Abstract

Objective

American Thyroid Association (ATA) low-risk papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) patients without structural evidence of disease on initial posttreatment evaluation have a low risk of recurrence. Despite this, most patients undergo frequent surveillance neck ultrasound (US). The objective of the study was to evaluate the clinical utility of routine neck US in ATA low-risk PTC patients with no structural evidence of disease after their initial thyroid surgery.

Methods

We performed a retrospective review of 171 ATA low-risk PTC patients after total thyroidectomy, with or without radioactive iodine (RAI) ablation, who had a neck US without suspicious findings after therapy. The main outcome measure was a comparison of the frequency of finding false-positive US abnormalities and the frequency of identifying structural disease recurrence.

Results

Over a median follow-up of 8 years, 171 patients underwent a median of 5 neck US (range 2–17). Structural recurrence with low-volume disease (≤1 cm) was identified in 1.2% (2/171) of patients at a median of 2.8 years (range 1.6–4.1 years) after their initial diagnosis. Recurrence was associated with rising serum thyroglobulin (Tg) level in 1 of the 2 patients and was detected without signs of biochemical recurrence in the other patient. Conversely, false-positive US abnormalities were identified in 67% (114/171) of patients after therapy, leading to additional testing without identifying clinically significant disease.

Conclusion

In ATA low-risk patients without structural evidence of disease on initial surveillance evaluation, routine screening US is substantially more likely to identify false-positive results than clinically significant structural disease recurrence.

INTRODUCTION

For the determination of risk of recurrence, the American Thyroid Association (ATA) classifies patients as low risk if they have the following characteristics: no local or distant metastases; all macroscopic tumor has been resected; no tumor invasion of locoregional tissues or structures; the tumor does not have aggressive histology or vascular invasion; and, if 131I is given, there is no 131I uptake outside the thyroid bed on the first posttreatment whole-body radioactive iodine (RAI) scan (1). The initial risk of recurrence for ATA low-risk patients treated with total thyroidectomy and RAI remnant ablation is as low as 2 to 3% in the first decade of follow-up (1). After taking into consideration the response to initial therapy, the risk of recurrence in those patients who demonstrate an excellent or indeterminate treatment response remains low at 0 to 2%, whereas the risk of recurrence increases to 13% in patients with an incomplete treatment response in the initial study by Tuttle et al (2).

The ATA recommends that a neck ultrasound (US) should be performed 6 to 12 months after surgery to establish the patient’s response to therapy and then periodically depending on the patient’s risk for recurrent disease and serum thyroglobulin (Tg) status, with no definite surveillance duration and frequency recommendation (1). The European Thyroid Association (ETA) does not recommend annual surveillance US for ETA very low-risk and ETA low-risk patients if the initial postsurgical neck US is negative and the serum thyroglobulin (Tg) is undetectable (3). The ETA recommends a repeat US with a basal serum Tg in these patients at 5 to 7 years after initial therapy (4). In practice, most ATA low-risk thyroid cancer patients in the United States still undergo surveillance neck US examinations annually or even more frequently for at least the first 5 years of follow-up regardless of their treatment response.

We previously described that neck US was more likely to identify false-positive abnormalities than clinically significant disease in ATA intermediate-risk papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) patients treated with total thyroidectomy and RAI ablation with no evidence of disease on their initial postsurgical evaluation (5). However, the utility of routine surveillance neck US and the frequency of finding false-positive US abnormalities in ATA low-risk thyroid cancer patients treated with total thyroidectomy, with or without RAI, has not been evaluated. The objective of this study was to evaluate the clinical utility of routine neck US in ATA low-risk PTC patients with no structural evidence of disease after initial thyroid surgery. We hypothesize that frequent neck US would result in even more false-positive abnormalities in these patients with a very low risk of recurrence.

METHODS

After obtaining approval from our institutional review board, we conducted a retrospective analysis of the medical records of 296 ATA low-risk patients with PTC treated with total thyroidectomy, with or without RAI ablation, who had serial neck US performed during their early follow- up with endocrinologists and head and neck surgeons at our institution between January 1994 and January 2010.

For inclusion in the study, patients had to meet criteria for low risk of recurrence according to the ATA classification (1), in the absence of interfering anti-Tg antibodies (TgAb), with no suspicious findings on initial postoperative neck US. A total of 171 patients satisfied the inclusion criteria for data analysis.

Neck US Evaluation

US examinations were performed according to standard protocol that included grayscale and color Doppler US assessment of the thyroid bed and cervical lymph nodes in all neck compartments. Examinations were performed by technologists using the same protocol for neck surveillance and supervised by experienced attending radiologists, who reviewed images in real time. The US studies were performed with Siemens Acuson S2000 (Siemens Medical Solutions, Mountain View, CA), Siemens Acuson SEQUOIA (Siemens Medical Solutions), or the GE Logiq 9 (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK) units, using 8- to 15-MHz linear 15L8W transducers. All prior imaging and reports performed at our institution were available on our picture archiving and communication system at the time of the US examination. The technologists and attending radiologists reviewed prior images and reports before the patient left the department as per our practice.

US reports include size, shape, echogenicity, internal vascularity, presence of cystic changes, and microcalcifications of thyroid bed nodules and cervical lymph nodes. Size was defined as the largest diameter among the 3 dimensions provided. Echogenicity was characterized relative to strap muscles. Microcalcifications were defined as punctate bright echoes without acoustic shadowing. Avascular nodules had absent Doppler flow. In the US report, comment was made on change from prior studies when applicable.

The sonographic findings were classified as suspicious, atypical, or negative. We defined sonographically suspicious findings as a cervical lymph node with at least 1 of the following features: microcalcifications, cystic areas, peripheral or diffuse vascularity, or hyperechoic lymph node tissue (apart from the hilum) and thyroid bed nodules with at least 1 of the following features: microcalcifications or increased vascularity including those with either peripheral or intra-nodular vascular flow, as well as structurally progressive lesions regardless of size. We defined sonographically atypical findings as rounded cervical lymph nodes that lack a fatty hilum and are avascular or thyroid bed nodules that are avascular (4,6–10). We defined sonographically negative findings as a postoperative neck US with lymph nodes of normal morphology or with no thyroid bed nodules or lymph nodes.

Other Imaging Modalities Used to Investigate for Recurrence

The use of other cross-sectional imaging (computed tomography [CT] scan or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]), as well as functional imaging (RAI whole-body scan or 18-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography [18FDG-PET] scan) were obtained at the discretion of the treating clinician and were also reviewed. When iodine uptake was seen in the thyroid bed or lateral neck region, these lesions were presumed to show RAI avidity and were classified as such.

Laboratory Studies

All Tg values were measured using the Dynotest-TgS immunoradiometric assay (Brahms, Inc, Berlin, Germany) with functional sensitivity 0.6 ng/mL, normalized to Certified Reference Material (CRM) 457, and were confirmed using a Tg recovery assay (11). Anti-Tg antibodies were measured using a Siemens Immulite 2500 Chemistry Analyzer.

Clinical Follow-up

Patients were followed at 6- to 12-month intervals at the discretion of the attending physician based on the clinical course of the disease and the risk of recurrence of the individual patient. Surveillance testing included serum Tg measurement on TSH suppressive therapy and neck US. Since these patients were evaluated prior to our description of response to therapy risk assessment in 2010, most of these patients had serial US evaluations done without regard to specific response classification (excellent, indeterminate, incomplete) (2). A diagnostic whole-body scan and a stimulated Tg value were ordered when deemed appropriate by the attending physician. The study period was defined as the time from the diagnosis of thyroid cancer to the last available medical records obtained as part of continued observation.

Clinical Outcomes

A structural neck recurrence, defined as a newly identified locoregional metastases with or without abnormal Tg, was included as a clinical endpoint. The structural neck recurrence is based on histology or sonographically suspicious findings along with the impression of the attending physician.

Our prior description of response to therapy classified therapy response to be excellent, indeterminate, or incomplete (2). However, this did not take into account patients who had not undergone RAI ablation. As our current study includes patients treated with total thyroidectomy, with or without RAI ablation, we assessed response to therapy at each follow-up visit based on the modified classification by Momesso et al (13) that was designed to take into account the more sensitive Tg assay in clinical use, as well as the fact that not all patients will undergo RAI ablation. This classification categorizes the response to therapy to be excellent, indeterminate, biochemical incomplete, or structural incomplete. It is consistent with the modified terminology used to describe the response to therapy in the ATA 2015 thyroid cancer management guidelines. Patients were considered to have an excellent treatment response if they had nonstimulated serum Tg <0.2 ng/mL or stimulated serum Tg <1 ng/mL after RAI ablation (or stimulated serum Tg <2 ng/mL without RAI ablation), with no detectable TgAb, and no structural evidence of disease on neck US and/or cross-sectional or nuclear medicine imaging. Patients were considered to have an indeterminate response if they had a nonstimulated serum Tg between 0.2 and 1 ng/mL, stimulated serum Tg ≥1 to 10 ng/mL after RAI ablation (or nonstimulated serum Tg 0.2–5 ng/mL or stimulated serum Tg ≥2–10 ng/mL without RAI ablation), stable or declining TgAb, or nonspecific changes on neck US and/or cross-sectional or nuclear medicine imaging. Patients were considered to have biochemical incomplete treatment response if they had a nonstimulated serum Tg >1 ng/mL after RAI ablation (or nonstimulated serum Tg >5 ng/mL without RAI ablation), stimulated serum Tg >10 ng/mL with or without RAI ablation, or rising Tg or TgAb values without structural evidence of disease on imaging.

Patients dying of unrelated conditions had the final endpoint determined based on data available before their demise.

Atypical US abnormalities identified during follow-up evaluations that were stable and not determined to be structural disease recurrence (by cytology, histology, or RAI imaging) were considered to be false-positive findings. While we recognize that some of these stable atypical US findings could be small volume, stable or very slowly progressive PTC, we classified them as false positive for purposes of this study since they did not develop into clinically significant structural disease during a median follow-up period of 8 years.

Outcome of Thyroid Bed Nodules and Cervical Lymph Nodes

Each sonographically identified lesion was classified as either showing an increase in size or no increase in size. Growth was defined as an increase of at least 3 mm in the largest dimension when compared with the size of the nodule at initial detection. A 3-mm increase was selected because this is the minimal size change that can be reproducibly determined by high-resolution US while minimizing operator-dependent differences in size assessment (12). We chose to analyze the greatest dimension of lymph nodes because this is the size measurement most commonly used in clinical practice for decision making. However, we note that the ATA (1) and ETA (3,4) guidelines consider the smallest lymph node dimension in view of surgical considerations, as long and thin lymph nodes are difficult to locate intraoperatively. US reports of the cases, as well as US images, were reviewed by S.P.Y. US images showing structural progression or suspicious features were submitted for a review by S.F., who is a recognized specialist in thyroid US.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous data are presented as means and SDs or median and ranges, as appropriate for each variable. The Fisher exact or χ2 test was performed to assess for differences between 2 proportions. Analysis was performed using SPSS software (Version 18.0.1; SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL). A P value of ≤.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Initial Clinicopathologic Characteristics

The majority of the patients were female (147/171, 86%) with a median age of 42 years at diagnosis. The median follow-up duration was 8 years (range 2–42 years), and 58 patients (58/171, 34%) were monitored for ≥10 years (Table 1). Most patients (93/171, 54%) had classic PTC; 43% (73/171) had follicular variant PTC, and 4% (7/171) had tall cell variant/features PTC. Overall, 89% (152/171), 9% (15/171), and 2% (2/171) of patients had American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Stage I, II, and III disease, respectively. Based on the inclusion criteria for ATA low-risk patients, none had distant metastatic disease. The primary tumor size was small with a median diameter of 1.3 cm (range 0.1–9.0 cm). Initial therapy included total thyroidectomy without neck dissection in 98% (167/171), central neck dissection in 2% (3/171), and central and lateral neck dissection in <1% (1/171). Sixty-one percent of the patients did not receive RAI after total thyroidectomy. Of those patients who received RAI, the median administered dose was 99.6 mCi (range 28.0–193.0 mCi). The posttherapy whole-body scan showed only thyroid bed uptake in most of the patients (62/66, 94%).

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics

| Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Number of patients | 171 |

| Age at diagnosis (years) (median [range]) | 42 (18–81) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 147 (86%) |

| Male | 24 (14%) |

| Papillary thyroid carcinoma histologic variantsa | |

| Classic | 93 (54%) |

| Follicular variant | 73 (43%) |

| Tall cell variant/features | 7 (4%) |

| AJCC TNM stage | |

| I | 152 (89%) |

| II | 15 (9%) |

| III | 4 (2%) |

| IV | 0 (0%) |

| Size of primary tumor (in cm) | |

| Mean ± SD | 1.7 ± 1.3 |

| Median (range) | 1.3 (0.1–9.0) |

| Extent of neck dissection at thyroidectomy | |

| No neck dissectionb | 167 (98%) |

| Central neck dissection | 3 (2%) |

| Central and lateral neck dissection | 1 (<1%) |

| Radioactive iodine as part of initial therapy | |

| No | 105 (61%) |

| Yes | 66 (39%) |

| Mean dose ± SD (mCi) | 98.9 ± 34.3 |

| Median dose (range) (mCi) | 99.6 (28.0–193.0) |

| Follow-up duration (years) (median [range]) | 8 (2–42) |

Abbreviations: AJCC = American Joint Committee on Cancer.

Two patients had concomitant tall cell and follicular variant features and were included in both categories.

2 patients had lymph node biopsies with any neck dissection.

US and Clinical Outcome During Follow-up

Over a median follow-up of 8 years, the 171 ATA low-risk PTC patients underwent a median of 5 neck US (range 2–17 US). Two patients (2/171, 1.2%) developed suspicious US findings during surveillance with the size of the suspicious lesions measuring 0.7 to 1 cm. The disease was identified at a median of 2.8 years after surgery (range 1.6–4.1 years, Table 2). These 2 patients were both male, diagnosed with PTC over the age of 45, and did not receive RAI therapy as part of their initial treatment. They had atypical US findings on the initial postoperative neck US with an indeterminate treatment response (13). One of the patients had a rising serum Tg level that was a clinical indication for additional surveillance testing. In the absence of clinical indications for US examination, routine screening US identified structural disease recurrence in only 1 patient (1/170, 0.6%) at 4.1 years after surgery.

Table 2.

Clinical Features and Outcomes of 2 Patients With Suspicious US Findings

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | Male |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 58 | 70 |

| PTC histological class | Follicular variant | Classical |

| Tumor size (cm) | 3.5 | 0.2 |

| AJCC Stage | II | I |

| Initial RAI therapy | No | No |

| Therapy response (13) | Indeterminate | Indeterminate |

| Initial postoperative US finding | Atypical | Atypical |

| Size of suspicious lesion (cm) | 1.0 cm | 0.7 cm |

| Time after surgery to structural neck recurrence | 1.6 years | 4.1 years |

| Tg at baseline and at time of structural neck recurrence (ng/mL) | 0.8 at baseline to 1.5 at time of recurrence | 0.5 at baseline to 0.2 at time of recurrence |

| Indication for US | Rising Tg | Routine screening |

| Management | Delayed RAI | Observed |

Abbreviations: AJCC = American Joint Committee on Cancer; RAI = radioactive iodine; PTC = papillary thyroid cancer; Tg = thyroglobulin; US = ultrasound.

Neither patient underwent a biopsy of the suspicious lesion. One of the 2 patients who developed a suspicious right level IV cervical lymph node during follow-up received delayed 131I therapy, with the posttherapy whole-body scan showing thyroid bed uptake. This patient continued to have atypical findings on US without progression. The other patient had stable low-volume disease with a suspicious thyroid bed nodule and was observed without additional treatment.

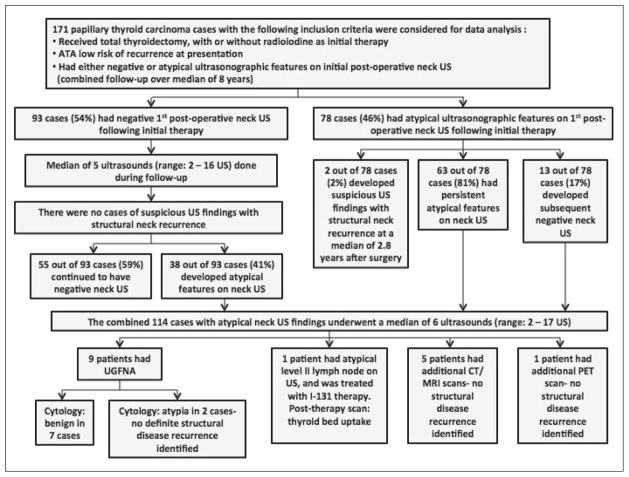

Ninety-three patients (93/171, 54%) had a negative initial postoperative neck US. After undergoing a median of 5 neck US (range 2–16 US), none of these patients developed structural recurrence during follow-up. Fifty-five patients (55/93, 59%) continued to have a negative neck US, and 38 patients (38/93, 41%) developed atypical findings on subsequent neck US, without any definite evidence of progressive structural disease identified.

Seventy-eight patients (78/171, 46%) had atypical findings on the initial postoperative neck US. Of these, 63 patients (63/78, 81%) continued to have atypical findings on serial neck US, and 13 (13/78, 17%) had a subsequent negative neck US (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Summary of ultrasonographic findings and clinical course of the study cohort.

Overall, 114 patients (114/171, 67%) had atypical findings either on initial postoperative neck US or on subsequent surveillance neck US. Most of these patients (90/114, 79%) with atypical US findings had nonstimulated serum Tg <0.2 ng/mL or stimulated serum Tg <1 ng/ mL after RAI ablation (or stimulated serum Tg <2 ng/mL without RAI ablation), with no detectable TgAb. These sonographic findings led to a median of 6 neck US evaluations during follow-up (range 2–17 US). In addition, 5 patients had CT/MRI scans, 1 patient had a PET scan, and 9 patients underwent biopsy under US-guidance with benign cytologic results in 7 cases, and atypia in 2 cases. One patient with an atypical level II lymph node on US was treated with delayed I-131 therapy with the posttherapy whole body scan showing thyroid bed uptake only, and an excellent treatment response on subsequent testing (Fig. 1). These further investigations did not identify any definite evidence of structural disease.

Review of the Effect of Initial Radioiodine Therapy on US and Clinical Outcomes

The distribution of patients with postoperative normal or atypical US findings, as well as the therapy response category (13), were similar with or without RAI as part of the initial therapy (Table 3). As ATA low-risk PTC patients without structural evidence of persistent disease had been recruited, a large proportion of the cohort had excellent treatment responses, and none had structural incomplete treatment response. Therefore, RAI therapy did not appear to affect the outcome in these low-risk patients.

Table 3.

Stratification of Follow-up Neck US Findings and Best Therapy Response According to Initial RAI Therapy Status

| Patients who received initial RAI (n = 66) | Patients who did not receive initial RAI (n = 105) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neck US findings | Had negative initial US findings | 39 (59%) | 54 (51%) | >.05 |

| Had atypical initial US findings | 27 (41%) | 51 (49%) | ||

| Response to therapy (13) | Excellent | 34 (51.5%) | 49 (46.7%) | >.05 |

| Biochemical Incomplete | 1 (1.5%) | 2 (1.9%) | >.05 | |

| Indeterminate | 31 (47.0%) | 54 (51.4%) | >.05 | |

| Structural Incomplete | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | … |

Abbreviations: RAI = radioactive iodine; US = ultrasound.

DISCUSSION

We reviewed the records of 171 patients with ATA low-risk PTC treated with total thyroidectomy with or without RAI who did not have any suspicious sonographic findings on their initial postoperative neck US. Consistent with our previous study (2), the overall rate of structural disease recurrence was 1.2% (2/171) over a median follow- up of 8 years (range 2–42 years), with one-third of the patients being followed for ≥ 10 years. Importantly, in the absence of other clinical indicators of disease recurrence, routine screening neck US identified structural disease in only 0.6% (1/170) of patients at a median of 4.1 years after surgery. In the second patient who developed structural recurrence, the disease would have been detected due to clinical indicators without the use of regular surveillance neck US. Furthermore, only low-volume disease (range 0.7–1 cm) was identified, which is unlikely to be clinically significant. The stable clinical course of these lesions over time suggests that in these low-risk patients, new suspicious US lesions ≤1 cm can be monitored for growth without a biopsy or any intervention. Conversely, 114 out of 171 patients (67%) had atypical neck US findings on initial postoperative or subsequent surveillance US, without evidence of progressive structural disease. Routine neck US identified many false-positive results that led to a wide variety of tests and procedures without identifying clinically significant disease. Avascular thyroid bed nodules were the most common atypical finding on neck US. These lesions likely represent postoperative scar tissue or a small amount of residual normal thyroid tissue. In our practice, these nodules were monitored without biopsy unless the nodule developed progressive suspicious sonographic features over time. Among patients with an initial negative postoperative neck US, none developed recurrent disease during surveillance. Thus, in this group of patients with a low risk of developing recurrent disease, frequent US monitoring in the first 5 years of follow-up was far more likely to result in nonspecific false-positive findings than to identify clinically significant structural disease recurrence.

One limitation of the study is the differences in US technology over the time period during which the patients were monitored from 1994 to 2010. These changes in technology might have affected the sensitivity for detecting suspicious US features in the earlier studies, which formed the basis for the initial classification of the patients in the study.

While we recognize that some of the atypical findings could eventually develop into clinically significant structural disease during long-term follow-up, our findings showed that the median time to the diagnosis of structural recurrence was 2.8 years after surgery (range 1.6–4.1 years), and no additional cases of structural recurrence were detected after 4.1 years of follow-up. In a study by Durante et al, the authors evaluated the time to recurrence in 1,020 PTC patients who underwent total thyroidectomy over a median follow-up of 10.4 years (range 5.1–20.4 years) (14). In their study cohort, 61% (625/1,020) of patients had ATA low-risk disease, and 88.4% (902/1,020) received RAI remnant ablation. Overall, 72 of the 1,020 (7.2%) patients had persistent structural disease. Out of the remaining 948 PTC patients who had negative post-operative imaging after total thyroidectomy, the overall recurrence rate was 1.4% (13/948), similar to the recurrence rate of 1.2% (2/171) that was observed in our study. They reported that all of the recurrences were diagnosed <8 years (range 1.2–7.7 years) after initial therapy (14). In another study, Durante et al (15) assessed the optimal postsurgical follow-up of 312 micropapillary thyroid cancer patients treated with total thyroidectomy with or without RAI remnant ablation over a median follow-up of 6.7 years (range 5–23 years). All of the patients had a negative initial and final postoperative neck US, and none of the cases required reoperation. They did not identify any cases of recurrent disease during surveillance. We previously described a cohort of ATA intermediate-risk PTC patients with no evidence of disease on initial follow-up evaluation. The incidence of recurrence was low and occurred at a median of 6.3 years after the last surgery (range 3.0–14.5 years) over a median follow-up of 10 years (range 2–15 years). We also showed that routine screening with neck US in these ATA intermediate-risk patients was more likely to identify false-positive abnormalities than clinically significant disease (5). The results of the current study with low-risk patients are similar. Furthermore, in our earlier studies, we observed that sonographically suspicious and atypical lymph nodes and thyroid bed nodules frequently remain stable for many years or grow slowly over 2 to 3 years (16,17). We postulate that after 10 years of follow-up in ATA low-risk patients that have no evidence of disease, further neck US is not required. However, additional longterm studies would be required to confirm this.

The ETA does not recommend routine surveillance neck US for very low-risk and low-risk patients if the initial surveillance neck US is negative and serum Tg is undetectable. In this group of patients, the ETA recommends that a final neck US can be performed 5 to 7 years after initial therapy (3,4). Data from our studies and the study by Durante et al (14) support the ETA recommendation for less frequent US surveillance in low-risk patients.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, neck US in the early years of follow-up in ATA low-risk PTC patients without evidence of structural disease on postoperative neck US is more likely to identify false positive results than true structural disease. Furthermore, routine US surveillance in the absence of clinical indications for recurrent disease rarely identifies clinically significant disease during follow-up. Therefore, we recommend surveillance neck US no more frequently than every 3 to 5 years in ATA low-risk patients with atypical, nonsuspicious findings on the initial postoperative neck US. If the initial postoperative neck US is negative, no further neck US is necessary in the absence of clinical indicators of recurrence. The frequency and timing of surveillance neck US should be individualized according to the risk of recurrence and response to therapy of all thyroid cancer patients.

Abbreviations

- 18FDG-PET

18-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission testing

- AJCC

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- ATA

American Thyroid Association

- CT

computed tomography

- ETA

European Thyroid Association

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- PTC

papillary thyroid cancer

- RAI

radioactive iodine

- Tg

thyroglobulin

- TgAb

antithyroglobulin antibodies

- TSH

thyroid-stimulating hormone

- US

ultrasound

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no multiplicity of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.American Thyroid Association (ATA) Guidelines Taskforce on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Cooper DS, Doherty GM, et al. Revised American Thyroid Association management guidelines for patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2009;19:1167–1214. doi: 10.1089/thy.2009.0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tuttle RM, Tala H, Shah J, Leboeuf R, et al. Estimating risk of recurrence in differentiated thyroid cancer after total thyroidectomy and radioactive iodine remnant ablation: using response to therapy variables to modify the initial risk estimates predicted by the new American Thyroid Association staging system. Thyroid. 2010;20:1341–1349. doi: 10.1089/thy.2010.0178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pacini F, Schlumberger M, Dralle H, et al. European consensus for the management of patients with differentiated thyroid carcinoma of the follicular epithelium. Eur J Endocrinol. 2006;154:787–803. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leenhardt L, Erdogan MF, Hegedus L, et al. 2013 European thyroid association guidelines for cervical ultrasound scan and ultrasound-guided techniques in the post-operative management of patients with thyroid cancer. Eur Thyroid J. 2013;2:147–159. doi: 10.1159/000354537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peiling Yang S, Bach AM, Tuttle RM, Fish SA. Frequent screening with serial neck ultrasound is more likely to identify false positive abnormalities than clinically significant disease in the surveillance of intermediate risk papillary thyroid cancer patients without suspicious findings on follow-up ultrasound evaluation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:1561–1567. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-3651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.LeBoulleux S, Girard E, Rose M, et al. Ultrasound criteria for malignancy for cervical lymph nodes in patients followed up for differentiated thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:3590–3594. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fish SA, Langer JE, Mandel SJ. Sonographic imaging of thyroid nodules and cervical lymph nodes. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2008;37:401–417. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shin JH, Han BK, Ko EY, Kang SS. Sonographic findings in the surgical bed after thyroidectomy: comparison of recurrent tumors and nonrecurrent lesions. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26:1359–1366. doi: 10.7863/jum.2007.26.10.1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ko MS, Lee JH, Shong YK, et al. Normal and abnormal sonographic findings at the thyroidectomy sites in post-operative patients with thyroid malignancy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194:1596–1609. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.2513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamaya A, Gross M, Akatsu H, et al. Recurrence in the thyroidectomy bed: sonographic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:66–70. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.4474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Persoon AC, Links TP, Wilde J, Sluiter WJ, Wolffenbuttel BH, van den Ouweland JM. Thyroglobulin (Tg) recovery testing with quantitative Tg antibody measurement for determining interference in serum Tg assays in differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Clin Chem. 2006;52:1196–1199. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.060103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ito Y, Miyauchi A, Inoue H, et al. An observational trial for papillary thyroid microcarcinoma in Japanese patients. World J Surg. 2010;34:28–35. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0303-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Momesso DP, Tuttle RM. Update on differentiated thyroid cancer staging. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2014;43:401–421. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2014.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Durante C, Montesano T, Torlontano M, et al. Papillary thyroid cancer: time course of recurrences during post-surgery surveillance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:636–642. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Durante C, Attard M, Torlontano M, et al. Identification and optimal postsurgical follow-up of patients with very low-risk papillary thyroid microcarcinomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:4882–4888. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rondeau G, Fish S, Hann LE, Fagin JA, Tuttle RM. Ultrasonographically detected small thyroid bed nodules identified after total thyroidectomy for differentiated thyroid cancer seldom show clinically significant structural progression. Thyroid. 2011;21:845–853. doi: 10.1089/thy.2011.0011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robenshtok E, Fish S, Bach A, Domínguez JM, Shaha A, Tuttle RM. Suspicious cervical lymph nodes detected after thyroidectomy for papillary thyroid cancer usually remain stable over years in properly selected patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:2706–2713. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]