Abstract

Polyphenols exert a large range of beneficial effects in the prevention of age-related diseases. We sought to determine whether an extract of olive and grape seed standardized according to hydroxytyrosol (HT) and procyanidins (PCy) content, exerts preventive anti-osteoathritic effects. To this aim, we evaluated whether the HT/PCy mix could (i) have in vitro anti-inflammatory and chondroprotective actions, (ii) exert anti-osteoarthritis effects in two post-traumatic animal models and (iii) retain its bioactivity after oral administration. Anti-inflammatory and chondroprotective actions of HT/PCy were tested on primary cultured rabbit chondrocytes stimulated by interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β). The results showed that HT/PCy exerts anti-inflammatory and chondroprotective actions in vitro. The preventive effect of HT/PCy association was assessed in two animal models of post-traumatic OA in mice and rabbits. Diet supplementation with HT/PCy significantly decreased the severity of post-traumatic osteoarthritis in two complementary mice and rabbit models. The bioavailability and bioactivity was evaluated following gavage with HT/PCy in rabbits. Regular metabolites from HT/PCy extract were found in sera from rabbits following oral intake. Finally, sera from rabbits force-fed with HT/PCy conserved anti-IL-1β effect, suggesting the bioactivity of this extract. To conclude, HT/PCy extract may be of clinical significance for the preventive treatment of osteoarthritis.

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a common inflammatory joint disease affecting a growing part of the elderly1 and is associated with a strong socio-economic impact2. On a pathophysiological point of view, OA is characterized by progressive cartilage loss, subchondral bone remodeling, osteophyte formation, and joint tissues inflammation3,4. Altered joint loading due to instability of the joint or ligament injury represents a significant risk factor for the onset and the progression of OA in humans4,5,6. From a molecular point of view, OA is a vicious cycle of inflammation and cartilage degradation. Abnormal mechanical loading causes an alteration in the metabolism of joint cells leading to a release of enzymes and inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β). IL-1β then stimulates the synthesis of nitric oxide (NO), prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs)7,8. Among these proteases, MMP-13 is overexpressed in OA and mediates type II collagen and aggrecan breakdown which are the essential constituents of cartilaginous extracellular matrix (ECM)9. Fragments of aggrecan (e.g. NITEGE, VIPEN, DIPEN) and collagen are released from cartilage and induce the activation of synoviocytes and macrophages, resulting in paracrine secretion of cytokines and MMPs into the synovial fluid10,11. The released catabolic molecules are feeding the amplification loop of inflammation. For these reasons, inflammation and catabolism of ECM represent key events that can be targeted for the identification of novel therapeutic interventions in OA.

Despite recent advances in the understanding of the cellular and molecular processes involved in OA pathogenesis, curative treatments are still lacking. Pharmacological drugs currently available to treat OA patients only alleviate inflammation and pain but do not slow down, stop, or reverse the progression of the cartilage degradation and other tissue damages12. In this context, there is a growing interest in developing therapeutic strategies able to collectively blunt the progressive degradation of joint tissues while improving the relief of symptomatic inflammation-associated pain. Interestingly, numerous studies have recently highlighted the potential of natural compounds including nutraceuticals, to slow down or treat OA, thereby paving the way for new therapeutic approaches13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22.

Among these nutraceuticals, hydroxytyrosol (HT) is a bioactive phenolic compound mainly found in olive leaf and oil. HT is known for its powerful antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties23,24. Previous studies have shown that oral intake of HT significantly decreased the in vivo acute inflammation triggered by LPS through the inhibition of PGE2 and NO production pathways24. Moreover, HT has the ability to relieve pain as described in a double-blind placebo-controlled trial conducted on 25 patients with knee OA25. Procyanidins (PCy) are active polyphenols found in many plants such as grape, pine bark, cocoa and raspberry. PCy exert numerous health promoting effects related to their antioxidant activity, but also to their ability to inhibit the synthesis of numerous inflammatory mediators26. Previous studies have thus shown that PCy from grape seed extract (GSPE) had the ability to alleviate inflammation in vitro and in vivo through the inhibition of NO, PGE2 and IL-1β production27,28. Interestingly, it has also been suggested that PCy may exert a protective effect on the ECM degradation as observed in OA through their targeted affinity with collagen29. A preventive effect of procyanidin B3 isoform on cartilage degradation has been reported recently in a murine model of OA23. Considered as a whole, these data raise the possibility that a combination of HT and PCy may exert complementary effects during the onset of OA. A mix of both extracts could be able to prevent both inflammation and joint tissue degeneration associated with disease. Despite this large body of data, some key aspects such as the fate of HT and PCy following oral administration still remains to be documented. As a matter of fact, the biological activities in vivo of polyphenol deeply depend on their bioavailability. In addition, after oral ingestion, polyphenols undergo several chemical modifications before reaching the bloodstream22. In this context, the evaluation of the bioavailability and the bioactivity are important parameters to be considered.

With respect to the large spectrum of OA symptoms, ranging from cartilage and bone alteration to synovial inflammation, the optimal treatment for OA would be a therapy that can not only blunt the progressive degradation of joint tissues but also improve the relief of inflammation-associated pain. In light of the promising data regarding the HT and PCy effects, we were interested in deciphering whether a combination of natural HT and PCy could simultaneously prevent inflammatory and catabolic effects related to the onset of OA. To address this issue, we used freshly isolated rabbit articular chondrocytes to test whether pre-treatment with HT/PCy extract mix could decrease the levels of IL-1β-induced inflammatory and catabolic markers. We also sought to determine the effect on the onset of disease of HT/PCy on two post-traumatic OA models in mouse and rabbit. Finally, we embarked on experiments to determine the bioavailability and bioactivity of HT/PCy extract mix and their metabolites in sera following force-fed gavages in rabbits.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of HT/PCy solution

Oleogrape®SEED, an extract from olive and grape seed (HT/PCy) was provided by Grap’Sud Union (Cruviers Lascours, France). It is composed of 6.5 mg HT/100 g and 30 mg PCy/100 g. HT/PCy extract was dissolved in high glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham-MA, USA) or in saline solution NaCl 0.9% (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint-Louis-MO, USA). Solutions were sterilized by filtration through 0.22 μm pore membranes.

Ethical considerations in animal procedures

All animal procedures were approved by the institution’s animal welfare committee (CEEA Pays de la Loire. Agreement no. 02099.01) and were conducted in accordance with the European’s guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals (2010/63/UE). Mice were housed in the animal facility of Nantes Faculty of Medicine (Agreement no. C44015). Rabbits were hosted in the animal facility of Nantes Faculty of Medicine or in Centre for Research and Preclinical Investigation (ONIRIS Agreement no. E44271).

Experimental OA models

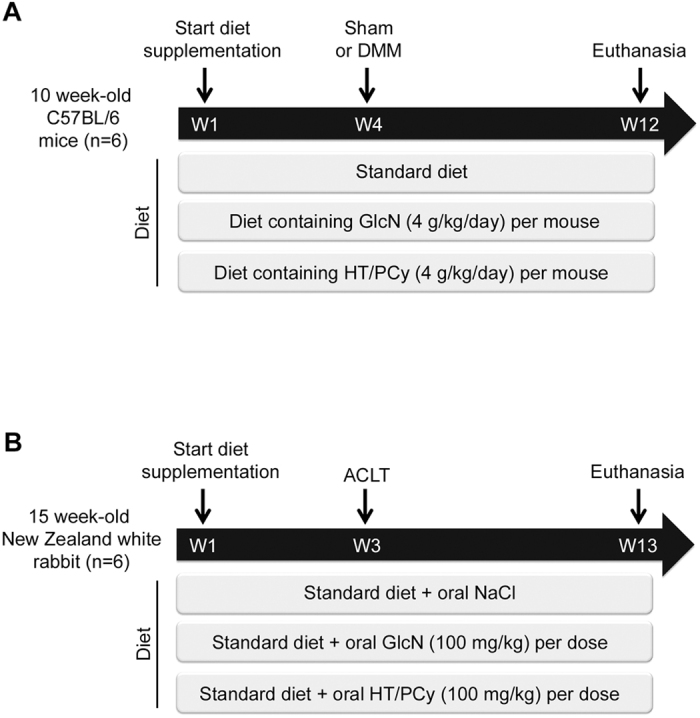

Twenty-four 10 week-old male C57/BL6 mice were obtained from Janvier Labs (Saint Berthevin, France) and eighteen 15 week-old female New Zealand white rabbits were purchased from Hypharm-Grimaud (Roussay, France). All animals had reached full skeletal maturity at the time of the study. After one week of acclimatization, mice and rabbits were randomly assigned into 4 and 3 groups (n = 6 per group), respectively. In mice experiment, the sham group and the control group received a standard powder diet RM1 (Special Diet Services, Essex, UK) and experimental groups received either a standard diet enriched with D-(+)-glucosamine(GlcN) hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich) or with HT/PCy extract for 12 weeks. Based on previous in vitro and in vivo studies conducted in cartilage explants and ACLT rabbit model24,30, GlcN hydrochloride was used as positive control (Fig. 1A). Diet supplementation rates were calculated considering that mice consumed 4 g per day, which correspond to 4 g/kg/day of GlcN or HT/PCy extract. OA was experimentally induced in mice by bilateral destabilization of the medial meniscus (DMM) 4 weeks after the beginning of diet supplementation in order to assess the preventive effects of HT/PCy. Mice were euthanized 8 weeks after surgery by cervical dislocation (Fig. 1A). In rabbit experiment, the control group received a saline solution of NaCl 0.9% (Sigma-Aldrich) and experimental groups received GlcN (100 mg/kg) or HT/PCy (100 mg/kg) in 1 mL of saline solution every two days, administrated through gastric gavage for consecutive 13 weeks. Three weeks after the beginning of gavage, rabbits underwent a destabilization of the right joint induced by anterior cruciate ligament transection (ACLT). Rabbits were euthanized by an overdose of barbiturates 10 weeks after surgery (Fig. 1B). All joints were dissected for further histological examinations. One mouse in the control group was excluded from the analysis because the histological analysis revealed that the medial meniscotibial ligament had only been partially sectioned.

Figure 1. Experimental designs to evaluate the effectiveness of HT/PCy extract in animal models.

(A) Mice (n = 6 per group) were bilaterally subjected to surgical DMM or sham operated. HT/PCy (4 g/kg) or GlcN (4 g/kg) were administrated daily by diet supplementation for 12 weeks starting 4 weeks before surgery. A third group was fed with standard diet (control group). Cartilage degradation was evaluated 8 weeks after DMM. (B) Rabbits (n = 6 per group) underwent anterior cruciate ligament transection (ACLT) of the right knee. Vehicle (NaCl 0.9%; negative control), glucosamine (GlcN) (100 mg/kg; positive control) or HT/PCy (100 mg/kg) was orally administrated every two days for 13 weeks starting 3 weeks before surgery. OA severity was evaluated at 10 weeks following surgery by radiographic and histological OARSI scoring.

Histological staining and OARSI scoring

After euthanasia, knee samples from each animal were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Mouse and rabbit joints were decalcified using EDTA 0.5 M (pH 7.4) and DC3 solutions (VWR, Radnor, PA, USA) respectively. Dehydration was performed subsequently. Specimens were embedded in paraffin, and cut in 5 μm thick sections using microtome. Safranin O fast green and hematoxylin-eosin-safran (HES) stainings have been performed to visualize joint cells and matrices. Histological assessment was performed using the OsteoArthritis Research Society International (OARSI) scoring system by 2 well-versed observers in a blind random manner31,32. The severity of OA lesions was scored on a scale ranging from 0 to 5 using parameters such as chondrocyte death, hypertrophy, clusters, loss of Safranin-O staining, surface alteration, and bone modifications (total maximum score 25). The scoring system used is presented in Supplementary Table 1. Scoring was performed at different levels of the joint; at least two joint regions have been analyzed for each sample.

Immunohistochemistry and image analysis

Immunohistochemistry was performed on deparaffinized and rehydrated sections with specific primary antibodies: type II collagen antibody (anti-mouse: 1:400, ab34712, Abcam and anti-rabbit: 1:100, 08631711, MP biomedicals), aggrecan antibody (anti-mouse: 1:100, ab1031, Merck Millipore and anti-rabbit: 1:100, MA3-16888, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and NITEGE antibody (anti-mouse: 1:500, PA1-1746, Thermo Fisher Scientific and anti-rabbit: 1:50, MBS442004, My Biosource (San Diego-CA, USA) for the detection of aggrecan cleavage. All sections were counterstained using Mayer’s hematoxylin (RAL Diagnostic, Martillac, France). Tissue staining was viewed using Nanozoomer 2.0 Hamamatsu slide scanner (Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan). Immunostaining intensity for NITEGE was quantified by determining the relative intensity of the stained articular cartilage matrix as previously described33. Briefly, images were converted into greyscale. The mean grey level values of 12 distinct regions of interest (50 × 50 pixels) from the femoral condyle and tibial plateau were determined. The value obtained was corrected by the mean of the gray levels of the extracellular matrix (10 × 10 pixels). Then, the corrected mean was subtracted from the blank (10 × 10 pixels). Finally, the value is expressed as fold increase over control condition. Measurements were performed using FIJI software.

Radiographic imaging and OA score

Radiographic pictures of the rabbit’s hind limbs (antero-posterior and lateral views) were taken using a Convix 300 system (Picker International Inc, Cleveland, OH, USA). Pictures were taken following euthanasia to evaluate structural damage in the joints. Knee OA severity was quantitatively assessed using a radiographic score inspired by Kellgren & Lawrence34 and Boulocher et al.35. The scoring was performed by 2 independent blind readers. The severity of OA lesions was scored using multiple parameters such as calcification of menisci, tendons and ligaments, number and localization of osteophytes, bone modifications, and joint space narrowing. The scoring system used is summarized in Supplementary Table 2.

Rabbit feeding and sera collection

Eight 15 week-old female New Zealand white rabbits were purchased from Hypharm-Grimaud. Animals were randomly divided into 2 groups (n = 4 per group). Control group was fed with saline solution (1 mL/kg) and experimental group received 6 doses of HT/PCy for 8 days. HT/PCy was administrated by gavage at the dose of 100 mg/kg (for cell culture) or 500 mg/kg (for UPLC-MS analysis) in saline solution as indicated in the figures legends. Venous blood was collected, centrifuged and sera were stored and frozen at −80 °C until their use in cell culture and Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (UPLC-MS) experiments.

Cell culture

Rabbit articular chondrocytes (RAC) were harvested from tibial plateau and femoral condyles of New Zealand White rabbits as previously described36. Cells were plated at passage 1 in 96-well plates at a density of 100,000 cells/cm2 and maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in control medium (10% FCS, 1% P/S). To analyze the preventive effects of native HT/PCy or their serum metabolites following digestion, cells were pre-incubated for 24 h in the presence of native HT/PCy at a concentration of 10 mg/L dissolved in DMEM supplemented with 5% FCS, 1% P/S or 2.5% of serum from force-fed rabbits in DMEM supplemented with 2.5% FCS, 1% P/S. Human recombinant IL-1β (1 ng/mL) (Millipore Corporation, Billerica-MA, USA) was then added for an additional 24 h.

NO, PGE2 and MMP-13 quantification

Nitrate/Nitrite colorimetric assay and Prostaglandin E2 EIA kits were obtained from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor-MI, USA), Rabbit and Human ELISA Kits for MMP-13 detection were purchased from Cloud-Clone Corp (Houston-TX, USA) and Abcam® (Cambridge, UK) respectively. The NO, PGE2 and MMP-13 levels measurements were performed according to manufacturer’s instructions.

RNA extraction and real-time PCR

RNA was extracted using NucleoSpin® RNA II kit (Macherey-Nagel, Hoerdt, France) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription was performed using SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed using Brilliant III® SYBR® Green Master Mix (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA) on the Mx3000P® QPCR System (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara-CA, USA). PCR primers were synthesized by Eurofins DNA Genomics (Ebersberg, Germany) and sequences are reported in Supplementary Table 3. β-actin was used as reference gene and results were expressed as relative expression levels using the Livak method37.

Extraction of phenolic compounds from serum

Sera (2.5 mL) from rabbit fed as described above were mixed with 7.5 mL of methanol for 2 min and ultrasonicated for 5 min. The mixture was centrifuged at 20,000 g for 10 min. The supernatant was collected and evaporated to dryness using a SpeedVac Concentrator. The dried extract was reconstituted in 200 μL of methanol/water (50:50 v/v). After centrifugation (20,000 g for 10 min), the supernatant was filtered through a PTFE 0.22 μm filter (Millipore Corporation) and stored at −80 °C until use for UPLC-MS analysis.

Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS)

Phenolic compounds analyses were carried out using a 1290 Infinity UPLC from Agilent Technologies. The UPLC system was coupled to an Esquire 3000 plus mass spectrometer from Bruker Daltonics (Wissembourg, France). 5 μL were injected into a Zorbax SB-C18 column (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.8 μm) from Agilent Technologies. Two different solvents were used as a mobile phase: solvent A (water/formic acid 99.9:0.1 v/v) and solvent B (acetonitrile/formic acid 99.9:0.1 v/v), at a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min and a gradient as follows in solvent A: 0 min 1% B, 0.4 min 1% B, 2 min 10% B, 6 min 35% B.7 min 50% B, 8.8 min 70% B, 10.8 min 92% B, 11 min 100% B, 12 min 100% B, 12.2 min 1% B, 15.2 min 1% B. The MS/MS parameters were set as follows: negative mode; capillary tension +4000 V; nebulizer 40 psi; dry gas 10 L/min; dry temperature 365 °C; and scan range m/z 100 to 1400. Data were processed using HyStar 3.2 software (Bruker Daltonics).

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was performed at least in triplicate. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Comparative studies were analyzed using an ANOVA test followed by post-hoc Fisher test with P values less than 0.05 considered as statistically significant.

Results

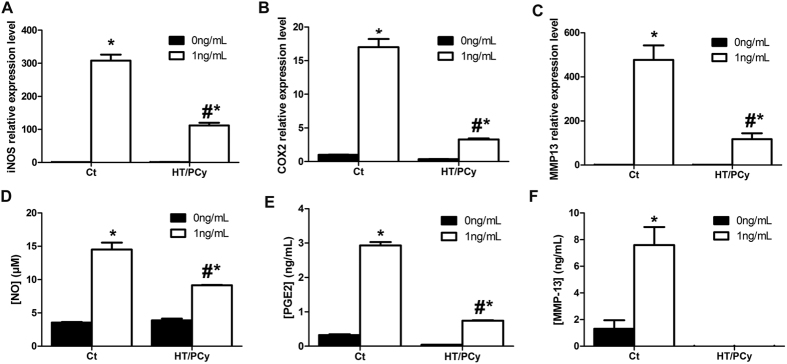

HT/PCy reduces IL-1β-induced levels of iNOS, COX2 and MMP13 transcripts and NO, PGE2 and MMP-13 production

We first evaluated whether HT/PCy treatment can modulate the expression levels of IL-1β-responsive genes involved in inflammation and catabolic processes in cartilage. RAC were pretreated with HT/PCy for 24 h then stimulated or not with IL-1β for 24 h. The expression of iNOS, COX2 and MMP13 transcripts were determined as well as associated products NO, PGE2 and MMP-13. As expected, results showed an increased expression of iNOS, COX2 and MMP13 in response to IL-1β treatment (Fig. 2). Interestingly, our results also demonstrated a significant decrease in IL-1β-induced iNOS, COX2 and MMP13 expression levels in HT/PCy condition (Fig. 2A–C). In addition to the gene expression levels, we monitored the synthesis of related products. Consistent with gene expression levels, the IL-1β-dependent NO, PGE2 and MMP-13 productions were also significantly decreased by the extracts in RAC (Fig. 2D–F). Of interest, HT/PCy totally suppressed the MMP-13 production triggered by IL-1β (Fig. 2F).These in vitro data demonstrated the anti-IL-1β effect of an HT/PCy pre-treatment in primary chondrocytes.

Figure 2. In vitro HT/PCy effects on iNOS, COX2 and MMP13 expression and NO, PGE2 and MMP-13 production.

RAC were cultured for 24 h with HT/PCy and treated for an additional 24 h with IL-1β (1 ng/mL; white bar) or without IL-1β (corresponding to 0 ng/mL condition; black bar). The relative expressions of iNOS (A), COX2 (B) and MMP13 (C) compared to β-actin were evaluated by real time RT-PCR. NO production (D) was assessed using Greiss reaction, PGE2 (E) and MMP-13 (F) productions were measured using ELISA assay. #p < 0.05 compared to the condition with IL-1β (1 ng/mL) alone, *p < 0.05 compared to the condition without IL-1β with the same extract solution.

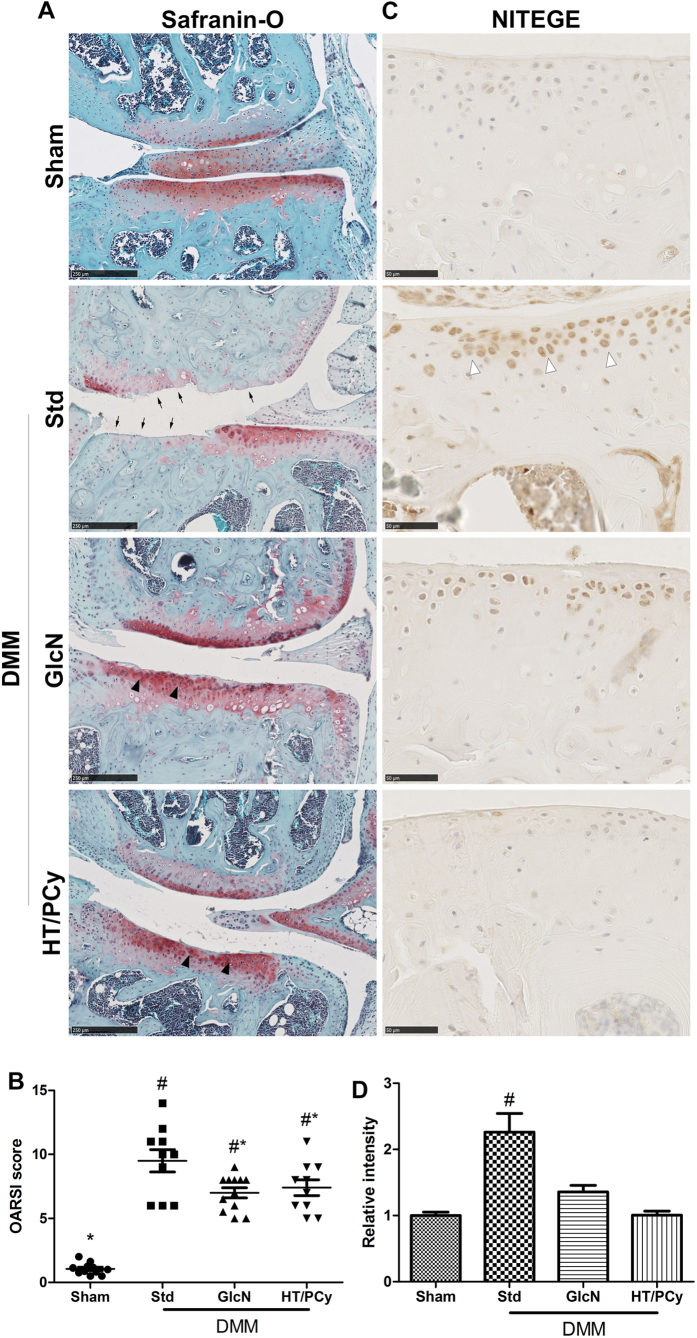

Reduced severity of surgically-derivated OA following administration of HT/PCy in DMM mice

To assess the safety of diet supplementation containing high dose of HT/PCy, the weight of the mice was monitored during 12 weeks. The initial and final body weights did not differ among the different experimental groups (data not shown) suggesting no adverse effects of HT/PCy. Safranin-O was used to evidence the glycosaminoglycan content from cartilage matrix. Sham-operated mice that received standard diet did not exhibit pathologic changes in articular cartilage (Fig. 3A). Eight-week post-DMM, sections of standard group reveals mid-stage OA which result in cartilage matrix delamination (black arrow) compared to sham group. In treated groups with GlcN or HT/PCy, the superficial zone was intact or presented only barely detectable superficial abrasion exhibiting safranin-O depletion. Moreover, some chondrocytes in treated groups were hypertrophic or organized in clusters demonstrating signs of early OA stage (black arrowhead; Fig. 3A). These histological observations were quantitatively confirmed using the OARSI scoring as shown in Fig. 3B. In standard group, OARSI score dramatically increased after DMM as compared to sham group. Of note, GlcN treated mice exhibited a significantly reduced OARSI score similar to that of HT/PCy treated mice.

Figure 3. HT/PCy enriched diet reduces the severity of mid-stage OA in DMM mice.

Mice (n = 6 per group) underwent sham surgery or DMM bilaterally. Mice received regular diet (Sham and Std groups) or diet supplemented with GlcN, HT/PCy for 12 weeks starting 4 weeks before surgery. Safranin O staining (A) and OARSI score (B) of sham or standard diet (Std), GlcN and HT/PCy diet groups at 8 weeks post-DMM. Immunohistochemical staining (brown signal) using antibody directed against NITEGE for the detection of aggrecan cleavage in sham or DMM mice receiving diet supplementation with GlcN, HT/PCy (C) and relative NITEGE staining intensity (D). *p < 0.05 compared to standard group, #p < 0.05 compared to sham group. Bar represents 250 μm (A) and 50 μm (C).

To further investigate whether HT/PCy could protect the cartilage degradation subsequent to surgery, ECM components were analyzed by immunohistology. As expected, type 2 collagen expression was not affected among the different experimental groups (data not shown). Aggrecan staining intensity was strongly decreased after DMM in standard group compared to sham. Conversely, supplementing the diet with GlcN or HT/PCy did not result in a decrease in aggrecan immunostaining following surgery (Supplementary Figure 1). To confirm the absence of aggrecan degradation, we used NITEGE immunostaining corresponding to specific proteases having MMPs and aggrecanase activities. Sham-operated mice had no significant effect on the immunostaining for NITEGE-degradation product (Fig. 3C). The effects of surgery on aggrecan cleavage were confirmed by intense NITEGE expression in non-calcified cartilage and particularly in the pericellular region of standard group compared to sham group (Fig. 3C, white arrowhead), as previously described33. In contrast, immunohistochemistry showed that GlcN and HT/PCy treatments reduced the level of NITEGE in DMM mice compared to standard-treated mice (Fig. 3C). Surgery induced a 2.2 fold increased in the immunostaining intensity of NITEGE staining in standard diet treated mice. Quantifications of staining reveal that GlcN and HT/PCy dramatically reduced NITEGE immunostaining intensity to levels similar to that of sham operated mice (Fig. 3D). These data demonstrated that DMM surgery induced mid-stage OA lesions as compared to sham operated animals. Moreover, HT/PCy supplementation in DMM mice prevents from OA.

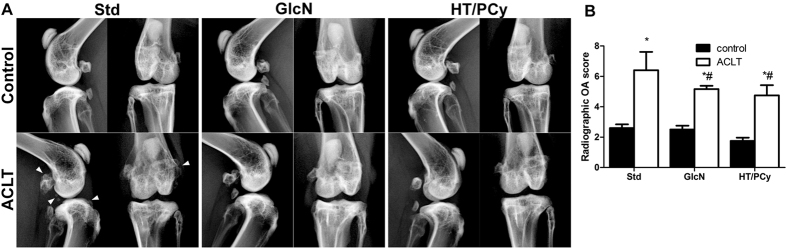

Reduced severity of surgically-derivated OA following administration of HT/PCy in ACLT rabbits

To strengthen the results obtained in a murine model of OA, we then evaluated the effects of diet supplementation with HT/PCy on a larger OA animal model. Taking into account that ACLT is closely related to the human clinical situation38, we examined the effects of HT/PCy enriched diet on OA severity induced by ACLT in rabbits. The severity of OA was firstly assessed by X-ray evaluation (Fig. 4). Non-operated knees (control) exhibit no joint alteration. In contrast, ACLT knees from rabbits fed with the standard diet (standard group) present OA pathological changes characterized by increased ligament calcification, osteophytes incidence and bone sclerosis (Fig. 4). Of interest, GlcN or HT/PCy intake decreased the lesion severity (Fig. 4A). Radiographic OA scoring reveals a significant decrease in treated groups compared to standard group. Our data also demonstrated that HT/PCy exerts similar effects on the X-Ray pathological OA changes when compared to GlcN (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4. HT/PCy decreased radiographic OA score on ACLT rabbit model.

Rabbits (n = 6 per group) underwent ACLT of the right knee. NaCl (Std), GlcN or HT/PCy were administrated every two days for 13 weeks starting 3 weeks before surgery. X-ray (A) and corresponding radiographic score (B) of non-operated knee (control) or operated knee (ACLT) untreated rabbits or treated with GlcN or HT/PCy at 10 weeks subsequence to surgery. *p > 0.05 compared to non-operated knee (control) within the same group; #p > 0.05 compared to ACLT receiving NaCl (Std) group. Arrowheads show osteophytes formation after ACLT.

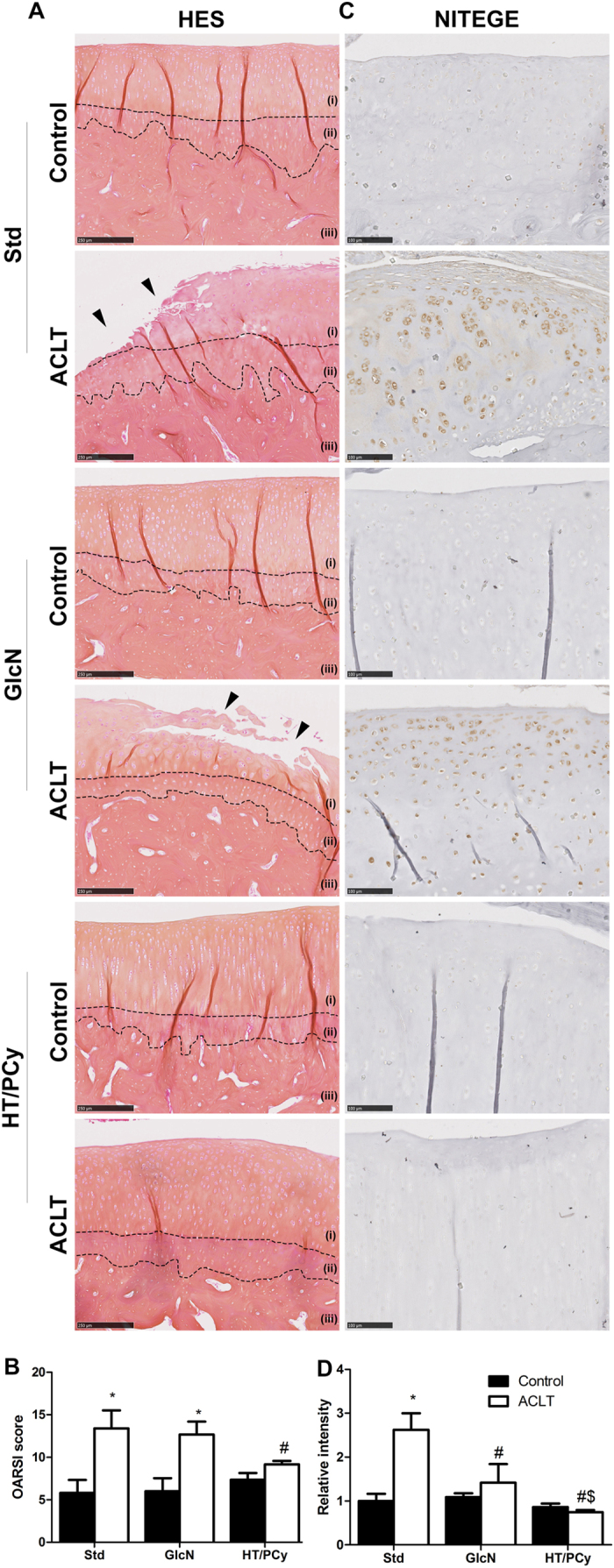

To further investigate the in vivo effect of HT/PCy, we questioned whether HT/PCy intake may also impact cartilage alteration and subchondral bone changes at the onset of OA. Figure 5 shows that the articular cartilage surface of non-operated knees was smooth and that chondrocytes were organized in three appropriately oriented, well-organized zones. Cartilage erosion from the surface down to the deepest zone was observed for the group of rabbit that undergone ACLT and received standard diet corresponding to mid-stage OA. In experimental ACLT group treated with GlcN, the erosion was extended from the surface to the mid zone. Interestingly, ACLT rabbits treated with HT/PCy did not show any sign of cartilage erosion, but only presented cartilage swelling (œdema). GlcN was not found to exhibit a detectable effect on OARSI score in the ACLT rabbit model (Fig. 5B). Consistent with results obtained in mice, HT/PCy intake significantly decreased OARSI score severity in post-traumatic OA rabbit model (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. HT/PCy supplementation reduces the severity of mid-stage OA in ACLT rabbits.

Rabbits (n = 6 per group) underwent ACLT of the right knee. NaCl (Std), GlcN or HT/PCy were orally administrated every two days for 13 weeks starting 3 weeks before surgery. HES staining of cartilage (A) and OARSI scores (B) of non-operated knee (control) or operated knee (ACLT) at 10 weeks post-surgery are shown. Immunohistochemical detection of aggrecan epitopes (NITEGE) (C) and relative staining intensity of the articular cartilage matrix (D) of standard diet (Std), GlcN and HT/PCy diet groups at 10 weeks after ACLT. (i) Non calcified-cartilage, (ii) calcified cartilage and (iii) sub-chondral bone. *p > 0.05 compared to non-operated knee (control) within the same group; #p > 0.05 compared to ACLT receiving NaCl (Std) group, $p > 0.05 compared to ACLT receiving GlcN. Bar represents 250 μm (A) and 100 μm (C).

To further decipher the effect of HT/PCy diet supplementation on cartilage matrix cleavage, type 2 collagen, aggrecan and NITEGE immunostainings were performed. As was observed in mice, the surgery did not affect type 2 collagen immunostaining in all groups (data not shown). On the contrary and as expected, surgery led to a substantial loss of aggrecan staining in comparison with non-operated knee. Interestingly, GlcN or HT/PCy intakes appear to prevent aggrecan degradation resulting from ACLT (Supplementary Figure 2). To specifically investigate the aggrecan cleavage, immunohistochemical detection of NITEGE epitope was performed. Non-operated knees among the different experimental groups had no significant immunostaining for NITEGE (Fig. 5C). However, ACLT led to intense NITEGE immunohistological detection in standard diet supplemented rabbits (standard). GlcN and HT/PCy gavages markedly reduced the level of aggrecan cleavage epitope induced by ACLT (Fig. 5C). Quantification of NITEGE intensity reveals that surgery strongly increased the intensity of NITEGE by 2.6-fold as compared to non-operated knee (control) in standard group. In addition, immunohistochemical detection showed that HT/PCy and GlcN did not affected NITEGE relative intensity in control knee compared to standard group. Interestingly, HT/PCy more drastically decreased the immunostaining intensity than GlcN (1.4-fold and 0.7-fold above non-operated knee (control) in standard group, respectively) (Fig. 5D).

Our results demonstrated that ACLT induced mid-stage OA, which causes pathological changes at X-ray and histological levels. Moreover, our results clearly confirmed, in a second model, the preventive effect of orally administrated HT/PCy on post-traumatic OA by analyzing the radiographic and histological changes. Interestingly, HT/PCy intake was found to be more potent than GlcN.

Mass spectrometry identification of phenolic metabolites in rabbit serum

Since in vivo preventive effects of HT/PCy were observed following oral administration, we then questioned whether the sera of rabbits fed with HT/PCy may contain the regular metabolites of phenolic compounds. These metabolites were identified by UPLC-MS from the phenolic extract of HT/PCy and are reported in Table 1. All metabolites were picked out by the time retention peak TR (min) and the transition of m/z [M–H]−. In serum of rabbits fed with HT/PCy, five metabolites from HT were found. Two HT derivatives were detected as hydroxytyrosol glucuronide and hydroxytyrosol sulfate, as reported in previous studies39,40. In addition, 2 tyrosol derivatives were also identified as tyrosol glucuronide and as tyrosol sulfate, as previously reported41. Finally, homovanillic acid sulfate was labeled39,41. Regarding rabbit’s metabolites derivating from PCy, nine metabolites were detected. Four catechin derivatives were identified. The peaks with the transitions were attributed to catechin glucuronide, catechin sulfate, methyl-catechin glucuronide and methyl-catechin sulfate, respectively42,43. Two epicatechin derivatives were attributed to epicatechin glucuronide and epicatechin sulfate, respectively42,43. In addition to proanthocyanidins, three other metabolites were detected as dihydroxyphenylvalerolactone sulfate44,45, dihydroxyphenylvaleric acid sulfate44, and hydroxyphenylpropionic acid44,46. None of these metabolites were found in the serum of rabbit force fed with NaCl. These results show the transformation of the extract by conjugation and its bioavailability in serum after oral intake.

Table 1. Mass spectrometry identification of phenolic metabolites in rabbit serum.

| Compounds | TR (min) | [M–H]− | MS/MS |

|---|---|---|---|

| HT | |||

| hydroxytyrosol glucuronide | 3.0 | 329 | 153 |

| hydroxytyrosol sulfate | 3.1 | 233 | 153 |

| homovanillic acid sulfate | 3.6 | 261 | 181 |

| tyrosol glucuronide | 5.5 | 313 | 137 |

| tyrosol sulfate | 5.7 | 217 | 137 |

| PCy | |||

| catechin glucuronide | 3.5 | 465 | 289 |

| epicatechin glucuronide | 3.8 | 465 | 289 |

| catechin sulfate | 4.0 | 369 | 289 |

| methyl catechin glucuronide | 4.2 | 479 | 303 |

| epicatechin sulfate | 4.4 | 369 | 289 |

| dihydroxyphenylvalerolactone sulfate | 4.5 | 287 | 207 |

| methyl catechin sulfate | 4.6 | 383 | 303 |

| dihydroxyphenylvaleric acid sulfate | 5.1 | 289 | 209 |

| hydroxyphenylpropionic acid | 5.2 | 165 | 121 |

Rabbits received 6 doses of HT/PCy (500 mg/mL) for 8 days, 2 hours after the last dose the serum was harvested. The characterization of the metabolites in the rabbit serum was based on their ion fragmentation in the MS and MS/MS modes. Metabolites were identified by the time retention (TR) (min) and the transition of m/z [M–H]−. Mass spectral characteristic of phenol metabolites in serum from rabbits fed a fraction HT/PCy.

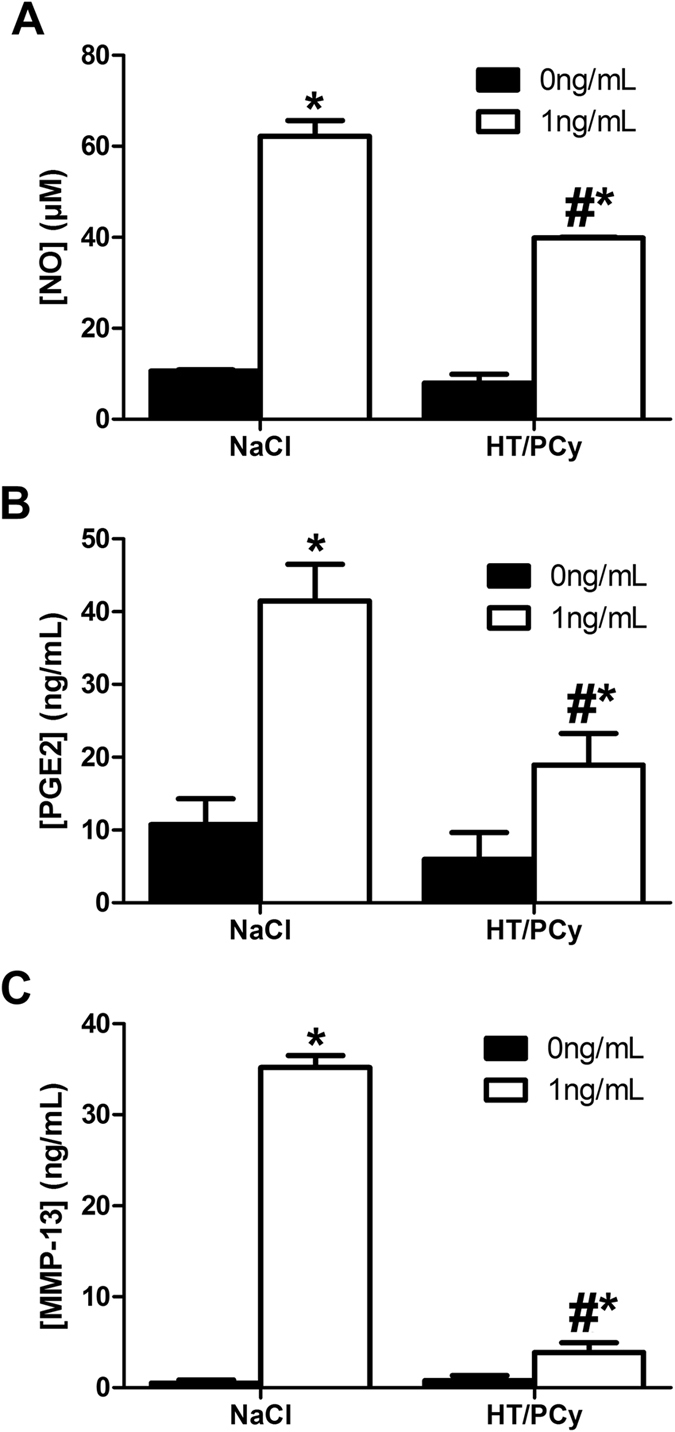

Sera from rabbits fed with HT/PCy reduces the IL-1β-induced levels of NO, PGE2 and MMP-13 production

To investigate the maintenance of the anti-IL-1β effects previously observed with native extract in vitro, we evaluated the anti-IL-1β effects of sera from rabbits after oral intake of HT/PCy. Results showed that serum from rabbit fed with HT/PCy extract down-regulated by 36% the NO production induced by IL-1β in RAC as compared to cells treated with serum from rabbit fed with saline (Fig. 6A). Similarly, serum from rabbit fed with HT/PCy extracts decreased by about 54% the PGE2 release triggered by IL-1β in RAC compared to control (Fig. 6B). Finally the serum from rabbit fed with HT/PCy extracts almost completely abolished the IL-1β-induced production of MMP-13 (Fig. 6C). Altogether, these results demonstrate that the sera of rabbit fed with HT/PCy contained metabolites with anti-IL-1β biological effects.

Figure 6. Effects of serum from rabbit fed with HT/PCy on the IL-1β-induced levels of NO, PGE2 and MMP-13 production.

Rabbits received (n = 3 per condition) 6 doses of HT/PCy (100 mg/kg) or saline solution (NaCl) for 8 days and serum were harvested 2 h after the last gastric gavage. RAC were cultured during 24 h in presence of serum from rabbit at a final concentration of 2.5% (v/v) and stimulated with IL-1β (1 ng/mL) or its vehicle which was NaCl (0 ng/ml) for an additional 24 h. The NO (A) and PGE2 (B) and MMP-13 (C) released in culture media were measured. #p < 0.05 compared to the NaCl condition with IL-1β (1 ng/mL), *p < 0.05 compared to the condition without IL-1β with the same extract solution.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that olive and grape extracts containing HT/PCy exhibit preventive anti-IL-1β effects in vitro on isolated rabbit chondrocytes, and provided in vivo evidence in two animal models of post-traumatic OA that the combination of HT and PCy exerts preventive effects on the onset of OA. Importantly, we demonstrated that the sera of rabbits fed with phenolic-rich extracts exhibit in vitro anti-IL-1β activities in chondrocytes, thereby strongly suggesting that HT and PCy retain their biological activities in serum after oral consumption.

Despite that OA is the most common inflammatory and degenerative joint disease, no curative or preventive treatment has yet been clinically implemented4,12. In search of innovative therapeutic approaches, in vitro models recapitulating the inflammatory and degenerative processes are of high interest for drug screening. IL-1β is one of the pivotal cytokines involved in both degradative and inflammatory pathway associated to OA progression47,48. In vitro, IL-1β triggers the production of inflammatory markers including NO and PGE2 and proteolytic enzymes such as MMP-13 by chondrocytes49. Since IL-1β is a major cytokine involved in OA pathogenesis, in vitro models of IL-1β-treated chondrocytes have been widely used to screen drugs or natural compounds in the field of OA treatment50. In this context, we first embarked on experiments aiming at testing the effects of HT/PCy extract on the IL-1β-induced levels of NO, PGE2 and MMP-13 in rabbit primary chondrocytes. This study strongly suggests that a combination of HT and PCy may be potent to inhibit the inflammatory and catabolic effects of IL-1β. Interestingly, our data have shown that HT/PCy mix was able to prevent the effects of IL-1β by not only affecting the expression levels of transcripts encoding for iNOS, COX2 and MMP13, but also by reducing their inflammatory and catabolic related products NO, PGE2 and MMP-13 respectively. These data are consistent with two other independent studies establishing the chondroprotective effect of HT and PCy alone in H2O2-induced iNOS, COX2, MMP13 expression in chondrocytes23,51. Despite their promising aspect, one major limitation of this in vitro first set of data could be related to the use of monolayer culture model. It is thus well acknowledged that monolayer cultured chondrocytes rapidly lose their differentiated phenotype36. It would therefore be possible that isolated chondrocytes do not respond like chondrocytes embedded within their physiological microenvironment. Nevertheless, numerous studies have been conducted on cartilage explants or chondron culture and have consistently shown that IL-1β treatment triggered the production of similar inflammatory and degradative markers as in monolayer chondrocytes including NO, PGE2 and MMP-1352,53.

Despite recent advances in our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying OA pathogenesis54, pharmacological treatments only alleviate inflammation and pain but do not address the clinically relevant issue of joint tissue degeneration. In addition, medication often causes side effects including adverse liver and gastrointestinal reactions. In the search of a well-tolerated and orally deliverable medication able to prevent or treat OA early in the degenerative cascade, animal models that recapitulate most of the different aspects of human OA are a prerequisite to clinical translation. In addition to aging, traumatic injury remains one of the major causes of OA in human55,56. This has led us get interest into animal models in which OA can be induced by a reliable surgical intervention inducing a clinically relevant joint trauma such as meniscal lesion or cruciate ligament rupture. Among the in vivo models of post-traumatic OA, mouse is often the first-in-line model for its cost-efficiency, ease to handle and the availability of molecular tools57. In this context, we first used a model of mid-stage OA induced by DMM in mice. By using this murine model, we have undoubtedly demonstrated that a HT/PCy supplemented diet prior to surgery was able to significantly decrease post-traumatic OA severity as evidenced by reduced OARSI score and aggrecan-related NITEGE degradation product.

Although murine models of post-traumatic OA are instrumental for the preliminary screening of drugs, its relatively modest size as compared to human raise some issues. Notably, mice cartilage is extremely thin and it makes difficult to discern different layers31,58. This reduced thickness constitutes also an obstacle to histologically assess small defects57. Facing these limitations, and to strengthen the scientific relevance of our work, we were then interested in testing whether HT/PCy could also have preventing properties in a larger animal model that recapitulate one of the most frequent human traumatic joint injuries, the rupture of anterior cruciate ligament. Among the large animal model available, rabbit knees present the advantage of being quite similar, at least in gross appearance, to those of human59. By using, such an ACLT-induced OA model in rabbit, we have confirmed the preventive effects of HT/PCy on the severity of post-traumatic OA as evidenced by reduced X-Ray and OARSI scores as well as NITEGE detection.

Apart from their role in assessing the efficacy of drugs, animal models are also used to address the drug safety. In the field of OA research, various animal models such as murine, rabbit, canine, ovine are used to assess nutraceutical potency. As a consequence, a large variety of polyphenol derivative doses has been evaluated ranging from 0.1 mg/kg/day to 6 g/kg/day22. All animal models are not equivalent in terms of physiological and biochemical (e.g. absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion) parameters. Consequently, the tested dose and the effects produced by the concentration may vary greatly between two animal species. In this context, inter-species dose extrapolation, only based on body size, is likely to be irrelevant60,61,62,63,64. For experimental purpose, selected safe and effective therapeutic dose is however required. Considering these parameters and in the context of a safety assay in mouse model, the effects of HT/PCy were tested at relatively high dose (i.e. 4 g/kg/day). Our study demonstrated that HT/PCy was well tolerated at such a high dose and prevents OA from worsening. Based on this first set of data generated in mice and aiming at demonstrating the effects of HT/PCy in pharmacological condition, the dose was adjusted for application in the rabbit model. Referring to metabolic body size adjustment formula outlined in literature, rabbits received HT/PCy mid-range doses of 100 mg/kg/day60,61,62,63,64, which are, according to metabolic body size, a 10 times lower dose than those given to mice. Despite this discrepancy and consistently with the results obtained in mice, we found that HT/PCy used at mid-range dose in rabbits has preventive effects on OA severity.

It is nowadays commonly accepted that OA is a heterogeneous disease described with five different phenotypes: post-traumatic, pain, ageing, metabolic and genetic4,65. In the light of these considerations, two different approaches could be considered. On the first hand, strategies that consist in targeting a specific OA phenotype could be implemented. On the other hand, a second approach that aims at developing treatments with broad spectra could also be contemplated. With respect to the promising ability of HT/PCy to counteract in vitro IL-1β-dependent inflammatory and catabolic events as well as OA severity in post-traumatic OA models, it could be interesting to further explore the anti-OA effects of HT/PCy mix in other OA models mimicking the human metabolic, ageing, pain and genetic phenotypes.

In the perspective of a transfer from bench to bedside, the bioavailability, i.e. ability to reach blood flow, of natural anti-osteoarthritic molecules after oral administration is a key pre-requisite. Surprisingly and despite a huge number of studies dealing with the anti-osteoarthritic properties of nutraceuticals66, no study has directly addressed the bioavailability of phenolic compound metabolites in the blood stream after ingestion. The systemic bioavailability depends on the various chemical modifications that compounds undergo after absorption from the intestine barrier (e.g. deglycosylation, glucuronate modification, and/or conjugation with sulfates) that lead to the formation of metabolites chemically different from the native compound67,68. The chemical modification can alter or inactivate biological activity of molecules. This was well illustrated by Yang et al., who reported that hesperitin, a metabolite of hesperidin (a polyphenol found in citrus fruits), contained in serum of hesperidin-fed rats, showed potent anti-inflammatory activity, whereas the native hesperidin molecule did not69. On the contrary, it cannot be excluded that the bioactivity of native molecule can be suppressed by metabolic modifications following ingestion. We therefore sought to determine whether the serum of rabbit fed with HT/PCy contains bioactive metabolites of phenolic compounds. To address this issue, two complementary methods have been used. The first direct method consists of identifying the presence of specific and already known metabolites of phenolic compounds by UPLC-MS in collected serum. Accordingly, the sera of rabbits force-fed with HT/PCy were found to contain 5 metabolites of HT and 9 of PCy. It would be of interest to assess HT/PCy bioavailability in synovial fluid after oral administration. Unfortunately, joint fluid volume in normal 15 week-old New Zealand white rabbits is unsatisfying to be collected and analyzed by UPLC-MS. The second indirect method consists of testing the biological activity of sera from rabbits force-fed with extracts. In this purpose, sera collected from rabbits force-fed with extracts were found to exhibit an anti-IL-1β effect in in vitro models of cultured chondrocytes. Of interest, our data clearly indicate that the sera of rabbits fed with HT/PCy extract significantly down-regulated the IL-1β-induced levels of NO, PGE2 and MMP-13. Considered together, these results strongly suggest that HT and PCy conserved their bioactivities in serum after undergoing digestive process in rabbit. It remains however difficult to totally rule out the possibility that HT/PCy oral intake may trigger the production of yet unidentified secondary mediators in sera that also have anti-IL-1β effect. No study, to our knowledge, has addressed this interesting assumption that should deserve further consideration.

To conclude, HT/PCy exerts in vitro anti-IL-1β effects in chondrocytes and significantly reduces the severity of post-traumatic OA in mice and rabbit models. The sera of rabbits force fed with HT/PCy was found to contain the regular digestive metabolites of polyphenols and to exhibit in vitro anti-IL-1β effects in chondrocytes thereby suggesting that HT/PCy are bioavailable and bioactive after oral intake.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Mével, E. et al. Olive and grape seed extract prevents post-traumatic osteoarthritis damages and exhibits in vitro anti-IL-1β activities before and after oral consumption. Sci. Rep. 6, 33527; doi: 10.1038/srep33527 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to B. Fellah, I. Leborgne, and P. Roy (CRIP- ONIRIS) who contributed to experiments using rabbits; S. Sourice (Inserm UMRS 791) for her advice with histological analysis; E. Hay (Inserm UMRS 1132) for his advice with NITEGE IHC; P.Pilet for his fruitful discussion for IHC intensity analysis; F. Berenbaum for his help in DMM mice model; UTE Platform (SFR François Bonamy, FED 4203/ Inserm UMS 016/CNRS 3556) who provided daily care to animals and specially P. Monmousseau who provided help with forced-fed rabbits; MS and NMR experiments were undertaken at the Metabolome Facility at the Functional Genomic Center in Bordeaux, France and specially E. Renouf for her assistance in UPLC-MS analysis. R Pace who provided help with manuscript. This study was supported by Grap’Sud, Région Languedoc Roussillon, the BPI and the ANRT.

Footnotes

Author Contributions E.M. collected data, performed the research, analyzed and interpreted data, study design and drafted the manuscript. C.M. contributed to collected data, analyzed and interpreted data, study design and gets critical revision of the article for important intellectual content. C.V. performed surgery in mice model. S.K. and T.R. participated in UPLC-MS data collection, analysis and provide help in drafting the manuscript. M.M. participated in data collection. J.L. participated in histological analysis. V.H. and J.A. contributed to radiographic or histological scoring. O.G. contributed to rabbits’ experiments and fruitful discussions. G.N. and X.H. provided help in mice model. Y.W. participated in study design for the in vivo studies. N.U. obtained funding and provided extracts. J.G. and L.B. participated in study design, data analysis and gets critical revision of the article for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- Nuesch E. et al. All cause and disease specific mortality in patients with knee or hip osteoarthritis: population based cohort study. BMJ 342, d1165 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leardini G. et al. Direct and indirect costs of osteoarthritis of the knee. Clin Exp Rheumatol 22, 699–706 (2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeser R. F., Goldring S. R., Scanzello C. R. & Goldring M. B. Osteoarthritis: a disease of the joint as an organ. Arthritis Rheum 64, 1697–1707 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijlsma J. W., Berenbaum F. & Lafeber F. P. Osteoarthritis: an update with relevance for clinical practice. Lancet 377, 2115–2126 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper C. et al. Risk factors for the incidence and progression of radiographic knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 43, 995–1000 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilak F. Biomechanical factors in osteoarthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 25, 815–823 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karsdal M. A. et al. Cartilage degradation is fully reversible in the presence of aggrecanase but not matrix metalloproteinase activity. Arthritis Res Ther 10, R63 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim N. H. et al. Reactive-site mutants of N-TIMP-3 that selectively inhibit ADAMTS-4 and ADAMTS-5: biological and structural implications. Biochem J 431, 113–122 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deberg M. et al. New serum biochemical markers (Coll 2-1 and Coll 2-1 NO2) for studying oxidative-related type II collagen network degradation in patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 13, 258–265 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudson C. B. & Knudson W. Cartilage proteoglycans. Semin Cell Dev Biol 12, 69–78 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little C. B. et al. Matrix metalloproteinase 13-deficient mice are resistant to osteoarthritic cartilage erosion but not chondrocyte hypertrophy or osteophyte development. Arthritis Rheum 60, 3723–3733 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clouet J. et al. From osteoarthritis treatments to future regenerative therapies for cartilage. Drug Discov Today 14, 913–925 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W. P. et al. Anti-arthritic effects of chlorogenic acid in interleukin-1beta-induced rabbit chondrocytes and a rabbit osteoarthritis model. Int Immunopharmacol 11, 23–28 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W. P., Hu P. F., Bao J. P. & Wu L. D. Morin exerts antiosteoarthritic properties: an in vitro and in vivo study. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 237, 380–386 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W. P. et al. Morin inhibits interleukin-1beta-induced nitric oxide and prostaglandin E2 production in human chondrocytes. Int Immunopharmacol 12, 447–452 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csaki C., Mobasheri A. & Shakibaei M. Synergistic chondroprotective effects of curcumin and resveratrol in human articular chondrocytes: inhibition of IL-1beta-induced NF-kappaB-mediated inflammation and apoptosis. Arthritis Res Ther 11, R165 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bang J. S. et al. Anti-inflammatory and antiarthritic effects of piperine in human interleukin 1beta-stimulated fibroblast-like synoviocytes and in rat arthritis models. Arthritis Res Ther 11, R49 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haseeb A., Chen D. & Haqqi T. M. Delphinidin inhibits IL-1beta-induced activation of NF-kappaB by modulating the phosphorylation of IRAK-1(Ser376) in human articular chondrocytes. Rheumatology (Oxford) 52, 998–1008 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Largo R. et al. Glucosamine inhibits IL-1beta-induced NFkappaB activation in human osteoarthritic chondrocytes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 11, 290–298 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Gao J. S., Chen J. W., Li F. & Tian J. Effect of resveratrol on cartilage protection and apoptosis inhibition in experimental osteoarthritis of rabbit. Rheumatol Int 32, 1541–1548 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phitak T. et al. Chondroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects of sesamin. Phytochemistry 80, 77–88 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mével E. et al. Nutraceuticals in joint health: animal models as instrumental tools. Drug Discov Today 19, 1649–1658 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aini H. et al. Procyanidin B3 prevents articular cartilage degeneration and heterotopic cartilage formation in a mouse surgical osteoarthritis model. PLoS One 7, e37728 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bascoul-Colombo C. et al. Glucosamine Hydrochloride but Not Chondroitin Sulfate Prevents Cartilage Degradation and Inflammation Induced by Interleukin-1alpha in Bovine Cartilage Explants. Cartilage 7, 70–81 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda R., Koike T., Taniguchi I. & Tanaka K. Double-blind placebo-controlled trial of hydroxytyrosol of Olea europaea on pain in gonarthrosis. Phytomedicine 20, 861–864 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packer L., Rimbach G. & Virgili F. Antioxidant activity and biologic properties of a procyanidin-rich extract from pine (Pinus maritima) bark, pycnogenol. Free Radic Biol Med 27, 704–724 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallares V. et al. Grape seed procyanidin extract reduces the endotoxic effects induced by lipopolysaccharide in rats. Free Radic Biol Med 60, 107–114 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W. G., Zhang X. Y., Wu Y. J. & Tian X. Anti-inflammatory effect and mechanism of proanthocyanidins from grape seeds. Acta Pharmacol Sin 22, 1117–1120 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L. et al. Modification of collagen with a natural cross-linker, procyanidin. Int J Biol Macromol 48, 354–359 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiraloche G. et al. Effect of oral glucosamine on cartilage degradation in a rabbit model of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 52, 1118–1128 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasson S. S., Chambers M. G., Van Den Berg W. B. & Little C. B. The OARSI histopathology initiative - recommendations for histological assessments of osteoarthritis in the mouse. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 18 Suppl 3, S17–S23 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritzker K. P. et al. Osteoarthritis cartilage histopathology: grading and staging. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 14, 13–29 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong D. J. et al. Green tea polyphenol treatment is chondroprotective, anti-inflammatory and palliative in a mouse post-traumatic osteoarthritis model. Arthritis Res Ther 16, 508 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- Kellgren J. H. & Lawrence J. S. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis 16, 494–502 (1957). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulocher C. B. et al. Radiographic assessment of the femorotibial joint of the CCLT rabbit experimental model of osteoarthritis. BMC Med Imaging 10, 3 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinatier C. et al. A silanized hydroxypropyl methylcellulose hydrogel for the three-dimensional culture of chondrocytes. Biomaterials 26, 6643–6651 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J. & Schmittgen T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louboutin H. et al. Osteoarthritis in patients with anterior cruciate ligament rupture: a review of risk factors. Knee 16, 239–244 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio L. et al. A new hydroxytyrosol metabolite identified in human plasma: hydroxytyrosol acetate sulphate. Food Chem 134, 1132–1136 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez M. et al. Improved method for identifying and quantifying olive oil phenolic compounds and their metabolites in human plasma by microelution solid-phase extraction plate and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 877, 4097–4106 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Torre-Carbot K. et al. Rapid high-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry method for qualitative and quantitative analysis of virgin olive oil phenolic metabolites in human low-density lipoproteins. J Chromatogr A 1116, 69–75 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arola-Arnal A. et al. Distribution of grape seed flavanols and their metabolites in pregnant rats and their fetuses. Mol Nutr Food Res 57, 1741–1752 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serra A., Macia A., Romero M. P., Pinol C. & Motilva M. J. Rapid methods to determine procyanidins, anthocyanins, theobromine and caffeine in rat tissues by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 879, 1519–1528 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateos-Martin M. L., Perez-Jimenez J., Fuguet E. & Torres J. L. Non-extractable proanthocyanidins from grapes are a source of bioavailable (epi)catechin and derived metabolites in rats. Br J Nutr 108, 290–297 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urpi-Sarda M. et al. Targeted metabolic profiling of phenolics in urine and plasma after regular consumption of cocoa by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A 1216, 7258–7267 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich K. M. & Neilson A. P. Simultaneous UPLC-MS/MS analysis of native catechins and procyanidins and their microbial metabolites in intestinal contents and tissues of male Wistar Furth inbred rats. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 958, 63–74 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldring M. B. The role of the chondrocyte in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 43, 1916–1926 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor M., Martel-Pelletier J., Lajeunesse D., Pelletier J. P. & Fahmi H. Role of proinflammatory cytokines in the pathophysiology of osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 7, 33–42 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. A. et al. The catabolic pathway mediated by Toll-like receptors in human osteoarthritic chondrocytes. Arthritis Rheum 54, 2152–2163 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csaki C., Keshishzadeh N., Fischer K. & Shakibaei M. Regulation of inflammation signalling by resveratrol in human chondrocytes in vitro. Biochem Pharmacol 75, 677–687 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Facchini A. et al. Hydroxytyrosol prevents increase of osteoarthritis markers in human chondrocytes treated with hydrogen peroxide or growth-related oncogene alpha. PLoS One 9, e109724 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathak N. N. et al. Anti-inflammatory and chondroprotective effects of atorvastatin in a cartilage explant model of osteoarthritis. Inflamm Res 64, 161–169 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G. M. et al. Development of selective tolerance to interleukin-1beta by human chondrocytes in vitro. J Cell Physiol 192, 113–124 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulet B. & Staines K. A. New developments in osteoarthritis and cartilage biology. Curr Opin Pharmacol 28, 8–13 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohmander L. S., Englund P. M., Dahl L. L. & Roos E. M. The long-term consequence of anterior cruciate ligament and meniscus injuries: osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med 35, 1756–1769 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dare D. & Rodeo S. Mechanisms of post-traumatic osteoarthritis after ACL injury. Curr Rheumatol Rep 16, 448 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory M. H. et al. A review of translational animal models for knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis 2012, 764621 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon W. H. Scale effects in animal joints. I. Articular cartilage thickness and compressive stress. Arthritis Rheum 13, 244–256 (1970). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laverty S., Girard C. A., Williams J. M., Hunziker E. B. & Pritzker K. P. The OARSI histopathology initiative - recommendations for histological assessments of osteoarthritis in the rabbit. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 18 Suppl 3, S53–S65 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White C. R. & Seymour R. S. Allometric scaling of mammalian metabolism. J Exp Biol 208, 1611–1619 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rucker R. B. Allometric scaling, metabolic body size and interspecies comparisons of basal nutritional requirements. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl) 91, 148–156 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rucker R. & Storms D. Interspecies comparisons of micronutrient requirements: metabolic vs. absolute body size. J Nutr 132, 2999–3000 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agutter P. S. & Tuszynski J. A. Analytic theories of allometric scaling. J Exp Biol 214, 1055–1062 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma V. & McNeill J. H. To scale or not to scale: the principles of dose extrapolation. British journal of pharmacology 157, 907–921 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckwalter J. A. & Martin J. A. Osteoarthritis. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 58, 150–167 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrotin Y., Lambert C., Couchourel D., Ripoll C. & Chiotelli E. Nutraceuticals: do they represent a new era in the management of osteoarthritis? - a narrative review from the lessons taken with five products. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 19, 1–21 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manach C., Scalbert A., Morand C., Remesy C. & Jimenez L. Polyphenols: food sources and bioavailability. Am J Clin Nutr 79, 727–747 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rein M. J. et al. Bioavailability of bioactive food compounds: a challenging journey to bioefficacy. Br J Clin Pharmacol 75, 588–602 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H. L. et al. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory potential of hesperetin metabolites obtained from hesperetin-administered rat serum: an ex vivo approach. J Agric Food Chem 60, 522–532 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.