Abstract

There is strong evidence that diabetes mellitus increases the risk of cognitive impairment and dementia. Insulin signaling dysregulation and small vessel disease in the base of diabetes may be important contributing factors in Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia pathogenesis, respectively. Optimal glycemic control in type 1 diabetes and identification of diabetic risk factors and prophylactic approach in type 2 diabetes are very important in the prevention of cognitive complications. In addition, hypoglycemic attacks in children and elderly should be avoided. Anti-diabetic medications especially Insulin may have a role in the management of cognitive dysfunction and dementia but further investigation is needed to validate these findings.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Cognitive disorders, Dementia, Diabetes, Insulin

Core tip: Diabetes mellitus increases the risk of cognitive impairment and dementia. Impairment of insulin signaling is a critically important factor and may be the cornerstone of the development of these cognitive sequences regardless of diabetic status. Therefore, anti-diabetic medications especially insulin therapy may have a significant role in the management of various cognitive and mental dysfunctions.

INTRODUCTION

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is one of the most common diseases whose prevalence is on the rise. It is believed that within the next 30 years, the number of diabetic patients will double in comparison to the year 2000[1]. On the other hand, diabetes is amongst the diseases with higher complications (perhaps even the highest) and these complications lower the quality of life in patients significantly[2-4]. Diabetes is a systemic disease as it affects various body systems to some extent. For instance, diabetes can disrupt proper function in cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, immune and nervous systems. The functional impairment of peripheral nervous system can lead to diabetic foot and in worst cases to amputation and hence physical disability. Involvement of retina [diabetic retinopathy (DR)] can lead to loss of vision and blindness.

Adverse effects of diabetes on cognitive system and memory disorders have been noticed by researchers for a long time[2-4]. Equally, dementia is one of the most disabling public health problems. It affects the quality of life of demented patients and their caregivers. It also imposes a huge economic burden on countries. Therefore, identification of risk factors of dementia and the control of those factors is with utmost importance.

This review discusses the association between diabetes and the risk of cognitive impairment with more clinical aspects. Therefore, possible underlying mechanisms of cognitive impairment in diabetic patients will be discussed, and the effect of various treatments on prophylaxis and improvement of mental dysfunction will be reviewed.

OVERVIEW OF MEMORY AND COGNITION

Cognition is defined as “the mental action or process of acquiring knowledge and understanding through thought, experience, and the senses”[5].

Memory is the retention, recording, and process of retrieving knowledge. All knowledge gained from experience such as known facts, remembered events, gained and applied skills would be considered as memory[6]. Memory can be categorized into declarative and non-declarative memory. Declarative memory mostly corresponds to the learning and recalling new facts, events, and materials. Non-declarative memory refers to the many forms of memories that are reflective or incidental[6].

The “brain working memory” is defined as the ability to keep record of many bits of information at the same time and the recall of this information immediately if needed for subsequent thoughts[7]. When working memory is damaged, a wide range of cognition impairments occur and the patient will not be able to appropriately use his/her own information for thinking in different situations[6].

The majority of advanced cortical functions arise from association cortex. The main association areas are: (1) the parieto-occipitotemporal association area; (2) the prefrontal association area; and (3) the limbic association area[7].

Our knowledge about the mechanisms of thinking and remembering is little. It seems that each thought arises from simultaneous activation of many parts of the different areas in the brain such as cerebral cortex, limbic system, thalamus and reticular formation of the brainstem. The memory is the result of some events in the synaptic transmission by changing its basic sensitivity[7].

Constant neural activity that arises from traveling nerve signals to a temporary memory trace can create a “short term memory”. A temporary chemical or physical synaptic change that lasts for a few minutes up to several weeks makes an “intermediate long term memory”. Structural alterations in synapses occur when a “long term memory” is created and can be used weeks to years later[7]. The hippocampus and, to a lesser degree, the thalamus are responsible for deciding which thoughts are important enough to be saved as memories[7].

It is possible to acquire information about the patient’s cognitive, behavioral, linguistic, and executive functioning, and memory through Neuropsychological tests. These data can be used in the diagnosis of cognitive disorders and for localization of the abnormality in the brain, as well as, the assessment of therapeutic effects of any treatment modality on the cognitive dysfunction. Neurocognitive domains and some examples for their assessment are categorized in the Table 1[8,9].

Table 1.

| Cognitive domain | Examples of assessments |

| Complex attention (sustained attention, divided attention, selective attention, processing speed) | Sustained attention: Maintenance of attention over time Selective attention: Maintenance of attention despite competing stimuli and/or distractors Divided attention: Attending to two tasks within the same time period Processing speed can be quantified on any task by timing it |

| Executive function (planning, decision making, working memory, mental flexibility) | Planning: Ability to find the exit to a maze; interpret a sequential picture Decision making: Performance of tasks that assess process of deciding in the face of competing alternatives (e.g., simulated gambling) Working memory: Ability to hold information for a brief period and to manipulate it (e.g., adding up a list of numbers or repeating a series of numbers or words backward) Mental/cognitive flexibility: Ability to shift between two concepts, tasks, or response rules |

| Learning and memory [immediate memory, recent memory (including free recall, cued recall, and recognition memory), very-long- term memory (semantic, autobiographical), implicit learning] | Immediate memory span: Ability to repeat a list of words or digits. Note: Immediate memory sometimes subsumed under “working memory” (see “Executive Function”) Recent memory: Assesses the process of encoding new information (e.g., word lists, a short story, or diagrams) Free recall (the person is asked to recall as many words, diagrams, or elements of a story as possible Cued recall (examiner aids recall by providing semantic cues such as “list all the food items on the list” Recognition memory (examiner asks about specific items, e.g., “Was ‘apple’ on the list?”) Semantic memory (memory for facts) Autobiographical memory (memory for personal events or people) Implicit (procedural) learning (unconscious learning of skill) |

| Language [expressive language (including naming, word-finding, fluency, and grammar and syntax) and receptive language] | Expressive language: Confrontational naming (identification of objects or pictures) Fluency [e.g., name as many items as possible in a semantic (e.g., animals) or phonemic (e.g., words starting with “f”) category in 1 min] Grammar and syntax (e.g., omission or incorrect use of articles, prepositions, auxiliary verbs) Receptive language: Comprehension, performance of actions/activities according to verbal command |

| Perceptual-motor (includes abilities subsumed under the terms visual perception, visuoconstructional, perceptual-motor, praxis, and gnosis) | Visual perception: Line bisection tasks can be used to detect basic visual defect or intentional neglect Visuoconstructional: Assembly of items requiring hand-eye coordination, such as drawing, copying, and block assembly Perceptual-motor: Integrating perception with purposeful movement (e.g., rapidly inserting pegs into a slotted board) Praxis: Integrity of learned movements, such as ability to imitate gestures (wave goodbye) or pantomime use of objects to command (“show me how you would use a hammer”) Gnosis: Perceptual integrity of awareness and recognition, such as recognition of faces and colors |

| Social cognition (recognition of emotions, theory of mind) | Recognition of emotions: Identification of emotion in images of faces representing a variety of both positive and negative emotions Theory of mind: Ability to consider another person’s mental state (thoughts, desires, intentions) |

Neuropsychological evaluation measures the cognitive abilities in the patient quantitatively, and its results must be interpreted in the setting of the patient’s: Age, education, gender, and cultural background. In addition, reliability, validity, sensitivity, and specificity of these tests are important aspects that should be considered.

ETIOLOGY OF COGNITIVE DISORDERS

Dementia and cognitive dysfunction have many causes. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other degenerative diseases, vascular dementia, alcohol consumption, and certain drug abuse are some of these etiologies. Additional disorders that can cause memory loss and other cognitive impairments are listed in the Table 2[9].

Table 2.

Memory loss and cognitive impairment etiology[9]

| Degenerative disorders including Alzheimer’s disease |

| Vascular dementia |

| Depression and anxiety |

| Medication side effects |

| Disturbed sleep |

| Hormones |

| Metabolic disorders |

| Diabetes |

| Alcohol abuse |

| Lyme disease |

| Hippocampal sclerosis |

| Subdual and epidural hematomas |

| Vitamin B12 deficiency |

| Seizures |

| HIV associated neurocognitive disorder |

| Hashimoto’s encephalopathy |

HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus.

ASSOCIATION BETWEEN DIABETES AND COGNITIVE DECLINE

Cognitive dysfunction with its wide range, from mild cognitive impairment (MCI) through dementia, is one of the chronic complications of diabetes mellitus[10]. Both diabetes and cognitive impairment occur more commonly at older age. There is strong evidence that T2D increases the risk of dementia in the form of multi-infarct dementia, AD and mixed type dementia. There are some close associations between diabetes and vascular dementia of above 100%-160% compared to AD which is about 45% to 90%[10]. The long-term risk of dementia increases in patients with diabetes by a factor of two[11]. T2D also increases the risk of progression of MCI to dementia[11]. Even in pre-diabetic state; there is an increased risk of AD and dementia which are not related to the future development of diabetes[10]. About 80% of people with AD may have diabetes or impaired fasting glucose[12]. There is a faster deterioration of cognition in diabetic patients rather than non-diabetic elderly ones[13]. Diabetes is associated with 1.5-2 fold increased risk of cerebrovascular accidents[14] and the relative risk of stroke increases 1.15 (95%CI: 1.08-1.23) for every 1% increase in HbA1C[15].

In recent years, the relation of diabetes to memory disorders has been well established. In 2011, Wessels et al[16] published results of their comprehensive prospective study on a large sample size from 1992 to 2007. Patients in this cohort were examined at baseline and five follow-up assessments throughout the 15 years of study. During each evaluation, participants were given the Community Screening Interview for Dementia as part of a home visit. They followed up 1702 subjects and showed that diabetes reduced their cognitive capabilities via cardiovascular disruption[16]. The results of the Edinburgh Type 2 Diabetes Study that was conducted for evaluation of this correlation were published in 2013. At baseline, any clinical and subclinical macrovascular diseases including cardiovascular event history, carotid intima-media thickness, ankle brachial index, and serum N-terminal probrain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) were evaluated. Seven neuropsychological tests were also done at baseline, and after 4 years. They found that stroke and subclinical markers of cardiovascular and atherosclerosis are associated with cognitive decline in older patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D)[17].

Recent research collaboration between Mayo Clinic and Shanghai was reported in 2015. In this study, involving a considerable number of patients, the effect of diabetes on the cognitive function of patients was strongly evident. This was, of course, irrespective of patients’ gender, age and possible cardiovascular risk factors[18].

In one study, the relationship between T2D and cognitive impairment had been evaluated and the subjects with diabetes had lower MMSE score than those without diabetes (P < 0.01)[19]. Diabetes was also associated with increased odds of cognitive decline as determined by MMSE scores [odds ratio (OR), 1.9; 95%CI: 1.01-3.6]. Also, a statistically significant correlation between the duration of the disease and cognitive dysfunction was observed (P = 0.001). The same correlation was also found for the quality of diabetes control (P = 0.002).

In a different study that was carried out on 4206 subjects by Qiu et al[20], they investigated whether and the extent to which vascular and degenerative lesions in the brain mediate the association of diabetes with poor cognitive performance. They assessed cortical and subcortical infarcts and higher white matter lesion volume. They also evaluated neurodegenerative processes on magnetic resonance images. The results of this cross-sectional study showed that diabetic patients’ speed in processing and executive functions was markedly lower than others. However, their memory function score was not any better either[20].

The role of diabetes in neurodegeneration has been confirmed by neuroimaging and neuropathological studies. MRI studies have shown that T2D is strongly associated with brain atrophy[21]. The rate of global brain atrophy in T2D is up to 3 times faster than in normal aging[22,23].

SPECIFIC EFFECTS OF T1D AND T2D ON COGNITION

Diabetes mellitus is related to 40% higher rate of MCI; both amnestic and non-amnestic[24]. This is especially true when diabetes starts before the age of 65, or when the disease is more than 10 years. Treatment with insulin and the presence of diabetes complications such as retinopathy are other risk factors[25,26].

In children, the relationship between T1D and cognitive disorders is also reported[27]. Cognitive flexibility, visual perception, psychomotor speed, and attention are the main domains which are mostly affected early (on within 2 years in T1D), among which the mental slowing is the principal deficiency. Learning and memory function seem to be intact even in a prolonged hyperglycemia in T1D[25]. Young age is an important risk factor in developing cognitive deficits in T1D. It seems that children whose disease is diagnosed under the age of 7 are at a greater risk for more severe cognitive dysfunction[28].

Single-photon emission tomography in diabetic patients shows an abnormality in many brain regions, which correlate especially with diabetic microvascular complications and poor glycemic control in T1D. However, there is no strong evidence to support the importance of brain perfusion abnormalities in the development of cognitive dysfunction in T1D[29].

In both types of diabetes, neural slowing, cortical atrophy and microstructural abnormalities in white matter are prominent[24].

The effect of diabetes on patients’ mood and temper has also been investigated. In a recent article by Ho et al[30], they have pointed out the effects of diabetes on hippocampus neurogenesis and depression and the resulting cognitive.

DR AND COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT

It has been shown that there is an association between DR and cognitive impairment. According to some studies, the vascular complications of diabetes such as retinopathy are the most important predictors for the cognitive decline. Based on the similarity in anatomy, physiology, and embryology of cerebral and retinal small vessels, this association is particularly interesting[31].

In a systematic review which analyzed three studies, it has been proven a near three fold increased risk of cognitive impairment in patients with DR. However; the association between the severity of DR and cognitive decline was not clearly demonstrated. Only one study showed that the men with more severe cognitive impairment had greater degree of retinal involvement. The recent memory and the verbal learning were the most defective cognitive domains in these studies[32].

Some studies have reported an association between cognitive impairment and general (not diabetic) retinopathy independent of other cardiovascular risk factors but underlying etiology has not been clearly identified[33,34]. The higher prevalence of cognitive impairment even in those with non-DR provides some clues to investigate the underlying mechanism for this association in wider metabolic abnormalities (hypertension, dyslipidemia, and inflammatory stress) rather than a pure glucotoxic effect[32].

In a longitudinal study from using Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) data, the association between DR and cognitive impairment in T2M was confirmed. This study showed that cognitive dysfunction was a predictable consequence of DR. In the ACCORD data, the patients with DR had lower Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score[35].

In one cohort study by Crosby-Nwaobi et al[36], they compared patients with Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy with patients with Non Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy or no retinopathy. They found that there is an inverse relationship between the severity of DR and the severity of cognitive impairments: Those with no or mild form of DR had more deficits in attention/orientation, language, memory, and visuospatial ability fields in comparison with patients with severe DR. However; their study showed that cognitive impairment was more prominent in those with mild retinopathy than those without retinopathy[36].

BRAIN IMAGING IN DIABETES

Brain imaging can be an important tool to clarify the underlying pathogenesis for cognitive impairments in diabetic patients. Some researchers have been reported both focal and global cerebral changes[37].

Slight brain structural abnormalities have been reported in T1D[25,38]. A study showed that the gray matter density of patients with T1D was less than the control group and this finding correlated with severe hypoglycemic attacks and higher HbA1c levels. This assessment was performed with voxel-based morphometry - a well-known quantitative MRI technique[25,38].

The direction of water diffusion in tissues is measured by using diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) that is an index for the integrity of white matter[25]. DT1 shows microstructural abnormalities particularly in the optic radiations and posterior corona radiata in T1D patients. These findings correlate with longstanding diabetes and high concentrations of HbA1c[39]. These abnormalities may be the underlying pathogenesis in the mental slowing that is the main cognitive problem in T1D[40]. DT1 Technique will be a good research tool for future studies in this setting.

There is a relationship between T2D and lacunar infarcts/cerebral Atrophy. This association between T2D and white matter lesions is less clear[37]. It was reported that hippocampal atrophy is a consistent neuroimaging finding in patients with T2D[41], but a relatively recent study that evaluated the data from one cohort study and two case control studies, concluded that these patients did not have any specific vulnerability to hippocampal atrophy. Nevertheless; they have greater global brain atrophy compared to controls[42].

DIABETES MELLITUS, AD AND INSULIN ROLE

T2D is a condition in that elevated blood glucose levels is resulted from increased glucose production by liver, reduced insulin production by pancreas and “insulin resistance” in which insulin responsiveness is decreased due to abnormal expression of the insulin receptors[43].

The idea that AD is a metabolic disease in which brain glucose utilization is impaired is supported by some evidences. Conversely; amyloid precursor protein (APP) and amyloid-β-peptide (Aβ) have been shown to induce mitochondrial activity defects and increase oxidative stresses that are able to impair key players of the glucose metabolic pathway[44,45].

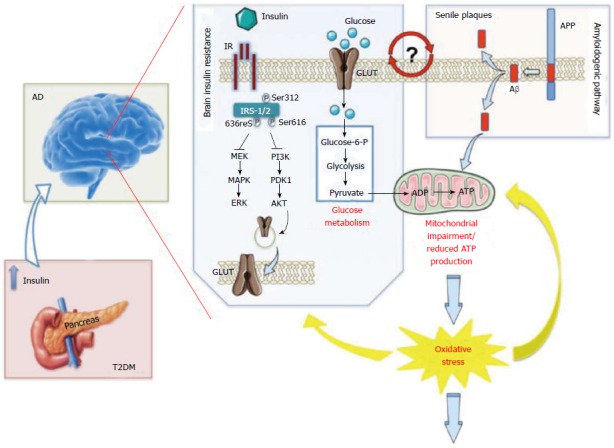

The prevalence of AD may be higher in patients with diabetes; however, the ORs are lower than those for vascular dementia[46]. In recent years; there are a number of studies that show a connection (via comparing pathologic samples) between T2D and AD. Scientists consider a key role for oxidative stress in development of AD in patients with diabetes Mellitus[43]. Diabetes Mellitus contributes to AD development by favoring tau hyperphosphorylation, accumulation of Aβ, increased oxidative stress and oxidative damage and mitochondrial dysfunction[44]. In this regard, the analysis of oxidation and damage of protein belonging to metabolic pathways (glucose metabolism) might be of interest in understanding the potential molecular mechanisms targeted by oxidative stress that trigger common features between T2D and AD. Different studies have shown that insulin resistance and reduced activation of insulin receptors with decreased neuronal plasticity mechanisms and survival are the main abnormalities in AD brain[43,47-49]. Figure 1 illustrated some aspects of this mechanism[43].

Figure 1.

Increased oxidative stress level as a central event driving insulin resistance in Alzheimer’ disease brain[43]. Persistently high levels of circulating insulin [as observed in the first phase of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM)] may exert a negative influence on memory and other cognitive functions by down regulation of insulin receptors (IR) at the blood brain barrier and consequent reduced insulin transport into the brain [as observed in Alzheimer’s disease (AD)], thus leading to insulin resistance. From a molecular point of view, the lack of interaction between insulin and IR is associated with an increase of the inhibitory phosphorylation on insulin receptor substrate-1/2 (IRS1/2) on Ser312, 616 and 636, which, in turn, negatively impacts on the two main arms of insulin-mediated signaling cascade: The PI3K and the MAPK pathways, both involved in the maintenance of synaptic plasticity and cell stress response. Furthermore, turning off insulin signaling results in impaired glucose transport (reduced translocation of the glucose transporter at the plasma membrane) and metabolism thus promoting an alteration of mitochondrial processes involved in energy production. In turn, impairment of mitochondria functions leads to a vicious circle in which reduced energy production is associated with an increase of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS and RNS) responsible for the oxidative/nitrosative damage of mitochondria as well as other cellular components. In addition, increased Aβ production and accumulation, which represents a key feature of AD pathology, also promotes mitochondrial impairment. Moreover, insulin resistance-associated impairments in glucose uptake and utilization are associated with increased endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, which deregulate lipid metabolism, causing accumulation of toxic lipids in the brain. All these events contribute to the increased oxidative stress levels responsible of neurodegeneration observed in AD brain. Although insulin resistance and Aβ production can be considered leading causes of the rise of oxidative stress, this latter, in turn, promotes IRS-1/2 Ser-312, -616 and -636 phosphorylation as well as the oxidative damage of protein involved in glycolysis, the Krebs cycle and ATP synthesis that are crucial events in the reduction of glucose metabolism and thus insulin resistance. Finally, because insulin resistance is associated with increased Aβ production and Aβ production is postulated to be responsible for the onset of insulin resistance, it remains to be clarified whether insulin resistance is a cause, consequence, or compensatory response to Aβ-induced neurodegeneration. ADP: Adenosine diphosphate; APP: β-Amyloid precursor protein; ATP: Adenosine triphosphate; AKT: Akt also known as protein kinase B (PKB); ERK: Extracellular signal-regulated kinase; GLUT: Glucose transporter; MAPK: Mitogen-activated protein kinase; MEK: MAPK/Erk kinase; PDK1: 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1; PI3K: Phosphoinositide 3 kinase.

T2D is a heterogeneous disorder that is accompanied with numerous comorbidities like hypertension and dyslipidemia, where each has the same adverse effects on the cognitive function[50]. In addition, other insulin resistance situations including obesity and metabolic syndrome are associated with a wide range of cognitive dysfunction and progression of AD[25,51].

Long term effects of insulin resistance consist of hypertension, malignancy and cardiovascular disease. It has been shown that insulin resistance has a negative correlation with verbal cognitive performance[25].

Thus, insulin resistance seems to be the fundamental feature that links T2DM to the future development of AD. The biochemical and molecular changes in AD is similar to the effects of NASH (nonalcoholic steatohepatitis) on the liver and T2D on the skeletal muscles[52]. Long term outcomes of insulin resistance include cellular energy defect, high plasma lipids and hypertension[52]. In Addition, chronic hyperinsulinemia predicts later development of T2M[53]. Insulin resistance is also a definite predictor of serious conditions such as cerebrovascular and cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, and malignancy[52]. Hyperinsulinemia is linked to some other diseases with different primary target organs include: Obesity, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, metabolic syndrome, polycystic ovarian disease, age-related macular degeneration. Overlap among these diseases often occurs and its rate is increasing with obesity epidemics[52].

INSULIN SIGNALING

There is significant amount of evidence demonstrating that dysregulation of insulin is a key element in triggering of neurodegeneration in T2D. Insulin binds to a specific receptor at blood brain barrier and transport into the CNS. It is shown that an acute increase in serum insulin levels is associated with an increase in CSF and intracellular insulin levels[54,55]. Also, it is reported that chronic hyperinsulinemia is associated with downregulation of insulin receptor at blood brain barrier[54] which decrease brain insulin levels and consequently trigger or accelerate the process of neural aging and neurodegeneration[54,55]. Studies have shown that hyperinsulinemia causes an increase in Aβ levels as well as the inflammatory agents[56] and alter the metabolism of amyloid in the brain[46-57].

It seems, insulin has a neurotropic role in the brain. Insulin accomplishes this role by binding to insulin receptors on the cell surface. It is interesting that most of insulin receptors in the brain are on the surface of the cells, located in anatomical regions that are involved in memory formation. So it is postulated that insulin might play an important role in the memory system[54].

Insulin activates secondary messengers after binding to receptors. The most important of these secondary messengers are phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase and Akt[54]. Activation of Akt causes inhibition of GSK-3β, which is an important kinase that phosphorylates tau. In fact, it is shown that under normal conditions, insulin inhibits tau phosphorylation and tau fibril production and low CSF insulin levels are associated with an increased neurofibrillary tangles[54,55]. Neurofibrillary tangles load is the best pathological marker of severity of dementia in AD.

Additionally, it’s known that Aβ protein is degraded by several enzymes. The most important of these enzymes are neprilysin and insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE)[58]. Both insulin and Aβ protein can bind to IDE and it is shown that insulin has higher affinity to IDE[54]. It is shown that hyperinsulinemia might inhibits peripheral degradation of Aβ protein[59]. High level of Aβ protein can lead to an increase transport of this protein across blood brain barrier, which is shown to be associated with an increased production of senile plaques in the brain[59].

In conclusion, it is hypothesized that serum hyperinsulinemia is associated with lower level of insulin and higher level of Aβ protein in the brain, resulting in more neurofibrillary tangles, senile plaques, and possibly with impaired cognitive state.

IS AD A TYPE OF DIABETES MELLITUS?

AD is considered as type 3 diabetes by some investigators because the corner stone of pathogenesis of abnormalities in AD has strong similarity with T1D and T2D. Like T1D, insulin deficiency is a part of underlying mechanisms in AD and like T2D, AD is associated with insulin resistance in early stage of development[52,60,61]. Consequently, AD can be considered as the brain form of diabetes[52].

Nevertheless; Talbot et al[62], reported some evidence that considering AD as a type of diabetes is not completely true due to the following: First, hyperglycemia but not insulin resistance is the main key diagnostic feature of diabetes, and CSF glucose is not elevated in AD patients. Second, decreased glucose metabolism in the brain AD cases is not a direct consequence of brain insulin resistance. Instead of that, postsynaptic neurotransmission changes due to reduced insulin signaling are responsible for abnormal glucose metabolism in the AD brain. Third, brain insulin deficiency in the AD patients has not been established from the review of different studies, and only some of them have shown this decrement[62].

OTHER MECHANISM OF COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT IN DIABETES MELLITUS

Vascular etiology

T2D is a risk factor for atherosclerosis and small vessel disease, so it clearly increases the risk of multi-infarct dementia and mixed type dementia. Other risk factors of vascular disease contribute to the development of dementia in patients with T2D, probably by vascular involvement. It has been shown that in patients with T2D, presence of hypertension, signs of microvascular diseases such as lacuna, DR and microalbuminuria or macrovascular complications such as cerebral infarcts increase the risks of dementia[54,63].

Chronic inflammation

Chronic inflammation is present in many patients with diabetes and insulin resistance is associated with increased levels of inflammatory cytokines, which elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines are associated with the worsening of the cognition in patients with diabetes[46,64].

Genetic

Brain changes and reductions in cognitive scores are most pronounced in patients with diabetes who have the Apo E epsilon 4 allele. The genetic factors contribute to dementia in T2D[65].

THERAPEUTIC APPROACHES

According to the long term prospective studies, good control of diabetes is beneficial in the reduction of cognitive decline in T1D[25,29], but the effect of this approach in T2D is controversial[66-70]. In one cohort study, there was a greater decline in cognitive impairment in patients on anti-diabetic medications and combination therapy was more effective than monotherapy[69].

One substudy of the ACCORD trial that followed up a large number of diabetic patients for 40 mo, showed no benefits from aggressive glucose control on the cognitive function[70]. In addition; three trials showed that intensive glycemic control has no benefit on the macrovascular events in T2D[66-68].

Association between cognitive decline and hypoglycemic attacks has been studied in some trials but the results are different. Overall, it seems that it is not a risk factor in T2D in carefully managed follow up studies. However, the prevention from hypoglycemia in the elderly is necessary, because it can cause more severe organic brain damage due to pre-existing atherosclerosis[71]. Also, it is true that, hypoglycemia may be a risk factor in children with diagnosed T1D within the first few years of life[25]. However, recurrent severe hypoglycemia is a significant preventable risk factor in these age groups and individualization of treatment, especially in the elderly, has a potential role in preventing hypoglycemia and consequently cognitive decline. While diabetes per se has a major impact on the elderly, the medications and the risk of hypoglycemia prevent optimization of glycemic treatment[72].

In one study, daily acute glucose fluctuation was an independent factor for cognitive dysfunction in T2D[73]. In another study, there was an association between cognitive impairment and postprandial hyperglycemia. There was a greater decline in cognitive impairment after adjusting for postprandial hyperglycemia[74].

The thiazolidinedione classes of anti-diabetic medications are insulin sensitizers that work by making the cells more sensitive to insulin. Most of the research has focused on the effect of thiazolidinedione on improvement of cognitive function. The findings suggest that there is continuous beneficial effect of insulin sensitizers on cognition. Its effect is more pronounced on neuron action by reduction of apoptosis, protecting neurons from oxidative stress and reducing plaque formation and inflammation in mice brain models. Despite these findings, clinical trials in human are disappointing[10].

Insulin action has a contributing factor in cognitive function. Both insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia are associated with cognitive impairment[71]. Excessive hyperinsulinemia exacerbates inflammation. Hyperinsulinemia enhances neurotic plaque formation[75]. Insulin secretion reduction is also associated with the onset of AD. Insulin definitively is connected with AD pathology and vascular dementia[76].

Intranasal insulin was effective in the improvement of memory function in memory impaired adults, in some studies[9]. Indeed, about 50% of all adults older than 60 years, even in the absence of diabetes, are insulin resistant[56]. It seems insulin puts its effect on cognitive function by modulation in aggregation of APP metabolites like beta amyloid peptide in neurotic plaques. On the other hand, factors associated with insulin resistance are suggested to be important in pathogenesis of AD. As it has been shown, Apo E negative patients are less sensitive to insulin which makes them in need for a higher level of insulin to facilitate an effective memory function in AD[77].

To date, there are few clinical data on the efficacy of metformin in AD and because of conflicting results regarding the effect of metformin in the improvement or deterioration of cognitive impairment, it needs to be clarified by a clinical placebo- controlled trial[78].

Other than hyperglycemia, midlife hypertension, midlife obesity, smoking, depression, and physical inactivity are attributable risk factors in AD and a 25% reduction in all of these factors could reduce the number of dementia by up to 3 million[79]. Large scale studies have shown that: Good control on blood pressure and lipid profile as well as glucose control will prevent vascular disease progression[80].

CONCLUSION

There is strong evidence that diabetes increases the risk of cognitive impairment and dementia. Insulin signaling dysregulation may be an important contributing factor in AD pathogenesis. In addition, diabetes is a risk factor for atherosclerosis and small vessel disease. It clearly increases the risk of vascular dementia. Good control of diabetes is beneficial in the reduction of cognitive decline in T1D, but the effect of this approach in improving cognitive outcomes in T2D is weak. Therefore; optimal glycemic control in T1D, identification of diabetic risk factors, and prophylactic approach in T2D are very important in the Prevention of cognitive complications. Lifestyle intervention such as proper diet and physical activity is the most important approaches in this way.

As the brain dysfunction in AD could be the result of disturbance in glucose metabolism and its dysregulation regardless of the diabetic status, future research with focus on anti-diabetic medications may open a new horizon for the prevention and management of AD. In addition, due to similarity in molecular and biochemical base of T2M and AD, more investigations in the domain of insulin resistance spectrum disorders provide an opportunity to find novel treatment strategies. These new approaches will be based on the improvement in the understanding of the pathogenesis of these fundamentally related disorders.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A Special note of thanks to Dr. Sasan Dabiri, at Amir Alam Research Center and a faculty member of the Department of Otorhinolaryngology at Amir Alam Hospital, for his assistance with the revision and final organization that greatly improved the manuscript. We also thank Dr. Amirhossein Sabouri, and Dr. Aidin Jalilzadeh for their assistance in preparing the article.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: No potential conflicts of interest. No financial support.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Endocrinology and metabolism

Country of origin: Iran

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

Peer-review started: May 3, 2016

First decision: June 17, 2016

Article in press: August 8, 2016

P- Reviewer: Isik AT, Masaki T, Vorobjova T S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

References

- 1.Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1047–1053. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ott A, Stolk RP, van Harskamp F, Pols HA, Hofman A, Breteler MM. Diabetes mellitus and the risk of dementia: The Rotterdam Study. Neurology. 1999;53:1937–1942. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.9.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leibson CL, Rocca WA, Hanson VA, Cha R, Kokmen E, O’Brien PC, Palumbo PJ. Risk of dementia among persons with diabetes mellitus: a population-based cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145:301–308. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Curb JD, Rodriguez BL, Abbott RD, Petrovitch H, Ross GW, Masaki KH, Foley D, Blanchette PL, Harris T, Chen R, et al. Longitudinal association of vascular and Alzheimer’s dementias, diabetes, and glucose tolerance. Neurology. 1999;52:971–975. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.5.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oxford Dictionaries. Definition of cognition [accessed 2016 Feb 4] Available from: http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/cognition.

- 6.Brewer JB, Gabrieli JDE, Preston AR, Vaidya CJ, Rosen AC. Memory. In: Goetz CG, editor. Textbook of Clinical Neurology. 3rd ed. Saunders: Elsevier Inc; 2007. pp. 63–77. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hall JE. Guyton and Hall text book of medical physiology. 12th ed. Saunders: Elsevier Inc; 2010. pp. 714–727. [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. APA: Washington, DC; 2013. pp. 593–595. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Budson AE, Solomon PR. Memory Loss, Alzheimer’s Disease, and Dementia: A Practical Guide for Clinicians. 2nd ed. Elsevier: Elsevier Inc; 2016. pp. 145–154. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kravitz E, Schmeidler J, Schnaider Beeri M. Type 2 diabetes and cognitive compromise: potential roles of diabetes-related therapies. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2013;42:489–501. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biessels GJ, Strachan MW, Visseren FL, Kappelle LJ, Whitmer RA. Dementia and cognitive decline in type 2 diabetes and prediabetic stages: towards targeted interventions. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2:246–255. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70088-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janson J, Laedtke T, Parisi JE, O’Brien P, Petersen RC, Butler PC. Increased risk of type 2 diabetes in Alzheimer disease. Diabetes. 2004;53:474–481. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.2.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ravona-Springer R, Luo X, Schmeidler J, Wysocki M, Lesser G, Rapp M, Dahlman K, Grossman H, Haroutunian V, Schnaider Beeri M. Diabetes is associated with increased rate of cognitive decline in questionably demented elderly. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2010;29:68–74. doi: 10.1159/000265552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Folsom AR, Rasmussen ML, Chambless LE, Howard G, Cooper LS, Schmidt MI, Heiss G. Prospective associations of fasting insulin, body fat distribution, and diabetes with risk of ischemic stroke. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study Investigators. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:1077–1083. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.7.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Selvin E, Bolen S, Yeh HC, Wiley C, Wilson LM, Marinopoulos SS, Feldman L, Vassy J, Wilson R, Bass EB, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes in trials of oral diabetes medications: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:2070–2080. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.19.2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wessels AM, Lane KA, Gao S, Hall KS, Unverzagt FW, Hendrie HC. Diabetes and cognitive decline in elderly African Americans: a 15-year follow-up study. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:418–424. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feinkohl I, Keller M, Robertson CM, Morling JR, Williamson RM, Nee LD, McLachlan S, Sattar N, Welsh P, Reynolds RM, et al. Clinical and subclinical macrovascular disease as predictors of cognitive decline in older patients with type 2 diabetes: the Edinburgh Type 2 Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:2779–2786. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao Q, Roberts RO, Ding D, Cha R, Guo Q, Meng H, Luo J, Machulda MM, Shane Pankratz V, Wang B, et al. Diabetes is Associated with Worse Executive Function in Both Eastern and Western Populations: Shanghai Aging Study and Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;47:167–176. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ebady SA, Arami MA, Shafigh MH. Investigation on the relationship between diabetes mellitus type 2 and cognitive impairment. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2008;82:305–309. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2008.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qiu C, Sigurdsson S, Zhang Q, Jonsdottir MK, Kjartansson O, Eiriksdottir G, Garcia ME, Harris TB, van Buchem MA, Gudnason V, et al. Diabetes, markers of brain pathology and cognitive function: the Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility-Reykjavik Study. Ann Neurol. 2014;75:138–146. doi: 10.1002/ana.24063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moran C, Phan TG, Chen J, Blizzard L, Beare R, Venn A, Münch G, Wood AG, Forbes J, Greenaway TM, et al. Brain atrophy in type 2 diabetes: regional distribution and influence on cognition. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:4036–4042. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kooistra M, Geerlings MI, Mali WP, Vincken KL, van der Graaf Y, Biessels GJ. Diabetes mellitus and progression of vascular brain lesions and brain atrophy in patients with symptomatic atherosclerotic disease. The SMART-MR study. J Neurol Sci. 2013;332:69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2013.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Elderen SG, de Roos A, de Craen AJ, Westendorp RG, Blauw GJ, Jukema JW, Bollen EL, Middelkoop HA, van Buchem MA, van der Grond J. Progression of brain atrophy and cognitive decline in diabetes mellitus: a 3-year follow-up. Neurology. 2010;75:997–1002. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f25f06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luchsinger JA, Reitz C, Patel B, Tang MX, Manly JJ, Mayeux R. Relation of diabetes to mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:570–575. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.4.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCrimmon RJ, Ryan CM, Frier BM. Diabetes and cognitive dysfunction. Lancet. 2012;379:2291–2299. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roberts RO, Geda YE, Knopman DS, Christianson TJ, Pankratz VS, Boeve BF, Vella A, Rocca WA, Petersen RC. Association of duration and severity of diabetes mellitus with mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:1066–1073. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.8.1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cato MA, Mauras N, Ambrosino J, Bondurant A, Conrad AL, Kollman C, Cheng P, Beck RW, Ruedy KJ, Aye T, et al. Cognitive functioning in young children with type 1 diabetes. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2014;20:238–247. doi: 10.1017/S1355617713001434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ryan CM. Diabetes and brain damage: more (or less) than meets the eye? Diabetologia. 2006;49:2229–2233. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0392-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacobson AM, Ryan CM, Cleary PA, Waberski BH, Weinger K, Musen G, Dahms W. Biomedical risk factors for decreased cognitive functioning in type 1 diabetes: an 18 year follow-up of the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) cohort. Diabetologia. 2011;54:245–255. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1883-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ho N, Sommers MS, Lucki I. Effects of diabetes on hippocampal neurogenesis: links to cognition and depression. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37:1346–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patton N, Aslam T, Macgillivray T, Pattie A, Deary IJ, Dhillon B. Retinal vascular image analysis as a potential screening tool for cerebrovascular disease: a rationale based on homology between cerebral and retinal microvasculatures. J Anat. 2005;206:319–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2005.00395.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crosby-Nwaobi R, Sivaprasad S, Forbes A. A systematic review of the association of diabetic retinopathy and cognitive impairment in people with Type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;96:101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lesage SR, Mosley TH, Wong TY, Szklo M, Knopman D, Catellier DJ, Cole SR, Klein R, Coresh J, Coker LH, et al. Retinal microvascular abnormalities and cognitive decline: the ARIC 14-year follow-up study. Neurology. 2009;73:862–868. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b78436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liew G, Mitchell P, Wong TY, Lindley RI, Cheung N, Kaushik S, Wang JJ. Retinal microvascular signs and cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1892–1896. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hugenschmidt CE, Lovato JF, Ambrosius WT, Bryan RN, Gerstein HC, Horowitz KR, Launer LJ, Lazar RM, Murray AM, Chew EY, et al. The cross-sectional and longitudinal associations of diabetic retinopathy with cognitive function and brain MRI findings: the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) trial. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:3244–3252. doi: 10.2337/dc14-0502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crosby-Nwaobi RR, Sivaprasad S, Amiel S, Forbes A. The relationship between diabetic retinopathy and cognitive impairment. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:3177–3186. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Harten B, de Leeuw FE, Weinstein HC, Scheltens P, Biessels GJ. Brain imaging in patients with diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:2539–2548. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Musen G, Lyoo IK, Sparks CR, Weinger K, Hwang J, Ryan CM, Jimerson DC, Hennen J, Renshaw PF, Jacobson AM. Effects of type 1 diabetes on gray matter density as measured by voxel-based morphometry. Diabetes. 2006;55:326–333. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.02.06.db05-0520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kodl CT, Franc DT, Rao JP, Anderson FS, Thomas W, Mueller BA, Lim KO, Seaquist ER. Diffusion tensor imaging identifies deficits in white matter microstructure in subjects with type 1 diabetes that correlate with reduced neurocognitive function. Diabetes. 2008;57:3083–3089. doi: 10.2337/db08-0724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Franc DT, Kodl CT, Mueller BA, Muetzel RL, Lim KO, Seaquist ER. High connectivity between reduced cortical thickness and disrupted white matter tracts in long-standing type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2011;60:315–319. doi: 10.2337/db10-0598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gold SM, Dziobek I, Sweat V, Tirsi A, Rogers K, Bruehl H, Tsui W, Richardson S, Javier E, Convit A. Hippocampal damage and memory impairments as possible early brain complications of type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2007;50:711–719. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0602-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wisse LE, de Bresser J, Geerlings MI, Reijmer YD, Portegies ML, Brundel M, Kappelle LJ, van der Graaf Y, Biessels GJ. Global brain atrophy but not hippocampal atrophy is related to type 2 diabetes. J Neurol Sci. 2014;344:32–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Butterfield DA, Di Domenico F, Barone E. Elevated risk of type 2 diabetes for development of Alzheimer disease: a key role for oxidative stress in brain. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1842:1693–1706. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Butterfield DA. Oxidative stress in neurodegenerative disorders. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:1971–1973. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Markesbery WR. Oxidative stress hypothesis in Alzheimer’s disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 1997;23:134–147. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(96)00629-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meneilly GS, Tessier DM. Diabetes, Dementia and Hypoglycemia. Can J Diabetes. 2016;40:73–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rivera EJ, Goldin A, Fulmer N, Tavares R, Wands JR, de la Monte SM. Insulin and insulin-like growth factor expression and function deteriorate with progression of Alzheimer’s disease: link to brain reductions in acetylcholine. J Alzheimers Dis. 2005;8:247–268. doi: 10.3233/jad-2005-8304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Steen E, Terry BM, Rivera EJ, Cannon JL, Neely TR, Tavares R, Xu XJ, Wands JR, de la Monte SM. Impaired insulin and insulin-like growth factor expression and signaling mechanisms in Alzheimer’s disease--is this type 3 diabetes? J Alzheimers Dis. 2005;7:63–80. doi: 10.3233/jad-2005-7107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Talbot K, Wang HY. The nature, significance, and glucagon-like peptide-1 analog treatment of brain insulin resistance in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10:S12–S25. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van den Berg E, Kloppenborg RP, Kessels RP, Kappelle LJ, Biessels GJ. Type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia and obesity: A systematic comparison of their impact on cognition. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1792:470–481. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shanik MH, Xu Y, Skrha J, Dankner R, Zick Y, Roth J. Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia: is hyperinsulinemia the cart or the horse? Diabetes Care. 2008;31 Suppl 2:S262–S268. doi: 10.2337/dc08-s264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de la Monte SM. Relationships between diabetes and cognitive impairment. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2014;43:245–267. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dankner R, Chetrit A, Shanik MH, Raz I, Roth J. Basal-state hyperinsulinemia in healthy normoglycemic adults is predictive of type 2 diabetes over a 24-year follow-up: a preliminary report. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1464–1466. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Verdile G, Fuller SJ, Martins RN. The role of type 2 diabetes in neurodegeneration. Neurobiol Dis. 2015;84:22–38. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moreira PI, Duarte AI, Santos MS, Rego AC, Oliveira CR. An integrative view of the role of oxidative stress, mitochondria and insulin in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;16:741–761. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-0972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Craft S. Insulin resistance and Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis: potential mechanisms and implications for treatment. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2007;4:147–152. doi: 10.2174/156720507780362137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ninomiya T. Diabetes mellitus and dementia. Curr Diab Rep. 2014;14:487. doi: 10.1007/s11892-014-0487-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nalivaeva NN, Belyaev ND, Kerridge C, Turner AJ. Amyloid-clearing proteins and their epigenetic regulation as a therapeutic target in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:235. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gasparini L, Gouras GK, Wang R, Gross RS, Beal MF, Greengard P, Xu H. Stimulation of beta-amyloid precursor protein trafficking by insulin reduces intraneuronal beta-amyloid and requires mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2561–2570. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-08-02561.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Arab L, Sadeghi R, Walker DG, Lue LF, Sabbagh MN. Consequences of Aberrant Insulin Regulation in the Brain: Can Treating Diabetes be Effective for Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2011;9:693–705. doi: 10.2174/157015911798376334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang X, Zheng W, Xie JW, Wang T, Wang SL, Teng WP, Wang ZY. Insulin deficiency exacerbates cerebral amyloidosis and behavioral deficits in an Alzheimer transgenic mouse model. Mol Neurodegener. 2010;5:46. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-5-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Talbot K, Wang HY, Kazi H, Han LY, Bakshi KP, Stucky A, Fuino RL, Kawaguchi KR, Samoyedny AJ, Wilson RS, et al. Demonstrated brain insulin resistance in Alzheimer’s disease patients is associated with IGF-1 resistance, IRS-1 dysregulation, and cognitive decline. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:1316–1338. doi: 10.1172/JCI59903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Saczynski JS, Siggurdsson S, Jonsson PV, Eiriksdottir G, Olafsdottir E, Kjartansson O, Harris TB, van Buchem MA, Gudnason V, Launer LJ. Glycemic status and brain injury in older individuals: the age gene/environment susceptibility-Reykjavik study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1608–1613. doi: 10.2337/dc08-2300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Strachan MW. R D Lawrence Lecture 2010. The brain as a target organ in Type 2 diabetes: exploring the links with cognitive impairment and dementia. Diabet Med. 2011;28:141–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.03199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dore GA, Elias MF, Robbins MA, Elias PK, Nagy Z. Presence of the APOE epsilon4 allele modifies the relationship between type 2 diabetes and cognitive performance: the Maine-Syracuse Study. Diabetologia. 2009;52:2551–2560. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1497-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gerstein HC, Miller ME, Byington RP, Goff DC, Bigger JT, Buse JB, Cushman WC, Genuth S, Ismail-Beigi F, Grimm RH, et al. Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2545–2559. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Duckworth W, Abraira C, Moritz T, Reda D, Emanuele N, Reaven PD, Zieve FJ, Marks J, Davis SN, Hayward R, et al. Glucose control and vascular complications in veterans with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:129–139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Patel A, MacMahon S, Chalmers J, Neal B, Billot L, Woodward M, Marre M, Cooper M, Glasziou P, Grobbee D, et al. Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2560–2572. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wu JH, Haan MN, Liang J, Ghosh D, Gonzalez HM, Herman WH. Impact of antidiabetic medications on physical and cognitive functioning of older Mexican Americans with diabetes mellitus: a population-based cohort study. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13:369–376. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(02)00464-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Launer LJ, Miller ME, Williamson JD, Lazar RM, Gerstein HC, Murray AM, Sullivan M, Horowitz KR, Ding J, Marcovina S, et al. Effects of intensive glucose lowering on brain structure and function in people with type 2 diabetes (ACCORD MIND): a randomised open-label substudy. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:969–977. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70188-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kawamura T, Umemura T, Hotta N. Cognitive impairment in diabetic patients: Can diabetic control prevent cognitive decline? J Diabetes Investig. 2012;3:413–423. doi: 10.1111/j.2040-1124.2012.00234.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mathur S, Zammitt NN, Frier BM. Optimal glycaemic control in elderly people with type 2 diabetes: what does the evidence say? Drug Saf. 2015;38:17–32. doi: 10.1007/s40264-014-0247-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rizzo MR, Marfella R, Barbieri M, Boccardi V, Vestini F, Lettieri B, Canonico S, Paolisso G. Relationships between daily acute glucose fluctuations and cognitive performance among aged type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2169–2174. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Abbatecola AM, Rizzo MR, Barbieri M, Grella R, Arciello A, Laieta MT, Acampora R, Passariello N, Cacciapuoti F, Paolisso G. Postprandial plasma glucose excursions and cognitive functioning in aged type 2 diabetics. Neurology. 2006;67:235–240. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000224760.22802.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dandona P. Endothelium, inflammation, and diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2002;2:311–315. doi: 10.1007/s11892-002-0019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Matsuzaki T, Sasaki K, Tanizaki Y, Hata J, Fujimi K, Matsui Y, Sekita A, Suzuki SO, Kanba S, Kiyohara Y, et al. Insulin resistance is associated with the pathology of Alzheimer disease: the Hisayama study. Neurology. 2010;75:764–770. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181eee25f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Craft S, Asthana S, Cook DG, Baker LD, Cherrier M, Purganan K, Wait C, Petrova A, Latendresse S, Watson GS, et al. Insulin dose-response effects on memory and plasma amyloid precursor protein in Alzheimer’s disease: interactions with apolipoprotein E genotype. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003;28:809–822. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(02)00087-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Imfeld P, Bodmer M, Jick SS, Meier CR. Metformin, other antidiabetic drugs, and risk of Alzheimer’s disease: a population-based case-control study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:916–921. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ruis C, Biessels GJ, Gorter KJ, van den Donk M, Kappelle LJ, Rutten GE. Cognition in the early stage of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1261–1265. doi: 10.2337/dc08-2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gaede P, Lund-Andersen H, Parving HH, Pedersen O. Effect of a multifactorial intervention on mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:580–591. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]