Abstract

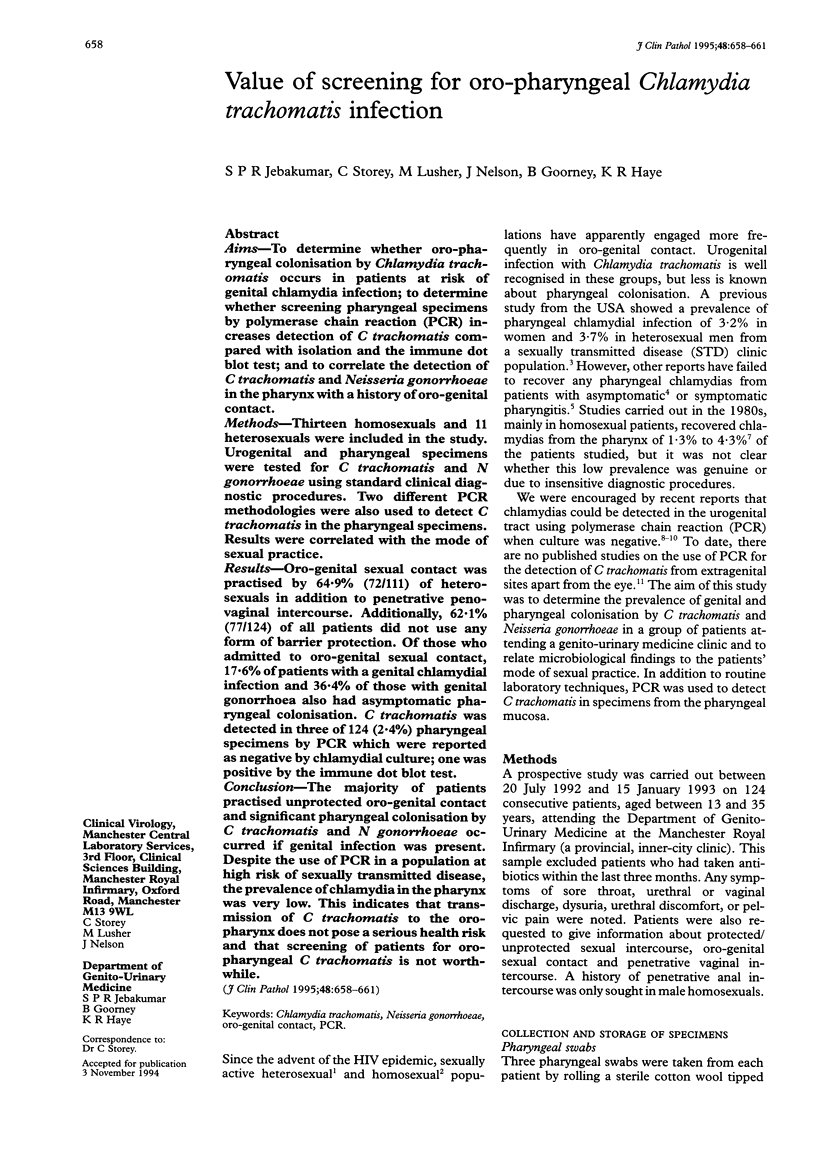

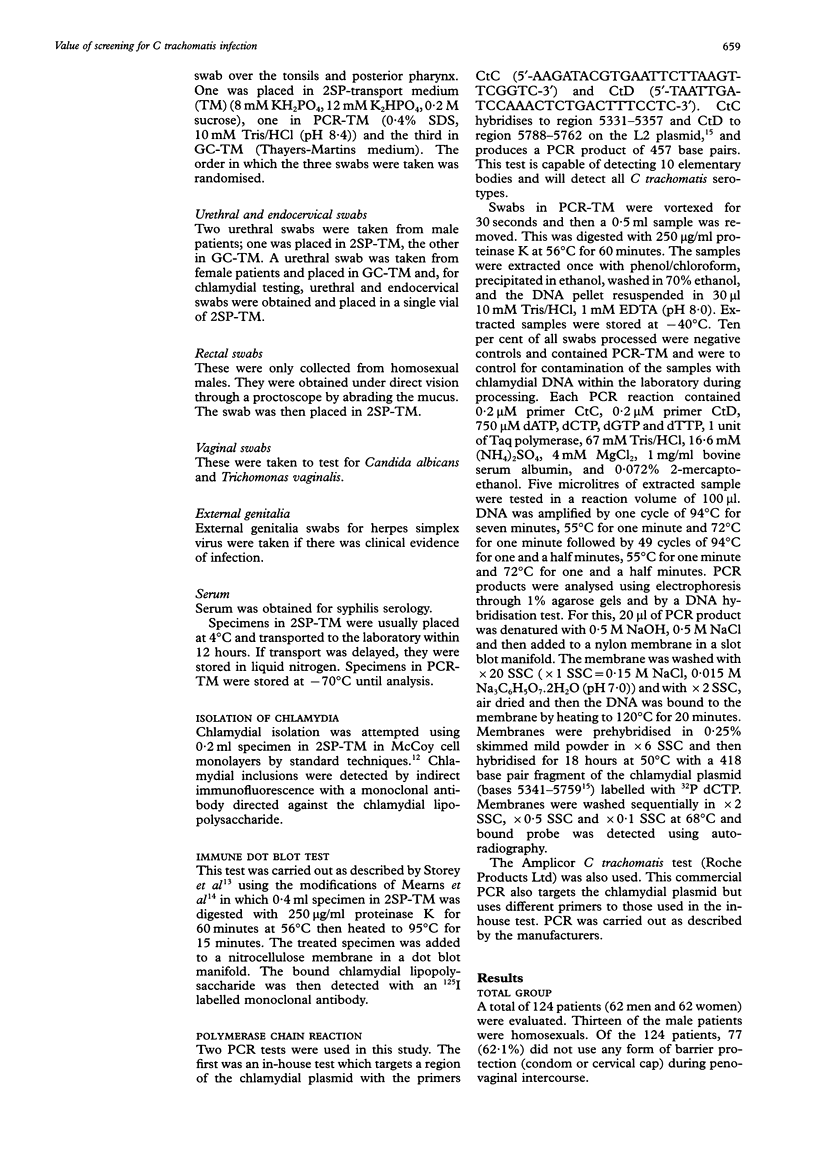

AIMS--To determine whether oro-pharyngeal colonisation by Chlamydia trachomatis occurs in patients at risk of genital chlamydia infection; to determine whether screening pharyngeal specimens by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) increases detection of C trachomatis compared with isolation and the immune dot blot test; and to correlate the detection of C trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the pharynx with a history of oro-genital contact. METHODS--Thirteen homosexuals and 11 heterosexuals were included in the study. Urogenital and pharyngeal specimens were tested for C trachomatis and N gonorrhoeae using standard clinical diagnostic procedures. Two different PCR methodologies were also used to detect C trachomatis in the pharyngeal specimens. Results were correlated with the mode of sexual practice. RESULTS--Oro-genital sexual contact was practised by 64.9% (72/111) of heterosexuals in addition to penetrative penovaginal intercourse. Additionally, 62.1% (77/124) of all patients did not use any form of barrier protection. Of those who admitted to oro-genital sexual contact, 17.6% of patients with a genital chlamydial infection and 36.4% of those with genital gonorrhoea also had asymptomatic pharyngeal colonisation. C trachomatis was detected in three of 124 (2.4%) pharyngeal specimens by PCR which were reported as negative by chlamydial culture; one was positive by the immune dot blot test. CONCLUSION--The majority of patients practised unprotected oro-genital contact and significant pharyngeal colonisation by C trachomatis and N gonorrhoeae occurred if genital infection was present. Despite the use of PCR in a population at high risk of sexually transmitted disease, the prevalence of chlamydia in the pharynx was very low. This indicates that transmission of C trachomatis to the oro-pharynx does not pose a serious health risk and that screening of patients for oro-pharyngeal C trachomatis is not worthwhile.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Billy J. O., Tanfer K., Grady W. R., Klepinger D. H. The sexual behavior of men in the United States. Fam Plann Perspect. 1993 Mar-Apr;25(2):52–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobo L., Munoz B., Viscidi R., Quinn T., Mkocha H., West S. Diagnosis of Chlamydia trachomatis eye infection in Tanzania by polymerase chain reaction/enzyme immunoassay. Lancet. 1991 Oct 5;338(8771):847–850. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91502-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie W. R., Alexander E. R., Holmes K. K. Chlamydial pharyngitis? Sex Transm Dis. 1977 Oct-Dec;4(4):140–141. doi: 10.1097/00007435-197710000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bro-Jorgensen A., Jensen T. Gonococcal pharyngeal infections. Report of 110 cases. Br J Vener Dis. 1973 Dec;49(6):491–499. doi: 10.1136/sti.49.6.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comanducci M., Ricci S., Ratti G. The structure of a plasmid of Chlamydia trachomatis believed to be required for growth within mammalian cells. Mol Microbiol. 1988 Jul;2(4):531–538. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1988.tb00060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans B. A., Tasker T., MacRae K. D. Risk profiles for genital infection in women. Genitourin Med. 1993 Aug;69(4):257–261. doi: 10.1136/sti.69.4.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber M. A., Ryan R. W., Tilton R. C., Watson J. E. Role of Chlamydia trachomatis in acute pharyngitis in young adults. J Clin Microbiol. 1984 Nov;20(5):993–994. doi: 10.1128/jcm.20.5.993-994.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs N. F., Jr, Arum E. S., Kraus S. J. Experimental infection of the chimpanzee urethra and pharynx with Chlamydia trachomatis. Sex Transm Dis. 1978 Oct-Dec;5(4):132–136. doi: 10.1097/00007435-197810000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaschek G., Gaydos C. A., Welsh L. E., Quinn T. C. Direct detection of Chlamydia trachomatis in urine specimens from symptomatic and asymptomatic men by using a rapid polymerase chain reaction assay. J Clin Microbiol. 1993 May;31(5):1209–1212. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.5.1209-1212.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R. B., Rabinovitch R. A., Katz B. P., Batteiger B. E., Quinn T. S., Terho P., Lapworth M. A. Chlamydia trachomatis in the pharynx and rectum of heterosexual patients at risk for genital infection. Ann Intern Med. 1985 Jun;102(6):757–762. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-102-6-757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan A., Sommerville R. G., McKie P. M. Chlamydial infection in homosexual men. Frequency of isolation of Chlamydia trachomatis from the urethra, ano-rectum, and pharynx. Br J Vener Dis. 1981 Feb;57(1):47–49. doi: 10.1136/sti.57.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mearns G., Richmond S. J., Storey C. C. Sensitive immune dot blot test for diagnosis of Chlamydia trachomatis infection. J Clin Microbiol. 1988 Sep;26(9):1810–1813. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.9.1810-1813.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscicki A. B., Millstein S. G., Broering J., Irwin C. E., Jr Risks of human immunodeficiency virus infection among adolescents attending three diverse clinics. J Pediatr. 1993 May;122(5 Pt 1):813–820. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(06)80035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble R. C., Cooper R. M., Miller B. R. Pharyngeal colonisation by Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Neisseria meningitidis in black and white patients attending a venereal disease clinic. Br J Vener Dis. 1979 Feb;55(1):14–19. doi: 10.1136/sti.55.1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Näher H., Drzonek H., Wolf J., von Knebel Doeberitz M., Petzoldt D. Detection of C trachomatis in urogenital specimens by polymerase chain reaction. Genitourin Med. 1991 Jun;67(3):211–214. doi: 10.1136/sti.67.3.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackel S. G., Alpert S., Fiumara N. J., Donner A., Laughlin C. A., McCormack W. M. Orogenital contact and the isolation of Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Mycoplasma hominis, and Ureaplasma urealyticum from the pharynx. Sex Transm Dis. 1979 Apr-Jun;6(2):64–68. doi: 10.1097/00007435-197904000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey C. C., Mearns G., Richmond S. J. Immune dot blot technique for diagnosing infection with Chlamydia trachomatis. Genitourin Med. 1987 Dec;63(6):375–379. doi: 10.1136/sti.63.6.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulaiman M. Z., Foster J., Pugh S. F. Prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis infection in homosexual men. Genitourin Med. 1987 Jun;63(3):179–181. doi: 10.1136/sti.63.3.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willmott F. E. Transfer of gonococcal pharyngitis by kissing? Br J Vener Dis. 1974 Aug;50(4):317–318. doi: 10.1136/sti.50.4.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkin S. S., Jeremias J., Toth M., Ledger W. J. Detection of Chlamydia trachomatis by the polymerase chain reaction in the cervices of women with acute salpingitis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993 May;168(5):1438–1442. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(11)90778-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]