LA, Rani A, Jackson T, Foster TC (2015). Contribution of estrogen receptor subtypes, ERalpha, ERbeta, and GPER1 in rapid estradiol-mediated enhancement of hippocampal synaptic transmission in mice. Hippocampus 25: 1556–1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leranth C, Shanabrough M, Horvath TL (2000). Hormonal regulation of hippocampal spine synapse density involves subcortical mediation. Neuroscience 101: 349–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luine VN, Frankfurt M (2012). Estrogens facilitate memory processing through membrane mediated mechanisms and alterations in spine density. Front Neuroendocrinol 33: 388–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng R, Tang HY, Westfall J, London D, Cao JH, Mousa SA et al (2011). Crosstalk between integrin alphavbeta3 and estrogen receptor-alpha is involved in thyroid hormone-induced proliferation in human lung carcinoma cells. PLoS One 6: e27547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlo S, Sortino MA (2012). Estrogen activates matrix metalloproteinases-2 and -9 to increase beta amyloid degradation. Mol Cell Neurosci 49: 423–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranti CK, Brugge JS (2002). Sensing the environment: a historical perspective on integrin signal transduction. Nat Cell Biol 4: 83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moraes J, Assreuy J, Canetti C, Barja-Fidalgo C (2010). Leukotriene B4 mediates vascular smooth muscle cell migration through alphavbeta3 integrin transactivation. Atherosclerosis 212: 406–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortillo S, Elste A, Ge Y, Patil SB, Hsiao K, Huntley GW et al (2012). Compensatory redistribution of neuroligins and N-cadherin following deletion of synaptic beta1-integrin. J Comp Neurol 520: 2041–2052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukai H, Tsurugizawa T, Murakami G, Kominami S, Ishii H, Ogiue-Ikeda M et al (2007). Rapid modulation of long-term depression and spinogenesis via synaptic estrogen receptors in hippocampal principal neurons. J Neurochem 100: 950–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munger JS, Sheppard D (2011). Cross talk among TGF-beta signaling pathways, integrins, and the extracellular matrix. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 3: a005017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy V, Bozdagi O, Matynia A, Balcerzyk M, Okulski P, Dzwonek J et al (2006). Matrix metalloproteinase-9 is required for hippocampal late-phase long-term potentiation and memory. J Neurosci 26: 1923–1934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni H, Li A, Simonsen N, Wilkins JA (1998). Integrin activation by dithiothreitol or Mn2+ induces a ligand-occupied conformation and exposure of a novel NH2-terminal regulatory site on the beta1 integrin chain. J Biol Chem 273: 7981–7987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberlander JG, Woolley CS (2016). 17Beta-estradiol acutely potentiates glutamatergic synaptic transmission in the hippocampus through distinct mechanisms in males and females. J Neurosci 36: 2677–2690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooishi Y, Kawato S, Hojo Y, Hatanaka Y, Higo S, Murakami G et al (2012). Modulation of synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus by hippocampus-derived estrogen and androgen. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 131: 37–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Carrion A, Feo-Lucas L, Vincente-Manzanares M (2015) Cell migrationIn:Bradshaw RA, Stahl PD(eds) Encyclopedia of Cell Biology Vol 2. Academic Press: New York, NY. pp 720–730. [Google Scholar]

- Panja D, Bramham CR (2014). BDNF mechanisms in late LTP formation: a synthesis and breakdown. Neuropharmacology 76(Part C): 664–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puehringer D, Orel N, Luningschror P, Subramanian N, Herrmann T, Chao MV et al (2013). EGF transactivation of Trk receptors regulates the migration of newborn cortical neurons. Nat Neurosci 16: 407–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopal R, Chao MV (2006). A role for Fyn in Trk receptor transactivation by G-protein-coupled receptor signaling. Mol Cell Neurosci 33: 36–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rantamaki T, Vesa L, Antila H, Di Lieto A, Tammela P, Schmitt A et al (2011). Antidepressant drugs transactivate TrkB neurotrophin receptors in the adult rodent brain independently of BDNF and monoamine transporter blockade. PLoS One 6: e20567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rex CS, Chen LY, Sharma A, Liu J, Babayan AH, Gall CM et al (2009). Different Rho GTPase-dependent signaling pathways initiate sequential steps in the consolidation of long-term potentiation. J Cell Biol 186: 85–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rex CS, Lin CY, Kramar EA, Chen LY, Gall CM, Lynch G (2007). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor promotes long-term potentiation-related cytoskeletal changes in adult hippocampus. J Neurosci 27: 3017–3029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samarajeewa A, Goldemann L, Vasefi MS, Ahmed N, Gondora N, Khanderia C et al (2014). 5-HT7 receptor activation promotes an increase in TrkB receptor expression and phosphorylation. Front Behav Neurosci 8: 391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seese RR, Babayan AH, Katz AM, Cox CD, Lauterborn JC, Lynch G et al (2012). LTP induction translocates cortactin at distant synapses in wild-type but not Fmr1 knock-out mice. J Neurosci 32: 7403–7413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seese RR, Chen LY, Cox CD, Schulz D, Babayan AH, Bunney WE et al (2013). Synaptic abnormalities in the infralimbic cortex of a model of congenital depression. J Neurosci 33: 13441–13448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton DL, Sutherland J, Gripp J, Camerato T, Armanini MP, Phillips HS et al (1995). Human Trks: molecular cloning, tissue distribution, and expression of extracellular domain immunoadhesions. J Neurosci 15: 477–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons DA, Belichenko NP, Yang T, Condon C, Monbureau M, Shamloo M et al (2013). A small molecule TrkB ligand reduces motor impairment and neuropathology in R6/2 and BACHD mouse models of Huntington's disease. J Neurosci 33: 18712–18727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smejkalova T, Woolley CS (2010). Estradiol acutely potentiates hippocampal excitatory synaptic transmission through a presynaptic mechanism. J Neurosci 30: 16137–16148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer JL, Waters EM, Romeo RD, Wood GE, Milner TA, McEwen BS (2008). Uncovering the mechanisms of estrogen effects on hippocampal function. Front Neuroendocrinol 29: 219–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffensen SC, Jones MD, Hales K, Allison DW (2006). Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate and estrone sulfate reduce GABA-recurrent inhibition in the hippocampus via muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Hippocampus 16: 1080–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trieu BH, Kramar EA, Cox CD, Jia Y, Wang W, Gall CM et al (2015). Pronounced differences in signal processing and synaptic plasticity between piriform-hippocampal network stages: a prominent role for adenosine. J Physiol 593: 2889–2907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien JZ, Chen DF, Gerber D, Tom C, Mercer EH, Anderson DJ et al (1996). Subregion- and cell type-restricted gene knockout in mouse brain. Cell 87: 1317–1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsilibary E, Tzinia A, Radenovic L, Stamenkovic V, Lebitko T, Mucha M et al (2014). Neural ECM proteases in learning and synaptic plasticity. Prog Brain Res 214: 135–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vierk R, Glassmeier G, Zhou L, Brandt N, Fester L, Dudzinski D (2012). Aromatase inhibition abolishes LTP generation in female but not in male mice. J Neurosci 32: 8116–8126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XB, Bozdagi O, Nikitczuk JS, Zhai ZW, Zhou Q, Huntley GW (2008). Extracellular proteolysis by matrix metalloproteinase-9 drives dendritic spine enlargement and long-term potentiation coordinately. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 19520–19525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuen GS, McEwen BS, Akama KT (2011). LIM kinase mediates estrogen action on the actin depolymerization factor Cofilin. Brain Res 1379: 44–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]