Abstract

INTRODUCTION

While corticosteroids are an effective choice of treatment for severe vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC), their long-term use is restricted due to side effects. This study was conducted to evaluate the efficacy and safety of topical cyclosporine A (CsA) 0.05% in the treatment of VKC.

METHODS

A total of 30 patients with VKC that was resistant to topical corticosteroids, antihistamines and mast cell stabilisers were treated with topical CsA 0.05%. Patients were evaluated at Weeks 4, 8 and 12 after the initiation of therapy. Symptoms and signs observed before and after treatment were recorded and scores were assigned. Scores for symptoms and signs, the need for topical corticosteroids and ocular side effects were evaluated.

RESULTS

At baseline, the median values of the symptom and sign scores were 10.0 (range 5.0–18.0) and 6.0 (range 2.0–13.0), respectively. At Week 4 of treatment with topical CsA 0.05%, the median values of the symptom and sign scores were 3.0 (range 0–14.0) and 3.0 (range 0–8.0), respectively. The reductions in the symptom and sign scores were statistically significant. The reduction in the need for corticosteroid was statistically significant by Week 12 of therapy. No significant side effects were reported.

CONCLUSION

Topical CsA 0.05%, which can help to reduce corticosteroid usage, is an effective and safe alternative for the treatment of resistant VKC. Further studies are needed to determine the optimal duration of therapy and possibility of recurrence.

Keywords: allergic conjunctivitis, cyclosporine A, restasis, vernal keratoconjunctivitis

INTRODUCTION

Vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC) is a seasonal, chronic allergic disease involving the bulbar and tarsal conjunctiva. VKC is more common in men, children and young adults, especially those living in dry and temperate areas;(1-3) a genetic predisposition has not been detected.(1) Itching, burning, foreign body sensation, photophobia, lacrimation, hyperaemia and mucoid discharge may occur in VKC.(1-3) Giant papillae (≥ 1 mm) are typically found on the superior tarsal and bulbar conjunctiva (i.e. tarsal and bulbar forms, respectively). Horner-Trantas nodules composed of degenerated eosinophils and epithelial cell debris are commonly found in the limbal region, while corneal involvement may be seen as punctate epithelial keratitis, epithelial macroerosions, shield ulcers, plaque formation, corneal neovascularisation and pseudogerontoxon.(1) Although the immunopathogenic mechanisms of VKC are complicated, immunoglobulin E-mediated hypersensitivity response, and mast cell, eosinophil and lymphocyte activation by type 2 T-helper cell (Th2) stimulation are thought to be responsible.(1,3,4) In one study that reviewed 195 patients with VKC, a family history of allergic disorders was reported in 49% of the patients with VKC.(5)

Topical and systemic antihistamines, topical inhibitors of mast cell degranulation, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and corticosteroids are widely used in the treatment of VKC. Although corticosteroids are the most effective treatment option in moderate and severe VKC, their long-term use is restricted because of side effects that include glaucoma, cataract and corneal complications.(1) Topical cyclosporine A (CsA), which has immunomodulatory effects, has recently received attention for its ability to reduce corticosteroid usage and its potential as an alternative treatment for corticosteroid-resistant cases.(6-10) CsA is a fungal metabolite that reduces ocular inflammation by inhibiting Th2 lymphocyte proliferation, interleukin-2 production, and histamine release from mast cells and basophils.(1,3,11,12) In the present study, we aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of topical CsA 0.05% in the treatment of severe VKC that is resistant to classical antiallergic therapy.

METHODS

A total of 30 patients with severe VKC who were treated at the Ophthalmology Clinics of the Erzurum Regional Training and Research Hospital, Turkey, were included in the present study. Enrolled patients (a) were diagnosed with VKC; (b) had attended follow-up sessions for at least a year; and (c) were unresponsive to treatment with topical corticosteroids, antihistamines and mast cell stabilisers. All patients had active disease during enrolment. Patients who did not meet the criteria or were aged < 5 years were excluded. The study was performed according to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and informed consent was obtained from patients or the parents of patients younger than 18 years of age.

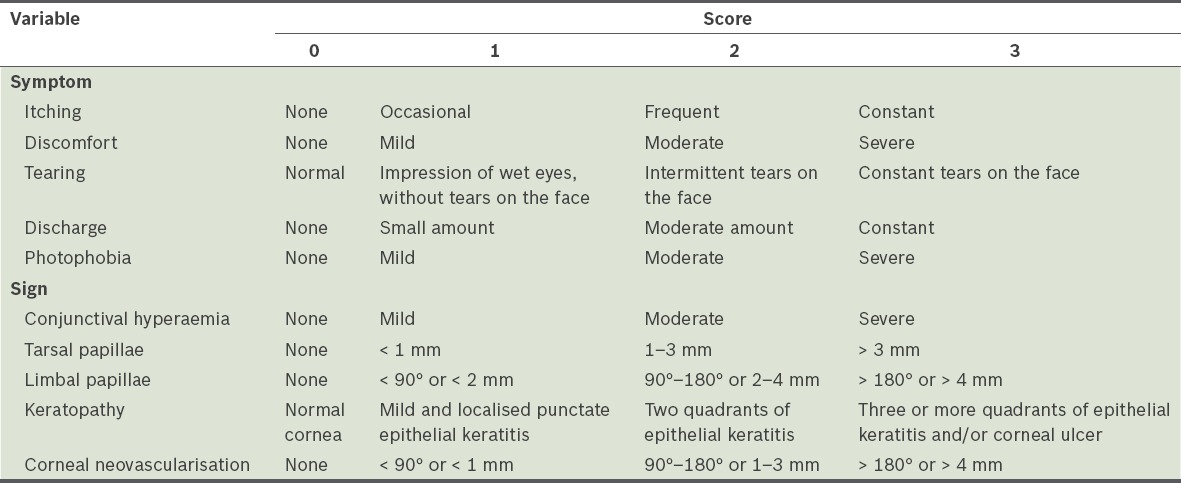

A detailed medical history was obtained and complete ophthalmological examinations were performed. In patients without photophobia and blepharospasm, visual acuity was evaluated using Snellen charts. Intraocular pressures were measured with non-contact tonometers. Anterior segment biomicroscopy and indirect ophthalmoscopy were conducted, and anterior segment photographs were taken. The patients were evaluated at Weeks 4, 8 and 12 after the initiation of therapy. Symptoms and signs before and after treatment, during the four-week intervals, were recorded and scores between 0 and 3 were assigned. Symptom scores were calculated by grading itching, discomfort (i.e. foreign body sensation, stinging and burning), tearing, discharge and photophobia. Sign scores were calculated by grading conjunctival hyperaemia, tarsal papillae, limbal papillae, keratopathy and corneal neovascularisation. Extensiveness and size were considered when grading the tarsal conjunctival and limbal papillae. Corneal signs were scored according to the extensiveness of punctate epithelial keratitis and/or presence of ulceration. Corneal neovascularisation was graded according to corneal quadrants and by measuring the dimension from the limbus to the central cornea (Table I).

Table I.

Scoring method for the signs and symptoms of severe vernal keratoconjunctivitis.

Topical CsA 0.05% (Restasis®; Allergan Inc, Irvine, CA, USA) four times a day was added to each patient’s treatment regimen. Although topical drugs that the patients were taking were not ceased, topical corticosteroid doses were reduced or stopped when possible (i.e. if clinical recovery was observed) during clinic visits.

Scores for symptoms and signs, the need for topical corticosteroids and ocular side effects were evaluated. All data was analysed using SPSS version 15.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Data on symptom and sign scores that did not have a normal distribution was compared using Friedman test and a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. For dual comparison of scores collected at different times, Wilcoxon test with Bonferroni correction was applied and a p-value < 0.008 was considered statistically significant. Wilcoxon test was used for comparing steroid doses and a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Among the 30 patients with severe VKC who were recruited for the study, 19 were male and 11 were female. The mean age of the patients was 12.9 ± 3.9 (range 6–25) years. The severe VKC was of the bulbar, tarsal and mixed type in 9 (30.0%), 2 (6.7%) and 19 (63.3%) patients, respectively. The mean disease duration before treatment was 3.8 ± 2.1 (range 1–9) years.

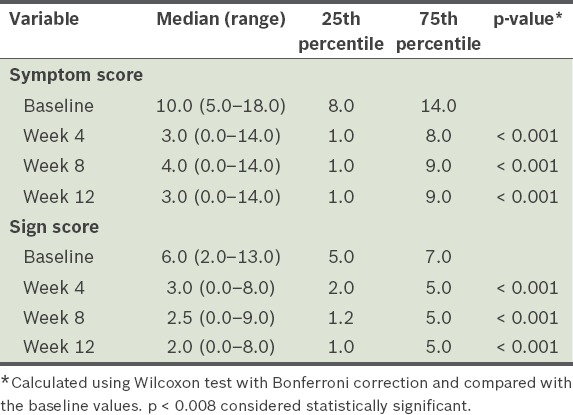

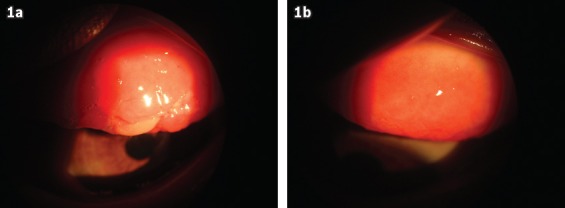

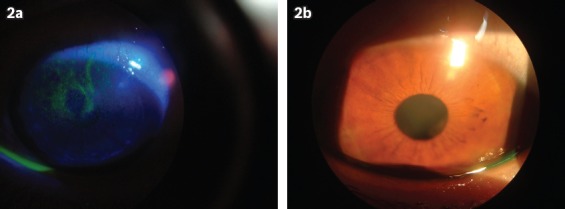

Before treatment with topical CsA 0.05%, the median values of the symptom and sign scores were 10.0 (range 5.0–18.0) and 6.0 (range 2.0–13.0), respectively. These scores were reduced at Week 4 of therapy (symptom score: 3.0 [range 0.0–14.0]; sign score: 3.0 [range 0.0–8.0]). When compared with the baseline scores, the reductions in the symptom and sign scores at Weeks 4, 8 and 12 of treatment were statistically significant (p < 0.05). There was no significant improvement in symptom scores between Weeks 4 and 12, while the sign scores continued to improve (p < 0.008) (Table II; Figs. 1 & 2).

Table II.

Symptom and sign scores of the study cohort (n = 30).

Fig. 1.

Photographs of the tarsal conjunctiva of a patient with severe vernal keratoconjunctivitis (a) before and (b) after eight weeks of treatment with topical cyclosporine A 0.05%. The pre-treatment image shows giant papillae and mucoid discharge, while the post-treatment image shows improvement in the upper tarsal conjunctiva.

Fig. 2.

Photographs of the cornea of a patient with severe vernal keratoconjunctivitis (a) before and (b) after eight weeks of treatment with topical cyclosporine A 0.05%. The pre-treatment image shows punctate epithelial keratitis.

The median topical corticosteroid dosage was 3 (range 2–4) times a day at baseline and 2 (range 0–3) times a day at Week 12 of CsA 0.05% therapy. In 13.3% of the patients, corticosteroid therapy could be completely ceased within 12 weeks. By Week 12 of therapy, the reduction in the need for corticosteroids was statistically significant (p < 0.05). Patients were followed up for three months; during this period, 1 (3.3%) patient complained of foreign body sensation after the instillation of topical CsA 0.05%, but the side effect was temporary. No other side effects were reported.

DISCUSSION

VKC is a chronic allergic disease that has complicated immunopathogenic mechanisms.(1,5) Although topical corticosteroids are effective for treating VKC, their long-term use is restricted due to side effects.(2) For this reason, low-dose topical CsA has emerged as an alternative therapy for VKC to reduce corticosteroid usage or for corticosteroid-resistant cases.(6-10) In the present study, outcomes of the use of topical CsA 0.05% in the treatment of severe VKC that is resistant to classical antiallergic therapy were evaluated. Significant reductions in the symptom and sign scores were detected at Week 4 of initiation of topical CsA 0.05% therapy. When compared with the baseline scores, the reductions in the symptom and sign scores at Weeks 4, 8 and 12 of treatment were statistically significant. After Week 4, further reductions in symptom scores were observed at follow-up, while reductions in sign scores were present but not statistically significant at all visits.

Studies on the use of topical CsA 1%–2% in atopic keratoconjunctivitis (AKC) and VKC have been published in the last 20 years.(6-8,13-17) Secchi et al reported cases of significant recoveries in clinical scores after the use of topical CsA 2% for two weeks.(6) 73% (n = 8) of patients in that study reported a transient burning sensation upon administration of topical CsA 2% and recurrences were reported 2–4 months after the cessation of therapy.(6) In a double-masked clinical trial conducted by Bleik and Tabbara, which included 20 patients with VKC, the authors detected significant reductions in conjunctival hyperaemia, papillary hypertrophy, punctate epithelial keratitis and Horner-Trantas nodules with the use of topical CsA 2% when compared to a placebo; other than that, no side effects were observed and CsA was not detected in the serum of the patients.(7)

In a study conducted by Pucci et al, 24 patients with VKC were treated with topical CsA 2% in one eye and a placebo in the other eye during the first two weeks of treatment.(8) Significant reductions in the clinical scores of the eye treated with CsA 2% were detected after the first two weeks. In the second phase of the study, both the patients’ eyes were treated with CsA 2% for two weeks. Clinical scores were reduced in the eyes that were treated with the placebo, but there was no further improvement in the eyes that were previously treated with CsA 2%. This effect persisted during follow-up, which lasted for four months. Among the 24 patients in the study, 4 (16.7%) needed topical corticosteroids, and most patients reported a burning sensation and lacrimation after drug administration.(8)

Spadavecchia et al reported significant reductions in the clinical scores of their patients with severe VKC at Week 2 and Month 4 of therapy, when either topical CsA 1.25% or topical CsA 1% was used.(13) CsA serum levels and corneal endothelial damage were not detected at the end of therapy and no side effects were reported other than a burning sensation during administration.(13) Tesse et al reported similar results in their study, which involved the use of topical CsA 1% in 197 patients with severe VKC.(14) In a study conducted by Kiliç and Gürler, treatment with CsA 2% was found to result in a significant reduction in clinical scores after two weeks as compared to ‘treatment’ using a placebo and no side effects were reported from the use of CsA 2%.(15) In another study, Pucci et al followed up on 156 patients with VKC who received topical CsA 1% and 2% for 2–7 years and reported significant reductions in these patients’ clinical scores when compared with their scores before treatment; some of the patients complained that they experienced a burning sensation, but their liver and renal functions were not affected, and CsA was not detected in serum.(16) In a double-blinded study, De Smedt et al compared the efficacy of topical CsA 2% and dexamethasone 0.1%.(17) After four weeks of therapy, the authors found that the reductions in the clinical scores and the improvements in visual acuity were similar in both treatments; however, foreign body sensation was more prominent with CsA therapy.(17)

Similar to the present study, all the aforementioned studies found that the use of topical CsA 1%–2% was able to reduce the symptoms and signs of patients with VKC after two weeks of therapy.(6-8,13-17) We noted that a burning sensation and foreign body sensation were more prominent in studies that used CsA in oil as compared to those that used an aqueous solution. Thus, such transient side effects might be due to the formulation and not the cyclosporine itself. A recent meta-analysis reported that the stinging or burning sensation is common in both patients who received CsA and those who received placebos.(18)

There are several studies about low-dose topical CsA therapy for AKC and VKC.(9,19-21) A study by Ozcan et al, which examined the use of topical CsA 0.05% in seven cases of severe allergic conjunctivitis, found significant reductions in the symptom and sign scores, and a reduction in the demand for corticosteroids, with no side effects observed.(19) In a placebo-controlled, double-masked study, no significant difference was detected in the symptom, sign and drug scores of the 40 patients with either AKC or VKC after three months of treatment with topical CsA 0.05%; no side effects were reported.(9) The authors explained that their findings may be due to the fact that although CsA is specifically more effective on type 1 T-helper cells, VKC is a Th2 cell-mediated chronic inflammation with an increase in CD4+ cells.(9) Keklikci et al reported reductions in the clinical scores and inflammatory cell counts (using conjunctival impression cytology) of 54 patients after three months of topical CsA 0.05% therapy, with no side effects.(20) A study conducted by Takamura et al, involving 2,597 patients with VKC who were treated with CsA 0.1% for six months, reported decreased clinical scores and the disappearance of steroid demand in one-third of the patients; additionally, 7.4% of them experienced ocular irritation and 1.4% had ocular infections.(21) In the present study, the use of CsA 0.05% resulted in reduced steroid demand, with no serious side effects detected. Only one patient experienced a transient burning sensation upon administration of the drug.

According to the results of the present study, the use of topical CsA 0.05% four times a day is an effective and safe alternative therapy for VKC that is resistant to classical antiallergic therapy. Further studies are needed to determine the optimal duration of therapy and examine the likelihood of recurrence after the cessation of CsA.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to thank Dr Ozlem Terzi, Public Health Deputy Director, Public Health Directorate, Corum, Turkey, for the assistance given in the clinical information analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kumar S. Vernal keratoconjunctivitis:a major review. Acta Ophthalmol. 2009;87:133–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2008.01347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vichyanond P, Pacharn P, Pleyer U, Leonardi A. Vernal keratoconjunctivitis:a severe allergic eye disease with remodeling changes. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2014;25:314–22. doi: 10.1111/pai.12197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kari O, Saari KM. Updates in the treatment of ocular allergies. J Asthma Allergy. 2010;3:149–58. doi: 10.2147/JAA.S13705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.el-Asrar AM, Tabbara KF, Geboes K, Missotten L, Desmet V. An immunohistochemical study of topical cyclosporine in vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;121:156–161. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70579-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonini S, Bonini S, Lambiase A, et al. Vernal keratoconjunctivitis revisited:a case series of 195 patients with long-term followup. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:1157–63. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00092-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Secchi AG, Tognon MS, Leonardi A. Topical use of cyclosporine in the treatment of vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1990;110:641–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)77061-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bleik JH, Tabbara KF. Topical cyclosporine in vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:1679–84. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pucci N, Novembre E, Cianferoni A, et al. Efficacy and safety of cyclosporine eyedrops in vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002;89:298–303. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61958-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daniell M, Constantinou M, Vu HT, Taylor HR. Randomised controlled trial of topical ciclosporin A in steroid dependent allergic conjunctivitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:461–4. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.082461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tatlipinar S, Akpek EK. Topical ciclosporin in the treatment of ocular surface disorders. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89:1363–7. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.070888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nussenblatt RB, Palestine AG. Cyclosporine:immonology, pharmacology and therapeutic uses. Surv Ophthalmol. 1986;31:159–69. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(86)90035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukushima A, Yamaguchi T, Ishida W, et al. Cyclosporin A inhibits eosinophilic infiltration into the conjunctiva mediated by type IV allergic reactions. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2006;34:347–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2006.01221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spadavecchia L, Fanelli P, Tesse R, et al. Efficacy of 1.25% and 1% topical cyclosporine in the treatment of severe vernal keratoconjunctivitis in childhood. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2006;17:527–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2006.00427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tesse R, Spadavecchia L, Fanelli P, et al. Treatment of severe vernal keratoconjunctivitis with 1% topical cyclosporine in an Italian cohort of 197 children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2010;21(2 Pt 1):330–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2009.00948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kiliç A, Gürler B. Topical 2% cyclosporine A in preservative-free artificial tears for the treatment of vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Can J Opthalmol. 2006;41:693–8. doi: 10.3129/i06-061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pucci N, Caputo R, Mori F, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of topical cyclosporine in 156 children with vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2010;23:865–71. doi: 10.1177/039463201002300322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Smedt S, Nkurikiye J, Fonteyne Y, et al. Topical ciclosporin in the treatment of vernal keratoconjunctivitis in Rwanda, Central Africa:a prospective, randomised, double-masked, controlled clinical trial. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96:323–8. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wan KH, Chen LJ, Rong SS, Pang CP, Young AL. Topical cyclosporine in the treatment of allergic conjunctivitis:a meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:2197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ozcan AA, Ersoz TR, Dulger E. Management of severe allergic conjunctivitis with topical cyclosporin a 0.05% eyedrops. Cornea. 2007;26:1035–8. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31812dfab3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keklikci U, Soker SI, Sakalar YB, et al. Efficacy of topical cyclosporin A 0.05% in conjunctival impression cytology specimens and clinical findings of severe vernal keratoconjunctivitis in children. Jpn J Opthalmol. 2008;52:357–62. doi: 10.1007/s10384-008-0577-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takamura E, Uchio E, Ebihara N, et al. [A prospective, observational, all-prescribed-patients study of cyclosporine 0.1% ophthalmic solution in the treatment of vernal keratoconjunctivitis] Nihon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 2011;115:508–15. Japanese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]