Short Narrative Abstract

Cosmetics contain a vast number of chemicals, most of which are not under the regulatory purview of the Food and Drug Administration. Only a few of these chemicals have been evaluated for potential deleterious health impact – parabens, phthalates, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and siloxanes. A review of the ingredients in the best-selling and top rated products of the top beauty brands in the world, as well as a review of highlighted chemicals by non-profit environmental organizations reveal 11 chemicals and chemical families of concern: butylated hydroxyanisole/butylated hydroxytoluene, coal tar dyes, diethanolamine, formaldehyde releasing preservatives, parabens, phthalates, 1,4 dioxane, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, siloxanes, talc/asbestos, and triclosan. Age at menopause can be affected by a variety of mechanisms, including endocrine disruption, failure of DNA repair, oxidative stress, shortened telomere length, and ovarian toxicity. There is a lack of available studies to make a conclusion regarding cosmetics use and age at menopause. What little data there is suggests future studies are warranted. Women with chronic and consistent use of cosmetics across their lifespan may be a population of concern. More research is required to better elucidate the relationship and time windows of vulnerability and the effects of mixtures and combinations of products on ovarian health.

Keywords: Menopause, cosmetics, personal care products, ovarian aging, reproductive senescence

Introduction

Women are susceptible to the societal pressures of using cosmetics to beautify themselves (1–3). One theory behind the origins of the ♀ symbol used to denote “woman” is that it represents the hand mirror used by the Roman goddess Venus or the Greek goddess Aphrodite (4). In their efforts to look beautiful, both men and women apply cosmetics to hide their flaws and accentuate their features. Cosmetics have been a part of human history as far back as the ancient Egyptians (5). The ancient Egyptians, Romans, and Greeks used various ingredients to soften, improve, exfoliate, and detoxify skin (5). The ancient Romans and Greeks used walnut extracts as hair dye, antimony (a known toxic heavy metal) as eye shadow, white lead carbonate as a skin lightener, charcoal crocodile excrement as a skin darkener, and cinnabar as rouge (5).

This article will broadly address the question of “Cosmetics use and menopause, is there a connection?” The Oxford English Dictionary defines “cosmetics” as “A preparation intended to beautify the hair, skin, or complexion” (6). The word comes from the Greek word kosmetikos (“relating to adornment”), which is taken from the Greek word kosmein (“to arrange, adorn”), which itself is taken from the Greek word kosmos (“order, adornment”) (6). For the purposes of this review, we define cosmetics as any product applied to the skin to enhance and beautify, i.e. products often labeled as “makeup.” In 2014, the revenue of the cosmetic industry in the United States alone was 56.63 billion dollars (7), compared to the global oral contraceptive pills market which was valued at 5.236 billion that same year (8). Companies sell a broad spectrum of cosmetic items – each item containing a huge variety of chemicals that all contribute to the color, texture, patina (sheen vs. matte), odor, preservation, suspension, lubrication, thermal stability, and finishing texture of the cosmetic. Given the widespread and frequent personal use of cosmetics containing classes of compounds that are endocrine disrupters, it is of great importance for women and health care providers to understand the potential harm that ingredients in cosmetics can have on women’s reproductive health and reproductive aging. In a survey administered to pregnancy planners and pregnant women regarding risk perception of cosmetic use, out of 128 respondents (68 of whom were pregnant), 39.5% felt that cosmetics outside of pregnancy were “fairly safe” and 37.7% felt that cosmetics were “not really safe” (9). Despite this fairly high level of concern, most women did not intend to/had not changed their cosmetics use during pregnancy (9).

The Role of the FDA in Cosmetics

While the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) monitors the chemicals that go into foods, drugs, and medical devices closely, cosmetics are not subjected to similar scrutiny. The FDA does not have to approve any cosmetics that go on the market unless the product claims to treat or prevent disease or alter the body in any way (in which case the product is classified as a drug) (10). There are only 11 chemicals that are outright prohibited or restricted for use in cosmetics (bithionol, chlorofluorocarbon propellants, chloroform, halogenated salicylanilides, hexachlorophene, mercury compounds, methylene chloride, cattle materials, sunscreens, vinyl chloride, and zirconium-containing complexes) (11). Of note, color additives must be approved by the FDA before use in any cosmetics (12). The exception to this rule is color additives derived from mineral, plant or animal sources, or additives derived from coal tar or petroleum (12). However, coal tar dyes, especially para-phenylenediamine, have been linked to DNA damage (13–15). This paper describes the chemicals that cosmetics contain and discusses the few studies that address how these chemicals can potentially affect human physiology, especially in relation to menopause.

Methods

Selection of cosmetics and their ingredients

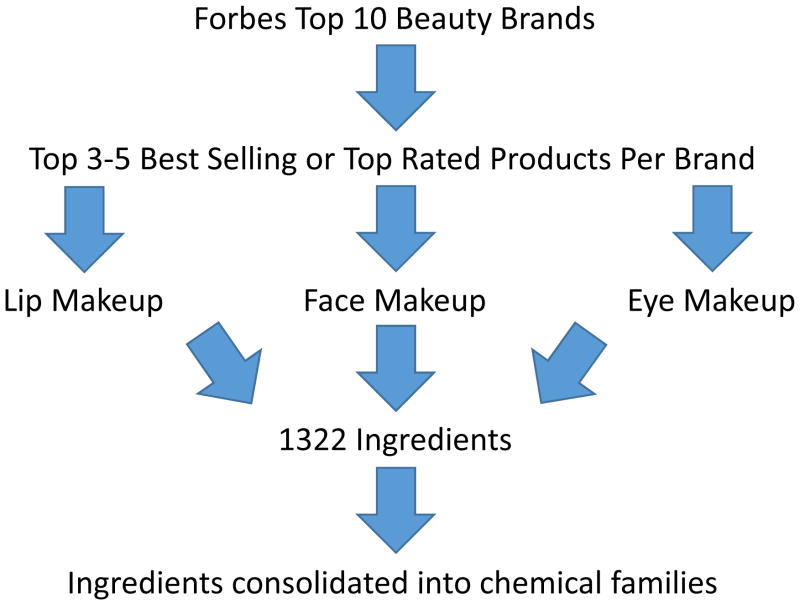

Due to the vast number of chemical ingredients in cosmetics, we devised the following methodology to identify chemicals for which to conduct our literature review (see Figure 1). Once these chemicals were identified, we generated a word cloud to visualize the frequency of chemicals and undertook a literature review. To summarize our identification methodology, we began by using the Forbes list of top 10 global beauty brands in 2012 (16). We did not use the top grossing global beauty companies because many companies own several brands. From the top ten beauty brand list, we went to the websites of the top five. These brands are denoted by symbolic letters: X, A, B, C, and D (in order from largest to smallest global brand revenue) (16). On each site, we looked at lip makeup, face makeup, and eye makeup products of each company and extracted the ingredient list of the top 3–5 best-selling or top rated products in each category, depending on the company (see Table 1 for a complete list of the products assessed in this paper). Brands X and D only carry skin care products and not makeup, so they are not included in the table.

Figure 1.

Path of determination for what ingredients are commonly found in beauty products

Table 1.

Complete list of products examined for major ingredients in cosmetics used in word cloud

| Brand | A | B | C | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Face | Lip | Eye | Face | Lip | Eye | Face | Lip | Eye |

| Product | Smooth Minerals Blush | Ultra Luxury Lip Liner | Glimmersticks Brow Definer | Visible Lift Blur Concealer | Colour Riche Lipcolour | Studio Secrets Professional Eye Shadow Duos | Shine Control Liquid Makeup | MoistureShine Gloss | Nourishing Long Wear Eye Shadow + Built-in Primer |

| Smooth Minerals Powder Foundation | Mark. Gloss Gorgeous Stay On Lip Stain | Glimmersticks Eye Liner | Infallible Pro-Matte Foundation | Colour Riche La Lacque Lip Pen | Brow Stylist Plumper | Shine Control Primer | Revitalizing Lip Balm SPF 20 | Nourishing Eye Liner | |

| Invisible Coverage Liquid Foundation | Mark. Lipstick Full Color Lipstick | Ultra Luxury Brow Liner | True Match Concealer | Infallible Pro-Matte Gloss | Infallible 24 Hr Eye Shadow | SkinClearing Mineral Powder | MoistureSmooth Color Stick | Healthy Lengths Mascara | |

| Ideal Flawless Invisible Coverage Cream-to-Powder Foundation | Ultra Luxury Eye Liner | Infallible Pro-Matte Powder | Colour Riche Collection Exclusive Red Lipcolor | HiP High Intensity pigments Matte Shadow Duos | Mineral Sheers Loose Powder Foundation | MoistureShine Lip Soother SPF 20 | Healthy Skin Brightening Eye Perfector Broad Spectrum SPF 25 | ||

| Ideal Luminous Blush | SuperShock Mascara in Black | Infallible Pro Contour Palette | Infallible Matte-Matic Liner | Nourishing Long Wear Liquid Makeup Broad Spectrum SPF 20 | Healthy Volume Mascara Regular | ||||

Definitions

We defined face makeup as any product that is applied to the skin for enhancing purposes. Eye makeup encompassed any makeup that is applied near the eye, including eye liners, mascaras, eye shadows, and brow liners. Lip makeup is any lip color or shape enhancing makeup, therefore not including lip balms.

Chemical families and their ingredients

Since several ingredients are in the same chemical family but have different names, we simplified the list of ingredients by replacing some with their chemical family name (e.g. paraben in place of methylparaben and ethylparaben) in order to better isolate which chemical families most commonly appear in the ingredients. Table 2 shows the ingredients and their associated chemical family names. Since different companies named some ingredients differently (e.g. “safflower seed oil” vs. “carthamus tinctorius [safflower] seed oil”), we also standardized the names, but we did not include the standardizations in Table 2. The simplified ingredient list was then inserted into a word cloud generator to visualize which chemical families appeared the most abundant (Figure 2). There are two algorithms used in word cloud generation – one is a direct correlate of the count data and the other is a log function of the count. We used the direct correlation to best represent what cosmetic users may be most concerned about. From the word cloud, it was immediately apparent that coal tar dyes, siloxanes, and parabens were the most frequent chemical exposures from cosmetics application. The iron oxides and titanium dioxide color dyes did appear with much frequency, but as they are inorganic compounds that have little dermal penetration we did not include them in our literature search (17). One thousand three hundred twenty-two ingredients were compiled for the word cloud. Of the 1322 ingredients, we consolidated chemicals into 9 chemical families. Of the three largest chemical families, 145 ingredients were classified into the family of coal tar dyes, 95 into siloxanes, and 39 into parabens. Of the remaining 1043 individual chemicals we identified that could not be consolidated into chemical families, we cross-referenced our list of chemicals with websites detailing chemicals of concern. From that, we identified an additional 12 chemicals to assess for ovarian toxicity and age at menopause.

Table 2. Chemicals assigned to a chemical family for the word cloud.

All ingredients were taken from the ingredients list of the products mentioned in Table 1. Chemicals that were part of the same family were replaced with the family name (e.g. Blue 1/CI 42090 is a coal tar dye and was replaced with “coal tar dye” for the word cloud), being sure to preserve frequency of appearance for each ingredient.

| Label Used | Replaced Names |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Alpha hydroxy acid | Citric acid |

| Lactic acid | |

|

| |

| Beta hydroxyl acid | Salicylic acid |

|

| |

| Coal tar dye | Blue 1/CI 42090 |

| Blue 1 Lake/CI 42090 | |

| Brown 1/CI 20170 | |

| Green 5/CI 61570 | |

| Green 6/CI 61565 | |

| Orange 4/CI 15510 | |

| Orange 5/CI 45370 | |

| Orange 5 Lake/CI 45370 | |

| Red 4/CI 14700 | |

| Red 7/CI 15850 | |

| Red 7 Lake/CI 15850 | |

| Red 6/CI 15850 | |

| Red 6 Lake/CI 15850 | |

| Red 17/CI 26100 | |

| Red 21/CI 45380 | |

| Red 21 Lake/CI 45380 | |

| Red 22/CI 45380 | |

| Red 22 Lake/CI 45380 | |

| Red 30/CI 73360 | |

| Red 33/CI 17200 | |

| Red 33 Lake/CI 17200 | |

| Red 34/CI 15880 | |

| Red 34 Lake/CI 15880 | |

| Red 36/CI 12085 | |

| Red 36 Lake/CI 12085 | |

| Red 40/CI 16035 | |

| Red 40 Lake/CI 16035 | |

| Violet 2/CI 60725 | |

| Ext. Violet 2/CI 60730 | |

| Yellow 5/CI 19140 | |

| Yellow 5 Lake/CI 19140 | |

| Yellow 7/CI 45350 | |

| Ext. Yellow 7/CI 10316 | |

| Yellow 8/CI 45350 | |

| Yellow 10/CI 47005 | |

| Yellow 10 Lake/CI 47005 | |

|

| |

| Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) | Disodium EDTA |

| Tetrasodium EDTA | |

| Trisodium EDTA | |

|

| |

| Paraben | Butylparaben |

| Ethylparaben | |

| Isobutylparaben | |

| Isopropylparaben | |

| Methylparaben | |

| Propylparaben | |

|

| |

| Phthalate | Polyethylene terephthalate |

| Terephthalate | |

|

| |

| Polyethylene glycol (PEG) | PEG-6 beeswax |

| PEG-9 | |

| PEG-40 stearate | |

|

| |

| Pyroglutamic acid (PCA) | Calcium PCA |

| Lauryl PCA | |

| Sodium PCA | |

| Zinc PCA | |

|

| |

| Siloxane | Bis-PEG / PPG-14 / 14 dimethicone |

| Bis-PEG-12 / dimethicone beeswax | |

| C30–45 alkyl ceteayl dimethicone crosspolymer | |

| Caprylyl trimethicone | |

| Cetearyl dimethicone crosspolymer | |

| Cetyl dimethicone | |

| Cetyl PEG / PPG-10 / 1 dimethicone | |

| Cyclohexasiloxane | |

| Cyclopentasiloxane | |

| Methicone | |

| Dimethicone | |

| Dimethicone crosspolymer | |

| Dimethicone / PEG-10 / 15 crosspolymer | |

| Dimethicone / Vinyl dimethicone crosspolymer | |

| Diphenyl dimethicone | |

| Ethyl trisiloxane | |

| Hexamethyldisiloxane / Disiloxane | |

| Lauryl PEG-9 polydimethylsiloxyethyl dimethicone | |

| Methyl trimethicone | |

| Nylon-611 / Dimethicone copolymer | |

| PEG / PPG-18 / 18 dimethicone | |

| PEG / PPG-20 / 23 dimethicone | |

| PEG-9 polydimethylsiloxyethyl dimethicone | |

| PEG-10 dimethicone | |

| Phenyl trimethicone | |

| Steardimonium hydroxypropyl panthenyl PEG-7 dimethicone phosphate chloride | |

| Stearoxymethicone / Dimethicone copolymer | |

| Stearyl dimethicone | |

| Trimethylsiloxyphenyl dimethicone | |

| Vinyl dimethicone / Methicone silsequioxane crosspolymer | |

|

| |

| Chemicals of concern that do not appear in the word cloud | Beta hydroxyl acid |

| Sodium laureth sulfate | |

|

| |

| Chemical families commonly found in cosmetics not found in the products in Table 1 | Butylated hydroxyanisole |

| Triclosan | |

Figure 2.

Word cloud of ingredients most commonly found in the top selling/best rated products of Brands A, B, and C listed in Table 1

Chemicals of concern

In order to determine if there were any remaining chemicals that were not identified through the methods above in our definition of makeup, we turned to the David Suzuki Foundation (a Canadian environmental non-profit organization; www.davidsuzuki.org) and the cosmetics branch of the FDA (www.fda.gov/Cosmetics). In 2010, the David Suzuki Foundation investigated a list of “dirty dozen” cosmetics ingredients that contained butylated hydroxyanisole/butylated hydroxytoluene, coal tar dyes, diethanolamine compounds, dibutyl phthalate, formaldehyde-releasing preservatives, parabens, parfum, polyethylene glycol compounds, petrolatum, siloxanes, sodium laureth sulfate, and triclosan (18). The FDA website highlights certain additional cosmetic ingredients, which are alpha hydroxy acids, beta hydroxy acids, phthalates, and talc (19). However, beta hydroxy acids were an infrequent ingredient and did not appear in the word cloud. Based on our inclusion criteria for the word cloud, some other ingredients did not appear in the word cloud: diethanolamine (only triethanolamine appeared in the ingredients; the ethanolamine compounds are mostly used in moisturizers or shampoos/soaps which were not included in this review), butylated hydroxyanisole (mostly used in lipsticks and eye shadow but did not appear as an ingredient in any of the products we assessed), sodium laureth sulfate (infrequent in cosmetics – it is mostly used in shampoos/soaps which were not included in this paper), and triclosan (mostly used in personal hygiene and deodorant products which were not included in this paper). After identification of the final list, Pubmed was used to conduct a literature review with the chemical of interest and the following other search terms: “menopause,” “reproductive senescence,” and “ovarian failure.” To assess the toxicity and endocrine disruption of each chemical, we used The US National Library of Medicine’s Toxicology Data Network (http://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/), Cosmetic Ingredient Review’s safety assessment reports (http://www.cir-safety.org/ingredients), The Endocrine Disruption Exchange’s List of Potential Endocrine Disruptors (http://endocrinedisruption.org/endocrine-disruption/tedx-list-of-potential-endocrine-disruptors/), and Pubmed searches for the chemical of interest and the following other search terms: “genotox*,” “carcino*,” “endocrine,” “estrogen,” and “androgen.”

Table 3 (“Summary of chemicals in chemical families and potential harmful mechanisms”) is a compilation of all of these chemicals, along with their primary use and their known toxicity to the human body (some ingredients have not been shown to be toxic to humans, but for the sake of completion we have listed all ingredients as well as all known information about relevant toxicity). We will focus on those chemicals that have relevant toxicities to humans.

Table 3. Summary of chemicals in chemical families and potential harmful mechanisms.

Many of these chemical ingredients have varying routes of exposure and toxicities (e.g. oral, inhalation, dermal) reported by various databases and studies. Representative chemicals from each family will be reviewed, and only information relevant to our topic will be reported in this chart.

| Name Primary Use of Ingredient |

Endocrine Receptor Mechanisms | Other Nuclear Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|

|

Alpha hydroxy acids (used glycolic acid as a representative) Skin plasticizer (1) |

None found (1–3) | None found (1, 2) |

|

Beta hydroxy acids (used salicylic acid as a representative) Exfoliant (4) |

None found (2, 3, 5) | None found (2, 5) |

|

Butylated hydroxyanisole/butylated hydroxytoluene Cosmetic preservative (6) |

Butylated hydroxyanisole | |

| Reduces binding of estradiol to its receptor (7, 8), increases estrogen receptor transcription and binds estrogen receptor (8–11), and antagonizes dihydrotestosterone activation of androgen receptor (12) | Possibly carcinogenic in humans due to extensive evidence of carcinogenicity in animals (2) Evidence of gene toxicity in in vivo studies (2) |

|

| Butylated hydroxytoluene | ||

| Even more weakly anti-estrogenic and estrogenic effects than butylated hydroxyanisole (8) | None found (2, 13) | |

|

Coal tar dyes (used para- phenylenediamine as a representative)* Color dye (6) |

None found (2, 3, 14) | Not carcinogenic (14) Evidence of genotoxicity via oxidative stress and suppression of antioxidant activity (15–18) |

|

Diethanolamine compounds (used diethanolamine as a representative)** Emulsifier, foaming agent, pH adjuster (4) |

Anti-estrogenic and anti-androgenic (mechanism unknown) (19, 20) | Possibly carcinogenic in humans due to extensive evidence of carcinogenicity in animals (2) Not genotoxic (21) |

|

Formaldehyde releasing preservatives (toxicity search used “formaldehyde”) Slowly release formaldehyde over time (6). Formaldehyde is a cosmetic biocide and preservative (22). |

None found (2, 3, 22) | Known human carcinogen (23, 24) Evidence of genotoxicity via direct evidence of DNA damage in humans and oxidative stress particularly in ovaries (25–27) |

|

Parabens (used methylparaben as a representative) Cosmetic preservative (4) |

Inhibits testosterone-induced transcriptional activity (28) and interacts with estrogen receptor and increases expression of estrogen regulated genes (29, 30). | None found (31) |

|

Parfum/fragrance

*** Cosmetic fragrance |

See note | |

|

Phthalates (used diethylphthalate as a representative)

**** Fixative in fragrances and solvent (4) |

Different based on compound structure (32). Proposed mechanism of estrogenicity of DEP - binds and transactivates ERα receptors (33, 34). Evidence of anti-androgenicity as well but mechanism unknown (35). |

None found (36) |

|

Polyethylene glycol compounds

† Used as a cream base, increases permeability of skin to cosmetics (6) |

See note | |

|

Petrolatum

‡ Locks moisture into skin (6) |

Antagonistic activity at androgen receptors (37, 38) and interacts with estrogen receptor and upregulates transcription of ERβ (39, 40) | Known human carcinogen (41, 42) Evidence of genotoxicity via differing mechanisms depending on the specific polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon and specific target tissue (43–45) |

|

Siloxanes (used cyclotetrasiloxane as a representative) Softens, smooths, and moistens cosmetics (6) |

Weakly estrogenic (binds ERα receptors) (46–49) and evidence of anti-androgenicity but mechanism unknown (46) | Limited evidence for carcinogenicity in rats (50) Not genotoxic (51) |

|

Sodium laureth sulfate

† Cleansing and foaming agent (6) |

None found (2, 3, 52) | Not carcinogenic (2, 52) |

|

Talc

§ Many uses, e.g. absorbs moisture, prevents caking, and increases opacity (4) |

See note | |

|

Triclosan Preservative and anti-bacterial agent (6) |

Inhibits testosterone-induced transcriptional activity (28), enhances androgen-induced transcriptional activity (35), and decreases E2-dependent reporter gene expression, inhibits estradiol and estrogen sulfotransferase activity (53, 54) | Evidence of carcinogenicity in mice but likely not in humans (2, 55) Not genotoxic (2, 55) |

Coal tar dyes are so named because the dyes were traditionally made with processed coal tar. Most companies have made the switch over to synthesizing these colors from petroleum, but consumers have no way of knowing how the dye used in the cosmetics was synthesized, and using petroleum has its own hazards (See Petrolatum).

Another major concern of ethanolamine compounds is their ability to react with nitrites and form carcinogenic nitrosamines (21, 56). Nitrites can come from degradation of some cosmetic preservatives when they are exposed to air (57) and nitrites are sometimes used in cosmetics as anti-corrosive ingredients (58).

Parfum/fragrance is created by cosmetic companies out of many different ingredients. Beauty companies are not required to list the exact ingredients in each product and can just list fragrance or flavor ingredients as “fragrance” or “flavor” (4). Out of the top five companies we examined, only Olay makes available a complete list of all components they use for fragrance across all of their products (59), and there are around 3,000 chemicals that can be used as fragrances (6). A glance at the list reveals that parfum can be composed of a huge variety of chemicals which are unregulated, as well as diethyl phthalate, which is a phthalate commonly used in fragrances (4). Due to the sheer number of chemicals that can act as fragrance components, it is impossible to examine their individual toxicities.

While there is a lot of evidence that exposure to phthalates causes a variety of health issues, those toxic effects are seen in longer-chain phthalates. The three most common phthalates use in cosmetics are dibutyl phthalate (DBP; as a plasticizer for nail polish to prevent cracking), dimethyl phthalate (DMP; as a plasticizer for hair spray to avoid stiffness), and diethyl phthalate (DEP; as a solvent and fixative in fragrances) (4). In 2010, the FDA conducted a study measuring phthalate levels in various cosmetics and found that DBP and DMP are not used as often anymore, and DEP is the only remaining phthalate that can be found in significant concentrations in cosmetics (4). Regardless, these three phthalates are not considered longer chain phthalates and therefore have fewer associated health risks.

The major concern of these chemicals is that depending on how the compound is manufactured, it can be contaminated with 1,4-dioxane (55, 60). Consumers have no way of knowing if the ingredients in their cosmetics are 1,4-dioxane free, and the Organic Consumers Association commissioned a study in 2008 that found 1,4-dioxane in a significant percentage of the organic products analyzed (61). 1,4-dioxane has been shown to be carcinogenic in animals (62).

The major concern of petrolatum is that incompletely refined petrolatum can be contaminated by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) (2). The toxicity data presented here for petrolatum will therefore be for PAHs.

The major concern of talc in cosmetics is that talc is a naturally occurring mineral that is mined from the earth, and some talc mining sites are contaminated by asbestos, which is a closely related naturally occurring mineral with a different crystal structure (4). Cosmetics companies are now careful about selecting talc mining sites, and the FDA did a study in 2009–2010 to detect asbestos from different suppliers of several cosmetic-grade raw talc as well as cosmetic products containing talc and found no detectable levels of asbestos in any of the samples (4).

Fiume MZ. Final report on the safety assessment of glycolic acid, ammonium, calcium, potassium, and sodium glycolates, methyl, ethyl, propyl, and butyl glycolates, and lactic acid, ammonium, calcium, potassium, sodium, and tea-lactates, methyl, ethyl, isopropyl, and butyl lactates, and lauryl, myristyl, and cetyl lactates. International Journal of Toxicology. 1998;17(Supplement 1):234.

Toxicology Data Network [database on the Internet]. National Institutes of Health, Health & Human Services. 2014 [cited 4/15/2016]. Available from: http://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/.

TEDX List of Potential Endocrine Disruptors [database on the Internet]. The Endocrine Disruption Exchange, Inc. 2015 [cited 4/15/2016]. Available from: http://endocrinedisruption.org/endocrine-disruption/tedx-list-of-potential-endocrine-disruptors/overview.

Blum A, Balan SA, Scheringer M, Trier X, Goldenman G, Cousins IT, et al. The Madrid Statement on Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs). Environ Health Perspect. 2015 May;123(5):A107–11.

Fiume MZ. Safety assessment of salicylic acid, butyloctyl salicylate, calcium salicylate, C12–15 alkyl salicylate, capryloyl salicylic acid, hexyldodecyl salicylate, isocetyl salicylate, isodecyl salicylate, magnesium salicylate, MEA-salicylate, ethylhexyl salicylate, potassium salicylate, methyl salicylate, myristyl salicylate, sodium salicylate, TEA-salicylate, and tridecyl salicylate. International Journal of Toxicology. 2003;22(Supplement 3):108.

The “Dirty Dozen” Ingredients Investigated in the David Suzuki Foundation Survey of Chemicals in Cosmetics. David Suzuki Foundation, 2010.

Kang HG, Jeong SH, Cho JH, Kim DG, Park JM, Cho MH. Evaluation of estrogenic and androgenic activity of butylated hydroxyanisole in immature female and castrated rats. Toxicology. 2005 Sep 15;213(1–2):147–56.

Jobling S, Reynolds T, White R, Parker MG, Sumpter JP. A variety of environmentally persistent chemicals, including some phthalate plasticizers, are weakly estrogenic. Environ Health Perspect. 1995 Jun;103(6):582–7.

Soto AM, Sonnenschein C, Chung KL, Fernandez MF, Olea N, Serrano FO. The E-SCREEN assay as a tool to identify estrogens: an update on estrogenic environmental pollutants. Environ Health Perspect. 1995 Oct;103 Suppl 7:113–22.

ter Veld MG, Schouten B, Louisse J, van Es DS, van der Saag PT, Rietjens IM, et al. Estrogenic potency of food-packaging-associated plasticizers and antioxidants as detected in ERalpha and ERbeta reporter gene cell lines. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry. 2006 Jun 14;54(12):4407–16.

Amadasi A, Mozzarelli A, Meda C, Maggi A, Cozzini P. Identification of xenoestrogens in food additives by an integrated in silico and in vitro approach. Chem Res Toxicol. 2009 Jan;22(1):52–63.

Schrader TJ, Cooke GM. Examination of selected food additives and organochlorine food contaminants for androgenic activity in vitro. Toxicol Sci. 2000 Feb;53(2):278–88.

Lanigan RS, Yamarik TA. Final report on the safety assessment of BHT(1). Int J Toxicol. 2002;21 Suppl 2:19–94.

Johnson W, Jr. Amended Final Report of the Safety Assessment of p-Phenylenediamine, p-Phenylenediamine HCl, and p-Phenylenediamine Sulfate. Washington, DC: Cosmetic Ingredient Review, 2007.

Reena K, Ng KY, Koh RY, Gnanajothy P, Chye SM. para-Phenylenediamine induces apoptosis through activation of reactive oxygen species-mediated mitochondrial pathway, and inhibition of the NF-kappaB, mTOR, and Wnt pathways in human urothelial cells. Environmental toxicology. 2016 Jan 19.

Zanoni TB, Hudari F, Munnia A, Peluso M, Godschalk RW, Zanoni MV, et al. The oxidation of p-phenylenediamine, an ingredient used for permanent hair dyeing purposes, leads to the formation of hydroxyl radicals: Oxidative stress and DNA damage in human immortalized keratinocytes. Toxicol Lett. 2015 Dec 15;239(3):194–204.

Anundi I, Hogberg J, Stead AH. Glutathione depletion in isolated hepatocytes: its relation to lipid peroxidation and cell damage. Acta Pharmacol Toxicol (Copenh). 1979 Jul;45(1):45–51.

Picardo M, Zompetta C, Grandinetti M, Ameglio F, Santucci B, Faggioni A, et al. Paraphenylene diamine, a contact allergen, induces oxidative stress in normal human keratinocytes in culture. Br J Dermatol. 1996 Apr;134(4):681–5.

Kassotis CD, Klemp KC, Vu DC, Lin CH, Meng CX, Besch-Williford CL, et al. Endocrine-Disrupting Activity of Hydraulic Fracturing Chemicals and Adverse Health Outcomes After Prenatal Exposure in Male Mice. Endocrinology. 2015 Dec;156(12):4458–73.

Kassotis CD, Tillitt DE, Davis JW, Hormann AM, Nagel SC. Estrogen and androgen receptor activities of hydraulic fracturing chemicals and surface and ground water in a drilling-dense region. Endocrinology. 2014 Mar;155(3):897–907.

Fiume MM, Heldreth B. Amended Final Safety Assessment of Diethanolamine and its Salts as Used in Cosmetics. Washington, DC: Cosmetic Ingredient Review, 2011.

Boyer IJ, Heldreth B, Bergfeld WF, Belsito DV, Hill RA, Klaassen CD, et al. Amended safety assessment of formaldehyde and methylene glycol as used in cosmetics. Int J Toxicol. 2013 Nov–Dec;32(6 Suppl):5S–32S.

Baan R, Grosse Y, Straif K, Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, Bouvard V, et al. A review of human carcinogens--Part F: chemical agents and related occupations. Lancet Oncol. 2009 Dec;10(12):1143–4.

Formaldehyde, 2-Butoxyethanol and 1-tert-Butoxypropan-2-ol. Lyon, France: World Health Organization, 2006.

Ozen OA, Akpolat N, Songur A, Kus I, Zararsiz I, Ozacmak VH, et al. Effect of formaldehyde inhalation on Hsp70 in seminiferous tubules of rat testes: an immunohistochemical study. Toxicol Ind Health. 2005 Nov;21(10):249–54.

Peteffi GP, Antunes MV, Carrer C, Valandro ET, Santos S, Glaeser J, et al. Environmental and biological monitoring of occupational formaldehyde exposure resulting from the use of products for hair straightening. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2016 Jan;23(1):908–17.

Wang HX, Wang XY, Zhou DX, Zheng LR, Zhang J, Huo YW, et al. Effects of low-dose, long-term formaldehyde exposure on the structure and functions of the ovary in rats. Toxicol Ind Health. 2013 Aug;29(7):609–15.

Chen J, Ahn KC, Gee NA, Gee SJ, Hammock BD, Lasley BL. Antiandrogenic properties of parabens and other phenolic containing small molecules in personal care products. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007 Jun 15;221(3):278–84.

Routledge EJ, Parker J, Odum J, Ashby J, Sumpter JP. Some alkyl hydroxy benzoate preservatives (parabens) are estrogenic. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1998 Nov;153(1):12–9.

Byford JR, Shaw LE, Drew MG, Pope GS, Sauer MJ, Darbre PD. Oestrogenic activity of parabens in MCF7 human breast cancer cells. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology. 2002 Jan;80(1):49–60.

Panel CIRE. Final Amended Report on the Safety Assessment of Methylparaben, Ethylparaben, Propylparaben, Isopropylparaben, Butylparaben, Isobutylparaben, and Benzylparaben as used in Cosmetic Products. International Journal of Toxicology. 2008;27(Supplement 4):1–82.

Parveen M, Inoue A, Ise R, Tanji M, Kiyama R. Evaluation of estrogenic activity of phthalate esters by gene expression profiling using a focused microarray (EstrArray). Environ Toxicol Chem. 2008 Jun;27(6):1416–25.

Harris CA, Henttu P, Parker MG, Sumpter JP. The estrogenic activity of phthalate esters in vitro. Environ Health Perspect. 1997 Aug;105(8):802–11.

Kumar N, Sharan S, Srivastava S, Roy P. Assessment of estrogenic potential of diethyl phthalate in female reproductive system involving both genomic and non-genomic actions. Reproductive toxicology. 2014 Nov;49:12–26.

Christen V, Crettaz P, Oberli-Schrammli A, Fent K. Some flame retardants and the antimicrobials triclosan and triclocarban enhance the androgenic activity in vitro. Chemosphere. 2010 Nov;81(10):1245–52.

Panel CIRE. Annual Review of Cosmetic Ingredient Safety Assessments - 2002/2003. International Journal of Toxicology. 2005;24(Supplement1):1–102.

Vinggaard AM, Hnida C, Larsen JC. Environmental polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons affect androgen receptor activation in vitro. Toxicology. 2000 Apr 14;145(2–3):173–83.

Hawliczek A, Nota B, Cenijn P, Kamstra J, Pieterse B, Winter R, et al. Developmental toxicity and endocrine disrupting potency of 4-azapyrene, benzo[b]fluorene and retene in the zebrafish Danio rerio. Reproductive toxicology. 2012 Apr;33(2):213–23.

Li F, Wu H, Li L, Li X, Zhao J, Peijnenburg WJ. Docking and QSAR study on the binding interactions between polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and estrogen receptor. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2012 Jun;80:273–9.

Sievers CK, Shanle EK, Bradfield CA, Xu W. Differential action of monohydroxylated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons with estrogen receptors alpha and beta. Toxicol Sci. 2013 Apr;132(2):359–67.

Flesher JW, Lehner AF. Structure, function and carcinogenicity of metabolites of methylated and non-methylated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: a comprehensive review. Toxicology mechanisms and methods. 2016 Mar;26(3):151–79.

White AJ, Bradshaw PT, Herring AH, Teitelbaum SL, Beyea J, Stellman SD, et al. Exposure to multiple sources of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and breast cancer incidence. Environ Int. 2016 Apr–May;89–90:185–92.

Labib S, Williams A, Guo CH, Leingartner K, Arlt VM, Schmeiser HH, et al. Comparative transcriptomic analyses to scrutinize the assumption that genotoxic PAHs exert effects via a common mode of action. Arch Toxicol. 2015 Sep 16.

Long AS, Lemieux CL, Arlt VM, White PA. Tissue-specific in vivo genetic toxicity of nine polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons assessed using the MutaMouse transgenic rodent assay. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2016 Jan 1;290:31–42.

Einaudi L, Courbiere B, Tassistro V, Prevot C, Sari-Minodier I, Orsiere T, et al. In vivo exposure to benzo(a)pyrene induces significant DNA damage in mouse oocytes and cumulus cells. Hum Reprod. 2014 Mar;29(3):548–54.

McKim JM, Jr., Wilga PC, Breslin WJ, Plotzke KP, Gallavan RH, Meeks RG. Potential estrogenic and antiestrogenic activity of the cyclic siloxane octamethylcyclotetrasiloxane (D4) and the linear siloxane hexamethyldisiloxane (HMDS) in immature rats using the uterotrophic assay. Toxicol Sci. 2001 Sep;63(1):37–46.

Quinn AL, Dalu A, Meeker LS, Jean PA, Meeks RG, Crissman JW, et al. Effects of octamethylcyclotetrasiloxane (D4) on the luteinizing hormone (LH) surge and levels of various reproductive hormones in female Sprague-Dawley rats. Reproductive toxicology. 2007 Jun;23(4):532–40.

He B, Rhodes-Brower S, Miller MR, Munson AE, Germolec DR, Walker VR, et al. Octamethylcyclotetrasiloxane exhibits estrogenic activity in mice via ERalpha. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2003 Nov 1;192(3):254–61.

Quinn AL, Regan JM, Tobin JM, Marinik BJ, McMahon JM, McNett DA, et al. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of the estrogenic, androgenic, and progestagenic potential of two cyclic siloxanes. Toxicol Sci. 2007 Mar;96(1):145–53.

Lee M. 24-month combined chronic toxicity and oncogenicity whole body vapor inhalation study of octamethylcyclotetrasiloxane (D4) in Fischer 344 rats. Unpublished data submitted by Silicones Environmental, Health and Safety Council of North America. 2004:4801.

Johnson W, Jr., Bergfeld WF, Belsito DV, Hill RA, Klaassen CD, Liebler DC, et al. Safety assessment of cyclomethicone, cyclotetrasiloxane, cyclopentasiloxane, cyclohexasiloxane, and cycloheptasiloxane. Int J Toxicol. 2011 Dec;30(6 Suppl):149S–227S.

Robinson VC, Bergfeld WF, Belsito DV, Hill RA, Klaassen CD, Marks JG, Jr., et al. Final report of the amended safety assessment of sodium laureth sulfate and related salts of sulfated ethoxylated alcohols. Int J Toxicol. 2010 Jul;29(4 Suppl):151S–61S.

Ahn KC, Zhao B, Chen J, Cherednichenko G, Sanmarti E, Denison MS, et al. In vitro biologic activities of the antimicrobials triclocarban, its analogs, and triclosan in bioassay screens: receptor-based bioassay screens. Environ Health Perspect. 2008 Sep;116(9):1203–10.

James MO, Li W, Summerlot DP, Rowland-Faux L, Wood CE. Triclosan is a potent inhibitor of estradiol and estrone sulfonation in sheep placenta. Environ Int. 2010 Nov;36(8):942–9.

Panel CIRE. Final Report: Triclosan. Washington, DC: Cosmetic Ingredient Review, 2010.

Some N-Nitroso Compounds. World Health Organization, 1978.

Epstein SS. Toxic Beauty. Dallas: BenBella Books; 2009.

Skin Deep Cosmetic Database [database on the Internet]. Environmental Working Group. 2004 [cited 4/15/2016]. Available from: http://www.ewg.org/skindeep/.

Perfume & Scents. Cincinnati, OH: Proctor & Gamble.

Black PN, Sharpe S. Dietary fat and asthma: is there a connection? Eur Respir J. 1997 Jan;10(1):6–12.

Association OC. Carcinogenic 1,4-Dioxane Found in Leading “Organic” Brand Personal Care Products. Anaheim, CA: Organic Consumers Association; 2008.

National Toxicology P. Bioassay of 1,4-dioxane for possible carcinogenicity. Natl Cancer Inst Carcinog Tech Rep Ser. 1978;80:1–123.

Chemicals in cosmetics and their detection

Some studies have examined the relationship between use of personal care products and serum or urinary concentrations of the ingredients. Since very few studies specifically examined the association between cosmetics use and ingredients absorption, we will also include studies that examine topical personal care product use in order to provide a better picture of how these ingredients can be absorbed through the skin. This section will discuss the studies that have been published on siloxanes, diethanolamine, phthalates, and parabens.

Siloxanes

One study looked at use of personal care products in a cohort of 94 postmenopausal women in Norway and serum levels of estrogenic (20) and anti-androgenic (21) cyclic volatile methylsiloxanes (cVMS) (22). Sources of exposure to cVMS are generally through cVMS present in personal care products, inhalation due to the volatility of the compounds, or cVMS contained in breast implants (22). None of the women in the cohort had breast implants and 90.5% of the women creamed more than 10% of their skin area each day (22). cVMS also has a low blood:air partition coefficient and therefore inhalation exposure would have only had a minor contribution to serum levels of cVMS unless there was risk of workplace air exposure (22). Unfortunately, since different products carry varying levels of cVMS, no direct correlation was drawn between serum levels and specific personal care product use (22). Of the 94 women examined, 85% of the women exceeded the limit of quantification for octamethylcyclotetrasiloxane, 18% for decamethylcyclopentasiloxane, and 5% for dodecamethylcyclohexasiloxane (22).

Diethanolamine

A study provided three premenopausal women with lotion containing 1.8 mg diethanolamine/gram lotion and instructed them to apply the lotion every day for a month (23). Diethanolamine is a compound that is anti-estrogenic, anti-androgenic, and possibly carcinogenic (24–26). Blood samples of the subjects revealed detectable plasma concentrations of diethanolamine after lotion application (23).

Phthalates and parabens

An extensive study of personal care product use among pregnant women revealed significant associations between product use and urinary concentrations of phthalate metabolites and anti-androgenic (27) and estrogenic (28) parabens. Phthalates are a class of chemicals that have different hormonal activities depending on the congener’s compound structure (29). Braun et al. found that cosmetics users had 53% more urinary monoethyl phthalate (MEP) (95% CI: 9–113), 89% more butylparaben (BP) (95% CI: 21–198), 66% more methylparaben (MP) (95% CI: 17–137), and 105% more propylparaben (PP) (95% CI: 31–220) than non-cosmetics users (30).

A study with 332 postmenopausal women in Norway examined the association between serum paraben levels and personal care product use (31). Median serum levels of MPs were correlated with increasing percentage of skin area creamed per day (31). The observed trend was also significant for the total combination of MPs, PPs, and ethylparabens (p < 0.001), but increases in ethylparabens and PPs were observed in participants creaming more than 100% of their skin surface per day (i.e. multiple applications) (31).

A study of 337 women at follow-up visits 3–36 months after their pregnancies found that use of basic makeup (including eye makeup, foundation, and lipstick) was associated with increased urinary concentrations of MEP (β = 0.054, p = 0.029) and monomethyl phthalate (β = 0.040, p = 0.023) (32).

Menopause

Naturally occurring menopause is defined as amenorrhea for 12 full months (33). The current established average age at menopause in the US is 51.4 years old (33). In utero, the ovarian reserve of primordial follicles is built from ovarian germ cells. At four months postconceptional age, the ovary peaks at 6–7 million oocytes (34). Due to apoptosis, at birth only 1–2 million primordial follicles remain (34). Primordial follicle numbers continue to fall exponentially, albeit less rapidly, until menarchal onset when the ovary has 300,000 to 400,000 follicles remaining (34). At menopause, less than 1000 follicles remain (34). Natural menopause is a physiologic manifestation of a depleted follicular pool. Elevated follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone levels, and low anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH; a hormone used to estimate ovarian reserve (35)) are hallmark biochemical signs of menopause (33, 36). Menopause is preceded by a transition period (perimenopause) that can last several years starting from when a woman enters her fourth decade of life (33). Perimenopause is associated with changes in a woman’s reproductive hormones and is associated with waist thickening, vaginal dryness, and irregular periods (33). Other symptoms include hot flashes, irritability, and sleep disturbance (33).

Age at menopause: potential mechanisms

Age at menopause can be affected by various aspects such as race, family history, smoking -history, genetic predisposition, Fragile X syndrome, and autoimmune disorders (8, 37–44). There is some evidence that chemical exposure can affect age at menopause, but little research has been done directly linking exposure to chemicals in cosmetics with age at menopause. We will therefore discuss the potential mechanisms by which cosmetics ingredients may have an effect on age at menopause:

The onset of reproductive senescence is due to depletion of primordial follicles. It is believed that prenatal follicle assembly and rate of recruitment of primordial follicles are factors in the rate of depletion (45–47). Lower ovarian follicle reserves, increased number of follicles recruited for maturation per cycle, and absence of corpora lutea (CL) development indicate onset of reproductive senescence. Since the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis is crucial in the maintenance of reproductive organs as well as the menstrual cycle in females, any chemicals that disrupt the axis may also cause early reproductive senescence (48). Endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) are a class of exogenous chemicals that disrupts some aspect of a hormone’s mechanism (49). EDCs that are either estrogenic or anti-androgenic seem to play the largest role in this process of premature reproductive senescence (45) (See Supplement 1 for a summary of known estrogenic or anti-androgenic EDCs and reproductive senescence).

Failure of DNA repair mechanisms may also lead to failure in ovarian follicle reserves and earlier age at menopause. Ovarian follicle aging has been linked to lower expression of DNA double strand break repair genes BRCA1, MRE11, Rad51, and ATM (50). Women with BRCA1 mutations have shown significantly lower concentrations of AMH and earlier age at menopause (50–52). A meta-analysis of 22 genome-wide association studies in 38,968 women found additional associations between age at menopause and genes implicated in DNA repair (EXO1, HELQ, UIMC1, FAM175A, FANCI, TLK1, POLG and PRIM1) (53). Another study also found an association between a variant in the mismatch repair gene MSH6 with age at menopause (54).

Shortened leukocyte telomere length may also be associated with age at menopause, although the mechanisms are still unclear. It should be noted that DNA repair mechanisms and telomere length are mechanistically related (55), and telomere length can be affected by many elements, such as telomerase activity, oxidative stress, antioxidant activity, inflammation, the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis (glucocorticoid levels), and mitochondria regulation (56). One study found that among non-Hispanic white women, one standard deviation in longer leukocyte telomere length was associated with a 0.43 year later age at menopause (57). Among Mexican-American women, one standard deviation in shorter leukocyte telomere length was associated with a 1.56 year earlier age at menopause; and among non-Hispanic black women, no association was found (57). Another study with a cohort of 486 white women found that for every 1 kilobase increase in leukocyte telomere length, average age at natural menopause increased by 10.2 months (95% CI: 1.3–19.0), with no association seen in women with surgical menopause (58).

Oxidative stress can also affect the ovarian reserve in other ways. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) can induce primordial follicle loss and apoptosis in the ovary (59). ROS can also deplete glutathione, which then leads to atresia of antral follicles and apoptosis of granulosa cells (59). Oxidative stress also increases permeability in mitochondria (60), which exposes mitochondrial DNA to damaging elements (61). Damaged mitochondrial DNA has been linked to reproductive aging (55, 62). Mice lacking the glutamate cysteine ligase modifier subunit, the rate-limiting enzyme in production of the most abundant intracellular antioxidant, glutathione, showed increased oxidative stress, apoptosis in follicles, and accelerated age-related decline in primordial follicles compared to wild type mice (63).

Direct ovarian toxicity also accelerates reproductive senescence. While there is extensive evidence of environmental toxins and their effect on the ovaries (64), the effect of iatrogenic chemicals (chemotherapy and radiotherapy) is very well documented. Women who have undergone anticancer treatment, especially in adolescence, show accelerated depletion in ovarian reserve, decreased AMH levels, decreased ovarian volume, and advanced age at menopause (65–67).

Some of the chemicals in cosmetics have known carcinogenic effects. Studies of age at menopause and cancer in humans examine cohorts of patients that have undergone gonadotoxic chemotherapy. There is one study that demonstrated reproductive senescence due to the presence of cancer alone in rats. In that study, only 49% of female Wistar rats with administered neoplasms had regular estrous cycles by 30 weeks of age, and at 112 weeks of age, only 24% of female rats were still cycling but the majority of the animals had major cycle abnormalities (68).

The contribution of these mechanisms to early reproductive aging means that chemicals that are either anti-androgenic or estrogenic EDCs, that damage DNA repair mechanisms, that affect telomere length, that increase oxidative stress or reduce antioxidant activity, that increase ovarian toxicity, or that are carcinogenic have the potential to contribute to premature age at menopause. While this review examines the limited data on cosmetics use and age at menopause, it should be noted that there are a handful of articles that have published data indicating that there is a secular trend towards later age at menopause (69–72). This trend towards later age at menopause is associated with increasing physical activity and education level, as well as better childhood nutrition and health in the general population, but these studies also do not examine this secular trend stratified by cosmetics use (69, 72).

Cosmetics exposure and menopause

We present here the research on exposure to cosmetics ingredients/cosmetic use and age at menopause. Unfortunately, most of the chemicals that we mention in this review have not been evaluated in relation to age at menopause, and of the chemicals that have been studied, there is very little published data. Due to the limited amount of studies, we expanded our literature search to include studies examining topical personal care product use. The studies noted below were found with the same search terminology reported in the methods section and represent the complete set of articles in that search.

One study examined phthalate levels in the personal care products of 195 women aged 45–54, urinary phthalate levels, and self-reported hot flashes history experienced (73). Phthalate concentrations in personal care products were estimated by summing the metabolite molar concentrations of monobutyl phthalate and MEP (73). The sum of personal care product urine phthalate levels was associated with: 1) ever experiencing hot flashes (odds ratio = 1.45, CI = 1.07–1.96), 2) experiencing moderate/severe hot flashes (odds ratio = 1.31, CI = 0.95–1.82), 3) experiencing hot flashes in the past 30 days (odds ratio = 1.43, CI = 1.04–1.96), and 4) experiencing daily hot flashes (odds ratio = 1.47, CI = 1.06–2.05) (73). Previous research has linked hot flash severity in the perimenopausal transition to earlier age at menopause (74).

Another study of urinary paraben levels in 192 women presenting for fertility care in the Boston, Massachusetts area found MP and PP in more than 99% of urine samples and BP in more than 75% (75). The study found a trend towards decreased antral follicle counts and increased day three FSH levels with increasing PP tertiles (75). However the study did not achieve statistical significance (75). No other consistent associations were found with the other parabens or with ovarian volume (75).

Exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), which are a known contaminant of inadequately refined petrolatum, has been shown to increase proapoptotic gene expression in the ovary as well as induce oocyte depletion via p53 (76). There is some evidence that the ovarian toxicity of PAHs work through the aromatic hydrocarbon receptor which induces Bax gene expression that induces apoptosis (77). Benzo(a)pyrene (BaP), a PAH contaminant sometimes detected in cosmetics (78), also induced significant DNA damage in oocytes and cumulus cells (79), as well as decreased CL counts and ovarian volume in mice (80). A study of BaP and two other PAHs in mice and rats found that exposure to all three PAHs resulted in drastically lower numbers of primordial and primary follicles (81). Surprisingly, the study also found that chronic low dose exposure to the three PAHs was more toxic compared to acute high dose exposure (81). PAHs have also been found to be anti-androgenic, estrogenic, carcinogenic, and potentially genotoxic (79, 82–84).

A study examined how gestational exposure of Wistar rats to a mixture of proven human EDCs (italicized compounds or their metabolites have been found in cosmetics; di-n-butyl phthalate, di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate, vinclozolin, prochloraz, procymidone, linuron, epoxiconazole, octyl methoxycinnamate, dichlorodiphenyl-dichloroethylene (p,p′-DDE), 4-methyl-benzylidene camphor, BPA, butyl paraben, and paracetamol) affected ovarian follicle reserves and reproductive aging (85). The study examined the effects of subjecting the rats to a mix of all the EDCs (Totalmix), to a mix of the anti-androgenic EDCs (4-methyl-benzylidene camphor, octyl methoxycinnamate, BPA, and BP; AAmix), and to a mix of the estrogenic EDCs (di-n-butyl phthalate, di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate, vinclozolin, prochloraz, procymidone, linuron, epoxiconazole, p,p′-DDE; Emix) (85). Rats exposed to AAmix had significantly reduced numbers of primordial follicles (78.2% of control values; p = 0.02) (85). Rats exposed to AAmix also had significantly lower percentages of primordial follicles (p = 0.005) and significantly higher percentages of secondary (p = 0.05) and tertiary follicles (p = 0.04) out of the total number of follicles (85). The number of total recruited follicles was also significantly higher in rats exposed to AAmix (p = 0.01) (85). At 12 months of age, rats exposed to Totalmix had a significant increase in irregular estrous cycles (p = 0.041), as well as significantly lower ovarian weight in rats exposed to Totalmix and AAmix (85). In addition, at 13 months of age, rats exposed to AAmix had a significant increase in incidence of complete absence of CL (p = 0.033), as well as a significant reduction in mean number of CL to 55% of controls in the Totalmix group (p = 0.04) and approached significance for the AAmix group (p = 0.056) (85).

Considerations of other personal care products

While we have examined the ingredients in cosmetics, specifically limited to face makeup, eye makeup, and lip makeup, these products are but a subset of personal care products. This paper does not extensively cover the hazards of sunscreen, hair dye, makeup remover, lotion, skin lightener, anti-aging/anti-wrinkle creams, and chemicals associated with nail embellishment, to name a few. Another subset of products we do not address that is gaining particular traction is the “fountain of youth” agents, which often contain hydroquinone, retinol, sunscreen, antioxidants, and alpha hydroxyl acids. Here we will give a brief overview of some of the above products in hopes that future research will also take these areas into consideration.

The Braun et al. study mentioned previously also found several associations between use of different personal care products and increased urinary phthalate and paraben levels. Users of shampoo, conditioner, and nail polish had significantly higher urinary levels of phthalates (30). Users of hair gel had higher urinary levels of parabens (30). Lastly, users of lotion and cologne/perfume had higher urinary levels of both pthalates and parabens (30). Perfume, lotion, deodorant, hair spray, crème rinse, other hair products, and bar soap were all positively and significanty associated with urinary MEP levels (32). There was also a significant association between total number of personal care products used in the 24 hours before the urine spot test and median creatinine-adjusted log10-transformed MEP concentrations. In a study of 108 women in Mexico, increased use of body lotion, deodorant, perfume, and anti-aging facial cream use was associated with increased median urinary phthalate concentrations (86). Another study of 186 minority pregnant women in New York City revealed that women who used perfume had 2.3 times higher urinary MEP concentrations (95% CI: 1.6–3.3) (87).

Suntan and sunscreen products are also particularly harmful. Polyaromatic hydrocarbons (78) as well as benzophenones are used as ingredients in these products (88). Benzophenone passes through the skin and enters the blood stream (89), along with other sunscreen chemicals such as octyl-methoxycinnamate and 3-(4-methylbenzylidene) camphor (90). Benzophenone has been shown to be endocrine disrupting in animals (91, 92), positively associated with women with uterine leiomyomas and endometriosis (93, 94), and increased oxidative stress and genotoxicity (95, 96). Benzophenones are not just limited to sunscreen products. They are found in makeup, lotion, and hair products in order to protect consumers from the sun (97).

Skin lighteners are commonly used in minority races/ethnicities (98–101), and as a result this population of women are at particular risk of exposure to toxic chemicals that are in skin lightening products such as mercury, hydroquinone, and steroids (102, 103). Vaginal douching, which a study on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2001–2004 found to be more common in black women than white or Mexican American women, is significantly associated with higher urinary concentrations of MEP (104). Hair products, which contain a significant amount of phenylenediamine, a coal tar dye, also contain formaldehyde releasing chemicals (105, 106).

The Madrid Statement is a document released in 2015 by over 200 scientists worldwide calling to limit the use of fluorinated chemicals in everyday products (19), and it has previously been shown that fluorinated chemicals are pervasive in personal care products (107). A database compiled by the Green Science Policy Institute, a group of scientists based in California dedicated to promoting responsible use of chemicals, reveals that there are several perfluorinated and polyfluorinated chemicals that are used in a variety of cosmetics (108). While there are too many to examine individually, one chemical, polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), popularly known as Teflon®, is of particular concern. It is used in a variety of products, including face makeup, eye makeup, men’s shaving cream, and sunscreen, as a bulking agent and slip modifier (17, 108). PTFE is traditionally produced by using perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) as a surfactant during emulsion polymerization of PTFE, leading to concerns that PTFE is contaminated with PFOA (109). The adverse health effects of PFOA have been numerously studied. In relation to menopause, a study of 25,957 women aged 18–65 found that the odds of having experienced menopause were significantly higher in the highest quintile of exposure to estrogenic PFOA and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) compared to the lower quintile of exposure in women aged 42–51 (PFOS odds = 1.4, confidence interval (CI) = 1.1–1.8; PFOA odds =1.4, CI = 1.1–1.8) and in women aged 52 and above (PFOS odds = 2.1, CI=1.6–2.8; PFOA odds = 1.7, CI = 1.3–2.3) (110). In the NHANES cohort, women in the second and third tertile serum levels of estrogenic polyfluoroalkyl chemicals had significantly higher incidence of menopause than women in the first tertile (hazard ratio = 1.23, 95% CI = 1.04–1.44 for tertile 2; hazard ratio = 1.16, 95% CI = 0.91–1.48 for tertile 3) (111). For women in the third tertile of serum levels of perfluorooctanoate, perfluorononanoate, and perfluorohexane sulfonate compared to women in the first tertile, the adjusted hazard ratios were 1.36 (95% CI: 1.05, 1.75), 1.47 (95% CI: 1.14, 1.90), and 1.70 (95% CI: 1.36, 2.12), respectively (111). For women in the second tertile of serum levels of perfluorooctanoate, perfluorononanoate, and perfluorohexane sulfonate compared to women in the first tertile, the adjusted hazard ratios were 1.22 (95% CI: 0.92, 1.62), 1.43 (95% CI: 1.07, 1.91), and 1.42 (95% CI: 1.08, 1.87), respectively (111). However, a study evaluating serum levels of PFOA from environmental exposure and age at menopause in women aged 40 years and above in the Mid-Ohio Valley community demonstrated no statistically significant associations (112). Due to the known health hazards of PFOA, PTFE is now produced by many manufacturers with chemicals other than PFOA (113); however, cosmetic companies do not specify how they manufacture the PTFE that they use.

Conclusion

While we have examined the ingredients in cosmetics, specifically limited to face makeup, eye makeup, and lip makeup, these products are but a subset of personal care products. This paper does not extensively cover the hazards of sunscreen, hair dye, makeup remover, lotion, skin lightener, anti-aging/anti-wrinkle creams, and chemicals associated with nail embellishment, to name a few. Another subset of products we do not address that is gaining particular traction is the “fountain of youth” agents, which often contain hydroquinone, retinol, sunscreen, antioxidants, and alpha hydroxyl acids. As such, evaluation of other personal care products and use of mixtures in relation to ovarian health is very important.

Most of the reviewed chemicals have demonstrated dermal absorption. Certain chemicals have limited dermal absorption, such as formaldehyde (23, 114). However, studies evaluating formaldehyde are limited by studying the exposure for as short as one month. Other limitations include no evaluation of body repositories of these chemicals such as visceral and subcutaneous fat compartments. Women apply these products to their face daily, sometimes even more than once daily, which can lead to several grams of exposure per product per day, over the course of a woman’s lifespan (115–118). As seen above, chronic low dose exposure to PAHs is more toxic to the ovaries than acute high dose exposure (81), and future studies need to explore if this is true for other chemicals.

In addition, while studies have examined the impact of these chemicals individually, little work has been done on the potential interactions that these chemicals can have on each other and how these mixtures can then affect human physiology. Women generally use more than one product (115–117), and the ingredients that are contained in different products can interact with each other. In addition, while one product may contain a level of these ingredients that have been deemed safe, continuous use and use of several products containing these ingredients can easily expose a woman to levels that are beyond what has been defined as safe. Another consideration that must be taken into account is the packaging for these cosmetics. Packaging and plastic materials have been shown to have toxins that can leach into products and adversely affect human health (119–121). It would be reasonable to extrapolate that the plastic packaging of many cosmeticsmay leach additional toxins into the products, which are then applied to the skin. These are considerations that need to be taken seriously as we continue to evaluate the long term adverse impact that cosmetic use has on a woman.

One last consideration is incomplete reporting of ingredients. While cosmetics companies are for the most part required to report all of the ingredients they use, there are still some exceptions. As mentioned before, all chemicals that are used as fragrance do not need to be reported and can simply be listed as “parfum” or “fragrance.” The same applies for cosmetics that have flavors, most often found in lipstick. Some of the cosmetics we looked at simply had “Flavor” written, with no indication of what ingredients this broad term referred to. In addition, a couple of the Brand A products that we examined contained “Shimmer Shades,” which was followed up by a note that said “Shimmer Shades may contain:” with potential ingredients listed. Consumers have no way of knowing the exact composition of ingredients of the Shimmer Shades due to the vague wording. Lastly, Brand B products have several ingredients in their products that are listed as FIL D*****/2, with * representing a number. Our search for what these ingredients may be reveals nothing.

Currently, limited evidence has demonstrated that few patients are counseled regarding safe cosmetics use. A study found that only 23.4% of 128 women surveyed had received advice about personal care product use and only 18.9% of them had received advice about make-up product use (9). Health care providers should make attempts to make their patients aware of the developing literature around the chemicals used in cosmetics and help educate their patient population to make more informed personal care product choices. Many groups are now disseminating information in hopes of making consumers aware of the toxins in these cosmetics, such as the Environmental Working Group (EWG), Campaign for Safe Cosmetics, and the David Suzuki Foundation. In addition, the EWG has created a Skin Deep® Cosmetics Database that allows consumers to search for personal care products and determine the hazard level of each product.

Limitations of this review are in large part due to our inability to assess each and every ingredient and their mixture effects, and the lack of available data regarding the vast number of chemicals that are in cosmetics with age at menopause. A more comprehensive investigation of cosmetics and their effects on menopause, reproductive health, and the health of other organ systems need to further investigated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

All authors have made substantial contributions at all levels, from conception to revision and final edits. E.C. drafted the review, and all authors critically revised it for intellectual content. The final version of this review has been approved by all authors for publication.

S.M. is supported by the Reproductive Scientist Development Program from the NIH/NICHD Grant K12 HD000849.

Footnotes

EC: 670 Albany Street 5th Floor Boston, MA 02118 USA

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Barker DJ, Barker MJ. The body as art. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2002 Jul;1(2):88–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1473-2165.2002.00027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hill SE, Rodeheffer CD, Griskevicius V, Durante K, White AE. Boosting beauty in an economic decline: mating, spending, and the lipstick effect. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2012 Aug;103(2):275–91. doi: 10.1037/a0028657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ehlinger-Martin A, Cohen-Letessier A, Taieb M, Azoulay E, du Crest D. Women’s attitudes to beauty, aging, and the place of cosmetic procedures: insights from the QUEST Observatory. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2016 Mar;15(1):89–94. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stearn WT. The Origin of the Male and Female Symbols of Biology. Taxon. 1962;11(4):109–13. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oumeish OY. The cultural and philosophical concepts of cosmetics in beauty and art through the medical history of mankind. Clin Dermatol. 2001 Jul-Aug;19(4):375–86. doi: 10.1016/s0738-081x(01)00194-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dictionary OE. cosmetic, adj. and n. Oxford University Press; [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dawber TR, Kannel WB, Lyell LP. An approach to longitudinal studies in a community: the Framingham Study. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1963 May 22;107:539–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1963.tb13299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daan NM, Fauser BC. Menopause prediction and potential implications. Maturitas. 2015 Nov;82(3):257–65. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marie C, Cabut S, Vendittelli F, Sauvant-Rochat MP. Changes in Cosmetics Use during Pregnancy and Risk Perception by Women. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(4) doi: 10.3390/ijerph13040383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Is It a Cosmetic, a Drug, or Both? (Or Is It Soap?) U.S. Food and Drug Administration; 2002. [updated 4/30/20124/5/2016]; Available from: http://www.fda.gov/Cosmetics/GuidanceRegulation/LawsRegulations/ucm074201.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butler MG, McGuire A, Manzardo AM. Clinically relevant known and candidate genes for obesity and their overlap with human infertility and reproduction. Journal of assisted reproduction and genetics. 2015 Apr;32(4):495–508. doi: 10.1007/s10815-014-0411-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Color Additives and Cosmetics. U.S. Food and Drug Administration; 2006. [updated 4/29/20074/5/2016]; Available from: http://www.fda.gov/ForIndustry/ColorAdditives/ColorAdditivesinSpecificProducts/InCosmetics/ucm110032.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rumans IWGotEoCRt., editor. Occupational Exposures of Hairdressers and Barbers and Personal Use of Hair Colourants; Some Hair Dyes, Cosmetic Colourants, Industrial Dyestuffs and Aromatic Amines. International Agency for Research on Cancer; 1993. p. 457. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zanoni TB, Hudari F, Munnia A, Peluso M, Godschalk RW, Zanoni MV, et al. The oxidation of p-phenylenediamine, an ingredient used for permanent hair dyeing purposes, leads to the formation of hydroxyl radicals: Oxidative stress and DNA damage in human immortalized keratinocytes. Toxicol Lett. 2015 Dec 15;239(3):194–204. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2015.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reena K, Ng KY, Koh RY, Gnanajothy P, Chye SM. para-Phenylenediamine induces apoptosis through activation of reactive oxygen species-mediated mitochondrial pathway, and inhibition of the NF-kappaB, mTOR, and Wnt pathways in human urothelial cells. Environ Toxicol. 2016 Jan 19; doi: 10.1002/tox.22233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goudreau J. The Top 10 Global Beauty Brands. Forbes Magazine. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skin Deep Cosmetic Database [database on the Internet] Environmental Working Group; 2004. [cited 4/15/2016]. Available from: http://www.ewg.org/skindeep/ [Google Scholar]

- 18.The “Dirty Dozen” Ingredients Investigated in the David Suzuki Foundation Survey of Chemicals in Cosmetics. David Suzuki Foundation; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blum A, Balan SA, Scheringer M, Trier X, Goldenman G, Cousins IT, et al. The Madrid Statement on Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) Environ Health Perspect. 2015 May;123(5):A107–11. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1509934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quinn AL, Regan JM, Tobin JM, Marinik BJ, McMahon JM, McNett DA, et al. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of the estrogenic, androgenic, and progestagenic potential of two cyclic siloxanes. Toxicol Sci. 2007 Mar;96(1):145–53. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKim JM, Jr, Wilga PC, Breslin WJ, Plotzke KP, Gallavan RH, Meeks RG. Potential estrogenic and antiestrogenic activity of the cyclic siloxane octamethylcyclotetrasiloxane (D4) and the linear siloxane hexamethyldisiloxane (HMDS) in immature rats using the uterotrophic assay. Toxicol Sci. 2001 Sep;63(1):37–46. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/63.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanssen L, Warner NA, Braathen T, Odland JO, Lund E, Nieboer E, et al. Plasma concentrations of cyclic volatile methylsiloxanes (cVMS) in pregnant and postmenopausal Norwegian women and self-reported use of personal care products (PCPs) Environ Int. 2013 Jan;51:82–7. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Craciunescu CN, Niculescu MD, Guo Z, Johnson AR, Fischer L, Zeisel SH. Dose response effects of dermally applied diethanolamine on neurogenesis in fetal mouse hippocampus and potential exposure of humans. Toxicol Sci. 2009 Jan;107(1):220–6. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kassotis CD, Klemp KC, Vu DC, Lin CH, Meng CX, Besch-Williford CL, et al. Endocrine-Disrupting Activity of Hydraulic Fracturing Chemicals and Adverse Health Outcomes After Prenatal Exposure in Male Mice. Endocrinology. 2015 Dec;156(12):4458–73. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kassotis CD, Tillitt DE, Davis JW, Hormann AM, Nagel SC. Estrogen and androgen receptor activities of hydraulic fracturing chemicals and surface and ground water in a drilling-dense region. Endocrinology. 2014 Mar;155(3):897–907. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Toxicology Data Network [database on the Internet] National Institutes of Health, Health & Human Services; 2014. [cited 4/15/2016]. Available from: http://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/ [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen J, Ahn KC, Gee NA, Gee SJ, Hammock BD, Lasley BL. Antiandrogenic properties of parabens and other phenolic containing small molecules in personal care products. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007 Jun 15;221(3):278–84. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Routledge EJ, Parker J, Odum J, Ashby J, Sumpter JP. Some alkyl hydroxy benzoate preservatives (parabens) are estrogenic. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1998 Nov;153(1):12–9. doi: 10.1006/taap.1998.8544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parveen M, Inoue A, Ise R, Tanji M, Kiyama R. Evaluation of estrogenic activity of phthalate esters by gene expression profiling using a focused microarray (EstrArray) Environ Toxicol Chem. 2008 Jun;27(6):1416–25. doi: 10.1897/07-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braun JM, Just AC, Williams PL, Smith KW, Calafat AM, Hauser R. Personal care product use and urinary phthalate metabolite and paraben concentrations during pregnancy among women from a fertility clinic. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2014 Sep-Oct;24(5):459–66. doi: 10.1038/jes.2013.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sandanger TM, Huber S, Moe MK, Braathen T, Leknes H, Lund E. Plasma concentrations of parabens in postmenopausal women and self-reported use of personal care products: the NOWAC postgenome study. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2011 Nov-Dec;21(6):595–600. doi: 10.1038/jes.2011.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parlett LE, Calafat AM, Swan SH. Women’s exposure to phthalates in relation to use of personal care products. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2013 Mar;23(2):197–206. doi: 10.1038/jes.2012.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Menopause: Time for a Change. National Institutes of Health; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Broekmans FJ, Soules MR, Fauser BC. Ovarian aging: mechanisms and clinical consequences. Endocr Rev. 2009 Aug;30(5):465–93. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iwase A, Osuka S, Nakamura T, Kato N, Takikawa S, Goto M, et al. Usefulness of the Ultrasensitive Anti-Mullerian Hormone Assay for Predicting True Ovarian Reserve. Reprod Sci. 2015 Nov 26; doi: 10.1177/1933719115618284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cui L, Qin Y, Gao X, Lu J, Geng L, Ding L, et al. Antimullerian hormone: correlation with age and androgenic and metabolic factors in women from birth to postmenopause. Fertil Steril. 2016 Feb;105(2):481–5. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Henderson KD, Bernstein L, Henderson B, Kolonel L, Pike MC. Predictors of the timing of natural menopause in the Multiethnic Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2008 Jun 1;167(11):1287–94. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gold EB, Crawford SL, Avis NE, Crandall CJ, Matthews KA, Waetjen LE, et al. Factors related to age at natural menopause: longitudinal analyses from SWAN. Am J Epidemiol. 2013 Jul 1;178(1):70–83. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bromberger JT, Matthews KA, Kuller LH, Wing RR, Meilahn EN, Plantinga P. Prospective study of the determinants of age at menopause. Am J Epidemiol. 1997 Jan 15;145(2):124–33. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Voorhuis M, Onland-Moret NC, Janse F, Ploos van Amstel HK, Goverde AJ, Lambalk CB, et al. The significance of fragile X mental retardation gene 1 CGG repeat sizes in the normal and intermediate range in women with primary ovarian insufficiency. Hum Reprod. 2014 Jul;29(7):1585–93. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mayorga J, Alpizar-Rodriguez D, Prieto-Padilla J, Romero-Diaz J, Cravioto MC. Prevalence of premature ovarian failure in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2015 Dec 16; doi: 10.1177/0961203315622824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Torgerson DJ, Thomas RE, Reid DM. Mothers and daughters menopausal ages: is there a link? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1997 Jul;74(1):63–6. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(97)00085-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Snieder H, MacGregor AJ, Spector TD. Genes control the cessation of a woman’s reproductive life: a twin study of hysterectomy and age at menopause. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998 Jun;83(6):1875–80. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.6.4890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fenton AJ. Premature ovarian insufficiency: Pathogenesis and management. J Midlife Health. 2015 Oct-Dec;6(4):147–53. doi: 10.4103/0976-7800.172292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Uzumcu M, Zachow R. Developmental exposure to environmental endocrine disruptors: consequences within the ovary and on female reproductive function. Reprod Toxicol. 2007 Apr-May;23(3):337–52. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Bourguignon JP, Giudice LC, Hauser R, Prins GS, Soto AM, et al. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: an Endocrine Society scientific statement. Endocrine reviews. 2009 Jun;30(4):293–342. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Depmann M, Faddy MJ, van der Schouw YT, Peeters PH, Broer SL, Kelsey TW, et al. The Relationship Between Variation in Size of the Primordial Follicle Pool and Age at Natural Menopause. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015 Jun;100(6):E845–51. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]