Abstract

Objectives

To quantify associations between inflammatory biomarkers and hippocampal volume (HV), and examine effect modification by sex, race, and age.

Design

Cross-sectional analyses using generalized estimating equations to account for familial clustering; standardized β-coefficients, adjusted for age, sex, race, and education.

Setting

Community cohorts in Jackson, Mississippi and Rochester, Minnesota.

Participants

The Genetic Epidemiology Network of Arteriopathy (GENOA) study.

Measurements

C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin-6 (IL-6), soluble tumor necrosis factor receptors 1 (sTNFR-1) and 2 (sTNFR-2) from peripheral blood were measured in a sample of 773 non-Hispanic Whites (61% women, age 60.2±9.8) and 514 African Americans (70% women, age 63.9±8.1) who also underwent brain magnetic resonance imaging. Biomarkers were standardized and compared across sex, race and age to HV.

Results

In the full sample, higher sTNFR-1 and sTNFR-2 were associated with smaller HV. Each SD increase in sTNFR-1 was associated with −59.1mm3 (95%CI:−101.4,−16.7) smaller HV and each SD increase in sTNFR-2 associated with −48.8mm3 (95%CI:−92.2,−5.3) smaller HV. Relationships were stronger for sTNFR-2 in men (HV=−116.6mm3 for each SD increase, 95%CI:−201.0,−32.1) than women (HV=−26.0 per SD increase, 95%CI:−72.4,20.5) and sTNFR-1 in non-Hispanic whites (HV=−84.7mm3 per SD increase, 95%CI:−142.2,−27.1) than African Americans (HV=−14.1mm3 per SD increase, 95%CI:−78.3,50.1). Associations between IL-6 or CRP and HV were not supported.

Conclusion

Higher levels of sTNFRs were associated cross-sectionally with smaller hippocampi. Longitudinal data are needed to determine whether these biomarkers may help to identify increased risk of late life cognitive impairment.

Keywords: inflammation, hippocampus, TNFα

INTRODUCTION

Inflammation increases with age1,2 and has been associated with several major degenerative diseases affecting older adults including cognitive decline3–8 and dementia9–13. Elevated levels of inflammatory biomarkers, including interleukin-6 (IL-6)14–16, C-reactive protein (CRP)17,18, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα)19, have been associated with poorer cognitive function3,7,20,21 and Alzheimer Disease (AD)14,15,17. We previously reported associations between these biomarkers and cognitive function and found differential effects by race with more associations observed in African-Americans (AA) compared to non-Hispanic whites (NHW)6. Mechanisms linking inflammation to cognitive decline and dementia have been suggested that involve inflammatory-mediated effects on neurodegenerative pathologies (e.g., related to amyloid deposition)9,11, cerebrovascular changes19,22,23, or both.

The hippocampus plays an essential and well-known role in learning and memory24. Hippocampal volume (HV) declines with age25,26 and is one of the earliest structures affected by neurodegeneration in AD. Given its prominent role in memory and dementia, and ready quantification via magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, the hippocampus offers an informative target to evaluate the effects of inflammation on brain structure. We are aware of only one prior human study linking peripheral inflammation to HV in disease-free participants, and it reported an inverse relationship between IL-6 and HV in a small (n = 76) cohort of younger adults (30–54)27. Although AA have differing levels of inflammation compared to NHW28 and a higher burden of dementia29,30, we are aware of no prior studies that have examined inflammation and HV in a community sample including AA.

In the current study, we examined the relationships of the inflammatory biomarkers high sensitivity CRP, IL-6, and soluble TNFα receptors (sTNFR-1, sTNFR-2) with HV in a hypertension-enriched, community sample of NHW and AA men and women free from stroke and dementia from the Genetic Epidemiology Network of Arteriopathy (GENOA) cohort31. We hypothesized that higher levels of inflammation would be associated with smaller HV. Differential effects for sex, race and age were also examined.

METHODS

Study Population

The GENOA study began in 1995, with a cohort of hypertensive individuals and their siblings recruited from Jackson, Mississippi (n = 1,854 participants; 69% women; mean 58 yrs old at enrollment; AA only) and Rochester, Minnesota (n = 1,578 participants; 56% women; 55 yrs old at enrollment; NHW only)31. The AA sibships from Jackson, MS were recruited from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study.32 The NHW sibships from Rochester, MN were recruited from the Rochester Epidemiology Project.33 At least two members of each sibship had hypertension before age 60 at enrollment. Inflammatory markers were assayed at the second examination (GENOA Visit 2, 2000–2004) (n = 1,324 AA, 1,237 NHW). Coinciding with or following Visit 2, as a part of the Genetics of Microangiopathic Brain Injury (GMBI) ancillary study, MR imaging was conducted on 830 AA and 916 NHW participants.

For the current analysis, the sample consisted of participants for whom both inflammatory markers from GENOA Visit 2 and MR imaging from GMBI (n = 1,383 total; 580 AA, 803 NHW) were available. Participants were excluded who had unsuitable MR imaging or image analysis (n = 23), or had a history of stroke (5 AA, 9 NHW), self-reported use of steroids (1 AA), or with possible dementia (Mini Mental State Exam [MMSE] score < 24, n = 58), leaving 514 AA and 773 NHW (Total 1,287/1,383 = 93%) for analysis.

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

Study approval was provided by the Institutional Review Boards of The University of Mississippi Medical Center and The Mayo Clinic. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Inflammatory Markers

Fasting blood samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 4°C, aliquoted in 0.5–1 mL volumes of EDTA plasma (serum for CRP), and stored at −80°C within 2 h of venipuncture. Frozen samples from the Jackson field center were shipped to the Mayo Clinic Immunochemical Core Laboratory (Rochester, MN) overnight on dry ice. Samples were thawed on ice, repackaged into Eppendorf tubes with bar codes and refrozen for shipping to SearchLight™ (ThermoScientific). CRP assays were performed using immunoturbidometric assays (Diasorin, Inc, Stillwater, MN; inter-assay imprecision 1.8–2.6%; intra-assay imprecision 1.0–9.2%) and multiplex assays (SearchLight™, Pierce, Boston, MA) were used for IL-6 and sTNFRs. sTNFR fractions show stability over time with longer half-lives than TNFα levels and have been validated as sensitive indicators of TNFα system activation34. Precision of the assays performed by SearchLightTM was retrospectively determined based on data derived from a blinded, internal plasma control sample. Algorithms were developed to reduce plate-to-plate variations in protein levels and all analyses used these normalized data.35

MR Imaging and Hippocampal Volume

All HV and total intracranial volume (TIV) measurements were taken from MR images performed on GE Signa 1.5T MRI scanners, identically equipped at each study site. Multiple sequences were performed, as previously described36,37. This study utilized data generated from T1-weighted coronal 3D spoiled gradient echo (SPGR) images consisting of 124 contiguous 1.6mm thick coronal slices obtained with a 256×192×124 matrix, 6–10ms echo time, 24ms repetition time, 25 degree flip angle, 24cm × 18cm × 19.8cm FOV.

Each 3D SPGR image was secure-copied to the Mississippi Center for Supercomputing Research and processed by Freesurfer 5.3.038 with default settings. Freesurfer is documented and freely available for download online (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu). Briefly, this processing includes motion correction and removal of non-brain tissue using a hybrid watershed/surface deformation procedure, automated Talairach transformation, segmentation of the subcortical white matter and deep gray matter volumetric structures (including hippocampus, amygdala, caudate, putamen, ventricles), intensity normalization, tessellation of the gray matter white matter boundary, automated topology correction, and surface deformation following intensity gradients to optimally place the gray/white and gray/cerebrospinal fluid borders at the location where the greatest shift in intensity defines the transition to the other tissue class. Maps are created using spatial intensity gradients across tissue classes and are therefore not simply reliant on absolute signal intensity. The maps produced are not restricted to the voxel resolution of the original data thus are capable of detecting submillimeter differences between groups. Freesurfer morphometric procedures have been demonstrated to show good test-retest reliability across scanner manufacturers and across field strengths39,40.

Output from Freesurfer was manually checked by viewing the results in tkmedit, part of the Freesurfer software suite. This quality control resulted in the exclusion of 10 participants for incorrect image orientation, 3 with insufficient contrast, 10 with severe ventriculomegaly, and one with a large tumor affecting the hippocampus. These exclusions are accounted for above as “unsuitable” in the population section.

HVs were reported for the right and left hemispheres in Freesurfer’s aseg.stats file. The combined HV reported here is the sum of the right and left values. The TIV measurement used for adjustment in generalized estimating equations (GEE) was generated by tracing the inner boundary of the skull in separately acquired T2-weighted images as reported previously36.

Covariates

Level of education was assessed by questionnaire and reported as years of education. Blood pressure, measured three times in a seated, rested state with appropriately sized cuffs, was defined as the average of the 2nd and 3rd measurements. Hypertension was defined as a blood pressure >140/90 mm Hg, self-report, or anti-hypertensive medication use. Diabetes was defined as fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dl or random ≥200 mg/dl, self-report, or hypoglycemic medication use. Height was measured by stadiometer and weight by electronic balance with participants wearing lightweight clothes. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kilograms)/height2 (meters).

Statistical Analysis

Associations between each inflammatory marker and HV were estimated using linear models fit with GEE to account for familial clustering and Huber-White robust standard error estimates. Because the inflammatory markers have different measurement units, measurements were standardized to facilitate interpretation across models. In this report, a beta coefficient of −10.0 is interpreted as a 10.0mm3 decrease in HV associated with each SD increase in an inflammatory marker. Diagnostic lowess smoothers revealed linear relationships on the natural scale, inflammatory markers were only mildly skewed, and estimates were resistant to extreme value effects. For these reasons, associations with standardized inflammatory markers were performed without log-transformation. Primary models regressed each biomarker on HV adjusting for age, sex, race, TIV, and education as independent (additive) estimators, and accounted for familial clustering using Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE). Additional models examined effect modification by incorporating interaction terms of inflammatory markers with race, sex, and age decade; stratified models were examined when effect modification was supported. In secondary analyses, we also adjusted for diabetes, hypertension, BMI, and anti-inflammatory and anti-hypertensive medication use. Sensitivity analyses were performed including participants who were excluded because of low MMSE, and without adjustment for TIV. We acknowledge that race and site are aliased by design. Analyses were performed using Stata 1341.

RESULTS

The overall sample of 1,287 participants was 64% women, 40% AA, with a mean age of 62 years (range: 33–91), and 74% hypertensive. Men had lower levels of CRP compared to women, and AA participants had lower levels of both sTNFR-1 and sTNFR-2, and higher levels of CRP and IL-6 compared to NHW (Table 1). Participants in the analyses were slightly more educated (13.3 yrs vs 12.2, p<0.001) and less likely to be AA (39.9% vs 67.4%, p<0.001) compared to those who were excluded.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics by Sex and Race.

| Non-Hispanic Whites | African Americans | Total | Difference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 773 (60%) | 514 (40%) | ||||||

| Women | Men | Women | Men | Sex | Race | ||

| 469 (36%) | 304 (24%) | 359 (28%) | 155 (12%) | 1,287 (100%) | p < 0.05 | ||

| Age (years)a | 59.8 (9.9) | 60.9 (9.5) | 64.2 (7.9) | 63.3 (8.6) | 61.7 (9.3) | * | * |

| BMI (kg/m2)a | 30.1 (6.7) | 29.9 (5.0) | 31.3 (5.9) | 28.2 (4.3) | 30.1 (5.9) | * | * |

| Hypertensive (%) | 340 (72%) | 230 (76%) | 282 (79%) | 105 (68%) | 957 (74%) | * | |

| Diabetic (%) | 36 (8%) | 32 (11%) | 56 (16%) | 22 (14%) | 146 (11%) | * | |

| Ever smoked (%) | 189 (40%) | 179 (59%) | 111 (31%) | 95 (61%) | 574 (45%) | * | * |

| MMSE (0–30)a | 29.1 (1.2) | 28.6 (1.5) | 27.6 (1.8) | 27.8 (1.7) | 28.4 (1.6) | * | * |

| Education (yrs) a | 13.5 (2.1) | 13.6 (2.7) | 13.0 (3.2) | 13.1 (3.6) | 13.3 (2.8) | * | |

|

| |||||||

| Beta blocker (%) | 158 (34%) | 98 (32%) | 48 (13%) | 19 (12%) | 323 (25%) | * | |

| Ca channel (%) | 64 (14%) | 47 (15%) | 94 (26%) | 38 (25%) | 243 (19%) | * | |

| RAAS (%) | 132 (28%) | 123 (40%) | 133 (37%) | 40 (26%) | 428 (33%) | ||

| Sympatholytic (%) | 4 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 11 (3%) | 3 (2%) | 18 (1%) | * | |

| Alpha blocker (%) | 1 (0%) | 18 (6%) | 10 (3%) | 13 (8%) | 42 (3%) | * | * |

| Vasodilator (%) | 2 (0%) | 1 (0%) | 1 (0%) | 3 (2%) | 7 (1%) | ||

| Diuretic (%) | 198 (42%) | 98 (32%) | 163 (45%) | 50 (32%) | 509 (40%) | * | |

| NSAID (%) | 60 (13%) | 39 (13%) | 65 (18%) | 10 (6%) | 174 (14%) | * | |

| NN analgesic (%) | 144 (31%) | 141 (46%) | 91 (25%) | 41 (26%) | 417 (32%) | * | * |

|

| |||||||

| CRP (mg/L) a | 5.19 (5.51) | 3.11 (4.25) | 6.29 (6.69) | 4.36 (5.99) | 4.91 (5.78) | * | * |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) a | 7.96 (5.58) | 9.14 (7.40) | 9.27 (6.32) | 8.76 (6.57) | 8.70 (6.40) | * | |

| sTNFR-1 (pg/mL) a | 1,341 (702) | 1,390 (621) | 1,182 (640) | 1,083 (482) | 1,276 (650) | * | |

| sTNFR-2 (pg/mL) a | 1,962 (894) | 1,972 (694) | 1,882 (863) | 1,751 (657) | 1,920 (817) | * | |

|

| |||||||

| TIV (cm3) a | 1,463 (162) | 1,722 (139) | 1,318 (189) | 1,615 (147) | 1,502 (223) | * | * |

| Left HV (mm3) a | 3,945 (448) | 4,173 (467) | 3,708 (433) | 3,974 (494) | 3,936 (484) | * | * |

| Right HV (mm3) a | 3,978 (437) | 4,271 (473) | 3,811 (393) | 4,078 (520) | 4,013 (475) | * | * |

Values are mean (standard deviation).

Kruskal-Wallis rank tests for sex or race differences significant to p<0.05 are indicated with an asterisk. BMI = body mass index; MMSE = Mini mental status exam; CRP = C-reactive protein; NSAID = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; NN = non-narcotic; RAAS = renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors; IL-6 = interleukin-6; sTNFR = soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor; TIV = total intracranial volume; HV = hippocampal volume.

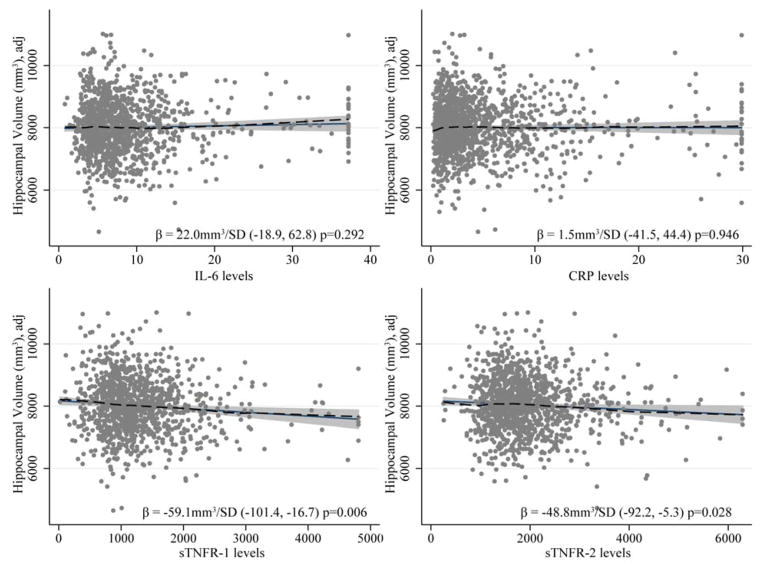

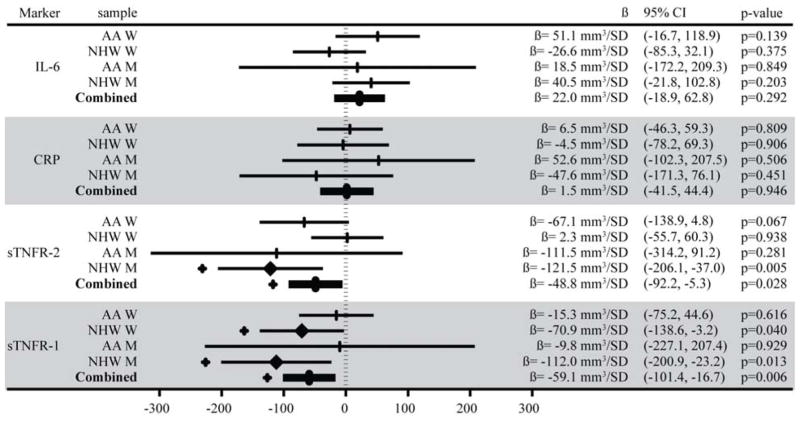

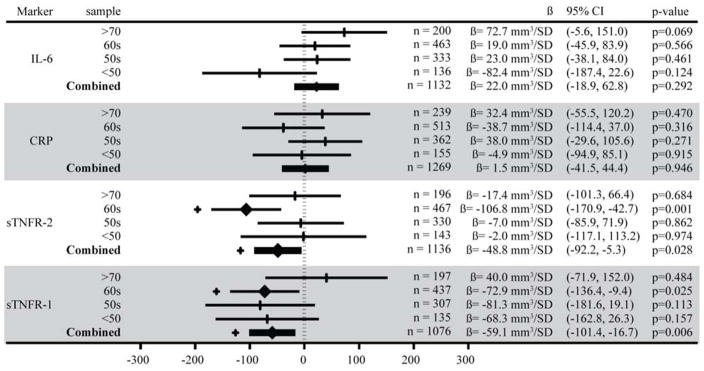

Both sTNFR-1 and sTNFR-2 were inversely associated with HV. Each SD increase in sTNFR-1 (650pg/mL) was associated with a smaller HV of −59.1mm3 (95% CI: −16.7, −101.4) and each SD increase in sTNFR-2 (817pg/mL) with a smaller HV of −48.8mm3 (95% CI: −5.3, −92.2). (Figure 1 and 2). The association between sTNFR-2 and HV varied by both sex (p=0.016) and age (over/under 60 p=0.035). This association was stronger for men (HV = −116.6mm3 per SD increase in sTNFR-2, 95% CI: −201.0, −32.1) than women (HV = −26.0mm3 per SD increase in sTNFR-2, 95% CI: −72.4, 20.5), and participants in their 60s had a stronger association (HV = −106.8mm3, 95% CI: −170.9, −42.7) than any other age group. (Figure 3). The inverse association between sTNFR-1 and HV was significant in NHW (HV = −84.7mm3 per SD increase in sTNFR-1, 95%CI: −142.2, −27.1, p=0.004), and not in AA (HV = −14.1mm3 per SD increase in sTNFR-1, 95% CI: −78.3, 50.1, p=0.667), but the race interaction was not significant (p=0.228).

Figure 1.

Each marker’s association to hippocampal volume was subjected to an adjusted linear model in the entire sample as shown. The solid black lines show the linear relationships, dashed lines show lowess diagnostic smoothers supporting linearity assumptions. The β value is interpreted as the difference in hippocampal volume associated with a standard deviation increase in the marker level. Plotted points and associations are adjusted for age, intracranial volume, education, sex and race. Inflammatory marker levels were Winsorized to avoid extreme outlier effects; results were robust to exclusion of these points.

Figure 2.

A forest plot showing the confidence intervals and β coefficients from a GEE of standardized inflammatory marker measurements on hippocampal volume, adjusted for age, total intracranial volume, education, sex, and race. Values along the x-axis indicate the volume of hippocampus (mm3) associated with a standard deviation increase in levels of the inflammatory marker. Associations with p<0.05 are marked with a heavy diamond at the β value and a + outside the confidence interval. AA = African American; NHW = non-Hispanic White; W = women; M = men. IL-6 = interleukin-6; CRP = C-reactive protein; sTNFR = soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor. SD = standard deviation.

Figure 3.

A forest plot showing the confidence intervals and β coefficients from a linear regression of standardized inflammatory marker measurements on hippocampal volume, stratified by age, then adjusted for age, total intracranial volume, education, sex, and race. Values along the x-axis indicate the volume of hippocampus (mm3) associated with a standard deviation increase in levels of the inflammatory marker. Associations with p<0.05 are marked with a heavy diamond at the β value and a + outside the confidence interval. IL-6 = interleukin-6; CRP = C-reactive protein; sTNFR = soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor. SD = standard deviation.

No significant associations were observed for IL-6 or CRP and no additional interactions by race, sex or age were observed. Secondary analyses adjusting for hypertension, BMI, diabetes, and use of anti-inflammatory or anti-hypertensive medications did not significantly alter the relationships between HV and any inflammatory marker. Effect modification was also examined for anti-inflammatory and anti-hypertensive medication use by incorporating these as interaction terms, but no evidence of effect modification was observed. Sensitivity analyses including participants with probable dementia, without adjustment for TIV, or excluding participants with outlier levels of inflammatory markers had little effect on model estimates (results not shown).

DISCUSSION

In this community-based biracial sample of 1,287 men and women, we found that higher levels of sTNFR-1 and sTNFR-2 were independently associated with smaller HV. Although prior studies have shown associations between CRP and IL-6 and dementia risk42, these markers were not associated with HV in our non-demented. The relationships between sTNFRs and HV varied by sex and age, but did not differ consistently by race. This study is the first to our knowledge to report a relationship between inflammation and HV in a non-demented community-based sample and to include AA. To put the magnitude of the association into context, each SD increase in sTNFR-1 and sTNFR-2 was associated with smaller hippocampi comparable to the effect of 1.7 and 1.5 years of aging, respectively.

Cell culture and animal studies have implicated TNFα in isolated features of AD9–11,43. Human studies have linked TNFα with increased dementia risk18,43–46 and reduced cognitive function6,47. In another population-based study of non-demented individuals, the Framingham Heart Study (FHS) reported an inverse association between sTNFR-2 and total brain volume19. Our study extends this work to the hippocampus and non-whites. The FHS also found an association between sTNFR-2 and cognitive function47. Similarly, we have previously reported a relationship between sTNFR-2 and performance across several cognitive domains in this same sample6. Taken together, these findings suggest that inflammation may have broad, non-specific, effects on brain structure, which may mediate the association between inflammation and cognitive function. Mediation analyses were beyond the scope of the current report but may be useful in further elucidating these relationships.

The CNS was once thought to be immune privileged, but molecules from the periphery can affect CNS function via the afferent vagus nerve, blood brain barrier (BBB) transport mechanisms22, or even passive diffusion through the BBB, which becomes more permeable with age23. sTNFRs have not been shown to cross the BBB, but their ligand, TNFα, is actively transported across it. Our study used measurements of soluble TNFα receptors which have been shown to be sensitive indicators of TNFα activity. Moreover, the relatively long half-life of the soluble receptors may provide a more accurate assessment of overall TNFα activity than actual TNFα levels captured at a single assessment34,48.

We did not find an association with CRP or IL-6. TNFα has been shown to trigger IL-6 release49, leading to an expectation of similar results for sTNFRs and IL-6. Both animal and human studies have suggested a negative relationship between IL-6 and hippocampal grey matter27, and both CRP18,44,50 and IL-613,42,44,50 have been associated with dementia. We cannot rule out that some characteristic of our sample (e.g., the high prevalence of hypertension) limited our ability to detect an association with these markers. However, sensitivity analyses excluding outliers, or adjusting for known confounders had little effect on the observed associations.

While we found some subgroup differences in relationships between HV and individual inflammatory markers across gender (stronger sTNFR-2 effects in males) and age (stronger sTNFR-1/sTNFR-2 effects for 60–70 year olds), none were consistently observed across the biomarkers we examined. We acknowledge the need for replication of these findings in other settings prior to inferring meaning or implications of the few supported interactions that we observed.

Strengths of this study include a relatively large community-dwelling sample including a wide age range of women and AA participants with carefully measured independent, dependent and confounding variables, thus reducing many sources of bias commonly encountered in clinical populations. Some limitations are also noted. We are unable to exclude the possibility that some participants had acute inflammation at the time of the blood draw. The observational nature of this cross-sectional study precludes an interpretation of causality. Although the findings are consistent with previous reports, a number of models were examined raising the possibility of false positives. These findings should be considered hypothesis-generating and will require replication in independent samples.

The hippocampus declines in volume with age and is one of the earliest structures affected in various types of dementia, particularly AD. Whether inflammation has a causative deleterious effect on brain structure and subsequent cognitive function, or rather is a consequence (e.g., a protective response) of underlying pathology is unknown. Longitudinal data are needed to determine whether TNFα may help to identify those at increased risk of late life cognitive impairment and dementia.

Acknowledgments

Study funding: supported by NIH (R01-NS041558, U01-HL081331, U01-HL054464, M01-RR000585)

This work was supported by NIH grants (R01-NS041558, U01-HL081331, U01-HL054464, M01-RR000585)

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Schmidt MF, Freeman KB, Windham BG, Griswold ME, Kullo IJ, Turner ST, Mosley TH report no disclosures.

Author contributions: Concept and design: MFS, MEG, THM

Acquisition of subjects and data: MFS, KBF, STT, IJK, THM

Analysis and interpretation of data: MFS, MEG, THM

Preparation of manuscript: MFS, KBF, BGW, MEG, THM

Statistical analyses were performed by Mike F Schmidt (Graduate student, Program in Neuroscience at University of Mississippi Medical Center) with guidance, selection of statistical methods, and review of results from Michael E Griswold, PhD (Professor and Director of The Center of Biostatistics at University of Mississippi Medical Center) and Thomas H Mosley Jr, PhD (Professor and Director of The MIND Center at University of Mississippi Medical Center) All authors contributed significantly to the work in concept, design, data analysis/interpretation or preparation of the manuscript, have made critical reviews and revisions of the manuscript and have given consent for publication.

Sponsor’s role: Sponsor played no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, analysis, or preparation of paper.

References

- 1.Krabbe KS, Pedersen M, Bruunsgaard H. Inflammatory mediators in the elderly. Exp Gerontol. 2004;39:687–699. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Godbout JP, Johnson RW. Interleukin-6 in the aging brain. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;147:141–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2003.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yaffe K, Lindquist K, Penninx BW, et al. Inflammatory markers and cognition in well-functioning African-American and white elders. Neurology. 2003;61:76–80. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000073620.42047.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weaver JD, Huang M-H, Albert M, et al. Interleukin-6 and risk of cognitive decline: MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging. Neurology. 2002;59:371–378. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.3.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wright CB, Sacco RL, Rundek TR, et al. Interleukin-6 is associated with cognitive function: The Northern Manhattan Study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2006;15:34–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Windham BG, Simpson BN, Lirette S, et al. Associations between inflammation and cognitive function in African Americans and European Americans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:2303–2310. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teunissen CE, van Boxtel MPJ, Bosma H, et al. Inflammation markers in relation to cognition in a healthy aging population. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;134:142–150. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(02)00398-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McAfoose J, Baune BT. Evidence for a cytokine model of cognitive function. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009;33:355–366. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akiyama H, Barger S, Barnum S, et al. Inflammation and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21:383–421. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00124-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wyss-Coray T, Rogers J. Inflammation in Alzheimer disease: A brief review of the basic science and clinical literature. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2:a006346. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGeer PL, McGeer EG. The amyloid cascade-inflammatory hypothesis of Alzheimer disease: Implications for therapy. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126:479–497. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1177-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teunissen CE, de Vente J, Steinbusch HWM, et al. Biochemical markers related to Alzheimer’s dementia in serum and cerebrospinal fluid. Neurobiol Aging. 2002;23:485–508. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00328-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swardfager W, Lanctôt K, Rothenburg L, et al. A meta-analysis of cytokines in Alzheimer’s disease. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68:930–941. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kálmán J, Juhász A, Laird G, et al. Serum interleukin-6 levels correlate with the severity of dementia in Down syndrome and in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neurol Scand. 1997;96:236–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1997.tb00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh VK, Guthikonda P. Circulating cytokines in Alzheimer’s disease. J Psychiatr Res. 1997;31:657–660. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(97)00023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Licastro F, Candore G, Lio D, et al. Innate immunity and inflammation in ageing: A key for understanding age-related diseases. Immun Ageing. 2005;2:8. doi: 10.1186/1742-4933-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strandberg TE, Tilvis RS. C-reactive protein, cardiovascular risk factors, and mortality in a prospective study in the elderly. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:1057–1060. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.4.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmidt R, Schmidt H, Curb JD, et al. Early inflammation and dementia: A 25-year follow-up of the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:168–174. doi: 10.1002/ana.10265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jefferson AL, Massaro JM, Wolf PA, et al. Inflammatory biomarkers are associated with total brain volume: The Framingham Heart Study. Neurology. 2007;68:1032–1038. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000257815.20548.df. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schram MT, Euser SM, de Craen AJM, et al. Systemic markers of inflammation and cognitive decline in old age. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:708–716. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gimeno D, Marmot MG, Singh-Manoux A. Inflammatory markers and cognitive function in middle-aged adults: The Whitehall II study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33:1322–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zlokovic BV. The blood-brain barrier in health and chronic neurodegenerative disorders. Neuron. 2008;57:178–201. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montagne A, Barnes SR, Sweeney MD, et al. Blood-brain barrier breakdown in the aging human hippocampus. Neuron. 2015;85:296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Squire LR, Stark CEL, Clark RE. The medial temporal lobe. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:279–306. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raz N, Rodrigue KM. Differential aging of the brain: Patterns, cognitive correlates and modifiers. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30:730–748. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raz N, Lindenberger U, Rodrigue KM, et al. Regional brain changes in aging healthy adults: General trends, individual differences and modifiers. Cereb Cortex. 2005;15:1676–1689. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marsland AL, Gianaros PJ, Abramowitch SM, et al. Interleukin-6 covaries inversely with hippocampal grey matter volume in middle-aged adults. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:484–490. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim CX, Bailey KR, Klee GG, et al. Sex and ethnic differences in 47 candidate proteomic markers of cardiovascular disease: The Mayo Clinic Proteomic Markers of Arteriosclerosis Study. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9065. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang MX, Stern Y, Marder K, et al. The APOE-e4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer disease among African Americans, whites, and Hispanics. JAMA. 1998;279:751–755. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.10.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Green RC, Cupples LA, Go R, et al. Risk of dementia among white and African American relatives of patients with Alzheimer disease. JAMA. 2002;287:329–336. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.3.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Investigators TF. Multi-center genetic study of hypertension: The Family Blood Pressure Program (FBPP) Hypertension. 2002;39:3–9. doi: 10.1161/hy1201.100415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Investigators A. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study: Design and objectives. The ARIC investigators. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129:687–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Melton LJ. History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:266–274. doi: 10.4065/71.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aderka D, Sorkine P, Abu-Abid S, et al. Shedding kinetics of soluble tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptors after systemic TNF leaking during isolated limb perfusion. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:650–659. doi: 10.1172/JCI694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ellington AA, Kullo IJ, Bailey KR, et al. Measurement and quality control issues in multiplex protein assays: A case study. Clin Chem. 2009;55:1092–1099. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.120717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knopman DS, Mosley TH, Bailey KR, et al. Associations of microalbuminuria with brain atrophy and white matter hyperintensities in hypertensive sibships. J Neurol Sci. 2008;271:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jack CR, O’Brien PC, Rettman DW, et al. FLAIR histogram segmentation for measurement of leukoaraiosis volume. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2001;14:668–676. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. [Accessed January 21, 2016];Freesurfer, RRID:SCR_001847. Available at: http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/

- 39.Fischl B, Salat DH, Busa E, et al. Whole brain segmentation: Automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron. 2002;33:341–355. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fischl B. FreeSurfer. Neuroimage. 2012;62:774–781. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stata. [Accessed January 21, 2016];RRID:SCR_012763. Available at: http://www.stata.com.

- 42.Koyama A, O’Brien J, Weuve J, et al. The role of peripheral inflammatory markers in dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: A meta-analysis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68:433–440. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McCusker SM, Curran MD, Dynan KB, et al. Association between polymorphism in regulatory region of gene encoding tumour necrosis factor alpha and risk of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia: A case-control study. Lancet. 2001;357:436–439. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tan ZS, Beiser AS, Vasan RS, et al. Inflammatory markers and the risk of Alzheimer disease: The Framingham Study. Neurology. 2007;68:1902–1908. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000263217.36439.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sundelöf J, Kilander L, Helmersson J, et al. Systemic inflammation and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia: A prospective population-based study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;18:79–87. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tarkowski E, Blennow K, Wallin A, et al. Intracerebral production of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, a local neuroprotective agent, in Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia. J Clin Immunol. 1999;19:223–230. doi: 10.1023/a:1020568013953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jefferson AL, Massaro JM, Beiser AS, et al. Inflammatory markers and neuropsychological functioning: The Framingham Heart Study. Neuroepidemiology. 2011;37:21–30. doi: 10.1159/000328864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aderka D, Engelmann H, Shemer-Avni Y, et al. Variation in serum levels of the soluble TNF receptors among healthy individuals. Lymphokine Cytokine Res. 1992;11:157–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tilg H, Trehu E, Atkins MB, et al. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) as an anti-inflammatory cytokine: Induction of circulating IL-1 receptor antagonist and soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor p55. Blood. 1994;83:113–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Engelhart MJ, Geerlings MI, Meijer J, et al. Inflammatory proteins in plasma and the risk of dementia: The Rotterdam Study. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:668–672. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.5.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]