Significance

The present study reveals that macrophage phagocytosis toward healthy self-cells is controlled by a two-tier mechanism: a forefront activation mechanism requiring the inflammatory cytokine-stimulated protein kinase C (PKC)-spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) pathway, to which IL-10 conversely regulates, and the subsequent self-target discrimination mechanism controlled by the CD47-signal regulatory protein α (SIRPα)–mediated inhibition. The findings significantly expand our understanding of macrophage phagocytic plasticity and behavior under different conditions and also provide insights into strategies for enhancing transplantation tolerance and macrophage-based cancer eradication, especially for cancers toward which therapeutic antibodies are yet unavailable.

Keywords: phagocytosis, macrophage, CD47, SIRPα, cytokine

Abstract

Rapid clearance of adoptively transferred Cd47-null (Cd47−/−) cells in congeneic WT mice suggests a critical self-recognition mechanism, in which CD47 is the ubiquitous marker of self, and its interaction with macrophage signal regulatory protein α (SIRPα) triggers inhibitory signaling through SIRPα cytoplasmic immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motifs and tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1/2. However, instead of displaying self-destruction phenotypes, Cd47−/− mice manifest no, or only mild, macrophage phagocytosis toward self-cells except under the nonobese diabetic background. Studying our recently established Sirpα-KO (Sirpα−/−) mice, as well as Cd47−/− mice, we reveal additional activation and inhibitory mechanisms besides the CD47-SIRPα axis dominantly controlling macrophage behavior. Sirpα−/− mice and Cd47−/− mice, although being normally healthy, develop severe anemia and splenomegaly under chronic colitis, peritonitis, cytokine treatments, and CFA-/LPS-induced inflammation, owing to splenic macrophages phagocytizing self-red blood cells. Ex vivo phagocytosis assays confirmed general inactivity of macrophages from Sirpα−/− or Cd47−/− mice toward healthy self-cells, whereas they aggressively attack toward bacteria, zymosan, apoptotic, and immune complex-bound cells; however, treating these macrophages with IL-17, LPS, IL-6, IL-1β, and TNFα, but not IFNγ, dramatically initiates potent phagocytosis toward self-cells, for which only the Cd47-Sirpα interaction restrains. Even for macrophages from WT mice, phagocytosis toward Cd47−/− cells does not occur without phagocytic activation. Mechanistic studies suggest a PKC-Syk–mediated signaling pathway, to which IL-10 conversely inhibits, is required for activating macrophage self-targeting, followed by phagocytosis independent of calreticulin. Moreover, we identified spleen red pulp to be one specific tissue that provides stimuli constantly activating macrophage phagocytosis albeit lacking in Cd47−/− or Sirpα−/− mice.

To maintain tissue integrity and homeostasis, tissue macrophages and other immunological phagocytes must be prevented from phagocytizing healthy self-cells. One essential mechanism that prevents macrophages from doing so is CD47-signal regulatory protein α (SIRPα) interaction-mediated inhibition (1–4). In this mechanism, CD47, a broadly expressed cell surface protein that acts as a marker of self, along with SIRPα, the counter receptor of CD47 expressed on macrophages and other phagocytic leukocytes, serve as an inhibitory signaling regulator (5–7). On CD47 extracellular ligation, SIRPα increases tyrosine phosphorylation in the cytoplasmic domain immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motifs (ITIMs), leading to activation of the SH2-containing tyrosine phosphatase (SHP-1/2), which then mediates inhibitory signaling events through protein dephosphorylation. The end result of this CD47-SIRPα-SHP signaling is inhibition of phagocytosis toward self-cells (8).

The CD47-SIRPα mechanism was first reported by Oldenborg et al. (1), who had demonstrated in red blood cell (RBC) transfusion experiments that WT mice rapidly eliminate syngeneic Cd47-null (Cd47−) RBCs through erythrophagocytosis in the spleen and that the lack of tyrosine phosphorylation in SIRPα ITIMs was associated with this macrophage aggressiveness. Later, adoptive transfer/allograft experiments by others further demonstrated phagocytic clearance of platelets, lymphocytes, hematopoietic cells, and splenocytes in the absence of CD47-SIRPα–mediated inhibition (9–11). In all of these cases, the phagocytosis occurred swiftly and completely eliminated donor cells in less than 24 h, without facilitation by antibodies or immune complexes. Inclination that this phagocytosis differed from that which is mediated by antibodies or complements was supported by using Rag-1−/− mice and C3−/− mice, in which lack of lymphocytes or complements had not hindered elimination of Cd47− RBCs (1, 10). In line with the role of the CD47-SIRPα interaction in inhibiting macrophage phagocytosis, cancer studies found that tumor cells are commonly associated with increases in CD47 expression as a way to evade immunological eradication (12–15), whereas perturbation of CD47-SIRPα interaction provides opportunities for cancer eradication, especially in conjunction with therapeutic anticancer antibodies (4, 9, 16–21). Conversely, the lack of a compatible CD47 to ligate the recipient SIRPα is considered to be associated with tissue rejection in xenotransplantation (22–25).

Although these studies are exciting, major obstacles still remain and hinder further understandings of the CD47-SIRPα mechanism, as well as how to control macrophage behavior in disease therapies. Resolution of at least two puzzles remains paramount: first, why macrophages do not attack self in mice deficient of Cd47 or Sirpα? Despite that the Cd47-Sirpα–mediated inhibition is missing, mice deficient of Cd47 (26), Sirpα (established in this study), or the Sirpα cytoplasmic domain (27) are relatively healthy, manifesting no or only minor phenotypes (9, 18, 28) that suggest macrophage phagocytosis toward self-cells. Adoptive transfer of Cd47-null RBCs into these mutant mice also failed to induce rapid elimination (1) (also shown in this study). A case of Cd47 deficiency-associated lethal anemia in nonobese diabetic (NOD) mice had been reported, but this is associated with autoimmunity and increased antibody binding to RBC-mediated elimination (20). Having worked with WT and Cd47−/− hematopoietic chimera, Wang et al. (11) suggested that Cd47 expression on nonhematopoietic cells is required for macrophages to develop self-discrimination and that the lack of Cd47 expression in Cd47−/− mice confers macrophage tolerance. However, as the study had shown that this “trained” tolerance is not applied to Cd47− RBCs (11), it thus has not explained why mice deficient of Cd47 or Sirpα display incapability to clear endogenous or transferred RBCs. Hence, is there another mechanism(s) besides CD47-SIRPα that controls macrophage phagocytosis toward self? Second, the CD47-SIRPα mechanism serves as a “safety valve” against undesirable phagocytosis only when macrophages are initiated to phagocytose toward healthy self-cells. Unlike macrophage phagocytosis toward other targets, such as microbial pathogens, immune complex-labeled targets, or apoptotic cells, on which specific “eat-me” signals are displayed and induce phagocytosis (29–31), healthy self-cells usually do not attract macrophage attacking. The CD47-SIRPα mechanism alone, however, provides no explanation for how and when macrophages are triggered to attack healthy self-cells, nor does it describe how this phagocytic process is carried out. Thus, the core question remains: what is the mechanism that initiates macrophages to phagocytose healthy self-cells?

In this study, we established a strain of Sirpα KO (Sirpα−/−) mice. Further characterization of macrophage phagocytosis in Sirpα−/− and Cd47−/− mice found that, although these mutant mice generally display no defects, acute anemia associated with potent macrophage phagocytosis toward self-RBCs exhibits under inflammatory conditions or can be induced by treatment with inflammatory factors. Additional ex vivo and in vivo studies collectively suggest that macrophage phagocytosis toward self is dynamically controlled by concomitant, yet critical, mechanisms that determine macrophage phagocytic activation; it is governed by proinflammatory and antiinflammatory tissue environments while coupled with subsequent target selection via CD47-SIRPα–mediated inhibition.

Results

Acute Anemia in Mice Deficient of Cd47-Sirpα–Mediated Inhibition Under Inflammatory Conditions.

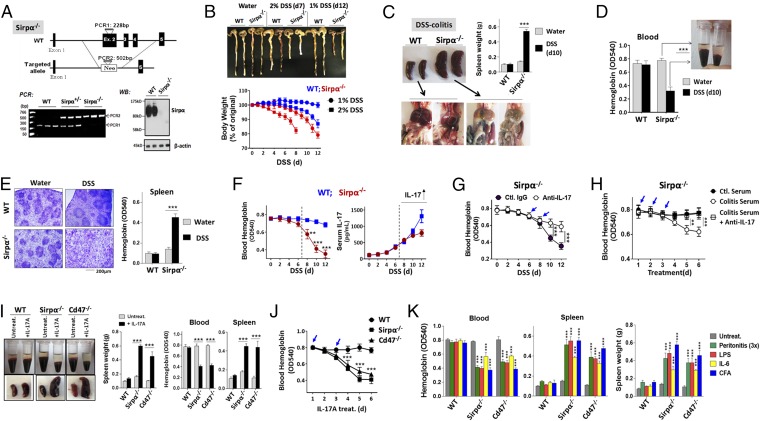

A strain of Sirpα KO (Sirpα−/−) mice was established by targeted inactivation of the Sirpα gene in embryonic cells (Fig. 1A). PCR genotyping and immunoblot [Western blot (WB)] confirmed disruption of the Sirpα gene and depletion of Sirpα protein expression. Similar to Cd47−/− mice, Sirpα−/− mice appeared healthy under the standard specific pathogen-free (SPF) housing conditions, having displayed no tissue/organ damage suggestive of enhanced macrophage phagocytosis toward self.

Fig. 1.

Inflammatory conditions induce acute anemia in mice deficient of the Cd47-Sirpα–mediated inhibition. (A) Generation of Sirpα KO mice. PCR genotyping shows that WT allele produces a DNA fragment of 228 bp, whereas mutated allele produces a fragment of 502 bp. Western blot (WB) confirmed depletion of Sirpα (∼120 kDa) protein in bone marrow leukocytes from Sirpα−/− mice. (B) Inducing colitis in mice by 1% or 2% DSS. Note that the colitic progression in Sirpα−/− mice induced by 1% DSS was comparable to that in WT induced with 2% DSS. (C and D) Acute anemia and splenomegaly developed in Sirpα−/− mice with colitis. WT mice and Sirpα−/− mice treated with DSS (2% DSS for WT and 1% DSS for Sirpα−/−) for 10 d were analyzed for peritoneal cavities (C) and peripheral blood (D). (E) H&E staining of spleens from WT and Sirpα−/− mice treated with 2% and 1% DSS for 10 d. (F) Time-course anemia development in Sirpα−/− mice during DSS-induced colitis and the correlation with IL-17 in serum. (G) IL-17 neutralization ameliorates anemia and splenomegaly in Sirpα−/− mice under colitis. An anti–IL-17 antibody (10 µg, i.v.) was given on days 6 and 8 (arrows) during DSS-induced colitis. (H) IL-17–containing colitic serum induces acute anemia in Sirpα−/− mice. Serum samples collected from healthy (ctl.) and colitic WT mice (2% DSS, 10 d) were administrated to healthy Sirpα−/− mice (i.v., 3×, arrows) with or without anti–IL-17 Ab. (I and J) IL-17A directly induces acute anemia and splenomegaly in Sirpα−/− mice and Cd47−/− mice. Healthy mice were given recombinant IL-17A (10 µg/kg, i.v.) on days 1 and 3 (arrows, J); anemia and splenomegaly were analyzed on day 5 (I) or in a time course manner (J). (K) Acute anemia and splenomegaly in Sirpα−/− and Cd47−/− mice under zymosan-peritonitis (3×, every other day), IL-6 administration (2×, 10 µg/kg, i.v.), LPS (0.25 mg/kg, i.p.), and CFA (1×, s.c.) administrations. Error bars are ±SEM **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. control or the beginning time point. Data presented in each panel represent at least three independent experiments with n ≥ 4, if applicable.

However, when inducing colitis with low-dose dextran sodium sulfate (DSS, 1–2%), Sirpα−/− mice displayed not only severe colitis but also acute anemia; the latter was associated with enhanced macrophage erythrophagocytosis in the spleen. As shown in Fig. 1B (SI Appendix, Fig. S1), compared with WT littermates, Sirpα−/− mice developed more severe colitis, demonstrating faster body weight loss, worse diarrhea/clinical scores, and enhanced polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN) infiltration into intestines under DSS treatment. Given that Sirpα-mediated inhibitory signaling negatively regulates leukocyte inflammatory response, it was not surprising that Sirpα deficiency exacerbates DSS-induced colitis. Similar results have been observed in our previous study using mice with truncated Sirpα cytoplasmic domain (32). Strikingly, colitic Sirpα−/− mice, but not WT mice, had also developed significant splenomegaly and acute anemia (Fig. 1C). Pale-colored abdominal cavities were seen in colitic Sirpα−/− mice (Fig. 1C), which were confirmed as anemia by peripheral hemoglobin reduction (40–50%; Fig. 1D). Dissection of their enlarged spleens revealed an extensive expansion of red pulp, to a point that had disrupted the white pulp structure. Spleen hemoglobin assays confirmed splenomegaly associated with increased RBC trapping, suggestive of aggressive erythrophagocytosis by red pulp macrophages (Fig. 1E). Together, these results suggest that active colitis induces macrophage-mediated RBC destruction in Sirpα−/− mice.

Further analyses revealed that the anemia developed in colitic Sirpα−/− mice was associated with IL-17. As shown in Fig. 1F, the anemia progressed slowly at the initial phase during colitis but was abruptly aggravated after days 7–8 when IL-17 started to arise in the serum. As demonstrated by us previously, IL-17 is highly induced at the postacute/chronic phase of DSS-induced colitis (33, 34). To test whether IL-17 played a role, we performed three experiments. First, Sirpα−/− mice under DSS-induced colitis were given an anti–IL-17 neutralization antibody. As shown in Fig. 1G, giving anti–IL-17 antibody on day 6 and 8 when IL-17 arises during DSS-induced colitis largely ameliorated anemia and splenomegaly in Sirpα−/− mice. Second, healthy Sirpα−/− mice were administrated with colitis serum samples that contained high levels of IL-17. As shown in Fig. 1H, injections of colitis serum into Sirpα−/− mice directly induced acute anemia. The effect was confirmed to be specific as control serum from healthy mice or colitis serum mixed with anti–IL-17 antibody failed to cause anemia. Third, a recombinant IL-17A was administrated into healthy Sirpα−/− mice. As shown in Fig. 1, I and J, injections of IL-17A alone (2×, 10 μg/kg, i.v.) directly induced acute anemia and splenomegaly in Sirpα−/− mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Notably, IL-17 injection also induced acute anemia and splenomegaly in Cd47−/− mice. As reported previously, Cd47−/− mice are resistant to low-dose DSS-induced colitis and are defective for IL-17 induction in vivo (34, 35). This explains why low-dose DSS treatment does not induce anemia in Cd47−/− mice, as anemia is secondary to the colitic condition and colitis-induced IL-17 (SI Appendix, Fig. S3).

In addition to colitis, other inflammatory conditions and cytokines, such as zymosan-induced peritonitis, LPS, and Freund’s complete adjuvant (CFA)-induced inflammation, also induced anemia and splenomegaly in mice lacking Sirpα or Cd47. As shown in Fig. 1K, repetitively inducing peritonitis by zymosan (3×, every other day) led to severe anemia and splenomegaly in Sirpα−/− and Cd47−/− mice, albeit this condition, per se, is short termed and self-resolving. Administration of IL-6 (2×, 10 μg/kg, i.v.), the signature cytokine associated with zymosan-induced peritonitis, also induced the same result. Injection of low-dose LPS (0.25 mg/kg, i.p.), or CFA (s.c.), in Sirpα−/− and Cd47−/− mice induced anemia and splenomegaly as well.

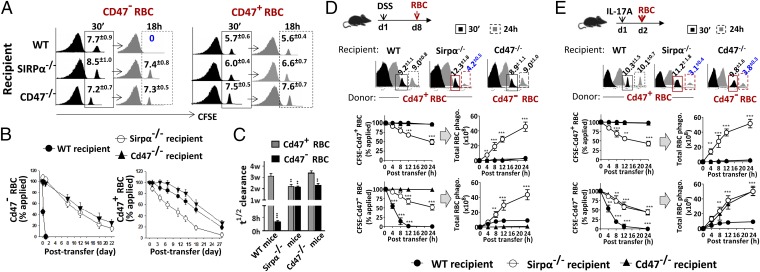

In Vivo Assessment of Macrophage Phagocytosis by Adoptive Transfer.

RBC adoptive transfer experiments were performed to further assess macrophage phagocytosis in vivo. Cd47+ or Cd47− RBCs isolated from WT or Cd47−/− mice, respectively, were labeled with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE), followed by transfer into different recipient mice and assessment of their clearance. As shown in Fig. 2 A–C, WT recipients swiftly cleared Cd47− RBCs in a few hours (t1/2 < 5 h), but retained Cd47+ RBC for over a month (t1/2 ∼ 3 wk), a time length matching the normal life span of RBCs in the circulation. This result is consistent with a previous report (1), suggesting the absence of CD47-SIRPα–mediated inhibition is associated with erythrophagocytosis in the spleen. However, this manner of rapid clearance did not occur in Sirpα−/− or Cd47−/− mice, which retained both Cd47+ RBCs and Cd47− RBCs for extended time periods. Adoptive transfer of splenocytes produced the same results; the only rapid clearance found was in WT recipients to which Cd47− splenocytes were transferred (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Thus, different from WT mice, Sirpα−/− and Cd47−/− mice do not eliminate RBCs because of merely missing the CD47-SIRPα–mediated inhibition.

Fig. 2.

Macrophage phagocytosis in vivo assessed by adoptive transfer experiments. (A–C) Clearance of adoptively transferred Cd47+ or Cd47− RBC in recipient mice. (A) FACS analyses of CFSE-RBCs in peripheral blood at 30 min (initial time point) and 18 h after transfer. (B) Time course clearance of CFSE-labeled RBCs. (C) The half-time (t1/2) of RBC clearance. Error bars are ±SEM. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. WT mice clearance of Cd47+ RBCs. (D) RBC clearance in mice under DSS-induced colitis. Mice treated with DSS (1% for Sirpα−/− mice, 2% for WT and Cd47−/− mice) for 8 d (d8) were transferred with CFSE-RBCs followed by determination of RBC clearance after 24 h. FACS data of Cd47+ RBCs and Cd47− RBCs in different mice at 30 min and 24 h after transfer were selectively shown. Total RBC phagocytosis was calculated based on the rates of CFSE-RBC clearance and the fact that Sirpα−/− mice eliminate both Cd47− RBC and Cd47+ RBC, whereas WT mice and Cd47−/− mice eliminate only Cd47− RBCs. (E) RBC clearance in mice treated with IL-17A. Mice treated once with IL-17A (10 µg/kg, i.v.) were transferred with CFSE-labeled Cd47+ or Cd47− RBCs a day later. Error bars are ±SEM. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. control or the initial time point. Data presented in each panel represent at least three independent experiments with n ≥ 4, if applicable.

However, treating Sirpα−/− and Cd47−/− mice with IL-17, or inducing inflammatory conditions in these mice, instantly induced accelerated RBC clearance. As shown in Fig. 2, D and E, Sirpα−/− mice with 1% DSS for 8 d (when IL-17 started to arise) or who were directly injected with IL-17A displayed rapid clearance of transferred Cd47+ and Cd47− RBCs (∼50%, 24 h). That Sirpα−/− mice cleared both Cd47+ and Cd47− RBCs was predictable, as macrophages in these mice experience no inhibition by the Cd47-Sirpα mechanism. Following this line, the RBC clearance in Sirpα−/− mice under DSS or IL-17A treatment was indeed much more extensive than the clearance of CFSE-labeled RBCs had shown, as Sirpα−/− macrophages in these mice would phagocytose not only the transferred RBCs but also endogenous RBCs concomitantly. Based on the CFSE-RBC clearance rate, the estimated total RBCs phagocytosed in DSS/IL-17A–treated Sirpα−/− mice should be more than 5 × 109 in 24 h (nearly 50% of peripheral RBCs without considering increased erythrogenesis; Fig. 2 D and E). Comparably, WT mice cleared only the transferred Cd47− RBCs (∼1 × 109). Accelerated RBC clearance was also observed in Cd47−/− mice under IL-17A treatment, and only toward Cd47− RBCs. As expected, no enhanced clearance was observed in Cd47−/− mice treated by DSS, as DSS induced no colitis or IL-17. Interestingly, we observed that macrophage phagocytosis can reach a plateau. As shown, mutant mice treated with one dose of IL-17A for 1 d rapidly cleared the transferred RBCs (Fig. 2E), whereas the same mice treated with IL-17A for multiple times and a longer period (d1 and d3) displayed only weak clearance of transferred RBCs (<5%, 24 h; SI Appendix, Fig. S5). As the latter recipient mice had already developed acute anemia and splenomegaly by the time RBC transfer was performed, the result suggests a capacity saturation of macrophages as per observations also stated by others (28).

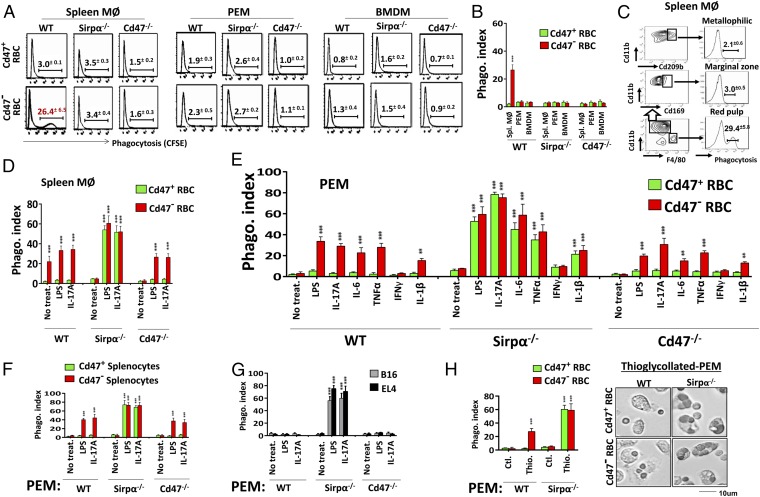

Ex Vivo Studies of Macrophage Phagocytosis.

To understand the functional differences of macrophages in Sirpα−/− or Cd47−/− mice vs. in WT mice, and how macrophages in Sirpα−/− or Cd47−/− mice changed their phagocytic characteristics and became erythrophagocytic under inflammatory conditions, we examined macrophage phagocytosis ex vivo. Three different tissue macrophages including splenic macrophages, peritoneal macrophages (PEMs), and bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) were tested. As shown in Fig. 3 A and B, consistent with in vivo studies, splenic macrophages freshly isolated from WT mice directly phagocytosed Cd47− RBCs, whereas those from Sirpα−/− or Cd47−/− mice displayed no phagocytosis. To our surprise, none of the PEMs or BMDMs from any mice displayed phagocytosis toward RBCs, irrespective of Cd47 expression. The fact that PEMs and BMDMs from WT mice failed to phagocytose even Cd47− RBCs was surprising, as splenic macrophages derived from the same mice had displayed direct phagocytosis. Further FACS analysis of WT splenic macrophages after Cd47− RBC phagocytosis revealed that the phagocytic macrophages were F4/80+ red pulp macrophages, whereas other macrophages, such as F4/80−Cd169+ metallophilic macrophages and F4/80−Cd209b+ marginal zone macrophages (1, 36, 37), displayed no phagocytosis (Fig. 3C). Testing macrophage phagocytosis toward splenocytes obtained the same results. In summary, among various macrophages tested in these experiments, only red pulp macrophages freshly isolated from WT mice were phagocytic toward self-cells, whereas other splenic macrophages, PEMs and BMDMs, and red pulp macrophages from mutant mice were all incapable of phagocytosis irrespective of the Cd47 expression on target cells.

Fig. 3.

Assaying macrophage phagocytosis ex vivo. (A and B) Macrophage phagocytosis toward RBCs. Freshly isolated splenic macrophages (MØ) and PEM and in vitro-derived BMDM were tested for phagocytosis toward CFSE-labeled Cd47+ or Cd47− RBCs. (C) Only red pulp macrophages are RBC phagocytes. (D) Activation of splenic MØ from Sirpα−/− and Cd47−/− mice for phagocytosis toward RBCs by LPS and IL-17A. (E) Activation of PEM for phagocytosis toward RBC by LPS, IL-6, IL-1β, IL-17, and TNFα, but not IFN-γ. (F and G) LPS and IL-17A–activated PEM phagocytosis toward splenocytes (F), B16, and EL4 (G). Error bars are ±SEM. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. no treatment controls. (H) Thioglycollate activates PEM phagocytosis toward RBCs. PEM lavaged without (ctl.) or with Brewer thioglycollate (3%, i.p.) elicitation was tested. Error bars are ±SEM. ***P < 0.001 vs. control PEM. Data presented in each panel represent at least three independent experiments with n ≥ 4, if applicable.

Meanwhile, testing the same macrophages for phagocytosis toward other targets that express the classical eat-me signals revealed that all macrophages, irrespective of their origins and phagocytic behavior toward self-cells, were potent phagocytes toward Escherichia coli, zymosan, apoptotic cells, antibody, or complement-bound targets (SI Appendix, Fig. S6).

Macrophage Phagocytic Plasticity.

Despite that most macrophages, with the exception of WT red pulp macrophages, had displayed incapability to directly phagocytize self-cells, treating these macrophages with LPS or IL-17 dramatically changed their phagocytic behavior. As shown in Fig. 3D, treating splenic macrophages from Sirpα−/− or Cd47−/− mice with LPS or IL-17A rapidly induced their phagocytosis toward RBCs. The same treatments also converted all PEMs and BMDMs, including those previously incapable of phagocytosis from WT and mutant mice, to potent phagocytes toward self (Fig. 3E and SI Appendix, Fig. S7). Strikingly, in all cases, whether phagocytosis occurred was governed by the presence of Cd47-Sirpα–mediated inhibition. As shown, the treated Sirpα+ macrophages, either from WT mice or Cd47−/− mice, phagocytosed only Cd47− RBCs, whereas Sirpα− macrophages from Sirpα−/− mice phagocytosed both Cd47+ RBCs and Cd47− RBCs indiscriminately. Further testing with additional cytokines found that IL-6, TNFα, and IL-1β, but not IFNγ, have the ability to induce macrophage phagocytosis toward self, providing a lack of the Cd47-Sirpα–mediated inhibition (Fig. 3E and SI Appendix, Fig. S7). Testing different cell types as the phagocytic targets found that macrophages activated by LPS or cytokines were also capable of phagocytizing murine splenocytes, B16 melanoma cells, and EL4 lymphoblasts in a Cd47-Sirpα–controllable manner (Fig. 3 F and G) and human RBCs and human HT29 colonic epithelial cells on which the expressed CD47 was incompatible for murine Sirpα (SI Appendix, Fig. S8). Moreover, we found that thioglycollate, a reagent commonly used to elicit macrophages in the peritoneum, activates PEM phagocytosis toward RBCs (Fig. 3H), explaining the seemingly discrepant results reported by others (28).

Converse to phagocytic activation, IL-10 strongly inhibits macrophage phagocytosis. As shown in Fig. 4A, IL-10 dose-dependently inhibited LPS-, IL-17–, IL-6–, TNFα-, and IL-1β–induced activation of PEM phagocytosis toward RBCs. Interestingly, WT red pulp macrophages also displayed remarkable phagocytic plasticity ex vivo. As shown in Fig. 4B, these macrophages, which directly phagocytized Cd47− RBCs immediately following isolation, completely lost this capacity after 2 d of culturing, but maintained phagocytosis toward E. coli, zymosan, apoptotic cells, and antibody- or complement-bound targets (Fig. 4C). To test whether these macrophages could be revived to target RBCs, we treated these macrophages with LPS and IL-17A, which dramatically rekindled the “culture-retarded” WT spleen macrophages for potent phagocytosis toward Cd47− RBCs. Again, this rejuvenated phagocytosis was subject to the control of the Cd47-Sirpα mechanism, as it completely avoided Cd47+ RBCs.

Fig. 4.

(A) IL-10 inhibits macrophage phagocytosis toward self. PEMs were treated with LPS and activating cytokines along with various concentrations of IL-10 before testing phagocytosis toward RBCs. (B) Phagocytic plasticity of WT red pulp macrophages. The phagocytic capacity toward Cd47− RBCs displayed by freshly isolated WT splenic macrophages was lost after 2 d (d2) of in vitro culturing. Treatments of cultured macrophages with LPS and IL-17A re-elicited their phagocytosis toward RBCs. (C) Phagocytosis toward Cd47− RBCs, E. coli, zymosan, apoptotic cells, and antibody or complement-bound hRBCs. Error bars are ±SEM. ***P < 0.001 vs. freshly isolated splenic macrophages. (D) Microscopic images of RBC phagocytosis by LPS- and IL-17A–treated splenic macrophages. (E) Sirpα ITIM phosphorylation and SHP-1 association under LPS and IL-17A treatments with or without Cd47 ligation. WT PEMs treated with LPS or IL-17A were further treated with Cd47+ RBCs or Cd47-AP (10 min, 37 °C) followed by cell lysis, Sirpα immunoprecipitation, and WB detection of Sirpα phosphorylation (SirpαpY) and SHP-1 association. Data presented in each panel represent at least three independent experiments with n ≥ 4, if applicable.

Moreover, the expression of Sirpα alone appears to convey inhibition in phagocytosis. As shown in Fig. 4D, as well as other figures, LPS/cytokine-treated Sirpα− macrophages consistently displayed much more potent phagocytosis toward self-cells than the same-treated WT macrophages. Real-time recording showed that the treated Sirpα− PEMs displayed an extraordinary capability to grab and uptake RBCs, resulting in rapid phagocytosis of multiple RBCs in a short time period during which the same-treated WT PEMs phagocytized only one to two RBCs (SI Appendix, Movies S1–S4). Analysis of Sirpα in WT macrophages after LPS or IL-17A treatment revealed a level of Sirpα ITIM phosphorylation and SHP-1 association even in the absence of extracellular CD47 ligation; however, cell surface ligation by Cd47+ RBCs led to further increased Sirpα ITIM phosphorylation and SHP-1 association (Fig. 4E). These results suggest that Sirpα expression alone conveys partial inhibition, whereas stronger inhibitory signaling triggered by Cd47 ligation is needed for effectively blocking macrophage phagocytosis toward self.

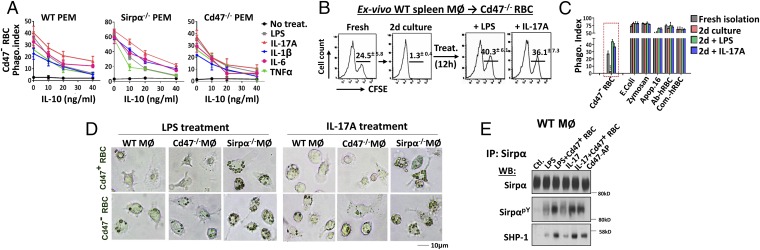

Signaling Mechanisms Regulating Macrophage Phagocytosis Toward Self.

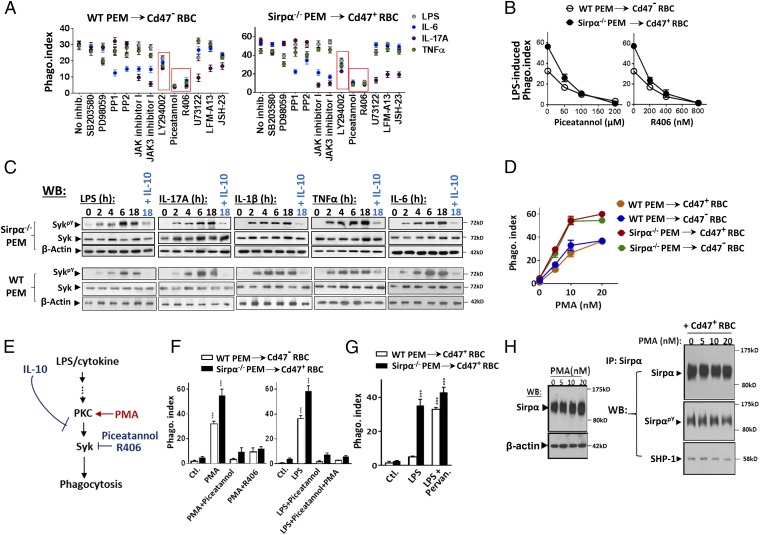

Multiple pharmacological inhibitors were tested for their effects on LPS and cytokine-induced activation of macrophage phagocytosis toward self. As shown in Fig. 5A, treating macrophages with inhibitors against MAP kinases, p38 (SB203580) and MEK (PD98059); Src family tyrosine kinases, PP1 and PP2; JAK 1 (JAK inhibitor I); JAK3 (JAK3 inhibitor I); phospholipase C (PLC) (U73122); Btk (LFM-13); or NF-κB (JSH-23) diminished phagocytic activation induced by certain, but not all stimuli. For example, inhibition of JAKs blocked IL-6 and IL-17, but not LPS and TNFα, for activation of PEM phagocytosis. These results were comprehensible; different stimuli trigger distinctive downstream molecules, especially at the proximal signaling region. In comparison, inhibition of PI3K by LY294002 and inhibition of Syk by Piceatannol or R406 inhibited phagocytic activation by all stimuli. As shown, LY294002 (20 μM) partially inhibited PEM phagocytic activation, whereas Syk inhibitors Piceatannol (100 μM) and R406 (400 nM) nearly completely eliminated PEM activation induced by all stimuli. Fig. 5B shows Piceatannol and R406 dose-dependently inhibited LPS-induced activation of PEM phagocytosis toward RBC. As shown in Fig. 5C, testing Syk kinase activity by the phosphorylation at Y519/520 (SykPY) in PEMs found increases in SykPY (thus Syk activity) after LPS/cytokine stimulation, supporting a key role of Syk in macrophage phagocytic activation. Conversely, IL-10, the phagocytic suppressive cytokine, counter-repressed Syk phosphorylation induced by activation factors. Although Syk was suggested to activate myosin-II (38), this appeared to not be the case in macrophage phagocytic activation; however, myosin-II was required for the later phagocytosis process in a way similar as in Fc-mediated phagocytosis (38, 39) (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). Depletion of calcium and magnesium or the presence of EDTA hindered macrophage phagocytic activation, possibly through affecting macrophage adhesion or the activation of the specific phagocytic receptor.

Fig. 5.

Role of Syk in phagocytic activation. (A) Testing cell signaling inhibitors on LPS/cytokine-induced macrophage phagocytic activation. PEMs were treated with LPS and cytokines in the presence of various inhibitors. After washing, inhibitor-free macrophages were tested for phagocytosis toward RBCs. (B) Syk inhibitors Piceatannol and R406 dose-dependently inhibited LPS-induced PEM phagocytic activation. (C) Syk activity is regulated by phagocytic stimuli and IL-10. PEMs treated with LPS and activating cytokines, or together with IL-10, were tested for total Syk and phosphorylated Syk (SykpY, specific at Y519/520). (D) PMA-induced macrophages phagocytosis toward RBCs. WT and Sirpα−/− PEMs were treated with PMA (37 °C, 30 min) before testing phagocytosis toward RBCs. (E) Depiction of PKC-Syk–mediated macrophage phagocytic activation toward self. (F) Syk is downstream of PKC. (Left) Inhibition of Syk by Piceatannol and R406 prevented PMA-induced phagocytic activation. (Right) PMA treatment failed to rescue LPS-mediated phagocytic activation-suppressed by Syk inhibition. Error bars are ±SEM. ***P < 0.001 vs. the respective controls. (G) Inhibition of SHP by pervanadate eliminates Cd47-dependent phagocytic recognition. LPS-treated WT PEMs were further briefly treated with pervanadate before testing for phagocytosis toward RBCs. Error bars are ±SEM. ***P < 0.001 vs. the respective controls. (H) PMA treatment does not affect Sirpα expression or Cd47 ligation-induced Sirpα phosphorylation and SHP-1 association. Data presented in each panel represent at least three independent experiments with n ≥ 4, if applicable.

Moreover, we found that phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), the PKC activator, dramatically activates macrophages for phagocytosis toward self. As shown in Fig. 5D, even at low nanomolar concentrations, PMA treatment instantly initiated PEM to phagocytose RBCs. In addition, PKC appears to be upstream of Syk in the phagocytic activation pathway (Fig. 5E). Inhibition of Syk by Piceatannol and R406 eliminated the PMA-induced PEM phagocytosis, whereas PMA treatment failed to rescue Syk inhibition-repressed PEM phagocytic activation by LPS (Fig. 5F). That PKC induces Syk activation in macrophages was consistent with previous reports (40–42). Interestingly, PMA-induced phagocytosis disregards the Cd47-Sirpα–mediated inhibition. As shown, PMA-treated WT PEMs aggressively phagocytosed both Cd47− and Cd47+ RBCs, a target indiscrimination similar to macrophages treated by pervanadate to abolish SHP signaling (Fig. 5G). Because PMA treatment neither reduced Sirpα expression nor affected Sirpα ITIM phosphorylation and SHP-1 association (Fig. 5H), this effect of PMA suggests an interference of the signaling pathway downstream of the Sirpα-ITIM-SHP axis.

What Is the Phagocytic Receptor on Macrophages for Uptaking Healthy Self-Cells?

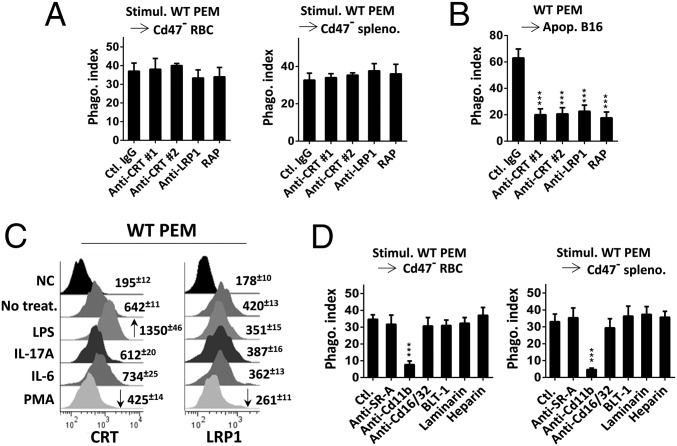

Given that calreticulin (CRT) interaction with LDL receptor-related protein (LRP1) has been suggested to mediate phagocytosis of apoptotic cells and viable cells (43–45), we examined these proteins. As shown in Fig. 6A, neither the inhibitory antibodies against CRT or LRP1 (46) nor LRP1 receptor-associated protein (RAP), which inhibits CRT-LRP1 binding (43, 47, 48), showed inhibition on LPS/cytokine–activated PEM phagocytosis toward RBCs and splenocytes. However, these same reagents significantly inhibited phagocytosis toward apoptotic cells (Fig. 6B) (more data are shown in SI Appendix, Figs. S10 and S11). Although a previous study (46) had suggested that increase of CRT on the macrophage surface is associated with phagocytosis toward tumor cells, assessment of CRT and LRP1 levels on PEMs found no convincing correlation of these protein expressions with PEM phagocytic activation. As shown in Fig. 6C, except for that LPS treatment induced an increase in CRT (consistent with ref. 46), none of the other phagocytic activation factors induced elevation of CRT or LRP1 on PEMs. Conversely, CRT and LRP1 expression on PEMs were even reduced (∼50%) after PMA treatment, which potently activates phagocytosis toward self. Protein coimmunoprecipitation also failed to detect alteration of CRT-LRP1 association, or LRP1 tyrosine phosphorylation, in PEMs after phagocytic activation, thus ruling out LRP1 to be a direct target downstream of Syk (SI Appendix, Fig. S12). Collectively, these results suggest that CRT and LRP1 are unlikely to be the receptor-ligand pair that is activated by phagocytic stimuli and mediates phagocytosis toward healthy self-cells.

Fig. 6.

(A) Blocking CRT or LRP1 failed to inhibit LPS/cytokine-induced PEM phagocytosis toward RBCs. LPS/cytokine-activated PEM phagocytosis toward RBCs was tested in the presence of anti-CRT antibody 1 (Abcam) and 2 (CST) (10 μg/mL each), anti-LRP1 (20 μg/mL), and the LRP1 receptor-associated protein (RAP; 20 μg/mL), all dialyzed free of sodium azide (note: sodium azide potently inhibits phagocytosis toward self-cells even at low concentrations). (B) CRT-LRP1 controls macrophage phagocytosis toward apoptotic cells. PEM (unstimulated) phagocytosis toward apoptotic B16 cells was tested in the presence of same antibodies and RAP as in A. Error bars are ±SEM. ***P < 0.001 vs. phagocytosis in the presence of control IgG. (C) Macrophage cell surface CRT or LRP1. PEMs, with or without (ctl.) treatment with LPS, IL-17A, IL-6, or PMA, were labeled for cell surface LRP1 and CRT followed by FACS. Increased and decreased expressions were marked by arrows. (D) Exploring other phagocytic receptors. Activated PEM phagocytosis toward RBCs was tested in the presence of antibodies against SR-A, Fc receptor Cd16/32 (10 μg/mL of each), inhibitors against SR-B (BLT1, 5 μM), dectin (laminarin, 100 μg/mL), complement (heparin, 40 U/mL), and antibody against Cd11b (10 μg/mL). Error bars are ±SEM. ***P < 0.001 vs. the respective control without inhibition. More data can be seen in SI Appendix, Figs. S10 and S11. Data presented in each panel represent at least three independent experiments with n ≥ 4, if applicable.

We also tested other known phagocytic receptors for their roles in activated macrophage phagocytosis toward self. As shown in Fig. 6D, antibody inhibition of scavenger receptor A (anti–SR-A) or Fc receptors (anti-Cd16/Cd32) (49), or inhibitors against scavenger receptor B (BLT1) (50), dectin (laminarin) (51), and complement (heparin) (52) mediated phagocytosis, failed to affect LPS-induced PEM phagocytosis toward RBCs. Interestingly, antibody against integrin Cd11b (Cd11b/Cd18) impeded phagocytosis. It is possible that anti-Cd11b antibody affected macrophage adhesion and membrane spreading, through which inhibited phagocytosis toward RBCs. The role of CD11b in phagocytosis of RBCs has also been reported for dendritic cells (53).

Different Spleen Environments in WT Mice and Mutant Mice.

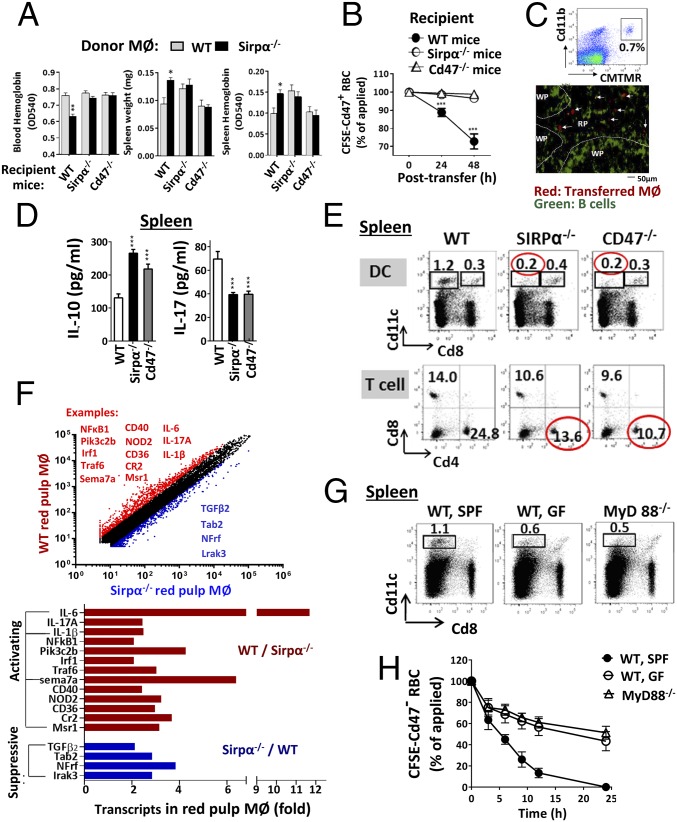

From our data, it is possible that all macrophages have the capability to phagocytize healthy self-cells; however, initiating the capacity is dependent on the presence of activating stimuli. The fact that red pulp macrophages in WT mice, but not Sirpα−/− or Cd47−/− mice, directly phagocytize Cd47− RBCs without requiring further activation suggests that the WT spleen provides constant stimulation supporting macrophage phagocytosis toward self, whereas the spleens in mutant mice do not. The observations that red pulp macrophages isolated from WT mice quickly diminished the phagocytic capacity, which was then rekindled by extrinsic stimuli, support this notion. In addition, adoptive transfer of nonphagocytic Sirpα− BMDMs into WT mice instantly induced RBC loss (10–30%, 48 h) and splenomegaly (Fig. 7A). Cotransfer with CSFE-labeled Cd47+ RBCs confirmed that Sirpα− macrophages mediated erythrophagocytosis in WT mice (Fig. 7B). Tissue analyses indicated that the adoptively transferred Sirpα− macrophages were distributed in red pulp of the WT spleen (Fig. 7C).

Fig. 7.

Sirpα−/− or Cd47−/− mice, but not WT mice, are deficient of macrophage stimulation in the spleen. (A–C) Monocytes/macrophages (2 × 107) derived from bone marrow cells of WT or Sirpα−/− mice were labeled with CMTMR and transferred into three strains of recipient mice. (A) Only Sirpα−/− macrophages in WT mice displayed phagocytosis toward RBCs, resulting in anemia and splenomegaly. Error bars are ±SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. control by transferring WT monocytes/macrophages into WT mice. (B) Cotransfer of CFSE-labeled Cd47+ RBCs along with Sirpα−/− monocyte/macrophages into WT mice confirmed rapid RBC clearance. Error bars are ±SEM. ***P < 0.001 vs. the initial time point. (C) Distribution of CMTMR-labeled Sirpα−/− macrophages in spleen red pulp (RP) but not white pulp (WP). (D) Higher levels of IL-10 and lesser IL-17 produced by spleen cells and in serum from Sirpα−/− and Cd47−/− mice. (E) Decreases in Cd11c+Cd8− DC and Cd4+ helper (Th) lymphocytes in the spleen of Sirpα−/− and Cd47−/− mice. (F) Transcription profiling of red pulp macrophages from WT and Sirpα−/− mice. F4/80+ red pulp macrophages were affinity isolated before mRNA isolation and profiling. The red-colored molecules (most being activating) are expressed at higher levels in WT than in Sirpα−/− red pulp macrophages, whereas the blue-colored molecules (most being suppressive) are expressed oppositely. (G) Reduction of Cd11c+Cd8− DCs in the spleens of MyD88−/− mice and germ-free (GF)–conditioned mice. (H) Attenuated clearance of Cd47− RBC in MyD88−/− mice and GF mice. Data presented in each panel represent at least three independent experiments with n ≥ 4, if applicable.

Further analyses of spleens cells found that those from Sirpα−/− and Cd47−/− mice produce relatively higher levels of IL-10, but lesser IL-17 and IL-6 compared with those from WT mice (Fig. 7D and SI Appendix, Fig. S13). Mutant mouse spleens were also associated with a deficit of Cd11c+ dendritic cells (DCs), especially the major migratory and antigen-presenting Cd8− DCs and Cd4+ Th lymphocytes [Fig. 7E and previous reports (54, 55)]. Other leukocytes, including natural killer (NK) cells, NKT cells, Cd8 T cells, B cells, and the total Cd11b+ myeloid cells demonstrated no reduction. Interestingly, red pulp macrophages are even increased in Sirpα−/− and Cd47−/− mice (SI Appendix, Table S1 and Fig. S14). Therefore, it is possible that the deficiency of Cd11c+Cd8− DCs and Cd4+ Th cells and the increase of IL-10 collectively cause inactivity of erythrophagocytosis in the spleens of Sirpα−/− and Cd47−/− mice. Transcription profiles revealed that red pulp macrophages in Sirpα−/− mice, compared with that in WT mice, express reduced levels of functional-stimulating molecules, such as IL-6, IL-17, IL-1β, NF-κB, and Cd40, but higher levels of suppressive molecules such as TGFβ (Fig. 7F) (more transcript data are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S15 and Tables S2 and S3). In another experiment, we examined mice that were housed under a germ-free (GF) condition and mice deficient of MyD88 (MyD88−/−), both being associated with a reduction of Cd11c+Cd8− DCs and Cd4+ Th cells in the spleen as well (Fig. 7G) (56–59). These mice manifested attenuated clearance of Cd47− RBCs in RBC adoptive transfer experiments (Fig. 7H).

Discussion

The present study reveals that multilayered mechanisms govern macrophage phagocytic behavior toward healthy self-cells. In addition to the previously identified CD47-SIRPα–mediated mechanism that prevents phagocytosis, there are additional mechanisms at the forefront level that determine macrophage propensity to either phagocytose toward, or be restrained from, the surrounding self-cells. Indeed, the CD47-SIRPα–mediated inhibition is relevant and indispensable only when the phagocytosis toward “self” is initiated in a tissue environment. Remarkably, multiple inflammatory conditions and proinflammatory cytokines/factors (e.g., LPS, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-17, and TNFα) are found to activate macrophages for phagocytosis toward healthy self-cells. Conversely, IL-10 suppresses this phagocytosis.

Different behavior of macrophages in WT mice vs. in Sirpα−/− or Cd47−/− mice has long been observed. As shown in our studies and also previously (1), WT mice rapidly eliminate Cd47− RBC through erythrophagocytosis, whereas Sirpα−/− or Cd47−/− mice cannot. We found that the lack of phagocytic stimulation is attributed to the latent macrophage behavior in mutant mice, as inflammatory stimulations that activate the PKC-Syk pathway instantly elicit phagocytosis. In particular, these mutant mice, although generally manifesting no macrophage-mediated destruction, have developed acute anemia under inflammatory conditions due to splenic macrophages directly phagocytizing self-RBCs. Ex vivo treatments of macrophages isolated from these mice with LPS or cytokines, or transfer of the nonphagocytic Sirpα−/− macrophages into WT mice, have instantly induced erythrophagocytosis. However, in these experiments, we failed to observe macrophages displaying tolerance or “split tolerance” suggested previously by others (11); instead, phagocytically activated macrophages derived from mice without Cd47 or Sirpα expression displayed the same, direct phagocytosis toward RBCs, splenocytes, and other cells as macrophages from WT mice, providing an absence of Cd47-Sirpα inhibition. Another similarity of macrophages from Sirpα−/−, or Cd47−/−, mice and WT mice is that they all need phagocytic activation to gain direct phagocytosis toward healthy self-cells. As shown by our data, not only macrophages from mutant mice but also PEM and BMDM from WT mice displayed phagocytic inactivity toward even Cd47-null RBCs in the absence of stimulation. WT red pulp macrophages, although displaying direct phagocytosis toward Cd47-null RBC in vivo, were unable to maintain this aggressiveness shortly after isolation. It is as if the “not attack-self” is a default mode for all macrophages, whereas “attack-self” represents an exceptional, hyper-phagocytic status for which special activating mechanisms are needed. This idea that macrophages are generally set to not attack self-cells is consistent with the fact that, in most nonlymphoid tissues, suppressive cytokines IL-10 and TGFβ tend to dominate (e.g., in peritoneum) and repress phagocytosis toward self. The spleen red pulp appears to be an exceptional tissue, constantly providing stimuli sustaining the phagocytic capacity toward self. Lack of such a stimulating environment in the spleen becomes a “compensation” mechanism that maintains Sirpα−/− or Cd47−/− mice to be healthy despite the absence of Cd47-Sirpα–mediated inhibition.

Although the CD47-SIRPα mechanism may be dispensable under normal conditions, it becomes extremely important under inflammatory conditions and infection, during which host macrophages would gain phagocytosis toward healthy self-cells (as suggested by this study). The finding that Sirpα−/− and Cd47−/− mice rapidly develop anemia under inflammatory challenges suggests that lack of these proteins may significantly reduce the threshold for anemia under inflammatory conditions. Inflammation-associated anemia (also called “anemia of inflammation” or “anemia of chronic disease”) is among the most frequent complications observed in hospitalized patients. Reported previously by us and others (60, 61), SIRPα expression in macrophages is decreased following LPS stimulation, suggesting a dynamic nature for the CD47-SIRPα–mediated inhibition especially on infection or activation of TLR. The expression of CD47 on cells can also be changed under different conditions (62–64). Also reported by us, alteration of clustering structures of SIRPα on macrophages or CD47 on tissue cells affects phagocytosis (65, 66). Moreover, data presented in this study show that CD47-SIRPα–mediated inhibition controls not only the phagocytic target selection, but also the phagocytic robustness once the target has been chosen. As shown in this study, SIRPα− macrophages, compared with SIRPα+ macrophages, are much more potent in phagocytosis toward self-cells once they have been activated by LPS or cytokines. Although both mutant strains are deficient of CD47-SIRPα inhibition, more severe anemia ensued in Sirpα−/− animals than in Cd47−/− mice after their splenic macrophages were stimulated. Even without stimulation, the macrophages in Sirpα−/− mice were faster to clear RBCs than those in WT or Cd47−/− mice. All these results suggest a SIRPα-ITIM–mediated inhibition on general cell processes of macrophage phagocytosis and are in concurrence with reports showing that the CD47-SIRPα pathway also tempers Fc- and complement-mediated phagocytosis (19–21), as well as phagocytosis toward apoptotic cells (65).

The detailed mechanism by which macrophages directly phagocytize healthy self-cells is unknown, despite that the mechanism that inhibits this phagocytosis via the CD47-SIRPα-SHP axis has been studied. Different from traditional phagocytosis aiming at alien pathogens, immune complexes, debris, and dying self-cells, on which certain eat-me or non-self signals ensue phagocytosis, phagocytosis toward healthy self-cells is uncustomary. To date, the molecules serving as the phagocytic ligands on healthy self-cells, together with the phagocytic receptor on macrophages, remain undefined. From the present study, it can be predicted that the specific phagocytic receptor on macrophages is either unexpressed or expressed but maintains inactivity until stimulation-induced activation occurs. The rapid elicitation of phagocytosis by PMA (<30 min) suggests the latter and that the PKC-Syk-mediated signaling pathway likely activates this phagocytic receptor through an “inside-out” mechanism. Along this line, it is possible that the CD47-SIRPα–mediated SHP activity inhibits this phagocytic receptor through protein dephosphorylation that counters the effect by Syk. The study has ruled out CRT-activated LRP1 and other known phagocytic receptors for mediating phagocytosis toward healthy self-cells. In particular, our data show that the CRT-LRP system controls phagocytosis toward apoptotic, but not healthy, self-cells. Interestingly, antibody inhibition of CD11b/CD18 impedes activated macrophage phagocytosis toward self; however, further studies are required to delineate if CD11b/CD18 acts as the specific phagocytic receptor or functions as an integrin essential for phagocytosis. Additional studies are also needed to define the mechanism that controls the receptor-mediated internalization of healthy self-cells after the phagocytic recognition.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

All experiments using animals and procedures of animal care and handling were carried out following protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Georgia State University. WT (C57BL/6J) and Cd47−/− (B6.129-CD47tm1Fpl/J) mice were from The Jackson Laboratory. Sirpα KO (Sirpα−/−) was established by replacing the exons 2–4 and their flanking regions with a neomycin resistant cassette in the Sirpα gene (collaboration with Chen Dong at the facility of University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston). All mice were housed in an SPF facility. DSS-induced colitis and zymosan-induced peritonitis were described previously (32–34). Mouse peripheral blood hemoglobin levels were determined by lysis of 10 μL whole blood in 1 mL water followed by OD reading at 540 nm.

Adoptive Transfer Experiments.

Cd47+ RBCs and Cd47− RBCs were freshly collected from WT and Cd47−/− mice, respectively. After labeling with CFSE, ∼109 RBCs in 150 µL PBS were transfused (i.v.) into recipient mice. Blood samples were collected 30 min after blood transfusion, and percentages of CFSE-labeled RBCs were determined by FACS. Blood samples were then collected at later time points to assess the CFSE-RBC clearance. For splenocyte-transfer experiments, splenocytes (2 × 107) labeled by CFSE were transferred into recipient mice followed by determination of clearance in peripheral blood and the spleen by FACS. For monocyte/macrophage-transfer experiments, bone marrow cells were cultured in M-CSF (10 ng/mL) for 3–4 d to produce monocytes/macrophages, which were then labeled with 5-(and-6)-(((4-chloromethyl)benzoyl)amino) tetramethylrhodamine (CMTMR) and transferred into recipient mice.

Macrophage Phagocytosis Assay.

Splenic macrophages were obtained from collagenase D- and DNase I-digested spleen tissues and were enriched by plating at 37 °C for 2 h. Resident PEMs were obtained by directly lavaging the peritoneum using sterile PBS. Thioglycollate-eliciteds PEM were prepared by i.p. injection of 1 mL 3% (wt/vol) Brewer thioglycollate, followed by lavage 4 d later. BMDMs were prepared by culturing freshly isolated bone marrow cells in the presence of M-CSF (10 ng/mL) for 5–6 d (66). To test phagocytosis ex vivo, freshly isolated/prepared macrophages in 24-well plates were incubated with CSFE-labeled RBCs or other cells for 30 min (37 °C) in the absence or presence of inhibitory antibodies or reagents. After washing, macrophage phagocytosis was analyzed microscopically or by FACS. To induce macrophage phagocytic activation, macrophages were treated with LPS (20 ng/mL), TNF-α (20 ng/mL), and IL-1β (10 ng/mL) for 6–10 h; IL-6 (10 ng/mL), IL-17A (10 ng/mL), and IFN-γ (100 U/mL) for 12–24 h; or PMA (5-20 nM) for 30 min (all at 37 °C) before phagocytosis assays. Phagocytic activation was also induced in the presence of pharmacological inhibitors or varied concentrations of IL-10 to test their inhibitory effects. Phagocytic indexes were expressed by the number of macrophages that ingested at least one target in 100 macrophages analyzed.

Transcript Microarray Profiling.

Red pulp microphages isolated by F4/80+ selection were used for mRNA isolation. Microarrays were performed using whole Mouse Genome Microarray 4X44K v2 (Agilent Technologies). Briefly, labeled cRNA was synthesized using the Quick Amp Labeling kit followed by hybridization using Agilent SureHyb. Slides were scanned by an Agilent DNA Microarray Scanner, and the images were analyzed using Feature Extraction software 11.0.0.1 with a background correction. Normalization was carried out using GeneSpring GX 12.1 software.

Statistical Analysis.

At least three independent experiments were performed for each set of data, which were presented as the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was assessed by Student t test for paired samples or one-way ANOVA for the group number (k) > 2.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Chen Dong (MD Anderson Cancer Center) for help in establishing the SIRPα KO mice, Dr. Jill Littrell for critical comments, and the Georgia State University Animal Resources Program for facilitating animal experiments. This work was supported, in part, by grants from National Institutes of Health (AI106839) and the American Cancer Society (to Y.L.), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2014M550284), and a fellowship from the American Heart Association (15POST22810008) (to Z.B.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The complete transcript profiling data of red pulp macrophages from Sirpα−/− mice and WT mice have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (accession no. GSE78191).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1521069113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Oldenborg PA, et al. Role of CD47 as a marker of self on red blood cells. Science. 2000;288(5473):2051–2054. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5473.2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matozaki T, Murata Y, Okazawa H, Ohnishi H. Functions and molecular mechanisms of the CD47-SIRPalpha signalling pathway. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19(2):72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barclay AN, Van den Berg TK. The interaction between signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPα) and CD47: Structure, function, and therapeutic target. Annu Rev Immunol. 2014;32:25–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chao MP, Weissman IL, Majeti R. The CD47-SIRPα pathway in cancer immune evasion and potential therapeutic implications. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24(2):225–232. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barclay AN. Signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPalpha)/CD47 interaction and function. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21(1):47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barclay AN, Brown MH. The SIRP family of receptors and immune regulation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6(6):457–464. doi: 10.1038/nri1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seiffert M, et al. Human signal-regulatory protein is expressed on normal, but not on subsets of leukemic myeloid cells and mediates cellular adhesion involving its counterreceptor CD47. Blood. 1999;94(11):3633–3643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kharitonenkov A, et al. A family of proteins that inhibit signalling through tyrosine kinase receptors. Nature. 1997;386(6621):181–186. doi: 10.1038/386181a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olsson M, Bruhns P, Frazier WA, Ravetch JV, Oldenborg PA. Platelet homeostasis is regulated by platelet expression of CD47 under normal conditions and in passive immune thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2005;105(9):3577–3582. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-2980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blazar BR, et al. CD47 (integrin-associated protein) engagement of dendritic cell and macrophage counterreceptors is required to prevent the clearance of donor lymphohematopoietic cells. J Exp Med. 2001;194(4):541–549. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.4.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang H, et al. Lack of CD47 on nonhematopoietic cells induces split macrophage tolerance to CD47null cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(34):13744–13749. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702881104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaiswal S, et al. CD47 is upregulated on circulating hematopoietic stem cells and leukemia cells to avoid phagocytosis. Cell. 2009;138(2):271–285. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Majeti R, et al. CD47 is an adverse prognostic factor and therapeutic antibody target on human acute myeloid leukemia stem cells. Cell. 2009;138(2):286–299. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willingham SB, et al. The CD47-signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPa) interaction is a therapeutic target for human solid tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(17):6662–6667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121623109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campbell IG, Freemont PS, Foulkes W, Trowsdale J. An ovarian tumor marker with homology to vaccinia virus contains an IgV-like region and multiple transmembrane domains. Cancer Res. 1992;52(19):5416–5420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chao MP, et al. Therapeutic antibody targeting of CD47 eliminates human acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Res. 2011;71(4):1374–1384. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao XW, et al. CD47-signal regulatory protein-α (SIRPα) interactions form a barrier for antibody-mediated tumor cell destruction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(45):18342–18347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106550108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishikawa-Sekigami T, et al. SHPS-1 promotes the survival of circulating erythrocytes through inhibition of phagocytosis by splenic macrophages. Blood. 2006;107(1):341–348. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okazawa H, et al. Negative regulation of phagocytosis in macrophages by the CD47-SHPS-1 system. J Immunol. 2005;174(4):2004–2011. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.4.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oldenborg P-A, Gresham HD, Chen Y, Izui S, Lindberg FP. Lethal autoimmune hemolytic anemia in CD47-deficient nonobese diabetic (NOD) mice. Blood. 2002;99(10):3500–3504. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.10.3500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oldenborg P-A, Gresham HD, Lindberg FP. CD47-signal regulatory protein α (SIRPalpha) regulates Fcgamma and complement receptor-mediated phagocytosis. J Exp Med. 2001;193(7):855–862. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.7.855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.del Rio ML, Seebach JD, Fernández-Renedo C, Rodriguez-Barbosa JI. ITIM-dependent negative signaling pathways for the control of cell-mediated xenogeneic immune responses. Xenotransplantation. 2013;20(6):397–406. doi: 10.1111/xen.12049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ide K, et al. Role for CD47-SIRPalpha signaling in xenograft rejection by macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(12):5062–5066. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609661104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maeda A, et al. The suppression of inflammatory macrophage-mediated cytotoxicity and proinflammatory cytokine production by transgenic expression of HLA-E. Transpl Immunol. 2013;29(1-4):76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang H, et al. Attenuation of phagocytosis of xenogeneic cells by manipulating CD47. Blood. 2007;109(2):836–842. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-019794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindberg FP, et al. Decreased resistance to bacterial infection and granulocyte defects in IAP-deficient mice. Science. 1996;274(5288):795–798. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tomizawa T, et al. Resistance to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and impaired T cell priming by dendritic cells in Src homology 2 domain-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase substrate-1 mutant mice. J Immunol. 2007;179(2):869–877. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamao T, et al. Negative regulation of platelet clearance and of the macrophage phagocytic response by the transmembrane glycoprotein SHPS-1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(42):39833–39839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203287200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ravichandran KS. Beginnings of a good apoptotic meal: The find-me and eat-me signaling pathways. Immunity. 2011;35(4):445–455. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akira S, Takeda K. Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4(7):499–511. doi: 10.1038/nri1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aderem A, Underhill DM. Mechanisms of phagocytosis in macrophages. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17(1):593–623. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zen K, et al. Inflammation-induced proteolytic processing of the SIRPα cytoplasmic ITIM in neutrophils propagates a proinflammatory state. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2436. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bian Z, Guo Y, Ha B, Zen K, Liu Y. Regulation of the inflammatory response: Enhancing neutrophil infiltration under chronic inflammatory conditions. J Immunol. 2012;188(2):844–853. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bian Z, et al. CD47 deficiency does not impede polymorphonuclear neutrophil transmigration but attenuates granulopoiesis at the postacute stage of colitis. J Immunol. 2013;190(1):411–417. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fortin G, et al. A role for CD47 in the development of experimental colitis mediated by SIRPalpha+CD103- dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2009;206(9):1995–2011. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davies LC, Jenkins SJ, Allen JE, Taylor PR. Tissue-resident macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2013;14(10):986–995. doi: 10.1038/ni.2705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gordon S, Plüddemann A, Martinez Estrada F. Macrophage heterogeneity in tissues: Phenotypic diversity and functions. Immunol Rev. 2014;262(1):36–55. doi: 10.1111/imr.12223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsai RK, Discher DE. Inhibition of “self” engulfment through deactivation of myosin-II at the phagocytic synapse between human cells. J Cell Biol. 2008;180(5):989–1003. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200708043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vicente-Manzanares M, Ma X, Adelstein RS, Horwitz AR. Non-muscle myosin II takes centre stage in cell adhesion and migration. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10(11):778–790. doi: 10.1038/nrm2786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu Y, et al. Protein kinase C θ is expressed in mast cells and is functionally involved in Fcepsilon receptor I signaling. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;69(5):831–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang M-Y, Huang D-Y, Ho F-M, Huang K-C, Lin W-W. PKC-dependent human monocyte adhesion requires AMPK and Syk activation. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e40999. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bijli KM, Fazal F, Minhajuddin M, Rahman A. Activation of Syk by protein kinase C-δ regulates thrombin-induced intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression in endothelial cells via tyrosine phosphorylation of RelA/p65. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(21):14674–14684. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802094200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gardai SJ, et al. Cell-surface calreticulin initiates clearance of viable or apoptotic cells through trans-activation of LRP on the phagocyte. Cell. 2005;123(2):321–334. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chao MP, et al. Calreticulin is the dominant pro-phagocytic signal on multiple human cancers and is counterbalanced by CD47. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2(63):63ra94. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nilsson A, Vesterlund L, Oldenborg PA. Macrophage expression of LRP1, a receptor for apoptotic cells and unopsonized erythrocytes, can be regulated by glucocorticoids. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;417(4):1304–1309. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.12.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Feng M, et al. Macrophages eat cancer cells using their own calreticulin as a guide: Roles of TLR and Btk. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(7):2145–2150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1424907112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Medh JD, et al. The 39-kDa receptor-associated protein modulates lipoprotein catabolism by binding to LDL receptors. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(2):536–540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.2.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Williams SE, Ashcom JD, Argraves WS, Strickland DK. A novel mechanism for controlling the activity of alpha 2-macroglobulin receptor/low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. Multiple regulatory sites for 39-kDa receptor-associated protein. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(13):9035–9040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mosser DM, Zhang X. 2011. Measuring opsonic phagocytosis via Fcγ receptors and complement receptors on macrophages. Curr Protoc Immunol Chap 14:Unit 14.27.

- 50.Nieland TJ, Penman M, Dori L, Krieger M, Kirchhausen T. Discovery of chemical inhibitors of the selective transfer of lipids mediated by the HDL receptor SR-BI. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(24):15422–15427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222421399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Herre J, et al. Dectin-1 uses novel mechanisms for yeast phagocytosis in macrophages. Blood. 2004;104(13):4038–4045. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lappegård KT, et al. Effect of complement inhibition and heparin coating on artificial surface-induced leukocyte and platelet activation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77(3):932–941. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(03)01519-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yi T, et al. Splenic Dendritic Cells Survey Red Blood Cells for Missing Self-CD47 to Trigger Adaptive Immune Responses. Immunity. 2015;43(4):764–775. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saito Y, et al. Regulation by SIRPα of dendritic cell homeostasis in lymphoid tissues. Blood. 2010;116(18):3517–3525. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-277244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Van VQ, et al. Expression of the self-marker CD47 on dendritic cells governs their trafficking to secondary lymphoid organs. EMBO J. 2006;25(23):5560–5568. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Walton KLW, He J, Kelsall BL, Sartor RB, Fisher NC. Dendritic cells in germ-free and specific pathogen-free mice have similar phenotypes and in vitro antigen presenting function. Immunol Lett. 2006;102(1):16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Silver KL, et al. MyD88-dependent autoimmune disease in Lyn-deficient mice. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37(10):2734–2743. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hammer GE, Ma A. Molecular control of steady-state dendritic cell maturation and immune homeostasis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2013;31(1):743–791. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-074929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sadanaga A, et al. Protection against autoimmune nephritis in MyD88-deficient MRL/lpr mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(5):1618–1628. doi: 10.1002/art.22571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhu D, et al. MicroRNA-17/20a/106a modulate macrophage inflammatory responses through targeting signal-regulatory protein α. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(2):426–36.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kong XN, et al. LPS-induced down-regulation of signal regulatory protein alpha contributes to innate immune activation in macrophages. J Exp Med. 2007;204(11):2719–2731. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lo J, et al. Nuclear factor kappa B-mediated CD47 up-regulation promotes sorafenib resistance and its blockade synergizes the effect of sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma in mice. Hepatology. 2015;62(2):534–545. doi: 10.1002/hep.27859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tang W, et al. Aberrant reduction of MiR-141 increased CD47/CUL3 in Hirschsprung’s disease. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2013;32(6):1655–1667. doi: 10.1159/000356601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang H, et al. HIF-1 regulates CD47 expression in breast cancer cells to promote evasion of phagocytosis and maintenance of cancer stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(45):E6215–E6223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1520032112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lv Z, et al. Loss of cell surface CD47 clustering formation and binding avidity to SIRPα facilitate apoptotic cell clearance by macrophages. J Immunol. 2015;195(2):661–671. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ha B, et al. ‘Clustering’ SIRPα into the plasma membrane lipid microdomains is required for activated monocytes and macrophages to mediate effective cell surface interactions with CD47. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e77615. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.