Abstract

To elucidate how obsessional symptoms might develop or intensify in late-life, we tested a risk model. We posited that cognitive self-consciousness (CSC), a tendency to be aware of and monitor thinking, would increase reactivity to aging-related cognitive changes and mediate the relationship between cognitive functioning and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) symptoms. Older adults (Mage = 76.7 years) completed the Dementia Rating Scale-2 (DRS-2), a CSC measure, and an OCD symptom measure up to four times over 18 months. A model that included DRS-2 age and education adjusted total score as the indicator of cognitive functioning fit the data well, and CSC score change mediated the relationship between initial cognitive functioning and changes in OCD symptoms. In tests of a model that included DRS-2 Initiation/Perseveration (I/P) and Conceptualization subscale scores, the model again fit the data well. Conceptualization scores, but not I/P scores, were related to later OCD symptoms, and change in CSC scores again mediated the relationship. Lower scores on initial cognitive functioning measures predicted increases in CSC scores over time, which in turn predicted increases in OCD symptoms over the 18 months of the study. Implications for understanding late-life obsessional problems are discussed.

Keywords: older adults, obsessive-compulsive disorder, risk factors, cognitive functioning, cognitive self-consciousness

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is a commonly occurring psychiatric disorder characterized by recurrent intrusive thoughts, images, or impulses that increase distress (i.e., obsessions), and repetitive thoughts or actions intended to alleviate this distress (i.e., compulsions; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Although research on OCD has been prolific, research on OCD in older adults has been neglected (e.g., Calamari, Wilkes, & Prouvost, in press; Carmin, Calamari, & Ownby, 2012). Little is known about late-life OCD, including how to best treat older people with the disorder, which is problematic because OCD is associated with serious disability and distress across the lifespan (e.g., Steketee, 2012). Although estimates of the prevalence of OCD in older adults are lower than in other age groups in some epidemiologic studies (e.g., lifetime prevalence, 0.7%; Kessler et al., 2005), these estimates have several limitations including the exclusion of older adults living in supported environments such as nursing homes, where estimates of OCD have been much higher (see Carmin, et al., 2012, for a review).

There is growing recognition by gerontologists that the complex changes characteristic of late-life can influence adjustment broadly and affect the occurrence of late-life emotional disorders (e.g., Woods, 2008). Late-life adjustment is affected by significant stressors including important changes in older peoples’ social support (e.g., the passing of friends or the loss of one's spouse) and by increasing health problems (e.g., Calamari et al., in press). Significant changes in cognitive functioning characterize even normal aging (e.g., Salthouse, 2010), and although there are multiple factors related to cognitive decline, there is an established association between anxiety (see Beaudreau, & O'Hara, 2008, for a review) and depression (e.g., Bielak, Gerstorf, Anstey, & Luszcz, 2011), however, the causes of this relationship are not well understood (e.g., Beaudreau, & O'Hara, 2008; Woods, 2008). Most often, the associations between mood, anxiety, and cognitive functioning have been evaluated from the perspective that chronic mood or anxiety symptoms or disorders result in later, more significant declines in cognitive functioning, while few investigators have longitudinally evaluated how cognitive functioning might affect the trajectory of anxiety, mood, or other disorders symptoms (e.g., Salthouse, 2012). In the present study, we evaluated how developmental stage related changes in cognitive functioning might affect the development of obsessional symptoms in late-life. Calamari, Janeck, and Deer (2002) hypothesized that older adults’ concerns about changes in cognitive functioning and related vigilance about their cognitive abilities might influence reactivity to aspects of cognition including their reactions to common negative intrusive thoughts.

The etiology of OCD is not known, but neurobiological models posit that the neuropathology reliably associated with the condition plays a causative role. Condition-related neuropathology includes abnormal functioning of frontal–striatal circuits involving the orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, thalamus, and caudate (Baxter et al., 1992; Breiter et al., 1996; Rauch et al., 1994; Saxena & Rauch, 2000). The dearth of research on older adults with OCD precludes any conclusions as to whether the neuropathology underlying late-life OCD is different, although the results of several investigations suggest that the same underlying abnormalities might be involved (Henin et al., 2001; Roth, Milovan, Baribeau, & O'Connor, 2005; Taylor, 2011).

Although neurobiological models of OCD place different emphases on the affected neurologic systems and the system related functional abnormalities, Rauch and Savage's (2000) model focused on resultant excessive effortful, conscious processing. Rauch and Savage posited that the frontal-striatal hyperactivity that characterizes OCD results in a non-conscious processing gating disturbance such that innocuous stimuli, which are typically processed non-consciously and which do not elicit focused attention, are often processed consciously and inefficiently by people with OCD. An overly frequent shift to effortful, conscious processing is understood to be importantly related to many of the symptoms seen in OCD.

Cognitive theories of OCD emphasize the role of certain dysfunctional beliefs (e.g., responsibility; importance of thoughts), which are understood to drive the problematic appraisal of common negative intrusive thoughts (e.g., Frost & Steketee, 2002; Salkovskis, 1985). Although cognitive theories place different emphasis on the types of problematic beliefs most important to OCD, some theorists have focused on metacognitive processes. Wells (2000; 2009) emphasized specific aspects of metacognition as etiologic in mood, anxiety, and obsessional problems. In an evaluation of a measure of multiple metacognitive constructs, cognitive self-consciousness (CSC), an excessive awareness of and attention to thought experiences, was the only measure that differentiated OCD patients from patients with Generalized Anxiety Disorder (Cartwright-Hatton & Wells, 1997).

In evaluations of the CSC construct that followed, individuals with structured clinical interview diagnosed OCD scored higher on a measure of CSC compared to both clinical and nonclinical controls (e.g., Goldman et al., 2008; Janeck, Calamari, Riemann, & Heffelfinger, 2003). CSC measure scores correlated significantly with multiple OCD symptom measure scores in mixed clinical–nonclinical samples (r = .64) (Marker, Calamari, Woodard, & Riemann, 2006), in OCD and clinical comparison groups (r = .55 - .46) (Goldman et al., 2008) and in a nonclinical group (r = .45) (Cohen & Calamari, 2004). Further, CSC measure scores remained associated with OCD symptom scores even after controlling for general negative affect (Jacobi, Calamari, & Woodard, 2007), intrusive thought appraisals (Cohen & Calamari, 2004), worry (de Bruin, Muris, & Rassin, 2007), and OCD-related dysfunctional beliefs (Janeck et al., 2003), suggesting that CSC is a distinct OCD-related cognitive process. Additionally, Exner and colleagues demonstrated that CSC scores mediated the relationship between OCD and performance on object memory test (Exner et al., 2009) and selective attention evaluations (Koch & Exner, 2015), areas of cognitive functioning sometimes found impaired in OCD. As a result of the associations between CSC and OCD, Janeck et al. (2003) posited that elevated CSC might increase the detection of personally relevant negative intrusive thoughts, make their misappraisal more likely, and hinder the dismissability of these thoughts. Janeck et al. went on to theorize that CSC could be a cognitive risk factor for OCD, and noted that the construct shared similarities with the neuropathology-related dysfunction affecting cognitive processing in Rauch and Savage's (2000) model of OCD.

In several investigations, CSC has been directly linked to a behavioral marker of OCD neuropathology, implicit procedural learning, as measured by performance on the serial reaction time task (SRT; Nissen & Bullemer, 1987). Impaired performance on the SRT task was directly associated with the cortical-striatal dysfunction associated with OCD (e.g., Deckersbach et al., 2002). Further, Goldman et al. (2008) found that OCD patients’ performance was impaired in comparison to an anxious control group on the SRT, and that higher scores on a measure of CSC were related to longer reaction times (impaired performance). As a result of the potential importance of the CSC construct to cognitive and neurobiological theories of OCD, and as a result of the association between CSC and OCD-related cognitive functioning differences, we tested whether CSC might play an important role in late-life OCD.

There has been only one prior evaluation of a risk model of late-life obsessional problems. Using a cross sectional design, Teachman (2007) employed structural equation modeling to evaluate whether the relationship between OCD-related dysfunctional beliefs and OCD symptoms was mediated by a measure of subjective concerns about cognitive decline. As predicted, dysfunctional beliefs (e.g., over importance of thoughts; perceived need to control thoughts) was related to OCD symptoms through the mediator, concerns about cognitive functioning. She found that this mediational relationship was the same in the older and younger adult samples included in her study.

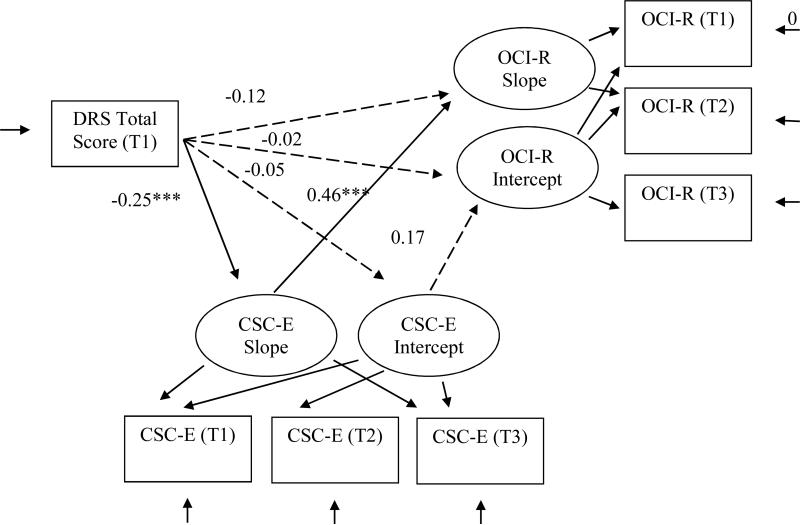

In the present study, we undertook a longitudinal evaluation of a risk model that included CSC as a mediational process or as a moderator. We tested whether CSC mediated the relationship between older adults’ cognitive functioning and the development of OCD symptoms (see Figures 1 & 2). We posited that late-life cognitive functioning changes, even changes that are within normal limits, would lead to a greater focus on cognitive processes and increasing CSC. Further, we predicted that increasing CSC would result in greater reactivity to personally relevant, negative intrusive thoughts and more OCD symptoms. Reactivity to negative intrusive thoughts is importantly related to OCD symptoms (e.g., Salkovskis, Richards, & Forrester, 1995). Additionally, CSC has been posited to be a relatively stable individual difference characteristic that might not directly influence OCD symptoms, but could interact with other variables to increase obsessional problems (Janeck et al., 2003). Therefore, we also tested for the presence of an interaction between our cognitive functioning predictor variables and the CSC mediator and the relationship to OCD symptoms. We also tested this relationship because predictor -mediator interactions will affect the estimation of mediational relationships (e.g., MacKinnon, 2008).

Figure 1.

Test of mediational Model 1, which examined the relationships between initial cognitive functioning and obsessive-compulsive disorder symptom development through cognitive self-consciousness as a mediational process. DRS-2 = Mattis Dementia Rating Scale 2 total scaled score; CSC-E = the Cognitive Self-Consciousness Scale-Expanded total score; OCI-R= the Obsessive Compulsive Inventory-Revised total score. T = assessment time, 1, 2, or 3. Standardized path coefficients (β) are shown.

* p ≤ .05 ** p ≤ .01 *** p ≤ .001

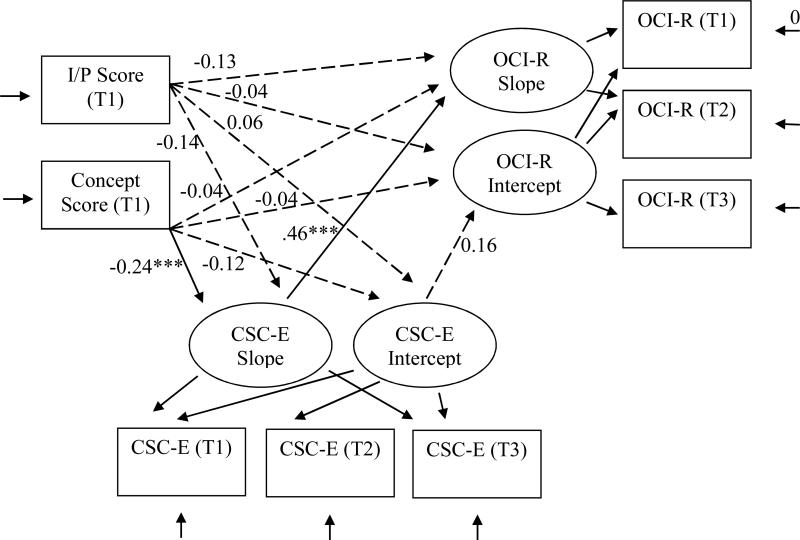

Figure 2.

Test of mediational Model 2, which examined the relationships between initial cognitive functioning on two DRS-2 subscales and obsessive-compulsive disorder symptom development through cognitive self-consciousness as a mediational process. DRS-2 = Mattis Dementia Rating Scale 2. I/P = Mattis Dementia Rating Scale 2 Initiation/Perseveration subscale scaled score at time 1; Conceptualization = Mattis Dementia Rating Scale 2 Conceptualization subscale scaled score at time 1; CSC-E = the Cognitive Self-Consciousness Scale-Expanded total score; OCI-R = the Obsessive Compulsive Inventory-Revised total score. T = assessment time, 1, 2, or 3. Standardized path coefficients (β) are shown.

* p ≤ .05 ** p ≤ .01 *** p ≤ .001

We tested whether a measure of global cognitive functioning or performance on measures of specific cognitive functions most sensitive to OCD-related neuropathology would affect OCD symptom levels though the CSC mediator, or interact with CSC, to predict later OCD symptoms. We predicted that that lower Dementia Rating Scale-2 (DRS-2; Jurica, Leitten, & Mattis, 2001) total scores, and lower scores on the DRS-2 Initiation-Perseveration (I/P) and Conceptualization subscales, which largely require executive functioning skills and frontal-striatal functioning (Judd, 2011; Nadler, Richardson, Malloy, Marran, & Hosteller Brinson, 1993) would lead to more OCD symptoms by increasing thought-focused attention (i.e., CSC). We evaluated scores on an established CSC measure as a mediator. Further, we predicted that if CSC scores interacted with measures of cognitive functioning, that lower cognitive functioning scores and higher CSC measure scores would be most strongly related to OCD symptom measure scores.

Method

Participants

Data were collected as part of larger longitudinal study examining risk factors for late-life anxiety disorders in older adults.1 Adults aged 65 years and older were recruited mainly from senior living centers and older adult social service programs in the Midwestern United States. A total of 204 older adults participated in the initial assessment (M age = 76.7 years, SD = 6.9 years; range, age 65-93). Individuals were excluded from analysis if they exhibited moderate or greater cognitive impairment, which was defined as an age- and education-adjusted total DRS-2 score below 5, which is a score 2 SD below the DRS-2 mean score. A cutoff score of 2 SD below the age-appropriate mean is a commonly used threshold of impaired performance on neuropsychological (Lezak et al., 2004) and intellectual functioning assessments (Wechsler, 2008). Cognitively impaired older adults were excluded because they would not be able to complete study measures in a meaningful way. The following numbers of participants were excluded at each time point because of impaired cognitive functioning: time 1 (T1), n = 1; T2, n = 6; T3, n = 3; T4, n = 1.

As shown in Table 1, participants were approximately 77 years old on average at each of the four assessments that occurred approximately every six months, and approximately 72% were women. Most participants who reported ethnicity indicated they were Caucasian (93.1%), although a small number of African Americans (3.5%) and Hispanics (.5%) participated in the study. Estimated income and education were higher for our sample in comparison to nationally representative older adult samples (e.g., Heeringa et al., 2009; Okura et al., 2010).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics and Descriptive Statistics for Measures

| Time 1 (0 months) | Time 2 (6 months) | Time 3 (12 months) | Time 4 (18 months) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | M (SD) | N | M (SD) | N | M (SD) | N | M (SD) | |

| Demographic | ||||||||

| Age | 202 | 76.8 (6.9) | 152 | 77.6 (6.8) | 114 | 77.9 (6.6) | 99 | 77.7 (6.6) |

| Percent female | 202 | 73% | 152 | 72% | 114 | 73% | 99 | 70% |

| Estimated Household Income a | 201 | $114,160 ($112,599) | 99 | $105,631 ($105,402) | ||||

| Measures | ||||||||

| DRS-2 | 201 | 11.3 (3.2) | 151 | 11.0 (2.9) | 113 | 12.1 (3.0) | 96 | 11.2 (2.2) |

| I/P | 201 | 10.7 (2.2) | 151 | 11.0 (2.4) | 113 | 10.7 (2.4) | 96 | 11.4 (1.9) |

| Conceptualization | 201 | 10.7 (2.6) | 151 | 9.76 (2.03) | 113 | 11.5 (2.1) | 96 | 9.8 (1.7) |

| CSC-E | 180 | 31.7 (9.16) | 150 | 29.3 (8.3) | 111 | 28.2 (7.3) | 98 | 29.1 (8.1) |

| OCI-R | 181 | 12.3 (9.3) | 151 | 10.3 (9.1) | 111 | 9.1 (7.6) | 98 | 10.2 (8.9) |

Note. DRS-2 = Mattis Dementia Rating Scale 2 total scaled score; I/P = Mattis Dementia Rating Scale 2 Initiation/Perseveration subscale scaled score; Conceptualization = Mattis Dementia Rating Scale 2 Conceptualization subscale scaled score; CSC-E = the Cognitive Self-Consciousness Scale-Expanded total score; OCI-R = the Obsessive Compulsive Inventory-Revised total score.

Income level was estimated using average tax return data reported by the Internal Revenue Service for zip codes.

Study attrition was significant but similar to other longitudinal studies with older adults (Chatfield, Brayne, & Matthews, 2005). At T2, 153 of the initial 202 cognitively intact participants completed assessments, and 147 scored above the DRS-2 cutoff. At T3, 114 of the original participants completed assessment, and 111 scored above the DRS-2 cutoff, while at T4, 97 participants completed assessments, and 96 scored above the DRS-2 cutoff. Several measure scores included in the larger study full assessment battery predicted completion of the study (i.e., all four assessments). Scoring on the Medical Outcomes Study – Short Form (SF-36; Ware, Snow, Kosinski, & Gandek, 1993) physical functioning subscale predicted completions status, Χ2(3, N = 179) = 19.202, p < .001 (Socha, Calamari, & Woodard, 2012). Participants with poorer health were more likely to drop out due to illness or death, Wald = 12.672, df = 1, p < .001; OR = .842. Age and Obsessive–Compulsive Inventory – Revised (OCI-R; Foa et al., 2002) scores were marginally related to completion status, age: Χ2(3, N = 179) = 7.55, p = .056; OCI-R: Χ2(3, N = 179) = 7.77, p = .051, respectively (Socha et al., 2012).

Measures

Dementia Rating Scale-2 (DRS-2)

The DRS-2 (Jurica, Leitten, & Mattis, 2001) assesses overall cognitive functioning as well as functioning in five specific domains: Attention, Initiation-Perseveration, Construction, Conceptualization, and Memory. The Attention subscale measures working memory (i.e., forward and backward digit span) and the ability to attend to and execute verbal and visual commands of varied complexity. The Initiation-Perseveration subscale assesses generative and perseverative verbal fluency, auditory articulation of vowel and consonant patterns, double alternating motor movements, and simple graphomotor skills. The Construction subscale measures the ability to copy simple visual designs, and to sign one's own name. The Conceptualization subscale assesses abstract concept formation skills and the ability to identify similarities and differences among sets of objects presented both visually and verbally. Lastly, the Memory subscale measures orientation (to time, day, date, and situation), recall of verbal information after a brief delay, and verbal and visual forced-choice recognition memory. Lower scores on each subscale indicate poorer functioning in that area. Overall cognitive functioning is represented as a composite of the five subscale scores. Age- and education-adjusted scaled total scores based on the Mayo Older American Normative Studies (Lucas, Ivnik, Smith, & Bohac, 1998) are available and range from 2–18, whereas the total raw score on the DRS-2 can range from 0–144. Subscale scores are also available in raw or scaled form. Scaled scores have a mean of 10 and a standard deviation of 3.

Scores from the DRS-2 have shown good psychometric properties in evaluations of older adults. One-week test-retest reliability coefficients for the total score and subscale scores in a sample of 30 patients with Alzheimer's disease ranged between .83 and .97 (Coblentz, 1973). Internal consistency reliability coefficients for DRS-2 scores have been reported for community dwelling patients with mild or moderate Alzheimer's disease and healthy controls and ranged between .75 and .95 (Vitaliano et al., 1984). 2 Good convergent and discriminant validity in healthy and cognitively impaired older adults has also been shown via moderate to strong correlations with other measures of cognitive functioning, including the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised and Wechsler Memory Scale (Jurica et al., 2001).

The DRS-2 measures overall cognitive functioning with an emphasis on frontal-lobe function (Goldman & Litvan, 2011) and memory. The emphasis on frontal lobe functioning makes it a good test to assess for relations between CSC and OCD as it is more likely to measure the functioning associated with areas of the brain thought to be dysfunctional in individuals with OCD. Additionally, the specific subscales of Initiation-Perseveration and Conceptualization have been linked to executive functioning, a functional domain that is associated with frontal-striatal dysfunction (Judd, 2011; Nadler et al, 1993; Mega & Cummings, 1994).

Cognitive Self Consciousness Scale-Expanded (CSC-E; Janeck et al. 2003).

The CSC-E measures the excessive focusing of attention on one's thoughts (e.g., “I monitor my thoughts”; “I notice my thoughts even when I am busy with another activity”; Janeck et al. 2003). The self-report measure is made up of seven original items from the CSC subscale of the Meta-Cognitions Questionnaire (Cartwright-Hatton & Wells, 1997) as well as seven additional items that were added by Janeck et al. Questions are rated on a four-point Likert scale, and scoring can range between 14 and 56. Higher scores are indicative of greater CSC. Scores from the CSC-E have shown good psychometric properties. Internal consistency for the CSC-E was high in prior studies (α = .94; Janeck et al., 2003). Internal consistency for the CSC-E in the current study at T1 was very good, α = .87.

Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory-Revised (OCI-R; Foa et al., 2002)

The OCI-R is an 18-item self-report measure that assesses OCD symptoms. The OCI-R has six subscales assessing different types of OCD symptoms: Washing, Checking, Ordering, Obsessing, Hoarding, and Neutralizing. OCI-R scores have good psychometric properties, including high internal consistency reliability (α = .90; Foa et al., 2002) and OCI-R scores are moderately correlated with scores on the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale clinical interview (Goodman et al., 1989; Foa et al., 2002), suggesting good convergent validity. Calamari et al. (2014) evaluated the OCI-R with participants aged 65 years and older and concluded that OCI-R scores effectively measure older adults’ OCD symptoms. Their results supported the previously identified latent structure of the OCI-R involving six OCD symptom subtypes, and total score and most subscale scores were reliable in evaluations of both internal consistency and across time stability. Initial OCI-R total score correlated with OCD symptom severity assessed 18 months later by structured clinical interview. Evaluation of the internal consistency with the current study sample at T1 indicate reliability was very good, α = .87.

Procedure

All data were collected as a part of a larger longitudinal study. Approximately two weeks before completing a clinical evaluation, participants were mailed an informed consent document and study self-report measures and were asked to have completed these measures at the time of their clinical evaluation. After review of the informed consent document at the first meeting with participants, the DRS-2 as well as other study assessments were administered (see footnote 1). Evaluations were administered by advanced clinical psychology doctoral students trained in the assessment of older adults and supervised by senior clinical psychologists (the second and third authors). Participants were given a $25 honorarium for their participation.

The assessment procedure was repeated up to four times approximately every 6 months. The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the investigators’ university.

Data Analysis

To determine if CSC mediated the relationship between cognitive functioning and OCD symptoms, we used parallel process latent growth modeling to evaluate the relationship of the predictor variable, to the growth of the mediator process, and the growth of the outcome process (see Cheong, MacKinnon, & Khoo, 2003; MacKinnon, 2008; see Figure 1). Analyses were done with Mplus, version 6.12 (Muthén & Muthén, 2007). Testing of the parallel process model was done as follows. First, each variable was evaluated as an unconditional growth model. That is, we evaluated the growth curve for each variable individually to determine the growth trajectory for the measure score. The unconditional model provided information on the shape (e.g., linear, quadratic, cubic) and whether there was significance of change in the variable over time. Additionally, the unconditional model provided information on the relationship between change in the variable over time (e.g., slope) and measure score at specific time points (e.g., intercepts) as well as information on slope and intercept heterogeneity (i.e., significant differences between participant scores at specific time points, or significant between person differences in score change over time).

Next, we tested the parallel process mediational model. Full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation was used due to the presence of missing data. This method uses all data available for each case and thus avoids biases and the loss of power associated with traditional approaches to missing data (Allison, 2003; Schlomer, Bauman, & Card, 2010). Overall model fit was determined following the recommendations of Bentler (2007; Hu & Bentler, 1999) and the following fit indices computed: (a) the Comparative Fit Index (CFI; Bentler, 1990), with values greater than .95 indicating reasonable model fit; and (b) the Standardized Root Mean Residual (SRMR), with values less than .08 indicating a well-fitting model.

In each parallel process model, two sets of latent growth factors were specified, one for the mediator, and one for the dependent variable. A latent variable for the independent variable, cognitive functioning, was not used due to an absence of significant change in DRS-2 scores over time (see unconditional model evaluation below). Two variables of the growth models were represented by latent factors, the intercept factor, and the slope factor. The intercept factor represented the starting point of the growth trajectory at the specified time point. We specified the starting point as T1 for the independent variable, cognitive functioning; T2 for the mediator, CSC; and T3 for the dependent variable, OCD symptoms. This approach was used to assess relationships between the variables across time points, and to gain information on order effects, although temporal precedence could not be fully determined with this statistical technique and the study design. Depending on results from the unconditional models, slope growth trajectories were defined as linear, quadratic, or cubic in order to better fit the data. Parallel process modeling is unique in that it allows for separate modeling of each variable while also assessing for relationships between growth and static time-point dependent measure scores. Lastly, we assessed the significance of the mediated effect using MacKinnon's asymmetric confidence interval (CI; MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002). A mediated effect was supported if the computed 95% confidence interval (CI) did not contain zero, which would indicate that the independent variable affected the trajectory of the mediator, which in turn, influenced the trajectory of the dependent variable. An advantage of using this technique to assess mediation is that the asymmetric CI method has greater power compared to other methods for testing mediation (Cheong, MacKinnon, & Khoo, 2003).

Results

Participants’ mean scores on measures of cognitive functioning, CSC, and OCD symptoms are shown in Table 1. Participants’ mean scaled scores on DRS-2 cognitive functioning measures were at or above the age- and education-adjusted means (M = 10; SD = 3). The sample's mean OCI-R score was congruent with the scores reported by Teachman (2007) in an evaluation of community older adults (M = 11.85; SD = 13.86). Participants’ T1 mean CSC-E score was equivalent to the score reported at the initial evaluation of older adults presenting at a medical clinic for hearing evaluation (M = 30.23; SD = 9.72; Mohlman, 2009).

Unconditional Growth Models

Unconditional growth models for each variable were evaluated first to determine mean initial scores on each measure (i.e., specified intercept) and whether there was variability in initial scores. Additionally, the model evaluated whether there was mean score change over time (i.e., a significant slope) and whether there was participant heterogeneity in the pattern of score change. Unconditional models for each study variable were tested using three time points, T1, T2, and T3, because of the small sample size available at T4 (n = 96). Results of the evaluations of the unconditional growth models are presented in Table 2. Both cross sectional and across time points simple correlations between all study variables are shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

Unconditional Growth Curve Models

| Variable | Fit Statistics | Intercept Factor | Slope Factor | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Variance (SE) | Mean | Variance (SE) | ||

| DRS-2 | χ2 = 29.64***, df = 2 | 11.16** | 5.30** (1.86) | 0.23 | 1.34* (0.54) |

| CFI = 0.43 | |||||

| SRMR = 0.23 | |||||

| I/P | χ2 = 23.97***, df = 2 | 10.73** | 1.98 (1.40) | −0.07 | 0.92** (0.34) |

| CFI = 0.20 | |||||

| SRMR = 0.35 | |||||

| Conceptualization | χ2 = 97.98***, df = 2 | 10.46** | 2.60* (1.26) | 0.37** | 0.24 (0.22) |

| CFI = 0.24 | |||||

| SRMR = 0.49 | |||||

| CSC-E | χ2 = 2.25, df = 1 | 31.62** | 65.16** (10.34) | −1.58** | 10.79 (5.91) |

| CFI = 0.98 | |||||

| SRMR = 0.02 | |||||

| OCI-R | χ2 = 0.65, df = 2 | 12.28** | 73.82** (11.26) | −0.94** | 4.54**(1.88) |

| CFI = 1.00 | |||||

| SRMR = 0.01 | |||||

Note. χ2 = chi-square statistic reflecting overall model fit (p > .05 indicates a good fit); CFI = Comparative Fit Index (≥ .95 indicates a good fit); SRMR = Standardized Root-Mean-Square Residual (≤ .08 is considered a good fit). All values for intercept and slope are unstandardized. Negative variance estimates are attributable to poor model fit.

p ≤ .05

p ≤ .001

Table 3.

Correlations between Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 T1 DRS-2 | - | ||||||||||||||

| 2 T2 DRS-2 | 0.50** | - | |||||||||||||

| 3 T3 DRS-2 | 0.57** | 0.45** | - | ||||||||||||

| 4 T1 I/P | 0.60** | 0.30** | 0.47** | - | |||||||||||

| 5 T2 I/P | 0.39** | 0.65** | 0.27** | 0.28** | - | ||||||||||

| 6 T3 I/P | 0.36** | 0.24* | 0.72** | 0.48** | 0.22* | - | |||||||||

| 7 T1 Concept | 0.73** | 0.47** | 0.38** | 0.21** | 0.42** | 0.16 | - | ||||||||

| 8 T2 Concept | 0.42** | 0.71** | 0.33** | 0.11 | 0.27** | 0.19 | 0.52** | - | |||||||

| 9 T3 Concept | 0.43** | 0.39** | 0.59** | 0.19* | 0.37** | 0.22* | 0.66** | 0.38** | - | ||||||

| 10 T1 CSC | −0.19** | −0.09 | −0.05 | −0.19* | −0.16 | −0.04 | −0.18* | −0.12 | −0.11 | - | |||||

| 11 T2 CSC | −0.14 | −0.16 | −0.03 | −0.06 | −0.15 | 0.03 | −0.20* | −0.13 | −0.07 | 0.64** | - | ||||

| 12 T3 CSC | −0.14 | −0.20* | −0.20* | −0.13 | −0.16 | −0.11 | −0.21* | −0.16 | −0.23* | 0.48** | 0.63** | - | |||

| 13 T1 OCI | −0.21** | −0.04 | −0.01 | −0.18* | −0.14 | −0.07 | −0.18* | −0.06 | −0.06 | 0.34** | 0.30** | 0.45** | - | ||

| 14 T2 OCI | −0.13 | −0.12 | −0.04 | −0.13 | −0.14 | −0.16 | −0.09 | −0.13 | 0.01 | 0.26** | 0.32** | 0.43** | 0.73** | - | |

| 15 T3 OCI | −0.12 | −0.11 | −0.09 | −0.19* | −0.10 | −0.18 | −0.08 | −0.16 | −0.04 | 0.24* | 0.18 | 0.45** | 0.79** | 0.84** | - |

Note. T1 = the study time 1 assessment; T2 = the study time 2 assessment, which occurred approximately 6-months after the time 1 assessment; T3 = the study time 3 assessment which occurred approximately 6-months after the time 2; DRS-2 = Mattis Dementia Rating Scale 2 total scaled score; I/P = Mattis Dementia Rating Scale 2 Initiation/Perseveration subscale scaled score; Concept = Mattis Dementia Rating Scale 2 Conceptualization subscale scaled score; CSC-E = the Cognitive Self-Consciousness Scale-Expanded total score; OCI-R = the Obsessive Compulsive Inventory-Revised total score. T = assessment time, 1, 2, or 3.

p ≤ .05

p ≤ .01.

Cognitive Functioning

Initial evaluation of the DRS-2 total scaled score unconditional growth model resulted in a psi matrix warning, although all parameters were able to be estimated. A re-specified model with the residual variance for T3 score constrained to zero (there was little residual variance) (cf. Savalei, & Kolenikov, 2008) eliminated estimation problems. As shown in Table 2, the DRS-2 score intercept at T1 was significantly different from zero, and there was significant variability in participants’ initial scores. The DRS-2 mean slope was not significant indicating that the average score did not change over time, although there was significant variability in how participants’ DRS-2 scores changed over time (Table 2). Although model fit was poor, we did not attempt to re-specify the model because of the lack of change over time, and used T1 score only in the evaluation of our mediator model.

In the evaluation of the DRS-2 I/P scaled score unconditional growth model we again constrained the residual variance at T3 to zero after an initial psi matrix warning. The mean T1 I/P intercept score was significantly different from zero, although there was not significant variability in participants’ mean starting I/P scores at T1. Additionally, the I/P scaled score slope was not significant, again indicating mean score did not change over time, although there was significant variability in participants’ pattern of score change over time (Table 2). Although model fit was poor, again we did not attempt to re-specify the model because of the lack of change over time, and used T1 score only as a cognitive functioning variable in the evaluation of our mediator model.

Evaluation of the DRS-2 Conceptualization scaled score unconditional growth model was again conducted with the residual variance for T3 constrained to zero due to an initial psi matrix warning. The intercept was significantly different from zero and there was significant variability in participants’ T1 scores. Mean score significantly changed over time, but there was not significant variability in the pattern of change over time (Table 2). Although model fit was again poor, we did not attempt to re-specify the model because of the small change seen in Conceptualization score and used T1 score in evaluations of models, which was necessary for the two other cognitive functioning variables, DRS-2 total score and I/P scale score.

Cognitive Self-Consciousness and OCD Symptoms

Evaluation of the CSC-E scores unconditional growth indicated the T1 score was significantly different from zero, and that there was significant variability in participants’ T1 scores. Mean CSC-E score significantly changed over time, although there was not significant variability in the pattern of change (Table 2). Initial evaluation of the OCI-R scores unconditional growth model resulted in a theta matrix warning, although all parameters were able to be estimated. A re-specified model with the residual variance for T3 OCI-R scores constrained to zero eliminated estimation problems. The intercept for OCI-R scores was significantly different from zero and there was significant variability in participants’ T1 OCI-R scores. Additionally, OCI-R slope was significant indicating that overall OCI-R scores decreased over time. There was also significant variability in this pattern of change in OCD symptoms.

In the moderation and meditational model estimation that follows, T3 OCI-R scores residuals were contained to zero for all analyses.

Evaluation of Moderation

Before we evaluated CSC score as a mediator, we first tested whether the relationships between measures of cognitive functioning and OCD symptoms differed across CSC scores (i.e., CSC moderated the relationship). The T1 DRS total scaled score and T1 CSC-E score interaction did not predict change over time in OCI-R score, β = −0.07. p = .41. Similar findings were observed in the evaluations of the interactions between CSC score and the I/P and Conceptualization subscale scores (ps = .92 and .71, respectively). Therefore, there was no evidence of moderation.

Mediational Model Evaluations

Model 1

To determine whether overall cognitive functioning affected OCD symptoms through CSC, we conducted parallel process modeling by specifying DRS-2 total scaled scores at T1 as the independent variable (IV), CSC-E scores at T2 as the mediator, and OCI-R total scores at T3 as the dependent variable (DV) (see Figure 1). The model fit the data well, χ2 (13) = 26.92, p < .05; CFI = 0.96; SRMR = 0.06. DRS-2 total scaled scores at T1 were negatively related to CSC-E score slope, β = −0.25, p < .001, indicating that poorer initial cognitive functioning predicted increases in CSC over time. CSC-E score slope also predicted OCI-R score slope, β = 0.46, p < .001. Results indicate that as CSC-E score increased over time, OCD symptom severity increased. Further, the indirect effect of DRS-2 total scaled score through CSC score slope on OCD symptom slope was significant using asymmetric 95% confidence interval generated in a separate bootstrapped analysis of the model, 95% CI [−0.485, −0.111]. Although the direct relationship between our IV, DRS-2 scaled score, and the DV, OCI-R score, was not significant, β = −0.12, p = .095, MacKinnon (2008) argued that a mediated effect can exist regardless of the presence of the direct relationship.

In summary, as predicted, lower initial cognitive functioning scores predicted increases in CSC scores over time, which in turn predicted increases in OCD symptoms over time.

Model 2

To assess whether cognitive functioning as measured by the DRS-2 I/P and Conceptualization subscales affected OCD symptoms through CSC, we conducted a second parallel process model evaluation with these two DRS-2 subscale scores. T1 DRS-2 I/P and Conceptualization scaled scores were included as the model IVs, CSC-E scores were again treated as the mediator, and OCI-R total scores as the DV (Figure 2). The model fit the data well, χ2 (df = 15) = 29.05, p < .01; CFI = 0.96; SRMR = 0.05. DRS-2 Conceptualization scaled scores at T1 predicted CSC-E score slope, β = −0.24, p = .001, indicating that poorer conceptualization skills were associated with increasing CSC over time. There was also a significant positive relationship between change in CSC-E and OCI-R score slope, β = 0.46, p < .001, indicating that increases in CSC were associated with increases in OCD symptoms over time. There was not a direct relationship between Conceptualization scores at T1 and OCI-R score change, β = −0.04, p = .604. Relationships were weaker with the DRS-2 I/P scores. There was a trend for DRS-2 I/P scores at T1 to predict change in CSC-E slope, β = −0.14, p = .105, suggesting that poorer I/P performance might be associated with increased CSC over time. There was also a trend for DRS-2 I/P scores at T1 to directly affect OCI-R score slope, β = −0.13, p = .079, indicating that poorer I/P test performance might be associated with increased OCD symptoms over time.

The indirect effects through the CSC score mediator were tested using asymmetric 95% confidence interval generated in separate bootstrapped analyses of the model. CSC-E scores mediated the relationship between Conceptualization score at T1 and OCI-R score slope, 95% CI [−0.63, −0.18]. Poorer initial conceptualization skill predicted increased CSC, which in turn predicted increased OCD symptoms over time. However, CSC-E score did not mediate the relationship between I/P and OCI-R, 95% CI [−0.440, 0.001].

In summary, as predicted, lower initial Conceptualization scores predicted increases in CSC score over time, which in turn predicted increased OCD symptoms over time. However, the predicted meditational relationship was not found when using I/P scaled scores.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to examine whether CSC mediated the relationship between older adults cognitive functioning and OCD symptoms. As predicted, we found that CSC measure score mediated the relationship between DRS total scaled scores and OCI-R scores. Poorer initial cognitive functioning predicted increases in CSC over time, which in turn predicted increased OCD symptoms over approximately 18 months. Broadly, mental illness has been linked to poorer overall cognitive functioning (Gale, Batty, Tynelius, Dreary, & Rasmussen, 2010). The DRS-2 measures overall cognitive functioning with an emphasis on frontal-lobe dysfunction (Goldman & Litvan, 2011), perhaps accounting for the relationship between increasing CSC over time and poorer initial cognitive functioning. The DRS-2 score is likely a sensitive measure of the frontal-striatal dysfunction associated with OCD.

CSC, a hyper-awareness of thought broadly, could be a mechanism by which the cognitive dysfunction associated with OCD leads to the obsessional problems characteristic of the condition. Individuals with hyperactive frontal-striatal functioning are theorized to process stimuli less efficiently and more consciously (Rauch & Savage, 2000). This cognitive processing difference might elevate CSC, which could then lead to greater reactivity to common, personally relevant, negative intrusive thoughts (Janeck et al., 2003). Again, greater reactivity to negative intrusive thoughts has been shown to be importantly related to OCD symptoms (e.g., Salkovskis et al., 1995).

The results of testing of the CSC mediational model with the specific cognitive functioning skills measured on the DRS-2 associated with the frontal-striatal dysfunction characteristic of OCD was inconsistent. We examined the DRS-2 subscales of Initiation-Perseveration and Conceptualization, as they have been linked to executive functioning in individuals (Judd, 2011; Nadler et al, 1993; Mega & Cummings, 1994), a functional domain that is affected by frontal-striatal neuropathology and characterizes OCD (e.g., Snyder, Kaiser, Warren, & Heller, 2015) . CSC-E score mediated the relationship between DRS-2 Conceptualization scaled scores and OCI-R scores, indicating that poorer initial conceptualization skill predicted increased CSC, which in turn predicted increased OCD symptoms over time. However, CSC-E did not significantly mediate the relationship between DRS-2 I/P scaled scores and OCI-R scores, although there were trends for the I/P scaled scores to relate to CSC-E scores and OCI-R scores in the expected direction. The discrepant findings involving relationships with these two cognitive functioning domains are not limited to our study, but have also been seen in studies of frontotemporal dementia (FTD). Individuals with FTD are thought to have dysfunctions in frontal-striatal functioning (Neary et al., 1998; Rosen et al., 2002, 2004). The Conceptualization and I/P subscales of the DRS-2 have been shown to differentiate group profiles of individuals with FTD and individuals with Alzheimer's disease. However, in examination of the DRS-2 individual subscales, only I/P reliably differentiated the groups (Rascovsky, Salmon, Hansen, & Galasko, 2008).

There are several possible explanations for these findings. One possibility lies in the psychometrics of the DRS-2. In examining reliability of DRS-2 scores in larger and more heterogeneous samples, internal consistency reliability of I/P subscale scores was low (coefficient alpha = .45; Smith et al. 1994), whereas internal consistency of Conceptualization subscale scores have been found to be higher (coefficient alpha = .75; Smith et al. 1994). Thus, discrepant results between the Conceptualization and I/P subscales could be the result of low reliability in the measurement of I/P skills. It is also possible that the particular skills assessed in the Conceptualization subscale (i.e., ability to abstract, to identify similarities, and detect differences) are more strongly related to OCD neuropathology. The skills assessed in the I/P subscale (i.e., oral-verbal skills, graphomotor skills, and ability to initiate, switch, and terminate a specific activity with fluency and without perseveration or inappropriate intrusion of a prior activity) may not be as importantly related to OCD symptoms. Thus, these difference between what I/P and Conceptualization subscales measure could explain our findings.

Unfortunately, we were not able to examine change in cognitive functioning in our study because DRS-2 total and subscale scores remained stable over the relatively short duration of the study. While this situation limited our model testing, it is not a surprising outcome in longitudinal evaluations of cognitive aging (cf. Salthouse, 2010) and is likely a result of our use of age and education adjusted measures of cognitive functioning, excluding impaired older adults, the relatively short duration on the study, and evaluation of an older sample (almost 77 years) where significant age related cognitive functioning changes may have begun earlier. As such, we were not able to determine whether decline in cognitive functioning due to aging or other factors leads to increasing OCD symptoms in late-life. The executive dysfunction thought to characterize individuals with OCD is also associated with the effects of aging, as the frontal lobes show more age-related atrophy compared to other brain regions (von Hippel, 2007). This decline in functioning could potentially increase the risk of developing OCD after crossing a frontal-striatal functioning threshold, and this process could also increase CSC. Future studies should elucidate this relationship by using cognitive functioning measures that are more sensitive to age-related changes and by including older adult participants with greater variability in cognitive functioning. Additionally, allowing for longer time intervals between assessment dates or conducting a longitudinal study with multiple assessment points over a time period greater than 18 months might capture change in cognitive functioning more effectively.

In addition to the limited ability to examine decline in cognitive functioning with the present older adult sample, the study has several other limitations. The participant sample was relatively small even at initial assessment, and study attrition over the longitudinal investigation was approximately half of the sample. Small sample size affected our ability to include all four time points in analyses and to test relations between slopes and intercepts in the evaluations of our models. Further, although significant efforts were made to recruit a diverse older adult sample for the study, we had limited success. Study participants were predominantly Caucasians and our sample was better-educated and more affluent than nationally representative samples of the current cohort of older adults. These demographic differences are problematic in that older adults’ level of education and income appear to be related to cognitive decline (Long, Ickovics, Gill, & Horwitz, 2001). Attempts to replicate and extend testing of this and other risk models for late-life obsessional difficulties are needed with larger older adult samples that are more diverse and who are followed over a longer time period.

Despite these limitations, our findings provide support for an important risk factor model, which could prove to have implications for OCD treatment or prevention. Individuals with OCD related neuropathology involving poor general executive functioning or conceptualization skills may have increased susceptibility to develop CSC, and therefore, be hyperaware of intrusive, thoughts. They might be at elevated risk to appraise common negative thoughts as significant, and engage in effortful attempts at mental control, processes posited to be important to OCD symptom development.

Results suggest that CSC might be and important target in new treatment or prevention programs. Additional intervention strategies are needed for OCD as forty percent of patients who receive behavioral or pharmacological treatments remain significantly symptomatic after therapy completion (Hollander, Alterman, & Dell'Osso, 2006). Metacognitive processes including CSC have begun to be evaluated in OCD treatment studies. Solem, Håland, Vogel, Hansen, and Wells (2009) found that OCD patients’ response to treatment with exposure and response prevention (behavior therapy) was robustly related to changes in metacognitive processes. Solem et al. found that changes in a multidimensional measure of metacognition explained over 20% of the variance in symptom change at post-treatment even after controlling for changes in mood. Scores on several of the subscales of the Meta-Cognitions Questionnaire (MCQ; Cartwright-Hatton and Wells, 1997) correlated with symptom change scores including scoring on the measures CSC subscale.

OCD has been significantly understudied in older adults, although it is a prevalent and debilitating problem of late life (e.g., Carmin et al., 2012; Calamari et al., in press). Increased understanding of the processes important to the development and continuation of late-life obsessional problems will address a major public health problem as older adults constitute a growing percentage of the population. Significantly more study of late-life OCD and related conditions is needed.

Highlights.

We tested a risk model for late-life obsessive compulsive disorder symptoms (OCD).

Tested whether cognitive self-consciousness (CSC) mediated the relationship between cognitive functioning and OCD.

Lower cognitive functioning scores predicted increases in CSC, which predicted increases in OCD.

We discuss implications for understanding late-life obsessional problems.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health grant R21MH069704 (Risk Factors for Late-Life Anxiety Disorders) to John E. Calamari and John L. Woodard.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

A complete list of the assessment battery is available from the corresponding author upon request.

In the current study, DRS-2 scores were stable over time based on across time point correlations [T1 and T2 r(151) = .504, p < .001; T1 and T3 r(113) = .567, p < .001; T2 and T3 r(108) = .451, p < .001;] and as reflected in unconditional model analyses for DRS-2 variables in results. Cronbach's alpha was not computed with the current sample as not all participants were administered all scale items per the test protocol (see Woodard & Axelrod, 2008).

Contributor Information

Caroline Prouvost, Department of Psychology, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science.

John E. Calamari, Department of Psychology, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science

John L. Woodard, Department of Psychology, Wayne State University.

References

- Allison PD. Missing data techniques for structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:545–557. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) American Psychiatric Pub; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter LR, Jr, Schwartz JM, Bergman KS, Szuba MP, Guze BH, Mazziotta JC, Phelps ME. Caudate glucose metabolic rate changes with both drug and behavior therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1992;49(9):681–689. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820090009002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaudreau SA, O'Hara R. Late-life anxiety and cognitive impairment: a review. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2008;16(10):790–803. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31817945c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. On tests and indices for evaluating structural models. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;42(5):825–829. [Google Scholar]

- Bielak AAM, Gerstorf D, Kiely KM, Anstey KJ, Luszcz M. Depressive Symptoms Predict Decline in Perceptual Speed in Older Adulthood. Psychology and Aging. 2011;26(3):576–583. doi: 10.1037/a0023313. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0023313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breiter HC, Rauch SL, Kwong KK, Baker JR, Weisskoff RM, Kennedy DN, Rosen BR. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of symptom provocation in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53(7):595. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830070041008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calamari JE, Janeck AS, Deer TM. Frost RO, Steketee G, editors. Cognitive processes and obsessive compulsive disorder in older adults. Cognitive approaches to obsessions and compulsions: Theory, assessment, and treatment. 2002:315–335. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-008043410-0/50021-0.

- Calamari JE, Wilkes CM, Prouvost C. Abramowitz J, McKay D, Storch E, editors. The Nature and Management of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and the Obsessive-Compulsive Related Conditions Experienced by Older Adults. Handbook of Obsessive-Compulsive Related Disorders. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Calamari JE, Woodard JL, Armstrong KM, Molino A, Pontarelli NK, Socha J, Longley SL. Assessing older adults' Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder symptoms: Psychometric characteristics of the Obsessive Compulsive Inventory-Revised. Journal of obsessive-compulsive and related disorders. 2014;3(2):124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jocrd.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmin CN, Calamari JE, Ownby RL. OCD and Spectrum Conditions in Older Adults. In: Steketee G, editor. Oxford Handbook of Obsessive Compulsive and Spectrum Disorders. Oxford University Press; New York: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright-Hatton S, Wells A. Beliefs about worry and intrusions: The meta-cognitions questionnaire and its correlates. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1997;11:279–296. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(97)00011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatfield MD, Brayne CE, Matthews FE. A systematic literature review of attrition between waves in longitudinal studies in the elderly shows a consistent pattern of dropout between differing studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2005;58:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong J, MacKinnon DP, Khoo ST. Investigation of mediational processes using parallel process latent growth curve modeling. Structural Equation Modeling. 2003;10(2):238–262. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM1002_5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coblentz JM. Presenile dementia: Clinical aspects and evaluation of cerebrospinal fluid dynamics. Archives of Neurology. 1973;29:299–308. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1973.00490290039003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RJ, Calamari JE. Thought-focused attention and obsessive compulsive symptoms: An evaluation of cognitive self-consciousness in a nonclinical sample. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2004;28:457–471. [Google Scholar]

- de Bruin GO, Muris P, Rassin E. Are there specific meta-cognitions associated with vulnerability to symptoms of worry and obsessional thoughts? Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;42:689–699. [Google Scholar]

- Deckersbach T, Savage CR, Curran T, Bohne A, Wilhelm S, Baer L, Rauch SL. A study of parallel implicit and explicit information processing in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159(10):1780–1782. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Huppert JD, Leiberg S, Langner R, Kichic R, Hajcak G, et al. The Obsessive–Compulsive Inventory: development and validation of a short version. Psychological Assessment. 2002;14:485–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Steketee G, editors. Cognitive approaches to obsessions and compulsions: Theory, assessment, and treatment. Elsevier; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gale, Batty, Tynelius, Dreary, Rasmussen Intelligence in early adulthood and subsequent hospitalization for mental disorders. Epidemiology. 2010;21:70–77. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181c17da8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman BL, Martin ED, Calamari JE, Woodard JL, Chik HM, Messina MG, et al. Implicit learning, thought focused attention and obsessive-compulsive disorder: A replication and extension. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman JG, Litvan I. Mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Minerva Medica. 2011;102(6):441. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Delgado P, Heninger GR, Charney DS. The yale-brown obsessive compulsive scale: II. Validity. Archives of general psychiatry. 1989;46(11):1012–1016. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110054008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henin A, Savage CR, Rauch SL, Deckersbach T, Wilhelm S, Baer L, Jenike MA. Is age at symptom onset associated with severity of memory impairment in adults with obsessive-compulsive disorder? American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158(1):137–139. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeringa SG, Fisher GG, Hurd M, Langa KM, Ofstedal MB, Plassman BL, Weir DR. Aging, Demographics and Memory Study (ADAMS) University Of Michigan; Ann Arbor: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hollander E, Alterman R, Dell'Osso B. Approaching treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder with brain stimulation interventions: The state of the art. Psychiatric Annals. 2006;36(7):480–488. [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobi DM, Calamari JE, Woodard JL. Obsessive-compulsive disorder beliefs, metacognitive beliefs and obsessional symptoms: Relations between parent beliefs and child symptoms. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy. 2007;13:153–162. [Google Scholar]

- Janeck AS, Calamari JE, Riemann BC, Heffelfinger SK. Too much thinking about thinking?: Metacognitive differences in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2003;17:181–195. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(02)00198-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judd A. Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms Predict Future Executive Functioning Decline. Anxiety. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Jurica PJ, Leitten CL, Mattis S. Dementia RatingScale-2: Professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources; Lutz, FL: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of general psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long JA, Ickovics JR, Gill TM, Horwitz RI. The cumulative effects of social class of mental status decline. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2001;49:1005–1007. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas JA, Ivnik RJ, Smith GE, Bohac DL. Normative data for the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 1998;13:41–42. doi: 10.1076/jcen.20.4.536.1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon D. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Routledge Academic; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(1):83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marker CD, Calamari JE, Woodard JL, Riemann BC. Cognitive self-consciousness, implicit learning and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2006;20:389–407. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mega MS, Cummings JL. Frontal-subcortical circuits and neuropsychiatric disorders. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 1994;6:358–370. doi: 10.1176/jnp.6.4.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohlman J. Cognitive self-consciousness–a predictor of increased anxiety following first-time diagnosis of age-related hearing loss. Aging and Mental Health. 2009;13(2):246–254. doi: 10.1080/13607860802428026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide (Sixth Edition) Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nadler JD, Richardson ED, Malloy PF, Marran ME, Hostetler Brinston ME. The ability of the Dementia Rating Scale to predict everyday functioning. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 1993;8(5):449–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, Passant U, Stuss D, Black SA, et al. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration A consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 1998;51(6):1546–1554. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.6.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nissen MJ, Bullemer P. Attentional requirements of learning: Evidence from performance measures. Cognitive Psychology. 1987;19:1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Okura T, Plassman BL, Steffens DC, Llewellyn DJ, Potter GG, Langa KM. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms and their association with functional limitations in older adults in the United States: the aging, demographics, and memory study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2010;58(2):330–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02680.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rascovsky K, Salmon DP, Hansen LA, Galasko D. Distinct cognitive profiles and rates of decline on the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale in autopsy-confirmed frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2008;14(03):373–383. doi: 10.1017/S135561770808051X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch SL, Jenike MA, Alpert NM, Baer L, Breiter HC, Savage CR, Fischman AJ. Regional cerebral blood flow measured during symptom provocation in obsessive–compulsive disorder using oxygen 15-labeled carbon dioxide and positron emission tomography. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1994;51:62–70. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010062008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch SL, Savage CR. Investigating cortico-striatal pathophysiology in obsessive-compulsive disorders: Procedural learning and imaging probes. In: Goodman WK, Rudorfer MV, Maser JD, editors. Obsessive-compulsive disorder: Contemporary issues in treatment. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; Mahwah, NJ: 2000. pp. 133–154. [Google Scholar]

- Rauch SL, Savage CR, Alpert NM, Dougherty D, Kendrick A, Curran T, et al. Probing striatal function in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a PET study of implicit sequence learning. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 1997;9(4):568–573. doi: 10.1176/jnp.9.4.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth RM, Milovan D, Baribeau J, O’Connor K. Neuropsychological functioning in early-and late-onset obsessive-compulsive disorder. The Journal of neuropsychiatry and clinical neurosciences. 2005;17(2):208–213. doi: 10.1176/jnp.17.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen HJ, Hartikainen KM, Jagust W, Kramer JH, Reed BR, Cummings JL, et al. Utility of clinical criteria in differentiating frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) from AD. Neurology. 2002;58(11):1608–1615. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.11.1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen HJ, Narvaez JM, Hallam B, Kramer JH, Wyss-Coray C, Gearhart R, et al. Neuropsychological and functional measures of severity in Alzheimer disease, frontotemporal dementia, and semantic dementia. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders. 2004;18(4):202–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salkovskis PM. Obsessional-compulsive problems: A cognitive-behavioural analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1985;23(5):571–583. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(85)90105-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(85)90105-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salkovskis PM, Richards H, Forrester E. The Relationship Between Obsessional Problems and Intrusive Thoughts. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 1995;23(03):281–299. [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA. Influence of age on practice effects in longitudinal neurocognitive change. Neuropsychology. 2010;24(5):563. doi: 10.1037/a0019026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse T. Consequences of age-related cognitive declines. Annual review of psychology. 2012;63:201. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena S, Rauch SL. Functional neuroimaging and the neuroanatomy of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2000;23(3):563–586. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlomer GL, Bauman S, Card NA. Best practices for missing data management in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2010;57:1–10. doi: 10.1037/a0018082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GE, Ivnik RJ, Malec JF, Kokmen E, Tangalos E, Petersen RC. Psychometric properties of the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale. Assessment. 1994;1(2):123–131. doi: 10.1177/1073191194001002002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socha JL, Calamari JE, Woodard JL. Predictors of attrition in a longitudinal study of older adults. 2012 Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Solem S, Håland ÅT, Vogel PA, Hansen B, Wells A. Change in metacognitions predicts outcome in obsessive–compulsive disorder patients undergoing treatment with exposure and response prevention. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47(4):301–307. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder HR, Kaiser RH, Warren SL, Heller W. Obsessive-compulsive disorder is associated with broad impairments in executive function: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychological Science. 2015;3(2):301–330. doi: 10.1177/2167702614534210. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/2167702614534210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steketee G, Schmalisch CS, Dierberger A, DeNobel D, Frost RO. Symptoms and history of hoarding in older adults. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders. 2012;1(1):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S. Early versus late onset obsessive–compulsive disorder: Evidence for distinct subtypes. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31(7):1083–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teachman BA. Linking obsessional beliefs to OCD symptoms in older and younger adults. Behaviour research and therapy. 2007;45(7):1671–1681. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitaliano PP, Breen AR, Russo J, Albert M, Vitiello MV, Prinz PN. The clinical utility of the Dementia Rating Scale for assessing Alzheimer patients. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1984;37:743–753. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(84)90043-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Hippel W. Aging, executive functioning, and social control. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2007;16(5):240–244. [Google Scholar]

- Wells A. Emotional disorders and metacognition: Innovative Cognitive Therapy. John Wiley & Sons; West Sussex, England: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 Health Survey: manual and interpretation guide. Quality Metric Inc.; Lincoln, RI: 1993/2000. [Google Scholar]