Abstract

Background

Individuals with schizophrenia exhibit marked and disproportional impairment in social cognition, which is associated with their level of community functioning. However, it is unclear whether social cognitive impairment is stable over time, or if impairment worsens as a function of illness chronicity. Moreover, little is known about the longitudinal associations between social cognition and community functioning.

Method

Forty-one outpatients with schizophrenia completed tests of emotion processing (Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test, MSCEIT) and social perception (Relationships Across Domains, RAD) at baseline and approximately five years later. Stability of performance was assessed using paired t-tests and correlations. Longitudinal associations between social cognition and community functioning (Role Functioning Scale, RFS) were assessed using cross-lagged panel correlation analysis.

Results

Performance on the two social cognition tasks were stable over follow-up. There were no significant mean differences between assessment points [p's≥0.20, Cohen's d's≤|0.20|], and baseline performance was highly correlated with performance at follow-up [ρ's≥0.70, ICC≥0.83, p's<0.001]. The contemporaneous association between social cognition and community functioning was moderately large at follow-up [ρ=0.49, p=.002]. However, baseline social cognition did not show a significant longitudinal influence on follow-up community functioning [z=0.31, p=0.76].

Conclusions

These data support trait-like stability of selected areas of social cognition in schizophrenia. Cross-lagged correlations did not reveal a significant unidirectional influence of baseline social cognition on community functioning five years later. However, consistent with the larger literature, a moderately large cross-sectional association between social cognition and community functioning was observed. Based on stability and cross-sectional associations, these results suggest that social cognition might have short-term implications for functional outcome rather than long-term consequences.

Keywords: MSCEIT, RAD, cross-lagged panel analyses, psychosis, illness duration, social cognition

1. Introduction

Social cognition refers to the mental operations that underlie social interactions (Green et al., 2008), and includes domains such as emotion processing, social perception, and theory of mind (Pinkham et al., 2014). Individuals with schizophrenia exhibit marked and disproportional impairments in social cognition (Lee et al., 2013; Savla et al., 2013) which are strongly associated with their community functioning (Fett et al., 2011). Social cognition is considered to be a promising endophenotype for schizophrenia because impairments are evident early in illness, present during symptomatic remission, heritable, and present in milder form in first degree relatives (Comparelli et al., 2013; Green et al., 2015, 2012a; Lavoie et al., 2013; Yalcin-Siedentopf et al., 2014). However, it is unclear whether social cognitive impairment is stable over time, or if impairment worsens as a function of illness chronicity. Moreover, while strong cross-sectional associations between social cognition and community functioning have been reported in patients, little is known about the longitudinal associations between these two constructs.

The focus of this dataset is on two social cognition constructs: emotion processing and social perception. Emotion processing refers to perception and utilization of emotions, and it is typically assessed using tasks that require identification of emotional states based on facial expression (i.e., facial affect identification), tone of voice (i.e., affective prosody identification), evocative images, and tasks assessing emotion regulation and utilization skills (Pinkham et al., 2014). Social perception refers to identifying and utilizing social cues to make judgments about social roles, rules, relationships, context, and the characteristics of others. It is assessed with tasks that require inferences to be made about the nature of relationships between people, or to make judgments about ambiguous social situations (Pinkham et al., 2014). Individuals with schizophrenia exhibit marked performance deficits on tasks of emotion processing and social perception (Hedges' g≥0.88) (Savla et al., 2013). Moreover, a meta-analysis reported that social cognition explains 16% of the variance in the community functioning of patients (Fett et al., 2011); hence, it is a prime target for intervention.

Long-term follow-up studies of non-social cognition (“neurocognition”) suggest stability of impairments rather than progressive decline (Bonner-Jackson et al., 2010; Rund et al., 2016), at least until later in adult life (Friedman et al., 2001). Significant associations between baseline non-social cognition and later community functioning have been reported for follow-up periods ranging from several months to several years (Green et al., 2004; Kurtz et al., 2005; Milev et al., 2005). However, few studies have examined the stability of social cognitive impairment and its potential long-term associations with community functioning in schizophrenia. Cross-sectional studies that compare individuals at different phases of illness (i.e., recent-onset and chronic phase patients) have yielded mixed findings, with some supporting stability of social cognitive impairment (Green et al., 2012a; Pinkham et al., 2007), and others suggesting progressive impairment (Kucharska-Pietura et al., 2005). Some meta-analytic studies of social cognition in schizophrenia have considered whether illness duration is correlated with social cognition impairment severity, which would be expected if social cognition progressively declined. The results have been inconsistent. A meta-analyses have found longer illness duration to be associated with poorer emotion processing performance (Savla et al., 2013), and another meta-analysis of facial emotion perception found a trend-level association between task performance and duration of illness (Chan et al., 2010). In contrast, other meta-analytic studies are not consistent with progressive decline. Meta-analyses of facial emotion identification, vocal prosody identification, and social perception found no moderating impact of illness duration on task performance (Hoekert et al., 2007; Kohler et al., 2010; Savla et al., 2013).

Clearly, longitudinal studies are needed to delineate trajectories and directly address questions about stability of social cognitive impairment and associations with community functioning over long-term follow-up. Two studies of emotion processing in schizophrenia provide evidence for stability of performance over 6- and 12-months (Addington et al., 2006; Hamm et al., 2012). Although a large study of facial affect identification over a three-year follow-up provided evidence for changes in emotion processing performance over time (Maat et al., 2015), the observed changes were associated with alterations in clinical status (i.e., transitioning from remitted to non-remitted state and vice versa) rather than with an increasing duration of illness. Previous work from our group demonstrated stability of emotion processing performance over 1-year follow-up in recent-onset schizophrenia, and also provided evidence for a cross-lagged relationship between baseline social cognitive abilities and community functioning one year later that is consistent with a causal influence (Horan et al., 2012). Similarly, in another large sample of outpatients with schizophrenia, baseline social cognition was shown to have a relationship with community functioning 12 months later that was consistent with a causal model (Hoe et al., 2012). Notably, the few existing longitudinal investigations tend to involve brief follow-up periods (e.g., 6–12 months). Follow-up over an extended time period would provide evidence about whether social cognitive performance is stable over the course of illness, including the period of transition from recent-onset to chronic phase.

The aims of this paper are to: 1) examine stability of performance in emotion processing and social perception over a 5-year follow-up, and 2) to test 5-year longitudinal associations between social cognition and community functioning. Based on the available evidence, we predicted that emotion processing and social perception would be stable over time. We also predicted that baseline social cognitive performance would be related to follow-up social cognitive performance and community functioning, and that baseline social cognitive performance would continue to exert a significant influence on community functioning at 5-year follow-up.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

A total of 41 patient participants were recruited from the Center for Neurocognition and Emotion in Schizophrenia at UCLA. Informed consent was obtained from all participants using methods approved by the UCLA Institutional Review Board. Inclusion criteria were: 1) a DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) diagnosis of schizophreniform disorder, schizophrenia, or schizoaffective disorder, depressed subtype based on SCID-I/P interview (First and Gibbon, 2004) at baseline, 2) age 18–55 years, and 3) clinical stability, as indicated by stable outpatient status and no antipsychotic medication changes in the month prior to testing. Exclusion criteria were: 1) evidence of a neurological disorder or head injury, and 2) current substance or alcohol abuse or dependence.

Participants were assessed at baseline and approximately 5 years later (mean duration between assessments=5.4 years, s.d.=1.4 years). At the baseline assessment, 29 participants were considered to be recent-onset patients, i.e., within two years of psychosis onset (mean=22 weeks, s.d.=21 weeks), and were receiving oral risperidone monotherapy. Some of these patients also participated in a 12-month psychosocial intervention following the baseline assessment focusing on either cognitive training (non-social cognition) or healthy lifestyle behavior training (Gretchen-Doorly et al., 2009; Nuechterlein et al., 2014). The remaining 12 participants were in the chronic phase of illness (i.e., a minimum of five years since illness onset; mean duration of illness=10.4 years, s.d.=6.8 years). These participants were prescribed clinically-determined antipsychotic medications by their community-based outpatient psychiatrist and did not participate in the psychosocial interventions described above. A subset of the participants in the current analyses also provided data for papers that examined 1-year follow up of recent-onset patients (Horan et al., 2012) and compared performance cross-sectionally across illness phases (Green et al., 2012a).

Psychiatric symptoms were assessed by trained raters with the 24-item Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (Ventura, Green, Shaner, & Liberman, 1993). Each clinical rater achieved a median Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) of 0.80 or higher across all BPRS and RFS items compared with the criterion ratings and participated in a quality assurance program (Ventura et al., 1993). For the SCID, clinical raters demonstrated an overall kappa coefficient, kappa sensitivity, and kappa specificity of 0.75 or greater, and a diagnostic accuracy kappa coefficient of 0.85 or greater. Additional demographic information about the sample can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and descriptive data (n=41).

| n (%) | mean (s.d.) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (male) | 26 (63.4) | -- |

| Race and Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 12 (29.3) | -- |

| Caucasian | 8 (19.5) | -- |

| More than one race | 4 (9.8) | -- |

| Non-Hispanic | 29 (70.7) | -- |

| African American | 13 (31.7) | -- |

| Asian | 4 (9.8) | -- |

| Caucasian | 8 (19.5) | -- |

| Pacific Islander | 2 (4.9) | -- |

| More than one race | 2 (4.9) | -- |

| Diagnosis at follow-up | ||

| Schizophrenia | 35 (85.4) | -- |

| Schizoaffective Disorder (depressed type) | 5 (12.2) | -- |

| Schizophreniform Disorder | 1 (2.4) | |

| Age at follow-up | -- | 31.06 (7.43) |

| Duration of illness at follow-up | -- | 8.90 (5.24) |

| BPRS total score at baseline | -- | 37.41 (8.00) |

| BPRS total score at follow-up | -- | 41.05 (8.75) |

| Personal Education | -- | 13.46 (1.75) |

| Highest Parental Education | -- | 14.51 (3.43) |

Note: BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Emotion Processing

The Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT) (Mayer et al., 2003) is a self-report measure consisting of 141 items that assess 4 branches of emotion processing. Branch 1 “Identifying Emotions” measures perception of emotion in faces and pictures, branch 2 “Using Emotions” examines how mood enhances cognition, and which emotions are associated with particular sensations, branch 3 “Understanding Emotions” assesses the ability to comprehend emotional blends and transitions between emotions, and branch 4 “Managing Emotions” examines emotion regulation in oneself and in one's relationships with others. For the current study, we examined the MSCEIT total score using the general consensus scoring approach, which yields a standard score based on a large normative sample of healthy adults (e.g., a standard score of 100 corresponds to the 50%ile). Good internal consistency has been reported for the MSCEIT with schizophrenia patients (Cronbach's α=0.78 to 91 for branch scores, Cronbach's α=0.91 for MSCEIT total score) (Eack et al., 2010). Good test-retest reliability over a four-week period has been reported for MSCEIT branches 1 and 4 (ICC=0.73 to 0.80), and there were no significant practice effects (Nuechterlein et al., 2008). Similarly, the previous study from our group demonstrated good stability over a 12-month period for MSCEIT total score (r=0.87), with a negligible change in mean score at 12 months (mean difference=-1.14, n.s., Cohen's d=0.16) (Horan et al., 2012).

2.2.2. Social Perception

The Relationships Across Domains test (RAD) (Sergi et al., 2009) is a 75-item paper and pencil measure of competence in relationship perception that is based on relational models theory (Fiske, 1992). Participants are presented with 25 brief written vignettes about different male-female dyad interactions. Each vignette is followed by three statements that require utilization of implicit knowledge about relational models to make inferences about how the social partners will behave in future interactions. For each statement, participants are asked to use a “yes” or “no” response to indicate the likelihood that the behaviors described will occur during a future interaction between the dyad. The number of correct responses are computed to yield a total score (maximum=75). Good internal consistency for the RAD has been demonstrated with a schizophrenia sample (Cronbach's α=0.85) (Sergi et al., 2009). Test-retest reliability on an abbreviated version of the RAD was good over a two-week period (r=0.75), although there was evidence for a small practice effect (Cohen's d=0.26) (Pinkham et al., 2016). Similarly, the previous study from our group demonstrated good stability over a 12-month period for the full version of the RAD (r=0.74), with a small-to-medium change in mean score at 12 months (mean difference=2.42, p<0.05, Cohen's d=0.34) (Horan et al., 2012)

2.2.3. Community functioning

Community functioning was assessed with the Role Functioning Scale (RFS) (Goodman et al., 1993). Trained raters assign scores for four subscales (work, independent living, family relations, and social functioning) based on a semi-structured interview with the participant. Ratings for each subscale range from 1 (severely impaired functioning) to 7 (optimal functioning). Anchors describe the quality and quantity of functioning for each point. For the current study, the variable of interest was the sum of the four RFS subscale scores (maximum=28).

2.3. Data Analysis

Stability of performance on the social cognition tests over follow-up was examined using paired t-tests, bivariate correlations (Spearman's ρ) and intra-class correlations (ICC) (Shrout and Fleiss, 1979). Longitudinal associations between social cognition and community functioning were assessed using cross-lagged panel correlation analysis. A cross-lagged panel correlation design permits examination of whether relationships are consistent with possible causal influence of one variable on another variable over time, while considering their relationship at an earlier assessment point and possible spurious longitudinal associations attributable to an unmeasured third variable (Kenny, 1975). To reduce the number of analyses, and to remain consistent with the previous paper from our group, we followed the method of Horan et al. (2012) to calculate a composite social cognition score from the emotion processing and social relationship perception data. Standard scores (z) for the MSCEIT and RAD were computed for each participant based on normative data from a sample (n=125) of healthy comparison subjects; the mean of the two z scores yielded a social cognition composite score for each participant.

3. Results

MSCEIT total score was missing for one participant so this participant was excluded from analyses involving the MSCEIT. Descriptive statistics for the measures of social cognition and community functioning are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Social cognition and community functioning at each assessment point (n=41).

| Baseline mean (s.d.) | Follow-up mean (s.d.) | Mean difference (Follow-up -Baseline) (s.d.) | 95% CI | t (p-value) | Effect size Cohen's d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAD total | 50.51 (8.15) | 49.54 (9.36) | -0.98 (6.75) | -3.11, 1.15 | -0.93 (0.36) | -0.15 |

| MSCEIT total | 87.54 (16.30) | 89.75 (14.72) | 2.21 (10.72) | -1.21, 5.64 | 1.31 (0.20) | 0.20 |

| RFS total | 17.76 (5.42) | 18.13 (5.39) | 0.37 (5.75) | -1.52, 2.26 | 0.40 (0.70) | 0.06 |

| RFS Working Productivity | 3.37 (1.89) | 3.68 (2.09) | 0.32 (2.66) | -0.56, 1.19 | 0.73 (0.47) | 0.12 |

| RFS Independent Living | 4.24 (1.62) | 4.50 (1.35) | 0.26 (2.01) | -0.40, 0.92 | 0.81 (0.43) | 0.13 |

| RFS Family Network Relationships | 5.55 (1.20) | 5.39 (1.24) | -0.16 (1.17) | -0.54, 0.23 | -0.83 (0.41) | -0.14 |

| RFS Immediate Social Network Relationships | 4.61 (1.76) | 4.55 (1.88) | -0.05 (1.64) | -0.59, 0.49 | -0.20 (0.85) | -0.04 |

Note: RAD, Relationships Across Domains; MSCEIT, Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test; RFS, Role Functioning Scale.

3.1. Stability of Social Cognition Task Performance over 5-year Follow-up

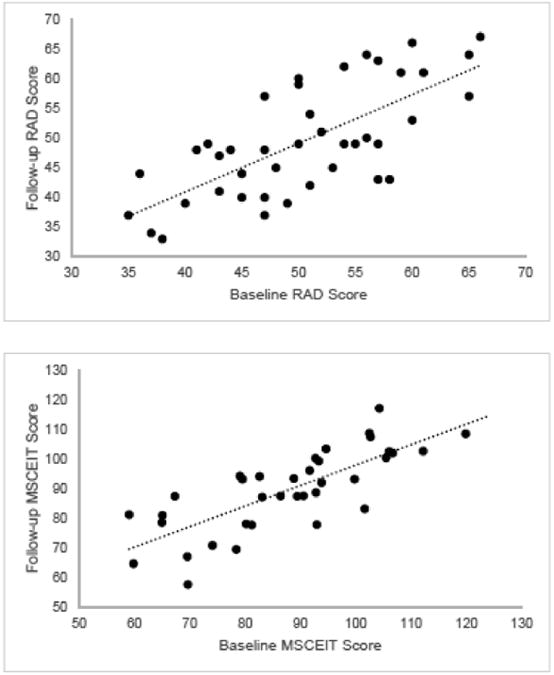

The difference in mean performance on the two social cognition tests between baseline and 5-year follow-up did not reach statistical significance, thus we cannot reject the null hypothesis of no difference between the two assessment points [tRAD(40)=-0.93, p=0.36; tMSCEIT(39)=1.31, p=0.20]. Scatterplots of RAD and MSCEIT total scores at baseline and follow-up are presented below in Figure 1. For both measures, total score at baseline was strongly correlated with total score at 5-year follow-up [ρRAD=0.70, 95%CI: 0.60, 0.87; ρMSCEIT=0.77, 95%CI: 0.51, 0.83; p's<0.001]. Intra-class correlations also indicated good reliability for the two tasks across the two assessment points [ICCRAD(2,41)=0.83, 95%CI: 0.68, 0.91; ICCMSCEIT(2,40)=0.86, 95%CI: 0.74, 0.93; p's<0.001].

Figure 1.

Scatterplots of social cognition task performance at baseline and follow-up assessments. a. RAD total score. b. MSCEIT total score.

Results from follow-up paired t-tests and correlation analyses including only the 29 participants who met criteria for recent-onset schizophrenia at the baseline assessment did not appreciably differ from those reported above for the entire sample (see Supplemental Material).

3.2. Longitudinal Associations Between Social Cognition and Community functioning

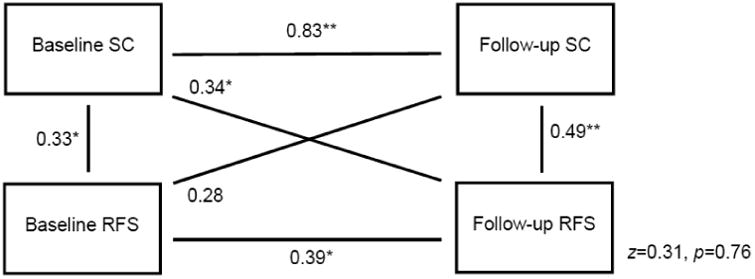

Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between social cognition and community functioning are presented in Figure 2. Moderate cross-sectional associations were observed between social cognition and community functioning at baseline [ρ=0.33, 95%CI: 0.03, 0.58, p=0.04] and at 5-year follow-up [ρ=0.49, 95%CI: 0.22, 0.69, p=0.002]. The strength of these cross-sectional associations did not significantly differ from each other [z=-0.85, p=0.40]. Community functioning at follow-up was associated with baseline community functioning, and with the social cognition composite score at baseline and follow-up [ρ's=0.34 to 0.49, p's<0.04]. However, the difference in cross correlations (i.e., social cognition at baseline – community functioning at 5 years vs. community functioning at baseline – social cognition at 5 years) was not statistically significant [z=0.31, p=0.76]. Results from follow-up cross-lagged panel correlation analyses for each of the four RFS subscales did not appreciably differ from the cross-lagged panel correlation analysis results for RFS total score (all z's≤0.78, all p's≥0.45). Thus, the cross-lagged panel correlation analyses were not consistent with the pattern expected if baseline social cognition had a statistically significant causal influence on community functioning 5 years later.

Figure 2.

Cross-lagged panel correlation analyses of longitudinal associations between social cognition and community functioning.

Note: *p<0.05, **p<0.01; RFS, Role Functioning Scale total score; SC, social cognition composite score

Subsequent analyses controlling for clinical symptoms (i.e., BPRS thinking disturbance, negative symptoms, or general psychopathology symptoms) yielded similar results (see Supplemental Material). Likewise, results from follow-up cross-lagged panel analyses for the MSCEIT and RAD individually showed a similar pattern of results (see Supplemental Material). In addition, results from follow-up cross-lagged panel correlation analyses including only the 29 participants who met criteria for recent-onset schizophrenia at the baseline assessment did not appreciably differ from those reported above for the entire sample (see Supplemental Material). Follow-up hierarchical linear regression analyses (Table 3) indicated that baseline social cognition did not provide significant incremental predictive validity for follow-up community functioning beyond that of baseline community functioning [ΔR2=0.04, ΔF=1.91, p=0.18].

Table 3.

Hierarchical linear regression analyses predicting follow-up community functioning score from baseline variables.

| Model | B (s.e.) | B | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Baseline RFS on follow-up RFS | ||||

| (Constant) | 10.48 (2.77) | -- | 3.78 | <0.001 |

| Block 1: Baseline RFS | 0.43 (0.15) | 0.43 | 2.88 | 0.007 |

| R2=0.19 | ||||

| F(1,36)=8.32, p=0.007 | ||||

|

| ||||

| 2. Baseline RFS and baseline SC on follow-up RFS | ||||

| (Constant) | 12.29 (3.03) | -- | 4.05 | <0.001 |

| Block 1: Baseline RFS | 0.38 (0.15) | 0.38 | 2.49 | 0.02 |

| Block 2: Baseline SC | 1.00 (0.72) | 0.21 | 1.38 | 0.18 |

| R2=0.23 | ||||

| F(2,35)=5.22, p=0.01 | ||||

| ΔR2=0.04 | ||||

| ΔF=1.91, p=0.18 | ||||

Note: RFS, Role Functioning Scale total score; SC, social cognition composite score

4. Discussion

In this study of long-term stability of social cognition in schizophrenia, performance on tests of emotion processing (the MSCEIT) and social perception (the RAD) were highly stable over a 5-year follow-up period in an outpatient sample of younger individuals with schizophrenia. Stability of performance was supported by: 1) the absence of significant changes in mean scores on each test between assessment points, and 2) by strong correlations between baseline and follow-up test performance. Supplementary analyses showed that these findings were consistent regardless of whether or not patients were in the early phase of schizophrenia at the baseline assessment. Thus, similar to the findings for non-social cognition, these longitudinal data support trait-like stability of social cognition in schizophrenia, and are not consistent with a progressive decline with increased illness chronicity. These results converge with earlier findings from our group indicating longitudinal stability of social cognition test performance over 12 months in recent-onset patients, as well as parallel severity of social cognition deficits across phases of illness (Green et al., 2012a; Horan et al., 2012).

The patients in this study did not receive any specialized interventions for social cognition over the follow-up period. Thus, in the absence of targeted intervention, social cognition does not significantly change over a five-year follow-up period. This stability of performance in the absence of a social cognitive intervention does not address the question of whether social cognitive impairments are amenable to training or treatment. Actually, there is a growing literature supporting the efficacy of social cognitive training interventions for schizophrenia (Kurtz and Richardson, 2012). There is some evidence for baseline non-social cognition to predict changes in community functioning following a cognitive intervention (Green et al., 2004). Whether baseline social cognition will show similar predictive power following social cognition training intervention is a question for future research.

Consistent with the larger literature (Fett et al., 2011), significant cross-sectional associations were found between social cognition and community functioning in this sample. Regarding longitudinal associations, previous findings from our group and others have demonstrated that baseline social cognition performance significantly predicts aspects of community functioning one year later (Hoe et al., 2012; Horan et al., 2012). However, the data reported here suggest that the predictive power of baseline social cognition for later community functioning becomes attenuated over longer follow-up periods. Although mean scores for community functioning did not differ between baseline and follow-up, the medium-sized correlation between the two variables indicates that the rank order of patients differed across the assessment points. Social cognition is one of many important determinants of community functioning, including perceptual processing, non-social cognition, clinical symptoms, motivation, and defeatist beliefs (Green et al., 2012b). Further research is needed to better understand these other determinants of community functioning and their contribution to functional stability.

The current study sample included a large proportion of individuals who were in the early phase of schizophrenia at baseline. Thus, a subset of patients had a shorter duration of illness than is typical for many published studies of social cognition in schizophrenia, which have tended to focus on patients with chronic illness. Although we found evidence for stability of social cognitive performance in this sample, it is possible that decline in social cognition performance may occur at a much later stage of illness. This factor may help explain the mixed findings regarding illness duration on social cognition in meta-analytic studies; inconsistent results may be partly attributable to differences in the proportion of patients with a chronic illness. Extended longitudinal studies are needed to address this question. This study is limited by its small sample size, which reduced statistical power to detect small differences in the cross correlations. Another limitation is that the assessment of social cognition in this study was limited to the domains of emotion processing and social perception. Future studies should test whether other aspects of social cognition (e.g., theory of mind) also exhibit long-term stability. This study is also limited by the absence of data regarding consistency of social cognitive performance over 5 years in healthy controls. Although good test-retest reliability over brief follow-up periods have been reported for healthy controls on the MSCEIT and RAD (Brackett and Mayer, 2003; Pinkham et al., 2016), data over longer follow-up periods are needed.

In summary, these data indicate that two areas of social cognition, emotion processing and social perception, are quite stable over a 5-year follow-up in schizophrenia. Baseline social cognition level was significantly associated with 5-year community functioning, and the contemporaneous association between social cognition and community functioning at follow-up was moderate in size. However, we did not find a pattern of correlations of social cognition and community functioning over 5 years that would support a long-term causal influence. Thus, it is possible that baseline social cognition impacts the functional outcomes of patients in the short term, but its influence is attenuated over time.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients for their participation in this study. We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of the UCLA Aftercare Research Program research assistants Robin Kite, M.A., and Lilian Medina, B.A., and clinic staff Michael Boucher, M.D., Laurie Casaus, M.D., John Luo, M.D., Elizabeth Arreola, B.S., Fe Asuan, B.A., Kimberly Baldwin, M.F.T., Rosemary Collier, M.A., Nicole R. DeTore, M.A., Denise Gretchen-Doorly, Ph.D., Lissa Portillo, Yurika Sturdevant, Psy.D., and Luana Turner, Psy.D.

Role of Funding Source: A. McCleery is supported by an institutional fellowship from the National Institutes of Health (NIH; T32MH096682-03). Subject recruitment and data collection were supported by grants P50MH066286 and R01MH037705 from NIH (K.H. Nuechterlein, PI) and RIS-NAP-4009 from Janssen Scientific Affairs (K.H. Nuechterlein, PI).

K.L. Subotnik has served as a consultant to Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, has been on the speaker's bureau for Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc, and has received research support from Genentech, Inc, and Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC through grants to Drs. Nuechterlein and Ventura. J. Ventura has received funding from Brain Plasticity, Inc., Genentech, Inc., and Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. He has served as a consultant to Boehringer-Ingelheim, GmbH and Brain Plasticity, Inc. M.F. Green and K.H. Nuechterlein are officers within MATRICS Assessment, Inc., the publisher of the MCCB, but do not receive any financial remuneration for their respective roles. K.H. Nuechterlein has received unrelated research grants from Genentech (ML28264), Janssen Scientific Affairs (R092670SCH4005), and Posit Science (BPI-1000-11) and has been a consultant to Genentech, Janssen, Otsuka, and Takeda. M.F. Green has been a consultant to AbbVie, ACADIA, DSP, FORUM, and Takeda, and he is on the scientific advisory board of Mnemosyne. He has received research funds from Amgen and FORUM.

Footnotes

Contributors: M.F. Green, W.P. Horan, and K.H. Nuechterlein designed the study and wrote the protocol. A. McCleery managed the literature searches and analyses. A. McCleery and G.S. Hellemann undertook the statistical analysis, and A. McCleery wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest: A. McCleery, J. Lee, A. Fiske, L. Ghermezi, G.S. Hellemann, J.N. Hayata, W.P. Horan, K.S. Kee, R.S. Kern, B.J. Knowlton, and C.A. Sugar declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed (DSM-IV) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bonner-Jackson A, Grossman LS, Harrow M, Rosen C. Neurocognition in schizophrenia: a 20-year multi-follow-up of the course of processing speed and stored knowledge. Compr Psychiatry. 2010;51:471–9. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brackett MA, Mayer JD. Convergent, discriminant, and incremental validity of competing measures of emotional intelligence. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2003;29:1147–1158. doi: 10.1177/0146167203254596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan RCK, Li H, Cheung EFC, Gong QY. Impaired facial emotion perception in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2010;178:381–90. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comparelli A, Corigliano V, De Carolis A, Mancinelli I, Trovini G, Ottavi G, Dehning J, Tatarelli R, Brugnoli R, Girardi P. Emotion recognition impairment is present early and is stable throughout the course of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2013;143:65–9. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eack SM, Greeno CG, Pogue-Geile MF, Newhill CE, Hogarty GE, Keshavan MS. Assessing social-cognitive deficits in schizophrenia with the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:370–80. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fett AKJKJ, Viechtbauer W, Dominguez MG, de G, Penn DL, van Os J, Krabbendam L. The relationship between neurocognition and social cognition with functional outcomes in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First M, Gibbon M. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Disorders (SCID-II) 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Fiske AP. The four elementary forms of sociality: framework for a unified theory of social relations. Psychol Rev. 1992;99:689–723. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.99.4.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman JI, Harvey PD, Coleman T, Moriarty PJ, Bowie C, Parrella M, White L, Adler D, Davis KL. Six-year follow-up study of cognitive and functional status across the lifespan in schizophrenia: a comparison with Alzheimer's disease and normal aging. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1441–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.9.1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Sewell DR, Cooley EL, Leavitt N. Assessing levels of adaptive functioning: the Role Functioning Scale. Community Ment Health J. 1993;29:119–131. doi: 10.1007/BF00756338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MF, Bearden CE, Cannon TD, Fiske AP, Hellemann GS, Horan WP, Kee K, Kern RS, Lee J, Sergi MJ, Subotnik KL, Sugar CA, Ventura J, Yee CM, Nuechterlein KH. Social cognition in schizophrenia, Part 1: performance across phase of illness. Schizophr Bull. 2012a;38:854–64. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MF, Hellemann G, Horan WP, Lee J, Wynn JK. From perception to functional outcome in schizophrenia: modeling the role of ability and motivation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012b;69:1216–24. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MF, Horan WP, Lee J. Social cognition in schizophrenia. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16:620–631. doi: 10.1038/nrn4005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MF, Kern RS, Heaton RK. Longitudinal studies of cognition and functional outcome in schizophrenia: Implications for MATRICS. Schizophr Res. 2004;72:41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MF, Penn DL, Bentall R, Carpenter WT, Gaebel W, Gur RC, Kring AM, Park S, Silverstein SM, Heinssen R. Social cognition in schizophrenia: an NIMH workshop on definitions, assessment, and research opportunities. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:1211–20. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gretchen-Doorly D, Subotnik KL, Kite RE, Alarcon E, Nuechterlein KH. Development and Evaluation of a Health Promotion Group for Individuals with Severe Psychiatric Disabilities. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2009;33:56–59. doi: 10.2975/33.1.2009.56.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoe M, Nakagami E, Green MF, Brekke JS. The causal relationships between neurocognition, social cognition and functional outcome over time in schizophrenia: a latent difference score approach. Psychol Med. 2012;42:2287–99. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoekert M, Kahn RS, Pijnenborg M, Aleman A. Impaired recognition and expression of emotional prosody in schizophrenia: review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2007;96:135–45. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horan WP, Green MF, DeGroot M, Fiske A, Hellemann G, Kee K, Kern RS, Lee J, Sergi MJ, Subotnik KL, Sugar CA, Ventura J, Nuechterlein KH. Social cognition in schizophrenia, Part 2: 12-month stability and prediction of functional outcome in first-episode patients. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38:865–72. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA. Cross-lagged panel correlation: A test for spuriousness. Psychol Bull. 1975;82:887. [Google Scholar]

- Kohler CG, Walker JB, Martin EA, Healey KM, Moberg PJ. Facial emotion perception in schizophrenia: a meta-analytic review. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:1009–19. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucharska-Pietura K, David AS, Masiak M, Phillips ML. Perception of facial and vocal affect by people with schizophrenia in early and late stages of illness. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:523–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.6.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz MM, Moberg PJ, Ragland JD, Gur RC, Gur RE. Symptoms versus neurocognitive test performance as predictors of psychosocial status in schizophrenia: a 1-and 4-year prospective study. Schizophr Bull. 2005;31:167–74. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbi004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz MM, Richardson CL. Social cognitive training for schizophrenia: a meta-analytic investigation of controlled research. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38:1092–104. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie MA, Plana I, Bédard Lacroix J, Godmaire-Duhaime F, Jackson PL, Achim AM. Social cognition in first-degree relatives of people with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2013;209:129–35. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Altshuler L, Glahn DC, Miklowitz DJ, Ochsner K, Green MF. Social and nonsocial cognition in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: relative levels of impairment. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:334–41. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12040490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer JD, Salovey P, Caruso DR, Sitarenios G. Measuring emotional intelligence with the MSCEIT V2.0. Emotion. 2003;3:97. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.3.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milev P, Ho BC, Arndt S, Andreasen NC. Predictive values of neurocognition and negative symptoms on functional outcome in schizophrenia: A longitudinal first-episode study with 7-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:495–506. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuechterlein KH, Green MF, Kern RS, Baade LE, Barch DM, Cohen JD, Essock S, Fenton WS, Frese FJ, Gold JM, Goldberg T, Heaton RK, Keefe RSE, Kraemer H, Mesholam-Gately R, Seidman LJ, Stover E, Weinberger DR, Young AS, Zalcman S, Marder SR. The MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery, part 1: test selection, reliability, and validity. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:203–13. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07010042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuechterlein KH, Ventura J, Subotnik KL, Hayata JN, Medalia A, Bell MD. Developing a Cognitive Training Strategy for First-Episode Schizophrenia: Integrating Bottom-Up and Top-Down Approaches. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil. 2014;17:225–253. doi: 10.1080/15487768.2014.935674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkham AE, Penn DL, Green MF, Buck B, Healey K, Harvey PD. The social cognition psychometric evaluation study: results of the expert survey and RAND panel. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40:813–23. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkham AE, Penn DL, Green MF, Harvey PD. Social Cognition Psychometric Evaluation: Results of the Initial Psychometric Study. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42:494–504. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbv056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkham AE, Penn DL, Perkins DO, Graham KA, Siegel M. Emotion perception and social skill over the course of psychosis: a comparison of individuals “at-risk” for psychosis and individuals with early and chronic schizophrenia spectrum illness. Cogn Neuropsychiatry. 2007;12:198–212. doi: 10.1080/13546800600985557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rund BR, Barder HE, Evensen J, Haahr U, Hegelstad WTV, Joa I, Johannessen JO, Langeveld J, Larsen TK, Melle I, Opjordsmoen S, Røssberg JI, Simonsen E, Sundet K, Vaglum P, McGlashan T, Friis S. Neurocognition and Duration of Psychosis: A 10-year Follow-up of First-Episode Patients. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42:87–95. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbv083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savla GN, Vella L, Armstrong CC, Penn DL, Twamley EW. Deficits in domains of social cognition in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of the empirical evidence. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39:979–92. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergi MJ, Fiske AP, Horan WP, Kern RS, Kee KS, Subotnik KL, Nuechterlein KH, Green MF. Development of a measure of relationship perception in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2009;166:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979;86:420–8. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura J, Green MF, Shaner A, Liberman RP. Training and quality assurance with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale: “The drift busters”. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 1993;3:221–244. [Google Scholar]

- Yalcin-Siedentopf N, Hoertnagl CM, Biedermann F, Baumgartner S, Deisenhammer EA, Hausmann A, Kaufmann A, Kemmler G, Mühlbacher M, Rauch AS, Fleischhacker WW, Hofer A. Facial affect recognition in symptomatically remitted patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophr Res. 2014;152:440–5. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.