Abstract

Biochar is considered to be a promising material for heavy metal immobilization in soil. However, the immobilization mechanisms of Zn2+ on biochars derived from many common waste biomasses are not completely understood. Herein, biochars (denoted as PN350, PN550, WS350, and WS550) derived from pine needle (PN) and wheat straw (WS) were prepared at two pyrolysis temperatures (350 °C and 550 °C). The immobilization behaviors and mechanisms of Zn2+ on these biochars were systematically investigated. The results show that compared with biochars produced at low temperature, biochars produced at high temperature contained higher amounts of ash and exhibited much higher sorption capacities of Zn2+. By using Zn K-edge EXAFS spectroscopy, we find that the formation of various Zn precipitates/minerals, which was caused by the release of OH−, CO32−, and Si species from biochar, was the immobilization mechanism of Zn2+ on PN and WS biochars. Hydrozincite and Zn(OH)2 were the main species formed on PN350, PN550, and WS350; while on WS550, besides hydrozincite, a large fraction of hemimorphite was formed. The occurrence of hydrozincite and hemimorphite on biochar during Zn2+ immobilization is firstly reported in our study, which provides a new insight into the immobilization mechanism of Zn2+ on biochar.

Zinc (Zn) is an essential nutrient for living organisms1, however, an excess supply of Zn can lead to toxic effect on plants2,3,4 and microorganisms5,6 in soil. Due to anthropogenic activities (such as industrial activities, sludge application, waste water irrigation, etc.3), Zn can be easily released into soil environment7, which could pose a threat to the health of ecosystems8 and even to human beings9,10. As free Zn ions are the main species for Zn toxicity1,5, the immobilization of free Zn ions by some materials would reduce its bioavailability and toxicity in soil. Thus, materials which are effective in Zn immobilization should be developed.

As an emerging carbonaceous material, biochar has been extensively studied especially in the field of soil remediation11,12,13,14,15,16,17. The carbonaceous residue and entrained minerals (ash) are two main components of biochar18, they perform different functions in soil remediation. The carbonaceous residue can adsorb and retain water19 and some organic pollutants20,21,22,23; the ash can provide nutrient elements and improve soil pH24. In terms of heavy metal immobilization, both of the two components could be involved in the process. Plenty of studies have reported the immobilization behavior of Zn on biochars derived from different biomass (such as hardwood25,26, corn straw25, sugarcane straw27, dairy manure28, and meat and bonemeal29), and some of them have proposed the immobilization mechanisms which implied more important role of ash on biochar on Zn immobilization27,28,30. Xu et al. studied the sorption behavior of Zn on biochar derived from dairy manure, and found that large amounts of PO43− and CO32− were released from biochar and reacted with Zn2+ to form Zn phosphate and Zn carbonate28. With the help of P K-edge XANES spectroscopy, Wegner et al. found that hopeite (Zn3(PO4)·2H2O) or a similar Zn-P phase were formed, when biochar was used to immobilize Zn in the sewage field soils30. In addition to forming Zn precipitates, the formation of Zn complexes on biochar surface also led to Zn immobilization29. By using the method of extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectroscopy, Betts et al.29 found that Zn bound to phosphate groups in meat and bonemeal biochar in a monodentate inner-sphere surface complex.

Feedstock types and pyrolysis temperature are two main factors influencing biochar property18. As a wide variety of biomasses can be used for biochar production, previous studies on Zn2+ immobilization behavior of limited type of biochars are far from enough. To explore the immobilization mechanisms of Zn2+ on different biochars and provide more basic data for biochar application, studies which are focused on biochars produced by other waste biomasses need to be done. Although many studies have mentioned the effect of pyrolysis temperature on biochar property20,31,32,33,34, few studies systematically investigated the effect of pyrolysis temperature on immobilization behavior of Zn2+ on biochar and elucidated the internal connection between pyrolysis temperature, biochar property, and immobilization behavior of Zn2+ on biochar. In this study, biochars produced by pine needle (PN) and wheat straw (WS) were chosen for investigation, to our knowledge, there is no published work concentrated on Zn2+ immobilization behavior of biochars derived from these biomasses. Two temperatures were chosen for biochar preparation, and the Zn2+ immobilization behaviors of biochars produced by different temperature were compared through several sorption experiments (i.e. sorption kinetics, sorption isotherms, and the effect of pH). To reveal the importance of the ash on biochars on Zn immobilization, the ash was removed from biochars, and the Zn2+ immobilization behaviors of de-ashed biochars were compared with those of the raw biochars. To explore the immobilization mechanisms, the methods of Zn K-edge EXAFS spectroscopy and X-ray Powder Diffraction (XRD) were used for biochar characterization. Through this study, the Zn species immobilized by PN and WS biochars will be identified, the immobilization mechanisms and the relation between pyrolysis temperature and immobilization behaviors of Zn2+ on studied biochars will be clear.

Results and Discussion

Characterization of PN and WS biochars

The contents of the common elements (i.e. K, Ca, Mg, Al, Fe, Zn, and P) in biochars were determined and listed in Table 1. The contents of most studied elements in biochars produced at 550 °C were higher than those in biochars produced at 350 °C, which suggested that the ash contents of biochars produced at 550 °C were higher than those of biochars produced at 350 °C. The high Ca contents in PN biochars and high K contents in WS biochars implied that, in addition to immobilizing heavy metal, PN and WS biochars could also supply large amounts of nutrient elements to the soil. When raw biochars were washed by HCl/HF solution, the contents of the elements substantially dropped, this means that the factor of ash which may influence the sorption of Zn can be excluded in de-ashed biochars. The pHs of raw biochars and the pHPZC of de-ashed biochars were also listed in Table 1.

Table 1. The contents of some common elements (mg g−1), and the pH and pHPZC of biochars.

| Biochar | K | Ca | Mg | Al | Fe | Zn | P | pH and pHPZC* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PN350 | 9.8 ± 0.6 | 15.7 ± 0.3 | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.0 | 0.9 ± 0.0 | 0.076 ± 0.001 | 1.8 ± 0.0 | 7.9 ± 0.1 |

| PN550 | 13.6 ± 0.0 | 23.7 ± 0.7 | 4.6 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.0 | 1.3 ± 0.0 | 0.106 ± 0.003 | 2.7 ± 0.0 | 9.6 ± 0.0 |

| WS350 | 31.8 ± 0.4 | 9.7 ± 0.2 | 2.6 ± 0.0 | 1.8 ± 0.0 | 1.7 ± 0.0 | 0.061 ± 0.009 | 1.3 ± 0.0 | 8.2 ± 0.0 |

| WS550 | 38.8 ± 0.6 | 12.3 ± 0.7 | 3.8 ± 0.1 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.0 | 0.060 ± 0.001 | 1.7 ± 0.0 | 9.7 ± 0.0 |

| PN350D | 0.29 ± 0.02 | 5.0 ± 0.5 | 1.8 ± 0.0 | 0.46 ± 0.00 | 0.25 ± 0.01 | 0.056 ± 0.002 | 0.12 ± 0.00 | 4.3 ± 0.1 |

| PN550D | 0.24 ± 0.01 | 4.7 ± 0.1 | 4.0 ± 0.1 | 0.91 ± 0.02 | 0.28 ± 0.00 | 0.083 ± 0.003 | 1.20 ± 0.02 | 5.4 ± 0.1 |

| WS350D | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.0 | 0.13 ± 0.05 | 0.21 ± 0.01 | 0.016 ± 0.003 | 0.05 ± 0.00 | 4.4 ± 0.0 |

| WS550D | 0.06 ± 0.00 | 3.3 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.0 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.31 ± 0.01 | 0.029 ± 0.002 | 0.22 ± 0.00 | 5.5 ± 0.1 |

*The dissolution of the ash in raw biochar could consume a large amount of H+, which makes the pHPZC data of raw biochars unreliable, thus only the pHPZC of de-ashed biochars has been tested.

To characterize the functional groups on different biochars, FTIR and XPS analysis were conducted on these biochars. The results were shown in Supplementary Fig. S1 and Supplementary Fig. S2 and Table S1.

Sorption kinetics and isotherms and the effect of initial pH on sorption behavior of Zn2+ on biochars

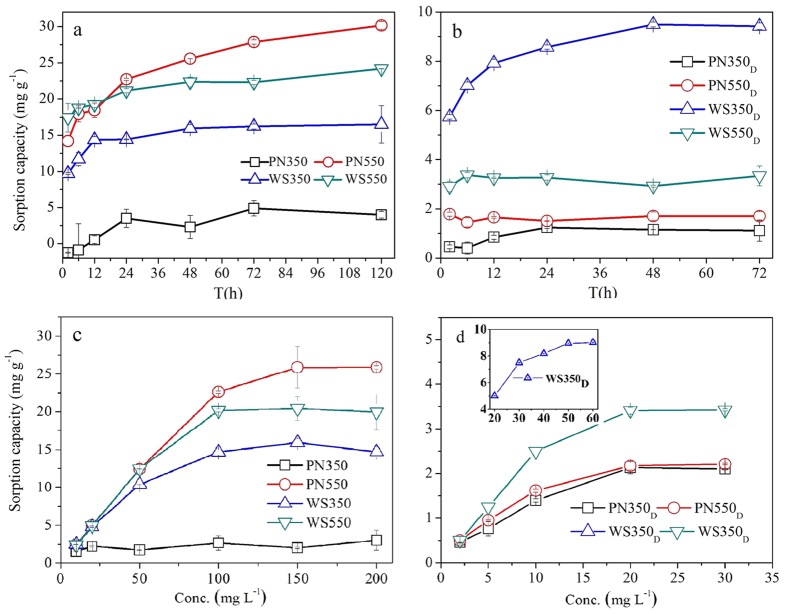

To study the sorption behaviors of Zn2+ on different biochars, a series of sorption experiments were conducted. Figure 1 shows the kinetics and isotherms of Zn2+ sorption on different biochars. From Fig. 1a we find that sorption reactions between Zn2+ and most biochars can reach equilibrium at 48 h, the sorption capacities of Zn2+ on biochars produced at 550 °C were higher than those of Zn2+ on biochars produced at 350 °C. Figure 1c shows that the maximum sorption capacities of Zn2+ on raw biochars decreased in the following order: PN550 (25.9 mg g−1) > WS550 (20.4 mg g−1) > WS350 (16.0 mg g−1) > PN350 (3.0 mg g−1). It seems that biochars with higher ash contents were more effective on Zn immobilization. From Fig. 1c,d we find that, the maximum sorption capacities of Zn2+ on de-ashed biochars were lower than those of Zn2+ on their corresponding raw biochars. Especially for biochars produced at 550 °C, the maximum sorption capacities of Zn2+ on biochars decreased by more than 80% when the ash was removed. These results suggested the important role of ash on Zn immobilization by biochar. Among de-ashed biochars, WS350D had the highest sorption capacity (9.4 mg g−1), which may be due to the more oxygen-containing functional groups WS350D had compared with other biochars. Kinetics experiments show that sorption reactions between Zn2+ and most biochars can reach equilibrium at 48 h, thus the equilibrium time for the following experiments was set to be 48 h. As PN550, WS350, and WS550 had considerable sorption capacities of Zn2+, several kinetics models (pseudo-first and pseudo-second-order models35, Elovich model36,37, and intraparticle diffusion model38,39) and isotherms models (Langmuir, Frendlich, and Langmuir-Frendlich models40) were performed on kinetics and isotherms data of these biochars, the fitting results were shown in Supplementary Tables S2 and S3.

Figure 1. Kinetics and isotherms of Zn2+ sorption on different biochars.

(a) Kinetics of Zn2+ sorption on raw biochars (the initial concentration of Zn was 150 mg L−1; the solution pHs were ranged from 6.5 to 7.5 (see Fig. S3) without adjustment; (b) kinetics of Zn2+ sorption on de-ashed biochars (the initial concentration of Zn was 50 mg L−1; the solution pHs were controlled to 7.0); (c) isotherms of Zn2+ sorption on raw biochars (the solution pHs were not adjusted); (d) isotherms of Zn2+ sorption on de-ashed biochars (the solution pHs were controlled to 7.0). Error bars represent ± SE (SE is the standard error of estimate). The experiments were conducted in duplicate (n = 2).

The effect of initial pH on sorption capacities of Zn2+ on biochars were shown in Supplementary Fig. S4. As can be seen from Fig. S4, the sorption capacities of PN550, WS350, and WS550 decreased gradually with the decrease of initial pH. Unlike the sorption behaviors of raw biochars, sharp decreases occurred on the sorption capacities of de-ashed biochars, when the initial pH decreased from 9 to 7. This may be caused by the absence of buffer effect of ash. The low sorption capacity of Zn2+ on PN350 under the whole pH range could be due to the low ash content.

XRD analysis

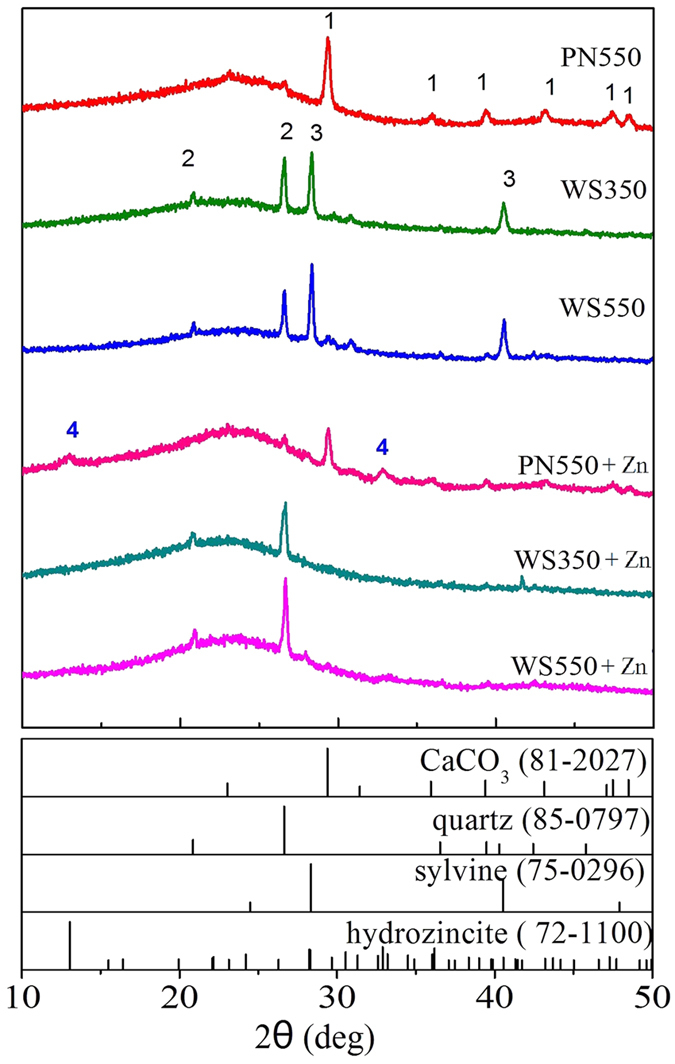

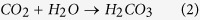

The sorption experiments showed that some Zn precipitates/minerals may be formed on biochar, thus XRD analysis were performed on these biochars. As PN350 had a relatively low sorption capacity of Zn2+, we just focused on other three biochars (PN550, WS350, and WS550) and biochars loaded with Zn (denoted as PN550 + Zn, WS350 + Zn, and WS550 + Zn). Figure 2 shows the XRD spectra of the samples. The main mineral in PN550 was CaCO3, the peaks of quartz in PN550 were not obvious. The peak intensities of CaCO3 and quartz show that there could be large amount of CO32− and low amount of Si contained in PN550. In WS350 and WS550, two minerals can be detected, they were quartz and sylvine. Compared with PN550, WS350 and WS550 contained larger amount of Si species.

Figure 2. The XRD spectra of raw biochars and biochars loaded with Zn2+.

(The species are 1. CaCO3 (81–2027), 2. quartz (SiO2, 85–0797), 3. sylvine (KCl, 75–0296), 4. hydrozincite (Zn5(CO3)2(OH)6, 72–1100)).

Compared with the spectra of PN550, two more peaks appeared in the spectra of PN550 + Zn, which may belong to hydrozincite. Thus the formation of hydrozincite could be one of the mechanisms for Zn immobilization on PN550. In WS350 + Zn and WS550 + Zn, as sylvine is soluble, only quartz was maintained on WS350 and WS550. Although WS350 and WS550 had considerable sorption capacities of Zn2+, none of the Zn species could be detected from the two samples by XRD analysis. This may be caused by the poor crystallinity of Zn species formed on WS350 and WS550. As the characterization way of XRD has the requirement on sample crystallinity, the method of XAFS was applied in Zn species identification.

EXAFS analysis

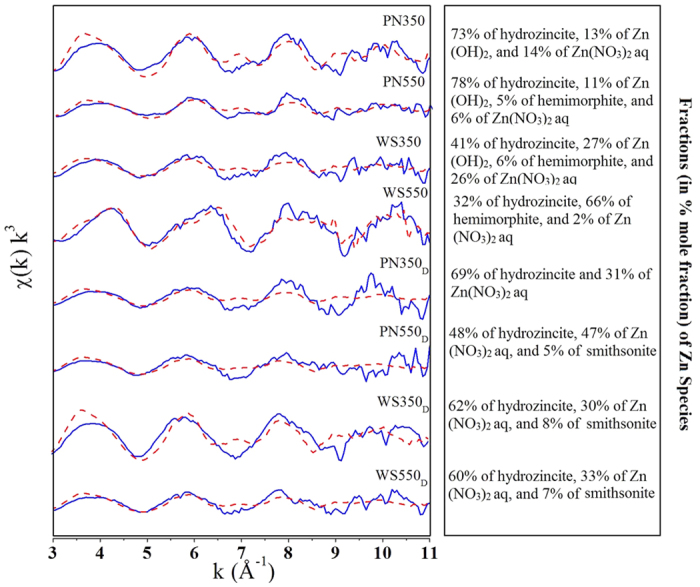

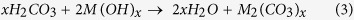

The k3-weighted χ(k) functions of raw biochars and de-ashed biochars are shown in Fig. 3. To obtain the types and fractions of Zn species on these biochars, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) accompanied with Target Transformation (TT) and Linear Combination Fitting (LCF) were performed on χ(k) k3-spectra ranging from 3–11 Å−1 for all the samples. PCA was used to determine the number of primary components which may be present in the spectra of biochars; TT was used to evaluate which species may be contained in these biochars; and LCF was applied to quantitatively analyze the Zn species on biochars. (The details on PCA, TT and LCF were shown in S1 in SI).

Figure 3. χ(k) k3-spectra of the Zn species on different biochars (solid line) and fractions of Zn species (in % mole fraction) determined by linear combination fitting.

Deshed line represents the fitted line.

The result of PCA shows that five principal components may be present in the spectra of biochars. After TT by using the χ(k) k3-spectra of a series of standard Zn compounds (Supplementary Fig. S5), we found six Zn species (i.e. Zn(NO3)2 aqueous (Zn(NO3)2 aq), Zn(OH)2, willemite (Zn2SiO4), smithsonite (ZnCO3), hemimorphite (Zn4(H2O)(Si2O7)(OH)2), and hydrozincite (Zn5(CO3)2(OH)6)) may be contained in these biochars. The number of Zn species obtained by TT was higher than that obtained by PCA, this is due to the similarity between the spectra of some standard species41,42,43. The PCA results suggested that the Zn precipitates/minerals could take up a large fraction of Zn species in biochar.

The LCF was subsequently performed on the samples using the Zn species selected by TT. The main components and their fractions in the samples were obtained and shown in Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table S6. From the fitting results (Fig. 3), we find that Zn precipitates/minerals (i.e. hydrozincite, Zn(OH)2, and hemimorphite) accounted for a large share of Zn species (>70%) in raw biochars, which indicated the indispensable role of ash in biochar on Zn immobilization. High proportions of hydrozincite (>40%) and Zn(OH)2 (>10%) were observed in most of the raw biochars. This result indicated that CO32− and OH− were two common ions for Zn immobilization. It is noteworthy that, unlike other raw biochars, WS550 contained large fraction of hemimorphite (66%). This was probably caused by the large amount of dissolved Si species released from WS550, which implied the crucial role of dissolved Si species in Zn immobilization. The species Zn(NO3)2 aq represents the Zn adsorbed on oxygen-containing functional groups (i.e. carboxyl and hydroxyl) on biochar. In PN350 and WS350, the fractions of Zn(NO3)2 aq were respectively 14% and 26%; while in PN550 and WS550, the two values dropped to 6% and 2%. These changes were due to the increase in ash contents and loss of oxygen-containing functional groups in biochars with pyrolysis temperature. In de-ashed biochars, only two main Zn species, hydrozincite and Zn(NO3)2 aq, existed in de-ashed biochars. Although hydrozincite is Zn mineral, the formation of small amounts of hydrozincite in de-ashed biochars may be caused by the dissolution of CO2 in the air. The pHPZC of de-ashed biochars were 4.3–5.5 (Table 1), thus when the solution pHs were controlled to 7, the de-ashed biochars could easily adsorb few amount of Zn2+.

The Ions Involved in Zn Immobilization

According to the analysis of XRD and EXAFS, we have identified the main Zn species formed on biochars. To examine these results, the pHs of the samples withdrawn at 2 h and the concentrations of CO32− and Si species in the samples withdrawn at 120 h in kinetics experiments were determined. For comparison, these determinations were also conducted on their corresponding blank samples (0.1 g of biochar + 25 mL of water). The concentrations of PO43−, Ca2+, and Mg2+ were also determined. The samples in kinetics experiments are denoted as B + Zn, and the blank samples are denoted as B.

As shown in Table 2, the pHs of B + Zn at the reaction time of 2 h reached 7.0, which were lower than those of B. This indicated that plenty of OH− were consumed during Zn immobilization. For PN350 and WS350, the concentrations of CO32− in B were respectively 0.3 and 1.1 mmol L−1; while the concentrations of CO32− in B + Zn could not be detected (ND) indicating the consumption of CO32− during Zn immobilization. As Ca2+ which released from biochars could also react with CO32−, the amount of CO32− which would react with Zn to form hydrozincite would be underestimated from these results. The released Si species could also influence the determination of CO32−, as they could buffer H+ in the solution44, which lead to the overestimated concentrations of CO32−. Thus the concentrations of CO32− in different samples cannot be used to calculate the real amounts of consumed CO32− in Zn immobilization, they were only for reference. For WS350 and WS550, the Si concentrations in B were respectively 0.9 and 2.0 mmol L−1 (the initial concentration of Zn2+ was 2.3 mmol L−1). Once reacted with Zn2+, the concentrations of Si decreased drastically. From the considerable amounts of released and consumed Si species, we assumed that some Si species in WS biochars may play an important role in Zn immobilization. Fig. S6 shows the ATR-FTIR spectra of the raw biochar filtrates. From Figs S6a and S6b we cannot see any band present in the spectra, while in Figs S6c and S6d there is a broad band in the region 1150–1050 cm−1 in each of the spectrum, which is due to the asymmetric Si–O–Si stretching vibration of long chain polymers45. The ATR-FTIR result suggested that the Si species released from biochar are Si-containing polymers with different chain length. The release and consumption of OH−, CO32− and Si species confirmed the results of XRD and EXAFS.

Table 2. pH and Concentrations of Species (mmol L−1) Involved in Zn Immobilization in the Samples.

| Biochars | pH* |

CO32− |

Si species |

PO43− |

Ca2+ |

Mg2+ |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | B + Zn | B | B + Zn | B | B + Zn | B | B + Zn | B | B + Zn | B | B + Zn | |

| PN350 | 8.3 ± 0.1 | 6.7 ± 0.1 | ND | ND | 0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.001 ± 0.000 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | ND | 0.08 ± 0.00 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.07 ± 0.00 | 0.05 ± 0.00 |

| PN550 | 10.0 ± 0.0 | 7.0 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.3 | ND | 0.05 ± 0.00 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.04 ± 0.00 | ND | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 1.4 ± 0.0 | 0.06 ± 0.00 | 0.09 ± 0.00 |

| WS350 | 9.5 ± 0.0 | 7.1 ± 0.0 | ND | ND | 0.89 ± 0.02 | 0.09 ± 0.00 | 0.06 ± 0.00 | ND | 0.08 ± 0.00 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.09 ± 0.00 | 0.18 ± 0.02 |

| WS550 | 10.4 ± 0.0 | 7.2 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.0 | ND | 1.95 ± 0.05 | 0.23 ± 0.00 | 0.06 ± 0.00 | ND | 0.11 ± 0.00 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.08 ± 0.00 | 0.17 ± 0.02 |

*As some ions released from biochar may consume released OH− in biochar + water mixture as reaction time increases, the pHs of B and B + Zn were determined at the reaction time of 2 h.

The difference on the concentrations of PO43− between B and B + Zn implied the formation of Zn3(PO4)2 on biochars, however the concentrations of PO43− in B were no more than 0.06 mmol L−1, thus the precipitation role of PO43− in the studied biochars can be ignored. The concentrations of Ca2+ and Mg2+ in B + Zn were much higher than those of Ca2+ in B; expect for the condition of PN350, the concentrations of Mg2+ in B + Zn were also higher than those of Mg2+ in B. This may be caused by the competition of Zn2+ for released OH−, CO32−, and some sorption sites. When raw biochar was added into water, plenty of ions such as Ca2+, Mg2+, OH−, and CO32− were released from biochar to bulk solution. With the gradual increase in concentrations of Ca2+, Mg2+, and anions such as OH−, CO32− in the solution close to biochar surface, some of these ions would be over-saturated, Ca, Mg-precipitates would form and deposit on the surface of biochar. In addition to forming precipitates, a portion of Ca2+ and Mg2+ could also be captured by oxygen-containing functional groups of biochar. Thus, in raw biochar-water systems, the newly released Ca2+ and Mg2+ can be immobilized rapidly. When Zn2+ was present in the solution, Zn2+ would diffuse to the area close to biochar surface, they could also react with the newly released anions (i.e. OH− and CO32−) and occupy the sorption sites (i.e. oxygen-containing functional groups of biochar). This process would decrease the concentrations of OH−, CO32−, and PO43− and sorption sites of Ca2+ and Mg2+, which further resulted in the increased amounts of released Ca2+ and Mg2+ in raw biochar-Zn solution systems (B + Zn). The low sorption capacity of Zn2+ on PN350 and inhomogeneous distribution of Mg on biochar may lead to the lower concentration of Mg2+ in B(PN350) + Zn, when compared with those of Mg2+ in B(PN350) + Zn.

The Possible Evolution Processes of OH−, CO3 2−, and Si Species on Biochars

To reveal the immobilization mechanism of Zn on biochars, we first need to know the formation rule of OH−, CO32−, and Si Species. Although few studies can describe the clear evolution processes of ash in biochar, we may obtain the general evolution processes based on the pyrolysis rule of biomass.

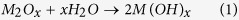

In plants, some alkali and alkaline earth metal (AAEM), e.g. K, Ca, and Mg, are associated with organic molecules46. During pyrolysis, with the decomposition of the organic matters and reconstruction of the remaining parts, biomass transformed into char (not the ultimate biochar), and AAEMs were then bonded to the char in the form of C–O–Met+ or C–O–Met2+–O–C (Met+ represents K+, and Met2+ represents Ca2+ and Mg2+)47. Once the bonds between AAEMs and char were attacked by free radicals which were formed in pyrolysis, elemental AAEMs were formed47,48,49,50. As these species are not stable, they would be easily oxidized to form metal oxides and react with H2O, which was released from biomass during pyrolysis, to form AAEM hydroxides (see Equation 1, M represents elemental AAEMs, such as K, Ca, or Mg). These AAEM hydroxides could be the source of released OH− in the solution. The decomposition of cellulose and lignin18,51 lead to the generation of CO2. CO2 may react with H2O and newly formed AAEM hydroxides to form various carbonates (see Equations 2 and 3). Thus, in addition to the carbonates contained in the raw biomass, the newly formed carbonates during pyrolysis could also be the source of CO32− in the solution. The Si species are much more stable than other inorganic species in biomass18,52. It is reported that the main forms of Si in wheat biomass are amorphous silica and silicate esters53,54, the forms of these Si species would change when the water in biomass evaporated and the organic matters decomposed during pyrolysis, some of the Si species would transform into quartz (see Fig. 2) and dehydroxylated silicates18, some of them would transformed into alkali silicates (such as K2SiO3)52. Without the protection of organic matters, the exposed Si species can be easily released to the solution. Among the Si species formed on biochar, alkali silicates are soluble compounds, the solutions of which contain a wide variety of polysilicate ions55 (consist with the ATR-FTIR results of raw biochar filtrates). Thus alkali silicates are probably the Si species released into water or Zn solution.

|

|

|

From the proposed evolution processes of the anions, we find that the formation of these ions are closely related to the decomposition of biomass, and the higher degree of decomposition (higher pyrolysis temperature) will lead to the higher amounts of OH−, CO32−, and Si species presented on biochar surface. Some previous studies have also found this phenomenon. Yuan et al. reported that the pHs and carbonate contents of biochar derived from different straws increased with pyrolysis temperature56; Xiao et al. found that the dissolved Si species released from biochar prepared by rice straw increased33 when the temperature increased from 250 °C to 700 °C.

The Immobilization Mechanism of Zn on PN and WS Biochars

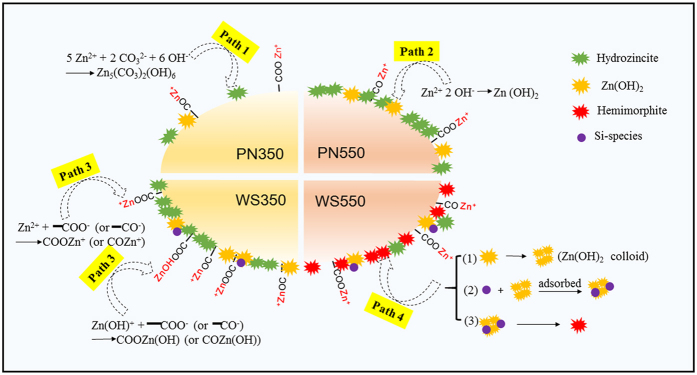

The formation of various ashes on biochars is the premise for Zn immobilization; and the formation of different Zn species is the immobilization mechanism of Zn on PN and WS biochars. The formation processes of the main Zn species (the fractions of which are higher than 10%) on different biochars are proposed and described as follows (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. The formation process of the main Zn species on different biochars.

For PN350 and WS350, once biochars were added into Zn solution, the OH− and CO32−, which were formed on biochar during pyrolysis56, tend to release into bulk solution. As OH− and CO32− were released from biochar, at the early stage of the diffusion the concentrations of OH− and CO32− in the solution close to biochar surface were much higher than those of bulk solution. Under this condition, when Zn2+ diffused to biochar surface, these ions were easily over-saturated and form hydrozincite and Zn(OH)2 (Fig. 4, Paths 1 and 2), and finally deposited on biochar surface. For biochars produced at low temperature (i.e. 350 °C), there existed a large portion of oxygen-containing functional groups (i.e. carboxyl and hydroxyl)24. When they presented in the solution with high pH, these functional groups will be deprotonated and adsorb Zn2+. During the process of Zn immobilization, the solution pHs were not controlled, they decreased from >9 to 7 with reaction time. From the calculation of Visual MINTEQ 3.1 (Supplementary Fig. S7), we find that two Zn species (i.e. Zn2+ and Zn(OH)+) could be involved in the reaction, and the proportion of Zn2+ was much higher than that of Zn(OH)+. The reactions were shown in Fig. 4, Path 3. Although the sorption mechanisms of PN350 and WS350 are the same, the sorption capacity of Zn on PN350 are much lower than that on WS350, which may be due to the lower amounts of OH−, CO32− and oxygen-containing functional groups formed on PN350 when compared with those formed on WS350. This phenomenon implied that different feedstocks have different degree of decomposition under the same pyrolysis temperature, which would lead to different sorption performances of biochars.

For PN550 and WS550, with the volatilization of organic matters and completion of thermal decompositions, the ash content increased, which made the fraction of Zn precipitates/minerals close to 100%. Compared with PN350, PN550 contained much more CO32− and OH−, thus the sorption capacity of Zn on PN550 was higher than that of PN350. For WS550, a large fraction of hemimorphite was formed. This was due to a considerable amount of released Si species. The formation of hemimorphite on WS550 can be divided into three steps57 (Fig. 4, Path 4): (1) the formation of colloid of Zn(OH)2 under alkaline condition, (2) the adsorption of dissolved silicates on Zn(OH)2 colloid and co-precipitation of silicate and Zn(OH)2, and (3) the reconstruction of the co-precipitates structure and formation of amorphous hemimorphite. Due to the complexity of the sorption system and short reaction time, the well-crystallized hemimorphite was unlikely to form. Thus, it cannot be detected by the method of XRD. Although there were also some Si species released from WS350, only a small portion of hemimorphite was formed. This may be caused by the low amounts of OH− and Si species released from WS350 biochar.

The formation of different Zn species on biochars confirmed heterogeneous property of these materials which resulted in the co-existence of various sorption mechanisms during Zn retention by biochars. The consumption of OH−, CO32−, or the sorption sites (oxygen-containing functional groups) on biochars by Zn2+ to form different Zn species led to the release of Ca2+ and Mg2+. When the studied raw biochars were added into the acid solutions, the ions OH− and CO32− in biochar were consumed and even some oxygen-containing functional groups were protonated. This was against the formation of different Zn species, which could lead to the decrease in the sorption capacities of Zn on biochars.

Conclusion

The ash in PN and WS biochars played important role on Zn immobilization. The higher pyrolysis temperature on the feedstock leads to the higher sorption capacity of Zn2+ and the larger fraction of Zn precipitates/minerals on biochar. Hydrozincite and Zn(OH)2 were the main species formed on PN350, PN550, and WS350; while on WS550, besides hydrozincite, a large fraction of hemimorphite was formed. The formation of OH−, CO32−, and Si species on biochars and the release of these species played predominant role on Zn immobilization.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of Raw Biochars and De-ashed Biochars

Biochars derived from PN and WS were prepared in a patented biochar reactor (NO. ZL2009 2 0232191.9) under oxygen-limited conditions. According to the decomposition rule of the feedstocks obtained from thermal analysis, 350 °C and 550 °C were selected as the pyrolysis temperatures (See Supplementary S2). To remove the ash on biochars, HCl/HF (1.0 M, v/v 1:1) solution was used to wash the raw biochars for several times. The details for biochar preparation were shown in Supplementary S2. The biochar sample derived from PN (WS) at 350 °C and 550 °C were denoted as PN350 (WS350) and PN550 (WS550), respectively. The de-ashed biochar were denoted as PN350D, PN550D, WS350D, and WS550D.

Sorption Kinetics and Sorption Isotherms

One hundred milligram of raw biochars or de-ashed biochars were added into 25 mL of Zn(NO3)2 solutions in 50 mL vials. These vials were shaken at 200 rpm at 25 °C. For raw biochars, the Zn2+ concentration in Zn(NO3)2 solution was 150 mg L−1 and the pH of the solution was not adjusted. For the sorption experiments of de-ashed biochars, the Zn2+ concentration was 50 mg L−1 and the pH of the solution was adjusted to 7 buffered by 5 mM MOPs. The samples were withdrawn at appropriate time intervals, then the mixture was filtered with a 0.45 μm membrane, and the Zn2+ concentrations of the filtrates were determined. The sorption capacity of biochar in each time interval was obtained by Supplementary Equation S1. The concentrations of CO32−, Si species, PO43−, Ca2+, and Mg2+ were also determined in the samples withdrawn at 120 h, then concentrations of these five species in the filtrates of blank samples (0.1 g of biochar + 25 mL of water) at 120 h were determined for comparison. The concentrations of Zn2+, Ca2+ and Mg2+ were determined using Atomic Absorption Spectrometer (AAS, Hitachi-Z2000, High-Technologies Corporation, Japan); the concentrations of CO32− were determined using titration method44; the concentrations of Si species were determined using Inductively Coupled Plasma − Atomic Emission Spectrometer (ICP-AES, OPTIMA 8000, PerkinElmer, USA); and the concentrations of PO43− were determined using molybdate-ascorbic acid method. Two parallel samples were applied in sorption samples. Sorption isotherms were performed the same way as sorption kinetics except for the initial concentrations of Zn2+ applied (see Supplementary S6).

Effect of Initial pH

Fifty milligram of raw biochars or de-ashed biochars were added into 23 mL of deionized (DI) water in 50 mL vials. These vials were shaken at 200 rpm at 25 C for 3 day equilibrium. Then the pHs of the mixtures in these vials were adjusted to 2–10. Certain amount of Zn(NO3)2 stock solution was dripped into each vial to make the initial concentration of Zn2+ to be 150 mg L−1 for raw biochar and 50 mg L−1 for de-ashed biochar. DI water was then added into the vial to make the solution volume up to 25 mL. The following procedure was the same as that of isotherms experiments and the sorption capacity of biochar was obtained by Supplementary Equation S6.

Characterization of Feedstocks and Biochars

The thermal properties of PN and WS were obtained using a Thermogravimertic Analyzer (TGA, Pyris 1 TGA, PerkinElmer, USA) at 20 °C/min up to the final temperature of 700 °C under a flow of N2. The functional groups of biochar and the Si species in the filtrates of raw biochar were analyzed using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR, Nicolet FTIR IS10, Thermo Scientific, USA). The methods of sample preparation and data analysis are shown in Supplementary S8. The surface of biochar was analyzed with X-ray Photoelectron Spectrometer (XPS, PHI-5000 Versaprobe, ULVAC-PHI, Japan) using an Al Kα excitation radiation. The pHs of raw biochars and pHs of point of zero charge (pHPZC) of de-ashed biochars were obtained by the pH drift method in Supplementary S9 and S10. The contents of K, Ca, Mg, Al, Fe, Zn, and P in biochars were analyzed after the microwave digestion of biochars with HNO3-HF-H2O2 (U.S. EPA 3502)58. The concentrations of K, Al, and Fe in the digestion solution were determined with ICP-AES. The digestion experiments were conducted in duplicate for each biochar.

Characterization of Zn Species on Biochars

The minerals in biochars were analyzed by X-ray Powder Diffraction (XRD). The tests were performed on a Rigaku, Ultima IV Diffractmeter (Rigaku Corporation, Japan), and Cu Kα radiation generated at 40 kV/40 mA, data were collected in the range (2θ) from 0° to 60° with the scan step of 0.02°. The minerals in the samples were identified using the XRD data analysis software (MDI JADE 6.5) and its corresponding powder diffraction file (PDF) database. The Zn species on biochars were analyzed by the method of extended X-ray Absorption Fine Structure (EXAFS) spectroscopy in fluorescence modes. Zn K-edge (9659 eV) measurements were carried out at beamline BL14W at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility Center (SSRF). Principal Component Analysis (PCA) accompanied with Linear Combination Fitting (LCF) were used for species identification and quantification. The details of EXAFS spectra collection and data processing were shown in Supplementary S11.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Qian, T. et al. A new insight into the immobilization mechanism of Zn on biochar: the role of anions dissolved from ash. Sci. Rep. 6, 33630; doi: 10.1038/srep33630 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation for Young Scientists of China (41501247), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41422105, 21537002, 41401252), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province of China (BK20141047), and Jiangsu Planned Projects for Postdoctoral Research Funds (1402117C). We would like to thank the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility for use of the synchrotron facilities at beamline BL14W.

Footnotes

Author Contributions T.Q. conceived and carried out most of the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; Y.W. and T.Q. analyzed the EXAFS data; T.F. conducted the EXAFS experiments; D.Z. supervised this work; D.Z. and G.F. edited this manuscript and provided important advices. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the manuscript.

References

- Ebbs S. D. & Kochian L. V. Toxicity of zinc and copper to Brassica species: Implications for phytoremediation. J. Environ. Qual. 26, 776–781 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Tkalec M. et al. The effects of cadmium-zinc interactions on biochemical responses in tobacco seedlings and adult plants. Plos one 9, e87582 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaney R. Zinc phytotoxicity. In Zinc in soils and plants (ed. Robson A. D.) 135–150 (Perth, 1993). [Google Scholar]

- Beyer W., Green C., Beyer M. & Chaney R. Phytotoxicity of zinc and manganese to seedlings grown in soil contaminated by zinc smelting. Environ. Pollut. 179, 167–176 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maderova L. & Paton G. I. Deployment of microbial sensors to assess zinc bioavailability and toxicity in soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 66, 222–228 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald C. A. et al. Relative impact of soil, metal source and metal concentration on bacterial community structure and community tolerance. Soil Biol. Biochem. 42, 1408–1417 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Khellaf N. & Zerdaoui M. Phytoaccumulation of zinc by the aquatic plant, Lemna gibba L. Bioresour. Technol. 100, 6137–6140 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W. et al. Hyperaccumulation of zinc by Corydalis davidii in Zn-polluted soils. Chemosphere 86, 837–842 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barone A., Ebesh O., Harper R. G. & Wapnir R. A. Placental copper transport in rats: effects of elevated dietary zinc on fetal copper, iron and metallothionein. J. nutr. 128, 1037–1041 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyorffy E. J. & Chan H. Copper deficiency and microcytic anemia resulting from prolonged ingestion of over–the–counter zinc. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 87 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen B. T. et al. Long-term black carbon dynamics in cultivated soil. Biogeochemistry 92, 163–176 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson C. J., Fitzgerald J. D. & Hipps N. A. Potential mechanisms for achieving agricultural benefits from biochar application to temperate soils: a review. Plant Soil 337, 1–18 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Cao X. D., Ma L. N., Liang Y., Gao B. & Harris W., Simultaneous Immobilization of Lead and Atrazine in Contaminated Soils Using Dairy-Manure Biochar. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 4884–4889 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J. H., Hsu S. H. & Wang S. L. Effects of rice straw ash amendment on Cu solubility and distribution in flooded rice paddy soils. J. Hazard. Mater. 186, 1801–1807 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keith A., Singh B. & Singh B. P. Interactive Priming of Biochar and Labile Organic Matter Mineralization in a Smectite-Rich Soil. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 9611–9618 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchimiya M., Wartelle L. H. & Boddu V. M. Sorption of Triazine and Organophosphorus Pesticides on Soil and Biochar. J. Agr. Food Chem. 60, 2989–2997 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad M. et al. Biochar as a sorbent for contaminant management in soil and water: A review. Chemosphere 99, 19–33 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James A. & Stephen J. Characteristics of biochar: Microchemical properties. In Biochar for Environmental Management: Science and Technology (ed. Lehmann J. & Joseph S.) 33–49 (London, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C. H. et al. Oxidation of black carbon by biotic and abiotic processes. Org. Geochem. 37, 1477–1488 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Chen B., Zhou D. & Zhu L. Transitional adsorption and partition of nonpolar and polar aromatic contaminants by biochars of pine needles with different pyrolytic temperatures. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42, 5137–5143 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Chen B., Zhou D. & Chen W. Bisolute sorption and thermodynamic behavior of organic pollutants to biomass-derived biochars at two pyrolytic temperatures. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 12476–12483 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale S. et al. Effects of chemical, biological, and physical aging as well as soil addition on the sorption of pyrene to activated carbon and biochar. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 10445–10453 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. Q. et al. Pyrolytic temperature dependent and ash catalyzed formation of sludge char with ultra-high adsorption to 1-naphthol. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 2602–2609 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan K. Y. & Xu Z. H. Biochar: Nutrient properties and their enhancement. In Biochar for Environmental Management: Science and Technology (ed. Lehmann J. & Joseph S.) 67–81 (London, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- Pan J. J., Jiang J. & Xu R. K. Adsorption of Cr(III) from acidic solutions by crop straw derived biochars. J. Environ. Sci.-China 25, 1957–1965 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beesley L. & Marmiroli M. The immobilisation and retention of soluble arsenic, cadmium and zinc by biochar. Environ. Pollut. 159, 474–480 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo L. C. et al. Sorption and desorption of cadmium and zinc in two tropical soils amended with sugarcane-straw-derived biochar. J. Soil. Sediment. 16, 226–234 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Xu X. et al. Removal of Cu, Zn, and Cd from aqueous solutions by the dairy manure-derived biochar. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R. 20, 358–368 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betts A. R., Chen N., Hamilton J. G. & Peak D. Rates and mechanisms of Zn2+ adsorption on a meat and bonemeal biochar. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 14350–14357 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner A. et al. Biochar-induced formation of Zn–P-phases in former sewage field soils studied by PK-edge XANES spectroscopy. 178, 582–585 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee A., Zimmerman A. R. & Harris W. Surface chemistry variations among a series of laboratory-produced biochars. Geoderma 163, 247–255 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Budai A. et al. Surface Properties and Chemical Composition of Corncob and Miscanthus Biochars: Effects of Production Temperature and Method. J. Agr. Food Chem. 62, 3791–3799 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao X. et al. Transformation, morphology, and dissolution of silicon and carbon in rice straw-derived biochars under different pyrolytic temperatures. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 3411–3419 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. W. et al. Characterization of biochars produced from cornstovers for soil amendment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44, 7970–7974 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho Y. S. & McKay G. Pseudo-second order model for sorption processes. Process Biochem. 34, 451–465 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Chien S. H. & Clayton W. R. Application of elovich equation to the kinetics of phosphate release and sorption in soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 44, 265–268 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y. T. et al. Adsorption mechanism of Cu2+ from aqueous solution by chitosan-coated magnetic nanoparticles modified with α-ketoglutaric acid. Colloid. Surface. B. 74, 244–252 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tütem E., Apak R. & Ünal Ç. F. Adsorptive removal of chlorophenols from water by bituminous shale. Water Res. 32, 2315–2324 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Weber W. J. & Morris J. C. Kinetics of adsorption on carbon from solution. Journal of the Sanitary Engineering Division 89, 31–60 (1963). [Google Scholar]

- Foo K. Y. & Hameed B. H. Insights into the modeling of adsorption isotherm systems. Chem. Eng. J. 156, 2–10 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Sarret G. et al. Zn speciation in the organic horizon of a contaminated soil by micro-X-ray fluorescence, micro- and powder-EXAFS spectroscopy, and isotopic dilution. Environ. Sci. Technol. 38, 2792–2801 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaure M. P. et al. Quantitative Zn speciation in a contaminated dredged sediment by μ-PIXE, μ-SXRF, EXAFS spectroscopy and principal component analysis. Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac. 66, 1549–1567 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Scheinost A. C., Kretzschmar R., Pfister S. & Roberts D. R. Combining selective sequential extractions, X-ray absorption spectroscopy, and principal component analysis for quantitative zinc speciation in soil. Environ. Sci. Technol. 36, 5021–5028 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pansu M. & Gautheyrou J. Handbook of Soil Analysis: Mineralogical, Organic and Inorganic Methods (ed. Pansu M. & Gautheyrou J.) 616–617 (Berlin, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- Socrates G. Organic silicon compounds In Infrared and Raman characteristic group frequencies: tables and charts. (ed. Socrates G.) 246–247 (New York, 2001). [Google Scholar]

- Hawkesford M. et al. Functions of Macronutrients In Marschner’s mineral nutrition of higher plants. (ed. Marschner H.) 165–172 (San Diego, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- Sonoyama N. et al. Interparticle Desorption and Re-adsorption of Alkali and Alkaline Earth Metallic Species within a Bed of Pyrolyzing Char from Pulverized Woody Biomass. Energ. Fuel. 20, 1294–1297 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Keown D. M., Favas G., Hayashi J. i. & Li C. Z. Volatilisation of alkali and alkaline earth metallic species during the pyrolysis of biomass: differences between sugar cane bagasse and cane trash. Bioresour. Technol. 96, 1570–1577 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quyn D. M., Wu H. & Li C. Z. Volatilisation and catalytic effects of alkali and alkaline earth metallic species during the pyrolysis and gasification of Victorian brown coal. Part I. Volatilisation of Na and Cl from a set of NaCl-loaded samples. Fuel 81, 143–149 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Li C. Z., Sathe C., Kershaw J. & Pang Y. Fates and roles of alkali and alkaline earth metals during the pyrolysis of a Victorian brown coal. Fuel 79, 427–438 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q. et al. Mechanism study of wood lignin pyrolysis by using TG–FTIR analysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 82, 170–177 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Okuno T. et al. Primary release of alkali and alkaline earth metallic species during the pyrolysis of pulverized biomass. Energ. Fuel. 19, 2164–2171 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis S. C. The uptake and transport of silicon by perennial ryegrass and wheat. Plant Soil 97, 429–437 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- Broadley M. et al. Beneficial elements In Marschner’s mineral nutrition of higher plants. (ed. Marschner H.) 257–258 (San Diego, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- Miniham A. Silicates. In Ullmann’s encyclopedia of industrial chemistry (ed. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co.) 55–56 (Weinheim, 2005). [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J. H. et al. The forms of alkalis in the biochar produced from crop residues at different temperatures. Bioresour. Technol. 102, 3488–3497 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata H., Matsunaga M. & Hosokawa K. Analytical study of the formation process of hemimorphite-part I analysis of the crystallization process by the co-precipitation method. Zairyo-to-Kankyo 42, 225–233 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA). Microwave assisted acid digestion of siliceous and organically based matrics. In Test Methods for Evaluating Solid Waste, Method 3052; U.S. EPA: Washington, D.C. 1996.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.