Significance

Polyketides are a chemically diverse class of natural products with broad pharmaceutical applications. β-Branching in modular polyketide synthase pathways contributes to this diversity by introducing alkyl branches into polyketide intermediates, ranging from simple methyl groups to more unusual structures, including the curacin A cyclopropane ring. Branching replaces the β-carbonyl of a polyketide intermediate, which is more commonly reduced and/or methylated. Furthermore, β-branching is catalyzed by cassettes of standalone enzymes and is targeted to a specific point in a polyketide synthase PKS pathway by specialized acyl carrier proteins (ACPs). In these structural studies, we have begun to elucidate the mechanisms of ACP selectivity by the initiating enzyme of β-branching. This work may be essential for rational efforts to diversify polyketides using unnatural β-branching schemes.

Keywords: natural products, polyketide synthase, curacin, HMG synthase, acyl carrier protein

Abstract

Alkyl branching at the β position of a polyketide intermediate is an important variation on canonical polyketide natural product biosynthesis. The branching enzyme, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl synthase (HMGS), catalyzes the aldol addition of an acyl donor to a β-keto-polyketide intermediate acceptor. HMGS is highly selective for two specialized acyl carrier proteins (ACPs) that deliver the donor and acceptor substrates. The HMGS from the curacin A biosynthetic pathway (CurD) was examined to establish the basis for ACP selectivity. The donor ACP (CurB) had high affinity for the enzyme (Kd = 0.5 μM) and could not be substituted by the acceptor ACP. High-resolution crystal structures of HMGS alone and in complex with its donor ACP reveal a tight interaction that depends on exquisite surface shape and charge complementarity between the proteins. Selectivity is explained by HMGS binding to an unusual surface cleft on the donor ACP, in a manner that would exclude the acceptor ACP. Within the active site, HMGS discriminates between pre- and postreaction states of the donor ACP. The free phosphopantetheine (Ppant) cofactor of ACP occupies a conserved pocket that excludes the acetyl-Ppant substrate. In comparison with HMG-CoA (CoA) synthase, the homologous enzyme from primary metabolism, HMGS has several differences at the active site entrance, including a flexible-loop insertion, which may account for the specificity of one enzyme for substrates delivered by ACP and the other by CoA.

Polyketides are a large and chemically diverse group of natural products that includes many pharmaceuticals with a broad range of biological activities and applications as antibiotics, antifungals, antiinflammatory drugs, and cancer chemotherapeutic agents (1). Polyketide synthase (PKS) biosynthetic pathways are subjects of efforts to engineer diversification of natural products in pursuit of pharmaceutical leads and compounds of industrial importance (2). They are rich sources for development of chemo-enzymatic catalysts based on PKS enzymes with unusual catalytic activities.

Modular type I PKS pathways, among the most versatile of nature’s systems, are biosynthetic assembly lines composed of modules that act in a defined sequence to produce complex products with a variety of functional groups and chiral centers. Each module is a set of fused catalytic domains that extend and modify a polyketide intermediate. Biosynthesis proceeds from intermediates tethered to acyl carrier protein (ACP) domains via a thioester link to a phosphopantetheine (Ppant) cofactor. A ketosynthase (KS) domain catalyzes extension of the intermediate, and subsequent modification domains typically catalyze reduction and/or methylation of the β-keto (3-keto) extension product. Beyond the enzymes for these core reactions, many PKS pathways also include other catalytic functionality. Among the most interesting of these noncanonical capabilities is alkylation at the β position by a set of β-branching enzymes (3). A 3-hydroxymethylglutaryl (HMG) synthase enzyme (HMGS) catalyzes the key branch-incorporation step, generating a β-hydroxy, β-carboxyalkyl acyl-ACP (Fig. 1A). The final structure of a β-branch depends on the carboxyalkyl group and the series of enzymatic steps that tailor the initial branch generated by HMGS (3).

Fig. 1.

HMGS reaction. (A) Reaction steps. (1) ACPD transfers an acetyl group to HMGS Cys114 and Glu82 deprotonates the acetyl group; (2) the resulting enolate nucleophile attacks acetoacetyl-ACPA; (3) the HMG-ACPA product is hydrolyzed from Cys114. R indicates the polyketide intermediate (methyl in curacin A biosynthesis). (B) Structure of the Ppant cofactor (represented as a squiggle symbol in A).

The natural product curacin A, produced by the marine cyanobacterium Moorea producens (4), has cytotoxic activity and has been explored as an anticancer agent (5). The hybrid PKS/NRPS (nonribosomal peptide synthetase) pathway for curacin A contains an abundance of unique enzymes that install distinctive functional groups (6), including a cyclopropane ring formed by a surprising variation of the β-branching process (7). In curacin A β-branching, the initial HMG-ACP intermediate undergoes chlorination, dehydration, and decarboxylation before a reductive ring-closing reaction generates the final cyclopropane group (7) (Fig. S1).

Fig. S1.

Curacin β-branching. (A) CurC KSDC is proposed to decarboxylate malonyl-CurB, generating acetyl-CurB (ACPD), (1) CurD HMGS catalyzes formation of HMG-CurA ACP3 (ACPA), (2) CurA Hal chlorinates the γ-carbon of HMG-ACPA, which is subsequently dehydrated to 3 and decarboxylated to 4 by CurE ECH1 and CurF ECH2, respectively. CurF ER catalyzes cyclopropanation to 6 by NADPH-dependent addition of hydride and elimination of chloride. (B) Reaction catalyzed by HMGCS, the HMGS homolog from primary metabolism.

HMGS is a homolog of the KS extension enzyme in PKS pathways, but it is more closely related to HMG-CoA (CoA) synthase (HMGCS), an enzyme of primary metabolism in the mevalonate-dependent isoprenoid pathway, where it acts directly before HMG-CoA reductase (8). HMGCS generates HMG-CoA from acetyl-CoA and acetoacetyl-CoA by an aldol addition (Fig. S1B). The acetyl group is transferred to a catalytic cysteine, then deprotonated by a conserved glutamate. The resulting enolate nucleophile attacks the β-carbonyl of the second substrate, acetoacetyl-CoA. The covalent enzyme-product complex is hydrolyzed to release HMG-CoA. HMGCS is well characterized, including crystal structures of complexes between the enzyme and its product, substrates, and inhibitors (9–14).

The HMGS and HMGCS reactions (Fig. 1) are analogous and, in the case of the curacin A HMGS (CurD), have identical acyl substrates that are tethered to distinct ACPs and not to CoA. Whereas HMGCS distinguishes acetyl-CoA and acetoacetyl-CoA based on the acyl group and the acetylation status of the catalytic cysteine, HMGS also displays ACP selectivity: a standalone acetyl “donor” ACP (ACPD), and an acetoacetyl-like “acceptor” ACP (ACPA) bearing the polyketide intermediate within a specific module of the PKS pathway (15, 16). HMGS enzymes are highly selective for acetoacetyl-ACPA and acetyl-ACPD, and do not react with CoA substrates (15–17). At the sequence level, the donor and acceptor ACPs clade separately from each other and from nonbranch ACPs from the same pathways (15, 18). Thus, by selecting for the correct acyl-ACPs, HMGS prevents the formation of aberrantly branched metabolites.

The basis of ACP selectivity by HMGS is unknown, and detailed views of ACP interactions with PKS enzymes are few. The homologous KS extension enzymes distinguish their cognate donor and acceptor ACPs through two active site entrances (19) in interactions facilitated by fusion or noncovalent interaction of appended docking domains (20, 21), which are absent in HMGS. HMGS selectivity for ACPA and ACPD presumably originates from distinguishing features of each ACP that result in different modes of interaction with HMGS. Here we present the biochemical characterization of the curacin A HMGS (CurD) and the interaction with its cognate ACPD (CurB). Crystal structures of HMGS and of complexes with ACPD reveal a striking shape complementarity between the proteins and specific charge interactions that orient the Ppant cofactor in the HMGS active site. Pre- and postacetyl transfer states of Ppant capture sequential views of the catalytic cycle. The results are a detailed benchmark of high-affinity enzyme-ACP interactions that advance our understanding of enzyme selectivity for carrier proteins.

Results

CurD HMGS Activity.

Purified, recombinant ACPD (CurB) and the second cognate ACPA from the CurA tandem ACPA tridomain (Fig. S1) were acylated in vitro. Recombinant CurD HMGS converted 83% of equimolar acetyl-ACPD and acetoacetyl-ACPA to HMG-ACPA in a 10-min reaction at 25 °C (Table 1). Reaction progress was monitored by LC-MS using the acyl-Ppant ejection assay (22) (Fig. S2 and Table S1). We detected no conversion of acetoacetyl-ACPA to HMG-ACPA when the catalytic Cys114 was substituted with serine (Table 1). The C114S substitution also prevented acetyl transfer from acetyl-ACPD (Table S2).

Table 1.

HMGS activity and ACPD affinity

| Sample | HMGS activity (%)* | Kd (apo-ACPD) (μM)† | Kd (holo-ACPD) (μM) |

| HMGS and crystallization variant‡ | |||

| WT | 82.8 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.2 |

| AAA‡ | 87 ± 1 | — | — |

| Mismatched acyl-ACP substrates§ | |||

| ACPD as donor and acceptor | 29 ± 2 | — | — |

| ACPA as donor and acceptor | ND | — | — |

| HMGS active site substitutions | |||

| C114S | ND | — | — |

| P166A | 88.1 ± 0.3 | — | — |

| S167A | 95.5 ± 0.3 | — | — |

| ACPD/HMGS interface substitutions | |||

| ACPD | |||

| R42A | 95.7 ± 0.2 | — | — |

| HMGS | |||

| R33A | ND | 6.9 ± 0.7 | 8 ± 2 |

| R33D | 2 ± 3 | 29 ± 3 | 25 ± 3 |

| D214A | 86 ± 8 | 10.9 ± 0.9 | 9 ± 2 |

| D214R | 45 ± 4 | 17 ± 5 | 11 ± 3 |

| D222A | 27 ± 1 | 28 ± 2 | 1.5 ± 0.6 |

| D222R | 17 ± 1 | 34 ± 2 | 5 ± 1 |

| E225A | 55 ± 3 | 90 ± 4 | — |

| E225R | 8 ± 1 | 68 ± 5 | 12 ± 1 |

| R266A | 56 ± 1 | 110 ± 10 | 17 ± 2 |

| R266E | 26 ± 1 | 180 ± 10 | 17 ± 5 |

ND, no product detected; —, indicated where the experiment was not performed for the indicated sample.

Conversion of equimolar acetyl-ACPD and acetoacetyl-ACPA to HMG-ACPA in a 10-min reaction at 25 °C. Each value corresponds to the average of three measurements.

Affinities were measured by fluorescence polarization using labeled ACPD. Each value corresponds to the average of three measurements.

All crystal structures were of the HMGSAAA variant (K343A/Q344A/Q346A). Cys114 is the catalytic nucleophile.

In each reaction, either ACPD or ACPA was loaded with both acyl substrates, and equimolar quantities of acetyl-ACP and acetoacetyl-ACP were used.

Fig. S2.

Sample HMGS activity data. Ppant ejection mass spectra of the ACPA elution of an HMGS reaction mix. Ion counts were recorded for the acetoacetyl (calculated m/z = 345.15) and HMG (calculated m/z = 405.17) peaks. See Table S3 for total ion counts for each species.

Table S1.

Conversion of Acetoacetyl-ACPA to HMG-ACPA Evaluated by Ppant Ejection

Table S2.

HMGS-dependent deacetylation of acetyl-ACPD

| Sample | % Acetyl-ACP |

| Acetyl-ACPD (no incubation) | 87 |

| Acetyl-ACPD (18-h incubation, no enzyme) | 88 ± 4 |

| Acetyl-ACPD (18-h incubation with HMGSWT) | 13 ± 10 |

| Acetyl-ACPD (18-h incubation with HMGSC114S) | 86 ± 0.3 |

Acetyl-ACPD was evaluated by MS Ppant ejection. Values given are the percent of total ion counts for ejected acetyl-Ppant among all ejected Ppant species. Incubations were at 20 °C in a buffer of 1× MMT (Qiagen), pH 6.5, and 20 mM (NH4)2SO4. HMGS was present at a 1:10 ratio to ACPD. Under the conditions of the experiment, WT HMGS removed the acetyl group from ACPD, but the catalytic variant HMGS C114S did not. Each incubation measurement was made in duplicate on independently prepared samples.

HMGS Structure.

A triple alanine HMGS variant (K344A/Q345A/Q347A, HMGSAAA) was used for all crystal structures and had catalytic activity indistinguishable from the WT (Table 1). The 2.1-Å crystal structure in space group P3121 (Table S3) was solved by molecular replacement. HMGS is dimeric in solution and in the crystal structure, where the asymmetric unit consists of one subunit (Fig. 2). The catalytic amino acids Glu82, Cys114, and His250 (Figs. S3A and S4A) are identically positioned in HMGS and HMGCS, and the overall folds are similar (RMSD of 2.03 Å for 368 Cα atoms). Striking differences occur at the active site entrance and the dimer interface. A disordered loop (HMGS residues 149–163) near the active site encompases a conserved insertion in HMGS (residues 155–164) relative to HMGCS (Fig. S3A). An adjacent loop at the subunit interface (residues 203–210) has a different conformation than the analogous loop in HMGCS. The HMGS 203–210 loop forms hydrophobic contacts with the partner subunit that involve several residues conserved among HMGS but not HMGCS.

Table S3.

Crystallographic data collection and refinement statistics

| Parameter | HMGS | HMGS/ apo-ACPD | HMGS/ holo-ACPD | HMGSC114S/ ac-ACPD | HMGSWT/ Ac-ACPD | HMGSC114S/ Holo-ACPD | HMGSC114S/ Ac-ACPD | HMGSC114S |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.033 | 1.033 | 1.033 | 1.033 | 1.033 | 1.033 | 1.771 | 1.771 |

| Space group | P3121 | P3121 | P3121 | P3121 | P3121 | P3121 | P3121 | P3121 |

| a,b (Å) | 101.16 | 101.31 | 101.12 | 100.89 | 100.85 | 101.94 | 100.79 | 101.20 |

| c (Å) | 106.23 | 104.59 | 104.6 | 104.46 | 104.27 | 104.56 | 104.32 | 105.92 |

| Data range (Å) | 45.67–2.10 (2.16–2.10) | 45.59–2.05 (2.11–2.05) | 45.54–1.60 (1.63–1.60) | 45.43–1.90 (1.94–1.90) | 45.39–2.10 (2.16–2.10) | 45.82–1.89 (1.93–1.89) | 45.38–2.38 (2.47–2.38) | 45.66–2.38 (2.47–2.38) |

| Unique reflections | 37,159 (3,003) | 39,403 (3,028) | 81,779 (4,012) | 48,869 (3,115) | 36,067 (2,867) | 50,923 (3,099) | 24,958 (2,520) | 25,488 (2,526) |

| Completeness (%) | 100 (100) | 100 (99.9) | 100 (100) | 100.0 (100.0) | 99.8 (98.2) | 99.7 (94.9) | 99.6 (96.7) | 99.4 (95.0) |

| Multiplicity | 19.5 (20.0) | 19.5 (16.4) | 19.8 (20.3) | 19.5 (19.5) | 10.4 (6.1) | 9.9 (9.0) | 18.3 (11.2) | 18.3 (11.4) |

| Wilson B-factor | 51.1 | 37.0 | 23.9 | 29.6 | 37.3 | 31.1 | 38.3 | 46.9 |

| Rmerge (%) | 11.2(222.1) | 11.7 (218.1) | 7.1 (257.9) | 11.6 (152.3) | 13.2 (152.4) | 7.4 (194.0) | 8.9 (123.1) | 5.7 (145.6) |

| Average I/σI | 15.5 (1.5) | 19.1 (1.4) | 24.0 (1.4) | 16.9 (2.2) | 14.8 (1.2) | 17.3 (1.2) | 25.9 (1.7) | 35.3 (1.5) |

| CC1/2 | 1.00 (0.62) | 0.99 (0.53) | 1.00 (0.51) | 1.00 (0.73) | 1.00 (0.48) | 1.00 (0.49) | 1.00 (78.4) | 1.00 (0.73) |

| Rwork (%) | 15.6 | 15.5 | 15.1 | 15.8 | ||||

| Rfree (%) | 19.0 | 19.3 | 16.7 | 18.2 | ||||

| Protein atoms | 3,139 | 3,747 | 3,848 | 3,825 | ||||

| Ppant atoms | – | – | 21 | 45 | ||||

| Water/ion atoms | 161 | 219 | 351 | 219 | ||||

| RMSD bond length (Å) | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0.009 | ||||

| RMSD bond angle (°) | 1.362 | 1.476 | 1.53 | 1.352 | ||||

| Average B-factors | ||||||||

| Protein | 58.5 | 44.0(HMGS) | 30.1 (HMGS) | 35.9(HMGS) | ||||

| 76.7(ACP) | 52.6(ACP) | 53.9(ACP) | ||||||

| Ppant | – | – | 43.3 | 37.2 | ||||

| Water | 64.0 | 55.9 | 44.2 | 47.0 | ||||

| Ramachandran | ||||||||

| Favored (%) | 96.8 | 97.3 | 98.0 | 97.1 | ||||

| Generously allowed (%) | 99.7 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.8 | ||||

| Outlier (%) | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

Fig. 2.

CurD HMGS structure. Within the dimer, the right-hand subunit is colored by sequence from the blue N terminus to the red C terminus. Key residues are shown in ball-and-stick on the gray left monomer, including the catalytic Cys114, Glu82, and His250. Phe148 and Ala164 are the boundaries of the 15-residue disordered loop at the active site entrance. The basic side chain of Arg33 interacts with the Ppant phosphate and is conserved in HMGCS sequences. A dotted line denotes the disordered loop region connecting Phe148 to Ala164.

Fig. S3.

Multiple sequence alignments. Alignments were generated using Clustal Omega (54) and analyzed in Jalview (55). (A) Alignment of HMGS and HMGCS sequences. The boxed sequences on top, identified by protein name, are for the β-branching HMGS and the bottom sequences are for the primary metabolism HMGCS, identified by species of origin. Important residues are numbered by the CurD HMGS sequence. Ppant interacting residues are identified in yellow, catalytic residues in blue, thiol pocket residues in green, and ACPD-interacting residues in red. Species of origin and accession codes for HMGS sequences are as follows: CurD from Moorea producens, Q6DNE9; PksG from Bacillus subtilis, P40830; MupH from Pseudomonas fluorescens, Q8RL63; TaC from Myxococcus xanthus, Q1D5E5; TaF from Myxococcus xanthus, Q1D5E8; BryR from Ca. Endobugula sertula, A2CLL9. Accession codes for HMGCS sequences: Enterococcus faecalis, Q9FD71; Staphylococcus aureus, Q9FD87; Brassica juncea, Q9M6U3; Homo sapiens, Q01581. (B) Alignment of ACPD and ACPA sequences. The alignment was generated using Clustal Omega (54) and analyzed in Jalview (55). Boxed sequences are for ACPD and below for ACPA. Important residues are numbered by the CurB ACPD sequence. The positions of hydrophobic side chains that are conserved aliphatics in ACPD and aromatic in ACPA are indicated by arrows below the alignment (Fig. S6). Species of origin and accession codes for HMGS sequences are as follows: CurB and CurA from Moorea producens 3L (F4Y434, F4Y435); MacpC and MmpA3_ACPs from Pseudomonas fluorescens (Q8RL65, Q8RL76); AcpK and PksL from Bacillus subtilis (Q7PC63, Q05470); TaB, TaE, and Ta1 ACPs from Myxococcus xanthus (Q9XB07, Q9XB04, Q9Z5F4), and BryA and BryC from Candidatus Endobugula sertula (A2CLL5, A2CLL2).

Fig. S4.

Electron density for holo-ACPD-HMGS. Key residues (ball-and-stick) were omitted, and models were refined in phenix.refine (56) with simulated annealing from a start temperature of 5,000 °C. SA-omit density is contoured at 3.0σ in green (A–H) and at 1.5σ in pale green (D and F). HMGS residues are in cyan, ACPD in orange, and Ppant in yellow in each panel. (A) Catalytic HMGS residues. (B) Ppant. (C–G) Ionic contacts (Fig. 3C). (H) Nonpolar contacts (Fig 3D). Weaker omit density for Arg33 and Arg266 is shown in D and F.

HMGS-ACPD Complex.

We tested the ACP selectivity of the curacin A HMGS in experiments where acyl groups were mismatched with ACPD or ACPA (Table 1 and Fig. S2). ACPA was not a surrogate acetyl donor, as we detected no conversion of acetyl-ACPA + acetoacetyl-ACPA to HMG-ACPA. In contrast, ACPD was a weak surrogate acceptor with threefold-reduced conversion of acetyl-ACPD + acetoacetyl-ACPD to HMG-ACPD relative to the natural partners. Thus, HMGS had greater selectivity for the donor ACP than for the acceptor. To investigate the structural basis of ACP selectivity, we pursued structures of HMGS complexes with ACPA and ACPD.

The HMGS active site entrance and surrounding surface were unhindered by crystal contacts, and we captured complexes of HMGS with apo-ACPD, holo-ACPD, and acetyl-ACPD by cocrystallization (Fig. 3 and Table S3). The ACPD was well ordered at the HMGS active site entrance, made no lattice contacts, and contacted neither the partner subunit of the HMGS dimer nor its bound ACPD. The holo-ACPD Ppant had clear electron density in the active site (Fig. 4A and Fig. S4B) yet formed only a few interactions, including the phosphate to HMGS Arg33 and ACPD Arg42, which was also salt-bridged to HMGS Asp214 (Fig. 3 B and C). The Ppant-Arg42-Asp214 network is specific to ACPD-HMGS pairs (Fig. S3), but the Arg33-Ppant interaction also occurred in HMGCS-CoA complexes (9, 11). Ppant binding induced ordering of amino acids 159–163 in the HMGS disordered loop, forming a 310 helix with hydrogen bonds of Phe163 and Ser167 to the Ppant (Fig. 3B). The Ppant thiol occupies a relatively hydrophobic “thiol pocket” (conserved amino acids Ser216, Leu217, Tyr220, Pro252, Met256 and Tyr326) and is hydrogen bonded to the Ser216 hydroxy group (Fig. 3B). An extensive network of hydrogen bonds involving Ser216, Tyr220, Tyr326 and conserved Asp200 maintains the structure of the thiol pocket.

Fig. 3.

HMGS interaction with the donor ACP. (A) ACPD (orange)/HMGS (cyan) complex. Ppant (yellow) and catalytic residues shown are in ball-and-stick form. (B) Ppant in the HMGS active site. Dashed yellow lines represent hydrogen bonds and the long separation of Ppant and Cys114 thiol groups. (C) Stereoview of charged contacts in the HMGS-ACPD interface. (D) Stereoview of hydrophobic contacts between ACPD and HMGS. HMGS helices are numbered as in Fig. 2, and ACPD helices are labeled by Roman numerals. Helices in C and D are transparent for clarity.

Fig. 4.

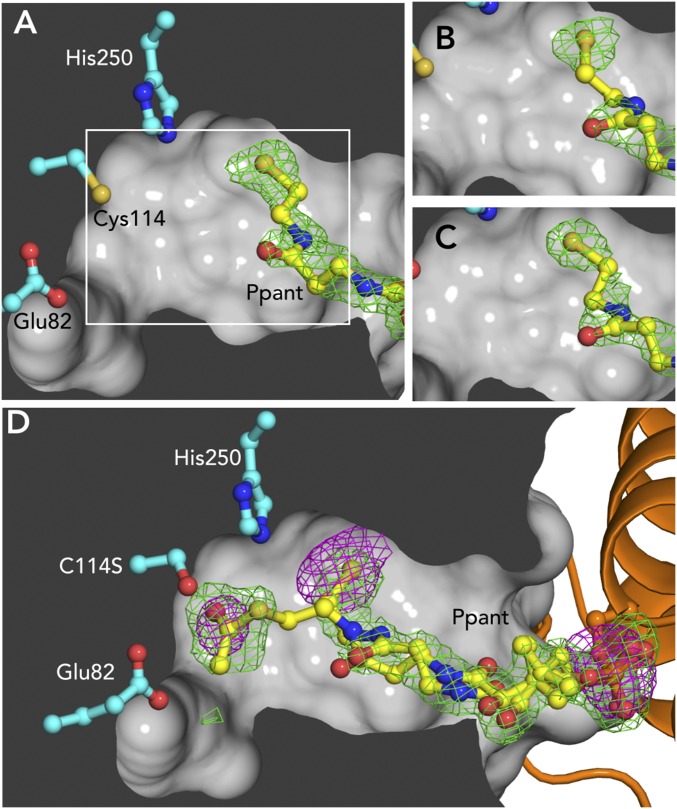

Acetylation-dependent position of Ppant. Panels show Fo-Fc omit density (3σ, Ser-Ppant omitted, green) for structures of ACPD-HMGS in different biochemical states crystallized in identical conditions. (A) Holo-ACPD and HMGSWT. White box indicates field of view for B and C. (B) Acetyl-ACPD and HMGSWT, showing that the acetyl group has been lost. (C) Holo-ACPD and HMGSC114S. (D) Acetyl-ACPD and HMGSC114S. Anomalous difference density (3σ, magenta) indicates that S is present in both terminal densities for the Ppant and also shows the Ppant P atom. Atoms are colored as in Fig. 3.

In the holo-ACPD/HMGS structure, the Ppant and Cys114 thiol groups are too far apart (7.9 Å) for the acetyl-transfer step of HMGS catalysis (Fig. 4A). This distal Ppant position was also occupied in crystals grown from acetyl-ACPD + HMGS, with no density for an acetyl at either the Ppant or Cys114 (Fig. 4B and Table S3). The acetyl group of acetyl-ACPD was apparently transferred to Cys114 and subsequently hydrolyzed during crystallization (2–3 d) (Table S2). We propose that the distal Ppant position represents a post acetyl-transfer state. Nonproductive loss of the acetyl-CoA donor in absence of the acetoacetyl-CoA acceptor has also been reported for HMGCS (23).

To trap an acetyl-ACPD complex, we cocrystallized the inactive HMGSC114S with acetyl-ACPD, resulting in multiple positions for the Ppant terminus (Fig. 4D), including the previously identified distal holo-Ppant position, again lacking density for an acetyl group. A second position was interpreted from a new strong density (15σ) near Ser114 that could represent acetyl-Ppant (Fig. 4D). Two experiments validated the interpretation of the second proximal acetyl-Ppant position, as its density was discontinuous with the rest of the Ppant. We solved the structure of holo-ACPD/HMGSC114S, yielding density in the distal Ppant position and no density in the Ser114-proximal position, establishing that the new density was not due to the C114S substitution (Fig. 4C and Table S3). To distinguish whether the density near Ser114 was due to free acetate or the acetyl-Ppant terminus, we used anomalous scattering to identify atomic positions of S atoms. Data were recorded at an X-ray energy of 7.0 keV from acetyl-ACPD/HMGSC114S cocrystals, yielding anomalous difference electron density for the Ppant S in both the distal site and at the site proximal to Ser114 (Fig. 4D and Table S3). A similar experiment with HMGSC114S crystals (no ACPD) lacked anomalous difference electron density near Ser114. Thus, we conclude that during crystallization some of the acetyl-ACPD hydrolyzed spontaneously, and the remaining acetyl-Ppant was adjacent to the nucleophilic side chain (C114S), defining a preacetyl-transfer position.

ACPD/HMGS Interface.

The interacting surfaces of ACPD and HMGS are complementary in shape and charge (Fig. 3 C and D and Fig. S6 A and B). The primary contact is between the N-terminal half of HMGS helix α8 (Fig. 3) and an ACPD cleft between the Ppant-Ser39 and helix III. On the ACPD surface, conserved basic residues form a strongly electropositive region, which is separated from an electronegative region by a hydrophobic stripe (Fig. S6). We compared the surface features of other ACPs in complexes with cognate enzymes (24–29) to ACPD (Fig. S6). Positive and negative surface regions are typical of PKS ACPs (Fig. S6 B–E), whereas fatty acid synthase (FAS) ACPs are highly electronegative (Fig. S6 F–I). Among PKS ACPs, ACPD has two distinctive features: a strongly electropositive region and a cleft that is complementary to a conserved hydrophobic patch (Fig. 3D) (Leu217, Leu218) on the outer surface of HMGS helix α8. The analogous surface of the HMGCS helix is polar.

Fig. S6.

Electrostatic surface potentials and interacting surfaces for HMGS and selected ACPs. For ACPs from structures of enzyme complexes, the black outline delineates the molecular surface within 5 Å of any atom in the interacting enzyme and the yellow star denotes the site of Ppant attachment. (A) CurD HMGS (complex with CurB ACPD). (B) CurB holo-ACPD (complex with CurD HMGS). (C) CurA ACPA [2LIW (24); RMSD 2.2 Å]. (D) DEBS module 2 ACP [2JU2 (25); RMSD 2.7 Å]. (E) VinL ACP [5CZD (31); complex with VinK Acyltransferase, RMSD 2.6 Å]. (F) E. coli AcpP [complex with E. coli FabA dehydratase, 4KEH (26); RMSD 2.1 Å]. (G) E. coli AcpP [complex with E. coli LpxD, 4IHG (27); RMSD 3.5 Å]. (H) B. subtilis ACP [complex with B. subtilis ACP synthase, 1F80 (29); RMSD = 2.2 Å]. (I) R. communis ACP [complex with R. communis ACP desaturase, 2XZ1 (28); RMSD 1.7]. Molecular surfaces are colored by electrostatic potential (±5 kT/e, blue electropositive, red electronegative) (57). RMSD values are from Cα superposition with CurB ACPD.

We evaluated several salt bridges in the ACPD-HMGS interface by mutagenesis and, for each variant, measured HMGS activity and ACPD affinity (Table 1 and Figs. S2 and S5). Each of the HMGS charged residues (Arg33, Asp214, Asp222, Glu225, and Arg266) was substituted with alanine and an oppositely charged amino acid. Affinities were measured by fluorescence anisotropy with a fluorophore-conjugated ACPD. The HMGS Kd was 1.1 μM for apo-ACPD and 0.5 μM for holo-ACPD, indicating significant protein-protein affinity and a twofold contribution from the Ppant cofactor. Asp222, Glu225, and Arg266 are involved in only the protein-protein interface and do not contact the Ppant (Fig. 3C). Correspondingly, substitutions to these residues had a greater impact on the affinity of apo-ACPD than holo-ACPD. Substitutions to phosphate-interacting Arg33 and Asp214 resulted in equal affinities for holo and apo-ACPD.

Fig. S5.

Affinity of ACPD for WT and variant HMGS. Fluorescence anisotropy of BODIPY-tagged ACPD was recorded as a function of HMGS concentration. For each HMGS variant, binding curves are shown for apo-ACPD (Left) and holo-ACPD (Right). Data were recorded and analyzed with Graphpad Prism. Data represent the average of three measurements.

The effect of the HMGS substitutions on activity did not show a clear pattern for Ppant-interacting and protein-protein contact residues. The Arg33 variants had little or no activity, suggesting that the Arg33 may orient Ppant in the active site. In contrast, substitutions to Asp214 did not significantly affect activity. To further test the importance of HMGS-Ppant interactions, we made alanine substitutions to Ser167 and to Pro166, which we hypothesized would increase helicity of Phe163 and prevent its carbonyl from interacting with Ppant. Despite the conservation of these residues, both variants had similar activity to WT HMGS, suggesting their interaction with Ppant may be unimportant for the acetylation step of the HMGS mechanism.

Substitutions to charged side chains in the protein-protein interface caused modest reductions in HMGS activity that were not correlated with changes in affinity, indicating that HMGS-ACPD affinity is not limiting in the assay conditions. At each position, the effect of the charge-reversal substitution was more deleterious to HMGS activity (3- to 10-fold) than was the Ala substitution (threefold or less). The greatest effects occurred for charge-reversal substitutions at Asp222 (5-fold) and Glu225 (10-fold). Located on adjacent turns of helix α8 (Fig. 3C), Glu225 forms a salt bridge with ACPD Arg59, and the Asp222 carboxylate “caps” ACPD helix III, which is an atypical 310 helix in an unusual position in the ACP (Fig. 3). Thus, Asp222 and Glu225 may help orient ACPD on HMGS, or may be antiselective for ACPA at this position.

The ACPD-HMGS interface provides clues about the selectivity of β-branching in the myxovirescin pathway, which generates methyl and ethyl branches with two ACPD/HMGS pairs (TaB/TaC and the nonstandard TaE/TaF) (30). Each HMGS (TaC and TaF) is selective for its donor ACP (acetyl-TaB and propionyl-TaE) (16). Homology models of the myxovirescin ACPDs and HMGSs accounted for the selectivity, as the TaB/TaC pair retains most of the interactions of CurB/CurD, however, at other interacting positions, complementary sequence changes in TaE ACPD and TaF were incompatible with the noncognate partner.

Discussion

HMGS catalyzes the key reaction of polyketide β-branching, a critical process for chemical diversification in this important class of natural products. The β-branching HMGS of the curacin A biosynthetic pathway exhibits a remarkable selectivity for its donor (ACPD) and acceptor (ACPA) substrates (Table 1), like related enzymes (15–17). This selectivity enables proper sequencing of substrates during catalysis and prevents aberrant β-branching by mis-association with other ACPs within the PKS pathway.

The ACPD-HMGS structures capture the ACPD Ppant in pre- and postacetyl transfer positions. In the Cys-distal, postacetyl-transfer position, the Ppant thiol was bound deep within a conserved thiol pocket that occludes the acetyl group, whereas the poorly ordered acetyl-Ppant was in the Cys-proximal position (captured in the Ser114 variant). These positions contrast with structures of HMGCS-CoA complexes (9–11, 13, 14) where, in all cases supported by electron density, the Ppant was bound near the distal site with the thiol directed into the active site cavity regardless of its acylation state. Nevertheless, the HMGS and HMGCS active sites are nearly identical, and thus we infer that HMGS and HMGCS have identical stereochemical outcome, generating only S-HMG products.

A major motivation for our study was to investigate how HMGS distinguishes the two ACP substrates. The structures of the ACPD-HMGS complexes indicate that HMGS excludes ACPA from the ACPD site, consistent with the inability of ACPA to act as an acetyl donor in the reaction (Table 1). ACPD has a surface shape that is complementary to the HMGS surface and that differs from surfaces of ACPA and other ACPs. A hydrophobic cleft, due to the unique position of ACPD helix III, is matched with a hydrophobic ridge on the surface of HMGS helix α8 (amino acids 213–234) and is flanked by polar contacts, including Asp222 on helix α8 with backbone amides at the N terminus of ACPD helix III. ACPA has no hydrophobic surface cleft because helix III is in a more typical position. None of the salt bridges between amino acids in ACPD and HMGS was critical for binding or catalysis when tested by single-residue mutagenesis (Table 1), leading us to conclude that surface complementarity is the dominant factor in the HMGS-ACPD interface.

ACPs from PKS pathways (18, 24, 25, 31) have distinctive surface charge distributions compared with FAS ACPs (26–29), but in both systems the ACP helix II-III surface interacts with enzymes (Fig. S6). The PKS ACPs have regions of positive surface potential near the point of contact with their cognate enzymes, whereas the analogous surface of the FAS ACPs is negatively charged. The distinctive pattern of negative/neutral/positive surface potential of β-branching ACPs (ACPD, curacin A, and mupirocin ACPAs) may contribute to HMGS selectivity against the ACPs within PKS modules where the surface potential pattern differs (Fig. S6). The unusual ACPD helix III, accompanying surface cleft, and striking electrostatics specialize ACPD for selective interaction with only the β-branching HMGS and KSDC enzymes (Fig. S1). In contrast, ACPA shuttles substrates to seven enzymes in the curacin A pathway, including β-branching and module enzymes, necessitating a more promiscuous ACP-surface for enzyme interaction.

Catalytic fidelity in a reaction with distinct donor and acceptor substrates is a common problem for HMGS and two homologs: the HMGCS of primary metabolism and the KS domain of modular PKS pathways. The enzymes use different mechanisms of substrate selectivity, although they have analogous active site entrances for their acyl donor substrates. HMGCS has a single binding site for the acetyl-donor and acetoacetyl-acceptor CoAs (10, 14), but excludes the acetyl-CoA donor following acetyl transfer to the enzyme (32). Like HMGS, the PKS KS domain has two ACP substrates but uses separate active site entrances for the donor (upstream module) and acceptor (intramodule) (19). The PKS KS restricts access of each ACP to the appropriate entrance by the module architecture and ACP tethering via fusion or interaction of docking domains (19–21, 33, 34). In contrast, HMGS interacts with two ACPs in trans, and robust binding of ACPD (Kd = 0.5 μM for holo-ACPD) is not acyl-group dependent. Nor is the ACPD docking site on HMGS analogous to either of the ACP-KS docking sites observed in cryo-EM maps of a PKS module (19). We find no evidence of a second active site entrance in the HMGS structure (for example, poorly ordered loops that could expose the active site, as in the KS) (19, 21, 35, 36). We conclude that ACPA and ACPD insert acyl-Ppant through the same active site entrance, as do the donor and acceptor-CoAs of HMGCS, but that the ACPs interact with different regions of the HMGS surface.

The HMGS flexible loop, which does not exist in either HMGCS or KS, is a prime candidate for ACPA interaction, as it is adjacent to the active site. A critical question is whether the ACPs engage HMGS simultaneously or sequentially. The affinity of HMGS for ACPD is tenfold greater than a native docking domain pair (Kd = 0.5 μM vs. 5–25 μM) (20, 21). HMGS has lower affinity for ACPA than for ACPD, based on the Kd of 150–200 μM for the bryostatin HMGS and its cognate ACPA (15). Cooperativity may enhance weak intrinsic ACPA binding to HMGS because β-branching cassettes typically encode tandem ACPAs, for example the CurA tandem ACPA tridomain of nearly identical sequences with an additional dimerization element at the C terminus (37). In the HMGS dimer, the two active site entrances are separated by 40–50 Å, a distance that may be spanned by tandem or dimeric ACPs. However, the high activity of HMGS under assay conditions with equal concentrations of ACPD and single-domain ACPA implies that HMGS may either promote dissociation of ACPD, following acetyl transfer to Cys114, or simultaneously engage acetoacetyl-ACPA to prevent formation of a dead-end complex. Thus, interaction with acetoacetyl-ACPA could trigger both catalytic and conformational events, including rearrangement of the flexible loop to disengage ACPD or to widen the active site entrance to accommodate two Ppant cofactors. The possibilities are not resolved by the present structures.

In conclusion, the first structure of an HMG synthase involved in polyketide biosynthesis reveals features that distinguish HMGS from its primary metabolism homolog and allow it to interact selectively with its cognate ACPs. Analysis of the HMGS-ACPD interface provides insight into HMGS selectivity in other pathways, including those with multiple β-branching functions. The HMGS structures with acetyl and holo-ACPD provide a unique view of the molecular interactions between a PKS enzyme and its substrate, revealing the mechanism by which HMGS prevents its substrate from adopting a nonproductive orientation in the active site. Finally, the unusual position of helix III in ACPD is a new structural motif in acyl carrier proteins that can be selectively recognized by specialized enzymes such as HMGS.

Methods

Constructs encoding curacin A HMGS, ACPD, and ACPA and variants (Table S4) were expressed in E. coli and purified by IMAC and size exclusion chromatography. HMGS activity was assayed by LC-MS with Ppant ejection to detect conversion of acetoacetyl-ACPA to HMG-ACPA. HMGS affinity for ACDD was measured by fluorescence anisotropy using a labeled variant of ACPD. HMGS and ACPD/HMGS complexes were crystallized by hanging drop vapor diffusion. X-ray diffraction data were collected at GM/CA at the Advanced Photon Source. Homology models of the myxovirescin HMGS and ACPDs were generated using Modeller.

Table S4.

Primers for cloning and mutagenesis of CurD HMGS and CurB ACPD

| Construct | Sense primer | Antisense primer |

| Cloning primers (construct) | ||

| pHMGScur | TACTTCCAATCCAATGCTATGCAACAAGTTGGC | TTATCCACTTCCAATGCTATACCCACTCGTATTTTCGG |

| pACPDcur | TACTTCCAATCCAATGCAATGAGCAAgGAACAAGTAC | TTATCCACTTCCAATGCTACAATTTTGCTGCA |

| Mutagenic primers (mutation) | ||

| HMGS: C114S | tttgaactcaagcaagctagctactcaggaaccg | cggttcctgagtagctagcttgcttgagttcaaa |

| HMGS: AAA | gggctgatataccttgttgagctgcaattgccgccccttctggagtcacaaccccac | gtggggttgtgactccagaaggggcggcaattgcagctcaacaaggtatatcagccc |

| HMGS: P166A | ccagcaccactactggcttcagcaaaagaccaatc | gattggtcttttgctgaagccagtagtggtgctgg |

| HMGS: S167A | ggctccagcaccactagcgggttcagcaaaagac | gtcttttgctgaacccgctagtggtgctggagcc |

| HMGS: R33A | catcattagattgtcaaaggcggagatatccaactgacgc | gcgtcagttggatatctccgcctttgacaatctaatgatg |

| HMGS: D214A | aagaaagcaaggataaggcggcatctcctgcttct | agaagcaggagatgccgccttatccttgctttctt |

| HMGS: D222A | taggcattttcgcaacaggctaggtaagaaagcaagg | ccttgctttcttacctagcctgttgcgaaaatgccta |

| HMGS: E225A | taatgtcggtaggcatttgcgcaacagtctaggtaag | cttacctagactgttgcgcaaatgcctaccgacatta |

| HMGS: R266A | ggtttagctcttttcaacctagccatcatatttctatgagcgcc | ggcgctcatagaaatatgatggctaggttgaaaagagctaaacc |

| HMGS: R33D | tcatcattagattgtcaaagtcggagatatccaactgacgcg | cgcgtcagttggatatctccgactttgacaatctaatgatga |

| HMGS: D214R | gtaagaaagcaaggataagcgggcatctcctgcttctgaa | ttcagaagcaggagatgcccgcttatccttgctttcttac |

| HMGS: D222R | ggcattttcgcaacagcgtaggtaagaaagcaaggataagtc | gacttatccttgctttcttacctacgctgttgcgaaaatgcc |

| HMGS: E225R | ttgataatgtcggtaggcatttctgcaacagtctaggtaagaaagc | gctttcttacctagactgttgcagaaatgcctaccgacattatcaa |

| HMGS: R266E | gcaggtttagctcttttcaacctctccatcatatttctatgagcgcctt | aaggcgctcatagaaatatgatggagaggttgaaaagagctaaacctgc |

| ACPD: M1C | atttttagtacttgttctttgctgcatgcattggattggaagtacaggttctcg | cgagaacctgtacttccaatccaatgcatgcagcaaagaacaagtactaaaaat |

| ACPD: R42A | catcatgataatttctgccgcattaactgaatcgatacctaatttttttaagctatca | tgatagcttaaaaaaattaggtatcgattcagttaatgcggcagaaattatcatgatg |

Ligation independent cloning (LIC) overhangs are bolded.

SI Methods

Protein Expression and Purification.

Our expression plasmid for the curacin A HMGS (pHMGScur) was generated by amplifying the CurD gene from the pLM54 (6) cosmid (Table S4) and inserting it into pMCSG7 (38) by ligation independent cloning (LIC). The curB gene encoding ACPD was amplified from a pET28b construct (38) (Table S4) and inserted by LIC into pMCSG7 (pACPdcur). Screening of expression conditions for pHMGScur yielded a stable, soluble preparation by coexpression of with pGro7 (39) (Takara) in E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells. pACPDcur was coexpressed with pRARE-CDF (21) in E. coli BL21 (DE3) (for apo/acyl-loaded proteins) or Bap1 (40) (for holo proteins) cells containing pRARE. E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells were transformed with pLG003 (37) for expression of CurA ACP II, the second of the CurA tandem ACPA tridomain. Transformed bacteria were grown with 100 mg/L ampicillin and 35 mg/L chloramphenicol for HMGS, 100 mg/L ampicillin and 50 mg/L spectinomycin for ACPD, or 50 mg/L kanamycin for ACPA at 37 °C in terrific broth (TB) to an OD600 of 1. GroEL/ES chaperone expression was induced with 2 g/L arabinose for HMGS cultures at an OD600 of 0.3. Cells were cooled to 20 °C and target gene expression was induced with 200 μM Isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). After 18 h of expression, cells were harvested and stored at −20 °C. Cell pellets were resuspended in buffer A [300 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 20 mM imidazole, pH 8.0, and 10% (vol/vol) glycerol for ACPs; 50 mM (NH4)2SO4, 50 mM Hepes, pH 7.0, 20 mM imidazole, pH 8.0, and 10% (vol/vol) glycerol for HMGS]. Cell suspensions were treated with 1 mg/mL lysozyme (Sigma), 2 mM MgCl2, and 20 U/mL Pierce universal nuclease for 30 min at room temperature and then cooled on ice. Cells were lysed by sonication and cleared by centrifugation. Each protein was purified by immobilized metal affinity chromatography on a 5 mL His Trap column (GE Healthcare) with a 50-mL gradient from 20 mM (buffer A) to 400 mM imidazole (buffer B), followed by size exclusion chromatography (SEC). HMGS was purified on a Superdex S200 column in 50 mM (NH4)2SO4, 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.0, and 10% (vol/vol) glycerol (HMGS buffer C), and ACPs on a Superdex S75 column in 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, and 10% (vol/vol) glycerol (ACP buffer C). Proteins were concentrated to ∼10 mg/mL, flash cooled in liquid N2, and stored at −80 °C.

Site-Directed Mutagenesis.

Constructs encoding HMGS and ACPD variants were generated by site-directed mutagenesis (SDM) on pHMGScur and pACPDcur by PCR with overlapping primers (Table S4). SDM PCR components were 2 ng/μL pHMGScur or pACPDcur, 200 nM sense and 200 nM antisense primer, 0.05 U/μL Pfu Turbo polymerase (Agilent), and 250 nM dNTPs, in 1× Pfu buffer (Agilent). After PCR, 0.4 U/μL DpnI (NEB) was added to each reaction and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. Two microliters of this mixture was transformed into E. coli XL-1 Blue cells. Mutant expression constructs were purified by miniprep kit (Qiagen), and the mutations were verified by Sanger sequencing.

Activity Assay.

ACPs in the apo state were loaded in vitro with acyl-Ppants by incubation with Streptomyces verticillus phosphopantetheinyl transferase (41) (SVP), in a 10:1 ratio of ACP:SVP, and acyl-CoA, in a 1:10 ratio of ACP:CoA, in a buffer of 10 mM MgCl2, 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, for 3 h at 30 °C. Acylated ACPs were purified from loading reaction components by SEC on a Superdex S75 column equilibrated with ACP buffer C. The HMGS assays were performed at 25 °C in a buffer of 20 mM (NH4)2SO4, 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.0, and 2 mM Tris (2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) for 10 min, followed by quenching with 5% (vol/vol) formic acid. The concentrations of assay components were 5 μM HMGS, 50 μM acetyl-ACPD, and 50 μM acetoacetyl-ACPA. ACPA was separated from other reaction components by HPLC on a Jupiter C4 column with a gradient of 30–95% (vol/vol) acetonitrile in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) over 15 min with a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min. The ACPA peak fraction was stored at −20 °C until MS analysis by Q-TOF (Agilent) with phosphopantetheine ejection (22). Total ion counts for holo, acetyl, acetoacetyl, and HMG-loaded Ppant species were recorded (Agilent MassHunter software). Reaction progress was calculated by the percent of all ejected Ppant ions loaded with HMG and averaged for three replicates.

ACPD Hydrolysis Assay.

Acetyl-ACPD (100 μM) was incubated 18 h at 20 °C in a 20 mM (NH4)2SO4 + 1× MES:malic acid:tris buffer (MMT), pH 6.5 (Qiagen), with 10 μΜ HMGSWT, 10 μM HMGSC114S, or alone. Samples were acidified with 5% (vol/vol) formic acid and analyzed by HPLC and MS Ppant ejection as described above. An additional 100 μM acetyl-ACPD was analyzed without incubation. Percent loading of the ACPD with acetyl was determined using ion counts for acetyl-Ppant and holo-Ppant species.

Fluorescence Anisotropy Binding Assay.

Met1 of CurB ACPD was mutagenized to cysteine. ACPD M1C was reduced for 15 min at room temperature with 2 mM TCEP and then incubated with 10-fold excess BODIPY-FL 1-iodoacetamide [N-(4,4-difluoro-5,7-dimethyl-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene-3-yl)methyl)iodoacetamide)] (ThermoFischer) at room temperature for 3 h. BODIPY-FL–conjugated ACPD was purified from free BODIPY using a PD-10 column with ACP buffer C, flash frozen, and stored at −80 °C. HMGS was dialyzed overnight at 4 °C into 20 mM (NH4)2SO4 and 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.0. Ten serial 2× dilutions of the HMGS stocks were made, and then 45 μL of each of these 11 HMGS samples was mixed with 5 μL 0.1 nM ACPD-1-BODIPY in an opaque 384-well plate; 45 μL buffer was mixed with 5 μL 0.1 nM ACPD-1-BODIPY for a control. The plate was incubated at room temperature for 30 min, and then fluorescence anisotropy was measured with a λEX of 485 nm and λEM of 525 nm. The data were fit to A = Afree + {ΔAbound × [HMGS]/(Kd + [HMGS])} (GraphPad Prism) to determine affinities. In cases where ΔAbound, the change in anisotropy when ACPD is maximally bound, could not be fit from the data, ΔAbound was held at a constant value as determined from the average of trials where it was experimentally measured.

Crystallization.

WT HMGS was recalcitrant to crystallization, and we therefore engineered a series of alanine substitutions at adjacent polar residues to HMGS to make it more amenable to crystallization, guided by predictions of the surface entropy reduction server (42) and an HMGCS of known structure (11). Using these predictions, a triple alanine variant, HMGSAAA, (K344A/Q345A/Q347A) was generated by SDM. HMGSAAA was crystallized by hanging-drop vapor diffusion from 1:1 and 2:1 mixtures of protein stock (10 mg/mL in HMGS buffer C) and well solution [20 mM (NH4)2SO4, 1× MMT buffer pH 6.5 (Qiagen), 6% (wt/vol) PEG 8000] at 20 °C. For HMGS/ACPD complex crystals, each protein was concentrated to 25 mg/mL and then mixed in an HMGS:ACPD ratio of 2:3, for a sevenfold molar ratio of ACPD:HMGS. HMGS/ACPD (apo) cocrystals were obtained with a well solution of 100 mM (NH4)2SO4, 1× MMT buffer, pH 6.5, and 2% (wt/vol) PEG 8000. HMGS/ACPD (holo) crystallized with a well solution of 120 mM (NH4)2SO4, 1× MMT buffer, pH 6.5, and 10% (wt/vol) PEG 8000 at 20 °C. Crystals were cryoprotected in well solution with 25% (vol/vol) glycerol before flash cooling in liquid N2. Crystallization trials using refined conditions and HMGSWT (again cocrystallized with a 7:1 molar ratio of ACPD:HMGS) yielded only microcrystals that were not suitable for harvesting or diffraction.

Structure Solution and Refinement.

Data were collected at the Advanced Photon Source (APS) GM/CA 23ID-D and processed with XDS (43). Diffraction limits were determined by CC1/2 and I/σI statistics, and subsequent calculations were done with the ccp4 suite (44). The HMGS structure was solved by molecular replacement in phaser (45) from an HMG-CoA synthase model (11) (1YSL) that was trimmed with chainsaw (46). A 97%-complete initial model was auto-built using ARP/wARP (47), model refinement was done in refmac5 (48) with TLS (49) parameters, and real space building was done with Coot (50). The three alanine substitutions in HMGSAAA were not directly involved in a crystal contact, and only one was surface exposed. Waters were manually added in coot to positive FO-FC difference density in positions consistent with hydrogen bonding to the protein. Waters were removed after refinement if they corresponded to negative difference density, had 2Fo-Fc density weaker than 0.6σ, or resulted in clashes. HMGS/ACPD complex structure was solved by molecular replacement with the HMGS structure, followed by manual building of the ACPD model in Coot and refinement in refmac5 with TLS parameters. Despite high B-factors for residues distal from HMGS that had no crystal contacts, we found continuous main chain density for residues 1–78 in all deposited structures, and density for side chains contacting HMGS was well resolved. Subsequent HMGS/ACPD complex structures were solved by rigid body refinement with HMGS and ACPD models. To validate the Ppant position in our model of the preacetyl transfer complex, we collected data on holo-ACPD/HMGSC114S crystals at 12 keV and Friedel-pair data at an X-ray energy of 7 keV on acetyl-ACPD/HMGS (C114S) and HMGS (C114S) crystals. Data were processed with XDS and phased by rigid body refinement in refmac5. Following model refinement and addition of waters, sulfur atomic positions were identified in an anomalous difference map The peak heights for the holo and acetyl thiol positions were 4.0 and 3.7, respectively, and peaks for cysteines and methionines ranged from 4.0 to 8.1. Refined models were validated by Molprobity (51), followed by a final round of building in coot and refinement in refmac5. Molecular figures were generated in PyMOL (52).

Homology Modeling of Myxovirescin HMGS and ACPD.

Homology models of the TaB and TaE ACPDs and of the TaC and TaF HMGSs were generated using Modeller (53) using sequence alignments by Clustal Omega (22) (Figs. S3 and S4) and our structure of the holo-ACPD/HMGS complex. Models for TaC and TaF were aligned to CurD HMGS, and models for the TaB and TaE ACPDs were aligned to holo-CurB ACPD in PyMOL for analysis of the TaB/TaC and TaE/TaF complexes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by US NIH Grants R01-DK042303 (to J.L.S.), R01-CA108874 (to D.H.S., J.L.S., and W.H.G.), and the Hans W. Vahlteich Professorship (D.H.S.). The GM/CA at APS beamlines are funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Cancer Institute (CA) (ACB-12002) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (GM) (AGM-12006). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a US Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. C.K. is a Guest Editor invited by the Editorial Board.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID codes 5KP5, 5KP6, 5KP7, and 5KP8).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1607210113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Cragg GM, Newman DJ. Natural products: A continuing source of novel drug leads. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1830(6):3670–3695. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weissman KJ. Genetic engineering of modular PKSs: From combinatorial biosynthesis to synthetic biology. Nat Prod Rep. 2016;33(2):203–230. doi: 10.1039/c5np00109a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calderone CT. Isoprenoid-like alkylations in polyketide biosynthesis. Nat Prod Rep. 2008;25(5):845–853. doi: 10.1039/b807243d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blokhin AV, et al. Characterization of the interaction of the marine cyanobacterial natural product curacin A with the colchicine site of tubulin and initial structure-activity studies with analogues. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;48(3):523–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verdier-Pinard P, et al. Structure-activity analysis of the interaction of curacin A, the potent colchicine site antimitotic agent, with tubulin and effects of analogs on the growth of MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;53(1):62–76. doi: 10.1124/mol.53.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang Z, et al. Biosynthetic pathway investigations and gene cluster of curacin A, an antitubulin natural product from the tropical marine cyanobacterium Lyngbya majuscula. Gene. 2004;67(1):1356–1367. doi: 10.1021/np0499261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gu L, et al. Metamorphic enzyme assembly in polyketide diversification. Nature. 2009;459(7247):731–735. doi: 10.1038/nature07870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miziorko HM. Enzymes of the mevalonate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2011;505(2):131–143. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Theisen MJ, et al. 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase intermediate complex observed in “real-time”. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(47):16442–16447. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405809101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campobasso N, et al. Staphylococcus aureus 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase: Crystal structure and mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(43):44883–44888. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407882200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steussy CN, et al. X-ray crystal structures of HMG-CoA synthase from Enterococcus faecalis and a complex with its second substrate/inhibitor acetoacetyl-CoA. Biochemistry. 2005;44(43):14256–14267. doi: 10.1021/bi051487x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skaff DA, et al. Biochemical and structural basis for inhibition of Enterococcus faecalis hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA synthase, mvaS, by hymeglusin. Biochemistry. 2012;51(23):4713–4722. doi: 10.1021/bi300037k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pojer F, et al. Structural basis for the design of potent and species-specific inhibitors of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA synthases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(31):11491–11496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604935103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shafqat N, Turnbull A, Zschocke J, Oppermann U, Yue WW. Crystal structures of human HMG-CoA synthase isoforms provide insights into inherited ketogenesis disorders and inhibitor design. J Mol Biol. 2010;398(4):497–506. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buchholz TJ, et al. Polyketide β-branching in bryostatin biosynthesis: Identification of surrogate acetyl-ACP donors for BryR, an HMG-ACP synthase. Chem Biol. 2010;17(10):1092–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calderone CT, Iwig DF, Dorrestein PC, Kelleher NL, Walsh CT. Incorporation of nonmethyl branches by isoprenoid-like logic: Multiple β-alkylation events in the biosynthesis of myxovirescin A1. Chem Biol. 2007;14(7):835–846. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calderone CT, Kowtoniuk WE, Kelleher NL, Walsh CT, Dorrestein PC. Convergence of isoprene and polyketide biosynthetic machinery: Isoprenyl-S-carrier proteins in the pksX pathway of Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(24):8977–8982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603148103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haines AS, et al. A conserved motif flags acyl carrier proteins for β-branching in polyketide synthesis. Nat Chem Biol. 2013;9(11):685–692. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dutta S, et al. Structure of a modular polyketide synthase. Nature. 2014;510(7506):512–517. doi: 10.1038/nature13423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buchholz TJ, et al. Structural basis for binding specificity between subclasses of modular polyketide synthase docking domains. ACS Chem Biol. 2009;4(1):41–52. doi: 10.1021/cb8002607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whicher JR, et al. Cyanobacterial polyketide synthase docking domains: A tool for engineering natural product biosynthesis. Chem Biol. 2013;20(11):1340–1351. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dorrestein PC, et al. Facile detection of acyl and peptidyl intermediates on thiotemplate carrier domains via phosphopantetheinyl elimination reactions during tandem mass spectrometry. Biochemistry. 2006;45(42):12756–12766. doi: 10.1021/bi061169d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miziorko HM, Lane MD. 3-Hydroxy-3-methylgutaryl-CoA synthase. Participation of acetyl-S-enzyme and enzyme-S-hydroxymethylgutaryl-SCoA intermediates in the reaction. J Biol Chem. 1977;252(4):1414–1420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Busche A, et al. Characterization of molecular interactions between ACP and halogenase domains in the Curacin A polyketide synthase. ACS Chem Biol. 2012;7(2):378–386. doi: 10.1021/cb200352q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alekseyev VY, Liu CW, Cane DE, Puglisi JD, Khosla C. Solution structure and proposed domain domain recognition interface of an acyl carrier protein domain from a modular polyketide synthase. Protein Sci. 2007;16(10):2093–2107. doi: 10.1110/ps.073011407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nguyen C, et al. Trapping the dynamic acyl carrier protein in fatty acid biosynthesis. Nature. 2014;505(7483):427–431. doi: 10.1038/nature12810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masoudi A, Raetz CRH, Zhou P, Pemble CW., 4th Chasing acyl carrier protein through a catalytic cycle of lipid A production. Nature. 2014;505(7483):422–426. doi: 10.1038/nature12679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guy JE, et al. Remote control of regioselectivity in acyl-acyl carrier protein-desaturases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(40):16594–16599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110221108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parris KD, et al. Crystal structures of substrate binding to Bacillus subtilis holo-(acyl carrier protein) synthase reveal a novel trimeric arrangement of molecules resulting in three active sites. Structure. 2000;8(8):883–895. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00178-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simunovic V, et al. Myxovirescin A biosynthesis is directed by hybrid polyketide synthases/nonribosomal peptide synthetase, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthases, and trans-acting acyltransferases. ChemBioChem. 2006;7(8):1206–1220. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200600075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miyanaga A, Iwasawa S, Shinohara Y, Kudo F, Eguchi T. Structure-based analysis of the molecular interactions between acyltransferase and acyl carrier protein in vicenistatin biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(7):1802–1807. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1520042113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Middleton B. The kinetic mechanism of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A synthase from baker’s yeast. Biochem J. 1972;126(1):35–47. doi: 10.1042/bj1260035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Broadhurst RW, Nietlispach D, Wheatcroft MP, Leadlay PF, Weissman KJ. The structure of docking domains in modular polyketide synthases. Chem Biol. 2003;10(8):723–731. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(03)00156-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whicher JR, et al. Structural rearrangements of a polyketide synthase module during its catalytic cycle. Nature. 2014;510(7506):560–564. doi: 10.1038/nature13409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang Y, Kim C-Y, Mathews II, Cane DE, Khosla C. The 2.7-Angstrom crystal structure of a 194-kDa homodimeric fragment of the 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(30):11124–11129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601924103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tang Y, Chen AY, Kim C-Y, Cane DE, Khosla C. Structural and mechanistic analysis of protein interactions in module 3 of the 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase. Chem Biol. 2007;14(8):931–943. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gu L, et al. Tandem acyl carrier proteins in the curacin biosynthetic pathway promote consecutive multienzyme reactions with a synergistic effect. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011;50(12):2795–2798. doi: 10.1002/anie.201005280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stols L, et al. A new vector for high-throughput, ligation-independent cloning encoding a tobacco etch virus protease cleavage site. Protein Expr Purif. 2002;25(1):8–15. doi: 10.1006/prep.2001.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nishihara K, Kanemori M, Kitagawa M, Yanagi H, Yura T. Chaperone coexpression plasmids: Differential and synergistic roles of DnaK-DnaJ-GrpE and GroEL-GroES in assisting folding of an allergen of Japanese cedar pollen, Cryj2, in Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64(5):1694–1699. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.5.1694-1699.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pfeifer BA, Admiraal SJ, Gramajo H, Cane DE, Khosla C. Biosynthesis of complex polyketides in a metabolically engineered strain of E. coli. Science. 2001;291(5509):1790–1792. doi: 10.1126/science.1058092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sánchez C, Du L, Edwards DJ, Toney MD, Shen B. Cloning and characterization of a phosphopantetheinyl transferase from Streptomyces verticillus ATCC15003, the producer of the hybrid peptide-polyketide antitumor drug bleomycin. Chem Biol. 2001;8(7):725–738. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(01)00047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goldschmidt L, Cooper DR, Derewenda ZS, Eisenberg D. Toward rational protein crystallization: A Web server for the design of crystallizable protein variants. Protein Sci. 2007;16(8):1569–1576. doi: 10.1110/ps.072914007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kabsch W. Xds. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 2):125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Winn MD, et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67(Pt 4):235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCoy AJ, et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Cryst. 2007;40(Pt 4):658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stein N. CHAINSAW: A program for mutating pdb files used as templates in molecular replacement. J Appl Cryst. 2008;41(3):641–643. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Langer G, Cohen SX, Lamzin VS, Perrakis A. Automated macromolecular model building for X-ray crystallography using ARP/wARP version 7. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(7):1171–1179. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53(Pt 3):240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Painter J, Merritt EA. Optimal description of a protein structure in terms of multiple groups undergoing TLS motion. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62(Pt 4):439–450. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906005270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 4):486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen VB, et al. MolProbity: All-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 1):12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schrödinger LLC. 2014. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.7.4.3. Available at www.pymol.org.

- 53.Eswar N, et al. Comparative protein structure modeling using MODELLER. Curr Protoc Protein Sci. 2007;2(2.9):1–31. doi: 10.1002/0471140864.ps0209s50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sievers F, et al. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7:539. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Waterhouse AM, Procter JB, Martin DMA, Clamp M, Barton GJ. Jalview Version 2--a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(9):1189–1191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 2):213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baker NA, Sept D, Joseph S, Holst MJ, McCammon JA. Electrostatics of nanosystems: Application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(18):10037–10041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181342398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]