Abstract

IFN-β, IL-27 and IL-10 have been shown to exert a range of similar immunoregulatory effects in murine and human experimental systems, particularly in Th1 and Th17 mediated models of autoimmune inflammatory disease. In this study we sought to translate some of our previous findings in murine systems to human in vitro models and delineate the inter-dependence of these different cytokines in their immunoregulatory effects. We demonstrate that human IL-27 upregulates IL-10 in T cell-activated PBMC cultures and that IFN-β drives IL-27 production in activated monocytes. IFN-β-driven IL-27 is responsible for the upregulation of IL-10, but not IL-17 suppression, by IFN-β in human PBMCs. Surprisingly, IL-10 is not required for the suppression of IL-17 by either IL-27 or IFN-β in this model or in de novo differentiating Th17 cells. Neither is IL-27 signaling required for the suppression of EAE by IFN-β in vivo. Further, and even more surprisingly, IL-10 is not required for the suppression of Th17-biased EAE by IL-27, in sharp contrast to Th1-biased EAE. In conclusion, IFN-β and IL-27 both induce human IL-10, both suppress human Th17 responses and both suppress murine EAE. However, IL-27 signaling is not required for the therapeutic effect of IFN-β in EAE. Suppression of Th17-biased EAE by IL-27 is IL-10-independent, in contrast to its mechanism of action in Th1-biased EAE. Together, these findings delineate a complex set of inter-dependent and independent immunoregulatory mechanisms of IFN-β, IL-27 and IL-10 in human experimental models and in murine Th1 and Th17-driven autoimmunity.

Keywords: IL-27, EAE, IFN-β, IL-10

INTRODUCTION

IL-27 is a heterodimeric cytokine with pleiotropic functions, particularly in immunity. Originally regarded as a Th1-inducing cytokine, it is now recognized that IL-27 exerts potent anti-inflammatory effects in both infection and autoimmunity (1). IL-27 consists of a p28 subunit and an Epstein-Barr virus-induced gene 3 (EBI-3) subunit (2), the latter of which is shared with IL-35 (3, 4). Although produced primarily by activated antigen-presenting cells (APCs), a range of cell types have been shown to express IL-27 including astrocytes and microglia (5–9). IL-27 signals via the IL-27 receptor (IL-27R) which is composed of a WSX-1 subunit (also known as TCCR and IL-27Rα) and the gp130 subunit (IL-6R) which is shared by other cytokine receptors (10). The IL-27R is expressed on numerous cell types including T cells, Natural killer (NK) cells, B cells, monocytes, mast cells, Dendritic Cells (DC) and endothelial cells (11). IL-27 activates multiple JAK/STAT signaling pathways depending on the cell type it targets resulting in a wide range of cellular responses observed following IL-27R ligation. Some of the known anti-inflammatory effects of IL-27 include suppression of IL-2 (10), suppression of Th17 differentiation (9, 12), induction of SOCS3 (13) and upregulation of IL-10 (14–17). Interestingly, IFN-β is also a key inducer of IL-10 and a suppressor of Th17 differentiation (18, 19).

Interferon-beta (IFN-β) is a monomeric type one interferon with both anti-viral and potent anti-inflammatory effects. IFN-β signaling is mediated through the common type one interferon receptor and proceeds through the classical JAK-STAT signaling pathway (20). Despite the fact that IFN-β was the first immunomodulatory therapy approved by the FDA for MS and is a first line treatment for Multiple Sclerosis (MS), its exact mechanism of action has yet to be elucidated. Furthermore, many patients do not respond to IFN-β or cease to show a clinical response after some time (21, 22). The major effects of IFN-β include inhibition of T cell proliferation and IFN-γ production, inhibition of MHC II expression, inhibition of matrix metalloproteinase production and cell-associated adhesion molecule expression, induction of anti-inflammatory cytokines, inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokines, induction of CD8 regulatory cell function and inhibition of monocyte activation (reviewed in (22)). Of note, upregulation of IL-10 is positively predictive of a clinical response to IFN-β therapy in MS (23).

Since the initial characterization in 2005, Th17 cells have been implicated in a range of inflammatory diseases in several species and have become an attractive target for therapeutic intervention (24). While the understanding of murine Th17 cell development, regulation and function has evolved at a significant pace, there is an understandable lag in the translation of such findings to human models. To target Th17 cells in human disease therapeutically, such translational studies are essential. Inhibition of Th17 cells by IL-27 and IFN-β was shown in a range of murine models both in vitro and in vivo (13, 25–27). However, the range of mechanisms of human Th17 cell inhibition by IL-27 and IFN-β are less well understood. In human experimental models studies have shown that IFN-β can directly inhibit Th17 responses in CD4+ T cells (28). Furthermore IFN-β can impair the ability of DC and B cells to promote Th17 differentiation by inhibiting IL-23p19 and IL-1β expression while promoting IL-12p35 and IL-27p28 expression by these cell populations (18, 29, 30).

Here we have studied a complex network of independent and inter-dependent effects of IL-27, IFN-β and IL-10 on Th17 cells and CNS autoimmune inflammation. We were surprised to find that despite suggestive in vitro findings to the contrary, IL-27R signaling is not required for EAE suppression by IFN-β. Furthermore, we identified that IL-27 suppresses Th17-biased EAE in an IL-10-independent manner, which is in contrast to its mechanism of suppression in Th1-biased EAE that we reported previously (16). Taken together, our findings show that IL-27 orchestrates multiple suppressive pathways in EAE dependant on the phenotype of disease pathogenicity and is not required for the suppressive effect of IFN-β in actively-induced EAE.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Preparation and Treatment

Whole venous blood was collected in EDTA-treated tubes from healthy donors with informed consent. PBMCs were isolated using FiColl-Paque Plus™ density centrifugation while cord blood cells were obtained from AllCells. CD4+ and CD14+ cells were purified by immunomagnetic separation using CD4+/CD14+ MicroBeads and subsequent positive selection using a QuadroMACS separator. All human cells with the exception of monocytes were stimulated with Anti-Biotin MACSiBead™ particles loaded with CD2, CD3, and CD28 antibodies (T-Cell Activation/Expansion Kit, Miltenyi Biotec) at a ratio of one bead particle for every two cells. Monocytes were stimulated with either lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 20 μg/ml) or peptidoglycan (PGN; 1 μg/ml). Cells were cultured at a density of 5×105 cells/mL for PBMCs and CD4+ cells and 5×106 cell/mL for monocytes in 96-well U-bottomed plates in serum-free X-VIVO™ 15 medium. Unless otherwise stated PBMCs, cord blood cells, and CD4+ cells were incubated for 5 days while CD14+ monocytes were incubated for 48 hours. To induce de novo Th17 differentiation combinations of cytokines were used as described in figure legends.

Media/Reagents

Cells were prepared and cultured in X-VIVO™ 15 medium unless otherwise stated. Lipopolysaccharide (Escherichia coli) and peptidoglycan (Staphylococcus aureus) were obtained from Sigma Aldrich. Human IFN-β1a was obtained from PBL InterferonSource. Recombinant human IL-21 and IL-23 were obtained from eBiosciences while recombinant human IL-27 and IL-1β were obtained from R&D Systems. TGF-β was obtained from PeproTech. Neutralizing anti-IL-27 and anti-IL-10 antibodies were also obtained from R&D Systems.

Cytokine Quantification

Supernatants were harvested and stored at −20° C at the termination of the indicated incubation periods. Cytokine levels were measured by ELISA according to manufacturers’ instructions using DuoSet Development Kits (R&D Systems).

Flow Cytometry

Cells were washed in staining buffer containing 1% FCS and 0.1% sodium azide in PBS and stained with appropriate antibodies (PerCP Cy 5.5 conjugated anti-human IL-17A; eBiosciences, APC-Cy7 mouse anti-human CD4, APC mouse anti-human IFN-γ, isotope controls; BD Pharmingen). Stained cells were fixed and permeabilized with Caltag Fix & Perm reagents (Invitrogen). Data from labeled cells were acquired with a BD FACSAria® flow cytometer and analyzed using Flowjo software (Treestar).

Mice and EAE Induction

Eight to twelve week old wild-type (WT) female C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories. Experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Thomas Jefferson University.

Actively induced EAE

Mice were immunized s.c. with 150μg of MOG in CFA containing 5mg/mL Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Difco Laboratories) at two sites on the back. Mice were injected with 200ng of pertussis toxin in PBS on day 0 and 2 and were scored daily using an EAE clinical scale as detailed below.

Adoptively Transferred EAE

Donor mice were immunized s.c. with 150μg of MOG in CFA containing 5mg/mL Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Difco Laboratories) at four sites on the back. Eleven days after immunization, cells were harvested from lymph nodes and spleens and cultured for 72 hours in the presence of IL-23 (10ng/mL). Purified CD4+ cells were injected i.v. into recipient mice (5×106/mouse) and mice were injected with 200ng of pertussis toxin in PBS on day 0 and 2 after transfer. Mice were scored daily using an EAE clinical scale as detailed below.

Scoring

Mice were scored daily according to the following scale: 0 – no sign of clinical disease, 1 – paresis of the tail, 2 – paresis of one hind limb, 3 – paresis of both hind limbs, 4 – paresis of the abdomen, 5 – moribund/death.

Statistical Analysis

For EAE studies, the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated for each mouse and values of experimental groups were compared for statistical significance using Instat software. Data were considered statistically significant where p<0.05 in a two-tailed, unpaired, Student’s t-test with Welch’s correction where appropriate.

RESULTS

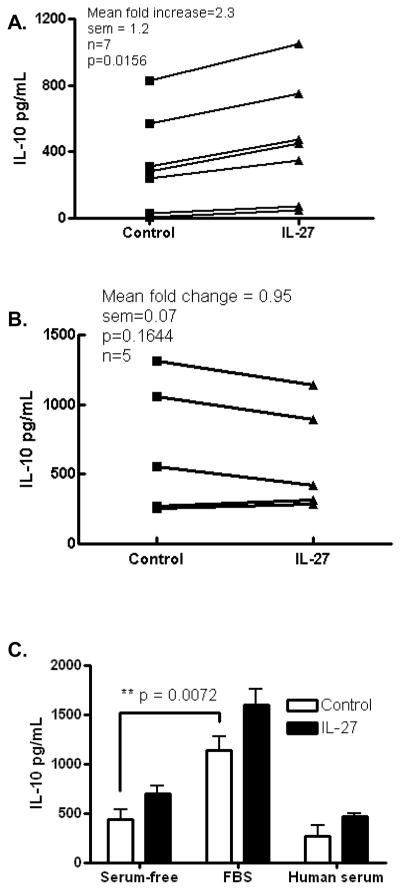

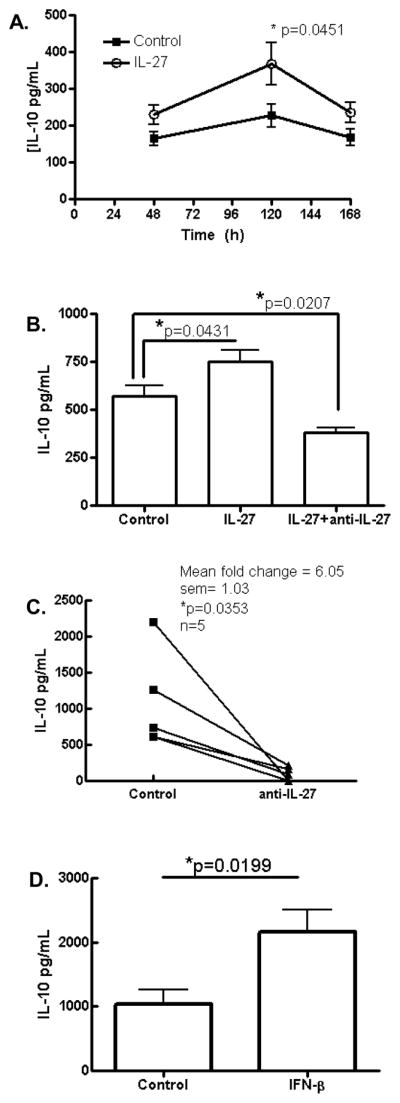

IL-27 upregulates IL-10 production in human T cells

We, and others, have shown in murine models, that IL-27 drives the production of IL-10 by T cells (14–17). To examine if this also occurs in human systems we activated T cells in human PBMC cultures with anti-CD2/anti-CD3/anti-CD28 antibodies in the presence or absence of exogenous IL-27. We found elevated IL-10 in the supernatant of IL-27-treated cultures demonstrating that human IL-27 upregulates IL-10 production. To confirm that this was common to multiple donors we performed this study separately in PBMCs from seven individuals and consistently observed upregulation of IL-10 by IL-27 albeit to varying degrees in individual donors (Fig. 1A). Others have reported upregulation of IL-10 production by IL-27 in cultures of purified human CD4+ T cells (26) however, we did not observe a consistent effect of exogenous IL-27 on IL-10 production in purified CD4+ T cells in our culture system in 5 donors (Fig. 1B). This suggests that other cells or mediators may be involved in the optimal upregulation of IL-10 in CD4+ T cells by IL-27. However, one key difference between our culture system and that used by Murugaiyan et al. is that our culture system used X-VIVO™ 15 medium equating to serum free conditions. Therefore we tested the effect of IL-27 on IL-10 production in culture systems with and without sera. Fetal bovine serum (FBS) significantly increased basal IL-10 production in activated PBMC cultures, however, human serum did not (Fig. 1C) suggesting that factors present in FBS potentiate IL-10 production. Although IL-27 showed a trend of upregulating IL-10 production in the presence of serum, results were highly variable between experiments and thus we opted to proceed with studies in serum free condition utilizing PBMCs in order to more specifically study the role of IL-27 in IL-10 upregulation.

Figure 1. IL-27 upregulates IL-10 production by human PBMCs in vitro.

PBMCs from healthy donors were activated with anti-CD2/anti-CD3/anti-CD28 antibodies for 5 days and supernatants were assayed for IL-10 by ELISA. IL-27 upregulated IL-10 production in PBMC cultures (A) but not in purified CD4+ T cells (B). Addition of FBS to serum-free X-VIVO™ 15 medium potentiated IL-10 production in whole PBMC cultures (C). Data representative of at least two independent experiments (C) or 5–7 donors (A, B).

To examine the kinetics of IL-10 production, we performed a time course analysis and observed maximal upregulation of IL-10 by IL-27 at 5 days post stimulation (Fig. 2A). To confirm that upregulation of IL-10 was specifically due to exogenous IL-27 we added neutralizing anti-IL-27 antibody to the system and observed inhibition of IL-10 upregulation by exogenous IL-27 (Fig. 2B). Interestingly we observed that levels of IL-10 in the presence of neutralizing anti-IL-27 antibody were in fact significantly lower than basal IL-10 levels suggesting that endogenous IL-27 contributes to basal IL-10 production in anti-CD2/CD3/CD28 activated PBMCs. To confirm that endogenous IL-27 upregulates IL-10, we activated cultures in the presence or absence of neutralizing anti-IL-27 antibody. Strikingly, we observed consistent and extensive inhibition of IL-10 production in this setting indicating a prominent role for endogenous IL-27 in basal IL-10 production in activated PBMCs (Fig. 2C). Others have reported that IFN-β potently upregulates IL-10 expression (29, 31, 32). To confirm this in our culture system, we performed this study in PBMCs from seven individuals and consistently observed significant upregulation of IL-10 by IFN-β (Fig. 2D). Taken together these data show that both IL-27 and IFN-β upregulate IL-10 in PBMCs.

Figure 2. Endogenous IL-27 drives IL-10 production in human PBMCs in vitro.

PBMCs from healthy donors were activated with anti-CD2/anti-CD3/anti-CD28 antibodies for up to 7 days (A) or 5 days (B, C, D) and supernatants were assayed for IL-10 by ELISA (A) Time course analysis shows maximal IL-10 upregulation at 120hrs (n = 4 from each of 3 donors). Anti-IL-27 neutralizing antibody inhibits IL-10 production in the presence of exogenous IL-27 (B) or in basal conditions (C). Exogenous IFN-β also upregulated IL-10 production (D). n = 4–7 donors.

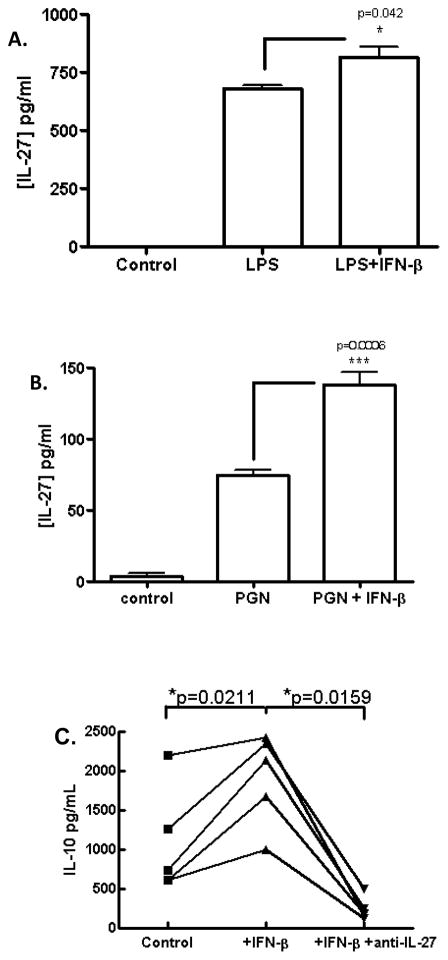

IFN-β upregulates IL-27 production by human monocytes

In MS patients, upregulation of IL-10 in peripheral blood is a positive indicator of responsiveness to IFN-β therapy (23). In addition, upregulation of IL-10 by IL-27 is reminiscent of IFN-β bioactivity in murine systems (28). Given such similarity it is plausible that IL-27 may mediate at least some of the immunomodulatory effects of IFN-β. This hypothesis was supported by the fact that IFN-β induced IL-27 expression in murine cells, and in humans this has also been shown using in vitro differentiated DCs (18, 33). Given that our culture system constituted fresh PBMCs we sought to examine the effect of IFN-β on freshly isolated monocytes without prior in vitro differentiation. To this end, we purified monocytes from human PBMCs by immunomagnetic separation and activated cells with LPS in the presence or absence of IFN-β. As expected, LPS induced IL-27 production and this was augmented by IFN-β (Fig. 3A). Peptidoglycan (PGN) has recently been shown to drive Th17 cells and we have also observed this phenomenon (unpublished observations). Interestingly, we found that PGN also drove the production of IL-27 by human monocytes (Fig. 3B) suggesting that this microbial inflammatory signal invokes both inducing and suppressive pathways for Th17 cell development. We tested the effect of IFN-β in this model and found, consistent with the LPS-activated model, that IFN-β significantly augmented IL-27 production (Fig. 3B). To examine if IL-27 played a role in the IFN-β-IL-10 axis, we cultured activated PBMCs with IFN-β in the presence or absence of neutralizing anti-IL-27 antibody. As expected, PBMCs cultured in the presence of IFN-β and IgG control antibody produced significantly elevated levels of IL-10 while PBMCs cultured with IFN-β in the presence of anti-IL-27 neutralizing antibody produced levels of IL-10 significantly lower than the basal production of activated PBMCs (Fig. 3C). These data demonstrate that IL-27 mediates upregulation of IL-10 by IFN-β in activated PBMCs.

Figure 3. IFN-β upregulates IL-27 production in human monocyte cultures.

CD14+ monocytes were purified form PBMCs by immunomagnetic separation and activated with LPS (A) or PGN (B) in the presence or absence of IFN-β for 2 days. Supernatants were assayed for heterodimeric IL-27 by ELISA. PBMCs were activated with anti-CD2/anti-CD3/anti-CD28 in the presence or absence of IFN-β and neutralizing anti-IL-27 antibody for 5 days and supernatants were assayed for IL-10 by ELISA. n = 3–5 donors, data representative of at least 2 experiments.

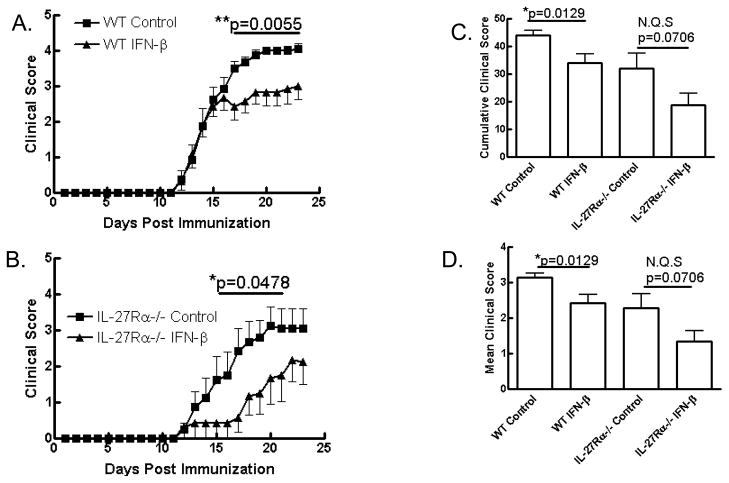

IL-27 is not required for suppression of actively induced EAE by IFN-β

IFN-β is a first line therapy for MS and has been shown to suppress EAE in a range of models (34–37). We and others have shown that IL-27 suppresses EAE (5, 12, 38) and in a Th1-driven model of EAE we have shown that this suppression is dependent on IL-10 (16). Given the correlation between IL-10 levels and responsiveness to IFN-β therapy in human MS patients and the observation that IFN-β drives IL-10 through IL-27 (Fig. 3C), we hypothesized that IL-27 mediated the suppression of EAE by IFN-β. To test if IL-27 mediated the therapeutic effect of IFN-β in vivo, we treated WT and IL-27 receptor-deficient mice, which had been immunized to develop EAE, with IFN-β i.p. daily from day 0 to day 19 post-immunization. IFN-β significantly suppressed clinical disease in WT mice (Fig. 4A, C, D). Very surprisingly we also observed suppression of EAE by IFN-β in IL-27R-deficient mice (Fig. 4B, C, D). Disease incidence in all groups was comparable (Table 1). These data disprove our hypothesis and demonstrate that IL-27 signaling is not required for the suppression of MOG35-55-induced EAE by IFN-β. Given this surprising finding, we sought to further investigate the immunoregulatory mechanisms of IFN-β and IL-27.

Figure 4. IFN-β inhibits clinical EAE independent of IL-27 signaling.

WT and IL-27R-deficient mice were immunized to develop EAE and treated with IFN-β (50,000U/mouse/day i.p.) from day 0–19 post-immunization. IFN-β effectively suppressed clinical EAE in WT (A; n=8) and il-27rα−/− (B; n=6) mice. Cumulative (C) and mean (D) clinical scores were significantly reduced in WT mice treated with IFN-β and a similar but not quite significant trend in il-27rα−/− mice was observed. N = 6–8 mice per experiment and data are representative of two independent experiments.

Table 1.

Disease incidence in experiments of WT and IL-27R-deficient mice immunized to develop EAE and treated with IFN-β daily from day 0–19 post immunization. See Figure 4.

| WT Control | WT IFN-β | il-27rα−/− Control | il-27rα−/− IFN-β | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expt 1 | 8/8 (100%) | 6/6 (100%) | 6/6 (100%) | 7/8 (87.5%) |

| Expt 2 | 8/8 (100%) | 7/8 (87.5%) | 4/5 (80%) | 4/5 (80%) |

| Total | 16/16 (100%) | 13/14 (92.9%) | 9/10 (90%) | 11/13 (94.6%) |

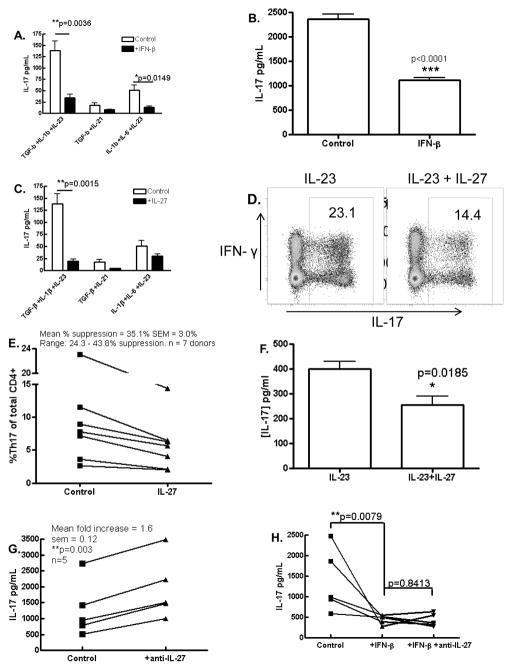

IL-27 and IFN-β inhibit human Th17 cells

Given the pathogenic potential of Th17 cells in EAE and MS and previous reports of suppressive effects of IFN-β and IL-27 on these cells (5, 9, 25), we investigated this phenomenon in fetal and adult human T cell cultures. Development and regulation of human Th17 cells is currently a contentious topic. Thus we sought to examine if IFN-β suppresses Th17 cells in a number of Th17-supportive conditions. To this end we first examined the effect of exogenous IFN-β on de novo differentiation of Th17 cells. Human naive CD4+ cells (CD45RA+) derived from cord blood were cultured in serum-free medium and activated with anti-CD2/anti-CD3/anti-CD28 antibodies under Th17 polarizing conditions. Given the current disagreement in the optimal cytokine milieu for de novo human Th17 differentiation we tested a range of cytokine combinations as described in figure 5A and in each case, tested the effects of IFN-β on IL-17 production. We consistently observed that IFN-β inhibited IL-17 production by CD4+ cultures regardless of the polarizing cytokine milieu which was statistically significant in two of the three cytokine cocktails tested (Fig. 5A). We next investigated the effect of IFN-β on PBMCs from adult donors. In the presence of IL-23, IFN-β had a variable effect on IL-17 production (data not shown). However, IFN-β significantly suppressed IL-17 under basal conditions (Fig. 5B). We next examined the effect of IL-27 in the model of de novo Th17 differentiation described above. Similarly to IFN-β, IL-27 suppressed IL-17 production in this model, in agreement with recent reports and this was statistically significant in the conditions that generated the most robust expression of IL-17 (TGF-β+IL-1β+IL-23) (Fig. 5C) (26, 33). Next we investigated the effect of IL-27 in PBMCs cultured in the presence of IL-23 which supports differentiated Th17 cells. PBMCs from adult donors were cultured for 5 days in the presence of IL-23 and anti-CD2/anti-CD3/anti-CD28 antibodies in the presence or absence of IL-27. PBMCs were then analyzed by flow cytometry and IL-27 treatment resulted in lower proportions of IL-17+ cells within the CD4+ population (23.1% versus 14.4%) (Fig. 5D, representative plot from a single, maximal response donor). Proportions of IL-17+ cells were highly variable across experiments and between donors; however the proportion of CD4+ cells producing IL-17 decreased in all 7 donors in the presence of IL-27 (Figure 5E). Although not as striking as observed in de novo differentiating Th17 cells, PBMCs cultured with IL-23 in the presence of IL-27 had significantly less IL-17 detectable in the supernatant compared to control PBMC cultures with IL-23 alone (Fig. 5F). We repeated this study in 7 donors and found mild but significant suppression of secreted IL-17 in 5 of 7 donors (data not shown). Given the lower level of suppression of IL-17 by IL-27 in PBMC cultures compared to naïve CD4+ cell cultures, we hypothesized that endogenous IL-27 bioactivity may be exerting a suppressive effect on IL-17 production in control PBMC cultures that did not receive exogenous IL-27. To test this hypothesis we activated IL-23-driven PBMCs with anti-CD2/anti-CD3/anti-CD28 in the presence or absence of neutralizing anti-IL-27 antibody. Neutralization of endogenous IL-27 significantly enhanced IL-17 production in these cultures suggesting that endogenous IL-27 inhibits IL-17 development in this model (Fig. 5G). We repeated this experiment in 5 donors and found that anti-IL-27 neutralizing antibody enhanced IL-17 production in all 5 donors (Fig. 5G).

Figure 5. Inhibition of Th17 development by IFN-β and IL-27.

Naïve CD4+ T cells from cord blood were activated with anti-CD2/anti-CD3/anti-CD28 in the presence or absence of IFN-β (A) or IL-27 (C) in a range of Th17 polarizing cytokine cocktails and IL-17 detection in supernatants was suppressed in all conditions (n=3). Expression of IL-17 by PBMCs from healthy adult donors activated as above was also suppressed by IFN-β (B) and IL-27 as determined by flow cytometry (D, E) and ELISA (F). Neutralization of endogenous IL-27 increased IL-17 production in activated adult PBMC cultures (G) but did not overcome the suppressive effect of IFN-β on IL-17 production by PBMCs (H). Data representative of at least two and up to four independent experimens.

Given similar suppressive profiles of IFN-β and IL-27 in human Th17 cultures, we hypothesized that IL-27 mediates the suppression of IL-17 by IFN-β in this model. When PBMCs were activated in the presence of IFN-β, IL-17 production was significantly suppressed, however, anti-IL-27 antibody did not abrogate this suppressive effect (Fig. 5H). These data suggest that contrary to our hypothesis, IL-27 is not required for the suppression of IL-17 by IFN-β in PBMC cultures. Thus IFN-β and IL-27 both inhibit human Th17 responses, however these data suggest distinct regulatory pathways for each cytokine, at least in the context of direct effects on PBMCs activated via TCR and co-stimulation.

IFN-β and IL-27 suppress human Th17 differentiation independent of IL-10

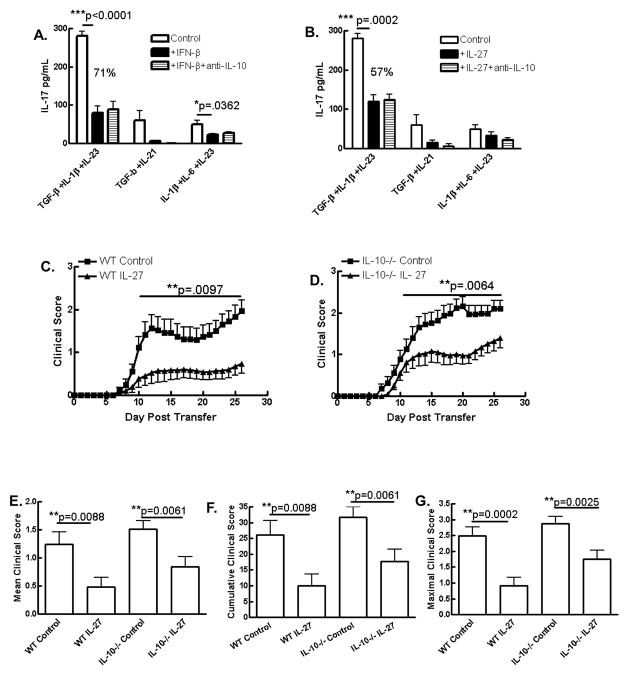

To further investigate these complex immunoregulatory pathways, we investigated if IL-10 is involved in the suppression of IL-17 by either IL-27 or IFN-β. To test this in human cells we activated naïve CD4+ cells from human cord blood in Th17 polarizing conditions using combinations of cytokines as described. Cultures were treated with IL-27 or IFN-β in the presence or absence of neutralizing anti-IL-10 antibody. We did not see any loss of suppression of IL-17 when IL-10 was neutralized in samples that were treated with either IFN-β (Fig. 6A) or IL-27 (Fig. 6B). This suggests that IFN-β and IL-27 suppress de novo Th17 differentiation independent of IL-10.

Figure 6. Suppression of Th17 differentiation by IFN-β and IL-27 and of Th17-driven EAE by IL-27 does not require IL-10.

Naïve CD4+ T cells from cord blood were activated with anti-CD2/anti-CD3/anti-CD28 in the presence or absence of IFN-β (A) or IL-27 (B) in a range of Th17 polarizing cytokine cocktails +/− neutralizing anti-IL-10 and IL-17 in supernatants was measured by ELISA (n = 3). (C–G) Splenocytes and lymph node cells from immunized donor WT and IL-10-deficient mice were reactivated with MOG35-55 and IL-23 (10 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of IL-27 (10 ng/ml) for 3 days prior to purification of CD4+ cell by immunomagnetic separation and i.v. injection to naïve recipient WT C57BL/6 mice. Recipient animals were treated with PT on days 0 and 2 post transfer (200ng/mouse/day) and clinical EAE was scored daily. Data are pooled from 4 independent experiments (see table 2).

IL-10 is not required for suppression of Th17-biased EAE by IL-27

Previously we have shown that IL-10 is required for the suppression of EAE by IL-27, however, this was in an IL-12-driven Th1-biased model of adoptively transferred EAE (16). Given that we did not observe a role for IL-10 in suppression of IL-17 by IL-27 in human naïve CD4+ cells in any of the polarizing conditions tested (Fig. 6B), we questioned the relevance of the IL-27/IL-10 axis in the Th17 pathologic setting. To address this question in vivo, we established an IL-23-driven Th17-biased model of adoptively transferred EAE using MOG35-55 immunized C57BL/6 and il-10−/− donors and an in vitro culture phase of encephalitogenic cells reactivated with antigen in the presence of IL-23. In agreement with our previous findings in an SJL/PLP model of IL-23-driven EAE (5), we observed significant suppression of disease when MOG35-55-reactive cells were treated with IL-27 prior to transfer (Fig. 6C). Interestingly, we also observed suppression when IL-10-deficient donor cells were treated with IL-27 and injected into WT recipients (Fig. 6D). Suppression of clinical disease by IL-27 was slightly more pronounced in mice receiving WT cells than in mice receiving il-10−/− cells which may point towards a minor role for IL-10, however, this may also simply be due to slightly enhanced disease severity in mice receiving il-10−/− cells. IL-27 suppressed the mean, maximal and cumulative clinical scores (Fig. 6E–G) and the incidence (Table 2) in both genotypes. These data demonstrate that IL-27 suppresses IL-23-driven EAE independently of IL-10 contrasting with the requirement of IL-10 for suppression of Th1-biased EAE by IL-27 (16).

Table 2.

Disease incidence in experiments of an IL-23-driven Th17-biased model of adoptively transferred EAE. WT mice received WT or IL-10-deficient CD4+ T cells that had been reactivated in vitro with MOG35-55 antigen and IL-23 in the presence or absence of IL-27. See Figure 6 C-G.

| WT Control | WT +IL-27 | il-10−/− Control | il-10−/− +IL-27 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expt 1 | 5/5 (100%) | 0/5 (0%) | 4/7 (57.1%) | 0/7 (0%) |

| Expt 2 | 7/7 (100%) | 5/5 (100%) | 10/10 (100%) | 7/7 (100%) |

| Expt 3 | 4/5 (80%) | 1/7 (14.3%) | 10/10 (100%) | 6/6 (100%) |

| Expt 4 | 9/10 (90%) | 5/6 (83.3%) | 10/10 (100%) | 9/10 (90%) |

| Total | 25/27 (92.6) | 11/23 (47.8) | 34/37 (91.9) | 22/30 (73.3) |

DISCUSSION

These studies were initiated to translate previous findings in murine systems to human experimental models. In agreement with the findings of our group and others, demonstrating that exogenous IL-27 drives IL-10 expression in murine T cells (9, 14–16), we confirm here that this also occurs in activated human T cells. This is in agreement with recent reports by other groups (26, 39, 40). However, a key difference in our system is that we did not observe a consistent direct effect of IL-27 on purified CD4+ T cells, suggesting that influence of other mononuclear cells in our culture system potentiates the effect of IL-27 on IL-10 production by CD4+ T cells. This is somewhat reminiscent of our findings in the murine in vitro system in which we observed potentiation of T cell IL-10 upregulation by IL-27 when non-T cells were present (16). Furthermore, separate studies by Stumhofer et al. and Awasthi et al. showed that TGF-β potentiated IL-10 upregulation by IL-27 in murine cultures (14, 17). A potential explanation for the difference between our findings in human T cells and that of Murugaiyan et al. (26) is the absence of serum in our culture conditions as serum would contain appreciable levels of TGF-β and indeed, we observed significantly enhanced IL-10 production in the presence of serum (Fig. 1C). Given the potent induction of IL-10 by TGF-β (14, 17) we chose to perform all cell culture experiments in serum-free conditions. We identified powerful bioactivity of endogenous IL-27 in driving IL-10 production in PBMC cultures as exemplified by a lack of IL-10 production in the presence of neutralizing anti-IL-27 antibody. This confirmed that upregulation of T cell IL-10 production by exogenously added IL-27 reflected a function of endogenous IL-27.

IL-27 expression can be upregulated by type I IFN signaling (38) and IFN-β is a first line therapy for MS. Furthermore there is a positive correlation between a clinical response to IFN-β therapy and IL-10 upregulation in serum (23). Based on these relationships we developed a working hypothesis that IL-27 may mediate the clinical effect of IFN-β in MS and that this may involve IL-10 upregulation. We first confirmed upregulation of human IL-10 by IFN-β in our experimental PBMC model and then examined IL-27 production in response to IFN-β. In order to maximize similarity to an in vivo scenario we chose a model of freshly isolated monocytes from adult peripheral blood, immediately activated cells with TLR stimuli in the presence or absence of IFN-β and measured heterodimeric IL-27 protein secreted into culture supernatants. In this model, IFN-β indeed upregulated IL-27 protein production and we went on to identify that IL-27 was required for IL-10 upregulation by IFN-β. These data lent support to our working hypothesis and the conclusions of a recent study by Sweeney et al. that IL-27 mediated the suppressive effect of IFN-β in MS (33). However, to categorically test this hypothesis in CNS autoimmune inflammation, we returned to the mouse model of MOG35-55-induced EAE. Very surprisingly, in two separate experiments, IFN-β suppressed EAE both in WT mice and in mice lacking the IL-27 receptor (wsx-1−/−).

These in vivo experiments disproved our working hypothesis and demonstrated that IL-27 signaling is not required for the therapeutic suppressive effect of IFN-β in actively-induced EAE. These studies cannot rule out a role for IL-27 in the suppression of EAE by IFN-β in a wildtype system, however our results suggest that if this is the case, other mechanisms of IFN-β prevail in the absence of IL-27 to orchestrate EAE suppression in an IL-27-independent manner. There are significant differences both in the interferon signaling system between mouse and man and between EAE and MS. Indeed, we only tested one type of EAE model due to restrictions of the genetic background of wsx1−/− mice, however these findings call into question the functional relevance of IL-27 in clinical responses to IFN-β therapy at least in murine models and suggest that IL-27 upregulation by IFN-β in MS therapy may be merely associative.

These surprising findings led us to examine other aspects of immunosuppression by IFN-β and IL-27. As Th17 cells are regarded as pathogenic effectors of autoimmune inflammation in many experimental models, and in MS, we sought to investigate the effects of IFN-β and IL-27 on human Th17 cells. Differentiation and stabilization of human Th17 cells is a controversial topic at present and a number of recent studies have shown direct and indirect suppressive effects of IFN-β and IL-27 on IL-17/Th17 responses in different models (18, 26, 28, 29, 32, 33). We chose to investigate de novo human Th17 differentiation using truly naïve CD4+ T cells from cord blood, differentiated in three different cocktails of Th17-promoting cytokines. We consistently observed suppression of Th17 differentiation by IFN-β and by IL-27. We then moved on to PMBCs from adult blood which are more representative of clinical samples. While we did not observe human Th17 expansion in response to the cytokines that drove de novo Th17 differentiation, we did observe Th17 expansion in response to IL-23, which was suppressed by IL-27. As IFN-β suppressed IL-17 and upregulated IL-27 in our models, which is in agreement with other reports (18, 33) we tested if IL-27 mediated the suppressive effect of IFN-β on IL-17. Again to our surprise, we discovered that IL-27 was not required for the suppressive effect of IFN-β on IL-17 production in our system of PBMCs activated via CD3 and CD28 as demonstrated by comparable suppression in the presence of neutralizing anti-IL-27 antibody. This contrasts with a recent report (33) which showed that IL-27 mediated the suppression of human Th17 development by IFN-β in a different model. The model used initially differentiated human DCs in vitro, which were then activated with zymosan in the presence or absence of IFN-β and neutralizing anti-IL-27 antibody. Subsequently supernatants from these cultures were added to CD4+ T cells activated with irradiated allogeneic PBMCs to drive Th17 differentiation. In contrast, to be somewhat representative of therapeutic administration of IFN-β, we treated whole PBMCs with IFN-β and did not observe any loss of IL-17 suppression by IFN-β when neutralizing anti-IL-27 was included. The findings of these two studies likely differ due to the different IFN-β-responsive cells in the separate experimental models and different activation stimuli used and suggest differential requirements for IL-27 in the suppression of Th17 development by IFN-β. To add further complexity to the range of IFN-β responsive cell types that regulate Th17 development, other studies by Ramgolam et al. and Zhang et al. have shown that supernatants from both DCs and B cells treated with IFN-β exhibit impaired capacity to drive Th17 differentiation and this was associated with decreased IL-23p19 and IL-1β and increased IL-12p35 and IL-27p28 expression (18, 29, 30). Taken together, all these studies reveal multiple inhibitory direct and indirect effects of IFN-β on Th17 responses and the requirement of IL-27 for IFN-β-mediated suppression of human Th17 cells in vivo likely depends on the cellular microenvironment.

Given that IL-10 upregulation by IFN-β was downstream of IL-27 in our earlier studies (Fig. 3C), we asked if IL-10 was required for the suppressive effect of IFN-β or IL-27 on de novo human Th17 differentiation. In all three de novo Th17-differentiating conditions tested, IL-10 was not required for the suppressive effect of either IFN-β or IL-27. These data added further complexity to the divergent immunosuppressive pathways of IFN-β and IL-27 on Th17 cells and CNS autoimmune inflammation. We were particularly perplexed that IL-10 did not influence suppression of de novo human Th17 cell differentiation by IL-27 as we had previously observed a requirement of IL-10 for suppression of murine IL-17 by IL-27 in non-polarized conditions and a partial role in Th17 supportive conditions (16). We had also identified that IL-10 was required for suppression of adoptively-transferred EAE by IL-27 however, this was in an IL-12-driven Th1-biased model of disease (16). We had previously shown that IL-27 also suppresses IL-23-driven, Th17-biased EAE in an SJL/PLP139-151 model and suppression of Th17 cells was a central mechanism (5). Thus, given that IL-10 was not required for human Th17 suppression by IL-27, we asked if IL-10 was required for suppression of Th17-biased EAE by IL-27. Given the genetic background of il-10−/− mice we performed these studies using MOG35-55 and C57BL/6 mice rather than using PLP139-151 and SJL mice. In this model, donor cells were exposed to exogenous IL-27 during the in vitro phase of culture and as expected, this resulted in a significant reduction in clinical disease in recipient mice. Surprisingly, IL-27 also suppressed the pathogenicity of il-10−/− cells to a similar degree. These findings suggest that IL-27 suppresses Th17-biased CNS autoimmune inflammation independently of IL-10, which is in stark contrast to its mechanism of action in Th1-driven disease (16). Thus our data suggest that IL-27 utilizes distinct mechanisms of action to inhibit autoimmune inflammation depending on the central pathogenic effectors mediating disease.

Our findings from these collective studies reveal a complex and somewhat paradoxical network of immunoregulatory functions of IFN-β, IL-27 and IL-10. Most strikingly, we have determined that IL-27 signaling is not required for suppression of EAE by IFN-β, likely having important implications for the mechanism of action of IFN-β in MS. We have also identified that IL-10 does not mediate the suppressive effect of IL-27 in a Th17-biased model of EAE. This presents a paradigm whereby IL-27 utilizes different mechanisms to suppress Th1-driven pathology versus Th17-driven pathology, the former dependent on IL-10 (16) and the latter, IL-10 independent (Fig. 6C, D).

It is important to recognize that EAE is a collection of models that, taken together, reflect many aspects of the heterogeneous disease that is human MS, far more accurately than any single model of EAE or indeed single viral- or toxin-induced models of CNS demyelination alone. Encouragingly, we have now demonstrated that exogenous IL-27 suppresses clinical EAE in four separate models; actively induced EAE using MOG35-55 antigen in C57BL/6 mice (5), Th17-biased (IL-23-driven) adoptively transferred EAE using PLP139-151 antigen in the SJL mouse model (5), Th1-biased (IL-12-driven) adoptively transferred EAE using MOG35-55 antigen in C57BL/6 mice (16) and here in a Th17-biased (IL-23-driven) model of adoptively transferred EAE using MOG35-55 antigen in C57BL/6 mice. Furthermore, Guo et al. have also shown that exogenous IL-27 suppresses highly severe EAE observed in ifnar1−/− mice (38). It is likely that multiple cellular and molecular mechanisms mediate the effects of IL-27 in these models, many of which may remain to be elucidated. While it is tempting to speculate that IL-27 may be a potential therapeutic for inflammatory diseases such as MS, the potent suppression of de novo Th17 differentiation which is observed in mouse and human systems (9, 12, 26, 41) (Fig. 5) and indeed suppressive effects on Th1 and Th2 responses also are a concern for maintenance of general immune function. Thus, understanding the mechanisms of IL-27 in suppression of clinical disease is of prime importance such that targeted therapeutics that minimize broad immunosuppression, can be designed. It is also imperative to investigate in depth, effects of IL-27 in a wide range of models of inflammatory disease. Of particular interest is a recent report by Axtell et al. that demonstrated both suppressive and exacerbating effects of IFN-β on Th1 and Th17 biased models of EAE respectively (34). Given the close relationship between the functions of IFN-β and IL-27 it is important to identify the shared as well as distinct mechanisms of action in experimental models. Studies have demonstrated anatomically and pathologically distinct models of EAE based on the proportions of encephalitogenic Th1 and Th17 cells (42) and pathogenic Th9 cells have also been implicated (43). Clinical MS varies greatly, not only in the type of lesions that develop but also in the anatomical sites that are affected and the frequency of attacks. Distinct helper T cell subsets are now implicated in MS and B cell subsets are also prominently implicated as drivers of pathogenesis (44). Such heterogeneity likely contributes to the selective response of patient subsets to immunomodulatory therapies such as IFN-β. Broad immunosuppression is not the optimal solution to treating inflammatory diseases such as MS, thus, it is crucial to elucidate specific mechanisms of clinical disease suppression in order to improve therapeutic options.

Our findings here reveal that in human experimental models derived from PBMCs, IFN-β and IL-27 both upregulate IL-10; IFN-β upregulates IL-27 and IL-27 is required for IL-10 upregulation by IFN-β. However, while both IFN-β and IL-27 suppress Th17 responses, this suppression is independent of IL-10 and suppression of Th17 cells by IFN-β is independent of IL-27 in the models we tested. In murine models of EAE we found that IL-27 signaling is not required for suppression of EAE by IFN-β and that IL-10 is not required for suppression of Th17-biased EAE by IL-27, which is in stark contrast to suppression of Th1-driven EAE by IL-27 (16). Taken together, these findings present distinct regulatory mechanisms of IFN-β and IL-27 in Th1 and Th17-driven inflammation.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the NIH (1U19A1082726 and 2R01NS046782) and the Department of Employment and Learning (Northern Ireland).

Literature cited

- 1.Villarino AV, Huang E, Hunter CA. Understanding the pro- and anti-inflammatory properties of IL-27. Journal of immunology. 2004;173:715–720. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pflanz S, Timans JC, Cheung J, Rosales R, Kanzler H, Gilbert J, Hibbert L, Churakova T, Travis M, Vaisberg E, Blumenschein WM, Mattson JD, Wagner JL, To W, Zurawski S, McClanahan TK, Gorman DM, Bazan JF, de Waal Malefyt R, Rennick D, Kastelein RA. IL-27, a heterodimeric cytokine composed of EBI3 and p28 protein, induces proliferation of naive CD4(+) T cells. Immunity. 2002;16:779–790. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00324-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collison LW, Workman CJ, Kuo TT, Boyd K, Wang Y, Vignali KM, Cross R, Sehy D, Blumberg RS, Vignali DA. The inhibitory cytokine IL-35 contributes to regulatory T-cell function. Nature. 2007;450:566–569. doi: 10.1038/nature06306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Niedbala W, Wei XQ, Cai B, Hueber AJ, Leung BP, McInnes IB, Liew FY. IL-35 is a novel cytokine with therapeutic effects against collagen-induced arthritis through the expansion of regulatory T cells and suppression of Th17 cells. European journal of immunology. 2007;37:3021–3029. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fitzgerald DC, Ciric B, Touil T, Harle H, Grammatikopolou J, Das Sarma J, Gran B, Zhang GX, Rostami A. Suppressive effect of IL-27 on encephalitogenic Th17 cells and the effector phase of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Journal of immunology. 2007;179:3268–3275. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.3268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li J, Gran B, Zhang GX, Rostami A, Kamoun M. IL-27 subunits and its receptor (WSX-1) mRNAs are markedly up-regulated in inflammatory cells in the CNS during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neurol Sci. 2005;232:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smits HH, van Beelen AJ, Hessle C, Westland R, de Jong E, Soeteman E, Wold A, Wierenga EA, Kapsenberg ML. Commensal Gram-negative bacteria prime human dendritic cells for enhanced IL-23 and IL-27 expression and enhanced Th1 development. European journal of immunology. 2004;34:1371–1380. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sonobe Y, Yawata I, Kawanokuchi J, Takeuchi H, Mizuno T, Suzumura A. Production of IL-27 and other IL-12 family cytokines by microglia and their subpopulations. Brain Res. 2005;1040:202–207. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.01.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stumhofer JS, Laurence A, Wilson EH, Huang E, Tato CM, Johnson LM, Villarino AV, Huang Q, Yoshimura A, Sehy D, Saris CJ, O’Shea JJ, Hennighausen L, Ernst M, Hunter CA. Interleukin 27 negatively regulates the development of interleukin 17-producing T helper cells during chronic inflammation of the central nervous system. Nature immunology. 2006;7:937–945. doi: 10.1038/ni1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Villarino A, Hibbert L, Lieberman L, Wilson E, Mak T, Yoshida H, Kastelein RA, Saris C, Hunter CA. The IL-27R (WSX-1) is required to suppress T cell hyperactivity during infection. Immunity. 2003;19:645–655. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00300-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pflanz S, Hibbert L, Mattson J, Rosales R, Vaisberg E, Bazan JF, Phillips JH, McClanahan TK, de Waal Malefyt R, Kastelein RA. WSX-1 and glycoprotein 130 constitute a signal-transducing receptor for IL-27. Journal of immunology. 2004;172:2225–2231. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.4.2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Batten M, Li J, Yi S, Kljavin NM, Danilenko DM, Lucas S, Lee J, de Sauvage FJ, Ghilardi N. Interleukin 27 limits autoimmune encephalomyelitis by suppressing the development of interleukin 17-producing T cells. Nature immunology. 2006;7:929–936. doi: 10.1038/ni1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshimura T, Takeda A, Hamano S, Miyazaki Y, Kinjyo I, Ishibashi T, Yoshimura A, Yoshida H. Two-sided roles of IL-27: induction of Th1 differentiation on naive CD4+ T cells versus suppression of proinflammatory cytokine production including IL-23-induced IL-17 on activated CD4+ T cells partially through STAT3-dependent mechanism. Journal of immunology. 2006;177:5377–5385. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.5377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Awasthi A, Carrier Y, Peron JP, Bettelli E, Kamanaka M, Flavell RA, Kuchroo VK, Oukka M, Weiner HL. A dominant function for interleukin 27 in generating interleukin 10-producing anti-inflammatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1380–1389. doi: 10.1038/ni1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Batten M, Kljavin NM, Li J, Walter MJ, de Sauvage FJ, Ghilardi N. Cutting edge: IL-27 is a potent inducer of IL-10 but not FoxP3 in murine T cells. Journal of immunology. 2008;180:2752–2756. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.2752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fitzgerald DC, Zhang GX, El-Behi M, Fonseca-Kelly Z, Li H, Yu S, Saris CJ, Gran B, Ciric B, Rostami A. Suppression of autoimmune inflammation of the central nervous system by interleukin 10 secreted by interleukin 27-stimulated T cells. Nature immunology. 2007;8:1372–1379. doi: 10.1038/ni1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stumhofer JS, Silver JS, Laurence A, Porrett PM, Harris TH, Turka LA, Ernst M, Saris CJ, O’Shea JJ, Hunter CA. Interleukins 27 and 6 induce STAT3-mediated T cell production of interleukin 10. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1363–1371. doi: 10.1038/ni1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramgolam VS, Sha Y, Jin J, Zhang X, Markovic-Plese S. IFN-beta inhibits human Th17 cell differentiation. J Immunol. 2009;183:5418–5427. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tuohy VK, Yu M, Yin L, Mathisen PM, Johnson JM, Kawczak JA. Modulation of the IL-10/IL-12 cytokine circuit by interferon-beta inhibits the development of epitope spreading and disease progression in murine autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol. 2000;111:55–63. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(00)00384-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Platanias LC. Mechanisms of type-I- and type-II-interferon-mediated signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:375–386. doi: 10.1038/nri1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buttmann M, Rieckmann P. Interferon-beta1b in multiple sclerosis. Expert Rev Neurother. 2007;7:227–239. doi: 10.1586/14737175.7.3.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paolicelli D, Direnzo V, Trojano M. Review of interferon beta-1b in the treatment of early and relapsing multiple sclerosis. Biologics. 2009;3:369–376. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waubant E, Gee L, Bacchetti P, Sloan R, Cotleur A, Rudick R, Goodkin D. Relationship between serum levels of IL-10, MRI activity and interferon beta-1a therapy in patients with relapsing remitting MS. J Neuroimmunol. 2001;112:139–145. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(00)00355-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kikly K, Liu L, Na S, Sedgwick JD. The IL-23/Th(17) axis: therapeutic targets for autoimmune inflammation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:670–675. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Galligan CL, Pennell LM, Murooka TT, Baig E, Majchrzak-Kita B, Rahbar R, Fish EN. Interferon-beta is a key regulator of proinflammatory events in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Mult Scler. 2010;16:1458–1473. doi: 10.1177/1352458510381259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murugaiyan G, Mittal A, Lopez-Diego R, Maier LM, Anderson DE, Weiner HL. IL-27 is a key regulator of IL-10 and IL-17 production by human CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2009;183:2435–2443. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neufert C, Becker C, Wirtz S, Fantini MC, Weigmann B, Galle PR, Neurath MF. IL-27 controls the development of inducible regulatory T cells and Th17 cells via differential effects on STAT1. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:1809–1816. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen M, Chen G, Nie H, Zhang X, Niu X, Zang YC, Skinner SM, Zhang JZ, Killian JM, Hong J. Regulatory effects of IFN-beta on production of osteopontin and IL-17 by CD4+ T Cells in MS. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:2525–2536. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramgolam VS, Sha Y, Marcus KL, Choudhary N, Troiani L, Chopra M, Markovic-Plese S. B cells as a therapeutic target for IFN-beta in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. J Immunol. 2011;186:4518–4526. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang X, Jin J, Tang Y, Speer D, Sujkowska D, Markovic-Plese S. IFN-beta1a inhibits the secretion of Th17-polarizing cytokines in human dendritic cells via TLR7 up-regulation. J Immunol. 2009;182:3928–3936. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rudick RA, Ransohoff RM, Peppler R, VanderBrug Medendorp S, Lehmann P, Alam J. Interferon beta induces interleukin-10 expression: relevance to multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1996;40:618–627. doi: 10.1002/ana.410400412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang L, Yuan S, Cheng G, Guo B. Type I IFN promotes IL-10 production from T cells to suppress Th17 cells and Th17-associated autoimmune inflammation. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28432. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sweeney CM, Lonergan R, Basdeo SA, Kinsella K, Dungan LS, Higgins SC, Kelly PJ, Costelloe L, Tubridy N, Mills KH, Fletcher JM. IL-27 mediates the response to IFN-beta therapy in multiple sclerosis patients by inhibiting Th17 cells. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25:1170–1181. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Axtell RC, de Jong BA, Boniface K, van der Voort LF, Bhat R, De Sarno P, Naves R, Han M, Zhong F, Castellanos JG, Mair R, Christakos A, Kolkowitz I, Katz L, Killestein J, Polman CH, de Waal Malefyt R, Steinman L, Raman C. T helper type 1 and 17 cells determine efficacy of interferon-beta in multiple sclerosis and experimental encephalomyelitis. Nat Med. 2010;16:406–412. doi: 10.1038/nm.2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wender M, Michalak S, Wygladalska-Jernas H. The effect of short-term treatment with interferon beta 1a on acute experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Folia Neuropathol. 2001;39:91–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yasuda CL, Al-Sabbagh A, Oliveira EC, Diaz-Bardales BM, Garcia AA, Santos LM. Interferon beta modulates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by altering the pattern of cytokine secretion. Immunol Invest. 1999;28:115–126. doi: 10.3109/08820139909061141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu M, Nishiyama A, Trapp BD, Tuohy VK. Interferon-beta inhibits progression of relapsing-remitting experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol. 1996;64:91–100. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(95)00160-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guo B, Chang EY, Cheng G. The type I IFN induction pathway constrains Th17-mediated autoimmune inflammation in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1680–1690. doi: 10.1172/JCI33342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anderson CF, Stumhofer JS, Hunter CA, Sacks D. IL-27 regulates IL-10 and IL-17 from CD4+ cells in nonhealing Leishmania major infection. J Immunol. 2009;183:4619–4627. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hedrich CM, Ramakrishnan A, Dabitao D, Wang F, Ranatunga D, Bream JH. Dynamic DNA methylation patterns across the mouse and human IL10 genes during CD4+ T cell activation; influence of IL-27. Mol Immunol. 2010;48:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.El-behi M, Ciric B, Yu S, Zhang GX, Fitzgerald DC, Rostami A. Differential effect of IL-27 on developing versus committed Th17 cells. J Immunol. 2009;183:4957–4967. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stromnes IM, Cerretti LM, Liggitt D, Harris RA, Goverman JM. Differential regulation of central nervous system autoimmunity by T(H)1 and T(H)17 cells. Nat Med. 2008;14:337–342. doi: 10.1038/nm1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jager A, Dardalhon V, Sobel RA, Bettelli E, Kuchroo VK. Th1, Th17, and Th9 effector cells induce experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis with different pathological phenotypes. J Immunol. 2009;183:7169–7177. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weber MS, Hemmer B. Cooperation of B cells and T cells in the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis. Results Probl Cell Differ. 2010;51:115–126. doi: 10.1007/400_2009_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]