Abstract

Context

Chromogranin A (CgA) is a novel biomarker with potential to assess mortality risk of patients with severe sepsis.

Objective

Assess association of CgA levels and mortality risk of severely septic patients.

Methods

Serum CgA levels were measured in 50 hospitalized, severely septic patients with organ failure <48 hours.

Results

Higher CgA levels trended towards higher ICU and hospital mortality. Patients without cardiovascular disease who died in the ICU had higher median (IQR) CgA levels 602.3 (343.3, 1134.3) ng/ml vs. 205.5 (130.7, 325.9) ng/ml, p=0.01.

Conclusions

High CgA levels predict ICU mortality in severely septic patients without prior cardiovascular disease.

Keywords: Chromogranin A, sepsis, biological marker, mortality, cardiovascular diseases

Introduction

Sepsis has a worldwide incidence of approximately 19 million cases per year (Adhikari NK et al., 2010, Jawad I et al., 2012). In the United States, more than 750,000 new cases of severe sepsis occur yearly with a mortality rate up to 40%.(Angus DC and Wax RS, 2001, Gaieski DF et al., 2013, Annane D et al., 2003) Both the incidence and hospital costs of severe sepsis have been raising with total hospital costs in the United States estimated to be $24.3 billion in 2007 (Lagu T et al., 2012, Linde-Zwirble WT and Angus DC, 2004). There are several promising biomarkers with potential to guide management of patients with sepsis. However, there is not yet a biomarker that is reliable and has been validated to accurately identify patients with high risk of mortality in sepsis (Suberviola B et al., 2013, Donadello K et al., 2014, Arora S et al., 2014). Therefore, identification of a new biomarker with therapeutic and prognostic utility could fundamentally change clinical care and potentially impact millions of lives.

Chromogranin A (CgA), a novel protein associated with both adrenergic and cardiovascular systems, has emerged as a promising sepsis biomarker (D’amico M A et al., 2014). Prior studies have shown a correlation between plasma CgA levels and inflammatory markers and risk assessment indices of sepsis. More important, plasma CgA levels may predict prognosis and mortality (Zhang D et al., 2008, Zhang D et al., 2009). Although CgA was originally thought to be released by the adrenal medulla and neuroendocrine system (D’amico M A et al., 2014), CgA has since been isolated in rat and human hearts (Angelone T et al., 2012). The CgA is a pro-hormone and its cleaved peptides have cardiovascular effects, including vasodilatation, inhibition of cardiac contraction, and counteraction of cardiac adrenergic stimulation. High CgA level has been associated with poor prognosis with increased mortality in patients with myocardial infarction (MI), acute coronary syndrome (ACS), or acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) (Angelone T et al., 2012). However, data about the utility of CgA in sepsis is limited. Whether CgA is associated with increased mortality risk in patients with severe sepsis and whether its prognostic utility is affected by prior cardiovascular disease is unknown. Our aim was to assess the association of CgA levels with ICU and hospital mortality in severely septic patients with and without prior cardiovascular disease.

Methods

Study design

A cohort study of patients admitted with severe sepsis at two academic institutions (South Texas Veterans Health Care System and University Hospital, San Antonio, TX) from November 2007 to October 2012 was performed. Subjects were previously enrolled in a double-blind placebo controlled trial assessing the impact of macrolides as immunomodulators. All patients had a blood sample obtained between 24–48 hours of developing organ failure in the presence of sepsis as defined by the American College of Chest Physician/Society of Critical Care Medicine (Bone RC et al., 1992). All the patients received standard therapy including antibiotics at the time of presentation and while in ICU (Dellinger RP et al., 2013). All participants signed a consent form. The study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board (HSC20070713H) and is posted on clinical trials.gov (NCT00708799). Because the trial did not show any significant effects of macrolide therapy on the end-points studied, it was considered valid to combine the intervention and placebo groups for this cohort study.

Inclusion criteria included: age ≥18 years, written informed consent obtained either from the patient or patient’s legal representative, meeting SIRS criteria (two or more of the following conditions: Temperature > 38°C or < 36°C; heart rate > 90 beats/min; respiratory rate > 20 breaths/min or PaCO2< 32mmHg; white blood cell count > 12,000/mm3, < 4000/mm3 or > 10% immature (band) forms, presence of suspected or proven infection, and presence of one or more sepsis-associated organ failure. Exclusion criteria included: evidence of current treatment with medications that could potentially affect the inflammatory response, such as macrolides and corticosteroids; immunosuppressive states; and pregnancy or lactating. In addition, patients were excluded for prolonged QT syndrome, major arrhythmias, or medications associated with an increased risk of QT prolongation (Mortensen EM et al., 2014).

Enrollment and Follow-up

All patients were screened for eligibility at the time of admission to the ICU. Patients were followed daily during hospitalization until time of hospital discharge. After discharge, patients were followed for up to one year post-discharge. Patients were followed either at an outpatient clinic, by chart review, or by phone to assess their survival status. We calculated an Acute Physiology And Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II) score during the first 24 hours following ICU admission (Knaus WA et al., 1985).

Outcomes

The primary outcome was ICU mortality. Secondary outcomes included hospital mortality and need for vasopressors.

Subgroup analysis

Analysis was conducted in patients with and without prior cardiovascular disease, as we expected that patients with prior cardiovascular disease would have increased levels of CgA on admission (Schneider F et al., 2012). Conditions considered as prior cardiovascular diseases included: atrial fibrillation (or other chronic arrhythmia), non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), stroke, chronic heart failure (CHF), or coronary artery disease (CAD). These cardiovascular conditions were identified by medical records.

CgA assay

Venous blood was drawn between 24–48 hours of developing organ failure in the presence of sepsis. Serum CgA levels were measured using a commercially available Human Chromogranin A ELISA Assay Kit by Eagle Biosciences, Inc. (Nashua, New Hampshire, United States), which utilizes a “sandwich” technique with two antibodies binding to two epitopes of CgA. According to Eagle Biosciences, Inc., the normal serum CgA level in healthy adults is less than 100 ng/mL.

Statistical analysis

Fischer exact tests were used to test the associations of demographics and clinical characteristics between both groups. To evaluate the CgA levels, we used median values (IQR) and to compare the differences in concentration we used a non-parametric test (Man-Whitney U Test). Statistical significance was defined as p-value < 0.05. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was developed to assess the accuracy of CgA to predict the outcomes. A subgroup analysis was performed stratifying patients according to the presence or absence of prior cardiovascular diseases at the time of admission. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS, version 22.0 for Windows (IBM) statistical software.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Fifty patients met the inclusion criteria. Six subjects (12%) died in the ICU and 1 subject (2%) died outside of the ICU during hospitalization. Table 1 shows patient’s characteristics stratified by survival status. Survivors had lower APACHE II scores compared to non-survivors, but there were no other statistically significant differences between the groups. The mean (SD) serum CgA level on study inclusion was 389.45 ng/ml (272.74 ng/ml) and the median (IQR) was 304.29 ng/ml (163.73, 582.42). There were no significant differences in CgA levels between patients randomized to macrolide therapy or placebo.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics of severe sepsis patients stratified according to survival status

| Variables | ICU Survivors n=44 | ICU Non-Survivors n=6 |

|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 56.0 (45.3, 66.0) | 61.5 (51.8, 79.5) |

| APACHE II *, median (IQR) | 18.5 (14.0, 22.8) | 29.5 (22.3, 32.8) |

| Male | 39 (88.6) | 5 (83.3) |

| Comorbid conditions | ||

| Prior malignancy | 9 (20.5) | 1 (16.7) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 10 (22.7) | 2 (33.3) |

| Chronic heart failure | 4 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| COPD | 6 (13.6) | 2 (33.3) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 4 (9.1) | 1 (16.7) |

| Depression | 8 (18.2) | 1 (16.7) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 21 (47.7) | 2 (33.3) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 9 (20.5) | 2 (33.3) |

| Liver disease | 3 (6.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Tobacco use | 11 (25.0) | 3 (50.0) |

| Alcohol use | 10 (22.7) | 2 (33.3) |

| Asthma | 4 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Source of infection | ||

| Pulmonary | 15 (34.1) | 2 (33.3) |

| Urinary tract | 15 (34.1) | 1 (16.7) |

| Gastrointestinal | 4 (9.1) | 2 (33.3) |

| Skin | 7 (15.9) | 1 (16.7) |

| Osteomyelitis | 2 (4.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Endocarditis | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Medications on admission | ||

| Statin | 3 (6.8) | 1 (16.7) |

| ACE inhibitor | 2 (4.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Oral corticosteroids | 5 (11.4) | 1 (16.7) |

| Chromogranin A levels | ||

| • Mean (SD) | 359.3 (250.0) | 610.6 (353.6) |

| • Median (IQR) | 237.7 (151.1, 567.4) | 483.9 (394.1, 843.2) |

p < 0.05

All values are given in number of patients (percentages) unless indicated

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

Outcomes

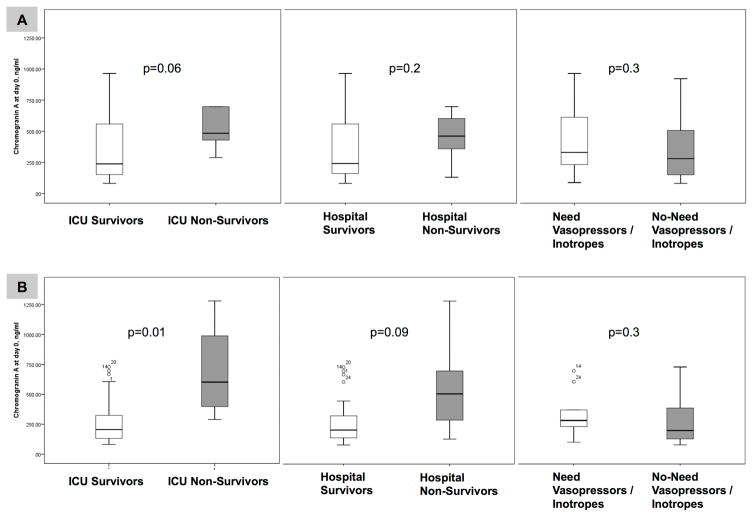

Figure 1A demonstrates that patients with severe sepsis that did not survive while in the ICU had higher median (IQR) CgA levels (483.9 (394.1, 843.2) ng/ml vs. 237.8 (151.1, 567.4) ng/ml, p=0.06). Further, patients with severe sepsis that did not survive during hospitalization also had higher median (IQR) CgA levels (461.0 (288.8, 697.7) ng/ml vs. 241.0 (154.5, 576.4) ng/ml, p=0.2). Severely septic subjects who required vasopressors/inotropes had similar median (IQR) CgA levels compared to those who did not require vasopressors/inotropes at the time of inclusion (280.4 (148.9, 515.2) ng/ml vs. 330.3 (232.9, 615.1) ng/ml, p=0.3).

Figure 1.

Serum CgA levels comparing ICU and hospital survivors vs. non-survivors, and the need for vasopressors/inotropes vs. no need for vasopressors/inotropes. All patients with severe sepsis are shown in Panel A and patients without prior cardiovascular disease are shown in Panel B.

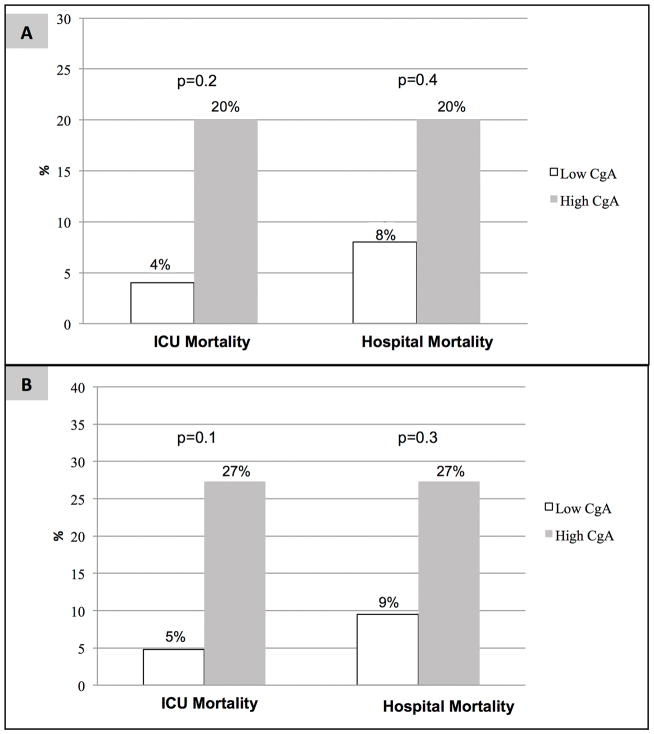

When we dichotomized all severely septic subjects into low or high CgA groups based on median values, we found the high CgA group had a trend towards higher ICU and hospital mortality (Figure 2). No difference in use of vasopressors/inotropes was seen in the high versus low groups, respectively (68.0% vs. 68.0%, p = 0.9).

Figure 2.

Proportion of patients with severe sepsis (Panel A) and those without prior cardiovascular disease (Panel B) who died during the ICU and hospital stratified by serum CgA levels.

In all severely septic subjects, the negative predictive values of CgA levels for ICU mortality and hospital mortality were high (96.0% and 92.0%, respectively). Other diagnostic characteristics of CgA were suboptimal, including sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive values, and AUC-ROC for ICU mortality, hospital mortality and the need for vasopressors/inotropes (Table 2).

Table 2.

Diagnostic characteristics of serum CgA levels among all patients included in the cohort with severe sepsis and among those without prior cardiovascular disease.

| Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | AUC (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients with severe sepsis | |||||

| ICU mortality | 83.3 | 54.5 | 20.0 | 96.0 | 0.74 (0.58–0.90) |

| Hospital mortality | 71.4 | 53.5 | 20.0 | 92.0 | 0.65 (0.44–0.86) |

| Need for vasopressors/inotropes | 50.0 | 50.0 | 68.0 | 32.0 | 0.41 (0.24–0.58) |

| Severe sepsis without prior cardiovascular disease | |||||

| ICU mortality | 75.0 | 71.4 | 27.3 | 95.2 | 0.88 (0.74–1.0) |

| Hospital mortality | 60.0 | 70.4 | 27.3 | 90.5 | 0.74 (0.48–1.0) |

| Need for vasopressors/inotropes | 34.8 | 66.7 | 72.7 | 28.6 | 0.37 (0.16–0.57) |

PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; AUC, area under the curve.

Subgroup analysis

Figure 1B shows that subjects without prior cardiovascular disease who did not survive the ICU stay (n= 4) secondary to severe sepsis had significantly higher median (IQR) serum CgA levels (602.3 (343.3, 1134.3) ng/ml vs. 205.5 (130.7, 325.9) ng/ml, p=0.011). Regarding hospital mortality, non-survivors without prior cardiovascular disease (N=5) also had higher median (IQR) CgA levels (506.9 (209.6, 988.8) ng/ml vs. 205.9 (131.8, 327.9) ng/ml, p=0.09). Severely septic subjects without prior cardiovascular disease (N=33) who required vasopressors/inotropes had similar median (IQR) CgA levels compared to those that did not require vasopressors/inotropes at the time of inclusion (200.7 (130.4, 447.2) ng/ml vs. 284.1 (219.2, 489.1) ng/ml, p=0.3).

When we dichotomized severely septic subjects without prior cardiovascular disease into low or high CgA groups based on the median values, we found that the high CgA group had a trend towards higher ICU and hospital mortality (Figure 2). No difference was seen regarding need for vasopressors/inotropes between the high versus low CgA groups, respectively (71.4% vs. 72.7%, p = 0.9).

In severely septic subjects without prior cardiovascular disease, the negative predictive values of CgA levels for ICU mortality and hospital mortality were 95.2% and 90.5%, respectively. The AUC-ROC of CgA for ICU mortality was 0.884 in the severely septic subjects without prior cardiovascular disease. The other diagnostic characteristics of CgA for ICU and hospital mortality, including sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive values, were less than 80%. Similarly, all of the diagnostic characteristics of CgA regarding the need for vasopressors/inotropes were suboptimal (Table 2).

Discussion

Our study has two main findings. First, serum CgA levels were higher among all patients with severe sepsis who died during their ICU stay. Higher levels of CgA were also associated with ICU mortality in the subgroup of patients with severe sepsis without prior cardiovascular disease. Second, we observed high negative predictive values of CgA levels for ICU and hospital mortality in all patients with severe sepsis, including those without prior cardiovascular disease.

Our results support prior studies that have shown an association between higher CgA level and mortality (Zhang D et al., 2008, Rosjo H et al., 2012, Zhang D et al., 2009). In a study with 120 heterogeneous, critically ill nonsurgical patients, non-survivors were found to have higher median (IQR) plasma CgA levels compared to survivors (293.0 μg/L (163.5– 699.5 μg/L) vs. 86.0 μg/L (53.8–175.3 μg/L) (Zhang D et al., 2008). Another study comparing 53 heterogeneous critically ill patients to 14 healthy controls found that patients with plasma CgA levels greater than 71 μg/L had significantly shorter survival time (Zhang D et al., 2009). Data from the Finnsepsis study with 232 homogeneous patients with severe sepsis showed that patients who did not survive hospitalization had higher plasma CgA levels on study inclusion and after 72 hours (14.0 vs. 9.1 nmol/l, P = 0.002, and 16.2 vs. 9.8 nmol/l, P = 0.001, respectively) (Rosjo H et al., 2012). However, an important limitation of these studies is that not all patients were septic. Only the Finnsepsis study included a homogeneous population of patients with a diagnosis of severe sepsis. However, the Finnsepsis study did not distinguish between ICU and hospital mortality. Another study found sepsis to be more frequently associated with ICU death compared to death during the post-ICU period in the hospital wards (Braber A and Van Zanten AR, 2010). Thus, septic patients may die from causes other than sepsis after being transferred from the ICU to hospital wards. This raises the question of whether the Finnsepsis results can be extrapolated to predict increased ICU mortality with high plasma CgA levels. Our results demonstrate that both ICU non-survivors and hospital non-survivors with severe sepsis indeed had higher CgA levels, particularly among those without prior cardiovascular disease.

CgA is also a biomarker associated with a poor prognosis in acute coronary syndrome, myocardial infarction and acute decompensated heart failure (Angelone T et al., 2012). In the Finnsepsis study, a high plasma CgA level after 72 hours was associated with prior cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores on day 3 (Rosjo H et al., 2012). However, few studies have investigated whether the accuracy of CgA level to predict mortality secondary to severe sepsis is affected by pre-existing cardiovascular disease. By stratifying patients with and without prior cardiovascular disease, we demonstrated a marked increase in accuracy of CgA level to predict ICU mortality.

Little is known about the negative predictive values of CgA levels. Our study showed high negative predictive values of CgA levels to predict ICU and hospital mortality in patients with severe sepsis. Therefore, CgA has the potential to assist clinicians in prognostication of mortality at the time of admission of septic patients to an ICU. In other words, severely septic patients with low CgA levels measured within 24 to 48 hours of developing sepsis-related organ failure have a low likelihood of dying in the ICU or during hospitalization.

Our study has several limitations. First, the sample size is relatively small. Second, there were more male than female patients likely due to one of the two study sites being a Veterans Affairs hospital. It is unknown how serum CgA levels would have been affected if there had been more female subjects, but previous studies did not identify a major difference in serum CgA levels based on gender. Third, our study did not assess how serum CgA levels change with disease progression. However, our goal was to assess the properties of a biomarker that could potentially be used as a point-of-care test. Although this study was a secondary analysis of a randomized trial, no impact of the intervention was identified on serum CgA levels, and CgA measurements were made at the time of enrollment before any anti-inflammatory effect of macrolides could have confounded the results.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that serum CgA levels may play an important prognostic role in assessing ICU mortality, particularly in patients with severe sepsis without prior cardiovascular disease. As a next step, serum CgA needs to be tested as a biomarker on one or more validation cohorts, to further evaluate its potential prognostic utility in patients with sepsis.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Restrepo’s time is partially protected by Award Number K23HL096054 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: All authors have no conflict of interest

Role of authors:

All authors have given their final approval of the manuscript.

CHH contributed to the abstraction of the data, assessment of the biomarker and preparation of the manuscript.

LFR contributed to the design of the study, contributed to the assessment of the biomarker, analysis and interpretation of the data and preparation of the manuscript.

CJO contributed to the assessment of the biomarker, analysis and interpretation of data and preparation of the manuscript.

RB contributed to the design of the study, acquisition of the data, contributed to the analysis of data, and preparation of the manuscript.

AA contributed to the design of the study, acquisition of the data, contributed to the analysis of data, and preparation of the manuscript.

NJS contributed to the interpretation of the data and preparation of the manuscript.

SL contributed to the design of the study, acquisition of the data, contributed to the analysis of data, and preparation of the manuscript.

JP contributed to the design of the study, acquisition of the data, contributed to the analysis of data, and preparation of the manuscript.

CAH contributed to the assessment of the biomarker, analysis and interpretation of data and preparation of the manuscript.

SA contributed to the design of the study, acquisition of the data, contributed to the analysis of data, and preparation of the manuscript.

OS contributed to the design of the study, acquisition of the data, contributed to the analysis of data, and preparation of the manuscript.

AR contributed to the design of the study, acquisition of the data, contributed to the analysis of data, and preparation of the manuscript.

JDC contributed to the design of the study, acquisition of the data, contributed to the analysis of data, and preparation of the manuscript.

IML contributed to the design of the study, acquisition of the data, contributed to the analysis of data, and preparation of the manuscript.

JB contributed to the design of the study, acquisition of the data, contributed to the analysis of data, and preparation of the manuscript.

JB contributed to the design of the study, acquisition of the data, contributed to the analysis of data, and preparation of the manuscript.

FS contributed to the design of the study, acquisition of the data, contributed to the analysis of data, and preparation of the manuscript.

PJM contributed to the design of the study, acquisition of the data, contributed to the analysis of data, and preparation of the manuscript.

JR contributed to the design of the study, acquisition of the data, contributed to the analysis of data, and preparation of the manuscript.

JSV contributed to the design of the study, acquisition of the data, contributed to the analysis of data, and preparation of the manuscript.

MIR is the guarantor of the study; he coordinated all the steps including obtaining funding, coordination acquisition of data, and preparation of the manuscript. MIR had full access to the data and will vouch for the integrity of the data analysis.

References

- Adhikari NK, Fowler RA, Bhagwanjee S, Rubenfeld GD. Critical care and the global burden of critical illness in adults. Lancet. 2010;376:1339–46. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60446-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelone T, Mazza R, Cerra MC. Chromogranin-A: a multifaceted cardiovascular role in health and disease. Curr Med Chem. 2012;19:4042–50. doi: 10.2174/092986712802430009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angus DC, Wax RS. Epidemiology of sepsis: an update. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:S109–16. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107001-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annane D, Aegerter P, Jars-Guincestre MC, Guidet B Network CU-R. Current epidemiology of septic shock: the CUB-Rea Network. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:165–72. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2201087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora S, Singh P, Singh PM, Trikha A. Procalcitonin levels in survivors and non survivors of Sepsis: Systematic review and Meta-analysis. Shock. 2014 doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, Dellinger RP, Fein AM, Knaus WA, Schein RM, Sibbald WJ. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest. 1992;101:1644–55. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.6.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braber A, Van Zanten AR. Unravelling post-ICU mortality: predictors and causes of death. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2010;27:486–90. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e3283333aac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’amico MA, Ghinassi B, Izzicupo P, Manzoli L, Di Baldassarre A. Biological function and clinical relevance of chromogranin A and derived peptides. Endocr Connect. 2014;3:R45–54. doi: 10.1530/EC-14-0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, Annane D, Gerlach H, Opal SM, Sevransky JE, Sprung CL, Douglas IS, Jaeschke R, Osborn TM, Nunnally ME, Townsend SR, Reinhart K, Kleinpell RM, Angus DC, Deutschman CS, Machado FR, Rubenfeld GD, Webb SA, Beale RJ, Vincent JL, Moreno R Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines Committee Including the Pediatric S. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:580–637. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827e83af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donadello K, Scolletta S, Taccone FS, Covajes C, Santonocito C, Cortes DO, Grazulyte D, Gottin L, Vincent JL. Soluble urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor as a prognostic biomarker in critically ill patients. J Crit Care. 2014;29:144–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaieski DF, Edwards JM, Kallan MJ, Carr BG. Benchmarking the incidence and mortality of severe sepsis in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:1167–74. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827c09f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jawad I, Luksic I, Rafnsson SB. Assessing available information on the burden of sepsis: global estimates of incidence, prevalence and mortality. J Glob Health. 2012;2:010404. doi: 10.7189/jogh.02.010404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13:818–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagu T, Rothberg MB, Shieh MS, Pekow PS, Steingrub JS, Lindenauer PK. Hospitalizations, costs, and outcomes of severe sepsis in the United States 2003 to 2007. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:754–61. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232db65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linde-Zwirble WT, Angus DC. Severe sepsis epidemiology: sampling, selection, and society. Crit Care. 2004;8:222–6. doi: 10.1186/cc2917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen EM, Halm EA, Pugh MJ, Copeland LA, Metersky M, Fine MJ, Johnson CS, Alvarez CA, Frei CR, Good C, Restrepo MI, Downs JR, Anzueto A. Association of azithromycin with mortality and cardiovascular events among older patients hospitalized with pneumonia. JAMA. 2014;311:2199–208. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.4304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosjo H, Nygard S, Kaukonen KM, Karlsson S, Stridsberg M, Ruokonen E, Pettila V, Omland T, Group FS. Prognostic value of chromogranin A in severe sepsis: data from the FINNSEPSIS study. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:820–9. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2546-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider F, Bach C, Chung H, Crippa L, Lavaux T, Bollaert PE, Wolff M, Corti A, Launoy A, Delabranche X, Lavigne T, Meyer N, Garnero P, Metz-Boutigue MH. Vasostatin-I, a chromogranin A-derived peptide, in non-selected critically ill patients: distribution, kinetics, and prognostic significance. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:1514–22. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2611-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suberviola B, Castellanos-Ortega A, Ruiz Ruiz A, Lopez-Hoyos M, Santibanez M. Hospital mortality prognostication in sepsis using the new biomarkers suPAR and proADM in a single determination on ICU admission. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:1945–52. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-3056-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Lavaux T, Sapin R, Lavigne T, Castelain V, Aunis D, Metz-Boutigue MH, Schneider F. Serum concentration of chromogranin A at admission: an early biomarker of severity in critically ill patients. Ann Med. 2009;41:38–44. doi: 10.1080/07853890802199791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Lavaux T, Voegeli AC, Lavigne T, Castelain V, Meyer N, Sapin R, Aunis D, Metz-Boutigue MH, Schneider F. Prognostic value of chromogranin A at admission in critically ill patients: a cohort study in a medical intensive care unit. Clin Chem. 2008;54:1497–503. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.102442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]