Abstract

Pancreatic cancer is the fourth leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide. Extensive research has yielded advances in first-line treatment strategies, but there is no standardized second-line therapy. In this review, we examine the literature trying to establish a possible therapeutic algorithm.

Keywords: Nab-paclitaxel, Nal-iri, Pancreatic cancer, Second line, Algorithm

Core tip: Pancreatic cancer is an emerging disease. In this review a possible therapeutic algorithm for second line treatment is hypothesized.

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic cancer (PDA) is an emerging disease and is the fourth leading cause of cancer death worldwide[1]. The prognosis is very poor; the 5-year survival rate is 5%, and the life expectancy of patients with metastatic PDA is approximately 2.8-5.7 mo[2]. These poor outcomes are likely due to resistance to chemotherapy and PDA biology. PDA often presents with micro-metastatic lesions at diagnosis, which are subsequently confirmed by radiological evidence. The mechanisms underlying PDA development and progression have not been fully elucidated, hindering the development of therapeutic strategies for disease management. National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend 5-fluorouracil-oxaliplatin-irinotecan (FOLFIRINOX) or nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine as first-line therapy. Gemcitabine (alone or in combination) is recommended as second-line therapy, with capecitabine or fluoropyrimidine plus oxaliplatin as the final option[3]. In fact gemcitabine seems to be more effective than fluoropyrimidine[4]. Second-line therapy is not standardized and depends on patient performance status (PS) (which frequently worsens after first-line therapy), comorbidities, previous treatments, and residual toxicities. Notably, only 40% of patients can receive an additional line of therapy after the first treatment[5].

However, active treatment has been linked to improved outcomes in PDA compared to best supportive care (BSC)[6].

In this review, we focus on significant second-line studies and subsequently propose a therapeutic algorithm for PDA.

SECOND-LINE THERAPY

Although studies of efficient target therapies are promising, the backbone of second-line strategies for PDA involves a combination of chemotherapeutic agents. Currently, gemcitabine-based chemotherapy or fluoropyrimidine-based therapy, depending on previous drug regimens, remains the standard of care in the second-line setting.

Target therapy

PDA is a heterogeneous cancer and identifying plausible therapeutic targets is consequently difficult. The efficacy of a variety of drugs targeting different pathways has been evaluated, including targets in angiogenesis, farnesyl-transferases, cancer stem cells, hyaluronic acid, EGFR-MEK, m-TOR, and JAK-STAT pathways. Bevacizumab has been investigated in PDA therapy due to the favourable results achieved in other gastrointestinal cancers. Although the addition of bevacizumab to gemcitabine in first-line therapy failed to improve overall survival (OS), it has been evaluated in second-line settings. A small randomized trial comparing bevacizumab monotherapy to the combination of bevacizumab (10 mg-kg q14) plus docetaxel (35 mg-m2 day 1.8.15 q 28) reported a detrimental effect of combination therapy[7]. The only targeted therapy approved by the Food and Drug Administration for PDA treatment is erlotinib. This drug produced a small advantage in first-line treatment and also demonstrated activity (4.1 mo in OS) in second-line treatment[8]. However, the combination of erlotinib with bevacizumab failed to improve patient outcomes[9].

The EGFR and VEGFR pathways play major roles in PDA carcinogenesis and have been investigated as potential targets for second-line treatment. Inhibition of MEK1/2 by selumetinib failed to improve OS in gemcitabine-refractory patients compared to capecitabine[10], most likely due to activation of the EGFR pathway. On the contrary, a phase II trial with a small sample size, demonstrated that the combination of erlotinib and selumetinib achieved better outcomes (7.3 mo OS)[11]. The EGFR inhibitor gefitinib failed to produce satisfactory results when used in combination with docetaxel using different schedules[12,13]. The JAK-STAT inhibitor ruxolitinib achieved promising outcomes in preclinical and phase II trials[14], but the subsequent phase III trial was terminated prematurely due to inefficacy. Instead encouraging results (median OS 9.8 mo) were reported with the use of olaparib, a poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor, in BRCA1 and BRCA2 (BRCA1/2) mutated patients prior exposed to at least one line of therapy[15]. Reni et al[16] investigated the maintenance with sunitinib in advanced PDA not progressed after six months of first line therapy, reporting an interesting result: An high 2-year OS, 22.9% vs 7.1% with sunitinib and placebo respectively.

Immunotherapy

Recent studies have focused on the new and attractive field of immunotherapy, which has achieved excellent results in the treatment of other malignancies. A variety of strategies had been tested in the following therapeutic settings: Vaccines, immune checkpoint blockade, anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocytes-associate protein 4 inhibitors, anti-PD-1 and anti-PDL1 inhibitors, and oncolytic virotherapy[17]. Good outcomes have not been obtained, most likely due to the immune suppressive nature of the PDA microenvironment, which is characterized by desmoplastic reactions. Predictive biomarkers are not available but are actively being sought[17].

Chemotherapy

Extensive data on potential treatments for gemcitabine-refractory patients are available because gemcitabine was previously the most frequently used agent for PDA. The roles of oxaliplatin and irinotecan in PDA have been evaluated due to the effectiveness of these drugs for other gastrointestinal cancers. Based on the promising results of a phase II trial[18], three phase III randomized studies have investigated the efficacy of oxaliplatin-based regimens in gemcitabine-refractory patients. The CONKO-01 trial compared the efficacy of oxaliplatin, folinic acid (LLV), and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) 24 h (OFF) with BSC. Although the patient cohort was small due to premature accrual closure, the study represents the first second-line trial demonstrating an advantage of chemotherapy over BSC (median OS 4.8 mo vs 2.3 mo). Patient randomization was terminated early because of the hesitation of the clinicians to administer BSC when a potentially active therapy was available[19].

Afterwards in the CONKO-003 trial the OFF arm was compared to an active control arm (5-FU). The results of this study confirmed OFF schedule efficacy. OS increased significantly in the experimental arm (5.9 mo vs 3.3 mo), and there was a low rate of adverse events[6]. These data are more reliable than those of the CONKO-01 trial because of the high number of randomized patients (168). Smaller, non-randomized studies reported similar results (approximately 5 mo in OS) for combination oxaliplatin-capecitabine (xelox)[20].

However, PANCREOX, which randomized 108 patients to oxaliplatin and 5-FU, the FOLFOX6m schedule, or 5-FU plus leucovorin, demonstrated a detrimental effect of FOLFOX6m on both OS and quality of life (median OS 6.1 mo vs 9.9 mo, P = 0.02), although the high OS in the 5-FU arm appears disputable[21].

Other schedules after progression to gemcitabine-based therapy have been investigated in non-randomized studies. The combination of oxaliplatin plus raltitrexed[22] or gemcitabine[23] led to OS of 5.2 and 6 mo, respectively. A recent small phase II study reported outstanding OS (10.4 mo) for the combination of oxaliplatin and docetaxel[24]. The use of docetaxel was suggested by the result of a previous retrospective trial that reported OS of 4.0 mo with docetaxel monotherapy[25]. By contrast, the combination of docetaxel with irinotecan yielded disappointing outcomes, with OS of 4.1 mo, comparable to the median OS for other schedules in this setting[26].

Limited experience with docetaxel[27], paclitaxel[28], and eribulin[29] monotherapies has not yielded satisfactory results.

Similar to oxaliplatin, irinotecan has been evaluated in association with other agents such as raltitrexed, resulting in OS of 6.5 mo[30]. Patients pre-treated with platinoid therapy frequently experienced peripheral neuropathy, limiting therapy options. Irinotecan monotherapy exhibited moderate activity and an acceptable safety profile as second-line treatment[31]. A subsequent multicentre phase II study was conducted to investigate the combination of irinotecan with fluoropyrimidine using the FOLFIRI schedule (irinotecan 180 mg/m2, leucovorin 200 mg/m2, 5-FU 400 mg/m2 bolus and 5-FU 600 mg/m2 for 22 h). This schedule was well tolerated and led to acceptable outcomes (OS 5 mo)[32].

Recent interesting data emerging from two relevant studies (PRODIGE 4, ACCORD 11) of FOLFIRINOX first-line therapy suggest an important impact of this schedule on OS; approximately 45% of patients underwent second-line therapy, despite the high rate of adverse events in the experimental arm compared to the gemcitabine control arm, including febrile neutropenia (5.4% vs 1.2%), neutropenia (45.7% vs 21%) and diarrhoea grade 3-4 (12.7% vs 1.8%)[33].

The optimal treatment choice after FOLFIRINOX progression has not been established. The PRODIGE intergroup reported the most common second-line therapy administered to patients progressing in the FOLFIRINOX arm was gemcitabine (82.5%) or a gemcitabine-based combination (12.5%). Conversely, in the gemcitabine-resistant group, the second-line treatment was FOLFOX (49.4%), gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin (17.6%), fluorouracil and leucovorin plus cisplatin (16.5%) or FOLFIRINOX (4.7%)[34]. Studies have also investigated nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine[35,36] and gemcitabine alone[37] after first-line FOLFIRINOX. In gemcitabine-refractory patients, second-line therapy with FOLFIRINOX is marginally effective and less manageable in terms of toxicities[38].

The most accepted hypothesis explaining rapid PDA progression during chemotherapy is the presence of a dense stroma surrounding the tumour cells that prevents drug activity. To overcome this obstacle, a new formulation of paclitaxel (nab-paclitaxel) was used in combination with gemcitabine as a first-line regimen[39]. This combination exhibited activity in the second-line setting both in gemcitabine-refractory patients[40,41] and after progression on FOLFIRINOX[42]. Nab-paclitaxel exhibited a clinical benefit and is also feasible in elderly patients[43]. Based on these results, irinotecan encapsulated in liposome nanoparticles was evaluated. A phase II trial of nanoliposomal irinotecan (nal-iri) monotherapy reported OS of 5.2 mo[44]. The phase III study (NAPOLI-1) randomized (1:1:1) 417 patients worldwide to nanoliposomal irinotecan monotherapy, 5-FU and leucovorin, or nanoliposomal irinotecan plus 5-FU and leucovorin. The reported median OS was 4.9, 4.2 and 6.1 mo, respectively[45]. This multicentre study had a large accrual, and nanoliposomal irinotecan plus 5-FU and leucovorin achieved the highest OS reported (Tables 1 and 2). Nanoliposomal irinotecan monotherapy was comparable to the combination of other chemotherapy agents.

Table 1.

Randomized second line studies

| Ref. | Year | Study | Regimens | Patients | OS (mo) |

| Pelzer et al[19] | 2011 | CONKO-01 | OFF vs BSC | 23 | 4.8 vs 2.3 |

| Oettle et al[6] | 2014 | CONKO-003 | OFF vs 5-FU | 76 | 5.9 vs 3.3 |

| Wang-Gillam et al[45] | 2015 | NAPOLI 1 | Nal-iri + 5-FU + LLV vs Nal-iri vs 5-FU + LLV | 417 | 6.1 vs 4.9 vs 4.2 |

| Ulrich-Pur et al[30] | 2003 | Raltitrexed + irinotecan vs raltitrexed | 38 | 6.5 vs 4.3 |

BSC: Best supportive care; 5-FU: 5-fluorouracil; OS: Overall survival; LLV: L-leucovorin.

Table 2.

Most significant not randomized second line studies

| Ref. | Year study | Regimens | Patients | OS (mo) |

| Reni et al[22] | 2006 | Oxaliplatin + Raltitrexed | 41 | 5.2 |

| Demols et al[23] | 2006 | Oxaliplatin + Gemcitabine | 33 | 6 |

| Saif et al[25] | 2010 | Docetaxel | 17 | 4 |

| Yi et al[31] | 2009 | Irinotecan | 33 | 6.6 |

| Zaniboni et al[32] | 2012 | Folfiri | 50 | 5 |

| Bertocchi et al[40] | 2015 | Abraxane + gemcitabine | 23 | 5 |

OS: Overall survival.

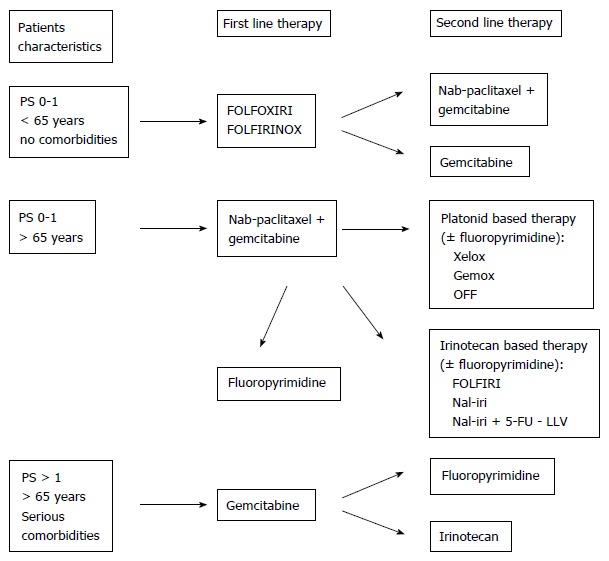

All available agents have been tested in PDA therapy in different combinations and schedules. However, as in other cancers, the sequence of treatments and the optimization of the few efficient agents are critical. Therefore, it is very important to define an algorithm based on PS, patient age, and comorbidities for the first line decision (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proposed algorithm of pancreatic cancer therapy. 5-FU: 5-fluorouracil; LLV: L-leucovorin.

To determine the first-line therapy, patients can be classified into three categories depending on age, PS, and comorbidities: Patients with PS 0-1 and < 65 years can be treated with FOLFIRINOX; patients with PS 0-1 and > 65 years can receive nab-paclitaxel; and patients with PS > 1 elderly patients, or patients with serious comorbidities receive gemcitabine monotherapy. The selection of subsequent therapies is affected by previous treatment and depends on residual toxicities, PS after first-line therapy, and patient preference.

Based on the literature, we hypothesize that patients treated with FOLFIRINOX can receive nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine or gemcitabine monotherapy. However, patients treated with first-line gemcitabine have additional options, including fluoropyrimidine and irinotecan.

There are currently no studies assessing treatment progression following nab-paclitaxel. However, if the patient recovers from peripheral neurotoxicity, we suggest platinoid-based chemotherapy or irinotecan-based therapy. A recent post hoc analysis of the MPACT trial showed that second-line therapy is feasible and more beneficial in patients previously treated with an efficient first-line treatment, particularly nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine, than in patients treated with gemcitabine alone[46].

Improved outcomes may be obtained by treatment with all active agents (nab-paclitaxel, gemcitabine, irinotecan, oxaliplatin, fluoropyrimidine) during the entire patient history.

CONCLUSION

Many drugs have been investigated for PDA treatment, but outstanding OS results have only recently been obtained in the second-line setting. The median OS remains approximately 5 mo that is a good results in comparison with that achieved by BSC. Current targeted therapies have not demonstrated efficacy in phase III trial, and future studies must strengthen the efficacy of current chemotherapy agents. Drugs such as nal-iri and nab-paclitaxel represent the first real change in this landscape and may provide new hope for PDA treatment.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they do not have any conflict of interest.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

Peer-review started: March 27, 2016

First decision: May 17, 2016

Article in press: July 18, 2016

P- Reviewer: Buanes TA, Kleeff J, Miyoshi E S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang FF

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carrato A, Falcone A, Ducreux M, Valle JW, Parnaby A, Djazouli K, Alnwick-Allu K, Hutchings A, Palaska C, Parthenaki I. A Systematic Review of the Burden of Pancreatic Cancer in Europe: Real-World Impact on Survival, Quality of Life and Costs. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2015;46:201–211. doi: 10.1007/s12029-015-9724-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN pancreatic guideline. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/pancreatic.pdf.

- 4.Burris HA, Moore MJ, Andersen J, Green MR, Rothenberg ML, Modiano MR, Cripps MC, Portenoy RK, Storniolo AM, Tarassoff P, et al. Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2403–2413. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.6.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smyth EN, Bapat B, Ball DE, André T, Kaye JA. Metastatic Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma Treatment Patterns, Health Care Resource Use, and Outcomes in France and the United Kingdom Between 2009 and 2012: A Retrospective Study. Clin Ther. 2015;37:1301–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2015.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oettle H, Riess H, Stieler JM, Heil G, Schwaner I, Seraphin J, Görner M, Mölle M, Greten TF, Lakner V, et al. Second-line oxaliplatin, folinic acid, and fluorouracil versus folinic acid and fluorouracil alone for gemcitabine-refractory pancreatic cancer: outcomes from the CONKO-003 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2423–2429. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.6995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Astsaturov IA, Meropol NJ, Alpaugh RK, Burtness BA, Cheng JD, McLaughlin S, Rogatko A, Xu Z, Watson JC, Weiner LM, et al. Phase II and coagulation cascade biomarker study of bevacizumab with or without docetaxel in patients with previously treated metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2011;34:70–75. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3181d2734a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Renouf DJ, Tang PA, Hedley D, Chen E, Kamel-Reid S, Tsao MS, Tran-Thanh D, Gill S, Dhani N, Au HJ, et al. A phase II study of erlotinib in gemcitabine refractory advanced pancreatic cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:1909–1915. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ko AH, Venook AP, Bergsland EK, Kelley RK, Korn WM, Dito E, Schillinger B, Scott J, Hwang J, Tempero MA. A phase II study of bevacizumab plus erlotinib for gemcitabine-refractory metastatic pancreatic cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2010;66:1051–1057. doi: 10.1007/s00280-010-1257-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bodoky G, Timcheva C, Spigel DR, La Stella PJ, Ciuleanu TE, Pover G, Tebbutt NC. A phase II open-label randomized study to assess the efficacy and safety of selumetinib (AZD6244 [ARRY-142886]) versus capecitabine in patients with advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer who have failed first-line gemcitabine therapy. Invest New Drugs. 2012;30:1216–1223. doi: 10.1007/s10637-011-9687-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ko AH, Bekaii-Saab T, Van Ziffle J, Mirzoeva OM, Joseph NM, Talasaz A, Kuhn P, Tempero MA, Collisson EA, Kelley RK, et al. A Multicenter, Open-Label Phase II Clinical Trial of Combined MEK plus EGFR Inhibition for Chemotherapy-Refractory Advanced Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:61–68. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brell JM, Matin K, Evans T, Volkin RL, Kiefer GJ, Schlesselman JJ, Dranko S, Rath L, Schmotzer A, Lenzner D, et al. Phase II study of docetaxel and gefitinib as second-line therapy in gemcitabine pretreated patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Oncology. 2009;76:270–274. doi: 10.1159/000206141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ignatiadis M, Polyzos A, Stathopoulos GP, Tselepatiotis E, Christophylakis C, Kalbakis K, Vamvakas L, Kotsakis A, Potamianou A, Georgoulias V. A multicenter phase II study of docetaxel in combination with gefitinib in gemcitabine-pretreated patients with advanced/metastatic pancreatic cancer. Oncology. 2006;71:159–163. doi: 10.1159/000106064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hurwitz HI, Uppal N, Wagner SA, Bendell JC, Beck JT, Wade SM, Nemunaitis JJ, Stella PJ, Pipas JM, Wainberg ZA, et al. Randomized, Double-Blind, Phase II Study of Ruxolitinib or Placebo in Combination With Capecitabine in Patients With Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer for Whom Therapy With Gemcitabine Has Failed. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:4039–4047. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.4578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaufman B, Shapira-Frommer R, Schmutzler RK, Audeh MW, Friedlander M, Balmaña J, Mitchell G, Fried G, Stemmer SM, Hubert A, et al. Olaparib monotherapy in patients with advanced cancer and a germline BRCA1/2 mutation. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:244–250. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.2728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reni M, Cereda S, Milella M, Novarino A, Passardi A, Mambrini A, Di Lucca G, Aprile G, Belli C, Danova M, et al. Maintenance sunitinib or observation in metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a phase II randomised trial. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:3609–3615. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ibrahim AM, Wang YH. Viro-immune therapy: A new strategy for treatment of pancreatic cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:748–763. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i2.748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Androulakis N, Syrigos K, Polyzos A, Aravantinos G, Stathopoulos GP, Ziras N, Mallas K, Vamvakas L, Georgoulis V. Oxaliplatin for pretreated patients with advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer: a multicenter phase II study. Cancer Invest. 2005;23:9–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pelzer U, Schwaner I, Stieler J, Adler M, Seraphin J, Dörken B, Riess H, Oettle H. Best supportive care (BSC) versus oxaliplatin, folinic acid and 5-fluorouracil (OFF) plus BSC in patients for second-line advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III-study from the German CONKO-study group. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:1676–1681. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blesa JG, Alberola-Candel B, Marco VG. Phase II trial of second line chemotherapy in metastatic pancreas cancer with the combination of oxaliplatin (OX) and capecitabine (CP) J Clin Oncol. 2009;27 suppl:abstr e15561. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gill S, Ko YJ, Cripps MC, BeauDOIn A, Dhesy-Thind SK, Zulfiqar M. PANCREOX: a randomised phase 3 study of 5FU/LV with or without oxaliplatin for second-line advanced pancreatic cancer (APC) in patients (pts) who have received gemcitabine (GEM)-based chemotherapy (CT) J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:abstr 4022. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.5776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reni M, Pasetto L, Aprile G, Cordio S, Bonetto E, Dell’Oro S, Passoni P, Piemonti L, Fugazza C, Luppi G, et al. Raltitrexed-eloxatin salvage chemotherapy in gemcitabine-resistant metastatic pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:785–791. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Demols A, Peeters M, Polus M, Marechal R, Gay F, Monsaert E, Hendlisz A, Van Laethem JL. Gemcitabine and oxaliplatin (GEMOX) in gemcitabine refractory advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a phase II study. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:481–485. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ettrich TJ, Perkhofer L, von Wichert G, Gress TM, Michl P, Hebart HF, Büchner-Steudel P, Geissler M, Muche R, Danner B, et al. DocOx (AIO-PK0106): a phase II trial of docetaxel and oxaliplatin as a second line systemic therapy in patients with advanced pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:21. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2052-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saif MW, Syrigos K, Penney R, Kaley K. Docetaxel second-line therapy in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a retrospective study. Anticancer Res. 2010;30:2905–2909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ko AH, Dito E, Schillinger B, Venook AP, Bergsland EK, Tempero MA. Excess toxicity associated with docetaxel and irinotecan in patients with metastatic, gemcitabine-refractory pancreatic cancer: results of a phase II study. Cancer Invest. 2008;26:47–52. doi: 10.1080/07357900701681483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cereda S, Reni M. Weekly docetaxel as salvage therapy in patients with gemcitabine-refractory metastatic pancreatic cancer. J Chemother. 2008;20:509–512. doi: 10.1179/joc.2008.20.4.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oettle H, Arnold D, Esser M, Huhn D, Riess H. Paclitaxel as weekly second-line therapy in patients with advanced pancreatic carcinoma. Anticancer Drugs. 2000;11:635–638. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200009000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Renouf DJ, Tang PA, Major P, Krzyzanowska MK, Dhesy-Thind B, Goffin JR, Hedley D, Wang L, Doyle L, Moore MJ. A phase II study of the halichondrin B analog eribulin mesylate in gemcitabine refractory advanced pancreatic cancer. Invest New Drugs. 2012;30:1203–1207. doi: 10.1007/s10637-011-9673-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ulrich-Pur H, Raderer M, Verena Kornek G, Schüll B, Schmid K, Haider K, Kwasny W, Depisch D, Schneeweiss B, Lang F, et al. Irinotecan plus raltitrexed vs raltitrexed alone in patients with gemcitabine-pretreated advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:1180–1184. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yi SY, Park YS, Kim HS, Jun HJ, Kim KH, Chang MH, Park MJ, Uhm JE, Lee J, Park SH, et al. Irinotecan monotherapy as second-line treatment in advanced pancreatic cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2009;63:1141–1145. doi: 10.1007/s00280-008-0839-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zaniboni A, Aitini E, Barni S, Ferrari D, Cascinu S, Catalano V, Valmadre G, Ferrara D, Veltri E, Codignola C, et al. FOLFIRI as second-line chemotherapy for advanced pancreatic cancer: a GISCAD multicenter phase II study. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2012;69:1641–1645. doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-1875-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gourgou-Bourgade S, Bascoul-Mollevi C, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouché O, Guimbaud R, Bécouarn Y, Adenis A, Raoul JL, Boige V, et al. Impact of FOLFIRINOX compared with gemcitabine on quality of life in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer: results from the PRODIGE 4/ACCORD 11 randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:23–29. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.4869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouché O, Guimbaud R, Bécouarn Y, Adenis A, Raoul JL, Gourgou-Bourgade S, de la Fouchardière C, et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1817–1825. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berger AK, Weber TF, Jäger D, Springfeld C. Successful treatment with nab-paclitaxel and gemcitabine after FOLFIRINOX failure in a patient with metastasized pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Onkologie. 2013;36:763–765. doi: 10.1159/000356811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Portal A, Pernot S, Tougeron D, Arbaud C, Bidault AT, de la Fouchardière C, Hammel P, Lecomte T, Dréanic J, Coriat R, et al. Nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma after Folfirinox failure: an AGEO prospective multicentre cohort. Br J Cancer. 2015;113:989–995. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.da Rocha Lino A, Abrahão CM, Brandão RM, Gomes JR, Ferrian AM, Machado MC, Buzaid AC, Maluf FC, Peixoto RD. Role of gemcitabine as second-line therapy after progression on FOLFIRINOX in advanced pancreatic cancer: a retrospective analysis. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2015;6:511–515. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2015.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kobayashi N. Second-line chemotherapy by FOLFIRINOX with unresectable pancreatic cancer (phase I, II study) J Clin Oncol. 2016;34 suppl 4S:abstr 297. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, Chiorean EG, Infante J, Moore M, Seay T, Tjulandin SA, Ma WW, Saleh MN, et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1691–1703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bertocchi P, Abeni C, Meriggi F, Rota L, Rizzi A, Di Biasi B, Aroldi F, Ogliosi C, Savelli G, Rosso E, et al. Gemcitabine Plus Nab-Paclitaxel as Second-Line and Beyond Treatment for Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer: a Single Institution Retrospective Analysis. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2015;10:142–145. doi: 10.2174/1574887110666150417115303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hosein PJ, de Lima Lopes G, Pastorini VH, Gomez C, Macintyre J, Zayas G, Reis I, Montero AJ, Merchan JR, Rocha Lima CM. A phase II trial of nab-Paclitaxel as second-line therapy in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2013;36:151–156. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3182436e8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Y, Hochster H, Stein S, Lacy J. Gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel for advanced pancreatic cancer after first-line FOLFIRINOX: single institution retrospective review of efficacy and toxicity. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2015;4:29. doi: 10.1186/s40164-015-0025-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Giordano G, Vaccaro V, Lucchini E, Musettini G, Bertocchi P, Bergamo F, Giommoni E, Santoni M, Russano M, Campidoglio S, et al. Nab-paclitaxel (Nab-P) and gemcitabine (G) as first-line chemotherapy (CT) in advanced pancreatic cancer (APDAC) elderly patients (pts): A “real-life” study. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33 suppl 3:abstr 424. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ko AH, Tempero MA, Shan YS, Su WC, Lin YL, Dito E, Ong A, Wang YW, Yeh CG, Chen LT. A multinational phase 2 study of nanoliposomal irinotecan sucrosofate (PEP02, MM-398) for patients with gemcitabine-refractory metastatic pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:920–925. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang-Gillam A, Li CP, Bodoky G, Dean A, Shan YS, Jameson G, Macarulla T, Lee KH, Cunningham D, Blanc JF, et al. Nanoliposomal irinotecan with fluorouracil and folinic acid in metastatic pancreatic cancer after previous gemcitabine-based therapy (NAPOLI-1): a global, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2016;387:545–557. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00986-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goldstein D, Chiorean GE, Tabernero J, Hassan R. Outcome of second-line treatment (2L Tx) following nab-paclitaxel (nab-P) gemcitabine (G) or G alone for metastatic pancreatic cancer (MPC) J Clin Oncol. 2016;34 suppl 4S:abstr 333. [Google Scholar]